ABSTRACT

COVID-19 has provoked fears that the heavy reporting of pandemic developments may cause climate change to slip from public attention. Views have also converged that the focus should be on the positive lessons of COVID-19 for addressing climate change. This paper examined Guardian Online and Positive News to identify examples of good practice in reporting the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19, as both are committed to covering climate change and practice solutions-oriented constructive journalism that provides context by explaining relations between issues. The study sought to identify the types of synergistic effects that were reported and how they were reported through metaphors—key conceptualisation tools. Analysis of 153 news articles published in the first year of the pandemic showed that the coverage of synergistic effects was solutions-oriented and synergistic effects were discussed mainly through Movement and Colour metaphors—particularly the colour Green. War metaphors which have dominated reporting when climate change and COVID-19 have been discussed separately were rare. Reliance on Movement and Colour metaphors can be interpreted as a positive practice, as Movement metaphors are familiar, vivid and more flexible than War metaphors, while Green metaphors are closely associated with environmentalism and have positive connotations.

Introduction

Research has consistently highlighted the effects that climate change may have on infectious diseases (Wu et al. Citation2016), especially those that are vectorborne (transmitted by insects which tend to be more active at higher temperatures) or waterborne (for example, resulting from poor sanitation due to flooding) (Shuman Citation2010). A Citation2008 report by the Wildlife Conservation Society identified 12 infectious diseases whose spread might be exacerbated by alterations in temperature and precipitation levels. The World Health Organization has also recognised that changes in infectious disease transmission patterns are a likely consequence of climate change (World Health Organization Citation2020a). Initiatives such as The Lancet’s Countdown on Health and Climate Change make it clear that a leading threat from climate change relates to intensifying infectious disease impacts (Watts et al. Citation2019). Consequently, much effort has focused on assessing the societal adaptations that might help mitigate the effects of such outbreaks (Ebi et al. Citation2013), and the infectious disease community has been urged to research more extensively the interactions between climate change and infectious diseases (The Lancet Infectious Diseases Citation2017).

While other coronaviruses have exhibited seasonal patterns, there is no scientific evidence to date that either weather (short-term variations in meteorological conditions) or climate (long-term averages) have directly contributed to or caused the emergence of COVID-19 or impacted its transmission (World Health Organization Citation2020b). Amidst the current outbreak, the question that has commanded most attention at national and international level has been how measures to contain COVID-19 may offer solutions to climate change (see e.g., Greenpeace European Unit Citation2020; Johnson Citation2020; OECD Citation2021; World Health Organization Citation2020b). Societal responses to COVID-19 (such as social distancing policies) appear to have contributed to short-term improvements in air quality (European Space Agency Citation2020) and environmental noise (Zambrano-Monserrate, Ruano, and Sanchez-Alcalde Citation2020) as people have reduced their use of transport and much industrial production has stopped. However, societal responses to the COVID-19 pandemic may create long-term environmental impacts through increased plastic waste (chiefly from single-use personal protective equipment) (Zambrano-Monserrate, Ruano, and Sanchez-Alcalde Citation2020) and social distancing policies have disrupted international meetings on climate change, including the 26th session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Climate Change Conference, which was scheduled to be held in Glasgow, UK in 2020 (UN News Citation2020).

Recognition of the possible negative impacts that measures to address COVID-19 may have on the climate has led to calls for long-term plans for a “green recovery” (e.g., European Commission Citation2020). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has launched a database tracking national-level measures with environmental relevance which cover areas ranging from energy, water and biodiversity to waste management and pollution (OECD Citation2021). This is not the first time that calls for a “green recovery” have been made. Following the financial crisis of 2008–2009, the “greenFootnote1 recovery” metaphor was used to argue for climate-friendly economic stimulus packages (Shaw and Nerlich Citation2015). Metaphors are in fact widespread in human communication and especially common in discussions of complex issues (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980). They are a crucial conceptualisation tool as affirmed in experimental studies, which show that we understand issues differently depending on the types of metaphors that are used to describe them (see e.g., Thibodeau, Hendricks, and Boroditsky Citation2017). A large part of the conceptualisation processes in the media also involve metaphor (Kövecses Citation2018) and journalists are believed to seek out quotes that employ metaphors (Williams Citation2018).

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, journalists have had to dedicate much attention to the immediacies of the pandemic raising fears that climate change may “slip from the top of the global agenda” (The Lancet Citation2020). But many news organisations have made public commitments to consistently report climate-related issues. Guardian Online is among the UK’s newspapers with the highest volume of environmental reporting (Nofri Citation2011). In 2015, it launched the “Keep it in the ground” campaign, which called for reader participation to help solve climate change by divesting and moving their money from fossil fuels to renewable energy (Howard Citation2015). In 2019, it joined the Covering Climate Now project, which aims to report “the rapidly uncoiling climate crisis and its solutions” (Hertsgaard and Pope Citation2019). The UK news magazine Positive News has a section on the “Environment” and has been a major participant in workshops bringing together scientists, activists and journalists to explore how the climate crisis can be covered “from a solutions lens” (Climate Visuals Citation2020). Both Guardian Online and Positive News are committed, if to different degrees, to the practice of constructive journalism that is solutions-oriented and aims to provide context by explaining the relations between issues. While Positive News is committed to constructive reporting in the entirety of its coverage, Guardian Online has a dedicated section called “The Upside”.

In the light of fears that heavy reporting of pandemic developments might cause climate change to slip from public attention and converging national and international views that the focus should be on the positive lessons of COVID-19 for addressing climate change, this paper analysed two news outlets—Guardian Online and Positive News—that should provide examples of good practice in reporting the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 (from a solutions-angle)—because they are committed to provide climate change coverage and practice solutions-oriented constructive journalism which aims to elaborate relations between issues. The focus of this study is on the types of synergistic effects that were reported and how they were reported through metaphors—key tools for conceptualising complex issues. The next section presents previous research on (a) the reporting of the synergistic effects of climate change and infectious diseases; (b) the role of metaphors in the reporting of health and environmental topics and (c) constructive journalism. The data and method of analysis are described next. The following section reports the types of synergistic effects that were discussed in the analysed data, the metaphors that were used and possible explanations for and implications of such metaphor use. The conclusion summarises the study’s key findings, identifies limitations and possible directions for future research.

Literature Review

This article draws on three bodies of research and theory: (a) previous studies of how the synergistic effects of climate change and infectious diseases have been reported in the media; (b) the role of metaphors in such reporting; and (c) constructive journalism as a reporting practice that is solutions-oriented and aims to provide context by explaining the relations between issues (e.g., McIntyre Citation2020; Meier Citation2018). These are reviewed in the same order in what follows.

Reporting the Synergistic Effects of Climate Change and Global Pandemics

While the number of studies separately examining the media coverage of climate change and that of global pandemics has been growing (Anderson Citation2009), analyses of how the news media report the synergistic effects of these two phenomena are rare. Among these scarce examples is a study by Tolan (Citation2007), who reported that a news article from her study of Chinese media coverage of climate change cited the potential contributions of climate change to the spread of infectious diseases. In another study, Feldman, Hart, and Milosevic (Citation2017) analysed climate change reporting in US media and showed that a “public health frame” which highlighted the potential impacts of climate change on asthma, allergies and infectious diseases was among the most frequently used. Beyond such remarks, little has been written about the precise ways in which news articles conceptualise the relation between climate change and global pandemics. This is even though climate change has been referred to as a pandemic in and of itself and has been discussed in the scientific literature as part of “syndemics” or synergies of epidemics (Swinburn Citation2019).

Within the large body of studies which focus separately on climate change reporting or on the reporting of global pandemics, the analysis of metaphors is a well-established strand of research. In the case of climate change, a common finding across metaphor studies is that the UK media tend to discuss climate change through WarFootnote2 metaphors (Atanasova and Koteyko Citation2017; Cohen Citation2011). Studies of the metaphors used to conceptualise infectious diseases in the UK media similarly find that War metaphors predominate (Nerlich Citation2010; Taylor and Kidgell Citation2021; Washer and Joffe Citation2006; but see Wallis and Nerlich Citation2005 for an exception)—including in the reporting of COVID-19 (Musolff Citation2020; Semino Citation2021).

Metaphors

A metaphor involves talking and potentially thinking about (or conceptualising) one thing in terms of another. Linguists have studied relatively stable and universal “conceptual metaphors” since the 1980s where a more complex “target domain” is understood through a simpler “source domain” (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980). An example of a widely used conceptual metaphor is life is a journeyFootnote3 (where the more abstract target domain of life is conceptualised through the more concrete source domain of journey). This popular conceptual metaphor finds linguistic expression in statements such as “I am at a cross-road in my life”. A more recent body of research has focused on “discourse metaphors” (see e.g., Nerlich Citation2010; Zinken, Hellsten, and Nerlich Citation2008). In comparison to conceptual metaphors that are believed to be near-universal and relatively stable over time, discourse metaphors function as key conceptualising devices within specific discourses, over certain periods of time. They are grounded in conceptual metaphors, but their meaning is shaped by the context of use.

A key proposition of metaphor analysis studies is that metaphors are not neutral ways of representing and perceiving reality. By drawing similarities between two things and calling something by another name metaphors can have profound implications, as the use of one metaphor over another promotes particular readings of an event or issue (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980; Lule Citation2004; Musolff Citation2006). Experimental studies have shown that we understand issues differently depending on the types of metaphors that are used to describe them (Thibodeau, Hendricks, and Boroditsky Citation2017). Each source domain that is involved in a metaphor highlights some aspects of the target domain and backgrounds others and thus, facilitates different understandings of the issue in question. For example, War metaphors, when applied to an illness, highlight the need to eliminate it and background the possibility of adapting and learning to live with it (Semino Citation2021).

War metaphors are, in fact, among the most widely used metaphors in various contexts (Karlberg and Buell Citation2005). One possible explanation might have to do with their perceived benefits as they are believed to be especially well-suited for expressing definitive, clear-cut outcomes (such as victory or defeat); be highly successful in conveying and invoking emotions; encourage the expenditure of massive resources to achieve an outcome; create a sense of urgency to act; draw on shared basic knowledge about how wars develop (even if that knowledge may be second-hand); and have a simple structure for discussing the parties involved (in terms of allies versus enemies) (Annas Citation1995; Baehr Citation2006; Flusberg, Matlock, and Thibodeau Citation2018). But arguments have been made against the use of War metaphors especially when discussing health issues starting with Sontag’s (Citation1989) seminal work on cancer (for more recent examples of such calls relating to COVID-19 see e.g., Bates Citation2020; Chapman and Miller Citation2020; Pfrimer and Barbosa Citation2020). Concerns include that militaristic language encourages stigma by blaming individuals for “not fighting hard enough” when they fail to recover from an illness (Sontag Citation1989). In the case of COVID-19, critiques have centred on concerns that War metaphors might harness support for authoritarian measures that limit civil liberties (Panzeri, Di Paola, and Domaneschi Citation2021) and increase people’s already existing fears whereas fear should be assuaged in a pandemic (Isaacs and Priesz Citation2020).

Constructive Journalism

Constructive journalism is a type of reporting that seeks to balance the overemphasis on problems and negativity in mainstream news with a focus on how social problems can be responded to (Gyldensted Citation2015; Haagerup Citation2017). While its popularity is recent, owing to the work of Danish news editors and journalists (see Gyldensted Citation2015; Haagerup Citation2017), the term and concept share similarities with “older” types of journalism such as peace journalism (Aitamurto and Varma Citation2018). The term is often used synonymously with “solutions journalism” (e.g., “solutions or constructive journalism” in McIntyre Citation2020, 41) and definitions of constructive journalism regularly refer to solutions. “[F]ocus[ing] on solutions” has been identified as “a way of practicing constructive journalism” (McIntyre Citation2020, 40). Constructive journalism has been described as a type of reporting that “add[s] a solution-oriented framing” to a story (McIntyre and Gyldensted Citation2018, 666) and seeks to “forge a path to a better society by featuring solutions to ongoing problems” (Aitamurto and Varma Citation2018, 698). Journalists themselves interpret constructiveness as “taking solution-oriented approaches” (Hautakangas and Ahva Citation2018, 737). Another prominent theme in definitions of constructive journalism is that it seeks to provide context by explaining the relations between issues (Meier Citation2018).

The principles of constructive journalism have been adopted worldwide by both mainstream news outlets (e.g., the New York Times within its “Fixes” column) and dedicated publications (e.g., Perspective Daily), which in this study are represented by Guardian Online (and its column “The Upside”) and Positive News (the UK’s first dedicated constructive journalism news magazine), respectively. Positive News describes itself as the UK’s first “constructive journalism” news magazine committed to “rigorous, solutions-focused reporting” in the entirety of its coverage (Purdy Citation2018). The integration of constructive reporting within Guardian Online is more compartmentalised. In 2018, Guardian Online launched its constructive journalism “stream” “The Upside” dedicated to “solutions focused reporting that seeks out answers, solutions, movements and initiatives to address the biggest problems besetting the world” (Rice-Oxley Citation2021).

The principles of constructive reporting can be successfully applied to various issues (McIntyre and Gyldensted Citation2017). Although some of the earliest examples of constructive news have focused on climate and health issues (see Gyldensted Citation2015; Haagerup Citation2017) and environmental issues are considered to be in particular need of constructive reporting (Aitamurto and Varma Citation2018), academic interest in how constructive news deal with climate and health issues is only beginning to emerge (Ahva and Hautakangas Citation2018) (but see Atanasova 2019 and McGinty et al. Citation2019 for exceptions).

Data and Method

Data

The period of analysis was from 1 January 2020 (Chinese health officials first informed the World Health Organization about patients with a mysterious pneumonia on 31 December 2019) (World Health Organization Citation2020c) until 31 December 2020 (marking a full year since COVID-19 first came to public attention). Guardian Online and Positive News were searched using the terms “climate” and “COVID-19” or “coronavirus” or “covid” in Google’s Advanced Search option. The results from this search were screened and the following types of texts were excluded: news articles reprinted from a news agency; opinion pieces and letters; news articles commissioned, produced and/or funded by outside parties (labelled as e.g., “paid content”, “supported by”). In the case of Guardian Online, the search was limited to its UK edition and results from The Observer were excluded. Applying these criteria resulted in a final sample of 153 news articles (141 from Guardian Online; 12 from Positive News). None of the 141 news articles published in Guardian Online were from its constructive journalism column “The Upside”. News articles published in Guardian Online were, on average, longer (824 words) than those published in Positive News (668 words).

Method

The news articles were analysed following the three steps of Charteris-Black’s (Citation2004) critical metaphor analysis approach: identification, interpretation and explanation. Within the identification step, the news articles were read to identify “metaphor keywords”, referring to words or expressions used in a metaphorical sense (e.g., “cross-road” from the example “I am at a cross-road in my life”). To decide whether a word or an expression was used metaphorically, the researcher considered whether it has a more basic meaning (more concrete, precise or related to bodily action meaning) in other contexts (Pragglejaz Group Citation2007). The researcher consulted MetaNetFootnote4—a repository of conceptual metaphors and their indicative words. Sections containing metaphor keywords were systematically lifted from each news article and entered into a spreadsheet, the rows of which represented the news articles and the columns recorded the instances and frequencies of different metaphor keywords. At the interpretation step, metaphor keywords were associated with conceptual metaphors understood as relatively stable, widely used conceptualisations of one thing in terms of another (e.g., Journey as per the above example). At the explanation stage, the specific functions that the identified metaphors performed were elaborated (e.g., in the above example—to simply conceptualise life). The researcher’s coding was independently checked by another researcherFootnote5 to ensure accuracy and consistency, coding decisions were discussed, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion (see e.g., Wallis and Nerlich Citation2005).

Findings and Discussion

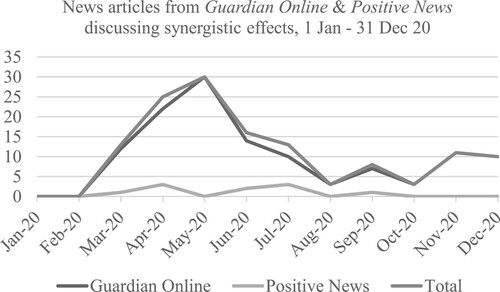

Of the 153 news articles in the final sample, 132 discussed the relation between climate change and COVID-19 (122 from Guardian Online, 10 from Positive News); 21 mentioned both issues but did not elaborate a link (19 from Guardian Online, 2 from Positive News). An example of the latter is a news article which mentioned the search term “COVID-19” while speculating whether Greta Thunberg has had the virus and it also mentioned the search term “climate” when introducing her as “the Swedish teenager who inspired the global school climate strikes” (Taylor Citation2020a). News articles which discussed the relations between climate change and COVID-19 started to appear in March 2020 when the UK announced its first lockdown (Institute for Government Citation2021; see ). Reporting the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 peaked in May 2020 when a conditional plan for lifting the restrictions of the first UK lockdown was released (Institute for Government Citation2021, see ).

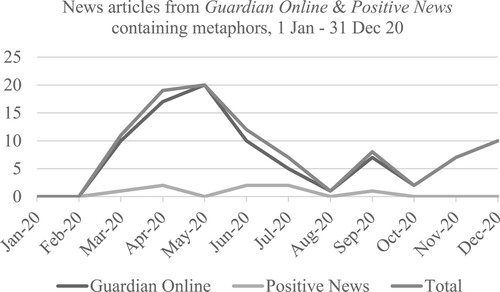

Of the 132 news articles which explored the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19, 97 contained at least one instance of metaphor use (89 from Guardian Online; 8 from Positive News). News articles which discussed the relations between the two issues and contained at least one instance of metaphor use peaked in May 2020 (see ). A significant spike in the use of metaphors in the reporting of the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 was also observed in April 2020 when it was stated that the lockdown announced the previous month would be extended further (Institute for Government Citation2021).

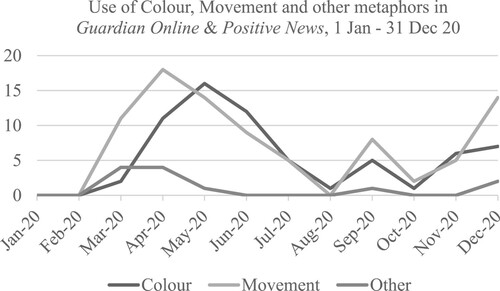

The key findings of this study are that: (1) the coverage of synergistic effects focused on how responses to COVID-19 might offer solutions to climate change rather than whether and how climate change may have contributed to the emergence or transmission of COVID-19; (2) the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 were discussed mainly through Movement metaphors (86 instances) and Colour metaphors—specifically the colour Green (66 instances); rarely through other metaphors such as Illness (4 instances), Crime (3 instances), War (3 instances), Phoenix (1 instance) and Sport (1 instance). When used, metaphors fulfilled a range of functions which will be elaborated in what follows (see ).

Table 1. Metaphors and functions.

Solutions-oriented Synergistic Effects

All 132 news articles which explored the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 focused on how responses to COVID-19 might offer solutions to climate change rather than whether and how climate change may have contributed to the emergence or transmission of COVID-19. This focus is consistent with that of international organisations (e.g., OECD Citation2021; World Health Organization Citation2020b), national priorities (Johnson Citation2020) and the general sentiment in the environmental and wider community that the focus should be on what good can come out from the COVID-19 crisis for the climate (Greenpeace European Unit Citation2020). The solution-orientation in reporting the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 is largely to be expected in Positive News given the news magazine’s comprehensive commitment to constructive journalism that is solutions-oriented. The focus on solutions in Guardian Online is potentially more interesting, as none of the Guardian Online news articles identified and analysed in this study appeared in its constructive journalism column “The Upside”. While the possible influence of constructive journalism practices cannot be implicated in explaining the focus on solutions in news articles from the Guardian Online, this finding may suggest that “more traditional” forms of reporting have an equally important role to play in helping to predict, imagine and create hopeful environments of the future.

Movement Metaphors

Use of Movement metaphors was most common in the analysed data and peaked in April 2020 when a further extension to the first UK COVID-19 lockdown was announced (see ).

Movement metaphors are exceptionally common in nearly every area of human communication (Kövecses Citation2010; Matlock Citation2013). They find linguistic expression in statements like “the week raced past” which contain motion language but convey no actual movement (in contrast to literal motion expressions such as “the car raced past”). Their widespread use can be related to how familiar and intuitive motion language is, as it is grounded in our vivid and easy to recall, everyday experiences as pedestrians, cyclists, drivers. According to Semino (Citation2021, 51), “the most frequent metaphors tend to draw from basic, embodied, sensorimotor experiences”. Movement metaphors can involve a change of location or can be stationary (e.g., “shake the trend”). When a change of location is involved, movement has direction—forwards and backwards, upwards and downwards (Kövecses Citation2010). These different directions of movement are evaluated differently—movement forwards and upwards typically signifies something positive, while backwards and downwards movement generally suggests a negative development (e.g., “he came down with the flu”), although not necessarily (e.g., “going back to the good old days”). Movement can happen at different speeds and speed also carries specific sentiments—moving fast is generally seen as positive (e.g., “he’s a speeding bullet”), slow is perceived as negative (e.g., “trade negotiations are moving at a slow pace”) although there are exceptions (e.g., “slowdown in emissions leads to improvements in health”) (Tomlinson Citation2007).

When used, Movement metaphors fulfilled the following functions: argue that climate protection is key to preventing future pandemics and demonstrate the positive impact of COVID-19 on the climate, but also demonstrate the negative impact of COVID-19 on the climate, demonstrate the negative impact of COVID-19 on climate initiatives, argue that COVID-19’s positive climate impact will be short-term and argue the need for climate-friendly responses to COVID-19. The examples of Movement metaphors that follow are indicative and not exhaustive. It should also be noted that an excerpt given as an example to demonstrate the use of a particular metaphor may contain other metaphor types as well.

Arguments that climate protection is key to preventing future pandemics were realised through directional motion verbs. The idea of our use of natural resources as motion along a path with a beginning and an end was implied in examples such as “[t]o prevent further [COVID-19-like] outbreaks, the experts said, both global heating and the destruction of the natural world for farming, mining and housing have to end” (Carrington Citation2020a). Other examples relied on verbs of inherently directed motion where the direction of the movement (e.g., away from, towards) is implied even if not explicitly stated, as in “[p]rotecting nature is vital to escape era of pandemics” (Carrington Citation2020b).

When Movement metaphors were employed to demonstrate the positive impact of COVID-19 on the climate, the positive connotations of backwards and downwards movement were consistently invoked: “UK lockdown causes big drop in air pollution (…) there had been a significant fall in pollution” (Carrington Citation2020c); “[air pollution] has fallen since the coronavirus pandemic” (Haines Citation2020a). “Plunge” as a verb and noun was repetitively used to present the downwards movement of pollution levels as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns as not only significant and positive but also sudden: “[lockdowns] sent greenhouse gas emissions plunging” (Harvey Citation2020a); “[t]he plunge [of emissions in the UK and France] reflects the prolonged and severe lockdowns in both countries” (Harvey Citation2020b). Other examples relied on the high cultural value of speed—“[the] shift away from dirty fossil fuels has accelerated during the lockdown” (Watts and Ambrose Citation2020). However, moving slow or even stopping can carry positive connotations as well—“[as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns] environmental indices have paused” (Watts Citation2020a). Movement metaphors pertaining to speed were also employed to demonstrate the negative impact of COVID-19 on the climate, as in “cleaner skies [as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns] are accelerating climate change” (Ravilious Citation2020)

Movement metaphors, and particularly those which invoke a very specific type of movement—that of a train and the accidental disruption of its journey—were used to demonstrate the negative impact of COVID-19 on climate initiatives: “Cop26 climate talks could be derailed by coronavirus” (Harvey Citation2020c); “[a key preliminary meeting for Cop26 is] expected to be derailed by widespread lockdowns and travel restrictions” (Ambrose and Harvey Citation2020).

Arguments that COVID-19’s positive climate impact will be short-term were realised by qualifying the “falls” in pollution as “temporary”, as in “[as a result of the COVID-19 lockdowns] countries are experiencing temporary falls in carbon dioxide and nitrogen dioxide of as much as 40%” (Watts Citation2020a). News articles also reported how “[c]arbon dioxide emissions, which plunged when lockdowns took effect, had since begun to rebound sharply” (Harvey Citation2020d) or “[g]reenhouse gas emissions, which fell this spring [as a result of lockdowns] are already rebounding” (Harvey Citation2020e) and pointed out that “emissions will rebound as countries reopen” (Yurk Citation2020) thus emphasising the short-term nature of the positive climate impact of COVID-19 lockdowns.

Movement metaphors were also employed to argue the need for climate-friendly responses to COVID-19 in order to sustain the environmental improvements brought on by the lockdowns—“[t]here is nothing to celebrate in a likely decline in emissions [as a result of COVID-19] because in the absence of the right policies and structural measures this decline will not be sustainable” (Ambrose Citation2020a); “[w]hile greenhouse gas emissions are set to fall this year, perhaps by as much as a tenth, any beneficial impact on the climate is likely to be short-lived (…) if the economic recovery [from COVID-19] resumes on a high-carbon path” (Harvey Citation2020f). When arguing the need for climate-friendly responses to COVID-19, Movement metaphors tended to occurred together with Colour metaphors and particularly the colour Green—“[a] green recovery is essential as we emerge from the Covid-19 crisis” (Ambrose Citation2020b).

[if governments plan to] return to business as usual, environmental gains are likely to be reversed (…) leading scientists have jointly signed an open appeal for governments to use recovery packages [from COVID-19] to shift in a greener direction rather than going back to business as usual. (Watts Citation2020a)

governments to bring forward plans for a green recovery from the Covid-19 crisis, to set the world on the right track to meet the Paris goals (…) the recovery from the Covid-19 crisis can steer us to a more sustainable path. (Harvey Citation2020g).

Overall, Movement metaphors offer flexible options for discussing the relation between climate change and COVID-19. As seen from the data presented above, movement can be reversed, accelerated, stalled and there can be a change in direction. With their flexibility, Movement metaphors lend themselves to being employed to make various arguments regarding the synergistic effects of the two issues (see ). Movement metaphors are well-suited for suggesting that the link between climate change and COVID-19 is fluid and indeterminate. The use of Movement metaphors matches the uncertainty around the exact climate implications of our responses to COVID-19.

Colour Metaphors

Colour metaphors, and specifically the colour Green, were the second-most common in the analysed data with their use peaking in May 2020 when a conditional plan for lifting the UK COVID-19 lockdown restrictions was released (see ).

The colour green is closely associated with environmentalism (Bevitori Citation2011; Rodríguez, Laura, and Plaza Citation2007). “Going green”, for example, is a widely used metaphor signalling adoption of climate-friendly political positions, participation in climate-friendly practices and advocacy for the adoption of such practices (Bevitori Citation2011; Dobrin Citation2010). “Green” in its metaphorical sense features regularly in arguments exploring the business opportunities presented by climate change as in discussing the therapeutic but also economic gains from “green medicine” (Väliverronen and Hellsten Citation2002) or explaining how industries from mining and metallurgy to car manufacturing can increase their profits by “turning green into gold” (Nerlich Citation2012). The metaphorical term “Green New Deal” was widespread in use in the aftermath of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis to refer to economic stimulus packages that would include significant climate-friendly investments (Feindt and Cowell Citation2010). Another metaphor that was common following the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 was “green recovery” which was similarly employed to argue for climate-friendly economic incentives (Shaw and Nerlich Citation2015). Overall, Green metaphors carry favourable and positive meanings (Bevitori Citation2011).

In line with these favourable connotations, Green metaphors were used to demonstrate the positive impact of COVID-19 on the climate. A news article referred to the reduction in pollution and return of wildlife to some areas as a result of the COVID-19 lockdowns as the “green new reality (…) of pandemic side-effects” (Milman Citation2020). In most cases, the metaphorical use of “green” and its word forms (e.g., “greening”, “greener”) occurred within arguments in favour of the need for climate-friendly responses to COVID-19: “experts have been calling for economic rescue packages [post-COVID-19] (…) to come with green strings attached. (…) With the right green stimulus policies (…) we can deliver on the goals of the Paris agreement” (Harvey Citation2020f); “Covid-19 economic rescue plans must be green” (Harvey Citation2020h).

[t]he Committee on Climate Change has published its recommendations for the UK government to deliver a green Covid-19 recovery (…) The CCC’s analysis expands on the advice it gave to the prime minister in May, which set out the principles for a green Covid-19 recovery. (Haines Citation2020b)

Other Metaphors

Other metaphors included Crime, Illness, Phoenix, Sport and War metaphors. The use of such metaphors is described in the same order in what follows.

Crime metaphors were used to argue that climate change is a more serious problem than COVID-19 and demonstrate the negative impact of COVID-19 on climate initiatives. An example of the former is a news article which quoted UK prime minister Boris Johnson stating that the climate is the defining crisis of our times and “[w]e cannot let climate action become another victim of coronavirus” (Harvey Citation2020i). An example of the latter is a news article quoting representatives of the StopHS2 campaign (which seeks to protect the environment by opposing the construction of the HS2 high-speed railway linking up London, the Midlands, the North and Scotland) saying that HS2 is “using the coronavirus crisis as cover to speed up the tree-felling (…) because they think there will be no witnesses” (Rawnsley and Barkham Citation2020).

Illness metaphors were employed to argue that climate change is a more serious problem than COVID-19. Katherine Egland, environment and climate justice chair for the US National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People national board of directors was quoted saying that “[sooner or later there will be a COVID-19 vaccine but] there is no vaccine to inoculate us against climate change” (Pilkington Citation2020). Illness metaphors were also used to argue the need for climate-friendly responses to COVID-19, as in acknowledging that “[t]he [COVID-19] lockdown has reduced emissions (…) but the virus should not be seen as an environmental panacea” and post-pandemic recovery should be climate-friendly (Watts Citation2020b). Arguments in favour of the need for climate-friendly responses to COVID-19 were also realised through a Phoenix metaphor, as in “regarding the climate (…) something new is coming from the ashes of the corona crisis. We’ll rise out of this” provided world leaders emphasise a sustainable economic recovery from COVID-19 (Watts Citation2020b).

Sport metaphors were employed to demonstrate the positive impact of COVID-19 on the climate, as in “[l]ockdown and sunny weather help UK set new record for coal-free power” (Haines Citation2020c).

War metaphors were used to argue that climate change is a more serious problem than COVID-19, as in “[d]eadly heatwaves, floods and rising hunger far greater threat to world than coronavirus (…) [climate change is] a threat that is greater to our species than any known virus” (Carrington Citation2020d). They were also employed to demonstrate the negative impact of COVID-19 on climate initiatives—“[c]oronavirus poses threat to climate action, says watchdog” and particularly clean energy research (Ambrose Citation2020a) and to demonstrate the positive impact of COVID-19 on the climate—“[measures taken by China in response to COVID-19] have wiped out a quarter or more of the country’s CO2 emissions within the four-week period when activity would normally have resumed after the Chinese new year” (Purdy Citation2020).

The overall infrequent use of war-related language in the analysed data is interesting considering that War metaphors have been shown to dominate the reporting of both climate change and COVID-19 when the two issues have been considered in isolation. A possible explanation is that War metaphors appeal to emotions (see e.g., Flusberg, Matlock, and Thibodeau Citation2018), but the relationship between climate change and COVID-19 is not an emotionally charged issue in the same way as the aetiology or treatment of an infectious disease are (e.g., “a virus attacking the body” and “the need to fight and defeat the virus”). This explanation is supported by findings that Twitter discussions around the hashtag #Covid-19 are dominated by War metaphors, but their use is limited to a very specific aspect of the pandemic – treatment (Wicke and Bolognesi Citation2020). Further, War metaphors are ideal for expressing certain and definitive outcomes such as “victory” or “defeat” (see e.g., Flusberg, Matlock, and Thibodeau Citation2018), but the possible effects of societal responses to COVID-19 on the climate are an uncertain mix of positives and negatives. The use of war-related language may thus have been deemed less appropriate for expressing the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19. Another possible explanation is that awareness of the critiques of War metaphors may have grown considerably, leading to avoidance.

Conclusion

Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, fears have been expressed that the heavy reporting of pandemic developments may cause climate change to slip from public attention and views have converged that the focus should be on the positive lessons of COVID-19 for addressing climate change. With this in mind, this paper analysed two news outlets—Guardian Online and Positive News—to identify examples of good practice in reporting the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 (from a solutions-angle). What makes Guardian Online and Positive News especially relevant to study is their commitment to climate change reporting and to solutions-oriented constructive journalism which aims to elaborate relations between issues. The focus of this study was on understanding the types of synergistic effects that were reported and how they were reported through metaphors—key tools for conceptualising complex issues.

News articles discussing the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 started to appear in March 2020 which overlaps with the announcement of the first lockdown in the UK and the coverage peaked in May 2020 when a conditional plan for lifting the lockdown restrictions was released. News articles from both Guardian Online and Positive News focused on the solutions-oriented synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 throughout the entire period analysed here. This is consistent with the similar solution-orientation at national and international level that our focus should be on how measures to contain COVID-19 may offer ways to address climate change (see e.g., Greenpeace European Unit Citation2020; Johnson Citation2020; OECD Citation2021; World Health Organization Citation2020b). The solution-orientation in reporting the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 is much to be expected in Positive News given the news magazine’s comprehensive commitment to constructive journalism that is solutions-oriented. The focus on solutions in Guardian Online is potentially more interesting, as none of the Guardian Online news articles identified and analysed in this study appeared in its constructive journalism column “The Upside”. This may suggest that “more traditional” forms of reporting still have an important role to play in helping to predict, imagine and create hopeful environments of the future.

The use of metaphors to report the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 peaked in May 2020, but a significant peak was also observed in April 2020 when it was stated that the lockdown announced a month earlier will be extended. Reporting the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 through metaphors was thus tied to key developments in the COVID-19 timeline. In those moments when important announcements regarding the COVID-19 pandemic were made and public attention to news reporting would have been high, the news articles analysed in this study maintained the public’s interest in climate change by elaborating the synergistic effects between the two issues through mainly Movement and Colour metaphors. In contrast, when the reporting of climate change and COVID-19 have been studied separately, researchers have observed reliance on War metaphors. Preference for Movement and Green metaphors over War metaphors can be interpreted as a positive practice. Movement metaphors are familiar, flexible and vivid while Green metaphors are closely associated with environmentalism and have positive connotations. The infrequent use of war-related language might be attributed to: the uncertainty surrounding the link between the two crises whereas War metaphors are particularly well-suited to express outcomes that are certain; the fact that the issue of synergistic effects is devoid of emotion and yet War metaphors are well-known for their emotional language; and/or increased awareness of the various critiques of War metaphors.

This study makes a significant contribution to understanding what synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 have been reported in two news outlets that have made public commitments to consistently report climate-related issues and which aim to offer constructive coverage that is both solutions-oriented and provides context by exploring relations between issues. The study focused on the use of metaphors within the instances of discussing synergistic effects, as metaphors are important communicative and cognitive tools. However, the study is not without its limitations. Future research might expand the analysis to longer timeframes. It would also be a fruitful direction to compare whether and how the synergistic effects of climate change and COVID-19 have been reported in other news outlets which have not expressed commitment to the practices of constructive journalism.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Guest Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their considerate comments and suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Metaphorical linguistic expressions are set out by underlining.

2 Initial capitals are used to label metaphors.

3 Conceptual metaphors are signalled using small capitals.

4 To browse MetaNet, go to https://metaphor.icsi.berkeley.edu/pub/en/index.php/Category:Frame

5 A final-year undergraduate student in linguistics and the media.

References

- Ahva, Laura, and Mikko Hautakangas. 2018. “Why Do We Suddenly Talk So Much About Constructiveness?” Journalism Practice 12 (6): 657–661. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1470474.

- Aitamurto, Tanja, and Anita Varma. 2018. “The Constructive Role of Journalism.” Journalism Practice 12 (6): 695–713. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1473041.

- Ambrose, Jillian. 2020a. “Coronavirus Poses Threat to Climate Action, says Watchdog.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/12/coronovirus-poses-threat-to-climate-action-says-watchdog.

- Ambrose, Jillian. 2020b. “Green Energy Could Drive Covid-19 Recovery with $100tn Boost.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/20/green-energy-could-drive-covid-19-recovery-international-renewable-energy-agency.

- Ambrose, Jillian, and Fiona Harvey. 2020. “Cop26 Climate Talks in Glasgow Postponed until 2021.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/01/uk-likely-to-postpone-cop26-un-climate-talks-glasgow-coronavirus.

- Anderson, Alison. 2009. “Media, Politics and Climate Change: Towards a New Research Agenda.” Sociology Compass 3: 166–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00188.x.

- Annas, George. 1995. “Reframing the Debate on Health Care Reform by Replacing our Metaphors.” New England Journal of Medicine 332 (11): 744–747.

- Atanasova, Dimitrinka, and Nelya Koteyko. 2017. “Metaphors in Guardian Online and Mail Online Opinion-page Content on Climate Change: War, Religion, and Politics.” Environmental Communication 11 (4): 452–469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2015.1024705.

- Baehr, Peter. 2006. “Susan Sontag, Battle Language and the Hong Kong SARS Outbreak of 2003.” Economy and Society 35 (1): 42–64.

- Bates, Benjamin R. 2020. “The (In)Appropriateness of the WAR Metaphor in Response to SARS-CoV-2: A Rapid Analysis of Donald J. Trump’s Rhetoric.” Frontiers in Communication 5 (50): 1–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00050.

- Bevitori, Cinzia. 2011. “‘Jumping on the Green Bandwagon’: The Discursive Construction of GREEN Across ‘old’ and ‘new’ Media Genres at the Intersection Between Corpora and Discourse”, Proceedings of the corpus linguistics conference 2011—discourse and corpus linguistics. Birmingham: University of Birmingham Press, 1–19.

- Carrington, Damian. 2020a. “Coronavirus: ‘Nature is Sending Us a Message’, says UN Environment Chief.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/25/coronavirus-nature-is-sending-us-a-message-says-un-environment-chief.

- Carrington, Damian. 2020b. “Protecting Nature is Vital to Escape ‘era of pandemics’ – Report.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/oct/29/protecting-nature-vital-pandemics-report-outbreaks-wild.

- Carrington, Damian. 2020c. “Coronavirus UK Lockdown Causes Big Drop in Air Pollution.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/27/coronavirus-uk-lockdown-big-drop-air-pollution.

- Carrington, Damian. 2020d. “Climate Emergency: Global Action is ‘way off track’ says UN Head.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/10/climate-emergency-global-action-way-off-track-says-un-head-coronavirus.

- Chapman, Connor M., and DeMond Shondell Miller. 2020. “From Metaphor to Militarized Response: The Social Implications of ‘we are at war with COVID-19’ – Crisis, Disasters, and Pandemics yet to Come.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 40 (9/10): 1107–1124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-05-2020-0163.

- Charteris-Black, Jonathan. 2004. Corpus Approaches to Critical Metaphor Analysis. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Climate Visuals. 2020. Covering the Climate Crisis from a Solution Lens.” Climate Visuals, https://climatevisuals.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/UK-Workshop_-Covering-the-Climate-Crisis-from-a-Solutions-Lens.pdf.

- Cohen, Maurie J. 2011. “Is the UK Preparing for ‘War’? Military Metaphors, Personal Carbon Allowances, and Consumption Rationing in Historical Perspective.” Climatic Change 104: 199–222.

- Dobrin, Sidney. 2010. “Through Green Eyes: Complex Visual Culture and Post Literacy.” Environmental Education Research 16 (3-4): 265–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504621003715585.

- Ebi, Kristie L., Elisabet Lindgren, Jonathan E. Suk, and Jan C Semenza. 2013. “Adaptation to the Infectious Disease Impacts of Climate Change.” Climatic Change 118: 355–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0648-5.

- European Commission. 2020. “COVID-19 and Green Recovery: How Member States Integrate Sustainable Energy Investments into their Recovery Plans.” https://ec.europa.eu/easme/en/news/covid-19-and-green-recovery-how-member-states-integrate-sustainable-energy-investments-their.

- European Space Agency. 2020. “Seen from Space: COVID-19 and the Environment.” https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-5P.

- Feindt, Peter, and Richard Cowell. 2010. “The Recession, Environmental Policy and Ecological Modernization – What’s New About the Green New Deal?” International Planning Studies 15 (3): 191–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2010.509474.

- Feldman, Lauren, Sol Hart, and Tijana Milosevic. 2017. “Polarizing News? “Representations of Threat and Efficacy in Leading US Newspapers’.” coverage of Climate Change.” Public Understanding of Science 26 (4): 481–497.

- Flusberg, Stephen J., Teenie Matlock, and Paul H Thibodeau. 2018. “War Metaphors in Public Discourse.” Metaphor and Symbol 33 (1): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2018.1407992.

- Greenpeace European Unit. 2020. “Over 1 Million People Call for Green Recovery from COVID-19.” https://www.greenpeace.org/eu-unit/issues/democracy-europe/3886/over-1-million-people-call-for-green-recovery-from-covid-19/.

- Gyldensted, Cathrine. 2015. From Mirrors to Movers: Five Elements of Positive Psychology in Constructive Journalism. Lexington, KY: Ggroup Publishing.

- Haagerup, Ulrik. 2017. Constructive News (2nd ed.). Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Haines, Gavin. 2020a. “Cities Have Been Invaded By Cars. Now They are Being Liberated.” https://www.positive.news/economics/cities-have-been-invaded-by-cars-now-they-are-being-liberated.

- Haines, Gavin. 2020b. “‘Once-in-a-lifetime Opportunity’: The Five-point Plan for Achieving Net Zero.” https://www.positive.news/environment/the-five-point-plan-for-achieving-net-zero/.

- Haines, Gavin. 2020c. “Lockdown and Sunny Weather Help UK Set New Record for Coal-Free Power.” https://www.positive.news/environment/uk-sets-new-record-for-coal-free-power/.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020a. “World is Running Out of Time on Climate, experts Warn.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/nov/09/world-is-running-out-of-time-on-climate-experts-warn.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020b. “Rebound in Carbon Emissions Expected in 2021 After Fall Caused by Covid.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/11/rebound-in-carbon-emissions-expected-in-2021-after-fall-caused-by-covid.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020c. “Vital Cop26 Climate Talks Could Be Derailed by Coronavirus.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/02/vital-cop26-climate-talks-could-be-derailed-by-coronavirus.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020d. “Leading UK Charities Urge PM to Demand a Green Covid-19 Recovery.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/15/leading-uk-charities-urge-pm-seek-green-recovery-covid-19.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020e. “Human Progress at Stake in Post-Covid Choices, says UN report.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/15/human-progress-at-stake-in-post-covid-choices-says-un-report.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020f. “UN Chief: Don’t Use Taxpayer Money to Save Polluting Industries.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/28/un-chief-dont-use-taxpayer-money-to-save-polluting-industries.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020g. “Cop26 Climate Talks in Glasgow Will be Delayed by a Year, UN confirms.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/may/28/cop26-climate-talks-in-glasgow-will-be-delayed-by-a-year-un-confirms.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020h. “Covid-19 Economic Rescue Plans must be Green, say Environmentalists.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/24/covid-19-economic-rescue-plans-must-be-green-say-environmentalists.

- Harvey, Fiona. 2020i. Climate Crisis Must Not Be Overshadowed by Covid, Johnson to Tell UN.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/sep/23/climate-crisis-must-not-be-overshadowed-by-covid-johnson-to-tell-un.

- Hautakangas, Mikko, and Laura Ahva. 2018. “Introducing a New Form of Socially Responsible Journalism.” Journalism Practice 12 (6): 730–746. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1470473.

- Hertsgaard, Mark, and Kyle Pope. 2019. “Transforming the Media’s Coverage of the Climate Crisis.” https://www.cjr.org/watchdog/climate-crisis-media.php.

- Howard, Emma. 2015. “Keep It In the Ground Campaign: Six Things We’ve Learned.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/keep-it-in-the-ground-blog/2015/mar/25/keep-it-in-the-ground-campaign-six-things-weve-learned.

- Institute for Government. 2021. “Timeline of UK Coronavirus Lockdowns, March 2020 to March 2021.” https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/timeline-lockdown-web.pdf.

- Isaacs, David, and Anne Priesz. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Metaphor of War.” Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15164

- Johnson, Boris. 2020. “Boris Johnson: Now is the Time to Plan our Green Recovery.” https://www.ft.com/content/6c112691-fa2f-491a-85b2-b03fc2e38a30.

- Karlberg, Michael, and Leslie Buell. 2005. “Deconstructing the ‘War of all Against All’: The Prevalence and Implications of War Metaphors and Other Adversarial News Schema in TIME, Newsweek, and Maclean’s.” Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies 12 (1): 22–39.

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2018. “Metaphor in Media Language and Cognition: A Perspective from Conceptual Metaphor Theory.” Lege Artis 3 (1): 124–141. doi: https://doi.org/10.2478/lart-2018-0004.

- Kövecses, Zoltán. 2010. Metaphor a Practical Introduction (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Lule, Jack. 2004. “War and its Metaphors: News Language and the Prelude to War in Iraq, 2003.” Journalism Studies 5 (2): 179–190.

- Matlock, Teenie. 2013. “Motion Metaphors in Political Races.” In Language and the Creative Mind, edited by Michael Borkent, Barbara Dancygier, and Jennifer Hinnell, 193–201. Stanford: CSLI.

- McGinty, Emma E, Elizabeth Stone, M. Kennedy-Hendricks, Sanders Alene, Beacham Kaylynn Alexa, and Barry L. Colleen. 2019. “US News Media Coverage of Solutions to the Opioid Crisis, 2013–2017.” Preventive Medicine, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105771.

- McIntyre, Karen. 2020. “‘Tell Me Something Good’: Testing the Longitudinal Effects of Constructive News Using the Google Assistant.” Electronic News 14 (1): 37–54.

- McIntyre, Karen, and Cathrine Gyldensted. 2017. “Constructive journalism: an introduction and practical guide for applying positive psychology techniques to news production.” Journal of Media Innovations 4 (2): 20–34.

- McIntyre, Karen, and Cathrine Gyldensted. 2018. “Positive Psychology as a Theoretical Foundation for Constructive Journalism.” Journalism Practice 12 (6): 662–678.

- Meier, Klaus. 2018. “How Does the Audience Respond to Constructive Journalism?” Journalism Practice 12 (6): 764–780. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1470472.

- Milman, Oliver. 2020. “Pandemic Side-effects Offer Glimpse of Alternative Future on Earth Day 2020.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/22/environment-pandemic-side-effects-earth-day-coronavirus.

- Musolff, Andreas. 2006. “Metaphor Scenarios in Public Discourse.” Metaphor and Symbol 21 (1): 23–38.

- Musolff, Andreas. 2020. “Churchillian War-spirit vs. Bazooka-deployment: British and German Metaphors for the COVID-19 Pandemic as a War.” https://frias.hypotheses.org/285.

- Nerlich, Brigitte. 2010. “Breakthroughs and Disasters: The Politics and Ethics of Metaphor Use in the Media.” In Cognitive Foundations of Linguistic Usage Patterns: Empirical Studies, edited by Hans-Jörg Schmid, and Susanne Handl, 63–88. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Nerlich, Brigitte. 2012. “‘Low Carbon’ Metals, Markets and Metaphors: The Creation of Economic Expectations About Climate Change Mitigation.” Climatic Change 110: 31–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0055-3.

- Nofri, Sara. 2011. Cultures of Environmental Communication: A Multilingual Comparison. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

- OECD. 2021. “The OECD Green Recovery Database.” https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-oecd-green-recovery-database-47ae0f0d/.

- Panzeri, Francesca, Simona Di Paola, and Filippo Domaneschi. 2021. “Does the COVID-19 War Metaphor Influence Reasoning?” PLOS One. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250651

- Pfrimer, Matheus Hoffmann, and Ricardo Barbosa Jr. 2020. “Brazil’s War on COVID-19: Crisis, Not Conflict—Doctors, Not Generals.” Dialogues in Human Geography 10 (2): 137–140. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620924880.

- Pilkington, Ed. 2020. Environmental Groups Hail Covid Relief Bill – But More Needs to be Done.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/24/environmental-groups-covid-relief-bill-biden-trump.

- Pragglejaz Group. 2007. “MIP: A Method for Identifying Metaphorically Used Words in Discourse.” Metaphor & Symbol 22 (1): 1–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10926480709336752.

- Purdy, Lucy. 2018. “Positive News Hits the High Street as ‘constructive journalism’ Spreads.” https://www.positive.news/society/media/positive-news-hits-the-high-street-as-constructive-journalism-spreads/.

- Purdy, Lucy. 2020. “Coronavirus Could Cause Fall in Global CO2 Emissions, say Analysts.” https://www.positive.news/environment/coronavirus-could-cause-fall-in-global-co2-emissions-say-analysts/.

- Ravilious, Kate. 2020. “Drop in Pollution May Bring Hotter Weather and Heavier Monsoons.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/13/drop-in-pollution-may-bring-hotter-weather-and-heavier-monsoons.

- Rawnsley, Jessica, and Patrick Barkham. 2020. “Chris Packham Begins Legal Case to Halt HS2 Amid Coronavirus Crisis.” https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/mar/27/chris-packham-begins-legal-case-to-halt-hs2-amid-coronavirus-crisis.

- Rice-Oxley, Mark. 2021. “How to Edit ‘A Stream’ of Constructive Stories.” The Constructive Institute, https://constructiveinstitute.org/how/contributions/how-to-edit-a-stream-of-constructive-stories/.

- Rodríguez, Redondo, Ana Laura, and Silivia Molina Plaza. 2007. “Colours we Live by?: Red and Green Metaphors in English and Spanish.” Culture, Language and Representation 5: 177–193.

- Semino, Elena. 2021. “‘Not Soldiers but Fire-Fighters’—Metaphors and Covid-19.” Health Communication 36 (1): 50–58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1844989.

- Shaw, Christopher, and Brigitte Nerlich. 2015. “Metaphor as a Mechanism of Global Climate Change Governance: A Study of International Policies, 1992–2012.” Ecological Economics 109: 34–40. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.11.001.

- Shuman, Emily K. 2010. “Global Climate Change and Infectious Diseases.” The New England Journal of Medicine 362: 1061–1063. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0912931.

- Slawson, Nicola. 2020. “‘Create Green Post-Covid Recovery’ Urges UK Industry Body.” https://www.positive.news/economics/green-recovery-cbi-business.

- Sontag, Susan. 1989. Illness as Metaphor: AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Picador/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Swinburn, Boyd, et al. 2019. “The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission Report.” The Lancet Commissions 393 (10173): 791–846. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8.

- Taylor, Matthew. 2020a. “Greta Thunberg Says it’s ‘extremely likely’ She Has Had Coronavirus.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/greta-thunberg-says-its-extremely-likely-she-has-had-coronavirus.

- Taylor, Charlotte, and Jasmin Kidgell. 2021. “Flu-like Pandemics and Metaphor Pre-Covid: A Corpus Investigation.” Discourse, Context & Media. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100503

- The Lancet. 2020. “Climate and COVID-19: Converging Crises.” The Lancet 397 (10269): 71. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32579-4.

- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2017. “Climate Change: The Role of the Infectious Disease Community.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 17 (12): 1219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30645-X.

- Thibodeau, Paul H., Rose K. Hendricks, and Lera Boroditsky. 2017. “How Linguistic Metaphor Scaffolds Reasoning.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21 (11): 852–863. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.07.001.

- Tolan, Sandy. 2007. “Coverage of Climate Change in Chinese Media.” https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6248686.pdf.

- Tomlinson, John. 2007. The Culture of Speed: The Coming of Immediacy. London: Sage.

- UN News. 2020. “Key COP26 Climate Summit Postponed to ‘safeguard lives’.” https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1060902.

- Väliverronen, Esa, and Iina Hellsten. 2002. “From 'Burning Library' to 'Green Medicine': The Role of Metaphors in Communicating Biodiversity.” Science Communication 24 (2): 229–245.

- Wallis, Patrick, and Brigitte Nerlich. 2005. “Disease Metaphors in New Epidemics: The UK Media Framing of the 2003 SARS Epidemic.” Social Science and Medicine 60: 2629–2639.

- Washer, Peter, and Helene Joffe. 2006. “The Hospital ‘Superbug’: Social Representations of MRSA.” Social Science and Medicine 63 (8): 2141–2152.

- Watts, Nick, 2019. “The 2019 Report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Ensuring That the Health of a Child Born Today is not Defined by a Changing Climate.” The Lancet 394 (10211): 1836–1878. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6.

- Watts, Jonathan. 2020a. “Climate Crisis: In Coronavirus Lockdown, Nature Bounces Back – But for How Long?” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/09/climate-crisis-amid-coronavirus-lockdown-nature-bounces-back-but-for-how-long.

- Watts, Jonathan. 2020b. “Earth Day: Greta Thunberg calls for ‘new path’ after Pandemic.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/22/earth-day-greta-thunberg-calls-for-new-path-after-pandemic.

- Watts, Jonathan, and Jillian Ambrose. 2020. “Coal Industry Will Never Recover After Coronavirus Pandemic, say experts.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/may/17/coal-industry-will-never-recover-after-coronavirus-pandemic-say-experts.

- Wicke, Philipp, and Marianna M. Bolognesi. 2020. “Framing COVID-19: How We Conceptualize and Discuss the Pandemic on Twitter” https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.06986.

- Wildlife Conservation Society (2008, October 8). “Deadly Dozen’ Reports Diseases Worsened By Climate Change.” ScienceDaily. Accessed May 13 2020. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/10/081007073928.htm.

- Williams, Lindsay. 2018. “Metaphors for Persuasion.” https://themediacoach.co.uk/metaphors-for-persuasion/.

- World Health Organization. 2020a. “Climate Change and Infectious Diseases.” https://www.who.int/globalchange/summary/en/index5.html.

- World Health Organization. 2020b. “Q&A: Climate Change and COVID-19.” https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-on-climate-change-and-covid-19.

- World Health Organization. 2020c. “WHO Timeline—COVID-19.” https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19.

- Wu, Xiaoxu, Yongmei Lu, Sen Zhou, Lifan Chen, and Bing Xu. 2016. “Impact of Climate Change on Human Infectious Diseases: Empirical Evidence and Human Adaptation.” Environment International 86: 14–23.

- Yurk, Valerie. 2020. “Coronavirus Pandemic Prompts Record Drop in Global Emissions, study finds.” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jul/10/coronavirus-global-emissions-study.

- Zambrano-Monserrate, Manuel A., María Alejandra Ruano, and Luis Sanchez-Alcalde. 2020. “Indirect Effects of COVID-19 on the Environment.” Science of the Total Environment 728: 1–4.

- Zinken, J., I. Hellsten, and Brigitte Nerlich. 2008. “Discourse Metaphors.” In Body, Language and Mind: Vol. 2. Sociocultural Situatedness, edited by R. M. Frank, R. Dirven, T. Ziemke, and E. Bernárdez, 363–386. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.