ABSTRACT

Journalism facilitates the public sphere, playing a key role as a social institution dedicated to informed citizenship. From a democratic perspective, a diversity of opinions and viewpoints on the mediated agenda is vital. This article analyzes the sourcing practice in Norwegian local and regional media, identifying what kind of sources are given access and who is not. With diversity and media shadows as central concepts, the research question asked is: What characterizes the sourcing practice in local and regional media, and how does this contribute to diversity in the coverage. With its characteristic geographic stratified media landscape and a large amount of local and regional media, the Norwegian context is of special interest when elaborating on the institutional role of local media, and the ideal of diversity. The article is based on a content analysis of 24 Norwegian local and regional media including print, online and broadcast.

Introduction

Using sources is in many ways at the heart of news selection and the production process (O’Neill and O’Connor Citation2008). Having a voice in the mediated public represents the power to comment, define, protest or agree, as well as the authority to view and interpret reality. Journalism's agenda-setting power involves providing or denying access to the public sphere, as journalists determine who will have a voice in the news (Broersma, den Herder, and Schohaus Citation2013, 388). Journalism facilitates the public sphere, playing a key role as a social institution dedicated to informed citizenship (Tiffen et al. Citation2014, 389). Of course, the digital media environment has weakened the agenda-setting power of news media, as citizens, politicians and other actors may express themselves through blogs and social media, independent of how newsrooms prioritize stories. Further, the routinization of the newsroom practice characterizes news work (Wheatly Citation2020). However, sourcing is still fundamentally important in journalism, as Schudson (Citation2003, 134) aptly describes: “to understand the news, we have to understand who the someones who act as sources are, and how journalists deal with them”.

From a democratic perspective, it is fundamental for the media to present a diversity of opinions and viewpoints (Mellado and Scherman Citation2020, 17), as a plurality of voices in the news is perceived as one of the key elements of democracy (Becker and Van Aelst Citation2018). Former studies indicate that local media tend to be less elite-oriented in their sourcing practice than larger, national newsrooms, and thus contribute a diversity regarding perspectives and interests represented in public debate (Sjøvaag Citation2018; Allern Citation2001; Mathisen Citation2013). While being somewhat overlooked in media research for several years (Wahl-Jorgensen and Hanitzsch Citation2009), local journalism has recently gained increased scholarly interest, as well as increased attention and recognition in public debate (Nielsen Citation2015; Hess and Waller Citation2017; Waschková Citation2017). Local media serve local democracy and public debate (Ali Citation2017; Mathisen and Morlandstø Citation2018). Local news and the local public sphere are shaped by local sources (O’Neill and O’Connor Citation2008), which make the sourcing practice of vital scholarly interest when elaborating on how local media carries out their societal role.

Regarding local media, the Norwegian media landscape is of special interest, as it is characterized by a stratified geographical pattern with a large amount of local and regional media published all over the elongated country (Høst Citation2005). A media policy with press subsidies to small local outlets and a public broadcaster with a range of district offices throughout the country also underlines the Norwegian context as interesting to study. Even if the local media in Norway experiences downsizing and revenue loss, both readership and circulation are still relatively high, as well as the willingness to pay for online news. Hence, this article will shed light upon sourcing practices, as the research question asked is: What characterizes the sourcing practice in local and regional media, and how does this contribute to diversity in the coverage? Based upon a quantitative content analysis of 24 different local and regional media outlets in Norway, the purpose is twofold: First, to identify the overall pattern regarding the number of sources and to discuss which voices, perspectives and interests that become sources. Second, to elaborate differences and similarities in sourcing practice between the different types of local media in the stratified Norwegian media landscape.

The article is organized as follows: First, I will provide an overview of the specific Norwegian media context in which this study is carried out, followed by a general elaboration of local media. Then I will turn to the study's theoretical starting point and discuss vital concepts. This will be followed by a literature review presenting former research on sourcing in journalism, before discussing data and methods. Thereafter I will present and discuss the findings. Finally, I will sum up and conclude.

The Norwegian Media Context

A characteristic feature of all the Nordic countries is the diverse press structure, which has a large number of local and regional editions (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014; Hallin and Mancini Citation2009). The Norwegian newspaper ecology includes 223 editions published in 184 different communities and cities (Høt Citation2019). The newspaper structure is denoted as an umbrella (Høst Citation2005), with several levels such as national newspapers, regional newspapers, local dailies, and local weeklies/ ultra-locals—the latter often with one or two municipalities as their coverage area. The umbrella model underlines the geographical width, with different types of newspapers covering different types of geographical regions. The Nordic countries Finland, Sweden and Norway are ranked in high terms of printed newspaper circulation per 1000 inhabitants, and Norway is ranked highest in the world with proportion to paying for online news (Linden, Morlandstø, and Nygren Citation2021, 157). Despite a media crisis resulting in cutbacks and downsizing, the local press remains of key importance—particularly in Norway and Finland (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014, 55)—and is described as the backbone of the Norwegian media structure (Høst Citation2005, 148). In addition, Norway and the other Nordic countries have strong public service broadcasting at the regional level. The national broadcaster (NRK) has 48 district or local offices, where 900 of the 3400 NRK staff are employed. Thus, the broadcast also is a vital supporter of local and regional news (Mathisen and Morlandstø Citation2018). Local media structures have remained remarkably stable despite technological and economic shifts, indicating that localism, one of the Norwegian society's deep structures, may be a characteristic of the Norwegian media structure in the foreseeable future (Skogerbø and Karlsen Citation2021, 99). Since the 1960s, Norway, as well as the other Nordic countries have developed a system with state subsidies, crucial for supporting the large number of local media companies, and in 2019, the Norwegian government even sought to increase press subsidies for local media (Linden, Morlandstø, and Nygren Citation2021, 161). The press subsidies entail both indirect subsidies as exemptions for value added tax, direct subsidies and taxes that fund the broadcast (licence fee until 2020).

Stemming from a past in which local journalism has been paid scarce scholarly attention (Wahl-Jorgensen and Hanitzsch Citation2009), recent media research has valued and discussed the societal role of local journalism and recognized its value (Ali Citation2017; Nielsen Citation2015; Hess and Waller Citation2017; Waschková Citation2017; Mathisen and Morlandstø Citation2018; Gumera, Domingo, and Williams Citation2018). Local news is regarded as a public good (Ali Citation2017, 8). This increased scholarly interest embraces a variety of aspects, such as the role of local journalism in the digital media landscape (Nielsen Citation2015; Hess and Waller Citation2017), and local media in relation to local democracy (Mathisen and Morlandstø Citation2018; Nielsen Citation2015; Svith et al. Citation2017). Further, studies focus on sourcing practices in local journalism (Mathisen Citation2013; Sjøvaag Citation2018).

Theory and Concepts

The theoretical starting point for this study is institutional theory (Allern and Blach-Ørsten Citation2011; Cook Citation1998), underlining journalism as an institutionalized practice. Journalism is an independent part of society with its own norms and structures and is assigned a role within democracy (Cook Citation1998; Sparrow Citation1999). Consequently, journalism has a specific kind of legitimacy (Allern Citation1996) and news is a product with organizational expectations (Berkowitz Citation2009). Cook (Citation1998, 70) defines institutions as “social patterns of behaviour identifiable across organizations that are generally seen within a society to preside over a particular social sphere”. Further, institutions are “the more enduring features of social life” (Giddens Citation1984, 24). According to Giddens, the structure is a set of resources, rules and institutionalized features out of time and space. Cook (Citation1998) describes journalism as a collective process, more influenced by routines and procedures than each individual journalist's decisions. Within the institution of journalism, the structure might be practiced as news values and professional norms, explaining why journalists act as they do (Ottosen Citation2004, 18)—among others, this goes for the choice of sources, as routinization often dominates the sourcing process (Wheatly Citation2020).

Institutional theory underlines journalism's societal and democratic role, as a channel and arena for public debate and communication (Allern Citation2001). This leads to the concept of diversity that describes a multiple and varied media landscape. Media diversity is conceptualized as the presence of different types of social actors, voices, and points of view in the journalistic discourse (Mellado and Scherman Citation2020, 1). The concepts of diversity and democracy are often paired. One of the pillars in the Nordic media model is the aforementioned press subsidies aimed at sustaining diversity (Syvertsen et al. Citation2014). The ideal of diversity embraces content, owners, publishers and several newsrooms as well as geography. The ideal of diversity also relates to sources, as the interface between private experience and public power is structured to the public sphere (Manning Citation2001, 5). Media diversity describes the idea that the available content should reflect the varieties of user preferences, identities and ideologies that exist in society (Sjøvaag and Kvalheim Citation2019, 296). A diversity of voices in the mediated agenda is a democratic prerequisite, as democracy requires representation, freedom of information, and access to arenas for public debate (Sjøvaag Citation2018). According to Sjøvaag, quantitative diversity also implies qualitative diversity: The more variety of voices and sources represented on the mediated agenda, the more diversity.

The lack of diversity is described with concepts such as blind spots, media shadows or news deserts, all of which deal with the lack of journalism in various situations such as geographic, thematic or social. The concept of media shadow was introduced by Nord and Nygren (Citation2002). They stated that a media shadow occurs when the reporting from a specific area is single-sided, scarce, sporadic or lacking (32). Nord and Nygren describe three kinds of media shadows: First, geographical shadows which occur when specific areas are not covered by journalists or news media. Second, media shadows might also be thematic when specific issues or topics are rarely visible on the mediated agenda. Third, media shadows might also be social: describing which parts of society, perspectives or interests are not brought into the mediated agenda. In other words, which kinds of sources are scarce or lacking in journalism? Familiar concepts to media shadows are blind spots and black holes, where citizens lack news media to fulfill their information needs and are thus in a democratic deficit (Howells Citation2015). Also, the concept of news deserts is relevant, which describe a lack of local news in a specific geographical area (Napoli et al. Citation2015), or as “a community, either rural or urban, with limited access to the sort of credible and comprehensive news and information that feeds democracy at the grassroot level” (Abernathy Citation2018 , see https://www.usnewsdeserts.com). The concepts of news desert have its root in the US, where 2100 newspapers are lost the past 15 years, leaving at least 1800 communities without any newspaper at the beginning of 2020 (Abernathy Citation2021, 9). Further in this article, I will use media shadow concept. From this theoretical starting point, I will continue with an elaboration of sources in journalism.

Sources in Journalism

Two important issues emerge in the scholarly interest of sources in journalism: One is about the power relations and interactions between journalists and their sources (Gans Citation1979; Allern Citation1996; Ericson, Baranek, and Chan Citation1989; Broersma, den Herder, and Schohaus Citation2013; Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2014). In his classical study, Gans (Citation1979, 116) describes the relationship between sources and journalists as a dance. With the tango-metaphor, he elaborates how the sources most often do the leading, while Ericson et al. (Citation1989) characterize the relation as a negotiating of control. The other issue is the patterns and characteristics of sourcing practice, often elaborated by quantitative content analyses, counting the number of sources as well as the different kinds of sources. Here, the concern is about access to the news (Carlson and Franklin Citation2011), routinization of news sourcing (Wheatly Citation2020), and further issues of bias, power, influence and representation are at the core (Berkowitz Citation2009). The power relations between journalists, sources and the sourcing patterns are intricately connected, as the sourcing patterns reflect organizational and journalistic norms encouraging repetition of practice as well as privileging powerful sources (Berkowitz Citation2009, 3).

Source selection is determined by a combination of daily production routines and professional newsroom standards (Berkowitz Citation2009; Kleemans, Schaap, and Hermans Citation2017). Choosing sources is a necessary part of the journalistic process. However, these choices impact how the content is perceived and interpreted, and influences the journalistic frames and views of reality (Allern Citation2001, 161). According to Schudson (Citation2003, 134), the news represents the authorized knowers and their version of reality. To be a news source involves presence and the power to define and respond to the world, as the range of voices allowed into news discourse shapes the public's understanding of the world (Carlson and Franklin Citation2011, 2–5).

Several former studies conclude that journalism tends to be elite-oriented: Journalists prefer routine sources and official representatives over grassroots sources. Several Norwegian studies show that journalists reflect the elite's views rather than the perceptions of ordinary citizens (Figenschau and Beyer Citation2014; Sjøvaag Citation2018; Allern Citation2001). As Carlson (Citation2009, 529) states: “In fact, the reliance on official sources and routine news channels is one of the most reproduced findings in studies of journalism”. Elite sources are described as the primary definers of public debate, and elite voices tend to marginalize the less powerful who have limited access to the public arena (Manning Citation2001). As these findings are confirmed in both older and more recent studies, they indicate a relatively constant trend that can be explained through journalism's institutional aspects.

While Kleemans, Schaap, and Hermans (Citation2017, 477–478) find the increased use of citizen sources in the news, they occur mostly as passive vox pop sources and mere illustrations. The power of citizens to define the news in a substantive manner has not increased accordingly, and elite sources remain the most dominant sources and thus primary definers in mediated public debate (according to the authors). Their study is based on Dutch TV news stories. In a study from Belgium, De Keyser and Raeymaeckers (Citation2012) find that the internet has increased the prominence of ordinary people in the news. Several Norwegian studies also conclude that local media is characteristically less elite-oriented and more diverse in their use of sources, allowing grassroots representatives access to the mediated agenda more often than the larger, national media do (Allern Citation2001; Sjøvaag Citation2018; Mathisen Citation2013).

Several explanations are identified to understand the elite-dominated sourcing practice. Authority is one, as ordinary citizens are often deemed less credible than authoritative and expert voices (Laursen and Trapp Citation2019). In the hierarchy of credibility, authoritative sources are at the top, while ordinary people and the politically marginalized are at the bottom (Manning Citation2001). Another explanation is that journalist's sourcing practice mirrors a general norm of objectivity, factuality and credibility in news reporting, as journalists seek authoritative sources to be legitimate bearers of facts while citizens tend to be used as a source of emotional or moral reaction to an event or situation (Laursen and Trapp Citation2019, 3). Laursen and Trapp (Citation2019) also discuss the distinction between expertize and advocacy. They elaborate on how expertize is a core attribute of source credibility, considered neutral in a political sense, while advocacy is often interpreted as a hindrance and believed to have vested interests. Further, the fourth estate ideal of journalism explains the elite orientation. Because journalists are holding accountable those in power, politicians and sources that have societal control must answer, and therefore dominate the mediated agenda. Thus, journalism's attraction to powerful elite sources is strengthened (Sjøvaag Citation2018, 5). Another explanation is that citizen voices often require greater journalistic effort than information from the elites, and resources that do this are not always available (Stroobant, De Dobbelaer, and Raeymaeckers Citation2018, 347).

Ordinary citizens’ representation in the news is often described as a democratic prerequisite because media organizations are expected to contribute a diversity of voices within public discourse and are seen as a counterbalance to elite sources that usually dominate the news (Peter and Zerback Citation2020; Dimitrova and Strömbäck Citation2009). Literature also discuss how citizen sources are conceptualized. Peter and Zerback (Citation2020, 1004) use the term “ordinary citizens” to describe non-professional actors who appear in the media with their private roles as representatives of the general population. Kleemans, Schaap, and Hermans (Citation2017, 471) use the term “citizen sources” to define ordinary people who appear in the news without representing an institutional organization at either the macro or meso level. In the following, I will use the concept of grassroots to define individuals as ordinary citizens speaking on behalf of themselves, and not being representative of any formal position or role.

Diversity is also affected by the number of sources. In a study of four West Yorkshire newspapers, O’Neill and O’Connor (Citation2008, 493) found that 76% of the news stories are based on a single source, which places the source in a relatively strong position to influence the subsequent framing of the articles, excluding certain views and issues relevant to the readership. Previous studies of Norwegian local news media reveal that approximately half of the news stories are single-sourced (Mathisen Citation2013; Allern Citation2001), which also indicates that local media often publish single-sourced stories more often than larger newsrooms.

Data and Methods

This article is based on a quantitative content analysis of 24 different local and regional media outlets in Norway, carried out by a team of six researchers. When I refer to the coding, I will use we. According to Krippendorff (Citation2004, 18), content analysis “is a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from text (or other meaningful matter) to the context of their use”. Content analysis aims at an objective, systematic and measurable description of the content (Kerlinger Citation1986), and is a useful analytical tool to describe characteristics and patterns in a large material.

An important step in content analysis is sampling. In this study, the researched media organizations were strategically selected due to several aspects: First, the starting point for the project was to study the typical small local newspapers. Of the 223 newspaper editions in Norway, 110 are ultra-local, published 1–4 times a week, and have between 1000 and 10,000 subscribers. They represent a part of local journalism that research pays scarce attention. Second, we also wanted to compare the ultra-local journalism to journalism carried out in larger local and regional media, and we aimed to embrace all levels beneath the national newspapers in the umbrella model described above. Third, at the regional level, the national broadcast constitutes an essential part of local/regional journalism, and we included two regional offices from the national broadcast organization NRK. Fourth, Norway is divided into five main regions. As the local media is spread all over the elongated country, we aimed to represent all the geographic regions. Thus, the study comprises 12 ultra-local newspapers, 6 local dailies and 6 regional media (either broadcast or newspapers) representing all regions, as shown in . The number of employees in the news rooms under study varies from 2 to 113.

Table 1. The sample of local and regional media represented in the study.

The content is sampled from a constructed week: six publishing days during 2017.Footnote1 For the newspapers that do not publish daily, we chose the closest publishing date. All journalistic produced content from the actual days were coded: feature stories, news items, editorials and columns, large stories and news in briefs (NIBs), published online and in print. Regarding the broadcast, the study comprised of radio, TV and written stories on their regional internet sites. However, as program format of regional TV and radio is rather short, the share of TV/radio content is rather small, compared to the written format. This is an essential limitation of the study, which has to be taken into consideration. The study includes 6574 articles, coded in 28 different variables, thus embracing a variety of aspects of local journalism aspects. Six of the variables register the characteristic of sources, containing the number of sources, the roles/positions of the sources, and their sex and age. Further, we registered the type of source (personal source, documents/written source, news media, social media) and separated whether the source was open or hidden/anonymous. Another limitation of the study is that we have only registered the primary source, while the secondary or third sources are not coded. When discussing diversity in sourcing, registering at least the secondary source would be of value because this would shed light on sourcing practices. However, to delineate a rather large study, we chose to register only the role of the primary source and take this limitation into consideration when discussing the findings.

Each researcher coded the content from four newsrooms. To secure interpretative congruence (Folger, Hewes, and Poole Citation1984), we developed the coding schema and definitions of the variables together and then started collective coding of a sample of the articles and comparing our results. This procedure caused some variables to be excluded from the analysis because of a deviation in the coding. In further work, we conducted a pre-test to ensure a shared understanding of the codebook. As Potter and Levine-Donnerstein (Citation1999, 271) argue: “If the coders belong to the same community, they share the same interpretive coding schemes. Evidence in the coding of interpretive congruence is also evidence for validating the standard”. We also carried out an inter coder reliability test of 10% of the material. The reliability score is from 81 to 96% for the different variables, which is satisfactory in relation to general reliability requirements (Krippendorff Citation2004).

In further discussion, I will use the term story or item, which embraces both written stories online and in print, as well as TV and radio.

Findings

I will concentrate on three main aspects: the origin, the number and the role of sources. This study comprises both locally produced content as well as stories from news agencies, news stories, columns, feature stories, small NIBs and studio comments on TV and radio. In the following discussion, I will concentrate on the locally produced content. However, first a glimpse of the amount of the content distributed from news agencies and locally produced content, as this sheds vital light on what kind of content the local audience are offered.

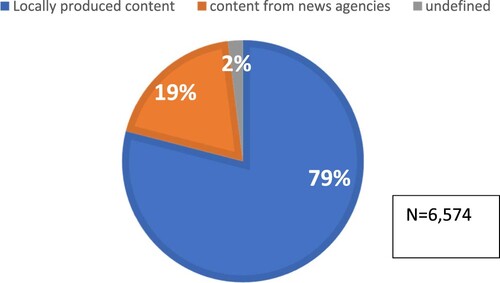

As seen in , 79% of the content in local and regional media is locally produced, while 19% are stories from news agencies and 2 € was not possible to define. Not surprisingly, the news agencies content is found mostly in small NIBs in the newspapers, and studio comments in the broadcast; 22% of the content in these small genres has its origins in the news agencies.

Also interesting to elaborate, is how the use of news agencies differs between the different types of local media. The local dailies publish the largest share of stories from news agencies, at 35% of their content, followed by the regional newspapers, where 26% of the content is based on news agencies. On the other hand, both the regional broadcast and the smallest ultra-local newspapers bring the least agency content; only 2% each.

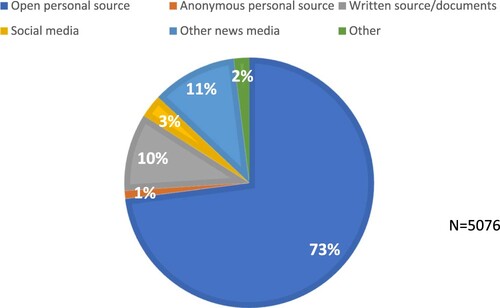

Sources can be individuals, documents or other news media (including social media). Sources can be people whom reporters turn to for information or material resources (Berkowitz Citation2009). The type of sources is shown in .

shows all content where the source is stated, both written texts in print and online, as well as broadcast news in all genres, and both the locally produced content as well as that from news agencies. Personal sources dominate: 74% of the items or stories are based on personal sources. They are mainly identified by names, and only 1% of sources are anonymous individuals, while 73% are open. Ten percent of the content is based on written sources, such as legal documents, public letters and court orders. Eleven percent of the items are based on other news media as sources, while 3% of the content is made with social media as the primary source. When excluding the content from news agencies, the portion of open personal sources increases to 79% and the amount of other news media as source shrinks to 6%. Thus, the locally based journalists act out a relatively scarce amount of “copy–paste” journalism (Lee-Wright Citation2012, 22), while news agencies traditionally more often redistribute content other news media made (Holand and Engan Citation2020).

The Number of Sources

Diversity depends on variation and disparity, which also makes it vital to explore the number of sources in journalism. investigates the number of sources and presents a picture of daily news and feature work in the different types of local and regional newsrooms. Sources are seldom stated in columns, and the small genres of NIBs and studio comments do not offer the thorough sourcing practice. Therefore, these genres are left out of , as are stories from news agencies because I found it most interesting to elaborate the sourcing practice local journalists carry out in different types of local newsrooms. Thus, contains locally produced news and feature stories.

Table 2. Sources in 24 different types of local and regional media in percentages.

As shown in , there is no defined source in 7% of the content. Approximately half (49%) of the news content are based on a single source. 25% are based on two sources, and 19% are based on three or more sources. This finding is confirmed by former studies of local media content, as several identified half of the content as single-source stories (Sjøvaag Citation2018; Allern Citation2001; Mathisen Citation2013). As illustrates, 19%, or every fifth item, are based on three or more sources, which leaves most of the content hardly based on thorough sourcing practice.

In addition, as shown in , exploring the differences in the number of sources between different categories of local media reveals a vital nuance. The analysis shows more single-source cases in the smallest local weeklies, while the regional newspapers and the regional broadcasts publish a larger number of stories based on three or more sources. In other words, working with sources seems to be more in-depth and thorough in the larger newsrooms than in the smaller ones.

Role of Sources

In the coding, we registered the role of personal sources to explore what types of interests and perspectives are given access to the public sphere. Also here, the focus is on the locally produced stories in the news and feature format.

As shown in , leaders in private businesses and public administration dominate the agenda, as more than a quarter of the news stories lean on managing interests. This category contains public servants of various kinds, as well as CEOs/leaders of non-profit organizations and managers of local businesses. Splitting between public and private business enterprises, shows that the managers of private enterprises dominate by 18%, while 8% are public managers.

Table 3. Role of the main source in 24 local and regional media stories (by percentage).

The second-largest category is athletes and coaches from the field of sports. This source category is relatively broad and contains both local youth athletes at the amateur level as well as professional football players and coaches. Third comes grassroots representatives (ordinary citizens) who are the dominating sources in 13% of the content. This category consists of citizens representing themselves and not being interviewed by virtue of a formal position or role they hold. Fourth are the politicians, who are the primary source in 10%of the content. This is mostly local municipal politicians, which confirms the importance of local media as an arena for local political public debate. Still, it is worth noting that grassroots people are used as sources more often than politicians.

Employed persons are primarily sourced in 8% of the items. Compared to the dominating leaders, the local and regional media mediate reality from the leader's point of view far more often than they bring forth experiences from “the groundfloor” or from ordinarily employed individuals—both when bureaucracy and private enterprises are part of the agenda.

At the lower end of the Table, the study identified groups of sources that can be characterized as marginalized voices, being sources in less than 2% of the items. Clients and patients rarely gain access to the news agenda. Further, viewpoints and experience from the perspective of religion or life philosophy are seldom primary sources on the agenda. The same is true for unions; both these source categories remain marginalized. These findings are also supported by previous studies (Nygren Citation2019; Dahlstrøm Citation2013; Allern Citation2001).

Separating different levels of local and regional media shows both similarities and differences. The overall pattern shows compliance, and all four groups of media favor the elites. The marginalized voices are scarcely given a voice in either of the different media groups. However, there also is a tendency that the smaller the newspapers, the more grassroots representatives, and the more NGO voices. The ultra-locals give voice to both these groups more than the larger newsrooms. Previous Norwegian studies confirm this trend: local press is less elite-oriented than their national counterparts (Allern Citation2001; Mathisen Citation2013; Sjøvaag Citation2018). The regional broadcasters contribute to sourcing diversity with a higher use of unions, employed individuals, and clients/patients than any other kind of media. Also, they interview fewer leaders than newspapers.

Discussion

The above findings relate to three major parts of the sourcing practice in the local and regional newsrooms. First, regarding the origins of source, the analysis showed that open personalized sources dominate, and copypasting stories from other news media or social media is rare. It seems as though local and regional media mainly bring their own new and original news stories into the news ecology, which are produced with source transparency and open sources. However, a limitation of this finding is that copy-pasting might be hidden in the text. Still, this might indicate that proximity to community and sources leads to local journalists interacting with people in their communities to a large degree. However, the content analysis is unable to provide any information about whether the sourcing procedure is carried out via telephone or interviews in the field. To thoroughly study how local journalists relate to sources and surroundings, other research methods outside of content analysis are required.

The second aspect elaborated was the number of sources being used. Here I found that the single-sourced stories dominate in the news and feature items, a trend also confirmed in previous studies (O’Neill and O’Connor Citation2008, 493). As Nielsen (Citation2015, 13) states

studies from different countries and contexts have found that local journalism is mostly reactive and based on single sources, frequently self-interested ones like politicians, local government officials or business.

Often, a story based on a single source allows that the source's view of events to be carried unchallenged, and reflects a passive orientation whereby news act as a conveyor belt rather than testing ground for what powerful figures are saying.

The analysis also revealed variations between the different kinds of local media. The ultra-local newspapers have the most single sourcing, while the regional broadcast and the regional newspapers have the least, and also most the multiple-sourced stories. Size might be a vital explanation: Larger newsrooms have more journalists and more resources than smaller ones. Sourcing is also a result of routines and professional newsroom standards (Kleemans, Schaap, and Hermans Citation2017; Wheatly Citation2020), which might differ between smaller and larger newsrooms. For example, small local weeklies have a lower threshold for newsworthiness and convey more curiosa and information about community events, as this constitutes an important part of how local journalism contributes to belonging, identity and local patriotism. The larger newsrooms need to prioritize harder what is placed on the agenda (Mathisen Citation2013).

The third aspect to be discussed is related to the role of the sources gaining access to the mediated agenda, as presented in . Here, four conclusions can be drawn. First, that use of sources reveals an authoritative and elite-oriented pattern, where local elites including politicians, police, leaders and managers dominate. All these source categories possess formal positions of authority and power in their local communities. Second, some specific source categories are seldom used. Unions, denominations, clients and patients are types of sources that rarely become the primary definers. They might be characterized as marginalized voices, placed in the media shadow; more precisely what Nord and Nygren (Citation2002) describe as a social media shadow. As these group rarely become sources, their perspectives and interests are rarely brought up in the mediated agenda or the public sphere. Partly, this is a surprising result, as one might expect that journalists demanding for personified cases would encourage voices as clients and patients, and that the watchdog would bring forth vulnerable groups to contrast those in power. However, both unions and denominations might represent advocacy voices, which as Laursen and Trapp (Citation2019) point out, is often interpreted as a hindrance because they are believed to have a vested interest. Along with the objectivity ideal, advocacy or organized interests might be perceived illegitimate in journalism (Meyer and Lund Citation2014). Nevertheless, these findings are in many ways paradoxical, as both religion and work represent essential arenas in people's lives and thus would be of interest for citizens and the audience, especially in a local context with newsrooms being close to their communities. In both instances, religion and work-life also constitute arenas where power, authority, dispersion and influence are played out as one could expect from vital journalistic interest when following the fourth estate ideal. Of course, the study's limitations counted only the primary source, which should be taken into consideration. These kinds of sources likely would have appeared more often if we also registered second or third sources. However, the primary source often influences the framing of a story (Allern Citation2001). When high prestige official sources appear in the news, the reporter-source relationship tends to legitimize or even reify society's power structures (Berkowitz Citation2009, 109; Manning Citation2001). The high amount of single sources does not either contribute to nuance or correct the elite-domination. This elite-oriented finding is supported by previous studies (Carlson Citation2009). One explanation might be authority. Certain types of sources, such as government officials or municipality officials in the local sphere, are considered to have more authoritative voices than average citizens (Dimitrova and Strömbäck Citation2009). Another explanation lies in the fourth estate ideal of journalism: When journalism accomplishes power to critique and holds power to account, a natural consequence is that powerful elites become sources (Sjøvaag Citation2018; Berkowitz Citation2009; Kleemans, Schaap, and Hermans Citation2017). Further, also professional practice is important: Interviewing elite sources demands less effort from the journalists than contacting citizens who have less publicity experience. Thus, it is easier to contact sources with media experience than others who do not.

Third, and despite this elite domination, this study also identified a diversity where grassroots representatives gain access to a certain degree. As already mentioned, 13% of the sources consist of grassroots representatives. When adding employees, community organizations/NGOs and clients or patients into an extended grassroots category, a total of 27% of the news stories are based on sources not representing power and positions. These sources represent voluntarily work, local enthusiasts, and various types of personal experiences.

Fourth, despite compliance in the overall pattern, this study showed diverging tendencies between different types of local media; where the smallest one brings most grassroots voices. These variations indicate that the stratified media landscape maintains a diversity of voices and viewpoints (Sjøvaag Citation2018, 9). Together, the range of different local and regional media outlets bring forth more diverse voices, perspectives, and interests on the mediated agenda and thus in public debate. The patterns found are distinct and independent of the single journalist professional or newsroom, which underlines the institutionalized aspect of journalism (Allern Citation2001; Cook Citation1998). The norms, rules and news values are part of a longstanding professional practice.

Concluding Remarks

In this article, I have discussed the research question: “What characterizes the sourcing practice in local and regional media, and how does this contribute to diversity in the coverage?” The analysis revealed several different tendencies. Answering the first part of the question, I found a distinct elite-oriented mediated agenda in local and regional news, where people in formal roles and positions are more likely to be interviewed than ordinary citizens. Answering the second part of the question that addressed diversity, the study showed both diversity and the opposite: media shadows. Journalists prefer the elites, routine sources and officials, and in their stories they reflect the view of the elites (see also Figenschau and Beyer Citation2014; Sjøvaag Citation2018; Allern Citation2001). Here, the study confirmed a well-documented trend. As the elites dominate, the consequence is that some voices are left in the media shadow. Regarding roles, organized interests as unions and denominations are rare as are clients and patients in the health care and welfare systems. The interests, perceptions and views of reality of these groups are rarely brought up on the mediated agenda. Also, due to the high degree of single sourcing, the perspectives and realities of the elites are not multiplied, nuanced or corrected by other voices. Single sourcing hardly contributes to diversity. On the contrary, it contributes to a narrowed and limited view of reality.

Journalism as an institution is given a certain legitimacy because of its role in democracy and public debate (Cook Citation1998; Allern Citation2001). This legitimacy also involves presenting a diversity of opinions and a plurality of voices (Mellado and Scherman Citation2020; Becker and Van Aelst Citation2018). Within this institution, there is a sourcing practice favoring the perspectives and interests of the elites in public debate, while the contrasting experiences are rarely brought up. Also, the range of voices on the mediated agenda shape the public's understanding of the world. When individual voices are left in the shadows, certain aspects are omitted in this public understanding and result in knowledge gaps that may impact both the political debate and the societal meaning-making processes. Media shadows counteract diversity.

However, the study also indicated an important diversity in the sourcing practice of local and regional media. Despite the elite domination, the study showed a diverse range of sources where ordinary citizens are given a voice more often than in larger, national media. Grassroots individuals are even given a voice as a first source more often than politicians. Thus, local media stand out as vital arenas in local public debate, where they contribute to bring perceptions other than those of the elites into the media ecology. As such, local media stand out as vital contributors to informed citizenship. The study also revealed interesting differences between the different types of local and regional media, which perhaps is this study's most valuable contribution. The smallest ones most often give a voice to the grassroots. Together with the regional broadcast, the smallest ultra-local media seem to bring the most diverse range of voices into the mediated agenda. Undoubtedly, size matters; the larger the newsroom, the more use of the multiple sourcing. However, the smallest ultra-local newspapers contribute to an important diversity regarding what kinds of voices are allowed access. The study confirmed that despite elite-domination, local media do give voice to groups often being marginalized and left in the media shadow. Ordinary citizens speaking on behalf of themselves and not formal roles and authority are substantial group of sources, and the smallest local outlets are the most important contributor to this.

Public debate is often characterized by a tension between elites and grassroots individuals, and national news media is criticized for favoring the elites. Although local media might stand out as a valuable contrast to the elite domination, where a broader range of citizens may speak in public, define the world, respond to and correct the interpretations of others. Proximity to sources, actors and society might give the local journalist better prerequisites for viewing diverse realities. In a democratic perspective, the local media become vital arenas to secure diversity in perspectives and perceived reality.

The differences found between the different types of local media also underline the importance of an multiple media structure, with different levels of local and regional media spread all over the country. The stratified and varied media landscape contributes to the diversity and enriches public debate. For the Norwegian public debate, this implies that without such a varied structure, democracy will weaken, and a narrowed mediated representation will take place. Press subsidies and public supported broadcast is of vital interest here. Both the smallest ultra-locals and the regional broadcast offer the most diversity regarding sources. The tendencies in this study underlined that press subsidies contribute diversity, which is valued as a democratic good in public debate. Thus, the Norwegian experience could be of interest also in other national contexts. While news deserts and blind spots are problematized as result of newspaper disclosure in many countries, among others the UK and the US, the active media policy and press subsidies in a democratic corporatist country such as Norway seem to work according to its purpose: sustain a varied media structure with diverse content that contribute to a diversity of voices, experiences and viewpoints represented in public debate.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Monday in week 2, Wednesday in week 9, Friday in week 18, Tuesday in week 29, Thursday in week 38, and Saturday in week 46.

References

- Abernathy, P. 2018. The Expanding News Desert. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Abernathy, P. 2021. News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive? Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina press.

- Ali, C. 2017. Media Localism. The Policies of Place. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Allern, S. 1996. Kildenes Makt: Ytringsfrihetens Politiske økonomi [The Power of the Sources: The Political Economy of Free Speech]. Oslo: Pax Forlag.

- Allern, S. 2001. Nyhetsverdier. Om Markedsorientering og Journalistikk i ti Norske Aviser [News Values in ten Norwegian Newspapers]. Kristiansand: IJ-forlaget.

- Allern, S., and M. Blach-Ørsten. 2011. “The News Media as a Political Institution.” Journalism Studies 12 (1): 92–105.

- Becker, K., and P. Van Aelst. 2018. “Look Who’s Talking.” Journalism Studies. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1463169.

- Berkowitz, D. 2009. “Reporters and Their Sources.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanzitsch, 102–115. New York: Routledge.

- Broersma, M., B. den Herder, and B. Schohaus. 2013. “A Question of Power. The Changing Dynamics Between Journalists and Sources.” Journalism Practice 7 (4): 388–395. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.802474.

- Carlson, M. 2009. “Dueling, Dancing or Dominating? Journalists and Their Sources.” Sociology Compass 3 (4): 526–542. doi:10.111/j.1751-9020.00219.x.

- Carlson, M., and B. Franklin. 2011. “News Sources and Social Power.” In Journalists, Sources and Credibility. New Perspectives, edited by B. Franklin and M. Carlson, 1–15. London: Routledge.

- Cook, T. E. 1998. Governing with the News: The News Media as a Political Institution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dahlstrøm, H. K. 2013. “Gud i Sørlandsmediene [God in the Media].” Norsk Medietidsskrift nr 2: s123–s139.

- De Keyser, J., and K. Raeymaeckers. 2012. “The Printed Rise of the Common Man. How Web 2.0 Has Changed the Representation of Ordinary People in Newspapers.” Journalism Studies 13 (5–6): 825–835. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2012.667993.

- Dimitrova, D. V., and J. Strömbäck. 2009. “Look Who’s Talking. Use of Sources in Newspaper Coverage in Sweden and the United States.” Journalism Practice 3 (1): 75–91. doi:10.1080/17512780802560773.

- Ericson, R. V., P. M. Baranek, and J. B. L. Chan. 1989. Negotiating Control: A Study of News Sources. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Figenschau, T. U., and A. Beyer. 2014. “Elites, Minorities and the Media: Primary Definers in the Norwegian Immigration Debate.” Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 55 (1): 23–51.

- Folger, J. P., D. E. Hewes, and M. S. Poole. 1984. “Coding Social Interaction.” In Progress in Communication Science, Volume IV, edited by B. Dervin and M. J. Voigt, 115–161. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Gans, H. 1979. Deciding What’s News. New York: Pantheon.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gumera, J. A., D. Domingo, and A. Williams. 2018. “Local Journalism in Europe: Reuniting with its Audiences.” Sur le Journalisme, About Journalism, Sobre Journalism 7 (2): 4–11.

- Hallin, D., and P. Mancini. 2009. Comparing Media System: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hess, K., and L. Waller. 2017. Local Journalism in a Digital World. London: Palgrave.

- Holand, A. M., and B. Engan. 2020. “Nyheter på Autopilot? Ulike Tilpasninger av Automatisert Medietilbud i Lokalaviser [News on auto pilot? Automatized content in local newspapers].” Norsk Medietidsskrift 2 (27): 1–17.

- Høst, S. 2005. Det Lokale Avismønsteret: Dekningsområder, Mangfold og Konkurranse 1972-2002. [The Local Newspaper Landscape]. Fredrikstad: Institutt for journalistikk.

- Høt, S. 2019. Papiraviser og Betalte Nettaviser 2018. Statistikk og Kommentarer [Printed Newspapers and Online Papers. Statistics and Comments]. Volda: Høgskulen i Volda.

- Howells, R. 2015. “Journey to the Centre of a News Black Hole. Examining the Democratic Deficit in a Town with no Newspaper.” PhD diss., Cardiff: Cardiff University.

- Kerlinger, F. N. 1986. Foundations of Behavioral Research. Forth Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publ.

- Kleemans, M., G. J. Schaap, and L. Hermans. 2017. “Citizen Sources in the News: Above and Beyond the vox pop?” Journalism 18 (4): 464–481. doi:10.1177/1464884915620206.

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosenstiel. 2014. The Elements of Journalism. Rocklin, CA: Three Rivers Press.

- Krippendorff, K. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Laursen, B., and N. L. Trapp. 2019. “Experts or Advocates: Shifting Roles of Central News Sources Used by Journalists in News Stories.” Journalism Practice. doi:10.1080/17512786.2019.1695537.

- Lee-Wright, P. 2012. “The Return of the Hephaestus: Journalists Work Recrafted.” In Changing Journalism, edited by P. Lee-Wright, A. Philips, and T. Witschge, 21–40. London: Routledge.

- Linden, C. G., L. Morlandstø, and G. Nygren. 2021. “Local Political Communication in a Hybrid Media System.” In Power, Communication and Politics in the Nordic Countries, edited by E. Skogerbø, Ø Ihlen, N. N. Kristensen, and L. Nord, 155–174. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Manning, P. 2001. News and News Sources. A Critical Introduction. London: Sage Publications.

- Mathisen, B. R. 2013. “Gladsaker og suksesshistorier. En sosiologisk analyse av lokal næringslivsjournalistikk i spenning mellom lokalpatriotisme og granskningsoppdrag [Positive Stories About Success. A Sosiological Analysis of Local Journalism in The Tension Between Local Patriotism and Critical Watchdog Ideal].” PhD diss., Bodø: Universitetet i Nordland.

- Mathisen, B. R., and L. Morlandstø. 2018. Lokale Medier. Samfunnsrolle, Offentlighet og Opinionsdanning. [Local Media – Societal Role]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Mellado, C., and A. Scherman. 2020. “Mapping Source Diversity Across Chilean News Platforms and Mediums.” Journalism Practice. doi:10.1080/17512786.2020.1759125.

- Meyer, G., and A. B. Lund. 2014. “Da Journalisterne Tabte Interessen Et Bidrag til et Overset Paradigmeskiftes Begrebshistorie. [When Journalists Lost Their Interest].” Nordicom-Information 36 (4): 51–64.

- Napoli, P. M., S. Stonbely, K. McCollough, and B. Renningen. 2015. Assessing the Health of Local Journalism Ecosystems. New Brunswick: Rutgers University.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2015. “Introduction: The Uncertain Future of Local Journalism.” In Local Journalism. The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media, edited by R. K. Nielsen, 1–25. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Nord, L., and G. Nygren. 2002. Medieskugga. [Media Shadow]. Stockholm: Atlas förlag.

- Nygren, G. 2019. “Fler Källor – men Vissa Grupper Saknas Nästan Helt [More Soruces, Hower Some Groups are Lacking].” In Nyheter – Allt mer en Tolkningsfråga? Mediestudiers Innehållsanalys 2007-2018. [News – a Question of Interpretation?], edited by I. Karlsson, M. og T, and G. Lars, 72–85. Stockholm: institutet för mediestudier.

- O’Neill, D., and C. O’Connor. 2008. “The Passive Journalist.” Journalism Practice 2 (3): 487–500.

- Ottosen, R. 2004. I Journalistikkens Grenseland: Journalistrollen Mellom Marked og Idealer [The Role of Journalists Between State and Market]. Kristiansand: IJ-forlaget.

- Peter, C., and T. Zerback. 2020. “Ordinary Citizens in the News: A Conceptual Framework.” Journalism Studies 21 (8): 1003–1016. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1758190.

- Potter, J. W., and D. Levine-Donnerstein. 1999. “Rethinking Validity and Reliability in Content Analysis.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 27 (3). doi:10.1080/00909889909365539.

- Schudson, M. 2003. The Sociology of News. New York: Norton.

- Sjøvaag, H. 2018. “Journalistikkens Attraksjon til Makten: Politisk Kildemangfold i Norske Nyhetsmedier [Journalisms Attraction to Power. Political Source Diversity in Norwegian News Media].” Norsk Medietidsskrift 25 (2): 1–18.

- Sjøvaag, H., and N. Kvalheim. 2019. “Eventless News: Blindspots in Journalism and the “Long Tail” of News Content.” Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 8 (3): 291–310. doi:10.1386/ajms_00003_1.

- Skogerbø, E., and R. Karlsen. 2021. “Media and Politics in Norway.” In Power, Communication and Politics in the Nordic Countries, edited by E. Skogerbø, Ø Ihlen, N. N. Kristensen, and L. Nord, 91–112. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Sparrow, B. H. 1999. Uncertain Guardians: The News Media as a Political Institution. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Stroobant, J., R. De Dobbelaer, and K. Raeymaeckers. 2018. “Tracing the Sources: A Comparative Analysis of Belgian Health News.” Journalism Practice 12 (3): 344–361.

- Svith, F., P. F. Jacobsen, S. K. Rasmussen, J. Jensen, and H. T. Andersen. 2017. Mediernes Udvikling i Danmark. Lokal- og Regionalmediers Indhold, Rolle og Betydning i Lokalområder [Content and Societal Role of Local and Regional Media in Denmark]. Århus: Danmark Medie- og Journalisthøjskole.

- Syvertsen, T., G. Enli, O. J. Mjøs, and H. Moe. 2014. The Media Welfare State: Nordic Media in the Digital Era. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

- Tiffen, R., P. K. Jones, D. Rowe, T. Alberg, S. Coen, J. Curran, K. Hayashi, et al. 2014. “Sources in the News. A Comparative Study.” Journalism Studies 15 (4): 374–391.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K., and T. Hanitzsch. 2009. The Handbook of Journalism Studies. New York & London: Routledge.

- Waschková, C. L. 2017. “The Voice of the Locality.” In Voice of the Locality: Local Media and Local Audience, edited by C. L. Waschková, 19–38. Masaryk University: Prague.

- Wheatly, D. 2020. “A Typology of News Sourcing: Routine and Non-Routine Channels of Production.” Journalism Practice 14 (3): 277–298. doi:10.1080/17512786.2019.1617042.