Abstract

To address structural omissions of the experiences of makers of colour from the cultural space of craft, Crafts Council initiated the project, Disrupting the craft canon: the cultural value of craft. Partnering with an interdisciplinary team of researchers from Glasgow Caledonian University London, the project was awarded a research grant in June 2022 as part of the first round of funding of the Centre for Cultural Value’s Collaborate programme. Collaborate supports innovative new partnerships between cultural sector practitioners and academics exploring under-explored questions around cultural value so as to deepen existing evidence or surface new evidence. Adopting a Living Lab approach, the team investigated the meanings and cultural value of craft and specifically the impacts of race, racism, immigration and migration on cultural production, making and value grounded in the reality of individuals’ and local communities’ lives. This Participatory Activist Research project helped develop and test research tools including vignettes and object-based stimuli in place-based craft making events with selected Black and Asian UK communities in London and Birmingham. Sinclair highlights the need for ‘research that identifies and recognises the value of the knowledge, experience and cultural heritage of makers of colour in professional, community or other crafts spaces’. This article reflects on the collaborative process, sharing the findings of our community-based research and thereby adding to our understanding of craft’s potential cultural value and the contributions craft can make to sustainable development.

Introduction

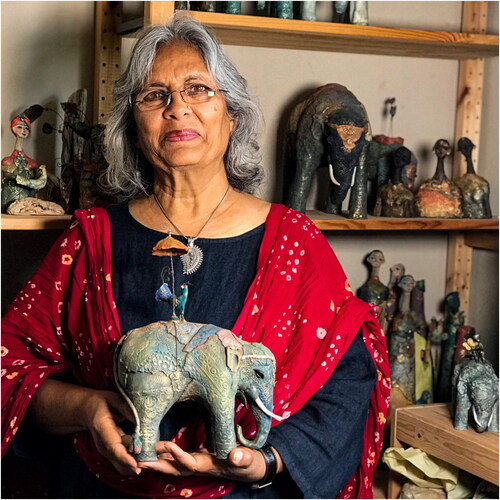

“I grew up in India, bombarded with lots of colours and textures and all the things that you take for granted. I studied microbiology, and when I came to this country [UK], I started work as a scientist, but art has never left me. Being in this country, I suddenly started to feel really homesick for all the colours and textures. I started going to a lot of evening classes while I was working, starting with drawing and painting, and finally, about four years ago, I arrived to a class working with clay, and I suddenly felt I have arrived. At first, it was all purely for my benefit, being able to create and being able to see things in my own home. And now I’ve got work far and wide all over the place.” Pratima Kramer.

These words, taken from a podcast interview with ceramicist Pratima Kramer (see ), give voice to the experiences of a woman of colour working in the contemporary UK craft sector. Just short of 150 words, they formed the starting point for a series of vignettes developed for an innovative Living Lab (LL) research project undertaken by Crafts Council (CC) in partnership with Glasgow Caledonian University London (GCU London) exploring the experiences of makers of colour in London and Birmingham. This article outlines the background to the project Disrupting the craft canon and shares the process and findings of our community-based project, which ran over ten months between 2022 and 2023. The work was supported by the Centre for Cultural Value (CCV)’s Collaborate fund (CCV; Maker Stories Citation2020) and is part of CC’s ongoing anti-racism work bringing people targeted by racism and allies together ‘to increase their collective agency to promote change in power relations and address the root cause of social and health inequities’ (Came and Griffith Citation2018, 183).

Figure 1. Pratima Kramer describes these elephant sculptures as her prayers/tributes to a magnificent animal and deity Ganesh that plays an important part in Hindu religion. Image credit: Pratima Kramer.

Figure 2. Artefacts from Crafts Council’s Handling Collection used in Living Lab 1. Image credit: Natascha Radclyffe-Thomas.

Figure 3. Living Lab 1, East India, London with OITIJ-JO collective. Image credit: Farihah Chowdhury.

Figure 4. Living Lab 2, Edgbaston, Birmingham with Legacy West Midlands. Image credit: Gene Kavanagh.

Figure 5. Jasmine Carey is the first crafter featured in the Maker Stories discussing her experiences and journey in craft. Image credit: Karen Patel.

In the UK, the prevalence of television shows featuring repair and renovation of heirloom and everyday objects, footage of restorers and makers working behind-the-scenes at cultural institutions, celebrities turning their hands to learning new skills and skilled amateur makers going head-to-head to bake, throw or sew has been heralded as a renaissance for craft and creativity. During the unprecedented and destabilising period of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people discovered – or rediscovered – the comfort and rewards of making. The range of informal and formal education in making and the creative arts has expanded as more people reconsider how they earn their livings, rejecting traditional corporate careers for micro-businesses and artisanship. Yet despite anecdotal evidence of increased engagement in craft and notwithstanding the impact of national craft initiative the shape of things promoting culturally diverse makers (Tsot, n.d.), overall craft sector growth does not appear to be reflected in participation rates of makers of colour; figures which remain unchanged compared to 2006 (Crafts Council Citation2020, 8). In the USA, Jen Hewett curated a collection of artist profiles, first-person essays and interviews published in response to the lack of diverse voices of artists working in fibre arts and crafts in the United States. Many of these show how makers of colour ‘felt excluded from – unrepresented – in the craft community’ (Hewett Citation2019, 2). Crafts Council’s own research on craft participation in the UK identifies a deficiency in the existing understandings of craft’s potential cultural value resulting from the historic dominance of the Eurocentric/global North craft canon (Patel Citation2021). However, measures of economic activity, participation rates and cultural value are not objective. Definitions of the cultural value of craft should acknowledge and reflect the structural and historical inequalities that affect access. In the foreword to the Special Issue Craft economies and inequalities (2022, 25:6) Patel and Dudrah argue that work on inequalities in the area of creative industries tends to neglect craft as a subject for research despite evidence of an eco-system underpinned by exploitation and extractive practices of the Global South by the Global North. Paradoxically, where links between craft and race are made, these frequently minimise makers’ complex and multi-faceted identities resulting in simplistic and essentialist representations and attributions (Dillon Citation2022). Given a de facto inequality of access to arts and culture, continuing to operate within narrow and hierarchical definitions of what constitutes the arts and cultural canon only perpetuates a ‘deficit model’ narrative diverting ‘attention from the cultural practices to be found in supposedly excluded populations and communities’ (Crossick and Kaszynska Citation2016, 31).

The project reported on in this article aimed to disrupt the limited understanding of craft’s potential cultural value by centering the experiences of makers of colour. Guided by Crossick and Kaszynska (Citation2016) seminal Cultural Value Project report Understanding the value of arts and culture, the authors were determined to question how and by whom craft is defined, and to explore both established and novel ways to measure how craft might contribute to cultural value and positive wellbeing outcomes at individual and community levels. Crossick and Kaszynska cite multiple examples of work investigating why the arts and culture matter, and the variety of methods designed to capture their effects. Its conclusions provide a useful framing for the current study. In rejecting binary and limiting understandings of ‘value’ as being either intrinsic or instrumental, Crossick and Kaszynska caution that without challenging the hegemonic system, researchers and policy-makers too frequently focus on the absence of people of colour from a pre-designated range of cultural activities, rather than question the types of engagement designated as ‘valuable’ by the system. Furthermore, they advocate for individual level studies to better understand how art and culture affect the capacity to be economically innovative and creative, recovery from physical and mental illness, or the resilience of communities and neighbourhoods (Crossick and Kaszynska Citation2016). It is for this reason our project worked at a grass-roots level, with community-based projects, trying to gather data and understand if, how and when people get involved in making craft and enter into it as a profession. In addition, our study asked what the perceived barriers to entry into craft as a personal practice and/or as a profession are, and what needs to happen to make access easier and more equitable.

Literature review

Craft contributes significantly to the cultural and creative economy nationally and globally. UNESCO estimates that as a sector, craft – defined as handcrafted goods of media including glass, textiles, wood, metal, clay paper and ceramics – represents over half of all cultural and creative productivity (UNESCO,Footnote1 2013 in Brulotte and Montoya Citation2019). 2021 was declared the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable DevelopmentFootnote2 at the 74th United Nations General Assembly, drawing attention to the role of the creative industries in achieving the United Nations sustainable development agenda. Craft production contributes to several of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), primarily: 1 (No Poverty); 3 (Good health and Wellbeing); 4 (Quality Education); 5 (Gender Equality); 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth); 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and; 12 (Sustainable Consumption and Production) (British Council Citation2020; Gudowska Citation2020; UNECE Citation2018). Nonetheless, for a sector with such a large footprint and potential for social, economic and environmental transformation, craft remains an ill-defined term and attempts to measure participation in craft have been deemed inadequate and exclusionary.

Traditionally craft has represented the antithesis of mechanisation, with its associations with handwork, apprenticeships, authenticity, heritage, tradition and pre-industrial production. Brulotte and Montoya trace the origins of the word craft to the Germanic word kraft (skill), foregrounding the dilemma for anyone studying and/or evaluating craft, that meanings and associations are never fixed but open to interpretations that vary ‘across time, geographic space, and social configurations’ (Brulotte and Montoya Citation2019, 17). By asking: ‘who has the power to define, or, better yet, claim craft: the maker, the consumer, or some other intermediary, such as the World Crafts Council?’, they explicitly highlight craft’s lack of immunity to the systemic class, racial/ethnic and gender inequities that pervade society influencing understandings of craft’s economic and/or symbolic value (Brulotte and Montoya Citation2019, 18). Literature on craft tends to frame it through culturally-symbolic products and skills, giving the illusion that cultural diversity is well-represented in the craft canon (Dillon Citation2022). Yet Patel’s contribution to Craft economies and inequalities describes how predominant craft hierarchies exemplify the impacts of structural inequalities on understandings of cultural value (Patel Citation2022). Without acknowledging a broader knowledge base of people and practices, attempts to assess creative artefacts reinforce colonialist hierarchies that preference dominant Western makers and materials, and exoticise and ‘other’ the non-Western (Radclyffe-Thomas Citation2014). Craft is frequently discussed, and commercialised, in terms of makers’ ethnicity and culturally-situated traditions, resulting in stereotyping and narrow representations based on particular products and skills that both oppress and exclude makers of colour (German, 1994) essentialising the ‘different ideologies and practices of craft and making that unfold within different identities and different intersections of life’ (Dillon Citation2022).

As well as a paucity of research on craft contexts in the Global South, much research on craft in the Global North reinforces assumptions that the contemporary craft economy is a comparatively homogenous space (Patel and Dudrah Citation2022). For example, in many museums and collections non-European crafts are represented and classified solely as culturally-symbolic products, thus reinforcing existing biases within the canon. How the concept, practice and sector that is craft is understood may be culturally specific. Yet, makers themselves are aware of the risks of being viewed solely through a cultural lens. Designer Wang Yiyang describes Chinese designers’ self-exoticising and perpetuating of stereotypes of Chinese design through their use of a narrow set of design elements in fashion and film. By repeatedly referencing the qipao, dragons, red lanterns and Cultural Revolution imagery, Chinese designers themselves contribute to the persistence of a static and one-dimensional national identity (Tsui Citation2009, 208). Alternatively, as designer Akhil Nagpal put it, explaining the premise of his Delhi-based avant-garde label that contemporises Indian craft: ‘We need to stop turning our craft into clichés just because we feel like the West will lap it up’ (Thakkar Citation2021).

Craft has been included as a distinct area of the creative sector in the UK by the Department for Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) since 2015. Yet, the available data on the background of craft makers and participants, whether professionals or those working in everyday and domestic contexts, remains weak. The Understanding Everyday Participation (UEP) project, which ran from 2012 to 2018, attempted to broaden definitions of cultural participation, extending these beyond engagement with traditional institutions such as museums and galleries. In an Editorial for a special issue of Cultural Trends (2016, 25:3), the UEP’s lead researcher questioned the predominance of quantitative measures of cultural participation. They argue that surveys, including the UK government’s national Taking PartFootnote3 survey, reduce the cultural field ‘to a partial and specific set of measurable indicators that both represent and help to reinforce particular ways of “seeing” participation’ (Miles and Gibson Citation2016, 152). In the same issue, Taylor critiques Taking Part for only capturing the participation of the ‘well-off, well-educated and white’ (Taylor Citation2016, 169). In contrast, the UEP sought to reverse the deficit model by researching what people actually do, and why those activities are important to them (Miles and Gibson Citation2016). Luckman’s article ‘Who counts, and is counted in craft?’ raises questions that alert researchers to the ‘absences and erasures within craft and cultural and creative practice more generally’ (2022:941). Even the UK Government recognises ‘the significant under-estimate of the scale of the true Crafts industry’ in Economic Estimates prepared by the DCMS, despite an increased focus on the creative industries as drivers of economic value (DCMS. Citation2023, 19). This situation leaves organisations, individuals, communities and policy makers in an inadequate position to try to engage with and understand the breadth and diversity of who is engaged in craft and making, what it means to them and how to identify and respond to their needs.

In an attempt to explore the demographic breadth of those involved in craft occupations in the UK, Crafts Council commissioned research using the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC codes). The resulting report Who Makes? An Analysis of People Working in Craft Occupations (Spilsbury Citation2018), finds those working in craft are more likely to be from White ethnic groups; whilst twelve per cent of all workers are from ‘BAME’Footnote4 groups in the overall workforce, this figure falls to four per cent when controlled for occupations related to craft. Spilsbury sets these figures against Government figures for ‘BAME’ participation in craft between 2014–15 and 2016–17, which appear to show a change from 10.1 per cent to 15.3 per cent (a 5.2 per cent increase). By contrast the number of white participants increased by 1.7% to 22.6 per cent over the same period.Footnote5 Notwithstanding questions of validity owing to small sample sizes, one interpretation of these differences could be that ‘BAME’ people experience(d) more barriers to entering the craft workforce in contrast to their experiences of making in informal and/or domestic settings.

We have not attempted a full review of the literature on craft here, but rather draw attention to some of the links made between engaging with craft and positive individual and societal benefits as well as critiques of predominant research methodologies designed to capture the practices and cultural value of craft. And going beyond craft’s direct relation to economic activity, the UK’s All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing report, Creative Health, concluded that ‘arts engagement has a beneficial effect upon health and wellbeing’ (APPGAHW Citation2017, 11). The World Health Organisation’s 2019 scoping review on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being concluded that ‘there is a substantial body of evidence on the health benefits of the arts’ (Fancourt and Finn Citation2019:52). Craft in Art Therapy (Leone Citation2020) is an edited collection of contributions from practitioners who use crafts for self-care and/or in individual, group and community art-therapy practice. In addition, crafting is frequently referred to as a therapeutic practice outside clinical definitions. Positive psychologist Csikszentmihalyi’s ‘flow’ concept conceptualises the state of complete absorption people often describe feeling when they are making – optimal flow is said to be experienced when a task’s complexity matches one’s perceived skill level (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1997). Pöllänen’s Pöllänen (Citation2015) study of fifteen textile craft-makers reporting stress in work and non-work settings, shows how craft is used as a leisure activity to ameliorate and manage different types of stress, highlighting participants’ flow experiences. It compares the effects of engaging in self-defined ‘easy’ crafts which participants felt helped them to face the sorts of stress encountered in everyday life, with crafts activities that required sustained concentration and the learning of new skills which they perceived as helping them adjust to challenging situations, and bolstering optimism (Pöllänen Citation2015). Bone and Fancourt (Citation2022) report on arts and cultural engagement and the brain provides multiple evidence sources for the link between engaging in creativity and culture and positive wellbeing. Relevant to our study, they argue that these wellbeing benefits are higher for those living in highly deprived areas.

Research context

Founded in 1972, Crafts Council, the UK’s national charity for craft, has a mission to inspire making, empower learning and nurture craft businesses. Crafts Council supports UK-based craft makers and businesses, running learning and participation programmes, and celebrating, promoting and sharing the work of the craft sector. Crafts Council publishes an in-house magazine Crafts showcasing ‘a dynamic global community of makers, curators, collectors, thinkers and cultural influencers pushing the boundaries of making’ (Crafts, n.d.). Crafts Council has a library and archive, and a Gallery space in London. And, most relevant for this article, Crafts Council hosts the national collection (Primary Collection) of contemporary craft as well as a Handling Collection comprising over 700 objects including ceramics, jewellery, textiles, furniture, glass, metal and basketry.Footnote6 The current collecting policy ‘prioritises original work that embodies rich learning potential, especially in its physical and tactile qualities for handling, as well as makers’ conceptual or narrative approaches’ (Crafts Council, n.d.). Given its role in promoting crafts both within the UK and beyond, Crafts Council holds considerable epistemic power to legitimise artists, makers and activities as ‘craft’. Parallels can be drawn to Becker’s concept of ‘artness’ whereby the art community gatekeeps collective beliefs about what constitutes ‘art’ (Becker Citation1982). In other words, those who benefit in reputation and visibility from Crafts Council’s bestowal of the honorific title ‘craft’ on their practice are given credibility by having achieved ‘craftness’.

In 2020, Rose Sinclair, an academic, researcher and curator, wrote in Crafts that ‘efforts have been made to make the craft sector more diverse, but many of these offer short-term fixes for what are long-term issues’ (Sinclair Citation2020). In the same year, Crafts Council received public criticism on social media pointing out a lack of progress and visibility of measures to match its stated commitment to anti-racism and inclusion. The critiques were acknowledged in a 2021 Stories post from Craft Council’s executive director (Crafts Council Citation2021), and in the foreword to Making Changes in Craft (Patel Citation2021, 8). In response, Crafts Council created an informal steering group that developed a Global Majority branch to act as a network for Black, Asian and ethnically diverse makers, craft businesses and professionals. Subsequently, this group was formalised as an Equity Advisory council (2023) becoming an embedded part of Crafts Council’s organisation as it continues its work on understanding the impact of racism and inequality on craft as a sector (Anjum et al. Citation2023).

Building on Supporting diversity in craft through digital technology skills development, an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Creative Economy Engagement Fund (CEEF) project (Patel Citation2019), Crafts Council extended work with Dr Karen Patel of Birmingham City University on an AHRC-funded UKRI/RCUK Innovation Fellowship looking at the experiences of makers of colour in the contemporary UK craft sector. The resulting project Supporting diversity and expertise development in the contemporary craft economy (short name: Craft Expertise) ran from 2019 to2021 and was the first to highlight the lived experiences of women makers of colour in contemporary UK craft. Its phase one project report Making Changes in Craft highlighted the persistence of gender, ethnic and socio-economic inequalities (Patel Citation2021, 14) and Patel concluded that ‘urgent change needs to be made to make craft spaces safer and more welcoming for people from marginalised groups. The contemporary craft sector is characterised by whiteness and elitism’ (Patel Citation2021, 14).

Quoting from the Making Changes in Craft report (Patel Citation2021, 9), the key issues raised by Crafts Council were:

The narrow craft canon and Crafts Council’s place in it

The lack of alternative histories and narratives in craft

The need to de-colonise the craft curriculum

Lack of initiatives to nurture Black, Asian and ethnically diverse makers

Need for more visual representation

In response to Patel’s findings, Crafts Council were keen to tackle racism in the sector by understanding more about the meaning and value attached to making by minoritised communities and committed to disrupting the Eurocentric/global North craft canon and the cultural norms that limit understanding of craft’s potential cultural value. Recommendations from Making Changes in Craft included the need for a reframing of the narrative of craft to give ‘space to makers from a wider variety of traditions to tell their story’ (Patel Citation2021, 72). To achieve this, Patel highlighted the need to design data collection methods so that ‘data about the crafts sector accurately represent(s) the breadth of makers’ (2021:74). Crafts Council’s belief in the importance of achieving a sector understanding that reflects the impact of immigration, migration, movement, displacement and community on cultural production and making became a driver for the study that we focus on here.

The Centre for Cultural ValueFootnote7 (CCV) is a national research centre working with cultural practitioners and organisations, academics, funders and policymakers supporting research, discussion and public debate around cultural value, especially focussing on the differences that arts, culture, heritage and screen make to people’s lives and to society. In 2021, the CCV launched Collaborate a fund for the development of new research projects between the UK cultural sector and academic researchers. The Collaborate application process was multi-staged. Firstly, cultural sector applicants submitted expressions of interest (project proposals) to CCV which were shortlisted to the strongest ten proposals (October to November 2021). Following this, academic researchers submitted a response to the cultural sector proposals (December 2021 to January 2022). There followed a ‘match-making’ process before the final set of cultural practitioner-academic partnerships were established. Cultural-academic partnerships had until May 2022 to co-develop a research question and methodology, and submit this as a joint application to Collaborate.

In responding to the call for cultural partners, Crafts Council saw an opportunity to build on Patel’s work by exploring what craft means in the context of a wider range of communities and individuals. In so doing, Crafts Council envisaged a way to extend the evidence base about the value of craft within a selection of communities and help determine the direction of change needed to tackle the issues raised in Patel’s work that reflected Arts Council England’s (ACE) Inclusion and Relevance principle.Footnote8 Serendipitously, Collaborate arose as Glasgow Caledonian University London researchers were refining creative, interdisciplinary research approaches to promote sustainable development as it relates to lifestyle and wellbeing,Footnote9 and Crafts Council’s provocation to disrupt the craft canon resonated with this.

GCU London’s campus is situated in London’s Spitalfields, immersed in the histories and current context of creative industries and their links to immigration, migration, movement, displacement and community. The GCU London team comprised academics from the disciplines of cultural creativity, marketing and sustainable fashion, and behavioural science in public health and included a pracademicFootnote10 who is the co-founder of OITIJ-JO Collective,Footnote11 a Tower Hamlets-based charity social enterprise that promotes Bengali arts and crafts traditions. In the response to Crafts Council’s initial project, the GCU London team proposed community-based collaborative research to develop a Living Lab (LL) methodology,Footnote12 to explore the themes of craft and cultural value through the medium of craft itself. The LLs would be designed to stimulate reflection and projection and thus capture the experiences and issues related to craft which are significant to local communities. Building on our respective work, experience and networks with craftspeople and in the community, the authors hoped to provide findings and tools to positively impact individuals, groups and communities. The CCV cohort briefing arranged at the start of working together encouraged teams to ask themselves the sort of generative questions such as ‘how might we?’, ‘what if we?’ and ‘what else could we do?’, as well as to consider the impacts and after-life of our projects. What followed was a period of individual and collective reflection and discussion. Several themes and approaches were considered before finalising the research questions:

How is craft experienced and conceptualised by makers of colour?

How does craft add value for the individual and communities differentiated by race?

What is the contribution of the Living Lab method to capturing the meaning and value of the knowledge, experience and cultural heritage of craft makers of colour?

Central to these, were the questions as to what it could or should look/feel like to disrupt the Eurocentric/global north craft canon and how best to design original research to help to redefine craft as it is practised across UK communities. However, it is one thing to advocate for better evidence and another to create the means to record this, since ‘capturing what happens in cultural experiences is not an easy task’ (Crossick and Kaszynska Citation2016, 123). To embed the project in Crafts Council’s wider anti-racism work, members of its Equity CouncilFootnote13 (formerly Global Majority branch) chaired the project’s steering group, alongside other members drawn from Crafts Council’s team. This was a female-led research project. Moreover, in order to co-design inclusive research, the wider GCU London team comprised a number of PhD students and Early Career Researchers with experience of collaborative community engagement and research – who identify as women of colour or are from a marginalised background – who were employed as research assistants. To add further value and develop young researchers, Crafts Council funded a Young Craft Citizen (YCC)Footnote14 placement. Everyone involved in the project was invited to share their reflections which are incorporated in the project report published by Crafts Council “Wow, I did this!” Making Meaning through Craft: Disrupting the craft canon (Radclyffe-Thomas et al. Citation2023) and will feed into a CCV Learning Case Study.

Methodology

“Living Labs (LLs) are open innovation ecosystems in real-life environments using iterative feedback processes throughout a lifecycle approach of an innovation to create sustainable impact. They focus on co-creation, rapid prototyping and testing and scaling-up innovations and businesses, providing (different types of) joint-value to the involved stakeholders.”The European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL Citation2020)

Traditionally, much research remains hidden within the walls of the academy. Collaborate called for developing new and innovative methodologies to measure cultural value and encouraged the co-creation of methods with participants themselves. Our exploratory study was designed to address structural omissions of the experiences of makers of colour from the cultural space of craft and one of our intentions was to test a range of ways to ask people about craft using a LL methodology. LLs have been employed for some time as user-centred, open-innovation ecosystems situated in real-life environments including public health and the built environment. Increasingly LLs focus on ways to deliver innovative, co-created solutions to local social problems using co-creation, rapid prototyping and testing. Convening stakeholders/actors of the Quadruple Helix model – citizens, government, industry and academia (ENoLL Citation2020) – they aim to ‘elicit unforeseen user ideas and behaviours to enhance product innovation’ (Sauer and de Rijke Citation2016). Thus, the LL methodology places community at the core and, whilst there is no single LL methodology, in practice various user-centred, co-creation methodologies are combined and/or customised to suit the specific purpose of the lab. In their scoping review of Living Labs and Higher Education, van den Heuvel et al. (Citation2021) emphasise the importance of investing in relationships between co-creators. Thus, the involvement of community partners in the planning and delivery of the Living Labs was essential. The GCU London researchers developed our LL concept by undertaking a nine-week Virtual Learning Lab with the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL) addressing the five major elements of the living lab: real-life setting, co-creation, active user involvement, multi-stakeholder participation and multi-method approach (ENoLL Citation2020). Adopting the LL as a decolonised research methodology we sought to challenge traditional models of generating evidence by being critical of the dominant assumptions, motivations and values which inform these (Kovach Citation2021; Smith Citation2012, 606).

It was important not to reinforce assumptions and/or stereotypes about our participants. In order to engage in authentic research choices of setting, location, participants, stimuli and ‘feel’ of the LLs were all critical. The concept of our place-based LLs was to work with invited participants from specific UK Black and Asian communities, and for them to interact with each other and with researchers whilst taking part in craft-making activities. The goal was to develop a methodology that could capture people’s lived experiences of craft and the value it adds to their lives, and to understand barriers to engagement with craft. This approach meant developing methodologies to capture people’s craft journeys. This would constitute a life-course approach, considering how people experience craft from childhood onwards to adulthood in order to ‘understand how social inequities are perpetuated and transmitted, and how they can be mitigated or alleviated through the generations’ (PAHO, n.d.). In practice, we would be finding out about how and when people are introduced to craft and what kind of craft practices they are familiar with, why some people continued with craft practices and others did not, and exploring the barriers and/or enablers to participation.

Building on experience in public health research with hard-to-reach communities, the use of vignettes was explored, becoming central to our research toolkit. Vignettes are used in qualitative health and social science research to assess respondents’ attitudes, values, norms and perceptions. A short story/narrative based on a fictional or real protagonist is shared with participants who are asked to reflect on the situation and/or actions. Participants can be asked how they would respond to the situation, but equally vignettes can be used to ask participants to suggest how the protagonist would (descriptive norms) or should (injunctive norms) respond. Vignettes therefore allow separation from the personal and can be particularly facilitative for generating discussions about sensitive topics. (Blum et al. Citation2019). In our case, each vignette was drawn from real UK-based makers (see ), selected due to their existing links to Crafts Council’s work. These were primarily makers of colour whose work is in the Handling Collection. In addition, two crafters were selected from the Craft Expertise project. These were deliberate decisions aimed at highlighting the range of materials and personal and professional experiences of makers of colour. Since we were interested in exploring a diversity of paths into craft, craft careers, experiences as crafters, as well as materials and techniques, this was also a deciding factor for selection. The LLs were ‘implicitly designed to provide a range of craft role models from minoritised communities operating in various functions within the UK craft ecology’ (Radclyffe-Thomas et al. Citation2023, 38), including the crafters who featured in the vignettes, the makers selected from the Crafts Council’s Handling Collection, our maker-educators and, to some degree, the research team itself.

Table 1. Crafters selected for vignette development.

Since we were interested in generating conversations about craft rather than interviewing individuals, the LLs were informed by focus group design and Stitching together: Good practice guidelines (Twigger Holroyd and Shercliff Citation2020). By participating in craft-based activities, engaging in informal conversation and responding to prompts in the form of pre-written vignettes and questions derived from existing scales on wellbeing and value, we would prompt reflection on individuals’ craft experiences. In this way we would be surfacing participants’ lived experiences, their understandings of the cultural value of craft, and specifically the impacts of race, racism, immigration and migration on cultural production, making and value. From the resulting interactions, we would generate the questions about the value of craft most relevant and important to those communities. As such, we designed the LLs as Participatory Activist Research, understood as research that ‘read(s) the world for difference, and to notice the mundane and the everyday’ (Pickerill et al. (Citation2021, 3). Influenced by feminist and postcolonial frameworks rather than extracting knowledge from communities, Participatory Activist Research aims to contribute actively to the goals of the individuals and groups involved in the research (Pickerill et al. Citation2021).

Given the small scale of funding available, we were limited to holding one LL in London and one outside of London for up to 15 participants. Crafts Council uses its London gallery space to host participatory craft events, so it was an option to hold our LLs there. However, inviting people into a formal gallery space may have presented a barrier to participation and influenced our participants’ understandings of craft practice and materials. So, in line with a commitment to decolonise research and design a less extractive research methodology, two community partners were engaged to host and co-design the LLs to ensure they would be grounded in the reality of our selected Black and Asian UK communities. The choice and locations of our community partners were both significant to the story of craft in the UK and referenced in their respective craft activities. The London LL was planned with community partner OITIJ-JO Collective, based in their venue in East India, an area with links to the historic colonial indigo trade. Co-design was greatly enabled in our LL project by Maher Anjum, co-Director at OITIJ-JO being a member of the research team. The maker-educator was Shama Kun, a sustainable and ethical fashion designer whose work celebrates Bangladeshi heritage textiles. The craft selected for the session was indigo resist dyeing and Shibori. The majority of participants self-identified as Bangladeshi/British Bangladeshi origin; others self-identified as African and Asian/Asian British. The ages of participants ranged from early thirties to late fifties with a median age of early forties.

The Birmingham LL was planned with community partner Legacy West Midlands (LWM), held in their venue in Edgbaston, an area that has experienced long-term economic disadvantage. LWM is a charity celebrating the heritage of post-war migrant communities in Birmingham. They deliver projects focused on food, architecture, migration, and industrial history to increase local awareness of the area’s diverse cultural heritage, and use it as a resource to promote physical and mental wellbeing and entrepreneurship. Birmingham is a city with historic links to crafts including the leather-trade and the jewellery industry. The maker-educator was Deborette Clark, a designer-maker who works with leather. The craft selected for the session was leather-work. The majority of participants self-identified as Chinese/British Chinese origin; others self-identified as Indian, Asian/Asian British. The ages of participants ranged from early fifties to late sixties.

Both LLs followed the same structure, but each lasted a different duration since it was desirable that our activities should fit into the community partners’ regular meeting patterns. The opening and closing of each LL was led by a maker-educator who introduced themselves and the wider project team in attendance, outlined the purposes of the session and gave an overview of the craft activity. Groups of three/four participants sat at tables with a researcher and note-taker. After confirming the relevant permissions, a period of table-based making followed. At a time designated by the maker-educator, the focus group element of the Lab commenced. Objects and vignettes were introduced as stimuli to prompt reflection and discussion. As participants worked on their craft projects, a researcher took them through a series of questions related to the stimuli whilst a note-taker recorded observations and captured impressions of the interactions. To minimise language and cultural barriers between participants as well as between participants and researchers, members of the research team acted as translators and cultural brokersFootnote15 (Hennink Citation2017). In addition, both participants and researchers tried to find common language in posing questions and interpreting responses. The focus group element was the ‘filling’ in the LL session so, after concluding this, there was time for participants to complete their craft works and for the maker-educator to bring the session to a close. Participants were invited to complete an anonymous participant profile form and exit survey (see below). Refreshments were provided during both LLs and participants and project team engaged in informal social interactions over food at the break and after the conclusion of the Labs.

Vignettes, objects and scales

“In the fashion industry in the sample room and the pattern cutting room there is a diverse mixture of people. But for craft, for leather craft and places that I go to, there’s been times I’m the only person of colour. I think it’s important for people who are thinking of working in craft or interested in craft, knowing that there’s other people like you around because representation does matter. It makes a big difference. When I first saw the other people in the studios, I thought, they’re high status, very skilled. When I looked around I didn’t see many people who looked like me, and were from my background and I thought that I did not belong there. If you’re the only one, it can feel like you stick out like a sore thumb and you feel like you’re the representative, you don’t want to be, but it can be like that.” Jasmine Carey (Maker Stories Citation2019). (See ).

Our vignettes comprised scenarios drawn from a broad range of UK-based crafters (see ) encapsulating accurate accounts of real crafters’ education, work and experiences across a range of topics relevant to our research. The image-based vignettes used text that was transcribed from podcast interviews with the crafters featured, along with a selection of images of the respective crafter and their work. The object-based vignettes were introduced alongside actual craft artefacts from Crafts Council’s Handling Collection and used text drawn from a variety of public sources. Each vignette had five or six different types of questions using the crafter’s words to prompt discussion. For example: “What do you think Pratima’s experience of coming to a career as a maker later in life says about how much craft is valued as a career choice?”, or “Jasmine says she felt that she ‘belonged’ when she started working with leather and that her craft is ‘a journey she will always be on’. What do you think she means by this?”

Vignettes also included summary measures of subjective wellbeing taken from the European Social SurveyFootnote16 (ESS. n.d.). For example: “When Simon was at school he was bottom of the class in art and it was only when he was 30 that he started to explore a creative career. Using this card please tell me to what extent you learn new skills in your life?” Scales such as the Cantril ladder (Cantril Citation1965) were adapted to test their ability to capture participants’ views on the present and desired social status of crafters. For example: “How would your parents/family/friends have reacted if you said you wanted to work in craft? There are people who tend to be towards the top of our society and people who tend to be towards the bottom. On this card is a scale that runs from top to bottom. Can you put a cross on where you would place people who work in craft nowadays?”

As such, they outlined various real-life situations and scenarios and provided stimuli to discuss:

Participation in individual craft activities.

Participation in community craft activities.

Cultural appreciation/appropriation of craft.

Societal value of craft.

Personal wellbeing in relation to craft.

Each vignette included the question: “Is there anything else you would like to say about this topic?” Following the close of the LLs, participants completed an anonymous participant profile formFootnote17 and an anonymous exit survey which included a scale measure for flow (level of challenge/relaxation) – two further wellbeing measures drawn from the European Social Survey. Finally, participants were asked: “What is(are) the most important thing(s) you would like the research team to take away from your experiences and the conversations we have had about craft and making today?”

For the first LL it was estimated that there would be sufficient time to use both an image-based and an object-based vignette with each small group of participants. For the second, shorter LL either an image-based or an object-based vignette was used. Both researcher and note-taker had briefings and question guides and, since the LL was a space of creativity and community, they were encouraged to let conversations flow freely, responding to any direct questions from the participants. The conversations were audio-recorded and a photographer and videographer were present. The handwritten notes taken by note-takers during the LL were later transcribed and thematically analysed along with the audio recordings. Each member of the project team was invited to capture their impressions of the LL in writing immediately after the close, before a group debrief. Some members provided additional written reflections after the conclusion of the LLs.

Findings and discussion

’A fundamental theme underpinning all discussions about the value of engagement with arts and culture is what we know, what we don’t know and the sources of our knowledge.’Crossick and Kaszynska (Citation2016, 9)

Our research is ‘concerned with how the world is experienced, in specific situations by specific people at specific times’ (Crossick and Kaszynska Citation2016, 123). The challenge was how to find out about people’s experiences of craft and the cultural value assigned to various craft activities and careers. As such the research is inductive, grounded in situated craft practices with selected communities. LLs provided an opportunity for co-creating knowledge on the value of craft to those involved in our study, their experiences of craft and the opportunities and barriers they perceive to their practice. A summary of the findings is discussed below; the full findings are presented and discussed in the project report “Wow, I did this!” Making Meaning through Craft: Disrupting the craft canon (Radclyffe-Thomas et al. Citation2023).

Each group within the LLs was given different vignettes and materials from the Handling Collection to prompt discussion on how craft is defined, practised and valued by our participants. In the resulting conversations, craft was mentioned particularly in relation to the value it has for family and tradition. Participants linked craft practices to culture and identity, frequently referencing female family members’ historic crafting practices. Participants observed how craft can (and should) be used to inform young people about their culture and spoke of a desire for more opportunities for their children and for themselves to explore their own cultures through crafting. One participant observed how ‘traditional’ crafts were at risk of becoming diluted or even invisible:

“The more it’s become more westernised it gets hidden, hidden as in the culture of Bangladesh, sewing, the actual sewing itself was like a tradition. Every Bengali household knew what it was. My grandmother, my grandmother’s mother, mothers, every single woman in the household, would know how to do it, even a little six-year-old would know how to do it.” (Participant A).

Participants’ interpretations of vignettes showed they recognised how many diaspora crafters use craft to (re)connect with their culture. One participant said in response to a vignette featuring Pratima’s figurative ceramics inspired by Indian cultural heritage: “It brings back to her, culture back again, so the things that’s been missing” (Participant B). This demonstrates craft’s role in keeping traditional skills, techniques and materials alive, which is the definition of cultural heritage as a dynamic concept (Shuzhong and Prott Citation2013). As to what comprises craft, a multitude of activities and materials were described both in the participants’ own practice and childhood recollections or visits to countries such as Bangladesh, India or Hong Kong. The crafts mentioned offer a wider interpretation of craft, challenging the predominant canon, and included sewing, knitting, crochet, jewellery-making, painting, calligraphy, cooking, bamboo-weaving and hair-braiding. Within this wider range of crafts, participants saw value in how craft can communicate themes of significance to diaspora communities. When encouraged to develop their own designs, several chose culturally significant objects or imagery, for example a boat (Bangladesh) or notable landmarks (Lion’s Rock, Hong Kong).

The topics of mindfulness and crafting’s ability to integrate mind, body and spirit were raised in many of our participants’ conversations. They highlighted the value of contemplative craft practices to create positive self-affect states and to positively impact wellbeing. Taking part in craft to make themselves feel good, or to cheer themselves up aligns with Benedek, Bruckdorfer, and Jauk (Citation2019) whose research showed intrinsic motives (enjoyment, and the expression and development of one’s potential) are the major reasons for engaging in everyday creativity. Several participants told us how craft and making helps them to explore their inner feelings, describing craft as a form of ‘therapy’. Others reflected on how they use making as a meditative process: the intense concentration of learning and practising craft keeps their minds free from both the everyday and globally significant worries. Participant A reflected: “It helped me adjust my mind away from other things that’s happening around the world, not just in the world, but generally my life.”

Significantly, but perhaps not surprisingly, many participants identified the communal aspect of crafting as being particularly beneficial to individual wellbeing. Time spent in craft groups was referred to as an ‘escape’ from daily life, a chance to meet new people and share experiences of learning new skills. This finding is consistent with Hewett (Citation2019) whose work shows craft allows for both individual and communal creative expression. The value of craft as a medium for community building was recognised by participants who drew parallels between the small-group, social format of the LLs and the sorts of group community practices they were familiar with. Participants reminisced about groups of women coming together to work on joint projects, for example, remaking old sarees and decorating them with Nakshi Khantha embroidery for a baby’s birth blanket. And beyond these culturally-specific practices, several participants noted that craft is facilitative for anti-racism work by, for example, bringing different communities together in joint craft activities and using these to learn about each other. Participant C shared how, “At the school I used to work in, we had this coffee time for parents and they had a club for a while… it was a lovely way of bringing the native British women and Bengali women together and do crochet. And they were sharing and they were learning from each other.”

But, whilst participants’ views of making in groups were generally positive, they also shared personal experiences where they felt excluded and articulated the barriers to participation which exist where craft groups are predominantly mono-cultural. Participant B’s comments echoed several others’ when she stated: “The more you see of your own nationality or your own ethnicity, the better. You can just get in, get in, and get on with what you come for.”

Aside from craft as a leisure activity, the authors were interested in the commercial value of craft and this topic was investigated by asking participants how they/others viewed craft as a career choice. In order not to reinforce the predominant craft canon, vignettes included both crafters who pursued a creative education leading to a career in craft, and those who became crafters later in life, after having pursued a more traditional career first. When asked to place craftspeople’s position in society on a scale ranging from 0 (bottom) to 10 (top), almost all participants placed them in the lower half. So, whilst all our participants recognised the value in craftspeople’s skills, they pointed out the double-standards and intersectional discrimination and privilege (Crenshaw Citation1991) that advantage those with cultural and financial capital, including how Global North economies benefit from the craft expertise of the Global South but do not necessarily recognise or compensate adequately for this (Patel and Dudrah Citation2022). Participant D commented on these exploitative practices, saying: “In south east Asia crafts people are hardly paid, they’re paid a pittance, some of the amazing, amazing work they do. People buy their products and are happy to sell it here for a lot of money….” Participant C vocalised how local migrant communities are prevented from entering the craft sector since: “As an English person, white person, you know how to do this. You know where to go. You know how to connect. You know how to, where to ask for things. And also, you know how to fill things out. As a Bangla person you have to learn all of those things. You have to find where to go to get them, where the connections are.”

Although much of the conversations focused on the changes needed to bring younger people into craft, whether as pastime or profession, participants also highlighted the value of craft for lifelong learning. Most participants did not partake in craft regularly, but some had returned to crafts they practised in their youth and several spoke of how taking part in the LL activities inspired them to engage in further craft activities. When asked about their own/others participation in craft, lack of time was referred to as the main barrier, but also a lack of mentoring and access related to race and minoritised status. The vignettes proved powerful prompts for exploring what our participants thought should change. When participants were asked how to diversify the craft sector several of them mentioned the value of representation and role models, such as the crafters featured in the vignettes. They saw this as particularly important for younger people of colour, to show them that craft could be a viable career.

“It’s good to have someone like Jasmine, who despite probably feeling a bit out of place, to carry on and get her work out there, show. And then young people can think ‘Yeah I’ll give that a go, see I can come up with it.’ Because if she’s doing something that we as a person of colour don’t do much of, and she gets known and her work gets out there. Then, yes she’s a trailblazer” (Participant F).

Given the motivation for the project, one of the main findings is the value of intentional research practices to generate authentic insights and questions of interest to diasporic communities. Research is often an extractive process, but our participants acknowledged how being asked their opinions was important for them, and they responded positively to their experiences in the LL being able to vocalise what they considered of importance for the sector to know and change. Participant D highlighted the lack of opportunities to contribute to studies on cultural value: “…we don’t talk about these things to anybody, who would we even, nobody really”. The energy in the LLs was tangible and several participants vocalised their enjoyment of the sessions: “Thanks for being here and going through this with us because it is nice just to come out and relax and share and have different people around to teach us different skills and ideas and hopefully we’ll take something from this today” (Participant G). As we hoped, vignettes and craft artefacts worked as ice-breakers allowing for a wide and deep range of data to be captured from conversations about craft. Furthermore, explicitly reflecting on the method of the LLs, several participants noted how taking part in craft conversations whilst working with your hands, didn’t feel like a sterile interview; one even described the process as feeling ‘like a hug’. Findings from this project will enable others to generate more nuanced understandings of the difference culture makes, and will promote creative practices and research with social justice central to measures of cultural value. The study suggests future areas of research including: those aligned with the SDGs, with different communities, with those crafting in other spaces/places and involving men, that may offer broader insights into the cultural value of craft and issues around racism in craft.

Conclusions

Our participants wrote in their exit forms that they wanted us to consider: “Diversity (as) a work in progress in people lives”, urging action that would be “Making things better for the next generation.” It is apparent that there have been insufficient opportunities for communities to be involved in co-designing or managing the UK craft ecosystem. Issues of gate-keeping and contextual and systemic factors that promote or impede inclusion at individual or community levels are a fundamental challenge for this type of research. As well as grounding research in real-life challenges, a key feature of Collaborate is an innovative, iterative, reflective process that helps surface issues significant to the cultural sector and communities. By working with a higher education institution in an equal partnership, Crafts Council sought the space and capacity to consider new approaches and new methods to redefine craft as it is currently practiced across UK communities.

Whilst many of the headlines and arguments about the value of art and culture focus on economic, regional and public health impacts, Crossick and Kaszynska (Citation2016) argue for the centering of individual experience in studying cultural value. Without understanding people’s first-hand experience of art and culture, we risk neglecting how the links between art and culture and states and traits such as reflectiveness, empathy and imagination operate. Our Collaborate project set out to disrupt the craft canon. Disruption can be interpreted as necessitating large-scale and/or revolutionary changes. However, research impact (or transformative change) can also mean influencing policy, capacity-building for research participants, creating space for connection and hope and amplifying participants’ voices (Pottinger et al. Citation2021). Hence, we were primarily designing and testing tools to identify and recognise the value of the knowledge, experience and cultural heritage of makers of colour in professional, community or other crafts spaces.

The authors acknowledge the limitations of the study. In this study, we chose to focus on UK-based Black and Asian women and results are based on a small sample of selected communities with only two LLs taking place in inner-city locations in the UK. Other limitations come from the voluntary participation, and the size and nature of the LLs means only a small range of crafts were represented. These factors may exclude valuable inputs.

However, the Living Lab format allowed us to convene creative spaces within which to co-develop authentic research tools grounded in the reality of individuals’ and local communities’ lives.

This study has raised questions about the value of craft to minoritised communities and the personal and professional spaces within it. Just by running the Living Labs and bringing voices from minoritised communities to the table, it was, and is, disrupting the craft canon as it stands. Something as simple as this action can start making a change. For participating group OITIJ-JO, being involved in the research encouraged them to host a panel discussion with women crafters of British Bangladeshi origin and to apply for funding from the RSA’s Catalyst fund to initiate a Design Studio using circular business model. Following the Lab, they were successful in applying for a series of opportunities including an NHS Social Prescribing pilot project, an English Heritage funded workshop in the Elo Melo festival and seed funding to explore the relationship between fermentation, preserving and climate change. Each of these initiatives provides different routes of entry for individuals to explore and engage in crafts, and to decide if they want to enter the sector professionally, and if so how to do it.

As the leading voice of crafts for the last 50 years, Crafts Council has constructed a form of a ‘craft canon’ that cannot be denied. Crafts Council has seen that change is needed and has started the process. Over the last six or seven years it has started to change the rhetoric around craft and the spaces, cultural value and approaches to craft. It is not enough to say it remains to be seen if change will happen, change has to happen. The next generation needs to see their place at the table, hear their voices and see their space in craft. Craft as laid out in this article has intrinsic value in cultures and foregrounds our very beings; for some it supports us to know who we are, and gives voice to other aspects of our cultural wellbeing and belonging. Whilst it is difficult to separate this project out from other Crafts Council initiatives to encourage cultural diversity, our work has helped establish a nuanced understanding of the experiences of these individual UK Black and Asian women, and provided proof of concept for a Living Lab approach to working with minoritised communities in and through craft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 UNESCO defines craft as handcrafted goods that make use of media such as glass, textiles, woods, metal, clay, paper or ceramics. UNESCO. 2013. Creative Economy Report: Widening Local Development Pathways. New York: UNESCO.

2 The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were established by the United Nations in 2015 as a global call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

3 The Taking Part Survey has run since 2005 as the key evidence source for DCMS providing national estimates of engagement with the arts, heritage, museums, libraries, digital and social networking.

4 Due to small sample sizes for some ethnicities, Spilsbury merges ethnicity categories into ‘White’ and ‘Black and Minority Ethnic (‘BAME’)’. The authors use the term ‘BAME’ in inverted commas in the paper since it is no longer a favoured term.

5 See DCMS Adult participation in craft figures 2016/17 in Ad-hoc statistical analysis: 2017/18 Quarter 3 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/ad-hoc-statistical-analysis-201718-quarter-3#november-2017–adult-16-participation-in-craft-activities-201617 and Adult craft participation by key demographics area level variables and education, 2014/15 and 2015/16 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/ad-hoc-statistical-analysis-201617-quarter-4

6 The Primary Collection was started in 1972 as a record of ‘trends and innovation in the materials, processes, skills and technologies of contemporary craft’ intentionally covering a broad view of craft and disciplines including: ceramics, glass, textiles, furniture, metalwork, jewellery, lettering and bookbinding. The Handling Collection was started in 1979 as a way to use genuine craft artefacts – part-made and finished objects, samples, sketches, books and background material – chosen with handling in mind, to support the Crafts Council’s education programmes. It includes pieces at various stages of construction in order to give access to process as well as final product https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/about/collections/about-collections

7 Based at the University of Leeds, the Centre for Cultural Value’s core partners are The Audience Agency and the Universities of Liverpool, Sheffield and Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. The Centre is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (part of UK Research and Innovation), Paul Hamlyn Foundation and Arts Council England.

8 ACE’s Inclusivity & Relevance Principle is a commitment to achieving greater fairness, access and opportunity across the cultural sector. By adopting the Inclusivity & Relevance Principle, England’s diversity should be fully reflected in the individuals and organisations ACE supports and the culture they produce https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/blog/essential-read-inclusivity-relevance

9 Glasgow Caledonian University was the first university to adopt the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) as the framework for research.

10 Popularized by Posner (Citation2009), a pracademic is one whose career spans the boundaries of academia and practice. Posner cites the benefits pracademics bring having significant experience in both the world of academia and practice and describes them as brokers between the two.

11 OITIJ-JO was set up in 2013 through a collaborative process in response to the lack of representation, inclusion and non-acknowledgement and support of creatives and creative practices carried out by those of the Bangladeshi diaspora in the UK.

12 “A Living Lab is a design research methodology aimed at co-creating innovation through the involvement of aware users in a real-life setting” Dell’Era and Landoni (Citation2014).

13 The Equity Council was established in 2022 comprising makers and craft professionals with a shared passion for craft. Drawn from racialised and underrepresented communities acting as critical friends to the Crafts Council on its anti-racism work and embracing an intersectional approach.

14 YCC is a collective of 16-30 year-olds from diverse backgrounds interested in shaping the future of craft, design and making in the UK, hosted by Crafts Council.

15 Individuals with shared cultural backgrounds and cultural sensitivity to the social and cultural context of the research.

16 The European Social Survey has collected methodologically robust cross-national data on wellbeing bi-annually since 2002, providing researchers and policymakers with a rich dataset of Europeans’ wellbeing.

17 Drawn from the ONS questions designed for use with adult respondents to record gender, age and self-identified ethnic group or background.

References

- Anjum, M., J. Bennett, N. Radclyffe-Thomas, and R. Sinclair. 2023. What is an Equity Steering Group? Arts Professional. https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/article/what-equity-steering-group

- APPGAHW. 2017. Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing Inquiry Report. 2nd ed. https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017_-_Second_Edition.pdf

- Becker, H. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Benedek, M., R. Bruckdorfer, and E. Jauk. 2019. “Motives for Creativity: Exploring the What and Why of Everyday Creativity.” Journal of Creative Behavior 54 (3): 610–625. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.396.

- Blum, Robert W., Grace Sheehy, Mengmeng Li, Sharmistha Basu, Omaima El Gibaly, Patrick Kayembe, Xiayun Zuo, et al. 2019. “Measuring Young Adolescent Perceptions of Relationships: A Vignette-Based Approach to Exploring Gender Equality.” PloS One 14 (6): e0218863. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218863.

- Bone, J., and D. Fancourt. 2022. Arts, Culture & the Brain: A Literature Review and New Epidemiological Analyses. London, UK: University College London (UCL), Institute of Epidemiology & Health Care.

- British Council. 2020. The Missing Pillar: Culture’s Contribution to the UN Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/the_missing_pillar.pdf

- Brulotte, R. L., and M. J. R. Montoya. 2019. “Defining Craft: Hermeneutics and Economy.” In A Cultural Economic Analysis of Craft, edited by Mignosa, A., and Kotipalli, P. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02164-1_2.

- Came, H., and D. Griffith. 2018. “Tackling Racism as a “Wicked” Public Health Problem: Enabling Allies in Antiracism Praxis.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 199: 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.028.

- Cantril, H. 1965. The Pattern of Human Concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- CCV. n.d. Collaborate Projects. https://www.culturalvalue.org.uk/collaborate-fund-3/collaborate-projects/

- Crafts Council. (n.d.). About the Collections. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/about/collections/about-collections

- Crafts Council. 2020. The Market for Craft. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/documents/880/Market_for_craft_full_report_2020.pdf

- Crafts Council. 2021. The Crafts Council’s Actions to Address Racism in Craft. Stories. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/stories/one-year-on-the-crafts-councils-actions-to-address-racism-in-craft

- Crafts Magazine. 2020. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/crafts/crafts-magazine

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Crossick, G., and P. Kaszynska. 2016. Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture. The AHRC Cultural Value Project. AHRC. https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/AHRC-291121-UnderstandingTheValueOfArts-CulturalValueProjectReport.pdf

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1997. Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life. Basic Books.

- DCMS. 2023. Economic Estimates 2023, UK Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/dcms-sectors-economic-estimates

- Dell’Era, Claudio, and Paolo Landoni. 2014. “Living Lab: A Methodology between User-Centred Design and Participatory Design.” Creativity and Innovation Management 23 (2): 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12061.

- Dillon, N. 2022. From visibility to mattering. Crafts Council blog. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/insight-and-advocacy/research-library/visibility-mattering

- ENoLL. 2020. What are Living Labs. https://enoll.org/about-us/

- ESS. n.d. European Social Survey: Measuring Wellbeing. Europeans’ Wellbeing. http://www.esswellbeingmatters.org/measures/index.html

- Fancourt, D., and S. Finn. 2019. What is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- German, S. K 1994. “Surfacing: The Inevitable Rise of the Women of Color Quilters’ Network.” In Uncoverings 1993, edited by Laurel Horton, 137–168. San Francisco: American Quilt Study Group.

- Gudowska, B. 2020. “Arts and Crafts and UN Sustainable Development Goals.” International Journal of New Economics and Social Sciences 11 (1): 277–288. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0014.3547.

- Hennink, M. M. 2017. “Cross-Cultural Focus Group Discussions.” In A New Era in Focus Group Research, edited by Barbour, R., and Morgan, D. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-58614-8_4.

- Hewett, J. 2019. This Long Thread: Women of Color on Craft, Community, and Connection. Roost Books.

- Kovach, M. 2021. “Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts.” 2nd ed. University of Toronto Press

- Leone, L. (Ed.) 2020. Craft in Art Therapy: Diverse Approaches to the Transformative Power of Craft Materials and Methods. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Luckman, S. 2022. “Who Counts, and is Counted, in Craft?” European Journal of Cultural Studies 25 (3): 941–947. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211060352.

- Maker Stories. 2019. Maker Stories Episode 1 – Jasmine Carey. Craft Expertise and Maker Stories Podcast. https://maker-stories-podcast.simplecast.com/episodes/episode-1-jasmine-carey

- Maker Stories. 2020. Maker Stories Episode 4 – Pratima Kramer. Craft Expertise and Maker Stories Podcast. https://maker-stories-podcast.simplecast.com/episodes/episode-4-pratima-kramer-bVTRU3so

- Miles, A., and L. Gibson. 2016. “Editorial – Everyday Participation and Cultural Value.” Cultural Trends 25 (3): 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2016.1204043.

- PAHO. n.d. Healthy Life Course. Pan American Health Organisation. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/healthy-life-course

- Patel, K. 2021. Making Changes in Craft. Birmingham City University and Crafts Council.

- Patel, K. 2022. “I Want to Be Judged on my Work, I Don’t Want to Be Judged as a Person’: Inequality, Expertise and Cultural Value in UK Craft.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 25 (6): 1556–1571. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494221136619.

- Patel, K., and R. Dudrah. 2022. “Special Issue Introduction: Craft Economies and Inequalities.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 25 (6): 1549–1555. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494221136618.

- Patel, K. 2019. Supporting Diversity in Craft Practice through Digital Technology Skills Development, Crafts Council. https://craftexpertise.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Supporting-Diversity-in-Craft-Practice-report-March-2019.pdf

- Pickerill, J., Pottinger, L., Ehgartner, U., Barron, A., Browne, Ehgartner, and U. Hall. 2021. “Participatory Activist Research.” In Methods for Change: Impactful Social Science Methodologies for 21st Century Problems, edited by A. L. S. M., Pottinger, L. and Ritson, J. Manchester: Aspect and The University of Manchester.

- Pöllänen, S. H. 2015. “Crafts as Leisure-Based Coping: Craft Makers’ Descriptions of Their Stress-Reducing Activity.” Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 31 (2): 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2015.1024377.

- Posner, P. L. 2009. “The Pracademic: An Agenda for Re-Engaging Practitioners and Academics.” Public Budgeting & Finance 29 (1): 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5850.2009.00921.x.

- Pottinger, L., S. Phinney, S. M. Hall, A. L. Browne, and A. Barron. 2021. Methods for Change: Showcasing Innovative Social Science Methodologies. Aspect/University of Manchester, UK.

- Radclyffe-Thomas, N. 2014. “Is Creativity Lost in Translation? A Discussion of the Cultural Underpinnings of Creativity.” JOMEC 6. https://jomec.cardiffuniversitypress.org/articles/10.18573/j.2014.10284.

- Radclyffe-Thomas, N., M. Anjum, C. Currie, A. Roncha, and J. Bennett. 2023. “Wow, I did this!” Making Meaning through Craft: Disrupting the craft canon. Crafts Council. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/documents/2155/final_report2.pdf

- Sauer, S., and M. de Rijke. 2016. “Seeking Serendipity: A Living Lab Approach to Understanding Creative Retrieval in Broadcast Media Production.” SIGIR ‘16: Proceedings of the 39th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 989–992. https://doi.org/10.1145/2911451.2914721.

- Shuzhong, H., and L. Prott. 2013. “Survival, Revival and Continuance: The Menglian Weaving Revival Project.” International Journal of Cultural Property 20 (2): 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739113000052.

- Sinclair, R. 2020. How can the Craft World Address its Lack of Diversity? Crafts Council/Stories. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/stories/how-can-craft-world-address-its-lack-diversity

- Smith, L. T. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books.

- Spilsbury, M. 2018. Who Makes? An Analysis of People Working in Craft Occupations, Crafts Council. https://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/documents/892/Who_makes_2018.pdf

- Taylor, M. 2016. “Nonparticipation or Different Styles of Participation? Alternative Interpretations from Taking Part.” Cultural Trends 25 (3): 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2016.1204051.

- Thakkar, A. 2021. The Young Designers Shattering Stereotypes around Indian Fashion. iD-Vice 30. https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/4awwx9/young-indian-fashion-designers

- Tsot. n.d. The Shape of Things: Sharing the Impact. https://theshapeofthings.org.uk/downloads/tsot-sharing-the-impact.pdf

- Tsui, C. 2009. China Fashion: Conversations with Designers. Berg: Oxford, New York.

- Twigger Holroyd, A., and E. Shercliff. 2020. Stitching Together: Good Practice Guidelines: Advice for Facilitators of Participatory Textile Making Workshops and Projects. Bournemouth: Stitching Together. https://stitchingtogether.net/good-practice-guidelines/

- UNECE. 2018. Fashion and the SDGs: What Role for the UN? https://unece.org/DAM/RCM_Website/RFSD_2018_Side_event_sustainable_fashion.pdf

- van den Heuvel, R., S. Braun, M. de Bruin, and R. Daniëls. 2021. “A Closer Look at Living Labs and Higher Education Using a Scoping Review.” Technology Innovation Management Review 11 (9/10): 30–46. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1463.