ABSTRACT

This study focuses on contributing to the emerging international research agenda regarding press freedom, moving beyond the already established factors that relate to political and industrial norms as influences on press freedom. Its primary goal is to explore the dynamics of influence on press freedom in different media systems of the western world based on a quantitative analysis of data for 2008–2019 in 16 countries. Findings indicate that press freedom in democratic countries is severely challenged and in certain deeply worrying cases, it is steadily declining, whereas factors that influence this decline appear to be common in different, even contradictory, media systems. In addition, by examining the dynamics of influence on press freedom in different media systems, this work attempts to partially contribute to the discussion on the evolution of western media systems as regards their relationship with press freedom.

Introduction

It is often proclaimed that democracy and press freedom go hand in hand. Indeed, press freedom is one of the key concepts and prerequisites for every healthy democracy (e.g., Schramm Citation1964; De Smaele Citation2006; Besley and Prat Citation2006; Norris Citation2006). However, from the USA, the ‘land of the free’, to Greece, the country that created the first democracy in 507 B.C., and from Norway, which in recent years has ranked first in the international democracy indexFootnote1, to the Swiss cantons of Appenzell, Innerrhoden and Glarus, which constitute a rare example of a pure form of direct democracy (Golay Citation2005), press freedom in the western world seems to remain a rather vague concept with blurred boundaries, both as a normative concept (e.g., McQuail Citation2000; Graber Citation2017; Hallin Citation2020) and as an empirical one (Freedom House Citation2019; RSF Citation2020b).

In addition, it seems to remain quite ‘sensitive’ by nature, as it is constantly directly and indirectly influenced by a series of factors/parameters which not only affect its dynamics but also, and primarily, impact overall journalism practice. For most media scholars, it comes as no surprise that this situation is evident not only in authoritarian regimes but also in democratic countries of the western world, although with certain variations. In liberal democracies, press freedom has been seen as a part of a larger group of rights that fall under the umbrella of the right to freedom of speech and freedom of information. In emerging democracies, it takes the shape of a normative ideal of journalists seen as important players in re-establishing democracy and fighting for civil rights (Voltmer Citation2014). In eastern European countries, freedom from authoritarian rule at the end of the twentieth century and the new style of democratic government opened up the possibility for journalists to act as conveyors of news without undue interference from the state (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004; Rupar et al. Citation2019). However, documented research mainly focuses on political factors/parameters that center on the role of the government/state/authorities and the limitations they pose.

This study moves on to assess a series of economic, political and social factors/parameters as well as internal characteristics of the media systems and their impact on the dynamics of press freedom. It is based on the theory of Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004), who introduced three categories of media systems in the western world, moving on to examine four different categories of media systems (based on recent research on the field), each represented by four countries of the western world over a period of eleven years, from 2008 to 2019. Different factors/parameters, both internal (identified with and generated by media systems themselves and their indigenous characteristics), and external (political and economic societal characteristics) are assessed as regards their level of influence on press freedom.

The Pursuit of Defining the Concept of Press Freedom

For hundreds of years, journalists around the world have been harassed, imprisoned, and killed in their efforts to search for trustworthy information (Freedom House Citation2004, Citation2014, Citation2017, Citation2019). The evolution of the western world’s political systems and humanity’s struggle for democracy (Lijphart Citation1968; Lijphart Citation1989; Oloyede Citation2005; Becker, Vlad, and Nusser Citation2007) brought to the fore the crucial role of a free press for every society (Van Belle Citation2000). Yet the notion of press freedom remains a contested issue, increasingly harder to clearly describe and define. Where do the boundaries of press freedom lie? Are there any boundaries at all? Why is it difficult to define a concept which is protected by all democratic constitutions around the world? These are only a few of the questions raised in recent years, which remain largely unanswered.

Early definitions of the concept considered mainly political parameters that delimited press freedom, reflecting post-Second World War geopolitical construction, and focused primarily on freedom from government control (Siebert, Peterson, and Schramm Citation1956). Lowenstein (Citation1970) argued that ‘a completely free press is one in which newspapers, periodicals, news agencies, books, radio and television have absolute independence and critical ability, except for minimal libel and obscenity laws.’ According to Merrill (Citation1981, Citation1990), press freedom means press autonomy, as he argues that ‘maximum journalistic autonomy is the imperative of journalism’ (p.26). Dennis and Merrill (Citation1991) define press freedom as the right to ‘communicate ideas, opinions and information without government constraint’ (p.5) in line with Weaver (Citation1977) and Asante (Citation1997).

More recent studies also center on the role of the state. Curran (Citation1996) differentiates between a classical liberal perspective on media freedom and the radical democratic perspective. The former focuses on the freedom of journalists to publish/broadcast while the latter focuses on how mass communications can ‘mediate in an equitable way conflict and competition between social groups in society’. Within the classical liberal perspective, according to Curran, is a ‘strand’ arguing that the media should serve to protect the individual from the abuses of the state. Within the radical democratic perspective, he continues, is a ‘strand’ that argues that the media should seek to redress the imbalances in society.

In addition to the role of the state, there are also other important aspects of press freedom related to social and cultural matters as well as economic and managerial issues. As early as Citation1971, Githii called for a broadening of the definition of press freedom to embrace powerful social, economic, cultural and managerial factors whose influence can impose limitations on press freedom (p.57) (see also analysis in Asante Citation1997). Several years later, McQuail (Citation2000) said that the concept of press freedom covers both the degree of freedom enjoyed by the media and the degree of freedom and access of citizens to media content. The essential norm is that media should have certain independence, sufficient to protect free and open public expression of ideas and information. The second part of the issue raises the question of diversity, a norm that opposes concentration of ownership and monopoly of control, whether on the part of the state or private media industries (see also analysis in Becker, Vlad, and Nusser Citation2007). As such, the issue of ownership and market forces emerges as a fundamental challenge to press freedom along with rules dictated by media commercialization.

An additional aspect in the pursuit of defining the notion of press freedom emerged outside academic scholarly research. For instance, Freedom House defines press freedom as being linked to the legal environment for the media, political pressures that influence reporting, and economic factors that affect access to information (Freedom House Citation2004). According to RSF, the concept is operationalized as the extent to which legal and political environments, circumstances and institutions permit and promote the ability of journalists to collect and disseminate information unimpeded by physical, psychological or legal attacks and harassment (RSF Citation2020a).

Besides all these aspects related to political and economic factors, the pursuit of defining press freedom also needs to take into serious consideration the fact that there are significant cultural, political and economic differences from one society to another. As such, the criteria under which the notion of press freedom is assessed may vary considerably between different media systems, even amongst those of the western world. For example, around Europe, historical, economic and cultural differences among member-states may allow different interpretations of what constitutes complete and undeniable press freedom (Czepek, Hellwig, and Nowak Citation2009) despite guarantees offered by these countries’ democratic constitutions.

Challenging the Dynamics of Influence on Press Freedom in Different Media Systems

Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004), in their fundamental study of media systems in the western world, identified three different models: the Mediterranean/polarized pluralist (which prevails in the countries of Southern Europe), the North European Democratic/corporatist (which prevails across northern continental Europe) and the North Atlantic/Liberal model (which prevails across the UK, Ireland and the USA). They suggest that media systems can be classified based on four key dimensions: the degree of state intervention in the media, the extent of political parallelism (the degree of media partisanship and the extent of the party system’s reflection on the media), the development of media markets, and the level of journalistic professionalism. Based on these key dimensions, Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004) state:

‘The Liberal model is characterized by a relative dominance of market mechanisms and of commercial media; the Democratic Corporatist model by a historical co-existence of commercial media and media tied to organized social and political groups, and by a relatively active but legally limited role of the state; and the Polarized Pluralist model by integration of the media into party politics, weaker historical development of commercial media and a strong role of the state’ (11).

One of the key features that have driven such variations since 2004 seems to be the rapid development of digital media and communication around the world and the varying pace at which these media evolved in different countries, as well as the public’s access to them. For example, there were – and still are – significant contrasts in internet access even among closely related countries; EurostatFootnote2 estimated that in 2008 more than eight out of ten households had internet access in Sweden and the Netherlands, compared with just four out of ten in Italy and one-third in Greece (Norris Citation2009). Following Norris’s argumentation, Bruggemann et al. (Citation2014) extended and differentiated Hallin and Mancini’s original typology by presenting four empirical types of media systems, namely Northern, Central, Western and Southern media systems. In essence, their study showed that the Southern type is very close to the Polarized pluralist and the Western type is close to the Liberal model; the basic differentiation refers to the Democratic/corporatist model, which seems to correspond to the Northern type (Nordic countries) and the Central type (countries of Central Europe and the UK). Furthermore, the digital media environment seems to have generated a series of limitations for press freedom and journalists around the world, with the most notable one being the high level of online harassment of journalists in terms of press censorship. Waisbord (Citation2020) refers to this phenomenon as ‘mob censorship’, defined as ‘bottom up, citizen vigilantism aimed at ‘disciplining’ journalism, which severely threatens the level of press freedom in western countries.

In addition, socio-political changes that took place after 1989 in several Eastern European countries seem to point towards the emergence of the post-Communist media system, referring to media in post-Communist countries or, as Voltmer (Citation2008) calls them, the ‘new’ democracies (see also analysis in Norris Citation2009). Media in these countries had to negotiate two major stages after 1989: transition and transformation. The first stage refers to transition (violent or otherwise) away from the Communist media system, in which institutional methods of controlling the media prevailed. The second stage refers to the process of transforming the media system to support and enhance democracy (Gross and Jakubowicz Citation2012). Whereas all media systems, at some point, undergo various transformations, these tend to take place gradually and over time; in the case of the post-Communist countries, this transformation was dramatic and sudden, and changes had to take place within a given time framework so the media could support the development of a new socio-political status quo in these countries: transitioning from state-socialism to liberal democracies. Hallin and Mancini (Citation2013) themselves acknowledged that post-Communist countries in Europe were until recently examined by scholars as a separate type of media systems; however, given the fact that research on media in these countries was limited until 1989, it has been hard to study and analyze them – some cases being harder than others (e.g., Russia).

Scholars studying post-Communist media systems tend to agree that these systems present similar characteristics to those of the Mediterranean/polarized pluralist ones (e.g., Voltmer Citation2008). Given that the state continued to have overwhelming power in these countries during the transition period and until recently, all sectors tended to remain quite politicized, to a much greater extent than in Mediterranean countries (Gross Citation2002). In addition, market-based institutions were embraced rapidly in several post-Communist countries while others tended to adopt more Democratic/corporatist media system characteristics (e.g., Estonia). For all these reasons, Hallin and Mancini (Citation2013), along with other scholars in the field (e.g., Voltmer Citation2008), argue that Western models of media systems could not be applied in the case of post-Communist media systems, which were better understood as a separate hybrid type, combining multiple elements of different typologies (Dobek-Ostrowska Citation2015).

Different media systems around the world share a common characteristic: all of them depict the vulnerabilities of the societies within which they operate (Maniou and Ketteni Citation2020). This work mainly focusses on examining the level of privacy protection law existence as well as their content, the degree of media self-censorship, the degree of harassment against journalists, the level of political polarization and political stability in different media systems, as well as the level of economic growth.

Laws and Press Freedom

Attempts in western countries to restrict press freedom have raised serious questions in recent years. The European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, in their study on investigative journalism (Ukrow and Iasino Citation2016), show that while the countries examined protect freedom of expression on the constitutional, statutory and self-regulatory level, restrictive rules on the freedom of the press also exist. In France, the prime minister has the power to extensively monitor the French population without judicial control, which compromises the protection of journalists’ sources and has a potentially chilling effect on whistle-blowers. Poland’s surveillance law passed in 2016 expands the enforcement agencies’ access to citizens’ internet and telecommunication usage data without prior judicial review or approval. Poland has also adopted an anti-terrorism law and a law on public service media, both of which curtail press freedom. Switzerland’s Intelligence Service Act, allowing the Swiss intelligence service to monitor private communications, has also passed a relevant referendum. The Spanish Parliament, likewise, adopted a public security law which allows the government to sanction journalists for taking pictures or filming police forces in the exercise of their duties (Clark and Grech Citation2017; Maniou and Ketteni Citation2020). Furthermore, in recent years, attention has turned to the regulatory frameworks that guide journalists’ behavior, and, in particular, to the notion of public interest and the balance between press freedom and the individual’s right to privacy in the self-regulatory framework of the press (Dawes Citation2014). From this perspective, the important point is not only the existence/absence of privacy laws in each media system but also the content of these laws, as regulatory frameworks present several dissimilarities among western countries.

Journalistic Autonomy, Self-censorship and Harassment Against Journalists

The level of autonomy that journalists enjoy within the media system in which they operate is important and goes beyond the constraints witnessed in western media systems. Attempts to harass journalists are not exclusively conducted by authoritarian regimes, although these are considered direct and are easier to trace. China, Mexico and Turkey show clear evidence of such cases. Journalists in weaker democracies also have less professional autonomy since there is frequently more state interference in the press: for example, Colombia may not be considered an entirely flawed democracy, but journalists working there experience various forms of freedom suppression (Barrios and Miller Citation2020). Barrios and Miller’s work allows us to understand the specific Colombian scenario and how it engenders different forms of self-censorship and circumventing censorship. However, this phenomenon is manifested in different ways in different countries and media systems.

Lofgren-Nilsson and Ornebring (Citation2016) examined the situation in Sweden, a country with strong de facto and de jure safeguards of journalistic freedom. Their findings from a representative survey of Swedish journalists on the extent, forms and consequences of intimidation and harassment show that a third of respondents had experienced threats at work, and an overwhelming majority said they had received offensive and insulting comments. Intimidation and harassment also had consequences, both professionally and personally, such as fear and self-censorship (Maniou and Ketteni Citation2020).

Self-censorship can, in certain cases, have some value for professional journalists but codes of ethics tend to encourage it only as regards sensitive issues (e.g., transmission of unnecessarily violent images, publication of redundant intimate details regarding criminal attacks). In all other cases, self-censorship can be a severe obstacle to a healthy media system and affect the dynamics of influence on press freedom. This study adopts the definition offered by Clark and Grech (Citation2017, 11), who argue that ‘self-censorship is interpreted as the control of what one says or does in order to avoid annoying or offending others but without being told officially that such control is necessary’. In this context, in crisis-ridden countries such as Greece and Spain, the new working environment that has emerged has ousted experienced and more highly paid professionals, resulting in phenomena of insufficient advocacy of the professional relations code and even of the journalistic code of conduct, leading to the ‘pauperization’ of younger trainee journalists. This lack of job security constitutes a source of self-censorship for journalists, causing an internal, self-fueled crisis (Iordanidou et al. Citation2020; Papadopoulou Citation2019; see also analysis in Maniou and Ketteni Citation2020). Self-censorship happens when threats are internalized so that a journalist knows instinctively that a certain subject is too dangerous for coverage and fear strikes (Whyatt Citation2021). Indeed, journalists who self-censor have reported fear and instability in their working conditions (Barrios and Miller Citation2020) both in the Global North and South, while the global pandemic crisis of 2020 seems to have led to the rise of such phenomena around the world, deriving from the exercise of violence in its different forms, either direct or indirect (Papadopoulou and Maniou Citation2021).

Professionalization and Press Freedom

Journalistic autonomy is a key aspect in assessing media systems. It constitutes one of the three primary dimensions of professionalism, along with distinct professional norms (e.g., practical routines) and the public service orientation of journalists (i.e., orientation towards an ethic of public service rather than towards the interests of individuals), according to Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004).

From this perspective, press freedom and professionalization appear to be of equal importance in assessing different media systems. In Mediterranean/polarized pluralist systems, the press remained highly partisan and the level of professionalization was deemed much lower than in Liberal and Democratic/corporatist ones. In fact, around Southern Europe, professionalization was limited by the strong politicization of the press, as actors outside journalism tended to remain in control, and differences within the profession made it difficult to achieve consensus on professional norms (Hallin and Mancini Citation2010, 175). In post-Communist media systems, professionalization varied considerably, although the role of the state remained exceptionally important. For example, in Poland, journalists developed a strong professional culture although this was in some sense characterized as a failed professionalism: the prevalence of censorship, state ownership of the media and political repression meant that journalists were routinely thwarted in attempting to act according to a professional conception of their role. Nevertheless, they did clearly have such a conception: they had a strong sense of distinct identity and of a distinct role in society, and resisted intrusions of outsiders into journalistic work (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). In Russia, on the other hand, in the 1990s journalism lost the moral legitimacy gained in the first years of perestroika and became one of the most publicly criticized professions. After 2000, it was mainly characterized by its blurred boundaries with advertising and its development towards a more market-oriented business model, which made it difficult for Russian journalists to assimilate into the professional environment of Western media systems (Vartanova Citation2012).

Polarization

All the characteristics analyzed so far constitute ‘internal’ factors that may affect the dynamics of influence on press freedom, in the sense that they derive from specific characteristics of every media system. However, there are several other factors that may have an impact on press freedom which can be seen as ‘external’ parameters, in the sense that they derive from broader societal characteristics and, as such, are not affected by the media system but instead can themselves exert some influence on it.

Among the most prominent seems to be the level of polarization within a society, which, in turn, may have a severe impact on the level of media polarization. Polarization may take different forms in different societies, ranging from democratic to authoritarian ones. For example, Hungary is a typical form of a polarized, authoritarian society. During the post-Communist transition, there was a brief period of national unity within Hungarian society as well as within the elite, but the signs of political polarization were apparent from the early years of democracy (Arbatli and Rosenberg Citation2021). The democratic status of the state began to erode in 2010 after the landslide victory of Viktor Orban’s Fidesz (Ágh Citation2013) and, finally, it was declared a competitive authoritarian regime at the beginning of 2020 (Lührmann et al. Citation2018). From 2011 to 2019, its Freedom House ratings dropped from 1 to 3 for both political rights and civil liberties whereas by 2017, its press freedom status was only ‘partly free’ with a score of 44/100 (Freedom House Citation2017, Citation2019).

Moving from authoritarian to democratic regimes, polarization within a society may take different forms, yet it appears to influence the dynamics of press freedom. Several studies have shown that exposure to press coverage of polarization leads people to see society as polarized (e.g., Levendusky and Malhotra Citation2016; Yang et al. Citation2016), as ideologically unambiguous content increasingly attracts audiences who share the hosts’ political leanings, thus reinforcing partisan views. These are important concerns, especially in a heated political climate in which the fringes appear eager to escalate divisive arguments. Yet, there are also theoretical reasons to expect that blatantly partisan messages will leave public opinion mostly unchanged, because citizens may ignore or resist them (Prior Citation2013). Following this line of argumentation, polarization and authoritarianism are not necessarily usually found together, but polarization can also be traced in democratic regimes. For example, in the USA, deep political polarization and its long-term social implications result in both politicians and ordinary people being willing to tolerate undemocratic norms, especially when applied to opposition party members/followers (Arbatli and Rosenberg Citation2021). Although social and political factors surrounding polarization tend to be completely different here in comparison to the Hungarian case, the implications for press freedom are deeply worrying, as explicitly shown throughout the period of the Trump administration.

Political Stability

In accordance with society’s polarization, political stability can play a significant role in press freedom. Early studies in the field have shown a series of positive effects that a free press may have on political stability. Besley, Burgess, and Prat (Citation2002) suggest that a free press helps to overcome the principal-agent problem that typically characterizes the relationship between citizens and their governments; Leeson (Citation2008) finds that where the press is not free people have less political knowledge, whereas fewer regulations and private ownership of media lead to greater political awareness and participation (see also analysis in Pal, Dutta, and Roy S Citation2011). This study deals mainly with the ways in which political stability, among other factors, may affect press freedom. Even in the democratic countries of the western world, political stability cannot always be taken for granted. For example, the Great Recession from 2008 and onwards fueled political crises in several countries, especially in the European South, as did the pandemic crisis of 2020. Greece, Spain and Italy (Morlino and Piana Citation2014), among others, experienced a series of societal riots after 2010 that tested their political stability and in some cases led to early elections and governmental overturns (e.g., Greece after 2015). The role of the press in these periods of political instability and the level of freedom it enjoyed remains largely understudied.

Level of Economic Growth

The final factor examined in the study is the level of economic growth and its effects on press freedom, which is significantly differentiated among the countries of the western world. Economic growth usually depicts the economic level of the state and its residents. The existence of a bidirectional relationship between press freedom and economic growth has already been established by previous studies (e.g., Alam and Ali-Shah Citation2013). However, what remain largely understudied are the different effects of economic growth on press freedom in different western countries and their media systems. Economic growth and development progress at different paces in different countries; accordingly, based on its level of economic growth, every country’s media system presents different characteristics in terms of organization and ownership models. Accordingly, these characteristics can result in different levels of press freedom. For example, the press in Italy traditionally suffers from high ownership concentration and lower (in comparison with other advanced democracies) freedom of the press; both characteristics became much more evident after the Great Recession of 2008 (Morlino and Piana Citation2014). In the EU countries, documented research shows that the overall decline in economic growth (due to the economic crisis) has coincided with a significant decline in press freedom, from the South to the North (Dunham and Csaky Citation2013).

Rqs and Scope of Study

The study seeks to address the following research questions:

RQ1. Which factors/parameters affect the levels of press freedom in different media systems of the western world?

RQ2. What are the differences/similarities in the dynamics of influence on press freedom in different media systems of the western world?

Method and Sample

The study is based on a quantitative analysis of data from the period 2008–2019 for 16 countries: the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Finland, the USA, the UK, Ireland, Canada, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland and Hungary. For the purposes of the study, the selected countries were divided into three groups based on the characteristics of their media system, following Hallin and Mancini’s (Citation2004) fundamental study; additionally, a fourth group including media systems in post-Communist European countries was added (Hallin and Mancini Citation2013). The categorization of countries into the four groups of the study is presented in .

Table 1. The groups of countries (national media systems) used for the study.

The dependent variable used in the analysis is Press freedom and derives from the Press Freedom Index (RSF Citation2020a). The Index ranks 180 countries and regions according to the level of freedom available to journalists. It is a snapshot of the media freedom situation based on an evaluation of pluralism, independence of the media, quality of legislative framework and safety of journalists in each country and region. It does not rank public policies even if governments obviously have a major impact on their country’s ranking. Nor is it an indicator of the quality of journalism in each country or region. Ever since the 2013 index, countries have been given scores ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 being the best possible score and 100 the worst. This makes the index more informative and makes it easier to compare one year to another. To better understand and analyze the findings, this variable was reversed and thus in the analysis that follows, a higher number indicates a better score with respect to press freedom, while a lower number indicates a worse score.

The independent variables for the study include the degree of harassment against journalists, the degree of media self-censorship, the level of privacy protection law existence, the content of privacy protection law, the level of political polarization and political stability in the societies (countries) examined, as well as the level of economic growth. The first five independent variables derive from the V-dem (Varieties of Democracy) Project, which is one of the largest social science databases, containing over 19 million data points.Footnote3 Approximately half of the indicators are based on factual information obtainable from official documents and the other half consists of experts’ assessments; typically, five experts per country provide ratings (Coppedge et al. Citation2020). The V-Dem project is a survey based on questionnaires, offering a multidimensional and disaggregated dataset that covers all countries (and some dependent territories) from 1789 to the present. The project distinguishes between five high-level principles of democracy: electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian, and collects data to measure these principles. The 450 V-Dem specific indicators listed in the V-Dem Codebook fall into four main types. The independent variables, selected for this work, fall in the Type C data, that include evaluative indicators based on multiple ratings provided by experts (academics and/or professionals working in the media and public affairs, senior analysts, judges). The majority of C-type questions are ordinal: they require country experts to rank cases on a discrete scale and use Bayesian item response theory (IRT) modeling techniques. The V-Dem uses this strategy to convert the ordinal responses experts provide into continuous estimates of the concepts being measured. The basic logic behind these models is that an unobserved latent trait exists, but they are only able to see imperfect manifestations of it. Taking all these manifest items (expert ratings) together can provide an estimate of the trait. The IRT models used allow for the possibility that experts may have different thresholds for their ratings. These thresholds are estimated based on patterns in the data and then incorporated into the final latent estimate. In this way, they can correct for the previously discussed concern that one expert’s ‘somewhat’ may be another expert’s ‘weakly’ (a concept known as Differential Item Functioning). Apart from experts having different thresholds for each category, they also allow for their reliability (in IRT terminology, their ‘discrimination parameter’) to idiosyncratically vary in the IRT models, based on the degree to which they agree with other experts. Experts with higher reliability have a greater influence on concept estimation, accounting for the concern that not all experts are equally expert on all concepts and cases (Coppedge et al. Citation2020).

Analytically, as regards the independent variables of the study:

The degree of Harassment against journalists is a variable generated by the question ‘Are individual journalists harassed — i.e., threatened with libel, arrested, imprisoned, beaten, or killed — by governmental or powerful nongovernmental actors while engaged in legitimate journalistic activities?’. The variable is ordinal, converted to an interval by the measurement model and ranges from 0.77–3.04 (Pemstein et al. Citation2020). Responses ranged from 0 (no journalist dares to engage in journalistic activities that would offend powerful actors because harassment or worse would be certain to occur) to 4 (journalists are never harassed by governmental or powerful non-governmental actors while engaged in legitimate journalistic activities).

The degree of Media self-censorship is a variable generated by the question ‘Is there self-censorship among journalists when reporting on issues that the government considers politically sensitive?’ The variable is ordinal, converted to an interval by the measurement model, and ranges from −0.3–2.83 (Pemstein et al. Citation2020). Responses ranged from 0 (self-censorship is complete and thorough) to 3 (there is little or no self-censorship among journalists).

The level of Privacy protection law existence is a variable generated by the question ‘Does a legal framework to protect Internet users’ privacy and their data exist?’ and is a dichotomous variable (yes-no) (Pemstein et al. Citation2019, 21; Mechkova et al. Citation2019).

Content of privacy protection law is a variable generated by the question ‘What does the legal framework to protect Internet users’ privacy and their data stipulate?’ It is an ordinal variable converted to an interval by the measurement model, and ranges from 1.40–2.00 (Pemstein et al. Citation2020). Responses ranged from 0 (the legal framework explicitly allows the government to access any type of personal data on the internet) to 4 (the legal framework explicitly allows the government to access personal information on the internet only in extraordinary circumstances).

The level of Political polarization is a variable generated by the question ‘Is society polarized into antagonistic, political camps?’. Here the variable refers to the extent to which political differences affect social relationships beyond political discussions. Societies are considered to be highly polarized if supporters of opposing political camps are reluctant to engage in friendly interactions, for example, in family functions, civic associations, leisure activities and workplaces. Responses ranged from 0 (not at all, supporters of opposing political camps generally interact in a friendly manner) to 4 (yes, to a large extent, supporters of opposing political camps generally interact in a hostile manner). It is an ordinal variable, converted to an interval by the measurement model (Pemstein Citation2020) and ranges from −2.56–2.60.

Additionally, the level of political stability for every country and year examined was added to the independent variables, as specified by the World Governance Indicators Project (WGI).Footnote4 The level of Political stability in the countries examined is a variable that derives from the WGI dataset and combines several indicators which measure perceptions of the likelihood that the government in power will be destabilized or overthrown by possibly unconstitutional and/or violent means, including domestic violence and terrorism (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Citation2016). The variable ranges from −0.47–1.46.

Finally, the year 2008 is used here as a landmark point, as it was the year the Great Recession started showing signs around the western world; as the 16 countries under study were affected to differing degrees, the period after the Great Recession is deemed appropriate to examine whether the level of economic growth affects press freedom in each country.

From this perspective, the level of GDP per capita (euro per capita) for every country and every year examined was added to the study’s matrix as an independent variable, as specified by the EUROSTAT.Footnote5 The indicator is calculated as the ratio of real GDP to the average population of a specific year. GDP measures the value of total final output of goods and services produced by an economy within a certain period of time. It includes goods and services that have markets (or which could have markets) and products which are produced by general government and non-profit institutions. It is a measure of economic activity and is also used as a proxy for the development in a country’s material living. The variable ranges from 7,400–81,923 (all data). The economic expansion, development, and prosperity of a country is usually measured by the growth rate of GDP per capita (Barro and Sala-i-Martin Citation2004). A country’s level of GDP per capita may be higher than others, but the growth of GDP per capita might remain stable, which would suggest that the country is not experiencing expansion of its GDP; while a country with lower levels might have an increasing rate of GDP, indicating higher economic growth. To capture the growth of GDP per capita in the analysis, the logarithm of the variable is used in the study.

Findings

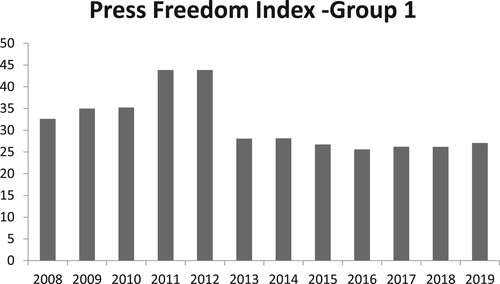

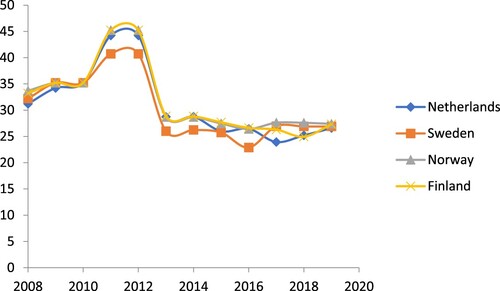

The study initiates from a time series analysis, taking into consideration the mean measure for each group of countries for the dependent variable Press freedom. As clearly depict, in the aftermath of the Great Recession – and especially after 2013 – year on year press freedom has continued to decrease in almost all countries examinedFootnote6 (as already stated in the Method section, in the Press Freedom Index, the higher the number assigned to a country, the higher its level of press freedom). Analytically, in the democratic-corporatist countries (Group 1 - Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Finland) the press freedom indicator shows a higher level of freedom than the other countries of the western world, although it has been decreasing since 2013. The individual country analysis showed (See Figure A1, Appendix) that press freedom in all countries of the Group decreased rapidly after 2011, while Finland and the Netherlands presented a slight increase after 2017.

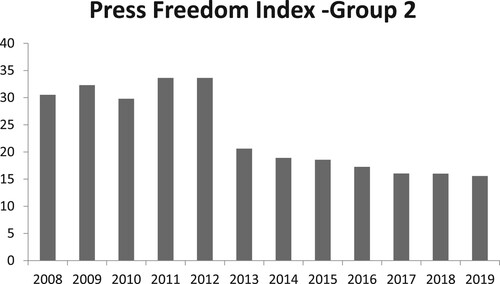

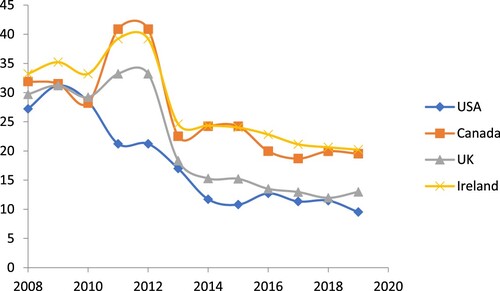

Although the liberal media systems of Group 2 countries (the USA, the UK, Canada, and Ireland) seem to be in a slightly better place than Groups 3 (Polarized pluralists) and 4 (post-Communist) countries, they have also experienced a rapid decline in press freedom levels, especially since 2012. Individual country analysis has shown (see Figure A2, Appendix) that the UK was the only country with a slight increase in press freedom after 2018 .

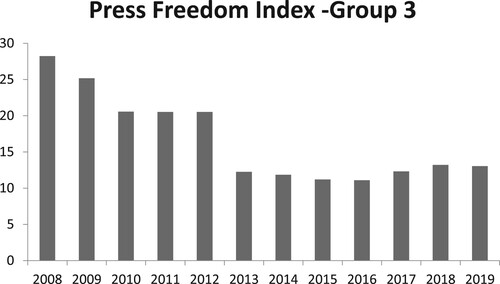

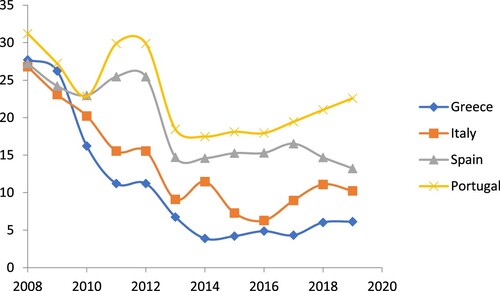

Whereas after 2008, press freedom levels seem to be gradually declining in the Polarized pluralist media systems of Group 3 countries (Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Italy), notably there is a slight but growing tendency towards increased press freedom after 2015. This is the only group that shows indices of increasing press freedom in recent years. This is mainly due to the impressive rise of press freedom in Portugal after 2016 (see Figure A3, Appendix), a finding that corresponds with other studies in the field (Bruggemann et al. Citation2014). It is worth noting that for the same period (2015-19) the Polarized pluralists seem to enjoy similar levels of press freedom as the Liberal countries.

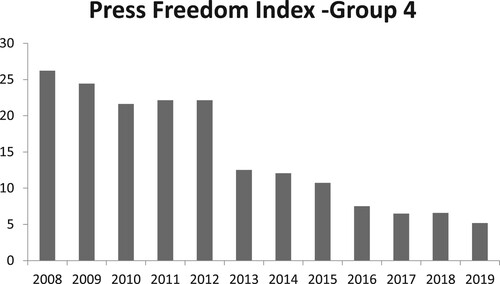

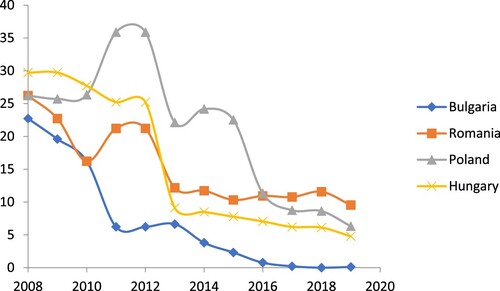

Finally, the post-Communist media systems in the countries of Group 4 (Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, and Romania) appear to be the most ‘problematic’ in terms of press freedom levels. clearly shows that press freedom steadily declines throughout the period examined for all countries examined (see Figure A4, Appendix).

Regression Analysis

A regression analysis was conducted to identify the effects of the independent variables on press freedom for each group of countries examined. As the analysis has shown, in Democratic/corporatist media systems it is primarily political stability that affects the level of press freedom, with harassment of journalists also an important factor. In these media systems, the effects of the economic crisis do not seem to influence press freedom .

Table 2. Regression analysis for Democratic-corporatist media systems.

In Liberal media systems, press freedom seems to have been significantly affected by all independent variables examined except political stability. From this perspective, although Liberal media systems (Group 2 countries) tend to exhibit several characteristics common to Democratic/corporatists (Group 1 countries), these do not include levels of press freedom .

Table 3. Regression analysis for Liberal media systems.

In the Polarized pluralist media systems, on the other hand, the levels of media freedom seem to be affected mainly by two independent variables: the polarization of society and the country’s economic problems, as depicted in the level of economic growth. As shown in , harassment of journalists and media self-censorship do not seem to influence the levels of press freedom.

Table 4. Regression analysis for Polarized pluralist media systems.

Finally, in the post-Communist media systems self-censorship, the existence/absence of privacy protection laws, the polarization of society and the level of economic growth are of equal importance as regards the level of press freedom. On the other hand, harassment of journalists, the content of privacy laws, and the level of political stability do not seem to influence levels of press freedom.

Table 5. Regression analysis for post-Communist media systems.

As regards the relationship between polarization and press freedom, shows that there seems to exist a positive relationship between the two variables in three of the four groups of media systems examined, namely Liberal, Polarized pluralists and, to a lesser degree, Democratic/corporatists. A positive relationship indicates that when polarization increases in these countries, so does press freedom.

Table 6. Polarization and press freedom.

Discussion

How are the dynamics of influence on press freedom affected by different social, political and economic characteristics in the context of different media systems? This analysis has shown that there are different parameters that influence, to different degrees, the dynamics of press freedom in the context of different media systems examined. However, there seems to exist a specific set of characteristics that can affect press freedom in every media system. With the exception of the Democratic/corporatist countries (Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, and Finland), the primary factors affecting press freedom in all other countries examined are economic growth and the level of societal polarization (with the exception of post-Communist countries). As regards polarization, it seems to have led to increased press freedom in all countries examined, with the exception of the post-Communist ones, in which societal polarization does not seem to affect the level of press freedom. As regards economic growth, this finding indicates that the economic crisis after the Great Recession of 2008 seems to have negatively affected the level of press freedom in the countries examined in this work, with the exception of Democratic/corporatists, which were the ones to suffer the least economic effects; however, this work also acknowledges a series of other factors that affected the levels of press freedom.

As such, secondary factors that seem to affect press freedom are the existence (Liberal media systems, post-Communist media systems) and content (Liberal media systems) of privacy laws as well as media self-censorship (Liberal media systems, post-Communist media systems). Harassment of journalists is an additional significant factor in Liberal and Democratic/corporatist media systems. These findings point towards the direction of problematic professionalization norms, especially in the case of Liberal countries. As already analyzed in the theoretical section, levels of self-censorship and journalists’ harassment are directly related to the professional culture exhibited by journalists in their everyday work. Whereas in the case of post-Communist countries these findings could perhaps be expected, it seems deeply worrying that professional norms in recent years are affecting levels of press freedom in Liberal countries, which have also declined significantly in the Press Freedom Index (Freedom House Citation2019).

Finally, political stability seems to affect press freedom only in Democratic/corporatist media systems, which historically tend to enjoy a more stable political environment. Press freedom in these countries seems to be affected by the level of political stability, whereas in countries which traditionally experience a more ‘unstable’ political environment, this does not affect the levels of press freedom as a primary factor.

What seems to be arising as a deeply worrying situation is that countries with traditionally liberal media systems (the USA, the UK, Ireland, and Canada) have in recent years (mainly after 2013) tended to exhibit characteristics as regards the influence on press freedom that bear some similarity to post-Communist media systems. In particular, media self-censorship, the existence of privacy protection laws, the polarization of society and the level of economic growth seem to severely impact the dynamics of press freedom in both types of media systems. This situation, especially in the case of the USA, was primarily associated with attempts by the government to inhibit reporting on national security issues (Freedom House Citation2014). The study’s findings indicate that these attempts were merely the tip of the iceberg, as several other parameters were of equal importance in the process of press freedom deterioration (e.g., economic growth and media self-censorship), identifying a tendency of the US media system towards a hybrid, Polarized-Liberal direction, in line with the findings of Nechushtai (Citation2018).

On the other hand, the Polarized pluralist media systems, which historically have borne a lot of criticism and debate as regards the level of press freedom they enjoy, gradually (after 2015) seem to have rid themselves of past poor practices and moved towards more liberal press roles. In fact, the countries of the Mediterranean South that were severely hit by the economic crisis seem to be gradually freeing themselves from their negative aspects: harassment of journalists, media self-censorship and political instability no longer seem to be affecting the dynamics of press freedom. This is an important aspect of the study. For many years, the media systems of Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece seemed to have been burdened with their countries’ turbulent political past, which had resulted in severe governmental control of media and journalists, both directly and indirectly (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004; Berges Citation2017; Costa e Silva and Sousa Citation2017; Papathanassopoulos Citation2007; Papadopoulou Citation2019). Accordingly, the advent of the Great Recession after 2008 had a severe impact on the media systems of the Mediterranean South (Balcytiene and Juraite Citation2015; Berges-Saura and Papathanassopoulos Citation2015) and, gradually, they suffered certain effects in terms of management and organization, which entailed losses in readership/viewership, advertising revenue and overall profits, endangering their survival and future prospects (Maniou and Seitanidis Citation2018). Notably, these effects did not impact on a decrease of press freedom but, on the contrary, the press seems to enjoy today more freedom than ever before, especially in the case of Portugal and, to a lesser degree, Italy (see Figure A3, Appendix). This was evident especially after 2015, when rising anti-government demonstrations received a great deal of press coverage resulting in several cases in the rise of opposing political parties (e.g., PODEMOS in Spain, SYRIZA in Greece) (Maniou and Bantimaroudis Citation2021). What seems to remain unaltered in the countries of the European South is the level of societal polarization, which severely impacts press freedom. Overall, these findings indicate that the dynamics of influence on press freedom in media systems of the western world do not relate mainly or solely to external characteristics of the media systems, but internal characteristics of these media systems play an equal or – in some cases – even more significant role.

This work indicates that there seems to exist a positive relation between polarization and press freedom in three out of the four groups of media systems examined, namely Liberal, Polarized pluralist and, to a lesser degree, Democratic/corporatist media systems. In practice, this can be observed as a tendency towards an increase in press freedom when increased polarization is exhibited. However, this does not seem to be the case for post-Communist media systems, where the opposite situation prevails and press freedom increases (or decreases) independently of the level of the society’s polarization.

Another important aspect of this study concerns the dynamics of influence on press freedom in the Democratic/corporatist countries. Finland, Netherlands, Sweden, and Norway historically preserve the top-ranking places in the Press Freedom Index. However, since 2013 the levels of press freedom in these countries have been steadily declining, whereas incidents of journalists’ harassment have been steadily increasing (Lofgren-Nilsson and Ornebring Citation2016). As this analysis has demonstrated, journalists’ harassment and political stability seem to influence the levels of press freedom in these media systems.

Conclusions

This study represents a step in a broader research agenda regarding press freedom in different media systems and its dynamics of influence. Thus, it focuses on contributing to the growing new research agenda regarding press freedom in countries of the western world, moving beyond the already established factors that relate to political and industrial norms as influences on press freedom. Finally, although not included in its initial aims, by examining the dynamics of influence on different media systems this work partially contributes to the discussion on the evolution of western media systems as regards their relationship with press freedom.

Based on the findings of the study, press freedom in several countries of the western world is severely challenged and in certain deeply worrying cases, it is steadily declining, whereas parameters and factors that influence this decline appear to be common in completely different, even contradictory, media systems.

First, several decades after the Cold War –when the USA invested millions of dollars in the economic, technological and political battle against communist ideology and practice – today the Liberal countries’ media systems find themselves having to cope with similar ‘demons’ to their post-Communist counterparts. Press freedom in both categories of media systems is under attack and its dynamics are severely affected by similar characteristics: media self-censorship, the existence and content of privacy protection laws, the polarization of society and the level of economic growth are identified here as the most important. In the case of the US, this could be attributed to the growing tendency of the US media system towards a hybrid form of a Polarized-Liberal system (Nechushtai Citation2018), whereas the move towards the Polarized pluralist model for post-Communist countries had been acknowledged many years earlier (Voltmer Citation2008).

Second, media systems of the polarized European South, although deeply affected by the profound economic crisis after 2008, seem to be experiencing a gradual but steady increase in the levels of press freedom, for the first time in their long history: Portugal is the most prominent case, with Italy following close behind. This finding highlights indices for a gradual ‘coming of age’ of these media systems, which finally seem to be able to free themselves from the negative characteristics of their turbulent past. This is not to say that the Polarized pluralist media systems of the European South have managed to alter their structural characteristics, but rather that they seem to be gradually following an alternative course of development. More in-depth and longitudinal research in the years to come will be needed to monitor and assess these national systems and their developmental progress, and conclude as to whether this is a short or a long term structural change.

Finally, findings for the Democratic/corporatist media systems point towards a need to reassess economic, political and societal factors/parameters that seem to influence their levels of press freedom, as well as several of their internal characteristics that seem to affect it, journalists’ harassment being the most prominent. In line with other recent studies in these countries (e.g., Lofgren-Nilsson and Ornebring Citation2016), this work suggests that press freedom is increasingly challenged, although to a lesser degree in comparison to the other groups of countries examined.

Although the main aim of the study was to identify the extent to which different factors affect the levels of press freedom in different media systems of the western world, this work initiated from theoretical questions as regards the boundaries of press freedom and the difficulties in defining this fundamental concept in countries of the western world. As this study showed, different parameters affect to different extents both the concept of press freedom itself and its boundaries: for example, self-censorship, journalists’ harassment and law restrictions vary considerably among the countries examined, as does their level of influence upon press freedom. As such, press freedom can be described in various forms, based on socio-political differences and variations in professional cultures in the countries examined and, therefore, these questions need additional research to be thoroughly assessed.

From this perspective, this work presents certain limitations, especially as regards both journalistic professional cultures and the content of privacy laws that seem to affect press freedom in western countries. As this work has shown, a new, interdisciplinary field for research arises in the intersection of journalism professional practice and legal studies, which can offer great research potential as regards the dynamics of influence on press freedom in the years to come.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 Available at: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu

6 For more detailed analysis regarding press freedom in every country examined, please see the Appendix.

References

- Ágh, A. 2013. “The Triple Crisis in Hungary: The “Backsliding” of Hungarian Democracy After Twenty Years.” Romanian Journal of Political Sciences 13 (1): 25–51.

- Alam, A., and S. Z. Ali-Shah. 2013. “The Role of Press Freedom in Economic Development: A Global Perspective.” Journal of Media Economics 26 (1): 4–20.

- Arbatli, E., and D. Rosenberg. 2021. “United We Stand, Divided We Rule: How Political Polarization Erodes Democracy.” Democratization 28 (2): 285–307.

- Asante, C. 1997. Press Freedom and Development: A Research Guide and Selected Bibliography (No. 11). London: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Balcytiene, A., and K. Juraite. 2015. “Systemic Media Changes and Social and Political Polarization in Europe.” In European Media in Crisis: Values, Risks and Policies, edited by J. Trappel, J. Steemers, and B. Thomass, 20–44. London: Routledge.

- Barrios, M. M., and T. Miller. 2020. “Voices of Resilience: Colombian Journalists and Self-Censorship in the Post-Conflict Period.” Journalism Practice 15 (10): 1423–1440.

- Barro, R. J., and X. Sala-i-Martin. 2004. Economic Growth. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Becker, L. B., T. Vlad, and N. Nusser. 2007. “An Evaluation of Press Freedom Indicators.” International Communication Gazette 69 (1): 5–28.

- Berges-Saura, L., and S. Papathanassopoulos. 2015. “European Communication and Information Industries in Times of Crisis: Continuities and Transformations.” In European Media in Crisis: Values, Risks and Policies, edited by J. Trappel, J. Steemers, and B. Thomass, 45–63. London: Routledge.

- Berges, L. 2017. “Spain: Traces of the Authoritarian Past or Signals of a Western Neoauthoritarian Future.” In Media in Third-Wave Democracies: Southern and Central/Eastern Europe in a Comparative Perspective, edited by P. Bajomi-Lázár, 109–135. Budapest: L’Harmattan.

- Besley, T., R. Burgess, and A. Prat. 2002. “Mass Media and Political Accountability.” In The Right to Tell – Role of Mass Media in Economic Development, edited by R. Islam, 45–60. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Besley, T., and A. Prat. 2006. “Handcuffs for the Grabbing Hand? Media Capture and Government Accountability.” American Economic Review 96 (3): 720–736.

- Bruggemann, Michael, Sven Engesser, Florin Büchel, Edda Humprecht, and Laia Castro 2014. “Hallin and Mancini Revisited: Four Empirical Types of Western Media Systems.” Journal of Communication 64 (6): 1037–1065.

- Clark, M., and A. Grech. 2017. Journalists Under Pressure: Unwarranted Interference, Fear and Self-Censorship in Europe. Brussels: Council of Europe.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, and Michael Bernhard, et al. 2020. “V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v10.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Goteborg: University of Goteborg.

- Costa e Silva, E., and H. Sousa. 2017. “Portugal: The Challenges of Democratization.” In Media in Third-Wave Democracies: Southern and Central/Eastern Europe in a Comparative Perspective, edited by P. Bajomi-Lázár, 90–108. Budapest: L’Harmattan.

- Curran, J. 1996. “Media and Democracy: The Third Route.” In Media and Democracy, edited by M. Bruun, 53–76. Oslo: University of Oslo Press.

- Czepek, A., M. Hellwig, and E. Nowak. 2009. Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Dawes, S. 2014. “Press Freedom, Privacy and the Public Sphere.” Journalism Studies 15 (1): 17–32.

- Dennis, E. E., and J. C. Merrill. 1991. Media Debates: Issues in Mass Communication. New York: Addison-Wesley Longman.

- De Smaele, H. 2006. “In the Name of Democracy.” In Mass Media and Political Communication in New Democracies, edited by K. Volmer, 35–48. London: Routledge.

- Dobek-Ostrowska, B. 2015. “25 Years After Communism: Four Models of Media and Politics in Central and Eastern Europe.” In Democracy and Media in Central and Eastern Europe 25 Years On, edited by B. Dobek-Ostrowska and M. Glowaski, 11–44. London: Peter Lang.

- Dunham, J., and Z. Csaky. 2013. “The European Economic Crisis has Coincided with a Decline in Press Freedom in the EU.” LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog. http://www.eprints.Ise.ac.uk/72633/.

- Freedom House. 2004. Freedom in the World 2003: Survey Methodology. Washington, DC: Freedom House.

- Freedom House. 2014. Media Freedom Hits a Decade Low. Washington, DC: Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2014/media-freedom-hits-decade-low.

- Freedom House. 2017. Freedom of the Press. Washington, DC: Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/freedom-press-2017.

- Freedom House. 2019. Freedom in the World. Washington, DC: Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2019.

- Githii, G. 1971. “Press Freedom in Kenya.” In Reporting Africa, edited by O. Stokke, 57–65. Uppsala: The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies.

- Golay, V. 2005. Institutions Politiques Suisses. Paris: LEP Editions Loisirs et Pédagogie.

- Graber, D. A. 2017. “Freedom of the Press.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, edited by K. Kenski and K. Hall-Jamieson, 237–248. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gross, P. 2002. Entangled Evolutions: Media and Democratization in Eastern Europe. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Gross, P., and K. Jakubowicz. 2012. Media Transformations in the Post-Communist World: Eastern Europe's Tortured Path to Change. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

- Hallin, D. C. 2020. “Press Freedom and its Context.” In Rethinking Media Research for Changing Societies, edited by M. Powers and A. Russell, 54–63. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2010. “Western Media Systems in Comparative Perspective.” In Media and Society, edited by J. Curran, 167–186. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2013. “Comparing Media Systems Between Eastern and Western Europe.” In Media Transformations in the Post-Communist World: Eastern Europe’s Tortured Path to Change, edited by P. Gross and K. Jakubowicz, 15–32. Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2017. “Ten Years After Comparing Media Systems: What Have We Learned?” Political Communication 34 (2): 155–171.

- Hardy, J. 2012. “Comparing Media Systems.” In Handbook of Comparative Communication Research, edited by F. Esser, and T. Hanitzch, 185–206. London: Routledge.

- Iordanidou, Sofia, Emanouil Takas, Leonidas Vatikiotis, and Pedro Garcia 2020. “Constructing Silence: Processes of Journalistic (Self-) Censorship During Memoranda in Greece, Cyprus, and Spain.” Media and Communication 8 (1): 15–26.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aaart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2016. “Worldwide Governance Indicators project.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No.41419. https://ssrn.com/abstract = 965077.

- Leeson, P. T. 2008. “Media Freedom, Political Knowledge, and Participation.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22 (2): 155–169.

- Levendusky, M., and N. Malhotra. 2016. “Does Media Coverage of Partisan Polarization Affect Political Attitudes?” Political Communication 33 (2): 283–301.

- Lijphart, A. 1968. “Typologies of Democratic Systems.” Comparative Political Studies 1 (1): 3–44.

- Lijphart, A. 1989. “Democratic Political Systems: Types, Cases, Causes, and Consequences.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 1 (1): 33–48.

- Lofgren-Nilsson, M., and H. Ornebring. 2016. “Journalism Under Threat: Intimidation and Harassment of Swedish Journalists.” Journalism Practice 10 (7): 880–890.

- Lowenstein, R. 1970. “Press Freedom as a Political Indicator.” In International Communication, Media, Channels, Functions, edited by H. D. Fischer, and J. C. Merrill, 129–142. New York: Hastings House.

- Lührmann, Anna, Siriane Dahlum, Staffan Lindeberg, Aura Maxwell, Valeriya Mechkova, Moa Olin, Shreeya Pillai, et al. 2018. V-Dem Annual Democracy Report 2018. Democracy for All?. https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/3f/19/3f19efc9-e25f-4356-b159-b5c0ec894115/v-dem_democracy_report_2018.pdf.

- Maniou, T. A., and P. Bantimaroudis. 2021. “Hybrid Salience: Examining the Role of Traditional and Digital Media in the Rise of the Greek Radical Left.” Journalism 22 (4): 1127–1144.

- Maniou, T. A., and E. Ketteni. 2020. “The Impact of the Economic Crisis on Media Corruption: A Comparative Study in South and North Europe.” International Communication Gazette 84 (1): 66–89. doi:10.1177/1748048520942751.

- Maniou, T. A., and I. Seitanidis. 2018. “Television Beyond Digitalization: Economics, Competitiveness and Future Perspectives.” International Journal of Digital Television 9 (2): 105–123.

- McQuail, D. 2000. Mass Communication Theory. London: Sage.

- Mechkova, V., Daniel Pemstein, Brigitte Seim, and Steven Wilson. 2019. Measuring Internet Politics: Introducing the Digital Society Project (DSP) (No. 1). Digital Society Project Working Paper.

- Merrill, J. C. 1981. “El Periodista ‘Apolonisíaco’.” In Ensayo Sobre la Moral de los Medios Masivos de Comunicación, edited by La Prensa y la Ética, M. C. Merrill, and R. D. Barney, 134–150. Buenos Aires: Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires.

- Merrill, J. C. 1990. The Imperative of Freedom: A Philosophy of Journalistic Autonomy. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Morlino, L., and D. Piana. 2014. “Economic Crisis in a Stalemated Democracy: The Italian Case.” American Behavioral Scientist 58 (12): 1657–1682.

- Nechushtai, E. 2018. “From Liberal to Polarized Liberal? Contemporary U.S. News in Hallin and Mancini’s Typology of News Systems.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (2): 183–201.

- Norris, P. 2006. “The Role of the Free Press in Promoting Democratization, Good Governance and Human Development.” Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, April 20–22

- Norris, P. 2009. “Comparative Political Communications: Common Frameworks or Babelian Confusion?” Government and Opposition 44 (3): 321–340.

- Oloyede, I. B. 2005. “Press Freedom: A Conceptual Analysis.” Journal of Social Sciences 11 (2): 101–109.

- Pal, S., N. Dutta, and S. Roy S. 2011. “Media Freedom, Socio-political Stability and Economic Growth.” http://esnie.org/pdf/textes_2011/Dutta-Media-Freedom.pdf.

- Papadopoulou, L. 2019. “Democracy and Media Transparency: Systemic Failures in Greek Radio Ecosystem and the Rise of Alternative and Radical Web Radio.” In Transparencia, Mediatica, Oligopolios, y Democracia, edited by M. Chaparro-Escudero, 211–218. Madrid: Comunicacion Social.

- Papadopoulou, L., and T. A. Maniou. 2021. “‘Lockdown’ on Digital Journalism? Mapping Threats to Press Freedom During the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1344–1366. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1945472.

- Papathanassopoulos, S. 2007. “The Mediterranean/Polarized Pluralist Media Model Countries: Introduction.” In European Media Governance: National and Regional Dimension, edited by G. Terzis, 191–200. Bristol: Intellect.

- Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yin-TinG Wang, Joshua Krusell, and Farhad Miri. 2019. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-national and Cross-temporal Expert-coded Data.” V-Dem Working Paper No. 21, 4th edition. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

- Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yin-TinG Wang, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, and Jon von Romer. 2020. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-national and Cross-temporal Expert-coded Data.” V-Dem Working Paper No. 21, 5th edition. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

- Prior, M. 2013. “Media and Political Polarization.” Annual Review of Political Science 16 (1): 101–127.

- RSF. 2020a. “Detailed Methodology.” Press Freedom Index. http://www.rsf.org/en/detailed-methodology.

- RSF. 2020b. The World Press Freedom Index. https://rsf.org/en/world-press-freedom-index.

- Rupar, V., A. Němcová Tejkalová, F. Láb, and S. Seizova. 2019. “Journalistic Discourse of Freedom: A Study of Journalists’ Understanding of Freedom in the Czech Republic and Serbia.” Journalism 22 (6): 1431–1449.

- Schramm, W. 1964. Mass Media and National Development: The Role of Information in the Developing Countries. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Siebert, F. S., T. Peterson, and W. Schramm. 1956. Four Theories of the Press. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Ukrow, J., and G. Iasino. 2016. Comparative Study on Investigative Journalism. Germany: European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. http://www.ecpmf.eu/archive/news/legal/investigative-journalism-new-comparative-study-on-legal-regulationsacross-europe.html.

- Van Belle, D. A. 2000. Press Freedom and Global Politics. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Vartanova, E. 2012. “The Russian Media Model in the Context of Post-Soviet Dynamics.” In Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, edited by D. C. Hallin and P. Mancini, 119–142. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Voltmer, K. 2008. “Comparing Media Systems in new Democracies: East Meets South Meets West.” Central European Journal of Communication 1 (1): 23–40.

- Voltmer, K. 2014. “Making Sense of Press Freedom: A Comparison of Journalists’ Perceptions of Press Freedom in Eastern Europe and East Asia.” In Comparing Communication Across Time and Space, edited by M. J. Canel and K. Voltmer, 157–172. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Waisbord, S. 2020. “Mob Censorship: Online Harassment of US Journalists in Times of Digital Hate and Populism.” Digital Journalism 8 (8): 1030–1046.

- Weaver, D. H. 1977. “The Press and Government Restriction: A Cross-National Study Over Time.” Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands) 23 (3): 152–169.

- Whyatt, J. 2021. “Media Freedom Around the World.” In Global Journalism: Understanding World Media Systems, edited by D. Dimitrova, 41–56. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Yang, JungHwan, Hernando Rojas, Magdalena Wojcieszak, Toril Aalberg, Sharon Coen, James Curran, Kaori Hayashi, et al. 2016. “Why are “Others” so Polarized? Perceived Political Polarization and Media use in 10 Countries.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 21 (5): 349–367.