ABSTRACT

Virtual reality (VR) and other immersive technologies introduce new opportunities for emotionally compelling narratives and user agency. Virtually mediated environments lie at the heart of immersive journalism (IJ) experiences, foregrounding a sense of presence and bridging the connection between the user and the character. Mediated environments in VR stories provide more than a setting since the user can interact with and respond to the surroundings. Drawing on the theory of spatial narrative, documentary and cinema literature and studies on media morality, this article examines the meaning of place in VR news stories and its ability to engage the user with the story. This study contributes to the discussion of creating and communicating places in journalism studies by examining spatial storytelling in immersive news stories, which are available in the NYT VR smartphone application. This paper argues that spatial storytelling eventually affects what is experienced and how it is experienced either by demonstrating the circumstances with aesthetical elements or via the selection of spaces.

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) creates the illusion of an accessible place that provides a visceral experience and opportunity for exploration. In VR journalism, spatial narrative is achieved by combining elements from video games and cinema using a “linear description” of events as seen in documentaries and the “non-linear exploration” which is common to video games (Nitsche Citation2008, 79). What makes VR journalism different is that, rather than being about “storytelling”, it is about “story-living”, as it allows the user to have an active role (Maschio Citation2017). In this paper, the idea of “spatial storytelling” refers to the ways VR news is constructed and “read” as stories that allow spatial exploration (Jenkins Citation2004).

Many definitions of place and space exist, which sometimes overlap and contradict each other. When we discuss “place”, we refer to “real” and built locations. Place has a history, a memory and a sense of community (Ryan Citation2015, 89). We understand place as being “an agentic player” (Gieryn Citation2000, 466) in VR stories, rather than merely a backdrop to action and characters (see also Usher Citation2019). VR journalism alters the way we consider or create a sense of place in news stories (Sandvik Citation2010, 139; Tricart Citation2018). In VR journalism, place serves multiple functions, from being the principal focus of a story to embodying symbolic meaning and reinforcing emotions (Ryan, Foote, and Azaryahu Citation2016; Tricart Citation2018). Space refers to the digital environment and its ability to narrate the events and cater for different forms of agency (de la Peña et al. Citation2010; Tuan Citation2011). VR simulates a sense of place by manifesting “real” places as digital spaces (Usher Citation2019).

The use of immersive and interactive storytelling is growing, and news sources (e.g., USA Today, CNN and The Guardian) are experimenting with VR journalism. The New York Times (NYT) launched VR journalism in 2015 with the publication of the documentary The Displaced (Hopkins 2017). However, the biggest challenges posed by VR are technical and include problems with producing and streaming large multimedia files. Yet, many news organisations are currently investing in 5G technology, which is expected to provide internet speed more than 20 times faster than 4G technology and will, therefore, offer the possibility to expand workflow, user experience and narrative possibilities (see Wasserman, Parr, and Kenol Citation2019; WARC Citation2019).

Discussion of the potential of immersive media to create engagement with others has become more prevalent in recent years (e.g., de la Peña et al. Citation2010; Jones Citation2017; Nash Citation2018; Sánchez Laws Citation2017). Studies on VR journalism have highlighted IJ’s ability to offer strong emotional experiences by allowing users to experience stories from a first-person perspective by inhabiting the story’s setting (de la Peña et al. Citation2010; Kool Citation2016; Maschio Citation2017; Sánchez Laws Citation2017; Sundar, Kang, and Oprean Citation2017). This paper contributes to the ongoing discussion of the connection between simulated presence and emotional engagement by examining how the user–space interaction allowed by VR news supports emotional responses. Here, we examine eight VR stories produced and/or distributed by the NYT and offer a typology of different forms of user–space interaction that support emotional engagement.

This paper focuses on the aesthetic and symbolic qualities of spatial storytelling in VR journalism, focusing on its potential to evoke emotional responses toward the characters’ suffering. In this context, by aesthetic, we mean stylistic choices in designing the space of the VR story, including lighting, mise en scène, framing and editing. David Fenner has stated that aesthetic is “a modifier of attitude” (Citation2008, 18), referring to aesthetics’ capacity to influence the process of narrative understanding and atmosphere. The symbolic qualities of narrating place constitute a deeper social, political or cultural meaning, and these symbols often require activity from the user to realise and interpret them (Whitehead Citation1985, 9).

Proximity to Place

Place is a significant component of journalism practices because it defines journalism’s cultural authority and the value of specific news events. How geographically or culturally proximate or distant the events are perceived shapes “what is included, what is excluded and why” (O’Neill and Harcup Citation2008, 162). Journalism scholars have become increasingly interested in place from the perspective of engaging experiences (e.g., Oppegaard and Rabby Citation2016; Schmitz Weiss Citation2015; Usher Citation2019). Although there is confusion about the meaning of audience engagement (it can be conceptualised from an audience-oriented perspective as attentiveness and participation or from a production-oriented perspective as journalistic techniques), engagement is often connected to close proximity to or an affective relationship with a place.

Proximity has been understood as a journalistic strategy to signal authority (Allan Citation2013; Usher Citation2019; Zelizer Citation1990). Hence, news organisations aim to amplify audiences’ experiences of space–time proximity through reporting techniques such as constructed “on the spot” reporting (Huxford Citation2007) or the use of citizens’ eyewitness imagery that accentuates an embodied sense of being at the scene of events as they happen (Ahva and Hellman Citation2015; Ahva and Pantti Citation2014; Usher Citation2019; Zelizer Citation2007). Distance, accordingly, is associated with distrust and a lack of an emotional bond (Peters Citation2011, 34). Distance not only refers to geographical or social distance but also to moral distance from characters and their situations. What Silverstone (Citation2007) defined as a “proper distance” refers to the level of proximity, which requires the user to emotionally and morally engage with the issue and the characters involved (Silverstone Citation2007).

Immersing in Narrative Spaces

As discussed previously, place refers to factual and inter-textual qualities, whereas space alludes to the digital environment in which the user is immersed. Immersion has been understood as fostering “a deep connection” between the user and the virtual environment (Calleja Citation2014, 25; Jones Citation2017; McRoberts Citation2018). This connection is enabled by VR technology as well as narrative and interactive qualities in the story-world (Cummings and Bailenson Citation2016; Slater and Wilbur Citation1997). It is this opportunity for immersion and exploring the environment that allegedly engages the user with the story and can create a sense of being there in the virtual environment (Jenkins Citation2004). We will briefly discuss presence and narrative qualities of space in immersing users in VR.

Presence refers to a sense of “being there” in the virtual environment as well as being responsive to the environment (IJsselsteijn and Giuseppe Citation2003, 5). During presence, the users become less aware of the technology, which enables the perception that they are in the space and are experiencing the events directly. The fundamental purpose of IJ is to experience space as real-life characters would, creating an illusion that the events are more unfiltered than the broadcast news (Bolter and Grusin Citation2001; Maschio Citation2017). This sense of presence is both subjective and objective: subjectivity refers to the way users feel about being in the virtual environment, and objectivity involves the way they behave similarly to real-life situations (Sirkkunen et al. Citation2016).

Nonetheless, the notion of being there is only one presence-related cognitive factor. The level of interaction and realism applied in the VR story affects the user’s perceptions and emotional engagement in IJ (Sundar, Kang, and Oprean Citation2017). Both the VR environment’s responsiveness to the user’s movements and social interaction occurring during the experience can intensify the user presence (Heeter Citation1992).

In addition to contributing to a sense of presence, space has a key role in framing an understanding of narrative meanings. In VR, space is addressed before the overall understanding of the scene is established. From a narrative perspective, orientation into a new scene follows a clear pattern: when a scene changes, the users are required to reinvent themselves in the new space and gain an understanding of where they are located (Tricart Citation2018, 94). This draws the user’s attention to spatial cues in order to make sense of the surroundings. In film studies, space is also understood to reflect a character’s psychological attributes, adjust the mood and contribute to the overall narrative by providing interpretations of the story (Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson Citation2015).

Emotional Engagement in VR

In this section, we will review the research on emotional engagement in IJ. The purpose of storytelling is to engage the audience in the narrative. Aesthetic elements create an atmosphere and convey feelings, which guide how the story is experienced (Bordwell and Thompson Citation2010). McRoberts (Citation2018) has suggested that close proximity to a news story can provide alternative ways of comprehending the issues and can offer empathic responses toward those who live outside the immediate scope of the user’s everyday life. Different narrative strategies affect whether the events are felt emotionally in close proximity and if they engage with the audience (Chouliaraki Citation2006).

The ability to utilise immersion to evoke emotions and provide a more enriched news experience has guided the discussion concerning IJ. de la Peña et al. (Citation2010) were the first to demonstrate IJ’s ability to evoke empathy in users. The literature on audience reception has shown that experiencing news from a first-person perspective increases emotional reactions (Ding, Zhou, and Fung Citation2018; Sundar, Kang, and Oprean Citation2017). This focus on emotional engagement has thus influenced the distinguishing of two levels of immersion: spatial immersion and emotional immersion (Zhang, Perkis, and Arndt Citation2017). Spatial immersion refers to engagement with a physical environment, whereas emotional immersion is characterised by engagement with characters (Ryan Citation2015). Emotional immersion is argued to provide a significantly more immersive experience than spatial immersion, which relies on perceptual qualities and a sense of being physically present (Zhang, Perkis, and Arndt Citation2017). However, this analytical categorisation of different levels of immersion is problematic because spatial qualities of the virtual environment—in particular, the experience of being in a place—creates an emotional bond.

Storytelling in VR news stories encourages the users to explore space. Narrative choices enhance user engagement especially if the events are personally relatable or involve a dramatic event (de la Peña et al. Citation2010; Ding, Zhou, and Fung Citation2018). In IJ, cinematography provides various points of interest (POIs) in the virtual environment which direct the users’ gaze to a personally interesting subject area (Tricart Citation2018). This exploration of space, together with active participation in finding information cues, has been found to positively increase the levels of user engagement with the story (Meyer Citation1995; Shin and Biocca Citation2018). Nevertheless, close proximity has the disadvantage of being too close. In a reception study, Jones (Citation2017) showed that intensified proximity to the characters caused discomfort and a sense of intrusion into the user’s personal space, especially when the characters looked directly at the users or were located less than an arm’s-length away.

The literature on audience reception has shown that experiencing news from a first-person perspective increases emotional reactions (Ding, Zhou, and Fung Citation2018; Sundar, Kang, and Oprean Citation2017). de la Peña et al. (Citation2010) found that, by assuming the character’s position in the story, the respondents felt emotional reactions, such as fear and anxiety, during the experience. The users not only had subjective reactions (i.e., like or dislike) to the story but also experienced other forms of emotional engagement, such as feelings evoked by the surroundings and empathy for the characters (Ryan Citation2015). In comparison to reporter-led stories, character-led stories provide a significantly greater “sense of atmosphere/emotion”, further supporting deep immersion (Jones Citation2017, 181). The result is that the user is more likely to respond emotionally to the story when the protagonists tell their own story and are in the focus of the narrative in IJ (Jones Citation2017).

Nonetheless, Bevan et al. (Citation2019) indicated that the first-person perspective is only one of three available points of view (POVs) or user roles in IJ along with observation and the omniscient perspective. They have argued that the first-person perspective initially employs the character’s position, whereas observation allows the user to explore the surroundings at their own pace, and the omniscient perspective accompanies the observation with voice-over (VO) narration (Bevan et al. Citation2019). Observation is characterised as passiveness since the user does not assume a role in the story, and the omniscient perspective refers to being a tourist, when the initial task of the user is to direct attention according to the VO. In fact, studies have shown that the majority of IJ projects tend to utilise two or more POVs (Bevan et al. Citation2019; de la Peña et al. Citation2010; McRoberts Citation2018; Nash Citation2018). Therefore, the shift in perspectives can confuse the user when differentiating between the emotions represented in the story and the emotional responses felt by the user (Sánchez Laws Citation2017). McRoberts (Citation2018) suggested that this blurring of motives and objectives can intensify a sense of presence and create “new levels of emotional engagement” (109–110).

A critical position in the discussion of proper distance draws attention to the logic of the media industry. Media tend to reproduce moral distance by reinforcing a sense of entertainment and pleasure, which can lead to “voyeuristic altruism” (Chouliaraki Citation2011, 366). In humanitarian studies, Kate Nash (Citation2018) was the first researcher to acknowledge the role of space in nonfiction VR. In her study on the moral potential of humanitarian VR narratives, Nash discovered that many of the works emphasised space and encouraged users to explore it, which may evoke improper distance, since the user interacts more with the space than with the characters. The purpose of VR is to simulate experiences for the audience while serving as a communicative medium. Nash (Citation2018) argued that, despite the prominence of VR technology’s ability to enhance empathy toward the characters, it may draw more attention to the user and the quality of the experience. Concerns about empathy being produced by using dramatic and/or even traumatic media content to create more perceptual, realistic experiences have initiated an ethical discussion concerning IJ (de la Peña et al. Citation2010; Kool Citation2016; Sánchez Laws Citation2017).

Method

Close reading was conducted across the dataset, focusing on the aesthetical elements and symbolical qualities. In this study, aesthetics was defined as a set of properties contributing to the overall design of the work (Klevan Citation2018, 50). The aesthetical elements include stylistic decisions and filming techniques, such as cinematography (e.g., angles, distance and framing), editing (e.g., temporality) and sound (e.g., diegetic sound, referring to sound that is part of the story-world, and non-diegetic sound that is added in post-production). Furthermore, we concentrated on analysing the characters, mise en scène and the plot. Despite VR being a three-dimensional medium, close reading offered a way to thoroughly analyse this form of audio-visual media.

The study was conducted during January and February 2018. It included eight VR stories depicting ordinary people’s encounters with various topical crisis situations, such as forced migration, the Ebola epidemic, the war in Iraq against ISIS, the civil war in Sudan and the border crisis between the US and Mexico (). Our primary interest lay in studying new forms of emotion-driven journalism, which articulated the human struggle in political or environmental crises and aimed at establishing an emotional bond between the user and the characters (Lecheler Citation2020). Therefore, light news, such as adventure or travel-themed news that could be defined as entertainment, was excluded from the study. All VR stories were filmed with a 360-degree camera or were computer designed, and they were available to view on a smartphone.

The NYT was chosen as the news organisation to study because, first, it was a pioneer in producing and distributing VR stories (the NYT VR application was introduced in 2015), and second, it provided the largest selection of VR stories in 2018. Google Cardboard VR goggles and headphones were used during the data collection. Google Cardboard is similar to the goggles sent to NYT subscribers during the application launch in 2015 and again in 2016.

Table 1. Studied VR stories.

Spatial Narrative Evoking Emotions

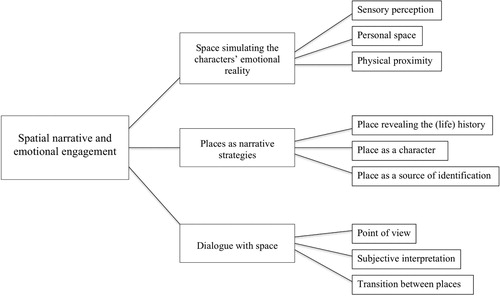

The results of the analysis were divided into three categories: (1) dialogue with space, (2) places as narrative strategies and (3) space simulating the characters’ emotional reality. The first part of the analysis focused on how the spatial narrative was demonstrated through formal elements. The second part concentrated on the journalistic choices of place and place’s ability to create emotional proximity. The third part explored the ways space directly simulates emotions through experience.

Dialogue with Space

Central to each VR news story is a constant dialogue between the user and the space—the interplay of adjusting to a new scene so that the user can understand what the location is and what is happening. The VR news stories produce a sense of place in three ways: through the transition between places, subjective interpretations and guiding the user’s experience with the POV.

Transition between places. Montages capture places that are meaningful to the characters. Traditionally, a montage refers to composing meaning between two or more shots or sequences (Rhodie Citation2006). In The Displaced, the user is introduced to several children whose lives have been affected by war and is immersed in multiple places with multiple characters. The user is taken to seemingly separate locations which together depict the average day of a 12-year-old Syrian refugee named Hana. Hana is introduced in a refugee camp, and in the following shot, she climbs into the back of a van at dawn with other children. She is seen working in a cucumber field with them, and later on she again travels in the van and returns to the refugee camp to spend time with her family. The inclusion of these places establishes Hana’s social reality and her role as a breadwinner in her family. The shots do not appear subsequently in the news story, so the transitions depict the journey as continuing. The user is immersed in other places between the shots to give insights into other children’s (Chuol and Oleg) lives.

Subjective interpretation. A spatial narrative allows the user to gain information from the environment and generate subjective interpretations. This is done by offering multiple POIs in the same space (Tricart Citation2018). In the stories, the primary POI is often the main character (or the only character) in the shot or a detail, which the VO narration points out. The stories typically immerse the user in the middle of a group of people or on a busy street. Immersing the user in the world of ordinary people hints at an invitation to be part of the community (Jacobsen, Marino, and Gutsche Citation2016). These shots involve various visceral and auditory focus points, including objects, characters and many spatial details so that the user needs to choose where to look.

The POIs also guide preferences between visual and audio information. The audio is difficult to comprehend at times because of information noise. This prompts the users to rely on visual cues and choose where to focus their attention (Bordwell Citation1985). However, the “sound perspective” generates the feeling of place when the acoustics of the scene are integrated to match the image (Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson Citation2015, 53). This enhances the sense of reality when sound is not filtered, and it also creates the notion of spatial depth.

Point of view. POV defines the user’s roles and perspectives in the narrative, whereas POI refers to freely focusing one’s attention within a space.

The works favoured a perspective that resembles the height of a grown adult. By doing so, the spatial narrative generally shapes the perspective from which the surroundings are observed (Gibson Citation1979). The screenshot shows that the users need to tilt their head slightly downward to properly see a 11-year-old Oleg standing in front of them in The Displaced, which indicates the imbalance of height (). This choice reinforces the feeling of a lived experience, but it also suggests a position of power and care (Bordwell and Thompson Citation2010; Ryan, Foote, and Azaryahu Citation2016).

The observation perspective allows the user to follow the events unfolding while freely interpreting them and the surroundings. The notion of being an observer emphasises the users’ invisible role in the story because the narrative does not directly address them (Bordwell Citation1985), as in the animated re-enactment based on a real domestic abuse case in Kiya. The user observes the events inside and outside the house: in a scene with the perpetrator along with the victim and when the victim’s sisters are on the phone with emergency services outside the house. Kiya does not provide an exclusive view to the users; instead, they are invited to witness the events, but the characters can momentarily approach the users or block their view. Thus, the observation perspective evokes perceptual realism by locating the user directly in the action without acknowledging their superior position (Bordwell Citation1985).

The news stories attempted to provide more investigative and profound accounts of the issues by providing a “tourist gaze”. Place deepens the users’ understanding of already familiar issues when it is approached from the perspective of an ordinary citizen, and the places were shown as if to provide evidence of these claims (Urry Citation2002). This was evident in 10 Shots Across the Border when the narrator introduces several locations to the user, who is there to witness the locations as if on a tour, and introduces the border fence between Mexico and the US: “This fence was built in 2011. It bears in height from 18 to 30 feet. Agents prefer this ladder design to a solid wall because it lets them observe activity on the other side” (1:14–1:34).

Place is not necessarily viewed from only a single perspective, as VR stories can provide access to more than one character’s perspective. First-person POV traditionally allows the audience to see a character’s subjective view of events (Branigan Citation2012), but spatial narrative has the ability to accommodate opposing perspectives in a single story. In 10 Shots Across the Border, the storytelling invites the user to be on both sides of the border fence: in Mexico with the family of teenager José Antonio and in the US with a border agent. The shift in perspective is not so apparent, since the immediate setting near the fence looks similar, requiring vigilance to be noticed.

Places as Narrative Strategies

The next section focuses on the different places inhabited during the VR stories, how these places communicated the societal past and the characters’ personal histories or became the focal point of the stories.

Place as a source of identification. The works prioritised the exploration of public places over private. The public places depicted include streets, markets and classrooms, which introduce the world of the characters to the user. Public places provide a more general understanding to the user than private places do, even though private places can encourage more personal engagement with characters. Public places display the mundane life in society, which can allow the user to identify with the characters’ lives (Urry Citation2002). Although the specific locations can be strange to the users, the symbolic meaning communicated through the appearance of conventional places, such as a school or a market, forms a connection between the worlds. Recognising familiar places evokes already known stories or memories, which fulfils the interpretation and imaginative understanding of a certain place (Ryan, Foote, and Azaryahu Citation2016). Thus, strangeness is introduced through familiarity, allowing the user to engage with events that are unfamiliar.

Public places are often social gathering places where interactions amongst citizens occur. The mood in these places is generally light-hearted where children are seen playing, laughing or studying. The presence of children provides a synecdoche representing both the future and the well-being of the country, but it also emphasises the emotional appeal of the stories (Moeller Citation2002). The inclusion of social places creates a sense of unity and broadens the understanding of the community as a whole.

Private places, such as a bedroom, a living room or an office, are rarely visited in news stories, but when they were, they draw attention to the individual who lives there. A possible reason for avoiding private places is that narration aims to maintain a proper distance from characters when the sense of presence already intensifies the proximity to the character (Silverstone Citation2004). Indoor areas are visited with the protagonists, but these places are not introduced, so the user is required to interpret the environment for further information.

Public and private places affect human behaviour differently, foregrounding different sides of an individual’s personality and showing what the person values in life (Meyrowitz Citation1985). For instance, such places depict Decontee Davis in Waves of Grace as a nurturing mother figure, a grieving wife, a friend, a member of a congregation and an artist. She is given different roles in the community through her social interactions in public and private places. Her appearance in these places guides the perceptions and interpretations of her, adjusting the axis of proximity –that is, distance.

Place as a character. Place can become one of the subjects in a story. Hence, place is not only understood as a physical location, but it also provides deeper ideological meanings. Long or extremely long shots used in VR stories emphasise the environment over people (Bordwell and Thompson Citation2010). For example, the locations are emphasised in The Fight for Fallujah because the user is frequently positioned to witness the devastation of the city. The only common factor amongst the human characters in the story is the city of Fallujah: they are former residents of the city, militia fighters defending the city or journalists reporting about the city. The city is thus constructed as a victim that is being rescued from the ISIS fighters by the Iraqi militia.

The repetitive inclusion of a certain object in a scene draws attention to symbolic meaning. The presence of the border in 10 Shots Across the Border and the demilitarised zone (DMZ) between North Korea and South Korea in My Trip to the DMZ, showing in the screenshots ( and ), are present in almost every scene, illustrating the existing dichotomy and underlining the political dilemmas facing the countries. Although the place in this context aims to emphasise the political challenges, it also symbolises abstract and complex issues, which are often difficult to engage with (Willis Citation2003). The borders not only symbolise ideological differences between the countries but also influence the lives of the nations and individuals involved. These borders affect ordinary citizens by dividing families and prevent them from obtaining equal rights. Even though the story of Indefinite is based on asylum seekers’ experiences, the detention centre and the unequal procedures within are the primary focus. This becomes apparent as the user is introduced to various closed facilities in the prison-like detention centre and spends the majority of the story’s duration inside these locations.

Figure 2. 10 Shots Across the Border (NYT and Ryot Media). The border wall between Mexico and the US.

Place revealing the (life) history. Place contextualises the characters’ stories and provides additional details. These details belong to the place, as the conflict is altering or has already altered the place. A street sign, which is still intact on a wall in the city of Fallujah, functions as a reminder of what the city was before it became a battlefield. Similarly, what appear to be bullet holes in the journalists’ headquarters in We Who Remain tells about a violent attack on the local journalists. Furthermore, smudgy slogans on a wall shape the cityscape in 10 Shots Across the Border. They provide a form of self-expression, embody the writers’ highly critical accounts of the authorities and hint at the subcultures present there (Halsey and Young Citation2002).

Place can function as a flashback when the user is taken momentarily to another temporality. In We Who Remain, the user is given a brief explanation of the reasons for the conflict in the Nuba Mountains in an empty clay building reminiscent of a classroom. A video documentary is projected on a wall, and a VO narrator discusses the history of Sudan. The 3-minute, 26-second scene functions as a brief lecture, showing a map of Sudan, the Nuba Mountains and documentary clips of the history of colonialism. The documentary recording and the map form another spatial and temporal dimension because they broaden the users’ understanding of the events and introduce the history behind the political conflict. The inclusion of the map reinforces a sense of place in the minds of the users by allowing them to locate the characters, who are living in the midst of a civil war, in the global context (Ryan, Foote, and Azaryahu Citation2016).

Moreover, place has the ability to reveal a character’s personal history. When Oleg and his friends are playing on an abandoned rooftop in The Displaced, they form the primary focal point because they are nearer to the camera and have been identified in earlier scenes (Tricart Citation2018). However, the flag of the pro-Russian separatists, the Donetsk People’s Republic, can be seen in the background, as in the screenshot of The Displaced (), and symbolises Oleg’s new nationality. The hometown of Ukrainian Oleg no longer belongs to Ukraine. In addition to the horrors of war, material loss and a lack of societal routine in the city, the detail of the flag draws questions regarding his national identity and personal history. Even the title The Displaced refers to place and the fact that home is bound to physical change or, as in Oleg’s case, national identity.

Space Simulating the Characters’ Emotional Reality

In respect to the third category, spatial narrative engages viewers emotionally through personal space and physical proximity to the characters and vulnerable places. In addition, the sensory perception simulates the characters’ experiences and enhances the VO narration.

Personal space. A spatial narrative is able to control the user’s emotional reactions by limiting personal space in three ways. First, the use of light in spaces influences the mood and the way the atmosphere is experienced, reinforcing emotional responses to the changing surroundings (Nitsche Citation2008). For example, the lighting in the cells in Indefinite becomes darker each time the user is taken to another space further inside the detention centre. This creates a sense that the personal space is shrinking, reinforcing feelings of hopelessness. Second, limiting personal space can be done aesthetically when the camera is positioned in a narrow place, for instance, in the cage where ISIS keeps its prisoners in The Fight for Fallujah () and where the user can barely fit into the space. Personal space does not exist in the VR environment as it does in the physical world (Bailenson et al. Citation2001; Wilcox et al. Citation2006), which can intimidate users. Third, the sudden appearance of an object or a subject in direct sight can surprise or frighten the user when it is in close physical proximity. Thus, the user feels the need to respond to this sudden shift and adjust their position (Gibson Citation1979).

Physical proximity. Close physical proximity to places that have a tragic history or symbolic places of vulnerability reinforce emotions (Chouliaraki Citation2006). In We Who Remain, journalist Musa John recalls his time in a hospital after he was injured in an explosion. The user’s physical proximity to a graveyard or to a victim of Ebola being carried in a body bag generates feelings about the victims, and the inclusion of these places symbolising death invites the user to empathise with the victims (McRoberts Citation2018). These locations depict the loss and suffering of the characters as well as the grief of their families.

The user is occasionally positioned in physical proximity to the protagonists as if sharing the moment with them. When the character is in the scene, the shot composition is often equivalent to a medium-long shot, and the user is positioned as if sitting beside the character, creating physical proximity between the user and the character (Bordwell and Thompson Citation2010). Physical proximity is typically utilised during the characters’ vulnerable testimonials. When Decontee Davis recalls the time she contracted Ebola in Waves of Grace, she is confined in a dark bedroom with little daylight coming through a window with metal bars. She narrates her story: “ … I was afraid that if I entered the hospital, I would die” (2:54–3:08). It is no coincidence that when she talks about the most difficult time of her life, she is located in a dark room, symbolising her experiences. These moments emphasise the character’s emotions and physical experiences.

Sensory perception. The first-person perspective produces similar sensory perceptions to what the characters have experienced in the past. For instance, Indefinite aims to create an understanding of how asylum seekers are treated when they seek residence in the UK and how the brief time in a detention centre affects people. Sensory perceptions emphasise experience, particularly when the user is positioned in the hectic London Victoria Coach Station after being kept locked inside for nearly 10 min with minimal human contact. The user is immersed in stimuli, which overloads the mind but also creates a sense of being on a street in London.

Spatial narrative demonstrates and enhances emotions, which enriches the character’s VO by emphasising a sense of presence. Thus, space imitates the circumstances that were involved during the characters’ suffering and illustrates what is described in the VO narration (Nichols Citation1991). In We Who Remain, Hannan Osman Kajo, a mother from Al Azark, explains how the villagers fled to the safety of caves when airplanes approached to bomb her village. During the VO narration, the user is located in a cave where many children are hiding. Similarly, nine-year-old Chuol in The Displaced paddles a canoe in a swamp, and the user is located in the canoe with him. The camera movement follows the movement of the canoe, which creates a sense that the user is actually sitting in the canoe with him. When the characters’ VO is used to describe the events, it often creates intimacy between the characters and the user (Kozloff Citation1988, 50; Nichols Citation1991, 159). The VO narration explains how Chuol had to flee from soldiers through a crocodile-infested swamp, which automatically prompts the user to look over the side of the canoe. Thus, a sense of presence allows the user to strongly identify with the narration (Jones Citation2017). Simulations can intensify the experience by sparking feelings of anxiety or fear by suggesting that there is a potential threat lurking in the scene. This enhances engagement by evoking empathy toward the characters because the circumstances are cruel and unfair, and the subjects involved are children.

Discussion

This study explored spatial narrative and sense of place in creating emotional engagement with VR news. We aimed to provide a typology of the different levels that these user–space interactions create when evoking emotions (). We have analysed how spatial narrative functions through formal elements and the inclusion and arrangement of different places and explored the ways spatial narrative simulates the emotional experiences of the characters. We discovered differences in emotional appeal amongst 360 documentaries, illustrations and re-enactments. Re-enactments and illustrated VR stories were fully scripted, they invested in “shock effect”, and the events happened directly to the user, intensifying the emotional appeal. All the documentaries were shot on location, emphasising realism and the characters’ living environment and evoking emotions through encounter and locations.

The study however involved certain limitations, which we would like to address. It focused only on 360 videos, which allowed less interactivity than VR stories using haptic controllers. The rationale for focusing on 360 videos was the news organisations growing interest in producing them and 360 videos easy availability for the consumers. Moreover, the sampling involved a limited number of re-enactments and illustrations.

A spatial narrative connects the characters to their places, revealing unspoken insights and vividly depicting the circumstances. Even though the user’s exploration of the space supports immersion, this may compromise engagement with the character whose story is being inhabited (Nash Citation2018; Sánchez Laws Citation2017; Tricart Citation2018). However, emphasising locations over people supports the fact that places—and, more specifically, places significant to the characters—encourage exploration. Symbolic details in the environment reveal patterns of behaviour and describe the character in relation to the community (Wolfe Citation1975). The users reflect on what they see in the space against what they already know about the issue or the characters. Then, they determine whether their interpretations of the character and their natural environment conflict. Therefore, spatial narrative allows the user to extend their interpretation of a place to the character’s story. The narrative focus shifts to the characters when they reveal their emotional pasts, and space simulates their experiences to the user.

Independent exploration provides a sense of freedom, unmasking the fact that the narrative is controlled by a selection process and careful arrangement of different places to tell a story. The opportunity to freely interpret the space is considered to involve a level of moral risk and an epistemological challenge (Aitamurto Citation2019; Jones Citation2017; Nash Citation2018). Every VR experience is unique—likewise, people experience the same events differently in real life. However, spatial narrative draws attention to the characters’ circumstances by allowing the users to relive the described scenes. The illusion of diminishing the virtual environment and controlling the sensory information guide the experience. Although subjective interpretations in different spaces seem unrestricted, they are not. The specific shots are included for a reason and are arranged in a certain order to tell a story. The shots, which fall under the category of subjective interpretation, often involve multiple stimuli, creating a sense of perceptual realism. Perceptual realism adds a new layer to the experience with the careful design of visuals and audio to enhance emotional engagement (McRoberts Citation2018). Nonetheless, users cannot assume that all the information occurring simultaneously in 360 degrees and the interpretation of details and symbols require the active presence from the user. Yet, understanding of the scenes does not solely depend on subjective interpretations.

The news stories’ ability to enhance emotions is a requirement for an immersive experience. Focusing on the users’ own emotions may not be seen only as a selfish consumption of news, since “self-centered emotions” are required to achieve deep immersion because they sustain a sense of presence (Ryan Citation2015, 110). The emotions felt by the user only enhance the experience or make it more vivid. Hence, simulating the character’s “emotional reality” in the given situation evokes an emotional response and engages the user with the story (Wolfe Citation1975, 32). Subtle adjustments to the ambient space and straightforward control of the perspective bring the user in close proximity with the space imaginatively and emotionally.

This study explored how a sense of place is demonstrated in VR journalism, as its role has previously been overlooked (Usher Citation2019). Acknowledging the role and importance of spatial narrative in IJ is crucial, since it affects how news is composed, experienced and understood. As Usher (Citation2019) argued, place should be considered a fundamental element of journalism when narrating a news story. This disconnect is exemplified by the division of spatial immersion and emotional immersion and comparisons of their affectivity. Zhang, Perkis, and Arndt (Citation2017) attempted to define space in VR, but they did not consider its affectivity in terms of aesthetic or symbolic qualities. Studies on the effect of interior design have already demonstrated the ability of environment to affect mood and emotions (e.g., Anderson Citation2009; Matta, Debkumar, and Sougata Citation2012). As determined in our analysis, spatial narrative tells a story, develops it and supports the characters’ accounts. Spatial narrative primarily affects what is experienced and how by demonstrating the circumstances with aesthetical elements or selecting places in which the user is immersed. Contrary to what has been argued by Zhang, Perkis, and Arndt (Citation2017), space does not only support the experience and adapt to the users’ movement, but it also contributes to emotional engagement.

Considering that the advent of VR journalism occurred only a few years ago, it seems evident that VR has not established itself as a form of production in journalism. VR journalism has mainly been produced by the large media companies and in the Western part of the world. This opens up possibilities to research how smaller media organisations can employ immersive and interactive techniques to create a sense of place, strengthen trustworthiness and build connections between the user and the character.

To conclude, place reinforces a contextual and emotional understanding of the characters’ situation, and spatial narrative eventually controls what is experienced and how it is experienced in VR journalism.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahva, Laura, and Maria Hellman. 2015. “Citizen Eyewitness Images and Audience Engagement in Crisis Coverage.” International Communication Gazette 77 (7): 668–681.

- Ahva, Laura, and Mervi Pantti. 2014. “Proximity as a Journalistic Keyword in the Digital Era: A Study on the “Closeness” of Amateur News Images.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 322–333.

- Aitamurto, Tanja. 2019. “Normative Paradoxes in 360° Journalism: Contested Accuracy and Objectivity.” New Media & Society 21 (1): 3–19.

- Allan, Stuart. 2013. Citizen Witnessing. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Anderson, Ben. 2009. “Affective Atmospheres.” Emotion, Space and Society 2 (2): 77–81.

- Bailenson, Jeremy N., Jim Blascovich, Andrew C. Beall, and Jack M. Loomis. 2001. “Equilibrium Theory Revisited: Mutual Gaze and Personal Space in Virtual Environment.” Presence: Teleoperators& Virtual Environment 10 (6): 583–598.

- Bevan, Chris, David Phillip Green, Harry Farmer, Mandy Rose, Danae Stanton Fraser, Helen Brown, and Kristen Cater. 2019. “Behind the Curtain of the “Ultimate Empathy Machine”: On the Composition of Virtual Reality Nonfiction Experiences.” CHI 2019—Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Glasgow.

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 2001. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bordwell, David. 1985. Narration in the Fiction Film. London: Routledge.

- Bordwell, David, Janet Staiger, and Kirstin Thompson. 2015. The Classical Hollywood Cinema. London: Routledge.

- Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. 2010. Film art: An Introduction. 9th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Branigan, Edward. 2012. Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film. Berlin: Moutan Publishers.

- Calleja, Gordon. 2014. In Game: From Immersion to Corporation. Boston, MA: MIT.

- Chouliaraki, Lilie. 2006. The Spectatorship of Suffering. London: Sage.

- Chouliaraki, Lilie. 2011. “Improper Distance: Towards a Critical Account of Solidarity as Irony.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 14 (4): 363–381.

- Cummings, James J., and Jeremy N. Bailenson. 2016. “How Immersive is Enough? A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Immersive Technology on User Presence.” Media Psychology 19 (2): 272–309.

- de la Peña, Nonny, Peggy Weil, Joan Llobera, Bernhard Spanlang, Doron Friedman, Maria V. Sanchez-Vives, and Mel Slater. 2010. “Immersive Journalism: Immersive Virtual Reality for the First-Person Experience of News.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 19 (4): 291–301.

- Ding, Ni, Wen Zhou, and Anthony Y. H. Fung. 2018. “Emotional Effect of Cinema VR Compared with Traditional 2D Film.” Telematics and Informatics 35 (6): 1572–1579.

- Fenner, David E. W. 2008. Art in Context: Understanding Aesthetic Value. Athens: Swallow Press.

- Gibson, James J. 1979. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Gieryn, Thomas F. 2000. “A Space for Place in Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 463–496.

- Halsey, Mark, and Alison Young. 2002. “The Meanings of Graffiti and Municipal Administration.” The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 35 (2): 165–186.

- Heeter, Carrie. 1992. “Being There: The Subjective Experience of Presence.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 1 (2): 262–271.

- Huxford, John. 2007. “The Proximity Paradox: Live Reporting, Virtual Proximity and the Concept of Place in the News.” Journalism 8 (6): 657–674.

- IJsselsteijn, Wijnand, and Riva. Giuseppe. 2003. “Being There: the Experience of Presence in Mediated Environments.” In Being There: Concepts, Effects and Measurements of User Presence in Synthetic Environment, edited by Giuseppe Riva, Fabrizio Davide, and Wijnand Ijsselsteijn, 1–14. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Jacobsen, Susan, Jaqueline Marino, and Robert E. Gutsche. 2016. “The Digital Animation of Literary Journalism.” Journalism 17 (4): 527–546.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2004. “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” In First Person: New Media as Story, edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin, 118–130. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jones, Sarah. 2017. “Disrupting the Narrative: Immersive Journalism in Virtual Reality.” Journal of Media Practice 18 (2/3): 171–185.

- Klevan, Andrew. 2018. Aesthetic Evaluation and Film. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Kool, Hollis. 2016. “The Ethics of Immersive Journalism: A Rhetorical Analysis of News Storytelling with Virtual Reality Technology.” Intersect: The Stanford Journal of Science, Technology, and Society 9 (3): 1–11.

- Kozloff, Sarah. 1988. Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lecheler, Sophie. 2020. “The Emotional Turn in Journalism Needs to be About Audience Perceptions.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 287–291.

- Maschio, Thomas. 2017. “Storyliving: An Ethnographic Study of How Audiences Experience VR and What that Means for Journalists.” Newslab.witgoogle.com, July 28. Accessed June 20, 2019. https://newslab.withgoogle.com/assets/docs/storyliving-a-study-of-vr-in-journalism.pdf.

- Matta, ReddySwathi, Chakrabarti Debkumar, and Karmakar Sougata. 2012. “Emotion and Interior Space Design: An Ergonomic Perspective.” Work 41 (1): 1072–1078.

- McRoberts, Jamie. 2018. “Are We There Yet? Media Content and Sense of Presence in Non-Fiction Virtual Reality.” Studies in Documentary Film 12 (2): 101–118.

- Meyer, Kenneth. 1995. “Dramatic Narrative in Virtual Reality.” In Communication in the Age of Virtual Reality, edited by Frank Biocca and Mark R. Levy, 219–258. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Meyrowitz, Joshua. 1985. No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moeller, Susan D. 2002. “A Hierarchy of Innocence: The Media’s Use of Children in the Telling of International News.” Press/Politics 7 (1): 36–56.

- Nash, Kate. 2018. “Virtual Reality Witness: Exploring the Ethics of Mediated Presence.” Studies in Documentary Film 12 (2): 119–131.

- Nichols, Bill. 1991. Representing Reality. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Nitsche, Michael. 2008. Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Game Worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- O’Neill, Deirdre, and Tony Harcup. 2008. “News Values and Selectivity.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 161–174. London: Routledge.

- Oppegaard, Brett, and Michael K. Rabby. 2016. “Proximity: Revealing new Mobile Meanings of a Traditional News Concept.” Digital Journalism 4 (5): 621–638.

- Peters, John. 2011. “Witnessing.” In Media Witnessing: Testimony in the Age of Mass Communication, edited by Paul Frosh and Amit Pinchevski, 23–48. New York: Palgrave McMillian.

- Rhodie, Sam. 2006. Montage. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2015. Narrative as Virtual Reality 2: Revisiting Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Ryan, Marie-Laure, Kenneth Foote, and Maoz Azaryahu. 2016. Narrating Space/Spatializing Narrative: Where Narrative Theory and Geography Meet. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press.

- Sánchez Laws, Ana Luisa. 2017. “Can Immersive Journalism Enhance Empathy?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 213–228.

- Sandvik, Kjetil. 2010. “Crime Scenes as Augmented Reality: Models for Enhancing Places Emotionally by Means of Narratives, Fictions and Virtual Reality.” In Re-Investigating Authenticity: Tourism, Place and Emotion, edited by Britta TimmKundsen and Anne MaritWaade, 138–154. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Schmitz Weiss, Amy. 2015. “Place-Based Knowledge in the Twenty-First Century.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 116–131.

- Shin, Donghee, and Frank Biocca. 2018. “Exploring Immersive Experience in Journalism.” New Media & Society 20 (8): 2800–2823.

- Silverstone, Roger. 2004. “Regulation, Media Literacy and Media Civics.” Media, Culture & Society 26 (3): 440–449.

- Silverstone, Roger. 2007. Media and Morality: On the Rise of the Mediapolis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Sirkkunen, Esa, Heli Väätäjä, Turo Uskali, and Parisa Rezaei. 2016. “Journalism in Virtual Reality: Opportunities and Future Research Challenges.” In Academic MindTrek’16: Proceedings of the 20thInternational Academic MindTrek Conference, 297–303. New York: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

- Slater, Mel, and Sylvia Wilbur. 1997. “A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments.” Presence: Teleoperators& Virtual Environments 6 (1): 603–616.

- Sundar, Shyam S., Jin Kang, and Danielle Oprean. 2017. “Being There in the Midst of the Story: How Immersive Journalism Affects Our Perceptions and Cognitions.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 20 (11): 672–682.

- Tricart, Celine. 2018. Virtual Reality Filmmaking: Techniques & Best Practices for VR Filmmakers. New York: Routledge.

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 2011. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. 7th ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Urry, John. 2002. The Tourist Gaze. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Usher, N. 2019. “Putting ‘Place’ in the Center of Journalism Research: A Way Forward to Understand Challenges to Trust and Knowledge in News.” Journalism & Mass Communication Monographs 21 (2): 84–146.

- WARC. 2019. “National Geographic Prepares for 5G Storytelling.” WARC by Ascential, January 21. Accessed August 30, 2019. https://www.warc.com/newsandopinion/news/national_geographic_prepares_for_5g_storytelling/41566.

- Wasserman, Aharon, Serena Parr, and Joseph Kenol. 2019. “Exploring the Future of 5G and Journalism.” Times Open, April 11. Accessed August 30, 2019. https://open.nytimes.com/exploring-the-future-of-5g-and-journalism-a53f4c4b8644.

- Whitehead, Alfred North. 1985. Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Wilcox, Laurie M., Robert J. Allison, Samuel Elfassy, and Cynthia Grelik. 2006. “Personal Space in Virtual Reality.” ACM Transactions on Applied Perception (TAP) 3 (4): 412–428.

- Willis, Jim. 2003. Human Journalist: Reporters, Perspectives, and Emotions. Westport: Praeger.

- Wolfe, Tom. 1975. The New Journalism. London: Picador.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 1990. “Achieving Journalistic Authority Through Narrative.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 7 (1): 366–376.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2007. “On ‘Having Been There’: ‘Eyewitnessing’ as a Journalistic Key Word.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 24 (5): 408–428.

- Zhang, Chenyan, Andrew Perkis, and Sebastian Arndt. 2017. “Spatial Immersion Versus Emotional Immersion, Which is More Immersive?” Ninth International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX), Erfurt, Germany. IEEE.