?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Natural hazard news coverage research has examined frames, sources, and journalistic roles. An examination of place in such coverage is missing. Using the hierarchy of influences model, this study analyzes the coverage of place during Hurricane Maria in three major newspapers in Puerto Rico in the pre-crisis and crisis stages of the event. The study examined the roles of routines, organizational factors, and social systems factors in the coverage of Puerto Rican municipalities and the topics covered. Results show a primary focus on highly populated areas, reliance on governmental sources, and differences across the three newspapers studied. Implications for disaster coverage as well as theoretical arguments about the hierarchy of influences are discussed.

Natural hazards in a context of the global climate emergency will continue to impact vulnerable communities around the world (Benevolenza and DeRigne Citation2019). News coverage of these hazards and their impacts is crucial for these communities (Houston et al. Citation2019). Understanding and overcoming the barriers journalists and news organizations face in their reporting of natural hazards and related disasters could save lives and protect critical infrastructure. These barriers could be internal to news organizations (e.g., lack of preparedness plans, lack of resources) as well as structural and systemic (e.g., lack of access to impacted areas, critical infrastructure collapse).

Studies examining disaster coverage have focused on the lived experience of journalists, the psychological effects of reporting traumatic events, the use of sources and frames, objectivity and advocacy, and the coverage of international disasters (e.g., Tandoc and Takahashi Citation2018).

Research examining disaster coverage has yet to focus strongly on the role of place in the coverage (see Usher Citation2019). Questions about the geographic areas (e.g., countries, regions, towns, cities, municipalities) journalists and news organizations cover when a disaster strikes have not been addressed fully. Similarly, the internal (e.g., news organizations) and external (e.g., infrastructure collapse) factors related to the coverage of places and populations have not been examined either. These factors, which we investigate in this study, include the impact of the natural hazard (e.g., infrastructure), access to sources—infrastructure collapse could prevent journalists from going to impacted places or even calling sources, and the characteristics of the news outlet (e.g., resources, size of newsroom, emergency plans, etc.).

To address this gap in the literature of disaster reporting, the present study examines the coverage of place in the context in Puerto Rican newspaper coverage of Hurricane Maria in the pre-crisis and crisis stages of the event. The study uses the hierarchy of influences model (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2013) to examine how routines, organizational factors, and social systems factors relate to the coverage of Puerto Rican municipalities affected by Hurricane Maria. The study presents theoretical contributions to the hierarchy of influences at the social systems level in the context of disaster reporting, as well as practical recommendations that could assist journalists and news organizations to cover disasters more effectively and safely.

Literature Review

Coverage of natural hazards and subsequent disasters is vital for the well-being of populations at risk (Graber and Dunaway Citation2017) and for governmental organizations that must develop preparedness plans, response, recovery, and reconstruction efforts (Houston et al. Citation2019). Victims that become stranded or need assistance—for example, people who need shelter or supplies—rely on the information communicated by the news media. Audiences also use news media as a coping mechanism, seeking comfort during difficult times (Perez-Lugo Citation2004).

Research examining journalistic performance and news content related to natural hazards and disasters has examined the challenges, both logistical as well as psychological (e.g., trauma), that journalists endure during their work (Monahan and Ettinger Citation2018). The content, particularly the frames used in disaster coverage, has also been examined (Houston, Pfefferbaum, and Rosenholtz Citation2012). However, the ways and reasons news media cover particular places and the diverse populations affected by a single disaster have not been thoroughly examined.

Place in Journalism Studies and Disaster Reporting

In a recent monograph, Usher (Citation2019) made an argument for the focus on the concept of place in journalism research. Most research has either ignored or taken for granted the role of place within a highly interconnected world. Place as a focus of inquiry could allow a better understanding of the construction of shared realities (content), unequal access to information (distribution), and consumption and processing of such content (audiences). By representing the reality they have experienced firsthand, journalists gain the trust of their audiences who are both geographically and cognitively separated from the affected places. In Usher’s (Citation2019, 132) own words:

The research on place and journalism has thus far forgotten the pivotal agency of place in creating and structuring social practice. When scholars do consider place, it is either as a backdrop to other analyses or presumed to be unchanging. What is missing from scholarly inquiry in journalism research is sustained engagement with the role of place in structuring knowledge about the world and its impact on lived experience.

Usher mentions that the few exceptions where place has been given a more prominent role include research of disaster coverage, war correspondents, and foreign correspondents: “Reporting from abroad or from a disaster zone makes it blatantly clear that where journalists are physically situated affects both what they do and why they do it, but anywhere journalists are located is a source of these insights” (Usher Citation2019, 101). Some journalists even consider it an ethical responsibility that their peers (especially the ones from national outlets) should stay connected to the local communities affected by disasters, physically or through social media (Houston et al. Citation2019). Nevertheless, past research examining place in news coverage is sparse and the concept has not been examined thoroughly in disaster reporting. In this study we respond to Usher’s call by applying the role of place in the examination of news coverage of a major disaster, a concept that is scantily examined in the literature (see Molina-Guzmán Citation2019; Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020 for recent exceptions of research about Puerto Rico). Place could be described as a geographical feature (physical place), a political entity (e.g., a city, state or territory), or a social space (e.g., a community of individuals). Here we review some of the relevant research in this area and how prior research has defined and operationalized the concept.

Studies that have operationalized a place as a political entity have identified a geographic bias in news reporting, such as Dominick’s (Citation1977) examination of US national newscasts from July 1973 to June 1975. The results showed that Washington D.C., California, and New York were the focus of approximately two-thirds of the coverage, with Washington D.C. being covered on about 50% of all national airtime (Dominick Citation1977). Moreover, Dominick (Citation1977) also compared geographic regions by creating an “attention index” that subtracts the percent of population one region occupied from the percent of news coverage time it got in the news, which eventually showed a clearer bias toward the Pacific region and the Northeast, while under-representing regions like the Midwest.

Following this line of research, Whitney et al. (Citation1989) analyzed US television news stories from 1982 to 1984 to examine whether there was a geographic bias that explained why certain areas, namely metropolitan centers, were being covered more than what is expected based on the size of their populations. Although the weight of Washington D.C. stories was 29.2% of domestic news coverage, lower than a more dramatic D.C. favoritism found by Dominick (Citation1977), Whitney et al. (Citation1989) still argued the bias was enormous. This is because the Washington D.C. population then was only 0.3% of the total US population, making the attention ratio per capita of D.C. too high compared to those of other regions (Whitney et al. Citation1989).

More recently, Jones (Citation2008) adopted the method used by previous studies and examined the attention ratios of 1982–1984, 1992–1994, and 2002–2004 in US network television evening news. The study was based on the assumption that new technologies in journalistic practice, especially the Electronic News Gathering technologies, would improve the bias situation reported elsewhere. The results showed the focusing tendency described by the “attention ratio” was strengthened dramatically in Washington D.C. and New York, while under-represented states received less attention during this period (Jones Citation2008).

Besides the bias among geographic regions, Dominick (Citation1977) also argued about the possibility of an “eclipse” effect within regions, suggesting that while certain states in their regions get over-represented, other states in the regions would get less coverage (e.g., Illinois and Michigan producing 56% of the coverage about the Midwest, while Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, Missouri and Minnesota being under-represented). The argument of “eclipse” effect was also confirmed by Whitney et al. (Citation1989). The researchers suggested the reason for this effect was that large cities in those over-represented states “eclipsed” the states without large cities.

This geographical bias that over-represents the capital and large cities can be considered as a form of social injustice in journalistic practice. Dominick (Citation1977) suggested in the eyes of media professionals, the relevance of millions of people who live in two underrepresented US states is equivalent to that of an actress, based on the similar gross airtime they each received during the same time period. Plus, if the bias-strengthening tendency from the 1980s to the 2000s described by Jones (Citation2008) has worsened since, the level of associated injustice will surely bring more social issues. The negative effects brought by geographical bias can backfire at journalists, too, as media find it difficult to earn the trust of audiences who live in less developed rural areas (Usher Citation2019). However, all these studies were focused on the 50 states and Washington D.C. only. As a side note, studies in international coverage examine the factors that predict more intense coverage of disasters, which includes geographic proximity, cultural affinity, number of fatalities, GDP, among others (see Adams Citation1986; Singer, Endreny, and Glassman Citation1991).

Even though researchers have investigated the geographical bias in journalism within and outside of the 50 US states and D.C., there are still some regions that are left unnoticed in the studies we have mentioned above: the US territories. Missing from this research is an examination of the ways journalists and news organizations prioritize places to be covered, both as a function of their routines as well as external forces outside their control. In this study, we argue that by focusing on local journalism in Puerto Rico, we will fill the gap in the knowledge about the geographical bias in regional disaster journalism. Moreover, we move from coverage at the state level to a much more localized level—municipalities—to provide a more nuanced examination that is applicable to disaster reporting. Although the studies reviewed before focused on a different scale, we argue that the relationship between place—either state or municipality—and news attention—either in national or local media—should be similar. The editorial decision-making process that leads to the determination of the newsworthiness of places should be the same regardless of scale.

Another way of examining geographical bias is to investigate source use patterns. McShane (Citation1995) analyzed two American business magazines and found out that while American sources that were in the Mid-Atlantic region were getting over-represented, the ones in the Midwestern and Southwestern regions were under-represented. Similarly, a study of the coverage of the spotted owl controversy in the Pacific Northwest of the United States showed physical distance and economic connections were both significant predictors of the number and length of stories and the number of sources (Bendix and Liebler Citation1999).

Finally, and most relevant to the Puerto Rican case, a recent study by Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez (Citation2020) examined journalistic routines, including reporting about Hurricane Maria from impacted places, but did not focus on news content. With in-depth interviews with Puerto Rican reporters, producers, and editors, the study revealed that before Hurricane Maria, reporters were sent to cover places where they had family members and/or friends, or where they were familiar with. After landfall, a similar strategy was followed, but with consideration about access to locations—many places were inaccessible due to blocked or destroyed roads—and extreme damage. In addition, due to the centralization of newspapers and other news outlets in San Juan, coupled with the makeshift emergency operation center established by the Governor in the convention center in San Juan, most reporters stayed in the capital to have easy and quick access to government officials (Nieves-Pizarro, Takahashi, and Chavez Citation2019; Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020). These results and the results of the studies described above suggest San Juan would receive a disproportionately higher amount of coverage.

Frames and Topics in Disaster Reporting

Another important area of research about disaster reporting deals with frames and topics of the coverage. Thorson (Citation2012) reviewed the literature on frames in disaster reporting and identified seven prevalent ones: economics, blame, conflict, prediction, devastation, helplessness, and solidarity. These frames can have positive or negative connotations and can become more or less prevalent depending on the stage of the crisis (pre, during, and post disaster). Similarly, Houston, Pfefferbaum, and Rosenholtz (Citation2012, 619) examined disaster coverage in the United States over a 10-year period and reported that.

… media coverage tended to focus on the current impact of disasters on humans, the built environment, and the natural environment (i.e., who was hurt or killed and what was destroyed); that disaster economics was an important topic; that disaster media coverage generally focused on the state and region related to the event; and that disaster news was largely about what was happening now.

In this study we examined the focus on the topics of economic impact, infrastructure impact, and governmental response (see Houston, Pfefferbaum, and Rosenholtz Citation2012). The latter has not been highlighted much in this past research, but its prevalence during preliminary coding in the present study warranted its inclusion.

Source Dependency

Journalists rely heavily on sources to gather raw materials for their news production processes, following a journalistic paradigm which is similar to scientific activities in the ways of gathering data (Herman and Chomsky Citation1988). Journalists’ dependency on government sources is repeatedly observed in various studies (Hallin, Manoff, and Weddle Citation1993; Watts and Maddison Citation2014). Research examining disaster coverage and emergencies also highlights the reliance on official sources, mainly governmental sources (Hornig, Walters, and Templin Citation1991; Nucci, Cuite, and Hallman Citation2009; Walters and Hornig Citation1993). In fact, the dependence on government sources is increased in crisis situations such as terrorist attacks (Li and Izard Citation2003) and food safety crisis (Powell and Self Citation2003). This comes as no surprise since government agencies coordinate evacuation, rescue, shelters, and rebuilding efforts.

However, this reliance on official sources may decrease in certain crisis scenes such as airplane hijackings (Atwater and Green Citation1988) and disasters triggered by natural hazards (Walters and Hornig Citation1993). Walters and Hornig (Citation1993) suggested that there is an alternative sourcing pattern in news contents about irregular events: most sources are victims and/or witnesses, who are typically ordinary citizens. A possible explanation is that different sources are interviewed by journalists for different purposes. When reporting disasters triggered by natural hazards, government officials are interviewed for various types of information such as general comments, direct observations, discussion about resources and plans or predictions; while victims and witnesses are usually quoted for their direct observations (Hornig, Walters, and Templin Citation1991). In a study of news coverage of the September 11 terrorist attacks, government officials were the main sources in stories with a political frame, while witnesses were considered the most frequently quoted sources in human-interest and disaster stories (Li and Izard Citation2003). Moreover, compared to television coverage about the terrorist attacks, newspaper articles showed a higher tendency to use human-interest frames instead of political frames (Li and Izard Citation2003), which led to a more evident difference between the usage of government and witness sources in television coverage. In summary, the voices of victims, experts, and other sources such as business representatives, celebrities, civil society groups are quoted less often but can become prominent under certain circumstances. This pattern was recently confirmed once again in a survey conducted with editors-in-chief of main Spanish media outlets (Mayo-Cubero Citation2020), suggesting that media professionals who take care of newsroom routines are well informed of this kind of source dependence on witnesses and victims when it comes to emergencies.

Journalists also turn to experts when there is a disaster to cover. In the September 11 coverage study, Li and Izard (Citation2003) found experts were the third most-quoted category of sources. As suggested by Berkowitz and Beach (Citation1993), media outlets tend to choose the most trusted individuals to discuss risky topics such as conflicts, and it is also better for their credibility if they call on experts to reinforce their arguments. The result, according to Carlson (Citation2009), is that the status of being experts is strengthened by continued coverage, creating a loop in which the voices of experts are highlighted while other sources get downplayed.

Another routine news source in disasters triggered by natural hazards is the group of first responders, which is shown in surveys conducted in California (Sood, Stockdale, and Rogers Citation1987) and in Spain (Mayo-Cubero Citation2020). Sood, Stockdale, and Rogers (Citation1987) suggested first responders such as police officers and firefighters are mostly preferred by journalists when there is a disaster triggered by natural hazards. Similarly, Mayo-Cubero (Citation2020) found that the group of police, civil guard, fire department, UME (Military Emergencies Unit in Spain) and Red Cross are both most adopted and most trusted by news professionals in scenarios of crises, disasters, and emergencies. Sood, Stockdale, and Rogers (Citation1987) argued the reason for this pattern of dependence is that (a) these individuals are local sources and (b) they are closer to the emergency scenes and thus considered having more to say about the events, especially the information about who have responded and what actions have been taken.

Theoretical Considerations

This study examines news coverage of Hurricane Maria in three Puerto Rican newspapers. Based on the discussion above, the specific content variable of interest is place, or the geographic focus of the stories, operationalized as one of 78 municipalities in Puerto Rico (more details in the method section). Based on the preceding discussion, we propose the following research question:

RQ1: What was the geographic focus in newspaper coverage of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico?

To examine this content we use the hierarchy of influences model (Reese and Shoemaker Citation2016; Shoemaker and Reese Citation2013). The model suggests that news content is influenced by individual characteristics of reporters, journalistic routines, organizational factors, social institutions, and social systems. The model presents concentric circles where the inner level (individual) is the least influential on content, and the outer level (social systems) is the most influential. Disaster coverage research has applied the model in various contexts (e.g., Grassau, Valenzuela, and Puente Citation2021; Kwanda and Lin Citation2020). Although the model has been criticized and reconceptualized to better fit twenty-first century journalism with a more central focus on organizations (Ferrucci and Kuhn Citation2022), the model is still an appropriate analytical tool to examine news content.

First, we examine the relationship between geographic focus and source use, which is conceptualized at the routines level of the hierarchy (Carpenter Citation2008). Journalists follow routines in news production, including finding story ideas, pitching stories to editors, contacting trusted sources, among others. Disaster reporting research has examined sources in disasters as described above (e.g., Hornig, Walters, and Templin Citation1991) but has not recently examined changes in source use patterns and more importantly, on how such use of sources related to localities struck by disaster.

RQ2: What is the relationship between geographic focus in the coverage and source use?

Second, we examine the role of organizational factors by comparing the three newspapers. The newspapers (described in the method section) have different editorial lines, target audiences, and resources that could influence the type of content produced. Therefore, we ask:

RQ3: What are the differences and/or similarities in the coverage (place, source use, and topic) between the three newspapers analyzed?

Third, the hierarchy of influences establishes that the social system level is the most influential on content, compared to the inner levels particularly the individual level. Reese and Shoemaker (Citation2016) refer to this level regarding theories of society and power as they apply to media. Most studies examining the social system level compare news content across countries or media systems (Reese and Shoemaker Citation2016). In this respect, we recognize the unique context of Puerto Rican journalism and news media system, one that is embedded in a less individualistic culture than mainstream US culture (Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020), but at the same time responds to colonialist ideologists (Subervi-Vélez, Rodríguez-Cotto, and Lugo-Ocando Citation2020). In the context of disaster reporting, other system level variables might be adequate to include, effectively expanding and reconceptualizing the social system level of the hierarchy. In this study, we argue that structural conditions of a place and its populations could be significant factors determining news coverage of localities. For instance, the level of damage because of a hurricane should prompt journalists and news organizations to cover those places more intensely than places with little damage. The Hierarchy of influences, both in its original form (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2013) and a reconceptualized form (Ferrucci and Kuhn Citation2022), do not allow for the inclusion of disruptive forces to social institutions or social systems. The present study incorporates such perspective.

Similarly, urban and highly populated areas should receive more coverage than sparsely populated areas. On the other hand, access to certain places due to infrastructure collapse (e.g., inaccessible roads) that prevent journalists from reaching those severely damaged locations could complicate the relationships mentioned above. Therefore, we ask:

RQ4: What is the relationship between geographic focus in the coverage and structural factors?

Case Study: Hurricane Maria

Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on 20 September 2017, wreaking havoc across the island. Despite what was implied by the federal authority, human life losses due to the disaster were estimated to be at least one thousand (Kishore et al. Citation2018; Santos-Lozada and Howard Citation2018), with a final estimated count being about 3000 deaths (Santos-Burgoa et al. Citation2018). Among the survivors, more than 40% of the ones that participated in a survey suffered from negative mental effects such as PTSD (Scaramutti et al. Citation2019). The electric grid of Puerto Rico, especially the transmission and distribution infrastructure, was also devastated by Maria, causing a power outage across the whole island that lasted for more than ten months in certain areas (Kwasinski et al. Citation2019). The economic losses due to the hurricane were estimated to be $95 billion, worsening the economic hardship of the island as it just went bankrupt earlier that year (Rawlins Citation2018). Some residents had left the island to evade the worsened situation after the hurricane, and nearly 160,000 of them relocated to the mainland United States, suggesting one of the most significant migrations of Puerto Ricans in recent history (Hinojosa and Meléndez Citation2018).

Apart from the negative influences mentioned above, Hurricane Maria also affected local journalistic practices. It was found that despite the existing preparation plans for hurricanes, the devastating power of the hurricane forced local journalists to improvise during the power outage, which resulted in communication loss and even access to supplies (Nieves-Pizarro, Takahashi, and Chavez Citation2019). A probable explanation offered by Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez (Citation2020) was that the plans, however good they were, could hardly be executed because the decision-making chain was broken by the loss of electricity and digital communication channels.

In this study, we examined first the pre-crisis stage (see Coombs Citation2014), which started with the earliest coverage on Hurricane Maria, particularly two days before landfall, and it ended with the landfall in Puerto Rico on the morning of 20 September 2017.

Next, we examined the crisis stage, which started when the pre-crisis stage ended on the morning of September 20th. Since the event was catastrophic, with electricity not being restored in much of the island for months (Rosario-Albert and Takahashi Citation2021), and the recovery was ongoing, the crisis stage had not concluded on 15 October 2017, which was the last day the data were collected for this study.

The post-crisis stage begins at the end of a crisis (i.e., it is not relevant to stakeholders anymore) and is characterized by preparedness actions for similar natural hazards or other events in the future (Coombs Citation2014). This last stage of the crisis is excluded from this study because our focus was on extreme conditions of the other two stages which typically lead journalists and news organizations to deviate from conventional journalistic practices.

Methods

Data Sources and Sampling

Puerto Rican newspapers. We selected the three main newspapers to provide a comprehensive analysis of print coverage. The three newspapers reach all Puerto Ricans and have the highest circulation. We acquired the PDF versions of the print edition of each newspaper to construct the dataset. El Nuevo Día is the most influential and widely read newspaper in Puerto Rico (Colón Zayas Citation2017), followed by El Vocero, the first free daily newspaper on the island (Bullock, Serigos, and Toribio Citation2016). While El Nuevo Día is considered mainstream and considered the newspaper of record, El Vocero is known for being sensationalist and serving a working-class audience group (Bullock, Serigos, and Toribio Citation2016). Metro is published by Metro International, an international media company based in Luxembourg, and has become the third free newspaper on the island (Colón Zayas Citation2017).

Time period of analysis. Newspaper articles were collected from 15 September 2017, to 15 October 2017. The start date was five days before the landfall of Hurricane Maria, which allowed for an examination of how newspapers covered Hurricane Maria considering Hurricane Irma a few days earlier. Because some newspapers stopped publication for days after Maria’s landfall due to resource shortages, energy outages, and worsened working conditions, the one-month period was set a priori, to include enough post-landfall articles in the dataset.

Construction of dataset. News articles were manually collected from the newspapers with the keywords “huracán” (hurricane) and “María,” with articles that only discussed Hurricane Irma or people named Maria being excluded. Only news articles were included, therefore op-eds, editorials, and other forms of articles were excluded. Special editions were also excluded since their focus was usually on a different topic and the hurricane was used as a mere background. For the same reason, certain articles in sports, entertainment, and other sections were excluded if they only mentioned Hurricane Maria as a secondary topic or as a reference (e.g., “this is the first match this team has played after Hurricane Maria”) without discussing more disaster-related issues such as destruction, personal loss, mental support, or humanitarian efforts.

Each article’s headline was included in a spreadsheet, along with the newspaper it was published in, publication date, the name(s) of the reporter(s), and the page number(s). A total of 1,339 articles were included from the three newspapers.

Sample size. Due to the higher volume of coverage after landfall than the days prior, we divided the dataset into two parts based on the pre-crisis and crisis stages (Coombs Citation2014) and analyzed them individually. The first part of the dataset contains all the coverage from September 15th to 20th, and the second part is the rest of the collected articles, from September 21st to October 15th. As the first subset is rather limited compared to the second one, we analyzed all the 71 articles in it; for the second subset, we calculated the sample size for each newspaper individually using the simplified formula by Yamane (Citation1967):

N is the population size; n is the sample size of each newspaper; e is the precision level (0.05).

Based on the calculation, 608 articles were randomly selected out of the total of 1268 as the post-landfall subset, making the final sample size 679 articles.

Variables

Two Spanish-speaking coders coded half of the final sample each after multiple rounds of practice tests. Intercoder reliability was calculated during practice and with the final full sample. Coders did not know which articles were included in the intercoder test. A total of 50 articles were coded by both coders and only variables with a Krippendorf’s alpha above 0.65 were retained for analysis. The threshold was decided based on the novelty of some of the variables. We discuss the limitations in the discussion section. Reliability scores are included next to the description of each variable used in the analysis.

Geographic focus. Each article was coded for the simple mention of one of the 78 municipalities of Puerto Rico. We decided to focus on the figure of municipalities because they represent both an easy element to identify and distinguish one location from another, while also acknowledging the importance of different regions receiving different foci of topic of stories (Usher Citation2019). Each of the 78 municipalities of Puerto Rico has its own local government and sense of identity. The name of a municipality was only coded if the name was explicitly mentioned. This included the headline, body of the article, and caption of images if present. An article could have multiple municipalities coded for. In addition to each individual municipality coded for, we created an index based on the total number of municipalities mentioned in any given article. All but two municipalities (Florida and Vega Baja) achieved an α of no less than 0.65 with most having an α = 1.

Sources. The concept source refers to either people who are asked by journalists to provide information or organizations that feed news material to media and their journalists (Berkowitz Citation2009). A source is operationalized as a person, organization, or document mentioned in a story and linked by attribution verbs such as “said,” “noted,” “feels,” “thinks,” “charged,” etc. A frequent term of attribution in a news story is the expression “according to” (e.g., “The ordinance has no chance,” according to Mayor Smith). Sources used in each story were coded by the number of each source present. For example, if a mayor and a legislator were coded in a story, government sources were coded as two. A source was only counted once no matter how many times that source was cited or mentioned in a story (e.g., a mayor is quoted twice in the same story). The following sources were used in the analysis (other sources had small frequencies or low reliability):

Government officials (local/state/federal): Elected or appointed persons having tax supported posts relevant for city, county, or regional government (e.g., mayors, officials working for municipal agencies). This includes spokespersons for government officials. This also includes local school officials at primary and secondary education levels. We also include elected or appointed persons having tax-supported posts relevant for state or federal government (e.g., Governor of Puerto Rico, FEMA representative). Reliability was α = 0.83.

Ordinary citizens: An average person who does not speak on behalf of an organization related to the topic covered in the story. It is often a resident affected by the disaster. Reliability was α = 0.92.

Economic impact: Includes investments, compensations, cost of infrastructure collapse, destruction or damage of buildings or homes, cost of disaster; business problems or closings and any issue related to the cost to prevent or reconstruct after the disaster. Reliability was α = 0.71.

Infrastructure impact: Built environment impacts, hazard, damage, and safety. For example, roads damaged, roofs blown away, houses torn down, antennas toppled, etc. Reliability was α = 0.7.

Political and/or governmental response: Response consists of the activities, policies, or aid taken by government leaders in local, state, or federal agencies, immediately before, during, or directly after an emergency, that save lives, minimize property damage or improve recovery; recovery includes the short-term activities that restore vital life-support systems to minimum operating standards and long-term activities that return life to normal. Reliability was α = 0.66.

FEMA claims. No damage impact was available at the time of analysis; therefore FEMA claims are used as a proxy for the impact of Hurricane Maria on infrastructure. Data were also collected from CUNY’s database (Center for Puerto Rican Studies).

Data Analysis

Out of all 78 municipalities in Puerto Rico, we picked out the 12 most covered ones to conduct the analysis of the means. The 12 municipalities got covered 734 times while all 78 got covered 1,599 times in our dataset. For the geographic focus of the coverage, we generated a heat map for all Puerto Rican municipalities and then ran a linear regression. For the comparison of source use and theme coverage, we ran independent samples t-tests to check the differences between the means of articles covering certain municipalities and the ones not covering them. For the comparison across the three newspapers, we ran ANOVAs to check if there is any statistical difference, followed by post hoc analysis if needed.

Results

Geographic Differences

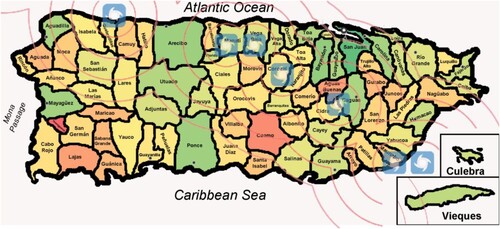

To answer RQ1, we generated a heat map based on the numbers of articles mentioning each municipality. The original map did not represent the difference between municipalities very well because zones between the two radical ends (namely over-covered San Juan and under-covered municipalities like Coamo and Hormigueros) were made more red-yellowish due to San Juan being the only dark green region. A second heat map based on the natural logarithm of the article sums was then generated to replace the original one. The difference between municipalities in the coverage was thus better visualized (). The trajectory of Hurricane Maria on 20 September 2017 was then added onto this map using the pre- and post-Hurricane Maria GIS resource from the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. While San Juan was not very far away from the trajectory of the landfall, the map shows that Ponce and Mayagüez gained much coverage despite being slightly further from the main trajectory.

RQ2 inquired about the use of sources by municipality. When mentioning more populated municipalities, the newspapers tended to quote more government officials in an article compared to when covering less populated ones (see ). Regarding ordinary citizens, the only places where there was a statistical difference are Aguadilla (p < 0.1) and Toa Baja (p < 0.05), with the former having fewer ordinary citizens quoted, and the latter having more ordinary citizens quoted when these municipalities were mentioned.

Table 1. Government sources when mentioning the 12 most covered municipalities.

Differences Across Newspapers

Regarding RQ3, the mean difference between the number of government officials quoted by El Nuevo Día (1.37 per article) and Metro (0.87 per article) is statistically significant. El Vocero (1.08 per article) did not significantly differ in its use of government sources from either of the two other newspapers (p > 0.05). Similarly, the mean difference between the numbers of ordinary citizens quoted by El Nuevo Día (0.70 per article) and Metro (0.33 per article) is statistically significant. So is the difference between El Nuevo Día (0.70 per article) and El Vocero (0.22 per article). However, the difference between Metro and El Vocero is not statistically significant.

Regarding the number of places mentioned in the coverage, the difference between El Nuevo Día (2.76 municipalities per article) and Metro (1.67 per article) is statistically significant. No significant differences were reported between El Nuevo Día and El Vocero or between El Vocero and Metro. In addition, we compared the coverage of the twelve most covered municipalities across the three newspapers (using ANOVA) and found that the only significant difference was in the tendency of covering San Juan. Metro covered San Juan less often than El Nuevo Día and El Vocero.

Regarding the themes of coverage, the analysis did not show any difference in the coverage of economic impact or political or governmental response. However, when it comes to the probability of covering the theme of infrastructure impact, El Nuevo Día (0.52), Metro (0.21), and El Vocero (0.41) were different from each other. Metro was the most different (p < 0.001 in both comparisons with the other two outlets, while the p-value of the difference between El Nuevo Día and El Vocero is 0.033) as reported in a post hoc analysis.

Geographic Focus and Population and FEMA Claims

To answer RQ4, we ran a linear regression using the population data in 2017 as the predictor of the number of articles each municipality received. The R2 of the model is 0.755 (p < 0.001). We also ran a linear regression using the Cumulative Individual Assistance applicant (data acquired from the Center for Puerto Rican Studies Citation2018) as the predictor of the number of articles each municipality received. The R2 of the model is 0.770 (p < 0.001). A post hoc analysis for the correlation showed that the Pearson correlation of the two predictors is 0.997 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study examined the geographic focus of newspaper coverage of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Applying the hierarchy of influences model (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2013), we analyzed the influence of routines (source use), organizations (comparison of three newspapers), and social systems (structural variables, population, and FEMA claims) on the mention of municipalities in the coverage before and after the hurricane.

The urban areas of Puerto Rico received more coverage than the rest of municipalities, as expected. This is consistent with past research that reported a bias toward big, populated cities and economic and political centers (Dominick Citation1977; Whitney et al. Citation1989), and consistent with previous research describing the “eclipse” effect (Whitney et al. Citation1989). In this study we show that a similar bias occurs at the local level, in this case, at the level of municipalities. Such bias could communicate to audiences which places are more important or require more attention and assistance. Such coverage could also marginalize and disempower places—this includes ecosystems and non-human species—and people that might require assistance. Nevertheless, the regression analysis shows a strong relationship between the number of articles mentioning a municipality and the FEMA claims for such municipality. It appears that newspapers did focus overall on places where more cases of damage were claimed, which is a positive aspect of the coverage. This was the case despite disruptions of news routines and the overall ineffectiveness of news organizations’ emergency plans (Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020). Additional research could explore how other impact related factors such as the number of fatalities or destruction of ecosystems are also related to the coverage of places to provide a more comprehensive analysis of how disruptions of systems affect coverage of place or other aspects of news content.

The results of this study show that there were some differences between how the three newspapers used sources and the number of places they covered. El Nuevo Día used more ordinary citizens in their coverage and more official sources than Metro and El Vocero. El Nuevo Día also covered more places than Metro. The results appear to reflect the organizational resources of El Nuevo Día, which, with a bigger newsroom than its competitors, allowed reporters to cover more areas and spend more time in the field working on the stories. Investments in newsrooms are positively associated with both content diversity as well as stronger revenue (Chen, Thorson, and Lacy Citation2005) and circulation (Li and Thorson Citation2015). In times of crisis, such investments, particularly in local news organizations due to their proximity and knowledge of local communities, could benefit the dissemination of critical and much needed information.

Regarding geographic focus, Metro was less diverse in its coverage and focused less on San Juan compared to the other two newspapers. This was expected considering the business model of Metro—as part of an international media group, it follows a similar standard practice used around the world that relies solely on advertising revenue—and its smaller newsroom. On the other hand, El Nuevo Día and El Vocero are well established newspapers in Puerto Rico with a long history covering disasters.

More governmental sources were quoted when the number of places referenced was higher, which is not unusual in disaster coverage (e.g., Hornig, Walters, and Templin Citation1991). This probably also reflects stories that were more comprehensive and in-depth, as well as the unique circumstances in Puerto Rico that led to a heavy centralization of news operations in the Puerto Rico Convention Center, which made access to government sources easier (Nieves-Pizarro, Takahashi, and Chavez Citation2019; Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020). The results did not show significant differences in the use of ordinary citizens as sources. It could be expected to see more ordinary citizen sources in areas that are more populated or that were more severely impacted, but that was not the case. Further research could examine other contexts to determine if a pattern of source use could be found.

The results slightly diverge from prior research examining the themes of the coverage (see Houston, Pfefferbaum, and Rosenholtz Citation2012). While more than a third of stories examined infrastructure impact (39.3%), and 14.4% of stories referred to economic impact, a large majority of stories covered governmental responses across all newspapers (62.9%). Economic impact and governmental response were similar across newspapers, but infrastructure impact was most prominent in El Nuevo Día. The focus on governmental responses could be attributed to delays and mishaps in the responses by state and federal governments, although more research in this area is needed to confirm this argument.

Differences in newsroom resources likely explain many of the differences across newspapers discussed above, but these differences could also be explained based on the limitations that journalists experienced accessing places, as well as the aftermath of the disaster that forced them to cope with material and personal loss (Takahashi, Zhang, and Chavez Citation2020).

Consistent with the hierarchy of influences model, the social system—in this study represented by population and impact of the hurricane—was strongly associated with the amount of coverage by municipality. Previous research using the model operationalized social systems as culture, media systems, or countries. This study adds to the model an alternative interpretation, one in which social systems are heavily disrupted (i.e., infrastructure collapse). The inclusion of other forms of disruptions, such as layoffs, technological changes, legal changes (e.g., enactment of stringent libel laws), among others, could also be taken into consideration within an influences model that centers around news organizations (see Ferrucci and Kuhn Citation2022).

The study has some limitations. Some sources such as first responders, businesses, and celebrities were not included due to low reliability coefficients or low frequencies. Additionally, the coding of mentions of municipalities was appropriate to reach acceptable reliability, but this prevented us from coding for the most relevant place covered in the story. For example, a story mainly about Yabucoa, which is the municipality where Hurricane Maria first made landfall, that mentioned in passing another municipality, was coded for both places with the same weight. However, this potential bias would have affected all municipalities mentioned, so we assume it does not affect the overall results of the study. A more nuanced examination of place could be explored in future research. Finally, we examined various structural factors and their relationship with newspaper coverage of specific municipalities but only population was a strong significant predictor. Population size and FEMA claims were very strongly correlated, which makes the inclusion of both variables redundant. We decided to include both to demonstrate at least two factors that could be considered in future studies. Also, FEMA data represent a post-disaster measure, and although we argue that those claims reflect not only population density but also the extent of infrastructure damage, it might still not be the most precise measure of the impact of the hurricane. Unfortunately, no data for damage was found during the time of this study.

Future research could explore other disasters where the impact is not as widespread as the case of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. This approach could differentiate the relationship between impact and news coverage and population and news coverage. A more precise measure of impact could differentiate between types of impacts such as human loss and infrastructure loss (e.g., critical infrastructure or social infrastructure).

Conclusion

This study responds to Usher’s (Citation2019) call for a more central focus on place in journalism studies. We applied the concept to the scholarship of natural hazard (and associated disaster) reporting research because both physical and social places are considerably disrupted during these events. The reporting from and about specific places can serve time-sensitive functions such as providing residents with information about the accessibility to places or to relief assistance. This study provides a first approximation to the study of place by conceptualizing it at the level of a local municipality. Future studies could examine alternative conceptualizations of place at different scales by using measures such as states, counties, zip codes, or urban vs. rural, or the socio-economic characteristics of populations, such as political leaning or racial/ethnic diversity. In addition, place could be expanded to incorporate social attributes and concepts examined in sociological research, such as place attachment (physical and social) or community attachment (e.g., Lewicka Citation2011).

The results of the study could be useful to news organizations working on disaster preparedness plans. Recognizing present limitations of coverage of disasters and places due to accessibility to impacted places, or lack of resources, could allow those organizations to develop plans that facilitate more comprehensive coverage. This could mean developing additional collaborations with local news outlets, freelancers, and non-profit organizations.

Finally, this study made a theoretical contribution to a reconceptualization of the social systems level of the hierarchy of influences (Shoemaker and Reese Citation2013) as applied to disaster coverage. The focus on structural variables such as infrastructure damage presents a precise way to test for the influence of disruptions in the social system in news coverage. We argue this approach could allow researchers to test the hierarchy of influences model at its most influential level going past country-level comparisons or fuzzy conceptualizations of culture. Future studies could continue to explore other ways in which the social systems level of the hierarchy of influences could be operationalized in disaster coverage.

Acknowledgement

The authors want to thank Luis Graciano Velazquez and Sydney Wojczynski for their work during the coding process. Thanks also to Manuel Chavez, Yadira Nieves Pizarro, Luis Rosario Albert, and Federico Subervi Vélez for their contributions to the project.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, W. C. 1986. “Whose Lives Count?: Tv Coverage of Natural Disasters.” Journal of Communication 36 (2): 113–122. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1986.tb01429.x.

- Atwater, T., and N. F. Green. 1988. “News Sources in Network Coverage of International Terrorism.” Journalism Quarterly 65 (4): 967–971. doi:10.1177/107769908806500420.

- Bendix, J., and C. M. Liebler. 1999. “Place, Distance, and Environmental News: Geographic Variation in Newspaper Coverage of Nthe Spotted Owl Conflict.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 89 (4): 658–676. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00166

- Benevolenza, M. A., and L. DeRigne. 2019. “The Impact of Climate Change and Natural Disasters on Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review of Literature.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 29 (2): 266–281. doi:10.1080/10911359.2018.1527739.

- Berkowitz, D. A. 2009. “Reporters and Their Sources.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 122–135. New York: Routledge.

- Berkowitz, D., and D. W. Beach. 1993. “News Sources and News Context: The Effect of Routine News, Conflict and Proximity.” Journalism Quarterly 70 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1177/107769909307000102.

- Bullock, B. E., J. Serigos, and A. J. Toribio. 2016. “Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics.” Spanish-English Codeswitching in the Caribbean and the US 11: 171. doi:10.1075/ihll.11.07bul.

- Carlson, M. 2009. “Dueling, Dancing, or Dominating? Journalists and Their Sources.” Sociology Compass 3 (4): 526–542. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00219.x.

- Carpenter, S. 2008. “How Online Citizen Journalism Publications and Online Newspapers Utilize the Objectivity Standard and Rely on External Sources.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 85 (3): 531–548. doi:10.1177/107769900808500304.

- Center for Puerto Rican Studies. 2018, April 12. Centro's Data Hub. Arcgis.com. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap = e72119d2f9d347899cc2d221d4bec45a&extent = −68.2619,17.2094,−64.4496,19.3893.

- Chen, R., E. Thorson, and S. Lacy. 2005. “The Impact of Newsroom Investment on Newspaper Revenues and Profits: Small and Medium Newspapers, 1998–2002.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82 (3): 516–532. doi:10.1177/107769900508200303.

- Colón Zayas, E. R. 2017. Media Structures and the Press in Cuba, Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, the Repeating Islands.

- Coombs, W. T. 2014. Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dominick, J. R. 1977. “Geographic Bias in National TV News.” Journal of Communication 27 (4): 94–99. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01862.x.

- Ferrucci, P., and T. Kuhn. 2022. “Remodeling the Hierarchy: An Organization-Centric Model of Influence for Media Sociology Research.” Journalism Studies 23 (4): 525–543. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2022.2032805.

- Graber, D. A., and J. Dunaway. 2017. Mass Media and American Politics. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press.

- Grassau, D., Valenzuela, S., & Puente, S. (2021). What “Emergency Sources” Expect from Journalists: Applying the Hierarchy of Influences Model to Disaster News Coverage. International Journal of Communication 15: 1349–1371. doi:1932–8036/20210005.

- Hallin, D. C., R. K. Manoff, and J. K. Weddle. 1993. “Sourcing Patterns of National Security Reporters.” Journalism Quarterly 70 (4): 753–766. doi:10.1177/107769909307000402.

- Herman, E. S., and N. Chomsky. 1988. The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon.

- Hinojosa, J., and E. Meléndez. 2018. Puerto Rican Exodus: One Year Since Hurricane Maria. New York: Center for Puerto Rican Studies.

- Hornig, S., L. Walters, and J. Templin. 1991. “Voices in the News.” Newspaper Research Journal 12 (3): 32. doi:10.1177/073953299101200304.

- Houston, J. B., B. Pfefferbaum, and C. E. Rosenholtz. 2012. “Disaster News.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 89 (4): 606–623. doi:10.1177/1077699012456022.

- Houston, J. B., M. K. Schraedley, M. E. Worley, K. Reed, and J. Saidi. 2019. “Disaster Journalism: Fostering Citizen and Community Disaster Mitigation, Preparedness, Response, Recovery, and Resilience Across the Disaster Cycle.” Disasters 43 (3): 591–611. doi:10.1111/disa.12352.

- Jones, S. 2008. “Television News: Geographic and Source Biases, 1982-2004.” International Journal of Communication 2: 223–252. doi:1932-8036/20080223.

- Kishore, N., D. Marqués, A. Mahmud, M. V. Kiang, I. Rodriguez, A. Fuller, P. Ebner, et al. 2018. “Mortality in Puerto Rico After Hurricane Maria.” New England Journal of Medicine 379 (2): 162–170. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1803972.

- Kwanda, F. A., and T. T. Lin. 2020. “Fake News Practices in Indonesian Newsrooms During and After the Palu Earthquake: A Hierarchy-of-Influences Approach.” Information, Communication & Society 23 (6): 849–866. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1759669.

- Kwasinski, A., F. Andrade, M. J. Castro-Sitiriche, and E. O’Neill-Carrillo. 2019. “Hurricane Maria Effects on Puerto Rico Electric Power Infrastructure.” IEEE Power and Energy Technology Systems Journal 6 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1109/JPETS.2019.2900293.

- Lewicka, M. 2011. “Place Attachment: How far Have we Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (3): 207–230. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001.

- Li, X., and R. Izard. 2003. “9/11 Attack Coverage Reveals Similarities, Differences.” Newspaper Research Journal 24 (1): 204–219. doi:10.1177/073953290302400123.

- Li, Y., and E. Thorson. 2015. “Increasing News Content and Diversity Improves Revenue.” Newspaper Research Journal 36 (4): 382–398. doi:10.1177/0739532915618408.

- Mayo-Cubero, M. 2020. “News Sections, Journalists and Information Sources in the Journalistic Coverage of Crises and Emergencies in Spain.” El Profesional de la Información (EPI) 29 (2): 1–12. doi:10.3145/epi.2020.mar.11.

- McShane, S. L. 1995. “Occupational, Gender, and Geographic Representation of Information Sources in U.S. and Canadian Business Magazines.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 72 (1): 190–204. doi:10.1177/107769909507200116.

- Molina-Guzmán, I. 2019. “The Gendered Racialization of Puerto Ricans in TV News Coverage of Hurricane Maria.” In Journalism, Gender and Power, edited by C. Carter, L. Steiner, and S. Allan, 331–346. New York: Routledge.

- Monahan, B., and M. Ettinger. 2018. “News Media and Disasters: Navigating Old Challenges and New Opportunities in the Digital Age.” In Handbook of Disaster Research. Second edition, edited by Havidán Rodríguez, William Donner, and Joseph Trainor, 479–495. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_23.

- Nieves-Pizarro, Y., B. Takahashi, and M. Chavez. 2019. “When Everything Else Fails: Radio Journalism During Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.” Journalism Practice 13 (7): 799–816. doi:10.1080/17512786.2019.1567272.

- Nucci, M. L., C. L. Cuite, and W. K. Hallman. 2009. “When Good Food Goes Bad.” Science Communication 31 (2): 238–265. doi:10.1177/1075547009340337.

- Perez-Lugo, M. 2004. “Media Uses in Disaster Situations: A new Focus on the Impact Phase.” Sociological Inquiry 74 (2): 210–225. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.2004.00087.x.

- Powell, L., and W. R. Self. 2003. “Government Sources Dominate Business Crisis Reporting.” Newspaper Research Journal 24 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1177/073953290302400207.

- Rawlins, G. 2018. “Puerto Rico’s Economic Missteps.” Journal of Applied Business and Economics 20: 185–195.

- Reese, S. D., and P. J. Shoemaker. 2016. “A Media Sociology for the Networked Public Sphere: The Hierarchy of Influences Model.” Mass Communication and Society 19 (4): 389–410. doi:10.1080/15205436.2016.1174268.

- Rosario-Albert, L., and B. Takahashi. 2021. “Emergency Communications Policies in Puerto Rico: Interaction Between Regulatory Institutions and Telecommunications Companies During Hurricane Maria.” Telecommunications Policy 45 (3): 102094. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2020.102094.

- Santos-Burgoa, C., A. Goldman, E. Andrade, N. Barrett, U. Colon-Ramos, M. Edberg, A. Garcia-Meza, et al. 2018. Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.

- Santos-Lozada, A. R., and J. T. Howard. 2018. “Use of Death Counts from Vital Statistics to Calculate Excess Deaths in Puerto Rico Following Hurricane Maria.” Jama 320 (14): 1491–1493. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10929.

- Scaramutti, C., C. P. Salas-Wright, S. R. Vos, and S. J. Schwartz. 2019. “The Mental Health Impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and Florida.” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 13 (1): 24–27. doi:10.1017/dmp.2018.151.

- Shoemaker, P. J., and S. D. Reese. 2013. Mediating the Message in the 21st Century: A Media Sociology Perspective. New York: Routledge.

- Singer, E., P. Endreny, and M. B. Glassman. 1991. “Media Coverage of Disasters: Effect of Geographic Location.” Journalism Quarterly 68 (1-2): 48–58. doi:10.1177/107769909106800106.

- Sood, B. R., G. Stockdale, and E. M. Rogers. 1987. “How the News Media Operate in Natural Disasters.” Journal of Communication 37 (3): 27–41. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1987.tb00992.x.

- Subervi-Vélez, F., S. Rodríguez-Cotto, and J. Lugo-Ocando. 2020. The News Media in Puerto Rico: Journalism in Colonial Settings and in Times of Crises. New York: Routledge.

- Takahashi, B., Q. Zhang, and M. Chavez. 2020. “Preparing for the Worst: Lessons for News Media After Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.” Journalism Practice 14 (9): 1106–1124. doi:10.1080/17512786.2019.1682941.

- Tandoc, Jr. E. C., and B. Takahashi. 2018. “Journalists are Humans, Too: A Phenomenology of Covering the Strongest Storm on Earth.” Journalism 19 (7): 917–933. doi:10.1177/1464884916657518.

- Thorson, E. 2012. “The Quality of Disaster News: Frames, Disaster Stages, and a Public Health Focus.” In Reporting Disaster on Deadline, edited by Lee Wilkins, Martha Steffens, Esther Thorson, Greeley Kyle, Kent Collins, and Fred Vultee, 74–85. New York: Routledge.

- Usher, N. 2019. “Putting “Place” in the Center of Journalism Research: A way Forward to Understand Challenges to Trust and Knowledge in News.” Journalism & Communication Monographs 21 (2): 84–146. doi:10.1177/1522637919848362.

- Walters, L. M., and S. Hornig. 1993. “Profile: Faces in the News: Network Television News Coverage of Hurricane Hugo and the Loma Prieta Earthquake.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 37 (2): 219–232. doi:10.1080/08838159309364217.

- Watts, R., and J. Maddison. 2014. “Print News Uses More Source Diversity Than Does Broadcast.” Newspaper Research Journal 35 (3): 107–118. doi:10.1177/073953291403500309.

- Whitney, D. C., M. Fritzler, S. Jones, S. Mazzarella, and L. Rakow. 1989. “Geographic and Source Biases in Network Television News 1982–1984.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 33 (2): 159–174. doi:10.1080/08838158909364070.

- Yamane, T. 1967. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis. New York: Harper & Row.