ABSTRACT

Introduction

The regulatory approval of medical products in countries with limited regulatory resources can be lengthy, which often compromises patients’ timely access to much-needed medicines. To improve the efficiency of regulatory systems, reliance is being used. Reliance allows an authority to leverage the work performed by other authorities, such as scientific evaluations, to decide on medical products approval within their jurisdiction. This reduces duplication of regulatory efforts, resources and time, while maintaining national sovereignty.

Areas covered

This article analyzes the outcomes and stakeholders’ experience of using medicines assessments performed by Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRA) in the Collaborative Registration Procedures (CRP). Since its establishment in 2015, 59 approvals were granted to 16 medicines in 23 countries through SRA CRP. Results show that the procedure is delivering on the intended benefits of access and speed, with long-term positive impact for resource-limited countries. The article concludes with recommendations on the need for guidance on management of post-approval changes, wider promotion of the procedure, and increased collaboration between authorities.

Expert opinion

The SRA CRP provides a mechanism for the use of reliance by strengthening communication and promoting the exchange of information among regulators. This fosters faster regulatory approvals and, consequently, earlier access to medicines.

1. Introduction

The registration of medical products in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) or resource-limited countries can be lengthy, in particular, due to a combination of scarcity of human and financial resources, technical capacity, and lack of maturity of the regulatory systems for medical products [Citation1]. As a result, quality-assured, safe and effective medicinal products do not reach the target population in a timely manner, contributing to poor health outcomes and lower life-expectancy [Citation2]. The development of collaborative regulatory strategies for the approval of medical products has been pursued by the World Health Organization (WHO) and international authorities for many years. Several regulatory strategies co-exist sharing the aim of increasing regulatory efficiency globally. This is particularly relevant to countries with limited resources [Citation2,Citation3].

Authorities apply the principle of reliance to improve the efficiency of their regulatory systems. According to WHO Good Reliance Practices in the Regulation of Medical Products, reliance allows an authority to leverage the regulatory work performed by other competent and trusted regulatory authority or institution, with independent final decision-making by the relying agency [Citation4]. The concepts of reliance and regulatory cooperation are also supported by the recently published WHO Good Regulatory Practices in the Regulation of Medical Products [Citation5]. When properly anchored in the regulatory framework and implemented by the authority, the use of reliance can eliminate or reduce unnecessary duplication of regulatory efforts, save resources and time by focusing resources on other critical areas, whereas its national sovereignty is preserved.

The concept of reliance can be applied to all types of medical products and regulatory activities. For marketing authorization of medical products, the use of reliance allows a regulatory authority to use the scientific evaluation performed by another authority or institution and, on this basis, to approve or not the medical product within its jurisdiction.

In line with this and to respond to public health needs, WHO has developed collaborative procedures to accelerate the assessment and approval of medical products by resource-limited authorities, by providing them with access to scientific assessments. These include the WHO CRP of i) WHO-prequalified Finished Pharmaceutical Products, ii) Finished Pharmaceutical Products assessed and approved by SRAs, and iii) WHO-prequalified In-Vitro Diagnostics. The CRP procedures incorporate strong elements of capacity building and regulatory harmonization while aiming to ensure that much needed medical products reach patients more quickly.

This article focuses on the CRP of medicines assessed and/or approved by SRAs. As defined on WHO guidelines, SRAs comprise members and observers of the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), and regulatory authorities associated with an ICH member through a legally-binding mutual recognition agreement [Citation6]. They are also part of the WHO-Listed Authorities (WLA) interim list [Citation7].

The SRA CRP pilot was initiated in 2015. It uses the regulatory expertise of SRAs to facilitate and accelerate the national regulatory assessments and approvals of medicines (including small molecules, biologicals, generics, biosimilars, and vaccines) [Citation2,Citation8]. The procedure is applicable to any of these medicines when previously assessed and/or approved by an SRA and when they represent public health needs, including medicines that are not in the scope of WHO prequalification. The only condition is that the medicine has a positive scientific opinion (including EU-M4all opinions), or an approval granted by an SRA. The pharmaceutical company (sponsor or applicant) may submit the same dossier, using the ICH common technical document (CTD) format, to several National Regulatory Authorities (NRAs). Participation in CRP is voluntary and details on information sharing, management of confidentiality, timeframes and other requirements are described in the guideline of the procedure [Citation8] as well as on WHO website [Citation9].

Through the SRA CRP, the NRAs have access to the SRA full assessment, as well as manufacturing sites inspection reports including confidential information necessary for the evaluation. The NRAs can decide on full or partial reliance on the evaluation performed by SRAs, and they remain independent, responsible and accountable for the approval decisions in their countries [Citation4,Citation10,Citation11].

The participating SRAs included, initially, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) only, but any SRA as listed by WHO can participate [Citation6]. SRAs are considered to apply stringent, internationally recognized standards (including those from WHO) for the review of medicines’ quality, safety and efficacy [Citation10]. The SRA CRP is highly dependent on the ability and willingness of applicants, regulatory authorities, SRAs and WHO to work together to meet public health goals. Using the example of EMA as SRA, this collaboration is part of the Agency’s mission to improve public global health and to build capacity [Citation12].

This article presents the first analysis of the outcomes and impact of the SRA CRP, as well as stakeholder perceptions on the procedure strengths and challenges. The article concludes with recommendations to improve the procedure.

2. Methods

This article analyzes the regulatory submissions and approvals of the SRA CRP since the establishment of the procedure in 2015 to mid-2021, broken down by medicine, country of approval, therapeutic class, SRA and applicant, based on data collected by WHO and EMA.

Some data were collected by WHO, as part of its internal project to evaluate the SRA CRP pilot (2015–2018). The aim was to assess how and whether the SRA CRP activities were implemented as planned, with intended outputs, describing the strengths, challenges and areas of improvement of the procedure. The data collection included: i) documents/desk review; ii) interviews (individual and group; structured and semi-structured) of participating NRAs, applicants, SRAs, and WHO as facilitator; and iii) surveys (web-based questionnaire) of NRA focal points, managers and other stakeholders involved in the SRA CRP pilot.

The percentage of stakeholders’ representation out of the total of the interviewed participants is the following: 60% were NRAs, 20% were from WHO, 13% were applicants, and 7% were SRAs.

The percentage of stakeholders’ representation among those surveyed is as follows: 62% were NRAs, 25% were applicants, and 13% were SRAs.

3. Results

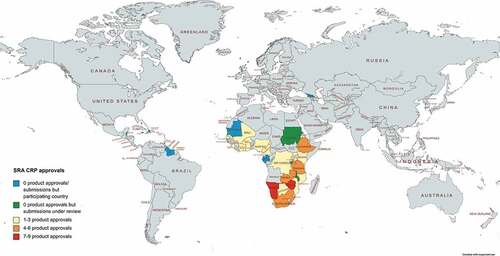

Between 2015 and mid-2021, there has been one regional regulatory organization, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM representing 15 countries) and 26 NRAs participating in the SRA CRP. The NRAs were Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cote D’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, the Republic of South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe [Citation9]. Altogether they represent a population of about 826 million citizens. Sixteen medicines have been submitted through the procedure to 23 different NRAs. lists the applicants, participating SRAs and the number of submissions and approvals per product including respective therapeutic area.

Table 1. List of SRA CRP submissions and approvals (as of June 2021)

In total, 88 product applications have been submitted through the SRA CRP and 59 regulatory approvals have been granted (). Namibia (nine medicines), Zimbabwe (seven), Tanzania (five), and Ethiopia, South Africa, and Zambia (four) approved the highest numbers of medicines.

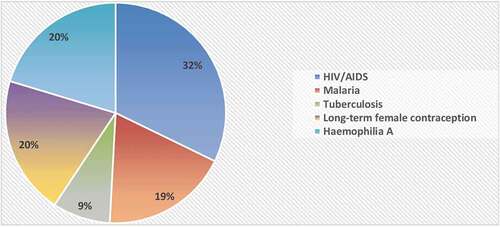

With respect to the therapeutic areas, most medicines were for the treatment of HIV/AIDS or malaria, long-term female contraception, and hemophilia (). The pharmaceutical forms included mostly oral tablets or suspensions, one suspension for parenteral administration, four solutions for injection, and one vaginal ring.

EMA was the SRA for 72 submissions for 14 medicines; this resulted in 47 approvals in 15 countries. The SRA CRP submissions for pyronaridine/artesunate and dapivirine used the scientific opinions issued by the EMA under the EU-M4all procedure. In addition, the EMA is involved in the SRA CRP submission of an additional medicine.

MHRA was the SRA for 18 submissions for 2 medicines, resulting in 12 approvals in 12 countries.

3.1. The SRA CRP Pilot evaluation

The evaluation of the four-year SRA CRP pilot shows that all stakeholders (NRAs, applicants and SRAs) concluded that most intended objectives, expected outcomes and benefits of the procedure were met and delivered. They all commonly agreed that the CRP was a successful and necessary initiative with long-term positive impact on public health. All participating stakeholders expressed willingness to continue participating beyond the pilot phase.

3.1.1. NRAs

All NRAs reported that they were able to significantly reduce the evaluation and approval time for new medicines when using SRA CRP. According to the reports provided by NRAs, the regulatory time reduced about 40% (on average) when compared to their fastest national procedures. Those who were not yet using harmonized dossiers based on international standards, started using the ICH CTD in national procedures outside the CRP, motivated by their positive experience with the SRA CRP. The NRAs reported to have observed major reductions and savings in time spent on CRP applications for new medicines, and in human (staff and capacity) and financial resources due to reduced workload. They were able to use the procedure and its requirements with ease due to a low level of complexity, and useful templates and guidance. NRAs also stated that one of the main strengths of the procedure was the possibility to use reliance based on high-quality reports from trusted SRAs, leading them to well informed and quality decision-making. All these elements led ultimately to faster approval and availability of quality-assured medicines in the country. They described their participation as not only avoiding duplication of efforts but also building capacity at the NRA through the learnings from the SRA assessment reports. Regular and adequate communication between NRAs, WHO and SRAs during the procedure and the training conducted by WHO were also considered helpful and strengthening for the NRAs.

In contrast, the low number of applications going through the CRP was perceived as an area for improvement. In some jurisdictions, the resource shortages, language, and country logistic issues (including poor power supply or internet connection) affected communications or access to relevant databases and documents. Challenges related to the coordination and communication throughout the procedure were also highlighted, namely the lack of clarity in the procedure on some steps (who should notify whom), the lack of user-friendly tools to exchange information and report progress of applications, the applicants’ low level of awareness about the CRP and the lack of more direct interactions between SRA and NRAs. The submissions of incomplete dossiers or discrepancies between the information submitted by the applicant and the one assessed by SRAs, were considered as the main causes for delays during the procedure. NRAs also identified the need for further guidance, particularly on post-approval management of medicines approved through SRA CRP.

3.1.2. Applicant/manufacturer

Applicants reported to have benefited from the ease and good flow of the procedure, with fewer requests for country-specific requirements, more alignment of the dossier with international standards, and a consolidated list of questions made by NRAs, when compared to non-CRP national procedures in the same countries. Applicants observed a reduction in the number of inspections of manufacturing sites and in the number of samples retested prior to approval due to the use of reliance by many NRAs. Costs were decreased since the same dossier, aligned with international standards, could be submitted to different countries and different regions. The possibilities to hold informal exchange with WHO and smooth coordination with SRAs were also highlighted by applicants as some of the procedure strengths. Applicants also emphasized that, in addition to the relevance for industry from an ethical and civic responsibility point of view, the overall shorter registration timelines observed in many countries were among the main reasons for their continued participation.

Nevertheless, applicants identified as main challenges the low number of participating NRAs, the variable extent and consistency in applying reliance and the lack of commitment in meeting established procedural timelines. In some cases, NRAs still required duplicated inspections, retesting, or technical information to register the medicines in their countries. Poor or inconsistent communication with some NRAs and issues with approachability posed significant challenges to applicants. The need for clear and timely communication mechanisms to exchange information among stakeholders and further guidance on management of post-approval changes for harmonized and coordinated actions were highlighted by applicants.

3.1.3. SRAs

SRAs reported no difficulty in following or implementing the procedure and its requirements, especially in the early stages, which was perceived as a strength. SRAs were often approached by NRAs and provided the requested clarifications or validated information. The SRA reasons for participation in the procedure stemmed from their objective to promote their expertise, and from their mission to foster reliance and collaboration among NRAs, to contribute to making quality-assured medicines available to patients or populations worldwide within short timelines, ultimately improving global public health.

SRAs identified as challenges in some instances the need for human resources and time allocated to SRA CRP, namely the validation of the Quality Information Summary (QIS), a document containing the final agreed-upon key quality information of the product dossier. The lack of transparency and organized communication mechanisms to notify and exchange information between stakeholders on progress and outcomes of the CRP procedure was also a main challenge. SRAs proposed to be involved and collaborate to respond to the lack of stakeholders’ knowledge and familiarity with SRA CRP. Furthermore, tightening the collaboration between NRAs-NRAs, and NRAs-SRA would support greater openness and use of reliance by NRAs, and build greater trust. A similar need for guidance on post-approval management of medicines registered through SRA CRP was also pointed out.

4. Discussion

Regulatory approval of high quality, safe and effective medicines in any country is a necessary but resource-demanding regulatory process, which continues beyond the marketing authorization of the medicine. The lifecycle management of medicines is a great challenge for resource-limited countries, particularly the management of post-approval changes.

The evaluation of the SRA CRP and its pilot, based on data and stakeholders’ perceptions, confirms that the procedure delivers on expected objectives and benefits, including shortened timelines (from submission to approval), reduced duplication of efforts and resources (human and financial). It also shows significant and long-term positive impact for the LMICs involved. Additional benefits include greater application of international harmonized standards, not only for NRAs but also for applicants, an added capacity building component and an informed and high-quality decision-making at the NRA. A key success of the procedure is related to 59 approvals for 16 medicines in 23 countries.

The key areas for improvement and recommendations include greater collaboration, communication and transparency between NRAs, applicants, SRAs and WHO, to facilitate interactions and regular sharing of information between stakeholders. To this end, a centralized, live platform could be developed to share the status, progress and challenges of applications in real time including information related to post-approval changes. The use of MedNet, a WHO collaborative platform for scientific information exchange and sharing, could be tailored for that purpose. The organization and presentation of product information in Mednet could be improved to facilitate navigation throughout documents, saving NRAs time. The use of reliance and recognition approaches by NRAs should be further encouraged, especially to avoid inefficient duplication of inspections of manufacturing sites and retesting of samples prior to registration. A stronger commitment from NRAs in complying with SRA CRP requirements, including established timelines, should be fostered. This may be achieved through a more active role of WHO in promoting accountability of NRAs. Of note, the NRAs requested that the clock should only start counting the assessment and registration time once the SRA assessment report is received, rather than when the submission is completed by the applicant. While WHO templates and guidance were found very useful, the post-approval changes and management procedures should be further defined and developed, with guidance for stakeholders on how to coordinate and manage them. The introduction of line extensions in the CRP procedure was proposed. There is the urgent need to increase stakeholders’ awareness of SRA CRP. This will include public communication on its outcomes to encourage more countries, more applicants and more SRAs to participate in the procedure and to become familiar with the process and procedural steps. This article is intended to contribute to this goal.

5. Conclusions

The SRA CRP enables faster access to quality-assured, safe and effective medicines for patients in need. The procedure reduces the time from submission to approval, avoids duplication of efforts, and decreases workload and human and financial resources in resource-limited countries, leading to greater efficiency in the regulatory processes. Overall, the stakeholders confirmed that, from their perspective, the intended objectives, expected outcomes and benefits of SRA CRP were delivered. They saw the continuation of the use of the procedure as relevant and necessary to public health and intend to continue participating in CRP activities.

Recommendations to the procedure include the need for more direct interactions between NRAs–NRAs and NRAs-SRAs, additional guidance on post-approval management, and increased awareness of the SRA CRP by all stakeholders. Increased use will require active promotion of the procedure but will help build NRAs’ regulatory capacity, supplemented by the SRAs’ expertise, especially for innovative medicines. The EMA, as participating SRA, is committed to continue collaborating and supporting the SRA CRP to increase patients access to medicines all over the world.

6. Expert opinion

‘WHO Collaborative Registration Procedure using Stringent Regulatory Authorities’ medicine evaluation: reliance in action?’ is the first published article that aims to assess the impact of the SRA CRP on global public health. The procedure was established in 2015 and intends to leverage the scientific assessment performed by SRAs to accelerate the regulatory approval of medicines through the principle of reliance. The use of reliance allows greater efficiency by reducing review timelines and preventing excessive duplication. This helps to improve patients’ access to quality-assured, safe and effective medicines as it is shown in this article.

Procedures as the SRA CRP promote the communication among regulators and NRAs’ understanding of internationally recognized regulatory standards. The exchange of information and the sharing of data are the bases for reliance-based regulatory procedures. These procedures bring a component of capacity building for resource-limited regulatory authorities, foster the level of convergence and harmonization of requirements and increase the level of trust between regulators. The participation in the SRA CRP can bring regulators to work more closely together, promoting the use of other reliance-based regulatory pathways, as the establishment of joint assessments or work-sharing among regulators.

The use of SRA CRP can be extended to more therapeutic areas and to more participating NRAs, SRAs and applicants. The SRA CRP can be based more frequently on positive scientific opinions, such as those issued by the EU-M4all procedure [Citation13]. As experience with the procedure increases, it is expected that there will be a more fluid communication and data exchange between stakeholders, leading to a greater reduction in the time to evaluate medicines and, consequently, faster regulatory approvals. This can be addressed in further publications.

Article highlights

The SRA CRP is a regulatory procedure that aims to facilitate and accelerate the regulatory approval of quality-assured, safe and effective medicines, relying on the expertise of SRAs.

Reliance enables a regulatory authority to use assessments performed by other regulatory authorities while remaining accountable for the final decision.

The evaluation of the SRA CRP pilot showed that this procedure improves the efficiency of regulatory processes, expediting the regulatory approval of medicines.

Given the benefits of the SRA CRP, more regulatory authorities and pharmaceutical companies should consider participating in this procedure.

The use of the SRA CRP contributes to the ultimate goal of facilitating earlier access to medicines for patients worldwide, improving global public health.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the authors and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the regulatory agency or organization with which the authors are employed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Assessment of medicines regulatory systems in sub-saharan African Countries. An Overview of Findings from 26 Assessment Reports; 2010. cited 2021 Jan 15]. Available from 2021 Jan 15: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/Assessment26African_countries.pdf

- Caturla Goñi M. Accelerating regulatory approvals through the World Health Organization collaborative registration procedures. Pharm Policy Law. 2016;18:109–120.

- World Health Organization. WHO support for medicines regulatory harmonization in Africa: focus on East African Community. cited 2021 Jan 15]. Available from 2021 Jan 15: https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/druginformation/DI_28-1_Africa.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization. Good reliance practices in the regulation of medical products: high level principles and considerations. cited 2021 Jun 29]. Available from 2021 Jun 29: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/55th-report-of-the-who-expert-committee-on-specifications-for-pharmaceutical-preparations* Guideline describing the use of the concept of reliance

- World Health Organization. Good regulatory practices in the regulation of medical products. cited 2021 Apr 16]. Available from 2021 Apr 16: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/55th-report-of-the-who-expert-committee-on-specifications-for-pharmaceutical-preparations

- World Health Organization [Internet]. List of Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRAs). cited 2021 Jan 15]. Available from 2021 Jan 15: https://www.who.int/initiatives/who-listed-authority-reg-authorities/SRAs

- World Health Organization [Internet]. WHO-Listed Authority (WLA). cited 2021 Jul 27]. Available from 2021 Jul 27: https://www.who.int/initiatives/who-listed-authority-reg-authorities

- World Health Organization. Collaborative procedure in the assessment and accelerated national registration of pharmaceutical products and vaccines approved by stringent regulatory authorities. cited 2021 Jan 15]. Available from 2021 Jan 15:http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272452/9789241210195-eng.pdf?ua=1** Guideline explaining the SRA CRP in detail.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Accelerated registration of medicines approved by SRAs. cited 2020 Dec 18]. Available from 2020 Dec 18: https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/medicines/faster-registration-fpps-approved-sras** Overview of the procedure

- World Health Organization. Procedure for prequalification of pharmaceutical products. cited 2021 Jan 17]. Available from 2021 Jan 17: https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/quality_assurance/TRS961_Annex10.pdf

- World Health Organization. Good practices of national regulatory authorities in implementing the collaborative registration procedures for medical products. cited 2021 Jan 17]. Available from 2021 Jan 17: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312316/9789241210287-eng.pdf?ua=1* Guideline on the implementation of collaborative registration procedures

- Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European parliament and of the council of 31 March 2004 laying down Community procedures for the authorisation and supervision of medicinal products for human and veterinary use and establishing a European Medicines Agency. cited 2021 Jan 15]. Available from 2021 Jan 15: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2004_726/reg_2004_726_en.pdf

- Cavaller Bellaubi M, Harvey Allchurch M, Lagalice C, et al. The European Medicines Agency facilitates access to medicines in low- and middle-income countries. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 2020;13(3):321–325. 10.1080/17512433.2020.1724782.