ABSTRACT

Background

Benchmarking regulatory systems of low- and middle-income countries with mature systems provides an opportunity to identify gaps, enhance review quality, and reduce registration timelines, thereby improving patients’ access to medicines. The aim of this study was to compare the medicines registration process of the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe (MCAZ) with the regulatory processes in Australia, Canada, Singapore, and Switzerland.

Methods

A questionnaire that standardizes the review process, allowing key milestones, activities and practices of the five regulatory authorities was completed by a senior member of the divisions responsible for issuing marketing authorizations.

Results

The MCAZ has far fewer resources than the regulatory authorities in the comparator countries, but employs three review models, which is in line with international best practice. The MCAZ registration process is similar to the comparator countries in key milestones monitored, but differs in the target timelines for these milestones. The MCAZ is comparable to the comparator authorities in implementing the majority of good review practices, although it significantly lags behind in transparency and communication.

Conclusion

This study identified the MCAZ strengths and opportunities for improvement, which if implemented, will enable the achievement of its vision to be a leading regulatory authority in Africa.

1. Background

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3) ‘to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’ [Citation1] is supported by the regulation of medicines, which ensures that medicines and medical products, made available to the public, are quality- assured, safe and effective [Citation2,Citation3]. One of the targets for SDG 3 is universal health coverage by 2030. This can be defined as access to essential health services, including prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care for all people, regardless of financial standing [Citation4,Citation5], and medicine regulatory authorities are a pivotal component of the healthcare system [Citation6].

Currently, many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have regulatory systems that need strengthening [Citation3,Citation7], and and this results in backlogs of applications for marketing authorization. These challenges affect timely access to quality assured medicines and healthcare delivery. Effective regulation of medicines reduces the costs incurred by patients and the healthcare delivery system due to undesirable outcomes such as adverse reactions caused by the use of unsafe medicines and treatment failure or the development of resistance due to the use of unregistered medicines that may have sub-therapeutic levels of active ingredient [Citation8]. Moreover, the cost of medicines also decreases with the increase in registered alternatives of the same molecule [Citation9,Citation10]. Therefore, the need for improvement and the strengthening of regulatory systems in LMICs cannot be overstated. The World Health Organization (WHO), supported by the World Health Assembly resolution 67.20, has been working to strengthen regulatory systems for medical products in these countries using the Global Benchmarking Tool (GBT) [Citation11]. The GBT evaluates the maturity level of a regulatory system, with a level 1 designation signifying that ‘some elements of a regulatory system exist’ and level 4, a ‘regulatory system operating at an advanced level of performance and continuous improvement’ [Citation12]. The outcome of the GBT assessment is the designation of WHO-listed authority status or development of an Institutional Development Plan, which summarizes gaps as well as the activities and resources required to strengthen the regulatory system [Citation13]. A number of African countries have already been assessed using the WHO GBT, and Ghana and Tanzania have attained maturity level 3, which represents a stable, well-functioning and integrated regulatory system’ [Citation3,Citation14,Citation15]. The MCAZ underwent a formal benchmarking assessment from 16 to 27 August 2021. The MCAZ is now in the process of developing corrective and preventive actions (CAPA) to address the findings identified in the Institutional Development Plan (IDP).

1.1. Regulatory landscape in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is a country in the Southern African region bordered by Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and Zambia [Citation16], with a population of just under 15 million in 2019 [Citation9]. The gross domestic product (GDP) for Zimbabwe in 2019 was USD 21 billion [Citation17]; however, the government has declared a goal for Zimbabwe to become a ‘prosperous and empowered upper middle-income economy by 2030’ coining the phrase ‘Vision 2030’ [Citation18]. Accordingly, various measures are being implemented to achieve this including the objective of responsive public institutions [Citation18]. The Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe (MCAZ) is an autonomous agency under the Ministry of Health and Child Care and successor to the Drugs Control Council established by an Act of Parliament, the Drugs and Allied Substances Act of 1969 [Citation19,Citation20]. The MCAZ is responsible for regulating medicinal products for human and veterinary use as well as medical devices [Citation20] and there are plans to expand its scope of control to wider medical devices and blood and blood products. The scope of activities carried out by the MCAZ are the issuing of marketing authorizations/product licenses, post-marketing surveillance, laboratory analysis of samples, clinical trial authorization, regulation of advertising, site inspections/visits, import and export control, and licensing of premises and persons responsible for the manufacture, supply, distribution, storage, and sale of medicines [Citation20]

Over the years, the MCAZ has been involved in various activities with the aim to improve capacity, for example, participation in the WHO prequalification of medicines and global benchmarking programmes as well as the Southern African Developing Community (SADC) regional work-sharing initiative, ZAZIBONA. As a result of this investment, the MCAZ has been recognized by the African Union Development Agency New Partnership for Africa Development (AUDA NEPAD) as a regional center of regulatory excellence [Citation20,Citation21] and was identified in the Zimbabwe National Development Strategy for 2021– 2025 as being pivotal in the improvement of the pharmaceutical value chain. The same strategy specified that registration timelines must be reduced to facilitate access to medicines by the Zimbabwean people [Citation22]. and colleagues recommended a comparison of the registration process of Zimbabwe with other countries in the Southern African Developing Community (SADC) region as well as higher income countries of comparable size with mature regulatory authorities, for the purpose of continuous improvement and benchmarking [Citation20]. The aim of this study therefore was to review the registration process of Zimbabwe in comparison with the regulatory authorities of Australia, Canada, Singapore, and Switzerland to identify areas of strength of the MCAZ as well as opportunities for improvement including implementing best practices with the goal to ultimately reduce registration timelines and improve patients’ access to life-saving medicines.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

The regulatory authorities included in this study were the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of Australia; Health Canada, Health Sciences Authority (HSA) of Singapore, and Swissmedic of Switzerland. These authorities were selected because of their size and the type of review models employed. In addition, it was imperative to include mature, WHO-recognized agencies that would contribute to the goals of this comparison, allowing the MCAZ to learn from best practices. The strength of the group of countries selected for this comparison is their similarity to the MCAZ in their participation in collaborative regulatory initiatives.

2.2. Data collection

Data for the comparator authorities was originally collected in 2014 and subsequently updated for 2020, including metrics data for all the comparator agencies except HSA, which was updated from public domain [Citation23], whilst data for Zimbabwe was collected in 2019 [Citation20]. A questionnaire that standardizes the review process, allowing key milestones, activities and practices of the five regulatory authorities to be identified [Citation24] was completed by a senior member of the division responsible for issuing marketing authorizations and validated by the head of the agency.

The 5-part questionnaire comprises the following:

Part 1: Organization of the agency; that is, the organization, structure, and resources of the agency.

Part 2: Types of review model; that is, the review models employed for scientific assessment, the level of data required, and the extent of assessment of the data as well as reliance on other authorities if applicable.

Part 3: Key milestones in the review process; that is, the process of assessment starting from receipt of the dossier, validation/screening, the number of cycles of scientific assessments including the questions to the sponsor/applicant, expert registration committee meetings to the final decision on approval or refusal of a product for registration. A standardized process map, developed based on the experience of studying established and emerging regulatory authorities, was embedded in the questionnaire. Data for new active substances (NASs), approved by the study participants in 2019 was extracted from the literature as well as the information provided by the agency.

Part 4: Good review practices (GRevP); that is, the activities adopted to improve the consistency, transparency, timeliness, and competency, building quality in the review process.

Part 5: Quality decision-making processes; that is, the practices implemented to ensure quality decision making during the process of registration.

2.3. Models of regulatory review

There are three models that can be used by national authorities for the regulatory review of products [Citation24] and these are:

Verification review (type 1): the agency relies on assessments and approval by two or more reference regulatory authorities and employs a verification process to ensure that the product under review conforms to the previously authorized product specifications. A reference regulatory authority is defined as a mature and established authority whose reviews or decisions are relied on by another regulatory authority.

Abridged review (type 2): the agency conducts an abridged review (reduced in scope and length, while retaining essential elements) of a medicine approved by at least one reference authority, taking into consideration local cultural and environmental factors.

Full review (type 3A): the agency performs a full review of quality, safety, and efficacy of the product, but requires prior approval by another authority and/or type 3B which involves independent assessment of the same but does not require prior approval of the product by an authority.

In recent years, regulatory authorities have successfully implemented a work-sharing model of review in the form of joint reviews or coordinated assessments. For Zimbabwe, this is achieved through participation in the ZAZIBONA initiative [Citation25] and for Australia, Canada, Singapore and Switzerland, through the ACCESS consortium [Citation26]. The other members of the ZAZIBONA initiative are Angola, Botswana, Comoros Islands, Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, United Republic of Tanzania and Zambia. In January 2021, the United Kingdom also became a member of the ACCESS consortium.

3. Results

For the purpose of clarity, the results will be presented in five parts: Part I – organization of the regulatory authorities; Part II – review models; Part III – key milestones in the review process; Part IV – good review practices; and Part V – quality decision-making practices.

3.1. Part I – organization of the regulatory authorities

The five authorities have similar scopes and mandates to regulate medicinal products and medical devices although for the MCAZ the scope for medical devices is currently limited to gloves and condoms. In addition, TGA, Health Canada and Swissmedic also regulate in vitro diagnostics while only TGA and Health Canada regulate blood and blood products. Cell and tissue products, food, complementary medicines and/or natural health products were outside the scope of this study. The MCAZ has 143 employees in total, translating to a staff to population ratio of 9 per million. This figure is very low when compared with the other four countries: TGA 31, Health Canada (Health Products and Food Branch) 60, HSA 102 and Swissmedic 45. In general, the fees charged for both proprietary and non -proprietary products are much lower for MCAZ compared with the fees charged by the four authorities in the high-income countries. The MCAZ receives no funding from the government. In comparison, the TGA review of medicines and medical devices is fully cost recovered with no government funding, while for Health Canada, HSA and Swissmedic government contribution to funding is 67%, 80% and 18%, respectively.

3.2. Part II – review models

The major difference in the review models between Zimbabwe and the other four countries is that the MCAZ requires a certificate of pharmaceutical product (CPP) – confirming that the medicine has been approved in the country of origin before it can be registered (). The MCAZ conducts a full review (type 3A) only for generics and biosimilars not approved by a reference authority but approved in the country of origin while the other agencies conduct a full review for all products. All of the studied agencies, with the exception of Health Canada, conduct abridged reviews while only the MCAZ and HSA conduct verification reviews. However, please note that a forward regulatory plan 2020– 2022 has been developed with an initiative title of ‘regulations amending the food and drug regulations – use of foreign decisions pathway,’ which will enable Health Canada to conduct abridged reviews of products approved by a trusted authority. (). The MCAZ currently uses verification review only for WHO- prequalified products while HSA conducts verification reviews for products approved by two reference authorities. All five agencies have a formal priority review procedure for medicines used in conditions for which no other treatment exists or for medicines improving existing therapies.

Table 1. Models of assessment employed by the five agencies

3.3. Part III – key milestones in the review process

The MCAZ has defined key milestones and target timelines in the regulatory review process. The simple map () [Citation20] illustrates the full review process for a product that is approved after one cycle with no questions raised after assessment. Steps taken in the event that a registration application is refused, are not depicted in the process map. The review process and milestones recorded are similar for TGA, HSA and Swissmedic; however, the targets for each milestone are different. For Health Canada, the milestones are similar; however, the clock is only stopped for a notice of deficiency but not for clarification requests, which are sent during review. In addition, the agency does not have a target or formal milestone for queuing in the review process. All five agencies have defined target times for the key milestones in their review processes ().

Table 2. Comparison of target times in the full review process for five agencies

Figure 1. Regulatory review process map for Zimbabwe showing target times in calendar days. The map represents the review and authorization of a product that goes to approval after one review cycle – the additional two cycles would add another 120 calendar days, resulting in 480 days as the target review time. Reprinted from Sithole et al, 2021 [Citation20].

![Figure 1. Regulatory review process map for Zimbabwe showing target times in calendar days. The map represents the review and authorization of a product that goes to approval after one review cycle – the additional two cycles would add another 120 calendar days, resulting in 480 days as the target review time. Reprinted from Sithole et al, 2021 [Citation20].](/cms/asset/044b11bc-9792-438a-84a9-c41e00e616ef/ierj_a_1987883_f0001_oc.jpg)

3.4. Pre-submission procedure

The MCAZ has no pre-submission procedure for applicants who are planning to submit applications for registration. However, the HSA requires a notice of intent to submit an application for type 3 review. The TGA, Health Canada and Swissmedic provide applicants an opportunity to meet with agency staff to discuss upcoming submissions. This allows the agency to plan resources, familiarize with the application and discuss any issues with the applicant prior to submission.

3.4.1. Validation

All five agencies perform this administrative step in the review process to screen applications for completeness within specified timelines (). The legal status of the applicant as well as format, fees and good manufacturing process (GMP) status are some of the issues checked at this stage. The MCAZ has the longest target time for validation at 90 days, followed by Health Canada at 55 days, then HSA and Swissmedic at 30 days while TGA has the shortest target time of 15– 21 days.

3.4.2. Queuing

The queue time is the time taken between acceptance of a submission for evaluation and the start of the scientific assessment. Queuing is indicative of a backlog and lengthens the overall approval time of products. The MCAZ has a target queue time of 90 days while the HSA queue time is 90 −180 calendar days. Health Canada does not have a queue time milestone but reviews do not necessarily start following acceptance. The TGA and Swissmedic reported that they do not have a backlog therefore there is no queuing of applications.

3.4.3. Scientific assessment and data requirements

All five agencies require the full modules 1 to 5 of the Common Technical Document format; that is, chemistry, manufacturing and control (CMC), non-clinical and clinical data as well as summaries, regardless of the review model used. An extensive assessment of all the sections is conducted under the full review model. The review of the quality, safety and efficacy data is done in parallel by four of the agencies, whereas MCAZ reviews these sections sequentially for all products excluding biosimilars [Citation20]. Pricing negotiations are separate from the technical review in all the five agencies; however, in Australia and Canada, there is an option for health technology assessments to be conducted in parallel with the regulatory review.

For Health Canada, 90% of NASs are issued with a decision after the first review cycle, whereas assessments are completed in one or two cycles for TGA and Swissmedic and three to four cycles for MCAZ. The TGA, Health Canada and Swissmedic set targets for both the primary scientific assessment and the second round of assessment and in addition share the assessment reports with the applicant. Similarly, the MCAZ also sets targets for both the primary and second round of assessments. The MCAZ however, does not share assessment reports with applicants. The TGA, Health Canada, Swissmedic and HSA make use of internal and external experts to perform reviews while the MCAZ uses internal experts for reviews and external experts only for the Committee procedure.

3.4.4. Questions to applicant

Applicants are given opportunity to respond to questions arising during assessment in all the five agencies. The MCAZ collects all the questions into a single batch and sends these to the applicant at the end of each review cycle (stop-clock) and only after presentation to the external expert Committee. The HSA and Swissmedic send the questions to the sponsor/ applicant at the end of a review cycle but before presentation to the Committee. Health Canada sends questions to applicants during review known as clarification requests. This is done independently by the safety, efficacy and quality review streams. However, the review is paused and a notice of deficiency (NOD) sent to the applicant if the observed deficiencies prevent continuation of the review. Applicants are allowed only one NOD per application. This is similar to TGA, whose assessors can contact the applicant directly to seek clarification during the review process. The TGA usually presents the report to the committee when it is at an advanced stage, although there is scope to obtain committee or subcommittee advice at an earlier stage, whereas there is no formal procedure for Committee involvement at Health Canada. The time given to the applicant by the five agencies ranges from 14– 90 days ().

3.4.5. Expert committee

All five agencies engage expert or advisory committees at different points in the regulatory review process. The MCAZ is the only agency mandated to follow the committee’s decision. The other four agencies use the committee in an advisory capacity to provide expert opinions and additionally the committee for Swissmedic may also conduct assessments or reviews.

3.4.6. Authorization

Labeling issues must be addressed before a product is authorized in all five agencies. At the MCAZ, responsibility for the marketing authorization decision lies with the Registration Committee. The Director General makes the decision on registration for Health Canada and HSA, whereas for TGA, the responsibility is delegated to a senior medical officer, and at Swissmedic the decision is made by the case team with the involvement of the Head of Division/Sector. In all five agencies, compliance with GMP is audited during the review process and the outcome informs product authorization. The target time for the overall approval for a full review for the MCAZ is 480 days, inclusive of the applicant’s time and this is comparable to the target times for the comparator countries: TGA, 330 days including the applicant time; Health Canada, 355 days excluding applicant time to respond to an NOD and any other approved pauses, ranging from 5 to 90 days; HSA, 378 calendar days excluding the queue and applicant time; and Swissmedic, 330 days excluding the applicant time (). The target times are comparable because the 480 days for MCAZ includes the applicant’s time. If the applicant’s time (target 60 days per assessment cycle for 2 cycles) was to be excluded, this would come down to 360 days.

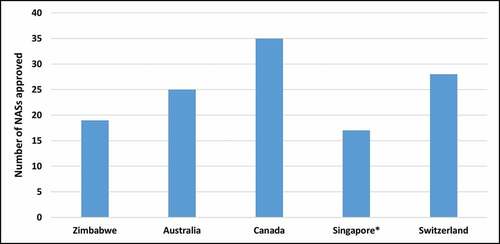

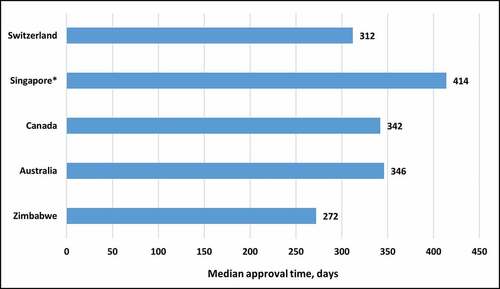

3.4.7. Metrics of approved products and review times

The number of NASs approved in 2019 was evaluated (). Health Canada had the highest number of NASs approved at 35, followed by Swissmedic at 28 and TGA at 25. MCAZ had the lowest number at 19. The median approval time (from submission to completion of scientific assessment) for NASs in 2019 for the five agencies was evaluated () and MCAZ had the shortest approval time of 272 calendar days followed by Swissmedic at 312 days, Health Canada at 342 and TGA at 346 [Citation12,Citation15]. It should be noted however, that MCAZ conducts an abridged review of NASs, as these would have already been approved by a reference agency. The times presented for Australia, Canada and Switzerland are for a full review, while HSA conducts abridged review.

3.5. Part IV – good review practices

Good review practices (GrevPs) can be defined as measures or practices implemented with the goal to ensure quality, transparency and consistency as well as continuous improvement in the regulatory review process. These were evaluated for the five agencies and compared for quality measures, transparency and communication, continuous improvement initiatives and training and education.

3.5.1. Quality measures

The study evaluated a number of quality measures (). The MCAZ and Swissmedic have a dedicated quality department and implement all eight of the quality measures. In addition, Health Canada has an established a quality management system and a dedicated office for the Biologic and Radiopharmaceutical Drugs Directorate and is in the process of establishing one for the Therapeutic Products Directorate, incorporating all quality measures. The TGA implement seven of the eight measures and the HSA implement six quality measures. Health Canada and Swissmedic have formally implemented GRevPs, while the other three authorities have informally implemented GRevPs. All five agencies participate in shared and joint reviews. The MCAZ is a member of the medicines’ registration harmonization initiative, ZaZiBoNa [Citation16], and the four comparator agencies are members of the ACCESS Consortium, and both initiatives have worked extremely successfully.

Table 3. Comparison of the quality measures implemented by the five agencies

3.5.2. Transparency and communication with industry stakeholders

A well-established and mature regulatory authority is expected to practice transparency and communication with stakeholders. This is also one of the indicators evaluated by the WHO Global Benchmarking Tool, which seeks to determine the maturity level of a regulatory system [Citation3]. This comparative study evaluated the performance of the five regulatory authorities using nine transparency and communication parameters (). All five agencies provide pre-submission scientific advice to industry although for the MCAZ, this is only given to local manufacturer's upon request. Of the five agencies, MCAZ implements the lowest number of parameters. Currently, post-approval feedback on submitted applications, contact details of technical staff, the summary basis of approval and advisory committee dates are not shared with the stakeholders. Health Canada and the HSA also do not share the advisory committee dates with applicants and in addition, HSA does not publish the summary basis of approval or provide feedback to the applicant on submitted dossiers. The TGA implements all of the nine transparency and communication parameters as does Swissmedic, while Health Canada implements eight, the HSA six and the MCAZ five of the nine measures ().

Table 4. Comparison of the transparency and communication parameters with regulated parties in the five agencies

3.5.3. Continuous improvement initiatives

A comparison was made of the continuous improvement initiatives that have been implemented by the five regulatory authorities. The MCAZ and Swissmedic implement all five initiatives, the TGA, HSA and Health Canada implement four of the five initiatives ().

Table 5. Comparison of continuous improvement initiatives in the five agencies

3.5.4. Training and education

All five regulatory authorities implement all eight of the measures for training and education namely induction training, on-the-job training, attendance at internal and external courses, international workshops and secondments to other regulatory authorities, sponsoring of post-graduate degrees, in-house courses as well as external speakers being invited to the authority.

3.6. Part V – quality decision-making practices

The 10 Quality Decision Making Practices (QDMPs) were articulated as part of the development of the Quality of Decision-Making Scheme (QoDoS) instrument, which has been implemented in a number of medicines development scenarios [Citation27,Citation28]. Generally, all five authorities either partially or fully implement the majority of the ten QDMPs that were evaluated in the study (Supplementary ). However, the MCAZ does not have a documented framework in place on QDMPs.

4. Discussion

The results from this study show that the human and financial resources available to national regulatory authorities (NRAs) in LMICs are much lower compared with those in higher income countries. However, the funding models of the regulators in the higher income countries do differ significantly – ranging from majority government funding through to full industry funding of regulatory activities. A challenge that exists for a country such as Zimbabwe, whose NRA relies 100% on fees, is the high cost of entry to the market for applicants due to the registration fees being high relative to the country’s GDP and the population’s ability to pay for the medicines [Citation22,Citation29]. This means that it may not be possible for the MCAZ to increase registration fees in order to improve available resources for regulatory reviews, therefore the use of reliance may be a more appropriate strategy. The need for reliance and the efficient use of limited resources by LMICs has been documented in the literature [Citation25,Citation30–32], with the argument that it allows NRAs to focus their limited resources on products not approved elsewhere [Citation20]. Reliance also provides the NRAs the opportunity to build capacity without hindering access to medicines by their populations. Participation in harmonization initiatives such as ZaZiBoNa [Citation25] by countries with low GDPs and small populations may also provide manufacturers the potential incentive of a larger market. It has been pointed out that it is no longer adequate for the regulator to just passively wait to assess submissions received from industry. The regulator must now be proactive in providing pathways that facilitate and encourage the timely registration of medicines to promote public health [Citation6,Citation32] and information on these pathways should be documented and publicly available.

The requirement for a CPP is not necessary where a full review is conducted [Citation33]. The findings of this study show that of the studied regulatory authorities, only the MCAZ requires the CPP as a pre-requisite for registration and does not accept products that are not approved in the country of origin. This is consistent with findings from studies in the literature that showed that regulatory authorities in the emerging economies still require CPPs [Citation33]. Manufacturers have indicated that the time taken to obtain a CPP can delay the submission of applications for registration and subsequent supply of life-saving medicines to countries enforcing that requirement. Therefore, the requirement for a CPP should be removed where a full review is conducted [Citation31] and an alternative such as the marketing authorization license used if evidence of approval is required. Furthermore, there is a need for regulatory authorities in LMICs to build adequate capacity to independently assess NASs (new chemical entities and biologicals) even though at present, most companies only file applications for registration in developing economies several years after approval and use in well-resourced markets [Citation8,Citation31]. In the near future, we could see products developed for diseases endemic to Africa submitted directly to the African countries and therefore the capacity to conduct independent reviews needs to be developed [Citation25,Citation34].

The key milestones recorded in the review process, data requirements and the extent of scientific assessment were similar for the five agencies with the only difference being the practice by TGA and Health Canada of requesting clarifications formally during the scientific assessment in addition to the formal questions sent to the applicant at the end of a review cycle. This is a practice that could potentially reduce the number of review cycles and questions eventually sent out during the clock stop. Generally, the MCAZ target times were longer for validation and queue time but comparable for questions to the applicant and overall approval time. The MCAZ ability to have a comparable review process and timelines with less resources than the other authorities is a positive attribute. There is an opportunity for the MCAZ to learn from the authorities in the study to adopt practices that could potentially further reduce approval times. Another step in the review process implemented by TGA, Heath Canada and HSA that could benefit MCAZ is to provide applicants, especially the local manufacturing industry, more opportunity for pre-submission meetings. The MCAZ was found to be the only NRA in the study relying on an expert committee to make the decision on the marketing authorization of products, whereas for the other authorities, this decision was made by the Head of the Agency, Head of Section or agency staff, with the expert committee used in an advisory capacity. The MCAZ could consider adopting a similar position, as preparation for the frequent committee meetings adds to the registration time. However, this would require a legislative amendment, as all statutory decisions are made by the Authority (Board).

Another strength of the MCAZ is the implementation of GRevPs such as ensuring quality in the review process, use of standard operating procedures, guidelines and templates, continuous improvement initiatives such as quality audits and internal tracking systems, and training and education of assessors. However, there is room for improvement on transparency and communication with stakeholders. There is also a scope to improve decision-making practices by the MCAZ through the development of a formal framework. Although the issues of pricing and availability of medicines are outside the scope of this paper, Zimbabwe could learn from the high-income countries such as those that took part in this study, and establish a health technology assessment (HTA) agency to better tackle the issues of accessibility and affordability of health services including medicines. This will facilitate the prioritization of health interventions and the formulation of evidence based health policies leading to better outcomes for patients. The WHO has also recommended that member states build capacity in health intervention and technology assessment to support universal health coverage [Citation35]. The absence of formal HTA agencies, lack of capacity and shortage of resources are some of the reasons cited as contributing to the lack of health technology assessments in LMIC [Citation36,Citation37]

Several studies have been conducted for South Africa, Turkey, Jordan and Saudi Arabia in comparison with other mature agencies [Citation38–41]. Like Zimbabwe, these countries had strengths in their review processes that were comparable to those of the mature agencies. The challenges identified and the recommendations made although different, provided the opportunity for these countries to strengthen their regulatory review processes.

4.1. Limitations and future work

Certain data for the HSA was obtained from the public domain and the metrics data were obtained from an industry survey. Although we feel that the quality decision practices are adhered to by MCAZ intuitively, there has not been a structured systematic approach to measure these quality decision-making practices and this could be the basis for a future study.

4.2. Recommendations for adopting best practices

This comparative study identified MCAZ strengths and highlighted opportunities for improvement, which if implemented, will enable achievement of the MCAZ vision to be a leading regulatory authority in Africa. MCAZ may wish to consider the following recommendations:

Expediting the process of expanding its scope of control to regulate all medical devices, in vitro diagnostics, and blood and blood products

Removing the requirement for a Certificate of Pharmaceutical Product, since the authority currently conducts a full review (type 3 A) and allow applicants the option of providing a marketing authorization license instead

Building capacity to enable the independent assessment of products, particularly innovative medicines, not approved elsewhere.

Publishing clear information on the review models used for assessments on its website, including the procedure criteria, recognized reference authorities and timelines

Using online submission tools or increasing the number of administrative officers to reduce validation time. TGA observed that online submissions resulted in significant improvements in efficiency for South-East Asian authorities (J. Skerritt, personal communication, 11 March 2021)

Setting targets for the primary and second round of assessments and measuring performance against these targets in order to effectively monitor where time is spent in the review process

Taking applications and assessment reports to the Committee only after assessors have reviewed the applicant responses to formal questions and seeking clarifications from the applicant during the review process

Defining and communicating the target for the overall approval time excluding the sponsor/applicant time to effectively monitor the agency approval time

Applying strategies to shorten the queue time including implementing parallel instead of sequential reviews as well as increasing the number of competent assessors

Improving transparency and communication with stakeholders to fulfil a goal of the Zimbabwe Vision 2030 to have responsive institutions.

Developing and formally implementing a documented framework for quality decision-making practices

5. Conclusions

This study compared the registration process of the MCAZ, a regulatory authority in a low-income country with mature regulatory authorities in higher income countries. The findings showed that MCAZ is able to achieve timelines comparable to the mature agencies through efficient use of resources such as implementation of reliance and international best practices such as setting and monitoring of targets for key milestones in the review process. Other regulatory authorities in LMICs can draw lessons from this example.

More importantly, opportunities for system/process improvement were identified from the study that can support the MCAZ in achieving its vision to be a leading regulatory authority on the African continent and to contribute to effective healthcare delivery in Zimbabwe through improved quality of reviews and reduced registration timelines.

Author contributions

TS acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript; SS designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript; GM analyzed and interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript; SW designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Health, Science, Engineering and Technology ECDA, University of Hertfordshire [Reference Protocol number: LMS/PGR/UH/04350].

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (791.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Therapeutic Goods Administration, Health Canada, Health Sciences Authority, Swissmedic and the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe. The authors also wish to thank Mrs Patricia Connelly for the editorial assistance.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sustainable development goals. [Internet] New York (NY): United Nations; [ cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health

- Guzman J, O’Connell E, Kikule K, et al. The WHO global benchmarking tool: a game changer for strengthening national regulatory capacity. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(8):e003181.

- Khadem Broojerdi A, Baran Sillo H, Ostad Ali Dehaghi R, et al. The world health organization global benchmarking tool: an instrument to strengthen medical products regulation and promote universal health coverage. Front Med. 2020;7:457.

- Evans DB, Hsu J, Boerma T, et al. Universal health coverage and universal access. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(8):546–546A.

- Universal health coverage. [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; [ cited 2021 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1

- Lumpkin M, Eichler HG, Breckenridge A, et al. Advancing the science of medicines regulation: the role of the 21st‐century medicines regulator. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:486–493.

- Ndomondo-Sigonda M, Miot J, Naidoo S, et al. Medicines regulation in Africa: current state and opportunities. Pharm Med. 2017;31:383–397.

- Rägo L, Santoso B. Drug regulation: history, present and future. Drug benefits and risks: Int Textbook Clin Pharmacol. 2008;2:65–77.

- Dunne S, Shannon B, Dunne C, et al. A review of the differences and similarities between generic drugs and their originator counterparts, including economic benefits associated with usage of generic medicines, using Ireland as a case study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14(1):1.

- Kaplan WA, Ritz LS, Vitello M, et al. Policies to promote use of generic medicines in low-and middle-income countries: a review of published literature, 2000–2010. Health Pol. 2012;106:211–224.

- Essential medicines and health products. WHO global benchmarking tool (GBT) for evaluation of national regulatory systems. [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; [ cited 2021 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/benchmarking_tool/en/

- Regulatory system strengthening for medical products. 2014 24 May. Contract No: World Health Assembly 67.20. [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; [ cited 2021 Jul 30]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67-REC1/A67_2014_REC1-en.pdf

- World Health Organization. World health organization concept note: a framework for evaluating and publicly designating regulatory authorities as WHO-listed authorities. WHO Drug Info. 2019;33:139–158.

- Tanzania food and drug authority becomes the first to reach level 3 of the WHO benchmarking programme. [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; [ cited 2021 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/tanzania-food-and-drug-authority-becomes-first-reach-level-3-who-benchmarking-programme

- Ghana foods and drugs authority (FDA) attains maturity level 3 regulatory status. [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; [ cited 2021 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/ghana-foods-and-drugs-authority-fda-attains-maturity-level-3-regulatory-status

- International Monetary Fund African Department. Zimbabwe: INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND; 2017.

- Zimbabwe country data. [Internet]. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2021 [ cited 2021 Jan 6]. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/country/ZW

- Transitional stabilisation programme reforms agenda. Hararae, Zimbabwe: Republic of Zimbabwe; 2018 Oct 5. [ cited 2020 Dec 20]. Available from: https://t3n9sm.c2.acecdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Abridged_Transitional_-programme.pdf

- Medicines control authority of Zimbabwe. [Internet] Harare, Zimbabwe: Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe; [ cited 2020 Apr 3]. Available at: http://www.mcaz.co.zw/index.php/downloads/category/7-regulations

- Sithole T, Mahlangu G, Salek S, et al. Evaluation of the regulatory review process in Zimbabwe: challenges and opportunities. Ther Innov Reg Sci. 2021;55:474–489.

- Ndomondo-Sigonda M, Miot J, Naidoo S, et al. The African medicines regulatory harmonization initiative: progress to date. Med Res Arch. 2018;6.

- Towards a prosperous and empowered upper middle income by 2030: national development strategy, January 2021 December 2025. [Internet]. Harare, Zimbabwe: Republic of Zimbabwe; [ cited 2021 Jan 13]. Available from: http://www.zimtreasury.gov.zw/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&id=64&Itemid=789

- Centre for Innovation in Regulatory Science. R&D briefing 77: new drug approvals in six major authorities 2010–2019. Focus on Facilitated Regulatory Pathways and Internationalisation; 2020 [ cited 2021 Jan 9]. Available from: https://cirsci.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CIRS-RD-Briefing-77-6-agencies.pdf

- McAuslane N, Cone M, Collins J, et al. Emerging markets and emerging agencies: a comparative study of how key regulatory agencies in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa are developing regulatory processes and review models for new medicinal products. Drug Info J. 2009;43:349–359.

- Sithole T, Mahlangu G, Salek S, et al. Evaluating the success of ZaZiBoNa, the Southern African development community collaborative medicines registration initiative. Ther Innov Reg Sci. 2020;54:1319–1329.

- McAuslane N, Leong J, Liberti L, et al. The benefit-risk assessment of medicines: experience of a consortium of medium-sized regulatory authorities. Ther Innov Reg Sci. 2017;51:635–644.

- Bujar M, McAuslane N, Walker SR, et al. Evaluating quality of decision-making processes in medicines’ development, regulatory review, and health technology assessment: a systematic review of the literature. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:189.

- Bujar M, McAuslane N, Walker S, et al. The reliability and relevance of a quality of decision-making instrument, quality of decision-making orientation scheme (QoDoS), for use during the lifecycle of medicines. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:17.

- Morgan SG, Yau B, Lumpkin MM, et al. The cost of entry: an analysis of pharmaceutical registration fees in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0182742.

- Luigetti R, Bachmann P, Cooke E, et al. Collaboration, not competition: developing new reliance models. WHO Drug Info. 2016;30:558.

- Ahonkhai V, Martins SF, Portet A, et al. Speeding access to vaccines and medicines in low- and middle-income countries: a case for change and a framework for optimized product market authorization. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0166515.

- Centre for Innovation and Regulatory Science. Workshop Report on Practical implementation of reliance models: What are the barriers and facilitators to the successful application of these models for innovative medicines, generics and variations? March 2018, South Africa. [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from https://cirsci.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2020/09/CIRS-March-2018-Workshop-report_Practical-implementation-of-reliance-models.pdf

- Rodier C, Bujar M, McAuslane N, et al. Use of the certificate for pharmaceutical products (CPP) in 18 maturing pharmaceutical markets: comparing agency guidelines with company practice. Ther Innov Reg Sci. 2020;55(1):1–11.

- Gwaza L Adjusted indirect treatment comparisons of bioequivalence studies [dissertation]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Utrecht University; 2016.

- SEA/RC66/R4-health intervention and technology assessment in support of universal health coverage. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2013 [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; [ cited 2021 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/medical_devices/assessment/resolutionsearo_searc66r4.pdf

- Attieh R, Gagnon M-P. Implementation of local/hospital-based health technology assessment initiatives in low-and middle-income countries. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:445–451.

- Nemzoff C, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K, et al. Adaptive health technology assessment to facilitate priority setting in low-and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6:e004549.

- Keyter A, Salek S, Banoo S, et al. The South African medicines control council: comparison of its registration process with Australia, Canada, Singapore, and Switzerland. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:228.

- Ceyhan EM, Gürsöz H, Alkan A, et al. The Turkish medicines and medical devices agency: comparison of its registration process with Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:9.

- Al Haqaish WS, Obeidat H, Patel P, et al. The Jordan food and drug administration: comparison of its registration process with Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia and Singapore. Pharm Med. 2017;31:21–30.

- Hashan H, Aljuffali I, Patel P, et al. The Saudi Arabia food and drug authority: an evaluation of the registration process and good review practices in Saudi Arabia in comparison with Australia, Canada and Singapore. Pharm Med. 2016;30:37–47.