Abstract

This paper locates audience engagement in the act of content creation and considers the levels of engagement that content creation could engender. It explicates the different types of content creators defined in the literature and examines motivating factors for the production of content in a Chinese context. It argues that while some content creators seek to draw attention to the series they support, in other cases the engagement with the international television series is not fully motivated by a desire to interact with the international content and direct audiences to it. Rather, content creators are motivated by a desire to gain exposure for their own craft or to develop transferable skills that help them move between the different categories of content creators. In doing so, we argue that international series can tap into these ‘cultural intermediaries’ (Hutchinson Citation2017).

1. Introduction

Previous studies (Gilardi et al. Citation2018) sought to understand Chinese audience engagement with imported television series distributed online. Drawing upon definitions of engagement outlined by Ahva and Hellman (Citation2015) as operating at ‘interactive’ and ‘interpretive’ levels (p. 670), audiences were characterised as:

(1) viewers, wherein engagement involves awareness of the series and is measured through ratings; (2) participants, wherein engagement involves commentary and social media activity and is measured through comment volume; and (3) co-creators, wherein engagement involves active construction of meanings and is measured through quality and proliferation of content (Gilardi et al. Citation2018, 216–217).

In Anglophone literature the notion of audience as co-creators is conceptually aligned with interpretative engagement (Ahva and Hellman Citation2015), their creations defined as user generated content, with the quality of content produced by co-creators varying depending on the technical skills of the person creating it. The quality of the work therefore does not determine its definition; user generated content can be ‘amateur’ or ‘professional’ depending on the skill of the co-creator. In the Chinese literature, however, quality is considered to be a differentiating factor, with definitions of content determined by its quality. Definitions of content in both Anglophone and Chinese literature are, therefore, first discussed to establish the conceptual foundation of the study. The discussion highlights three categories that are utilised in the Chinese context: user generated content (UGC), professionally generated content (PGC), and occupationally generated content (OGC).

As the paper considers the work of co-creators to be a form of engagement, it explores the motivating factors that drive these co-creators to produce their content in response to international television series focusing on their relationship with the series, their followers, the official distribution platforms, and the platforms where their works are distributed. This will enable a better understanding of how, in the Chinese context, the categories of content operate in practice.

Finally, the paper argues that while some co-creators seek to draw attention to the series they support (a practice most likely to be demonstrated by fans) the engagement is not fully motivated by a desire to interact with international television series and direct audiences to it. Rather, co-creators are motivated by a desire to get visibility as influencers, to gain exposure to their own craft, or to develop transferable skills that help them move between the different categories of content creator. In doing so, we argue that international television series can tap into these ‘cultural intermediaries’ (Hutchinson Citation2017) to spread content, even if the ultimate desire of these co-creators is to utilise the text and its audiences to support their own skill development or visibility, rather than to raise awareness of the international television series.

2. Categories of content

2.1. Categories of content in the Anglophone literature: UGC and PGC

The characterisation of UGC as interpretative engagement is grounded in media and fan studies scholarship, which considers user created works to be evidence of the activity of viewers. Henry Jenkins’ definition of a participatory culture features a community of creators, whose ability to share content forms the basis of their connection with each other (Jenkins et al. Citation2005). Axel Bruns describes ‘produsage’ (Bruns Citation2008), as a process of collaborative creation in which individuals are both ‘users’ and ‘producers’ in a networked community, placing emphasis on activity as a characteristic of audiences in a networked media landscape.

A common feature in both Jenkins’ (2006) and Bruns (Citation2008) descriptions of UGC is the focus on non-professional production. As the terms suggest, UGC is comprised of content created by audience of media, generally considered amateur in nature (Kim Citation2012). Video hosting sites such as YouTube were initially designed to encourage UGC through easily managed uploading functions, shaping the format of UGC through imposing time limitations (initially of 10 minutes) (Burgess and Green Citation2009). The proliferation of social media saw the diversification of UGC with a close association between platform and content. Away from video hosting sites, UGC took the form of ‘tweets or Facebook pages, pictures (Pinterest), blogs, microblogs, and product reviews (Amazon, Yelp)’ (Liu et al. Citation2017, 237). Such UGC has been considered for its potential to influence brand image and purchasing intent (Liu et al. Citation2017), however, it is clearly demarcated from content produced with institutional support.

Professionally Generated Content (PGC) is defined as content created because of collaboration between the video hosting platforms and established media professionals or media groups (such as NBC in the United States) (Kim Citation2012). Content is alternatively purchased from a third party, or produced by the site, for the purposes of streaming on the video hosting site. The online series Origin, released on YouTube Premium, is an example of the video hosting platform’s foray into in-house PGC creation through collaboration with several smaller production companies (Jarvey Citation2017). PGC is thus characterised as content that shares many of the production values, formats (length and number of episodes), marketing and advertising structures of traditional television productions. Indeed, in a media environment where content broadcast on television is also streamed via online network-owned platforms (such as BBC iPlayer), the term PGC could equally apply to content commissioned by video hosting platforms as it does to terrestrial broadcasting networks.

2.2. Categories of content in the Chinese literature: UGC-PGC-OGC

A review of Chinese literature and media sources in which the term is used suggests that in the Chinese context, PGC is more broadly applied than in the Anglophone literature. Content produced by the platform is still considered within the category of PGC (Xu 2012), however content that is produced by individual media professionals or celebrities and independently uploaded is also considered to belong to this category (Tang and Chao 2017; Liao 2018). Content that is produced by individuals may seem to align with conventional understandings of UGC, however most sources in the Chinese literature agree quality to be the differentiating factor. Specifically, content that is of higher quality than UGC—’professionally’ produced—is considered within the PGC category (Huang 2016; Liu 2016). This differs from the previously discussed definitions around these categories in Anglophone literature, which views content that is created by professionals but supplied without receiving monetary returns as UGC (Kim Citation2012). PGC thus refers to any content that is made with a degree of professional skill and not only to commissioned work.

In addition to UGC and PGC, a review of the literature suggests a third term to be operational within the Chinese media landscape: occupationally generated content (OGC). Originating in 2014 in an online article, Liu (2014) proposes UGC and PGC to exist separately from OGC, defining it as content that is occupational and designed to generate revenue. Writing about journalism in China, Han and Han (Citation2015) later equate OGC with reports from traditional news agencies, suggesting OGC to be representative of media organisations. Li (2016) expresses a similar understanding of ‘occupational’, identifying intersections between PGC and OGC because of the multiple identities occupied by content creators. Content could be both PGC and OGC as creators ‘have both professional [zhuanye (专业)] and occupational [zhiye (职业)] identities […] such as news reporters and editors’ (Li 2016, 63). Li (2016) thus associates the skills of a content creator with ‘professionalism’, and their designated roles with ‘occupational’. If a creator represents their employer when creating content, it is deemed ‘occupational’ in nature. Likewise, Huang (2016) considers content created by official media platforms (such as Netflix) to fall within an OGC category, characterised by larger budgets and a position at the centre of distribution campaigns. This consideration of OGC aligns with conventional definitions of PGC in the Anglophone literature mentioned above. The difference between OGC and PGC is thus often vague and conflicting. Writing in 2017, He and Yu highlight the professionalism of PGC while suggesting OGC is less professional as the content is created by organisations who have not received professional training, and are less comprehensive (He and Yu 2017).

Given the fact that in the Chinese literature PGC refers to both the kind of content produced by the platform as well as any content produced by professionals in their role as co-creators, this paper explores how intrinsic (personal) and extrinsic (environmental) factors influence desire to create, and alignment with the different categories of content.

3. Method

Previous studies focused on the marketing strategies of distribution platforms featuring UK and US television series (Gilardi et al. Citation2018). The results of a pre-study online survey conducted with 477 participants indicated that Sherlock (82.39%, n = 393) and Game of Thrones (72.54%, n = 346) were the two most widely recognised international television series distributed via official online platforms (Youku: Sherlock, Tencent Video: Game of Thrones) (Gilardi et al. Citation2018). To further investigate the motivating factors of co-creators responding to international television series, the current study targeted co-creators who produced materials related to these two international television series. As the distribution of domestic series greatly outnumber international television series due to a quota on imported media (State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television 2015), only the most popular international series will attract the variety of co-creators necessary to explore the creator categories in practice.

Interviews were conducted with Weibo and Bilibili account holders who have relatively large followers (over 1000) and high viewing volume (over 10,000). Interviews enable researchers to develop an understanding of ‘personal accounts of behaviours, opinions and experiences’ (Hansen and Machin Citation2010, 45) through exploration of the unique experiences of individuals in any social setting. As a means of gathering information, it provides greater detail and the potential to ‘further explore any issues that arise’ (Hansen and Machin Citation2010, 46). The aim of this study is to understand nuances in practice that distinguish different content categories, and to identify motivating factors that may relate to a co-creator’s interpretation of media text and their relationship with these categories. It is therefore important to gain a deeper understanding of individual co-creator experiences, which is achieved through in-depth interviews that adopts purposeful sampling in order to provide the richness of data required to more fully understand the phenomenon (Lindlof and Taylor Citation2011). The study aims not to provide generalizable results, but adopts a ‘case-orientated’ (Sandelowski Citation1995) approach in order to allow unique accounts to emerge. To balance the need to provide a ‘new and richly textured understanding’ (Sandelowski Citation1995, 183) of the broader categories, and still retain the complexity of individual accounts, a sample size of 20 participants was set at the target.

A first round of 8 interviews were conducted; 5 participants were contacted through their Weibo account and a further 3 found by snowballing. To increase the chances of interviewing co-creators producing PGC and OGC, a second round of 6 interviews were conducted targeting account holders who posted videos related to Sherlock and Game of Thrones, which were promoted by the official distribution platforms of the series in China (Youku and Tencent Video respectively). A further round of interviews were conducted with the initial participants, and an additional 10 identified using the same criteria. In total 24 interviews were conducted with co-creators. An additional interviewee did not participate in a formal interview, but agreed for their initial statements to the authors to be included in the study. Interviews followed a semi-structured format to allow for themes to emerge around a general topic of interest. Co-creators were asked about their motivation to create content in response to international television series, their relationship with the media text, their followers, and their relationship with the official and ‘unofficial’ distribution platform. Interviewees were also given the opportunity to give examples and add anything they thought was important to define their profile. Interviews were carried out by research assistants in Chinese, transcribed, and translated into English.

Responses relating to the identity of interviewees were divided according to self-identification against the definitions of UGC, PGC and OGC established in the literature. Respondents were initially asked if they were familiar with the concepts of UCG, PGC, OGC, and then they were asked to self-identify themselves based on the definitions of UGC, PGC and OGC established in the literature.

Interview content was coded using a two-step process. Open coding was adopted to identify specific codes in the data and general categories of interest. As one of the research aims was to investigate the motivation for co-creators to create and upload content, concepts related to motivation were derived after the first round of open coding. A second round of coding was conducted based on the concepts identified in the first round and categories formed using axial coding; themes were then generated using selective coding.

Institutional ethics approval was obtained to conduct the research. Interviewees will be referred to according to assigned numbers to maintain anonymity.

4. Identity of co-creators

Literature identified three types of content considered to operate within the Chinese media industry: user generated content (UGC) produced by amateur creators, professionally generated content (PGC) produced by trained creators, and occupationally generated content (OGC) produced by employed (both trained and untrained) creators.

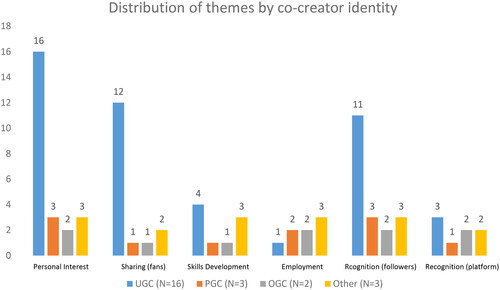

As noted in , 16 respondents self-identified as UGC creators; 3 as PGC creators and 2 as OGC creators. The 3 respondents demonstrating a desire to move between categories UGC toward PGC and PGC toward OGC are classified as ‘Other’.

Table 1. Identity of content creators.

The most widely recognised category is the UGC creator. This indicates that the category is both recognised in the literature and known by co-creators. While this is not surprising considering the wide use of the term in the press by virtue of its association with YouTube, it should be noted that interviewees 6, 7, and 13 self-identified as UGC creators but could be considered OGC or PGC creators. For instance, interviewee 13 self-identifies as a UGC creator despite being employed by a media company as an editor. Because they create Game of Thrones videos in their spare time, they consider themselves to be a UGC creator based on their relationship to the Game of Thrones content. As they do not profit from Game of Thrones related videos, they do not consider themselves to be professional or occupational content creators in respect to the imported television series, focusing more on their role as fan of the show.

Three interviewees self-identify as PGC creators. Others display tendencies that align with PGC creators (creating content used by media companies) but did not self-identify as such. Interviewee 6 produced work attracting interest from media companies and Interviewee 7 has sufficient follower numbers to receive attention from distribution platforms but both self-identified as UGC creator.

2 participants identify as OGC creators; few familiar with this category with some having not heard of it prior to the interview. Although unwilling to participate in the formal interview (and thus not in the overall count of 24), one interviewee noted: ‘Maybe other people call us OGC creators but we have no idea, we are just professional video makers’ (Additional Interviewee).

Other interviewees classified ‘Other’ inhabit in-between statuses. For instance, Interviewee 24 stated: ‘I think, I am between UGC and PGC, or in other words, a transition. I started to create videos out of interest, but […] later, I set up a channel to share some film editing skills and I am making some money along the way’.

In contrast to the definitions of UGC, PGC, and OGC in Anglophone and Chinese literature, interviews indicated that PGC was not a widely recognised category, even if descriptions of the content creators matched the profile in the Chinese literature. OGC creators were less likely to consider themselves under this category either because they were unfamiliar with the term and simply considered themselves to be professionals (Additional Interviewee), or because they are not employed to create the content they upload (Interviewee 2).

Co-creator identities are fluid based not only on their skill level and employment status, but their relationship to the content they upload. If the creation of content is an indication of levels of engagement with imported television series, it is important to further explore the motivations for co-creators to engage with the international television series, which is examined in the following section.

5. Motivating factors

Interview coding resulted in the following themes: Personal Interest (1); Sharing with fans (2); Skill Development (3); Employment (4); Recognition from followers (5); Recognition by platform (6).

Coding was performed separately by the two authors. Theme-agreement between the two coders was tested based on a sample of 14 interviews. Kappa Statistics was used with results indicating an 88/1% agreement between the two coders representing a significant concordance between the two with a moderately high Kappa of 0.761 (z = 6.98, p < 0.001). The frequency of themes identified by the coders was tested using paired t-tests, applied for each theme. Results indicated that there were no significant differences in the frequencies of theme identified between coders on all themes except ‘Personal Interest’ and ‘employment’ with coder 1 identifying a lower frequency than coder 2. Overall results are summarised in .

Table 2. Frequencies of theme identified by coders (N = 14).

Co-creators exhibit different motivations associated with their self-identified category, their relationship to the official media text, and their relationship to their followers and the platform. Of the 24 interviewees, ‘Personal Interest’, ‘Sharing’ and ‘Recognition from followers’ were most frequently associated with the 16 UGC creators; ‘Personal Interest’ and ‘Recognition from followers’ with the 3 PGC creators. All themes were associated with OGC creators. ‘Personal Interest’, ‘Skill Development’, ‘Employment’, and ‘Recognition from followers’ were most frequently associated with the 3 interviewees categorised as ‘Other’. Results are presented in .

5.1. UGC as fans

Most interviewees who self-identified with UGC define themselves as fans producing content out of love (用爱发电), to raise awareness about the series, and to meet people with similar interests. Thereafter, they are motivated to create content based on personal interest such as creating new narratives (Interviewees 16, 21) around pairing relationships (Interviewee 1), or to produce translations of material only available in the original language (Interviewee 4).

Co-creators in this category dedicate a high level of attention to their followers, but there is no evidence of specific strategies to increase their followers’ number. Interviewee 7 states:

The number of followers doesn’t matter to us, thought hitting key figures such as 100K does make us happy. But we are not worried when growth rate comes down. After all, what we care about most is whether we could be helpful for others.

Co-creators interact with followers who comment on their work by commenting back (Interviewee 1), fielding requests for specific interpretations or summaries of the television series (Interviewee 10), or providing a space for fans of the text to interact: ‘I know that if people watch the show by themselves, they might feel alone. So, I’m offering this platform where they can come and discuss’ (Interviewee 6). For this participant, their position as facilitators of interaction soon became the motivating factor to continue creating and uploading content. This enables them to maintain a position of authority within their relative subcultural networks.

The platform itself does not seem to be a motivating factor for these co-creators, as Interviewee 16 expresses: ‘There are some regular campaigns on Bilibili [to get income for videos], but I seldom participate in them’. Interviewee 6 notes creative freedom to be a key factor for their reluctance:

a lot of those companies approached me and ask if I wanted to sign a deal and become a content producer with contract… I rejected them, because I thought that way my words and voices would be out of my own control. So, I’m still doing this on my own.

5.2. PGC

While all 3 respondents in this category started producing videos out of their personal interest, they all demonstrate a clear motivation to connect with their followers through online and offline activities. Interviewee 17 reported inviting fans for online lucky draws and meeting the winners offline. Interviewee 15 manages five WeChat groups and four QQ groups to connect with their audiences in addition to an offline party organised by their own company.

These co-creators engage with different platforms and have a good understanding of the platform’s business models. Interviewee 17 stated that they use Weibo, Bilibili, Youku, iQiyi, Tencent Video, TikTok, Ixigua and Baidu to upload their videos but ‘iQiyi, Tencent Video, and Youku now are gradually changing and are more oriented toward copyrighted content and business models based on charging viewers’. This is also highlighted is academic literature (Gu Citation2018; Gilardi et al. Citation2022).

Co-creators in this category align with definitions in the Chinese literature as content produced is purchased or rewarded by video hosting platforms or produced in collaboration with them. Two out of three interviewees that self-identified as PGC own small production companies and produce professional content from which they profit by generating data traffic or selling content to third parties. Interviewee 23’s content is purchased by third parties, while interviewee 15 collaborated with Tencent Video when the final season of Game of Thrones was launched.

Of particular interest is the fact that two of the interviewees mention the idea of we-media/self-media. Interviewee 15 adopts the term when referring to their own work as they appear in the videos. Interviewee 17 likewise emphasises the centralisation of the persona of the content creator, suggesting that we-media/self-media displaced PGC as a concept: ‘over the past year few years, the concept of ‘self-media’ has become prevalent, which weakened the concept of PGC’. They further distinguish between categories of self-made media content based on influence: ‘Because many UGC entered the we-media/self-media arena, the notion of wanghong started to emerge. In my opinion, with the exception of top wanghong, all others should be called self-media’.

Scholars note the diverse and polysemic nature of the term wanghong (网红), variously used to describe opinion leaders and influences, and zhubo(主播)(online streaming hosts) (Craig et al. Citation2021), and used pejoratively to dismiss online content creators as ‘frivolous, silly, bizarre, vulgar, morally questionable, or socially menacing’ (Zhao Citation2021, 211). At the same time, they note the specific conditions of Chinese Internet and rising cultures of entrepreneurship which lead to the current manifestation of the wanghong and wanghong industry. Xiaofei Han (Citation2021) notes:

In the late 1990s and 2000s, use of term wanghong still largely overlapped with “internet celebrities” and the patterns and/or value chains for monetising such online fame—which is arguably one of the defining characteristics of contemporary wanghong since the mid-2010s—were yet to emerge. The meaning of the term “wanghong” changed significantly between 2015 and 2016 due to the construction of “wanghong economy”…. (p. 2)

5.3. OGC

Out of three types of co-creators identified with OGC, the first type includes individuals who are, or aspire to become, online personalities. As mentioned, personalities emerging from the wanghong economy are classified as such (wanghongs), with comparatively less industrialised we-media/self-media producing other forms of online personalities. Regardless of the degree of industralisation, these individuals operate social media accounts that attract large followers with the capacity (or potential) to generate substantial financial capital. They adopt self-branding strategies akin to the branding of celebrity figures, as well as foster relationships with follower-fans that echo other forms of fan-celebrity interactions. As such they are theorised by Theresa Senft (Citation2008) as ‘micro-celebrities’. Several potential OGC creators were identified based on their strategic use of Weibo and WeChat, and their management of public accounts. However, despite explanations as to the nature of the study and an interest in exploring motivations for engaging with imported television series, most of them declined requests for interviews. An exception is Interviewee 14, an aspirational self-media producer who has collaborated with distribution platforms such as Tencent. This co-creator produces videos about the imported television series Game of Thrones. However, unlike the remix or summary videos of UGC creators, Interviewee 14 presents on-camera reviews of the show. While the content discussed in the videos results in the sharing of information and options about the imported series, the overall aim of producing the videos is to cultivate and enhance their own online persona. Interviewee 14 is therefore aware of, and concerned with, maintaining a relationship with their followers:

My job content is mainly recording and editing videos to introduce the books, films and TV series that I like to the audience. My main motivation is my own interest, and also fans. What is most important is that I have confidence in my ability and my competitiveness in this work.

The second type of co-creators identified as OGC creators is represented by educated and trained professional video makers, working directly for the online video distribution platform or for a multi-channel network (MCN) and as already stated above, do not necessarily recognise themselves as OGC creators but simply as professionals in their area. This indicates that, despite distinctions between professional (based on skills and training) and occupational (based on place of employment) in the literature, in practice these nuances may not apply.

The last type includes people that become OGC creators by ‘moving up’ through different categories from UGC to OGC. While a company may not currently employ them, they were employed at some point (Interview 22) and they share most characteristics with co-creators in the ‘Other’ category.

5.4. Other: between UGC, PGC and OGC

Co-creators classified as ‘Other’ inhabit in-between statuses either having shifted between UGC and PGC with aspirations towards OGC (Interviewee 2), or indicating a desire to transition from UGC to PGC (Interviewee 3, 24).

Like the UGC, PGC and OGC, co-creators in the ‘Other’ category initiated their video production because of a personal interest in the imported television series, and a desire to share this with a fan community. Interviewee 3 was motivated initially to share with individuals they knew and later expanding when their work was recognised by other online users: ‘At the beginning, it was for sharing with friends [then] I found that there were other people watching [those videos], saying ‘could you translate them a bit’, so I began to make subtitles’. These initial motivations are initially driven by a desire to respond to the text in an interpretative way (Ahva and Hellman Citation2015). However, while the interviewees note sharing with fans or friends to be a prevalent activity, it is a secondary motivation. The sharing of content is a consequence of the online exposure that their videos received, rather than being the aim of the co-creator. The content ultimately reflects an expression of the co-creators’ reaction to the text. They were motivated by a desire to respond to their followers due to their affection for the text or its stars. The text becomes a conduit for interactions with other fans of the same text.

The difference between sharing with fans and recognition from followers is situated in the creator’s intentions for the content. While the majority acknowledge that they receive follower attention, or are aware of metric indications of attention (view rates), it is not of primary concern. As Interviewee 3 notes, it is the nature of the interaction with their followers which they deem most important: ‘What’s more interesting is shooting comments, which can show me [follower] reactions at the point where I’ve made good translations. Such reactions can be huge, which makes me feel acknowledged and very, very proud’. Additionally, a large following is viewed as restrictive when the co-creator wishes to diversify: ‘I feel that there is a huge audience segmentation in my fans, around the topics of GoT, snowboarding, cats and a little bit of cuisine, so the development is a bit restricted’.

This contrasts with Interviewee 2, who aspires to become PGC or OGC creator, and cites follower recognition and preference as guiding factors that shape their content: ‘A Scissorhands [editor] for sure want to be watched by a mass amount of people. So now I also put more consideration in the process of editing as well as the releasing time’. As follower recognition is closely associated with their own self-development, this interviewee is concerned with building a reputation as a ‘Scissorhands’ and a content creator in their own right. Once a following is secured, the interviewee turns their attention to maintaining a standard of production: ‘I think I should focus on the quality of my videos rather than how many people are following me’.

The motivations for this co-creator shifted as their profile and profession changed, Interviewee 2 explaining:

[at] the beginning it was just because I liked [the series], but later, I discovered that some people went to watch the TV series after watching my clip. I was very happy about that. I might be one of the very few people who developed their hobby into a career. I’m currently doing a formal job as a video editor in the game industry. I like video editing, and I’m happy to keep doing it.

Interviewee 2 is an interesting case that shows how motivation changes in parallel with the move from one category to the next. At some point between their UGC and OGC status, their relationship to the text, their followers, and the platform became a utilitarian one supporting the improvement of their skills:

the shooting comment on bilibili is useful, because I can get audience reactions specific to every second in my videos, it’s very straightforward. If there’s any drawbacks, for instance the colour and audio in some part of the video is lame, shooting comments will point it out so I can improve next time.

This contrasts with the UGC fan creator whose primary focus is to service the text and participate in the fan community. illustrates these differences.

Table 3. UGC, PGC, and OGC differences in terms of motivation to interact with media text, followers, and platforms.

6. Conclusion

This study explores co-creator (Gilardi et al. Citation2018) engagement with international television series and examines whether their motivation as co-creators is influenced by their relationship with the text, interaction with followers and platforms. At the same time, the article clarifies how, in the Chinese context, the definitions in the literature of content work in practice, as illustrated in .

Table 4. Definition of content in Anglophone and Chinese literature and by this study.

Findings indicate that the identity of the co-creator does impact on their motivation for content creation. For instance, as fans, UGC creators were motivated to draw attention to the television series. Fans often play a pioneering role in the introduction of media content across cultural and national boundaries by raising awareness of content through their practices of content (re)creation (Jenkins et al. Citation2013). Fans play a central role in amassing sufficient demand for content that can, in some instances, facilitate official distribution. This is exemplified by the release of the third season of Sherlock in China, where audience demand, supported by a strong fan base, resulted in the almost simultaneous release of episodes on the BBC and Youku (Blum Citation2014).

Others co-creators, mostly self-identified as PGC and OGC creators, were motivated to further establish skills they possessed and build their own audience base. Although these co-creators produce work to develop their profiles, they (like fans) are nonetheless vital ‘cultural intermediaries’ (Hutchinson Citation2017) who build reputation and followers based on the subgenre of media content that they share online in response to international television series.

The findings also suggest that while the notions of UGC are widely recognised by all interviewees, PGC and OGC were less known identity profiles, indicating that they are not prevalent categories in the Chinese media context.

Further research will benefit from closer exploration of co-creators’ self-definition to more precisely explicate their relationship to the texts, audiences, and platforms. Indeed, the terms we-media/self-media and wanghong more accurately articulated the nuanced relationship between co-creator, industrial context, and relationship with followers, with wanghong associated with high levels of visibility and recognition. The further exploration of how co-creators integrate engagement with media texts into the cultivation of the online personalities will help to understand additional reasons behind their interest in remaking international cultural products for Chinese viewers.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Yuda FENG, Jian MA, Shuxin CHENG, and Yifan ZHAO who worked as research assistants in this project.]

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahva, L., and M. Hellman. 2015. “Citizen Eyewitness Images and Audience Engagement in Crisis Coverage.” International Communication Gazette 77 (7): 668–681. doi:10.1177/1748048515601559.

- Bruns, A. 2008. Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and beyond: From Production to Produsage. New York: Peter Lang.

- Burgess, J., and J. Green. 2009. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Busse, K. 2017. Framing Fan Fiction: Literary and Social Practices in Fan Fiction Communities. Iowa: University of Iowa Press.

- Blum, J. 2014. “Chinese Fans First to See New “Sherlock” Season Outside Britain.” South China Morning Post, January 2. https://www.scmp.com/news/china-insider/article/1396067/mainlanders-first-see-new-sherlock-season-outside-britain

- Craig, D., J. Lin, and S. Cunningham. 2021. Wanghong as Social Media Entertainment in China. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fiske, J. 1987. Television Culture. London: Methuen.

- Gilardi, F., C. Lam, K. C. Tan, A. White, S. Cheng, and Y. Zhao. 2018. “International TV Series Distribution on Chinese Digital Platforms: Marketing Strategies and Audience Engagement.” Global Media and China 3 (3): 213–230. doi:10.1177/2059436418806406.

- Gilardi, F., A. White, Z. T. Chen, S. Cheng, W. Song, and Y. Zhao. 2022. “From Copycat to Copyright: Intellectual Property Amendments and the Development of Chinese Online Video Industries.” International Journal of Cultural Policy: 1–17. doi:10.1080/10286632.2022.2040494.

- Gu, J. 2018. “From Divergence to Convergence: Institutionalization of Copyright and the Decline of Online Video Piracy in China.” International Communication Gazette 80 (1): 60–86. doi:10.1177/1748048517742785.

- Han, L. 韩立新, and H. Han. 韩惠迪 2015. “Cong Mahang MH370 Shijian Kan Xinwen Zhuanye de Xiquexing从马航MH370事件看新闻专业的稀缺性 [Looking into the Scarcity of Professionalism in News through the Case of MH370].” 中国报业 (China Press) 2015 (10): 11–13. https://www.cnki.net/kcms/doi/10.13854/j.cnki.cni.2015.10.003.html.

- Han, X. 2021. “Historicising Wanghong Economy: Connecting Platforms through Wanghong and Wanghong Incubators.” Celebrity Studies 12 (2): 317–325. doi:10.1080/19392397.2020.1737196.

- Hansen, A., and D. Machin. 2010. Media and Communication Research Methods. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- He, L., 贺岭, and C. Yu 于程媛. 2017. “Jiyu UGC he OGC Chuanbo Fanshi Xiade Xinxi Suipianhua Xianxiang Yanjiu 基于UGC和OGC传播范式下的信息碎片化现象研究 [Research on the Fragmentation of Information Based on the UGC and PGC Paradigm].” 出版广角 (Views on Publishing) 2017 (14): 72–74. http://lib.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7000252435.

- Huang, S. 黄绍麟. 2016. “PGC/UGC/OGC, Shipin Hangye Gdian Hezai? PGC/UGC/OGC, 视频行业G点何在? [PGC/UGC/OGC, What Is the Key Point of Video Industry?].” 36kr, September 29. https://36kr.com/p/5053742.html

- Hutchinson, J. 2017. Cultural Intermediaries: Audience Participation in Media Organisations. Cham: Palgrave.

- Ito, M. 2012. “Contributors versus Leechers: Fansubbing Ethics and a Hybrid Public Culture.” In Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World, edited by M. Ito, D. Okabe, and I. Tsuji, pp. 179–204. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Jarvey, N. 2017. “YouTube Red Orders Sci-Fi Drama from ‘The Crown’ Producers.” The Hollywood Reporter. October 25. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/youtube-red-orders-sci-fi-drama-crown-producers-1051631/

- Jenkins, H. 1992. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge.

- Jenkins, H. 2006. Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: NYU Press.

- Jenkins, H., S. Ford, and J. Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: NYU Press.

- Jenkins, H., R. Puroshotma, K. Clinton, M. Weigel, and A. J. Robison. 2005. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. The Mac Arthur Foundation. http://www.newmedialiteracies.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/NMLWhitePaper.pdf

- Kim, J. 2012. “The Institutionalization of YouTube: From User-Generated Content to Professionally Generated Content.” Media, Culture & Society 34 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1177/0163443711427199.

- Li, B. 李彪. 2016. Chuantong Meiti Ronghe Chuangzao Jingzhengli Zaizao Lujing Yanjiu 传统媒体融合创新竞争力再造路径研究 [Research on Reengineering Path of Traditional Media’s Integrating Creative Competiveness]. 新闻战线 (The Press) , 2016 (21), 65–69. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-XWZX201621018.htm

- Liao, P. 廖佩伊. 2018. “UGC, PGC de Shejiao Meiti Neirong Shengchan Fangshi Bijiao UGC, PGC 的社交媒体内容生产方式比较 [A Comparison of the Production Approach of Social Media Content of UGC and PGC].” 新闻研究导刊 (Journal of News Research) 2018 (16): 104. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-XWDK201816058.htm.

- Lindlof, T. R., and B. C. Taylor. 2011. Qualitative Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Liu, M. 刘铭哲. 2016. “UGC Sawang PGC Zuoda Shipin Zhibo Pingtai Neirong Zhuangzuoquan Jiedu UGC撒网PGC做大 视频直播平台内容创作圈解读 [Expanding Business Model through PGC from the Pool of UGC: A Reading of Live Broadcasting Creation Circle].” 数码影像时代 (Digital Video Times) (6): 26–29. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-SMYX201606008.htm.

- Liu, X., A. C. Burns, and Y. Hou. 2017. “An Investigation of Brand-Related User-Generated-Content on Twitter.” Journal of Advertising 46 (2): 236–247. doi:10.1080/00913367.2017.1297273.

- Liu, Z. 刘振兴. 2014. Qianxi UGC, PGC he OGC 浅析UGC, PGC和OGC [A brief analysis of UGC, PGC and OGC]. 人民网 (People.cn). January 2. http://yjy.people.com.cn/n/2014/0120/c245079-24169402.html

- Sandelowski, M. J. 1995. “Sample Size in Qualitative Research.” Research in Nursing & Health 18 (2): 179–183. doi:10.1002/nur.4770180211.

- Senft, T. M. 2008. Camgirls: Celebrity and Community in the Age of Social Networks. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television 国家新闻出版广播电影电视总局. 2015. “Guojia Xinwen Chuban Guangdian Zongbu Bangong 《Guanyu Kaizhan Wangshang Jingwai Yingshiju Xiangguan Xinxi Shenbao Dengji Gongzuo de Tongzhi》国家新闻出版广电总局办公《关于开展网上境外影视剧相关信息申报登记工作的通知》” [Notice on Launching The Registration Process for Overseas TV Series Online]. http://www.chncia.org/2015/0122/3818.html

- Tang, Z., 唐忠会, and Y. Chao巢宇. 2017. “UGC Shengjiwei PGC: Ronghe Taishixia Shipin Wangzhan Xinbianju UGC升级为PGC:融合态势下视频网站新变局 [Upgrading UGC to PGC: A New Prospect of Video Websites under the Trend of Convergence].” 节目风向 (Program Trend) 2017 (1): 103–106. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-STJZ201701039.htm.

- Toffler, A. 1980. The Third Wave. New York: William Morrow.

- Xu, F. 徐帆. 2012. Cong UGC dao PGC: Zhongguo Shipin Wangzhan Neirong Shengchande Zoushi Fenxi 从UGC到PGC:中国视频网站内容生产的走势分析 [From UGC to PGC: An Analysis of Chinese Video Websites’Content Production Trend]. 中国广告 (China Advertising), (2), 55–57. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-GGGG201202024.htm

- Zhao, E. J. 2021. “Wanghong: Liminal Chinese Creative Labor.” In Creator Culture: An Introduction to Global Social Media Entertainment, edited by S. Cunningham and D. Craig, 211–231. New York : New York University Press.