Abstract

This article critically examines the invocation of democracy in the discourse of audience participation in digital journalism. Rather than simply restate the familiar grand narratives that traditionally described journalism's function for democracy (information source, watchdog, public representative, mediation for political actors), we compare and contrast conceptualisations of the audience found within these and discuss how digital technologies impact these relationships. We consider how “participatory” transformations influence perceptions of news consumption and draw out analytic distinctions based on structures of participation and different levels of engagement. This article argues that the focus in digital journalism is not so much on citizen engagement but rather audience or user interaction; instead of participation through news, the focus is on participation in news. This demands we distinguish between minimalist and maximalist versions of participation through interactive tools, as there is a significant distinction between technologies that allow individuals to control and personalise content (basic digital control) and entire platforms that easily facilitate the storytelling and distribution of citizen journalism within public discourse (integrative structural participation). Furthermore, commercial interests tend to dominate the shaping of digital affordances, which can lead to individualistic rather than collective conceptualisations. This article concludes by considering what is gained as well as lost when grand visions of journalism's roles for democracy are appropriated or discarded in favour of a participation paradigm to conceptualise digital journalism.

Introduction

Democracy has long been a pivotal concept in analysing, evaluating, and critiquing journalism. Indeed, the coupling of the two is almost axiomatic; for centuries, especially in the Anglo-American world, a robust democracy has implied a free press, a “Fourth Estate more important far than they all” (Carlyle Citation1840), and still does to this day. Moreover, the industry traditionally asserts its institutional legitimacy and associated discourses of value based upon these classic democratic notions. It is a watchdog, a fourth estate, a representative of the people (McNair Citation2009). However, whereas the dominant, established discourses connecting journalism and democracy feature grand narratives and strong notions of democracy (and consequently high demands of journalism and high expectations of citizens), in the age of digital journalism the emphasis oftentimes seems to shy away from this to stress the interactional possibilities afforded by new media. In many articulations, the focus is not so much on citizen engagement but rather audience or user interaction; instead of theorising and empirically examining journalism's role for democracy (participation through news), the focus is on participation in news. Democracy does not so much feature as the main aim in this new wave of digital journalism, but is still an important part of the discourse surrounding it: democracy in journalism, rather than through it.

This has consequences for the institutional and societal position envisioned for journalism in a digital age and the associations we make with ideas of democracy, publics, and citizenship. Derivative concepts aligned with the idea of democracy, such as participation, interaction, and openness, are increasingly espoused by and coupled with mainstream professional journalism through its various user-based initiatives. However, the scope for participation that many of these opportunities provide is somewhat limited and their affordances are highly individualised. In this respect, allowing people more opportunities to interact with the “mass media” does not necessarily mean such practices translate to greater inclusivity or “thicker” forms of citizenship.

Conversely, rather than focus on changes in the “top down” mass media, many emphasise the emerging possibilities generated through new media initiatives. Niche journalism outlets are frequently posited as sites for more robust democratic notions such as civic empowerment and active citizenship. However, such initiatives exist largely at the margins, with far lesser reach than established news outlets, which does imply a fairly narrow “public” to which they are oriented. Accordingly, we must be wary of conceptualising the democratic efficacy of the changing media landscape in a manner that succumbs to a “reductionist discourse of novelty” that tends to privilege new media and laud the exceptional (Carpentier Citation2009, 408).

Whether one considers changes in established or emerging news outlets, one commonality is to situate the analytic centrality of transformations in terms of the institution and/or its technological initiatives. This way of thinking through the democratic possibilities of digital journalism follows a tendency in journalism studies to rely on “the audience” to justify the importance of change but to then subordinate it analytically to production, convergence, and content, and thus render it implicit (Madianou Citation2009). In this article, we focus on and attempt to clarify the discrepancy that arises from this decentring and address it by starting from the perspective of the audience. This double special issue of Digital Journalism and Journalism Practice looks to reassess theories on journalism and democracy in the current era, and we argue that an audience-centred, or at least audience-inclusive, perspective on the (democratic and societal) functions of journalism is crucial if we want theory that is not only internally consistent but also aligns with—and is testable against—people's lived experiences.Footnote1

The shift from a mass press to a more hybrid networked media ecology raises many questions for digital journalism in terms of the relationship between audiences and journalistic institutions. While by no means exhaustive or exclusive, we can posit that some combination of the following is likely (and to some extent in the latter cases, is already happening):

“Legacy” journalism outlets will somehow stabilise their increasingly precarious usage rates amongst audiences and/or strengthen cross-subsidy funding models to cement their standing as key societal institutions that safeguard democratic functions (such as informing audiences, acting as their representative conduit, and auditing the powerful for them).

New “niche” media outlets will take the place of older outlets, providing specialised democratic services, on an “as needed” basis, as part of more tailored and diversified media repertoires.

Media outlets claiming to do journalism in the classic democratic sense will be replaced by other forms of communication (direct address from governments and special interests, information curated and sourced by crowds, and so forth).

These scenarios form a forward-looking backdrop to the theoretical discussions entertained in this article. Underlying the question of significance in all of them is the question of how we view participation and the different ways we envision democracy and journalism's function within it through the eyes of the audience. More specifically, the political ramifications of such transformations are significant and demand specifying the particularities of the possible experiences of involvement that audiences have from the media they consume and engage with (Peters Citation2011). In this sense, the analytic aim of this article is to evaluate how the established political philosophies of journalism intertwine with the shifting particularities of journalism's audiences, both in terms of collective experience and individualised use, in an increasingly wired world.

We first discuss the traditional narratives that connect news to democracy, but rather than simply restate these familiar notions, we try to envision how the audience is conceptualised through such discourses. From here, we explore the ways new media technologies impact this relationship, and by association, the democratic functions of journalism. This leads to the next section of this article, in which we consider how “participatory” transformations impact how we view the practice of accessing politically and socially relevant information. This section draws out some initial analytic distinctions based on structures in which participation is embedded and the levels of engagement with digital journalism. The final section concludes by exploring how collective versus individualistic ways of conceptualising the democratic subject and the participatory tools made available to them potentially impacts journalistic purpose and production in a digital era.

The Grand Narratives of Journalism's Role for Democracy in the Digital Age

The roles attributed to journalism in most Western democracies are exceedingly familiar: we look to the news media to inform about issues of public concern; to function as a watchdog, monitor those in power; represent the public in political matters; and to mediate for political actors. While perhaps not in these specific terms, in the increasingly mediated landscape of the twentieth century these notions became familiar not only to scholars and journalists but also to the so-called “general public” itself (Hackett and Zhao Citation1998). The relationship is a prime example of a double hermeneutic: as the journalism industry and those who study it came to describe and configure its role in democracy, audiences came to engage with these definitions. This in turn shapes—and potentially changes—the roles journalism plays within society and our scientific understanding of it. Thus, it is instructive to review how four of the principal functions that journalism is attributed in democracy can be perceived in terms of their suggested relations to the audience, how people in turn may understand their position in this equation (cf. Loosen and Schmidt Citation2012), and how this may change in digital journalism. Interestingly, despite being the key stakeholder when it comes to journalism's democratic function, in many of these commonly understood roles, the relation with audiences is quite cursory and implicit. As Curran (Citation2011, 3) points out: “Much theorising about the democratic role of the media is conceived solely in terms of serving the needs of the individual voter.” This informing function is consequently a good place to start this review, as it is the most evident sine qua non of journalism's assumed benefit for the public.

The notion that journalism provides citizens with “information and commentary on contemporary affairs” (Schudson Citation2000, 58) is at the core of the discourse on journalism's central role in Western democracy and grounds much of its traditional rhetoric to audiences: “news should provide citizens with the basic information necessary to form and update opinions on all of the major issues of the day, including the performance of top public officials” (Zaller Citation2003, 110). Audiences here are typically assumed to be the aggregate of rationally engaged citizens (cf. Dahlberg Citation2011), selecting from a variety of news options to satisfy a need to stay informed. Even when practices are conceived of in lesser degrees than that of highly engaged, daily news consumption rituals, as with the notion of monitorial citizenship (Schudson Citation1998), or journalism functioning like a burglar alarm (Zaller Citation2003), the provision of quality information to citizens is core. Often cited as the most relevant function of the media, journalism is frequently faulted for not providing enough quantity or quality of coverage (e.g. Franklin Citation1997).

A second, related function is the view of journalism as a watchdog for society, which implies that journalists monitor and hold actors in power to account. Acting as a fourth estate, journalism is deemed to bring to light the wrongdoings and misdeeds of governmental actors, commercial businesses, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Central to this conceptualisation of journalism's role for society is then not the audience, apart from perhaps sourcing stories, but rather the journalist and the actors in power whose actions are monitored. It is only when a wrongdoing is reported that the audience comes into play as a “public”, in terms of its reaction and resultant demands placed upon officials. In this regard, journalism serves somewhat of an auditing function on audiences' behalf; the mere fact that media are there to check and control actions and processes in society has a function in itself. On this function too, journalism has been critiqued: in capitalist media systems it can be seen to be so tangled up with commercial and/or political interests that it is unable to act as an independent agent (e.g. McChesney Citation1999).

Third, news media are attributed an important role in representing the public in political matters: they are crucial in making the voice of the public heard. Here, the audience is central again, but this time as public subject to the media, as needing the media to talk for them. Having no means of publishing at the scale of mass media, journalism has been seen as the place for the public opinion to be formed, informing both political actors as well as other members of the public of their preferences, concerns, and opinions. This function may seem somewhat abstract to the audience; how, exactly do media make “them” heard and who are “they”? In this sense, the promotion of this function to audiences is largely rhetorical and intangible in a pre-participatory age. Again, major criticism exists as to the way in which journalists represent the public in that the public is seen to have limited control over its own mediated image and even less control over the ends for which this representation is deployed (Coleman and Ross Citation2010).

Finally, journalists mediate for political actors. News media are the main information source with regard to issues of public relevance and the “main vehicle of communication between the governors and the governed” (Strömbäck Citation2008, 230). This is a crucial part of understanding media's role in democracy during the age of mass media: for political actors to reach the public they go through (news) media. In theories on the mediatisation of institutional politics, we see that the focus is on the relation between political actors and journalistic media, and that the role of the audience is largely implicit (Witschge Citation2014). Building on agenda-setting theory, framing, and effect studies, the conceptualisation of the audience is largely passive. In this regard, media and politics may seem “distant” for audiences, as theories of public alienation from the political process and journalism's failure in this regard outline (e.g. Rosen Citation2006). In this theoretical perspective the public takes on a central role mainly as voters and as consumers of (political) information.

What all these conceptualisations of journalism vis-à-vis democracy hold in common is that they assume, at least in principal, that the public needs journalism even if it does not always actively engage with it. Minimally, it implies a threshold based on audiences consuming news from time to time and/or providing a justification for its financing. In an age of digital journalism, when these relationships and purposes are viewed from the perspective of audiences, and people potentially change their relationship with news itself, many fear that these democratic functions are destabilising (e.g. Mindich Citation2005). Ideas about journalism's role in society being under threat are far from unique to this era, and debates about its utility to audiences are not novel. Nonetheless, the vast proliferation of media options and outlets over the past few decades has made certain concerns quite tangible. Longitudinal surveys indicate that younger generations are turning away from news consumption as a common practice (e.g. Pew Research Center Citation2012) and established news habits for the population as a whole are slowly becoming de-ritualised, without any clear indication what will replace them (Broersma and Peters Citation2013). The question becomes: what significance will journalism continue to play for future generations?

Answering this is complicated further in a landscape where the interactional possibilities in terms of political communication change more broadly and digital tools make possible an increasingly participatory role for audiences, both within and outside news journalism. Each of the four functions previously outlined can now, in theory, be conducted by the public and political actors directly, without the intervention, or mediation, of journalists. News is now produced and distributed by a myriad of actors, not just those in the institutional domain of “mass media” journalism, and thus political and other societally relevant information is provided by journalistic as well as non-journalistic actors. The role of watchdog is similarly taken over or at least available to other actors, whether activists, NGOs, or members of the public themselves, for instance through the actions of whistleblowers and crowdsourced data sets. The third function discussed, that of representing the public, is maybe the most prominent example of the potential provided by digital tools: they allow the public to circumvent, or challenge, dominant institutional news media by distributing “more widely the capacity to tell important stories about oneself—to represent oneself as a social, and therefore potentially political, agent” (Couldry Citation2008, 386).

In this regard, one of the main changes is the erosion of the gatekeeping role that helped define the relation between politics and journalism in the era of mass communication (Schulz Citation2004). This gatekeeping function made news media a powerful actor in political communication and for democracy but the extent to which this pertains to the digital era has been questioned. New media are argued to lift the barriers of communication and consequently take away news media's monopoly on mass communication and disable journalism's gatekeeping function (Hansen Citation2012). Political actors have the possibility to communicate directly to audiences without necessarily going through traditional media and new possibilities are widely available to the public to access, publish, and interact with information online.

In short, digital tools are argued to enable and encourage users “to participate in the creation and circulation of media” (Lewis Citation2012, 847) and this participation affects journalism's role (and that of the audience) in democracy. In this respect, the key changes—from the perspective of the audience or user—to the four positions above could be summarised as:

Information source: Mass media move from being a primary way for audiences to be informed to one of many possibilities.

Watchdog: News media still publish misdeeds, but whistleblowers augment traditional investigative journalism and citizens can increasingly publicise misconduct.

Public representative: Citizens groups can unite and bypass journalism to communicate their issues directly as “publics”.

Mediate for political actors: Digital tools allow more unfettered access from politicians and other political actors to citizens and vice versa, circumventing journalism.

What these potentialities point to is a possible shift in the paradigm through which journalism is viewed by academics, spoken about by news organisations, and engaged with by audiences. We see that increasingly a “participation paradigm” rather than a “mass communication paradigm” is applied to conceptualise the institutional setting of journalism (cf. Livingstone Citation2013). Furthermore, the industry promotes this change in its rhetoric of purpose to audiences, emphasising a different set of practices for digital journalism and its consumption, and connecting the implementation of digital tools now available to the empowerment of audiences in the news production process. In this way of thinking and the initiatives being developed under it, we see that the idea of democracy shifts. There is a distinction between prominent conceptualisations of digital journalism, in which audiences are seen as active co-participants, invoked to argue that journalism is becoming democratised, and that of the former grand narratives, wherein audiences were mostly separate from journalism, which facilitated different democratic functions on its behalf.

Envisioning Participation in Digital Journalism

In recent literature on journalism, and within rhetoric emanating from the industry itself, an increasing emphasis is placed on embracing a move towards participation (e.g. Singer et al. Citation2011). Partially, this is a response geared towards potential economic benefit; in the age of Web 2.0 discouraging audience interaction may be seen as an isolating or losing proposition. However, while revenue generation may be part of the equation, there is an alternative discourse surrounding participation, which valorises it in terms of its democratising effect on media. In light of the focus of this article, we see that when the affordances of digital technologies are invoked, the focus is placed more squarely on journalism–audience interaction as opposed to a broader dialectic surrounding journalism's democratic function for citizens in society. Embracing participation, in this sense, potentially bestows a less meaningful role for journalism than was envisioned under the familiar grand narratives in the era of the mass press.

This refocusing is not unique to digital journalism studies, as recent scholarship has increasingly viewed media consumption in general in terms of such a “participation paradigm” (Livingstone Citation2013). This emphasises not only a lessening of barriers between the traditional mass media and the “people formerly known as the audience” (Rosen Citation2006), and the rise of more “networked” forms of mass communication (Cardoso Citation2008), but also stresses the contributory and creative potentialities of the digitised, Web 2.0 media landscape (Gauntlett Citation2011). Many such accounts are careful not to assert that all participation is uniform and there is a long history of delineating the notion, especially when it comes to the question of what constitutes political participation. Moreover, from a socio-cultural perspective, participation via the news media is but one of a far more dynamic series of interactions that constitute civic engagement.

However, given the societal importance attributed to the provision of a common, consistent source of information, and the role of journalism in providing frameworks of meaning, the particular domain of participation through journalism is one of central importance. Through its reach, journalism potentially allows the shaping of communities of interest, permitting participation both for more “passive”, disengaged citizens (by way of providing information) as well as active, engaged citizens (by way of providing tools for direct participation). Yet despite the fact that both minimalist and maximalist forms of participation are theoretically possible through news media, they are not equally present in the digital domain. While a select group of media provide the platform for maximalist engagement in helping produce and shape meanings and perhaps even communication structures within society, these are not the dominant form.

What is needed are clearer distinctions, considering the specifics of participation in digital journalism, its means, and its ends. Instead of simply celebrating new media technologies for their potential for participation, we need to question what makes their use meaningful, both in terms of the experience of using them and in terms of their material integration within everyday life. While there are an ever-increasing number of ways for the public to be involved in the news process, there are a more limited number of discussions of the different affordances and structural differences of participation and—quite crucially—the consequences of participatory digital tools and the extent to which such opportunities are actually available equally to different social groups. It would be erroneous to treat the current possibilities for audience engagement in traditional news media, whether we refer to “most-read” lists, “have-your-say” invitations, audience polls, “comments” sections or “send-in-your-pictures” requests, as equally promising avenues for public participation.

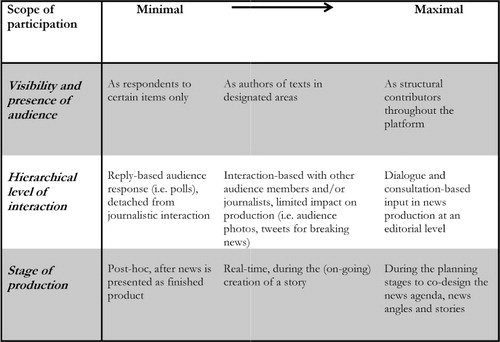

Similarly, journalistic initiatives facilitated by digitalisation like Indymedia may provide a space outside traditional mainstream journalism for alternative voices, with much greater scope for distribution online. But to ignore the structural disadvantages that beset such organisations (lack of access, lack of material resources and infrastructure, lack of viable financing and tax advantages, lack of prominence versus more established outlets, lack of salaried employees with time to devote to its maintenance, and so forth) easily overstates their emancipatory potential (for a critical discussion of the potential for alternative media online, see Curran and Witschge (Citation2010). In this respect, distinguishing between forms of participation and their implications allows us to make a more constructive assessment of current practices (see ). The operationalisation of interactive features and the structures within which they are integrated in this respect belie more robust notions of participation.

Expressed broadly, as notes, there is a significant distinction in the scope and degree of participation between technologies that allow individuals to control and personalise content (basic digital control) and entire platforms that easily facilitate the storytelling and distribution of citizen journalism within public discourse (integrative structural participation).

This realisation points us towards the necessity of distinguishing the scope for which citizen-led contributions are welcomed. Is participation specific to a single story, across certain sections (i.e. “Comment is Free”), or a principle of the entire publication (a fully realised “public journalism”)? This is an important aspect in terms of the possible entry points in the text itself and within processes of production. Whether individual audience members are interested in involvement or not, the idea of co-production, crowdsourcing, and co-creation speak to how visible and present the public is as author, not just as audience. News websites are typically sectioned off with audiences cordoned in specific places and moments where participation is made available.

This relates to a second crucial distinction, the organisational permeability and hierarchical level of participation, which is central to understanding power relations and the level at which connection is enabled. Are audiences able to reply only to institutional requests or is this extended to interaction with other members of the audience and journalists? To what extent can audience participation be extended to dialogue and structural consultation with the editorial department or even financial department? Participation is often equated with a greater equalising of the relationship between audiences and the mass media but the organisational level to which they are welcomed differentiates this sharply. Most participation remains outside the control of production and the editorial process as a whole remains a level quite impervious in most digital initiatives.

Finally, a consideration that often goes unexplored is the timing of participation, in terms of during what stage of production it is made available. Is it limited to post hoc responses, extended to real-time co-production (such as that witnessed with live-blogging), or integrated in pre-coverage organisational integration and story development? These different moments and phases of possible connection delimit the ability to set the day-to-day agenda of news organisations. While the rhetoric of participation appears to suggest an opening up of journalism and inclusion of audiences as key stakeholders to help fulfil the functions of journalism, the breadth of participatory opportunities may not be matched by a comparable depth.

If we look at actual journalistic practices—even in a digital age where participation is frequently emphasised as a panacea against journalism's perceived growing disconnect with audiences—at most outlets: the contribution of audiences is still distinctly and visibly separated from that of journalists and editors; power has not been transferred from the institution; and audience response is welcomed mostly after-the-fact as a possible citizen source or commenter. These distinctions highlight a main challenge that hinders meaningful participation being established on behalf of audiences, namely the divide between the private and public interests served by it. Meaningful participation, allowing for a more democratic distribution of the power to speak not only in the news but also within the newsroom, ideally leads to a more symbiotic relationship between news organisations and audiences and more diversity in media voices. A classic critique of media is that minority viewpoints have a hard time being heard, but if we extend this to the entire news production process, we might say that audiences as a whole traditionally exert little control. Day-to-day, this is likely unproblematic for most people. They are not journalists, have no historical basis for assuming they should help determine the news agenda, and likely are generally disinterested in having such expectations foisted upon them.

However, there is a large swathe of territory between demanding full participation and governance over journalism by audiences versus offering mere token participation. We should remember that media have an important role in voicing opinions and are needed to make “contemporary contests” visible (Couldry Citation2010, 148). As we see time and time again, the power for individuals to influence coverage when a group they are part of is suddenly thrust on to the front pages—from ethnic minorities during riots, to striking teachers, even to investment bankers—is demonstrated to be little. Many of the classic notions of primary definers setting the terms of debate and secondary definers only being allowed to respond still seem to hold true, even in the current “age of participation”. Even with ever-increasing interactive possibilities in mainstream media, the public “does not control its own image” (Coleman and Ross Citation2010, 5).

News organisations are inevitably “embedded in networks of commercial and political power” (Couldry Citation2010, 148) and the way in which the public is allowed to participate is heavily shaped by these interests. In the most ardent, some might say instrumental, political economy assessment of the media system, audiences are viewed as nothing more than a market to sell to advertisers, and journalism is little more than a technology of capitalism that consolidates the public and renders it controllable. A different view of the role of audience, through an adapted field theory perspective, might view participation as a struggle which threatens journalism's status as the arbiter and key distributor of day-to-day public information in societies. Under this logic, public participation through online news does not escape the tendency that news media have to “create a public opinion that amplifies, or at least, does not challenge, their own power” (Hind Citation2010, 7).

This is relevant, as it raises questions over what new kinds of citizenship the currently available tools facilitate, if any at all? In terms of the four functions traditionally assigned to journalism, we see that the public is not equally attributed a role in fulfilling them, and mainstream journalists seek to maintain their gatekeeping role (Witschge Citation2013). As such, participatory tools are employed in a selective fashion, and journalism is a long way from allowing audiences to share information jointly, co-monitor those in power, represent themselves in public affairs, and get into contact with political actors directly. This may not be surprising, given the commercial pressures and the continued (self-)understanding of journalism as a separate profession. However, the rhetoric that connects these tools to democracy often suggests that a fundamental shift of power is occurring and invokes a stronger role for the audience than that with which it is currently furnished. On the whole, practices in mainstream journalism contradict expectations or presumptions that the “new digital environment has jolted traditional journalism out of its conservative complacency; [or that] news operations are much more responsive to their empowered and engaged audiences” (Bird Citation2009, 295).

Commercial considerations frequently weigh more heavily than any moral motivations in the new relationship between the professionals and the audience, such as creating a more democratic environment. Yet even outside the mainstream, the potentialities of Web 2.0 have been critiqued for the limited version of citizenship they afford. Fenton and Barassi (Citation2011, 180) note that whereas alternative media were founded on a collective ethos and a collectively negotiated construction in response to perceived structural inequalities, the recent emphasis on using social media promotes individual agency and “self-centred forms of communication”. These sorts of structural considerations should lead us to question paradigmatic assertions of the intrinsic value of participation from digital journalism initiatives—or at least to critique their assumed political efficacy on behalf of the audience.

Discussions on the value of participation are quite meaningless unless we strive to understand the utility of different participatory tools for audiences, which demands not only empirical research on the way they are experienced but also specificity on their different affordances and implications. While on the surface it may seem that technology is making it increasingly simple for individuals to integrate personalised news within every space and place of their daily lives, and news organisations are increasingly emphasising their capabilities around the convenience for audiences to interact (Peters Citation2012), this does not necessarily translate into more inclusive forms of participation. This is further problematised when we consider the dislocation of journalism for many people, the lack of integration of news in their everyday lives, and the segregation of participation in new virtual spaces in terms of the ability to participate equally (Shakuntala Banaji, personal communication, October 11, 2013). Understanding the lived materiality of technological developments means greater specificity about said efforts at interaction and inclusion. Such particularities of participation not only illustrate its potential shape, scale, and substance for audiences, it also, quite tellingly, clarifies the ways audiences themselves are conceived.

The Participatory Individual and the Democratic Collective in Digital Journalism

Classically, journalism is conceived of as an intermediary of sorts, a social institution that serves a number of bridging functions between the populace and the political process. In terms of its civic role, this means discussions typically distinguish some aspect of this relation, whether it is centred on journalism's function in competitive, deliberative, procedural, or participatory visions of democracy (Strömbäck Citation2005), or people's likely uses of journalism as they move from being conceived of as informed to monitorial citizens (Schudson Citation1998). Such discussions have often taken a normative and prescriptive stance in terms of how journalism can “best” serve the civic needs of the public, and this trend has continued when considering new digital initiatives. For instance, Nip (Citation2006) looks more closely into how the second phase of public journalism could use participatory tools to strengthen democratic values in terms of deliberation, engagement, and community connection. While these sorts of accounts look to the nature of democracy imagined, the subjects within it, and the role of journalism envisioned, they tend to conceive of this relation in terms of the institution of journalism and the tools it makes available to audiences. The risk with such an approach is that it can fall prey to considering the instrumental means of digital initiatives as opposed to the “ends” with which people actually use them (cf. Dahlberg Citation2011).

The popular rhetoric increasingly emanating from journalistic institutions around the question of participation often emphasises such instrumental means, which parallels a proclivity observed in analyses of online journalism to focus on technological innovation (Steensen Citation2011). These types of institutional discourse, closely tied to marketing strategies, tend to privilege how digital tools facilitate individuals' possibilities to interact and exert greater control over shaping the information offered to them. As we noted in the first part of this article, traditional discourses of journalism tend to be framed collectively in terms of saying what journalism can do for people, what it offers citizens in democracy. But in discourses of participation, we frequently see emphasis placed on what individuals can do with journalism. For journalism studies scholars, this is an important caveat. When the tools of digital journalism are viewed primarily in terms of how people can possibly use them as opposed to the impact of their uses, there is a danger of making individualised interactional possibilities trumpet questions of communicative collectivity (cf. Livingstone Citation2003).

Rather than assuming the democratised nature of interactive journalism, we need to view journalism's role through the eyes of audiences and question the rhetoric surrounding digital tools. As Rebillar and Touboul (Citation2010, 325) point out, in the “libertarian-liberal” model currently dominant, “views of the Web 2.0 associate liberty, autonomy and horizontality”. But these are more often than not highly individualised notions of political engagement. Moreover, it is not clear if people want or even conceive of themselves in the more active senses embodied in the idea of user or “produser” (cf. Bruns Citation2006). Empirical studies of audiences and their changing experience with digital journalism—as opposed to the more common approach to study journalistic and editorial perceptions of what change means to audiences—tend to bear this out. Bergström's (Citation2008) early study of online participation in Sweden found relatively little interest from audiences in terms of content creation. Furthermore, the (already politically and socially engaged) minority which did comment did so for reasons of leisure as opposed to democratic engagement. Similarly, Costera Meijer's (Citation2013) multiple studies in the Dutch context note the existence of a widely different logic operating between what users value in terms of participation—being taken seriously as individuals and a collectivity with wisdom and expertise to offer—and the professional scepticism with which journalists traditionally view more “inclusive” initiatives. Such research points to the fact that audience-based studies tend to highlight areas of tension and resistance between their empirical findings and the common discourse about digital, active, participatory audiences and the possible impact this has on democracy.

Such considerations alert us to what Silverstone (Citation1999, 2) referred to as “the general texture of experience”, which is why it is important to study the coupling of journalism and democracy not just from the perspective of the institution and its rhetoric, but also from its audiences and their practices. By foregrounding experience, rather than declaring the democratic impact of prominent shifts and technological advancements based on journalistic (or academic) want or intention, it forces us to begin from the perspective of the audience. If we begin from the premise that all forms of possible interaction with journalism are not equal in terms of their ability or even intent to promote audience agency in the news production process, the natural corollary of this is that audiences likely experience their own agency differently, depending on the participatory nature of their actual involvement.

For these reasons, the use of democratic discourses in relation to participative journalism should be exercised cautiously. The logics that drive the introduction of digital tools may not warrant the use of grand conceptualisations of democracy and the audience practices and experiences that accompany them may also challenge such narratives. However, at the same time, we wish to emphasise here how a singular focus on participation can lead to overly cautious expectations. In this regard we are faced with a bit of a conundrum. We sympathise with the concern raised by some authors (see the 2013 special issue of Journalism guest edited by Josephi) that with the rapid changes witnessed in the media landscape over the past couple of decades, the journalism and democracy paradigm may be “too limiting and distorting a lens through which journalism can be viewed in the 21st century” (Josephi Citation2013, 445). There may indeed be much to be gained from retiring the concept of democracy for understanding contemporary journalistic practice (Nerone Citation2013; Zelizer Citation2013); considering alternative, possibly more relevant concepts to replace the central role of democracy as the framework to make sense of key shifts and changes.

However, as this article hopefully illustrates, simply replacing the “democracy paradigm” with a “participation paradigm” to analyse digital journalism carries some risks. It became clear that while the concept of democracy is invoked in digital journalism studies to frame discussions on participation, this conceptualisation is at a different level than the grand narratives that have traditionally stipulated journalism's functions for democracy. The danger when we speak mostly in terms of participation is potentially sacrificing much of journalism's collective function, to which traditional discourses of mass media were quite attuned. This is not to say that these grand narratives should necessarily be our guideline when reviewing journalism and/or participation in and through journalism: there are a variety of ways in which democracy can be constituted through acts of the public. However, it is important to distinguish between the participatory affordances, the lived experiences of audiences, and the implications for journalism's relevance and function in society.

A journalism that consistently heralds the ability for the audience to personalise and interact based around new technological tools may gradually promote individualistic interpretations that are anathema to the idea of journalism's traditional collective, public ethos. Collectivity is a crucial aspect not only of democracy, but dare we say, of society/public life. While digital tools may promote connection in a very literal sense, these are not the same forms of “public connection” emphasised under the old grand narratives (cf. Couldry, Livingstone, and Markham Citation2010). News organisations signal much to us about our preferred societal roles, civic possibilities, and democratic responsibilities, and what they advocate is potentially transforming in the digital age. Are audiences still envisaged as citizens who “are actively engaged in society and the making of history” or rather as consumers who “simply choose between the products on display” (Lewis, Inthorn, and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2005, 5–6)? The technologies of digital journalism may appear to plug into an audience that is assumed to value both simultaneously, but the individualised nature of connecting, personalising, and choosing when to be “part of the conversation” is foregrounded. More interactivity, in this regard, should not be automatically equated with a greater role for citizens to perform democratic functions. Moreover, the focus on individualised forms of participation may mean that the collective functions of journalism are neglected. In this regard, there is a relationship—and potentially a paradox—between discourses of empowerment and participation (that for the most do not distinguish between different levels of agency) and the actual practices and affordances of technological tools. As journalism scholars we need to examine critically the minimal expectations and affordances of participatory tools as well as consider what may be lost with the increasingly individualistic interpretation of both journalism and participation. This would involve empirically examining the experiences of audiences as both users and citizens simultaneously, as the changes we have outlined do beg the question: what are the implications for democracy if what was once deemed a collective institution begins to envisage its audiences as individuals?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to an anonymous reviewer as well as the guest editors of this special issue, Steen Steensen and Laura Ahva, for their helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Notes

1. It is important to note that there is a difference between the “audience” as a discursive construct versus the audience as an empirically studied entity. In this article we look primarily at its discursive formulation in the rhetoric of journalism and democracy. Yet of course, these notions are not completely distinct and interact in a number of ways. As we discuss in the first section after the introduction, the established discourse about the societal function of journalism has been internalised by the public and shapes how people traditionally perceive news. However, as we note in the final section, empirical studies of audiences illustrate tensions between this rhetoric and the actual uses audiences make from journalism and their experiences of participatory and interactive tools.

REFERENCES

- Bergström, Annika. 2008. “The Reluctant Audience: Online Participation in the Swedish Journalistic Context.” Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 5 (2): 60–80.

- Bird, Elizabeth. 2009. “The Future of Journalism in the Digital Environment.” Journalism 10 (3): 293–295. doi:10.1177/1464884909102583.

- Broersma, Marcel, and Chris Peters. 2013. “Rethinking Journalism: The Structural Transformation of a Public Good.” In Rethinking Journalism: Trust and Participation in a Transformed News Landscape, edited by Chris Peters and Marcel Broersma, 1–12. London: Routledge.

- Bruns, Axel. 2006. “Towards Produsage: Futures for User-led Content Production.” In Cultural Attitudes towards Communication and Technology, edited by Fay Sudweeks, Herbert Hrachovec, and Charles Ess, 275–284. Perth: Murdoch University.

- Cardoso, Gustavo. 2008. “From Mass to Networked Communication: Communicational Models and the Informational Society.” International Journal of Communication 2: 587–630.

- Carlyle, Thomas. 1840. On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1091/1091-h/1091-h.htm.

- Carpentier, Nico. 2009. “Participation Is Not Enough: The Conditions of Possibility of Mediated Participatory Practices.” European Journal of Communication 24 (4): 407–420. doi:10.1177/0267323109345682.

- Coleman, Stephen, and Karen Ross. 2010. The Media and the Public: “Them” and “Us” in Media Discourse. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Costera Meijer, Irene. 2013. “Valuable Journalism: The Search for Quality from the Vantage Point of the User.” Journalism 14 (6): 754–770. doi:10.1177/1464884912455899.

- Couldry, Nick. 2008. “Mediatization or Mediation? Alternative Understandings of the Emergent Space of Digital Storytelling.” New Media & Society 10 (3): 373–391. doi:10.1177/1461444808089414.

- Couldry, Nick. 2010. Why Voice Matters: Culture and Politics after Neoliberalism. London: Sage.

- Couldry, Nick, Sonia Livingstone, and Tim Markham. 2010. Media Consumption and Public Engagement: Beyond the Presumption of Attention. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Curran, James. 2011. Media and Democracy. Oxon: Routledge.

- Curran, James, and Tamara Witschge. 2010. “Liberal Dreams and the Internet.” In New Media, Old News: Journalism and Democracy in the Digital Age, edited by Natalie Fenton, 102–118. London: Sage.

- Dahlberg, Lincoln. 2011. “Re-constructing Digital Democracy: An Outline of Four ‘Positions.’” New Media & Society 13 (6): 855–872. doi:10.1177/1461444810389569.

- Fenton, Natalie, and Veronica Barassi. 2011. “Alternative Media and Social Networking Sites: The Politics of Individuation and Political Participation.” The Communication Review 14 (3): 179–196. doi:10.1080/10714421.2011.597245.

- Franklin, Bob. 1997. Newszak and News Media. London: Arnold.

- Gauntlett, David. 2011. Making Is Connecting. London: Polity.

- Hackett, Robert A., and Yuezhi Zhao. 1998. Sustaining Democracy?: Journalism and the Politics of Objectivity. London: Broadview Press.

- Hansen, Ejvind. 2012. “Aporias of Digital Journalism.” Journalism 14 (5): 678–694. doi:10.1177/1464884912453283.

- Hind, Dan. 2010. The Return of the Public. London: Verso.

- Josephi, Beate. 2013. “De-coupling Journalism and Democracy: Or How Much Democracy Does Journalism Need?” Journalism 14 (4): 441–445. doi:10.1177/1464884913489000.

- Lewis, Justin, Sanna Inthorn, and Karin Wahl-Jorgensen. 2005. Citizens or Consumers? What the Media Tell Us About Political Participation. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Lewis, Seth. 2012. “The Tension between Professional Control and Open Participation.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 836–866. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.674150.

- Livingstone, Sonia. 2003. “The Changing Nature of Audiences: From the Mass Audience to the Interactive Media User.” In The Blackwell Companion to Media Research, edited by Angharad Valdivia, 337–359. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Livingstone, Sonia. 2013. “The Participation Paradigm in Audience Research.” The Communication Review 16 (1–2): 21–30. doi:10.1080/10714421.2013.757174.

- Loosen, Wiebke, and Jan-Hinrik Schmidt. 2012. “(Re-)Discovering the Audience: The Relationship between Journalism and Audience in Networked Digital Media.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 867–887. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.665467.

- Madianou, Mirca. 2009. “Audience Reception and News in Everyday Life.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 325–337. London: Routledge.

- McChesney, Robert W. 1999. Rich Media, Poor Democracy: Communication Politics in Dubious Times. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- McNair, Brian. 2009. “Journalism and Democracy.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 237–249. London: Routledge.

- Mindich, David. 2005. Tuned Out: Why Americans Under 40 Don't Follow the News. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nerone, John. 2013. “The Historical Roots of the Normative Model of Journalism.” Journalism 14 (4): 446–458. doi:10.1177/1464884912464177.

- Nip, Joyce. 2006. “Exploring the Second Phase of Public Journalism.” Journalism Studies 7 (2): 212–236. doi:10.1080/14616700500533528.

- Peters, Chris. 2011. “Emotion Aside or Emotional Side? Crafting an ‘Experience of Involvement’ in the News.” Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism 12 (3): 297–316. doi:10.1177/1464884910388224.

- Peters, Chris. 2012. “Journalism to Go: The Changing Spaces of News Consumption.” Journalism Studies 13 (5–6): 695–705. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2012.662405.

- Pew Research Center. 2012. “Trends in News Consumption 1991–2012.” http://www.people-press.org/files/legacy-pdf/2012NewsConsumptionReport.pdf.

- Rebillar, Franck, and Annelise Touboul. 2010. “Promises Unfulfilled? ‘Journalism 2.0’, User Participation and Editorial Policy on Newspaper Websites.” Media, Culture & Society 32 (2): 323–334. doi:10.1177/0163443709356142.

- Rosen, Jay. 2006. “The People Formerly Known as the Audience.” PressThink. http://archive.pressthink.org/2006/06/27/ppl_frmr.html.

- Schudson, Michael. 1998. The Good Citizen. New York: Free Press.

- Schudson, Michael. 2000. “The Domain of Journalism Studies around the Globe.” Journalism 1 (1): 55–59. doi:10.1177/146488490000100110.

- Schulz, Winfried. 2004. “Reconstructing Mediatization as an Analytical Concept.” European Journal of Communication 19 (1): 87–101. doi:10.1177/0267323104040696.

- Silverstone, Roger. 1999. Why Study the Media? London: Sage.

- Singer, Jane B., David Domingo, Ari Heinonen, Alfred Hermida, Steve Paulussen, Thorsten Quandt, Zvi Reich, and Marina Vujnovic. 2011. Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Steensen, Steen. 2011. “Online Journalism and the Promises of New Technology: A Critical Review and Look Ahead.” Journalism Studies 12 (3): 311–327. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2010.501151.

- Strömbäck, Jesper. 2005. “In Search of a Standard: Four Models of Democracy and Their Normative Implications for Journalism.” Journalism Studies 6 (3): 331–345. doi:10.1080/14616700500131950.

- Strömbäck, Jesper. 2008. “Four Phases of Mediatization: An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 13 (3): 228–246. doi:10.1177/1940161208319097.

- Witschge, Tamara. 2013. “Digital Participation in News Media: ‘Minimalist’ Views versus Meaningful Interaction.” In The Media, Political Participation and Empowerment, edited by Richard Scullion, Roman Gerodimos, Daniel Jackson, and Darren Lilleker, 103–115. London: Routledge.

- Witschge, Tamara. 2014. “Passive Accomplice or Active Disruptor: The Role of Audiences in the Mediatization of Politics.” Journalism Practice 8 (3): 342–356. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.889455.

- Zaller, John. 2003. “A New Standard of News Quality: Burglar Alarms for the Monitorial Citizen.” Political Communication 20 (2): 109–130. doi:10.1080/10584600390211136.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2013. “On the Shelf Life of Democracy in Journalism Scholarship.” Journalism 14 (4): 459–473. doi:10.1177/1464884912464179.