ABSTRACT

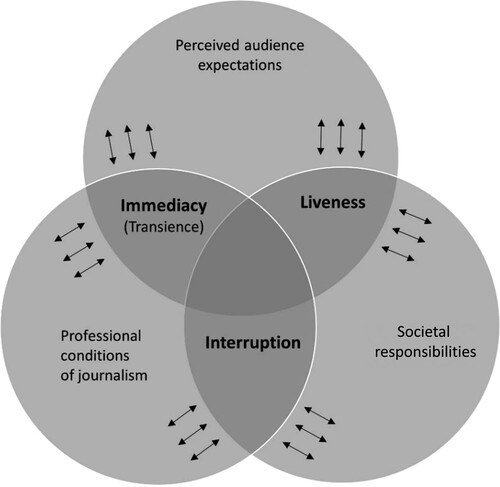

Acts of terrorist violence become repeatedly the focus of amplified attention in Western media. These acts spur hybrid media events where both news media and media users create and share information and interpretations of the event. Large news organizations play an integral role in attracting, steering and regulating attention in hybrid media events of terrorist violence. This article develops a theoretical conceptualization of the news organization as an attention apparatus. We argue that the apparatus consists of two dimensions: First, three conditions constrain the workings of the attention apparatus: perceived audience expectations, professional conditions of journalism and societal responsibilities of journalism. Secondly, there are three temporal affordances through which attention is managed: immediacy, liveness and interruption. We come to these conclusions through empirical research on newsroom practices in terrorism news production at the Finnish Broadcasting Company (Yle). Our data consist of thematic interviews (N = 33) with Yle journalists, producers and content managers as well as newsroom observations (14 days) conducted at Yle News and Current Affairs departments. The data is interpreted through a grounded theory approach. The article highlights how the temporal affordances enable reporting in hybrid media events but also clash with established conditions of news reporting.

Introduction

When an act of terrorist violence takes place, it sends ripples throughout the global media environment, creating a hybrid media event. Acts of terrorist violence receive massive attention created by various actors and media users. The contemporary media environment forms an infrastructure of resonance that conditions the direction, intensity and accumulation of the circulation of attention (Citton Citation2017, 29). Anyone with internet access can publish content connected to an event, but the possibility of any individual actor to control the circulation of attention is limited. The ability to gain and direct wide attention depends on the power relationships between the involved actors and their resources and abilities to use technological and social affordances. Those who already have visibility and followers in the global media space are privileged in terms of attention.

Among the privileged are journalistic media production organizations, such as national broadcasting companies. They have a significant role in directing and organizing attention and thus have a significant impact on the formation of a hybrid media event (Sumiala, Tikka, and Valaskivi Citation2019). Reporting a violent event, news media have a range of possible attention management techniques that generate the reach and intensity of attention. Attention is also one of the motivating forces behind acts of terrorism. This creates a complicated and mutual relationship between terrorism and news production. Journalists and other news production personnel are very aware of the set of techniques they have at their disposal for managing attention. In our interview data, they repeatedly referred to the implementation of these techniques as “the news apparatus”.

Through empirical research on practices in terrorism news production at the Finnish Broadcasting Company (Yle), this research develops a theoretical conceptualization of the news apparatus. A conceptualization of the attention apparatus highlights how the attention in hybrid media events is constructed through multiple practices and this illuminates the communicative power news organizations have in creating and managing attention. As a public broadcaster, Yle news production has a wide range of possible tools to use when covering a violent attack. Depending on the case, there are several decisions to make: which platforms to publish in, with what kind of volume, whether to interrupt regular programming, whether to send reporters to the scene and whether to produce a special news broadcast. These decisions are made in the news organization while considering factors like audience expectations, journalistic practices and norms and the possible societal implications of unnecessarily inflated coverage. Illuminating these processes through research may offer news organizations a chance to critically view their operations during hybrid media events.

Based on our empirical research conducted at Yle News and Current Affairs departments, we develop a concept of attention apparatus and use it as a heuristic tool to illuminate how certain functionalities of affordances are utilized during hybrid media events. We conceptualize the apparatus first through the external conditions that define the three conditions of attention management: perceived audience expectations, professional conditions of journalism and societal responsibilities of journalism. Second, we introduce three temporal affordances of the attention apparatus utilized in managing attention: immediacy, liveness and interruption (cf. Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018).

In the following section, we first discuss the conditions of the attention apparatus concerning the earlier literature on hybrid media events, attention, terrorism and news production. We will then explain our data and methods and move onto considering the different affordances and their use in reporting on hybrid media events of terrorist violence. In the discussion, we consider how different temporal affordances are negotiated for the appropriate scale of reporting. We conclude by addressing the ethical and practical consequences of the attention apparatus contributing to a hybrid media event of terrorist violence.

Conditions of Attention Management in a Hybrid Media Event of Terrorist Violence

Attention is often described as a scarce asset in digital media environments, but it mostly remains conceptually fuzzy. Attention has been studied in media and communication studies from micro-level conceptualizations, which concentrate on the experiences of individual users juggling the inputs of media outlets and platforms (Webster Citation2014, 7; Citton Citation2017). In the context of hybrid media events, attention can be conceptualized as both the heightened public interest to the event and the intensified production and circulation of content connected to the event. In this article, we are interested in understanding the social mechanisms that regulate attention (Campo Citation2015). In what follows, we discuss the three conditions that regulate the workings of a news organization as an attention apparatus: perceived audience expectations, professional conditions of journalism and societal responsibilities of journalism.

First, perceived audience expectations condition the functions of the news organization in several ways. Earlier television news research found that perceived audience relevance was one of the central features that determined whether a news event was going to be covered by television news (Altheide Citation1985). Boydston, Hardy, and Walgrave (Citation2014, 512) note that certain key events can elicit high levels of public attention and interest from the audience, leading to a demand for more information. News media then try to satisfy this hunger by providing more news about the same issue (ibid). Discussions on hybrid media events (e.g., Sumiala et al. Citation2018) expand, firstly, on theorizations of the hybrid media system (Chadwick Citation2013) and, secondly, on the media event theory, and consider the complexity of the contemporary hybrid media environment in directing and expanding attention. The internet and the growth of social media have increased the complexity in understanding audience relevance for journalistic media that operate as a part of an intensified attention economy (Davenport and Beck Citation2001; Chadwick Citation2013) where human attention is increasingly harvested and resold to advertizers (Wu Citation2017, 6) and the accumulation of attention is dependent on the socio-technical environment intertwining the logics of the journalist media and social media (Chadwick Citation2013). The public service media work in this same environment and partly use the attention economy logics for gaining attention and competing for audiences. Finding and reaching audiences have become more challenging for broadcasting companies because of the abundance of content available in the online environment (Hokka Citation2017, 225). Despite their ability to produce free and high-quality content (Webster Citation2014), they still have to compete with multiple online actors for audiences and even truth claims. These dynamics peak when a violent attack takes place as news organizations also compete with each other to produce immediate news and live coverage on the event.

The second condition of the attention apparatus is professional conditions of journalism defining newsroom practices and ways of making news. Altheide (Citation1985, 346) found that the TV news format provides the framework through which news is “selected, interpreted and presented”. He pointed out that events with certain features will more likely be covered than others, as they can be more easily utilized in the logic of the format. Analysing the so-called hostage drama in Iran from 1979 to 1981, he identified six characteristics that increase the possibility of a news event becoming TV news. In addition to perceived audience relevance, these characteristics included accessibility, visual quality, drama and action and encapsulation and thematic unity. Encapsulation and thematic unity refer to two things: (1) to what extent could the event be briefly summarized and stated and (2) how well it can be connected with earlier similar events or series of reports over some time. Since Altheide’s findings, the hybridization of the media environment has complicated news production practices and increased the use of various platforms into the pallet of newsrooms (see Belair-Gagnon Citation2015). The professional conditions of journalism also include the practices and routines of news production in general, such as journalistic professional norms of accuracy, impartiality, verification and balance (Belair-Gagnon Citation2015, 5) and in the routines created for unexpected events (Tuchman Citation1997).

The third condition of the attention apparatus are the societal responsibilities of journalism. The dilemma of the relationship between media attention and terrorism has been documented as recognized by journalists themselves (e.g., Rao and N’ Weerasinghe Citation2011; Abubakar Citation2019). This is understandable as public attention is the aim of terrorism (Alexander Citation1980; Chalfont Citation1980), leading into a symbiotic relationship between terrorism and journalism (Schmid and Jongman Citation1988; Wilkinson Citation1997). Media attention has been seen to increase terrorist acts of violence (Jetter Citation2017), and some suggest that restricting media attention would diminish terrorism (Scott Citation2001). Thus, journalists have to consider the societal and ethical implications of terrorism news reporting in the midst of hectic hybrid media events.

Whilst news production practices in the event of violent disruptive attacks have been previously studied, there has not yet been research on how news production utilizes social and technological affordances to manage attention in disruptive hybrid media events. Previous research has investigated how news organizations organize themselves in crisis news situations such as terrorist attacks (See Olsson Citation2010; Figenschou and Thorbjørnsrud Citation2017) and how journalists find routine ways of dealing with non-routine events (Berkowitz Citation1997; Tuchman Citation1997) but there has been little research on the operations of the news organization as a whole in these contexts. The conceptualization in this article formulates an understanding of the various conditions and affordances at play in a news organization and thus helps pinpoint the challenges of journalistic reporting in hybrid media events.

Attention Apparatus and Affordances

To simplify matters, we could say that a hybrid media event is created by attention. An occurrence itself is not an event, it is the mediated attention and meaning making process that constitutes a media event (cf. Alexander Citation2012). Hybridity in this context refers to two things: firstly, a hybrid media event is formed through the influence of human and non-human actors in the hybrid media environment. Secondly, the hybrid media event brings together features of both ceremonial (Dayan and Katz Citation1992) and disruptive (Katz and Liebes Citation2007) media events. As Witschge et al. (Citation2019, 656) write, hybridity does not mean there is no order, but rather that order is dynamic, unstable, and more fragile. This in turn may enhance the need to negotiate, fortify and express norms, such as journalistic authority and responsibility.

In addition to attention, hybrid media events can be looked at from the perspective of four other A’s: actors, affordances, affect and acceleration (Sumiala et al. Citation2018), which are also important dimensions for our discussion on the attention apparatus. The concept of affordance refers to the material and technological possibilities and constraints for the practices of managing attention. Previous research on affordances of the digital environment has focused on the possibilities of communication in social media in particular for individual users, whilst less attention has been given to affordances in traditional media settings (Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018, 39). Here, we focus on how the news organization is activated as an attention apparatus during hybrid media events through using different affordances.

Foucault describes the key elements of an apparatus (“dispositif” in the original French) in an interview from 1977 (Foucault Citation1977, 194–198). Giorgio Agamben summarizes Foucault’s thoughts on the apparatus through three points: (a) an apparatus is a heterogeneous network that includes virtually anything, linguistic and non-linguistic, under the same heading: discourses, institutions, buildings, laws, police measures, philosophical propositions and so on; (b) the apparatus always has a concrete strategic function and is always located in a power relation and (c) an apparatus appears at the intersection of power relations and relations of knowledge. Thus, the apparatus is always linked to certain limits of knowledge, which rise from it and equally conditions it (Agamben Citation2009, 2–3). Jeremy Packer describes an apparatus as a strategically organized network of discursive and nondiscursive elements brought together to address problems resulting from specific formations of knowledge (Packer Citation2010, 89). Both Agamben and Packer understand the apparatus as a way to manipulate relations for a strategic goal.

Yves Citton brings together the concepts of apparatus and attention. He discusses the role of media apparatuses in organizing human attention: “human attention seems to be massively channeled by an entanglement of media apparatuses which enthrall us” (Citton Citation2017, 29). Citton emphasizes the collective aspect of the formation of attention as well as the media infrastructures in directing that attention. Attention is structured by collective enthralments, which are inextricably architectural and magnetic. Collective enthralments here refer to certain discourses or ways of seeing. Media apparatuses generate and manage attention by circulating certain forms (rather than others) among and within us (Citton Citation2017, 31). Citton thus sees media apparatuses as vehicles for circulating understandings and regimes of attention that invite and entangle human attention. Citton’s empirical example of an attention apparatus is search engines, Google, in particular.

Villém Flusser’s thoughts on apparatus offer a useful extension for thinking about the functioning of a news organization as an apparatus. Flusser uses the camera as a starting point for a general analysis of the apparatus (Flusser Citation1984, 21). He defines an apparatus as a thing that lies in wait or preparation for something (ibid.). According to Flusser, in the post-industrial context, the intention of an apparatus is not to change the world but to change the meaning of the world. Thus, the intention of apparatuses is symbolic (Flusser Citation1984, 25). A news organization is, without a question, this type of meaning-making and meaning-changing apparatus: the entire function of the news organization is to acquire information from the world, organize it according to the principles of news conventions and practices and make it available through different platforms. News organizations are somewhat prepared to report large-scale unexpected events and have developed reporting routines through experiencing similar events (Olsson Citation2010).

The news organization is a type of assemblage, which consists of several technical equipment and technologies: the broadcasting system, computers, cameras, the internet, program archives, the editorial software, social media applications, etc. The attention apparatus is valuable because of its ability to coordinate the use of the technical equipment for organizing symbols and, through this symbolic work, manage attention. For these goals, the attention apparatus requires the human being as a player and functionary (Flusser Citation1984, 31).

Here, the concept of affordance comes into play. Affordance refers to opportunities for action rather than the properties of the environment (Sumiala et al. Citation2018). Affordances are situated on the interface of the material and technological possibilities for human agency. The notion of affordances emphasizes the non-deterministic nature of technology, which means that technology provides opportunities and constraints, but journalistic contents and decisions are made in the interplay of different considerations (Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018, 51).

We approach the attention apparatus by investigating the functions and practices at play in the news organization during a hybrid media event of terrorist violence. In our analysis, we are interested in the different affordances available in the news organization for steering and managing attention. These affordances are always being used in the news organization but are accentuated in the context of a hybrid media event connected to terrorist acts of violence. We utilize Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger’s (Citation2018, 37) concept of temporal affordances for understanding the attention apparatus and evaluating the relationship between news technologies and journalistic practices connected to attention. Their six temporal affordances are immediacy, liveness, preparation time, transience, fixation in time and extended retrievability (ibid). Whilst Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger (Citation2018) look at the way temporal affordances are manifested in the temporal characteristics of news narratives, our focus is on the material and technological possibilities and constraints through which the news organization connects to the hybrid media event and manages attention through these affordances.

Grounded Theory Approach

Grounded theory refers here to the practice of creating theory through empirical analysis. The methodological process of this study utilizes data gathered through fieldwork to identify, develop and integrate concepts (Corbin Citation2017, 301). As a part of this approach, the concepts out of which the theory was constructed were derived from collected data and theories of hybrid media events (Valaskivi and Sumiala Citation2014; Sumiala et al. Citation2018), attention (Campo Citation2015; Citton Citation2017) and terrorism news reporting (Olsson Citation2009; Archetti Citation2013; van der Meer et al. Citation2017; Steensen et al. Citation2018) to inform data collection and analysis. The article develops theory by following terrorism news reporting within the newsroom (Liège, 29.5.2018Footnote1 and Strasbourg, 12.12.2018Footnote2), as well as doing reflective interviews with journalists at Yle (Strasbourg, 12.12.2018 and ChristchurchFootnote3, 15.3.2019) and through following terrorism news reporting in the media on these cases. Observation of the newsroom informed the data collection in interviews and also contextualized their analysis.

Data and Analysis

The primary data for this article consists of semi-structured thematic interviews (N = 33) with journalists, producers and content managers as well as newsroomFootnote4 observation (14 days) conducted in the Finnish Broadcasting Company Yle. The data were gathered in Yle’s main news organization in Helsinki in May and December 2018. The observation data were collected from the news desk and three News and Current Affairs departments. Mostly the interviews included reflections made at a considerable temporal distance from the actual attacks, but the research period included actual observation of news production on the Liège and Strasbourg terror attacks in December 2018. There has been only one event determined as a terrorist attack in Finland (The Turku attack, 2017). This means that the events discussed in the data happened at a geographical distance to the news organization. The scale of reporting depends on the graveness of the terrorist attack, the identity of the perpetrator and the geographical and cultural distance, and many small attacks are only reported as regular breaking news events. Out of the cases studied here, only the Christchurch attack created a hybrid media event of global scale.

Data were gathered through a variety of methods: (1) semi-structured thematic interviews with news organization personnel, which were gathered in the field via a snowball method, (see Appendix 1). (2) observation of newsroom workflows and practices, (3) observation of terrorism news production (Strasbourg, 12.12.2018) and (4) reflective accounts from newsroom personnel on two terrorism news cases (Liège, 29.5.2018 and Strasbourg, 12.12.2018 and Christchurch, 15.3.2019). The research included discussions with professionals working in different roles in the news organization: journalists, producers, content managers, social media editors, visual editors, technical staff and chiefs of different departments. The extent of the different data coincides with that of a grounded theory approach where data sets may include interviews, observation, documents, videos, memoirs, letters and any other source deemed appropriate by the researcher (Corbin Citation2017, 301).

The interviews were coded on Atlas.ti, a qualitative analysis tool.Footnote5 The initial analysis was done through a code list based on relevant theoretical concepts on hybrid media events and terrorism news reporting, out of which one was “attention”. As the term “news apparatus” repeatedly arose in the data, it was added to the code list. To further develop an understanding of the mechanisms of the attention apparatus, the following questions were examined by close reading the data: (1) Through which affordances does the news organization manage attention in a hybrid media event? (2) What are the problematics of a newsroom as an attention apparatus in hybrid media events?

“The News Apparatus”

The analysis in this article stems from the term “news apparatus” appearing repeatedly in the interviews. Journalists used the term when speaking about activating large-scale reporting during media events. According to their words, “the news apparatus” was “started or ignited”, after which “the wheels started turning” and the “machinery worked”. These metaphorical descriptions encouraged us to further analyse how the news apparatus functions in creating and managing attention in a hybrid media event. We constructed an empirical view of what an attention apparatus means in the context of the news organization by coding references to attention in the interviews and subsequently identifying affordances for creating attention within this code.

The news apparatus is already in place before the media event, but many of its functions intensify during the reporting of the media event. One interviewee mentioned that like all professional news organizations, Yle has internal strategies for sudden news events: an internal alarm protocol alerts the producers of different departments to organize reporting on the issue. The content manager and producers then alert enough producers, reporters and other personnel to report on the event widely on different platforms (I22).Footnote6 This initial stage is described by several interviewees as the “switching on the news apparatus” or “getting the news apparatus into full speed” and aiming that “the news organization works like an oiled machine”. One interviewee noted that the news apparatus needs to be more effective and streamlined during media events, and this means that the protocol for activities must be clear (I6). Another interviewee mentioned that the apparatus must be tuned to be agile in major news events (I29).

Interviewees mentioned that in the first phase of reporting, the goal is to “pour resources” into the machine to get the apparatus in motion (I21, I24, I26). This means that journalistic routines are activated: online reporting is initiated, news agencies and social media are followed for the latest updates, established sources are contacted for studio interviews, eyewitnesses are sought for comments and insert material is procured for the live broadcast. Interviewees commented that media events are what the news organizations are “built for”, and hectic news situations are practiced every day in regular news work (I1). A shared consensus was that in these situations everyone comes together and works for a common goal (I9, I29). In this article we further investigate how the attention apparatus works in these abrupt reporting situations.

Temporal Affordances of the Attention Apparatus

In our data, we identified three temporal affordances of the attention apparatus. Out of Tenenboim-Weinblatt’s and Neiger’s six temporal affordances, two were prevalent in our data: immediacy refers to reporting near their occurrence and liveness refers to practices of reporting events simultaneously with their occurrence. Also, we identified interruption as another temporal affordance specifically connected to the broadcasting media. Interruption refers to the abrupt disruption of “normal broadcasting” and schedules. The attention apparatus has a range of scale in news reporting through managing temporal affordances. All of these affordances are connected to the possibilities offered by different technologies and capabilities to create and manage attention and are usually all used at a specific time in the beginning of the attack. Even though our empirical case is terrorism news reporting, we suggest that the functioning of the attention apparatus is similar in any breaking news situation.

In the next sections, we consider how temporal affordances (immediacy, liveness and interruption) are utilized and negotiated in the context of hybrid media events. Thereafter, we consider how combining these affordances transforms the news organization into an “attention apparatus” and finally we discuss the problematics of this apparatus in reporting within hybrid media events connected to terrorist violence.

Immediacy

Immediacy has always been a central news value: getting the news out as fast as technology will allow. However, in the context of online news, immediacy means the quest for “nowness” (Usher Citation2014, 88–89). The affordance of immediacy enables journalists to report on recent newsworthy events near their occurrence (Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018, 37). Transience supports the value of immediacy as it lowers the stakes of making mistakes (Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018, 43.). Transience was also briefly mentioned in our data, and here we consider it a supporting affordance in managing attention. Transience does not directly create attention but is integral for immediate reporting.

Yle, like most news organizations today, relies on web-first reporting. The first information about an event must be online in minutes after the first confirmatory information is received (I20, I21). The online news format is enabled by the transience affordance, which allows gradual temporal layering and constant updating of news stories with new information. Yle has switched from numerous separate stories to a moment-to-moment format for online reporting: every new development is reported in chronological order in one piece (I1, I18). The format constructs the ambiance of immediacy but also gives a gateway for the audience to connect to the event as one informant described it: “Moment-to-moment is where the audience likes to gather and follow how the event develops and keep following it.” (I1)

Yle as a news organization has consciously attempted to develop the capacity and flexibility to report immediately. Yle has, in the past, created a “fast reporting task force”, which enabled immediate live reporting of news events. This task force relied on specific reporters who were on call for sudden media events (I5). More recently, the mentality of immediate live reporting has become a mode of reporting more general to the entire Yle news organization (I5, I21, I33). This general aim of immediacy in news reporting has been verified in other researches (for example Usher Citation2014). Yle has developed the mobile broadcasting unit Nopsa (Quick) to enable fast online broadcasting in sudden media events. Nopsa requires less personnel than regular broadcasting studios. Online broadcasting can be started within 15 min of the event without negotiations with the TV channels for airtime. These organizational preparations are connected to the demand for immediate reporting and are built on the technological abilities to do so.

The pursuit of immediacy is explained by audience expectations and professional conditions of journalism. Because of the attention given to grave terrorist attacks, there is considerable pressure from the audience for Yle to be fast (I19), and to stand up to par with both national and international news media, such as CNN and BBC (I21). Yle has the best resources in broadcasting in Finland, but the online news competition is fierce (I21). Thus, the requirement for speed is fueled by the news competition and critique from within the Yle news organization but also directly from audiences, who commented online if Yle’s reporting was considerably slower than other news media. “[…]why are you stalling and messing up again’ and something like that this is easily the reaction from the audience, so the starting point has been that we have to get going faster and we have to be able to provide facts and reliable information.” (I21)

The requirement for immediate reporting thus creates external and internal pressures for the news for continuous immediacy. These goals are sometimes hard to achieve due to time differences and the lack of information from the scene as our interviewee mentioned:

It’s kind of a contradictory thing when we have these goals of how fast we have to get (reporting) going and the realism is that it depends on where the event has happened and what time of day it is happening, and the available material may be really scant. (I9)

In hybrid media events, there is heightened public attention not only in the course of events but also on the functioning of news organizations. The affordance for immediate online reporting works both sides as audiences may also react instantaneously to news pieces. Journalists may have to explain their choices of guests and interviewees or their decisions to publish or not publish certain facts (for example, the name of a terrorist) (I1, I21). The informants mentioned this affordance as most challenging in reporting hybrid media events as the newsroom has to justify their decisions immediately in the midst of hectic reporting. The immediacy of the entire hybrid media event requires the news organization to fill its’ societal role in the event.

If we don’t do a broadcast based on verified information, someone will easily fill the void. Unofficial channels, which may contain all sorts of rubbish, will most likely fill (the void) if people’s interest has awoken and it’s (an event) of that scale. So I kind of a see an important responsible role for us. (I25)

Liveness

The concept of liveness has been widely discussed in television studies for decades (e.g., Williams Citation1974; Feuer Citation1983; Caldwell Citation1995; Uricchio Citation1998; Bourdon Citation2000; Auslander Citation2008). In more recent years, the concept has been explored further in relation to “the new media” and the internet age (e.g., Couldry Citation2004; Ytreberg Citation2009; van Ess Citation2017). Van Ess (Citation2017) looks at liveness as a set of different constellations of technology, institutions and audience. In the context of the attention apparatus, liveness can be seen as the aim to be in direct connection with the media event.

Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger (Citation2018) name the liveness affordance, which enables journalists to report events simultaneously with their occurrence (Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018, 37). Liveness is an integral aspect of media events (Sumiala, Tikka, and Valaskivi Citation2019). Live television broadcasts especially may facilitate a collective experience of time and a shared sense of history in the making (Dayan and Katz Citation1992; Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018, 37). Liveness has been a major goal of the Yle main news channel TV1. This goal is achieved through longer broadcasts on an event and getting live broadcast running as fast as possible. (I33.)

The special news broadcast is one of the main formats of reporting on terrorist attacks at Yle (I1, I21). It is an institutionally created journalistic format through which attention is diverted and steered towards a collectively shared viewing experience. The special news broadcast opens up space for the news organizations to report any developments but mostly to be a participant and witness to the hybrid media (Frosh and Pinchevski Citation2009). The live broadcast is in itself a signal to the audience that something important is going on (I28). One interviewee mentioned that the format of the online news broadcast creates a “sense of urgency”, as the newsroom is shown in the background, which situates the viewer in the midst of reporting (I21).

Furthermore, the sense of community, witnessing and authenticity may be integral for audiences (cf. Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Neiger Citation2018, 37). This coincides with the Yle special news broadcast with its content being built on the presence of the news anchor and guest interviewees, who were brought in to analyse and contextualize the event (I25). The special news broadcast is a ritual (Dayan and Katz Citation1992; Couldry Citation2004) way of performing liveness. It is to say: “Even though we do not yet know, we are here”. The performance of liveness is a ritual that seems to answer to the perceived audience expectations of experiencing the event live, the professional conditions of journalism as a witness to events and also the societal requirement of the media for providing information of these events. Yle is the go-to news outlet for wide audiences in major news events (I4, I33), and it can fulfill its public service duty by performing liveness in a crisis situation.

In a way the performance of liveness compensates the first stage of reporting when there is not yet new information of the event. Through liveness the news organization doesn’t have to publish any unconfirmed facts, but they are still taking part in the formation of the hybrid media event. Liveness also enables audience members to connect to the event at different times: “Although it’s boring to repeat the same stuff over again, but the assumption is that people turn to the channel 10 minutes later and then again 5 minutes later, so they don’t all hear the same stuff 50 times”. (I28)

In addition to creating a collective viewing experience, liveness appeared in our data in the way news media aim at being on the scene: being “there” on the spot. The being “there”-ness is sometimes portrayed in the special broadcasts by showing a feed from the scene by international news agencies. In addition, Yle’s correspondent is often sent to the scene in major terrorism news cases to do live broadcasts (I14, I19, I21). Liveness in the case of disruptive media events (Katz and Liebes Citation2007) such as terrorist attacks is a more challenging goal to accomplish than in pre-planned ceremonial media events such as coronations, contests and conquests (Dayan and Katz Citation1992). The scene of the terrorist attack is often crowded by international media (I19) and blocked by the police, so there is no access for journalists (I14). There may also be a shortage of available satellite slots for live broadcasts or the local mobile network may be overloaded (I18, I19). Perhaps due to this challenge, it is essential for a news organization to perform liveness in the studio as well as at the scene. Previously, journalists’ authority has very much been based on “being there” and “telling there” (Usher Citation2020, 250), and this practice is still formidable even if audience memebers can also produce live feed from the event.

Interruption

An attack of terrorist violence interrupts the flow and routines of everyday life. In contemporary societies, this interruption is felt through the media. Even in the hybrid media environment, broadcasting media with its ritualized schedules has a special role in the routines of everyday life. Thus, in the news organization, a terrorist attack interrupts “normal broadcasting” (I31, I33). The decision to interrupt only takes place if the attack is grave enough, it is geographically (or culturally) close and it happens in the daytime when audiences are present. In other words, “global media events” are always asynchronous and usually take place at a distance.

At Yle, the interruption of normal broadcasting occurs through launching special news broadcasts concentrating specifically on the event. In practice, Yle has both technical and strategic preparedness to interrupt ongoing television broadcasting “with a press of a button” (I25, I33). However, the preparation of the facilities for interrupting regular broadcast takes time. Before interrupting ongoing programing, the news desk has to negotiate with the transmission centre that the case in question is salient enough to require interruption of normal broadcasting (I33).

The special news broadcast creates an interruption of the regular broadcasting mode and is integrally connected to liveness. A rather non-intrusive form of interruption is the screen banner, which can be displayed on any ongoing programme informing the audience that something unusual has happened (I25, I33). Yle also has a crisis layout for the main news website for extraordinary news events (I32), which can be interpreted as a form of interruption of the normal user experience. Interruption is integrally related to audience expectations and news values. The news organization must consider if the event is grave enough to interrupt the broadcasting schedule. However, interruption is less connected to professional conditions of journalism and the societal responsibilities of journalism than the affordances of immediacy and liveness. It is rather a means of creating time and space for the media event to occur through the attention apparatus.

Discussion: Using the Affordances of the Attention Apparatus for Scalability

In the previous sections, we have outlined the different temporal affordances the news organization uses in managing attention in hybrid media events. The affordances overlap in the reporting process as the attention apparatus is constantly balancing and negotiating the use of affordances (immediacy, liveness and interruption) to create and adjust the appropriate scale of reporting per each disruptive media event. Journalists are aware of the full potential of the news apparatus and use the scalability of the news organization with the newsworthiness of each event. Using the full potential of the temporal affordances is a way of amplifying attention. The wider the attention, the bigger the hybrid media event.

Terrorist attacks in the Western context contain elements of surprise, bad news, magnitude and relevance (Harcup and O’Neill Citation2001). These elements are inclined to magnify the attention given to terrorist attacks, but Yle had also taken this tendency into consideration. Our informants stated that reporting on previous terrorist attacks had affected the attention given to similar events. The string of terrorist attacks in Europe had raised the threshold of reporting massively on small-scale terrorist attacks. Our research thus confirms the descriptions of Altheide discussed above on encapsulation and thematic unity: each terrorist attack is considered in relation to earlier events and their impact. At the same time, terrorist attacks have become part of the news agenda and the news organization have created routines for covering these events (Cf. Berkowitz Citation1997).

Creating large-scale reporting takes up the resources of the news organization on many levels. This includes controlling the social and technical affordances of the news organization: adequate staff who can use the technical affordances of the news organization. Scaling the use of the attention apparatus requires decisions on which affordances to employ. A special news broadcast on television will gather a large audience. However, securing a time slot for a special broadcast requires interruption, shifting programing and securing the technical and journalistic staff to make it happen. Online reporting is suited for immediacy, but it does not possess the institutional gravity of the live television broadcast, which sometimes gathers millions of viewers. At the same time immediate and versatile online reporting enables the spreading of Yle content on social media platforms, such as Facebook, thus increasing the reach of the coverage. Regular considerations of news value (Galtung and Ruge Citation1965; Harcup and O’Neill Citation2017) thus change in the context of reporting on a hybrid media event of terrorist violence. Here we can see the professional conditions of journalism shifting the scale of the attention apparatus. The scale of reporting is also considered in relation to perceived audience expectations: Yle aims at reporting events widely but is cautious of magnifying the event through excessive attention. This is connected to the societal responsibilities of journalism which we discuss further in our conclusions.

Conclusion: The Attention Apparatus and Hybrid Media Events of Terrorist Violence

The news organizations' activation as an attention apparatus has societal consequences. Without the apparatus, there would be no hybrid media event even if an act of violence took place. This is why conceptualizing the conditions and affordances of the attention apparatus helps to unravel the workings of naturalized media power (c.f. van Ess Citation2017, 15). Even if the Internet and social media provide possibilities for anybody to have their say, it is the attention at the disposal of the news organizations that transforms an incident into an event followed by a wide audience. In other words, despite the growth of social media and different internet platforms, there still is a certain “concentration of symbolic resources in the principal mass-media entities” (van Ess Citation2017, 15). These symbolic resources appear in the form of the available affordances at the disposal of the news organization. The aim is to balance the perceived audience expectations, professional conditions of journalism and societal responsibilities of journalism. The consequence is that the apparatus attracts and structures attention in different ways, resulting in sustaining the regime of attention (Boullier Citation2009 in Citton Citation2017).

presents an illustration of the three conditions of the attention apparatus (perceived audience expectations, professional conditions of journalism and societal responsibilities) and temporal affordances, which the news organization uses to manage attention in hybrid media events. The arrows represent the ability to scale the volume of reporting through the use of affordances. In the following section, we discuss how different affordances are emphasized within each condition.

Perceived audience expectations are mirrored in the pressure on news organizations to produce immediate and abundant reporting. The audience pays attention not only to the event but also to the successes and failures of the news organization in managing attention. Perceived audience expectations are also integral in the ritual performance of liveness, which is important in creating and sustaining a sense of community in disturbing events. Interruption disturbs the everyday schedules of audiences but also provides a way to gain the attention of audiences and provide them with verified information.

Professional conditions of journalism emphasize the immediacy required to compete with other news organizations on account of audience attention in multiple platforms. At the same time, the professional demand for publishing only accurate, fact-checked information goes against the demands of immediacy and liveness. The pressure for immediate reporting creates friction in relation to professional expectations of journalism to verify information before publishing. The active role of social media in hybrid media events may challenge the professional norms and values of traditional journalism (Konow-Lund and Olsson Citation2017). Audiences utilize the affordance of immediacy to post information, rumors, images and videos, and journalists have to react to this flood of publications. According to our informants, the most important goal is to publish only verified facts, even at the cost of immediacy. The performance of liveness also creates pressure for the professional expectations of journalism. This is apparent when journalists juggle not knowing, repeating known facts, rebutting rumors and citing contradictory sources to perform liveness. In other words, the journalistic professional norms of accuracy, impartiality, verification and balance (Belair-Gagnon Citation2015, 5) are all under pressure and of heightened importance in reporting terrorist attacks. Transience offers some flexibility to the demands of immediacy, as it gives the possibility for gradual temporal layering of the events and corrections of possible errors. This shows how the hybridity of the event creates a situation where journalists are caught between different actors and logics of knowledge production (Cf Witschge et al. Citation2019), having to construct their role as journalists with the available affordances.

Societal responsibilities in terrorism coverage involve all the affordances: immediacy, liveness and interruption. Immediacy and liveness may have consequences for the unfolding of the events and possibly endanger victims or possible hostages still at stake (cf. Sumiala et al. Citation2018). Immediacy also increases the risk of publishing inaccurate or false information and accusing people who later turn out to be innocent incidental bystanders (Mortensen Citation2015). Publishing live, possibly traumatizing footage, can also have serious societal impacts. As interruption creates a collective, societal sense of urgency and alertness, the journalists have to balance between meeting perceived audience expectations and winning in the news competition. In trying to meet these goals, journalists may unintentionally raise the level of collective anxiety in society, which, in turn, advances the cause of the terrorists themselves.

The obvious societal and ethical concerns of the apparatus came up in our interviews from two perspectives: firstly, in the difficulty to turn off the news apparatus and secondly in the possibility of the news apparatus working for terrorists’ interests. The inability to turn off the attention apparatus was seen as problematic. The sudden nature of terror attacks forces the news organization to ensure resources for reporting and begin journalistic processes even before there is any confirmed information on the magnitude of the event. Once the reporting is started, the planned material is finalized and published and the process of reporting is seldom interrupted until the next day. Earlier research has recognized this tendency of accelerated interpretation of causes during hybrid media events of terrorist violence (Sumiala et al. Citation2018). On a societal level, these interpretations can turn out to be based on stereotypical perceptions and old mnemonic schemes (Zelizer Citation2017).

Our informants also discussed the issue of scale in using the news apparatus. Employing the full range of the apparatus was seen as problematic in terms of the scale of attention created by interruption and immediacy of a special news broadcast. Excessive reporting of terrorist attacks creates a loop of attention: The perceived audience expectations create large-scale reporting, which, in turn, feeds the audience’s appetite for the event. Large-scale use of the attention apparatus was also seen as questionable because it provides attention for terrorists and creates fear in society, which may also serve the interests of different groups who want to politicize the event further. The assumption that heightened media attention may encourage further attacks has been empirically verified by Michael Jetter’s study of U.S. reporting on terrorist attacks (Jetter Citation2017). Terrorist organizations respond to previously established criteria of newsworthiness but also trends in modern media such as mobility and immediacy (Stępińska Citation2010, 203).

The discussion on societal responsibility probably appears particularly strong in our research setting. The Nordic tradition of the societal tasks of public service broadcasting weighs heavily on the news organization. In the public service context, creating as much attention as possible is not the only aim, as this must be weighed against journalistic goals and ethics. In the interviews, these issues were expressed concerning the problematics of providing attention to terrorist aims but also specifically concerning Yle’s duties determined in ‘The Act on the Finnish Broadcasting Company’ (Citation1993). In this legislative text, the duty of making “provision for television and radio broadcasting in exceptional circumstances” is especially mentioned. Interviewees mentioned that it is important for Yle to actively report on violent events to offer trustworthy and reliable information in a situation where there is a lot of uncertainty and rumors. Finland has experienced two school shootings and a couple of other instances of mass attacks against the public since 2005. The shortcomings of reporting during these instances and the attention towards global terrorism have led to conscious reflections about covering violent attacks among journalists (Raittila et al. Citation2008; Raittila et al. Citation2009), specifically in the public service media. Similar discussions have been observed in other Nordic countries, Norway in particular, after the Utoya massacre (Figenschou and Thorbjørnsrud Citation2017). This has increased consciousness on the relationship between journalism and the reporting of violent attacks.

The attention apparatus is not a precision tool. It is an assemblage of equipment, affordances and human capabilities, and it can attract, steer and manage the audiences’ collective attention. A violent attack turns into a hybrid media event in this interaction. Representation of disturbing events is constitutive of our reality, which makes the process of mediation and managing attention acutely political and accentuates the symbolic power of news media organizations. The conceptualization of the attention apparatus brings forth questions regarding the exercise of communicative power and the influence the news media has in identifying, defining and framing certain situations as crises of global significance demanding concerted action.

Supplementary_Material

Download MS Word (15.4 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Liége attack took place in Belgium on the 29th of May 2018. A prisoner, on the day of release, shot two police officers and a bystander.

2 The Strasbourg attack took place in France on the 12th of December 2018. A man attacked civilians in the city's Christmas market with a revolver and a knife, killing five and wounding 11.

3 The Christchurch attack took place in New Zealand on the 15th of March 2019. A gunman attacked two mosques in Christchurch, killing 51 people.

4 The newsroom refers to the journalistic news production, whilst the news organization includes technical and administrative dimensions of the organization as well.

5 The interviews and newsroom observations were conducted by the first author, as were the qualitative coding and data analysis.

6 The abbreviation identifies the interviewees: (I1=Informant 1 etc.)

References

- Abubakar, Tasiu Abdullahi. 2019. “News Values and the Ethical Dilemmas of Covering Violent Extremism.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 97 (1): 278–298.

- The Act on Yleisradio (Finnish Broadcasting Company). 1993. Section 7, Accessed 23 June 2020. https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1993/en19931380.pdf.

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2009. What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays. Translation. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Alexander, Yonah. 1980. “Terrorism and the Media: Some Observations.” Terrorism: An International Journal 3 (3/4): 179–183.

- Alexander, Jeffrey C. 2012. Trauma. A Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Altheide, David L. 1985. “Impact of Format and Ideology on tv News Coverage of Iran.” Journalism Quarterly 62 (2): 346–351.

- Archetti, Cristina. 2013. Understanding Terrorism in the Age of Global Media. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Auslander, Philip. 2008. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. London: Routledge.

- Belair-Gagnon, Valerie. 2015. Social Media at BBC News: The re-Making of Crisis Reporting. London: Routledge.

- Berkowitz, Dan. 1997. “Non-routine News and Newswork: Exploring a What-a-Story.” In Social Meanings of News: A Text-ReaderDan Berkowitz, 362–375. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Boullier, D. 2009. Les industries de l'attention: fidélisation, alerte ou immersion [The attention industries: loyalty-creation, alertness or immersion]. Réseaux, 154.

- Bourdon, Jérôme. 2000. “Live Television is Still Alive: On Television as an Unfulfilled Promise.” Media, Culture & Society 22 (5): 531–556. doi:10.1177/016344300022005001.

- Boydston, Amber E., Anne Hardy, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2014. “Two Faces of Media Attention: Media Storm Versus Non-Storm Coverage.” Political Communication 31: 509–531. doi:10.1080/10584609.2013.875967.

- Caldwell, John Thornton. 1995. Televisuality: Style, Crisis, and Authority in American Television. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Campo, Enrico. 2015. “Relevance as Social Matrix of Attention in Alfred Schutz.” Sociology and the Life-World 12 (6): 117–148.

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chalfont, Lord. 1980. “Political Violence and the Role of the Media: Some Perspectives – the Climate of Opinion.” Political Communication and Persuasion: An International Journal 1 (1): 79–78.

- Citton, Yves. 2017. The Ecology of Attention. Translation. Barnaby Norman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Corbin, Juliet. 2017. “Grounded Theory.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12 (3): 301–302. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1262614.

- Couldry, Nick. 2004. “Liveness, ‘Reality’ and the Mediated Habitus from Television to the Mobile Phone.” Communication Review 7 (3): 353–361.

- Davenport, Thomas H., and John C. Beck. 2001. The Attention Economy. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Dayan, Daniel, and Elihu Katz. 1992. Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Feuer, Jane. 1983. “The Concept of Live Television: Ontology as Ideology.” In Regarding Television: Critical Approaches – an Anthology, edited by Ann Kaplan, 12–21. Los Angeles: American Film Institute.

- Figenschou, Tine Usted, and Kjersti Thorbjørnsrud. 2017. “Disruptive Media Events: Managing Mediated Dissent in the Aftermath of Terror.” Journalism Practice 11 (8): 942–959. doi:10.1080/17512786.2016.1220258.

- Flusser, Vilem. 1984. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaction Books.

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. “The Confessions of the Flesh.” In Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977, edited by Colin Gordon, s194–s228. New York: Pantheon.

- Frosh, Paul, and Amit Pinchevski. 2009. “Crisis-readiness and Media Witnessing.” The Communication Review: Who’s the Bigger Brother? How War Aggravates the Relationships Among Media, Government and Public 12 (3): 295–304. doi:10.1080/10714420903124234.

- Galtung, Johan, and Mari Holmboe Ruge. 1965. “The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers.” Journal of International Peace Research 2: 64–90.

- Harcup, Tony, and Deidre O’Neill. 2001. “What is News? Galtung and Ruge Revisited.” Journalism Studies 2 (2): 261–280.

- Harcup, Tony, and Deidre O’Neill. 2017. “What is News? News Values Visited Again.” Journalism Studies 18 (12): 1470–1488. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2016.1150193.

- Hokka, Jenni. 2017. “Making Public Service Under Social Media Logics.” International Journal of Digital Television 8 (2): 221–237.

- Jetter, Michael. 2017. “The Effect of Media Attention on Terrorism.” Journal of Public Economics 153: 32–48.

- Katz, Elihu, and Tamar Liebes. 2007. “‘No More Peace!’: How Disaster, Terror and war Have Upstaged Media Events.” International Journal of Communication 1: 157–166.

- Konow-Lund, Maria, and Eva-Karin Olsson. 2017. “Social Media’s Challenge to Journalistic Norms and Values During a Terror Attack.” Digital Journalism 5 (9): 1192–1204.

- Mortensen, Mette. 2015. “Conflictual Media Events, Eyewitness Images, and the Boston Marathon Bombing (2013).” Journalism Practice, [s. l.] 9 (4): 536–551. doi:10.1080/17512786.2015.1030140.

- Olsson, Eva-Karin. 2009. “Media Crisis Management in Traditional and Digital Newsrooms.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 15 (4): 446–461. doi:10.1177/1354856509342780.

- Olsson, Eva-Karin. 2010. “Defining Crisis News Events.” Nordicom Review 31 (1): 87–101.

- Packer, Jeremy. 2010. “What is an Archive? An Apparatus Model for Communications and Media History.” The Communication Review 13 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1080/10714420903558720.

- Raittila, Pentti, Paula Haara, Laura Kangasluoma, Kari Koljonen, Ville Kumpu, and Jari Väliverronen. 2009. Kauhajoen koulusurmat mediassa (The Kauhajoki school shootings in media). University of Tampere, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Publications A 111.

- Raittila, Pentti, Katja Johansson, Laura Juntunen, Laura Kangasluoma, Kari Koljonen, Ville Kumpu, Ilkka Pernu, and Jari Väliverronen. 2008. Jokelan koulusurmat mediassa (The Jokela school shootings in media). University of Tampere, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Publications A 105.

- Rao, Shakuntala, and Pradeep N’ Weerasinghe. 2011. “Covering Terrorism: Examining Social Responsibility in South Asian Journalism.” Journalism Practice 5 (4): 414–428.

- Schmid, Alex P., and Albert J. Jongman. 1988. Political Terrorism: A New Guide to Actors, Authors, Concepts, Data Bases, Theories and Literature. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing.

- Scott, John L. 2001. “Media Congestion Limits Media Terrorism.” Defence and Peace Economics 12 (3): 215–227.

- Steensen, Steen, Elsebeth Frey, Harald Hormmoen, Rune Ottosen, and Maria Theresa Konow-Lund. 2018. “Social Media and Situation Awareness During Terrorist Attacks: Recommendations for Crisis Communication.” In Social Media use in Crisis and Risk Communication, edited by Harald Hornmoen, and Klas Backholm, 277–295. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10. 1108/978-1-78756-269-120181017/full/pdf?title=social-media-and-situation-awareness-during-terrorist-attacks-recommendations-for-crisis-communication.

- Stępińska, Agnieszka. 2010. “9/11 and the Transformation of Globalized Media Events.” In Media Events in a Global age, edited by Nick Couldry, Andreas Hepp, and Friedrich Krotz, 209–222. London, NY: Routledge.

- Sumiala, J., M. Tikka, and K. Valaskivi. 2019. “Charlie Hebdo, 2015: ‘Liveness’ and Acceleration of Conflict in a Hybrid Media Event.” Media, War & Conflict 12 (2): 202–218. doi:10.1177/1750635219846033.

- Sumiala, J., K. Valaskivi, M. Tikka, and J. Huhtamäki. 2018. Hybrid Media Events: The Charlie Hebdo Attacks and the Global Circulation of Terrorist Violence. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Tenenboim-Weinblatt, Keren, and Motti Neiger. 2018. “Temporal Affordances in the News.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 19 (1): 37–55.

- Tuchman, Gaye. 1997. “Making News by Doing Work: Routinizing the Unexpected.” In Social Meanings of News: A Text-Reader. Dan Berkowitz, 173–192. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Uricchio, William. 1998. “Television, Film and the Struggle for Media Identity.” Film History 10 (2): 118–127.

- Usher, Nikki. 2014. Making News at The New York Times. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Usher, Nikki. 2020. “News Cartography and Epistemic Authority in the Era of Big Data: Journalists as Map-Makers, Map-Users and Map-Subjects.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 247–263. doi:10.1177/1461444819856909.

- Valaskivi, Katja, and Johanna Sumiala. 2014. “Circulating Social Imaginaries: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (3): 229–243.

- van der Meer, Toni G.L.A, Piet Verhoeven, W. J. Johannes, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2017. “Disrupting Gatekeeping Practices: Journalists’ Source Selection in Times of Crisis.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 18 (9): 1107–1124. doi:10.1177/1464884916648095.

- van Ess, Karin. 2017. The Future of Live. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Webster, James G. 2014. The Marketplace of Attention. Cambridge, London: The MIT Press.

- Wilkinson, Paul. 1997. “The Media and Terrorism: A Reassessment.” Terrorism and Political Violence 9 (2): 51–64.

- Williams, Raymond. 1974. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. London: Fontana.

- Witschge, Tamara, C. W. Anderson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida. 2019. “Dealing with the Mess (we Made): Unraveling Hybridity, Normativity, and Complexity in Journalism Studies.” Journalism 20 (5): 651–659.

- Wu, Tim. 2017. The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to get Inside our Heads. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Ytreberg, Espen. 2009. “Extended Liveness and Eventfulness in Multi-Platform Reality Formats.” New Media & Society 11 (4): 267–485.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2017. “Seeing the Present, Remembering the Past: Terror’s Representation as an Exercise in Collective Memory.” Television and New Media 19 (2): 136–145.