ABSTRACT

The paper at hand presents a comparative study on news use in relation to media content as posted to Facebook by a series of established and hyperpartisan media outlets during the 2017 Norwegian national election campaign. Specifically, we are interested in determining what types of news emanating from what types of news outlets that result in comparably higher levels of news use—defined as levels of likes, shares and comments—on Facebook. Results indicated that with a few exceptions, established, legacy media dominate the most engaging news stories during the election campaign, while results for hyperpartisan media outlets suggests rather limited influence. Nevertheless, the hyperpartisan media outlets succeeded in making themselves visible on the platform under scrutiny, driving attention to issues such as immigration during the election campaign.

Introduction

News media play important roles in modern democracies—perhaps especially during elections. Indeed, concepts such as agenda-setting and gatekeeping have been employed and honed for decades (e.g., McCombs and Shaw Citation1972; Shoemaker and Vos Citation2009), crafting the basis for our common understanding of the societal roles of journalism and journalistic practice. While the bulk of these theoretical underpinnings stem from the pre-digital era, these and other time-tested conceptualizations are of essential interest also in the multi-channel, thoroughly digitized media environments of today—with at least one amendment. Specifically, while we should not overestimate their precise influence, the role of the audience member has arguably shifted since the advent and continued implementation of the Internet within the news media sector. Viewing audience members as “news users” (e.g., Picone Citation2016), the present study engages with the issue of activities undertaken by such users in relation to media content posted on what is currently one of the most important platforms for media outlets—Facebook. Providing empirical data of news use practices as performed during the 2017 Norwegian elections, the study at hand provides useful insights from a media system characterized by fairly high levels of trust in news media and willingness to pay for news (Newman et al. Citation2018) and high degrees of voting attendance (SSB Citation2017), but at the same time an increasing use of so-called hyperpartisan news sites.

Besides detailing Facebook news usage during a period of supposed heightened political attention as described above, the current work also seeks to investigate another relatively novel tendency brought on or at least augmented by the possibilities of the digital era. Indeed, the Internet and social media have introduced new opportunities for would-be publishers who lacked the funding, the “know-how” or the education to engage professionally with journalistic tasks, sometimes in tandem with journalists working within what we can refer to as established media (e.g., Gillmor Citation2004). For our current purposes, we understand so-called established, legacy or mainstream media as those outlets that adhere to the profession’s ethical rules and, in the Norwegian context, are members of the Association of Norwegian Editors.

While the term “alternative media” often invokes journalistic content influenced by left-wing, anti-establishment ideology (e.g., Atton Citation2002; Couldry and Curran Citation2003), more recent developments have seen attention in this regard shifting to what could be considered as alternative, right-wing media outlets characterized by “ways of reporting radically different from those of the mainstream” (Atton Citation2003, 267). Indeed, just as the roles of media outlets such as Breitbart and Info Wars enjoyed comparably large amounts of attention during the 2016 US presidential election, so have similar right-wing hyperpartisan media outlets sprung into action in other parts of the world. However, as scholarship into these matters has focused primarily on the US context (e.g., Fletcher et al. Citation2018), more research is needed that details the degree to which hyperpartisan news outlets and their legacy media counterparts succeed in gaining user attention in social media such as Facebook.

With the above in mind, the paper at hand presents a comparative study on news use in relation to media content as posted to Facebook by a series of established and what we refer to here as hyperpartisan, right-wing media outlets. Specifically, we are interested in determining what types of news emanating from what types of news outlets that result in comparably higher levels of news use—defined as levels of reactions, shares and comments—on Facebook. Such a focus will allow for needed insights into the growth of alternative, right-wing media in comparison to their established counterparts in a non-US context. Given the important role of audience engagement for contemporary journalism as published on digital platforms such as social media (e.g., Hanusch and Tandoc Citation2017), the paper at hand provides useful insights into the ways in which audience engagement is fashioned during a period of heightened societal activity. Indeed, as elections have been shown to increase news engagement such as the types studied here (e.g., Trilling, Tolochko, and Burscher Citation2017), studying the spread of hyperpartisan content in relation the ways in which news content from mainstream media outlets spread appears as especially suitable.

As issues of “fake news” are sometimes used to describe those competing with established media for audience attention (e.g., Tandoc, Lim, and Ling Citation2017), issues of news engagement and the spreading of news on Facebook are becoming increasingly urgent to pinpoint and clarify—especially as While our current efforts are not necessarily engaging in debates seeking to define terminology like the aforementioned “fake news” variety, the work presented here engages empirically with a series of Facebook presences often suggested as “spinning” or indeed framing news to fit a specific—in this case, right-wing—agenda. In so doing, the study presented here provides important insights into current trends in news engagement (as suggested by Chadwick, Vaccari, and O’Loughlin Citation2018).

Literature Review

Hyperpartisan News Media

As alluded to previously, media environments have changed fundamentally with the increasing proliferation of digital, social and mobile media (Vowe and Henn Citation2016), the interplay of different media logics (Chadwick Citation2013) and the challenge of novel business models for traditional news media companies (Newman et al. Citation2018). While so-called traditional or legacy media have exercised their gatekeeping roles by selecting and framing information to be presented as news for several decades (e.g., Shoemaker and Vos Citation2009), digital media in general and social media in particular have challenged this established power structure by lowering the bar to self-publish and to enter into the fray of news provision (Bruns Citation2003; Kalsnes Citation2016). Those who have taken such steps have been defined as yielding “media power that challenges, at least implicitly, actual concentration of media power, whatever form those media concentration may take in different locations” (Couldry and Curran Citation2003, 7).

While the fruits of such digital efforts have often been understood as alternative media, the term at hand is not intrinsically associated with the Internet. Rather, it has for a long time been connotated with the left-wing activism undertaken as part of the social movements that were established in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Haller and Holt Citation2019). Alternative media has also been defined as the production of small scale media that are linked to the realities of social movements (but not exclusively), and that are defined by collective practices of participatory communication within a given group (Downing Citation2001; Atton Citation2002). Other terms have also been used, such as radical media (Downing Citation2001) or citizen media (Rodriguez Citation2001). While emanating from a left-wing ideological standpoint, this terminology has increasingly been used to describe new online media sites championing issues and framings from the opposite side of the ideological spectrum (e.g., Fletcher et al. Citation2018). Indeed, Haller and Holt argue that a common definition of “alternative media” is still missing (Haller and Holt Citation2019) as alternative media is not only defined as an alternative in terms of content—but also concerning production process, media criticism, professional ethos and distribution (Holtz-Bacha Citation2015) and, as discussed here, with regards to their respective ideological outsets. Additionally, alternative media have challenged the existing practices and ethical norms of legacy media (Figenschou and Ihlebæk Citation2018).

With regards to the study at hand, we take the recent developments and tendencies outlined above into account and follow the terminology of Fletcher et al. (Citation2018) who employ “hyperpartisan” to described news media actors who champion a specific political agenda. As hyperpartisan media could be considered as alternative media with a clear political take or indeed frame on current events, the term provides a good fit with the types of alternative outlets succeeding in gaining public attention in the Norwegian context.

In relation to elections such as the one studied in the paper at hand, legacy media actors have been considered key in providing “the kind of information people need in order to be free and self-governing” (Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2001, 12). Even though such established news media still constitute the most important source of information about politics and current affairs in many Western countries (e.g., Mitchell et al. Citation2016; Van Aelst et al. Citation2017)—also in Norway (Veberg Citation2017)—recent studies have indeed demonstrated how changing news media consumption habits among citizens are resulting in more attention being given to non-legacy or indeed hyperpartisan media actors during election campaigns (e.g., Fletcher et al. Citation2018). Indeed, a plethora of such media have emerged in a series of contexts, often utilizing online channels and sometimes attracting enough readers to succeed in making impact on public discourse (e.g., Holt Citation2016; Haller and Holt Citation2019). As alluded to above, these hyperpartisan actors typically build their narratives on anti-system, anti-immigration and anti-elite framing techniques and rhetorical devices (e.g., Haller and Holt Citation2019). The influx of such hyperpartisan news providers has further bolstered the challenges to journalistic authority mentioned previously (e.g., Gillmor Citation2004; Siles and Boczkowski Citation2012), and such influences can be coupled with reports of decreased reliance on and an increased distrust of mainstream media. In relation to these developments, it seems reasonable to assume that the latter of these two tendencies is partially motivated by a perception among news consumers of widespread ethical violations and corruption within mainstream media (e.g., Siles and Boczkowski Citation2012; Starbird Citation2017).

While mass media represent communication from a centre to a dispersed mass, alternative media such as the hyperpartisan outlets discussed here typically specialize in narrower topics or on providing specific frames or explanations for everyday news. As such, a curious dependency can also be discerned between hyperpartisan and established news outlets (Haller and Holt Citation2019). Specifically, Karlsson and Holt (Citation2016) point out that much like the general tendency visible in journalism on the web, where more and more material is rewrites of stories and news produced by others, alternative media feed off of content from established media as it gives them timely content, increased traffic and—essentially—something to criticize. Thus, in addition to criticizing the mainstream, hyperpartisan media actors simply use the material published by their competitors but provide their own “spin” or indeed frame on the issues raised. For example, Holt (Citation2016) interviewed a series of Swedish alternative media actors, all mainly focused on offering critique towards what they perceived as an out of control immigration policy—as well as critiquing the ways that immigration issues had been presented in traditional media outlets. The ideological focus of these alternative media actors was not necessarily far-right or extremist. Instead, the views reported were rather diverse, ranging from lapsed social democrats to outspoken fascists. Common for all interviewees, though, was that they positioned themselves as self-appointed correctors of the supposed skewed view presented by traditional media—thus clearly challenging an institution which for several decades have had the power to represent reality to others (e.g., Couldry and Curran Citation2003). The suspicion against mainstream media is typically found in alternative media in other European countries as well (Aalberg et al. Citation2016). In Germany, the expression “the liar press” (“Lügenpresse”) often used by the Nazis to describe unfavourable media, has seen a revival lately (Haller and Holt Citation2019). Additionally, the growing influence of right-wing alternative media in terms of user numbers and the spread of postings by sharing can be seen as one example of an ongoing polarization and fragmentation of the political discourse in liberal democracies (Müller Citation2008).

Consumption of the news has become a performance that is not only about seeking information or entertainment. What we choose to “like” or follow is part of our identity, an indication of our social class and status, and most frequently our political persuasion (Wardle and Derakshan Citation2017). While these alternative media outlets might take bold stances, the question remains as to how well their products spread throughout their platforms of choice—more often than not, social media service like the one under scrutiny here.

News Use on Facebook

As previously mentioned, our current efforts are geared towards assessing news use practices on Facebook as undertaken in relation to content posted to the specified platform by a selection of legacy and hyperpartisan media outlets. We use the related terms “news user” and “news use” to describe the ways in which audiences are allowed to take roles of “active recipients” of news (Singer et al. Citation2011). Picone (Citation2016) suggests that these terms allow for an understanding of audiences as active in relation to news items that are already published rather than being allowed to create their own content. To a certain degree, such a change in how audiences are viewed could be considered a repercussion of platform choice, moving away from many of the ideals associated with citizen journalism (e.g., Örnebring Citation2013). Indeed, news users are allowed to be active only in the ways that are allowed for by the platform employed for news dissemination. In the case of Facebook, we can identify three main options that news users typically have access to when seeking to engage with news (e.g., Larsson Citation2015; Sormanen et al. Citation2015)—liking (or reacting), commenting and sharing. While the specific relationships between these three modes of engagement and the ways in which content gains traction on Facebook is in an almost constant flux, the specific nature of the changes to the importance of each mode for viral purposes remains largely unknown outside of Facebook itself. Nevertheless, gauging the degrees to which these engagements are employed is of importance if we wish to understand how novel actors—such as the hyperpartisan outlets studied here—are able to make an impact in relation to their more established competitors.

First, liking a specific post made by a news provider has been described by Hille and Bakker (Citation2013, 666) as “a ‘light’ version of participation”. While this particular function has evolved from its original inception of a “thumbs-up” icon to a plethora of reactions readily available for the news user to showcase in relation to a specific post, the relative ease with which the liking/reacting buttons are used is visible in other studies targeting the same platform (e.g., Larsson Citation2018a), but also in scholarship tracing similar feedback options as they were provided on platforms predating Facebook (e.g., Larsson Citation2011).

Second, Facebook features the opportunity for commenting in relation to posts, supposedly allowing “users to express their personal opinions” (Chung Citation2008, 666). Reminiscent of the comment fields typically available on the web sites often operated by news providers outside of Facebook, Hille and Bakker (Citation2014) suggest that news users are more likely to engage by means of commenting outside of Facebook. Indeed, while comments made in relation to Facebook posts will be made visible on the platform in some way, shape or form, such activity as undertaken outside of the platform under scrutiny are perceived as allowing for higher degrees of anonymity—“comments on websites are certainly ‘more anonymous’ than comments on Facebook” (Hille and Bakker Citation2014, 570). In comparison to the comparably low threshold to be overcome to partake in liking, we expect news user to engage by means of commenting to a comparably smaller degree.

Third, while the inner workings of Facebook algorithms are not publicly known, the practice of sharing is often pointed to as especially important in order to boost the visibility of provided posts (e.g., Nahon and Hemsley Citation2013). Much like for commenting, the sharing of news items appear to be a somewhat complicated affair for the end users. Presenting findings from a survey regarding news consumption on social media, Hermida et al. (Citation2012, 5) found that 64% of respondents “valued being able to easily share content with others”. However, Meijer and Kormelink (Citation2015, 10) report on survey data from the Netherlands, indicating that their respondents “hardly share news” and that the hesitance to do so could in part stem from an unwillingness to attract visibility.

Other studies have suggested that content characterized by controversial or emotional topics lead to higher degrees of sharing, such as immigration (e.g., Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2018; Kümpel, Karnowski, and Keyling Citation2015), and clearly, the practice of sharing news is arguably a complex one. As such, while sharing might be important for the platforms themselves, we again might expect it to be a rather diminutively used feature.

As Facebook becomes an increasingly important platform for news distribution, traditional and alternative media actors alike are scrambling to adapt their services to fit with the affordances made available by digital intermediaries such as the studied platform—a process that is the source of some frustration among media actors (e.g., Kleis Nielsen and Ganter Citation2017). Of specific relevance to our current endeavours is the premise that media actors increasingly need to provide content that succeeds in gaining engagement or indeed “attention and amplification” (Zhang et al. Citation2017) on Facebook—by means of reactions, comments and shares as described above. As previous research has shown that news content engaged with to comparably higher degrees tend to be highly emotional (Kümpel, Karnowski, and Keyling Citation2015; Larsson Citation2018b, Citation2018c), concerns regarding the “shareability” of news items might yield influence over editorial concerns when media actors plan their respective Facebook presences.

As previous research has mainly focused on engagement patterns in relation to what we refer to here as traditional or legacy media, the study at hand provides a comparative take on these issues, detailing engagement patterns across legacy as well as hyperpartisan media actors.

The Norwegian Case

As previously mentioned, the study presented here details news user engagement with legacy and hyperpartisan media in Norway during the 2017 national election. Given its clear difference from the often-studied US context (Fletcher et al. Citation2018), studying issues of online news engagement in relation to legacy and hyperpartisan media in the Norwegian context should provide useful insights regarding the spread and indeed success rate of such comparably novel media actors. Like many other countries, Norway has also seen the rise of hyperpartisan news sites in the last few years (Newman et al. Citation2018, 92). For instance, two of the outlets studied here, Document.no and rights.no, are characterized by championing tough stances on issues like immigration and Islam, sometimes succeeding to reach beyond their specific audiences and into the legacy media headlines.

Nevertheless, Norway is characterized as a more consensus-oriented society with less polarization both in the political and media system, compared to i.e., the United Kingdom and the United States, as clearly stated in Reuters Digital News Report (Newman et al. Citation2019). The Norwegian media system belongs to the democratic corporatist model as defined by Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004) , and is as such characterized by a “historical coexistence of commercial media and media tied to organized social and political groups, and by a relatively active but legally limited role of the state” (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004, 11). The system features weak degrees of political parallelism, a strongly developed mass circulation press, advanced journalistic professionalism and an active welfare state with interventions in the media sector (Strömbäck and Aalberg Citation2008, 93). Within such a context, one might expect new hyperpartisan media sites to struggle to higher degrees than in the countries characterized otherwise. But even though the partisan media sites in Norway reach a significant number of people, they are less trusted than mainstream media (Newman et al. Citation2018, 92). On the other hand, immigration as an issue has been amplified in the last Norwegian elections, and it was deemed the most important issue by voters in 2017, ahead of economy and education (SSB Citation2017). Thus, one could expect immigration-related stories from hyperpartisan sites to gain increased traction on social media.

Method

Data Collection

The media outlets studied were based on the selection process undertaken for a previous work undertaken by the authors (Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2018). To be precise, four legacy media news organizations were selected—the broadsheet Aftenposten, the public service broadcaster NRK, the commercial broadcaster TV2 and the tabloid newspaper VG. The four legacy sites are the four largest new sites and broadcasters in Norway. In order to facilitate our comparative efforts as outlined above, the mainstream outlets were combined with three hyperpartisan news providers—Document.no, Human Rights Service and Nattnytt. The first two of these providers were deemed as suitable for study given their popularity and the degree to which they had been covered by their legacy media competitors (Torvik and Åm Citation2017; Newman et al. Citation2018; Larsson Citation2019). Document.no describes itself as a “leading online website for independent and agenda-setting news, political analysis and thought-provoking commentaries”. The site was initially established as a blog in 2003, and has a weekly readership of 13% of readers on the political right (Moe and Sakariassen Citation2018), the website consists mainly of news, commentary and op-ed articles, and readers are invited to comment (Figenschou and Ihlebæk Citation2018). Human Rights Service is among the most-read alternative media sites in Norway, with 14% of weekly readers on the political right (Moe and Sakariassen Citation2018). It describes itself as a think tank and alternative news site established in 2001 to improve integration and promote universal democratic rights (Figenschou and Ihlebæk Citation2018). We also included the now defunct Nattnytt hyperpartisan outlet, which succeeded in gaining media attention during the studied election but which since then appears to have seized their activities. Nattnytt was an Islam and immigration critical website at the time of data collection with unknown owner or publisher.

Data regarding the most engaging new stories (reactions, comments and shares per news story by the studied outlets), not only related to politics, but all types of topics, were collected during the election campaign with the assistance of Storyboard. Focusing the time period leading up to the Norwegian national elections on 11 September 2017, data collection was focused on the short election campaign (Aardal Citation2011), i.e., the month leading up to the election. Thus, data regarding news use was collected starting 11 August and terminating 12 September.

Storyboard is a “social media analytics tool for online publishers, helping journalists, editors and media analysts to get the full picture of what stories are being shared right now” (Storyboard Citation2018). In essence, Storyboard collects data from social media services via RSS in combination with assessing the “share” buttons for such services that are often found embedded on the web pages of newspaper websites. While this gives us the data needed to assess differences with regards to news use across legacy and hyperpartisan media, it should be noted that news use performed without using the buttons as described above (for example, the pasting of the URL of an article onto Facebook) is not included in the data presented here. Thus, while the total share number of the articles studied are likely to be higher than what is indicated in the following, we nevertheless argue that the approach taken provides useful insights into news-sharing practices.

Data Analysis

Agenda-setting research has for many years demonstrated that the issues that dominate the agenda of the news media tend to correspond with the issues on voters’ agenda (McCombs and Shaw Citation1972; Iyengar and Kinder Citation1987). Voters in Norway, similar to many other western countries with multiparty political systems, are less faithful toward one specific party and decide late during the election campaign which party to vote for (Aardal and Bergh Citation2015). Thus, the issues that dominate the agenda of the news media, and correspondingly, the agenda of the voters, can influence the election results (Karlsen Citation2015). However, differing from traditional agenda-setting studies, this study instead examines which news stories from the studied outlets create the most activity, through social media from news users and potential voters, thus potentially raising visibility in the newsfeed of Facebook users.

Employing content analysis (e.g., Neuendorf Citation2002), the material was coded utilizing topics derived from previous, similar studies (e.g., Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2018; Sjøvaag, Stavelin, and Moe Citation2015), and the titles are translated into English from the original Norwegian. Specifically, the following codes were applied: crime, entertainment, election (pertaining to the competitive aspect rather than to specific issues), family, finance, foreign, health, immigration, politics (pertaining to specific issues rather than to the competitive aspect as in the “election” code), religion, social issues, sports, technology, weather as well as an “other” category. The two authors coded the whole material simultaneously, working together in real-time with the dataset described above. Any initial disagreements emerging during the coding process were resolved by discussion until an agreement could be reached. Given our focus on gauging the degree to which hyperpartisan media outlets succeeded in gaining traction during the studied election, the coding process was not applied to a previously decided number of news items as gathered from Storyboard. Rather, we took a more pragmatic approach, looking into the top news items from each outlet with regards to reactions, comments and shares for the whole time periode, 11 August–12 September. Thus, the number of news items analysed will differ for each of these categories of news use. Indeed, as “reacting” to Facebook posts takes place on a whole other scale than for instance sharing, the described approach was deemed suitable since it allows us to clearly assess the influence of hyperpartisan media outlets within the most engaged with news items while leaving our selection criteria flexible enough to capture the activity yielded in relation to outlets beyond the immediate top.

Results

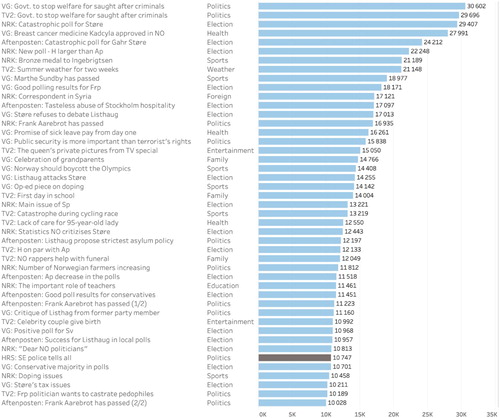

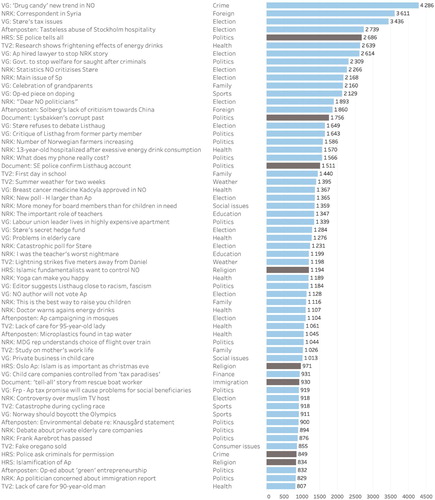

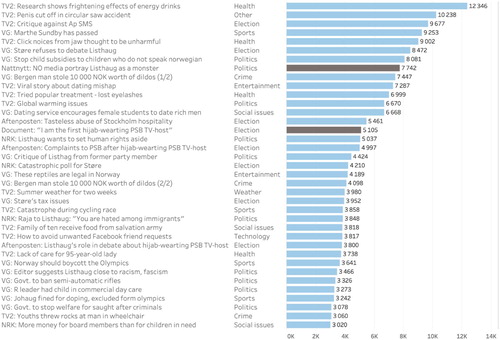

The top news items with regards to reactions, comments and shares received are presented in –. So as to facilitate easy identification of hyperpartisan media outlets, the bars depicting the amount of news use undertaken to news items emanating from such sites are featured in darker shades, while the bars corresponding to news items from established, legacy media are characterized with a lighter shade. Furthermore, the categorization of each news item is provided in relation to each corresponding bar.

First, the overall picture of our findings shows that, with a few exceptions, established, legacy media dominate the most engaging news stories during the election campaign, while, results for hyperpartisan media outlets suggests rather limited influence. For more specific results, we find that news items most reacted to, the categorization scheme provided somewhat mixed results regarding topics, but with a clear tendency towards political issues and towards news items dealing with the election itself. This latter category largely falls in line with the “horse-race” frame of election reporting often found in established media during Scandinavian elections (e.g., Strömbäck and Aalberg Citation2008)—a frame that, at least according to the results presented in , succeeds in generating reactions. Of interest is also the finding that the bulk of the news items focusing on the election largely point to pre-election polls bringing about disappointing results for the social democratic Labour party (abbreviation: Ap), while the right-wing populist Progress Party (abbreviation: Frp) are reported as doing quite well. To some extent, the placement of these news items in the very top certainly has to do with the general popularity of the horse-race frame of reporting among potential voters (Iyengar, Norpoth, and Hahn Citation2004), but could also have to do with the comparably higher levels of popularity that Frp has previously enjoyed on the platform under study here (e.g., Kalsnes, Citation2016). Additionally, the stories most reacted to concern a tougher stance against crime and immigration, topics typically associated with the Frp.

Finally for reactions, we see one dark bar in —a piece from the hyperpartisan outlet Human Rights Services featuring a “tell-all” interview with a Swedish police officer discussing issues of immigration. Thus, at least for reactions, the results presented here suggest rather limited influence for hyperpartisan media outlets.

Second, for sharing, as can be seen among the top news items identified in , the focus on issues pertaining to the election rather than political issues is tangible here in addition to the similarly structured results shown in . While election news are popular, the news detailed here with regards to sharing appear to not be as focused on polls as was the case with reactions. While we cannot make any steadfast claims as to this difference, the decreased focus on polls for the share data shown here could have to do with the aforementioned need identified by users to manage their visibility on Facebook. Specifically, while the news identified here as highly shared—such as problems emanating from tax issues of Ap leader Jonas Gahr Støre—might be easier for users to share as they evoke political scandals (Allern and Pollack Citation2012) rather than the somewhat technical style of journalism often found in relation to “horse-race”-style reports on polls. Further research into the motivations or drivers of news use will hopefully be able to assess this suggested explanation.

As for the influence of hyperpartisan content, the presence of eight dark shaded bars in suggests that such content is relatively more popular in relation to shares than to reactions. While only a few news stories emanating from these types of outlets succeeded in making it to the top in this regard, this result nevertheless suggests a normalization of these outlets that apparently enjoyed the sharing of their news items to comparably high degrees—comparable to their established legacy media counterparts. Of course, our data does not allow us to say who specifically are sharing these news items—and how large their Facebook networks are. But findings in previous research have pointed out since news sharing is not particularly common among general users of social media, those users who actually share news on these platforms tend to have a strong political interest, typically follow politicians on social media and appear as opinion leaders in their own respective social networks (Karlsen Citation2015). Nevertheless, the results presented in clearly shows the influence of hyperpartisan news media on Facebook during the 2017 Norwegian elections.

Finally, for comments, suggests somewhat differing results when it comes to the most commented news items when compared to the most reacted upon and shares. While the figure certainly features news relating to political issues and to the election, we also see a certain amount of “clickbait” type news items—featuring health risks in relation to energy drinks, penile injuries and thieves specializing in the stealing of sex toys. These stories, largely reported in a somewhat whimsical fashion thus yield plenty of comments. A closer look at the corresponding Facebook pages for each story suggests that these are largely not comments that engage with the news item per se—rather, the comment functionality is used to “tag” other users in order to make them aware of the news piece. As such, it appears that Facebook users have adapted the commenting functionality into sharing the news—but only with the user tagged in the comment, rather than sharing the news item on a profile page for all Facebook friends to see. For hyperpartisan news outlets, they are not as clearly represented here as for the most shared news items.

Discussion

Through detailing news use on Facebook during the 2017 Norwegian national elections, we have shown that political stories are among the most used across the categories employed. The findings also indicate what could be referred to as a somewhat limited influence of hyperpartisan outlets on the platform under study. In this final section of the study, we address what we consider to be our three main findings.

First, election periods are periods of heightened political attention, which is clearly visible in the material at hand as political news stories succeded in creating the most engagement among news users—in particular with regards to reactions. This finding differs from previous, similar studies where the time frame is longer (Kalsnes and Larsson Citation2018), and where political stories did not succeed in reaching the levels of engagement among news users depicted here. As shown in the Figures presented previously, the stories driving the most engagement among users are negative news stories about the Labour party. The Labour party experienced an almost historic low voter turnout in the 2017 election, a result that is reflected in the high engagement in relation horse-race themed articles about bad polling results for the party. Similarly, popular articles also featured the tax avoidance scandal associated with the Labour party leader Jonas Gahr Støre. These stories were among the most reacted and shared stories during the last month leading up to the election.

We might consider what repercussions these results could have for election reporting. Newsrooms will usually invest in numerous polls during election season, and when the corresponding social media metrics (such as those presented here) suggest that such contents appear to resonate well with news users, it is easy to see how the commercial side of the media industries might come into play—even though such prioritizations could be expected to be detrimental to the ability of voters to inform themselves about the election (Strömbäck and Aalberg Citation2008). By publishing numerous horse-race articles, newsrooms could thus be seen as performing a balancing act between securing clicks and informing the news users. Confirming previous studies (e.g., Karlsen and Aalberg Citation2015), our study finds that legacy media are still dominating during election campaigns, here measured in terms of reader engagement, but increasingly, the hyperpartisan newcomers are trying, with limited success, to challenge the traditional media outlets. The outcome of such challenges on the practices and prioritizations of mainstream or legacy media outlet professionals remains to be seen. As previous research has shown how audience engagement such as the news use patterns studied here has yielded influence of newsroom prioritizations (e.g., Lee, Lewis, and Powers Citation2012; Tandoc Citation2014; Vu Citation2014; Welbers et al. Citation2016), future studies might find it useful to gauge the degree to which the themes, styles and rhetoric of the stories offered by hyperpartisan news outlets also become salient among mainstream media. This is not to suggest that the latter type of outlets would become hyperpartisan overnight. Rather, we view these result in the light of how previous external influences—tabloidization for instance—has amended the ways in which news are presented (Larsson Citation2019).

Second, even though the hyperpartisan news outlets studied here cannot be said to compete with their legacy media counterparts in terms of total traffic (Torvik and Åm Citation2017), the results presented here are nevertheless indicative of their ability to gain visibility during the studied election—mainly through shares on Facebook. Indeed, the level of shares yielded by hyperpartisan news sites are measured at such levels that they are, in relation to certain stories at least, outperforming stories emanating from legacy media. As discussed in the literature review section of the paper at hand, sharing can be said to have a higher threshold for use than reactions. Indeed, while reactions are indeed more common, the perhaps surprisingly high numbers of shares found for hyperpartisan news stories could be seen as indicative of a small, but very active audience inclined to share items from right-wing media sites during election campaigns. The small size of the audience (5% or less of the media consumers) visit these alternative, partisan sites weekly (Moe and Sakariassen Citation2018) and appear to take on comparably active roles as redistributors of hyperpartisan content as made visible here. It should also be noted that the hyperpartisan sites have taken a tough stance on the issue of immigration and Islam, and even though their overall size in likely smaller then legacy media sites (the hyperpartisan sites are not measured by the official media site ranking, Kantar Media), they are “causing public debates that extend beyond their audiences and into the general headlines” (Newman et al. Citation2018, 92). While ideology has proven to be a strong indicator of news sharing (Guess, Nagler, and Tucker Citation2019), strong political interest for immigration issues can be an explanation for the willingness to articles from the hyperpartisan sites. It indicates a normalization of these sites on social media, driven by what could be a strong political—most likely dissenting—interest. At the same time, the results presented here could also be due to coordinated efforts to gain attention involving actual users as well as automated ones—“bots”. As this study has examined news sharing during the election campaign, future studies could examine how engagement related to content from hyperpartisan news sites looks like in a non-election period. Such an approach might help addressing some of the issues raised by the work at hand. While this study does not address and compare traffic number for legacy media and hyperpartisan media because they are not available for the hyperpartisan sites, other studies could take that into account in future efforts.

Third, our study identifies that a different kind of sharing is taking place on Facebook, going beyond the specific functionality. By tagging friends’ names in the comment section of news stories, both from legacy and hyperpartisan news sites, users make their friends aware of articles they should read. We can refer to this practice as personal sharing. Sharing news stories openly in the newsfeed is declining in many countries, including Norway (Newman et al. Citation2018), and tagging people could be seen as a more subtle and less visible type of sharing compared to the default sharing function afforded by Facebook. This personal type of sharing could suit younger news users who are less inclined to use the ordinary share function on Facebook (Meijer and Kormelink Citation2015). Nevertheless, the type of sharing detected here is miniscule compared to the two other types of engagements Facebook affords for, reactions and comments. Future studies should look into news user sharing habits and the degree to which users engage through personal sharing—as well as what these and possibly other emerging news user practices mean for those media professionals who seek to engage the visitors of their social media presences.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on the earlier version of the article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aalberg, T., F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, and C. De Vreese. 2016. Populist Political Communication in Europe. Oxford: Routledge.

- Aardal, Bernt. 2011. Det politiske landskapet: En studie av Stortingsvalget 2009. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Aardal, Bernt, and Johannes Bergh. 2015. “Systemskifte – fra rødgrønt til blåblått.” In Valg og velgere: En studie av stortingsvalget 2013, edited by Bernt Aardal and Johannes Berg, 11–33. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Allern, Sigurd, and Ester Pollack. 2012. Scandalous: The Mediated Construction of Political Scandals in Four Nordic Countries. Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Atton, Chris. 2002. Alternative Media. London: Sage.

- Atton, Chris. 2003. “What is ‘Alternative’ Journalism?” Journalism 4 (3): 267–272. doi:10.1177/14648849030043001.

- Bruns, Axel. 2003. “Gatewatching, Not Gatekeeping: Collaborative Online News.” Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy 107 (1): 31–44. doi:10.1177/1329878(0310700106 doi: 10.1177/1329878X0310700106

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power, Oxford Studies in Digital Politics. London: Oxford University Press.

- Chadwick, Andrew, Cristian Vaccari, and Ben O’Loughlin. 2018. “Do Tabloids Poison the Well of Social Media? Explaining Democratically Dysfunctional News Sharing.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444818769689.

- Chung, Deborah Soun. 2008. “Interactive Features of Online Newspapers: Identifying Patterns and Predicting Use of Engaged Readers.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (3): 658–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00414.x

- Couldry, Nick, and James Curran. 2003. Contesting Media Power: Alternative Media in a Networked World. Critical Media Studies. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Downing, John. 2001. Radical Media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Figenschou, T. U., and K. A. Ihlebæk. 2018. “Challenging Journalistic Authority.” Journalism Studies, 1–17. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1500868.

- Fletcher, Richard, Alessio Cornia, Lucas Graves, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. Measuring the Reach of “Fake News” and Online Disinformation in Europe. Fact Sheets. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Gillmor, Dan. 2004. We the Media: Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly.

- Guess, A., J. Nagler, and J. Tucker. 2019. “Less Than You Think: Prevalence and Predictors of Fake News Dissemination on Facebook.” Science Advances 5 (1): eaau4586. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau4586.

- Haller, A., and K. Holt. 2019. “Paradoxical Populism: How PEGIDA Relates to Mainstream and Alternative Media.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (12): 1665–1680. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2018.1449882.

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanusch, Folker, and Edson C. Tandoc Jr. 2017. “Comments, Analytics, and Social Media: The Impact of Audience Feedback on Journalists’ Market Orientation.” Journalism. doi:10.1177/1464884917720305.

- Hermida, Alfred, Fred Fletcher, Darryl Korell, and Donna Logan. 2012. “Share, Like, Recommend.” Journalism Studies 13 (5-6): 815–824. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2012.664430.

- Hille, Sanne, and Piet Bakker. 2013. “I Like News. Searching for the ‘Holy Grail’ of Social Media: The Use of Facebook by Dutch News Media and Their Audiences.” European Journal of Communication 28 (6): 663–680. doi:10.1177/0267323113497435.

- Hille, Sanne, and Piet Bakker. 2014. “Engaging the Social News User.” Journalism Practice 8 (5): 563–572. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.899758.

- Holt, Kristoffer. 2016. “‘Alternativmedier’: En Intervjustudie om Mediekritik och Mediemisstro.” [‘Alternative Media’: An Interview Study About Media Criticism and Media Cynicism.] In Migrationen i Mediarna [Migration in the Media], edited by Lars Truedson, 113–149. Stockholm: Institutet för mediestudier.

- Holtz-Bacha, Christina. 2015. “Alternative Presse.” In Mediengeschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, edited by J. Wilke, 330–349. Köln: Böhlau.

- Iyengar, Shanto, and Donald R. Kinder. 1987. News That Matters: Television and American Opinion. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Helmut Norpoth, and Kyu S. Hahn. 2004. “Consumer Demand for Election News: The Horserace Sells.” Journal of Politics 66 (1): 157–175. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2508.2004.00146.x.

- Kalsnes, Bente. 2016. “The Power of Likes: Social Media Logic and Political Communication.” Doctoral diss. Retrieved from DUO https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/53278.

- Kalsnes, Bente, and Anders Olof Larsson. 2018. “Understanding News Sharing Across Social Media.” Journalism Studies 19 (11): 1669–1688. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2017.1297686.

- Karlsen, Rune. 2015. “Followers are Opinion Leaders: The Role of People in the Flow of Political Communication on and Beyond Social Networking Sites.” European Journal of Communication 30: 301–318. doi: 10.1177/0267323115577305

- Karlsen, Rune, and Torill Aalberg. 2015. “Selektiv eksponering for medievalgkampen.” In Valg og velgere: En studie av stortingsvalget 2013, edited by Bernt Aardal and Johannes Berg, 119–133. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Karlsson, Michael, and Kristoffer Holt. 2016. “Journalism on the Web.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by Jon Nussbaum. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kleis Nielsen, Rasmus, and Sarah Anne Ganter. 2017. “Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations Between Publishers and Platforms.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444817701318.

- Kovach, Bill, and Tom Rosenstiel. 2001. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

- Kümpel, Anna Sophie, Veronika Karnowski, and Till Keyling. 2015. “News Sharing in Social Media: A Review of Current Research on News Sharing Users, Content, and Networks.” Social Media + Society 1 (2), doi:10.1177/2056305115610141.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2011. “Interactive to Me - Interactive to You? A Study of Use and Appreciation of Interactivity on Swedish Newspaper Websites.” New Media & Society 13 (7): 1180–1197. doi:10.1177/1461444811401254.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2015. “Comparing to Prepare: Suggesting Ways to Study Social Media Today–and Tomorrow.” Social Media + Society 1 (1). doi:10.1177/2056305115578680.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2018a. “The News User on Social Media.” Journalism Studies 19 (15): 2225–2242. doi:10.1080/1461670x.2017.1332957.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2018b. “I Shared the News Today, Oh Boy.” Journalism Studies 19 (1): 43–61. doi:10.1080/1461670x.2016.1154797.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2018c. “Diversifying Likes.” Journalism Practice 12 (3): 326–343. doi:10.1080/17512786.2017.1285244.

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2019. “News Use as Amplification: Norwegian National, Regional, and Hyperpartisan Media on Facebook.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. doi:10.1177/1077699019831439.

- Lee, Angela M., Seth C. Lewis, and Matthew Powers. 2012. “Audience Clicks and News Placement.” Communication Research 41 (4): 505–530. doi:10.1177/0093650212467031.

- McCombs, Maxwell E., and Donald L. Shaw. 1972. “The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media.” Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2): 176–187. doi: 10.1086/267990

- Meijer, Irene Costera, and Tim Groot Kormelink. 2015. “Checking, Sharing, Clicking and Linking.” Digital Journalism 3 (5): 664–679. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.937149.

- Mitchell, Amy, Jeffery Gottfried, Michael Barthel, and Elisa Shearer. 2016. The Modern News Consumer. New York, NY: Pew Research Center.

- Moe, Hallvard, and Hilde Sakariassen. 2018. Reuters Digital News Report Norge 2018. Bergen: University of Bergen.

- Müller, D. 2008. “Lunatic Fringe Goes Mainstream? Keine Gatekeeping-Macht für Niemand, Dafür Hate Speech für Alle–zum Islamhasser-Blog Politically Incorrect.” Navigationen. Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften 8 (2): 109–126.

- Nahon, Karine, and Jeff Hemsley. 2013. Going Viral. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Neuendorf, Kimberly A. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook. London: Sage.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2019. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/inline-files/DNR_2019_FINAL.pdf.

- Örnebring, Henrik. 2013. “Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better? Professional Journalists on Citizen Journalism in Six European Countries.” International Communication Gazette 75 (1): 35–53. doi:10.1177/1748048512461761.

- Picone, Ike. 2016. “Grasping the Digital News User.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 125–141. doi:10.1080/21670811.2015.1096616.

- Rodriguez, Clemenzia. 2001. Fissures in the Mediascape: An International Study of Citizens’ Media. Hampton Press Communication Series. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Shoemaker, Pamela J., and Tim P. Vos. 2009. Gatekeeping Theory. New York: Routledge.

- Siles, Ignacio, and Pablo J. Boczkowski. 2012. “Making Sense of the Newspaper Crisis: A Critical Assessment of Existing Research and an Agenda for Future Work.” New Media & Society 14 (8): 1375–1394. doi:10.1177/1461444812455148.

- Singer, Jane B., David Domingo, Ari Heinonen, Alfred Hermida, Steve Paulussen, Thorsten Quandt, Zvi Reich, and Marina Vujnovic. 2011. Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Sjøvaag, Helle, Eirik Stavelin, and Hallvard Moe. 2015. “Continuity and Change in Public Service News Online.” Journalism Studies, 1–19. doi:10.1080/1461670x.2015.1022204.

- Sormanen, Niina, Jukka Rohila, Epp Lauk, Turo Uskali, Jukka Jouhki, and Maija Penttinen. 2015. “Chances and Challenges of Computational Data Gathering and Analysis.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 55–74. doi:10.1080/21670811.2015.1096614.

- SSB (Statistics Norway). 2017. “Stortingsvalget, valgdeltakelse.” Accessed March 9. https://www.ssb.no/valg/statistikker/valgdeltakelse.

- Starbird, Kate. 2017. “Examining the Alternative Media Ecosystem Through the Production of Alternative Narratives of Mass Shooting Events on Twitter.” ICWSM.

- Storyboard. 2018. “About Storyboard.” http://storyboard.mx/about.

- Strömbäck, Jesper, and Toril Aalberg. 2008. “Election News Coverage in Democratic Corporatist Countries: A Comparative Study of Sweden and Norway.” Scandinavian Political Studies 31 (1): 91–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2008.00197.x

- Tandoc, Edson C. 2014. “Journalism is Twerking? How Web Analytics Is Changing the Process of Gatekeeping.” New Media & Society 16 (4): 559–575. doi:10.1177/1461444814530541.

- Tandoc, Edson C., Jr, Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2017. “Defining ‘Fake News’.” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 137–153. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143.

- Torvik, Yngvild Gotaas, and Ingrid Grønli Åm. 2017. “Islamkritikk på deletoppen.” Klassekampen http://www.klassekampen.no/article/20170609/ARTICLE/170609967.

- Trilling, Damian, Petro Tolochko, and Björn Burscher. 2017. “From Newsworthiness to Shareworthiness: How to Predict News Sharing Based on Article Characteristics.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (1): 38–60. doi:10.1177/1077699016654682.

- Van Aelst, Peter, Jesper Strömbäck, Toril Aalberg, Frank Esser, Claes de Vreese, Jörg Matthes, David Hopmann, et al. 2017. “Political Communication in a High-Choice Media Environment: A Challenge for Democracy?” Annals of the International Communication Association 41 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551.

- Veberg, Anders. 2017. “Dette skulle bli den store sosiale medier-valgkampen. Men studentene Jørdi og Anders foretrekker fortsatt de vanlige.” Aftenposten. https://www.aftenposten.no/kultur/i/42V9V/Dette-skulle-bli-den-store-sosiale-medier-valgkampen-Men-studentene-Jordi-og-Anders-foretrekker-fortsatt-de-vanlige.

- Vowe, Gerhard, and Philipp Henn. 2016. Political Communication in the Online World: Theoretical Approaches and Research Designs. New York: Routledge.

- Vu, Hong Tien. 2014. “The Online Audience as Gatekeeper: The Influence of Reader Metrics on News Editorial Selection.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 15 (8): 1094–1110. doi:10.1177/1464884913504259.

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakshan. 2017. “How Did the News Go ‘Fake’? When the Media Went Social.” Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/nov/10/fake-news-social-media-current-affairs-approval?CMP=twt_a-media_b-gdnmedia.

- Welbers, Kasper, Wouter van Atteveldt, Jan Kleinnijenhuis, Nel Ruigrok, and Joep Schaper. 2016. “News Selection Criteria in the Digital Age: Professional Norms Versus Online Audience Metrics.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 17 (8): 1037–1053. doi:10.1177/1464884915595474.

- Zhang, Yini, Chris Wells, Song Wang, and Karl Rohe. 2017. “Attention and Amplification in the Hybrid Media System: The Composition and Activity of Donald Trump’s Twitter Following During the 2016 Presidential Election.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444817744390.