ABSTRACT

For financial reasons, newspapers and magazines are increasingly going online-only. By doing so, some have returned to profitability, but with what consequences for their audiences? To expand the scant evidence base, we conducted a case study of the UK’s New Musical Express (NME) magazine. By analyzing quantitative audience data from official industry sources, we estimate total time spent with the NME by its British audience fell dramatically post-print—by 72%. This fall mirrors that suffered by The Independent newspaper, which went online-only two years earlier. We also report that the NME’s official net weekly and monthly readership increased post-print, although these results are difficult to compare with The Independent’s because the two titles differed in their print publication frequencies. We conclude that the attention periodicals attract via their print editions is unlikely to immediately transfer to their online editions should they go online-only. Building a fuller theory of print platform cessation, however—one that also encompasses changes in readership/reach—requires more comparable data. This case study provides further evidence to suggest that though, for newspapers and magazines, a post-print existence may be less costly, it is also more constrained, with much of the attention they formerly enjoyed simply stripped away.

Introduction

Periodicals are increasingly ending their print editions and going online-only. Those that have done so include the newspapers La Presse in Canada and Taloussanomat in Finland, and the magazines Marie Claire (UK), Company, and Glamour.Footnote1 The reasons for this are usually understood to be financial. As the circulations of printed publications have declined, print advertising revenues have also fallen, and have not been replaced by revenues from digital advertising (Nielsen Citation2016). Going online-only allows periodicals to shed the huge costs involved in print production and distribution while also allowing them to focus on reaching much larger global audiences online or to pursue a paywall strategy.

Indeed, going online-only has propelled some periodicals back to profitability, but with what consequences for their audiences? Information about this is limited. To expand the evidence base, we present in this article a case study of the UK’s New Musical Express (NME), which, after 66 years in print, went online-only in March 2018. At that time, the NME’s print circulation—of around 300,000—was close to an all-time high due to its decision, in 2015, to become a freesheet. However, due to increasing production costs, and a tough print advertising market, NME’s publisher, Time Inc., decided to pull the plug on print.

In the absence of what we might call a theory of media platform cessation, our general hypothesis draws on media displacement research and also on studies about the uses people make of print media, and the gratifications they receive as a result. Our review of the relevant media displacement literature suggests that relatively few readers stop consuming magazines’ print editions as a direct result of the introduction of web versions. Furthermore, the qualitative research we examine shows that the physical form of newspapers and magazines has been central to how and why they are used. Taken as a whole, this evidence leads us to hypothesize that, when we examine the audience effects of the NME’s withdrawal of its print edition, we should not expect a sudden surge in the reading of its online edition.

We test our general hypothesis by analyzing changes, post-print, to the NME’s net readership and the attention it attracts—measured using the estimated annual time spent reading the brand by its audience. The data for our analysis come from the UK’s official sources of print and internet audience data, the Publishers Audience Measurement Company (PAMCo) and Comscore.

We estimate that, after the switch, the attention the NME received via PCs and mobiles changed little. In other words, the time readers spent reading the magazine in print did not transfer to its online edition once the print version became unavailable. In the Discussion section, we observe that this finding mirrors the outcome at The Independent, which went online-only two years earlier (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2018). We also report that the NME’s official net weekly and monthly readership numbers increased in the 12 months after it went online-only compared with the 12 months before. However, there are methodological issues that mean we must interpret these readership numbers with caution and avoid comparing them directly with those of The Independent—because of how the two titles differed in their print publication frequency.

We conclude the article by asking whether, with the evidence we now have from two quite different case studies, we are able to start to construct what we call a theory of print platform cessation. Our answer is a qualified “yes”. We think that, in many cases, the temporal attention periodicals attract via their print editions is unlikely to immediately transfer to their online editions should they go online-only. However, we do not, yet, have enough comparable data to be able to fully generalize the effects of going online-only on net readership/reach.

We end this Introduction by providing, for context, a short history of the NME. There then follows our literature review, general hypothesis, and research questions. A description of our data sources and methods comes next, succeeded by the presentation and discussion of our results. Finally, we draw our wider conclusions.

The NME

The New Musical Express (NME) began in 1952 as a weekly popular music paper (Sweney Citation2018). It reached a sales peak in 1964 when its coverage of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones helped to propel it to a circulation of “almost 307,000” (Sweney Citation2018). In the 1970s, it was notable for its championing of punk, and then, later, new wave and indie acts. In the 1990s, it “was at the forefront of Britpop” (Sweney Citation2018). An online version, NME.com, was launched in 1996 (Chester Citation2011).

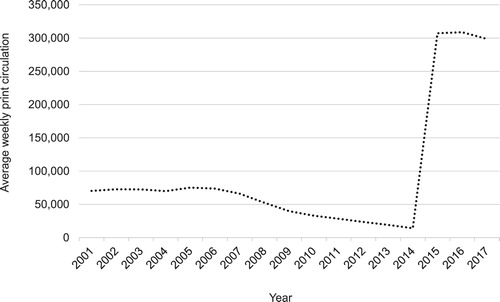

The noughties saw “falling sales and ad revenue” and the print edition fell into the red (Sweney Citation2018). Circulation fell from around 76,000 in 2005 to around 15,000 by the end of 2014 (see ). In September 2015, the magazine was relaunched as an ad-funded freesheet (Sweney Citation2015), distributed at transport hubs, universities, and retail outlets (Turvill Citation2015). The move to free boosted the magazine’s circulation to over 300,000, with the figure at one point surpassing the 1964 peak (Sherwin Citation2016), and provided a fillip to the brand’s online performance (Sweney Citation2018). The move to free also prompted a rise in ad revenue, which reached its highest point in 15 years (Turvill Citation2015). As the figures rose, however, the paper’s critical stock fell. It was claimed that the “NME’s firebrand voice had been all but extinguished in the print edition’s latter-day incarnation as a please-all freesheet” (Clarke Citation2018). There were also reports of vendors struggling to give away their copies (Snapes Citation2018).

Figure 1. Average weekly print circulation of the NME, 2001–2017. The 2015 figure is an average for November–December of that year only. The figures include circulation in countries outside the UK and the Republic of Ireland, which averaged 7% of the total. Source: Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC).

It soon became apparent that the freesheet figures were breaking records without balancing the books. In March 2018, 66 years of print publication came to an end following the decision to take the magazine online-only. Though the freesheet had produced increased ad revenue, the increase was less than forecast (Mayhew and Kakar Citation2018). The magazine’s owner, Time Inc., stated that the brand had “faced increasing production costs and a very tough print advertising market” and that it was “the digital space” where effort and investment would be focused in the future (Sweney Citation2018). The ditching of the print edition apparently bore financial fruit, with the NME’s editor, Charlotte Gunn, claiming that from “the moment we closed the print mag we were a profitable business again” (Clarke Citation2018). By November 2018, the number of unique monthly users was claimed to be the highest in the website’s 22-year history (Clarke Citation2018).

Literature Review

Where can we look for guidance about the possible changes to a magazine or newspaper brand’s audience when it stops printing and goes online-only? In part, because such circumstances are a relatively rare—and recent—phenomenon, there is not a comprehensive theory of what we might call media platform cessation. There are, however, three case studies—all concerning newspapers—that are of direct relevance. There are also a number of studies about the uses people make of print media, and the gratifications they receive as a result, that offer clues about how audiences may behave when a periodical’s print edition is withdrawn.

Media Displacement and Coexistence

We will start, however, by examining the concepts of media displacement and media coexistence, which concern changes in audiences’ media consumption as new media forms are introduced and adopted. These concepts, which are relatively well developed, may help shape our expectations. Media displacement theory suggests that increasing consumption of “new” media, such as television, will result in decreases in the consumption of incumbent media, such as radio. Media coexistence theory,Footnote2 on the other hand, suggests audiences’ adoption and use of new media can, up to a point, be absorbed or fitted into their existing routines. This might be a result of people making more time for media use in general, or of their consuming multiple media simultaneously, for example using a smartphone while watching television. The concepts of media displacement and media coexistence appear to be opposed, with one assuming media consumption to be a zero-sum game, and the other not. That there is evidence to support both theories is likely due to their having been developed from studies that have focused on different media, markets, and time periods.

The usage of some media—such as the telegram or CB radios—has, clearly, been displaced by newer forms, leading to their almost total discontinuance (see, e.g., Newell, Genschel, and Zhang Citation2014). Other media have been subject to partial displacement. For example, although print newspapers are still with us, scholars such as De Waal and Schoenbach (Citation2010) have provided evidence that, as early as 2005, their use was being substituted by the use of web versions (486). Media displacement effects are, however, rather unpredictable, and the total discontinuance of a medium is rare. For example, although there was a 99% decline in the shipments of vinyl LPs between their peak in 1977 and 2008 (Newell, Genschel, and Zhang Citation2014), since then the format has been making a comeback. More vinyl LPs were sold in 2017 than in any year since the early 1990s (Crutchley Citation2018). Indeed, a range of studies have shown that, especially over shorter periods of time, and for particular media, media coexistence, rather than media displacement, better describes usage patterns (see, e.g., Belson Citation1961; Adoni Citation1985; Coffey and Stipp Citation1997; Dimmick Citation2003; Newell, Pilotta, and Thomas Citation2008; Greer and Ferguson Citation2014).

Much media coexistence and displacement research has sought to analyze changes in audiences’ use of media types—such as newspapers and the internet—in their entirety, rather than changes in audiences’ use of the particular media platforms through which individual brands offer their content. This is important because the case in hand—a magazine that stopped printing and went online-only—does not concern the general consumption of print and online media but rather changes in the consumption of the print and online platforms of a single media brand. Some studies have, however, looked at media displacement—or “cannibalization”, a term such studies often use—at the level of individual media brands, including magazines.

In a study covering the period 1996–2001, relatively early in the history of online journalism, Simon and Kadiyali (Citation2007) found that print circulation dropped by an average of 9% when a sample of US consumer magazines made the entire contents of their print editions available online. That print circulation was left largely intact was, the authors suggested, evidence that “digital content is not a good substitute for print media”. In a similar study, also based on data starting in 1996, Kaiser (Citation2006) examined whether, by launching websites, a sample of German women’s magazines had cannibalized their print circulation. The author found that the introduction of a website caused, on average, a 4% drop in print circulation, a decrease of less than half that found in Simon and Kadiyali’s (Citation2007) aforementioned study. However, the size of the effect may have been depressed by the fact that the magazines in question offered, at the time, little content online (Kaiser Citation2001, 7). Kaiser (Citation2006) also found that the degree of cannibalization varied with audience characteristics, such as age. The effects of audience characteristics were also explored in a study by Ellonen, Tarkiainen, and Kuivalainen (Citation2010), who found that amongst subscribers to (although not casual purchasers of) 24 consumer magazines in Finland, increases in usage of a magazine's website did not affect self-reported loyalty to its print edition. In a similar vein, although a study by Kaiser and Kongsted (Citation2012) of 67 German magazines found a “weakly significant”Footnote3 correlation between increases in traffic to a magazine’s website and decreases in its print circulation, this was driven by the effects on kiosk sales. Subscriptions were not significantly affected.

A limitation of most of these studies—Ellonen, Tarkiainen, and Kuivalainen’s (Citation2010) excluded—is that they did not perform their analyses at the level of the individual reader. It is not possible, therefore, to know with certainty how many of the magazines’ print readers were displaced to their websites, the extent to which increases in visits to magazines’ websites can be attributed to readers entirely new to the publications, or whether print readers lost to magazines were actually displaced to other websites or, indeed, to other media formats or activities altogether. As a consequence, much media displacement research may be of limited use in theorizing about what could happen when a periodical suddenly stops printing and goes online-only.

Another more fundamental limitation of media displacement and coexistence theories with respect to the case in hand stems from the fact that they were developed to describe the consequences of the introduction of new media alongside media that already existed. We are interested in the sudden withdrawal by an outlet of one of its extant media platforms. Can, then, what we know—about the effects on a periodical’s print audience of the presence and usage of its website—help us anticipate what might happen to a magazine or newspaper’s website when its print platform is withdrawn altogether? If, as the research discussed above suggests, the availability and use of a periodical’s website can cannibalize some print circulation, might a title’s website ingest some—or many—of its residual print readers when it ceases to publish in print at all? After all, if a magazine or newspaper’s website can entice some readers away from its print edition while the two media platforms coexist, then, perhaps, when the print edition is withdrawn, more readers will be enticed online—the only place where that brand’s content is now available. On the other hand, the fact that relatively few readers appear to stop consuming periodicals’ print editions as a direct result of the introduction of web versions suggests that their loyalty might be more to the medium—or at least the combination of medium and content—than to the content alone.

Uses and Gratifications

Research into the uses and gratifications of the printed medium suggests that this latter hypothesis might be stronger. As we will describe below, some of the uses made of, and gratifications received from, printed media are dependent on their physical form: the paper on which they are printed, how and when they are delivered, and the design conventions they embody. Clearly, newspapers’ and magazines’ websites and apps are not printed on paper and their design conventions usually differ considerably from those of the print editions. Furthermore, although elements of newspapers’ and magazines’ online presence may have delivery cycles akin to print—email newsletters, for example—much online content is published when ready—the “digital first” approach—or regularly over the course of the day, sometimes following the “dayparting” system developed in broadcasting (see, e.g., Beyers Citation2004).

Barnhurst and Wartella (Citation1991) analyzed 164 US college students’ “autobiographies of their newspaper experiences” and found the newspaper was used in a variety of activities—including art projects, housework, do-it-yourself projects, and “hitting the dog”—because of its particular physical form, rather than the content it carried. Its materiality was also a reason it was used to mark events—one of the students remarked that her mother kept copies, for example, from the day of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, because she felt they were “part of her history”.

Davidson, McNeill, and Ferguson (Citation2007) found that magazine readers too could have a strong physical attachment to titles, and not just to issues that were historically collectible. “Many participants,” they wrote, “were quick to express their inability to part with” their favourite magazines, with some “unable to bring themselves to throw out old copies. … one reader even admitted to hauling magazines from flat to flat, some of which she had had for ten years”.

In his study of the reactions of print readers to the non-delivery of a local, daily Oregonian newspaper, Clyde Bentley (Citation2001) observed that participants missed its arrival, which had become, in the words of one man, “a nightly ritual”. The ritualistic nature of print newspaper use, often tied up with its once daily delivery, has also been noted by other studies (see, e.g., Berelson Citation1949; Kimball Citation1959; Kimball Citation1963). For some respondents in Bentley’s (Citation2001) study, the newspaper’s materiality enabled what he called “interactive shared use”, for example, “exchanging sections with their partner” or “clipping stories and sending them to friends”. When asked about media alternatives, one couple said “we could watch TV, but it's not like having a paper in the hands”.

Hypothesis and Research Questions

Our review of the literature on media displacement/coexistence suggests that relatively few readers are fully displaced from magazines’ print editions to their websites, even when magazines make all their content available online. As the studies presented in the latter part of our review suggest, the reasons for this may be to do with the particular uses made of, and gratifications received from, printed media. We might hypothesize, then, that when we examine the audience effects of the NME’s withdrawal of its print edition, we should not expect a sudden surge in the reading of its online edition.

This hypothesis is supported by the very limited number of case studies—three—that have examined similar scenarios, albeit in the context of newspapers not magazines. Hollander et al. (Citation2011) studied the sudden and permanent unavailability of a newspaper’s printed edition in a city—Athens, Georgia—where it had previously been distributed. The newspaper in question—the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC)—withdrew its paper version from this market for financial reasons. A year after the withdrawal the researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 20 former print readers, asking whether they missed the print publication, whether the website was viewed as an alternative, and whether an e-reader (Kindle) version, which respondents had been provided with for at least a week, served as a substitute. The results showed that “of the 20 former … readers, 13 reported a sense of loss” and “only three said they sought the web version as a substitute” (131). Reasons for not using the newspaper’s website included perceived differences in content between it and the print version, and its “clunky” design. The Kindle version was found to be “easy to use” but “unsatisfying in its overall approach, at least compared to a broadsheet newspaper” (132), with the majority not viewing it as a viable alternative (ibid.), in part because of the manner in which it presented the news, which respondents felt lacked “prioritization” and “editorial organization” (131).

Hollander et al.’s (Citation2011) study was qualitative in nature and, while it offers useful explanations for why former print readers did not seek out the web version of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution as an alternative, its small and unrepresentative sample means that we do not know whether the behaviour of these particular print readers was typical of the AJC’s wider Athens readership. A second case study (Thurman and Myllylahti Citation2009) offers some, albeit limited,Footnote4 insights into wider reader behaviour at a newly online-only specialist financial newspaper, Finland’s Taloussanomat. The authors estimated that the total time spent with the brand fell by 75%–80% after the title switched to online-only (704). They also reported that the number of unique online visitors only increased slightly post-print, and less than at Taloussanomat’s main competitor, which had retained a print edition.

The third case study (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2018) is, at the time of writing, the only article of which we are aware that takes the audience effects of a newspaper or magazine’s switch to online-only as its primary focus. The authors analyzed changes in the time spent with, and net readership of, the British Independent newspaper—a general-interest, national, “quality” daily—after it went online-only in March 2016. The results estimate that the total time spent with The Independent by its British audience fell 81% in its first year post-print. The authors also found that The Independent’s “net [monthly] British readership did not decline in the year after it stopped printing” because the loss of print-only readers was offset by a growth in mobile-only readers. However, the growth in mobile-only readers was lower than the average for a dozen of its competitor newspaper brands, all of which retained print editions. It should be noted that, because of data limitations, The Independent’s net readership was measured for a time window (per month) much longer than the (daily) publication cycle of its print editions. We will return to this important discrepancy in our discussion.

In order to test our general hypothesis, we ask the following research questions:

RQ1: How did the attention (expressed in time spent reading) received by the NME from its British audience change after it stopped printing and went online-only?

RQ2: How did the net weekly and monthly British readership of the NME change when it stopped printing and went online-only?

Data Sources and Methods

Readership

In order to answer RQ2, data was acquired from the UK’s Publishers Audience Measurement Company (PAMCo). PAMCo is the successor to the UK’s National Readership Survey (NRS) and acts as the governing body overseeing audience measurement for the UK’s published media industry. PAMCo provides readership figures that reflect newspapers’ and magazines’ net (de-duplicated) multiplatform (print and online) audiences. The figures are produced by “fusing” data from PAMCo’s representative survey (N = 35,000) of British print readers with data from Comscore (and PAMCo’s own 5,000-strong digital panel) about online consumption. PAMCo provided data on the NME’s net weekly and monthly multiplatform readership during the 12 months before and 12 months after it went online-only. It should be noted that print readership figures based on recall-based surveys, as included in PAMCo’s methodology, may be subject to overestimation. Shepherd-Smith (Citation1999) believes that one cause—“replication”—is a particular issue with magazines as opposed to newspapers, although more so with monthlies than with weeklies such as the NME.

Time Spent

The data sources used to answer RQ1—PAMCo and Comscore—are the same as those used to answer RQ2. However, in order to find out about changes in the time spent with the NME after it went online-only, it was necessary to use different variables and combine the data in different ways. To calculate the time spent reading the NME in print in the 12 months before it went online-only, two variables were used from the PAMCo print survey: time spent reading and readership. Calculations were made that involved the number of issues the NME printed in the 12 months up to its last print edition, the average number of readers of those print editions, and the average minutes of reading time per issue, per reader. Again, it should be noted that the accuracy of self-reported data on time spent reading newspapers and magazines—as collected by PAMCo—has been called into question, for example, due to evidence that different measurement methods produce different results (Shoemaker, Breen, and Wrigley Citation1998).

Comscore's MMX Multi-Platform product was used to acquire the data on the total minutes spent by British adults with the NME online during the 12 months before and 16 months after the title quit paper and ink. Since April 2013, Comscore’s data have been used as “the source of UK industry-standard online audience measurement” (UKCOM Citationn.d.). Comscore uses a methodology that integrates data collected from a sample of panellists—over 113,000 in the UK (Comscore Citation2018a, Citation2018b)—with “server-centric census data” that is collected via the use of “tags” that publishers place on their websites and mobile apps (Comscore Citation2013, 2). Panellists’ online consumption—including time spent—is monitored by software installed on their PCs, smartphones, or tablets. Comscore does not monitor connections to the internet from public PCs (for example, in libraries), from PCs running operating systems other than Windows, from non-iOS/Android smartphones, and from non-iOS tablet computers. However, we see no reason why the users of such devices should be any more, or less, likely to consume the NME online; therefore, we do not believe such limitations are likely to have affected our results.

The NME’s mobile apps were not tagged until October 2018, meaning that data about the consumption of those apps before that month came solely from Comscore’s panels. This means that for most of our sampling window tagging data was not combined with panel data to produce “fused” data that might better reflect than panel data alone browsing from devices (such as Android tablet computers) not represented in Comscore’s panels.

Results

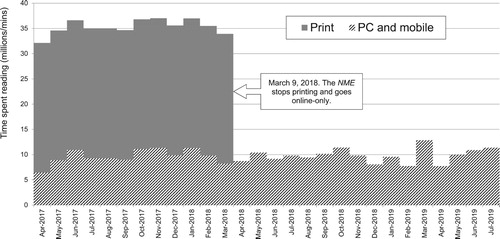

RQ1: How did the attention (expressed in time spent reading) received by the NME from its British audience change after it stopped printing and went online-only?

Figure 2. Total attention (measured by time spent reading) received by the NME from its British audience (aged 15 and over) before and after it went online-only. Sources: PAMCo and Comscore. Print reading time is a monthly average for the period April 2017–March 2018.

RQ2: How did the net weekly and monthly British readership of the NME change when it stopped printing and went online-only?

Discussion

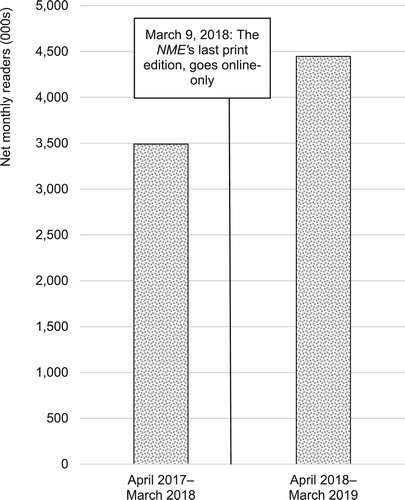

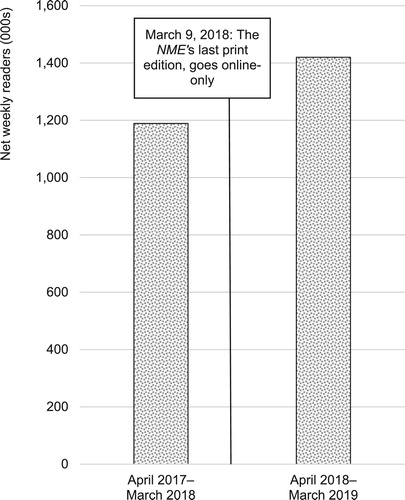

We estimate that, after the switch to online-only, the attention the NME received via PCs and mobile devices changed little. In other words, the time readers were spending with the magazine in print simply did not transfer to its online editions when the print version became unavailable. But, at the same time, the official PAMCo data show that, in the 12 months following its switch to online-only, the NME’s net monthly readership increased by 27% and its net weekly readership increased by 19%.

Figure 3. Net numbers of monthly British readers (aged 15 and over) of the NME in the 12 months up to, and the 12 months after, it stopped printing and went online-only. Source: PAMCo.

Figure 4. Net numbers of weekly British readers (aged 15 and over) of the NME in the 12 months up to, and the 12 months after, it stopped printing and went online-only. Source: PAMCo.

These two results may seem to contradict each other, but we need to keep in mind that periodicals’ audiences typically spend far less time with their online editions than with their print products (Thurman Citation2018c), so an increase in online readership will not necessarily result in an increase in time spent with a brand if time spent with print is taken out of the equation.

We must also bear in mind that the results we present here are estimates. Although the data are drawn from the best available official UK sources, the methodological decisions made by these sources may have had an impact on these estimates.

As mentioned in the Methodology section, PAMCo’s net readership figures are produced by “fusing” data from their own survey and digital panel with internet audience data from Comscore. For the fusion process, a single month’s worth of data from Comscore is used for each 12-month PAMCo reporting period. Because websites’ and apps’ internet audiences can vary month-by-month, the choice of which month of Comscore data is used in the fusion process can have an influence on PAMCo’s readership data.Footnote5 As a result, it may be that the increase PAMCo’s data report in net readership at the NME post-print is, solely or partly, due to the particular months of Comscore data that were used in the fusion process.

It is tempting to compare the results we present here with the results from a similar study into The Independent’s switch to online-only (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2018). The overall direction of the results is similar, but shifts in attention and reach differ in size. We estimate that the total time spent with the NME in the 12 months after its move to online-only was 72% lower than in the 12 months before. The Independent saw a fall of similar magnitude—81%—over the equivalent period (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2018). The NME’s net monthly readership increased by 27% and its net weekly readership increased by 19%. The Independent saw an increase in net monthly readers (of 7.7%) after it switched to online-only.

While we believe a direct comparison between the NME and The Independent is valid with respect to changes in time spent with the brands post-print, it is problematic to compare their changes in net readership. Although the data sources and methods used to calculate the readership data reported in this study are similar to those used to calculate the readership data reported by Thurman and Fletcher (Citation2018) in their study of The Independent, the frequency with which the two titles published in print differed. Although The Independent published a print edition daily, Thurman and Fletcher (Citation2018) reported its net multiplatform readership on a monthly basis. This was because the NRS PADD data available at the time only included all-important smartphone and tablet reading in its monthly net multiplatform readership results. The NME appeared weekly in print, and, in this article, we report its net readership on a monthly and weekly basis. We are able to do this because PAMCo, the successor to the UK’s NRS, has, beginning with the period January–December 2017, reported net multiplatform readership (including via smartphones and tablets) on a monthly and weekly and daily basis.

We know that periodicals’ print readers are, on average, much more loyal than visitors to their online editions. For example, half the readers of The Independent’s former print editions read them almost daily (and 35% “quite often”), while the title’s online readers visit an average of just twice a month (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2018). Likewise, 48% of the NME’s former print readers read it weekly (and 34% “quite often”) (PAMCo Citation2018b), while the title’s online readers visit an average of just 1.95 times a month (Comscore Citation2018c). An effect of this difference is that if the period for which a newspaper or magazine’s net multiplatform (print and online) readership is calculated is longer than its print publication frequency, the apparent proportion of print readers will be smaller than if the period is closer to, or the same as, its print publication frequency.Footnote6

In the case of The Independent, calculating its net readership per month, a period 30 times longer than its former (daily) print publication frequency, increased the absolute numbers of online readers to a greater extent than it did print readers because online readers visit relatively infrequently. As a result, the proportion of online readers (against print readers) appears higher than it would if net readership was calculated over a shorter period.

In the case of the NME, the same monthly net readership calculation period is only 4.33 times longer than its former (weekly) print publication frequency. Therefore, although the absolute number of online readers is increased to a greater extent than for print readers, the extent of that increase is likely to be less than at The Independent. Therefore, when we look at the change in post-print net readership at The Independent, the loss of any print readers who did not start (or continue) to read The Independent online might have a smaller impact than at the NME. Because, at the NME, net monthly readership was calculated for a period closer to the magazine’s former (weekly) print publication frequency, print readers may appear in greater proportion, making their loss, post-print, more significant.

Comparing changes in time spent with the NME and The Independent is not complicated by their differing publication frequencies. What stands out is that, in both cases, the annual attention they received via PCs and mobile devices increased little after they went online-only—by only around 1%. In other words, the time readers were spending with the periodicals in print simply did not transfer to their online editions when their print versions became unavailable.

One difference is that the NME received a lower proportion of audience attention via print than The Independent used to. We estimate that, in the 12 months before the switch, the NME’s print edition was responsible for 72% of the time spent with the brand by its British readers, with the rest (28%) coming via its online editions. The equivalent figures for The Independent were 81% from print and 19% via online (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2018). Looking at other newspapers in the UK, we see that most have also had a greater reliance than the NME on their printed editions for the attention they receive. In a study of eight UK newspapers—seven national and one regional—Thurman and Fletcher (Citation2017) estimated that the average proportion of total annual time spent received via print was 88.8% (SD = 9.23).

What, then, might provide an explanation for the fact that, compared to The Independent and some other newspapers, the NME, in its print and online era, attracted a lower proportion of reader attention from its print edition? One likely explanation is its publication interval. As a weekly publication, the NME’s print edition came out less frequently than those of daily newspapers such as The Independent, meaning there were fewer issues to read in any given week, month, or year, and, therefore, less print attention accumulated.

The amount of print content to be read could also be a factor. In the year before its switch to online-only, the NME’s print edition contained between 36Footnote7 and 40Footnote8 pages. This compares with The Independent’s typical pagination (excluding supplements)—in its last year in print—of around 64 pages on weekdaysFootnote9 and SundaysFootnote10 and 56 pages on Saturdays.Footnote11 This may be a reason why, in the 12 months before switching to online-only, The Independent’s print editions were read for an average of 37 min on weekdays and 48–50 min on Saturdays and Sundays (National Readership Survey [NRS] Citation2016c), whereas in its last year in print an average issue of the NME was read for 31 min (Publishers Audience Measurement Company [PAMCo] Citation2018a).

The behaviour of the NME’s online visitors does not appear to be an explanation for the fact that the brand received a higher proportion of audience attention via its online channels before the switch to online-only than The Independent did. The NME’s online readers have been less frequent visitors to its online editions than is the case with The Independent’s online readers, spending less time each month.Footnote12

Conclusion

Without a comprehensive theory of what we have called media platform cessation, our expectations for this study were guided by work on media displacement and the uses made of, and gratifications received from, print media; and also by studies of the withdrawal, by three newspapers, of their print editions.

Our results are in line with our general hypothesis: In the case of the NME, there was not a sudden surge in the reading of its online edition when its print edition was withdrawn. With regard to changes in time spent, our results mirror those found for The Independent. In both cases, the attention print readers were giving to the periodicals in print did not transfer online once the print editions became unavailable, resulting in sudden and substantial falls in total time spent with the brands.

Our finding on post-print time spent with the NME can be seen as part of broader changes to media attention, in part caused by technological change. Digitization has enabled the ratio of media supply to media attention to grow ten-fold between 1960 and 2005 (Neuman Citation2016), strongly suggesting that the amount of attention that each individual publisher receives is falling. More specifically, we know that UK newspapers have seen the amount of attention they receive drop by an estimated 40% since 2000 (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2017).

With regard to changes in net readership post-print, as we have discussed, it is impossible, for methodological reasons, to directly compare this case with that of The Independent. Although we believe that consumer demographics, competitor publications, the quality of their online editions, and their cover price could all affect printed periodicals’ ability to retain readers post-print, comparable data from further case studies would be required in order to assess the effects, if any, of these variables. Nonetheless, we believe that this study widens the evidence base with which we can develop a theory about changes in readership when publications move online-only.

As this case study and that of The Independent concern formerly printed periodicals, we need to be cautious about generalizing the results more widely, for example, to TV channels—such as BBC3—that have ceased linear broadcasting and gone online-only (Sweney and Martinson Citation2015). A general theory of media platform cessation is some way off. Are we, though, now closer to being able to build a more modest theory of print platform cessation? Perhaps we are. Given that The Independent and the NME differed in many ways—the periodicity and cover prices of their print publications, their reader demographics, and their content—it is remarkable that changes in time spent with the two brands post-print were so similar. We think that the temporal attention periodicals attract via their print editions is unlikely to immediately transfer to their online editions should they go online-only.

However, for our nascent theory of print platform cessation to be able to address changes in readership post-print, comparable data are required: data that estimate net multiplatform readership for time periods that correspond to newspapers’ and magazines’ print publication frequencies. Without such data, the effects of going online-only on readership are disguised and impossible to compare across dailies, weeklies, and monthlies. Fortunately, thanks to developments such as PAMCo, such data are becoming available. However, even PAMCo’s data have limitations with regard to our case. Specifically, the use of a single month’s worth of Comscore data in the creation of net multiplatform readership figures that span a full 12 months. Addressing this methodological limitation would improve the accuracy of estimates of periodicals’ net multiplatform readership to the benefit of future studies, including on newspapers’ and magazines’ moves to online-only.

To return to the case in hand, the NME, like other magazines and newspapers, went online-only for financial reasons. On those terms, the strategy apparently bore fruit (Clarke Citation2018), as it did for The Independent (Thurman Citation2018b). Undoubtedly, more periodicals will follow suit. In many countries, falls in print circulation continue, resulting in reductions in print advertising income, which have not been compensated for by growth from digital advertising. With the costs of newsprint rising, going online-only can reduce distribution costs hugely and return titles to profitability. However, as this case study has demonstrated, while a post-print existence may be less costly, it is, at least initially, more constrained, with much of the attention that was formerly enjoyed simply stripped away.

Directions for Future Research

This study suggests a number of directions for further research. There is a clear need for additional case studies on periodicals that have made the move to online-only. Such studies will help publishers in their strategic decision-making and provide a broader evidence base so that a theory of print platform cessation can be developed. The metrics that we have focused on—net readership and time spent—were chosen because they apply to periodicals’ print and online audiences unlike, for example, print circulation or unique online browsers, which apply to one medium only. Net readership and time spent also have the advantage that they are available from—or can be calculated with data provided by—many of the organizationsFootnote13 across the world that are responsible for the measurement of publishers’ audiences. However, future studies should pay careful attention to the methodological challenges of estimating post-print changes in net readership. These include possible measurement errors resulting from the fusion of print and online audience data and also discrepancies that may exist between the period for which readership is estimated and the frequency with which a newspaper or magazine published in print.

Although readership has—traditionally—been of crucial importance to publishers whose business models rely on advertising, it is becoming less important for some as they re-orientate towards subscription or donation models (see, e.g., Waterson Citation2019). It may be that, for such publishers, the effects of going online-only on net readership are of secondary importance. Rather, they may be more interested in research that analyses how any move to online-only affects their subscription base. Post-print changes in time spent by a brand’s entire audience may also be of marginal interest to publishers. Again, they may be more interested in research that analyses this aspect of behaviour in their subscribers or donors, or, indeed, other aspects of subscriber or donor behaviour given there is some evidence that time spent may not accurately indicate readers’ interest in, or engagement with, a publication (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2019).

This study focused on the NME’s British audience, the only audience segment for which net readership data was available. Future studies on periodicals’ moves to online-only might encompass not just their national audiences but also their international audiences, especially for publications, such as the NME, that are published in a language spoken widely around the world and that cover topics, such as music, with wide international appeal. There are, however, significant challenges in expanding the focus in this way. Print readership surveys are usually only conducted nationally, and although online audience data for many countries is available from companies such as Comscore, it is expensive to access. The data held by publishers on their own online audiences is an alternative source but may be difficult to acquire, given its commercial sensitivity.

Perhaps the most important question this study raises is “what happens to the time readers were spending with a publication in print after that publication goes online-only?” The data we present here clearly shows that they are not spending that time with the online version, but it is unclear whether they are turning to other print publications, or other online sources, or completely forgoing the type of information they once consumed in print. If people are turning to broadly similar sources, then this may be of only minor interest to scholars. Furthermore, whether and how people access music news may be of limited social consequence. But if the post-print behaviour witnessed at the NME applies to print news generally and the withdrawal of printed publications ultimately leads to a large reduction in the amount of news consumed, then the consequences for society could be profound.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Although Windows Magazine went online-only in 1999, citing readers’ changing information needs as the reason, it was not until around 2006 that magazines began to quit print in any number. Titles that have made the switch include Redbook, Shutterbug, Teen Vogue, The Village Voice, Penthouse, Computerworld, PC Magazine, Accountancy Age, The Dandy, and the Press Gazette.

2 Closely related to the concept of media saturation, as discussed by Newell, Pilotta, and Thomas (Citation2008).

3 “On average, a 1% increase in companion website traffic is associated with a weakly significant decrease in total print circulation by 0.15%” (Kaiser and Kongsted Citation2012).

4 Journalists rather than the audience were the focus of the study, and the authors did not look at changes in net (de-duplicated) print and online readership before and after the move to online-only.

5 PAMCo’s readership data on the NME for the 12 months before it went online-only used Comscore data from February 2018. Looking at the Comscore data across all those 12 months shows that the number of Total Unique Visitors/Viewers for the NME in February 2018 was 6% more than the average for that period. PAMCo’s readership data on the NME for the 12 months after it went online-only used Comscore data from March 2019. Looking at the Comscore data across all those 12 months shows that the number of Total Unique Visitors/Viewers for the NME in March 2019 was 35% more than the average for that period.

6 This phenomenon can be demonstrated with reference to the following example. On a daily basis UK daily newspapers reach more readers via their print editions than via any single digital platform (smartphones, tablets, or PCs), but on a weekly basis they reach more readers via smartphones than via print (Thurman Citation2018a).

7 For example, the March 2, 2018 edition.

8 For example, the December 1, 2017 and February 2, 2018 editions.

9 For example, the Wednesday December 2, 2015, Tuesday February 2, 2016, and Wednesday March 2, 2016 editions.

10 For example, the Sunday December 6, 2015, Sunday February 7, 2016, and Sunday March 6, 2016 editions.

11 For example, the Saturday December 5, 2015, Saturday February 6, 2016, and Saturday March 5, 2016 editions.

12 In the 12 months before switching to online-only the NME’s online visitors spent an average of 3.39 min a month with the brand online and made an average of 1.95 visits per month (Comscore Citation2018c). The equivalent figures for The Independent in the seven months before it went online-only were 5.20 min and 2.50 visits (Comscore Citation2016).

13 A comprehensive and annually updated list of such organizations in Europe is available here: https://www.emro.org/easi.html.

References

- Adoni, H. 1985. “Media Interchangeability and Coexistence: Trends and Changes in Production, Distribution and Consumption Patterns of the Print Media in the Television era.” Libri 35 (3): 202–217. doi: 10.1515/libr.1985.35.3.202

- Barnhurst, K., and E. Wartella. 1991. “Newspapers and Citizenship: Young Adults’ Subjective Experience of Newspapers.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 8 (2): 195–209. doi: 10.1080/15295039109366791

- Belson, W. A. 1961. “The Effects of Television on the Reading and the Buying of Newspapers and Magazines.” Public Opinion Quarterly 25 (3): 366–381. doi: 10.1086/267033

- Bentley, C. 2001. “No Newspaper is No Fun–Even Five Decades Later.” Newspaper Research Journal 22 (4): 2–15. doi: 10.1177/073953290102200402

- Berelson, B. 1949. “What “Missing the Newspaper” Means.” In Communications Research 1948–1949, edited by P. F. Lazarsfeld, and F. N. Stanton, 111–129. New York, NY: Harper.

- Beyers, H. 2004. “Dayparting Online: Living up to its Potential?” International Journal on Media Management 6 (1–2): 67–73. doi: 10.1080/14241277.2004.9669383

- Chester, T. 2011. “NME.COM 1996–2011: The Inside Story.” October 12. https://www.nme.com.

- Clarke, C. 2018. “How the NME Found its Highest-ever Readership and a New Lease of Life after Print.” The Drum, November 9. https://www.thedrum.com.

- Coffey, S., and H. Stipp. 1997. “The Interactions Between Computer and Television Usage.” Journal of Advertising Research 37 (2): 61–67.

- Comscore. 2013. “Comscore Media Metrix Description of Methodology.” http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2014/03/comScore-Media-Metrix-Description-of-Methodology.pdf.

- Comscore. 2016. Comscore MMX Multi-Platform, Total Audience, From September 2015 to March 2016, UK.

- Comscore. 2018a. “Methodology Video Metrix Multi-platform.” UKOM. https://ukom.uk.net/uploads/files/UKOM_VMX_MP_methodology.pdf.

- Comscore. 2018b. “Methodology Mobile Metrix.” UKOM. https://ukom.uk.net/uploads/files/UKOM_MoMX_methodology.pdf.

- Comscore. 2018c. Comscore MMX Multi-Platform, age 15-55+, From April 2017 to March 2018, UK.

- Crutchley, R. 2018. “A Vinyl Stocktake.” BPI, April 18. https://www.bpi.co.uk.

- Davidson, L., L. McNeill, and S. Ferguson. 2007. “Magazine Communities: Brand Community Formation in Magazine Consumption.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 27 (5–6): 208–220. doi: 10.1108/01443330710757249

- De Waal, E., and K. Schoenbach. 2010. “News Sites’ Position in the Mediascape: Uses, Evaluations and Media Displacement Effects Over Time.” New Media & Society 12 (3): 477–496. doi: 10.1177/1461444809341859

- Dimmick, J. W. 2003. Media Competition and Coexistence: The Theory of the Niche. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ellonen, H.-K., A. Tarkiainen, and O. Kuivalainen. 2010. “The Effect of Magazine web Site Usage on Print Magazine Loyalty.” International Journal on Media Management 12 (1): 21–37. doi: 10.1080/14241270903502994

- Greer, C. F., and D. A. Ferguson. 2014. “Tablet Computers and Traditional Television (TV) Viewing” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 21 (2): 244–256. doi: 10.1177/1354856514541928

- Groot Kormelink, T., and I. Costera Meijer. 2019. “A User Perspective on Time Spent: Temporal Experiences of Everyday News Use.” Journalism Studies. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1639538.

- Hollander, B. A., D. M. Krugman, T. Reichert, and J. A. Avant. 2011. “The E-reader as Replacement for the Print Newspaper.” Publishing Research Quarterly 27 (2): 126–134. doi: 10.1007/s12109-011-9205-8

- Kaiser, U. 2001. “The Effects of Website Provision on the Demand for German Women’s Magazines.” ZEW Discussion Paper No. 01–69, Mannheim.

- Kaiser, U. 2006. “Magazines and Their Companion Websites: Competing Outlet Channels?” Review of Marketing Science 4 (1). doi: 10.2202/1546-5616.1046

- Kaiser, U., and H. C. Kongsted. 2012. “Magazine “Companion Websites” and the Demand for Newsstand Sales and Subscriptions.” Journal of Media Economics 25 (4): 184–197. doi: 10.1080/08997764.2012.729545

- Kimball, P. 1959. “People Without Papers.” Public Opinion Quarterly 23 (3): 389–398. doi: 10.1086/266891

- Kimball, P. 1963. “New York Readers in a Newspaper Shutdown.” Columbia Journalism Review 2 (3): 47–56.

- Mayhew, F., and A. Kakar. 2018. “NME Faced ‘Ongoing Losses’ Prior to Print Closure with Staff Facing threat of Redundancy.” Press Gazette, March 8. https://www.pressgazette.co.uk.

- Napoli, P. M. 2011. Audience Evolution. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Neuman, W. R. 2016. The Digital Difference: Media Technology and the Theory of Communication Effects. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Newell, J., U. Genschel, and N. Zhang. 2014. “Media Discontinuance: Modeling the Diffusion “S” Curve to Declines in Media use.” Journal of Media Business Studies 11 (4): 27–50. doi: 10.1080/16522354.2014.11073587

- Newell, J., J. J. Pilotta, and J. C. Thomas. 2008. “Mass Media Displacement and Saturation.” International Journal on Media Management 10 (4): 131–138. doi: 10.1080/14241270802426600

- Nielsen, R. K. 2016. “The Business of News.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by T. Witschge, C. W. Anderson, D. Domingo, and A. Hermida, 51–67. London: SAGE.

- NRS. 2016c. Source of Copy and Time Spent Reading, April 2015 – March 2016 [Excel file downloaded from NRS website. Subscription only].

- PAMCo. 2018a. Time Spent Reading (Print), April 2017 – March 2018 [Excel file. Subscription only]. http://subscribers.pamco.co.uk/.

- PAMCo. 2018b. Print Reading Frequency PAMCo 2 2018 (Apr’17 – Mar’18) [Excel file. Subscription only]. http://subscribers.pamco.co.uk/.

- Shepherd-Smith, N. 1999. “The Ideal Readership Survey.” Paper presented at the Worldwide Readership Research Symposium, Florence, Italy. https://www.pdrf.net.

- Sherwin, A. 2016. NME Readership Soars Past 1960s Beatles Peak Six Months after Going Free. The Independent, February 11. https://www.independent.co.uk.

- Shoemaker, P. J., M. J. Breen, and B. J. Wrigley. 1998. “Measure for Measure: Comparing Methodologies for Determining Newspaper Exposure.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Simon, D. H., and V. Kadiyali. 2007. “The Effect of a Magazine’s Free Digital Content on its Print Circulation: Cannibalization or Complementarity?” Information Economics and Policy 19 (3–4): 344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.infoecopol.2007.06.001

- Snapes, L. 2018. “Its Soul was Lost Somewhere”: Inside the Demise of NME. The Guardian, March 14. https://www.theguardian.com.

- Sweney, M. 2015. “NME to Go Free with Larger Circulation.” The Guardian, July 6. https://www.theguardian.com.

- Sweney, M. 2018. “NME to Close Print Edition after 66 Years.” The Guardian, March 7. https://www.theguardian.com.

- Sweney, M., and J. Martinson. 2015. “BBC3 Set to Go Online Only as Trust Backs Plans to Scrap TV Channel.” The Guardian, June 30. https://www.theguardian.com.

- Thurman, N. 2018a. “Print Tops Tablets for Platform-devoted Newspaper Audiences [blog post].” April 19. http://neilthurman.com.

- Thurman, N. 2018b. “With Presses Silenced, a Newspaper is Sidelined [blog post].” September 25. http://neilthurman.com.

- Thurman, N. 2018c. “Newspaper Consumption in the Mobile Age.” Journalism Studies 19 (10): 1409–1429. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1279028

- Thurman, N., and R. Fletcher. 2017. “Has Digital Distribution Rejuvenated Readership?.” Journalism Studies 20 (4): 542–562. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1397532

- Thurman, N., and R. Fletcher. 2018. “Are Newspapers Heading Toward Post-Print Obscurity?.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 1003–1017. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2018.1504625

- Thurman, N., and M. Myllylahti. 2009. “Taking the Paper out of News: A Case Study of Taloussanomat, Europe’s First Online-Only Newspaper.” Journalism Studies 10 (5): 691–708. doi: 10.1080/14616700902812959

- Turvill, W. 2015. “First Free NME Claims Highest Advertising Revenue in 15 Years.” Press Gazette, September 17. https://www.pressgazette.co.uk.

- UKCOM. n.d. “Comscore MMX Multi-platform.” UKOM. Accessed January 3, 2019. https://ukom.uk.net/comscore-mmx-multi-platform.php.

- Waterson, J. 2019. “Guardian Breaks Even Helped by Success of Supporter Strategy.” The Guardian, May 1. https://www.theguardian.com.