ABSTRACT

Journalism faces a number of challenges: patterns of news consumption have changed and audiences for traditional news outlets are declining. In this context, we explore whether the “inverted pyramid” model – a system of news writing that arranges facts in descending order of importance, which remains predominant in journalism – is the most effective way of communicating information online. Based on a mixed-methods approach using qualitative data from workshops and expert consultations, we developed a series of new “prototypes” of online news storytelling and tested them with a wide range of audiences (N = 1268). Building on earlier work, we find that linear forms of storytelling - rarely used in news - are more effective in transferring knowledge to news consumers and are seen as more engaging, convenient and useful than the traditional inverted pyramid. We then identified key principles that should underlie a more user-focussed approach to narratives in online news.

1. Introduction

Two decades ago, Pavlik (Citation2000) predicted that ongoing technological changes and the emergence of the internet would have a profound impact on both journalistic work processes and news content. To date, research in this area has often focussed on the implementation of new technologies on news-making activities. This includes, for example, research on multi-media news creation (Ursell, Citation2001) or data-driven journalism practices (Parasie and Dagiral, Citation2013). What has received less attention - in both academia and newsrooms – are more fundamental storytelling practices in news-making.

The ongoing changes in consumer behaviour and the increasing audience migration to online news inform a strong case for innovation in the way we tell news stories. Ofcom (Citation2020) found that in recent years, there has been a considerable increase in the number of people in the UK accessing news via online platforms rather than traditional platforms like print, the radio or television. Younger audiences - especially 16–24-year-olds - are now more likely to use the internet for news than TV (79% vs. 49%).

The so-called “inverted pyramid” (IP) - a system of news writing - that arranges facts in descending order of importance – has long been a cornerstone of journalism practice and storytelling (Norambuena et al., Citation2020). The IP is still the predominant way of writing “hard news” stories, even though the internet and new media allows for a plethora of new ways of storytelling and creates opportunities for more interactive engagement with news. As audiences for traditional forms of storytelling continue to decline (especially amongst younger cohorts), it is important to ask whether there are more informative and engaging alternative ways to tell news stories. Our research was guided by two questions:

Is the IP structure still the best way to convey to news in the new media context?

How might we develop and test new potentially more informative and engaging forms of news storytelling?

We addressed these questions with a two-stage mixed-methods approach. First, we gathered qualitative data from a series of workshops and stakeholder consultations to develop a number of principles that might support a more user-focussed approach to online news storytelling. These were subsequently developed into a series of new “prototypes” for online news storytelling. Second, their general appeal and usefulness were then tested with a large-scale audience survey (N = 1268).

2. From the Inverted Pyramid to Narrative Storytelling

While news will partly appeal to readers, viewers and listeners because of its content, the way in which that content is presented often determines its impact. When using the telegraph at the beginning of the nineteenth century, journalists sent news in paragraphs (Canavilhas, Citation2007), where the imperative was to communicate facts in order of importance (Pöttker, Citation2003). This created a very particular kind of information hierarchy, in sharp contrast to a chronological narrative structure in which events are reported in the order in which they occurred, and where the culmination of the story comes at the end (Norambuena et al., Citation2020; Thomson et al., Citation2008; Van Krieken, Citation2018; Walters, Citation2017). The IP model was advantageous for print, allowing editors to cut copy from the bottom upwards without losing the key elements of the story (Lewis, Citation1994; Pöttker, Citation2003). With information prioritised over suspense (Van Krieken, Citation2018), the IP made news faster to write, and, as newspapers became daily disposable commodities (Lewis, Citation2017), often faster to read (Rabe, Citation2007).

By the early twentieth century, the IP style became fully established as the most effective and economical model for the communication of news (DeAngelo and Yegiyan, Citation2019). Although this style is associated primarily with newspaper journalism (Knobloch et al., Citation2004) it was also appropriated by broadcast journalism despite the fact that some of the logic behind it – such as ease of print editing - no longer applied (Lewis, Citation1994), and, much later, online news in new media outlets. It fits well with the increasing emphasis on breaking news (Lewis and Cushion, Citation2009), and has come to be strongly associated - wrongly, in our view - with objectivity, with an emphasis on fact rather than journalistic interpretation (Kleemans et al., Citation2018; Nee and Santana, Citation2021; Norambuena et al., Citation2020; Pöttker, Citation2003). Although history is necessarily chronological, the notion that linear narratives signify a “less objective” account has become an ingrained assumption. The IP thereby continues to dominate both old and new media platforms (Chadwick, Citation2017).

Despite the possibilities of new media, the IP’s dominance in news remains formidable, entrenched in long-standing routines and forms of training (Gynnild, Citation2014). But its efficacy as a form of communication is coming under increasing scrutiny. For some, the IP is “past its currency” (Kleemans et al., Citation2018: 2109) and has become “something of a dinosaur” (Yaros, Citation2006: 287). It is recognised that the IP model involves performing interpretative roles (Ward, Citation2009: 299). Indeed, rather than simply being an objective account, the IP is, in many ways, a more structured interpretive intervention than the linear narrative, where journalists necessarily impose a hierarchy of factual importance in the recounting of unravelling histories.

Especially, the emergence of new modes of news delivery has triggered the reexamining of the efficacy and suitability of the IP (Ytreberg, Citation2001). Because the IP “is not structured as a simple narrative” (Ytreberg, Citation2001: 360) it only represents one end of a news story, leaving the other end open (Kosara, Citation2017) and prone to simply petering out as it covers detail with decreasing value, relevance and interest. As a consequence Bragg (Citation2000) sees the strict, formulaic IP as inhibiting “creativity and freedom”, while Giles (Citation2004) suggests the non-linear IP structure might be more complex for audiences to navigate.

Even before the emergence of online news, research suggested that more linear narrative approaches are far more effective in holding people’s attention and conveying information (Lewis, Citation1994). DeAngelo and Yegiyan (Citation2019: 388) note the IP’s “reliance on the receiver to access previously stored knowledge as they continue through the story”. While the IP calls on significant cognitive resources, the resources that are left may be insufficient for audiences to efficiently compute the story overall (Kleemans et al., Citation2018). And as the rigidity of traditional structures has come up against the online, “journalists often discuss the concept of storytelling or, more precisely, the narrative structure of news” (Emde et al., Citation2016: 608).

Scholarly work often focuses on the ways in which the structural elements of news can influence recall, understanding and perception. In a forerunner to this research, the impact of narrative on levels of understanding and engagement was tested by Machill et al. (Citation2007), who gave audiences two versions of a news story - one using the IP and the other based on a more innovative linear narrative. Their research showed that the linear narrative was perceived as more interesting and more successful in communicating information. Thereafter, audience attitudes to the value of narrative within news have been researched from various perspectives (see Tamul et al., Citation2019 for a full summary).

Research has also explored other forms of storytelling, examining the style and context of news. This includes, for example, the increasing crossover between news and comedy/satire genres that make clear attempts to inform and explain as well as entertain (Kilby, Citation2018). Indeed, Hardy et al. (Citation2014) suggest that comic forms of narrative are actually more effective than traditional news in communicating factual information. Mihelj et al. (Citation2009) explored the ways in which different styles of news narrative are used in different contexts, and how the narrative conventions of television news create different discourses. Nee and Santana (Citation2021: 15) found that long form journalistic storytelling makes the “story” the primary objective and “news” elements more secondary.

There is, however, an understandable caution about abandoning the IP model, which audiences have come to understand and associate with news. Emde et al. (Citation2016) for example, suggest that while audiences more easily process “narrative news”, this may only apply to younger news consumers for whom the context and background are important. And introducing narrative is not necessarily a panacea: DeAngelo and Yegiyan (Citation2019: 400) found that IP stories “were not only recalled earlier and more accurately, but also resulted in less time spent on story webpages”; while “narrative stories were recalled later and with less accuracy—even though users spent more time on the story webpages”.

The caution has kept the IP orthodoxy firmly in place, and after generations of adherence to the IP, narrative journalism only enjoys “marginal status” (Van Krieken and Sanders, Citation2019: 10), limiting the empirical basis for assessing its efficacy. But if journalistic fundamentals such as the inclusion of emotion can be reimagined (Wahl-Jorgensen, Citation2020), challenging the relevance of established news reporting formats remains critical, especially in the context of declining news audiences for most traditional news formats. At the very least, research into narrative structures within news appear to support assertions that the IP is now only one journalistic option, “alongside more creative, less structured narrative styles” (Johnston, Citation2017: 14).

As Birkner et al. (Citation2018: 1124) ask: “have the developments in online journalism turned the inverted pyramid model upside down?” Our contribution to this important journalistic debate is to develop the “scattered field” of narrative journalism research (Van Krieken and Sanders, Citation2019: 13) by conducting a multi-point comparison between various journalistic storytelling structures. By employing an innovative methodological approach embracing the “experiences, motivations and emotions” (Witschge et al., Citation2019: 974) of a range of storytelling practitioners, we can make both a theoretical and practical intervention in the search for the most efficient and audience-friendly ways to impart news and information.

3. Methodology

We chose a mixed-methods approach, with qualitative approaches informing a quantitative audience study (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). In the first (1) theoretical phase of the research, qualitative data from (a) expert consultations and (b) workshops was gathered and analysed, leading to the creation of a series of experimental prototypes. In the second (2) empirical phase, we tested the principles and subsequent prototypes identified in phase 1 with online news audiences.

The (1) first phase of research included a series of (a) semi-structured interviews with 12 experts in journalism and storytelling and two workshops with news consumers and storytelling experts from diverse backgrounds. These interviewees were selected through a purposive sampling method (Bryman et al., Citation2008) in order to provide a broad range of perspectives from across the journalism, technology and storytelling fields. Interviews were conducted between October and December 2019 (see ). Initial contact was made via email, and in person/remote interviews arranged as appropriate. These interviews generally lasted between 30 min and an hour and were conducted either in person or via telephone or Skype/Zoom. The interviewees included five newsroom leaders / digital news experts from different media outlets including the BBC, ITV, and the Financial Times, three senior journalism academics, and experts on storytelling from outside journalism, including a puppeteer, a game designer, a YouTuber and a comedian.

Table 1. Interviewees’ experience and background.

Because the interviewees had a range of entry points on journalism, the interviews were semi-structured to allow the interviewees to focus on areas they felt were most important (Longhurst, Citation2003). Topics in the interviews were chosen to inform the development of innovative approaches to news storytelling, including: the need for storytelling; how users engage with storytelling and the purpose stories fulfil; the efficacy of current journalism; how journalism might better use storytelling tools/approaches, and potential editorial innovations that might help journalism increase audience engagement and understanding.

Two (b) workshopsFootnote1 were also conducted during the interview phase. The first was with news audiences often seen by mainstream news providers as hard to reach: a group of fifteen young people aged between twelve and seventeen years old from BAME backgrounds. The group was recruited through the Ethnic Youth Support Team, an organisation which runs the All-Wales BAME Engagement Programme for the Welsh Government. The young people were invited to work with one of the authors in a session, lasting approximately 75 min, modelled on participatory action research protocols. Notes taken were later coded for a thematic analysis.

The group began by watching a traditional TV news programme (a recent edition of the BBC’s News at Ten), and then gave feedback. A broader discussion then explored the thoughts of the workshop attendees about the barriers they face to accessing and engaging with news. Questions addressed included: if/how the young people engaged with news, what the barriers to engagement were, what changes to the way news is presented might make them more interested in consuming news. These questions elicited a range of responses which were used in the preparatory phase of the research to inform the framework development, notably around the levels of detail and complexity of both the editorial and product layers of the prototypes. The second workshop looked at what we might learn from traditional (non-news) storytelling techniques and how they might be applied to journalism, bringing together seven storytellers, journalists, technologists with a group of students to share experience, analysis and insight. The session lasted a full day, and included a mix of co-learning, discussion and critical analysis of storytelling techniques.

The insights gathered from the (a) interviews and the (b) two workshops (in total 19 experts on journalism and storytelling and 15 news consumers), were coded and analysed. Combined with insights from the research literature, the interviews and workshops built up a rich body of material. This was analysed iteratively to identify key themes, concerns and viable proposals for new storytelling models, and led to the identification of key principles for online news storytelling, which formed the basis for creating a series of prototypes.

The storytelling prototypes (described in more detail below) all addressed the same story - the government’s decision to go ahead with the development of the HS2 high-speed rail link announced on 11th February 2020 (see https://www.bbc.com/news/business-51461597). This story was announced on the day of the second storytelling workshop, and was chosen for its typicality as a hard news story, with a broad context and a wide-ranging impact that had developed over time. The original story also uses the IP storytelling style.

In the (2) second phase, we tested the new storytelling prototypes with a sample of 1268 people across the UK. Recruitment was carried out by a user research recruitment companyFootnote2, giving us access to their network of pre-screened research participants. Participants were chosen to provide a representative sample of the wider population, with mix of demographics such as age gender and education, but with a deliberate skew towards younger groups, who are most likely to have abandoned traditional forms of news (Ofcom, Citation2020). The questionnaire was created in the Survey Monkey platform (https://www.surveymonkey.com). While most respondents answered most questions, not all questions were mandatory, so the overall N varies across the range of variables. gives the age range of the sample and shows that older audience members were, according to self-assessment on a 10-point scale, a little more likely to consider themselves well-informed.

Table 2. Survey respondents demographics and breakdown of self-assessment of how informed participants rated themselves (on a 10-point scale).

We used the original BBC News article (which embodied the traditional IP style of narrative and the habitual approach to news writing) as control to test against our prototypes. We used BBC branding on all our prototypes, so the “brand” was perceived as the same across all the stories being tested. Respondents were assigned randomly to each prototype, with subsequent checks to ensure that the samples for each prototype possessed broadly similar demographic characteristics.

After a series of introductory questions about users’ consumption of news and their current knowledge of the issues surrounding the topic of the article, the respondents looked at one of the prototypes or the original news story. First, each participant was asked to rate the degree to which they felt they knew about the news (1 being the least informed and 10 the most informed). We then asked a series of questions to gauge their responses to the story and perceived changes to their level of knowledge. Respondents rated their reaction to the story across a number of different response categories, ranking them on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” (see Annex for full list of survey questions).

4. Findings

4.1. The Identified key Principles of Online News Storytelling

Drawing on previous research and interview responses from the storytelling and journalism experts and user workshops, we identified five key principles for formulating more effective online news storytelling. Our approach was user-focused, and at the core of each of these principles are the needs of citizens as news consumers. We started with the overarching concept of (1) narrative, which previous research suggests may be at the heart of more informative storytelling, and which was a recurrent theme in our interviews. A further four principles emerged as key issues in the interview/workshop phase: (2) content, (3) context, (4) agency, and (5) tone.

Narrative: Machill, Köhler and Waldhauser’s (Citation2007) audience study gave a clear indication that using a linear narrative was seen as more interesting and more successful in communicating information. This idea was developed by a number of our interviewees as well. So, for example, an anthropologist with expertise in storytelling talked about how, as humans, we are “hardwired for stories” because they serve an evolutionary role as “virtual reality simulators of the world”. The IP structure conflicts with how we commonly understand stories (e.g., a traditional three act dramatic structure), “annihilating suspense” (as our interviewee put it) and thereby creating a kind of cognitive dissonance. Indeed, all the storytelling specialists amongst our interviewees found journalism’s use of the IP structure anomalous, as it conflicted with all the techniques they routinely use to engage audiences. Participants in the user focus group also described the IP structure as “confusing”, “backwards” and “difficult to understand”.

Content: Research indicates that traditional ideas about the hierarchy of content in a news story are largely driven by habit and convention, rather than an exploration or understanding of the needs and thought processes of news consumers. Online news, in particular, is well positioned to rethink these conventions (Bull, Citation2007), which are not inherent in the objects of journalistic work (Pöttker, Citation2003). Similar ideas were expressed by especially several of the non-journalist experts. Users in the focus group said they wanted “more information that helped them understand what was going on in (my) life”, and “less politics, because it doesn’t help me understand the story”.

Context: A running theme raised in both the interviews and workshops was the desire for news to provide more context so that stories could be better understood. Mainstream news coverage tends to prioritise breaking or at least “moving” news, but often to the detriment of context, analysis or understanding (Lewis and Cushion, Citation2009). The focus on breaking news felt confusing to workshop participants who didn’t read the news every day, giving them no comprehensible entry point to ongoing stories. Many felt that too much knowledge was assumed, a key barrier to their engagement or understanding. The importance of context also was also highlighted in our expert interviews. For example, one interviewee felt the habitual focus on moving stories meant climate change – something which is happening gradually, over time – didn't fit comfortably into the traditional modes of journalism: “For me, context is everything and the reason the news is important is because it fits into a wider context and helps clarify the situation. As a scientist, a new report or paper can’t be understood meaningfully unless it’s put into a wider context”. Users in the focus group also reported, for example, feeling confused by a focus on relatively small, line-by-line details of Brexit negotiations when they rarely got the “zoom out” to the wider picture to help them understand its broad implications.

Agency: Both workshop participants and storytelling experts told us that agency was important on both the input and output sides of news coverage. Agency connects with narrative, and storytellers spoke about how they work to leverage our inbuilt sense of curiosity to drive engagement, and suggested ways that journalists could use similar techniques. For example, online displays of news enable news consumers to interact with the text, and audiences could choose which information they want to display. Keng and Ting (Citation2009: 479) suggest that interactivity creates “interpersonal interaction” enhancing “aesthetic experiences as well as playfulness”. An interview referenced for example the richness of Nintendo’s Zelda games which have detailed environments which give players the space to simply explore things which feel interesting - not to fulfil an objective or complete a task, but simply to satisfy one’s natural curiosity. He described how we often fall down Google or YouTube “rabbit-holes”, leveraging our curiosity and agency to find out and learn new things.

Tone: One of the strongest responses from the user workshop with young people was that the voice that traditional news media uses to communicate is “old-fashioned” and “formulaic”. In the same vein, the Reuters Digital News Report found that just 16% of users worldwide agreed that “the news media uses the right tone” (Newman, Citation2020). Hardy et al. (Citation2014) suggest that comic forms of narrative are often more effective communicators than traditional news. While the use of comedy in mainstream news may raise other issues, interviewees felt that online journalists in particular need to find modes of address, which are more suitable for modern forms of consumption, rather than leaning heavily on habits drawn from newspaper writing. This was particularly evident in the user focus group we carried out with young people. When watching a flagship BBC News bulletin, they reported being bored or distracted within a minute of the programme starting - a key problem to be addressed.

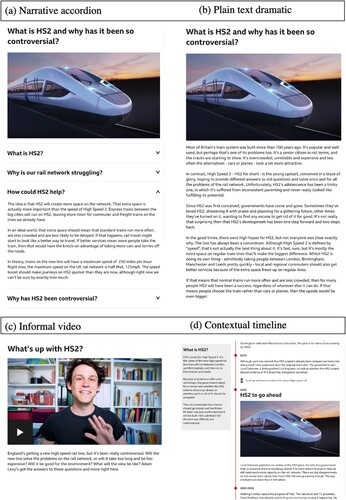

We used these principles (1-5) to create four different prototypes for news storytelling to test against the original BBC version. Each of the prototypes uses a broadly (1) linear narrative style, albeit in different formats and structures. Each prototype approached the story with a user-focussed “what do I need to know” question – encapsulated in our second content (2) principle - focussing on the most useful content for understanding the broad scope of the story rather than habitual journalistic conventions about news value. This meant a move away from prioritising the “on the day” element of the story - what Lewis (Citation2017) describes as a commodified approach to news – and paying more attention to deeper background and understanding. We then used different prototypes to stress (3) context, (4) agency and (5) tone. Three of the four prototypes enabled, in varying degrees, the user to choose how they consumed the story, expressing their own agency in how they navigated – perhaps in line with their particular interests or the way their curiosity naturally took them. The nature of tone is difficult to isolate or categorise, but the overall approach was to write the stories in a simple, clear and straightforward way, in line with principles from the developing field of content design and limiting the use of what might be called “journalese”. The prototypes and their relation to the principles described above were as follows (see also ):

Narrative Accordion: This prototype builds on (4) agency and narrative, telling the story in a linear narrative, separated by expanding and collapsing questions. The user can choose to read these questions from start to finish - working through the narrative in a straightforward, linear way – or read the story in a non-linear way, allowing their interest in particular questions to guide how they consume the story.

Plain Text Dramatic: This prototype was designed to directly test the value of linear narrative style - as opposed to the IP. It is written in plain text, using a traditional three-act narrative structure. This was designed to draw the reader through the story in a linear narrative style, but with a sense of “character”, “dilemma” and “resolution”.

Informal Video: This video was designed to test responses to an informal and playful (5) tone, to see whether this might help engagement, knowledge transfer or information retention. Using a treatment similar to those seen on The Daily Show, or Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj, if less didactic and partial, the video tells the story in a gently humorous way, building on a linear narrative style.

Contextual Timeline: This format was designed to focus on placing the story in (3) context, in a timeline display. The story aimed to deprioritise the “on the day” event, opting instead for a broader longitudinal view which gives the user a range of possible entry points. The timeline looks forwards as well as backwards, giving users a sense of what might happen next as well as what’s already happened. Users can choose where and how to engage with the timeline and can scroll, scan or read whichever sections they find most interesting, giving the readers agency. The foregrounding of context and agency in this prototype may have a disruptive impact on the linearity of the narrative.

4.2. Testing the Principles

Using the percentage of respondents who spent more than three minutes reading or viewing each story, we get a broad sense of how long it took for each one to be consumed. Given that users knew they were going to be asked a series of questions after viewing the story, we can assume that they viewed all, or at least the majority, of the story. So, for example, 85.2% of users who watched the (c) Informal Video spent more than 3 min on it, which reflects the time it takes to watch the 3’42” video. shows that of the written stories, the Original BBC version takes the longest to consume, closely followed by the (b) Plain Text Dramatic prototype. The (d) Contextual Timeline and the (a) Narrative Accordion were consumed more quickly. This is useful to bear in mind when considering the data that follows, and suggests that the use of narrative is not necessarily a more time-consuming way to tell a news story as is often suggested.

Table 3. Breakdown of how long readers took over each prototype.

We asked our respondents to rate (out of 10) how well-informed they felt about HS2 before they looked at the version of the story randomly assigned to them, and how informed they felt after reading/watching the story. This question may have an inbuilt bias towards traditional forms of news, which may “feel” more informative because it “looks like news’ (as we shall see shortly, the original article performed notably better on this than on most other questions).

shows the difference between the “after” rating and the “before” rating, which produces a useful measure of “added value”. This is, of course, a subjective measure: there may be a difference between being informed and feeling informed. However, despite taking less time to consume, the (a) Narrative Accordion format provided 24.3% more (perceived) added value for readers than the original article (2.96 value added rating compared to 2.38), and was, according to this measure, the best performing prototype, emerging as the more efficient method of delivering news, both in terms of speed and the extra value it adds for news consumers.

Table 4. The “value added” provided by each prototype.

We can also see some differences between age groups. The (a) Narrative Accordion was especially strong amongst younger respondents, who also responded well to the (b) Plain Text Dramatic and (c) Informal Video versions (in marked contrast to respondents over 55).

To explore audience engagement and understanding in more detail we asked a series of questions about the experience of reading/watching the original and the prototypes. These questions fell into three broad categories (see also Annex for an overview): (i) assessing their experience of engagement with the news item (so, for example, how interesting, enjoyable, useful and relatable they found it); (ii) commenting on more stylistic and functional dimensions (such as the language, layout, format, and visual appearance); and (iii) the public service and democratic impact of the news item (so, for example, whether they now felt more comfortable discussing the news with their friends and family, or whether they better understood the information presented in the news article).

Because there is no clearly understood lexicon of the value and purpose of news, we used a range of (often similar) terms to probe these three areas. Questions asked participants to rate various aspects on a scale, or to rate the degree to which they agreed with statements about them. In all, there were 16 evaluative categories, summarised in . We analysed the scores for each prototype and identified the top three rated prototypes in each category. For comparison, we used a points system assigning 3 points to a top position, 2 for a 2nd place and 1 point for a 3rd place.

Table 5. Summary of participants impressions about the prototypes and numerical synthesis of the findings.

We can observe, in broad terms, a link between all three broad areas: with the (a) Narrative Accordion (once again) and the (c) Informal Video performing consistently well. However, some of these links appear stronger than others. While the (d) Contextual Timeline scored comparatively well in terms of form and function (especially in terms of layout, navigation and format), it received poor scores for both engagement and democratic or public service impact (suggesting that the former is generally a prerequisite for the latter), with no top three ranking on any questions in these two areas. This was the most overtly interactive of the prototypes, and its scores suggest that most respondents were put off by the work required to make sense of the story and the lack of narrative structure created by multiple entry points.

Overall, these findings suggest a focus on engaging audiences will have more impact than a focus on the more functional aspects – such as ease of navigation and visual appeal – of a news story. While the (a) Narrative Accordion, the (c) Informal Video and the (d) Contextual Timeline all scored well on form and functionality, only those that also scored strongly on engagement (the Narrative Accordion and the Informal Video) appeared to have a strong impact on public understanding. Respondents may have appreciated the (d) Contextual Timeline’s formal features, but their lack of engagement appeared to limit what they could learn from it.

In the same vein, scores for the (b) Plain Text Dramatic version which, as the name suggests, focused on the strength of the narrative with minimal formal features (like strong visuals or interactive layout), had the poorest scores for form and style but very strong scores for its impact on public understanding. It was the best performer in three important areas, ranked as the most informative, the most likely to increase understanding of the context, and – a key test from a democratic perspective - the one best able to give respondents what they need to make an informed judgment about HS2. The fact it did not score particularly well on engagement measures (although scoring higher than the original PS version for interest and engagement) may therefore be indicative of the underlying power of a strong linear narrative to communicate information.

The (a) Narrative Accordion not only created the most added value but was, overall, the most successful (despite being at a disadvantage on some measures because it contained little visual material), scoring consistently well across most categories. Respondents found it interesting, useful and relatable, and it scored highest for generating confidence in understanding its impact and being able to discuss it with family and friends. Respondents were also very positive about its layout, format and navigation, suggesting that it successfully achieved the right balance between interactivity and narrative engagement.

The (c) Informal Video also scored well overall (especially considering that three of the functional measures were not directly applicable to the video format), indicating that a more playful tone can, as others have found (Hardy et al., Citation2014), enhance public understanding. Indeed, this version had (albeit only marginally) the highest scores for impact on public understanding. The scores may also reflect the advantages of a video format, where messages and narratives can be underpinned by dramatic imagery and action, although it is worth noting that its most positive scores were in those areas where people appear to have responded to the style/tone rather than the format (so it scored highest in terms of relatability, enjoyment and tone).

The original BBC Article - which embodies a traditional and widely used approach to storytelling in online journalism – was the top scorer in only one area, reflecting the quality of its visual content. But in this case, a picture might not - as the saying goes - tell a thousand words. Despite the familiarity of the IP format, its acknowledges undoubted professionalism and strong production values, it compares poorly across many of the key measures in our survey. It is perceived to be the least interesting and least enjoyable and was only the 4th best version in terms of its impact on public understanding. This provides strong additional evidence that the IP is not the most effective model for communicating news. Indeed, the process of creating the prototypes revealed how the IP model’s focus on the moving “newsworthy” aspects of the story – notably the views of politicians – were not especially helpful if the focus was to engage audiences and increase public understanding.

To shed further light on the four alternative models of news, we asked people to make implicit comparisons between the prototypes and traditional IP format, comparing “the design and content of this news article to others you have read in your own time” across six criteria (see ), three of which were also referred to in stand-alone questions. The first four questions have a strong focus on engagement, and by these measures the (c) Informal Video - the most overtly entertaining version with the strongest focus on direct engagement with its audience - performs very strongly. The last two questions are, perhaps, the most fundamental for judging the success of a news story, and while the (c) Informal Video also does well here, the (a) Narrative Accordion is seen as the most useful, and the (b) Plain Text Dramatic as the most informative.

Table 6. Comparing the prototypes with traditional news.

5. Conclusion

These results are suggestive rather than definitive. They raise a number of questions about the lack of a common language about the purpose of news, throwing up a series of potential contradictions. So, for example, suggests that the prototype that was ranked as the least “useful” was also ranked as the most “informative” – when we might have expected the two terms to be more closely related. We are also aware that more work is needed to test the link between different models of news and actual (rather than perceived) levels of public knowledge.

But our research does help establish a strong empirical and theoretical case for the potential in developing new formats for the way we present and communicate news. And they cast further doubt on the conventional wisdom – and long-established journalistic principle – that the IP model of news storytelling is the most succinct and effective way to deliver news to its audience. Even though the BBC was, by some distance, the top news choice for our respondents, the original BBC version was neither succinct (taking longer than most others to consume) nor effective in increasing public confidence (in the subject) or understanding.

We were aware of the possibility that the unfamiliarity of the prototypes - all four moved away from the IP focus on the “moving” or “breaking” element of a story - may work against them, introducing elements of confusion because they did not “look like news’. The fact that users responded immediately to some of these new formats is however indicative of their potential. Even in the brief time available to craft new forms of storytelling, some of our prototypes performed significantly better than the classic, tried and tested pyramid version.

All three of the more successful prototypes contain strong narrative elements, which emerges as perhaps the strongest underlying feature in effective news communication. The overall success of the Narrative Accordion prototype – which combines both narrative with an element of interactivity - might seem to indicate that this was the most effective alternative. However, we see this as the first research and development stage of exploring new forms of news storytelling. The Informal Video version also performed well across most measures, while the Plain Text Dramatic prototype, for all its simplicity, was notably effective in promoting a sense of public understanding.

As Gynnild (Citation2014) suggests, the “most critical factor for journalism’s impact on society in the future is not the accessibility of high-tech tools. It is the professional fostering of news professionals who are intrinsically motivated to explore, contest, and further develop meaningful journalistic approaches within the contexts they are operating.” Just as journalism is defined by changing and dynamic technology, funding models, choice and audiences, the established norms of news making processes must also be less fixed. While the professional norms, habits and preferences exercised by journalists might be much less easy to redefine, our research suggests that it might be innovation in the narrative structure that makes online news more engaging, convenient and useful than the alternatives currently available.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Clwstwr programme (https://clwstwr.org.uk/) under the Creative Industries Clusters Programme of the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund delivered by the Arts and Humanities Research Council on behalf of UK Research and Innovation, and is part of ongoing research and development project in news innovation.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The first workshop was carried out in collaboration with the Ethnic Youth Support Team in Swansea and the second with support of academics at the University of South Wales.

References

- Birkner, T., E. Koenen, and C. Schwarzenegger. 2018. “A Century of Journalism History as Challenge: Digital Archives, Sources, and Methods.” Digital Journalism 6 (9): 1121–1135.

- Bragg, R. 2000. “Weaving Storytelling Into Breaking News.” Nieman Reports 54 (3): 29.

- Bryman, A., S. Becker, and J. Sempik. 2008. “Quality Criteria for Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Methods Research: A View from Social Policy.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 11 (4): 261–276.

- Bull, A. 2007. “Training: A Matter of Degrees.” British Journalism Review 18 (3): 54–59.

- Canavilhas, J. 2007. “Web Journalism: From the Inverted Pyramid to the Tumbled Pyramid.” Biblioteca on-line de ciências da comunicação.

- Chadwick, A. 2017. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. New York: Oxford University Press.

- DeAngelo, T. I., and N. S. Yegiyan. 2019. “Looking for Efficiency: How Online News Structure and Emotional Tone Influence Processing Time and Memory.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (2): 385–405.

- Emde, K., C. Klimmt, and D. M. Schluetz. 2016. “Does Storytelling Help Adolescents to Process the News? A Comparison of Narrative News and the Inverted Pyramid.” Journalism Studies 17 (5): 608–627.

- Giles, B. 2004. “Thinking About Storytelling and Narrative Journalism.” Nieman Reports 58 (1): 3.

- Gynnild, A. 2014. “Journalism Innovation Leads to Innovation Journalism: The Impact of Computational Exploration on Changing Mindsets.” Journalism 15 (6): 713–730.

- Hardy, B. W., J. A. Gottfried, K. M. Winneg, et al. 2014. “Stephen Colbert’s Civics Lesson: How Colbert Super PAC Taught Viewers About Campaign Finance.” Mass Communication and Society 17 (3): 329–353.

- Johnson, R. B., and A. J. Onwuegbuzie. 2004. “Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time has Come.” Educational Researcher 33 (7): 14–26.

- Johnston, M. P. 2017. “Secondary Data Analysis: A Method of Which the Time has Come.” Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries 3 (3): 619–626.

- Keng, C., and H. Ting. 2009. “The Acceptance of Blogs: Using a Customer Experiential Value Perspective.” Internet Research 19 (5): 479–495.

- Kilby, A. 2018. “Provoking the Citizen: Re-examining the Role of TV Satire in the Trump Era.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 1934–1944.

- Kleemans, M., G. Schaap, and M. Suijkerbuijk. 2018. “Getting Youngsters Hooked on News: The Effects of Narrative News on Information Processing and Appreciation in Different Age Groups.” Journalism Studies 19 (14): 2108–2125.

- Knobloch, S., G. Patzig, A.-M. Mende, et al. 2004. “Affective News: Effects of Discourse Structure in Narratives on Suspense, Curiosity, and Enjoyment While Reading News and Novels.” Communication Research 31 (3): 259–287.

- Kosara, R. 2017. “An Argument Structure for Data Stories.” Proceedings of the Eurographics/IEEE VGTC Conference on Visualization: Short Papers, 31–35.

- Lewis, J. 1994. “The Absence of Narrative: Boredom and the Residual Power of Television News.” Journal of Narrative and Life History 4 (1–2): 25–40.

- Lewis, J. 2017. “Quick and Dirty News: The Prospect for More Sustainable Journalism.” In What Is Sustainable Journalism? Integrating the Environmental, Social, and Economic Challenges of Journalism, edited by P. Berglez, U. Olausson, and M. Ots, 3–18. New York: Peter Lang.

- Lewis J., and S. Cushion. (2009) The Thirst To Be First: An Analysis of Breaking News Stories and Their Impact on the Quality of 24-Hour News Coverage in the UK. Journalism Practice 3(3). 304–318.

- Longhurst, R. 2003. “Semi-structured Interviews and Focus Groups.” Key Methods in Geography 3 (2): 143–156.

- Machill, M., S. Köhler, and M. Waldhauser. 2007. “The Use of Narrative Structures in Television News: An Experiment in Innovative Forms of Journalistic Presentation.” European Journal of Communication 22 (2): 185–205.

- Mihelj, S., V. Bajt, and M. Pankov. 2009. “Television News, Narrative Conventions and National Imagination.” Discourse & Communication 3 (1): 57–78.

- Nee, R. C., and A. D. Santana. 2021. “Podcasting the Pandemic: Exploring Storytelling Formats and Shifting Journalistic Norms in News Podcasts Related to the Coronavirus.” Journalism Practice, 1–19.

- Newman, N. 2020. Journalism, Media and Technology Trends and Predictions 2020. Available at: http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/publications/2020/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2020/ (accessed 12 October 2020).

- Norambuena, B. K., M. Horning, and T. Mitra. 2020. “Evaluating the Inverted Pyramid Structure Through Automatic 5W1H Extraction and Summarization.” Proc. of the 2020 Computation+ Journalism Symposium. Computation+ Journalism, 2020, 1–7.

- Ofcom. 2020. News consumption in the UK: 2020. Available at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/201316/news-consumption-2020-report.pdf (accessed 10 October 2020).

- Parasie, S., and E. Dagiral. 2013. “Data-Driven Journalism and the Public Good: “Computer-Assisted-Reporters” and “Programmer-Journalists” in Chicago.” New Media & Society 15 (6): 853–871.

- Pavlik, J. 2000. “The Impact of Technology on Journalism.” Journalism Studies 1 (2): 229–237.

- Pöttker, H. 2003. “News and its Communicative Quality: The Inverted Pyramid—When and Why Did It Appear?” Journalism Studies 4 (4): 501–511.

- Rabe, R. 2007. “Inverted Pyramid.” In Encyclopedia of American Journalism, edited by S. L. Vaughn, 223–225. New York: Routledge.

- Tamul, D. J., J. C. Hotter, S. Vazire, et al. 2019. “Exploring Mechanisms of Narrative Persuasion in a News Context: The Role of Narrative Structure, Perceived Similarity.” Stigma, and Affect in Changing Attitudes. Collabra: Psychology 5 (1): 51.

- Thomson, E. A., P. R. White, and P. Kitley. 2008. ““Objectivity” and “Hard News” Reporting Across Cultures.” Journalism Studies 9 (2): 212–228.

- Ursell, G. D. 2001. “Dumbing Down or Shaping up?” New Technologies, new Media, new Journalism. Journalism 2 (2): 175–196.

- Van Krieken, K. 2018. “Multimedia Storytelling in Journalism: Exploring Narrative Techniques in Snow Fall.” Information 9 (5): 123.

- Van Krieken, K., and J. Sanders. 2019. “What is Narrative Journalism? A Systematic Review and an Empirical Agenda.” Journalism, 1464884919862056.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2020. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 175–194.

- Walters, P. 2017. “Beyond the Inverted Pyramid: Teaching the Writing and all-Formats Coverage of Planned and Unplanned Breaking News.” Teaching Journalism & Mass Communication 7 (2): 9–22.

- Ward, S. 2009. “Journalism Ethics.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen, and T. Hanitzsch, 295–309. New York: Routledge.

- Witschge, T., M. Deuze, and S. Willemsen. 2019. “Creativity in (Digital) Journalism Studies: Broadening our Perspective on Journalism Practice.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 972–979.

- Yaros, R. A. 2006. “Is it the Medium or the Message? Structuring Complex News to Enhance Engagement and Situational Understanding by Nonexperts.” Communication Research 33 (4): 285–309.

- Ytreberg, E. 2001. “Moving out of the Inverted Pyramid: Narratives and Descriptions in Television News.” Journalism Studies 2 (3): 357–371.