ABSTRACT

Understanding the expectations, needs, and wants of young audiences, as well as inviting them to incorporate their experiences and perspectives into media production, are crucial tasks for today’s media producers. Drawing upon qualitative research in which more than seventy children eight to thirteen years old participated, this paper illuminates children’s experiences with radio broadcasts and the suggestions they make for improving them. To explore children’s media preferences and experiences, in the spring of 2019 we conducted thirteen focus groups that incorporated creative techniques and stimuli at four elementary schools located in geographically and demographically different areas of the Czech Republic. The research discovered that the radio was a part of children’s complex media experience. In some cases the children linked listening to it with the time they spent with their parents and grandparents. Even though they did not consider the radio their favourite medium, when they were invited to create their own radio programmes and content the children made a number of valuable suggestions for making radio more accessible and relevant to them. We argue that children should be considered as partners and invited to participate in a creative dialogue with media content creators.

Introduction

Radio has managed to remain a relevant media platform despite the increasingly complex and competitive media environment as a result of, among others, the proliferation of new communication technologies and platforms. This is partly because of radio’s capacity to adapt to dynamic changes as well as its accessibility to diverse individuals and communities across the globe. Understanding who listens to radio, why and how they do so, and radio’s sociocultural role, remains central to defining its future potential and finding innovative ways in which it can fulfil that potential. Children can be seen as central to such continuous social and individual relevance as they represent not only the current, but also the future audience. Nevertheless, the research into children’s experience of radio and their attitudes toward it is limited. In part, this may be because the child audience is of little interest to broadcasters from an economic point of view (Balsebre et al. Citation2011) and/or because of a general belief that children today in developed countries simply do not listen to the radio.

These and other assumptions about children’s media preferences and habits heavily influence the field of media and journalism. This paper is in agreement with Woodfall and Zezulkova (Citation2016), who believe that today’s media and journalism theory as well as practice ought to be informed by up-to-date qualitative studies of children’s media experiences. While the rich international academic and market research is being conducted on children’s and youth’s experience with diverse kinds of media, the research into children’s relationship with the radio—considered an “old” medium—is limited. As Buckingham (Citation2015) points out, “Media Studies have often suffered from a compulsive fascination with the new, [which] is particularly the case when we talk about children and young people”.

We argue that researching children’s experiences with, and ideas about radio, the so-called “old” medium, is still relevant today. Moreover, we suggest that it can greatly contribute to the understanding of children's dialogic and holistic lived media engagement (Woodfall and Zezulkova Citation2016). By dialogic and holistic, we refer to the increasing body of research illustrating how children “move skilfully across mode, medium and form” while developing strong “relationships between the texts children read, play and engage with and those they make, play and tell” (Parry and Taylor Citation2018, 103). Although Woodfall and Zezulkova (Citation2016, 98) warn that due to this “focusing on only one discreet media utterance (like television for example) can be said to become deeply problematic”, we suggest here that research focused on a single medium, such as radio, may also enrich the understanding of children’s overall media behaviours, attitudes, preferences and expectations, which in turn, will enrich the practice of journalism.

This paper aims to contribute to such an understanding and its practical application by drawing upon the results of the participatory qualitative applied social research of children’s radio experience. The study was conducted with seventy-three children, eight to thirteen years old, living in the Czech Republic. Although the research was country specific, it has international relevance as the Czech radio market mirrors the Western European market, both in the technologies that are used and in the kinds of radio programmes broadcast to children. The literature review section explores the role and impact of online and digital developments in radio, first generally, and then, more specifically regarding children and youth’s experience with it. The methodology section describes the research design, participants, and data analysis and interpretation, which is then followed by the research findings. There we illustrate, firstly, how the artificial boundaries between educational and entertaining roles of radio, as well as the affordances by diverse media texts, forms, and platforms, were all blurred in the children’s practical experience. Secondly, we look closer at the children’s radio content and format expectations and suggestions, while drawing a line between child-focused and child-appropriate content and execution relevance and quality. Based on this, we ultimately argue that knowledge and understanding of children’s real-life radio experience is essential not only to the future of radio broadcasting, but the overall understanding of children’s holistic and dialogic media experience. Furthermore, we suggest that listening to their proposed changes would be greatly valuable as a guide to the immediate and long-term practice, development, and innovation of journalism.

Radio Remediation

We align ourselves with Bolter and Grusin’s concept of remediation (Citation2000), which suggests that “new” and “old” media constantly influence each other when establishing their position at first and then continue evolving in order to remain relevant. For example, radio broadcasting influenced the early days of television. Then TV set the ground rules for online video channels such as YouTube, and now the Internet greatly influences today’s radio content production (e.g., by radio’s incorporation of user-generated content (Zelenkauskaite Citation2018) or with a specific production of increasingly popular formats, such as podcasts, intended primarily for online distribution). This is also in line with the observations of McClung, Pompper, and Kinnally (Citation2007) on how young teens understand the functions of radio as a media platform. When looking into the position the radio took within the wide array of media teens interacted with, McClung, Pompper, and Kinnally (Citation2007, 105) discovered a phenomenon they named “functional reorganisation”. In their research, they found that the younger audience did not simply abandon platforms that had become obsolete. Instead, the platforms became interchangeable with the others and were adapted to new and evolving user demands.

The remediation offered by digital innovations can further partly free the so-called traditional media, including radio, by opening them up to content migration with the use of new channels (Fetveit Citation2007). As Fetveit explains (Citation2007, 70) this means that media forms and platforms “do not so much disappear as they reappear, through the acts of remediation and recirculation” leading to more of a “proliferation of media than to their unification” (ibid., 57). However, media tend to converge and the distinctions between them are blurring (Fetveit Citation2007). Therefore, we do not perceive radio as an old medium overwhelmed by the new media, which would be inclining to the traditional dichotomy between the techno-optimism and techno-pessimism described by Moyo (Citation2013) or Zelenkauskaite (Citation2017). Instead, we lean towards the constructivist perspective brought about by the critical theory of convergence (Moyo Citation2013, 212) through which radio creates “spaces for feedback, participation, and new civic vernaculars”. Moyo specifies that “multiple platforms of websites, social media, podcasts, and mobile streaming are, in principle, making radio vertically and horizontally pervasive within and across social classes” (ibid.). Still, as Moyo (Citation2013) and Zelenkauskaite (Citation2017) acknowledge, audience participation is invitational and greatly influenced by the producers’ strategic choices and decisions.

Together with technological developments and their impacts, it is important to also pay attention to the social aspects of changing media experiences. Since its beginnings, radio has “permitted the forgoing of new bonds among family and friends as they listened together to information and entertainment that previously was inaccessible in such a format,” (MacLennan Citation2013, 324). The current situation is very similar, with radio, or any media, content connecting people. However, with a more global reach, the interests can be shared by people across national and cultural borders. In addition, the spread of social and mobile media together with the fragmentation of the audience's attention across formats and platforms has led to significantly more individualised and participatory media engagements (Zelenkauskaite Citation2017).

The potential to improve audience participation has been a topic of media development since the early days of radio broadcasting which, as a new technology, aroused expectations that were not that different from those connected to online and digital media. Radio listeners were considered more active than the previous newspaper readers, as the radio “provided an antidote to isolation, practical information, and entertainment to share beyond the act of listening,” (MacLennan Citation2013, 312). However, a typical interactive radio genre, talk back shows with live phone calls (Zelenkauskaite Citation2017), has gradually disappeared from broadcasting. Their participatory potential was limited to audience reactions through digital media. On the other hand, digital possibilities opened the door to new genres and formats with interactive potential such as podcasts.

It is important to be attentive to these technological and social changes and developments, because otherwise radio, as all other media, could gradually lose its audience in general, and its young audience in particular. For instance, Gutierrez, Ribes, and Monclús (Citation2011), mapping the online activity of young people (14–24 years old) connected to radio consumption, discovered that a quarter of the youngsters “expressly showed determined disaffection for radio as media,” (Gutierrez, Ribes, and Monclús Citation2011, 305) and on average, the youth spent only around 15 min daily with radio broadcasting without paying any greater attention to its content. The following section will thus look specifically at research about children and youth.

Producing Radio for and with Children

Media produced for children is highly influenced by adults’ perceptions of children and childhood (Woodfall and Zezulkova Citation2016). In media and journalism practice, the discourses and actions performed by adults in the processes of children’s media production often ascribe a certain “virtuality” to children, as passive objects who “remain largely silent” (Bignell Citation2002, 127). Bignell (Citation2002, 131) further points out that perceptions of the child as a passive consumer of media are linked to discourses that assign to media the role of an audience pleaser, unconcerned with providing an “authentic cultural experience” or with actively engaging the audience in its “cultural” production. Children’s unique media experiences are usually far from the focus of creative processes, nor are they often invited to co-shape their culture through being actively involved in journalism and media practices (Woodfall and Zezulkova Citation2016).

Looking into how radio views its young audience, Balsebre et al. (Citation2011) found that children’s programmes are marginalised in radio broadcasting as a result of programmers’ focus on the news. The authors concluded that in Spain, both programmers and advertising strategists ignored children as an audience. Nevertheless, they found that children still had the potential to be active listeners. Balsebre and his colleagues (Citation2011), however, focused primarily on whether it was appropriate for the content creators to marginalise children as potential media consumers, leaving aside the question of whether children should take on the role of content creators themselves.

To use media to its full potential, journalists and media producers need to acknowledge that children actively interact with and relate to the content they consume as well as share and produce. According to Jenkins (Citation2006, 3), rather than “talking about media producers and consumers as occupying separate roles, we might see them as participants who interact with each other.” Indeed, there is an important body of work that focuses on how radio broadcasters actively engage with young audiences. From pirate radio stations that challenge norms of acceptability (Theodosiadou Citation2010), to community radio supported by local authorities, these platforms represent practical examples which illustrate the nature of the relationship between radio and its young listeners, particularly those from economically or linguistically marginalised populations.

For instance, Wagg (Citation2004) looked at how the opportunity to participate in producing a radio show provides young teens with a space for raising their voices that may be lacking in their school or their family setting. He observes that “the air space of the radio medium affirms a worthy sense of self in the power derived from the vocalisation of personal words, ideas, thoughts and opinions” (Wagg Citation2004, 275). Another researcher, Marchi (Citation2009), analysed a project for encouraging at-risk young people to become involved in the creative process at a local radio station. The youths discussed important political and social issues in the studio. Along with introducing young teens to the technical aspects of broadcasting, the project encouraged them to embrace their roles as content producers and bring their message to disenfranchised members of their community.

A potent example of the power of radio is provided also by Bosch (Citation2007). Bosch focused on youths’ engagement with media in South Africa and analysed the Children’s Radio Education Workshop project in Cape Town. The workshop, organised by Bosch himself, aimed at improving youth’s understanding of media by introducing them to the main aspects of radio broadcasting. The children were included in the process of creating radio content, which revealed a greater capacity in them than was expected:

“On the surface then, the Bush Tots program is about training children to use radio equipment and allowing them to broadcast their discussions. But on another level, the program demonstrates the potential to engage children at quite a young and crucial age about broader issues” (Bosch Citation2007, 281).

The role of community radio in demystifying broadcasting for young audiences and for encouraging their direct involvement in the creative process was researched by Wilkinson (Citation2015). Her contribution also focused on the social role of radio, both in offering youth a platform and in encouraging diverse participation and social inclusion. The author underlined the unique service provided by community, as opposed to commercial radio. The community aspect does not imply the presence of any particular social group in the audience, but it does give the young audience an opportunity to own a means of communication, control it, and participate in creating content.

Wilkinson’s later work analysed how involvement in radio content production at a youth-led community radio station allowed teens in Knowsley, Liverpool, UK to “locate themselves more fully in the social and cultural fabric” of their community (Wilkinson Citation2018, 4). The studio became a safe space where creators from different backgrounds forged relationships across their differences. Although studying the role of radio within specific communities is a fruitful way to find out more about how the relationship between radio and its young audience is formed, the afore-mentioned research is context-based and insufficient for a thorough understanding of that relationship at a more general level. Moreover, the existing research mostly focuses on youth rather than younger children.

The next section highlights research methodology aimed at addressing several of the research gaps previously mentioned by focusing on younger children's radio experience (1) in the context of other media, (2) with reference to more traditional formats and content such as news, as well as (3) a radio format and content remediated as a response to the recent technological and social developments, and (4) in its participatory nature allowing children to share their suggestions for radio broadcasting improvements.

Research Approach and Design

The paper builds upon the analysis of qualitative data gathered for a larger study, The Multicultural Life and Education of Child Prosumers (2018–2021) funded by an independent applied science foundation. The paper draws solely upon the findings about the children’s attitudes towards and expectations of radio. For the findings about media, diversity and education see Supa et al. (Citation2021) and about diversity and normalcy in children's peer culture see Supa, Sokup, and Nainová (Citationforthcoming).

Children’s radio experience was explored specifically for the public service broadcaster Czech Radio, which was one of the project's so-called “Application Guarantees”, officially agreeing to implement a practical application of the research results. The research and the outcomes presented here were thus developed in close collaboration between scholars and media professionals as suggested by Lemish (Citation2021). As such, this research addresses the criticism of media research with children which “is very slow to arrive in the hands of professionals who are creating content for children, [and that a]t the same time (…) is missing so much by not learning from the immense experience of professionals who can sharpen our questions and understanding of children as well as bring very different perspectives to our scholarly endeavours” (ibid., 151).

Research Methodology and Design

The research applied a hermeneutic phenomenological participatory research approach drawing primarily upon the work of Van Manen (Citation1990). His holistic understanding of human experience and a call for research that “reintegrates part and whole, the contingent and the essential, value and desire” (Van Manen Citation1990, 8). In order to explore the phenomena of media and diversity in the whole child’s lifeworlds, we used creative participatory research methods and techniques.

The findings on which this paper draws were generated through thirteen focus groups (FGs) conducted in 2019. The design of the FGs was intended to facilitate active participation by the children. It included a number of creative activities because, as Darbyshire, Schiller, and MacDougall (Citation2005) suggest, these methods help the child participants to engage, as well as the researchers to recognise children as the experts on their own worlds. The FGs were prepared and executed through the adoption of Gibson’s (Citation2007) theoretically sound, practical recommendations for organising FGs in order “to achieve two important outcomes, successful data collection and a positive experience for participants” (473). For instance, we gave careful consideration to ethical issues and factors such as the size of the groups and the age of the participants, the design, location and environment for the FGs, and the moderators’ preparations for them.

The average duration of the focus groups was 45 min. The FGs were divided into a number of activities and this paper draws upon three of them; (1) platform ranking, (2) radio poster making, and (3) watching and listening media extracts. For platform ranking, the children were shown several paper cards with images of a TV, a radio, a smartphone, a computer, and a tablet. They discussed each medium separately at first and then ranked them in importance and their preference. Because the radio was most commonly marked as the least important medium, the next activity asked the children to imagine a radio station that they would actually listen to and to create a poster promoting such a station.

The second activity, poster-making, was similar to making a collage: the children could draw, write, and cut out and paste pictures and texts from various magazines onto A2-size coloured paper. Altogether, the children made 51 posters individually and in groups. They themselves decided how to create the posters and with whom to do so. Visual and creative methods, however, may not provide an easy, transparent way to decode the reflections of children’s realities, beliefs, and experiences (Buckingham Citation2009). The majority of such research suffers from uncritical celebration of representation and empowerment and leads to simplified research results (Piper and Frankham Citation2007; Buckingham Citation2009). In order to address this limitation, the participants in this study were encouraged to describe, explain, and discuss their posters with the researchers, as well as with other children participating in their FGs. Following this, the combination of “a range of linguistic and non-linguistic representations [allowed us] to articulate authentic lived experiences” of the participating children in a complex and critical manner (Gerstenblatt Citation2013, 294).

The third activity of the focus groups, and the last upon which this paper is based, involved playing two recordings to the children, both produced and given to the researchers by Czech Radio. After listening to the news and watching the YouTube video, the participating children evaluated the quality of the content as well as how interesting and relevant it was to them. First was an audio recording of a children's radio news session. The news segment was a one-minute-long recording narrated by a male moderator (Radio Junior Citation2019a). It included several short news stories about events happening in the Czech Republic, including a new-born animal at a zoo, a concert in the Prague subway, and a weather forecast with music playing in the background. By including news in our focus groups, we aimed to contribute to the still limited number of studies concerning children’s relationship to the news (Carter Citation2013), even though news is believed to be vital to children’s immediate as well as future lives, learning and citizenship (Mihailidis Citation2014; Carter, Steemers, and Davies Citation2021).

The second recording was a YouTube video created by the Radio in cooperation with a Czech influencer who is known among the Czech children. The YouTube video was six minutes long and had two moderators, the influencer and a young boy of elementary school age (Radio Junior Citation2019b). The moderators playfully reviewed three children’s books, but due to the focus groups’ time limitations, only the first two minutes of a review of Tracy’s Tiger (William Saroyan) was played. The video serves as an example of possible radio remediation with a young audience in mind, because YouTube and YouTubers represent one of the most popular social media, or in fact any media, engagements among children and youth (Zimmermann, Noll, and Gräßer Citation2020).

Research Participants

The focus groups were carried out in four public elementary schools across the Czech Republic. The research team had previously met in person with the individual headmasters. Upon agreeing to take part in the research, the school management and teachers selected a required number of diverse (in terms of gender, age, sociodemographics, and school performance) children and delivered to their parents informed consent documents provided by the researchers. These were then returned signed before the FGs took place. The researchers did not encounter any issues in gaining access to the schools nor to the individual children. The research had strictly followed a number of internal and external ethical guidelines (see, e.g., Graham et al. Citation2013) and it was granted approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Charles University.

In total, 73 children (39 girls, 34 boys) took part in the FGs. These were organised into groups of lower (8, 9, and 10 years of age) and upper (11, 12, and 13 years of age) elementary school students. Usually, three FGs were conducted per visit. The child participants were repeatedly asked about their oral consent and descent during the FGs. Even though our research design and approach to children could be seen as “child-led” and “child-friendly”, we have been well aware of, and continuously try to address, the tension between designing and carrying out “child-appropriate” research and at the same time treating children as equals who should not be paternalised (Daelman, De Schauwer, and Van Hove Citation2020; Thomas Citation2021). Among other precautionary measures taken, each focus group was moderated by an experienced researcher and a well-trained student researcher, who took turns leading the FGs. These research teams held meetings in between the school visits, reflecting upon their research experience and providing each other with feedback on interactions with the children. This increased not only the quality of research interventions, but also their consistency.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The FGs were video and voice recorded and then transcribed, anonymised (the 73 participants were given codes P1 through P73) and uploaded to Atlas.ti as textual and audio-visual materials. The data were then thematically analysed by all team members using open-coding and multimodal techniques (Jewitt Citation2014). The hermeneutic circle of reading, writing, re-reading, and re-writing played an important role in the process of analysis and interpretation. These processes, however, were also intuitive and empathetic. The reflective awareness had been exercised through repeated team meetings in which the original codes, categories and themes were jointly developed and re-developed. Following Van Manen (Citation1990), our thematic analysis was based on openness and a desire to make sense through the process of insightful invention, discovery, and disclosure. The following section introduces the two main themes of the research that were selected for the purposes of this paper. The direct quotations from the participating children were translated from Czech to English by the authors.

Research Findings

Radio as Part of Children’s Complex Media Experience

Radio was part of a complex media experience for children, even though it offered the children distinct ways of engagement when compared to some of the other media. Radio was characterised by the predominantly more cross-generational and adult-led media experience, which made radio unique and different. On the other hand, the children wished that the radio shared some characteristics, such as multimedia content and personalised content, with the other media they engaged with on a more regular basis. Furthermore, the borders between the different types of media were blurred in the children’s media experience. They expected their radio programmes to be connected to their favourite books, TV shows, popular culture, and so on. This desire illustrates the importance of understanding how children use each individual medium, including radio, and their attitudes towards them in the context of their complex, multifaceted experience of different media. The following paragraphs illustrate this finding further through the use of the children's quotes and posters.

The different social contexts in which individual media platforms are used became apparent when the cards with illustrations of a TV, a radio, a smartphone, a computer, and a tablet were discussed. The smartphone, the computer, and the tablet, which had access to the Internet, were mostly used by children on their own. “What I like the most about the computer is that I can play my favourite music on it and breakdance,” said participant P55 (boy, 9 years). Participant P37 (girl, 10 years) had a similar experience: “I enjoy watching fairy-tales on the tablet when we travel somewhere far away.” The participants used smartphones to access social media, even though legally they were not old enough to have a social media account.

The participants watched television alone or with family members. The radio was mostly listened to by the children’s adult family members. When the children listened to it, they listened together with other family members. Asked where they usually listened to the radio, the children often said that it was in their grandparents’ homes: “upstairs with grandpa and grandma” (P22, boy, 9 years), or “every time I sleep at my grandma’s, we listen to the radio” (P38, boy, 10 years). The majority of the children who listened to the radio did so in the car with their parents. As participant P69 (boy, 11 years) put it, “I would miss hearing the radio in the car every morning for half an hour as I go to school. If it were silent in the car, I really think I wouldn’t make it.”

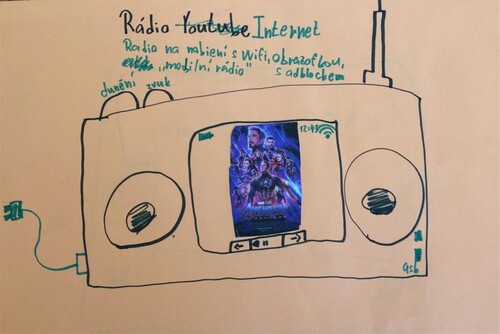

The distinction between the radio as a device, the radio as a media platform, and radio broadcasting was often blurry (this was specific to radio, not other media) for the participants in the research. For instance, when discussing the cards and talking about listening to the radio, participant P22 (boy, 9 years) said, “Our grandma has a radio and we listen to Hurvínek on it,” referring to an audiobook version of a play from the traditional Czech puppet theatre, Spejbl and Hurvínek. In creating their advertising poster for their “radio,” some children conceived of it as a physical device. One of the participants, P59 (girl, 9 years) came up with a Radio Prague device offered for a discounted price compared to its “overpriced” competitor. shows an advertisement for Radio Internet, described by its creators, participants P25 (boy, 11 years) and P26 (boy, 13 years), as a mobile radio set with a power cord and a touchscreen in the middle.

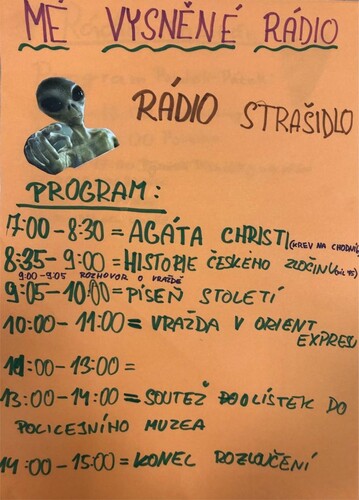

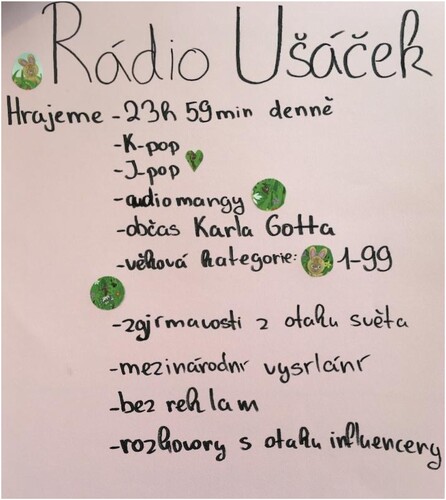

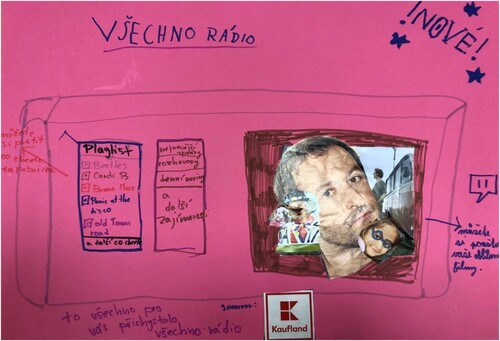

The mentions of the audiobook Hurvínek and Radio Internet point towards two other ideas we discovered in the minds of the focus groups, the connection of radio with other media and some general expectations that children had for all media, radio included. Firstly, the participants tended to position their imaginary radio stations within their overall media experiences. For example, shows Radio Ghost, whose creator, participant P70 (girl, 11 years) was a fan of fiction and detective stories. She built her radio station’s entire content around the work of Agatha Christie, including a competition in which first prize was an entry ticket to the Police Museum. is a poster entitled Radio Rabbit Ears created by two thirteen-year-old girls (participants P49 and P50), which was intended for an otaku (a Japanese term for anime and manga fans) audience aged one to 99. Their radio programme would be streamed internationally and include K-pop and J-pop songs, audio manga, news from the otaku world, and interviews with otaku influencers. Participants P71 (boy, 11 years) and P72 (boy, 11 years) created Radio Everything ().

Secondly, Radio Everything also shows the children’s expectations for the radio to be a digital multimedium with personalised content, search options, and unlimited access to its content, ideally via an app on the smartphone. Radio Everything was a device as well as a radio station, which allowed for a playlist with personalised music and films. Playing their own songs and having personalised playlists was a common feature the children’s radios offered. “We want an unlimited possibility to listen to songs … to create our own playlist of favourite songs, and to have the Internet in it to search for songs,” demanded Participants P30 (girl, 12 years) and P31 (girl, 12 years). Two boys and one girl, all 11 years old (Participants P71, P72, and P73) said that together with playing their own music, their audience could also read the latest news on their radio. Many stressed that their radios would broadcast and be accessible all day long, ideally without advertising. “We won’t have any breaks, we will run non-stop and all day with no commercial breaks,” declared Participant P45 (boy, 13 years).

The Relevancy of Radio, or the Lack of It, to the Children

The aim of the children’s radio station from which we obtained the sample programming, and the participating children’s expectations about radio, particularly crossed in one area, which was relevance. There was a shared understanding that content needs to be relevant to children’s interests and activities. However, we found there was disagreement about what child-focused and child-appropriate radio content and format was. The radio station attempted to identify with its young audience with the YouTube video hosted by an influencer who acted silly, and the news session with a moderator who talked to the audience in a familiar manner. Yet the programmes did not adopt a slower speed of talking and transitioning between scenes than in adult-targeted radio news. On the other hand, the radio stations the children designed in the FGs had almost no content specialised for children. It became obvious that it was not the format—YouTube video versus radio news session—that made content relevant or irrelevant to the children. These findings suggest that what could make the difference is the overall execution of the content, and whether or not it carefully considers and reflects the children’s wants, needs and often adult-like content expectations rather than the media producers’ ideas about children, childhood and children's media.

To illustrate this, the participating children understood and appreciated that the children’s radio station was trying to be relevant to a younger audience by creating the YouTube video. One of them said, “there are a lot of people, who watch, for example, just that YouTube video and then move on to the radio station” (girl, 13 years, P10). Another said, “well, I think that in these times, a lot of people watch those YouTubers, so I think it is a good promotion” (boy, 11 years, P69). When the children were asked if they wanted the imaginary radio station they created for the study to be promoted by a YouTuber, they liked the idea. They thought it could work well, but they criticised the execution and performance of the particular YouTube influencer in the sample for being too childish, weird, and embarrassing. “I don’t know YouTubers well, I don’t watch them much, but if a YouTuber were to promote me [meaning her radio station], he shouldn’t be so awkward and so embarrassing. The station should have to have some standards” (girl, 11 years, P70). Also, “it was terribly fast-paced, they should talk more about the book they reviewed” (girl, 12 years, P47). A similar perspective was offered by participant P27 (a boy, 12 years): “People would think I’m weird for watching a video where he [the influencer] is going ‘wuaaah’ [tiger roar].”

Many argued that style is crucial to a video’s success: “I would choose someone who talks normally and slowly,” said participant P38 (boy, 10 years). “He should behave rationally,” continued his classmate, participant P39 (boy, 10 years). The same opinion was heard in other FGs: “It really depends on the kind of YouTuber. … This [video] would not make me interested, quite the opposite … but if I could choose some good YouTuber, then why not,” said participant P69 (boy, 11 years). Some children even suggested that it would make more sense to promote the radio station on the YouTubers’ channels and not on the radio’s channel. “I find the whole idea of the YouTubers a bit weird, because they have their own channels where they could promote the radio station,” thought participant P71 (boy, 11 years).

The participants in the FGs considered news reports to be a natural part of radio and media programming, because the participants tended to include news in their radio stations’ content, as well as mentioning that during the discussions. After listening to the radio news recording, participant P61 (boy, 10 years) said: “I don’t find anything special about it, I mean almost everyone, including radio, has some news, weather, and so on.” However, the participants criticised the presenter’s fast speed of talking and the quick transitions and insufficiently elaborated news stories in the session. “Maybe I would develop the stories a bit, expand them a bit … so that once the fast part is over, they would go back and talk about those things more,” offered participant P12 (girl, 12 years). “I would want them to speak more slowly, I could hardly understand them,” said participant P20 (boy, 8 years). Participant P50 (girl, 13 years) agreed: “I didn’t have time to get all the information.”

The participants were divided when it came to evaluating the content of the news session with which they were presented. Some found it interesting, others not so much, but they all agreed that a lot depended on the topics’ relevance to their own interests. “I like some things they talked about, I would listen to that, but I didn’t like some other parts … for example, those about animals,” explained participant P10 (girl, 13 years). Participant P24 (girl, 9 years) appreciated exactly the opposite: “I liked it because it was about animals and weather.” However, children intuitively understood the news value of the content, i.e., the local relevance based on the geographical affiliation of each participant: “When I am here in Prague, I’m not really interested in what happens at the zoo in Liberec because I won’t be going there,” said participant P69 (boy, 11 years). A few participants disliked the childish style of the news or the idea of specialised news for children altogether: “I found it a bit strange. … [T]hey called us ‘friends’ and so on,” said participant P27 (boy, 12 years). Participant P71 (boy, 11 years) objected: “If a child needs to know the weather forecast, he or she would already know it from the adults’ radio.”

The children’s expectations that radio programming and content should be relevant to their interests and hobbies was clearly shown on the posters they produced. The vast majority of the posters the participants created for their imaginary radio stations (41 of 51) were either thematic (19 focused on sports, food, animals, cars, or crime, or included specialised content, 22 included K-pop songs, short news items about nature, stories about manga, or interviews with gamers). The activist potential of radio was mentioned by those who had previous knowledge about their cause. For instance, participant P66 (girl, 11 years) created a poster for Radio Ecologist () and participant P58 (girl, 9 years) created Animal Radio () advocating for an end to cruelty to animals, with the word “please” accompanied by an emoticon with teary eyes. Both of those children repeatedly raised those topics in the FGs. Except for occasionally including fairy-tales in their radio stations’ programming, the children usually did not suggest any particularly child-focused content, with the exception of participant P64 (boy, 9 years) who said “there should be some interviews with kids.”

Discussion and Conclusion

Journalism practice of the so-called “old media” often struggles to reach and engage children as an audience, especially in the Western countries (Balsebre et al. Citation2011). Radio journalism may fail to meet the needs of contemporary child audiences because it creates content for rather than with children and youth. In our paper, as in other empirical research such as that of Bignell (Citation2002), Woodfall and Zezulkova (Citation2016), and Parry and Taylor (Citation2018) we did not approach children as mere passive consumers of media content designed for them by adults. We attempted to explore the holistic and dialogic relationship between media and its young audience as a highly complex phenomenon based on mutual influences. Above all, our focus was on the dynamic nature of that relationship and on the competencies and interests of children, which are highly valuable to journalism practice.

The children involved in our research did not have much conscious previous experience with radio (cf. Balsebre et al. Citation2011), possibly showing “determined disaffection for radio as media” (Gutierrez, Ribes, and Monclús Citation2011, 305). Yet when they were asked to create their own radio stations and programming, they were motivated, engaged, and greatly willing to express their thoughts about potential improvements in radio targeted at children. This corresponds with research conducted with older children and youth (e.g., Wagg Citation2004; Bosch Citation2007; Wilkinson Citation2018), which explored the potential of young audiences to engage and participate in the creative and production processes of radio and other media before, during, and after the content is created. Our research also contributes to the body of knowledge in this area by demonstrating that younger children’s original thoughts and ideas can be relevant to radio broadcasting, public media, and journalism practice in general. Our research participants seemed to enjoy the research interventions and discussions during which they provided many valuable insights and ideas within a short period of time. For instance, the genre of live talk back shows with children on important various topics supported by online and digital media could be one of the options for creating opportunities for participation and improving the relevance of the radio platform, form and content.

Although the demand for relevant content is not a recent development (MacLennan Citation2013), what it means to be “relevant” in journalism practice has arguably changed with digital and online media. For example, the fragmentation described by Zelenkauskaite (Citation2017) creates a considerably greater number of groups of listeners with often niche interests who want to be entertained as well as informationally saturated. It was mirrored in our participants’ relationships to, and expectations about, radio that was influenced by their complex experiences with other media platforms (e.g., smartphones), services (e.g., Spotify), and content (e.g., manga). The change also lies within the media experience shared among children across national and cultural borders (Woodfall and Zezulkova Citation2016), such as in the Children's Media Lives research by Ofcom, which arrived at similar conclusions as those mentioned above, including the increased interest of children in manga in the past years (Ofcom Citation2021).

This also points once again towards children’s complex engagement and interaction with media platforms and content in a dialogic relationship. Radio can hold a more prominent place within the children’s holistic media experience if it continues to undergo what Bolter and Grusin (Citation2000) called “remediation” and McClung, Pompper, and Kinnally (Citation2007) termed “functional reorganisation”. The young audience is used to listening, but rather than radio they listen to on demand music on their smartphones (Gutierrez, Ribes, and Monclús Citation2011) and podcasts. There is an opportunity for radio to learn from this and to subsequently strengthen its role in children’s lived media experience while applying remediation theory in practice. Radio can therefore be more relevant to children, for example, by offering well executed media content allowing personalisation and “on demand” access.

A broader role of radio, and other media, in children’s lives needs to be equally considered and addressed as a criticism of polarisation between information and entertainment. Firstly, the children expected radio stations to provide information in entertaining and child-appropriate, but not childish, ways for them as individuals and as members of their communities. A lack of interest in generalised information has previously been observed among adult audiences (Mensing Citation2017) and as our research suggests, this could apply even more strongly to younger audiences. Secondly, a relatively small, but still significant part of the participants in our research connected their needs and wants with social activism and perceived the radio station as a tool to support their causes. The interest of the children in environmental and animal rights activism, and not, for example, with fighting poverty or harsh social conditions, as seen in other parts of the world (Bosch Citation2007), can be explained by the different social situation in the Czech Republic and possibly also by the younger age of the participants. Thus, it is not only in the developing world where radio can contribute to children and youth’s active citizenship (Bosch Citation2007), but it can also nurture and support critical news literacy (Carter Citation2013; Mihailidis Citation2014) of younger children anywhere, while acknowledging their right “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers” (Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948).

We thus also emphasise the importance of exploring and acknowledging the social and historical contexts of radio, as well as other media, in children’s lives. As we discovered, the children often accessed, and listened to, radio with older family members. This is in sharp contrast to the situation from the early days of radio when, as MacLennan (Citation2013) describes, radio as the “new” medium was being rejected by the older generation. A similar phenomenon can be witnessed today in the case of social and digital media, and it will continue to reappear with every new technology. As such, our research contributes to the criticism of dichotomies of techno-optimism vs techno-pessimism or social vs technological determinism (Moyo Citation2013; Zelenkauskaite Citation2017) and instead supports the idea of reciprocal relationships embodied in children’s holistic and dialogic media experience.

Our research was limited in its scope and geographical location, yet it applied participatory and creative qualitative methods and techniques allowing children to share their lived experience and voice their ideas and suggestions. This allowed us to at least partially address the gap of recent research on younger children’s experience with, and attitudes towards, radio. Furthermore, even though our research focused on a single medium, a so-called “old” medium with which the children had little experience, its findings and conclusions will hopefully contribute to the complex understanding of children’s media experience and to journalism research, theory and practice. With new formats such as podcasts becoming increasingly popular among young and older adults, radio could be an important medium of the future and its development for child audiences deserves attention. Future research could involve other Central European and/or Western countries in order to allow comparison of global similarities and local differences. We believe this could provide valuable insights into, among other things, the alarmingly under researched area of radio’s current and potential role in younger children’s lives and citizenship.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Balsebre, Armand, Perona Juan José, Fajula Anna, and Mariluz Barbeito. 2011. “The Hidden Radio Audience in Spain: Study on Children's Relationship with the Radio.” Journal of Radio & Audio Media 18 (2): 212–230.

- Bignell, Jonathan. 2002. “Writing the Child in Media Theory.” The Yearbook of English Studies 32: 127–139.

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 2000. Remediation. Understanding New Media. Boston: MIT.

- Bosch, Tanja E. 2007. “Children, Culture, and Identity on South African Community Radio.” Journal of Children and Media 1 (3): 277–288.

- Buckingham, David. 2009. “‘Creative’ Visual Methods in Media Research: Possibilities, Problems and Proposals.” Media, Culture and Society 31 (4): 633–652.

- Buckingham, David. 2015. Beyond nostalgia: writing the history of children’s media culture. March, 2015. https://ddbuckingham.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/nostalgia.pdf.

- Carter, Cynthia. 2013. “Children and News: Rethinking Citizenship in the Twenty-First Century.” In The Routledge Handbook of Children, Adolescents and Media, edited by D. Lemish, 255–262. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Carter, Cynthia, Jeanette Steemers, and Máire Messenger Davies. 2021. “Why Children's News Matters. The Case of CBBC Newsround.” Communications: European Journal of Communication Research 46 (3): 352–372. doi:10.1515/commun-2021-0048.

- Daelman, Silke, Elisabeth De Schauwer, and Geerth Van Hove. 2020. “Becoming-with Research Participants: Possibilities in Qualitative Research with Children.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 27 (4): 483–497.

- Darbyshire, Philip, Wendy Schiller, and Colin MacDougall. 2005. “Extending New Paradigm Childhood Research: Meeting the Challenges of Including Younger Children.” Early Child Development and Care 175 (6): 467–472.

- Fetveit, Arild. 2007. “Convergence by Means of Globalized Remediation.” Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook 5 (1): 57–74.

- Gerstenblatt, Paula. 2013. “Collage Portraits as a Method of Analysis in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12 (1): 294–309.

- Gibson, Faith. 2007. “Conducting Focus Groups with Children and Young People: Strategies for Success.” Journal of Research in Nursing 12 (5): 473–483.

- Graham, Anne, Marry Ann Powell, Nicola Taylor, Donnah Anderson, and Robin Fitzgerald. 2013. Ethical Research Involving Children. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti.

- Gutierrez, María, Xabier Ribes, and Belén Monclús. 2011. “The Youth Audience and the Access to Conventional Broadcasting Music Radio Through Internet.” Communication & Society 24 (2): 305–331.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

- Jewitt, Carey, ed. 2014. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Lemish, Dafna. 2021. “Like Post-Cataract Surgery: What Came Into Focus About Children and Media Research During the Pandemic.” Journal of Children and Media 15 (1): 148–151.

- MacLennan, Anne F. 2013. “Learning to Listen: Developing the Canadian Radio Audience in the 1930s.” Journal of Radio & Audio Media 20 (2): 311–326.

- Marchi, Regina. 2009. “Z-Radio, Boston: Teen Journalism, Political Engagement, and Democratizing the Airwaves.” Journal of Radio & Audio Media 16 (2): 127–143.

- McClung, Steven, Donnalyn Pompper, and William Kinnally. 2007. “The Functions of Radio for Teens: Where Radio Fits Among Youth Media Choices.” Atlantic Journal of Communication 15 (2): 103–119.

- Mensing, Donica. 2017. “Public Radio at a Crossroads: Emerging Trends in U.S. Public Media.” Journal of Radio & Audio Media 24 (2): 238–250.

- Mihailidis, Paul. 2014. Media Literacy and the Emerging Citizen. New York: Peter Lang.

- Moyo, Last. 2013. “Introduction: Critical Reflections on Technological Convergence on Radio and the Emerging Digital Cultures and Practices.” Telematics and Informatics 30 (3): 211–213.

- Ofcom. 2021. “Children’s Media Lives.” Available from https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/217827/childrens-media-lives-year-7.pdf.

- Parry, Becky, and Lucy Taylor. 2018. “Readers in the Round: Children's Holistic Engagements with Texts.” Literacy 52 (2): 103–110.

- Piper, Heather, and Jo Frankham. 2007. “Seeing Voices and Hearing Pictures: Image as Discourse and the Framing of Image-Based Research.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 28 (3): 373–387.

- Radio Junior. 2019a. Minutové zprávy, April 24. [Minute News][MPEG].

- Radio Junior. 2019b. Miky a knížky do aprílového počasí I Knižní agenti #12 [Miky and Books for April Weather I, Book Agents #12] Youtube, April 9. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dgu-EZ4leig&ab_channel=R%C3%A1dioJunior.

- Supa, Markéta, Vlastimil Nečas, Jana Rosenfeldová, and Victoria Nainová. 2021. “Children as Cosmopolitan Citizens: Reproducing and Challenging Cultural Hegemony.” International Journal of Multicultural Education 23 (2): 23–44.

- Supa, Markéta, Martin Sokup, and Victoria Nainová. forthcoming. “Diversity and Normalcy in Children's Peer Culture: Attractiveness, Stereotypes, and Exclusion.”

- Theodosiadou, Sophia. 2010. “Pirate Radio in the 1980s: a Case Study of Thessaloniki’s Pirate Radio.” The Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast and Audio Media 8 (1): 3–49.

- Thomas, Nigel Patrick. 2021. “Child-led Research, Children’s Rights and Childhood Studies: A Defence.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 28 (2): 186–199.

- Van Manen, Max. 1990. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Wagg, Holly. 2004. “Empowering Youth with Radio Power: “Anything Goes” on CKUT Campus-Community Radio.” Journal of Radio Studies 11 (2): 268–276.

- Wilkinson, Catherine. 2015. “Young People, Community Radio and Urban Life.” Geography Compass 9 (3): 127–139.

- Wilkinson, Catherine. 2018. “On the Same Wavelength? Hyperdiverse Young People at a Community Radio Station.” Social & Cultural Geography 20 (9): 1251–1265.

- Woodfall, Ashley, and Marketa Zezulkova. 2016. “What ‘Children’ Experience and ‘Adults’ may Overlook: Phenomenological Approaches to Media Practice, Education and Research.” Journal of Children and Media 10 (1): 98–106.

- Zelenkauskaite, Asta. 2017. “Remediation, Convergence, and big Data: Conceptual Limits of Cross-Platform Social Media.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 23 (5): 512–527.

- Zelenkauskaite, Asta. 2018. “Value of User-Generated Content: Perceptions and Practices Regarding Social and Mobile Media in two Italian Radio Stations.” Journal of Radio & Audio Media 25 (1): 23–41.

- Zimmermann, D., C. Noll, L. Gräßer, K.-U. Hugger, L. M. Braun, T. Nowak, and K. Kaspar. 2020. “Influencers on YouTube: A Quantitative Study on Young People’s Use and Perception of Videos About Political and Societal Topics.” Current Psychology. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-01164-7.