ABSTRACT

The perceived sexual threat of ethnic outgroups has been argued to contribute to anti-immigrant attitudes within societies. The current study investigates to what extent news media might contribute to such negative outgroup perceptions by analyzing implicit sexual threat associations in Dutch news. The study draws on a sample of more than two million news articles published between 2008 and 2018 in five major Dutch newspapers. To identify implicit bias in this corpus, we use word embeddings—an advanced language modeling technique in Natural Language Processing (NLP). The results show that ethnic outgroups (i.e., nationalities that were most prominently represented among asylum applications in the Netherlands during the refugee crisis) are associated more strongly with sexual threat than ethnic ingroups. These findings proved robust across a diverse set of outgroups and ingroup nationalities and names, and point to the existence of considerable implicit bias in the coverage of ethnic minorities. Moreover, the sexual threat associated with Arabic names has grown stronger since the “refugee crisis”. Such implicit biases reflect and potentially reinforces individuals’ implicit associations between ethnic minorities and sexual threat, potentially explaining growing anti-immigration attitudes, especially since the refugee crisis.

News media, as a main information source, are often accused of begin skewed to the negative side when it comes to reporting about the conducts and traits of ethnic “others”. News coverage about immigrants seems to be replete with distressing images of illegality, crime, terrorism and the allegation of unfair labor market competition (Bennett et al. Citation2013; Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017; Pruitt Citation2019). Herewith a disturbing portrayal is constructed of refugees and immigrants as a threat to the economic, physical, and cultural well-being of host-countries. Extending individuals’ direct experience with outgroup members, exposure to mediated associations between such threats and ethnic outgroups has been argued to foster anti-immigrant sentiments (Lee and Nerghes Citation2018) and harm intergroup outcomes (Seate and Mastro Citation2016).

One particular type of outgroup threat has been argued to be especially powerful in shaping anti-immigrant attitudes: Sexual threat (Sarrasin et al. Citation2015; Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017). News messages might fulfill an important role in linking incidents of sexual violence and assault to ethnic minorities (e.g., Warner Citation2004). For example, among the diverse storylines that unfolded in the aftermath of the so-called European “refugee crisis” in 2014/2015, relatively high shares of news articles where devoted to numerous incidents of sexual assault, especially those that occurred at several cities in Germany during New Year’s Eve 2014/2015 (Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017). The pairing of such messages with specific racial minority members might further perpetuate and reinforce the idea that outgroup men are more sexually dangerous to ingroup women than ingroup men (Nagel Citation2004; Navarrete et al. Citation2010), fostering fear and eroding intergroup relations (Sarrasin et al. Citation2015). In sum, to understand how public opinion on outgroups can be shaped beyond direct experience, it is essential to understand how news media, either explicitly or implicitly, associates such outgroups with sexually threat as a powerful outgroup threat.

The current study builds on insights from intergroup threat theory to investigate implicit associations in news coverage between a broad range of ethnic outgroups (in terms of nationalities that were most prominently represented among asylum applications in the Netherlands during the refugee crisis) and ingroups and sexual threat cues, both before and in the wake of the European refugee crisis (2008–2018). Borrowing from the field of computational social sciences, we apply advanced methods of Natural Language Processing (NLP) to large volumes of news media data in order to understand media bias in the coverage of sexual assault and misconduct in relation to ethnic minorities. More specifically, we use word embeddings to explore whether implicit attributions of sexual threat in large corpora of news content vary across ethnic groups and are likely to shift across time. We base our evidence on the census of articles that appeared in five leading Dutch newspapers between 2008 and 2018, including over two million news articles. In the past two decades, the Netherlands has adopted restrictive asylum policies alongside the development of a strong anti-immigrant discourse in news environment (Aarts, Semetko, and Semetko Citation2003; Vliegenthart and Boomgaarden Citation2007; Lesińska Citation2014; Jacobs et al. Citation2018). Many other European countries have witnessed comparable changes in recent years (Lesińska Citation2014), making the Netherlands a particularly relevant and interesting case to put our hypotheses to the test.

The current study contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, although sexual threat is considered an important facet of outgroup prejudice and intergroup tensions (Sarrasin et al. Citation2015), surprisingly little attention has been devoted to this type of threat from a media scholarship and journalism perspective. More specifically, it remains unclear to what extent news media might reflect or reinforce (implicit) beliefs about immigrant groups and sexual threat. Second, and by tracing implicit associations of a diverse set of ingroup and outgroup members over a longer period of time (i.e., 27 years), we are able to draw conclusions about shifts in media bias following extensive coverage of a highly newsworthy event (i.e., the refugee crisis). Finally, and methodologically, the current study demonstrates how word embeddings can be used as a tool to study news media bias at the aggregate levels.

Sexual Threat Cues in News Environments: Intergroup Threat Theory

Arguably one of the main sources of intergroup conflict and prejudice is the idea that “others” pose threats to the ingroups’ cultural values, safety, and well-being. Intergroup threat theory (ITT) posits that threatening perceptions of outgroups cause intergroup contact to be associated with anxiety (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000; Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison Citation2009). The experience of such fearful encounters provokes outgroup prejudice with detrimental consequences for intergroup outcomes (Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison Citation2009; Harwood Citation2010; de Rooij, Goodwin, and Pickup Citation2015).

ITT distinguishes between symbolic, economic and physical threats, and argues that it is the perception of these types of threats what makes them so powerful. Whether or not real threat exists, the perceived threat is predicted to increase prejudice levels against outgroup members. In other words, and even in the absence of actual threat, false threat cues can have real consequences for intergroup prejudice (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000; Stephan, Ybarra, and Morrison Citation2009).

News media offer an important source of information regarding what and whom to fear. Threat cues are abundant in news environments due to the signaling function of news media to inform citizens about key events and journalists’ and audiences’ tendency to focus on the negative rather than the positive (i.e., negativity bias) (Harcup and O’Neill Citation2001; Lengauer, Esser, and Berganza Citation2011; Trussler and Soroka Citation2014). The literature offers ample examples of the widespread occurrence of threat cues in news environments (e.g., Dixon and Linz Citation2000; Dixon and Williams Citation2015; Jacobs Citation2017; Van der Linden and Jacobs Citation2017; Lee and Nerghes Citation2018). Studying and understanding these types of threats in mediated environments is crucial, as exposure to such content has been shown to indirectly affect attitudes towards immigrants via intergroup anxiety (Seate and Mastro Citation2016) and fear (Jacobs, Hooghe, and de Vroome Citation2017).

Symbolic, economic and physical threats, as stipulated by ITT, resonate in mediated representations of outgroup members. First, symbolic threats are rooted in the perceived intergroup differences in norms, beliefs, and values (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000). The representation of ethnic minorities in terms of a threat to host-countries cultural heritage, traditions and habits express symbolic threat (Seate and Mastro Citation2016). Popular nationalist parties prominently make use of symbolic threat cues in partisan messages (Betz Citation2013), with adverse consequences for intergroup perceptions (Matthes and Schmuck Citation2017), such as the belief that immigrants resist assimilation (Croucher Citation2013). Second, economic threats refer to the belief that outgroup members endanger the availability of jobs and wealth for members of the host country. The representation of issues related to immigration in terms of economic threats has commonplace in the news coverage (Haynes, Devereux, and Breen Citation2005; Fryberg et al. Citation2012), fostering the idea that ethnic minorities are here to “steal our jobs”.

Third, and of particular interest to the current study’s aim, numerous content analysis point to the existence of physical threats in mediated environments. Evidence exists for linkages between ethnic minorities and criminal threat in both the US and European media environment. In US mainstream media, Blacks and Latinos are disproportionally associated with criminality (Dixon and Linz Citation2000). Likewise, crime news in newspapers in Flanders and the Netherlands frequently links ethnic minority members to violence, terror, and crime, herewith constructing a threatening image (Jacobs Citation2017; Jacobs et al. Citation2018) and evoking fear (Debrael et al. Citation2019). Additionally, European media outlets tend to link terrorism with religion, particularly in their representation of the Islam (e.g., Ahmed and Matthes Citation2017). These threat cues seem especially powerful as ethnic minorities are more likely being identified as recidivists in crime articles while (mitigating) circumstances are less likely being reported. Considerable variation, however, seems to exists between types of outgroups, with distant outgroups (such as North Africans) receiving most negative evaluations (Jacobs Citation2017).

A particularly powerful physical threat cue relates to the danger of sexual assault—especially as outgroup men are stereotypically perceived as being more sexually dangerous to ingroup women than ingroup men (Nagel Citation2004; Navarrete et al. Citation2010). Yet, and despite that news media has long been accused of associating ethnic minorities with issues of sexual violence and assault, surprisingly little attention has been devoted to the association between ethnic minorities and sexual threat in news coverage. An exceptional study that did investigate sexual threat, concludes that UK news messages about sexual offenses are more likely to mention the offenders’ ethnicity in case the offender was part of an ethnic minority group, herewith putting forward an image of (male) immigrants as sexual perpetrators (Grover and Soothill Citation1996 ).

In sum, evidence for the representation of ethnic minorities in terms of sexual threat is limited. Yet, based on numerous content analytical studies offering support for symbolic, economic, and physical threat cues in news coverage of ethnic outgroups, it is expected that ethnic minorities are associated more strongly with sexual threat in news coverage than ethnic ingroups. We expect this to be the case for general references to ethnic outgroups (in terms of nationalities and labels, such as “refugees”) and for references to members of those ethnic outgroups (in terms of specific first names). We posit:

H1a: Sexual threat associations in Dutch news will be amplified for general references to ethnic outgroups (in terms of nationalities and labels) as compared to references to ethnic ingroups.

H1b: Sexual threat associations in Dutch news will be amplified for references to ethnic outgroup members (in terms of first names) as compared to references to ethnic ingroup members.

The Impact of External Events on Implicit Sexual Threat in the News Media: The Case of the Refugee Crisis

Second, it can be assumed that the extent to which ethnic minorities are linked to sexual threat shifts across time following the occurrence of key events. Fueled by influxes in asylum applications, the debate about immigration has undergone large fluctuations in the past decades, with likely consequences for the strength of threatening representations of members of refugee groups. Global conflict-related forced displacement reached a record high since World War II in 2014, with an estimated 59.5 million individuals forced to leave their homes (The UN Refugee Agency Citation2015, 2). From 2014 on, the number of asylum applications in the European Union (EU) from non-EU member countries has accelerated rapidly, reaching unprecedented levels in 2015 (Eurostat Citation2017). Over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers were registered in European countries in 2015, mainly from individuals from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan (Eurostat Citation2016, 1). The Netherlands saw a sharp increase in the number of asylum applications in 2014–2016: 82.958 fist asylum claimants were registered, mainly from individuals from Syrian and Eritrean descent (Algemene Rekenkamer Citation2016, 9).

The shifting equilibrium between the host population and out-group members has amplified negative sentiments towards ethnic or racial “others”. The so-called refugee crisis inspired contentious social and political debates, resonating in news coverage fostering anti-immigrant sentiment and social tensions both in the Netherlands and Europe more generally. Popular nationalist political parties seemed to have taken advantage of fears and anxiety regarding immigration to mobilize votes and enact restrictive asylum policies. Notably, evidence confirms that immigration has been a primary motivation for the exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union (Brexit) (Goodwin and Milazzo Citation2017).

In the wake of the refugee crisis, several incidents were covered in which ethnic minorities were explicitly linked to sexual assault cases. Most noticeably, the incidents that occurred in several German cities (Cologne, Hamburg) around NYE 2014/ 2015 were covered extensively by media outlets (Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017). The story went viral and represented a turning point in public opinion about refugees in Germany: Acceptance of immigrants from Arab or African countries decreased after this point in Germany (Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017). Also, in the Dutch media, the sexual assaults of NYE were extensively covered, and its implications discussed. In addition, several sexual assault cases that occurred on Dutch soil were covered (e.g., Friedrichs Citation2018). Popular nationalist political parties used these incidents to question asylum policies, herewith further fueling fear and panic about the safety of ingroup women.

In the current study, we consider the refugee crisis as an exceptional real-world trigger altering the discourse about refugee groups and associated characteristics. Drawing on insights from ITT, we expect that the refugee crisis has mobilized journalists to voice citizens’ increased feelings of sexual threat in news messages, herewith galvanizing already existing associations between ethnic outgroups and sexual threat in the news environment. We formulate:

H2a: Sexual threat associations in Dutch news will be amplified for general references to ethnic outgroups (in terms of nationalities and labels) as compared to references to ethnic ingroups.

H1b: Sexual threat associations in Dutch news will be amplified for references to ethnic outgroup members (in terms of first names) as compared to references to ethnic ingroup members.

H2a: The association between general references to ethnic outgroups (in terms of nationalities and labels) and sexual threat increased in the wake of the refugee crisis, while the association between general references to ethnic ingroups and sexual threat has remained stable across time.

H2b: The association between references to ethnic outgroup members (in terms of first names) and sexual threat increased in the wake of the refugee crisis, while the association between general references to ethnic ingroup members and sexual threat has remained stable across time.

Method

Previous literature on the role of the media in issues of race and ethnicity has investigated the construction of representations of minority members from a critical stance. Particularly, and from a cultural studies perspective, scholars build on concepts of power and “othering” to argue that media represents minorities as inherently different and subordinate (Said Citation1979; Hall Citation1997). In such analysis, a systematic focus on implicitness is deemed important as “social norms against prejudice and discrimination, which are known by people who express racist opinions, force them to be careful in what they say and write, so that many meanings tend to remain implicit or are expressed indirectly” (Van Dijk Citation1991, 181). Due to its labor-intensive nature, these types of analyses tend to be qualitative in nature and relatively limited in scope.

Due to advances in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing (NLP), it has become possible to decipher implicit bias from large corpora of texts. In particularly the advent of word embeddings (Mikolov et al. Citation2013; Mikolov, Yih, and Zweig Citation2013; Le and Mikolov Citation2014) has opened up methodological possibilities for detecting and quantifying hidden forms of bias. Recent studies have successfully employed such models to replicate universal implicit bias in large text corpora (Bolukbasi et al. Citation2016; Caliskan, Bryson, and Narayanan Citation2017; Garg et al. Citation2018). More precisely, the same biases that are found in social psychology work, such as the stronger association between African (versus European) American names and unpleasant attributes than pleasant attributes (Greenwald, Mcghee, and Schwartz Citation1998), have been replicated in large text corpora from the web using word embeddings (Caliskan, Bryson, and Narayanan Citation2017).

Word embeddings transform human language to numerical representations, capturing the meaning of language. Using unsupervised algorithms, embedding models are trained on a large amount of data (such as social media posts, books, news articles) in order to “learn” particular patterns. In embedding models, words are assigned a position in a high-dimensional vector space by computing the relationship for each word to all other words across the number of times it occurs. The key assumption of embedding models is that words sharing semantic meaning appear close to each other in this vector space. Word embeddings are applied in a wide range of lexical tasks to resolve natural language processing (NLP) problems, such as information retrieval, sentiment analysis, and machine learning.

Importantly, word embeddings allow computers to identify implicitly encoded nuances and bias of human language. As “semantics, the meaning of words, necessarily reflects regularities latent in our culture, some of which we now know to be prejudiced” (Caliskan, Bryson, and Narayanan Citation2017, 14), learning the meaning of words on the basis of human-generated textual data will likely uncover implicit bias. Aptly referred to as an “AI stereotype catcher” (Greenwald Citation2017), word embeddings allow the researcher to quantify bias by measuring the distance between specific groups and attributes in the training corpus. For example, Bolukbasi et al. (Citation2016) investigated the association between gender categories (e.g., she versus he) and neutral/genderless nouns (e.g., programmer, homemaker). The study confirmed would be expected based on knowledge of social stereotypes: Words denoting professions such as programmer, politician, and architect appear closer to the word he than the word she.

Word embeddings return a cosine similarity score indicating the distance between words referring to social categories and specific attributes, with higher values denoting a stronger association. It has been argued that this measure is similar to how IAT’s measure implicit bias using reaction time: The speed with which participants categories social categories with specific attributes seems to resemble semantic nearness of these concepts in textual data (Caliskan, Bryson, and Narayanan Citation2017). Following this argumentation, the current study extracts the strength of associations between words denoting sexual threat and words indicating group membership as a measure of implicit news bias.

Data and Training

Pioneer studies that have used word embeddings to replicate widely-held social stereotypes and bias have drawn on models trained on some form of web data (such as Wikipedia content, Google News, Google books) (see Bolukbasi et al. Citation2016; Caliskan, Bryson, and Narayanan Citation2017; Garg et al. Citation2018). The current study is unique in the sense that we train our models on journalism content. More specifically, we draw on a database containing all news articles that appeared between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2018, in five leading national Dutch newspapers: Trouw (N = 333,961), Volkskrant (N = 413,292), Telegraaf (N = 578,572), Algemeen Dagblad (N = 1,219,265) and NRC Handelsblad (N = 383,645) covering a total of 2.2 million news articles. De Telegraaf and Algemeen Dagblad are typically considered popular newspapers that lean towards the politically right of the center. Although De Telegraaf has suffered the loss of readership overtime, it remains the largest newspaper in terms of circulation rates. Among the readership of NRC Handelsblad, de Volkskrant and Trouw high education and income levels are overrepresented (Bakker and Scholten Citation2009). Coming from a Catholic background, de Volkskrant is now characterized by its secularized, left-of-center profile. The political orientation of the quality newspaper NRC Handelsblad has been described as neoliberal-conservative. Finally, of the selected newspapers Trouw has the lowest circulation rate, and is characterized by its progressive protestant inclination (Van der Eijk Citation2000, 315).

To investigate the effect of the refugee crisis on the strength of sexual threat associations, we trained two embedding models. To capture the before refugee crisis period, the first model was trained on the newspaper articles published between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2013 (N = 1,255,455). To capture the period during and after the refugee crisis, we train the second model on the articles published between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2018 (N = 949,036).

To create the word vectors, we use Word2Vec from the Gensim library in Python. Several preprocessing steps were taken. All duplicate sentences were removed from our dataset in order to improve the quality of our embeddings. Next, sentences were lowercased and stopwords removed. Finally, we train the word embedding models on unigrams and bigrams using continuous bag of words (CBOW) algorithm (300 dimensions, window size = 10, negative sampling = 5).

Dictionaries Capturing Ethnic Categories

In the next step, we created several dictionaries (i.e., lists of words) in order to operationalize ethnic groups. First, we differentiate between outgroup and ingroup nationalities. We create a list of words that refer to the nationalities that were most prominently represented among asylum applications in the Netherlands during the refugee crisis (VluchtelingenWerk Netherland Citation2016). More specifically, we include references to the following nationalities: Afghan, Bengali, Eritrean, Gambian, Iraqi, Nigerian, Pakistani, Refugees, Senegalese, Somali, Sudanese and Syrian.Footnote1 We complemented this list with general terms often used in news coverage to denote these groups: refugees, immigrants, and migrants. Both singular and plural references to these nationalities were included.

In addition, a list was created to capture references to ethnic ingroups. In addition to references to the Dutch, we consider members of direct neighboring countries as culturally similar and part of ethnic ingroups: Belgians, Germans, French, Luxembourgers. Finally, also references to Europeans are considered here as part of the ethnic in-group.

Media reports often linked “Arabs” or “North Africans” to incidents and assaults that occurred in the aftermath of the refugee crisis (Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017; Pruitt Citation2019). It might be that such news stories link sexual assaults to Arabic or North African individuals without explicitly referring to ethnicities. To capture bias towards members of these ethnic groups, dictionaries were created with a set of names that typically originate from Arabic countries and a set of names that typically originate from the Netherlands. Specifically, the following list was compiled with common Arabic first names: Mohammed, Adil, Tarik, Jamal, Youssef, Hamza, Kamal, Samir, Driss, Ahmed, Omar, Ali, Said, Munir, Rashid, Murad, Naima. Likewise, a bundle of the following typical male Dutch first names was included: Bas, Maarten, Sander, Thijs, Roel, Lucas, Daan, Remco, Jeroen, Joris, Teun, Thomas, Matthijs, Bob, Michiel, Wouter, Joost, Bram. These lists were derived from extant research into labor market discrimination of Arabic-named job applicants (Blommaert, Coenders, and van Tubergen Citation2014).

Dictionary Capturing Sexual Threat

Next, we create a list of words capturing sexual threat. We select 21 terms that frequently occurred in our corpus that capture dimensions of sexual threat and assault: sexual assault, (group) rape(s), fornication, incest, sex crime, sexual offense(s), rape, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, sexual violence, pawing, pedophilia, trafficking in women, forced prostitution.

Analysis

Our dataset has a nested structure. For each ethnic category (N = 21 nationalities/labels, N = 35 names) in our dataset, we have cosine similarity scores for each word indicating sexual threat (N = 21) both before and after the refugee crisis (N = 2). Due to this hierarchal structuring of the data, observations within groups might be more similar. To account for this, we use a multilevel design (Hox Citation2005), with a random intercept for each ethnic category. In the fixed part of the model, we model the effect of group membership and time to test our hypotheses.

Results

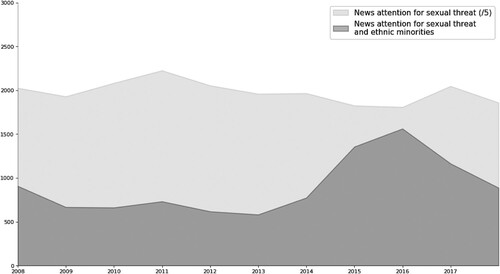

Before we move to our predictive analysis, we shortly discuss some descriptive findings. In the research period under investigation, we found 108,904 news articles referring to sexual assault. For those articles, 9.1% (N = 9918) explicitly refer to refugees, immigrants or at least one of here-studied ethnic minorities.Footnote2 shows how attention for sexual assault and ethnic minorities develops overtime. As can be seen, attention for sexual assault remains relatively stable over time. However, attention for minorities in the corpus of articles about sexual assault peaks around the year of the refugee crisis, around 2015, after which it decreases again.

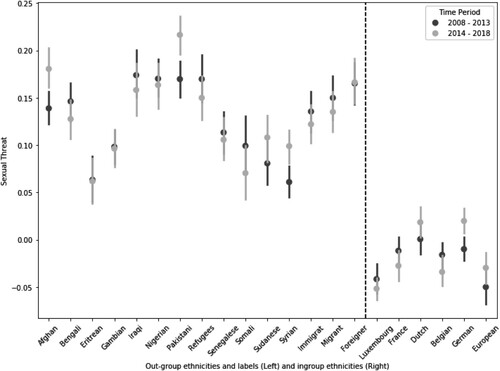

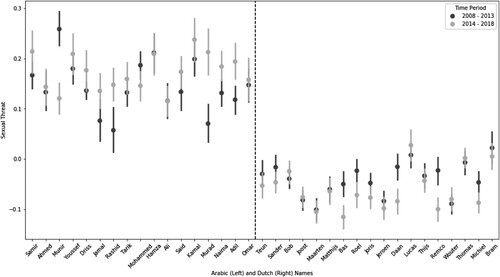

displays the results of our multilevel analysis predicting sexual threat associations between outgroup nationalities (and labels) and ingroup nationalities. Model 1 displays the main effect of group membership (outgroup vs. ingroup). In Model 2, an interaction effect is added for group membership and time. displays the results of the multilevel analysis predicting sexual threat associations between Arabic names and Dutch names. Again, we find the main effects of group membership and time in Model 1, while Model 2 displays the interaction effect.

Table 1. Multilevel model predicting the association between sexual threat and outgroup vs. ingroup nationalities.

Table 2. Multilevel model predicting the association between sexual threat and Arabic vs. Dutch names.

First, it was expected that sexual threat associations in Dutch news would be amplified for general references to ethnic outgroups (in terms of nationalities and labels) (H1a) and to ethnic outgroup members (in terms of first names) (H1b). displays that across the board, ethnic outgroups and labels score higher on the dimension of sexual threat than ethnic ingroups. Similarly, shows that Arabic names are associated stronger with sexual threat than Dutch names. , Model 1 and , Model 1 confirm that these differences are significant: general references to outgroups (in terms of nationalities and labels) are more strongly associated with sexual threat than references to ingroups. In addition, Arabic first names are more strongly associated with sexual threat than Dutch first names. Together, these results indicate that ethnic nationalities (relative to ingroup nationalities) and ethnic outgroup members (relative to ingroup members) are more strongly linked to sexual threat in Dutch news (supporting H1a and H1b).

Figure 2. Sexual threat associations between out-group ethnicities and in-group ethnicities before and after the refugee crisis.

Figure 3. Sexual threat associations between Arabic names and Dutch names before and after the refugee crisis.

Second, we expected the association between ethnic outgroups and sexual threat to increase in the wake of the refugee crisis, while the association between ethnic ingroups and sexual threat has remained stable across time (H2). displays the strength of the associations between outgroup nationalities and labels and sexual threat for both time periods. No clear over-time pattern can be distinguished: While for some groups (e.g., Nigerians, Afghans) the associations grew stronger, for other groups we find relatively stable or lower associations in the period 2014–2018 than before. Likewise, for the ethnic ingroups, a clear pattern cannot be distinguished. For most groups, the association with sexual threat remains largely the same over time. Our predictive analyses (, Model 2) confirm that these differences are not significant, indicating sexual threat associations did not grow stronger for outgroup nationalities as compared to ingroup nationalities across time. We reject H2a.

displays the associations between a set of Arabic and Dutch names and sexual threat. For most (but not all) Arabic names, the association strength with sexual threat-related terms increased after 2014. Regarding Dutch names, no clear pattern can be distinguished. , Model 2, confirms that these differences are significant: The interaction term between group membership and time is significant, indicating that in the wake of the refugee crisis, sexual threat associations became more pronounced for Arabic names, while this was not the case for Dutch names. In sum, these findings confirm H2b.

Discussion

Numerous studies contend that (news) media coverage of immigration and asylum issues provides incentives for intergroup tensions and the marginalization of ethnic minorities (e.g., Chouliaraki and Zaborowski Citation2017; Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017). In this scholarly debate, the differential evaluation of ethnic ingroup and outgroup members in terms of sexual threat in the news environment is generally neglected. The current study addresses this lacuna in the literature by analyzing the associations between ethnic ingroup and ethnic outgroup members and coverage about sexual threat. We have done so by drawing on a sample of more than 2 million news articles and by using advanced automated methods, in particular word embeddings. This method allows determining the semantical nearness between social categories and attributes.

The here-reported results confirm that compared to ethnic ingroups, ethnic outgroups are associated more strongly with sexual threat in the news. More precisely, we conclude that general references to outgroups (in terms of nationalities and labels) are more strongly associated with sexual threat compared to general references to ingroups. Likewise, the study confirms that references to outgroup members (in terms of Arabic first names) are more strongly linked to terms related to sexual threat than references to ingroup members (in terms of Dutch first names). Herewith, the findings suggest that the media discourse produces and reproduces the dominant discourse around ethnic minorities.

In addition, it was hypothesized that the refugee crisis would increase the strength of sexual threat associations in the news for ethnic outgroups, but not ethnic ingroups. This hypothesis could not be confirmed for ethnic outgroups and labels: The refugee crisis did not amplify the differential association between sexual threat and general references to ethnic outgroups relative to ethnic ingroups. The findings, however, do confirm that in the wake of the refugee crisis, sexual threat associations became more pronounced Arabic names, while this was not the case for Dutch names. In sum, we pose that intergroup and overtime factors partly account for variation in implicit sexual threat in news coverage.

These findings have considerable implications. On the one hand, the biased association between sexual threat and minorities might echo societal beliefs regarding such a relationship and resonate anti-minority sentiment of (extreme-right and popular nationalist) political sources in the news. Likewise, when considering representations of minorities, the significance of viewpoints of newspaper owners and editors, as well as the preferences of news consumers s should not be underestimated (Hall Citation1997; Bleich, Bloemraad, and de Graauw Citation2015). On the other hand, repeated exposure to these biased representations likely contribute to sexual threat perceptions and stereotypical beliefs regarding these groups. A vast body of evidence documents the detrimental effects of exposure to biased news representations for outgroup attitudes and intergroup relations (e.g., Mastro et al. Citation2009; Weisbuch, Pauker, and Ambaday Citation2009). Arguably, continued exposure to such images increases the accessibility and availability of stereotype-congruent associations in individuals’ memory (Arendt Citation2010). This, in turn, might contribute to the ease with which individuals associate ethnic minorities with sexual threat on an implicit level, and reinforce the idea that outgroup men are more sexually dangerous to ingroup women than ingroup men (Nagel Citation2004; Navarrete et al. Citation2010).

One may wonder why sexual threat associations became more pronounced for Arabic names (relative to Dutch names) over time, while bias did not amplify for outgroup nationalities and labels. This seems to suggest that for explicitly mentioned outgroup members, in terms of nationalities and labels, news coverage did not become more biased across time. However, we did find an increase for references to Arabic first names. Negative associations tied to “foreign” names—rather than nationalities—seems to signify an even more subtle, hidden form of bias. An increase in such subtle biases overtime ties in with the premises of what has been labeled “aversive” racism: Over the past decades, overtly expressed forms of racial prejudice have decreased, or—rather—evolved into more implicit, covert, and “aversive” forms of racism (Dovidio and Gaertner Citation2000; Gaertner and Dovidio Citation2005). With this, subtle and implicit forms of bias have become arguably more powerful and explanatory when studying mediated content (Mastro, Behm-Morawitz, and Kopacz Citation2008; Jackson Citation2019). In line with this notion, the reported findings suggest that highly implicit—and potentially unconscious—forms of racism have found their way into mediated content.

Methodologically, this study is among the first to use word embeddings in order to investigate bias in (traditional) journalistic content. The findings illustrate that this method has much potential regarding the identification of biases in large-scale datasets of news content. As these biases are partially implicit, embeddings might help researchers uncover hidden forms of bias. The repeated use of stereotypical attributes analogous to and interchangeable with references to outgroup members uncovers problematic bias in journalistic messages about ethnic outgroups. As word embeddings help to identify such forms of bias, they represent an interesting tool for media scholars to study bias across sources, outlets, and time periods.

The limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. First, the method employed in this study represents bias in textual data at a high level of aggregation: years of coverage in multiple newspapers. As a consequence, we were only able to draw general conclusions but fail to provide a clear picture of variance in (minority) voices and alternative representations in the newspapers analyzed here. Second, and by analyzing textual data, this study failed to include images, which are, however, of great importance when studying representations of social groups. Third, the current study did not consider variation across outlets. Threat associations, however, might be higher in tabloid-style newspapers, who have been shown to frequently link “foreigners” with criminal behavior (Arendt, Steindl, and Vitouch Citation2015).

Despite these limitations, the current study has taken an important step in uncovering news bias in the coverage of sexual threat. Acknowledging and understanding these and other forms of implicit news bias is an important first step in addressing this issue, and move towards fairer representations of ethnic minorities.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Iranian was removed as this ethnicity did not occur with sufficient frequency in our training corpus.

2 Using the following search string: “(‘aanranding’ OR ‘verkrachtingen’ OR ‘groepsverkrachting’ OR ‘ontucht’ OR ‘incest’ OR ‘zedenmisdrijf’ OR ‘zedenmisdrijven’ OR ‘verkrachten’ OR ‘groepsverkrachtingen’ OR’zedendelict’ OR ‘aanrandingen’ OR’verkrachte’OR ‘verkrachtingszaak’ OR ‘verkracht’ OR ‘seksuele intimidatie’ OR ‘seksueel misbruik’ OR ‘seksueel geweld’ OR ‘handtastelijkheden’ OR ‘pedofilie’ OR ‘vrouwenhandel’ OR ‘gedwongen prostitutie’ OR ‘zedenmisdrijven’) AND (‘allochtoon’ OR ‘allochtonen’ OR ‘immigrant’ OR ‘immigranten’ OR ‘migrant’ OR ‘vluchteling’ OR ‘vluchtelingen’ OR ‘eritrea’ OR ‘syrie’ OR’somalie’ OR ‘afghanistan’ OR ‘nigeria’ OR’pakistan’ OR’senegal’ OR ‘irak’ OR ‘bangladesh’ OR ‘gambia’ OR ‘soedan’)”

References

- Aarts, K., H. A. Semetko, and H. A. Semetko. 2003. “The Civided Electorate: Media use and Political Involvement Association.” The Journal of Politics 65 (3): 759–784.

- Ahmed, S., and J. Matthes. 2017. “Media Representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: A Meta-Analysis.” International Communication Gazette 79 (3): 219–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516656305.

- Algemene Rekenkamer. 2016. Asylum Inflow in the Netherlands in 2014-2016: A Cohort of Asylum Seekers.

- Arendt, F. 2010. “Cultivation Effects of a Newspaper on Reality Estimates and Explicit and Implicit Attitudes.” Journal of Media Psychology 22 (4): 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000020.

- Arendt, F., N. Steindl, and P. Vitouch. 2015. “Effects of News Stereotypes on the Perception of Facial Threat.” Journal of Media Psychology 24 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000132.

- Bakker, P., and O. Scholten. 2009. Communicatiekaart van Nederland [Communication Map of the Netherlands]. 7th ed. Amsterdam: Kluwer.

- Bennett, S., J. Ter Wal, A. Lipiński, M. Fabiszak, and M. Krzyżanowski. 2013. “The Representation of Third-Country Nationals in European News Discourse Journalistic Perceptions and Practices.” Journalism Practice 7 (3): 248–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2012.740239.

- Betz, H. G. 2013. “Mosques, Minarets, Burqas and Other Essential Threats: The Populist Right’s Campaign Against Islam in Western Europe.” In Right-wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse, edited by B. M. R. Wodak, and M. KhosraviNik, 71–88. London, England: Bloomsbury.

- Bleich, E., I. Bloemraad, and E. de Graauw. 2015. “Migrants, Minorities and the Media: Information, Representations and Participation in the Public Sphere.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (6): 857–873.

- Blommaert, L., M. Coenders, and F. van Tubergen. 2014. “Discrimination of Arabic-Named Applicants in the Netherlands: An Internet-Based Field Experiment Examining Different Phases in Online Recruitment Procedures.” Social Forces 92 (3): 957–982. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot124.

- Bolukbasi, T., K.-W. Chang, J. Zou, V. Saligrama, and A. Kalai. 2016. “Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings.” NIPS, 1–9. http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.06520.

- Caliskan, A., J. J. Bryson, and A. Narayanan. 2017. “Semantics Derived Automatically from Language Corpora Necessarily Contain Human Biases.” Science 356 (6334): 183–186.

- Chouliaraki, L., and R. Zaborowski. 2017. “Voice and Community in the 2015 Refugee Crisis: A Content Analysis of News Coverage in Eight European Countries.” International Communication Gazette 79 (6–7): 613–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048517727173.

- Croucher, S. M. 2013. “Integrated Threat TTheory and Acceptance of Immigrant Assimilation: An Analysis of Muslim Immigration in Western Europe.” Communication Monographs 80 (1): 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2012.739704.

- Czymara, C. S., and A. W. Schmidt-Catran. 2017. “Refugees Unwelcome? Changes in the Public Acceptance of Immigrants and Refugees in Germany in the Course of Europe’s ‘Immigration Crisis’.” European Sociological Review 33 (6): 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx071.

- Debrael, M., d’Haenens, L., De Cock, R., & De Coninck, D. (2019). Media use, Fear of Terrorism, and Attitudes Towards Immigrants and Refugees: Young People and Adults Compared. International Communication Gazette. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048519869476

- de Rooij, E. A., M. J. Goodwin, and M. Pickup. 2015. “Threat, Prejudice and the Impact of the Riots in England.” Social Science Research 51: 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.09.003.

- Dixon, T. L., and D. Linz. 2000. “Overrepresentation and Underrepresentation of African Americans and Latinos as Lawbreakers on Television News.” Journal of Communication 50 (2): 131–154.

- Dixon, T. L., and C. L. Williams. 2015. “The Changing Misrepresentation of Race and Crime on Network and Cable News.” Journal of Communication 65 (1): 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12133.

- Dovidio, J. F., and S. L. Gaertner. 2000. “Aversive Racism and Selection Decisions: 1989 and 1999.” Psychological Science 11 (4): 315–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12924.

- Eurostat. 2016. Record Number of Over 1.2 Million First Time Asylum Seekers Registered in 2015. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf/790eba01-381c-4163-bcd2-a54959b99ed6.

- Eurostat. 2017. Asylum in the EU Member States: 1.2 Million First Time Asylum Seekers Registered in 2016. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7921609/3-16032017-BP-EN.pdf/e5fa98bb-5d9d-4297-9168-d07c67d1c9e1.

- Friedrichs, S. 2018. Justitie eist celstraf tegen Syriër voor verkrachting meisje (12) [Justice Demands Prison Sentence Against Syrian for Rape Girl (12)]. Algemeen Dagblad.

- Fryberg, S. A., N. M. Stephens, R. Covarrubias, H. R. Markus, E. D. Carter, G. A. Laiduc, and A. J. Salido. 2012. “How the Media Frames the Immigration Debate: The Critical Role of Location and Politics.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 12 (1): 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2011.01259.x.

- Gaertner, S. L., and J. F. Dovidio. 2005. “Understanding and Addressing Contemporary Racism: From Aversive Racism to the Common Ingroup Identity Model.” Journal of Social Issues 61: 615–639.

- Garg, N., L. Schiebinger, D. Jurafsky, and J. Zou. 2018. “Word Embeddings Quantify 100 Years of Gender and Ethnic Stereotypes.” PNAS, 1–33. http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.08412.

- Goodwin, M., and C. Milazzo. 2017. “Taking Back Control? Investigating the Role of Immigration in the 2016 Vote for Brexit.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (3): 450–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117710799.

- Greenwald, A. G. 2017. “An AI Stereotype Catcher.” Science 356 (6334): 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan0649.

- Greenwald, A. G., D. E. Mcghee, and J. L. K. Schwartz. 1998. “Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition: The Implicit Association Test.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 (6): 1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-6505(89)90042-4.

- Greussing, E., and H. G. Boomgaarden. 2017. “Shifting the Refugee Narrative? An Automated Frame Analysis of Europe’s 2015 Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (11): 1749–1774.

- Grover, C., and K. Soothill. 1996. “Ethnicity, the Search for Rapists and the Press.” Ethn. Racial Stud 19: 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1996.9993925.

- Hall, S. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (Vol. 2). London: Sage.

- Harcup, T., and D. O’Neill. 2001. “What is News? Galtung and Ruge Revisited.” Journalism Studies 2 (2): 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700118449.

- Harwood, J. 2010. “The Contact Space: A Novel Framework for Intergroup Contact Research.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 29 (2): 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X09359520.

- Haynes, A., E. Devereux, and M. J. Breen. 2005. “Fear, Framing and Foreigners: The Othering of Immigrants in the Irish Print Media.” Critical Psychology 16: 100–121.

- Hox, J. J. 2005. Multilevel Analysis. Hove, East Sussex: Routledge.

- Jackson, J. M. 2019. “Black Americans and the “Crime Narrative”: Comments on the use of News Frames and Their Impacts on Public Opinion Formation.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7 (1): 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1553198.

- Jacobs, L. 2017. “Patterns of Criminal Threat in Television News Coverage of Ethnic Minorities in Flanders (2003–2013).” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (5): 809–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1217152.

- Jacobs, L., A. Damstra, M. Boukes, K. de Swert, and M. Boukes. 2018. “Back to Reality: The Complex Relationship between Patterns in Immigration News Coverage and Real-World Developments in Dutch and Flemish Newspapers (1999–2015).” Mass Communication and Society 21 (4): 473–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2018.1442479.

- Jacobs, L., M. Hooghe, and T. de Vroome. 2017. “Television and Anti-Immigrant Sentiments: the Mediating Role of Fear of Crime and Perceived Ethnic Diversity.” European Societies 19 (3): 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2017.1290264.

- Le, Q. V., and T. Mikolov. 2014. “Distributed Representations of Sentences and Documents.” ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.1145/2740908.2742760.

- Lee, J. S., and A. Nerghes. 2018. “Refugee or Migrant Crisis? Labels, Perceived Agency, and Sentiment Polarity in Online Discussions.” Social Media and Society 4 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118785638.

- Lengauer, G., F. Esser, and R. Berganza. 2011. “Negativity in Political News: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and Key Findings.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 13 (2): 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427800.

- Lesińska, M. 2014. “The European Backlash Against Immigration and Multiculturalism.” Journal of Sociology 50 (1): 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783314522189.

- Mastro, D. E., E. Behm-Morawitz, and M. A. Kopacz. 2008. “Exposure to Television Portrayals of Latinos: The Implications of Aversive Racism and Social Identity Theory.” Human Communication Research 34 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00311.x.

- Mastro, D., M. K. Lapinski, M. A. Kopacz, and E. Behm-Morawitz. 2009. “The Influence of Exposure to Depictions of Race and Crime in TV News on Viewer’s Social Judgments.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 53: 615–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150903310534.

- Matthes, J., and D. Schmuck. 2017. “The Effects of Anti-Immigrant Right-Wing Populist Ads on Implicit and Explicit Attitudes: A Moderated Mediation Model.” Communication Research 44 (4): 556–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215577859.

- Mikolov, T., K. Chen, G. Corrado, and J. Dean. 2013. “Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space.” Proceedings of ICLR Workshops Track. arxiv.org/abs/1301.3781.

- Mikolov, T., W. Yih, and G. Zweig. 2013. “Linguistic Regularities in Continuous Space Word Representations.” Proceedings of NAACL-HLT, 746–751.

- Nagel, J. 2004. “Racial, Ethnic, and National Boundaries: Sexual Intersections and Symbolic Interactions.” Symbolic Interaction 24 (2): 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2001.24.2.123.

- Navarrete, C. D., M. M. McDonald, L. E. Molina, and J. Sidanius. 2010. “Prejudice at the Nexus of Race and Gender: An Outgroup Male Target Hypothesis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98 (6): 933–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017931.

- Pruitt, L. J. 2019. “Closed Due to ‘Flooding’? UK Media Representations of Refugees and Migrants in 2015–2016 – Creating a Crisis of Borders.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 21 (2): 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148119830592.

- Said, E. 1979. Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage, 1994). Orientalism. New York: Vintage.

- Sarrasin, O., N. Fasel, E. G. T. Green, and M. Helbling. 2015. “When Sexual Threat Cues Shape Attitudes Toward Immigrants: The Role of Insecurity and Benevolent Sexism.” Frontiers in Psychology 6 (July): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01033.

- Seate, A. A., and D. Mastro. 2016. “Media’s Influence on Immigration Attitudes: An Intergroup Threat Theory Approach.” Communication Monographs 83 (2): 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1068433.

- Stephan, W. G., and C. W. Stephan. 2000. “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice.” In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, edited by S. Oskamp, 23–46. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Tewskbury.

- Stephan, W. G., O. Ybarra, and K. R. Morrison. 2009. “Intergroup Threat Theory.” In Handbook of Prejudice Stereotyping and Discrimination, 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.318

- Trussler, M., and S. Soroka. 2014. “Consumer Demand for Cynical and Negative News Frames.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 19 (3): 360–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214524832.

- The UN Refugee Agency. 2015. “World at War: UNHCR Global Trends: Forced Displacement 2014.” Geneva. http://www.unhcr.org/statistics.

- Van der Eijk, C. 2000. “The Netherlands: Media and Politics between Segmented Pluralism and Market Forces.” In Democracy an the Media: A Comparative Perspective, edited by R. Gunther, and A. Mughan, 303–342. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139175289.009.

- Van der Linden, M., and L. Jacobs. 2017. “The Impact of Cultural, Economic, and Safety Issues in Flemish Television News Coverage (2003–13) of North African Immigrants on Perceptions of Intergroup Threat.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (15): 2823–2841. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1229492.

- Van Dijk, T. A. 1991. Racism and the Press. London: Routledge.

- Vliegenthart, R., and H. G. Boomgaarden. 2007. “Real-world Indicators and the Coverage of Immigration and the Integration of Minorities in Dutch Newspapers.” European Journal of Communication 22 (3): 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323107079676.

- VluchtelingenWerk Netherland. 2016. Vluchtelingen in getallen 2016 [refugees in numbers 2016].

- Warner, K. 2004. “Gang Rape in Sydney: Crime, the Media, Politics, Race and Sentencing.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 37 (3): 344–361.

- Weisbuch, M., K. Pauker, and N. Ambaday. 2009. “The Subtle Transmission of Race Bias via Televised Nonverbal Behavior.” Science 326 (5960): 1711–1714. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1178358.