ABSTRACT

A growing number of studies in journalism research are concerned with the effects of immersive journalism (IJ) on audience perceptions and behaviors. This interest in IJ is logical, because IJ has the potential to become an impactful innovation for the industry. However, we have largely neglected the question of whether audiences want this form of emotional journalism. This study fills this gap and investigates whether people consider IJ worth their while. Using a factorial survey design, we presented a sample of 2000 German citizens with descriptions of an immersive production about protests in Belarus, in which we manipulate the use of inclusive technology (VR vs. AR vs. video), immersive narratives (first person vs. third person), agency (choice of perspective vs. no choice of perspective and control of location vs. no control), and emotionality (positive vs. negative vs. neutral tone). The analyzes reveal that an immersive narrative perspective, control and emotionality do not predict worthwhileness perceptions. However, productions that present people with inclusion and technological agency render this production more worthwhile in the eye of the individual user.

Introduction

Immersive journalism (IJ) is a journalistic innovation that uses new technologies to answer the pressing issue of a fragmented, disengaged audience (de la Peña et al. Citation2010; Jones Citation2017). This has connected IJ closely to the so-called audience turn, which resulted in more investment in technology (Costera Meijer Citation2020) and the emotional turn, which evolves alongside an increasing focus on technological tools in journalism (Lecheler Citation2020). In a sense, IJ is the innovative technological expression of the need to reconnect to the audience, which is central in these developments. IJ uses inclusive technologies, such as Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR), to transport the audience into an—arguably very emotional—experience of the news (Bujić and Hamari Citation2020; de Bruin et al. Citation2020). Initial research posited that this form of journalism would empower the audience, as it allows them to control their own experience (e.g., de la Peña et al. Citation2010). Additionally, by literally putting the audience at the center of a story to let them experience how it feels like to be there, IJ is arguably one of the most audience-focused forms of journalism.

However, the adaptation of IJ by media organizations is a costly endeavor that challenges fundamental journalistic values of objectivity and transparency (Goutier et al. Citation2021). More importantly, the audience has not yet widely adopted IJ (Wang, Gu, and Suh Citation2018; Watson Citation2017), and we simply do not know why. Instead, most studies on IJ seem to either focus on the differential effects journalists hope to evoke by exposure to IJ productions, such as empathy (Archer and Finger Citation2018), or discuss the various ethical dilemmas of IJ (Bujić and Hamari Citation2020). This reminds us of recent findings showing that only a proportion of journalists actually know “what their audience wanted” (Uskali et al. Citation2020, 191). However, the adaptation of “contemporary innovations are ultimately connected to assumptions about what audiences want” (Lecheler Citation2020, 287). The audience are members of the public who consume a news production. Living in a high-choice media environment, the audience is steadily “shopping in the ‘supermarket of news’” (Schrøder Citation2015, 61; Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2017) and thereby deciding (consciously or subconsciously) which news they would want to consume for which specific purpose. The audience is the litmus test for innovative technology, as they need to use and buy this form of journalism, thereby making it economically viable (Ilvonen, Vanhalakka, and Helander Citation2020).

Thus, in this paper, we investigate whether and in what form IJ is considered worthwhile by the audience. Based on current literature on IJ and the audience turn, we test perceptions of IJ in an innovative factorial survey design (Otto and Glogger Citation2020).

Immersive Journalism—It’s all About the Audience

IJ is conceptualized as a form of journalism that uses immersive storylines and immersive technology to convey an emotionally compelling, all-encompassing experience of the news (Bujić and Hamari Citation2020; de Bruin et al. Citation2020). With its immersive capabilities, journalists started to use IJ to create more emotional and engaging news stories (Goutier et al. Citation2021). IJ evolved along with an increasing focus of journalism on emotions to connect with the audience (Beckett and Deuze Citation2016; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020) and the growing understanding of the importance of the audience to journalism (Costera Meijer Citation2020; Nelson Citation2021). By letting the audience experience a news story as if they were there, take control over their own experience, and limit their distractions from the outside world by using inclusive technologies, IJ was seen as a way to re-engage a potentially disengaged audience.

IJ is defined by three characteristics: inclusive technologies, immersive narratives, and agency possibilities. Inclusive technologies shut out physical reality and transport the viewers into a different reality (de Bruin et al. Citation2020). These technologies are set on a spectrum of inclusion, the “virtuality continuum” (Milgram and Kishino Citation1994). Several immersive technologies can be ranked on a spectrum, from least inclusive (AR) to most inclusive (VR), depending on the extent to which the physical reality is replaced or overlayed with additional information. Immersive narratives are storylines designed to immerse the audience into a story and make them feel as if they were there. Examples are the first-person narrative in contrast to a third-person narrative or providing the audience with an active role in the storyline (de Bruin et al. Citation2020; Gröppel-Wegener and Kidd Citation2019). Agency possibilities are defined as “the extent to which the user can interact and change the environment in a story” (de Bruin et al. Citation2020, 5; Mabrook Citation2021). They can be divided into narrative agency and technological agency. Technological agency refers to instances where the audience can interact with technology. For IJ, this could mean the ability to “look around”, and the change of location during a story. Narrative agency means that the user can interact and change the storyline, e.g., by making decisions about the storyline (de Bruin et al. Citation2020).

Additionally, IJ is an emotional form of journalism (Gynnild et al. Citation2020; Mabrook Citation2021). IJ is often used to convey a feeling of a place (Dowling Citation2020, 99) or enhance empathy with distant others (Schutte and Silinovic 2017). Therefore, IJ often covers emotional storylines and topics (Mabrook and Singer Citation2019).

As we define it here, IJ was developed within two bigger trends in the journalism industry and research: the audience turn (Costera Meijer Citation2020) and the emotional turn of journalism (Beckett and Deuze Citation2016; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020). Both developments share the goal of wanting to connect to the audience (Beckett and Deuze Citation2016, 2; Lecheler Citation2020; Mabrook Citation2021, 220; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020, 186) who steadily turn their back towards the news (Strömbäck, Djerf-Pierre, and Shehata Citation2013). Economically, the audience focus came with the understanding by journalists that their individual, organizational and institutional success relies on the audience tuning in, reading texts, or watching their videos (Christin and Petre Citation2020). Normatively, this development came with the importance of journalism to “inform citizens”. Hence, it became crucial to reach the audience with relevant content; and the newly implemented measures in the form of metrics indicated higher engagement with less traditional formats of the news; which ultimately led to an increasing focus on innovative practices in journalism, such as IJ (Costera Meijer Citation2020; Van Damme et al. Citation2019). As a result, news agencies increasingly invest in technological equipment (Costera Meijer Citation2020). With the audience turn, also the understanding of the audience shifted. Now, in addition to the conceptualization of the audience being rationally engaged citizens (Dahlberg Citation2011), who are selecting news from a high-choice “supermarket of news” that best satisfy their needs (Schrøder Citation2015, 17), the audience turn and the increasing digitalization also means that the audience is thought to be empowered through digital tools to participate in the production of news (Peters and Witschge Citation2015, p. 24). Thus, no longer is the audience seen as passive recipients of news, but more so as (more or less) active users of the news (Costera Meijer Citation2020; Rosen Citation2006).

IJ is set within this move towards innovation in journalism, which aims at connecting to the audience. It was seen as an answer to draw in a younger audience (Jones Citation2017) and improve the overall brand image (Watson Citation2017).

From the start, IJ has been expected to affect the audience strongly. The main reason for this is that the audience is ideally transported to a scene and feels as if they were there (de la Peña et al. Citation2010), also labeled presence. Indeed, immersive technology has been shown to positively influence presence in contrast to other media formats (see Cummings and Bailenson Citation2016). Additionally, presence has been found to mediate effects on enjoyment and subject involvement (Van Damme et al. Citation2019) and news credibility of IJ (Kang et al. Citation2019; Vettehen et al. Citation2019). Beyond presence, studies have focused e.g., on the level of inclusion, which has been found to increase the sense of presence (Cummings and Bailenson Citation2016), empathy (Bujić et al. Citation2020; Schutte and Stilinović Citation2017) credibility (Kang et al. Citation2019) and trustworthiness (Sundar, Kang, and Oprean Citation2017). However, it is shown that inclusion negatively affects memory and recognition of facts (Sundar, Kang, and Oprean Citation2017; Vettehen et al. Citation2019). Immersive narratives increase presence (Steed et al. Citation2018) and the intention to follow up on a story (Slater et al. Citation2018).

Data gathered from journalism practice, is less encouraging. For example, The New York Times, The Guardian, Euronews, Al Jazeera, and Süddeutsche Zeitung, have previously experimented with 360-degree and VR videos. Euronews, to name one, has published over 100 360-degree videos, many of them including interactive possibilities (Euronews Citation2021). However, after the initial phase of experimentation, the production of IJ has declined and is far from a mainstream adoption (Watson Citation2017). For instance, the 360-degree app of the New York Times went inactive in 2019 (Palmer Citation2020). The production of IJ, despite the technological advancements, remains effortful and expensive (Harris and Taylor Citation2021). However, one potential driver for the declining production of IJ is a lack of adaptation by the audience. As Ilvonen, Vanhalakka, and Helander (Citation2020) state, the audience is the litmus test for any innovation: whether they buy, use, and like a new journalistic product could make or break an innovation. The case of the New York Times shows that using IJ did not increase engagement or translate into subscriptions to the New York Times (Wang, Gu, and Suh Citation2018). While initially, the big hope for IJ was the re-engagement of a disengaged audience, this seems only rarely to be the case.

What is more, paradoxically, while IJ has developed within the audience turn of journalism and has the audience's experience at its heart, little is known about whether the audience wants this form of journalism. This seems to be a common issue in journalistic innovation, as assumptions by journalists about what the audience wants diverge from the expressed audience wishes (e.g., Schmidt, Nelson, and Lawrence Citation2020). One potential reason for this discrepancy is that the audience focus in journalism is often metrics-driven (Costera Meijer Citation2020). For instance, audience behaviors on online news sites are closely monitored (Blanchett Neheli Citation2018). However, metrics do not reflect the audience's wishes but rather their online behavior, which might have different reasons at heart (Nelson and Tandoc Citation2019).

IJ faces a similar problem: Emotional IJ was often used under the assumption that it will attract and engage audiences (Ferrer-Conill et al. Citation2020; Lecheler Citation2020; Sánchez Laws Citation2019). While journalists using IJ think they know what their audience wants, only a proportion of journalists get the answers correctly when asked about them (Uskali et al. Citation2020). Similarly, professionals seem to be excited about the potential of IJ, while the audience seems more skeptical (Nielsen and Sheets Citation2019). Whereas metrics show that the audience spends less time with 360-degree videos than regular videos (Wang, Gu, and Suh Citation2018), we do not know whether this is an issue of the concept of IJ as a whole or rather specific characteristics of IJ. In short: we do not know whether, in which form, and for whom IJ is valuable. And while media use in everyday life is primarily habitual, before this habituality, the use of a particular medium “must logically have undergone a process of relatively rational calculation” (Schrøder and Kobbernagel Citation2010, 118). Hence, only if the audience values a form of journalism, it will be taken on in their active media repertoire. Additionally, it is important to understand the value of IJ to the audience and why they would use it, as only a clear value creation that goes beyond the analysis of effects and behavior, will translate into an economically viable use of IJ (Ilvonen, Vanhalakka, and Helander Citation2020). Consequently, we need to understand how the audience evaluates IJ and go beyond the application of metrics when doing so.

Is Immersive Journalism Worthwhile?

Yet, very little is known about audience perceptions of IJ products. On the one hand, the audience seems to pick up on the intended effects of VR, such as immersion, transportation, emotion, empathy, information, and control. On the other hand, audiences feel that VR journalism is too emotional (Nielsen and Sheets Citation2019), can invade their social space, and result in a fear of missing out (Jones Citation2017). In particular, non-experts are skeptical about using these technologies (Nielsen and Sheets Citation2019). Moreover, at least parts of the audience might not appreciate intense emotional involvement (Newman et al. Citation2019). Ultimately, citizens debate, decide, and might not choose to expose themselves to news that might negatively affect their emotional and mental well-being (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2017).

IJ is assumed to re-engage a disengaged audience (Jones Citation2017)—and it can only do so if the audience sees value in this type of journalism and buys or uses them (Ilvonen, Vanhalakka, and Helander Citation2020). Only IJ's use and adoption can make this form of journalism economically viable. As previously mentioned, the audience first evaluates a product before making it part of their media routine, (Schrøder and Kobbernagel Citation2010, 118), thereby deciding whether a product is worth their while.

Worthwhileness has actually been studied before in a different context: Schrøder (Schrøder Citation2015; Schrøder and Kobbernagel Citation2010; Schrøder and Larsen Citation2010), based on qualitative studies, has come up with it as a user-oriented theoretical construct to describe whether users think a journalistic product is worth their while. Derived from cross-media studies, the concept of worthwhileness is used to investigate, how and why users chose news media from the everyday “supermarket of news”, and how these uses shift over time. It does so by taking into account situational functions and the subjective experience (Schrøder and Larsen Citation2010). By focusing on the factors that underly a routinized media use, it becomes a valuable tool in gauging innovation.

So, what do we expect when it comes to worthwhileness of IJ? Based on the assumption of practitioners that the audience is attracted by innovative technologies (Ferrer-Conill et al. Citation2020) and what we know from research discussed below, we could generally expect the immersive characteristics to affect the evaluation of worthwhileness positively. The different dimensions of IJ support such a hypothesis.

First, concerning the level of inclusion, studies find that more inclusive stimuli are more enjoyable to the audience (Archer and Finger Citation2018; Van Damme et al. Citation2019; Vettehen et al. Citation2019) and lead to more continuance intention (Shin and Biocca Citation2018). Additionally, the younger audience expresses the wish to know a situation from the news, experience how it feels to be in a situation (Costera Meijer Citation2008). Similarly, more inclusive stimuli increase enjoyment during an immersive experience (Van Damme et al. Citation2019). Contrarily, inclusion negatively affects engagement in the context of the New York Times (Wang, Gu, and Suh Citation2018), while Suh et al. (Citation2018) found engagement with inclusive videos to be directly related to quality of the technology used.

Second, studies on the effects of the first-person perspective show that eye contact and a first-person narrative perspective generally increase the sense of plausibility and presence (Bergström, Kilteni, and Slater Citation2016), and ultimately the evaluation of realism (Steed et al. Citation2018). Direct eye contact in an immersive experience led to one-quarter of study participants following up online about the story's content—a high conversion rate in contrast to regular videos (Steed et al. Citation2018).

Agency refers to having choices and control over the subjective focus of the story. This is assumed to positively affect the assessment of usefulness thereof (Sundar et al. Citation2015a), e.g., for websites (Noort, Voorveld, and Reijmersdal Citation2012; Sundar et al. Citation2015b; Xu and Sundar Citation2014). Additionally, interactivity increases engagement because the users perceive the interface to be responsive to their actions, which, in turn, influences the attitudes towards a website and enhances message elaboration (Oh and Sundar Citation2015). Schrøder (Citation2015) states that simply the possibility to participate in the spreading, production, and meaning-making processes of the news can make a medium worthwhile. Additionally, agency possibilities have enhanced enjoyment of an experience (see Settgast et al. Citation2016).

Lastly, IJ is associated with an emotionally engaging form of journalism (de la Peña et al. Citation2010; Gynnild et al. Citation2020) as it has evolved in accordance with the emotional turn of journalism studies (Beckett and Deuze Citation2016). In light of this connection, Lecheler (Citation2020) states, “[t]his type of innovation is about what audiences (allegedly) need and want, so the audience needs to tell us what to make of these innovations” (289). Studies indeed suggest more potent emotionality also to influence audience evaluations. For instance, negative news is assessed as being more informative (Peeters and Czapinski Citation1990), are more likely to be perceived as true (Hilbig Citation2009), are found to trigger a stronger physiological response (Soroka, Fournier, and Nir Citation2019), and ultimately drive engagement with news (Jang and Oh Citation2016). On the other hand, news avoidance has partially been explained by the intense negativity and emotionalization of the news (Newman et al. Citation2019). Thus, we expect:

H1: Immersive characteristics have a positive effect on worthwhileness perceptions in that journalistic productions that offer a) inclusion; b) first-person perspectives; c) technological agency; d) narrative agency; and e) heightened emotionality are seen are more worthwhile.

Next, we argue that worthwhileness perceptions depend on individual-level differences within the audience and most importantly familiarity with IJ products. Previous research shows that participants who are not familiar with VR take longer to explore a scene and have a smaller exploration range than participants with prior VR experience (Jun et al. Citation2020). Non-experienced audiences also struggle with complex forms of interactivity in VR experiences (UK Audience report Citation2021). On the flipside, familiarity with immersive technologies positively influences the acceptance of these technologies (UK audience report Citation2021), and familiarity predicts therapists’ intention to use VR in a clinical setting (Lindner et al. Citation2019). Contrastingly, however, the newness of immersive products often triggers a so-called “novelty effect”, which means that people are more interested in new technologies precisely due to their novelty (Talukdar and Yu Citation2021). While there is thus a case to be made for interest in innovation, there is reason to expect that adaptation is aided by familiarity. We thus hypothesize:

H2: The impact of the immersive characteristics on the evaluation of worthwhileness is moderated by familiarity with immersive products in that the effects described in H1 are stronger for people who are more familiar with immersive products.

Method

To examine how the audience evaluates the worthwhileness of IJ, we conducted a factorial survey. We present participants in an experimental setup with different descriptions of immersive productions, which vary along IJ's defining factors (level of inclusion, immersive narratives, technological and narrative agency possibilities, emotionality), after which we ask for their evaluation. Participants each evaluate three vignettes in total (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010; Auspurg and Hinz Citation2015, 4–9). Using this approach in contrast to a more qualitative approach to investigate audience evaluations or a more traditional experimental study testing the impact of IJ productions (1) allows for the analysis of a judgment process based on a combination of IJ characteristics rather than a single case study, (2) includes structural, situational and individual influences on subjective choices, and (3) is resource-friendly (Otto and Glogger Citation2020).

Vignette Design

We developed a description of a journalistic piece about the protests in Belarus in the summer of 2020 against the re-election of Lukashenko as president in five scenes: (1) an introduction (2) a description of the technology (3) a description of protestors chanting (4) a description of protestors being arrested, (5) explanation of the soldier's perspective. In each of those scenes, we manipulated the factors of IJ with textual and visual stimuli, resulting in a 3 (VR vs. AR vs. video) × 2 (first-person vs. third-person perspective) × 2 (control over location vs. no control location) × 2 (control over storyline vs. no control over storyline) × 3 (negative vs. positive vs. neutral) experimental setup with 72 possible combinations of factors.

We described the level of inclusion (VR vs. AR vs. video) by explaining the technology used in the production and including a picture visualizing the technology. To manipulate narrative perspective (first vs. third-person perspective), a scene in which a woman addressed either the audience or a fellow protestor was described. Technological agency (control over location vs. no control over location) was manipulated by describing a scene where participants could either choose different locations to witness a scene, or the scenes were described from different locations. To manipulate narrative agency (control vs. no control over storyline), the possibility to choose the storyline of either protestors or the military was described, while in the no-control condition participants were simply shown the perspective of the military. Lastly, to manipulate emotionality, the headline and conclusions either portrayed a negative, positive or neutral outlook on the issues; positively, negatively or neutrally connotated wordings were used. Lastly, a picture that was evaluated in the pretests as either being positive, negative or neutral was added.

To ensure that the audience understands the descriptions of IJ, the vignettes were thoroughly pre-tested with two pretests in February and March 2021. The detailed results of the pre-tests can be found in Appendix B, and overall show that participants understand the manipulated factors of the descriptions. An example of one vignette can be found in Appendix A.

Measures

The seven dimensions of worthwhileness (Schrøder Citation2015; Schrøder and Kobbernagel Citation2010), i.e., time spent, public connection, normative pressures, participatory potential, price, technological appeal, and situational fit, are measured with separate indicators (see Table 2 in Appendix A). These indicators form a scale measuring worthwhileness (M = 4.19, SD = 1.43), with a Cronbach's Alpha of .93.

Familiarity with immersive products was measured by asking participants to indicate in a multiple-choice question whether they knew VR journalism, 360° video journalism, AR journalism, VR apart from journalism, AR apart from journalism, other 360° videos. The measure (M = 1.27, SD = 1.08) has a scale reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of .63.

All analyzes control for news use (i.e., media consumption per day/week M = 5.54, SD = 1.82), age, gender, and education. To ensure data quality, we included one knowledge question (i.e., attention check): participants were asked to indicate what the demonstrations described in the text protested against, and 68.45% of the participants answered this question correctly.

Lastly, based on the original conceptualization of IJ, an immersiveness index (indicating the level of immersiveness of the experimental stimuli) was calculated. To do so, each vignette was given a score that adds up the number of immersive factors (AR, VR, first-person, technological agency, narrative agency, positive and negative emotionality). Thus, this index ranks the journalistic products on a scale from 0 - least immersive (video, third-person perspective, no technological and narrative agency, neutral emotionality) to 5—most immersive (VR/AR, first-person perspective, technological and narrative agency, negative/positive emotionality).

Analysis Strategy

An a-priori power analysis was conducted. A total sample size of 1464 participant was calculated, showing three vignettes per participant, assuming a small effect size (.01), a desired power of .8, and a desired significance level of .01. To account for data cleaning and missing values, we collected a total sample of 2000 participants. In data cleaning, participants were excluded when they met two criteria: when they belong to the bottom or top 5% concerning the duration and when they failed the attention check. Through this procedure, a total of 1889 participants were included in the analysis, resulting in a total number of 5667 observations and an average of 78.7 evaluations per vignette.

In the experimental setup, each participant was randomly assigned to one block, including three vignettes, which randomly varied in order for each participant. As a result, the observations are (1) nested on the level of participants and (2) nested on the level of block assignment. To account for this nested data structure, a multi-level model applying restricted maximum likelihood estimation was conducted.

To ensure the most efficient setup that was simultaneously not too fatiguing for participants, a blocking strategy maximizing the D-efficiency was calculated (Auspurg and Hinz Citation2015). The optimal block design was calculated by utilizing the SAS macro %Mktex, which created a blocking design for the 3 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 factorial design with 24 blocks consisting of 3 vignettes per person (D-efficiency = 100). The data confirms the successful blocking. An analysis of the intra-class correlation (ICC), indicating the proportion of the variance explained by the blocking strategy (Hox, Moerbeek, and van de Schoot Citation2010, 6), shows that only 0.07% of the variance in worthwhileness is explained by the block assignment. Therefore, we exclude the clustering on the block-level in the remainder of this paper; however, we added clustering on participants’ level.Footnote1

Data collection was conducted from mid-April till mid-May 2021 in Germany with 18-to-45-year-old participants by the market research company Dynata. Of the final sample, 53.4% is female, and the mean age is 33.52 years (SD = 7.2). ANOVA analyzes show that there are no significant differences between the stimulus groups concerning age (F (71, 5595) = 0.575, p = 0.998), education (F (71, 5595) = 0.936, p = 0.63) and familiarity (F (71, 5595) = .717, p = 0.965), as expected due to randomization. However, a Chi-square test shows significant differences between groups when it comes to the distribution of gender (χ2 = 96.133, df = 71, p = 0.025).

Results

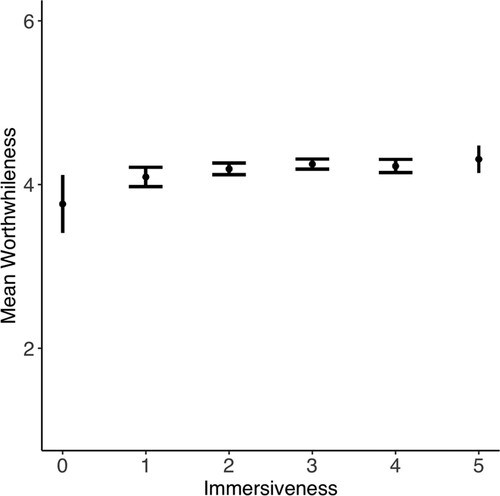

By looking at the mean of worthwhileness per vignette, we can identify which vignettes were evaluated as most and least worthwhile. The vignette evaluated as least worthwhile (M = 3.78, SD = 1.48) described the situation in Belarus in the form of a video, from a third-person narrative perspective, without technological nor narrative agency with a negative evaluation, thus with very little immersive characteristics. The vignette evaluated as most worthwhile (M = 4.53, SD = 1.53) describes the story in the form of a VR video, first-person narrative perspective, including technological and narrative agency, and neutral emotionality, so including many immersive components. This anecdotal evidence hints at immersiveness being positively related to worthwhileness. This trend is further demonstrated by . Overall, the more immersive descriptions the texts included, the higher the mean of worthwhileness.

Figure 1. The mean of worthwhileness per level of immersiveness of the stimuli descriptions, with 95% CIs.

A step-by-step approach to building multi-level models is taken to test our hypotheses. Model 1 of , the baseline model including only the DV, calculates the intraclass correlation (ICC), which shows the proportion of the variance explained by the highest level (i.e., participants) (Hox, Moerbeek, and van de Schoot Citation2010, 6). The results show that 8.1% of the variance in worthwhileness can be explained by the variation on the individual level. This indicates that most of the variation in worthwhileness depends on the level of the separate vignettes.

Table 1. MLM models 1 through 4. ML models to build the MLM models predicting worthwhileness (0 not worthwhile—7 very worthwhile). Model 3 tests main effects of the factors on worthwhileness specified in H1a/b/c/d/e, model 4 tests the moderation of familiarity as specified in RQ1. Factors are dummy-coded (0—non-immersive, 1—immersive).

In models 2 and 3 of , we estimate the influence of the different factors of IJ on the evaluation of worthwhileness. Model 2 does not include control variables; model 3 controls for the individual-level variables gender, education, age, news use, and familiarity with the technology. More specifically, the models show to what extent the level of inclusion (the extent that physical reality is shut out by technology in the form of the VR or AR video), the narrative perspective (first-person storyline), the technological and narrative agency (control over the location or the storyline, respectively), and the level of emotionality of the text (strongly positive or negative descriptions), influence the evaluation of worthwhileness. The results support two out of five sub-hypotheses concerning the effect of immersiveness on worthwhileness. More specifically, H1a expecting a higher level of inclusion leading to a higher evaluation of worthwhileness can be partially verified. Here, the assumption was that the more a technology is described as shutting out and recreating reality, the more worthwhile it is considered by the audience. This hypothesis can be partially supported: the VR condition was evaluated as significantly more worthwhile than the video condition (model 3: b = 0.133, se = 0.020, p < 0.01), although AR was not evaluated as more worthwhile than video (model 3: b = 0.035, se = 0.020, p > 0.05,). Additionally, the effect of VR compared to AR is positive and significant (model 3: b = 0.097; se = 0.020; p < 0.01, not shown in table). Furthermore, hypothesis H1c, assuming a positive influence of technological agency on the evaluation of worthwhileness is supported (model 3: b = 0.058, se = 0.017, p < 0.01). Thus, the audience evaluates it as more worthwhile to choose between different locations from which a scene can be watched, in contrast to simply seeing the different scenes without having the choice, regardless of other immersive characteristics.

In contrast to our expectation, the narrative perspective in the form of a first-person perspective (model 3: b = 0.028, se = 0.017, p > 0.05) did not significantly influence the evaluation of worthwhileness. H1b, thus, is rejected. Narrative agency in form of being able to choose between seeing the protests from the perspectives of two different participants (soldier vs. protestor) did not significantly influence the evaluation of worthwhileness (model 3: b = 0.022; se = 0.017, p > 0.05). Therefore, H1d is rejected. Lastly, the different levels of emotionality of the production did not influence the evaluation of worthwhileness (negative: b = 0.021 se = 0.020, p > 0.05; positive: b = 0.019, se = 0.020, p > 0.05, see model 3). Thus, H1e is rejected.Footnote2 Overall, this means that participants evaluated those descriptions that include VR, as well as those including the ability to choose to see a scene from different perspectives as more worthwhile than those described with their non-immersive characteristics (AR and video; not choosing scenes). However, all other IJ characteristics are not evaluated to be worthwhile by the audience.

To investigate the moderating effect of familiarity with immersive products on the evaluation of worthwhileness, the cross-level interaction of familiarity was included in the model. As a first step to build this model, it was tested whether there is random variation in the slopes of the effects of the immersive characteristics to justify a random effect model. To this end, the model fit with and without the random slopes was compared. Results show that the model fit improved strongly when including the random slopes for VR (AIC = 15,388, Chisq = 9.927, p = 0.007, see Appendix C, Table 3). Therefore, random slopes for VR were included in the model. However, including the random slopes for all other immersive factors did not improve the model fit according to AIC estimators (see Appendix C, Table 3). Following the suggestion of Heisig and Schaeffer (Citation2019), the cross-level interactions of these predictors without specified random slopes were not included in the analyzes.Footnote3 Model 4 in presents the results of the cross-level interaction effect to test whether familiarity moderates the impact of VR on the evaluation of worthwhileness.

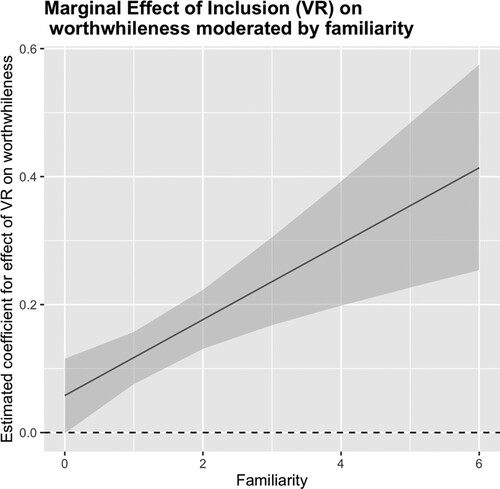

H2 predicts that high familiarity with immersive products leads to a stronger effect of immersiveness on the evaluation of worthwhileness and is supported for VR. As shown in model 4 in and in , familiarity with immersive products significantly moderates the influence of VR on the evaluation of worthwhileness (model 4: b = 0.059, se = 0.016, p < 0.001). In other words, the more familiar participants are with immersive products, the stronger is the positive effect of VR on the evaluation of worthwhileness.

Figure 2. Marginal Effects Plot—Differential effects of inclusiveness (VR vs. video) on worthwhileness evaluations for different levels of familiarity with immersive products.

Lastly, to further ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted an additional analysis predicting a related variable to worthwhileness, namely continuance intention, by asking participants “I would further consume news as they were described in the article”. Results can be read from Table 10 in Appendix C, and are overall in line with the results of the analysis presented in in form of direction and significance.

Conclusion

IJ has been termed a potential empathy machine (Milk Citation2015), seen as a way to engage the audience emotionally (de la Peña et al. Citation2010) and without distractions (Sánchez Laws Citation2019, 2), let the audience experience how it feels to be at a news event, and ultimately to “understand the world in new ways” (Watson Citation2017, 7). Despite these positive connotations, the audience did not take up IJ (Wang, Gu, and Suh Citation2018) and the production of IJ has been declining since the tech industry largely stopped funding IJ projects (Sirkkunen et al. Citation2020, 23). In light of this, we wanted to understand whether and in which form the audience values IJ. Our results show that the audience evaluates both the level of inclusion in the form of VR and technological agency positively. However, inclusion in the form of AR, first-person narrative perspective, narrative agency, and different emotionality levels did not significantly differ from the evaluation of worthwhileness to their respective counterparts. Additionally, respondents who were more familiar with immersive productions also evaluated the worthwhileness of the VR condition better. Overall, these findings have three implications.

Firstly, our results indicate that the technical characteristics of IJ, such as the level of inclusion and technological agency, are considered to be worthwhile by the audience. The level of inclusion, in combination with basic agency possibilities, is a central piece in most definitions of IJ (e.g., de Bruin et al. Citation2020). Subsequently, many studies focus on the effects of inclusion (e.g., Kang et al. Citation2019; Sundar, Kang, and Oprean Citation2017; Vettehen et al. Citation2019) or agency possibilities (e.g., Schutte and Stilinović Citation2017; Wu et al. Citation2021). However, it remained unclear whether the audience evaluates these crucial aspects as worthwhile. Our results show, the scholarly focus on inclusion and technological agency is justified from the audience's perspective. Additionally, more familiarity with immersive experiences positively moderates the effect of VR on the evaluation of worthwhileness. This finding is good news for IJ: With an increase of familiarity with the technologies of IJ in the future, audience evaluation and audience adoption of IJ could increase.

Secondly, these results add to a crucial debate within IJ: the question of narrative form. In light of the inherent agency possibilities for the audience of IJ, journalists have been grappling with their degree of authorship (Mabrook Citation2021). When the audience has choices in a news story, such as choosing storylines, journalists need to give up some control over how a news story is conveyed to the audience. Our results indicate that at least narrative conventions of journalism, such as journalistic authorship and a viewer perspective in the news, remain stable. These findings are in line with studies on participatory journalism, which indicate that the audience seems to be less interested in the meaning-making process of journalism than often assumed (Nelson and Tandoc Citation2019; Schmidt, Nelson, and Lawrence Citation2020), and with findings that the audience still expects journalists to contextualize and interpret the ongoings in the world for them (van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014).

Thirdly, the emotionality in the description of the journalistic product did not influence its worthwhileness evaluation. Concerning negative emotions, this makes sense, as the audience assesses news as depressing (Bendau et al. Citation2020) and states negativity as one of the reasons they actively avoid the news (Newman et al. Citation2019). Constructive journalism evolved as a countermeasure to the negativity bias in journalism. Taking on a more future-oriented and positively connoted approach to presenting the news was expected to be valued by the audience (McIntyre and Gyldensted Citation2017). While this study only focused on the emotionality of a story, results indicate that the positive tonality is not evaluated as more worthwhile by the audience. Nonetheless, the audience might decide to put their mental well-being first and not engage with more negatively connoted news, such as hard news (Boukes and Vliegenthart Citation2017). Future studies should investigate the worthwhileness of emotions in the context of innovative technologies, in combination with a focus on audience's well-being.

This study comes with limitations. While the method of factorial surveys provides clear advantages, such as increasing the complexity and interactions of phenomena, therefore moving on from a simplistic evaluation to a much more nuanced approach (Auspurg and Hinz Citation2015), it also comes with challenges, most prominently to the external validity. One could question to what extent participants are able to evaluate IJ based on descriptions rather than the actual product. To address and minimize this shortcoming, three critical steps are taken. Firstly, familiarity with IJ and related technologies is considered a potential moderator. Secondly, the stimulus material underwent a thorough pretesting and adaption phase to ensure the audience comprehends the described concepts as intended and can identify and differentiate the specific characteristics (see Appendix B). Thirdly, great care is taken in the sampling process to achieve a heterogeneous sample of the population in Germany and increase external validity (Atzmüller and Steiner Citation2010). However, we urge for additional testing of the effects of immersiveness, for instance experimentally based on immersive products created by journalists. This would allow for a clearer understanding of the direction and magnitude of these perceptions. To understand what the audience appreciates about IJ, and why and how they would (or would not) use this type of journalism and how this is connected to their personal preferences, focus group discussions or interviews of users of IJ would be fruitful.

Ultimately, this study indicates that while some immersive characteristics of IJ are worthwhile, not all are. Journalists should focus on the most essential elements when producing IJ: producing stories as VR videos, and providing meaningful agency possibilities while maintaining some level of narrative control. An audience-informed approach of producing IJ, together with an increase of familiarity with the technology could create the potential for a sustainable increase of the value and use of IJ.

Ethical Approval

The study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Communication Department at the University of Vienna under 20210308_017.

rjop_a_2177711_sm1567.docx

Download MS Word (2.1 MB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Appendix C Table 11, however, presents the results of the analyzes including fixed effects for the separate blocks, and shows that the findings are robust for block assignment.

2 The effects of individual-level characteristics on worthwhileness are not relevant for testing our expectations, as these direct effects do not take into account the different immersiveness characteristics of the vignettes. However, the results do show that in general, younger, lower educated and male participants, participants that are familiar with the technology, and participants with higher the news consumption, evaluate the worthwhileness of the vignettes higher.

3 Additional robustness checks were conducted to test whether excluding these random slopes affects the findings. Table 8 in Appendix C replicates model 3 of Table 1, but including the random slopes of all predictors. The findings indicate that the varying of the random slopes themselves does not influence the models substantively. Table 9 in Appendix C replicates model 4 of Table 1, but including the random slopes and the cross-level interaction effects. The findings result in two significant cross-level interactions (technological agency # familiarity (b=0.037, se=0.015, p<0.05); emotionality negative # familiarity (b= −0.035, se= 0.016, p<0.05)). Due to the worse model fit (see Table 7, Appendix C), they were not included in the main analysis. The remaining results do not differ from model 4 in form of direction and significance.

References

- Archer, D., and K. Finger. 2018. Walking in Another’s Virtual Shoes: Do 360-degree Video News Stories Generate Empathy in Viewers? Report, Columbia journalism school.

- Atzmüller, C., and P. M. Steiner. 2010. “Experimental Vignette Studies n Survey Research.” Methodology 6 (3): 128–138. doi:10.1027/1614-2241/a000014.

- Auspurg, K., and T. Hinz. 2015. Factorial Survey Experiments. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781483398075.

- Beckett, C., and M. Deuze. 2016. “On the Role of Emotion in the Future of Journalism.” Social Media and Society 2: 3. doi:10.1177/2056305116662395.

- Bendau, A., M. B. Petzold, L. Pyrkosch, L. Mascarell Maricic, F. Betzler, J. Rogoll, J. Große, A. Ströhle, and J. Plag. 2020. “Associations Between COVID-19 Related Media Consumption and Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression and COVID-19 Related Fear in the General Population in Germany.” European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 271 (2): 283–291. doi:10.1007/s00406-020-01171-6.

- Bergström, I., K. Kilteni, and M. Slater. 2016. “First-person Perspective Virtual Body Posture Influences Stress: A Virtual Reality Body Ownership Study.” PLoS ONE 11 (2): Article e0148060. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148060

- Blanchett Neheli, N. 2018. “News by Numbers: The Evolution of Analytics in Journalism.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 1041–1051. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1504626.

- Boukes, M., and R. Vliegenthart. 2017. “News Consumption and its Unpleasant Side Effect: Studying the Effect of Hard and Soft News Exposure on Mental Well-Being Over Time.” Journal of Media Psychology 29 (3): 137–147. doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000224.

- Bujić, M., and J. Hamari. 2020. “Immersive Journalism: Extant Corpus and Future Agenda.” GamiFIN Conference 2020 2020: 136–145.

- Bujić, M., M. Salminen, J. Macey, and J. Hamari. 2020. ““Empathy Machine”: How Virtual Reality Affects Human Rights Attitudes.” Internet Research 30 (5): 1407–1425. doi:10.1108/INTR-07-2019-0306.

- Christin, A., and C. Petre. 2020. “Making Peace with Metrics: RelationalWork in Online News Production.” Sociologica 14: 133–156. doi:10.6092/issn.1971-8853/11178.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2008. “Checking, Snacking and Bodysnatching.” In From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media. RIPE@2007, edited by J. B. G. F. Lowe, 167–186. Diemen: Nordicom.

- Costera Meijer, I. 2020. “Understanding the Audience Turn in Journalism: From Quality Discourse to Innovation Discourse as Anchoring Practices 1995–2020.” Journalism Studies 21 (16): 2326–2342. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1847681.

- Cummings, J. J., and J. N. Bailenson. 2016. “How Immersive Is Enough? A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Immersive Technology on User Presence.” Media Psychology 19 (2): 272–309. doi:10.1080/15213269.2015.1015740.

- Dahlberg, L. 2011. “Re-Constructing Digital Democracy: An Outline of Four ‘Positions.” New Media & Society 13: 6. doi:10.1177/1461444810389569.

- de Bruin, K., Y. de Haan, S. Kruikemeier, S. Lecheler, and N. Goutier. 2020. “A First-Person Promise? A Content-Analysis of Immersive Journalistic Productions.” Journalism, doi:10.1177/1464884920922006.

- de la Peña, N., P. Weil, J. Llobera, E. Giannopoulos, A. Pomés, B. Spanlang, D. Friedman, M. V. Sanchez-Vives, and M. Slater. 2010. “Immersive Journalism: Immersive Virtual Reality for the First-Person Experience of News.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 19 (4): 291–301. doi:10.1162/PRES_a_00005.

- Dowling, D. O. 2020. “Place-based Journalism, Aesthetics, and Branding.” In Immersive Journalism as Storytelling - Ethics, Production and Design, edited by T. Uskali, A. Gynnild, S. Jones, and E. Sirkkunen, 99–112. New York: Routledge.

- Euronews. 2021. 360° video | euronews - internationale Nachrichten zum Thema 360° video. Retrieved May 3, 2021, from https://de.euronews.com/tag/360-video.

- Ferrer-Conill, R., M. Foxman, J. Jones, T. Sihvonen, and M. Siitonen. 2020. “Playful Approaches to News Engagement.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Metdia Technologies 26 (3): 457–469. doi:10.1177/1354856520923964.

- Goutier, N., Y. de Haan, K. de Bruin, S. Lecheler, and S. Kruikemeier. 2021. “From “Cool Observer” to “Emotional Participant”: The Practice of Immersive Journalism.” Journalism Studies 22 (12): 1648–1664. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2021.1956364

- Gröppel-Wegener, A., and J. Kidd. 2019. Critical Encounters with Immersive Storytelling. doi:10.4324/9780429055409

- Gynnild, A., T. Uskali, S. Jones, and E. Sirkkunen. 2020. “Introduction: What is Immersive Journalism?” In Immersive Journalism as Storytelling - Ethics, Production and Design, edited by T. Uskali, A. Gynnild, S. Jones, and E. Sirkkunen, 188–197. New York: Routledge.

- Harris, J., and J. Taylor. 2021. “Narrative in VR Journalism: Research Into Practice.” Media Practice and Education 22 (3): 211–224. doi:10.1080/25741136.2021.1904615.

- Heisig, J. P., and M. Schaeffer. 2019. “Why You Should Always Include a Random Slope for the Lower-Level Variable Involved in a Cross-Level Interaction.” European Sociological Review 35 (2): 2258–2279. doi:10.1093/esr/jcy053.

- Hilbig, B. E. 2009. “Sad, Thus True: Negativity Bias in Judgments of Truth.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45 (4): 983–986. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.012.

- Hox, J. J., M. Moerbeek, and R. van de Schoot. 2010. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Ilvonen, I., J. Vanhalakka, and N. Helander. 2020. “Case Study: Creating a Business Value in Immersive Journalism.” In Immersive Journalism as Storytelling - Ethics, Production and Design, edited by T. Uskali, A. Gynnild, S. Jones, and E. Sirkkunen, 112–122. New York: Routledge.

- Jang, S. M., and Y. W. Oh. 2016. “Getting Attention Online in Election Coverage: Audience Selectivity in the 2012 US Presidential Election.” New Media and Society 18 (10): 2271–2286. doi:10.1177/1461444815583491.

- Jones, S. 2017. “Disrupting the Narrative: Immersive Journalism in Virtual Reality.” Journal of Media Practice 18 (2–3): 171–185. doi:10.1080/14682753.2017.1374677.

- Jun, H., M. R. Miller, F. Herrera, B. Reeves, and J. N. Bailenson. 2020. “Stimulus Sampling with 360-Videos: Examining Head Movements, Arousal, Presence, Simulator Sickness, and Preference on a Large Sample of Participants and Videos.” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 13 (3): 1–1. doi:10.1109/taffc.2020.3004617.

- Kang, S., E. O’Brien, A. Villarreal, W. Lee, and C. Mahood. 2019. “Immersive Journalism and Telepresence: Does Virtual Reality News use Affect News Credibility?” Digital Journalism 7 (2): 294–313. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1504624.

- Lecheler, S. 2020. “The Emotional Turn in Journalism Needs to be About Audience Perceptions.” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 287–291. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1708766.

- Lindner, P., A. Miloff, E. Zetterlund, L. Reuterskiöld, G. Andersson, and P. Carlbring. 2019. “Attitudes Toward and Familiarity With Virtual Reality Therapy Among Practicing Cognitive Behavior Therapists: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study in the Era of Consumer VR Platforms.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 347. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00176.

- Mabrook, R. 2021. “Between Journalist Authorship and User Agency: Exploring the Concept of Objectivity in VR Journalism.” Journalism Studies 22 (2): 209–224. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1813619.

- Mabrook, R., and J. B. Singer. 2019. “Virtual Reality, 360° Video, and Journalism Studies: Conceptual Approaches to Immersive Technologies.” Journalism Studies 20 (14): 2096–2112. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2019.1568203.

- McIntyre, K., and C. Gyldensted. 2017. “Constructive Journalism: Applying Positive Psychology Techniques to News Production.” The Journal of Media Innovations 2 (4): 20–34. doi:10.5617/jomi.v4i2.2403.

- Milgram, P., and F. Kishino. 1994. “A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays.” IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems 12 (12): 1321–1329.

- Milk, C. 2015. Chris Milk: How virtual reality can create the ultimate empathy machine | TED Talk | TED.com. https://www.ted.com/talks/chris_milk_how_virtual_reality_can_create_the_ultimate_empathy_machine/transcript.

- Nelson, J. L. 2021. “The Next Media Regime: The Pursuit of ‘Audience Engagement’ in Journalism.” Journalism 22 (9): 2350–2367. doi:10.1177/1464884919862375.

- Nelson, J. L., and E.C. Tandoc Jr. 2019. “Doing “Well” or Doing “Good”: What Audience Analytics Reveal About Journalism’s Competing Goals.” Journalism Studies 20 (13): 1960–1976. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1547122.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, and R. K. Nielsen. 2019. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2019/.

- Nielsen, S. L., and P. Sheets. 2019. “Virtual Hype Meets Reality: Users’ Perception of Immersive Journalism.” Journalism 22 (10): 2637–2653. doi:10.1177/1464884919869399.

- Noort, G. v., H. A. M. Voorveld, and E. A. Reijmersdal. 2012. “Interactivity in Brand Web Sites: Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Responses Explained by Consumers’ Online Flow Experience.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 26: 223–234. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2011.11.002

- Oh, J., and S. S. Sundar. 2015. “How Does Interactivity Persuade? An Experimental Test of Interactivity on Cognitive Absorption, Elaboration, and Attitudes.” Journal of Communication 65 (2): 213–236. doi:10.1111/jcom.12147

- Otto, L. P., and I. Glogger. 2020. “Expanding the Methodological Toolbox: Factorial Surveys in Journalism Research.” Journalism Studies 21 (7): 947–965. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1745663.

- Palmer, L. 2020. ““Breaking Free” from the Frame: International Human Rights and the New York Times’ 360-Degree Video Journalism.” Digital Journalism 8 (3): 386–403. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1709982.

- Peeters, G., and J. Czapinski. 1990. “Positive-negative Asymmetry in Evaluations: The Distinction Between Affective and Informational Negativity Effects.” European Review of Social Psychology 1 (1): 33–60. doi:10.1080/14792779108401856.

- Peters, C., and T. Witschge. 2015. “From Grand Narratives of Democracy to Small Expectations of Participation.” Journalism Practice 9 (1): 19–34. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.928455.

- Rosen, J. 2006. The People Formerly Known as the Audience. PressThink: Ghost of Democracy in the Media Machine.

- Sánchez Laws, A. L. 2019. Conceptualising Immersive Journalism. London: Routledge.

- Schmidt, T. R., J. L. Nelson, and R. G. Lawrence. 2020. “Conceptualizing the Active Audience: Rhetoric and Practice in “Engaged Journalism”.” Journalism 3–21. doi:10.1177/1464884920934246.

- Schrøder, K. C. 2015. “News Media Old and New: Fluctuating Audiences, News Repertoires and Locations of Consumption.” Journalism Studies 16 (1): 60–78. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.890332.

- Schrøder, K. C., and C. Kobbernagel. 2010. “Towards a Typology of Cross-Media News Consumption: A Qualitativequantitative Synthesis.” Northern Lights: Film and Media Studies Yearbook 8 (1): 115–137. doi:10.1386/nl.8.115_1.

- Schrøder, K. C., and B. S. Larsen. 2010. “The Shifting Cross-Media News Landscape.” Journalism Studies 11 (4): 524–534. doi:10.1080/14616701003638392.

- Schutte, N. S., and E. J. Stilinović. 2017. “Facilitating Empathy Through Virtual Reality.” Motivation and Emotion 41 (6): 708–712. doi:10.1007/s11031-017-9641-7.

- Settgast, V., J. Pirker, S. Lontschar, S. Maggale, and C. Gütl. 2016. “Evaluating Experiences in Different Virtual Reality Setups.” Entertainment Computing-ICEC 2016: 15th IFIP TC 14 International Conference, Vienna, Austria, vol. 15: 115–125. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46100-7_10ï.

- Shin, D., and F. Biocca. 2018. “Exploring Immersive Experience in Journalism.” New Media and Society 20 (8): 2800–2823. doi:10.1177/1461444817733133.

- Sirkkunen, E., J. Vazquez-Herrero, T. Uskali, and H. Väätäjä. 2020. “Exploring the Immersive Jouranlism Landscape.” In Immersive Journalism as Storytelling – Ethics, Production and Design, edited by T. Uskali, S. Gynnild, S. Jones, and E. Sirkkunen, 13–24. New York: Routledge.

- Slater, M., X. Navarro, J. Valenzuela, R. Oliva, A. Beacco, J. Thorn, and Z. Watson. 2018. “Virtually Being Lenin Enhances Presence and Engagement in a Scene from the Russian Revolution.” Frontiers Robotics AI 5 (AUG): 91. doi:10.3389/frobt.2018.00091.

- Soroka, S., P. Fournier, and L. Nir. 2019. “Cross-national Evidence of a Negativity Bias in Psychophysiological Reactions to News.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (38): 18888–18892. doi:10.1073/pnas.1908369116.

- Steed, A., Y. Pan, Z. Watson, and M. Slater. 2018. ““We Wait”-The Impact of Character Responsiveness and Self Embodiment on Presence and Interest in an Immersive News Experience.” Frontiers Robotics AI 5 (OCT): 1–14. doi:10.3389/frobt.2018.00112.

- Strömbäck, J., M. Djerf-Pierre, and A. Shehata. 2013. “The Dynamics of Political Interest and News Media Consumption: A Longitudinal Perspective.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 25 (4): 414–435. doi:10.1093/ijpor/eds018.

- Suh, A., G. Wang, W. Gu, and C. Wagner. 2018. “Enhancing Audience Engagement Through Immersive 360-Degree Videos: An Experimental Study.” In Augmented Cognition: Intelligent Technologies, edited by D. Schmorrow, and C. Fidopiastis. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-91470-1_34

- Sundar, S. S., E. Go, H.-S. Kim, and B. Zhang. 2015b. “Communicating Art, Virtually! Psychological Effects of Technological Affordances in a Virtual Museum.” International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 31 (6): 385–401. doi:10.1080/10447318.2015.1033912.

- Sundar, S. S., H. Jia, T. F. Waddell, and Y. Huang. 2015a. “Toward a Theory of Interactive Media Effects (TIME) - Four Models for Explaining How Interface Features Affect User Psychology.” In The Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology, edited by S. S. Sundar, 47–86.

- Sundar, S. S., J. Kang, and D. Oprean. 2017. “Being There in the Midst of the Story: How Immersive Journalism Affects Our Perceptions and Cognitions.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 20 (11): 672–682. doi:10.1089/cyber.2017.0271.

- Swart, J., S. Peters, and M. Broersma. 2017. “Navigating Cross-Media News use.” Journalism Studies 18 (11): 1343–1362. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2015.1129285.

- Talukdar, N., and S. Yu. 2021. “Breaking the Psychological Distance: The Effect of Immersive Virtual Reality on Perceived Novelty and User Satisfaction.” Journal of Strategic Marketing 1–25. doi:10.1080/0965254X.2021.1967428.

- UK Audience report. 2021. The Immersive Audience Journey. https://audienceofthefuture.live/immersive-audience-journey/.

- Uskali, T., A. Gynnild, E. Sirkkunen, and S. Jones. 2020. “Forecasting Future Trajectories for Immersive Journalism.” In Immersive Journalism as Storytelling - Ethics, Production and Design, edited by T. Uskali, A. Gynnild, S. Jones, and E. Sirkkunen, 188–197. New York.

- Van Damme, K., A. All, L. De Marez, and S. Van Leuven. 2019. “360° Video Journalism: Experimental Study on the Effect of Immersion on News Experience and Distant Suffering.” Journalism Studies 20 (14): 2053–2076. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1561208.

- van der Wurff, R., and K. Schoenbach. 2014. “Civic and Citizen Demands of News Media and Journalists: What Does the Audience Expect from Good Journalism?” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91 (3): 433–451. doi:10.1177/1077699014538974.

- Vettehen, H., D. Wiltink, M. Huiskamp, G. Schaap, and P. Ketelaar. 2019. “Taking the Full View: How Viewers Respond to 360-Degree Video News.” Computers in Human Behavior 91: 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.09.018.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2020. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 175–194. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1697626

- Wang, G., W. Gu, and A. Suh. 2018. “The Effects of 360-Degree VR Videos on Audience Engagement: Evidence from the New York Times.” In International Conference on HCI 21 in Business, Government, and Organizations, edited by F. H. Nah and B. Xiao, 217–235. Springer.

- Watson, Z. 2017. VR for News? The New Reality. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Oxford University.

- Wu, H., T. Cai, D. Luo, Y. Liu, and Z. Zhang. 2021. “Immersive Virtual Reality News: A Study of User Experience and Media Effects.” International Journal of Human Computer Studies 147: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102576.

- Xu, Q., and S. S. Sundar. 2014. “Lights, Camera, Music, Interaction! Interactive Persuasion in e-Commerce.” Communication Research 41 (2): 282–308. doi:10.1177/0093650212439062