Abstract

This article analyses the role that Reality TV can play in the lives of young participants, when a programme is designed as a strategic intervention to achieve change. With roots in Communication for Development notions, this study brings together different theoretical fields to illustrate how media can be created with the intent of enhancing young people’s awareness of the important role they can play in society through targeted activities that occur during media production. The experience of the young contestants from The President TV show, broadcast in the Palestinian Territories in 2013 and 2015, is examined. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with some of the finalists of the show; information gathered has been analysed in the light of a framework that brings together media participation and civic engagement. Findings show how the format and structure of the programme has enhanced participants’ understanding of the social, political and economic spheres of a conflict-affected reality, contributing to their engagement with peace-oriented civic practices long after the end of the show.

Introduction

This article analyses the role that Reality TV can play in the lives of participants, when a programme is designed as a strategic intervention to achieve change. With roots in Communication for Development notions, this study brings together different theoretical fields to illustrate how media can be created with the intent of enhancing individuals’ awareness of the important role they can play in society through targeted activities that occur during media production. In particular, the experience of the young contestants from the The President TV show, broadcast in the Palestinian Territories, is examined.

The article begins with an overview of the situation of young people in Palestine: their views on the society they live in, their interest in the political environment, and their media consumption. A discussion on the literature follows. This begins by introducing the work of scholars on the topic of civic engagement through media — the concept of civic engagement is also discussed, and a definition provided. It goes on to outline the main views that arise from the literature on Reality TV and the evolution of the format; a connection is then made with the concept of Communication for Development by reviewing some of the studies that have looked at the use of Reality television for the purpose of community development.

The ensuing section provides detailed background on The President TV show and its targeted design. It also clarifies the objectives of this study, its methodology, and the gap it wants to fill. The framework of analysis is then put forward, along with its rationale and application. This paves the way to the presentation of findings, which exemplify the link between media participation and civic engagement. A concluding discussion brings together the key points arising from this study in light of the adopted framework.

The youth in Palestine

Defined as the age group between 18 and 29 years, the youth represent 22 per cent of the Palestinian society (PCBS. Citation2021). Yet, participation in political and public policy-making process among Palestinian youth is limited. In a survey conducted by Sharek Youth Forum (Fasheh Citation2013), 73 per cent of the youth stated that they did not affiliate with any political faction, and 20 per cent of them believed that political parties did not represent their interests and viewpoints. A study from Interpeace (Citation2017) showed that over 70 per cent of young people feel that their future is not safe, with 21.9 per cent of these indicating as primary concern the lack of security. The study found that the main four concerns for young Palestinians are:

Fear of the Occupation

Fear of blockade, division, and constant security threats

Fear of marginalisation and exclusion

Fear of the future.

With the idea of future regarded more as a threat than an aspiration, young people feel anxious and unmotivated; they associate darkness with the idea of future, and lack optimism and hope (Interpeace Citation2017). Palestinian youth are also crippled by a context that restricts their political participation. The majority of the Palestinian youth are preoccupied with the national struggle movement. They are targeted by the Israeli occupying authorities through methods that include detention and collective punishment. In addition to movement and access restrictions, Palestinian youth are subjected to travel bans, effectively debilitating their capacity of various forms of self-development (Dusouqi, n.d.).

Due to the structure of Palestinian society, no young person is excluded from the cycle of violence. Having lost everything, young people see themselves as the main victims of the violence of Occupation and feel compelled to direct their energies towards liberation. At the same time, they see themselves as agents in the process of nation-building and able to contribute to change. Yet, they feel excluded from decision-making and face challenges in relation to implementing solutions, as permission to carry out their proposed activities is often denied: ‘youth perceive this as a restriction to their capacity that evidently leads to youth marginalisation and reduced participation in decision-making processes’ (Interpeace Citation2017, 25).

Another study shows how young Palestinians have little trust in their governments, with only 27 per cent of respondents expressing confidence in the institutions. Less than 10 per cent has confidence in political parties, and only 12 per cent in the parliament. Positive and change-driven activism can be created by a lack of trust in institutions; yet, a significant absence of trust is mostly detrimental (Christophersen Citation2016).

A major challenge associated with the Palestinian political system includes the non-renewal of Palestinian political élite. This impedes an enhanced Palestinian youth participation in public policy-making and political decision-making activities. Change and turnover of the Palestinian political élite is usually a result of natural causes, including death or illness. This is a typical feature of Palestinian political parties and political institutions, including the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). In relation to political parties, the average age of members on the Fatah Central Committee is 60 years, and on the Hamas Political Office 50 years (Dusouqi, n.d.). To this day, Palestine has not had a national election in almost 20 years, and the 2005 elected Palestinian Authority is outside the terms of the legal constitution.

Moreover, young people have realized that no uprising or peace process that former generations have engaged with have actually brought any meaningful change: this makes them feel powerless and cynical towards traditional political participation (Christophersen Citation2016). In response to that, a number of attempts have been made to increase young Palestinians’ participation in politics and public policy:

Palestinian civil society organisations (CSOs) | Relevant literature shows that this alternative has not promoted youth participation in the public policy-making process (Sana Citation2009).

Youth local councils | To enable youth political participation and engagement in the decision-making process, some youth organisations have created simulation models of local councils. However, this experience has not been so fruitful. Efforts made by the Sharek Youth Forum have not been successful to promote youth political participation in decision-making circles (Dusouqi, n.d.).

The Youth Movement | Given that political parties and CSOs have been incapable of meeting the youth’s aspirations to political participation, Palestinian youth have created a new, more attractive channel to express themselves, articulate their social and political opinions and perceptions, and actuate their desire for change. However, participation in this movement has been mediocre (AWRAD. Citation2013).

In light of this situation, new avenues must be found to promote active participation of young Palestinians in society, and encourage the development of civic responsibility and sense of agency towards one’s own community. Media can be an avenue not only for information transmission, but also for participation and co-creation. In Palestine, for example, media consumption is solid, with 59 per cent of people watching television regularly, 41 per cent listening to radio, and 30 per cent reading a newspaper. A study from Internews (Citation2007) also captured that, differently from other groups, young people’s preference for media programmes is centred around entertainment. Youths tend to prefer this format also over programmes that deal with local and social issues. This highlights the significance of the role that media entertainment can play in engaging young Palestinians at a civic level. In the political context of Palestine, civic engagement cannot be regarded as separate from building and preserving peace.

Civic engagement and Reality TV

Several scholars, particularly in the field of developmental psychology, have tried to understand how and when civic engagement begins to play a role in the lives of young people (see Lance Bennett, Wells, and Freelon Citation2011; Lerner et al. Citation2014; Loader, Vromen, and Xenos Citation2014; Miranti and Evans Citation2019; Wray-Lake, Metzger, and Syvertsen Citation2017). Yet, throughout the literature, the concept of civic engagement itself has been defined differently.

Amnå (Citation2012) maintains that, too often, developmental scientists have broadly looked at the acquisition of civic engagement as the process of ‘evolving humanistic values, learning, training social talents, self-expression, and the adaption of social norms and expectations’ (616). Adler and Goggin (Citation2005) have attempted to narrow down its definition by stating that ‘civic engagement describes how an active citizen participates in the life of a community in order to improve conditions for others or to help shape the community’s future’ (241). In a BBC Media Action report discussing civic participation through social media in the Palestinian Territories and Bangladesh, Bokai et al. (Citation2013) provide a similar definition (based on the British Broadcasting Corporation glossary):

‘Civic participation includes a range of activities that can be social in nature and/or political or designed to influence policy making and decision making (this constitutes political participation, a component of civic engagement). Civic engagement includes being active on local community issues, volunteering, mentoring, getting involved in human rights activities and youth leadership’ (10).

In other words, besides the mere involvement in activities of a political nature, civic engagement encompasses a broader spectrum of initiatives whose aim is that of benefitting the community at large, or more disadvantaged groups within it. As Lerner et al. (Citation2014) explain on the concept of civic engagement, while the behaviour of someone who is protesting against injustice may not bring immediate benefit to the institutions that are upholding that injustice, it can be extremely helpful to those who are being affected; it may even carry historical benefits through the adoption of a new policy or other types of change, which can lead to a transformation in society.

There are different approaches in which the media can lead the way for individuals to take this change-driven path. Scholars have also looked, specifically, at what these approaches may involve: many have examined the connection between civic engagement and social media (de Zúñiga, Jung, and Valenzuela Citation2012; de Zúñiga, Copeland, and Bimber Citation2014; Sloam Citation2014; Warren, Sulaiman, and Ismawati Jaafar Citation2014; Mainsah, Brandtzaeg, and Følstad Citation2016); Rogers et al. (Citation2014) have looked at the use of writing, visual arts, film and theatre; Smith (Citation2017) has investigated the use of participatory photography; Farnham et al. (Citation2012) have analysed the use of blogging as citizen journalism; Lee, Shah, and McLeod (Citation2013) have attempted to look at different communication pathways. What is being explored, in the context of this article, is the use of Reality TV. In particular, we want to understand how this format can motivate young people who participate in a Reality television show to engage in civic life beyond the opportunities provided during the programme.

Chan and Jekinson (Citation2017) define Reality TV as ‘a genre of television programming that documents purportedly real life situation often starring unknown individuals rather than professional actors’ (9). The authors go on to explain that its content is often a mix of information and entertainment, and is designed for viewers to relate to it and increase their voyeuristic tendencies. What viewers receive, ultimately, is entertainment. At the same time, Niedzwiecki and Morris (Citation2017) put forward that ‘[R]eality television shows are a ripe area for the development of parasocial relationships between viewers and show characters’ (n/a). This indicates that show’s participants can play a critical part in role modelling.

Kavka (Citation2021) divides the genre into three generations. The first one saw ordinary people being observed in the settings they were found (such as, for example, Candid Camera). Going a step further, the second generation added artifice to actuality, developing its own format rules and production practices. Environments are fabricated and participants are subjected to full-scale scrutiny; this is exemplified by Big Brother. What is characteristic of this generation is that, even though the environment is fictitious, ‘TV settings simulate the lived landscapes and social reality’ (Kavka Citation2021, 76), blurring the line between real and fictional, private and public, authentic and performed. From the year 2000 onwards, and in the midst of the shift to the celebrity-based third generation of the format, according to Kavka (Citation2021), Reality TV comes of age by not only representing but also intervening in people’s lives, offering an opportunity for self-realisation through challenge. The challenge becomes the centre point of the show, and the reward that comes with overcoming this is not simply the cash prize, but also a personal transformation that reflects a set of social values (Kavka Citation2021).

With the growth in popularity of this format, Reality TV programmes have also been designed for the purpose of social and community development. Amongst several others, studies on these include the work of Burger (Citation2012) on Zola 7 in South Africa, which analyses the contribution made by the programme to the public sphere by providing a platform for community members to air their problems publicly and finding solutions; the work of Ramafoko, Andersson, and Weiner (Citation2012) on Kwanda in South Africa, which evaluates the positive impact of the show on five disadvantaged communities that had to organize themselves to address health and development issues that affected them; the work of Ekström and Helgesson Sekei (Citation2014) on Ruka Juu in Tanzania, which analyses the process used in this reality TV entrepreneurship competition; and the work of BBC Media Action (Citation2015) on Amrai Pari in Bangladesh, which looked at how communities worked together to be prepared against environmental hazards as a result of the influence of the show.

Wilkins (Citation1996) highlights that when media are created as part of a programme that is aiming at altering social conditions, this can be regarded as Communication for Development (C4D). It is not uncommon for entertainment television programmes to have an impact on behavior and relationships. Yet, what differentiates C4D from these programmes is the strategic intention of the creators to achieve a defined social benefit through a mediated product.

A number of scholars (Paluck Citation2012; Tufte Citation2012; Skuse and Gillespie Citation2011; Skuse Citation2017; Baú Citation2019) have also emphasized how entertainment education, which is typically adopted in C4D interventions and may involve the use of formats such as Reality TV, can contribute to the creation of communication environments that are apt at preventing violence. Baú (Citation2015) has discussed how the use of different media productions can contribute to peacebuilding, particularly through the adoption of a C4D lens in their design. She has also maintained that engaging people in peacebuilding through the use of C4D enables a bottom up reconstruction process that can lead to a more sustainable peace. This can occur through participatory forms of governance facilitated by the media, which incorporate a more democratic approach and allow citizens to claim their rights (Baú Citation2016).

Ramafoko, Andersson, and Weiner (Citation2012) also invoke C4D when highlighting the effect that involving ordinary people tasked with changing their own communities in the production of a TV show allows individuals to shape the message, rather than simply being passive subjects. The authors also emphasize how this approach enables communities to set their own agenda for development by facing new challenges, ‘bring(ing) about change that is more civic driven, and therefore more likely to be lasting’ (151).

With roots into this literature, this study wants to expand both practical and theoretical knowledge on the connection between media and civic engagement, with specific focus on the youth in the Palestinian context. The application of a C4D perspective into this work is helpful in considering the effects that this connection may have on peace and development for communities.

Background to the study and methodology

Search for Common Ground (Search) is an international non-governmental organisation that works specifically in the area of Media and Communication for Peacebuilding. The organisation has been active in the Palestinian Territories since 2000, when it began implementing programmes to address issues related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; it has been working specifically on community resilience and democratic practices with the youth, to contrast their potential involvement in violence and terrorist-related activities.

In response to the social and political context outlined previously, Search recognized the importance of promoting civic engagement among the youth in order to prevent young people feeling hopeless about their future, decrease the incidence of violent conflict, and nurture a sense of political participation and community responsibility. To these aims, the organisation launched The President, a Palestinian reality TV show based around a mock presidential election, which provided the youth with a platform to directly engage with government leaders on a weekly basis. This was done in partnership with Ma’an Palestinian News Agency, which runs a network of local TV stations throughout the Palestinian territories. The goal of the programme was to create a new generation of Palestinian leaders and develop a political culture of peaceful civic activism and inclusive democratic practices, with the aim of increasing knowledge of and support for democratic political processes.

Both in 2013 and 2015, The President saw approximately 1,200 candidates aged 25-35 from the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel auditioning to compete in an elimination-style series of trials designed to test their political skills. The process required them to answer hard-hitting questions on live TV on various political, social, and economic issues affecting Palestinians, exhibiting sufficient self-discipline to be constantly ‘on-call’ during the campaign trail, and maintaining calm in an intense, televised political debate. Throughout broadcasting, candidates were evaluated by a panel of celebrity judges. Audience members voted via SMS at the end of each episode, eliminating the least popular candidate. In the finale, the remaining contestants participated in a live TV debate after which the winner was finally chosen. The President became a popular TV show locally, with coverage on platforms such as the Times of Israel and Haaretz, and it also gained widespread international media attention (including the BBC, The Telegraph, The Sydney Morning Herald and The New York Times, amongst others).

In each series, the last ten contestants that were left to compete in the programme after the progressive elimination of the other candidates took on the role of Mayor in a selected municipality. Municipal government officials acted as mentors for the candidates, providing them with hands-on training and coaching. Under this mentorship, the contestants were responsible for designing a ‘town hall-style’ dialogue in the community to assess and address needs, with a particular focus on topics relevant for women and/or youth. They were also responsible for discussions and a Q&A session, responding publicly to Palestinians’ questions and issues. The judges evaluated the efficacy of each campaign and graded the candidates.

SMS voting took place following the broadcast of this and subsequent episodes, after which two contestants were eliminated progressively: eight remaining candidates took control of a major Palestinian private company for one day each, in order to showcase their leadership, entrepreneurial and teamwork abilities — the show worked with private business partners to select existing business leaders who conducted a CEO management training with the participants; each of the subsequent six remaining candidates worked in a different Palestinian Authority ministry for a week — candidates learned how to address the nation using presidential etiquette and salutations, and how the President interacts with international leaders, advisors, ministers, and constituents; the last four candidates were responsible for representing the Palestinian Authority as The President — each candidate worked closely with a government official, who acted as a mentor and assisted them as they developed a sustainable, strategic national plan for the Palestinian democratic government; the last two candidates launched a full-scale presidential campaign in the Palestinian territories, including community outreach and public debates. In the final live episode, the judges interviewed candidates on their campaign techniques, promises to ‘constituents’, and national strategic plans, before the final winner was announced.

A preliminary quantitative evaluation conducted in 2016 shortly after the second series of the programme had come to an end reported the following findings (Alpha Citation2016):

900 young people pre-registered to take part in the selection process for the show

1.2 million people watched the show

94 per cent of the viewers (from the sampled population) believed that the themes and activities from the show were relevant to their daily lives

2.6 per cent increase in the knowledge of civic and democratic processes among the viewers.

What remains missing from these findings are the long-term effects that the programme has generated in its participants (rather than its viewers), and whether these effects have enabled the show’s participants to lead positive civic change in their communities through their newly acquired skills. The skills and knowledge gained in public policy-making and political processes by the final contestants in the show are substantial. The impact of such skills development goes beyond the involvement in the TV programme, and it needs to be examined and understood. Hence, the aims of this research were:

to understand the extent to which The President has had a long-lasting effect on its participants

to determine how/if participants have applied the skills gained through the programme in their daily lives;

to ascertain how the acquired knowledge on civic engagement has shaped participants’ lives

to find out whether this knowledge has led the participants to becoming engaged in civic projects or activities in their communities.

In 2021, the final five contestants of each series of the show (2013 and 2015) were invited to participate in this study. This number wanted to include those contestants who had taken part in all of the hands-on coaching and tasks that were built into the last five episodes of the show, in addition to the two finalist who were also involved in the town hall debate. Eight people accepted (seven male and one female), one withdrew after participating, and one declined to participate. Semi-structured interviews were carried out online via Zoom. Participants also took part in a timeline drawing exercise, facilitated by the interviewer. In this article, however, no visual data analysis is included, and the inquiry focuses on data collected primarily through the interviews. Questions revolved around participants’ current interests and career; their views on the knowledge gained through the programme, and whether this influenced their life trajectory; their level of civic engagement (and involvement in relevant activities); and their thoughts about civic engagement and peacebuilding in the Palestinian context.

Framework of analysis and findings

The intentional and strategic use of media and communication technologies in order to achieve positive change in society forms the basis of Communication for Development processes (Wilkins and Mody Citation2001). When Communication for Development takes on a participatory approach, it enhances the role of communities in advocating for change based on locally owned development goals. A participatory model in C4D sees communities directly engaged in identifying problems and their solutions through media and communication (Wilkins Citation1996).

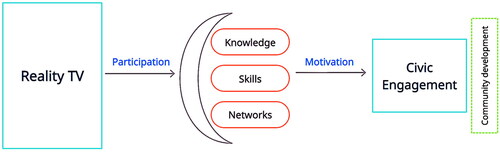

Based on these and other ideas presented previously through the literature, a framework of analysis has been built. This emphasizes the connection between the participation in Reality TV, the strategic C4D design of programmes adopting this format (as presented in the aims of The President show discussed earlier), and civic engagement as the social benefit that wants to be achieved. visualizes this framework:

This framework includes variables that are helpful in understanding participants’ pathways from The President Reality TV programme to their present life experience, as a result of the coaching and activities built into the show. All interview transcripts were coded and themed in NVivo. Themes arising from participants’ responses were assessed against this framework, allowing the researcher to draw a correlation with its variables. Findings are presented below through a breakdown of its components. Obstacles to the application of the model in practice have also been identified. This study did not observe the variable of community development, which would require the engagement in research of a broader section of the population in order to be assessed; however, it assumes that the active and positive involvement of individuals in civic practices contributes to the social health and awareness of their communities.

Knowledge

All participants referred to the activities that were planned as part of the show as extremely valuable. Such activities were foundational to their learning, particularly in relation to the political arena, both local and international. They also provided an understanding of mechanisms at various levels.

The program had multiple stages and these stages included multiple tasks we were asked to carry out. Some of these tasks were collective, I mean group work, and some individual. Regarding the individual [tasks], actually, these focused on presenting and showcasing your own product as an individual participant. I assumed multiple individual responsibilities that included acting as a Palestinian minister and acting as an ambassador to another country within the region.

I carried out, in addition, other group tasks related to humanitarian work, especially those related to supporting people with special needs and people residing in the border areas that are close to the settlements in the West Bank. We communicated with them on how best we could help them and how they can introduce or communicate their own problems, especially those related to settlers’ attacks and settlers taking away their land.

These tasks actually were very related to how we can develop the reality in Palestine; so they were multiple and they were related to services inside Palestine as well as regional and international relations, especially those related to foreign affairs including affairs with Israel and international and regional stakeholders. Participant 2

It gave us a unique perspective into the political life and how decision making is carried out at the political level; and how national institutions are managed and decisions are taken. Participant 5

Not only did the knowledge gained through the activities and trainings built into the show allow participants to progress to the next stages of the competition, but it also provided them with key insights into social problems and complex political scenarios in real life. This determined where their interest and focus were placed subsequently in their lives.

What was more important, actually, is the self-study part of the experience. The experience has instilled in us the interest to learn and to continue to search for information, get updated information, and upskill according to what we need. That created a motivation for participants to continue in the journey of searching, identifying statistics, and following up with the updates in different countries around the world, especially when it comes to training on decision-making. Yes, this is the part of the training that I think was significant. Participant 3

They gave us political training about Jerusalem, about East Jerusalem, about the division between West Bank and Gaza; they gave us training about the core issues between us Palestinians and Israelis about, for example, water, about settlements, about borders, security, refugees. This political training has helped us a lot because it has increased my awareness about some political issues; and a lot of the questions that came up from the judging committee were political questions, and to answer these questions you had to be aware of all the political issues that are going on around you. This is the thing that I think was important for us, and it had a real impact, the political training that we took. Participant 4

I had the opportunity to get introduced to a number of cases and issues related, for example, to diplomacy and the work in the diplomatic field, the work with NGOs in Palestine, and how to confront the apartheid wall constructed by the Israelis. We got introduced to topics on how to differentiate between a political leader and a military leader, and we had the chance to read a lot of articles as part of assignments given to us, which have contributed to our insights and perspectives. Participant 6

Many of the activities also involved real life role-playing. This appears to have facilitated an understanding, for participants, of what it was like to be effectively in the shoes of a politician or a diplomat. A participant expresses this idea clearly through his words:

The most important thing was when we practiced the role of ministers or ambassadors. So I was the Minister of Social Affairs in our community […] I was a minister for one day and I practised the real role of minister. Before that, I used to say, ‘Oh, the ministers, they’re not doing anything in their lives, they’re just driving a nice car and they have prestige, that’s it’. I was also in the role of Palestinian Ambassador in Jordan. Because things are very difficult for us Palestinian youth, as we are suffering from the political and economic situation in our life, we are always saying that our ministers are corrupted, that they are not doing their job properly; but when you put yourself in their shoes, you will see something different and this is what I saw. When I practised the real role of minister or ambassador, I changed my mind about a lot of things, and I see that there’s something different about what we see on TV or on media, for example. It was a good experience for me. Participant 4

Skills

The various activities and training opportunities embedded in the show provided participants with a wealth of new skills. Participants spoke highly of the experience gained and the unique prospect that opened up to them not only from gaining those skills, but also when learning from respected figures in the Palestinian society.

I had the opportunity of being trained on how to present myself in front of political elites like the Palestinian Prime Minister as well as the Vice-Chancellor of Al-Quds University. Meeting them, speaking to them and receiving feedback from them, and sometimes even exchanging some hard-to-accept messages. I had the opportunity to meet with the Minister of Culture and the Palestinian Ambassador to the United Kingdom, who actually was a big motivator in my experience in the show. I had the opportunity to communicate my concerns and my messages in front of decision makers who occupy elite position in the Palestinian Territories […] I also had the opportunity, with other participants, to get introduced to the presidency protocol, including the etiquette of introducing yourself, dealing with the presidential guard, the dining table etiquette, the etiquette of walking as well as how to deal with the security zones in Palestine. Participant 5

The training that we took from The President TV show, and the things that we felt in our community, helped me a lot and has developed my skills; it developed my skills even socially. Participant 4

I undertook training on how to give a speech and how to present myself live on stage, and how to give a speech to large audiences. To present myself as the president, I had to give a speech within 90 seconds. We had to go through a lot of training to shorten what we were thinking about and what we wanted to say, how to stand confidently, and how to present ourselves confidently. Participant 6

At the task level, the programme is excellent and probably in the second series of the show, there was bigger participation and presence of diplomats who are present in Palestine. I could see that they had been given a designated area to participate in the show. Different delegates from the international community including delegates from the UK, the United Nations, Jordan, Turkey, and Egypt were there, and they had the opportunity to get introduced to the Palestinian perspectives and viewpoints. The show was absolutely great. Participant 2

Role-playing was a key activity that the last few contestants in the show were able to take part in. Whilst individual experiences differed, there was agreement on the value attributed to this activity. Moreover, besides gaining knowledge into specific fields (as discussed previously), this activity developed participants’ skills in a broad range of areas that can be transposed into civic life.

I played the role of Al-Quds Governor, I played the role of the Chair of the electricity company in Jerusalem, and the role of Ambassador to Ankara, Turkey. I also played the role of the Minister of Culture. Participant 5

Contestants in the other two zones [East Jerusalem and West Bank] had the chance to play [the roles of ministers and ambassadors] more seriously than we did. We played similar roles, but it was really a matter of playing the game here in Gaza Strip. We played particular social roles such as planning and caring for the orphans, and running campaigns to raise money for them. We were also involved in other initiatives such as how to develop the reality of the youth in Gaza Strip. Participant 1

I took on different roles, and these included acting as the Mayor of Al-Khalil Municipality, and I managed to work on developing an action plan to solve a number of problems. As you know, the municipality of Al-Khalil, that is Hebron, is very complicated; so that experience was interesting for me. Another role I took on was acting as the Minister of Women’s Affairs, where I proposed a program to defend women’s problems and how to ensure that women have access to their political rights. A third role was to act as the Palestinian Ambassador to Germany, where I had the opportunity to learn about the situation of the Palestinians in Germany and how to mobilize international support for the Palestinian issue. I had the opportunity to work hard in order to run for the president title […]. That helped me to formulate holistic solutions to multiple problems facing Palestinians and the Palestinian Territories. Participant 8

One participant recounts in details his experience with role-playing and the long-lasting impact this had on him:

They chose me to be the Ambassador of Palestine in Jordan, so I went there [to Jordan]. At the beginning, they took me from the hotel to the Embassy in the real car of the Ambassador with the guards and everything. I went there and I shook hand with the real Ambassador. He starts to explain to me about the impacts of Palestine in Jordan, about their activities, what they are doing with Palestinian people, with their international and national relations with other embassies. Then, they walk me around the embassy to show me all the places and introduce me to the employees, the managers, and the other diplomats. They introduce me to all of them and after that, we go to the Ambassador office and he says, ‘The chair is for you, now you are the real Ambassador, I have to leave’. He really left the Embassy to, I don’t know, to his home or whatever, and I spent all the day as the Ambassador. I followed up on the agenda of his day.

Based on his agenda for that day, there was a meeting with the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Jordan. I attended this meeting. There was another meeting with the Deputy Ambassador of the Emirates. I attended this meeting. There was another meeting with some Palestinian people from Gaza; they came for an international training in Jordan and wanted to greet the Palestinian Ambassador, so I went to this meeting. And I then followed up with the rest of the daily activities. I also went to the reception [desk of the Embassy] and I asked people who came to receive service from our Embassy, ‘How can I help you?’ It was a real thing that I felt, and it was amazing for me. Even until today, I keep sharing with my friends how much this impacted me. For the following three years or so from the show, when I needed something from that Embassy and went as a visitor, all the employees and the guards were saying they saw me, ‘Oh, this is the small Ambassador. Okay, come and join, please’. It was a good experience for me. Participant 4

Networks

The show enabled some of the participants to create both personal and professional networks. For these former contestants, those networks have proven to be valuable also in their lives after the show.

The participation has been at a large scale and the connections created are at the entire Palestinian level. This includes creating networks in northern Palestine, southern Palestine, Al-Khalil… I wasn’t that connected before the show. After that, I became more connected with multiple groups of youth and even these groups are connected to larger groups that are operating at national level in the service of the Palestinian community through multiple activities and by supporting multiple causes, including political and social issues. Participant 2

After The President TV show, a lot of organisations even called us because they knew I was one of the last three contestants, I was one of the last few ones who remained and a lot of organisations put their eyes and on us. They started offering me jobs because I was on The President TV show. Participant 4

The President show made my life easy when it came to my work as a journalist, because I was well-known to the politicians as well as to the Palestinian people […] Probably for someone else, it would have been difficult to have such a network of connection; but the show facilitated having this. These connections continued even after the show. Even when I want to attend or to be part of any coverage, I just give a ring to any of my connections and they are there ready to help me get through as a journalist and do the coverage. Yes, the connections I created through the show have made my life easier. Participant 7

I had a connection with the Prime Minister and other ministers, and I’m happy to have this kind of relationship. I’m also happy to continue to have a long line of relationships with Palestinians from different areas in Palestine, including the West Bank, Gaza, Nazareth and other areas. I consider these connections as a great resource, as a minefield of minerals. Participant 5

Motivation

The show provided a space for participants to be visible and heard, in a reality that does not leave room for the youth to be change-makers in the political sphere. Some of the former contestants talked about how significant that space was for them and the motivation arising from being at the front seat of proposing political solutions after listening to the people.

Because of the ongoing division in the Palestinian context, we haven’t got the chance to join or to participate in any real political process. The show was very special in terms of giving us the chance to express our ideas, our dreams, our ambitions and our political propositions as well. I was 23 years old when I joined the show. Meanwhile, the youngest figure in the political regime was about 60 years old. I was so young and the political regime itself was so old. Although the show doesn’t reflect the real world, at least it gave us the chance to convey our ideas and our opinions to the world. It was unique especially considering the participants coming from three different regions: from the West Bank, Gaza Strip and the 1948 people in Israel. Participant 1

This show came in a moment when we, in the Palestinian Territories, missed holding political elections in a long time. It provided us with a good space to express our political opinions even virtually and through TV. We could express our viewpoints about the political space in Palestine and how we might act once we are in decision-making positions. Participant 8

Participants also talked about the encouragement received and the sense of empowerment elicited in them through their involvement in the tasks laid out in the programme. The sense of agency experienced during the show has translated into current interests and even in a stronger sense of self.

I worked as Palestinian ambassador, minister of communication, etc. That gave me actually a great sense of empowerment, and I felt like I could contribute to bringing about change in reality, if I were given the chance […] Although the experience is now eight years old, one of the key moments for me was my visit to Al-Khalil city. It was my first visit to the city, ever. During that visit, I watched closely the reality of settlement in that city […] That visit was so special and created in me the warmth to continue to learn about the reality of settlement in that city, to the point that in my master’s study, I made the subject of that visit the topic of my research. The research was about the reality of settlement in the city of Al-Khalil. Every time I go in that direction, I make sure that I visit Al-Khalil and the Old City, because now I feel responsible for that reality. I need to know about the updates in that area. Participant 3

I was very glad to see the youth support my vision and my ideas. Although it was a TV program, actually I received a lot of support for my ideas and my vision. That was evident from the messages I received from Palestinians living in Australia and Canada, and in other parts of the world. Even during the show, I received a lot of messages from people in Japan, Jordan, Tunisia, Algeria, Yemen, and every place in Palestine. All the support to my ideas, both when I was on stage and throughout the programme, actually gave me a push forward and I feel very indebted too […] Being involved in the show as a participant, and having the opportunity to lead a campaign that has been supported by friends, relatives and many others, has positively impacted me psychologically, emotionally and cognitively. Participant 5

Civic engagement

Even though to various degrees, all participants are presently engaged at a civic level. Either through voluntary work, political involvement, advocating for people’s rights or leading a movement, the show’s finalists appear to have developed a willingness to bring about change in their community by joining or initiating relevant activities.

I have run a training, as voluntary work, for hundreds of students in life skills, social responsibility, different topics besides my teaching […] It was a great chance and still is. Thousands of students need guidance for their future. I am proud to be part of this work. Participant 2

I continue to defend the Palestinian prisoners and I continue to defend those detainees. I volunteer in cases related to Palestinian people who are poor and financially unable to pay to have their cases defended through other lawyers. I provide support to official institutions and organizations that are facing challenges […] Currently, I am volunteering in legal and law-related areas. I hold seminars and workshops to teach people about their rights: political, economical and social rights. Participant 5

I have been and still am active in the social domain through my youth work. Especially being involved in campaigns promoting human rights and programmes targeting the Palestinian youth for training and capacity building, as well as advocacy and awareness raising campaigns in several fields and through a number of Palestinian institutions. Participant 8

Some participants also talked about how their understanding of civic engagement changed as a result of their participation in the show. Their answers truly demonstrate the shift in perspective that occurred in some, and the important role that this played in their lives subsequently.

My understanding of the concept was different, before and after. For instance, before, I thought that citizenship, for instance, entails having rights; but from the show, I learned that citizenship entails having rights and also commitments. You are committed to do something as well […] That helped me and encouraged me to work to improve the reality, and to encourage others to get engaged in volunteering and campaigns. I have learned that rights should not be given to someone: they should be taken, because they are your rights. Participant 1

[The show] has encouraged me to start reading more about political issues, to start to think more about the current situation. Think more and read more and devote myself to the political sphere and to be more aware of what is going on on the ground and in the region […] After the TV show, I started focusing on political, economic, social issues in my community and in my region. If I have a meeting or if I have an invitation to speak on radio or TV, I have to be aware of political issues. This is on one side. On the other side, after the TV show, I have felt a good relationship with everybody. When I went to any ministry, for example, or any embassy for Palestine, and I saw something wrong before The President TV show, it was okay. I was thinking: something wrong? What can they do? Now, I send an email or a message or call a minister or ambassador, ‘Please, I saw something wrong. Please, you can change this’. You can ask. I feel myself now being part of the change. Participant 4

My understanding of civic engagement has changed from where it was before my participation in the show because I got involved in the work, in the civic engagement business itself and I got involved in its mechanisms. Yes, we have in Palestine female pioneers in the field of politics and economy, but I used to look at them from a distance like, ‘oh, it is difficult to get where they are now.’ No, actually after the show, I realized that it is not difficult and it is something close. We can get there as long as we can communicate our voice, we can communicate our messages, and we get the right information, experience, and skills in politics and the economy. Participant 7

Obstacles

Whilst the interviews conducted demonstrate the connection between participation in the Reality TV show and civic engagement, contextual obstacles also need to be acknowledged. Participants were very honest in their discussion on the limitations that any form of civic engagement carries in the Palestinian Territories, despite the encouragement and support provided to the youth by the show, which also extended to its young audience. Respondents described the situation, particularly in relation to political involvement, that the youth face in their everyday life and the constant disillusionment that even the most active have to suffer from.

In our community, as in generation, we have lost the hope. Why we have lost hope? Because we don’t have any change in our lives, we don’t have any change in our political life. There is no election for presidency, there is no election for parliament. If you are looking at our ambassadors or our ministers, or anyone in the decision-making level, you will see that they are more than 65, 70 years of age; so we don’t feel as youth that we have hope, or we have our chance to be in the decision-making level. Participant 4

I can say that people here are depressed from the leadership and from the political situation here. In order for civic engagement to have a positive influence on the youth, the start is not from the youth upward, but from people at the top downward. The leadership should bridge the relationship with the Palestinian youth, to engage them civically and politically in a rational way that respects their dignity and respects their views of how things should be done. Participant 5

As Palestinian youths, we have a lot of problems and these problems are not all related to the Occupation. There are a lot of problems we can contribute to solving, such as problems related to jobs and job creation, good governance, and accountability. During the show, we had the chance to express ourselves and our vision on how to solve such problems, but in reality, we are not given the chance to be part of the solution of these problems. The political leadership does not give a chance for other leaders to be introduced to the political regime or to contribute to decision-making. The political parties do not allow us to contribute to any change. Participant 6

While the potential of civic engagement to build and preserve peace was recognized by all participants, the complex situation of the Territories is met with bitter acknowledgement from respondents about the limit that this set of practices has in this particular context:

When it comes to the topic of peace, it is a dialectic. It is a problematic concept in general, because the other partner is not serious and not interested in reaching any peaceful settlement, and doesn’t give the real chance to realize peace. We are in favour of peace, but the other party is not interested in reaching any serious settlement in this regard. Peace is possible only after giving the rights to the Palestinians, and after the other party becoming committed to the rights of the Palestinians. Participant 3

There’s a link between civic engagement and peace. That can be seen through the ambitions of the youth to see freedom, independence, and achieving dignity. I think realising peace and these values is again conditioned by the so many practices of the Occupation for what this is. I’d like to mention here a say or a motto that I’m convinced of, which is that the last day of Occupation is our first day of peace, because it is the Occupation that is bringing a lot of challenges for the youth and in their lives. The Occupation is preventing and hindering the youth from realizing their dreams and hindering the efforts put for development and to realize independence and a life of dignity. As long as there’s Occupation, challenges to meet peace, even through civic engagement, will remain. Participant 8

In relation to contextual restraints, one participant also raised the important and relevant point of fragmentation within the youth in the Palestinian Territories:

The division between Gaza and West Bank affects us a lot. I’m from the West Bank, I don’t have any information about people from Gaza. I have one friend from Gaza, they don’t know anything about the West Bank; they have never even entered the West Bank. A lot of young people here, they have never entered Gaza. When I went to East Jerusalem, for example, I met people from East Jerusalem who were planning civic engagement initiatives. We discussed them together. There is a big gap between even the young generation who lives in East Jerusalem and the one who lives in the West Bank, even though they are only two kilometres apart. Because of this, we have lost everything. Participant 4

Strengthening civic engagement through media participation

This study has shown how the application of a C4D strategic design can shape a Reality TV show into a launching platform for civic engagement. Through their participation in the programme, and specifically in the last few episodes, contestants underwent three key stages:

knowledge development. The coaching provided and the tasks participants became involved in offered unique knowledge and insights into the dynamics of local politics, economic situation, as well as diplomatic and international relations.

skills development. Thanks to the training received through their participation in the show, contestants acquired a crucial skillset that has enabled them to navigate the world of politics and related domains in a professional and informed manner.

network creation. Those gravitating around the TV show were both ordinary people, who supported the contestants’ campaigns, and political and diplomatic figures. This network of individuals has, for some participants, proven to be significant in their life after the show.

The combination of these processes upheld participants’ motivation in maintaining a level of civic engagement throughout their lives even after five to eight years since the end of the show. Volunteering, political activism, participation in social movements, campaigning and mentoring, are some of the civic practices that the former contestants continue to be engaged with. In addition to these, the show has also guided them towards the acknowledgement that everyone can have a role to play in making a difference, and of the importance of overcoming the often-felt sense of powerlessness.

In line with this point, while the findings presented here are overall positive, there are obstacles to the development of a strong civic engagement among people in the context of Palestine, which have been considered. These are related to the political, economic, and social situation that Palestinians, and particularly the youth, are experiencing. The limitations imposed on people’s rights and freedom by the occupying forces, the complexity of the relationships with countries around the world, and the unsteady political situation in place in the Palestinian Territories of West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem, mean that any effort connected to civil engagement may, ultimately, bear little fruit. Yet, the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and networks remains key for young people to stay motivated and contribute, at a civic level, to the development of their communities.

Whilst specific vocational paths have not been discussed in this article in order to preserve research participants’ confidentiality, the involvement of former contestants in civically-engaged practices runs alongside careers in politics, education, media, human rights and law, amongst other fields. The engagement of the former contestants in civic activities that may be connected with but certainly go beyond their current occupation, is also synonym of the interest and motivation that each one of them still holds towards influencing change.

Conclusions

This article has shown how, when rooted in C4D practice, Reality television can be designed with the purpose of achieving social benefit. In particular, the study presented here has discussed the experience of the former contestants from The President TV show, broadcast in the Palestinian Territories in 2013 and 2015. Finalists from each series, who underwent an intensive training and coaching in a broad range of areas including politics, economics and international relations during the last few episodes of the show, have been interviewed. Their responses have been analysed in light of a framework that shows the pathway from participation in Reality TV to civic engagement. This has been built on notions from Communication for Development, which drove the aims of the show.

After an introduction of the situation of the youth in Palestine, the literature reviewed in this article has discussed how civic engagement still lacks a clear definition. Yet, a number of concepts related to it appear to recur in the work of different scholars and organisations. At the same time, Reality TV has become another object of attention for researchers in a different field, and its evolution both in genre and popularity has been considered. Following these reflections, C4D has been brought in as a bridge between the two, in order to assist on shedding light on relevant processes arising from this study.

In conclusion, the group of finalists from the two editions of The President had the unique opportunity to be part of this capacity building exercise that the Reality TV show encompassed. Yet, as Interpeace (Citation2017) also highlights, ‘promoting peacebuilding, security and violence rejection cannot rely on an élite sector of active young people only, but rather requires reaching the largest segment possible of young people to engage them in this process’ (27). This study leaves space for reflection on how Communication for Development strategies can be designed to build capacity of young people in the civic sphere through the use of the different media formats, at a larger scale. In particular, examining the dynamics that drive the connection between active civic engagement and youth-led positive social change in the Palestinian context could be useful to develop knowledge on how media-based civic engagement interventions among the youth can contribute to peace, stability, and development in the Territories.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Valentina Baú

Dr. Valentina Baú works as a Senior Research Fellow at Western Sydney University (Australia). Both as a practitioner and as a researcher, her work has focused on the use of the media & communication in international development. She has completed a PhD on the role of participatory media in conflict transformation and reconciliation after civil violence. Her present research explores different theoretical frameworks and practical applications in the area of Communication for Development in Peacebuilding. Valentina has collaborated with international NGOs, the United Nations and the Italian Development Cooperation, and has worked in different contexts in Africa and Asia. Her experience involves the implementation of both research and media projects with victims and perpetrators of conflict, displaced people, refugees and people living in extreme poverty. Her work is published on established academic journals as well as renowned online platforms.

References

- Adler, R. P., and J. Goggin. 2005. “What Do We Mean by “Civic Engagement”?” Journal of Transformative Education 3 (3): 236–253. doi:10.1177/1541344605276792.

- Alpha. 2016. Final Evaluation Study. Creating the Next Generation of Palestinian Democratic Leaders (the President) Project. Rawabi: Alpha International for Research, Polling and Informatics.

- Amnå, E. 2012. “How is Civic Engagement Developed over Time? Emerging Answers from a Multidisciplinary Field.” Journal of Adolescence 35 (3): 611–627. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.011.

- AWRAD. 2013. Opinion Poll of the Palestinian Youth. Ramallah: Arab World for Research & Development. Accessed 8 October 2021. https://www.awrad.org/en/category/2119/1/Youth–-Related-Polls

- Baú, V. 2015. “Building Peace through Social Change Communication. Participatory Video in Conflict-Affected Communities.” Community Development Journal 50 (1): 121–137.

- Baú, V. 2016. “Citizen Engagement in Peacebuilding. A Communication for Development Approach to Rebuilding Peace from the Bottom Up.” Progress in Development Studies 16 (4): 348–360. doi:10.1177/1464993416663052.

- Baú, V. 2019. “Radio, Conflict and Land Grabbing in Sierra Leone.” Media, War & Conflict 12 (4): 373–391. doi:10.1177/1750635218789434.

- BBC Media Action. 2015. Reality TV for Resilience: Can Reality TV Help Communities to Better Cope with Climate Risks? London: BBC Media Action.

- Bokai, D., D. F. Forero, P. Garcés, J. Peralta, and K. Shieh. 2013. Social Media and Civic Participation: Literature Review and Empirical Evidence from Bangladesh and Palestinian Territories. London: London School of Economics and Political Science & BBC Media Action. Accessed 8 October 2021. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/pdf/LSE_social_media_governance_research_report.pdf

- Burger, M. 2012. “Social Development, Entertainment-Education, Reality Television and the Public Sphere: The Case of Zola 7.” Communicatio 38 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/02500167.2012.662161.

- Chan, M., and A. Jekinson. 2017. “Influence on Reality TV Show on Moral Development.” INOSR Arts and Humanities 3 (1): 9–14.

- Christophersen, M. 2016. Are Young Palestinians Disengaged, or Merely Dissatisfied? New York: IPI Global Observatory. Accessed 8 October 2021. https://theglobalobservatory.org/2016/08/palestine-gaza-west-bank-youth/

- de Zúñiga, H. G., L. Copeland, and B. Bimber. 2014. “Political Consumerism: Civic Engagement and the Social Media Connection.” New Media & Society 16 (3): 488–506. doi:10.1177/1461444813487960.

- de Zúñiga, H. G., N. Jung, and S. Valenzuela. 2012. “Social Media Use for News and Individuals’ Social Capital, Civic Engagement and Political Participation.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17 (3): 319–336. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01574.x.

- Dusouqi, M. n.d. Promoting the Youth Role in Political Participation and Decision-Making Process. Policy Paper. Ramallah: Palestinian President’s Office.

- Ekström, Y., and L. Helgesson Sekei. 2014. “Citizen Engagement through SMS? Audiences ‘Talking Back’ to a Reality TV Edutainment Initiative in Tanzania.” In Reclaiming the Public Sphere. Communication, Power and Social Change, edited by T. Askanius and L. Østergaard, 184–200. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Farnham, S., D. Keyes, V. Yuki, and C. Tugwell. 2012. “Puget Sound off: Fostering Youth Civic Engagement through Citizen Journalism.” In CSCW ‘12: Proceedings of the ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Association for Computing Machinery, edited by S. Poltrock and C. Simone, 285–294. New York.

- Fasheh, W. A. 2013. “The Status of Youth in Palestine.” Sharek Youth Forum in Palestine. Accessed 8 October 2021. http://sharek.ps/attachment/2/sharek%20report%202013%20(1).pdf

- Internews. 2007. Palestinians and the Media: Usage, Trust and Effectiveness. Washington DC: Internews.

- Interpeace. 2017. Palestinian Youth: Challenges and Aspirations. A Study on Youth, Peace and Security Based on UN Resolution 2250. Washington DC: Interpeace and Mustakbalna.

- Kavka, M. 2021. Reality TV. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Lance Bennett, W., C. Wells, and D. Freelon. 2011. “Communicating Civic Engagement: Contrasting Models of Citizenship in the Youth Web Sphere.” Journal of Communication 61 (5): 835–856. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01588.x.

- Lee, N., D. V. Shah, and M. McLeod. 2013. “Processes of Political Socialization: A Communication Mediation Approach to Youth Civic Engagement.” Communication Research 40 (5): 669–697. doi:10.1177/0093650212436712.

- Lerner, R. M., J. Wang, R. B. Champine, D. J. Warren, and K. Erickson. 2014. “Development of Civic Engagement: Theoretical and Methodological Issues.” International Journal of Developmental Science 8 (3–4): 69–79. doi:10.3233/DEV-14130.

- Loader, B. D., A. Vromen, and M. A. Xenos. 2014. “The Networked Young Citizen: Social Media, Political Participation and Civic Engagement.” Information, Communication & Society 2: 143–150.

- Mainsah, H., P. B. Brandtzaeg, and A. Følstad. 2016. “Bridging the Generational Culture Gap in Youth Civic Engagement through Social Media: Lessons Learnt from Young Designers in Three Civic Organisations.” The Journal of Media Innovations 3 (1): 23–40. doi:10.5617/jmi.v3i1.2724.

- Miranti, R., and M. Evans. 2019. “Trust, Sense of Community, and Civic Engagement: Lessons from Australia.” Journal of Community Psychology 47 (2): 254–271. doi:10.1002/jcop.22119.

- Niedzwiecki, C. S., and P. L. Morris. 2017. “Reality Television.” In SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, edited by M. Allen. London: SAGE Publications.

- Paluck, E. L. 2012. ‘ “Media as an Instrument for Reconstructing Communities following Conflict.” In Restoring Civil Societies: The Psychology of Intervention and Engagement following Crisis, edited by K. Jonas and T. Morton, 284–298. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- PCBS. 2021. On the Eve of the International Youth Day Issues a Press Release Demonstrating the Situation of the Youth in the Palestinian Society. Ramallah: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Accessed 8 October 2021. https://pcbs.gov.ps/site/512/default.aspx?tabID=512&lang=en&ItemID=4046&mid=3171&wversion=Staging

- Ramafoko, L., G. Andersson, and R. Weiner. 2012. “Reality Television for Community Development.” Nordicom Review 33 (17–18): 149–162. doi:10.2478/nor-2013-0032.

- Rogers, T., K. Winters, M. Perry, and A. LaMonde, eds. 2014. “Youth Literacies: Arts, Media, and Critical Literacy Practices as Civic Engagement.” In Youth, Critical Literacies, and Civic Engagement: Arts, Media, and Literacy in the Lives of Adolescents. New York: Routledge.

- Sana, Y. 2009. “The Palestinian Youth Role in Policy-Making at Youth Organisations and Impact on Development: Volunteers at Partner Organisations of the Bisan Centre for Research and Development as a Model 2000–2007.” Unpublished MA Thesis, An-Najah National University.

- Skuse, A. 2017. “Radio Drama, Gender Discourse and Vernacularisation in Afghanistan.” Gender, Technology & Development 21 (3): 217–231. doi:10.1080/09718524.2018.1434991.

- Skuse, A., and M. Gillespie. 2011. “Gossiping for Change: Dramatising ‘Blood Debt’ in Afghanistan.” In Drama for Development: Cultural Translation and Social Change, edited by A. Skuse, M. Gillespie, and G. Power, 273–294. London: SAGE Publications.

- Sloam, J. 2014. “The Outraged Young’: Young Europeans, Civic Engagement and the New Media in a Time of Crisis.” Information, Communication & Society 17 (2): 217–231. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2013.868019.

- Smith, R. M. 2017. “New Voices and Narrative Participatory Photography.” In Handbook of Research on the Facilitation of Civic Engagement through Community Art, edited by L. N. Hersey and B. Bobick, 276–293. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Tufte, T. 2012. “Facing Violence and Conflict with Communication: Possibilities and Limitations of Storytelling and Entertainment Education.” In Development Communication in Directed Social Change: A Reappraisal of Theory and Practice, edited by S. R. Melkote, 80–94. Manila: Asian Media Information and Communication Centre (AMIC).

- Warren, A. M., A. Sulaiman, and N. Ismawati Jaafar. 2014. “Social Media Effects on Fostering Online Civic Engagement and Building Citizen Trust and Trust in Institutions.” Government Information Quarterly 31 (2): 291–301. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2013.11.007.

- Wilkins, K. G. 1996. “Development Communication.” Peace Review 8 (1): 97–103. doi:10.1080/10402659608425936.

- Wilkins, K. G., and B. Mody. 2001. “Reshaping Development Communication: Developing Communication and Communicating Development.” Communication Theory 11 (4): 385–396. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2001.tb00249.x.

- Wray-Lake, L., A. Metzger, and A. K. Syvertsen. 2017. “Testing Multidimensional Models of Youth Civic Engagement: Model Comparisons, Measurement Invariance, and Age Differences.” Applied Developmental Science 21 (4): 266–284. doi:10.1080/10888691.2016.1205495.