Abstract

This article explores ‘songwriting camps’, a contemporary form of collaborative music creation initiated primarily by record labels and music publishers but also by producers and enthusiasts. In such camps, musicians produce songs for various purposes, from commercial exploitation to self-actualization. This research explores the origins of industrialized songwriting, collaborative songwriting practices, and current thinking on creativity and copyright with a view to interrogating how songwriting camps relate to commercial songwriting practices in popular music since the early twentieth century. We find that camps have a proven track record of producing commercially successful pop songs and are deemed beneficial by songwriters for developing their careers and skills, networking, gaining industry contacts, and generating royalty income. We argue that while camps have adapted to the post-industrial age, characterized by digital music creation tools aiding musicians, they owe more to the past than is perhaps acknowledged. Songwriting camps are a microcosm in which many of the same tensions, strategies, goals, and relationships can be observed as in past structures from the Brill Building era, or organizations like Motown. Camps draw on features from these historical examples, such as: strategic, time-limited collaboration, clearly delineated roles, friendly competition among writers, and group evaluation.

Introduction

In 2015, David Hajdu, music critic for The Nation, published a review of John Seabrook’s book The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory (2015), in which he criticized the author for adopting an industrial scheme to explain contemporary pop songwriting and production. Where Seabrook had based his interpretation of modern songwriting on the historic working routines of successful music organizations like Motown, Hajdu (Citation2015) argued that music production has entered a post-industrial age in which the song factories have closed, and the old tropes of the machine era no longer adequately explain the organization of creative work by songwriters. In this article, we argue that while the tools and processes of contemporary commercial songwriting have evolved, they owe a greater debt to the past than has previously been acknowledged. Drawing on the popular model of the ‘songwriting camp’, this research explores the current state of the art in professional collaborative songwriting and makes connections between those practices and the origins of industrialized songwriting. We find that songwriting camps make use of and engage with features present in historic examples of songwriting practice, including strategic, time-limited collaboration, clearly delineated roles, encouraging competition among writers, and group evaluation.

Songwriting is at the heart of popular music; the song is essential to a musical product (usually a recording), its performance, dissemination, and commercial exploitation. In recent years, questions about what constitutes pop songs and how they are written have gained public interest. This is revealed in music documentaries such as the BBC’s Secrets of the Pop Song (Chambers Citation2011), Netflix’s Song Exploder (Hirway Citation2020), and Worth Repeating (Hodges Citation2010), movies like The Last Songwriter (Barger Elliott Citation2016) and It All Begins With A Song (Chusy Citation2018), and podcasts like Sodajerker (Barber and O’Connor Citation2011), with over 250 episodes to date. Notwithstanding this public interest in songwriting and the rich body of academic literature on ‘popular song’ (e.g. Comentale Citation2013; Moore Citation2013; Mullen Citation2015), research on songwriting is still in an embryonic state; it remains scattered throughout general popular music publication outlets and in industry-oriented fields such as the art of record production (Frith and Zagorski-Thomas Citation2012; Zagorski-Thomas et al. Citation2019) and music business and industry studies (Anderton, Dubber, and James Citation2013; Hull, Hutchison, and Strasser Citation2011), as well as in publications outside of the music discipline (e.g. de Laat Citation2015; Schiemer, Schüßler, and Theel Citation2022). A dedicated field of songwriting studies, attempting to bring such material together under one interdisciplinary umbrella, is emerging, with its dedicated Songwriting Studies Journal due in 2024.

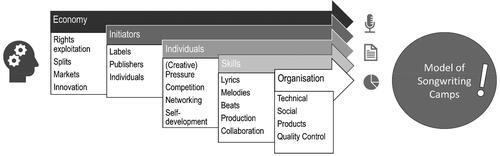

This article is the first output of a cross-national (United Kingdom and Germany) funded project, Songwriting Camps in the 21st Century, that seeks to explore the various forms and purposes of songwriting camps in Western contemporary culture. In particular, the project aims to understand the purposes, organizational aspects, participants, activities, and outcomes of songwriting camps, focusing on creative processes, economic issues, and the community of songwriters (). Songwriting camps are a contemporary form of collaborative music creation initiated by record labels, publishers, music rights societies, and other professional bodies in which songwriters spend a short period of time together (usually less than a week) writing songs, often for a predetermined project or brief. Though the format and aims of such events may vary, this form of creative retreat is well established; for example, The Police manager and I.R.S. record label founder Miles Copeland has convened selected songwriters at the Château de Marouatte, France, since the 1990s, first with Almo Irving Music Publishing, then with Warner Chappell.Footnote1 When, where, and in what context the term ‘songwriting camp’ was originally coined is unclear. Although collaborative songwriting and production have long been common in popular music, places like Motown in the 1960s were not typically referred to as songwriting camps and should probably not be considered as such. That is because camps typically involve a temporary gathering of songwriters, producers, and occasionally performers in studios, workshops, or remote retreats. Copeland’s retreats at the Château de Marouatte may thus have been one of the earliest instances of a modern songwriting camp, yet it is unlikely that they were already referred to as such. According to Seabrook’s (Citation2015) history of hit factories, which does not mention Copeland’s retreats, songwriting camps seem to have become a phenomenon in the late 2000s through Def Jam’s L.A. Reid in connection with an album production for Rihanna. This ‘first’ camp for Rihanna’s album Rated (Rihanna Citation2009) did not take place in a closed studio complex but spanned a fortnight throughout Los Angeles. However it originated, the term ‘songwriting camps’ appears to have proliferated due to the popularity and success of this format and has since been used for writing retreats and workshops in professional songwriting, leisure, and education. One indication of this language change is probably Germany’s first ‘songwriting camp’, the ‘Songwriter Gipfel’ (i.e. songwriter summit) in the early 2000s. The event was held in the Peppermint Studios on the former Expo site in Hanover and organized by Jamaican expat Errol Rennalls to assist the artist Mousse T. in writing his first album following his two hit singles ‘Horny ‘98’ (Citation1998) and ‘Sex Bomb’ (Citation1999, with Tom Jones). It was only later referred to as a ‘songwriting camp’.

To date, songwriting camps have received little attention in academic research; there is only one doctoral dissertation studying songwriters’ insights, attitudes, and actions in the context of three Finish songwriting camps (Hiltunen Citation2021), one study comparing the organization of ‘copresence’ (Zhao and Elesh Citation2008) in collaborative songwriting in an online community with several thousand members and one physical songwriting camp (Schiemer, Schüßler, and Theel Citation2022), and another study on songwriting camps as sites for the (re-)production of practice-based knowledge (Tolstad Citation2023).

The research project follows a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz and Thornberg Citation2021) to develop a systematic, evidence-based understanding of the different forms, specifics, and dynamics of songwriting camps, based on in-depth interviews with songwriters and industry staff as well as ethnographic field observation in real-life songwriting camps and a research lab. The approach of this article is to systematically discuss aspects of creativity, collaboration, business, and copyright in commercial songwriting as presented in academic and journalistic literature and to utilize work-in-progress empirical findings from the underlying research project to interrogate how songwriting camps relate to commercial songwriting practices in popular music since the early twentieth century. This includes activity around Tin Pan Alley (approx. 1885–1930s), the Brill Building (approx. 1931–1965), Motown (approx. 1959–1972), Stock/Aitken/Waterman (approx. 1984–1993), and more contemporary songwriting businesses like Xenomania (since 1997) and Dr. Luke’s Prescription Songs (since 2009). We are currently focused on popular music traditions in the West, leaving aside other interesting phenomena in popular music culture and industry, such as K-Pop (Lee Citation2014), to narrow the scope of our investigation. The empirical data comprises 25 interviews with professional songwriters and camp organizers. However, as we are in the early stages of a multi-year research project studying how songwriting camps fit into the evolution of professional songwriting practice, this initial article focuses on establishing high-level observations from the data rather than quoting individuals directly.

Industrialized songwriting in Western pop music since the twentieth century

Collaboration between distinct roles, such as composers, lyricists (librettists), and performers, has long been an established feature of ‘classical music’. However, it was the changing socio-technological landscape of the early twentieth century, especially recorded music, that accelerated and facilitated popular music creation by teams of specialists. These changes fundamentally impacted songwriting and marked the rise of assembly-line types of music creation and production (Shepherd Citation2016; Tschmuck Citation2012). In this mode of working, songwriters, arrangers, engineers, producers, performers, and publishers are ‘vertically integrated’ close to each other so that the entire creative process, from writing and producing a song to pitching it to record companies, can take place in one location (Barber Citation2016, 68). Usually, the creative process, based on this division of labor, consisted of elaborating a lyrical or melodic idea into a song, which was subsequently performed by a star singer, arranged, recorded, and produced by a specialist team, and commercially exploited by an in-house publisher. With all the elements of a Fordist production process in place, products could be rapidly created.

By the early twentieth century, the gramophone had transformed the mass reception of music (Smudits Citation2002), and the Hollywood star system was quickly adopted to boost sales (Wall Citation2013). Due to increasingly commodified markets, musical material was in high demand. Some of the biggest hits of that time originated in New York’s Tin Pan Alley. The site thrived at the turn of the twentieth century, with creative duos of lyricists and composers like Jerome Kern, Ira Gershwin, and Cole Porter writing music based on popular formulas (Jasen Citation2015). Those musicians worked for publishing houses such as T.B. Harms, which John Seabrook (Citation2015, 68) describes as the ‘very first hit factory’. Equivalent sites also existed in other parts of the USA, such as Nashville’s Music Row, and throughout Europe, including London’s Denmark Street – the ‘British Tin Pan Alley’ (Seabrook Citation2015, 68; see also Wall Citation2013, 25–28). In line with older business models in (popular) music since the mass printing of sheet music, the publishers of this music initially earned their profits by selling scores, while authors were paid royalties. This type of music was shaped by a clear (AABA) form and formulaic approaches to melody and harmony. In his seminal 1941 essay, Theodor Adorno characterized the music as ‘pre-digested’. He criticized it for having manipulative power and that it would only exist to ‘reproduce the working power of people’ and to function as ‘social cement within societies’ (Adorno, Simpson, and Institut für Sozialforschung Citation1941, 305–311). But Tin Pan Alley was not only about predictable musical structures but also about industrialized structures, as Tim Wall points out:

The emphasis within the Tin Pan Alley discourse on the division of labour between professional songwriters, musicians and star singers is characteristic of the industrialised music industry […] The idea that music should (a) aim to entertain large audiences, (b) be judged by sales figures in lists of best-selling recordings, and (c) requires a polished presentation based upon practice and the skill of background professionals, has been the staple of the music business for the whole of the last century (Wall Citation2013, 28).

These uses of records are a vital source of income for the record industry, and the licensing and copyright arrangements involved draw attention to an important feature of cultural commodities: the special status of artistic labour. […] For most of the workers concerned with making records and the capital equipment of the recording industry the same relationship holds: they are wage labourers, paid for their time, without any economic interest in the product on which they’re working. But cultural products are also the products of artistic labour, and artistic services are rewarded with a cut of the final profits – royalties act as an incentive to musicians whose creative skills cannot easily be controlled by record companies (Frith Citation1978, 106).

After Tin Pan Alley, the next significant step in the industrialization of popular music songwriting and production followed in the 1960s with the Brill Building (1619 Broadway) and the lesser known, albeit similarly productive, Aldon Music (1650 Broadway) in Manhattan, New York (Barber Citation2016). Successful songwriting teams, usually composed of two persons, such as Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, were instrumental in the Brill Building era in creating hits recorded by artists like Elvis Presley, Ben E. King, and Perry Como. According to Sean Egan, the Brill Building – and similarly, Aldon Music – ‘centered around publishers’ offices on New York’s Broadway where young songwriters would sit in cubicles turning out songs which adhered to the short and catchy nature of traditional pop music but which acknowledged both the sonic and cultural overtones of the more hard-edged rock and roll’ (Egan Citation2004, 62). The collaborative nature of this scene, or its ‘friendly competition’ (Barber Citation2016, 67), is depicted even more clearly by Seabrook: ‘In the warren-like offices, publishers, writers, agents, managers, singers, and song pluggers formed hit-making’s vibrant and colorful subculture’ (Seabrook Citation2015, 68), which was the birthplace of dozens of hit songs, if not the defining sound of the early 1960s.

The notion of song factories soon inspired other record companies, such as Motown in Detroit, which took over from Broadway in the mid-1960s. Inspired by the line production of car manufacturer Ford, Motown founder Berry Gordy adopted this practice for record production by introducing dedicated ‘departments’ for songwriting, arrangement, engineering, regular quality control meetings, and publishing (Flory Citation2017). Motown’s considerable success resulted from a formulaic sound, achieved through specialized teams of songwriters, arrangers, engineers, and studio musicians, who formed creative and organizational clusters within a larger corporate structure (Flory Citation2017, 41–68). Motown songwriter Lamont Dozier described the songwriting team with Brian and Eddie Holland as a ‘factory-within-a-factory type of thing. That’s how we were able to get out so many things’ (Dozier in Egan Citation2004, 122). Production was largely organized around bringing together combinations of creative and administrative staff, most of whom did not know the artist or title of the song to which they were contributing (Flory Citation2017, 51). In the 1970s, Philadelphia Records pursued this industrial approach even more stringently through the creation of the ‘Philly Sound’, with professionals writing and producing ‘backing tracks’ independently of any specific artist (Wicke Citation2011, 82–85), capitalizing on the ‘songwriting factory’ label and associated practices.

In the decades that followed, songwriting teams paved the way for musical stars to conquer the global pop market. Drawing on the work of Sean Egan (Citation2004), Phil Harding (Citation2010, Citation2020), and John Seabrook (Citation2015), examples include: Stock/Aitken/Waterman (Kylie Minogue, Jason Donovan, Bananarama, Rick Astley); Cheiron Studios (Backstreet Boys, Boyzone, Britney Spears, Westlife); Xenomania (Girls Aloud, Sugababes, Gabriella Cilmi); RedZone Entertainment (Rihanna, Pink, Britney Spears); Prescription Songs (Katy Perry, Ke$ha, Doja Kat). The size of teams and the variety of roles seem to have increased. According to Seabrook, Prescription Songs, Dr. Luke’s (Łukasz Sebastian Gottwald) company,

consists of some fifty songwriters and producers, with Cheiron-like overlapping skills. At this stage, the writers were still dispersed in studios across Los Angeles […] but the plan was to create a physical factory. […] Dr. Luke describes his songwriting roster as ‘a combination of artists, producers, topliners, beat makers, melody people, vibe people, and just lyric people’ (Seabrook Citation2015, 236).

Similarly, and in keeping with the Motown tradition, one of Xenomania’s main staff songwriters described their work as a never-ending songwriting camp where different combinations of writers convene in different rooms of the residential facility that acts as their workspace. One possible explanation for the shift towards more specialized teams in songwriting is that it facilitates addressing global mainstream markets. In a quantitative study of number-one hits in the US Billboard charts between 1955 and 2009, Terry Pettijohn and Shujaat Ahmed (Pettijohn and Ahmed Citation2010) find evidence of collaborative writing in 50% of hit songs. Correspondingly, Joe Bennett (Citation2011) notes that in 2010, 80% of the UK single chart hits were co-written. Particularly successful in the recent past, according to a Billboard study by David Tough (Citation2017), has been cross-genre collaboration, where artists, songwriters, and producers contribute different stylistic features to a track. In our empirical study on songwriting camps, one leading professional songwriter concurred that the credits of modern productions often list more than a handful of songwriters. The songwriter explained that dividing the work among highly specialized individuals was beneficial because the increased quality usually leads to higher income and therefore compensates for the smaller percentage of royalties each professional receives (see also Bennett Citation2014, 129).

Collaboration in songwriting through the lens of creativity research

The songwriting literature highlights different sides of the songwriting profession. On the one hand, it is presented as an ordinary profession – potentially rewarding but characterized by precarious conditions (de Laat Citation2015; Jones Citation2005; Long and Barber Citation2015). On the other hand, some research seeks to explore the creative aspects of the songwriting profession (Barber Citation2020; McIntyre Citation2008; Thompson Citation2019). A comparatively large amount of literature emphasizes creativity in record production, often illustrated with seminal recordings of ‘classics’ by The Beatles, The Beach Boys, Phil Spector, or Trent Reznor (Cunningham Citation1998; Moorefield Citation2010). A direct comparison shows that the creativity of songwriters has been addressed much less, and what little exists tends to distort the reality of songwriting. As Mike Jones (Citation2005) and Paul Long and Simon Barber (Long and Barber Citation2017) note, retrospective biographical interviews with respected songwriters, such as those collected by journalist Paul Zollo (Citation2003), can tend to reproduce romantic notions of songwriting by presenting it as an innate gift and emphasizing the occurrence of inexplicable inspiration. This account is perhaps further skewed by Zollo’s choice of songwriters interviewed, as only two of the 62 interviews were conducted with songwriting teams (Bennett Citation2013, 147), who had a significant impact on the history of popular music and hit factories in recent decades.

Looking at the current state of creativity research, the popularity and success of collaborative songwriting are hardly surprising. Susan Kerrigan (Citation2013) revised Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s (Citation2015) influential ‘systems model of creativity’ by replacing the individual with the (collective) agent to account for creativity in groups. The value of collaboration is stressed even further in Keith Sawyer and Stacy DeZutter’s (Sawyer and DeZutter Citation2009) framework of ‘distributed creativity’, which places interaction at the heart of creative processes. A key concept is ‘collaborative emergence’, the unpredictable occurrence of ideas and responses from individuals in a group, which fosters interactive processes and subsequent outcomes in artistic disciplines. Emergence is more likely to occur when: the activity gives a result not anticipated or directed toward a specific, predefined goal; each individual takes actions building on the prior actions of other collaborators; all participants contribute equally (Sawyer and DeZutter Citation2009, 82–83). Important for the context of songwriting camps and other collaborative forms of songwriting and music production is the constitution of the network, where a greater degree of heterogeneity in terms of expertise, skills, and personality traits contributes to a higher degree of ‘contingency’ that fosters emergence (Nasta, Pirolo, and Wikström Citation2016). Ultimately, ‘the whole is greater than the sum of the parts’ (Sawyer Citation2003, 185). Our interviews largely support these claims. Songwriting camp organizers and participating creatives confirmed that forming diverse groups with members from different specializations and roles, experience levels, age groups, and cultural and musical backgrounds was critical to the success of time-limited and focused songwriting sessions. It fostered rapid implementation and development of ideas and combined the contemporary approaches of emerging creatives with the experience of seasoned writers. The interviewees commented less on diversity concerning race, gender, or social class, which might suggest that they perceived musical factors as having a greater impact on songwriting success. The right combination of personalities and skills was considered essential.

Bennett (Citation2011, Citation2014) has repeatedly stressed the importance of collaboration for commercially successful songwriting in popular music, proposing the ‘stimulus evaluation model’. Bennett describes it as continuous quality control of those involved in the creative process, thus addressing the relevance of stimuli by peers in creative processes.

During the evaluation stage of a stimulus it can be processed in four ways by the writing team; approval, veto, negotiation or adaptation. Approval allows the idea to take its place in the song, a process that usually requires consensus from the songwriting team. A co-writer may challenge another writer’s stimulus, leading to veto (rejecting the stimulus), negotiation (arguing a case for accepting the stimulus) or adaptation (changing the stimulus until vetoed or approved). A stimulus is the beginning of a creative idea’s pathway through the songwriting team’s filter; consensus represents a successful end to its journey. I contend that six (non-linear and interacting) processes are at play in a cowriting environment – stimulus, approval, adaptation, negotiation, veto and consensus (Bennett Citation2013, 155).

According to Bennett, collaboration provides quality assurance that leads to higher success rates of collaboratively written songs – a notion supported by other studies (Pettijohn and Ahmed Citation2010; Tough Citation2017). Or as recognized songwriter Jerry Leiber puts it, ‘According to Mike [Stoller], we’re always falling out. We’re in a state of falling out. It’s been the longest argument [61 years of collaboration] on record in the music business’ (Leiber in Egan Citation2004, 40). The interviews for our research suggest that conflict in songwriting camps is generally avoided by being clear about the terms of the working arrangement from the outset and by dividing groups considerately, but that differing views, ideas, and expertise are seen as essential to writing success. Furthermore, the professionals emphasized the importance of editing, which accords with Bennett’s observations. In their experience, it is common for one person to devise the creative idea and sketch out the song in a flow state (Csikszentmihalyi Citation2009), which they viewed as a collaborative effort because the less active individuals were understood to have helped facilitate the idea generation. Knowing when to contribute and when not to interfere was considered a crucial skill for a songwriter. One songwriter also pointed out that roles are often shared, with younger creatives developing ideas and experienced songwriters serving as editors.

The self-determination theory by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan (Deci and Ryan Citation2008) is another strand of research rarely considered in the context of collaborative creativity. While this theory is primarily concerned with aspects of human motivation, development, and health, its key concepts, like perceived competence and autonomy, are fundamentally linked to social inclusion, highlighting the importance of broader social factors, even at the level of individual creatives. The songwriters we interviewed expressed a strong motivation to attend camps, and some, especially those attending non-commercial writing camps, were willing to pay fees and travel expenses themselves. Several songwriters stressed the importance of bonding with other creatives and belonging to a professional network. At songwriting camps, social activities such as meals, drinks, cooking classes, and wine tastings play an important role in allowing creatives to form relationships. This ‘social glue’, as one interviewee put it, was among the main motivations for participation. Moreover, social bonding was perceived as crucial for creativity to flourish and thus essential to the success of writing camps, a perspective shared by camp organizers.

An expanded understanding of networks also plays a central role in related studies on the relevance of collaborative creativity and social networks in popular culture and business. Social networks are widely highlighted and discussed (Bell Citation2018; Miettinen Citation2013; Watson Citation2011) against the background of recent technological developments in the field of communication and organizational management (Sternberg and Lubart Citation2002) or the distribution and economic exploitation of music. Peter Tschmuck (Citation2012) refers to connections between network formation, technological developments, and paradigm shifts in the music industry, which he describes as ‘revolutions’. It is evident that frameworks like actor-network theory (Latour Citation2007) are also relevant for collaborative music production in that they take not only humans into account but also technologies and (big) data. Music (production) technologies are not passive agents subservient to human actors (Strachan Citation2017) but significantly determine creative actions by introducing emergence and contingency, much like collaboration between human actors (Sawyer and DeZutter Citation2009). In our interviews, studios were described as important for recording demo ideas and fully-produced tracks. Yet most of the work was carried out with mobile setups to develop ideas, and professional studios were mainly used in the last phase to improve production quality. Much more important were traditional writing tools such as piano, keyboard, and guitar, as well as digital audio workstations, for developing and sequencing ideas and sounds. Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms have the potential to support or even completely replace human involvement in the production process (Drott Citation2021). However, songwriters reported that publishers were less interested in replacing human songwriters than they were in providing them with tools to enhance quality or increase writing speed. This position remains consistent with the notion of song factories as a model of efficiency in professional songwriting.

Despite the extensive literature stressing the benefits of collaboration for creative processes, some studies highlight its potentially obstructive effects. In their evaluation of collaborative songwriting, Pettijohn and Ahmed (Citation2010) discuss the concept of ‘social loafing’ as the ‘likelihood of individuals contributing less when working on a task as part of a group than when working on a task alone’. The authors point out that social loafing ‘generally increases with group size and decreases with task importance, potential for evaluation, uniqueness of individual contributions, and complexity of task’ (Pettijohn and Ahmed Citation2010, 2). Social loafing seems related to Csikszentmihalyi’s (Citation2009) ‘flow states’, which require the right level of personal challenge, meaningfulness, and contribution, and thus must accord with the composition and working arrangements of the group for collaboration to be superior to individual work (Sawyer Citation2017, 29–52). With regard to large group sizes, Bennett (Citation2014, 130) found that groups not extending four or five professionals are ideal in professional songwriting practice. This finding is interesting insofar as many contemporary hits include significantly more contributors, regardless of whether they result from songwriting camps or other collaborative structures. However, this does not preclude a division of labor in the various stages of the production process, where songs written by a handful of songwriters are subsequently processed and optimized by engineers, editors, programmers, producers, and other creatives, who rarely meet directly to collaborate on the project in question, as they are likely to be based in different geographical locations (Herbst and Albrecht Citation2018; Thorley Citation2019). The findings of our research lie somewhere in the middle. Without exception, all interviewees saw a group size of three as ideal in the songwriting process because it ensured that all essential roles of producer, songwriter, and topliner were represented. Because the majority of collaboration in songwriting camps is based on an equal financial split, songwriters were less concerned about sharing royalties, which is at the core of social loafing (Pettijohn and Ahmed Citation2010), but rather felt that the creative process did not benefit from too many collaborators. Instead of working with multiple creatives on one song, they would rather work on new songs in rotating groups, believing this would foster inspiration.

A further factor that needs to be considered is the level of structure. By providing clear guidance and role expectations to each individual, structures can facilitate creative emergence (Sawyer and DeZutter Citation2009) and reduce social loafing, potentially freeing up resources and energy to produce novelty (Rosso Citation2014, 555). This view is supported by our interviews, which indicate that individuals are commonly invited to participate in songwriting camps for their particular skills. However, too strict structures may bear the risk of limiting innovation (Sawyer Citation2012, 235; Schiemer, Schüßler, and Theel Citation2022). In her exploratory work on Finnish songwriting camps, Riikka Hiltunen (Citation2021, 148) could not conclude any unequivocal benefits or limitations from the strict structures set by camp convenors but instead highlighted the scripted nature of these collaborative arrangements and their threats to creativity. On reference songs provided to the songwriters as part of their briefings, Hiltunen notes:

Listening to reference songs helps songwriters to create something similar, but it may also make it more difficult for them to produce something different, original and novel. Thus, the past constrains creative and future-oriented thinking among songwriters in various ways: on the domain level as the anticipation of futures that are similar to the past, and on the individual level as overly deep knowledge, past experiences, and excessively routinised or inadequate skills. (Hiltunen Citation2021, 156–157)

Collaborating roles and skill sets in popular music songwriting

The previous overview of industrialized modes of songwriting and thinking on creativity has demonstrated the benefits of collaboration. These advantages are not due solely to the fact that creatives collaborate but, more importantly, to the fact that they have different roles and associated skills (Nasta, Pirolo, and Wikström Citation2016). This division of roles can be traced far back in history, especially the separation of musical composition and lyrics, as shown by teams like Gerry Goffin (lyrics) and Carole King (music); Brian Holland (music), Lamont Dozier (music and lyrics), and Eddie Holland (lyrics); and Nicky Chinn (lyrics) and Mike Chapman (music). Other forms of collaboration include shared lyrical and musical contributions (e.g. Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry); songwriting, production, and A&R (e.g. Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange and Clive Calder); or songwriting/production with A&R/publicity (e.g. Mike Stock, Matt Aitken, Pete Waterman).

Structural and economic changes in the recording industry and technological advances have led to different models of popular music creation (Bell Citation2018; Leyshon Citation2009; Strachan Citation2017). On the one hand, affordable and powerful digital music production technologies have enabled solo artists and groups with small budgets to write, engineer, and produce their music to a professional standard (Walzer Citation2017) without the need for a record deal, which was inevitable before these innovations (Marshall Citation2014). On the other hand, creatives have specialized in order to take advantage of working with professionals with different skill sets. As our data suggests, bringing different roles and skills together is the main model on which contemporary songwriting camps are based, building on the success of earlier models of industrialized popular music production, such as Brill Building, Motown, PWL (Pete Waterman Limited), and Xenomania.

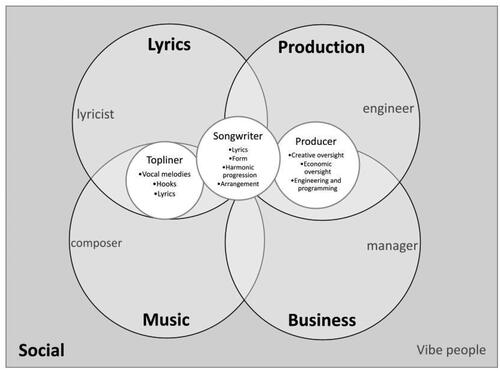

Whether united in one person or split between different creatives, contemporary popular music production relies on various roles that are also found in songwriting camps (). Topliners create vocal melodies, hooks, and lyrics in the continued tradition of lyricists. Often, topliners are singers able to record high-quality demo vocals but sometimes also act as specialized vocal producers. The songwriter role is not clearly defined because it can include both lyrics and music, but according to our data, songwriters and topliners are usually separate and collaborate. Concerning the musical composition, songwriters write the structural essence of the song, including its form, harmonic progression, melodies, and sometimes the arrangement. The producer role is similarly varied (Burgess Citation2013) but essentially involves the overall creative direction and often economic oversight. Producers may be heavily involved in creating the musical material (sometimes as beatmakers or programmers) and executing technical tasks, or they may oversee the creative process. In many electronic genres, producers have replaced the traditional songwriter because the essence of an electronic song lies in the sound and beats rather than conventional musical qualities such as harmony and structure (Brett Citation2021). Engineers (sometimes called ‘trackers’) are responsible for technical implementation (Zak Citation2009), sometimes specializing in specific phases of production, such as recording, editing, mixing, and mastering. In songwriting camps, engineering tasks seem to fall under the purview of producers. Songwriters and organizers recognize that producers are essential in capturing and presenting creative ideas – a good tune needs a correspondingly high-quality production, and elements of sound and rhythm are compositional aspects of a pop song that are necessary for presentational reasons, even before it enters the final production stage with the recording artist (see also Bennett Citation2014, 224–225).

The roles discussed are somewhat blurry, as there is considerable overlap. It appears the move towards specialization is based less on replicating traditional roles and more on optimizing the process to increase the likelihood of success. According to Phil Harding, a successful producer of dance music and boy bands, ‘it takes a number of specific skill sets to achieve a result that is worthy of chart success. […] My typical creative team would comprise of: A team-leader, a keyboard player/programmer, a rhythm programmer and a lyricist/vocalist (“top-liner”)’ (Harding Citation2020, 71). Programmers do not fall neatly into a traditional role, as their work encompasses various aspects, including songwriting, producing, and engineering, many of which contain elements of performance expertise. Our interviews suggest that songwriting camps may differ slightly from comprehensive production houses such as PWL and the process Harding describes. All songwriters interviewed mentioned that songwriting camps typically require only three specialized roles: topliner, songwriter, and producer. However, it is important to note that teams working in songwriting camps usually prioritize the writing of the song over elaborate production techniques, while more specialists may be involved in the actual production with the artist.

There are also indications in the literature that roles and responsibilities are becoming less fixed and more fluid. In their recent research on co-production, Robert Wilsmore and Christopher Johnson (Wilsmore and Johnson Citation2022) consider artistic self-knowledge not definite and likely to change during the working process. In extreme cases, the individual is absorbed into the group and becomes invisible. Wilsmore and Johnson draw on the notion of ‘scenius’ as defined by composer/producer Brian Eno: ‘Scenius is the intelligence of a whole operation or group of people. […] Let’s forget the idea of genius for a little while, let’s think about the whole ecology of ideas that give rise to good new thoughts and good new work’ (Eno Citation2009). However, the unitary nature of scenius is subject to practical limitations because once royalties are negotiated and divided up on a percentage basis, the shares of those involved ultimately become visible again. The changing modes of collaboration that exist in some songwriting and production environments challenge traditional black-and-white distinctions when it comes to formal credits and associated royalties, as will be discussed in the next section. Nevertheless, this kind of flexibility is less common in commercial songwriting camps, where creatives remain in their roles. It is mainly in non-commercial songwriting camps (typically described as ‘songwriting retreats’) where participants perform diverse tasks in order to explore different roles and develop artistically.

The preceding deliberations can easily give the impression that songwriting camps and other more industry-led forms of music creation are a parallel system to artists writing their own music. But a significant proportion of those artists appearing ‘authentic’ by writing songs themselves receive help from professional songwriters – in addition to engineers and producers, whose contribution is less stigmatized, as they have always been required to capture a song on record (Burgess Citation2014). Even artists from seemingly ‘authentic’ genres, such as singer/songwriter and rock, seek assistance to varying degrees. Bennett (Citation2011, Citation2014) refers to this collaboration, mutually benefitting artists and songwriters, as the ‘Svengali’ model. Songwriters can expect that the song will be performed by the popular artist they have collaborated with and not sold by the publishing company to an unknown artist, which increases their chance of receiving substantial royalty payments. Artists benefit from feeling more emotionally connected in the greater sense of ‘ownership’, which translates into a more compelling and authentic performance and impression on the audience (Bennett Citation2014, 246–247). Also, the songwriter’s professional experience will likely improve the song’s quality, a prerequisite to commercial success (Bennett Citation2011; Long and Barber Citation2015). However, ‘artists still have their authenticity to sell, of course, and thus have a vested interest in publicly diminishing the role of the Other’ (Bennett Citation2014, 25). For this reason, the general public is presumably unaware of the typically large group of songwriters, producers, engineers, and other supporting roles behind the scenes. Working relationships between artists and songwriters range from multi-year partnerships (see Long and Barber Citation2015) to commissioning agreements based on ‘pitch lists’, where the songwriters and artists never meet.

Recording artists who do not write their own songs often use ‘pitch lists’ that are exclusively distributed within industry circles. These lists, which come to the songwriter via the artist’s management or record producer or from the songwriter’s music publisher, try to describe the type of song the artist is looking to record. In response, the songwriter is invited to interpret that request and offer the artist a song that fits the specification (Anderton, Dubber, and James Citation2013, 51).

Pitch lists serve several purposes, such as illustrating the desired aesthetic and production aspects, fostering specific star personas, or motivating market-specific outcomes. The interviews with writers attending commercial songwriting camps confirmed that pitch lists and briefs are common in the absence of recording artists. Writing songs with artists present is also common. In this case, songwriters typically create concepts for the songs that relate to topics or experiences that the artist has expressed an emotional connection with. Being able to create an open dialogue with an artist and forge a relationship in a short space of time is therefore an important part of how the songwriter is able to deliver results that appeal to the artist’s sensibilities.

Business and legal matters surrounding collaborative songwriting

A commercially driven industry such as pop(ular) music has established working practices and realities significantly influenced by business and legal concerns. The previous considerations about collaboration addressed its benefits for both creativity and the commercial success of the resulting product. For songwriters, collaboration is beneficial as a way of dealing with economic uncertainties characterizing their profession (Jones Citation2005). A continued trend over the last decades has been declining budgets in the recording industry (Leyshon et al. Citation2005), resulting in less investment in artists and, thus, fewer opportunities for songwriters (de Laat Citation2015, 234). Moreover, songwriters must share their royalties with producers, about which the literature is divided. Harding (Citation2020, 54) notes a shift from an equal split between songwriters and producers from the 1950s to the 1970s to an 80/20 split in favor of songwriters from the 1990s onwards. In contrast, Kim de Laat (Citation2015, 233–234) documents an ‘unwelcome jurisdictional encroachment’ through the producer’s increasingly important role with higher shares of song copyright (plus a production fee), as well as popular artists claiming songwriting credits without sufficient contributions due to their position of power.

One result of deteriorating economic conditions in the recording industry is what de Laat (Citation2015) calls ‘post-bureaucratic’ work arrangements. Fixed, local, and hierarchical company structures – for instance, a record company owning studios and employing engineers and producers, as was the case with Beatles-era EMI and their Abbey Road Studios – have gradually been replaced by temporary and more egalitarian forms of organization that allow for a ‘more efficient, flexible, and cost-effective method of production’ (de Laat Citation2015, 226). These claims echo Hajdu’s (Citation2015) critique of Seabrook (Citation2015), discussed at the outset, which employed a post-industrial framework to undermine Seabrook’s adherence to the factory model to explain the creation of contemporary pop music. Indeed, songwriting camps are a model of production that is efficient, flexible, and cost-effective. It is this fluidity, as well as financial competition with producers and artists, that defines a collegial ethos amongst professional songwriters when it comes to royalty splits. Contrary to the expression ‘write a word, get a third’ (Bennett Citation2014; de Laat Citation2015), songwriters usually share royalties evenly when participating in camps, irrespective of the quantity or quality of contributions. Equal financial splits counter financial uncertainties and ensure participation in future projects, and so are vital agreements among songwriters. Other reasons for this egalitarian practice include: the working atmosphere being more productive without the need to discuss legal arrangements; diminished pressure to be equally creative on every project; selecting the best ideas without individual royalty interests; and professional courtesy (Bennett Citation2014; de Laat Citation2015; Jones Citation2005). As Bennett (Citation2014, 129) points out, songwriters are willing to ‘sacrifice a large proportion of their ownership and earnings’ by collaborating with other professionals because they expect the product’s higher quality to pay off economically and the experience of the creative process to be more enjoyable – two reasons that our interviewees also emphasized. Moreover, collaboration with other participants is deemed worthwhile, even if it comes at the expense of royalties, as the outcome of the songwriting process can result in other benefits, such as career development and networking. As a result, songwriters attending camps are equally motivated and compelled to collaborate with producers, programmers, performers, and engineers.

Copyright law affects the practice of commercial music creation in a number of ways, some of which are relevant to collaborative creativity in songwriting camps. Importantly, royalty regulations vary between countries (Döhl Citation2016; Halloran Citation2017; Hull, Hutchison, and Strasser Citation2011; Osborne Citation2022). While copyright law in the Anglophone world (e.g. USA and UK) only distinguishes between composition (music and lyrics) and sound recording (with performance as a secondary addition), copyright law in most Central European countries differentiates between music, lyrics, and sound recording. The fundamental difference between the legal view and the associated business models lies in the understanding of authorship: while copyright systems make music tradable – the Anglophone ‘common law’ system is a prime example – this right cannot be sold in many Central European ‘civil law’ systems because it is inextricably linked to the creator (Osborne Citation2017b, 575, Citation2022, 6–7). This difference may be significant in the context of songwriting camps in that, according to our interviews, such gatherings typically bring together creatives from different countries. It is also important to note who decides how the songs written at the camps are utilized and exploited. In most cases, the organizer – often a publisher – takes the lead in pitching songs to be recorded and commercialized, with the songwriters (and producers involved in the writing process) receiving their share for their compositional work. While the organizing party typically has the first look at the material produced in the camps, our interviewees reported that songwriters could pitch songs independently to record companies and artists, subject to agreements and royalty shares with their fellow writers and the songwriting camp organizer/publisher. This agency in the exploitation of songs makes songwriters artistic laborers with an invested interest in the music they write, rather than craft laborers who would be compensated with a one-time fee. Generally, the collaboration between creatives and ‘the industry’ was described as cooperative and supportive, with songwriters benefiting from industry feedback on their songs and growth of their professional networks. However, it should also be noted that in the UK, there seems to be an inequality regarding professional standing. While aspiring songwriters typically have to pay a participation fee and cover their travel expenses, accomplished songwriters are usually invited to these events, with costs covered by the organizer or publisher. Nevertheless, the emerging songwriters interviewed saw these costs as reasonable business expenses because camps led to new contacts and opportunities to be involved in big-selling hits. Furthermore, they had access to high-end music production resources and staff, which allowed for the creation of professionally produced songs that songwriters outside of these camps would otherwise have to pay for themselves. Songwriting camps were therefore considered important for career and skill development and a promising format for writing and pitching commercially viable songs with clearly defined terms and royalty agreements on top of national copyright regulations.

Many Western nations distinguish between mechanical and performance licenses (see Osborne Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The consequences for a session musician are that royalties are paid for the performance, but access to the more lucrative mechanical reproduction rights is typically restricted (Osborne Citation2017b). Even though they shape the musical material as performers through interpretation or even developing parts of the song, such as melodies, riffs, or characteristic rhythms, session musicians are usually only credited for their performances and not their musical contribution (see Herbst and Albrecht Citation2018) and are thus limited to performance rights, or even bought out with a one-off payment. Other roles, such as rhythm or keyboard programmers (Harding Citation2020), involve songwriting activities and are similarly difficult to attribute to a specific rights organization, as are producers that overlap significantly with the songwriter profession. According to our interviews, the creatives who participated in songwriting camps were keen to produce high-quality recordings containing their own background performances in the hope that stems from these sessions would be included in the released record. This would enable them to benefit from performance royalties in addition to their (more lucrative) mechanical royalties. This strategy is similar to that Richard James Burgess (Citation2008) describes for increasing producers’ income through recognition as performers.

Further complicating factors concerning copyright include sampling rights (Döhl Citation2016, Citation2022), AI-based music creation (Drott Citation2021), and transparent documentation of the writing and production process through blockchain technology (O’Dair Citation2019). These all raise fundamentally new questions about copyright and performance protection that will shape the economic reality and collaborative working practices of songwriters and other music professionals in the future. Legal arrangements become exponentially more complex in projects involving large numbers of specialists not easily fitting into traditional copyright categories and where individual contributions cannot be identified or quantified (Wilsmore and Johnson Citation2022). In situations with many collaborators, such as in songwriting camps, the post-bureaucratic solution of equal shares seems to be the most pragmatic and perhaps fairest way to reward individual contributions. To date, little is known about ongoing creative processes, dynamics, and legal practices in songwriting camps and how economic and creative aspects influence each other. But there is still more to be considered, particularly the interests of stakeholders, such as record labels, publishing companies, aggregators like music streaming platforms, and other convenors of songwriting camps. These economic variables are easily overlooked in the study of creativity, songwriting, and record production, even though they fundamentally determine the processes and outcomes.

Conclusion

Songwriting and music production have always developed in parallel with society, influenced by fluid socio-economic practices and technological advancements. As a commercially oriented creative industry, popular music has, over time, adopted and explored capitalistic practices such as assembly line-like structures to pursue more efficient and effective production. This industrialized mode of operation is aptly depicted by Seabrook (Citation2015) in his journalistic take on ‘song machines’ and ‘hit factories’, covering practices from early Tin Pan Alley to contemporary pop productions by stars such as Ke$ha, Katy Perry, and Rihanna. The most popular pop music of today, David Hajdu notes in his review of Seabrook’s book, appears

more regimented and mechanized than the means by which any music had been made in the past. Producers generate instrumental tracks by sample-mining and synthesis, using software and keyboard plug-ins; teams of ‘topliners’ add melodic hooks and lyric ideas onto the tracks; and the results are cut and pasted, Auto-Tuned and processed, then digitally tested with software that compares the sonic patterns of a new song with those of past hits. (Hajdu Citation2015)

Regimentation is the main feature of industrial production, Hajdu argues, resulting from rigidly systematic methods that tend to create a uniform aesthetic. For Hajdu, the worst sin of industrialization is that mechanization can be dehumanizing, as one might expect in modern pop music, where digital audio workstations, samplers, and synthetic instruments replace performers. Yet, Hajdu notes, humans are still responsible for using the software, making creative decisions, and experiencing human emotions in activities that involve ‘invention, collaboration, rivalry, triumph, and disappointment’. Hajdu (Citation2015) therefore concludes that music production has evolved into a post-industrial space in which the song factories have closed, and where it is no longer adequate to explain songwriters’ creative work as the product of an assembly line process. Popular music and production are now defined by information-era techniques like ‘mining the vast digital repository of recordings of the past, or by emulating or referencing them through synthesis, and then manipulating them and mashing them up’. Methods enabled by digitization, such as retrieving and processing, have replaced dovetailing and stamping for uniformity in the industrial machine model of mass production in popular music, culture, and society.

We concur with Hajdu (Citation2015) that the (Western) world is transitioning from an economy based on material objects to an economy of ideas. The industrial age as we know it is giving way to an economy based on new knowledge, i.e. a creative economy (Powell and Snellman Citation2004), strongly shaped by post-digitality and environmental media cultures (Hörl Citation2018). However, we would argue that Hajdu’s view that digitally-powered creativity in the post-industrial age has replaced industrial structures and processes overlooks the legacy and continuing influence of the historical working routines of successful music organizations such as Motown, Philadelphia Records, and Stock/Aitken/Waterman. These routines can still be found in current popular music songwriting and production practices, as our historical review and interviews with professionals involved in songwriting camps suggest. We therefore contend that while the tools and processes of contemporary commercial songwriting have certainly evolved, they owe more to the past than is perhaps yet acknowledged. We propose that songwriting camps are part of the current state of the art in terms of song production, alongside others such as Big Data and AI. They lean on the past but have been transformed in some ways by digitalization, combining traditional writing of musical structures and lyrics with production, rhythm programming, arranging, and sequencing in digital audio workstations. Importantly, however, although songwriting practices are supported by digital technology, the core of the creative process – interaction between creatives in purposeful structures and environments based on social relationships and human emotion – has changed little. In other words, contemporary songwriting, as practiced in professional camps, has adopted a digital version of the song process, where creative human activities are assisted and augmented by computer and electronic technologies but not replaced by them. Songwriting camps are a microcosm in which many of the same tensions, strategies, goals, and relationships can be observed as in past structures, from the writing cubicles of the Brill Building to the modern writing studio. Songwriting camps draw on features of historical examples of songwriting practice: strategic, time-limited collaboration, clearly delineated roles, encouragement of friendly competition among writers, and group evaluation.

In the world of the professional songwriter, creating songs that are recorded and made available as musical products remains the core activity; however, there are a number of ways in which value is derived from the creative act. Creative value could be determined in traditional terms (record sales, live performance, merchandise, ‘360 deals’), or through the ways in which these spaces of collaborative creativity facilitate career and skill development through networking, forging friendships, gaining industry contacts, and generating recurring income through royalties. In this sense, a post-industrial mode or way of organizing creative work, like songwriting camps, with specialists working in constantly changing teams, may prove to be a valuable framework for understanding contemporary popular music production, as long as the strict structures and economic arrangements do not stifle creativity. Songwriting camps are on a trajectory of gradual development and evolution in a knowledge and information-based creative industry, which is still based on its human fundament, especially when it comes to creativity and collaboration, which remain the pillars of the recording industry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This study is predominantly a re-analysis of existing data, which are openly available at locations cited in the References section of this article. Interview data will be available on the project website.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Adorno, T., and G. Simpson, Institut für Sozialforschung. 1941. “On Popular Music.” Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 9 (1): 17–48. https://doi.org/10.5840/zfs1941913.

- Anderton, C., A. Dubber, and M. James. 2013. Understanding the Music Industries. London: SAGE.

- Banks, M. 2010. “Craft Labour and Creative Industries.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 16 (3): 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630903055885.

- Barber, S. 2016. “The Brill Building and the Creative Labour of the Professional Songwriter.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Singer-Songwriter, edited by K. Williams and J. Williams, 67–77. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Barber, S. 2020. “Songwriting in the Studio.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Music Production, edited by S. Zagorski-Thomas and A. Bourbon, 189–204. London: Bloomsbury.

- Barber, S., and B. O’Connor. 2011. “Sodajerker.” Sodajerker. https://www.sodajerker.com

- Barger Elliott, M. (Director). 2016. “The Last Songwriter.” https://lastsongwriter.com.

- Bell, A. P. 2018. Dawn of the DAW: The Studio as Musical Instrument. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Bennett, J. 2011. “Collaborative Songwriting: The Ontology of Negotiated Creativity in Popular Music Studio Practice.” Journal on the Art of Record Production 5 https://www.arpjournal.com/asarpwp/collaborative-songwriting-%E2%80%93-the-ontology-of-negotiated-creativity-in-popular-music-studio-practice.

- Bennett, J. 2013. “Constraint, Collaboration and Creativity in Popular Songwriting Teams.” In The Act of Musical Composition, edited by D. Collins. Farnham: Ashgate, 139–169.

- Bennett, J. 2014. “Constraint, Creativity, Copyright and Collaboration in Popular Songwriting Teams.” PhD thesis, University of Surrey.

- Brett, T. 2021. The Creative Electronic Music Producer. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Burgess, R. J. 2008. “Producer Compensation: Challenges and Options in the New Music Business.” Journal on the Art of Record Production 3. https://www.arpjournal.com/asarpwp/producer-compensation-challenges-and-options-in-the-new-music-business.

- Burgess, R. J. 2013. The Art of Music Production: The Theory and Practice. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Burgess, R. J. 2014. The History of Music Production. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Chambers, G. (Director). 2011. “Secrets of the Pop Song.” BBC.

- Charmaz, K., and R. Thornberg. 2021. “The Pursuit of Quality in Grounded Theory.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357.

- Chusy. (Director). 2018. “It All Begins with a Song.” Planafilms. https://itallbeginswithasong.com.

- Comentale, E. 2013. Sweet Air: Modernism, Regionalism, and American Popular Song. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 2009. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 2015. The Systems Model of Creativity: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Cham: Springer.

- Cunningham, M. 1998. Good Vibrations: A History of Record Production. Chessington: Sanctuary.

- de Laat, K. 2015. “Write a Word, Get a Third.” Work and Occupations 42 (2): 225–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888414562073.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2008. “Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health.” Canadian Psychology 49 (3): 182–185.

- Döhl, F. 2016. Mashup in der Musik: Fremdreferenzielles Komponieren, Sound Sampling und Urheberrecht. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Döhl, F. 2022. Zwischen Pastiche und Zitat: Die Urheberrechtsreform 2021 und ihre Konsequenzen für die künstlerische Kreativität. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Drott, E. 2021. “Copyright, Compensation, and Commons in the Music AI Industry.” Creative Industries Journal 14 (2): 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2020.1839702.

- Egan, S. 2004. The Guys Who Wrote ‘em: Songwriting Geniuses of Rock and Pop. London: Askill.

- Eno, B. 2009. “Brian Eno Speaking at the Sydney Luminous Festival.” Synthtopia. https://www.synthtopia.com/content/2009/07/09/brian-eno-on-genius-and-scenius.

- Fletcher, L., and R. Lobato. 2013. “Living and Labouring as a Music Writer.” Cultural Studies Review 19 (1): 155–176. https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v19i1.2588.

- Flory, A. 2017. I Hear a Symphony: Motown and Crossover R&B. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Frith, S. 1978. The Sociology of Rock. London: Constable.

- Frith, S., and S. Zagorski-Thomas. 2012. The Art of Record Production: An Introductory Reader for a New Academic Field. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Gill, R., and A. Pratt. 2008. “In the Social Factory? Immaterial Labour, Precariousness and Cultural Work.” Theory, Culture & Society 25 (7-8): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276408097794.

- Hajdu, D. 2015. “It’s an Old Trope, but How Well Does the Factory Model Explain Pop Music?” The Nation, October 29, 2015. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/its-an-old-trope-but-how-well-does-the-factory-model-explain-pop-music.

- Halloran, M. E. (Ed.). 2017. The Musician’s Business & Legal Guide. New York: Routledge.

- Harding, P. 2010. PWL from the Factory Floor. London: Cherry Red.

- Harding, P. 2020. Pop Music Production: Manufactured Pop and Boybands of the 1990s. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Herbst, J. P., and T. Albrecht. 2018. “The Work Realities of Professional Studio Musicians in the German Popular Music Recording Industry: Careers, Practices and Economic Situations.” IASPM Journal 8 (2): 18–37.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., and S. Baker. 2013. Creative Labour: Media Work in Three Cultural Industries. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hiltunen, R. 2021. “Foresightfulness in the Creation of Pop Music: Songwriters’ Insights, Attitudes and Actions.” PhD thesis, University of Helsinki.

- Hirway, H. (Director). 2020. “Song Exploder.” Netflix.

- Hodges, C. 2010. “Worth Repeating: A Documentary on Songwriting.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpJqY7XILjU.

- Hörl, E. 2018. “The Environmentalitarian Situation: Reflections on the Becoming-Environmental of Thinking, Power, and Capital.” Cultural Politics 14 (2): 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1215/17432197-6609046.

- Hull, G. P., T. W. Hutchison, and R. Strasser. 2011. The Music Business and Recording Industry: Delivering Music in the 21st Century. New York: Routledge.

- Jasen, D. A. 2015. Tin Pan Alley: An Encyclopedia of the Golden Age of American Song. New York: Routledge.

- Jones, M. 2005. “Writing for Your Supper: Creative Work and the Contexts of Popular Songwriting.” In Words and Music, edited by J. Williamson, 219–250. Liverpool: Liverpool UP.

- Jones, T., and T. Mousse. 1999. Sex Bomb. Gut.

- Kerrigan, S. 2013. “Accommodating Creative Documentary Practice within a Revised Systems Model of Creativity.” Journal of Media Practice 14 (2): 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmpr.14.2.111_1.

- Latour, B. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Leyshon, A. 2009. “The Software Slump?: Digital Music, the Democratisation of Technology, and the Decline of the Recording Studio Sector within the Musical Economy.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41 (6): 1309–1331. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40352.

- Leyshon, A., P. Webb, S. French, N. Thrift, and L. Crewe. 2005. “On the Reproduction of the Musical Economy after the Internet.” Media, Culture & Society 27 (2): 177–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443705050468.

- Lee, J. 2014. K-Pop: Popular Music, Cultural Amnesia, and Economic Innovation in South Korea. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Long, P., and S. Barber. 2015. “Voicing Passion: The Emotional Economy of Songwriting.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 18 (2): 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549414563298.

- Long, P., and S. Barber. 2017. “Conceptualizing Creativity and Strategy in the Work of Professional Songwriters.” Popular Music and Society 40 (5): 556–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1351134.

- Marshall, L. (Ed.). 2014. The International Recording Industries. New York: Routledge.

- McIntyre, P. 2008. “Creativity and Cultural Production: A Study of Contemporary Western Popular Music Songwriting.” Creativity Research Journal 20 (1): 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410701841898.

- Miettinen, R. 2013. “Creative Encounters and Collaborative Agency in Science, Technology and Innovation.” In Handbook of Research on Creativity, edited by K. Thomas and J. Chan. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 435–449.

- Moore, A. 2013. Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Moorefield, V. 2010. The Producer as Composer: Shaping the Sounds of Popular Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Mousse, T. 1998. Horny ‘98. Peppermint Jam.

- Mullen, J. 2015. The Show Must Go On!: Popular Song in Britain during the First World War. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Nasta, L., L. Pirolo, and P. Wikström. 2016. “Diversity in Creative Teams: A Theoretical Framework and a Research Methodology for the Analysis of the Music Industry.” Creative Industries Journal 9 (2): 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2016.1154653.

- O’Dair, M. 2019. Distributed Creativity: How Blockchain Technology Will Transform the Creative Economy. Cham: Springer.

- Osborne, R. 2017a. “Success Ratios, New Music and Sound Recording Copyright.” Popular Music 36 (3): 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143017000319.

- Osborne, R. 2017b. “Is Equitable Remuneration Equitable? Performers’ Rights in the UK.” Popular Music and Society 40 (5): 573–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1348660.

- Osborne, R. 2022. Owning the Masters: A History of Sound Recording Copyright. London: Bloomsbury.

- Pettijohn, T., and S. Ahmed. 2010. “Songwriting Loafing or Creative Collaboration?: a Comparison of Individual and Team Written Billboard Hits in the USA.” Journal of Articles in Support of the Null Hypothesis 7 (1): 1–6.

- Powell, W. W., and K. Snellman. 2004. “The Knowledge Economy.” Annual Review of Sociology 30 (1): 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100037.

- Rihanna. 2009. Rated R. Def Jam.

- Rosso, B. D. 2014. “Creativity and Constraints: Exploring the Role of Constraints in the Creative Processes of Research and Development Teams.” Organization Studies 35 (4): 551–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613517600.

- Sawyer, R. K. 2003. Group Creativity: Music, Theater, Collaboration. Mahwah: Erlbaum Associates.

- Sawyer, R. K. 2012. Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Sawyer, R. K. 2017. Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration. New York: Basic Books.

- Sawyer, R. K., and S. DeZutter. 2009. “Distributed Creativity: How Collective Creations Emerge from Collaboration.” American Psychological Association 3 (2): 81–92.

- Schiemer, B., E. Schüßler, and T. Theel. 2022. “Regulating Nimbus and Focus: Organizing Copresence for Creative Collaboration.” Organization Studies 44 (4): 545–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221094201.

- Seabrook, J. 2015. The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Shepherd, J. 2016. Tin Pan Alley. New York: Routledge.

- Smudits, A. 2002. Mediamorphosen des Kulturschaffens: Kunst und Kommunikationstechnologien im Wandel. Vienna: Braumüller.

- Sternberg, R. J., and T. I. Lubart. 2002. Defying the Crowd: Cultivating Creativity in a Culture of Conformity. New York: The Free Press.

- Strachan, R. 2017. Sonic Technologies: Popular Music, Digital Culture and the Creative Process. London: Bloomsbury.

- Thompson, P. 2019. Creativity in the Recording Studio: Alternative Takes. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Thorley, M. 2019. “The Rise of the Remote Mix Engineer: Technology, Expertise, Star.” Creative Industries Journal 12 (3): 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2019.1621596.

- Tolstad, I. 2023. “Bring Your A-Game and Leave Your Ego at the Door!” Songwriting Camps as Sites for the (Re-)Production of Practice-Based Knowledge.” IASPM Journal 13 (1): 7–25. https://doi.org/10.5429/2079-3871(2023)v13i1.2en.

- Tough, D. 2017. “An Analysis of Common Songwriting and Production Practices in 2014–2015 Billboard Hot 100 Songs.” Journal of the Music and Entertainment Industry Educators Association 17 (1): 79–120. https://doi.org/10.25101/17.4.

- Tschmuck, P. 2012. Creativity and Innovation in the Music Industry. Cham: Springer.

- Wall, T. 2013. Studying Popular Music Culture. London: SAGE.

- Walzer, D. A. 2017. “Independent Music Production: How Individuality, Technology and Creative Entrepreneurship Influence Contemporary Music Industry Practices.” Creative Industries Journal 10 (1): 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2016.1247626.

- Watson, S. 2011. Using Technology to Unlock Musical Creativity. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Wicke, P. 2011. Rock und Pop von Elvis bis Lady Gaga. Munich: C.H. Beck.

- Wilsmore, R., and C. Johnson. 2022. Coproduction: Collaboration in Music Production. New York: Routledge.

- Zagorski-Thomas, S., Isakoff, K., Stévance, S., and Lacasse, S. (Eds.). 2019. Art of Record Production: Creative Practice in the Studio. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Zak, A. 2009. “Getting Sounds: The Art of Sound Engineering.” In The Cambridge Companion to Recorded Music, edited by N. Cook, 63–76. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Zhao, S., and D. Elesh. 2008. “Copresence as ‘Being With’: Social Contact in Online Public Domains.” Information, Communication & Society 11 (4): 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180801998995.

- Zollo, P. 2003. Songwriters on Songwriting. Boston: Da Capo Press.