Abstract

In response to globalization of traditional manufacturing and the growing significance of a symbolic economy, fashion cities are now formed by different mixings of material, design/creative and symbolic forms of production. The intersection between these elements is particularly evident in the global fashion cities, which have experienced a profound process of deindustrialization and a shift between manufacturing and symbolic economies. This paper explores London’s relationship with fashion through the perspectives of key industry actors. We draw upon 30 semi-structured in-depth interviews undertaken between 2016 and 2018 to explore the interplay between material, creative and symbolic forms of fashion production in the city. Interview material is supported by the analysis of data collected from the Office for National Statistics and the Higher Education Statistics Agency. London’s fashion ecosystem is seen as having strong focus on creativity, artistic values and forms of symbolism, which are however regarded as in tension with a viable fashion design industry, an effective business culture and manufacturing system. The paper contributes to the literature on the fashion’s positioning in urban economies by shedding light on the interaction between production, creative and symbolic elements in a global creative city.

1. Introduction

Over the last two decades, increasing attention has been devoted to the fashion industry as a strategic factor for urban growth, regeneration and competitiveness. Globalization of traditional manufacturing and the growing significance of a symbolic economy have led to a diversification of the relationship between fashion and cities across the world (Gilbert Citation2013; Larner, Molloy, and Goodrum Citation2007; Skov Citation2011). Manufacturing has gradually disappeared from the so-called global fashion capitals, which have growingly drawn upon creativity, design and symbolism to remain competitive in the international geography of fashion (Casadei and Lee Citation2020; Evans and Smith Citation2006; Hauge Citation2012; Williams and Currid-Halkett Citation2011). Fashion design and image-making activities have also been the focus for government policies in branding second-tier cities as new fashion hubs to attract tourism, businesses and investments (Martínez Citation2007; Rantisi Citation2011; Skivko Citation2013; Weller Citation2013). Some manufacturing cities are now attempting to reposition as also design and consumption centres (Huang et al. Citation2016; Khan Citation2019; Lazzeretti, Capone, and Casadei Citation2017). As a result, there is now an emerging variety of fashion cities with different mixings of production, design/creative and symbolic elements combining in complex fashion ecosystems (Casadei, Gilbert, and Lazzeretti Citation2021; Heim et al., Citation2021; Wubs, Lavanga, and Janssens Citation2020).

The intersection between these different elements is particularly clear in ‘global fashion capitals’ – London, Paris, New York and Milan (Godart Citation2014). Their history and development have been heterogeneous, combining production, design and consumption, and variously integrating manufacturing, creativity and symbolism (Scott Citation2002). These cities have changed markedly since the late-twentieth century, particularly in response to economic globalization, accentuating separation between material and symbolic forms of production. The contraction of manufacturing has shifted these global cities towards a post-industrial economy of design, creative and symbolic activities (Jansson and Power Citation2010; Merlo and Polese Citation2006; Rantisi Citation2004; Rocamora Citation2009). While there are commonalities, notably in the importance of biannual fashion collections and their significance in the symbolic geographies of the fashion media, these ‘capitals’ have distinctively different fashion ecosystems and development paths (Casadei and Gilbert Citation2018).

London in particular has undergone a distinctive transformation, experiencing the earliest and most pervasive deindustrialization. Fashion as broadly defined is an important element of the London economy, with this broader fashion industry, embracing activities including design, manufacturing, retail, distribution, media and advertising, contributing around £5.5 billion to the London economy (BOP Consulting Citation2017). However, what makes London distinctive is also its reputation as a place dominated by a uniquely diversified cultural and creative sector, which attracts international creative talent, hosts an extraordinary pool of creative industries, and generates strong economic and symbolic value (Landry Citation2001; Lee and Drever Citation2013; Pratt Citation2009). It is also high in the global hierarchy of cities in terms of ‘globalness’, innovation and creativity (Currid Citation2006). These distinctive characteristics – pervasive deindustrialisation combined with exceptional urban creativity – make London an exemplary context to explore the co-existence and interaction of material, creative and symbolic forms of fashion production in the post-industrial economy.

In this paper, London’s relationship with fashion and the changing interplay between these different forms of production is explored through the perspectives of key industry actors. We undertook 30 semi-structured in-depth interviews between 2016 and 2018 with a varied group of leading players in fashion industry, to understand the way creativity, manufacturing and symbolism interact, and examine the construction of discourse on London as global fashion capital. The interview process is reinforced by data collected from the Office for National Statistics and the Higher Education Statistics Agency. The analysis is organised around dimensions seen as key to development of 21st century fashion cities, building on recent research theorising the concept of the fashion city and exploring the positioning of the fashion industry in urban economies (Casadei, Gilbert, and Lazzeretti Citation2021; Heim, Ferrero-Regis, and Payne Citation2021). The paper contributes to understanding the complex mix of production, design/creative and symbolic elements of fashion in a global creative city.

The paper is organised as follows. The following section reviews literature on fashion and cities. Section 3 describes the interview process and other sources of data employed. Section 4 explores respondents’ understandings of the distinctive history and traditions of London, as well as its fashion manufacturing and education systems. It points to the perceived limitations of a focus on creativity and symbolic production. Findings are discussed in section 5. What emerges is a coherent and consistent understanding of London’s fashion ecosystem across a wide range of fashion professionals and leaders, that stresses the importance of the symbolic economy, but also indicates weaknesses in manufacturing and non-retail fashion businesses, and significant obstacles to development of a larger and sustainable design sector.

2. Positioning fashion in urban economies: manufacturing, creativity, and symbolism

The fashion industry has drawn increasing attention of urban authorities and policy makers as a strategic factor for the growth, revitalization, and competitiveness of major and minor cities across the world (Breward and Gilbert Citation2006; Casadei and Gilbert Citation2018; Crewe and Beaverstock Citation1998; Scott Citation2002). The concept of the fashion city has appeared in many strategic plans and promotional activities of local governments that have attempted to reposition cities as attractive destinations for firms, human capital, investments, consumers and tourism. Nowadays, in addition to the traditional global fashion cities, a rising number of cities in developed and developing countries have achieved the status of second-tier cities of fashion production, design, consumption, and culture (Larner, Molloy, and Goodrum Citation2007). This has created the need to enhance knowledge of what constitutes a fashion city, and to codify and theorize this concept. The sociologist Georg Simmel (1904) was the first to address the relationship between fashion and the city, emphasising how nineteenth century cities had created a specific environment for fashion-based social distinction, individuality, and uniformity. In more recent decades, the debate on urban fashion has shifted from sociology to cultural studies, economic geography, regional and urban studies (e.g. Casadei, Gilbert, and Lazzeretti Citation2021; Heim, Ferrero-Regis, and Payne Citation2021; Jansson and Power Citation2010; Martínez Citation2007; Rantisi Citation2004).

In this academic literature, one of the first analyses of the fashion city comes in a discussion of factors required to move Los Angeles to the front rank of global fashion cities (Scott Citation2002). A number of requirements are suggested: a flexible manufacturing basis; a dense cluster of specialist high-quality sub-contractors; major training and research institutes; regionally based but internationally recognised promotional vehicles including fashion media and fashion shows; an evolving fashion and design tradition with strong place-based specific elements; formal and informal connections between the fashion industry and other cultural product industries. However, even in 2002, this list seemed already to look back to fashion city ecosystems of the twentieth century. There has been over time a diversification of the relationship between fashion and cities. While traditional global fashion cities have evolved, newer fashion cities have developed only particular elements of this pathway (Gilbert Citation2013).

Since the early 1970s, the globalization of the production chain, trade liberalization and intense competition from lower-cost locations have affected business practices and production systems, leading to a severe contraction of manufacturing in major fashion centres, accentuating the separation between material and symbolic production (Skov Citation2011; Williams and Currid-Halkett Citation2011). Global fashion cities have become increasingly autonomous from domestic production, shifting towards design and symbolic activities (Evans and Smith Citation2006). Changes in the symbolic economy of media, promotional activities and events, as well as developments in forms of retailing, shopping, and consumption have made the symbolic production of fashion more important than physical manufacturing for these cities (Aspers Citation2010; Skov Citation2011).

This phenomenon can be framed within the growing emphasis on forms of intangible production as ‘instrumental’ means of regenerating urban economies (Grodach Citation2017; Hall Citation2000; Scott Citation2014). In this respect, fashion design is deemed a key component of the cultural economy, able to generate and reinforce the symbolic capital of cities and make these identifiable as ‘creative places’ (Weller Citation2008). In other words, it has been defined as a key post-industrial feature for building the identity and reputation by promoting cultural and creative distinctiveness (Potvin Citation2009; Power and Scott Citation2004). Over the last two decades, a wide variety of cities including Auckland, Copenhagen, Toronto, Johannesburg and Berlin have successfully included fashion design within creativity-related policy initiatives (Leslie, Brail, and Hunt Citation2014; McRobbie Citation2013; Melchior, Skov, and Csaba Citation2011; Rogerson Citation2006).

However, this focus on fashion design does not exhaust the variety of strategies that have been adopted for the promotion and revamping of both established and newer fashion cities. Review of the literature reveals a heterogeneity of fashion cities, with different mixings of design activities, consumption, symbolic and manufacturing elements. In addition to fashion design, image-making activities have played an important role. For example, Jansson and Power (Citation2010) identify a set of ‘brand channels’ that have played a key role in turning Milan into a global fashion capital by disseminating powerful city-based narratives. Among these, there are promotional events, the communicative action of spokespeople, flagship stores, retail districts, showrooms, and direct advertising channels. The symbolic element of fashion has also become a strategic factor for international recognition for cities without strong roots in fashion production. Consumption spaces, fashion events, traditional and newer forms of media and museums have acted as cultural intermediaries for the global dissemination of symbols about cities and fashion (Rantisi Citation2011; Skov Citation2011). For example, the transformation of Antwerp into a new fashion city was based on a city-branding process that prioritised media, museum initiatives and cultural events, and similar strategies were adopted for Barcelona (Chilese and Russo Citation2008; Martínez Citation2007).

There is also significant potential for the development of design and promotional elements of the fashion industry in cities currently dominated by manufacturing. There are many examples of cities with a tradition in the textile and apparel sector that have recently been placed on the international fashion map (Huang et al. Citation2016). In short, there is now very significant diversity in the nature of fashion centres, where fashion is an important element of the local economy and wider reputation of cities. Recent research (Casadei and Gilbert Citation2018; Casadei, Gilbert, and Lazzeretti Citation2021) reviewed the extant literature on global fashion capitals and second-tier cities of fashion by identifying a set of ‘dimensions’ that mark similarities and differences in 21st century fashion cities: economic structure, human capital, education system, institutional infrastructure, retail environment and promotional media system. Working with these and giving them a one-sided accentuation, three ideal types of fashion cities were identified: the ‘manufacturing fashion city’ with an economic system focused on an extensive apparel production sector, the ‘design fashion city’ closest to conventional models of CCIs, and the ‘symbolic fashion city’ focused on place branding and symbolic production. This framework is a heuristic device to think about the mixing of production, design and symbolic elements forming contemporary fashion cities. Empirical research is now needed to move this theoretical discussion forward and understand the way these elements interact with each other in different urban contexts.

3. Methodology

The main source for the paper is 30 semi-structured interviews undertaken between June 2016 and May 2018 with prominent industry players of the London fashion ecosystem (see Appendix A). Respondents were firstly identified through a mapping exercise of key roles in each of the dimensions mentioned above. A process of snowball sampling was used for subsequent interviews. Interviewees included heads of leading fashion schools and senior figures in institutions representing and supporting fashion in London. Other interviewees included independent fashion designers and manufacturers as well as senior representatives from London’s fashion media, retailing and key museums. Research scholars engaged in studies on fashion and London were also interviewed. Respondents were questioned about their perception of the relationship between London and fashion, and interviews were organised to cover the dimensions under investigation.

All interviews ranged between thirty minutes and one hour in length, and were recorded, fully transcribed, coded and analysed. Interviewees were anonymised and speaking ‘off-record’ rather than representing their institutions or companies. The interview process had two aims. First, to investigate the rhetorical construction of London’s fashion position from different views and experiences to understand what elements mostly contribute to London’s character as a fashion centre. Second, to examine how these elements are combined in discourses of value creation and economic development of the city. The variety of actors from different segments of the industry provided us with a wide-ranging overview of the London’s relationship with fashion. In addition to semi-structured interviews, the paper draws upon government and city policy documents, reports from specialist institutions and research centres, and unpublished statistics from the UK Office for National Statistics and the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

4. Findings: industry’s discourse on London’s relationship with fashion

4.1. Creativity, distinctiveness and innovation in the city

There is a strong central narrative in the way that industry professionals understand London’s positioning in fashion’s urban geographies. That narrative draws upon London’s history, emphasizing the city’s reputation for creativity, innovation, and experimentation. London has a long-established tradition as a centre of creativity. The broad interest in culture and creativity was seen as dating back at least to the nineteenth century. For some respondents there were direct lineages from the Great Exhibition and the Victorian development of arts and design institutions:

One of the key things is that we have a history in the UK of taking the arts and creative industries quite seriously. If you go back to 1851, there was the Great Exhibition…The Science Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Natural History Museum, the Royal College of Art all came after that exhibition. It was a big spur to design and to the idea that arts and culture are important (Interview 10: Head of business school in a fashion and design education institution).

However, in discussing London’s development, respondents were usually more focused on twentieth century transformations, and particularly the cultural transformations in consumption, production and lifestyle from the 1960s, which irreversibly marked perceptions of London’s fashion ecosystem. The key tropes of ‘Swinging London’ still resonate strongly in the ways that key players identify the ongoing qualities of London fashion. This retrospective reading of the 1960s combines a number of elements. At one level the discourse draws directly upon the kinds of mythologies that were being established during the period itself by designers and entrepreneurs such as Mary Quant and John Stephens, as well as much of the contemporary media (Gilbert Citation2006). This emphasised the emergence of a new youth-focused consumer culture (a ‘Youthquake’) associated with developments in music and fashion. For some of the interviewees, although the ‘Swinging Sixties’ were short-lived, there were lasting effects on London’s reputation, and particularly on the emergence of a ‘creative wave’ of innovative fashion designers (Santagata Citation2004), with conceptual, experimental and progressive approaches. London’s prominence for sub-cultural forms from the Sixties onwards, through Glam, Punk, New Romanticism and beyond underpins lasting understandings of the city as a home to creative, extravagant and experimental consumers:

The core of London comes from these kinds of layers of the past, these ghosts of the 60 s, the 70 s punk movement and their significance. And then the 80 s period which was BodyMap…and all the culture that intertwined with club scenes and performance artists. London was and still is a city full of freedom…It drew people with curiosity from different cities within the UK and equally people from other countries. It is a comfortable place for the eccentric, where it is allowed for you to express beyond what exists (Interview 14: Head of fashion in an arts and design education institution).

Over time, this symbolic construction of London as a supposed space of creative freedom, and of openness to newness and experimentation has been an important part of its attraction (Hall Citation2000; Landry Citation2001; Pratt Citation2009). The interviews highlighted the ways in which other cities, and particularly urban governments across the world examine how London achieved its unique reputation for creativity. London is understood as giving priority to symbolic production, and particularly to fashion as an expressive art form. In some ways, London’s fashion leaders express a conventional view of the importance of synergies between fashion and other creative industries, and the importance of London’s reputation for major cultural institutions in attracting creative individuals. They also regularly highlighted the significance of London’s cultural diversity. What is significant is that this creativity is often mapped onto the detailed geography of the city, with the complexity of the cityscape itself seen as fertile soil for creativity:

There are a lot of areas, like Hackney, Shoreditch, where there is creative vibe, and people can wear what they want to wear…There are places where people can really be themselves, and I think designers find that quite an attractive prospect. London is so diverse. You have got so many different nationalities and different cultures coming together…and it is all a big melting pot, and you can be as creative as possible (Interview 1: Manufacturing firm).

A lot of designers talk about the inspiration that they gain from the streets of London…Think of Alexander McQueen and how inspired he was by what he saw on the streets of London, in the art galleries of London, in the places around the city and the atmospheres of old historic buildings…I think there is something about the physical landscape of London as a city that designers find really inspiring (Interview 25: Fashion curator in a museum).

4.2. The decline of London’s fashion manufacturing: structural changes and weaknesses

By contrast with this consistent celebration of London’s reputation for edginess, innovation and creativity, there were frequent concerns expressed about manufacturing, seen as the most problematic element of London’s fashion ecosystem by industry interviewees. Many respondents emphasised deindustrialisation, the dramatic contraction of manufacturing jobs and firms, and the shortage of productive capacity. There was an awareness of the importance of London’s history of manufacturing and its significance in past fashion ecosystems. In the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century, London was internationally renowned for tailored men’s and womenswear production, as well as ready-to-wear. At that time, many were employed in clothing manufacturing in London. While the West End was associated with the production of high-quality bespoke garments, the East End manufactured less prestigious items (Breward, Ehrman, and Evans Citation2004).

Wherever you turn to in the history of London there is always a chapter that is about fashion and manufacturing and there is the Huguenots coming over here in the 18th Century and creating Spitalfields, that used to be a huge centre of silk weaving (Interview 17: Support institution).

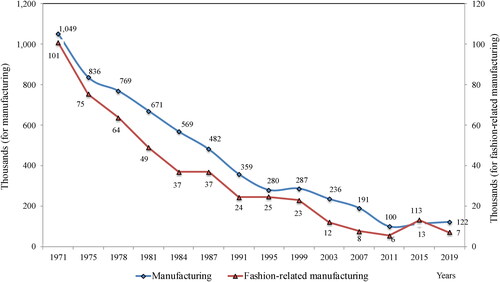

London’s deindustrialisation began earlier than much of the rest of the UK (Dennis Citation1978). Wartime destruction and disruption of the East End rag-trade and larger-scale factory production encouraged movement of clothing manufacture out of London, particularly to the Midlands and the North (Bide Citation2020). In a sense London had already undergone an analogous internal process to offshoring, losing much of its large-scale apparel production to other parts of the UK in the post-war period. This reduction accelerated in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, reducing employment to less than 6,000 workers in the 2010s. As shows, this is a sustained and long-term decline, both for fashion-related production and total manufacturing.

Figure 1. Employment trend in manufacturing and fashion manufacturing, London, 1971–2019.

Source: Authors’ elaboration using data from the Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES), Annual Business Inquiry (ABI), Annual Employment Survey (AES) and Census of Employment (CoE) – Office for National Statistics.

Notes: Data from 1971 to 1981 are defined with code 7. Textiles, Leather and Clothing (SIC 1968 – CoE). Data from 1982 to 1991 with codes 43. Textile Industry, 44. Manufacture of leather/leathergoods and 45. Footwear/Clothing Industry (SIC 1980 – CoE). Data from 1992 to 2008 with codes 17. Manufacture of Textile, 18. Manufacture apparel; dressing/dyeing fur and 19. Tanning/dressing of leather, etc. (SIC 1992 – AES and ABI). Data from 2009 to 2015 with codes 13. Manufacture of Textiles, 14. Wearing Apparel and 15. Manufacture of Leather and Related Products (SIC 2007 – BRES). Data are rounded to the nearest 100 according to the disclosure rules of BRES.

As well as commenting on this overall decline, interviewees also drew attention to significant structural changes that have accompanied the shrinking of the industry. For example, in the period from 1987 to 2007,Footnote1 the percentage of establishments with more than 10 people decreased from 36% to 8% ().

Table 1. Frequency distribution of establishments by employment size, London, 1987 and 2007.

Interviewees also drew attention to significant structural changes associated with decline. Large factories have been replaced by smaller-sized firms, often for higher-quality products. From the 1980s, the restructuring of fashion production has been the object of specific public policies discourses (Greater London Council (GLC)), Citation1985), with a recent focus on developing new types of high-end manufacturing in London (British Fashion Council (BFC) Citation2015; Centre for Fashion Enterprise (CFE)), Citation2009; Karra Citation2008; UK Fashion & Textile Association (UKFT)), Citation2016; Virani and Banks Citation2014). This has had some effect, and several respondents indicated that in the past decade it has become easier for independent London designers to find high-end manufacturing facilities. These facilitate sampling, bespoke production, and small batch runs of designs. Other interviewees also remarked on signs of manufacturing reshoring (Robinson and Hsieh Citation2016), with both renowned designers and high-street retailers moving parts of production processes back to London because of shorter lead times, higher flexibility and control of production and environmental issues:

There definitely was a decline in the 90 s, but it is slowly backing up there. We are seeing it, we have got people like Asda, Primark, Matalan, which are huge companies that have predominantly done most of their production overseas, they have all come to us recently, so it is promising (Interview 1: Manufacturing firm).

However, both London and the broader UK still lack high-volume production able to support a large number of products. Many interviewees referenced the high cost of local manufacturing as one of the main barriers. Micro-sized retailers and designers, particularly those in the early stages of their career, are very unlikely to be able to afford to produce in London. Some highlighted long-running concerns about the business relationships between local manufacturers and designers, particularly differences in expectations about production standards and flexibility. A connected issue was the lack of specialist skills, technical expertise, and equipment in the London manufacturing sector:

The first weakness is that it is still relatively expensive to manufacture in London, so a lot of designers get their stuff made abroad. There are some manufacturing specialisation techniques that really London does not necessarily have (Interview 16: Support institution).

Some interviews drew attention to the importance of migrant labour in addressing skill-shortages, suggesting that these were likely to be exacerbated by Brexit:

If you go into most factories in London, something like 70% of their staff are Eastern European predominantly from Romania and Hungary. Because they have got the sewing skills, because their education system still teaches sewing skills. So, they have got a lot of high-quality staff. There is not an automatic pool of talent here, so we do not have lots of very talented sewing machinists…So that is one thing, the other thing on the manufacturing side is that we do not make everything in the UK. So, we do not have the talent, we do not have the volume, and there are loads of things that we do not make in the UK that we need to import (Interview 17: Support institution).

Interviewees also expressed concerns about support for manufacturing from local and city government, with a strong sense that fashion is primarily seen by government as a creative industry rather than part of the local productive base:

There is not that support and infrastructure and belief in fashion as a not just a creative industry, but a manufacturing industry and a source of employment. Lots of people just see fashion as that glamorous end with dresses on the catwalk or celebrities. They do not see the rest of it, they do not see the tailors that work here, the leather workers that work here, the shoe manufacturers that work here and all that sort of stuff (Interview 17: Support institution).

4.3. The education system: a conceptual approach to fashion design

There was a strong emphasis on the education system as a powerful engine for the London fashion economy. London is internationally acknowledged as a place of learning, particularly in creativity and design (Comunian and Faggian Citation2014). Building on established reputations forged in mid-twentieth century art schools, notably the Royal College of Art and Central Saint Martins (Breward, Ehrman, and Evans Citation2004), London fashion schools are now routinely placed high in world-ranking exercises (see for example, Business of Fashion (BOF)) Citation2019). John Galliano, Alexander McQueen, Stella McCartney and Christopher Bailey are among the many fashion designers trained in these schools in recent decades (British Fashion Council (BFC)), Citation2015; Virani and Banks Citation2014). This reputation means that London attracts international fashion students:

Its reputation as a centre for fashion education is deeply important and connected to its reputation as a centre of fashion. In the sense that people from all over the world come to London’s fashion colleges which really are some of the best in the world…I think that is part of the reason why so many interesting young graduates then go on to start their businesses, their fashion companies in London (Interview 25: Fashion curator in a museum).

Because of their established reputation, these institutions function as important generators of symbolic capital for aspiring designers. They offer the possibility of visibility and recognition in the local industry and media system, and networking with key actors in the sector. In this respect, in addition to internships and sponsorship opportunities, graduate fashion shows function as platforms for students who want to gain media attention in the early stages of their career.

We collaborate with fashion houses, fashion businesses and retailers. Mentoring by industry representatives and creative professionals is important. We also receive support from the British Fashion Council, which is very important to us. Students get support in terms of feedback on their creative work and opportunities to work with businesses. There may be also occasional sponsorship opportunities. The dialogue with the industry and creative practitioners is really important to us (Interview 13: Head of an arts and design education institution).

The global reputation of these schools was often attributed to their promotion of creativity and artistic values, and to a conceptual approach to fashion that supports high levels of innovation, experimentation, originality and critical thinking. Fashion design education in London is challenging, pushing students out of their comfort zone, providing high levels of freedom and the absence of rigid aesthetic rules, emphasising risk and strongly individuated design identity.

Many art schools are incorporated into larger multidisciplinary universities, where fashion design is one of the subjects within a broader creative arts portfolio…This provides a fertile soil where creative people come together and work or experiment in areas that are not necessarily their own disciplinary background. It is really important to create, maintain and protect spaces where creativity and experimentation can flourish without a primary commercial concern, where people can test out things without taking too much of a risk initially. Art schools have an important role to play in offering this kind of environment and to nurture a creative mind set…We focus on the design values that drive London as a fashion city (Interview 13: Head of an arts and design education institution).

Designers graduating from these schools are often more interested in a ‘fashion to be seen’ than a ‘fashion to be worn’ valuing originality and expressive creativity above the marketability of products (Volonte Citation2012). Fashion is regarded more as a form of art than of economic production. This education environment is primarily aimed at promoting the figure of the independent fashion designer aspiring to open their own business (Pratt et al. Citation2012; Volonte Citation2012). A number of respondents stressed the preference of many students to open their own companies rather than working within large and established fashion houses:

New York’s schools have a reputation for building graduates that can slot really easily into industry and become the soldier in the workforces of big companies…London is generally thought to be the city to study in if you want to become an individual brand yourself. I think that is part of why even though it is really hard still to establish a fashion business in London, people come here to study, and why they then start their businesses here because…is that goal of becoming the next Alexander McQueen (Interview 25: Fashion curator in a museum).

Many respondents discussed a downside to this emphasis on expressive creativity, suggesting weaknesses in commercial, managerial and technical training, an issue highlighted in previous research (D’Ovidio Citation2016; Rieple and Gornostaeva Citation2014; Volonte Citation2012). Graduates from London-based educational providers are seen as having weaker understanding of business and entrepreneurial strategies, necessary to attract investments, gain market attraction and compete in the global market. However, in the interviews there was a strong assertation of the primacy of creativity over business skills:

There has always been a gap between the moment of education and the moment of business. You cannot teach business alongside design really well. I do not think the industry needs more people who understand the industry…I think if you are going to have your business you can learn some basics, but you have to learn yourself. I want that students come here mostly to examine their sense of self of fashion designers and…develop their vision and opinion and feel confident about it (Interview 14: Head of fashion in an arts and design education institution).

Education gives you a platform to show your work to the industry so that you can start getting into the industry. But it does not provide business support. You are learning everything in terms of running a business or a label as you go along…All the business side comes later. But I think it is good because when you are studying you are working on being creative and having a strong design identity, and without that you cannot really have a label (Interview 5: Fashion designer)

However, for some, the issues with London design education were not so much about weaknesses in business training, so much as technical and artisanal skills, such as pattern cutting, pressing, and finishing. Lack of competence in these skills could be a barrier to developing a career, and an issue in developing relationships with retailing and manufacturing companies:

Many designers that leave university…cannot take it to the next level because they do not have the technical skills to make almost a wearable, viable collection that people are actually going to wear in real life. It is not just about the design side…if they want to be a designer, they still need a viable business…they almost need to take a step back and learn the technical skills (Interview 1: Manufacturing firm).

4.4. The downside of creativity: a brain drain of fashion design talent?

Many respondents emphasised that one of the main weaknesses of London’s fashion ecosystem is a consequence of both its highly creative environment, but also its weaknesses in manufacturing and business infrastructures. This ecosystem was contrasted with Paris, Milan and New York, which all have many more established large and medium-sized fashion businesses, and larger, more skilled production sectors. Students graduating from London’s fashion design schools struggle to find niches in the London fashion industry. With the exception of Burberry, in London there are no high-end fashion design companies large enough to support significant numbers of graduates. There were also concerns expressed that immigration restrictions limit the prospects for international students to stay and establish themselves in London, and that Brexit will restrict this further.

It is not a city where you have large fashion brands. If you go to Paris, New York or Milan they have 30 or 40 big brands, the most famous fashion bands, the luxury brands in the world they should be in those cities. In London we only have one, which is Burberry, all the other ones are relatively small (Interview 19: Founder of e-commerce platform).

A system primarily oriented towards creativity and artistic values does not facilitate the setting up and consolidation of businesses, despite a plethora of institutions aimed at supporting and sustaining emerging fashion designers. Virani and Banks (Citation2014) identify more than twenty institutions that support fashion designers in networking, securing funding, showcasing collections, as well as providing mentoring, resources and knowledge. These include the British Fashion Council, the Centre for Fashion Enterprise, Fashion East, and the Centre for Sustainable Fashion. However, emerging designers face significant obstacles, that include the narrow and relatively expensive (compared to competing fashion capitals) manufacturing base, poorly suited to supporting start-up businesses. The high cost of living, and particularly a hyper-capitalised property market, was seen as an almost insurmountable obstacle to fashion start-ups. These costs and the precarity of early fashion careers make financial investment almost impossible to secure, and there are high rates of business failure:

I think creativity is one of its positives, but it is also one of its negatives in many ways. We tend to generate an awful lot of very creative people who are very good at fashion design, but they are not very good at running fashion businesses. The number of fashion business failures in the UK is very high and the vast majority of those are based in London (Interview 17: Support institution).

It is very hard for any fashion business to mature…those other capitals have got strengths which help them, so they have got manufacturing, or they are very much about commerce to begin with anyway, so they are very focused on that. London is all about the new designers with the new ideas that are pushing fashion somewhere different, that is not really going to be commercial (Interview 12: Head of fashion in an arts and design education institution).

Some fashion designers have moved to the outskirts of London, or other British cities, seeking more affordable property for new businesses:

There are lots of people like us that for one reason or another have made the decision to move our business outside of London, because it is hard to cover all those running costs, because London is very expensive…. You pay a premium for being in the capital, and if you are located centrally or in a popular area like East London, you pay a real premium for space, and that is quite challenging as a small business (Interview 8: Fashion Designer).

Others, however, are moving beyond to find opportunities beyond the UK, again often pushed by costs, but also increasingly by Brexit concerns:

The environment for emerging designers in London is getting trickier because the city has become so much more expensive. Most creative talent now is moving abroad to Berlin, to Antwerp, to Barcelona, so the cities where it is easier for them to survive. Then of course you have the whole Brexit scenario which is also a huge problem. Eight or nine years ago when we started, most of our designers were living within five to ten minutes from where our office is, and now most of these have moved to outside of the country or outside of London (Interview 19: Founder of e-commerce platform).

Data from HESA partially confirm this trend. Indeed, as shown in , a relatively high proportion (34.4%) of undergraduate and postgraduate students enrolled in fashion design courses in London-based educational institutions in 2014/2015Footnote2 were already employed out of London six months after the completion of their studies. Moreover, most of them were employed on a permanent or open-ended contract, while only 4% started their own business (). If we look at the size of the fashion design sectorFootnote3, several studies have emphasised its relatively narrow dimension compared to other aspects of the broader fashion industry (BOP Consulting Citation2017).

Table 2. Location of employment of students enrolled on fashion design programmes in London, 2014–2015.

Table 3. Type of employment of students enrolled on fashion design programmes in London, 2014–2015.

Table A1. Semi-structured interviews.

4.5. Shaping the image of the city: retail, media and museums

There was a strong sense among interviewees of wider elements of London’s fashion ecosystem, emphasising London’s significance as a centre for retailing and consumption, and its importance in the symbolic production of global fashion. Interviewees emphasised that a wide variety of shopping opportunities, fashion-related media and events, and also museums of global reputation play a key role in building and disseminating powerful symbols that link London with the idea of fashion.

Respondents highlighted fashion retail as a significant factor shaping London’s reputation stressing the long-term importance of the sector. In 2015, fashion retail and distribution in London accounted for a GVA of £4.70 billion, 85% of the total economic value of the fashion sector (BOP Consulting Citation2017). London combines long-established department stores with prestigious fashion districts of high-end boutiques and luxury brands like New Bond Street, Mayfair and Knightsbridge. Respondents also indicated London’s sustained profile for ‘high-street’ fashion. This range of shopping opportunities pulls in millions of international and domestic tourists and attracts fashion houses wanting to benefit from symbolic association with London. Some respondents drew attention to the role retailers play in supporting local designers, both selling their collections and through promotional events and talent-pathway schemes.

I think one of the other key things is that London is also a major sort of destination city for tourists not just from within the UK, but also from around the world. I think one of the key things they come for is retail. I think it is really interesting that a lot of major British brands have flagship stores in the UK, particularly in London. But I also think it is really important to note that a lot of international brands want to be seen in London as well, because that gives them ‘the London feel’ to it as well (Interview 12: Head of fashion in an arts and design education institution).

Retailers are really important especially Topshop with Newgen. They usually invest a lot on new and emerging designers. It is a kind of symbolic element, the fact to have been selected by retailers it is something that gives an important symbolic value to fashion designers. Retailers do an important financial investment in fashion designers and are a very important aspect of the city of London (Interview 30: Researcher).

While medium- and large-sized high-street companies have dominated the retailing scene, more recently, temporary and permanent shops of independent fashion retailers and designers selling cutting-edge, extravagant and innovative collections have emerged in new fashion hubs in the city, particularly in East London. One respondent stressed the layers of London retailing and the importance of local knowledge:

It’s a huge shopping destination for all sorts of people. You know people fly in from China just to come shopping in London…So there is the retail aspect in terms of its global perception, but also because there are loads and loads of really good independent shops…So I think it is creativity, its retail scene, it is the history of fashion (Interview 17: Support institution).

A strong promotional system supports London’s fashion industry by raising its symbolic value internationally. London Fashion Week attracts high levels of investment and media coverage and contributes to generating high economic and symbolic value. Respondents again emphasised the distinctiveness of these collections in terms of creativity, experimentation and cutting-edge fashion design. London Fashion Weeks and other events were seen as part of a powerful and integrated promotional system, that includes various media and channels for the dissemination of symbolic associations of the city with the creativity and innovation:

London is where it is always about the latest designer…there is almost that protectionism I guess in Paris, in Milan certainly, in terms of promoting only home-grown talent, whereas I think London, we just want to see exciting things, we do not care where they come from. I think we just want to see exciting, new interesting things; we do not care if they are wearable or not wearable, commercial or not commercial, too expensive (Interview 12: Head of fashion in an arts and design education institution).

The production, distribution and consumption side of fashion are fuelled by venues for fashion shows and displays, underpinned by a rich network of media outlets that promote fashion. The critics who work for the papers, for the broadcast industry, for online platforms and for social networks play an important part in building a promotional and critical discourse around fashion creations whether these are haute-couture or prêt-à-porter. In short, fashion design, business, trade, education and culture work hand and glove here in a densely interwoven infrastructure that has shaped London as a creative centre (Interview 13: Head of an arts and design education institution).

London’s museums and other cultural institutions are seen as vital elements in this symbolic promotion of London fashion. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) hosts the largest permanent collection of textiles and fashion in the world, with a particular focus on European and British fashion. It has played a prominent role in staging exhibitions that become international events, reinforcing London’s position in the symbolic hierarchies of fashion cities. Since 1971, when the first high-profile exhibition was organized (‘Fashion: An anthology’), the regular V&A fashion-related exhibitions have attracted an increasing number of visitors. These have highlighted innovative London designers, but have also celebrated London’s importance for street and club culture and distinctive sub-cultural fashion, as well as exhibitions of fashion history. ‘Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty’ at the V&A in 2015, attracted 493,043 visitors in just five months, becoming the most visited exhibition in museum’s history. Since the late 1990s, the V&A has also organised ‘Fashion in Motion’, a series of live fashion catwalks showcasing London-based designers. In addition to the V&A, the Museum of London has a large fashion collection focused on clothes and textiles made, sold and worn in the city from the sixteenth century. But respondents also highlighted the contributions to the symbolic construction of London made by a much wider range of museums, galleries and cultural institutions:

What is so exciting is how many institutions here are telling fashion stories. I mean, in New York you have the Met and FIT, but in London you have the V&A, you have the Museum of London, you have the Fashion and Textile Museums in Bermondsey. You have galleries like the Esoteric Collection that also occasionally references fashion. The Jewish Museum has fantastic exhibitions of fashion in London. Somerset House, that is super important in recent years. It is amazing how many institutions are presenting really thought provoking, innovative projects. That creates a fantastic sort of stage set for fashion (Interview 25: Fashion curator in a museum).

5. Discussion and conclusions

This paper investigates the interpretation of London’s fashion ecosystem by leading industry actors, in order to understand the way creativity, manufacturing and symbolism interact in that ecosystem. What is striking is the coherence of the interpretation offered by respondents, even though they come from different ‘dimensions’ of London’s fashion ecosystem. Compared with the other fashion capitals, Paris, New York and Milan, fashion leaders in London place much less emphasis on particular business models or production networks. Instead, London’s distinctive strengths are regarded as its focus on creativity, artistic values and forms of urban symbolism. There is strong awareness of the power of the symbolic economy, and its relative autonomy from the production of material fashion. Additionally, there is recognition of the wider elements of the London’s fashion ecosystem, particularly the apparatus that promotes the idea of London fashion, perhaps above the production of material fashion. Respondents understandably stressed the importance of London Fashion Weeks, the local fashion press and new media. But they also discussed the ways that cultural institutions, particularly fashion exhibitions and collections in internationally recognised museums, provide powerful associations between London and fashion. This idea of the fashion city is therefore bound up with consumption of the city as a site of fashion culture. London’s importance as a retail destination is more associated with international brands and a long-established high street section, although specialist retailers selling cutting-edge fashion styles particularly in East London have a prominence that is more about symbolic significance than economic contribution.

Design has an ambivalent position in this understanding of the London’s fashion ecosystem. Interviewees emphasised that the fashion design sector is relatively narrow and not adequately supported by a weak, expensive and non-specialised production system. London’s fashion education system is seen as emphasizing individual creativity above business and technical aspects. For some this is part of a more conceptual approach to fashion that regards it as an important art form. Fashion designers value originality, creativity and experimentation more than the marketability of products. This contributes to London’s symbolic standing but leaves limited commercial opportunities. The effects of this tension between creativity and business, and the weakness of the manufacturing sector, are seen as being exacerbated by the difficulties of securing investment for start-up design companies as well as the high costs of commercial and residential property. The effects of an exodus of design talent are seen as mixed; those designers who have moved out of London to set up new businesses or to find employment in large European and American fashion houses are both an indication of London’s weaknesses, but also its role as a centre of creative talent.

In short, London is understood more as a site of symbolic production through unique creative learning experiences, a wide variety of shopping opportunities, renowned showcase events, and fashion exhibitions, than a fashion city that is focused on the design and production of garments or the development of international brands. Certainly, among the major fashion centres, London is an extreme example of deindustrialisation and a shift towards an ecosystem focused on image-producing activities, where the production of apparel and even the design of clothing for production are absent or limited. Recent theorisations of ‘ideal types’ of fashion cities suggest not so much a singular fashion city ecosystem, as three distinctive forms: the ‘manufacturing fashion city’, the ‘design fashion city’ and the ‘symbolic fashion city’ (Casadei, Gilbert, and Lazzeretti Citation2021). Weberian ideal types are, of course, idealised accentuations used to develop analytical constructs, but it is striking how close this dominant consensus about London’s fashion ecosystem comes to describing a pure form of the symbolic fashion city.

This stimulates reflection on the recent widespread approach in policy agendas of considering fashion as a resource for place branding. We see that London’s strong emphasis on forms of aesthetics and symbolism has led to weaknesses in relation not only to production but also the wider business of fashion, particularly the design and brand sectors. However, London’s established tradition in fashion, highly rooted in perceptions of an urban culture characterised by creativity and experimentation, has allowed this city to maintain its reputation in global fashion geographies. It is not clear how readily this model can be transferred to other cities. London’s reputation is in part based upon past experiences of urban difference, experimentation and even cultural dissent that are difficult if not impossible to replicate as goals of urban policy. London itself, with its hypercapitalized property markets, increasingly unaffordable housing and limited opportunities for innovative bottom-up renewal of its fashion tradition, runs the risk of becoming an empty shell trading on increasingly historic tropes of its fashionability. There may be limits to the extent any city can sustain a purely symbolic reputation.

Such concerns may well be strengthened in the current context. These interviews were conducted in a distinctive period, after the Brexit referendum but before either the end of the transition period or the Covid-19 pandemic. The final implementation of Brexit was mentioned by respondents as a major concern, not only exacerbating some of the weaknesses of manufacturing and the difficulties of establishing new design businesses, but also potentially undermining identified strengths (Casadei and Iammarino, Citation2021). New obstacles to the recruitment of international fashion students, and disincentives for European tourists to visit the city, are combined with a wider sense of global marginalisation and inward-lookingness, at odds with many of the established tropes of London as fashion capital. The pandemic has been particularly severe on London retailing with collapsing sales, bankruptcies and job losses, particularly in the ‘high street’ sector (Financial Times Citation2020; The Guardian Citation2020). London’s fashion economy has experienced significant shocks in the past, and it is important not only to analyse how its fashion ecosystem is changed, but also how internal and external perceptions of the city change. The interviews here capture a particular moment in London’s history as a fashion city, but perhaps also mark a point before fundamental transformation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 We specifically look at 2007 rather than at more recent years to make data comparable across different employee size bands.

2 Data were retrieved (through a temporary and personal authorisation from HESA) from the Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education Providers 2014/15 dataset of HESA. The survey provides information about the employment and further study activities of local higher education leavers approximately six months after completing their studies. The response rates are set to ensure that data are suitable for publication and that the results genuinely reflect the outcomes for students leaving HE providers.

3 To date, there are no dedicated Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes associated with fashion design and therefore it is not possible to separate this element from the broader category 74.10 ‘Specialised Design Activities’ with a reasonable degree of accuracy. Moreover, elements of designer fashion are also included in most of the clothing and footwear manufacturing-related codes.

References

- Aspers, P. 2010. “Using Design for Upgrading in the Fashion Industry.” Journal of Economic Geography 10 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp030

- Bide, B. 2020. “London Leads the World: The Reinvention of London Fashion in the Aftermath of the Second World War.” Fashion Theory 24 (3): 349–369. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2020.1732015

- BOP Consulting. 2017. “The East London Fashion Cluster.” Draft Strategy and Action Plan. Report, BOP Consulting, UK.

- Breward, C., and D. Gilbert. 2006. Fashion’s World Cities. Oxford: Berg.

- Breward, C., E. Ehrman., and C. Evans. 2004. The London Look: Fashion from Street to Catwalk. London: Museum of London and Yale University Press.

- British Fashion Council (BFC). 2015. “High-End Designer Manufacturing Report.” Report, British Fashion Council, UK.

- Business of Fashion (BOF). 2019. “The Best Fashion Schools in the World 2019.” Accessed 10 November 2020. https://www.businessoffashion.com/education/best-schools/undergraduate/fashion-design.

- Casadei, P., and D. Gilbert. 2018. “Unpicking the Fashion City: Global Perspectives on Design, Manufacturing and Symbolic Production in Urban Formations.” In Creative Industries and Entrepreneurship: Paradigms in Transition from a Global Perspective, edited by L. Lazzeretti and M. Vecco, 79–100. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Casadei, P., and N. Lee. 2020. “Global Cities, Creative Industries and Their Representation on Social Media: A Micro-Data Analysis of Twitter Data on the Fashion Industry.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (6): 1195–1220. doi:10.1177/0308518X20901585

- Casadei, P., and S. Iammarino. 2021. “Trade policy shocks in the UK textile and apparel value chain. Firm perceptions of Brexit uncertainty.” Journal of International Business Polic 4 (2): 262–285.

- Casadei, P., D. Gilbert, and L. Lazzeretti. 2021. “Urban Fashion Formations in the Twenty First Century: Weberian Ideal Types to Unravel the Fashion City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 45 (5): 879–896. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12961

- Centre for Fashion Enterprise (CFE). 2009. “High-end Fashion Manufacturing in the UK – Product, Process and Vision. Recommendations for Education, Training, and Accreditation.” Report, Centre for Fashion Enterprise, UK.

- Chilese, E., and A. P. Russo. 2008. “Urban Fashion Policies: Lessons from the Barcelona Catwalks.” EBLA Working Paper no. 3/2008. International Centre for Research on the Economics of Culture, Institutions and Creativity (EBLA), University of Turin, Turin.

- Comunian, R., and A. Faggian. 2014. “Creative Graduates and Creative Cities: Exploring the Geography of Creative Education in the UK.” International Journal of Cultural and Creative Industries 1 (2): 18–34.

- Crewe, L., and J. Beaverstock. 1998. “Fashioning the City: Cultures of Consumption in Contemporary Urban Spaces.” Geoforum 29 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1016/S0016-7185(98)00015-3

- Currid, E. 2006. “New York as a Global Creative Hub: A Competitive Analysis of Four Theories on World Cities.” Economic Development Quarterly 20 (4): 330–350. doi:10.1177/0891242406292708

- D’Ovidio, M. 2016. The Creative City Does Not Exist. Critical Essays on the Creative and Cultural Economy of Cities. Milano: Ledizioni.

- Dennis, R. 1978. “The Decline of Manufacturing Employment in Greater London: 1966-74.” Urban Studies 15 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1080/713702294

- Evans, Y, and A. Smith. 2006. “Surviving at the Margins? Deindustrialization, the Creative Industries, and Upgrading in London’s Garment Sector.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (12): 2253–2269. doi:10.1068/a38285

- Financial Times. 2020. “Up to 240,000 UK Fashion Jobs at Risk, Warns Industry Body.” Accessed 4 December 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/02f89a4b-3bde-492d-98ac-15d638b209fe.

- Gilbert, D. 2006. “The Youngest Legend in History’: Cultures of Consumption and the Mythologies of Swinging London.” The London Journal 31 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1179/174963206X113089

- Gilbert, D. 2013. “A New World Order? Fashion and Its Capital in in the Twenty-First Century.” In Fashion Cultures Revisited: Theories, Explorations, and Analysis, edited by S. Bruzzi and Gibson P. Church, 11–30. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Godart, F. 2014. “The Power Structure of the Fashion Industry: Fashion Capitals, Globalization and Creativity.” International Journal of Fashion Studies 1 (1): 39–55. doi:10.1386/infs.1.1.39_1

- Greater London Council (GLC). 1985. The London Industrial Strategy. Greater London Council (GLC).

- Grodach, C. 2017. “Urban Cultural Policy and Creative City Making.” Cities 68: 82–91. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.05.015

- Hall, P. 2000. “Creative Cities and Economic Development.” Urban Studies 37 (4): 639–649. doi:10.1080/00420980050003946

- Hauge, A. 2012. “Creative Industry: Lacklustre business – Swedish Fashion Firms’ Combination of Business and Aesthetics as a Competitive Strategy.” Creative Industries Journal 5 (1–2): 105–118. doi:10.1386/cij.5.1-2.105_1

- Heim, H., T. Ferrero-Regis, and A. Payne. 2021. “Independent Fashion Designers in the Elusive Fashion City.” Urban Studies 58 (10): 2004–2022. doi:10.1177/0042098020930937

- Huang, K. C., T. S. Hu, J. Y. Wang, K. C. Chen, and H. M. Lo. 2016. “From Fashion Product Industries to Fashion: Upgrading Trends in Traditional Industry in Taiwan.” European Planning Studies 24 (4): 762–787. doi:10.1080/09654313.2015.1126556

- Jansson, J., and D. Power. 2010. “Fashioning a Global City: Global City Brand Channels in the Fashion and Design Industries.” Regional Studies 44 (7): 889–904. doi:10.1080/00343400903401584

- Karra, N. 2008. “The UK Designer Fashion Economy. Value Relationships – Identifying Barriers and Creating Opportunities for Business Growth.” Report UK.

- Khan, R. 2019. “Be Creative’ in Bangladesh? Mobility, Empowerment and Precarity in Ethical Fashion Enterprise.” Cultural Studies 33 (6): 1029–1049. doi:10.1080/09502386.2019.1660696

- Landry, C. 2001. “London as a Creative City.” In: Conference Cultures of World Cities, Central Policy Unit. Hong Kong, July 2001.

- Larner, W., M. Molloy, and A. Goodrum. 2007. “Globalization, Cultural Economy and Not- so-Global Cities: The New Zealand Designer Fashion Industry.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25 (3): 381–400. doi:10.1068/d1103

- Lazzeretti, L., F. Capone, and P. Casadei. 2017. “The Role of Fashion for Tourism: An Analysis of Florence as a Manufacturing Fashion City and beyond.” In Tourism in the City: Towards an Integrative Agenda on Urban Tourism, edited by N. Bellini and C. Pasquinelli, 207–220. New York: Springer.

- Lee, N, and E. Drever. 2013. “The Creative Industries, Creative Occupations and Innovation in London.” European Planning Studies 21 (12): 1977–1997. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722969

- Leslie, D., S. Brail, and A. M. Hunt. 2014. “Crafting an Antidote to Fast Fashion: The Case of Toronto’s Independent Fashion Design Sector.” Growth and Change 45 (2): 222–239. doi:10.1111/grow.12041

- Martínez, Javier Gimeno. 2007. “Selling Avant-Garde: How Antwerp Became a Fashion Capital (1990–2002).” Urban Studies 44 (12): 2449–2464. doi:10.1080/00420980701540879

- McRobbie, A. 2013. “Fashion Matters Berlin: city-Spaces, Women’s Working Lives, New Social Enterprise?” Cultural Studies 27 (6): 982–1010. doi:10.1080/09502386.2012.733171

- Melchior, M. R., L. Skov, and F. F. Csaba. 2011. “Translating Fashion into Danish.” Culture Unbound 3 (2): 209–228. doi:10.3384/cu.2000.1525.113209

- Merlo, E, and F. Polese. 2006. “The Emergence of Milan as an International Fashion Hub.” The Business History Review 80 (3): 415–447. doi:10.1017/S0007680500035856

- Potvin, J. 2009. The Places and Spaces of Fashion, 1800-2007. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Power, D, and A. Scott. 2004. Cultural Industries and the Production of Culture. London: Routledge.

- Pratt, A. 2009. “Urban Regeneration: From the Arts ‘Feel Good’ Factor to the Cultural Economy: A Case Study of Hoxton.” London. Urban Studies 46 (5–6): 1041–1061. doi:10.1177/0042098009103854

- Pratt, A., P. Borrione, M. Lavanga, and M. D’Ovidio. 2012. “International Change and Technological Evolution in the Fashion Industry.” In Essays and Research. International Biennial of Cultural and Environmental Heritage, edited by M. Agnoletti, A. Carandini and W. Santagata, 359–376. Florence: Badecchi & Vivaldi.

- Rantisi, N. M. 2004. “The Ascendance of New York Fashion.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28 (1): 86–106. doi:10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00504.x

- Rantisi, N. M. 2011. “The Prospects and Perils of Creating a Viable Fashionable Identity.” Fashion Theory 15 (2): 259–266. doi:10.2752/175174111X12954359478843

- Rieple, A., and G. Gornostaeva. 2014. “Fashion Design in London: The Positioning of Independent Designers within the Fashion Field.” Archives of Design Research 27 (3): 37–47.

- Robinson, P. K, and L. Hsieh. 2016. “Reshoring: A Strategic Renewal of Luxury Clothing Supply Chains.” Operations Management Research 9 (3–4): 89–101. doi:10.1007/s12063-016-0116-x

- Rocamora, A. 2009. Fashioning the City: Paris, Fashion, and the Media. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

- Rogerson, C. M. 2006. “Developing the Fashion Industry in Africa: The Case of Johannesburg.” Urban Forum 17 (3): 215–240. doi:10.1007/s12132-006-0010-y

- Santagata, W. 2004. “Creativity, Fashion, and Market Behaviour.” In Cultural Industries and the Production of Culture, edited by D. Power and A. Scott, London: Routledge, 75–90.

- Scott, A. 2002. “Competitive Dynamics of Southern California’s Clothing Industry: The Widening Global Connection and Its Local Ramifications.” Urban Studies 39 (8): 1287–1306. doi:10.1080/00420980220142646

- Scott, A. 2014. “Beyond the Creative City: Cognitive-Cultural Capitalism and the New Urbanism.” Regional Studies 48 (4): 565–578. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.891010

- Simmel, G. 1904. “Fashion.” International Quarterly 10 (1): 130–155.

- Skivko, M. 2013. “Fashion Metaphors for the City: The Discourse of Urban Representations by Fashion Phenomenon.” The Journal of Urbanism 2 (27): 1–5.

- Skov, L. 2011. “Dreams of Small Nations in a Polycentric Fashion World.” Fashion Theory 15 (2): 137–156. doi:10.2752/175174111X12954359478609

- The Guardian. 2020. “UK Fashion Industry Pleads for More Aid to Survive Covid-19 Crisis.” Accessed 4 December 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2020/may/13/uk-fashion-industry-pleads-for-more-aid-survive-coronavirus-crisis

- UK Fashion & Textile Association (UKFT). 2016. “London Manufacturers Manifesto.” Report, UKFT.

- Virani, T. E, and M. Banks. 2014. “Profiling Business Support Provision for Small, Medium and Micro-Sized Enterprises in London’s Fashion Sector.” Creativeworks London Woking Paper.

- Volonte, P. 2012. “Social and Cultural Features of Fashion Design in Milan.” Fashion Theory 16 (4): 399–431.

- Weller, S. 2008. “Beyond “Global Production Networks”: Australian Fashion Week’s Trans Sectorial Synergies.” Growth and Change 39 (1): 104–122. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2257.2007.00407.x

- Weller, S. 2013. “Consuming the City: Public Fashion Festivals and the Participatory Economies of Urban Space in Melbourne, Australia.” Urban Studies 50 (14): 2853–2868. doi:10.1177/0042098013482500

- Williams, S., and E. Currid-Halkett. 2011. “The Emergence of Los Angeles as a Fashion Hub: A Comparative Spatial Analysis of the New York and Los Angeles Fashion Industries.” Urban Studies 48 (14): 3043–3066. doi:10.1177/0042098010392080

- Wubs, B., M. Lavanga, and A. Janssens. 2020. “Letter from the Editors: The past and Present of Fashion Cities.” Fashion Theory 24 (3): 319–324. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2020.1732012