ABSTRACT

Coping with misinformation in a media environment is one of the challenges that undermine the role of the media. The pandemic of Covid-19 influenced the media organisations in their working processes significantly and a decrease in accuracy was one of the findings of our study. This paper examines the impact of the pandemic in local media to journalists’ practices and the role of the media. We aimed to research the effects of the pandemic in the local environment on journalistic procedures and the media's role after this period. In answering the research questions, we used the method of a structured questionnaire for journalists and semi-structured in-depth interviews for local News Editors. We aimed to research the media production practices on various levels of professionals included in local news. We detected those production practices that could endanger the credibility of the local media. The findings provided insights into how Slovenian local journalists and editors define, understand, and practice fact-checking. The results led to an understanding that the perception of the media role in offering information was higher during the pandemic period and that human verification is key in ensuring the credibility of content in local newsrooms.

Introduction

In the digitalised media production environment, where an acceleration of the journalistic production process is necessary and is under the constant pressure of delivering new content, concerns about the information provided have become increasingly prevalent (Diekerhof Citation2021; Van Leuven et al. Citation2018). Coping with mis/disinformation fact-checking, source-checking, verification, and debunking have long been journalistic practices; however, when faced with the firehose of user-generated content online, these seem to fall by the wayside more than they should (Thomson et al. Citation2022). Not only had a switch been made among audiences but they were increasingly consuming the news from social media on a global scaleFootnote1 but there has also been a turn to those platforms in the daily journalistic routine of gathering information, as they have become increasingly used as information sources by established media outlets (Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017).

Since the concerning amount of incorrect or manipulated content in social media has been observed as a growing problem (e.g., Krause et al. Citation2020; Schapals Citation2018; Jahng, Eckert, and Metzger-Riftkin Citation2021), a response to this online information challenge has produced a number of fact-checking, such as FactChek.org (http://www.factcheck.org), Snopes (http://snopes.com) or Fact Checker (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/) and verification services, such as TinEye (https://tineye.com/) or Google reverse Image Search (https://google.com) which can help to identify and correct false or inaccurate content or claims in the public domain made online or through other channels (Brandtzaeg, Følstad, and Domínguez Citation2018). In his research of journalists’ role perception in the era of fake news Schapals (Citation2018) expressed significant concern about the media's role as an essential pillar of democracy, but, on the other hand, readers have made a concerted effort to seek reliable and trustworthy information online, which, once again, highlights the democratic function of journalism in society (Schapals Citation2018). Accordingly, the rapid spread of fake news is also seen as an indicator of a crisis in journalism and the media. On the other hand, the audience perceive it as an attack that could undermine the credibility of professional journalism (Nielsen and Graves Citation2017). Therefore, the rapid spread of fake news is also seen as an indicator of a crisis in journalism and the media and spread of fake news could be perceived as an attack that could undermine the credibility of professional journalism (Nielsen and Graves Citation2017).

Credible media are of vital importance to society, as the leading role of the media in a democracy is to provide its citizens with the relevant information they need (Calvo-Porral, Martínez-Fernández, and Juanatey-Boga Citation2014). Countries with advanced and developing economies are concerned with the effects of mis/disinformation on democratic institutions, political discourse, trust, and social harmony (Levush Citation2019). In the media landscape, the role of local news is more than necessary, as it is much more than a commodity, it is an essential component of democracy and is even perceived as a public good (Ali Citation2016). During the pandemic, the role of local media was expressed through informing local audiences about relevant information for citizens everyday life (Wenzel and Crittenden Citation2023; Shearer Citation2020; Perreault and Perreault Citation2021).

The studies done during the Covid-19 pandemic period show that those searching for credible news sources turned to traditional media. Namely, trust in print, radio and television increased and in the category of new media (news web pages and social media), remained at the lowest levels of trust (EBU Citation2021; Newman et al. Citation2021). The growth of trust in the news of established media brands could relate to the role media has in the period of the pandemic crisis, where the significance of effective communication strategies for informing the public about the main issues in society, namely infectious diseases, is of vital importance. In times of pandemic, journalists use formal, professional, informal, and personal means to contribute to the Covid-19 communication ecology, and it is their responsibility to be the fact-checkers and relay information to the public (Perreault and Perreault Citation2021).

This paper focuses on the journalistic practices used by journalists and editors of local media in Slovenia. Slovenia was the first country to end the first wave of the epidemic due to successful epidemic indicators, even though Italy, a neighbouring country, was the European disease hotspot. The last study among young media audience in Slovenia (Žilič and Držanič Citation2021) showed that they appreciate reliable information, but they showed discontent with the information landscape of Slovene media. A crisis of trust in journalism, rapid news production and dissemination have led to an era where fact-checking in newsrooms could help protect the credibility of information due to the time pressure in media production. As local media in Slovenia are going through different challenges in terms of ownership and cost-cutting requirements, we planned to discover how all these changes influenced the production processes in the informative role of local media. To establish a clear picture of journalists' changing practices, the present article explores the challenges in media production practices focusing on information-gathering, sourcing, fact-checking and verification procedures as a part of changed working conditions during the Covid-19 pandemic on local media of various backgrounds (commercial, public service and community-owned) and types (radio, television, print, and online) in Slovenia. Focusing on the journalistic roles is key to this study as news is defined as content that is expected to be independent, reliable, accurate and comprehensive, whilst journalism is expected to report the truth (Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2007). Studies of this role (Perreault and Perreault Citation2021) showed that journalists described having a personal responsibility to connect people regarding the resources they needed to stay healthy.

In our research, we gained data about the perception of journalistic production practices and fact-checking procedures in local media from the Editors’ perspective. Additionally, we gained data about, fake news' occurrences, changing workflow in newsrooms, emphasising news source practices, working conditions and journalistic approaches to local news gathering and news production in Slovenia during pandemics. Since existing studies did not focus on the media production approaches and minimisation of misinformation in local media, the present study tries to fill this research gap. Moreover, this paper attempts to fill the research gap in understanding the journalistic production procedures in local media during the pandemic in Slovenia. Our study also aimed to examine among the journalists and editors the effects of the pandemic on their perception of the role of the media within the local environment during and after this period.

We wanted to understand the pandemic's implications for the local media's fact-checking role. From the perspective of minimizing misinformation spread, we checked the processes, and our findings presented the procedures and responsibilities in newsrooms where journalists play an essential role in fact-checking. In the research, we checked the most used sources in local media and how procedures changed during the pandemic. The analysis will contribute to understanding the content production practices relevant to local media in different surroundings.

Literature Review

Production Practices in Journalism

Media production practices have undergone an intense structural and technological transformation recently. We cannot separate journalism from its technologies and deny the relationship between innovation and journalism (Vobič Citation2011), as journalism has always been based on the technology that enables creativity and the potential for it to be shared with the public. Digital technology has fuelled the recent convergence (Deuze Citation2007; Humphreys Citation2016; Rimscha et al. Citation2018) and introduced differences in journalistic style, information-gathering, sourcing, analysis, distribution and financing, that in turn, have led to new presentation formats: Gifs, podcasts, Virtual and Augmented Reality, conversational interfaces, data visualisation, and full immersion experiences. Media organisations and journalists today must learn to operate several media channels simultaneously as the newsroom innovations of journalistic practices have led to multi-channel content production. Social media is, for instance, multi-functional and applicable in all phases of news gathering and distribution, where media outlets are not only focusing on one but often on several platforms (Cornia et al. Citation2018). Along with all the opportunities and expectations, journalism is reaching a higher level of complexity (Neuberger, Nuernbergk, and Langenohl Citation2019) through adopting their skills to new tasks (Jenkins and Jerónimo Citation2021) and smaller newsrooms, like local media, do not differ from the larger ones in how technology is used (Jerónimo, Correia, and Gradim Citation2022). This is also why studying local media production practices is relevant to the present paper.

Local media are also affected by changes in digital media, such as fragmenting and declining audiences, resource cutbacks in television, radio and newspapers, increased competition, and the requirement to communicate news 24 h a day via many platforms (Firmstone and Coleman Citation2014). It has seemed at first glance in the local media landscape that the digital media environment could make it easier to cope with challenges in comparison with other environments where new opportunities with low barriers for entry and cost of production would be enabled (Nielsen Citation2015). On the contrary, the challenges do not differ from other media. In response to them, local media has adapted their newsroom routines and editorial and business strategies to cope with the demands of the digital media environment and reflect a digital-first focus (Jenkins and Jerónimo Citation2021; Jerónimo, Correia, and Gradim Citation2022).

In coping with misinformation, disinformation and fake news, using reliable sources (Van Leuven et al. Citation2018) is one of the most important aspects of journalistic information. Fact-checking has a traditional meaning in journalism that relates to internal procedures for verifying facts prior to publication, as well as a newer sense denoting stories that evaluate the truth of statements from politicians, journalists, or other public figures publicly (Graves and Amazeen Citation2019). According to Brandtzaeg, Følstad, and Domínguez (Citation2018) traditional media, in general, and journalists, must also take on a greater responsibility for online fact checking, which is driven more by professional motives within journalism. In verifying information, the viewpoint diversity should also be taken into consideration. It is not only the case in providing audiences with a range of political viewpoints (Vos and Wolfgang Citation2018), where journalists often rely only on elite sources. Source diversity can be valuable to increasing content diversity, but multiple sources can also offer the same fundamental perspective, and it does not guarantee a diversity of perspectives (Wolfgang et al. Citation2021). Nowadays social media are used widely in news production routines as the source, also in local media (Jerónimo, Correia, and Gradim Citation2022). The fast-paced publishing environment and shortfall in journalistic resources for fact checking are potentially problematic as the volume of online information and disinformation increases, and, on the other hand, journalists working with online news publishing often report having insufficient time for verification and fact checking (Brandtzaeg, Følstad, and Domínguez Citation2018). In times of pandemics, multitasking news production processes and constant deadline pressure, where the most accessible and updated information is available on social media or the internet, raises the question of effective fact checking and the potential of a spread of misinformation, disinformation and fake news (Jerónimo, Correia, and Gradim Citation2022) but still journalists also use formal, professional, informal, and personal means in the times of the pandemic to contribute to the COVID-19 communication ecology (Perreault and Perreault Citation2021).

The issue of challenges in media production is, above all, related to the basic principles of journalism. Trust and credibility are embedded in the mission of journalism from the perspective of media ethics. The production processes within journalism should safeguard these principles (Žilič and Držanič Citation2021).

Local Media

The role of local media and journalism has been a part of several studies (Žilič and Medina Citation2011; Rao Citation2020; Mathisen Citation2021) as local media serves local democracy (Tiffen et al. Citation2014) and public debate (Ali Citation2017), as well as bringing news from micro societies where people live and work.

Local media are a constitutional part of local communities as their use strengthens community integration (McLeod et al. Citation1996). Labeling local journalism as public goods places the practice in the same category as Education, National Defence, and public parks (Ali Citation2016). We cannot stress enough the importance of their existence since local media fulfil several roles beside informing their audiences, such as creating political knowledge and maintaining civic engagement in their local communities (McLeod et al. Citation1996) and further often being important actors for building a stronger community (McCollough, Crowell, and Napoli Citation2017). Therefore, the fact that in some communities, local journalism is disappearing along with traditional news outlets (Napoli et al. Citation2017; Shaker Citation2014; Rubado & Jennings Citation2020) should raise concerns. Resulting not only in a decline in covering a varied range of topics, including local politics, where the decline of local-themed reporting can even cause a switch in local political ideology preferences (Martin & McCrain Citation2018), we should take into consideration the crucial informational role local media have in crises, such as a recent pandemic or for instance floods. Their community caretaker role is highlighted not only during the “every day” but during moments of crisis for both the communities and for the news organizations, as Mathews (Citation2021) emphasizes in his study.

In its essence, the local, investigative, and accountability journalism performed by professional journalists, is necessary to provide information about local public affairs and create a forum for discussion, inform voters, hold local elites and officials at least somewhat accountable, and assist consumers in making informed choices, helping individuals in their daily lives and ties communities together (Nielsen Citation2015; Ali Citation2016). Local political participation must not overlook local media's role in political engagement (Moy et al. Citation2004). Local media provide the knowledge or incentives to use the opportunities for participation, renew the links between individuals and their communities, serve as a forum for discussing important local issues or even offer alternative forms of participation (McLeod, Scheufele, and Moy Citation1999). On the other hand, the consequences of a decline in local coverage results in the lower ability of citizens to evaluate their political representatives, lower willingness to express opinions about the local political candidates, and lower political participation in voting (Hayes & Lawless Citation2015; Rubado and Jennings Citation2020). They are often underprivileged in human resources and income, but they still play a significant role in informing audiences, although it has been changing. If news radio stations represented the major source of local news and other information for their listeners (Wu Citation2017), the recent studies (Newman et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2021) shows a twist, where traditional local media are the sources for local politics and crime news, while the other internet sites and search engines are the source for weather forecast, jobs announcements or events.

Political media economists call the abandonment of high-quality investigative local journalism by commercial news organisations a market failure - appropriating the term used by neoclassical economists to describe the under-production of public goods (Ali Citation2016). Increasingly, information technologies are playing a role in helping communities share information (and misinformation) and fostering interaction and communication between local organisations and residents (Kavanaughab et al. Citation2014). Local media have always been challenged in adopting new production practices (Cottle and Ashton Citation1999; Musburger Citation2009; Wheatly Citation2020) and have been even more provoked in the times of the Covid-19 (Mihelj, Kondor, and Štětka Citation2022) pandemic, as they were often the first reliable information source for local communities, as well as being the voice for the community.

In Slovenia, in Central Europe, an independent country since 1991 with a population of 2,108,708 inhabitants (SURS Citation2021), there are officially 2489 media outlets (REMK Citation2021). According to Media Law (ZMed-UPB1 Citation2001) and Law about RTV (ZRTVS-1, 2005), the public service broadcaster RTV Slovenija, with their local centers, is financed by a licence fee. Other media, including local, can create income on the market, or be additionally funded by the Ministry of Culture when publishing public interest content. This income is strongly used as a vital source of income for many local media, especially for 22 radio and seven television stations that fulfill the criteria as local media with special interest (ZMed-UPB1 Citation2001).

Misinformation and Fact-Checking

Although not a new development as such, the phenomenon of fake news was once again brought to the fore in the aftermath of the 2016 US presidential election (Schapals Citation2018). The fake news phenomenon has shown the consequences of disseminating unverified information to a large audience, such as confusion, doubt and reliance on false information (Rapp and Salovich Citation2018).

Many terms have been used to describe fake news. We can understand it as fabricated or unverified content presented intentionally as verified news to mislead readers, often with an ideological, political, or economic motive (Brandtzaeg, Følstad, and Domínguez Citation2018). Two frequently used forms of fake news are misinformation and disinformation (Jahng, Eckert, and Metzger-Riftkin Citation2021), which do not share the same meaning, as misinformation is also false and inaccurate as is disinformation, but, in contrast, the intent to deceive is not present or is unclear (Ireton and Posetti Citation2018; Jin et al. Citation2020; Shin et al. Citation2018). It is important to point out that disinformation produces incorrect information intentionally to deceive and harm people (Al-Zaman Citation2021; Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017). Therefore, we see misinformation as the consequence of the (un)intended lack of professional practices in the news production process.

Misinformation during the Covid-19 pandemic reached another level of need for awareness in checking information, either for content producers or audiences. During the pandemic, information has been considered not as “established scientific facts”, but often as the “best available evidence” (Krause et al. Citation2020), which has, consequently, caused a misinformation pandemic within the »infodemic« (World Health Organization Citation2020). The constant news-demanding circle and, therefore, information overload (Islam et al., Citation2020) impede people's ability to validate the information they consume. The recent study (Kožuh and Čakš Citation2021) showed that the lower the need for cognition and the greater prior knowledge about Covid-19 that users have, the more they believe that news published on social media comprises all facts about the disease.

Firmstone and Coleman (Citation2014) described the increased pressure journalists are preparing content for social media during their news-gathering process. Besides the already heavy workload in reporting, the main strain is the need to verify all social media stories. In the study of Diekerhof (Citation2021), journalists in high-speed newsrooms, during their daily gathering activities, demonstrated three types of activities: Gathering content, checking and completing, and reliability is not in question, as, through checking and completing, the journalists demonstrate their aim for reliability. On the contrary, Duhe (Citation2008) pointed out that there is a lack of research in disaster response regarding newsroom operations. Even before the Coronavirus crisis hit, more than half of the global sample in a Digital News Report sample stated that they were concerned about what was true or false on the Internet regarding news (Newman et al. Citation2022). This fact raises even more the importance of fact-checking in news production process.

Online and social media platforms are becoming the leading sources of information for citizens worldwide, and similar patterns of global communication and media trust issues are universal (Newman et al. Citation2022; EBU Citation2021). The decline of local news and the rise of social platforms could cause a major problem in informing audiences, particularly when community members obtain the most news from social media, leaving them vulnerable to misinformation.

Media and the Pandemic of Covid-19

Emergency risk communication is vital to public health and safety (Toppenberg-Pejcic et al. Citation2019). Accurate information about risk and treatment may not be readily available (Reynolds and Seeger Citation2005); however, media communication that addresses various audiences becomes crucial.

The actions that individuals took (e.g., wearing face masks, hand washing, social distancing) might be dependent on how severe or imminent the risk of infection is perceived to be (Taha et al. Citation2020; Brug, Aro, and Richardus Citation2009; Leppin and Aro Citation2009), and, thus, the media narratives. Moreover, actions might be significantly affected by their trust in the validity of the information provided by the government, particularly the media, which largely disseminates the information. In recent years, media trust has diminished (Žilič and Udir Citation2015), and global concerns about misinformation remain high. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, more than half of those sampled stated that they were concerned about what is true or false on the Internet when it comes to news (Newman et al. Citation2020).

Some authors are discovering the special approaches needed to report on Covid as special measures that were needed in receiving and providing the information. Ersoy and Dambo (Citation2021) is advocating the peace journalism approach for reporting a global health crisis such as Covid-19. Others (Perreault and Perreault Citation2021; Li Citation2021) researched the special approaches needed for journalism in a crisis, when the media are expected to have an important role in persuading citizens to accept health information. Above all, Wenzel and Crittenden (Citation2023) discussed that many citizens declared the local media as the main source of news for Covid-19, namely, according to the Pew Research Centre survey (Shearer Citation2020), half of the US participants named local news outlets as a major source for Covid-19 news. The role of local media and the responsibility of local journalists and editors in informing their audiences, particularly in times of crisis, is in terms of providing relevant, trustful news through the professional processes of minimizing potential misinformation.

Our aim to gain data about changing working conditions and workflow, news sourcing practices and fighting misinformation approaches in local newsrooms led us to pose the following Research Questions:

RQ1: What changes in the procedures of countering the minimisation of misinformation spread in Slovenia's local media during Covid-19 compared to the pre-pandemic period?

RQ2: How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected the journalists’ perceptions of the role of local media in Slovenia?

Methods

In answering the Research Questions, we based our research on a multimethod research approach, as using a single method would not have produced sufficient depth to our analysis.

The analysis of the Media sector in Slovenia, performed between November and December 2021, was the first data collection and analysis method. It helped provide background information before conducting other methods and corroborating or refuting interview data (Yanow Citation2007). Different key documents were analysed to identify key elements, such as the media landscape in Slovenia and the position of local media and journalists: national media legislation, media strategy, all statistical data about media, ethical and professional standards for newsrooms, documents from the Association of Journalists and the Code of Conduct for media workers.

In the following two stages, we performed our study with a combination of well-proven qualitative methods on a representative sample to detect media production practices on various levels of professionals included in local news production and detect those production practices that could endanger the credibility of the local media. We used the method of a structured questionnaire for journalists (Firmstone and Coleman Citation2014; Wu Citation2017) in the second stage, and in the final, and third, semi-structured in-depth interviews for local News Editors (Vobič Citation2022; Krieken and Sanders Citation2017; Rimscha et al. Citation2018). In the mentioned methodological literature, it is widely recognised that, if handled properly, in-depth interviews are the most likely way to obtain in-depth information about the feelings, experiences, and perceptions of research subjects (Schutt Citation2001). We have chosen in-depth interviews to research the Editor's view on the period of Covid-19 as they should be capable of reflecting on the working procedures and estimating the changes in their newsrooms from their leading position in the news team. Almost a year after the start of the pandemic, which was still prevailing during the research, we saw it as an appropriate time to compare, reflect and estimate the changes in the production practices in their working environment.

We conducted 8 semi-structured interviews in Slovene with local News Editors from various types of media (print, radio, television, web), to understand how they define (e.g., How do you assess the presence of fake-news in Slovenia?), identify fake-news occurrence (e.g., How often do you perceive the deliberate dissemination of fake-news during your work?), and, for instance, which strategies have they deployed into their working procedures (e.g., Have you perceived the need for additional information verification mechanisms since the beginning of the pandemic?). In addition, all interviewees were asked to self-estimate the importance of the media they are editing (e.g., How do you assess the role of local media in Slovenia in limiting the dissemination of misleading and false information?).

Before performing the research, we obtained the ethical approval of The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Maribor. Our second and third research phases were also designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association (World Medical Association Citation2013), and the Ethical Guidelines released by the Association of Internet Researchers (Franzke et al. Citation2020).

We did not want to limit our exploration of Slovenia's local media landscape only to those 29 officially recognised local media previously mentioned in the literature review of Local media. Therefore, we defined local journalists and editors as those working in media outlets focused on the local environment or working for national media as correspondents from a specific part of Slovenia.

In the second phase, in February 2022, we invited local journalists using publicly available data and, with the help of the Slovene Association of Journalists, to participate in an online survey. The questionnaire consisted of two main parts: The demographic part and the part about the changing journalistic procedures and the role of media before and during the pandemic. We measured the variables of fact-checking procedures and the role of media with closed or partly opened questions, as well as with a set of items administered with 5-point Likert-type response categories.

In the third phase, in February 2022, we invited 12 News Editors from local media of various types (print, radio, television, online) randomly to take part in our semi-structured interview and 8 of them responded to us. We sent them the open questions and arranged phone / video-call meetings, and with these interviews, we checked the data from the survey among journalists.

In the analysis, we first approached the online survey results. Only fully concluded interviews were taken as valid and analysed in a synthetic and systematic manner. According to the research questions the answers were joined in two groups, first one answering the RQ1 and the second one answering RQ2. In addition to this the interviews were analysed afterward, and the answers were categorized using the same method as with the online questionnaire.

Results

The study stated there were some changes in Slovenia’s local media during Covid-19 compared to the pre-pandemic period. Our respondents stressed that the impact of the pandemic on their working procedures was significant. Mainly, they stated that working remotely was the most significant change. Additionally, a slightly higher percentage used fact-checking methods during the pandemic compared to the previous period. They, editors, and journalists, all stressed that trust and credibility are essential missions of local media. Accordingly, the respondents recognised the more significant role of the local media in informing audiences during the pandemic due to the health crisis.

In our local media research in Slovenia, 82 respondents took part in our online survey and 57 completed it. The remainder of the respondents were excluded as they did not answer all the questions. Among the fully accountable respondents, 63,8% were women and 36,8% men. They work in local radio stations (38,6%), print (28,1%), television (17,5%) and the web (15,8%). 89,4% were in local newsrooms. Altogether 84,6% were local journalists, and 10,6% were local correspondents for national media. Before the Covid-19 pandemic in Slovenia (20. 3. 2020) 93% worked as journalists, and the remainder began their work during the pandemic.

Use of News Sources and Social Media

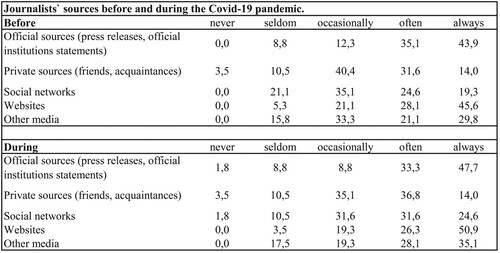

In the next part of the survey, we asked about the frequency of use of news sources in the period before and during the pandemic with a 5-points Likert scale. There was an increase of use in several types of information sources during the pandemic - web pages, social media and official sources ().

Asking about the reliability of sources on the 5-point Likert scale, the most trusted are formal sources, such as experts, who were described as mostly reliable or reliable by 89,4%, and official sources-institutions at 85,9%. Informal sources gained less reliability, and friends are mostly reliable or reliable at 47,4%, acquaintances are reliable at 0% and most reliable at 35,1%. Further, we surveyed fact-checking methods while using sources before and during the pandemic. 70,2% of journalists used various methods during their work before March 3. 2020, among which the most frequent answers to our open question were: The use of formal and informal sources, checking all participants of the story, including the opposing side, other media, web pages, additional sources, official databases, data comparison, attending events, civil society and NGOs. During the pandemic, a slightly higher percent (71,9%) used fact-checking methods, among which we could emphasise the rise in interviews – official statements and explanations, news-sources reliability checks, more online sources, and less on-site presence.

As one of our focuses is social media, we assessed the frequency of their use for different purposes in a newsroom with a 5-point Likert scale. Local journalists use social media most often (a few times a week or every working day) as a source of information (65%), for interaction with an audience (52,6%), to check the popularity of the theme (49,1%) and to encourage audience discussions (45,6%). They are never, or less than once in a month (52,6%), used for fact-checking, as only 3,5% use them for that purpose every working day.

Perceived Role of Local Journalism

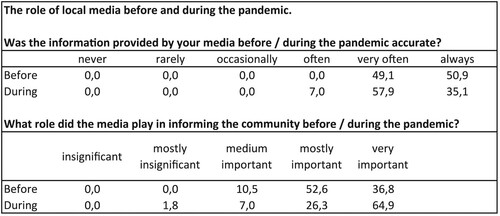

We also tried to detect the role of informing local communities as perceived by journalists before and during the pandemic. As seen in 50,9% estimated that the accuracy of the information in their media was always present, and 49,1% chose the option “very often”. A significant decrease was seen during the pandemic when the “always” accuracy of the information published by their media fell to 35,1%, 57,9% estimated it as very often and 7% as often. We continued measuring the media's perceived role on a 5-point scale before and during the pandemic. It was very important (36,8%) or most important (52,6%) before the pandemic. The respondents recognised the more significant role of the media in informing audiences during the pandemic – 64,9% saw it as very important, 26,3% as most important and 1,8% as mostly unimportant ().

Perception of Change of Work Procedures

To obtain a reflection on working procedures before and during the pandemic, we asked respondents how much the work procedures had changed between 12 March 2020 and 31 December 2021 and what the implications are for work procedures today and in the future. 45% of the respondents saw the impact of the pandemic on their working procedures as significant or very significant, and only 1,8% did not notice any changes.

Interviews

The data from interviews among local News Editors were analysed using an established qualitative analysis technique (Schapals Citation2018; Yin Citation2003), and the findings of this study are descriptive. Themes and sub-themes were identified, and we proceeded to map and interpret the themes, searching for patterns, associations, concepts and explanations to make sense of the data and find the best way to present the gathered information. The interviewers are named with codes, where letters describing their position and type of media (e = editor, r = radio, w = news web page, t = television, n = newspaper).

The Spread of Fake News

The editors interviewed for this research showed significant concern about the spread of fake news. In their view, most News Editors had positive attitudes towards the need for fact-checking procedures and pointed out the danger of fake news mostly in national media. Some of the respondents (en2, er1) expressed the belief that there is more of this kind of content in the national media, and much less or almost nothing in the local and regional media. Additionally, respondent (er1) stressed that locally it is not an issue since misinformation is more quickly recognized. Some of the interviewees (er2) explained that they are convinced that most national, and especially regional and local media, do not publish false and misleading news on purpose. However, the exceptions are some political party-related websites and media, however they follow them with a great deal of scepticism. Nevertheless, one of our respondents (et1) explained that even established print and electronic media sometimes get caught up in fake news and brought to mind the news of the death of the singer-songwriter Marko BreceljFootnote2, who then convened a press conference to deny the news and died a few months later.

Editors stressed the need for new media regulation which would address the problem of the spreading of fake news. As (en1) said, it indicates the absence of media policy and regulation that would prevent such abuses of media space. The existing Media law (ZMed-UPB1 Citation2006) allows only the correction of the published media product, not addressing what is now perceived as a broad problem in society and was prepared long before the rise of online fake news. Mostly they all stressed that trust and credibility are important missions of local media and they (ew1, et2) argued that the pandemic did not change the presence of fake news.

The connection between the rise of conspiracy theories and the presence of misleading news can be explained through the higher amount of this type of news, the demanding need for constantly updated information and the absence of reliable sources. According to our interviewer, it is not only the case for local media, misinformation and fake news was the consequence of pressure on newsrooms present in media where they were expected before. Undoubtedly, the Covid-19 period could be seen as the golden period for spreading misinformation due to the lack of reliable information originating from trusted sources, both on the audience and journalistic sites. Gaining information from reliable sources was not always an easy task for journalists, as we see in this study, and the audience was therefore taught to question the credibility of some information or sources of the information:

Certainly, the pandemic, with all the unexpectedness and violence, complexity, and extreme scale, as it spilled over from a health problem into virtually all spheres of society and life, became a launch pad or very convenient humus for spreading conspiracy theories, manipulation, directed information and so on. (en1)

The time of the epidemic was a kind of golden period of the spread of misleading information, but, at the same time, probably a period of partial loss of their power. (ew2)

Changes in Working Procedures and Fact Checking

Most of the News Editors explained that there were not any additional working procedures due to the misinformation during the pandemic, but the most significant change in organisations was the switch to remote working as much as possible as they were trying to prevent live contacts (en2, en1, ew1, et2).

Most of the News Editors showed confidence in the level of professional practices integrated into their newsrooms, explaining that fact-checking has always been a part of the procedure. In some media the fact-checking procedure can be very structured, as one of the Editors explains in the case of his media. In small local media or commercially oriented, such journalist-editor relations, which are in our case part of public service, cannot be a part of daily routine (et2), but still, they show awareness for fact-checking (et 1). The other Editor explained that journalistic self-critical judgment is crucial. The information they take from online media needs to be verified further. “But we don't have algorithmic restraints, the journalist does that”. (er1)

The fact checking procedure through hierarchical structure was explained. However, the journalist must first check the information himself, from his own trusted sources, then from officially authorised institutions, and, finally, from the individual and the institution he deals with in the journalistic product. All this goes through the sieve of the show's Editor, who, if necessary, includes the Editor of the Editorial Board, and, finally, the Editor-in-chief of the programme, because he is also responsible for the content. (et2)

Some presented the checking procedure. We have had such mechanisms integrated ever since. We check information in various ways (phone calls, emails, other communication tools). We also use social networks to extract information, but due to their unreliability, we still check information with key people, official sources, etc. (en2)

The Role of Social Media in Local Journalism Practices

News Editors in local media explained that social media are an important step in a journalists' research, mostly as a source of initial information. On the opinion of one of the News Editors Twitter is the only platform where the credibility and the competence of the source can be clearly identified at first glance and on all other Editors cannot see the difference between platforms in terms of usefulness and trustworthiness. Checking of information is a part of their working process, either with official sources or the person posting it and even more carefully when the information is not shared through the official profile of an organization or an official personal profile.

Most of the respondents agreed that social networks have become a source of information, there is no doubt about that (en1) and that social networks have become a kind of virtual “bar”, where one can get a lot of tips, as well as useful information and sources of information. (ew2)

As (en2) said: Social media posts are often a “basic” source of information, but of course, we check with key people as far as is possible. And (er1) it is impossible to check the websites of all Municipalities, Associations, organisations, etc. every day of the area we cover. The social networks are just a gadget, and these are usually sources that journalists also know personally. It was also said (ew1) that a Twitter play a relatively strong role when the identification of the information carrier is clear. In this sense, Facebook, Instagram, and comparable networks are less relevant, and they are more marked by the opinions and thoughts of everyone, regardless of their professional background in terms of what they write.

According to our analysis of the interviews, we can conclude that News Editors perceive the importance of credibility for the role and reputation of the media. This did not change because of the Covid-19 pandemic. In some cases, they perceive it as a higher role during the pandemic than they did earlier. The health crisis of the pandemic stressed once again that information at the local level is vital for any citizen. Moreover, in this perspective, they perceive today, even more than ever, that local media play an essential role in democracy.

Conclusion

The findings presented in the research provide insights into how Slovenian local journalists and editors understand, define and practice their role of minimisation of misinformation. Moreover, with a multimethod research approach, we examined whether the journalistic production procedures in local media during the pandemic of Covid-19 in Slovenia have changed and if they have affected their work. Within a country of only a few national media organisations local media play an important role in informing the citizens, so it is vital to understand media production approaches and journalistic and editor's perception of media impact in society.

Fact-checking and verification services are potentially beneficial to anyone navigating the waters of online information, especially given the threat that online misinformation may represent a well-functioning democracy (Harman Citation2014). The insight into newsrooms also familiarized us with one of the essential journalistic skills – fact-checking- and helped us answer our first research question.

Considering the increasing use of social media content in news and journalists’ time pressure to verify online sources, understanding how journalists perceive factchecking and verification services is an increasingly important topic (Brandtzaeg, Følstad, and Domínguez Citation2018). The emerging methods that use Machine Learning are helpful but require an ongoing investment by news organisations and other public trust actors to ensure that they remain accurate and valuable even as fraudulent media continues to become more and more sophisticated (Thomson et al. Citation2022). Those approaches are not available to or are still used by many media.

Our respondents did not mention the use of Artificial Intelligence aids, so the fact-checking procedures performed only by journalists themselves (to minimise misinformation) are still an essential part of media production practice, which was confirmed in our research. Journalists used established fact-checking methods, which were slightly adapted during the pandemic. They could not be on-site, so they needed to rely more on online sources and communication. The pandemic changed the priorities in using the sources, so they used more web pages, social media, and fewer official sources since they were not as responsible as expected. Consequently, a higher need was also detected for more official statements and explanations of situations, which was probably the consequence of delayed governmental official authorities’ communication. This demand goes along with the most reliable sources for journalistic work where experts and official sources dominate. The Editors consequently share confidence in the level of professionalism in their newsrooms. All of them pointed out fact-checking procedures as being present ever since, which had not changed significantly during the pandemic. They possess a lot of confidence in their employees when verifying information. However, in a previous study (e.g., Brandtzaeg, Følstad, and Domínguez Citation2018), several participating journalists saw this as increasingly challenging due to increased volume variation and turnover in online content. In the Editors’ opinion, local media are not problematic in spreading fake news, but they detect the problem more on national and global media levels.

Moreover, the Editors explained that there is less content with misleading information at the local level as it could be more quickly detected. They stressed the importance of trust and media credibility for the media future. The reason for such thinking is, in our research, seen in the self-confidence of local news editors when dealing with potential misinformation. We can add to that at least factors of geographical proximity and knowing the news sources in person. Perhaps unique and comes from our research of the Slovenian media environment is that such perception of the national media as more endangered by the potential threat of misinformation shows the absence of a more targeted media policy. It was detected as a reason for media abuse and the spread of misinformation, as the current legislation does not sufficiently address the problem of fake news in terms of prevention, regulation, and sanctions. According to the Editors, the national media policy is perceived as important in supporting professional media standards.

During the pandemic, newsrooms also adapted health safety measures, reorganised and adapted their work (Vobič Citation2022), which was also proven in our research, where the majority of the work, where possible, was converted into a remote online approach. The dependence on online sources that came to the fore could help us understand the role of social media in newsrooms, as news sources define the reality of news coverage and structure the news production process (Lechler and Kruikemeier Citation2016). Some authors (McCollough, Crowell, and Napoli Citation2017) explained that social media are used on the level of local media as interpersonal networks to function as the hub of connection and distribution of information for community members. Through interaction with an audience, journalists check the audience's support and opinion on suggested topics. Directly, they do not check the facts, but, obviously, they are studying the experiences and looking for views from the local audience.

Additionally, for journalists, social media serve as detectors of the popularity of the news story, probably aiding in setting the newsworthiness and as one of the sources of information. Editors also recognized social media as an important step in journalistic research. Because of their perceived unreliability leads to the next step – the need for fact-checking. Also, they understood that official sources at the local level are reliable sources for their news.

As a constructing part of the media landscape, local media plays an active role in informing audiences. However, there are some specifics addressing the role of local media. One discrepancy could source from the public's expectation that local journalists should act as “good neighbours” (Moon and Lawrence Citation2021), and Wenzel's analysis of local journalism (Citation2020) shows that journalists’ attachment to the ideal of professional detachment often stands in the way of news outlets trying to build closer relationships with the communities they serve as McCollough, Crowell, and Napoli (Citation2017). Despite the mentioned facts and expectations, their role in informing a local audience is undoubtedly important. Our second research question was: How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected the role of the local media? Journalists recognised the more significant role of media in informing audiences during the pandemic, and the effort to provide relevant information can be seen from their effort to obtain more resources and build close relationships with the community (McCollough, Crowell, and Napoli Citation2017). Surprisingly, we cannot label fact-checking procedures as effective as they should be since the outcome, as we observed it, was a significant decrease in the perception of the accuracy of the information published by their media during the pandemic. We can understand that journalists’ perception of the role of the media increased during the pandemic period, namely because citizens were crucially dependent on reliable information for everyday living. According to the respondents in the study, they recognised the more significant role of the media in informing audiences during the pandemic. In this need for essential information, journalists perceived their role as important to the community. However, they were aware of shortcomings connected to missing governmental and medical sources. In this respect, we understand journalists as self-critical. Some studies stressed that most editors and journalists highlight the importance of “journalism as a window” during the epidemic (Vobič Citation2022).

This result should not be seen only as the consequence of changed working conditions, highly recognised by journalists and editors, information overflow, or the absence of reliable sources for verification. It should also be understood in terms of the demand for minute-to-minute constant news flow (Van Aelst et al. Citation2021). As a result of time pressure, our respondents perceived that the accuracy of media content decreased. Nevertheless, the issue of accurate information disseminated out of the media should be dealt with carefully, as News Editors perceive the high importance of credibility for the successful media role fulfilment and the media's reputation.

In the crisis period – as media actors perceived the pandemic - the vital role of local media was detected more, which we could understand as implications for other local news organisations in the crisis period. During the pandemic, editors and journalists understood that they have an essential role and must offer reliable information vital to citizens and their everyday lives. In this respect, they are more self-critical in evaluating the level of accuracy and fact-checking, but it was understood that editors rely on journalists’ professionalism and their work of fact-checking, considering the local journalists’ reputation as they are more connected to the community. The research will contribute to understanding the content production practices relevant to local media in different environments.

Additionally, fake news is more widespread in national media as journalists are less connected to audiences and less able to check the content personally. Our research stated that local official sources and sources from experts were used more during a pandemic, probably because these sources could be more verifiable. And further, the changed working conditions demanded more working from the office and relying on reliable and verifiable sources. Finally, given the valuable role of local media and local journalists in our study, it assures that despite the technological and economic challenges they face, they remain a crucial pillar for informing citizens in a democratic society.

The results from the present study led to understanding that the perception of the role of the media in informing was higher during the pandemic period, and the procedures of minimisation of misinformation are high on the list of priorities for the reputation of the media. At the level of news production in local media, our study can help us understand additional procedures needed to minimise misinformation and help local media play an important role in society. To achieve this, we feel obligated to set some further research suggestions. National cases are always valuable in understanding media systems, as they show the specifics of a particular media landscape. Although the suggestions cannot be applied to any media landscape and should be used in local media, some lessons could also be learned for other local news organisations navigating similar challenges. In further studies, the fact-checking process in local media newsrooms could be examined in more detail through observational studies. We could investigate the need for fact-checking, even in every day, at first glance, reliable information, the frequency and type of use of tools, position, and importance in the production process, as well as the Editors supervising and sharing the findings with co-workers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the journalist and editors for their participation as well as to anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Facebook with 44% of weekly news use among users, YouTube 29%, Twitter 13%, Instagram 15%, TikTok 4%, and Snapchat 2% (Andi, 2021) and messaging apps like WhatsApp during the Pandemics (Newman et al. Citation2021),

2 We need to add that reputable Slovenian news websites, such as MMC RTV, 24ur and Siol, did not verify the news about Brecelj's death with his family, official sources or even calling Brecelj himself. It was one of the most vivid recent examples of the importance of source- and fact-checking.

References

- Al-Zaman, S. 2021. “Social Media and COVID-19 Misinformation: How Ignorant Facebook Users are?” Heliyon 7 (5): e07144. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07144.

- Ali, C. 2016. “The Merits of Merit Goods: Local Journalism and Public Policy in a Time of Austerity.” Journal of Information Policy 6: 105–128. doi:10.5325/jinfopoli.6.2016.0105.

- Ali, C. 2017. Media Localism. The Policies of Place. University of Illinois Press.

- Brandtzaeg, P. B., A. Følstad, and M. A. C. Domínguez. 2018. “How Journalists and Social Media Users Perceive Online Fact-Checking and Verification Services.” Journalism Practice 12 (9): 1109–1129. doi:10.1080/17512786.2017.1363657.

- Brug, J., A. R. Aro, and J. H. Richardus. 2009. “Risk Perceptions and Behaviour: Towards Pandemic Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16 (1): 3. doi:10.1007/s12529-008-9000-x.

- Calvo-Porral, C., V. A. Martínez-Fernández, and O. Juanatey-Boga. 2014. “La Credibilidad de los Medios de Comunicación de Masas: Una Aproximación Desde el Modelo de Marca Creíble.” Intercom: Revista Brasileira de Ciências da Comunicação 37 (2): 21–49. doi:10.1590/1809-584420141.

- Chen, Y., N. J. Conroy, and V. L. Rubin. 2015. “News in an Online World: The Need for an “Automatic Crap Detector".” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 52 (1): 1–4.

- Cornia, A., A. Sehl, D. A. L. Levy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. Private Sector News, Social Media Distribution, and Algorithm Change. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Cottle, S., and M. Ashton. 1999. “From BBC Newsroom to BBC Newscentre : On Changing Technology and Journalist Practices.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 5 (3): 22–43. doi:10.1177/135485659900500304.

- Deuze, M. 2005. What is Journalism? Professional Identity and Ideology of Journalists Reconsidered in Journalism. Sage Publications.

- Deuze, M. 2007. Media Work. Polity.

- Diekerhof, E. 2021. “Changing Journalistic Information-Gathering Practices? Reliability in Everyday Information Gathering in High-Speed Newsrooms.” Journalism Practice, doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1922300.

- Duhe, S. F. 2008. “Communicating Katrina: A Resilient Media.” International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters 26 (2): 112–127. doi:10.1177/028072700802600203.

- EBU. 2021. Trust in Media 2021. EBU Media Intelligence Service. https://www.ebu.ch/publications/research/login_only/report/trust-in-media.

- Ersoy, M., and T. M. Dambo. 2021. “Covering the Covid-19 Pandemic Using Peace Journalism Approach.” Journalism Practice, doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1945482.

- Firmstone, J., and S. Coleman. 2014. “The Changing Role of the Local News Media in Enabling Citizens to Engage in Local Democracies.” Journalism Practice 8 (5): 596–606. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.895516.

- Franzke, A. S., A. Bechmann, M. Zimmer, and C. Ess. 2020. Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0. https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf.

- Graves, L., and M. A. Amazeen. 2019. “Fact-Checking as Idea and Practice in Journalism.” In Oxford Encyclopedia of Communication. City: Oxford University Press.

- Harman, R. H. 2014. Collateral Damage. Author House.

- Hayes, D., and J. L. Lawless. 2015. “As Local News Goes, so Goes Citizen Engagement: Media, Knowledge, and Participation in US House Elections.” The Journal of Politics 77 (2): 447–462. doi:10.1086/679749.

- Humphreys, A. 2016. Social Media. Oxford University Press.

- Ireton, C., and J. Posetti2018. Journalism, ‘Fake News’ & Disinformation. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Islam, A. K. M. N., S. Laato, S. Talukder, and E. Sutinen. 2020. “Misinformation Sharing and Social Media Fatigue during COVID-19: An Affordance and Cognitive Load Perspective.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 159 (120201): 120201. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201.

- Jahng, M. R., S. Eckert, and J. Metzger-Riftkin. 2021. “Defending the Profession: U.S. Journalists’ Role Understanding in the Era of Fake News.” Journalism Practice, 1–19. doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1919177.

- Jenkins, P., and P. Jerónimo. 2021. “Changing the Beat? Local Online Newsmaking in Finland, France, Germany, Portugal, and the U.K, France, Germany, Portugal, and the U.K.” Journalism Practice 15 (9): 1222–1239. doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1913626.

- Jerónimo, P., J. C. Correia, and A. Gradim. 2022. “Are We Close Enough?” Digital Challenges to Local Journalists. Journalism Practice 16 (5): 813–827. DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2020.1818607.

- Jin, Y., T. G. van der Meer, Y. I. Lee, and X. Lu. 2020. “The Effects of Corrective Communication and Employee Backup on the Effectiveness of Fighting Crisis Misinformation.” Public Relations Review 46 (3): 101910. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101910.

- Kavanaughab, A., A. Ahujaab, S. Gadb, S. Neidigb, P. A. M. Quiñones, N. Ramakrishnanb, and J. Tedescoc. 2014. “(Hyper) Local News Aggregation: Designing for Social Affordances.” Government Information Quarterly 31 (1): 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2013.04.004.

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosenstiel. 2007. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. Three River Press.

- Kožuh, I., and P. Čakš. 2021. “Explaining News Trust in Social Media News During the COVID-19 Pandemic—The Role of a Need for Cognition and News Engagement.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (24): 12986. doi:10.3390/ijerph182412986.

- Krause, N. M., I. Freiling, B. Beets, and D. Brossard. 2020. “Fact-Checking as Risk Communication: The Multi-Layered Risk of Misinformation in Times of COVID-19.” Journal of Risk Research 23 (7–8): 1052–1059. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1756385.

- Kriekenand, V. K., and J. Sanders. 2017. “Framing narrative journalism as a new genre: A case study of the Netherlands.” Journalism 18(10). doi:10.1177/1464884916671156

- Lechler, S., and S. Kruikemeier. 2016. “Re-evaluating Journalistic Routines in a Digital age: A Review of Research on the use of Online Sources.” New Media & Society 18 (1): 156–171. doi:10.1177/1461444815600412.

- Leding, J. K., and L. Antonio. 2019. “Need for Cognition and Discrepancy Detection in the Misinformation Effect.” Journal of Cognitive Psychology 31 (4): 409–415. doi:10.1080/20445911.2019.1626400.

- Leppin, A., and A. R. Aro. 2009. “Risk Perceptions Related to SARS and Avian Influenza: Theoretical Foundations of Current Empirical Research.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16: 7–29. doi:10.1007/s12529-008-9002-8.

- Levush, R. 2019. Government Responses to Disinformation on Social Media Platforms: Comparative Summary. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/social-media-disinformation/social-media-disinformation.pdf.

- Li, Y. 2021. “Assessing the Role Performance of Solutions Journalism in a Global Pandemic.” Journalism Practice, doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1990787.

- Lischka, J. A., and M. Garz. 2021. “Clickbait News and Algorithmic Curation: A Game Theory Framework of the Relation Between Journalism, Users, and Platforms.” New Media & Society, 146144482110271–146144482110222. doi:10.1177/14614448211027174.

- Martin, G. J., and J. McCrain. 2019. “Local News and National Politics.” The American Political Science Review 113 (2): 372–384. doi:10.1017/s0003055418000965.

- Mathews, N. 2021. “The Community Caretaker Role: How Weekly Newspapers Shielded Their Communities While Covering the Mississippi ICE Raids.” Journalism Studies 22 (5): 670–687. doi:10.1080/1461670x.2021.1897477.

- Mathisen, B. R. 2021. “Sourcing Practice in Local Media: Diversity and Media Shadows.” Journalism Practice 15 (5): 1–17. doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1942147.

- McCollough, K., J. K. Crowell, and P. M. Napoli. 2017. “Portrait of the Online Local News Audience.” Digital Journalism 5 (1): 100–118. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1152160.

- Mcleod, J. M., K. Daily, Z. Guo, W. P. Eveland Jr., J. Bayer, S. Yang, and H. Wang. 1996. “Community Integration, Local Media Use, and Democratic Processes.” Communication Research 23 (2): 179–209. doi:10.1177/009365096023002002.

- Mcleod, J. M., D. A. Scheufele, and P. Moy. 1999. “Community, Communication, and Participation: The Role of Mass Media and Interpersonal Discussion in Local Political Participation.” Political Communication 16 (3): 315–336. doi:10.1080/105846099198659.

- Mihelj, S., K. Kondor, and V. Štětka. 2022. “Audience Engagement with COVID-19 News: The Impact of Lockdown and Live Coverage, and the Role of Polarization.” Journalism Studies, doi:10.1080/1461670X.2021.1931410.

- Moon, Y. E., and R. G. Lawrence. 2021. “Disseminator, Watchdog and Neighbor?: Positioning Local Journalism in the 2018 #FreePress Editorials Campaign: Journalism Practice 2018 #FreePress Editorials Campaign.” Journalism Practice, doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1981150.

- Moy, P., M. R. McCluskey, K. McCoy, and M. A. Spratt. 2004. “Political Correlates of Local News Media Use.” The Journal of Communication 54 (3): 532–546. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02643.x.

- Musburger, R. B., and G. Kindem. 2009. Introduction to Media Production: The Path to Digital Media Production. Waltham, MA: Focal Press.

- Napoli, P. M., S. Stonbely, K. McCollough, and B. Renninger. 2017. “Local Journalism and the Information Needs of Local Communities: Toward a Scalable Assessment Approach.” Journalism Practice 11 (4): 373–395. doi:10.1080/17512786.2016.1146625.

- Neuberger, C., C. Nuernbergk, and S. Langenohl. 2019. “Journalism as Multichannel Communication.” Journalism Studies 20 (9): 1260–1280. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1507685.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, C. T. Robertson, K. Eddy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2022. Digital News Report 2022. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andi, and R. K. Nielsen. 2020. Digital News Report 2020. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Shulz, S. Andi, C. T. Robertson, and R. K. Nielsen. 2021. Digital News Report 2021. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/.

- Nielsen, R. K. 2015. “Introduction: The Uncertain Future of Local Journalism.” In Local Journalism: The Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media, edited by R. K. Nielsen, 1–25. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Nielsen, R. K., and L. Graves. 2017. News You Don't Believe: Audience Perspectived On Fake News. Reuters Institute fot the Study of Journalism.

- Perreault, Mildred F., and G. P. Perreault. 2021. “Journalists on COVID-19 Journalism: Communication Ecology of Pandemic Reporting.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (7): 976–991. doi:10.1177/0002764221992813.

- Rao, U. 2020. “Remediating the Local Through Localised News Making – India’s Booming Multilingual Press as Agent in Political and Social Change.” In The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism, edited by A. Gulyas, and D. Baines. City: Routledge.

- Rapp, D. N., and N. A. Salovich. 2018. “Can’t we Just Disregard Fake News? The Consequences of Exposure to Inaccurate Information.” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 5 (2): 232–239. doi:10.1177/2372732218785193.

- REMK. 2021. Razvid medijev. Ministrstvo za kulturo Republike Slovenije. https://rmsn.ekultura.gov.si/razvid/mediji.

- Reynolds, B., and M. W. Seeger. 2005. “Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication as an Integrative Model.” Journal of Health Communication 10 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1080/10810730590904571.

- Rimscha, M. B., M. Verhoeven, I. Krebs, C. Sommer, and G. Sieger. 2018. “Patterns of Successful Media Production.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies 24 (3): 251–268. doi:10.1177/1354856516678410.

- Rubado, M. E., and J. T. Jennings. 2020. “Political Consequences of the Endangered Local Watchdog: Newspaper Decline and Mayoral Elections in the United States.” Urban Affairs Review 56 (5): 1327–1356. doi:10.1177/1078087419838058.

- Schapals, A. K. 2018. Journalism Practice 12 (8): 976–985. doi:10.1080/17512786.2018.1511822.

- Schutt, R. K. 2001. Investigating the Social World. Sage Publications.

- Shaker, L. 2014. “Dead Newspapers and Citizens’ Civic Engagement.” Political Communication 31 (1): 131–148. doi:10.1080/10584609.2012.762817.

- Shearer, E. 2020, July 2. Local News is Playing an Important Role for Americans During COVID-19 Outbreak. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/02/local-news-is-playing-an-important-role-for-americans-during-covid-19-outbreak/.

- Shin, J., L. Jian, K. Driscoll, and F. Bar. 2018. “The Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media: Temporal Pattern, Message, and Source.” Computers in Human Behavior 83: 278–287. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.008.

- SURS. 2021, October 1. V tretjem četrtletju 2021 rast števila prebivalcev. Statistični urad Republike Slovenije. https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/News/Index/10080.

- Taha, S., K. Matheson, T. Cronin, and H. Anisman. 2020. “Children and Coping During COVID-19: A Scoping Review of Bio-Psycho-Social Factors.” International Journal of Applied Psychology 10 (1): 8–15. doi:10.5923/j.ijap.20201001.02.

- Thomson, T. J., D. Angus, P. Dootson, E. Hurcombe, and A. Smith. 2022. Journalism Practice, doi:10.1080/17512786.2020.1832139.

- Tiffen, R., Jones, P. K., Rowe, D., Alberg, T., Coen, S., Curran, J., & Hayashi, K. (2014). Journalism Studies, 15 (4), 374–391. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2013.831239

- Toppenberg-Pejcic, D., J. Noyes, T. Allen, N. Alexander, M. Vanderford, and G. Gamhewage. 2019. “Emergency Risk Communication: Lessons Learned from a Rapid Review of Recent Gray Literature on Ebola, Zika, and Yellow Fever.” Health Communication 34 (4): 437–455. doi:10.1080/10410236.2017.1405488.

- Van Aelst, P., F. Toth, L. Castro, V. Štětka, C. de Vreese, T. Aalberg, A. S. Cardenal, et al. 2021. “Does a Crisis Change News Habits? A Comparative Study of the Effects of COVID-19 on News Media Use in 17 European Countries.” Digital Journalism 9 (9): 1208–1238. doi:10.1080/21670811.2021.1943481.

- Van Leuven, S., S. Kruikemeier, S. Lecheler, and L. Hermans. 2018. “Online And Newsworthy: Have Online Sources Changed Journalism?” Digital Journalism 6 (7): 798–806. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1498747.

- Vobič, I. 2011. “Online Multimedia News in Print Media: A Lack of Vision in Slovenia.” Journalism 12 (8): 946–962. doi:10.1177/1464884911398339.

- Vobič, I. 2022. “WINDOW, WATCHDOG, INSPECTOR: The Eclecticism of Journalistic Roles During the COVID-19 Lockdown.” Journalism Studies, doi:10.1080/1461670X.2021.1977167.

- Vos, T. P., and J. D. Wolfgang. 2018. “Journalists’ Normative Constructions of Political Viewpoint Diversity.” Journalism Studies 19 (6): 764–781. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2016.1240015.

- Wardle, C., and H. Derakhshan. 2017. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-researc/168076277c.

- Wenzel, A. 2020. Community-centered Journalism: Engaging People, Exploring Solutions, and Building Trust. University of Illinois Press.

- Wenzel, A. D., and L. Crittenden. 2023. “Collaborating in a Pandemic: Adapting Local News Infrastructure to Meet Information Needs.” Journalism Practice, doi:10.1080/17512786.2021.1910986.

- Wheatly, D. 2020. “A Typology of News Sourcing: Routine and Non-Routine Channels of Production.” Journalism Practice 14 (3): 277–298. doi:10.1080/17512786.2019.1617042.

- Wolf, C., and A. Godulla. 2016. “Potentials of Digital Longforms in Journalism. A Survey among Mobile Internet Users About the Relevance of Online Devices, Internetspecific Qualities, and Modes of Payment.” Journal of Media Business Studies 13 (4): 199–221. doi:10.1080/16522354.2016.1184922.

- Wolfgang, J. D., T. P. Vos, K. Kelling, and S. Shin. 2021. Journalism Studies 22 (10): 1339–1357. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2021.1952473.

- World Health Organization. 2020. Call for Action: Managing the Infodemic. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/11-12-2020-call-for-action-managing-the-infodemic.

- World Medical Association. 2013. WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. World Medical Association. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/.

- Wu, L. 2017. “Evaluating Local News on the Radio.” Electronic News 11 (4): 229–244. doi:10.1177/1931243117694672.

- Yanow, D. 2007. “Qualitative-Interpretive Methods in Policy Research.” In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods, edited by F. Fischer, and G. Miller, 405–416. Routledge.

- Yin, R. K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage.

- Zakon o medijih (uradno prečiščeno besedilo) - ZMed-UPB1. 2006. Uradni list RS, št. 110/06. http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO4955

- ZMed. 2001. Zakon o Medijih. Uradni List RS, 110/06. http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO1608.

- Žilič, S. F., and I. Držanič. 2021. “Fake News as a Challenge for Media Credibility.” In Global Media Ethics and the Digital Revolution, edited by N. Miladi. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003203551-12

- Žilič, S. F., and M. Medina. 2011. “Model of Broadcasting as a Model for Local Media: Distinctiveness with Market Orientation.” Lex Localis – Journal of Local Self-Government 9 (3): 231–245. doi:10.4335/9.3.231-245(2011).

- Žilič, S. F., and K. M. Udir. 2015. “Trust in Media and Perception of the Role of Media in Society among the Students of the University of Maribor.” Public Relations Review 41 (2): 296–298. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.11.007.