ABSTRACT

Introduction

To date, there is solid evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) supporting the rationale for withdrawal from inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in most patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, the populations selected for RCTs only partially represent the real-life population of COPD patients.

Areas covered

In this review, a systematic synthesis of data useful in the daily clinical practice was provided in order to guide clinicians toward the optimal approach for the de-escalation of ICSs in COPD.

Expert opinion

De-escalation to ICS is a procedure that allows optimizing the pharmacological therapy of stable COPD patients. While only a minority of severe COPD patients that are symptomatic and/or at high risk of exacerbation may really need of triple therapy, most patients should be de-escalated/switched from ICS-containing regimen toward dual bronchodilator therapy, or even to single bronchodilator regimen in patients affected by less severe form of COPD.

1. Introduction

Bronchodilator therapy with a long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist (LABA) and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), administered alone or in combination, is the mainstay pharmacological approach to manage patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and it is always recommended as initial therapy as suggested by the current Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD 2020) [Citation1]. On the other hand, the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in COPD remains controversial, and oftentimes prescribed for symptomatic patients and/or subjects at high risk of COPD exacerbation [Citation1].

To date, there is solid evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) supporting the rationale for withdrawal from ICSs in most patients suffering from COPD [Citation2–9], with recent high-quality quantitative syntheses indicating that ICS discontinuation is a complex procedure that requires a well planned and tailored strategy [Citation10]. In this respect, another quantitative synthesis of RCTs attempted to provide guidance for ICS therapy and ICS de-escalation among patients with COPD [Citation11].

In any case, it is well known that the populations selected for RCTs only partially represent the real-life population, as it has been proved that in large populations of individuals with an established diagnosis of COPD fewer than ≃14% of outpatients were eligible for inclusion in RCTs [Citation12,Citation13]. In this respect, discrepancies were found between RCTs and real-life reports, the latter reporting that no differences in forced expiratory volume in the 1st second (FEV1) values and exacerbation rate were observed between patients who were and were not withdrawn from ICS treatment [Citation14]. Paradoxically, further discordance can be detected not only between RCTs and real-world studies but also among different RCTs with respect to the protective effect of ICS/LABA/LAMA combination compared to dual LABA/LAMA combination on the risk of COPD exacerbation [Citation15].

Indeed, it has been recognized that real-world findings have become critical to better characterize the efficacy and safety profile of pharmacological treatments, already shown to be efficacious and safe in RCTs, under conditions of heterogeneity in patients, treatment regimens, clinicians, and settings [Citation16].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to provide a systematic synthesis of data useful in the daily clinical practice to guide clinicians toward the optimal approach for the de-escalation of ICSs in COPD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Review question

Do real-world findings provide information for optimizing the de-escalation of ICSs in COPD patients?

2.2. Search strategy

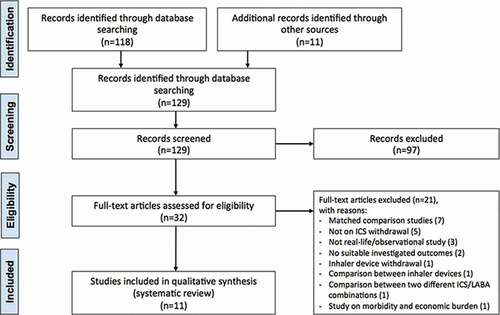

The protocol of this synthesis of the current literature has been submitted to the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO, submission ID: 182,837), and performed in agreement with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) [Citation17], with the relative flow diagram reported in . This study satisfied all the recommended items reported by the PRISMA-P checklist [Citation17].

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for the identification of real-world or observational studies included in the systematic review concerning optimizing ICS therapy in COPD. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonist; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

The PICO (Patient problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) framework was applied to develop the literature search strategy and question, as previously reported [Citation18]. Namely, the ‘Patient problem’ included COPD patients; the ‘Intervention’ regarded COPD therapy without the ICS; the ‘Comparison’ included COPD therapy including an ICS; the assessed ‘Outcomes’ were the lung function, dyspnea, quality of life (QoL), adverse respiratory symptoms, the risk and rate of COPD exacerbation, risk of serious pneumonia, risk of pneumonia, frequency of hospital admissions, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) deterioration, exercise performance, and safety profile. The definition of COPD exacerbation reported in the studies is shown in .

Table 1. Definition of COPD exacerbations as reported by the studies included in the systematic review

A comprehensive literature search was performed for real-world or observational studies written in English and evaluating the impact of ICS discontinuation in COPD patients. The search was performed in MEDLINE, ClinicalTrials.gov, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, EU Clinical Trials Register, Scopus, and Web of Science, in order to provide for relevant studies published up to 5 May, 2020. The research string was as follows: (withdrawal OR de-escalation OR optimization OR switch) AND ((real-life) OR (real-world) OR observational OR (clinical practice)) AND COPD AND (ICS OR corticosteroid OR glucocorticoid). As an example, reports the literature search terms used for OVID MEDLINE.

Table 2. Literature search terms used for OVID MEDLINE. The final search strategy applied to conduct this systematic review is reported at steps #29, #30, and #31

Citations of previous published reviews were checked to select further pertinent studies, if any [Citation14,Citation15,Citation20–23].

Studies reporting the impact of ICS discontinuation on lung function, dyspnea, QoL, exacerbations, treatment failure, pneumonia, hospital admissions, AHR deterioration, and safety were included in this systematic review.

Two reviewers independently checked the examined studies, which were selected in agreement with previously mentioned criteria, and any difference in opinion about eligibility was resolved by consensus.

2.3. Data extraction

Data from included studies were extracted and checked for study references, NCT or study number identifier, study duration, treatments at baseline and during the study period with doses and regimen of administration when reported, patient characteristics and number of analyzed patients, age, gender, smoking habit, duration of inhaled steroid use prior to study entry, baseline number of exacerbations in the year preceding the study, FEV1, COPD exacerbations, serious pneumonia, acute respiratory events, Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI) score, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score, Medical Research Council (MRC) score, COPD assessment test (CAT) score, clinical COPD questionnaire (CCQ) score, hospital admissions, AHR deterioration, all-cause mortality, and severe adverse events (SAEs).

2.4. Outcomes

The co-primary outcomes of this systematic review were the impact of COPD therapy without the ICS on FEV1, SGRQ, TDI, on the risk and rate of COPD exacerbations, MRC score, CAT score, CCQ score, AHR deterioration, hospital admissions, risk of acute respiratory events, risk of all-cause mortality, risk of pneumonia, and SAEs.

2.5. Strategy for data synthesis

Data from original papers were extracted and reported via qualitative synthesis.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

A total of eleven real-world or observational studies performed on COPD patients were identified and their characteristics are summarized in . Eight studies investigated withdrawal of ICS [Citation24–31] and three studies evaluated the impact of a switch from baseline therapies including ICS-containing bronchodilator regimens to dual bronchodilation [Citation32–34].

Table 3. Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review

summarizes the results of studies in which the effect of de-escalation of ICSs has been assessed.

Table 4. Studies included in the systematic review in which ICS withdrawal was significantly superior ↑, similar ≈, or inferior ↓ to ICS continuation

3.2. From ICS-containing regimen to ICS discontinuation

A subgroup analysis of the prospective, longitudinal non-interventional DACCORD study (EUPAS4207) [Citation30] investigated the long-term effects of ICS withdrawal in real-world clinical settings in terms of exacerbations and health status. For the duration of 2 years of follow-up, the study included COPD patients treated with ICS-containing regimen who continued to receive ICS, and patients who had ICS withdrawn by the treating physician prior to entering DACCORD study. Of 1,365 analyzed patients, 1,022 continued treatment with ICS, whereas 236 patients were withdrawn of ICS. There were few differences with respect to baseline characteristics and disease characteristics. ICS-withdrawn group had a significantly (P < 0.05) shorter disease duration of less than one year since diagnosis, compared to ICS continued group (25.0% vs. 12.7%) and a better lung function (FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted: 29.2% vs. 15.4%), thus representing potential real-world confounders. On the other hand, no clinically relevant differences were detected in terms of baseline symptoms or health status between ICS withdrawn and ICS continued groups (P > 0.05). The number of non-exacerbating patients during the 6 months prior to study entry was higher in the ICS-withdrawn group, compared to the ICS continued group (74.2% vs. 70.7%). In the first year of follow up, the annualized exacerbation rate was similar (P > 0.05) between the two groups, whereas in the second year, ICS-withdrawn group reached a significantly lower rate compared to the group that continued treatment with ICS (0.237 vs. 0.402). In both groups, CAT total score was significantly (P < 0.05) improved from baseline, although a greater reduction was reached in the ICS-withdrawn group, compared to those whom continued to take ICS (−4.0 ± 6.4 units and −1.5 ± 6.2 units, respectively).

A non-interventional cohort analysis evaluated the status of ICS prescriptions following the 2017 GOLD revision by using data of patients included in the three large multicenter COPD cohorts in Korea: the Korean Obstructive Lung Disease (KOLD) 1 and 2, as well as the Korea Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorders Subgroup Study (KOCOSS) [Citation31]. Patients that before or at the time of enrollment were treated with an ICS-containing regimen were defined as baseline ICS users, whereas patients using non-ICS-containing regimens including LABA, LAMA, or LABA/LAMA combination, were defined as ICS nonusers. A total of 1,144 patients were eligible to be included in this study. In 2014, 46.3% of the patients were ICS users, and triple therapy was the most frequently used regimen, followed by LAMA monotherapy and ICS/LABA. This percentage decreased to 38.8% of patients in 2017, whereas LAMA/LABA combination became the most frequently used treatment regimen. Interestingly, 47.5% of patients that in 2017 were using ICS-containing regimens, did not exhibit features characteristic of ICS usage, such as history of asthma, blood eosinophilia, and more than two exacerbations in the year prior to enrollment. A significantly (P < 0.01) greater number of patients in the ICS-withdrawn group had a history of asthma in the year prior to enrollment, compared to the ICS continued group (56.6% and 41.0%, respectively) and a higher annual exacerbation frequency (0.79 vs. 0.53). During the follow-up period, the annual exacerbation rate was comparable (P > 0.05) between ICS withdrawn and ICS continued group (0.48 vs. 0.47), although the annual rate of severe exacerbation was significantly (P < 0.05) higher for the ICS-withdrawn group (0.22 vs. 0.12), with RR 1.74 (95% CI 1.05–2.88).

An 8-week observational study of the run-in phase of the Inhaled Steroids in Obstructive Lung Disease (ISOLDE) trial [Citation27] evaluated the impact of ICS discontinuation in stable COPD patients previously treated with ICS-containing regimens. A total of 272 COPD patients were analyzed and at study entry, 160 (59.0%) stopped regular treatment with ICS at their own discretion, whereas 112 patients remained chronically untreated with ICS. In the year prior to study entry, exacerbating patients in the ICS-withdrawn group were administered with a greater ICS daily dose compared to those that had no exacerbations; however, this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Fifty-six patients that discontinued ICS experienced at least one COPD exacerbation in the year before the study entry. At the end of the study 60 patients that were withdrawn from ICS experienced at least one exacerbation. In these patients ICS discontinuation elicited a significant (P < 0.001) increase in the risk of COPD exacerbation (RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.87–2.65).

A large primary care population-based cohort study [Citation24] evaluated the impact of ICS withdrawal on the risk of moderate and/or severe exacerbations and all-cause mortality in COPD patients selected from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) in the United Kingdom. A total of 48,157 patients were selected between 1 January 2005 and 31 January 2014. Patients were divided into two groups, continuous ICS users and ICS withdrawals, the former received their most recent ICS prescription within 3 months before the start of a fixed 90-days interval of follow-up, the latter discontinued ICS for more than 3 months. All patients were further stratified by absolute eosinophil count (using 340 cells/μL as cutoff value) or relative eosinophil count (using 4.0% as cutoff value). ICS discontinuation did not increase neither the risk of moderate-to-severe exacerbation nor the risk of severe exacerbations in patients with absolute blood eosinophil ≥340 cells/μL (adjusted HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.61–1.10) or relative count ≥4.0% (adjusted HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.61–1.04). No increased risk of all-cause mortality was observed among subjects who withdrew from ICS irrespective of elevated absolute (adjusted HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.96–1.22) or high blood eosinophil counts (adjusted HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.97–1.21).

A prospective, open-label study [Citation25] carried out in clinical practice settings investigated the impact of prophylactic ICS discontinuation on adverse respiratory outcomes, defined as occurrence of acute COPD exacerbation or an episode of unremitting worsening of respiratory symptoms for at least three consecutive days. A total of 229 COPD patients were selected and based on ICS dosage used in treatment regimens, all entered a steroid washout period of three months. At baseline, 201 subjects were included in the study. Overall, the probability of having adverse respiratory events due to ICS withdrawal was 0.37 (95% CI 0.31–0.44). Analysis according to baseline dosage of ICS showed that in the low, intermediate, and high steroid subgroups, this probability was 0.29 (95% CI 0.15–0.43), 0.39 (95% CI 0.30–0.48), and 0.39 (95% CI 0.26–0.52), respectively. Survival analysis indicated that the risk of adverse respiratory outcome was higher for females than for males with an adjusted HR of 2.14 (95% CI 1.31–3.50), and the risk increased with increasing age, with an HR of 1.05 (95% CI 1.02–1.08) per year lived. However, survival analysis performed for baseline inhaled steroid dosage subgroups indicated that age, gender, smoking status, and reversibility airflow limitation were independent predictors for adverse respiratory outcomes in one or more subgroups identified by baseline dosage of inhaled steroids. The risk of adverse respiratory outcome was higher in smoking patients from the intermediate dosage steroid subgroup compared to nonsmokers (HR 2.05 [95% CI 1.07–3.93]), and in patients from the high steroid dosage subgroup showing a greater bronchodilator reversibility (HR 3.21 [95% CI 1.28–8.05]).

In an observational, real-world study [Citation26], COPD patients were identified by using the computerized Quebec health insurance databases who received at least one prescription for a respiratory medication and ICSs, between 1990 and 2005. The base cohort included patients with at least three prescriptions for a respiratory medication in any 1 year and on at least two different dates, and the study cohort was defined by patients from the base cohort who started treatment with ICS at the third-cohort defining prescription or after. Patients were followed through 2007 or until a serious pneumonia event, defined as a first hospitalization for or death from pneumonia. A nested case–control analysis of the cohort was used to estimate the rate ratio of serious pneumonia associated with discontinuation of ICS use compared with continued use, adjusted for age, sex, respiratory disease severity, and comorbidity. The study cohort comprised 103,386 new ICS-users, of whom 14,020 were hospitalized for a serious pneumonia and matched with control subjects from the cohort risk sets, and 69.7% of control group discontinued ICS use. ICS discontinuation was associated with a reduction of 37.0% in the risk of serious pneumonia (relative risk [RR] 0.63, 95% CI 0.60–0.66), and produced a pneumonia risk reduction that increased from 20.0% by the first month to 50.0% by the fourth month, and then stabilized. Risk reduction was particularly pronounced with discontinuation of fluticasone (FP) (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.54–0.61) and less with budesonide (BUD) (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78–0.97).

3.3. From ICS/LABA/LAMA combination to LABA/LAMA combination

A subgroup analysis of the non-interventional, longitudinal, prospective DACCORD study [Citation34] evaluated patients with COPD that at baseline were receiving triple therapy, and all patients were directly switched to treatment with indacaterol (IND)/glycopryrronium (GLY) for one year. Of the 975 patients analyzed, 377 were included in the subgroup formerly treated with ICS/LABA/LAMA combination, and 191 completed the study. A similar proportion of patients exacerbated was detected during the 6 months before recruitment and over the 1-year follow-up, with an annualized exacerbation rate of 0.26 (95% CI 0.19–0.37). At 1-year follow-up, a significant (P < 0.05) improvement in CAT score was detected in 52.4% of patients who switched from triple therapy (from 18.0 ± 7.7 units to 16.2 ± 7.4 units) [Citation34].

3.4. From ICS/LABA combination to LABA/LAMA combination

A subgroup analysis of the non-interventional, longitudinal, prospective DACCORD study [Citation34] evaluated patients with COPD that at baseline were receiving ICS/LABA combination, and all patients were directly switched to treatment with IND/GLY for one year. Of the 975 patients analyzed, 598 were included in the subgroup formerly treated with ICS/LABA combination, and 396 completed the study. While about one-third of the patients experienced at least one exacerbation during the 6 months before recruitment, fewer than 15% exacerbated during the 1-year follow-up period, with an annualized exacerbation rate of 0.21 (95% CI 0.15–0.28). At 1-year follow-up, a significant (P < 0.05) improvement in CAT score was induced in 71.0% of patients who switched from ICS/LABA combination (from 21.2 ± 7.1 units to 17.4 ± 6.4 units).

A post hoc analysis of the interventional, prospective, multicenter, randomized, open-label CRYSTAL study (NCT01985334) [Citation32,Citation35] evaluated the efficacy of a direct switch to treatment with IND/GLY 110/50 μg fixed-dose combination (FDC) in patients with moderate COPD and modified MRC (mMRC)≥1, from a baseline maintenance treatment with the combination of ICS and a LABA for 3 months and without any washout period, thus mimicking routine clinical settings. The main outcome was the assessment of clinically important deterioration (CID), and the three definitions used (D1, D2, and D3) for CID included: a reduction of ≥100 mL in trough FEV1; a decrease of ≥1 point in TDI and/or an increase of ≥0.4 points in CCQ score; an acute moderate or severe exacerbation. In the definitions D1 and D2, either TDI or CCQ was evaluated along with FEV1 and acute exacerbation, whereas, in definition D3, all four parameters were included. Of the 1080 patients analyzed, 811 switched to IND/GLY 110/50 μg; thus, 269 patients continued with former ICS/LABA maintenance therapy. IND/GLY 110/50 μg reduced the risk of CID compared to patients that continued treatment with ICS/LABA, according to the CID definitions D1 (odds ratio [OR] 0.76, 95% CI 0.56–1.02), D2 (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.56–1.00), and being significant (P < 0.05) for D3 (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.51–0.89). IND/GLY 110/50 μg induced a lower number of patients to experience a worsening of trough FEV1, TDI, and CCQ compared to ICS/LABA, and significantly (P < 0.05) prevented FEV1 decline (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.47–0.93), but there was no difference in the decrease of TDI, CCQ, and exacerbations.

The Prospective cohort study for the real-life effectiveness evaluation of glycopyrronium with indacaterol combination in the management of COPD in Canada (POWER) study [Citation33,Citation36] was a real-world, multicenter, prospective, interventional trial (NCT02202616) that enrolled patients with moderate to severe COPD. At randomization, COPD patients were instructed to interrupt and directly switch from the ongoing maintenance therapy with FP/salmeterol (SAL) FDC with any dose and device, to receive open-label maintenance treatment with IND/GLY 110/50 μg twice daily for 4 months. Switch to IND/GLY 110/50 μg significantly (P < 0.05) increased the change from baseline in trough FEV1 by 172 mL (95% CI 85–258), improved the TDI total score by 2.9 units (95% CI 2.15–3.57), as well as the CAT score by −8.2 units (95% CI −10.0 – −6.4, respectively). IND/GLY 110/50 μg was well tolerated, with a frequency of SAEs of 7.9%, and patients reporting pneumonia adverse events (AEs) and SAEs were frequent (5.0% and 3.0%, respectively).

3.5. From ICS/LABA combination to single or dual bronchodilator therapy

The real-world, prospective study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO) [Citation29] investigated whether withdrawal of ICS in patients regularly administered with ICS/LABA combination in the previous year, was linked to a worsening in lung function and symptoms and to a higher exacerbation frequency. Of the 914 enrolled patients, 816 concluded the study 6 months later, and specifically, 482 (59.0%) continued to receive an ICS-containing treatment regimen and 334 (41.0%) were withdrawn of ICS by mainly switching to regular therapy with long-acting bronchodilators. ICS continued group had a significantly (P < 0.001) greater number of patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, compared to ICS-withdrawn group (64.0% vs. 52.0%), with no significant difference (P > 0.05) in respect to obesity, gastric reflux, and diabetes. At the end of the study period, FEV1 and CAT scores were similar between patients who switched to long-acting bronchodilators and who continued ICS treatment. Similarly, no significant (P > 0.05) difference was detected in exacerbations history between the two groups, 141 patients (29.0%) and 88 patients (26.0%) exacerbated in the group treated with ICS and without ICS, respectively. In all, 173 exacerbations were reported in the ICS group and 112 in the ICS-withdrawn group, with an exacerbation rate of 0.37 and 0.34 per patient, during the study period. Hospital admissions appeared to be numerically more frequent in the ICS continued group than in the ICS-withdrawn group: 15 (3.1%) vs. 5 (1.8%).

3.6. ICS discontinuation or reduction of ICS use from ICS/LABA combination

A follow-up analysis of the first part of the interventional Groningen and Leiden Universities Corticosteroids in Obstructive Lung Disease (GLUCOLD) trial (NCT00158847) [Citation28,Citation37] investigated whether ICS treatment discontinuation induced a relapse in COPD patients, even after chronic use. A total of 114 moderate to severe COPD patients enrolled in the first part of the GLUCOLD study (GL1) terminated the randomized 6-month or 30-month treatment with FP (FP6 or FP30), the 30-month treatment with FP/SAL (FP/SAL30), or placebo. For the subsequent 5 years of follow-up, patients were prospectively followed by their physician and monitored with respect to lung function, AHR, and QoL. Overall, 79 patients were included in the follow-up study and 58 completed it. Patients using ICSs from 0.0% to 50.0% of the time during the follow-up had a significantly (P < 0.05) faster worsening in FEV1 compared to patients that during GL1 were treated with FP/SAL30 (−68 mL/year, 95% CI −112 – −25) or FP30 (−73 mL/year, 95% CI −119 – −26). FEV1 worsening was even more pronounced (P < 0.05) in patients not using ICSs during the follow-up, compared to GL1 groups FP/SAL30 (−106 mL/year, 95% CI −171 – −41) or FP30 (−84 mL/year, 95% CI −149 – −18). During follow-up, ICS withdrawal in GL1 FP/SAL30 and FP30 groups produced a deterioration in AHR and QoL, with a significant (P < 0.05) worsening of MRC dyspnea score by 0.2 points/year (95% CI 0.06–0.3), SGRQ total score by 2.5 points/year (95% CI 0.2–4.7), CCQ total score by 0.1 points/year (95% CI 0.008–0.2), and CCQ symptom score by 0.2 points/year (95% CI 0.05–0.3).

4. Conclusion

Real-world studies support previous findings from RCTs [Citation38] and suggest that de-escalation of ICSs is a suitable and safe procedure in most COPD patients. Generally, withdrawal of ICS supported by an adequate pharmacological management of COPD does not increase or may even reduce the risk of exacerbation as well as improve lung function, dyspnea, and symptoms. De-escalation of ICS also reduces the risk of pneumonia.

Personalized approach is mandatory in the use of ICS in COPD, and withdrawal of ICS should be always considered in patients with no clear indication as reported by the current European Respiratory Society (ERS) guideline [Citation39], recommending to withdraw ICS in COPD patients without a history of frequent exacerbations that, instead, should be treated with one or two long-acting bronchodilator agents.

5. Expert opinion

Real-world reports provide useful information for optimizing the de-escalation of ICSs in COPD patients. Specifically, when the discontinuation of ICS is followed by a correct pharmacological treatment of COPD with bronchodilator agents, no worsening in the risk of exacerbation, FEV1, TDI, CAT, and CCQ scores can be detected. Unexpectedly, we have found that ICS discontinuation from ICS-containing regimen may even reduce the risk of exacerbation, as well as the switch from ICS/LABA combination to LABA/LAMA combination reduces the risk of exacerbation and increases FEV1.

Nevertheless, some of the real-world studies included in this systematic review reported negative outcomes for the risk of exacerbation, FEV1, AHR deterioration, SGRQ, CCQ and MRC scores after discontinuation of ICS therapy in COPD. However, such detrimental effects were detected in an old study [Citation27] in which the ICS therapy was withdrawn at own discretion of patients with no support by clinicians, or in another study [Citation28,Citation37] in which the use of ICS was discontinued or reduced due to the scarce or no adherence to ICS-containing therapy in COPD patients after the end of a RCT. Interestingly, these findings clearly demonstrate that ICS therapy lacks sustained disease-modifying effect after treatment cessation, and that ICS discontinuation must be followed by a well-planned therapeutic strategy to optimize the pharmacological management of COPD. Moreover, we cannot omit that ICS cessation may increase specifically the risk of severe exacerbation, as documented in a recent real-world study [Citation31].

Another unexpected finding is that de-escalation from triple therapy to dual bronchodilation therapy did not modulate the risk of exacerbation. Indeed, this data is in contrast with the current quantitative synthesis of literature originated from RCTs, indicating that in COPD patients treated with ICS/LABA/LAMA combination the risk of exacerbation is significantly reduced when compared with LABA/LAMA combination, especially in patients with blood eosinophil counts ≥300 cells/µL [Citation40]. Such a discrepancy could be explained by considering that most COPD patients treated in real-world with ICS/LABA/LAMA combination do not really need triple combination therapy to manage stable COPD [Citation21,Citation41]. Overall, in daily clinical practice, the most popular treatment pathways leading to an inevitable drift to triple therapy have been demonstrated to be ICS plus LABA → ICS plus LABA plus LAMA, triple therapy as first prescription, and ICS → ICS plus LABA → ICS plus LABA plus LAMA [Citation41].

However, even assuming that patients treated with triple therapy could have some benefits from the maximization of the therapeutic armamentarium via inhalation, we have to highlight that ICS/LABA/LAMA combination did not reach the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) over LABA/LAMA combination with respect to the improvement in both exacerbation and lung function [Citation40]. Thus, we can speculate that the limited superiority of triple combination over dual bronchodilation therapy detectable in RCTs could be not recorded by real-world studies, that are recognized to be less accurate than well-designed RCTs [Citation42].

Real-world data suggest discontinuing ICS by switching from ICS/LABA combination to LABA/LAMA combination, or even to de-escalate toward single bronchodilation therapy. This finding is partially in contrast with the current GOLD (2020) recommendations [Citation1], that suggest exclusively to switch from ICS/LABA combination to dual bronchodilation therapy and not to de-escalate to a LABA or a LAMA administered as monotherapy. The rationale for the switch suggested by GOLD recommendations [Citation1] is based on evidence raised from RCTs concerning the inappropriateness of ICS therapy, the lack of response to ICS treatment, or ICS-related AEs warranting discontinuation. Certainly, ICS/LABA combination is recommended for the initiation therapy just in a small percentage of symptomatic COPD patients that are at high risk of exacerbation with blood eosinophil counts ≥300 cells/μl, whereas most COPD patients are prescribed an ICS/LABA as first-line maintenance therapy worldwide [Citation43]. Thus, this systematic review provides the real-world rationale not only for switching to LABA/LAMA combination but also for de-escalating to single bronchodilation therapy in agreement with eosinophil levels and disease severity.

However, generally, the level of blood eosinophils of patients included in real-world studies is not taken into account as eosinophil counts are not routinely collected as part of diagnosis of COPD. On the other hand, when data on eosinophils are reported in real world-studies, physicians have usually requested for eosinophil count due to a specific purpose regardless of COPD, and thus this information may introduce potential bias [Citation24]. The lack of information on eosinophil blood count in real-world studies represents the main weakness of this systematic review to definitely guide the challenging de-escalation process of ICS in COPD. Therefore, there is the unmet need of well-designed further real-world studies in which data on eosinophils are adequately and systematically collected in the databases, a condition that could be satisfied probably only by collecting the records of patients attending university hospitals.

Finally, also the findings of real-world studies support the evidence from RCTs [Citation40] that ICS may increase the occurrence of respiratory infections, as ICS discontinuation significantly reduced the risk of severe pneumonia in COPD patients. Of course, it could be argued that also dual bronchodilation therapy may have specific safety matters, namely the occurrence of cardiovascular events [Citation44]. However, some dual bronchodilation therapies such as tiotropium/olodaterol FDC are characterized by an extremely favorable cardiovascular safety profile relative to other LABA/LAMA FDCs [Citation45], with no increase in the risk of specific cardiovascular SAEs, namely arrhythmia, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

On the other hand, although data on the influence of ICS on mortality are still scarce from real-world studies, both the ETHOS [Citation46] and the IMPACT [Citation47] RCTs, and a recent post hoc analysis of the IMPACT study [Citation48] reported that the presence of an ICS in the formulation significantly (P < 0.0) reduces the risk of death from any causes in COPD patients. Interestingly, in the ETHOS [Citation46] study, the only RCT that investigated two different doses of ICS in the same triple combination, the reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality was ICS dose-dependent [Citation46]. Indeed, these evidences come from studies [Citation46,Citation47,Citation47,Citation48] not specifically designed to assess the impact of ICS on mortality in COPD as a primary endpoint; however, they prospectively support a survival benefit with ICS-containing therapy that had previously been suggested in patients with COPD [Citation49–51].

As suggested by the current recommendations [Citation1], withdrawal of ICS is a procedure that should be undertaken under close medical supervision and that may optimize the pharmacological therapy of stable COPD patients. While only a minority of severe COPD patients that are symptomatic and/or at high risk of exacerbation may really need triple therapy, most patients should be de-escalated/switched from ICS-containing regimen toward LABA/LAMA FDC therapy, or even to single bronchodilation therapy in patients affected by less severe form of disease.

In this respect, interestingly the WISDOM study [Citation2], the only RCT that was properly designed to address the question of ICS withdrawal in patients treated with triple therapy, reported that in severe COPD patients receiving TIO plus SAL because of severity and increased risk of exacerbations, the risk of moderate or severe exacerbation was similar among those patients who discontinued or continued ICS therapy. Moreover, the INSTEAD RCT [Citation8] showed that moderate COPD patients who did not experience exacerbation in the previous year can be switched from FP/SAL combination to IND with no efficacy loss or adverse events.

Besides the typical limitations of real-world studies such as potential misdiagnosis and inaccuracy of recordkeeping [Citation52], the main limitation of this systematic review, and overall of the current recommendations [Citation1] and guidelines [Citation39], is represented by the lack of specific studies on ICS withdrawal including patients who had previously shown to require addition of ICS and benefitted from ICS.

In any case, the findings originated from this systematic review focused on real-world reports may represent a complementary integration of the recent ERS guidelines [Citation39] on the withdrawal of ICS in COPD that, conversely, was drawn up by considering exclusively evidence from RCTs.

Article highlights

Data from RCTs support the rationale for de-escalating to ICS in most COPD patients.

The populations selected for RCTs only partially represent the real-life population of COPD patients.

Real-world studies provide the findings that withdrawal of ICS is a suitable and safe procedure in most COPD patients.

When ICS discontinuation is performed in the right patient and followed by an adequate pharmacological management of COPD, the clinical and functional conditions of patients are not affected.

De-escalation of ICS may even reduce the risk of exacerbation as well as improve lung function, dyspnea, and symptoms.

De-escalation of ICS reduces the risk of pneumonia.

Declaration of interest

P. Rogliani has participated as a lecturer and advisor in scientific meetings and courses under the sponsorship of Almirall, AstraZeneca, Biofutura, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Farmaceutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini Group, Mundipharma, and Novartis, and has been funded by Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Novartis and Zambon. M. Cazzola has participated as a faculty member, and advisor in scientific meetings and courses under the sponsorship of Almirall, AstraZeneca, Biofutura, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Farmaceutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini Group, Lallemand, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Verona Pharma, and Zambon, and is or has been a consultant to ABC Farmaceutici, AstraZeneca, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Edmond Pharma, Lallemand, Novartis, Ockham Biotech, Verona Pharma, and Zambon, and has been funded by Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Zambon. L. Calzetta has participated as an advisor in scientific meetings under the sponsorship of Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis, received non-financial support from AstraZeneca, a research grant partially funded by Chiesi Farmaceutici, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis and Almirall, and is or has been a consultant to ABC Farmaceutici, Recipharm, Zambon, Verona Pharma and Ockham Biotech, and has been funded by Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Novartis, and Zambon. All other authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

One reviewer has declared lecture fees and/or consulting for Alfasigma, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, BI, GSK, Merck, Novartis, Zambon, Verona Pharma. All other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- GOLD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD – 2020 report; 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 22]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/GOLD-2020-FINAL-ver1.2-03Dec19_WMV.pdf

- Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1285–1294.

- Choudhury AB, Dawson CM, Kilvington HE, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in people with COPD in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Respir Res. 2007;8:93.

- Wouters EF, Postma DS, Fokkens B, et al. Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD causes immediate and sustained disease deterioration: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2005;60(6):480–487. .

- van der Valk P, Monninkhof E, van der Palen J, et al. Effect of discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the COPE study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1358–1363.

- O’Brien A, Russo-Magno P, Karki A, et al. Effects of withdrawal of inhaled steroids in men with severe irreversible airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(3):365–371.

- Rodriguez-Roisin R, Tetzlaff K, Watz H, et al. Daily home-based spirometry during withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroid in severe to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1973–1981.

- Rossi A, van der Molen T, Del Olmo R, et al. INSTEAD: a randomised switch trial of indacaterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in moderate COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1548–1556.

- Chapman KR, Hurst JR, Frent SM, et al. Long-term triple therapy de-escalation to indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SUNSET): a randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(3):329–339.

- Calzetta L, Matera MG, Braido F, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a meta-analysis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:148–158.

- Oshagbemi OA, Odiba JO, Daniel A, et al. Absolute blood eosinophil counts to guide inhaled corticosteroids therapy among patients with COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(16):1670–1679.

- Scichilone N, Basile M, Battaglia S, et al. What proportion of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease outpatients is eligible for inclusion in randomized clinical trials? Respiration. 2014;87(1):11–17.

- Travers J, Marsh S, Caldwell B, et al. External validity of randomized controlled trials in COPD. Respir Med. 2007;101(6):1313–1320. .

- Ye W, Guo X, Yang T, et al. Systematic review of inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal effects in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and comparison with two “real-life” studies. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(7):4565–4573.

- Anzueto A, Kaplan A. Dual bronchodilators in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence from randomized controlled trials and real-world studies. Respir Med. 2020;2:100016.

- Bernstein JA, Kavati A, Tharp MD, et al. Effectiveness of omalizumab in adolescent and adult patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review of ‘real-world’ evidence. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(4):425–448.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

- Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16.

- Rothnie KJ, Mullerova H, Hurst JR, et al. Validation of the recording of acute exacerbations of COPD in UK primary care electronic healthcare records. PloS One. 2016;11(3):e0151357.

- Harries TH, Rowland V, Corrigan CJ, et al. Blood eosinophil count, a marker of inhaled corticosteroid effectiveness in preventing COPD exacerbations in post-hoc RCT and observational studies: systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):3.

- Cataldo D, Derom E, Liistro G, et al. Overuse of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: five questions for withdrawal in daily practice. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:2089–2099.

- Avdeev S, Aisanov Z, Arkhipov V, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD patients: rationale and algorithms. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:1267–1280.

- Kaplan AG. Applying the wisdom of stepping down inhaled corticosteroids in patients with COPD: a proposed algorithm for clinical practice. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2535–2548.

- Oshagbemi OA, Franssen FME, van Kraaij S, et al. Blood eosinophil counts, withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids and risk of COPD exacerbations and mortality in the clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). Copd. 2019;16(2):152–159.

- Schermer TR, Hendriks AJ, Chavannes NH, et al. Probability and determinants of relapse after discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with COPD treated in general practice. Primary Care Respir J. 2004;13(1):48–55.

- Suissa S, Coulombe J, Ernst P. Discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk reduction of pneumonia. Chest. 2015;148(5):1177–1183. .

- Jarad NA, Wedzicha JA, Burge PS, et al. An observational study of inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. ISOLDE study group. Respir Med. 1999;93(3):161–166.

- Kunz LIZ, Postma DS, Klooster K, et al. Relapse in FEV1 decline after steroid withdrawal in COPD. Chest. 2015;148(2):389–396.

- Rossi A, Guerriero M, Corrado A. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res. 2014;15(1):77.

- Vogelmeier C, Worth H, Buhl R, et al. “Real-life” inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in COPD: a subgroup analysis of DACCORD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:487–494.

- Lee SH, Lee JH, Yoon HI, et al. Change in inhaled corticosteroid treatment and COPD exacerbations: an analysis of real-world data from the KOLD/KOCOSS cohorts. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):62. .

- Greulich T, Kostikas K, Gaga M, et al. Indacaterol/glycopyrronium reduces the risk of clinically important deterioration after direct switch from baseline therapies in patients with moderate COPD: a post hoc analysis of the CRYSTAL study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1229–1237.

- Kaplan A, Chapman KR, Anees SM, et al. Real-life effectiveness of indacaterol-glycopyrronium after switching from tiotropium or salmeterol/fluticasone therapy in patients with symptomatic COPD: the POWER study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:249–260.

- Worth H, Buhl R, C-P C, et al. GOLD 2017 treatment pathways in ‘real life’: an analysis of the DACCORD observational study. Respir Med. 2017;131:77–84.

- NCT01985334. Study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of glycopyrronium or indacaterol maleate and glycopyrronium bromide fixed-dose combination regarding symptoms and health status in patients with moderate COPD switching from treatment with any standard COPD regimen; 2013 [cited 2020 May 10]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01985334

- NCT02202616. Prospective cohort study for the real - life effectiveness evaluation of GlycOpyrronium with IndacatERol combination in the management of COPD in Canada (POWER Study) (POWER); 2014 [cited 2020 May 10]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02202616

- NCT00158847. Modification of disease outcome in COPD; 2005 [cited 2020 May 10]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00158847

- Cazzola M, Rogliani P, Matera MG. Escalation and De-escalation of Therapy in COPD: myths, realities and perspectives. Drugs. 2015;75(14):1575–1585.

- Chalmers JD, Laska IF, Franssen FME, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a European respiratory society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000351.

- Cazzola M, Rogliani P, Calzetta L, et al. Triple therapy versus single and dual long-acting bronchodilator therapy in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(6):1801586.

- Brusselle G, Price D, Gruffydd-Jones K, et al. The inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UK. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207–2217.

- Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018;35(11):1763–1774.

- Calzetta L, Ritondo BL, Matera MG, et al. Evaluation of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol for the treatment of COPD: a systematic review. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020;14(6):621–635. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2020.1743180

- Calzetta L, Cazzola M, Matera MG, et al. Adding a LAMA to ICS/LABA therapy: a meta-analysis of triple combination therapy in COPD. Chest. 2019;155(4):758–770.

- Rogliani P, Matera MG, Ritondo BL, et al. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety profile of dual bronchodilation therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a bidimensional comparative analysis across fixed-dose combinations. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2019;59:101841.

- Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Ferguson GT, et al. Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in moderate-to-very-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):35–48.

- Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1671–1680.

- Lipson DA, Crim C, Criner GJ, et al. Reduction in all-cause mortality with fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1508–1516. .

- Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Cardiovascular events in patients with COPD: TORCH study results. Thorax. 2010;65(8):719–725.

- Wedzicha JA, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, et al. The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):19–26. .

- Vestbo J, Anderson JA, Brook RD, et al. Fluticasone furoate and vilanterol and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with heightened cardiovascular risk (SUMMIT): a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1817–1826.

- Rogliani P, Cazzola M, Calzetta L. Cardiovascular disease in chronic respiratory disorders and beyond. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(17):2178–2180.