Abstract

In this article, we consider the use of statistics in financial and business journalism in the Arabian Gulf, an area which remains under-researched. In doing so, we explore how reporters in two countries – the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and United Arab Emirates (UAE) – engage with, and use, statistics and numbers to articulate business and financial news as we assess how this reflects upon professional practice. Our study is based on empirical research in these two countries, which was carried out by triangulating content analysis and semi-structured interviews with journalists. Our data suggests that, journalists tend to use valid statistics, rely on reliable statistical sources and provide a degree of interpretation of the statistical data they present. However, as we also argue, when engaging with statistics, most of these journalists seem mainly ‘to be ticking the boxes of professionalism’ rather than using them to achieve a high level of journalistic professionalism and autonomy. In other words, they aspire to follow the procedures set by the canons of professionalisation but without really exercising critical scrutiny of the subject in a way that would achieve a high level of professionalism while pushing the boundaries around them. We attribute this to external causes, such as the context in which they operate, but also to internal elements such as the lack of training.

Introduction

In a world that has witnessed the proliferation of data, journalists must have a basic understanding of statistical analysis for their work to remain relevant (Nguyen Citation2017). In fact, ensuring that journalists are able to critically engage with data and information and that the data presented to the public is accurate and free from manipulation, is a central tenet of the movement towards professionalisation of journalistic practice around the world (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015, 450). Specifically, the use of statistical data can affect the professional values of transparency and accountability that most newspapers strive to uphold. In other words, journalism as a public service should fulfil its role of bringing about transparency and providing access to information so that citizens can not only be better informed (Nielsen, Esser, and Levy Citation2013, 384) but also be more actively engaged with decision-making processes in the country.

For years, scholars have emphasised that data management skills can be just as vital for journalists today as their ability to write compelling stories (Anderson Citation2018; Borges-Rey Citation2016; Meyer Citation2002). Indeed, while professional journalism has traditionally depended on two significant forms of information -namely, textual and visual information- numerical information has also played an important role as well (Coddington Citation2015, 331).

In addition to this, and since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, business and financial journalism have increasingly become a relevant and ubiquitous source of news (Mare Citation2010). Nowadays, they are considered two of the most important journalistic news beats, given their potential in society to scrutinise the corporate world and bring about accountability into the world of the financial elites (Mare Citation2010). The 2008 crisis, and the implementation of a ruthless austerity policy in Europe that followed those events, provided a lens for scholars to investigate the role of the media in bringing accountability to the exercise of corporate power (Butterick Citation2015; Merrill Citation2015). This is not to say that business reporting has not always been a significant element within the overall news agenda and an important issue of public interest (Hayes Citation2014) but it is important to highlight how that crisis also underlined the deep flaws and shortcomings in the practice of reporting business and finance news (Schifferes and Roberts Citation2014; Schiffrin Citation2011; Starkman Citation2014a).

Discussions about this failure have mainly focused on the reasons why journalists were unable to sufficiently scrutinise the financial world (Merrill Citation2015) and on what this says about the quality of journalism itself as a political institution in society (Knowles Citation2013). Some scholars have discussed the relationship between business journalists and their news sources, highlighting journalists’ reliance on government and corporate sources and how these same sources can often control and affect the flow of information (Manning Citation2013; Schifferes and Coulter Citation2012; Starkman Citation2014b; Tambini Citation2010a). That said, researchers have also clarified that journalists’ shortcomings were very present prior to the financial crisis due to inadequate training, time pressures and misunderstanding the complexities of business markets (Butterick Citation2015; Douai and Wu Citation2014).

Nevertheless, it has only been in the post-financial crisis era that we have come to fully realise the problematic nature of business journalism practice (Merrill Citation2015) and how little we really knew about it. This gap in the body of research is even more pronounced as it has mostly concentrated on the Western media while very little attention has been paid to the way reporters cover that beat and other financial and business issues in the Global South.

Indeed, one of these neglected regional areas of research is in the Arab world, about which we know next to nothing regarding journalistic practices in the business and financial news beats. Moreover, we lack a contextualised and well-grounded explanatory theoretical framework that can help us elucidate how business journalists can fulfil normative aspirational and deontological expectations in these countries. By this we mean that there is not a sufficient theoretical work that is able to provide an explanation about how business journalism operates in the Arab world in the context of particular political and media systems. For example, most of the authors who have studied business journalism in the Arab world have concentrated on identifying the types of sources that are most often used (e.g. AlHroub Citation2012, 86; Babaker Citation2014, 190; Younis and AlNaimi Citation2006, 75), or focused on the influence of advertisements on newspapers in general (e.g. Aljumaiahe Citation2010, 182) and on business and economic journalism in particular (e.g. AlHroub Citation2012, 98; AlHumood Citation2014, 9; Kirat Citation2016, 9–11; Younis and AlNaimi Citation2006, 92). However, there is almost nothing about the use of statistical data in business journalism in the Arab world.

After all, financial and business journalists in these countries operate within a certain context (e.g., cultural, political and religious) that can affect the media system in which they are based (Mellor Citation2011; Rugh Citation2004, Citation2007; Sakr Citation2003, Citation2007). The absence of a proper body of research in this particular field is even more striking as the region holds some of the most important economic resources of the world, while hosting some of the key financial centres and stock markets on the planet. Certainly, the Arab region generates relevant and recurrent news stories on issues around investment wealth funds and the oil and gas industries to name but some, while exhibiting ample purchasing power in areas such as: defence, high-tech and general goods (Hanieh Citation2016; Kubursi Citation2015).

Despite these gaps in our understanding around business and financial journalism in the Arabian Gulf, there are some aspects that we do know. For example, we can argue that failures of news reporting in business and finance news adhere, to some degree, to similar reasons to those that might also affect news-gathering and production in the West. These include a lack of training and specialisation in the field of business and finance as well as being too close to -or at times even colluding- with their news sources (Alheezan Citation2010; AlHroub Citation2012; Babaker Citation2014).

Hence, this study wants to expand into this area and shed light on aspects and issues that remain under-researched. One of these areas relates to the ways in which journalists use statistics to articulate their business news stories in the Arabian Gulf; particularly, in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). We use statistics as they are often considered a politically neutral element in the news narrative; something that we can, of course, dispute. However, in our view, by exploring these issues, we also have the opportunity to better understand other related journalism practices in those countries. For instance, in the case of the collapse of Enron in 2001, business journalists were criticised for not critically examining and exposing the company’s annual report, even though it included warning signs of the impending crisis (Doyle Citation2006, 433). Therefore, the inability of journalists to process statistics and avoid errors may limit the accuracy of their news stories (Maier Citation2003, 930). In this sense, the use or misuse of statistics affects both accuracy and accountability. We hope that our suggestions and conclusions can provide new insights and understandings that might improve the use of statistical data among journalists in the region and more generally help move forward much-needed reform in the entire field of news reporting in the region, despite the obvious challenges and obstacles.

Methodology

Our research triangulates content analysis of Arab-speaking newspapers and semi-structured interviews with Arab journalists. The first stage included a quantitative content analysis to examine and assess the use/misuse of statistics by journalists and editors so as to explore issues around validity, reliability and interpretation, which constitute the most influential factors that affect journalists’ and editors’ ability to effectively use statistics in their news stories (Cushion, Lewis, and Callaghan Citation2017; Lugo-Ocando and Faria Brandão Citation2016). As such, the current study identifies journalists’ use of statistics as “good” or “poor” based on the factors of validity, reliability and interpretation. In this sense, we refer to ‘validity’ being audited for its assumptions. In other words, statistical validity is measured by whether (or not) statistics are used in a news story to measure what they are supposed to measure (for example, using average house prices to indicate the state of the housing market).

The other aspect that we audited was that of ‘reliability’, which addresses the veracity of statistical sources. It is perhaps worth mentioning at this point that in science, “reliability”, refers to the “reproducibility of results” (Kaye and Freedman Citation2000, 341). Kaye and Freedman (Citation2000, 407) stated that “reliability” means “the extent to which a measuring instrument gives the same results on repeated measurement of the same thing”. However, using this meaning, reliability is difficult to re-check in practice (Moore and Notz Citation2009, 157). Therefore, given that the sole purpose of this study is to identify how statistics are used in business journalism in the Arabian Gulf, the focus of this study will be on the use /misuse of statistics by journalists rather than on re-checking the statistician’s ability.

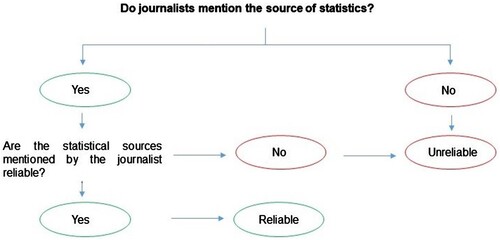

The reliability of statistical sources is evaluated as illustrated in . The first question that has been asked is whether the source of the statistics being reported is mentioned. If the answer is “yes”, we determine whether or not the source itself is reliable using the criteria outlined in the following paragraph. If the source is reliable, the statistics are said to have a high degree of reliability as well. If the source is not reliable, the statistics are deemed to lack reliability. If the source of the statistics is not mentioned, Carlson’s (Citation2011, 38–39) a suggestion is followed, which emphasises that unattributed sources negatively affect the reliability of the content. Moreover, Carlson added that it is more difficult and complicated to examine unnamed sources. Therefore, statistics reported without a source are classified as an improper or misuse of statistics, resulting in a low degree of reliability.

In order to examine the reliability of sources of statistics, prior to conducting any fieldwork, we created a list of potential reliable sources. For example, some companies’ regulations require that they publish their annual operational and financial reports in daily newspapers, and the reports need to be revised and certified by an external auditor (Ramady Citation2012, 1495); the Ministry of Justice in Saudi Arabia provides key performance indicators for real estate (Ministry of Justice Citation2016); and many organisations, such as the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), provide statistics related to oil. These types of sources are classified as “reliable”.

Finally, we audited the variable ‘interpretation’, which refers to whether journalists’ ability to analyse statistical data allows her/him to provide proper critical reflexion and clarity/transparency to the data. To measure this criterion, this research follows the methodology of Cushion, Lewis, and Callaghan (Citation2017), who explored the relationship between journalism and statistics. They examined journalistic interpretation by establishing three categories. As such, in this study, it was first asked whether the statistics provided in the news story were interpreted or not. A lack of interpretation is defined by the presence of only “vague or passing reference to statistical information” (Cushion, Lewis, and Callaghan Citation2017, 1204). Second, if it was concluded that the statistics were interpreted, it was asked whether the interpretation of statistics provided proper clarity and details—or, in other words, “a clear reference with some context provided” (Cushion, Lewis, and Callaghan Citation2017, 1205). If this was not provided, meaning the statistics’ interpretation did not provide proper clarity or details, and only “a clear reference but with little or limited context” (Cushion, Lewis, and Callaghan Citation2017, 1205) was given, then this was also classified as an improper interpretation.

We covered the period August 2008 to October 2008, which was defined by the global financial crisis, and included: the housing market, stock market, banking sector and oil price. Part of the reason for undertaking a historical approach, in this case examining the 2008 financial crisis, was that it was a turning point in the newsbeat whilst at the same time providing elements of hindsight and memory among the journalists we interviewed afterwards. It also placed some distance between these events and current individuals, which we considered appropriate given the specific context of our study and the ability of some sources to speak more freely and reflectively about the events and their own practice.

As part of the research we collected 1,321 articles from four printed newspapers (see ). Alriyadh and Alittihad, which are local newspapers, having the highest circulation in their country, and Asharq Al-Awsat, which is a pan-Arab newspaper, with the highest circulation of any pan-Arab newspaper (Rugh Citation2004, 61; 173). Aleqtisadiah is the only daily newspaper with an exclusive focus on economics and business news and analysis in Saudi Arabia (and in the Arabian Gulf), covering domestic, regional and international economic and business-related events.

Table 1. Frequency of business articles containing statistics.

We had planned to include the newspaper AlRayah, from Qatar, in this study, and we completed all the procedures required by the newspaper to start collecting the data. However, we could not complete data collection after the diplomatic crisis that occurred within the GCC in June 2017. Consequently, we excluded the Qatari newspaper from the study (we expect now to expand this study and include in a future update this publication). We should also mention that there are no official statistical figures that relate to the circulation of newspapers in most Arabian Gulf countries (Alzahrani Citation2016, 18).

It is worth mentioning that at the time of data collection, the only way to access business articles published by the newspapers included in our study was from their archives, as electronic database such as LexisNexis do not include all these newspapers. As such, the archives of these newspapers were accessed directly in sitio and a manual search conducted thereafter. Moreover, a selection of appropriate keywords was performed (see Appendix 2).

Regarding the scope of this research, which aims to understand how journalists use statistical data to articulate business news in the Arabian Gulf, the selection of articles relied on two criteria. First, the article needed to contain statistical data, so all business articles that did not contain statistical data were excluded. Second, the article needed to be produced by the newspaper itself, so any article produced by a foreign institution, such as national or international agencies or wires, were excluded.

In total, 2,259 articles were collected; however, only 44 articles (1.9%) did not contain statistics, which gave a strong indication of the overwhelming use of statistical data in business news stories. Moreover, 894 articles (40.4%) were not produced by the newspaper itself, which gave an indication of the newspapers’ dependence on business news stories coming from foreign institutions. Consequently, the sample for the content analysis in this research consisted of 1,321 business articles that contained statistics and were produced by the newspapers themselves.

For the sake of reliability, all the data from the content analysis were rated by two coders (namely, the main author and a PhD student who was trained to do so) and reliability of intercoder was computed yielding a Krippendorff’s Alpha (Kalpha) score ranging from 0.79 to 1.00 (see supplementary information).

The second stage of the research included semi-structured interviews with journalists and editors and the identification of the various approaches they use when incorporating statistics into their financial news reporting. For this reason, 14 journalists and editors who cover business news on a daily basis in Saudi Arabia and the UAE were identified for inclusion in the interview section of this research (see Appendix 1). Each interview with journalists and editors lasted between 40 minutes to 1.15 hours and discussion was mainly about their opinion on: how they see the importance of statistics in business journalism; how do media schools prepare journalism students to deal with statistical data?; how do they access statistical data?; what are the challenges they face when accessing these data?; and why do they over rely on statistical sources?

It is worth mentioning that these interviews were conducted in 2018 with journalists from the same sample newspapers who participated in covering the chosen topics during the period identified for study. Furthermore, the journalists’ interviews authored more than the half of the business news articles (51.7%) analysed in the content analysis. Through conducting these interviews, besides answering the main research question of this study, it was also possible to explore the changes in journalistic practices in the use of statistics in that region.

These issues have been examined by triangulating content analysis and interviews with journalists following the work of Mellado (Citation2020) in her own research project that looks at journalistic role and performance project, which generally speaking investigates what journalists say against what they do. Mellado has conducted a series of systematic works in the project of the role in performance of journalism, in which she and others have triangulated content analysis and semi-structured interviews, in which they compare what journalists say against what actually they do. In so doing, they have compared the actual output of journalist against what actually they claim (Mellado Citation2020). It is worth noting that this overall approach follows similar work undertaken by other authors in the field (Appelgren and Nygren Citation2014; Cushion, Lewis, and Callaghan Citation2017; Lugo-Ocando and Faria Brandão Citation2016; McCombs and Ghanem Citation2001) who have explored journalistic practices around the use of statistics to create news.

The variables used in this study in this paper include,

Sources: The news reporting process, through which journalists identify and select business news stories for coverage, starts with the selection of information sources (Dunwoody and Griffin Citation2013, 530). This selection is especially important at the information-gathering stage of the journalism process because it can help determine the extent to which a business news article is reliable and objective (Lewis Citation2010, p. 163) while helping journalists avoid critiques (Tuchman Citation1972, p. 667). One of the key normative claims in journalism during this process is that of balance, and in this sense, the use of more than one source to report news is an essential value of the trade. Organisations such as CNN, BBC and the Associated Press (AP) make it mandatory that their reporters use at least two different sources for each story in order to fulfil this normative claim.

Timeliness: This variable refers to the time period in which journalists and editors make use of business statistical reports. Business reports are usually issued publicly by official sources in the form of periodicals, and reporters may use these immediately or in a particular time period after that. In business journalism, which often relies on new information daily, timeliness plays a crucial role in delivering news in this beat (Doyle Citation2006; Knowles Citation2013; Manning Citation2013). In this sense, the timeliness variable was evaluated in terms of the time that passed between the statistical data being released and the publishing of the news story.

Validity: Using accurate data in news stories is considered one of the most important dimensions of high-quality journalism (e.g. Bogart Citation2004; Kim and Meyer Citation2005; Rosenstiel and Mitchell Citation2003). Generally speaking, for any data to be accurate, it must also be valid (Nguyen and Lugo-Ocando Citation2016, p. 6). In contrast, data that lack validity in the context of news stories distort news content (Snyder and Kelly Citation1977) and its quality (Barranco and Wisler Citation1999).

Reliability: The second criterion for assessing the use, or misuse, of statistics by journalists to articulate their business news in the Arabian Gulf is the reliability of the statistical sources. This criterion means that the statistics were produced, assessed and provided by news sources that are both credible and legitimate. As discussed in methodology section, a number of standards were relied upon in the examination of the reliability of statistical sources, such as who produced the statistical data and the source’s relationship to these data. Indeed, news sources have a strong influence on news content reliability (Carlson Citation2011). As such, it is necessary to ask whether the source of statistics in an article is reliable.

Interpretation: As one of their duties, journalists should provide interpretation of the data included in their stories for their audience (Cushion et al. Citation2017; Rafter Citation2014); this is particularly true in business coverage, “with its complexities and obscure language” (Schifferes and Coulter Citation2012, p. 20), which make it difficult for general audiences to understand. Meanwhile, journalists should also have the ability to interpret statistical data in isolation from their sources to ensure the sources do not provide an interpretation that serves their own agendas (Schiffrin Citation2011), as this could result in an unbalanced interpretation of data that distorts the news content (Snyder and Kelly Citation1977). Providing a proper explanation of data is considered a long-standing normative goal for reporters when articulating statistics (Meyer Citation1973), and it is important to understand how journalists interpret business statistical data.

Quantitative Results

The broad suggestion we can draw from the findings is that journalists of these Arab countries engage with, and use, statistics to report business news in ways that would resemble, to some extent, that of their counterparts in the West. In so doing, they follow similar aesthetics and genres that aim -at least in theory- at offering factually based and balanced accounts of the issues being covered. In fact, the inherent professional limitations in relation to the ability to report business and financial news are similar to those in the West. Corporate ownership of media outlets and dependency on government and private advertising are central to their sustainability both in the case of Arab countries and the West.

Having said that, there are also distinctive complexities and contextual elements that differ from their US and European counterparts. Particularly, around constraints and limitations in relation to news-gathering techniques, engagement and analysis, which are reflected in the quality of the end-product. News outlets in the Arab countries tend to be linked to the central government, the private corporations that own the private media are linked to these governments and journalists working in the Arab newsroom are generally subject to the discretional application of the law, which fosters self-censorship. Hence, if well Arab and Western journalists face similar challenges the limitations to overcome these same challenges are very different.

One example, of common issues faced by Arab and Western journalists when it comes to incorporating statistics in the business news beat is the limitations refers to scrutiny of news sources by not being able to access more than one source to report the news. Our analysis of journalists’ outputs in these two countries shows that the majority of the business articles studied (78.3%) relied on only one source alone, as we can see in :

Table 2. How many statistical sources are cited in each article?

These findings are similar to those found by scholars in the West, where business and financial journalists also fail to provide a more diverse set of sources in the business and financial world (Butterick Citation2015; Picard, Selva, and Bironzo Citation2014; Starkman Citation2014b). This illustrates how despite the liberal context in the West and the unliberal context in Arab countries, journlists in both places tend to produce content that presents similar problems (the use of only one sources).

Equally elucidating are the findings that highlight that government and corporate sources dominate the voices in the financial Arab news (as it is the case of their Western counterparts). However, a key difference is that in the case of Arab journalists more than three-fifths of the financial news stories (63.3 per cent) rely on governmental sources to articulate their news and just over one-fifth (23.5%) rely on private organisations (see below). We suggest that this reflects the deep and blur relation between private and government ownership both in the business and media world in those countries.

Overall, these findings are important as over-relying on official source often leads to a lack of accountability, transparency and balance, particularly as journalists lack a financial or business background to challenge their accounts (Li Citation2014, p. 3).

This last is also an indication of how different Arab business and financial journalism is from other countries such as the US where the business and financial news agenda is dominated instead by the corporate voices. As Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz (Citation2011) points out, government and financial institutions are the most significant sources of data for financial journalism in the US, where they have shown sources to have presented distorted data (Stiglitz Citation2011, p. 25) or to restrict the flow of information by deciding which parts of the information they will decide to publish (Fink and Anderson Citation2015, p. 476; Raphael, Tokunaga, and Wai Citation2004, pp. 177-167).

In addition, we found strong indications that these Arab journalists work under time pressure and limited scope to assess and work on statistics (something similar to the challenges their Western counterparts face). This as more than three-fifths (66.7%) of the studied articles made use of data that was one only day old, presumably giving little time to reporters to digest and process properly (see below). This result reflects similar findings from previous studies, which make the same point in the case of journalists operating in Western countries (Doyle Citation2006; Knowles Citation2013; Knowles, Phillips, and Lidberg Citation2015; Manning Citation2013; Starkman Citation2014b; Tambini Citation2010b). This means that reporters have very little time to process and digest these numbers and therefore they have to also rely upon the press releases and statements made by those who supply the data.

Interestingly, and despite the limitations highlighted above, our audit shows that in 92% of the units of analysis, statistics used by journalists had ‘validity’ (see ). This result indicates that, in the great majority of cases in the sample -and contrary to some common assumptions-, the business journalists do indeed use the appropriate statistics to inform the public about the issue in question.

The data confirms that the use of statistics by the news reporters was rather ‘accurate’, which matches similar findings in other parts of the world (Ahmad Citation2016; Cushion et al. Citation2017; Martinisi Citation2017) that refutes the widespread notion that journalists ‘mostly get it wrong’ when it comes to reporting statistics (Martin Citation2017; Nguyen and Lugo-Ocando Citation2016).

However, in a minority of the cases, the articles did contain statistical data that lack validity in the context of the news. For instance, in one of the articles analysed, a news story was titled: “To increase Egyptian market liquidity … Stock Exchange intends to change the listing rules”. While the reporter uses valid statistical data in the text to communicate what is appropriate to the issue, the article contains a table that includes statistics that lack validity in the context of the news story. In other words, the table attached to the article, which was produced by the newspaper itself, is not coherent with the topic. This table includes statistics about the Arab financial markets, excluding Egypt, which is the specific country the article is about; as such, they cannot be considered valid statistics. This finding agrees with Maier’s (Citation2002, p. 514) study, which showed that “story–chart inconsistency” is one of the ways in which journalists misuse numbers ().

Table 3. Source types relied upon by business journalists.

Table 4. Timeliness: Time elapsed between the statistical release and the publication of the article.

Table 5. Validity: Is the usage of statistics coherent with the topic?

A similar result was observed in relation to ‘reliability’, in which approximately three-quarters (72.8%) of the business articles studied here used reliable statistical sources (see ). However, rather than assuming that this level of ‘accuracy’ signals a capacity to use them to interrogate power, our semi-structured interviews suggest that it highlights instead journalists’ tendency to defer to the ‘official’ news sources as statistics providers and, in addition, legitimate interpreters (hence, no need to interrogate either the numbers themselves or the ‘official’ version of what they mean).

Table 6. Reliability: Is the source of statistics in the article reliable?

In relation to interpretation, around three-quarters of the articles studied (73.7%) received some sort of added comments by reporters. In this sense we have equated ‘comments’ with interpretation or the type of added value that journalists incorporate into the story by providing added commentary to the numbers that offer meaning. Therefore, readers should be aware that these terms can be interchanged in this piece. This could be an indicator not just of the journalists’ engagement with statistics but also a possible sign that they not only reproduce the numbers but also try, to a certain degree, to add some sort of explanation. However, this still leaves a great chunk of statistics, in more than one-quarter (26.3%) of the news stories that were presented, without any interpretation. This finding concurs with those of Cushion et al. (Citation2017) in the UK, who found that nearly one-quarter (23.5%) of the statistical data articulated in different British broadcasting and online outlets were mentioned just in passing or were only vaguely commented on ().

Table 7. Interpretation: Are the statistics in the article interpreted?

A closer examination of whether the statistics that were interpreted achieved a sufficient level of clarity and detail was also performed. shows that approximately four-fifths of the business statistics that were interpreted (78.5%) were given proper clarity and detail, while around one-fifth of the statistics interpreted (21.5%) were provided with only little or limited context. These findings contrast sharply with those of Cushion et al. (Citation2017) in Britain, who found that around one-third (35.2%) of statistical data articulated in different UK broadcasting and online outlets provided some context and rich detail relating to the statistics, while approximately two-fifths (41.3%) of the statistical data provided only limited or little context.

Table 8. Level of interpretation provided.

Having said that, there is no evidence that ‘interpretation’ means that business reporters in these Arab countries questioned their sources regarding the statistical data provided nor that there was any type of verification in more than four-fifths (83%) of the articles. This finding agrees with those of Alheezan (Citation2010, p. 198) who showed that journalists in the region do not tend to verify or question their data.

Just to be clear, by criticality it is meant the ability of journalists to understand and critically assess numbers while also being able to question them. In our research, we split ‘criticality’ into three categories (fallowing other research approaches in this field): factual, practical and scholarly criticism (Richards Citation2017). The first type is often refer to factual criticism and in our case relates to the ability of news reporters to question the information because of inconsistency with the known experience related to it (Collett Citation1989). For example, when governments publish statistics about unemployment reduction that are widely against the common sense on the ground (it happened under Margaret Thatcher in the UK when the British government changed the way it counted unemployment to make it appear as if economic recovery was happening). This because some facts may be affected or hidden by different interested groups including government and private sources (Doyle Citation2006; Lugo-Ocando and Faria Brandão Citation2016).

The second type, practical criticism, refers to an objection related to practical experience in the use of statistics among the public (Craig Citation1984; Feighery Citation2011). For this second type of criticism, journalists usually rely on experts to detect errors and inconsistencies (Bjerke and Fonn Citation2015). For example, the only reporters and columnists who were able to foresee the Housing Crisis and collapse of 2008, such as Jesse Colombo from Forbes magazine, were able to do so because they had practical experience in the financial sector or at least enough to be able to provide different interpretations for the data and know that the data itself was wrong at some levels.

Finally, we have scholarly criticism which refers to the ability of individual reporters to overcome self-censorship and be neutral and independent from both media owners and pressures from news sources (Klaehn Citation2003; Shirley Citation2011). Indeed, this is perhaps the most highlighted issue by authors in our field with regards to the ability of journalists to perform a watchdog function in the business and financial news beat. This includes journalists writing stories about people that own the media they work on or powerful corporations that provide advertisement to these same media.

By identifying the type of criticism used by journalists helped in differentiating and assessing the ways in which statistical data were used and interpreted in the business articles reviewed. This categorisation of criticism also elucidates where are the key issues to address and also see the commonalities and differences among different media outlets and journalists on the ground ().

Table 9. Verification: Is there any mention of missing data/partial statistics?

As can be seen in , the most common type of criticism used in business articles is practical criticism, being found in 228 articles (or 72.6% of all articles containing criticism). This finding suggests that the majority of the criticism of statistical data in business articles relies too heavily on foreign experts, who might not be impartial. The risk associated with this issue might be equal to that of an over-reliance on one type of source for the statistical data in a story (Dyck and Zingales Citation2003; Lashmar Citation2011). According to Jonathan Weil of The Wall Street Journal, “financial journalists outsourced their critical thinking skills to Wall Street analysts, who are not independent and, by definition, were employed to do nothing but spin positive company news in order to sell stock. There was hardly a Wall Street analyst covering the stock whose firm was not getting sprinkled with cash in some form or another by Enron” (Dyck and Zingales Citation2003, p. 10).

Table 10. If criticism appeared, what type of criticism was employed?

It is equally important to point out that this lack of ‘critical engagement’ with business news stories and the numbers they contain is widespread, both in terms of government and the private sector (although the government tends to receive a bit more scrutiny). This is an interesting contrast to the Western media where government received disproportionately far more criticism than the private sector ().

Table 11. Cross-tabulation of type of source referenced and whether the source was criticised.

The findings of the current study support expectation in the region set by Rugh (Citation2004, p. 65), who argued that the newspapers in the Arabian Gulf display little diversity of opinion on significant issues or provide enough criticality towards the official and corporate sources.

Causes and Reasons

Overall, the results of our interviews with 14 journalists in both countries can be summarised in three main findings: (1) Journalists seem aware of the importance of statistics for the production of news stories and for the public, although there is a gap between what they understand and how they use statistics in their articles. It seems that other factors affect their use of statistics in practice; (2) Journalists’ educational background and shortcomings in the statistical training they receive are influential factors that might hinder journalists in their use of statistics, negatively influencing the news production cycle; and, (3) When journalists struggle to access statistical reports, it can prevent them from delivering news in a timely fashion.

Overall, there is broad agreement in terms of the way the journalists perceive and engage with business statistics as most of the other respondents do think that statistics are essential for business reporting. One of the participants argued that,

From my point of view, reports and economic analyses should contain statistics and figures to provide the information in an integrated manner. … [O]f course there cannot be any understanding or analysing of economic indicators without the numbers (#INT03).

Our analysis also indicates that the majority of journalists see numbers as a central element in providing information to their readers and the actors involved, as #INT05 mentioned: “without statistics we could not build news that would benefit the reader or the decision-makers”. In fact, there is agreement between the vast majority of the interviewees that business statistics generally offer the public the information they need to make better decisions. According to #INT06, “these statistics reflect the reality of the financial and economic sector, which is desirable to enable decisions to be made from the data”.

Most of the interviewees agreed that their local universities were ill-prepared in this area and that students of journalism and media did not received adequate preparation and study. As two of the subjects indicate,

To the best of my knowledge, Saudi universities have not yet provided any link between statistics and the economic press in their curricula. However, there are individual efforts and personal judgments from some bodies such as foreign media institutions or local institutes #INT01.

There are many theories that speak about this aspect. Are we supposed to employ media graduates in the economic press after giving them an economics course or economics graduates in the economic press after giving them a media course? Local and international experiences combine both. But from my point of view, the person working in the economic press is one who is capable of developing themselves to understand the economics and to be able to read economic figures and reports. Saudi universities are a long way off from reading the economic scene. (#INT03)

This view coincides with the results of a number of studies, which have found that schools teaching students media and journalism in the Arab world concentrate on theoretical aspects and do not necessarily prepare them for the real world; these studies further warn that students are ill-prepared to perform well as a part of the media’s labour sector when they graduate (El-Nawawy Citation2007; Saleh Citation2011; Tahat, Self, and Tahat Citation2017). Moreover, this finding supports the conclusion of Alaqil and Lugo-Ocando (Citation2019) study, which underlines these educational gaps by exploring the education of statistics in Saudi journalism schools (Alaqil and Lugo-Ocando Citation2019). This last point has brought some editors to question if they should hire journalism graduates at all when it comes to covering business and finance. As the interviewees point out,

Media students often only focus on general journalism rather than on learning financial and economic news. You need a good economic and financial background to work in the press and media in the financial and economic sectors #INT11.

Based on my experience, I found the first newspaper where I worked depended on economic, finance and management graduates, and their experience was largely based on their academic record and the number of accounting and financial courses they completed. It is difficult to find a student specialised in media and train them on statistics, economics and finance to work in a newspaper specialising in money and economics, whereas it is easier to train graduates of economics and finance and accounting and statistics on the editing of media. From my point of view, I think the university has many shortcomings, starting with how to read ratios to how to deal with the Excel programme. (#INT02)

These findings suggest that there is an important gap between what the media industry expects and claims to need from new graduates and the knowledge and skills on offer. This is not a problem exclusive to these countries, or even to the Arab world in general. It is, in fact, a general problem around the world (Deuze Citation2006; Nguyen and Lugo-Ocando Citation2016; Reese and Cohen Citation2000).

In relation to accessing business statistics, most of the interviewees highlighted the difficulties and challenges they face. The vast majority of journalists do believe that it is very difficult, or problematic to some extent, to access local business statistics. However, they see some improvement since the 2008 financial crisis. According to #INT01,

In that time [2008], there was difficulty in reaching some figures for reasons of bureaucracy or mismanagement; however, it has improved now. For example, the make-up of the Statistics Authority changed from one type of organisation to another, and as a result of that change, the new organisation started issuing more statistics than the old one did. … I imagine that if anyone is looking for statistics in any field now, he will find it, but the journalist has to do more.

In the Middle East, it is difficult to get information for many reasons such as bureaucratic regulations and laws, irrespective of whether the source was governmental or private (#INT13).

Statistics were sometimes not available. For example, sometimes we contacted the government agency and it took a month to get the statistics. On other occasions, we got old statistics or received only half of the information needed. (#INT05)

Unfortunately, … the government sectors are the only that can be trusted, in the sense that they are figures issued by official bodies. As for statistics from research centres, I do not trust them because of many previous experiences. This is based on personal experience. Many of these reports are not 100% accurate, and some may simply be feasibility studies prepared for specific parties and may help one party or the other and therefore I cannot trust it. As for the financial statements of companies in the private sector, they are audited under the umbrella of the Capital Market Authority, so the figures cannot be manipulated; therefore, we can trust them. However, in respect of figures published by some research centres, I currently do not rely heavily on them, to protect our credibility for our readers. … Here, I am talking about the local studies and research centres in Saudi Arabia, but globally, when there is a study published by Bloomberg, for example, I will certainly trust it. (#INT03)

I believe that verifying the credibility of statistics is very difficult, so it is preferable to rely on official bodies to get those statistics, and to act with caution. (#INT12)

Statistics issued by official bodies are accepted as being reliable, and there is no way to verify them. (#INT11)

However, a considerable amount of literature has been published on the need to quote from more than one source in journalism (Davis Citation2007; Doyle Citation2006; Manning Citation2013; Stiglitz Citation2011). Schiffrin (Citation2011, p. 14) argued that there are two potential problems when business journalists over-rely on sources: “the risk of being given incorrect information” and “the risk of becoming dependent on access to sources”. She suggested that such sources usually have particular agendas to fulfil. They want to benefit from being journalistic sources so that they can deliver their own points of view. Moreover, Picard et al. (Citation2014, p. 13) emphasised that the dependence on only one kind of source — such as governments or private organisations- without scrutinising and questioning what they say may result in the source’s agenda being carried out. Furthermore, Davis (Citation2007, pp. 162-163) argued that when journalists rely on only one source, there will be a lack of complete information and diversity, and a possible presence of bias in the news content.

Moreover, Aljumaiahe (Citation2010, pp. 182-183) found that in Saudi Arabia, relying on sources can influence journalists in different ways. For example, sources may contact certain journalists while avoiding others. Sources may also block information, concentrate on secondary issues or give only specific information that leads to the fulfilment of certain goals (i.e., that have a positive impact on their institutions). Moreover, Younis and AlNaimi (Citation2006, p. 93) found that official sources in the UAE may block some information or omit some news. Indeed, this over-reliance on sources might be reflected in the quality of the news, particularly when journalists only depend on official sources (Choi Citation2009, p. 527).

Conclusion

It is important to bear in mind that numbers play a vital role in representing an important aspect of an economic reality (Espindosa and Alarcon Citation2016), which is also confirmed by the current research. However, there is a gap between how journalists see statistics’ importance in business news and how they utilise them during the data manipulation process(the way journalists gather, engage and interpret the numbers in the news story), which is influenced by the use of statistical data in this newsbeat. In other words, there is a gap between what journalists think they do and what actually they do. This is very important because these numbers should be there to allow bringing about transparency and accountability to business and corporate issues in the Arab world

Indeed, this gap raises concerns about business journalists’ ability to describe the role of statistical data in business news. Therefore, there is reasonable doubt related to how journalists use statistical data to write their business news stories. It seems that other important factors might affect the final product of journalists’ business news stories to a greater degree, such as their level of education and training and the accessibility of data.

The overall data reveals that journalists tend to use valid statistics, rely on reliable statistical sources and to provide an interpretation of the statistical data they present. However, engaging with the statistics is the task in which journalists seem mainly ‘to be ticking the boxes of professionalism’. In other words, they aspire to follow the procedures set by the canons of professionalisation but without really exercising critical scrutiny of the subject in a way that would achieve a high level of professionalism.

The evidence underpins the initial assumption that there is a lack of critical engagement with business and financial statistics in ways that is incompatible with normative aspirations around professionalisation and standards. However, the over-dependency on particular news sources (e.g. 78.3% of the articles analysed rely on only one source) and the lack of criticality (e.g. only 17% of the articles analysed or verified and only 23.8% criticised) can only but serve to highlight the tremendous difficulties that these journalists face in the particular context in which they operate.

Hence, it is rather an expression of, and not a cause of, the problem. In this sense, our results echo those of other scholars (Mellor Citation2005, Citation2007; Rugh Citation2004; Sakr Citation2007, p. 18) who have also argued that it is difficult for journalists in the Arab world to practise their role as watchdog under their particular contexts (political and media systems). Nevertheless, these results also suggest that the reasons for the lack of fulfilment in terms of shared normative professional expectations in the case of business journalism also respond to similar challenges faced by their counterparts in the West. Particularly around the lack of capabilities -and at times lack of willingness- to engage with statistics due to the lack of professional training and specialisation.

Most business journalists have never done any statistical training, both in the Arab world and the West. This core finding is of concern because the literature related to business journalism has for years suggested that journalists should be given adequate training in how to use numerical data and how to present it to the public in an effective manner (Brand Citation2008; Knowles et al. Citation2015; Tambini Citation2010b). To make this point clear, the quantitative findings of this study illustrate that the majority of the articles analysed relied heavily on single sources (78.3%) and only around one-quarter of the articles contained elements that one could assess as ‘critical, ‘interpretative’ or even ‘analytical’. This shortcomings in their statistical training leads journalists fail in their ability to use data to bring accountability and transparency to the corporate world in those countries. This a problem that both the West and the Arab news reporters have in common. According to Jonathan Weil of The Wall Street Journal:

financial journalists outsourced their critical thinking skills to Wall Street analysts, who are not independent and, by definition, were employed to do nothing but spin positive company news in order to sell stock. There was hardly a Wall Street analyst covering the stock whose firm was not getting sprinkled with cash in some form or another by Enron. (Dyck and Zingales Citation2003, p. 10)

In this sense, business and financial journalists work in a professional collective group that investigate issues using the interpretative tools provided by statistical analysis. However, limited accessibility and the ‘necessity’ to rely upon particular news sources given the context in which they operate, limit their ability to explore critically the official statistical data provided. In the normative model, news editors and journalists are often expected to come to conclusions about whether to trust what official sources report. However, proper verification of statistical data seems to be very limited, particularly given the working context and a widespread lack of training to do so.

By studying the use of statistics in the articulation of financial news, we aimed at understanding levels of professionalism among journalists in the Arab Gulf. What we heard from our interviewees is an aspiration to be an ‘interpretative community’ of journalists (Zelizer Citation1993) who would want, in principle, to display efforts aiming for professional standards comparable to those of their counterparts in the West but who in most cases fall short from doing so given the limitations they face. In their defence, many of these challenges escape to their control and that of their own news organisations and will only be possible to address in time and if there are broader changes in the region (hopefully some of which already taking place despite setbacks).

Indeed, it is perhaps insincere on our part to point fingers only at journalists operating in these contexts when in fact their counterparts in the West -who enjoy remarkable freedoms, resources and legal protection offered by liberal political systems– also failed abysmally bring about accountability to their own corporative and business world. Let us not forget that their Western counterparts, with all their freedoms, also failed to report critically both the prelude to and aftermath of the 2008 world financial crisis while mostly giving a free pass to the impunity with which bankers were treated while governments went on to apply a draconian set of austerity policies that destroyed so many lives in Europe and the US (Harkins and Lugo-Ocando Citation2017; Lugo-Ocando Citation2014).

We need to acknowledge that journalism in the Arab world should not be just judged by the standards and practices undertaken in liberal democracies, where institutions and systems exist to protect the independence of the work of reporters. For our colleagues in the Arab world, the mountain is steeper and more difficult to climb. Hence, passing judgement towards them and their work would be far from fair, particularly in light of the context in which they have to operate. Clearly, journalism in the Arab countries has far more limitations than that practiced in the West and hence comparisons need to be done carefully. Nevertheless, it is also true that when it comes to dealing with statistical data, Arab journalists face similar challenges and problems as their counterparts in the West. Particularly, regarding the news media’s ability to challenge the wrongdoings of the corporate and financial world. These common problems also have common solutions and delivering more and better education and training in numbers is perhaps one aspect in which we can all actually intervene to makes things better. Let us then address, act and work in those areas where it is possible to improve journalism as a whole.

Supplementary_Material

Download Zip (92.8 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmad, M. I. 2016. “The magical realism of body counts: How media credulity and flawed statistics sustain a controversial policy.” Journalism 17 (1): 18–34.

- Alaqil, F., and J. Lugo-Ocando. 2019. “Challenges and opportunities for teaching data and statistics within journalism education in Saudi Arabia: fostering new capabilities in the region.” Journalism Education 8 (2): 55–66.

- Alheezan, M. 2010. “The degree of dependence of the Saudi stock market investors on media.” Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 14: 193–230.

- AlHroub, M. 2012. “Handling the economic issues by Saudi daily press.” (Master). Middle East University, Jordan.

- AlHumood, A. 2014. Media message in light of the current economic variables in the Arab world: critical approach on a proposal to support the economic function of the Arab media model. Paper presented at the The role of media in the work and overall development issues service., Cairo.

- Aljumaiahe, A. 2010. “Journalistic professional practice and the factors influencing it.” (Ph.D.). Imam Muhammad Bin Saudi Islamic University.

- Alzahrani, A. A. 2016. “Newsroom Convergence in Saudi Press organisations: A qualitative study into four newsrooms of traditional newspapers.” (Ph.D.). University of Sheffield.

- Anderson, C. W. 2018. Apostles of certainty: Data journalism and the politics of doubt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Appelgren, E., and G. Nygren. 2014. “Data Journalism in Sweden: Introducing new methods and genres of journalism into “old” organizations.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 394–405.

- Babaker, I. 2014. “The role of journalism in providing economic information.” (Ph.D.). Omdurman Islamic University.

- Barranco, J., and D. Wisler. 1999. “Validity and systematicity of newspaper data in event analysis.” European sociological review 15 (3): 301–322.

- Berkowitz, D., and J. V. TerKeurst. 1999. “Community as interpretive community: rethinking the journalist-source relationship.” Journal of Communication 49 (3): 125–136.

- Bjerke, P., and B. K. Fonn. 2015. “A Hidden Theory in Financial Crisis Journalism?” Nordicom Review 36 (2): 113–127.

- Bogart, L. 2004. “Reflections on content quality in newspapers.” Newspaper Research Journal 25 (1): 40–53.

- Borges-Rey, E. 2016. “Unravelling Data Journalism: A study of data journalism practice in British newsrooms.” Journalism Practice 10 (7): 833–843.

- Brand, R. 2008. “The numbers game: A case study of mathematical literacy at a South African newspaper.” Communication: South African Journal for Communication, Theory and Research 34 (2): 210–221.

- Butterick, K. 2015. Complacency & Collusion: A critical introduction to business and financial journalism. London: Pluto Press.

- Carlson, M. 2011. “Whither anonymity? Journalism and unnamed sources in a changing media environment.” In Journalists, sources and credibility: New perspectives, edited by B. Franklin, and M. Carlosn, 37–48. London: Routledge.

- Choi, J. 2009. “Diversity in foreign news in US newspapers before and after the invasion of Iraq.” International Communication Gazette 71 (6): 525–542.

- Coddington, M. 2015. “Clarifying journalism’s quantitative turn: a typology for evaluating data journalism, computational journalism, and computer-assisted reporting.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 331–348.

- Collett, A. 1989. “Literature, Criticism, and Factual Reporting.” Philosophy and Literature 13 (2): 282–296.

- Craig, R. T. 1984. “Practical criticism of the art of conversation: A methodological critique.” Communication Quarterly 32 (3): 178–187.

- Cushion, S., J. Lewis, and R. Callaghan. 2017. “Data journalism, impartiality and statistical claims: Towards more independent scrutiny in news reporting.” Journalism Practice 11 (10): 1198–1215.

- Davis, A. 2007. “The economic inefficiencies of market liberalization The case of financial information in the London Stock Exchange.” Global Media and Communication 3 (2): 157–178.

- Deuze, M. 2006. “Global journalism education: A conceptual approach.” Journalism Studies 7 (1): 19–34.

- Douai, A., and T. Wu. 2014. “News as business: the global financial crisis and Occupy movement in the Wall Street Journal.” Journal of International Communication 20 (2): 148–167.

- Doyle, G. 2006. “Financial news journalism A post-Enron analysis of approaches towards economic and financial news production in the UK.” Journalism 7 (4): 433–452.

- Dunwoody, S., and R. J. Griffin. 2013. “Statistical reasoning in journalism education.” Science Communication 35 (4): 528–538.

- Dyck, A., and L. Zingales. 2003. “The bubble and the media.” In Corporate governance and capital flows in a global economy, edited by P. Cornelius, and B. Kogut, 83–104. New York: Oxford University Press.

- El-Nawawy, M. 2007. “Between the Newsroom and the Classroom Education Standards and Practices for Print Journalism in Egypt and Jordan.” International Communication Gazette 69 (1): 69–90.

- Espindosa, J., and J. Alarcon. 2016. “Financial performance rankings as trading organizing devices: The case of chilean pension funds.” REVISTA ESPACIOS 37 (36): 601–635.

- Feighery, G. 2011. “Conversation and credibility: Broadening journalism criticism through public engagement.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 26 (2): 158–175.

- Fink, K., and C. W. Anderson. 2015. “Data Journalism in the United States: Beyond the “usual suspects”.” Journalism Studies 16 (4): 467–481.

- Frost, C. 2015. Journalism ethics and regulation. London: Routledge.

- Hanieh, A. 2016. Capitalism and class in the Gulf Arab states. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harkins, S., and J. Lugo-Ocando. 2017. Poor news: Media discourses of poverty in times of austerity. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hayes, K. 2014. Business Journalism: How to Report on Business and Economics: Apress.

- Kaye, D. H., and D. A. Freedman. 2000. “Reference guide on statistics.” Reference manual on scientific evidence 83: 331–414.

- Kim, K.-H., and P. Meyer. 2005. “Survey yields five factors of newspaper quality.” Newspaper Research Journal 26 (1): 6–15.

- Kirat, M. 1987. “The algerian news people: A study of their backgrounds, professional orientations and working conditions.” (Ph.D). Indiana University.

- Kirat, M. 2016. “A profile of journalists in Qatar: traits, attitudes and values.” The Journal of International Communication 22 (2): 1–17.

- Klaehn, J. 2003. “Behind the invisible curtain of scholarly criticism: revisiting the propaganda model.” Journalism Studies 4 (3): 359–369.

- Knowles, S. 2013. “Financial journalism through financial crises: The reporting of three boom and bust periods.” (Ph.D.). Murdoch University.

- Knowles, S., G. Phillips, and J. Lidberg. 2015. “Reporting the global financial crisis: A longitudinal tri-nation study of mainstream financial journalism.” Journalism Studies 18 (3): 1–19.

- Kubursi, A. 2015. Oil, Industrialization & Development in the Arab Gulf States (RLE Economy of Middle East). New York: Routledge.

- Lashmar, P. 2011. “Blonde on Blonde: WikiLeaks Versus the Official Sources.” In Investigative journalism: dead or alive?, edited by J. Mair, and R. L. Keeble, 107–121. Suffolk: Abramis Academic Publishing.

- Lewis, J. 2010. “Normal viewing will be resumed shortly: News, recession and the politics of growth.” Popular Communication 8 (3): 161–165.

- Lewis, S. C., and O. Westlund. 2015. “Big data and journalism: Epistemology, expertise, economics, and ethics.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 447–466.

- Li, C. 2014. The hidden face of the media: How financial journalists produce information.

- Lugo-Ocando, J. 2014. Blaming the victim: How global journalism fails those in poverty. London: Pluto Press.

- Lugo-Ocando, J., and R. Faria Brandão. 2016. “Stabbing News: Articulating crime statistics in the newsroom.” Journalism Practice 10 (6): 1–15.

- Maier, S. R. 2002. “Numbers in the news: A mathematics audit of a daily newspaper.” Journalism Studies 3 (4): 507–519.

- Maier, S. R. 2003. “Numeracy in the newsroom: A case study of mathematical competence and confidence.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 80 (4): 921–936.

- Manning, P. 2013. “Financial journalism, news sources and the banking crisis.” Journalism 14 (2): 173–189.

- Mare, A. 2010. “Business journalism ethics in Africa: a comparative study of newsrooms in South Africa, Kenya and Zimbabwe print media.” (Master). Rhodes University.

- Martin, J. D. 2017. “A census of statistics requirements at US journalism programs and a model for a “statistics for journalism” course.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 72 (4): 461–479.

- Martinisi, A. 2017. “Understanding Quality of Statistics in News Stories: A Theoretical Approach from the Audience's Perspective.” In Handbook of research on driving STEM learning with educational technologies, edited by R. Montoya, and M. Soledad, 485–505. Hershey: IGI Global.

- McCombs, M., and S. I. Ghanem. 2001. “The Convergence of Agenda Setting and Framing.” In Framing Public Life: Perspectives on Media and our Understanding of the Social World, edited by S. Rees, O. Gandy, and A. Grant, 67–81. New Jersey: Mahwah.

- Mellado, C. 2020. Journalistic role and performance. https://www.journalisticperformance.org.

- Mellor, N. 2005. The making of Arab news. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Mellor, N. 2007. Modern Arab journalism: problems and prospects. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Mellor, N. 2011. Arab media: Globalization and emerging media industries (Vol. 1). Cambridge: Polity.

- Merrill, G. J. 2015. “Convergence and Divergence: a study of British economic and business journalism.” (Ph.D). Goldsmiths, University of London.

- Meyer, P. 1973. Precision Journalism: A Reporter's Guide to Social Science Methods. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Meyer, P. 2002. Precision journalism: A reporter's introduction to social science methods. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Ministry of Justice. 2016. Performance indicators. https://www.moj.gov.sa/En/Ministry/Pages/BI.aspx.

- Moore, D. S., and W. Notz. 2009. Statistics: Concepts and controversies. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Nguyen, A. 2017. “Introduction: Exciting Times In the Shadow of the ‘Post-Truth’ Era: news Numbers and Public Opinion in a Data-Driven World.” In News, numbers and public opinion in a data-driven world, edited by A. Nguyen, 1–15. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Nguyen, A., and J. Lugo-Ocando. 2016. “The state of statistics in journalism and journalism education: issues and debates.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 15 (7): 3–17.

- Nielsen, R. K., F. Esser, and D. Levy. 2013. “Comparative perspectives on the changing business of journalism and its implications for democracy.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 18 (4): 383–391.

- Picard, R. G., M. Selva, and D. Bironzo. 2014. Media coverage of banking and financial news. Oxford: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Media%20Coverage%20of%20Banking%20and%20Financial%20News.pdf(letzterZugriff15.9.2014)].

- Rafter, K. 2014. “Voices in the crisis: The role of media elites in interpreting Ireland’s banking collapse.” European Journal of Communication 29 (5): 598–607.

- Ramady, M. A. 2012. The GCC economies: Stepping up to future challenges. London: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Raphael, C., L. Tokunaga, and C. Wai. 2004. “Who is the real target? Media response to controversial investigative reporting on corporations.” Journalism Studies 5 (2): 165–178.

- Reese, S. D., and J. Cohen. 2000. “Educating for journalism: The professionalism of scholarship.” Journalism Studies 1 (2): 213–227.

- Richards, I. A. 2017. Principles of literary criticism. London: Routledge.

- Rosenstiel, T., and A. Mitchell. 2003. Does Ownership Matter in Local Television News?: A Five-Year Study of Ownership and Quality. Project for Excellence in Journalism., 29. http://search.proquest.com/docview/451221377?pq-origsite=summon.

- Rugh, W. A. 2004. Arab mass media: Newspapers, radio, and television in Arab politics. London: Praeger.

- Rugh, W. A. 2007. “Do national political systems still influence Arab media.” Arab Media and Society 2: 1–21.

- Sakr, N. 2003. “Freedom of expression, accountability and development in the Arab region.” Journal of Human Development 4 (1): 29–46.

- Sakr, N. 2007. Arab television today. London: I.B Tauris.

- Saleh, I. 2011. Journalism curricula in the Arab region: a dilemma of content, context and contest. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Schifferes, S., and S. Coulter. 2012. “Downloading disaster: BBC news online coverage of the global financial crisis.” Journalism 14 (2): 228–252.

- Schifferes, S., and R. Roberts. 2014. The media and financial crises: comparative and historical perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Schiffrin, A. 2011. “The U.S. Press and the Financial Crisis.” In Bad News: How America's Business Press Missed the Story of the Century, edited by A. Schiffrin, 1–21. New York: The new Press.

- Shirley, M. M. 2011. “What should be the standards for scholarly criticism?” Journal of Institutional Economics 7 (4): 577–581.

- Snyder, D., and W. R. Kelly. 1977. “Conflict intensity, media sensitivity and the validity of newspaper data.” American Sociological Review 42 (1):105–123.

- Starkman, D. 2014a. The watchdog that didn't bark: The financial crisis and the disappearance of investigative journalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Starkman, D. 2014b. The Watchdog That Didn't Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism.: Columbia University Press.

- Stiglitz, J. E. 2011. “The Media and the Crisis: An Information Theoretic Approach.” In Bad News: How America's Business Press Missed the Story of the Century, edited by A. Schiffrin, 22–36. New York: The New Press.

- Tahat, K., C. C. Self, and Z. Y. Tahat. 2017. “An examination of curricula in Middle Eastern journalism schools in light of suggested model curricula.” Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict 21 (1): 1–23.

- Tambini, D. 2010a. “Beyond the great crash of 2008: questioning journalists’ legal and ethical frameworks.” Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics 7 (3): 2–15.

- Tambini, D. 2010b. “What are financial journalists for?” Journalism Studies 11 (2): 158–174.

- Tuchman, G. 1972. “Objectivity as strategic ritual: An examination of newsmen's notions of objectivity.” American Journal of Sociology 77 (4): 660–679.

- Usher, N. N. B. 2011. “Making business news in the digital age.” (Ph.D.). University of Southern California.

- Younis, A., and A. AlNaimi. 2006. “Economic pages in the UAE newspapers.” Social Issues 23 (90): 57–111.

- Zelizer, B. 1993. “Journalists as interpretive communities.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 10 (3): 219–237.