ABSTRACT

Thumbnails and link previews play an outsized role in determining which online content is shared, seen, and engaged with. But conventions for these vary depending on the platform and the content creator. Journalists and non-journalists alike use and sometimes design these thumbnails with often striking differences. On some news aggregators, like Apple News or Google News, the bulk of the thumbnails are photographs related in some way to the linked content. Yet, on other platforms, such as YouTube, the thumbnails are often bespoke designs that allow for more storytelling freedom and potentially more ethical risk compared to camera-based images. This study, informed by visual news values, uses the context of the 2022 stabbing homicide of four University of Idaho students to systematically examine all YouTube thumbnails related to the murder suspect in the first four days after he was publicly identified. In doing so, this study is able to contribute to our understanding of the visual presentation of a crime-related topic with limited source material and is also able to shed much-needed light on how journalistic practices and conventions compare to those of non-journalists in the selection and design of image thumbnails on YouTube.

Introduction

Thumbnails are one of the chief gateways to online social media content and are an important way that aggregators, such as YouTube, provide users an opportunity to preview content before deciding whether it’s relevant and worth their time (Weismueller and Harrigan Citation2021, june). These thumbnails are used by both journalists and non-journalists to attract viewers and provide a visual snapshot of the content they link to. As will be discussed more fully in the literature review, the simplest option to generate YouTube thumbnails is to select a frame from the uploaded video and use it as an indication of the content therein. However, given the increasingly intense pressure news outlets and non-journalists alike face in attracting attention and sustaining engagement, both types of content creators often design custom thumbnails for each video in attempts to please the platform’s ranking algorithm and maximize the chance of views (Lamot Citation2022).

The specific images used in the thumbnail and the way these thumbnails are designed are of outsized importance in generating an emotional reaction in viewers, in framing the topic in a certain way, and in prompting viewers to click or tap through to the linked content (Shimono, Kakui, and Yamasaki Citation2020; Weismueller and Harrigan Citation2021, June). Given the intense pressure journalists and content creators face for eyeballs and advertising revenue, mediated by algorithms with certain biases that privilege certain types of content or attributes over others, journalists and content creators must decide how far is too far and whether their communication choices stray from reporting the facts to sensationalizing them or even peddling rumors, speculation, and baseless claims (Christin Citation2020; Moyo, Mare, and Matsilele Citation2020). Both groups have potentially different motivations for creating content and engaging with audiences, as is discussed in the literature review, and understanding how these motivations potentially affect the selection or design of thumbnails is important to better understand journalistic practice and conventions in digital culture, more broadly.

This study is interested in thumbnails and comparing how journalists and non-journalists use them to promote their content on YouTube during the context of an ongoing murder investigation with a recently named suspect, Bryan Kohberger, who is accused of murdering four University of Idaho students in November 2022. In doing so, this study, informed by visual news values, is able to contribute to our understanding of the visual presentation of a crime-related topic with limited source material and to offer insights into how journalist and non-journalist accounts differ in their thumbnail design choices. Comparing how journalist and non-journalist thumbnails are designed and/or selected is important given concerns about lagging trust and credibility in news (Munyaka, Hargittai, and Redmiles Citation2022) and in how the public often groups together multiple types of content providers under the vague “the media” umbrella. Understanding the practices and values of both groups is important to offer insights into how journalist and non-journalist accounts, groups with different motivations, differ in their thumbnail design choices.

We begin our study by providing brief background information on the killings to establish the necessary context to appreciate later in the findings section which images were used in the thumbnails that were later published once police publicly identified the suspect. Next, we survey the relevant literature to provide an overview of YouTube thumbnails; content creators’ motivations and journalistic conventions related to visual integrity and accuracy; mugshots in digital media; and newsworthiness and visual news values. After this, we outline the study’s method before reporting findings and contextualizing them for journalism studies academics and professionals.

Background Context on the “Idaho 4” Killings, Suspect, and Reaction

On Nov. 13, 2022, four University of Idaho students—three women and one man, all in their early 20s—were fatally stabbed around 3 or 4 am at a rented residence on King Road in Moscow, Idaho, U.S.A. (Sun, Bogel-Burroughs, and Kovaleski Citation2022). The following month, state police and a Federal Bureau of Investigation SWAT team arrested the murder suspect, Bryan Kohberger, at his parent’s home in Pennsylvania. Police photographed him on Dec. 30 at the Monroe County (PA) Correctional Facility and publicly released this mugshot of the suspect wearing a suicide-prevention vest. Before his arrest, Kohberger had obtained an associate’s degree in psychology in 2018, a Bachelor of Arts in 2020 and a Master of Arts in 2022, both in criminal justice from DeSales University. He also was accepted into a criminal justice PhD program at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington (about 10 miles from Moscow, Idaho) and finished his first semester nine days before his arrest.

In the days and weeks following the crime, the local police department where the crime was committed publicly decried the spread of mis- and disinformation related to this case and mentioned it in a December 2022 press release that said: “There is speculation, without factual backing, stoking community fears and spreading false facts” (Moscow Police Department Citation2022). The Department said this mis/disinformation was a “huge distraction” as it required significant police resources to verify and debunk claims (Sharp Citation2022). Mis/disinformation in visual form is often harder to detect and is more effective due to the way it frames information implicitly (Thomson et al. Citation2022). It is also widespread given the cognitive biases humans have toward visuals and to processing visual information heuristically (Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2019). For these reasons, the humble yet influential thumbnail, as the image shown on platforms such as YouTube as well as on third-party sites as link previews, is vitally important for further study.

Literature Review

YouTube Thumbnails

Thumbnails serve as a visual preview of the content associated with a related link. They are used on aggregator websites, such as YouTube, to visually show search results and related content as well as on social media sites as “preview links,” which provide a visual snapshot of the link’s content when it is shared on a third-party site. Thumbnails with eye-catching elements serve an important function in attracting attention online (Shimono, Kakui, and Yamasaki Citation2020). Indeed, researchers have found that thumbnails are “one of the most powerful tools to make people click a video” (Weismueller and Harrigan Citation2021, june). Thumbnails with eye-catching colors (especially more saturated ones), with a face, and with superimposed text are frequently mentioned as ways to make these visual previews more effective (Shimono, Kakui, and Yamasaki Citation2020).

As previously mentioned, YouTube can automatically generate three potential thumbnails from key points in the video using an algorithm to identify frames that aren’t blurry. However, these auto-generated thumbnails are often less visually interesting or strategic than bespoke (“multimodal”) thumbnails, as discussed further in the next paragraph. For this reason, YouTube also allows users to upload their own image file (which doesn’t have to originate from the video) to serve as their video’s thumbnail. The users who elect for custom thumbnails can then include their own branding and might design a from-scratch thumbnail that juxtaposes elements that don’t exist in real life. For example, users could select a photo of an astronaut combined with a picture of the surface of Mars to suggest that humanity has visited the planet. This potential for visual sensationalism and clickbait (see Vitadhani, Ramli, and Purnamasari Citation2021) warrants further study of thumbnails as small windows into larger pieces of content.

Thumbnails can be mono- or multi-modal. Multimodality at its most basic refers to a multiplicity of modes and can be quite expansive. Such modes can include aspects like image, music, speech, writing, color, and dimensionality, among others (Jewitt Citation2009). In this particular context (two-dimensional YouTube thumbnails), we operationalize multi-modality as the integration of multiple communication modes (photographs; text; symbols, such as arrows and speech bubbles; emoji; screenshots; illustrations, and other lines, patterns, and shapes). Multi-modal compositions can be simple composites of two or more images (what Wong [Citation2019] terms “collage”) to more elaborate compositions that include many images over which is overlaid text, emoji, and other effects. In contrast, a monomodal thumbnail would communicate through only a single mode (e.g., a text-only thumbnail or a thumbnail with only a single image).

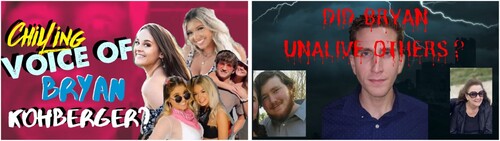

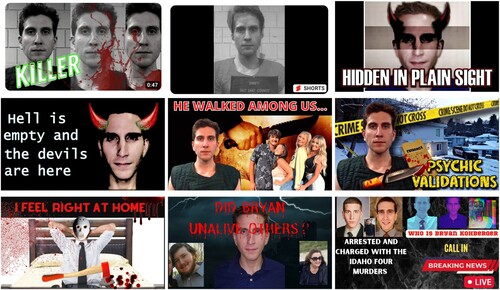

As it relates to language, writing, and text, the meaning of numbers, letters, words and sentences is important but equally so is the aesthetic quality of those symbols (Lester, Martin, and Smith-Rodden Citation2022). For example, in the two thumbnails shown in , the colors (yellow and red) and the shape of the letters (to mimic dripping blood and to connote a thrilling effect) present a vastly different emotional reception and potential for audience interpretation than if they were rendered in neutral colors or typefaces with different personality characteristics (Brumberger Citation2003). These multi-modal affordances and accompanying semiotic decisions anchor more concretely a particular meaning compared to the more polysemous nature of mono-modal visuals. The discursive effects of these semiotic choices will be discussed more fully in the “Newsworthiness and visual news values” section.

In contrast to ethical guidance around the production and editing of photographs, as will be discussed in the next section, industry guidance around specific practices related to using and stylizing typefaces and symbols is much less common, at least in journalistic contexts (Lester, Martin, and Smith-Rodden Citation2022), though, of course, generic principles such as adherence to the truth remain. Such generic principles, however, can sometimes be challenging to apply to the visual realm.

Content Creators’ Motivations and Journalistic Conventions Related to Visual Integrity and Accuracy

Both journalists and non-journalists are vying for the public’s attention in an information-saturated digital media environment yet how they approach image selection and design of their channels’ thumbnails can reflect the different motivations and values that drive both groups. YouTube content creators, for example, are often motivated by a desire for social recognition, a desire to deepen their skills, a desire to be entertained, a desire to explore self and find a community, or a desire to make money (Buf and Ștefăniță Citation2020; Ahmad et al. Citation2022; Young & Wiedenfeld, Citation2022). In contrast, journalists are often motivated by a desire to make a difference and to pursue a career with adventure and variety, though a smaller proportion are motivated by fame (Coleman et al. Citation2018). Notably, this research found that journalists don’t enter the field because of financial prospects. These differences in motivations and values can affect how journalists and non-journalists alike choose to tell a story and stylize the visual essence—in the form of a thumbnail—of that story. In addition to motivations for making content for public consumption, journalists’ decisions are also affected by professional norms and ethical codes of conduct.

Journalistic practice is informed by professional codes of conduct as well as industry conventions (Lester, Martin, and Smith-Rodden Citation2022). Leading professional associations, such as the National Press Photographers Association and the Society for News Design, both of which are based in the U.S.A., mention broad principles, such as accuracy, fairness, and comprehensiveness, in their respective codes of ethics (Society for News Design Citation2023; NPPA Citation2023). However, the specific application of these principles is left to the judgment of individual news workers. Industry organizations provide more specific guidance about certain operations that they deem unethical or less ethical. For example, industry sources tend to regard cropping of news photographs as acceptable as long as it doesn’t mislead viewers but tend to view the insertion or removal of elements within the frame as nearly uniformly unethical (Ferrucci and Taylor Citation2019). Some industry sources regard “subtle” changes to image saturation or the application of filters as being acceptable (Ferrucci and Taylor Citation2019) but even subtle changes to color or to highlights and shadows can make an image look more foreboding, such as in the infamous case of Time Magazine’s darkening of O.J. Simpson’s police mugshot in 1994. As such, context is always key when interpreting ethics.

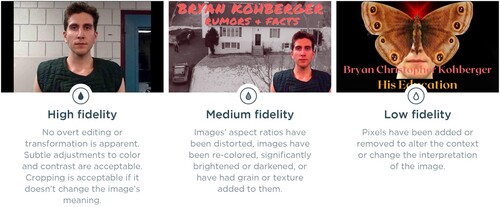

Specific ethical guidance around the selection and design of thumbnails accompanying news stories is lacking. Some emerging research (see Kim et al. Citation2023) has explored best practices for designing data visualization thumbnails but guidance for other types of news presentation thumbnails has lagged. As such, this study draws on the extant photojournalism ethics guidance from industry bodies, professionals, and the scholarly literature to propose the following three-level assessment of fidelity as it relates to thumbnail design. We operationalize fidelity as the degree of exactness or accuracy of reproduction to the original visual source material so that later in our analysis we can consider how close or far from observable reality the images and YouTube thumbnail compositions in this sample are. Visual source material (e.g., a police mugshot or a photo from the crime scene) that had no overt editing or transformation are classified as high fidelity. In this definition, no pixels can be added or removed from the image (though cropping is acceptable if this doesn’t change the meaning of the image) and only subtle adjustments to contrast and color are acceptable. Images that have been distorted or skewed from their native aspect ratio, images that have had texture or grain added to them, or images that have re-colored, tinted, or significantly brightened or darkened have been defined as medium fidelity. Images where pixels have been added or removed to alter the context (with the exception of removing the background on a simple headshot or adding in channel branding) or change the interpretation of the image were classified as low fidelity. The addition of text in a thumbnail is a component of mono- or multimodality and is relevant to that aspect rather than to fidelity, which concerns the visual source material and any discernible edits made to it. See for a visual overview and indicative examples of these fidelity definitions.

Questions of fidelity and ethics raise longstanding debates around sensationalism, trivialization, and exaggeration, and the degree to which journalists should engage in practices, such as “clickbait” (Einstein Citation2016) labels or dramatic type and image treatments, to garner views despite the potential for misleading audiences or affecting audience perceptions. These questions are important given the consistent evidence that suggests audiences are concerned about sensationalism and that sensationalist practices negatively affect audiences’ trust in news (Watkins et al. Citation2017; Newman and Fletcher Citation2017; Kleemans et al. Citation2017; Fisher et al. Citation2021).

Mugshots in Digital Media

Mugshots have long been part of news coverage and illustrate a long-standing relationship between journalists and law enforcement (Chermak and Weiss Citation2005). They also confront naive notions of photography as an objective practice for the way they construct cultural notions of criminality (Finn Citation2009).

Mugshots emerged in the late 1800s as part of a larger trend toward professionalization in policing. Alphonse Bertillon started the world’s first forensics laboratory in France and established the practice of systematically cataloging criminals with standardized photos that resemble the mugshots of today (Ellenbogen Citation2012). Physiognomy was popular at the time, and it was thought that certain physical features might be associated with criminality (Sekula Citation1986). While this pseudoscience has been disproved, law enforcement agencies around the world continue to use mugshots for the purposes of cataloging individuals (Osipov Citation2020).

In the U.S., mugshots are used widely in crime coverage, and might be thought of as visual information subsidies from law enforcement to news media. An information subsidy, as theorized by Gandy (Citation1982), influences coverage by providing content at lower cost. Policing is highly reliant on public relations, and mug shots, much like perp walks or photo-opportunities that display seized drugs, reassure the public that law enforcement is doing its job (Chermak and Weiss Citation2005; Reiss Citation1971). Indeed, the mug shot as police public relations has its roots in an early effort from the newly established American F.B.I in the 1800s, which used “wanted posters” as a way to advance its authority (Hall Citation2009).

Because mugshots are documents of public record, they are almost always free to obtain and publish. And because they carry the authority of law enforcement, journalists are able to construct their own credibility in news (Chermak Citation1995; Kaniss Citation1991).

Until recently, mugshots served as popular content for some news organizations, which published online galleries of these (Elliott Citation2011). Mugshots published online can create serious problems for an individual who was charged with a minor crime but cannot escape the criminalizing image that is delivered from a Google search of their name (Brown Citation2019). Digital images have the potential to exist forever online, however, and some conventional news organizations have dropped the practice out of ethical concern, choosing to publish mugshots individually and with more consideration for context (Blakinger Citation2020). Even when a mugshot does not include height-lines or other markers of police archiving, its creation in the context of an arrest marks the portrait with shame (Finn Citation2009). This is especially problematic in places like the U.S. where mugshots can be published before a person has gone through a trial to establish their guilt. While professional journalists are encouraged to contextualize a mug shot with the warning that a person is charged, not guilty (Associated Press Stylebook Citationn.d.), non-journalists are under no pressure to do the same. In the digital age, mugshots, like many online images, often travel without gatekeeping or friction, allowing anyone with a computer or smartphone to repost, edit, or embed the image in their own content.

The semiotics of criminality also seems to be a reason for the genre’s popularity on social media. When Brock Turner, also known as the “Stanford Rapist,” was convicted in connection with a brutal assault against a classmate, New York Magazine published his yearbook photo, inciting outrage on social media from observers who believed he was receiving gentler treatment than he deserved. When journalists finally did publish digital copies of Turner’s mugshot, social media users quickly shared them in a visual celebration of their contempt (Bock Citation2020).

Newsworthiness and Visual News Values

We employ the theoretical concept of visual news values (Bednarek and Caple Citation2017) to help us uncover ideological meanings related to a polarized topic such as a suspected murderer’s arrest and public identification. In this way, we use visual news values to explore not only what is visually represented but how it is visually represented.

Caple, Huan, and Bednarek (Citation2020) define newsworthiness as “the worth of an event to be reported as news” (1) and suggest it is constructed through news values, such as conflict, proximity, and unexpectedness, etc. These are socioculturally derived values rather than ones that are “innate” in the event. Caple, Huan, and Bednarek (Citation2020) suggest the term event can cover both material and semiotic events, such as the people involved in an event or topic, the location where the event or topic happens, and the surrounding context. The discursive approach that Caple and colleagues draw on is interested in how news values are constructed (presented/treated) as news rather than on how events are selected as news. As a form of discourse analysis, this approach focuses on the meaning-making potential of texts. In sum, it links commonly recurring news values to the specific visual semiotic resources (via forms, expressions, and techniques) that construct these values in published news stories (or, as in this case, in the thumbnails that link to them).

This study considers seven of the news values that Bednarek and Caple (Citation2017) propose. These include:

Consonance (the event is discursively constructed in ways that conform to stereotypes that members of the target audience hold about the people, social groups, organizations, or nations represented)

Impact (the event is discursively constructed as possessing significant effects or consequences)

Superlativeness (the event is discursively constructed as of high intensity or large scale/scope)

Negativity (the event is discursively constructed as negative. Examples include criminal acts, conflicts, controversies, and disasters)

Personalization (the event is discursively constructed to give a “human face” to the issue and focuses on non-elite people)

Proximity (the event is discursively constructed as geographically or culturally near to the publication location or target audience)

Unexpectedness (the event is discursively constructed as unexpected, unusual, strange, or rare)

These news values are categorical and scalar rather than numerical or quantitative. For example, a news photograph that shows a location in the same town or city as the target audience constructs a higher degree of proximity compared to references to a nearby region or to the country itself.

Bednarek and Caple (Citation2017) also note how typography, framing, color, and layout can function as semiotic resources that help construct news value(s). Regarding typography, capitalization (of either key words or of the entire “headline”) can draw attention and, depending on the context, reinforce one or more news values. For example, in this June 2023 headline published by the DailyMail (Jennifer Aniston, 54, reveals she has MANY injuries from working out “too hard” over the past 15 years), the capitalization of “MANY” adds to the sense of intensity and consequence the writing conveys. Other typographic stylings, such as point size, use of underlining, and use of punctuation, including the exclamation mark, can also be used to focus attention and add to the discursive construction of certain news values.

Regarding color, designers often have more freedom with using color compared to photographers operating under traditional photojournalism ethics and can adjust the hue and saturation of images or introduce new colors entirely, which can influence the mood and reception of the resulting image. For example, Bednarek and Caple (Citation2014) suggest that using a black background to frame a story can reinforce or intensify the construction of newsworthiness.

Regarding layout, filling an entire newspaper page with an image is an uncommon occurrence and visually signals to the audience that the story is of outsized importance and deserves extra attention (Bednarek and Caple Citation2017). This treatment constructs superlativeness, impact, and potentially negativity, as well. In the digital space, filling a thumbnail completely with an image isn’t such a radical choice as it is on a printed page; however, choosing to leave an vertical mugshot uncropped in a 16 × 9 thumbnail frame or choosing to crop in and fill the frame with the person’s face is a decision that can impact the degree of personalization in the thumbnail and, likewise, the visual intimacy between the subject and the audience (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation1996). Juxtaposition, size, and placement are also other relevant aspects of layout that can discursively construct newsworthiness.

Bednarek and Caple (Citation2017) explore these semiotic resources through front-page newspaper design and our study extends the conversation into the digital age in the context of thumbnails. This study responds to the pair’s call to further investigate how these elements—beyond image composition and camera settings—can influence the construction of news values. This also responds to Bock’s (Citation2020) call to study image selection from the pool of images available to represent a certain subject, in this case, murder suspect Bryan Kohberger. As such, the study’s first research question is as follows:

RQ1A: Which visual source material do YouTube content creators select for video thumbnails related to the keyword “Bryan Kohberger” that were published on the platform in the days immediately following the arrest announcement (from Dec. 30, 2022, through Jan. 2, 2023)?

RQ1B:How do these results differ between accounts from (a) journalists and (b) non-journalists?

H1: Journalists and non-journalists will draw on different source material in equal proportions in the design of their thumbnails.

RQ2A: How multimodal are the YouTube thumbnails for videos matching the keyword “Bryan Kohberger” that were published from Dec. 30, 2022, through Jan. 2, 2023?

RQ2B: What is the level of fidelity between the visual source material and the YouTube thumbnails for videos matching the keyword “Bryan Kohberger” that were published from Dec. 30, 2022, through Jan. 2, 2023?

Method

We undertake in this study a qualitative semiotic analysis (as articulated by Caple, Huan, and Bednarek Citation2020; Bednarek and Caple Citation2017), which allows us to explore how visual source material, multimodality, and fidelity compare in the thumbnails related to the “Idaho 4 Killings” that were created by journalists and other content creators on YouTube. We also pair this with a quantitative content analysis that evaluates the distribution of visual source material used by journalists and non-journalists.

We selected YouTube as the site of this study because of its popularity in the USA and globally, its growing importance as a place where people turn to find information, and its unique affordances in contrast to other video-sharing social media platforms. Nearly two-thirds of all Americans are active on the platform and, globally, nearly one-third of the world’s population logs in at least once per month (Céci Citation2021). YouTube is also the world’s second-largest search engine, after Google, which attests to its importance in helping people find information about topics they perceive as relevant (Global Media Insight Citation2023). YouTube is also unique compared to other video-heavy social media platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok. Thumbnails play an outsized role in YouTube, where users have to click or tap to engage with a video and where thumbnails to other content are almost always included at the end of each video. This is different to Instagram’s default “feed” view and TikTok’s “for your page” view, where thumbnails are non-existent and users are shown auto-playing videos in the feed and queue, respectively. “Search” functionalities exist on both Instagram and TikTok but researchers have described them as “limited” (Vázquez-Herrero, Negreira-Rey, and López-García Citation2022, 1722) and noted that users don’t tend to use them as the primary way of engaging content on these platforms (Kang and Lou Citation2022).

Sample Timeframe and Inclusion Criteria

The sample includes the first four days (Dec. 30, 2022, through Jan. 2, 2023) after the suspect, Kohberger, was arrested and publicly identified. During these four days, journalists and other content creators had a relatively narrow range of images of Kohberger—fewer than one dozen—to use. These included the mugshot provided by police, a screen grab from his university webpage, and several images of him from various social media sites. The following day, Jan. 3, 2023, Kohberger made his first appearance in court, an event which was covered by journalists and others from outside the courthouse and by an Associated Press pool photographer from within the court. This was also the day law enforcement agencies released body cam footage of police interactions with Kohberger from several weeks prior as he drove from Washington to Pennsylvania to return to his family over the holidays. In short, on Jan. 3, 2023, and after, the number of images of Kohberger spiked sharply and provided journalists and content creators with markedly more options for visual variety. By focusing on the four days after the suspect was publicly identified but before other images of him emerged, we are able to assess how much visual variety existed in the sample and how this relatively narrow pool of options affected how others portrayed him. This is important as, over these four days, some channels in our sample, such as “Jonathan Lee Riches INVESTIGATES!” produced and uploaded 25 videos about Kohberger and the murders. This allows us to explore visual variety for accounts that are uploading multiple videos over a multi-day timeframe without new images of the suspect emerging.

This study examined all thumbnails on YouTube for the search term “Bryan Kohberger” published during this four-day period. Each video’s thumbnail is the unit of analysis. The search results revealed 515 videos and the thumbnails of these were downloaded. Each file was named with the value of the channel that uploaded it (e.g., “Fox 11 Los Angeles.png”) as well as a tag for whether the account was from a journalist or non-journalist account. To determine this, any logo or wordmark in the thumbnail (if present) was cross-referenced with the channel that uploaded the video to confirm its status. If no watermark or logo was present in the thumbnail, the channel’s “about” page was consulted and its status was determined based on the information presented here. After all thumbnails were downloaded and named, the study’s first author imported them into Adobe Bridge (a digital media manager) for viewing and later labeling.

Sample Characteristics

The bulk of the news accounts in the sample were commercial television stations that also posted clips or packages to YouTube. These included stations like WPVI, WLS, CNN, Fox 5 Atlanta, Fox 10 Phoenix, MSNBC, NBC 10 Philadelphia, WHAS, and WKYC. Two exceptions were the New York Post and Newsweek. To the best of our knowledge, only thumbnails from organizational news accounts (rather than the accounts of individual journalists) were present in the study. Only four of the news accounts were non-American. These included ABC News (Australia), Nine News Australia, Sky News Australia, and the Herald Sun. Regarding the non-journalist accounts, it’s not possible to systematically categorize these by location since YouTube doesn’t require users to list the location of their accounts and because not all of the accounts included in the sample in January 2023 are still accessible.

Data Coding and Analysis

Analysis was conducted in an inductive and deductive fashion (Creswell and Creswell Citation2018). The process started inductively by examining the thumbnails and noting any salient features, such as if source information (through logos or wordmarks) was included in the frame, if the visual was concrete (showing people or places related to the investigation) or generic (e.g., flashing police lights to denote a crime story), if the thumbnail included a single image or a multi-modal composition, and whether any overt editing had been done to the image (e.g., changing the color, adding in elements, etc.). These salient features were then noted in a codebook with accompanying definitions and the codebook was used to train the study’s coders and to conduct an inter-coder reliability test. Inter-coder reliability is usually calculated on a subset of the data pool and O’Connor and Joffe (Citation2020) suggest a subset of between 10 and 25 percent of the data pool is typical. Following this guideline, we opted for the higher end of this range and randomly assembled a subset of 25 percent of the thumbnails to use for the first inter-coder reliability test. Based on that first test the codebook was revised to clarify definitions of fidelity and coders reviewed their processes for accuracy. An additional category for fidelity was added to account for items in the sample that had no photographic element. The team coded a second (different and also randomly assembled) subsample and calculated intercoder reliability using Krippendorff's alpha, with modality measuring 0.88 and fidelity 0.78—both of which reflect high agreement (Hayes and Krippendorff Citation2007).

The codes were later collapsed into themes that each represented several codes (for example, themes originated for the alleged criminal, for the victims, for the channel owner or journalist, and for the potentially subjective categories such as modality and fidelity that encompassed sub-codes such as mono- or multi-modal and low-, medium-, and high-fidelity). Following this, the thumbnails were examined deductively through the lens of visual news values to provide a sense of which salient aspects journalists and non-journalists were drawing on in their image selection and thumbnail design decisions. In this way, both predetermined and emerging codes were used in the analysis process.

Lastly, we conducted a chi-square goodness of fit test with multiple categories to evaluate the use of visual source material between the journalist and non-journalist accounts.

Sample Distribution

Just under 100 (n = 97, or 18.83%) of the 515 videos published during the sample’s time frame were created by news outlets. Even though the number of news outlet-produced videos for this story was lower, they tended to enjoy higher viewer counts (often in the realm of six or seven figures compared to non-journalist accounts, which tended to accrue four- or five-figure viewer counts). Because of the difference in the number of journalist and non-journalist videos, the percent within their own category (rather than percent of the entire sample) has been provided below in the second half of RQ1 to provide a comparable sense of which visual sources both types of accounts drew upon.

Findings

RQ1A explored the visual source material journalists and other content creators used in YouTube thumbnails about the “Idaho4Murders” in the first four days after Bryan Kohberger was publicly identified as the crime’s suspect.

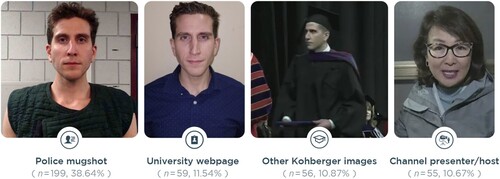

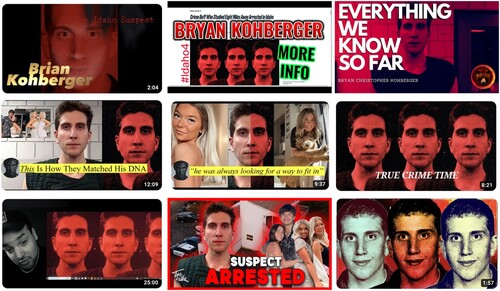

The most popular visual source during this timeframe was the police mugshot of Kohberger. This photo was used more than three times as often as any other image and occupied about 40 percent (n = 199, 38.64%) of the sample. The second and third most-popular visual sources also featured Kohberger and did so by using his university webpage photo (n = 59, 11.54%) or other images of him (n = 56, 10.87%) such as from his high school yearbook, from his university commencement ceremony broadcast, or from social media. Altogether, images of Kohberger were found in a majority (65.96%) of the thumbnails during this four-day period. See for a visual overview of these most-popular visual sources.

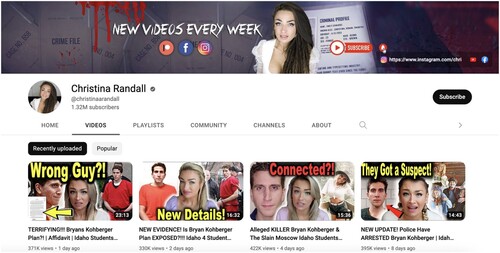

In fourth place as the most-popular visual source were images of the host/presenter of the content, such as a journalist or a YouTube channel owner. These images occupied 10.67 percent of the sample. Rounding out the visual sources featured in the thumbnails were photos of the murder victims (n = 43, 8.34%); screenshots of online webpages and social media conversations (n = 29, 5.63%); multiple photos of Kohberger (such as juxtaposing images of him in his commencement robes with his mugshot photo) (n = 26, 5%); photos of law enforcement (n = 23, 4.46%); photos of the natural or built environment, such as the house where the murders happened, the apartment where Kohberger lived, or the escape vehicle, or relevant objects, such as photos of flowers at a memorial tribute (n = 16, 3.1%); and images of an other or unknown source, such as a channel logo or stock photo background. Please see for a tabular overview of the visual source material featured in these YouTube thumbnails.

Table 1. Visual source material featured in the YouTube thumbnails.

Differences Between Journalists and Non-Journalists

RQ1B asked how the visual source material choices used in these YouTube thumbnails differed between journalist and non-journalist accounts. As presented in , there were significant differences in visual practices for some of the images. Overall, the null hypothesis can be rejected, as journalists and non-journalists used the various source types differently, χ2(2, n = 515) = 74.25, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .380.

Table 2. Visual source material by publisher type.

We also measured the use by journalists and non-journalists of individual source types. Journalists used Kohberger’s mug shot more often than non-journalists, χ2 = 73.57, p < .001. Non-journalists were more likely to use the university website photo of Kohberger, χ2(2) = 40.69, p < .001.

Journalist and non-journalist accounts also used other images of Kohberger (such as those from social media, from his commencement ceremony broadcast, from his high school yearbook, etc.) in significantly different proportions. Journalist accounts used these images in only 12.5 percent of cases while non-journalist accounts used them much more frequently, in 87.5% of cases, χ2(2) = 31.5, p < .001. Journalists and non-journalists used images of the content’s host/presenter of the content differently, 7.27% for journalist accounts and 92.72% for non-journalist accounts, χ2(2) = 40.16,p < .001. Differences in practice were dramatic for the use of screenshots, χ2(2) = 29, p < .001 and multiple images of Kohberger, χ2(2) = 26, p < .001.

Other source types were used in different proportions but not to a statistically significant level. These include images of the murder victims, images of law enforcement, the natural or built environment and other.

Thumbnail Multi-modality

The first half of the second research question explored the question: “How multimodal are the YouTube thumbnails for videos matching the keyword “Bryan Kohberger” that were published from Dec. 30, 2022, through 2 Jan. 2, 2023?” Overall, the sample was highly multi-modal, defined here as the fusion of multiple communication forms (e.g., the addition of text or other symbols, such as emoji, over photos or other images). More than two-thirds of the sample (n = 348, 67.57%) featured the juxtaposition of images with text or other symbols to establish additional context. The most common form of multi-modal thumbnail was an image-text composition where the text was used to label the content (e.g., “**LIVE PRESSER**”; “EXCLUSIVE”; and “KILLER”); pose a question (e.g., “What’s Bryan’s motive?”, “The Boogeyman Stalked Victims for Weeks??”, and “Bryan Kohberger’s public defender believes he is innocent!?”); identify the theme or focus of the clip (e.g., “Psychiatrist Theories”, “How he knew them!”, and “A look at Bryan Kohberger’s apartment!!”); and/or establish branding, by the addition of a wordmark or logo. By type of account, journalist accounts included proportionately fewer multi-modal thumbnails on their videos related to the murder suspect. Fewer than half of the journalist accounts’ thumbnails (n = 47, 48.45%) contained multimodal compositions. In contrast, More than two-thirds of the non-journalist accounts (n = 301, 72%) used multi-modal compositions in their video thumbnails. See for a visual overview of these most-common types of multimodal thumbnails.

Even when journalist accounts used multi-modal thumbnails, they tended to employ more conservative and neutral semiotic elements when doing so. In contrast, non-journalist accounts drew on tabloid-style graphic treatments with arousing colors, large font point sizes, emphatic punctuation, and provocative questions. On the whole, journalist accounts used calmer colors and more neutral typefaces to visually present a more neutral introduction to the story (see ).

Figure 5. Journalist accounts were more conservative with their typography and color palettes in their thumbnails compared to non-journalist accounts.

The mono-modal compositions (n = 166) were also evaluated to parse their complexity. Almost exactly half (n = 82, 49.39%) of the mono-modal compositions contained only a single image. Webcam and broadcast footage, as well as horizontal photos, largely suited the thumbnails’ 16:9 aspect ratio well. In the case of vertical photos and screenshots from mobile devices, content creators either cropped these vertical images to suit the horizontal aspect ratio of the thumbnail (which resulted in sometimes uncomfortably close framing where just the suspect’s eyes and lips are visible) or left them in their vertical orientation with black bars on either side of the composition.

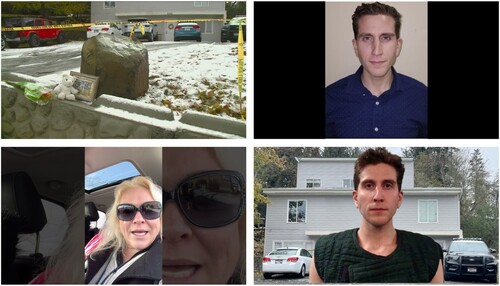

The other 84 thumbnails (50.60%) were mono-modal but included multiple images. Almost three-quarters of these (n = 62, 73.81%) included two images. Roughly half of these were vertical images that were duplicated and enlarged as a second, darkened layer behind the first to fill the 16:9 aspect ratio. The other half of these images juxtaposed people or people and places together. For example, some thumbnails inserted the police mugshot of the suspect over a photo of the residence where the murder took place. In other thumbnails, the creator juxtaposed the murder suspect in the same frame as the victims. The remaining 22 thumbnails featured three or more images. See for a visual overview of these mono-modal thumbnail compositions.

Thumbnail Fidelity

The second half of the second and final research question explored the level of fidelity between the visual source material and the YouTube thumbnails for videos matching the keyword “Bryan Kohberger” that were published from Dec. 30, 2022, through Jan. 2, 2023.

51 thumbnails included visual source materials that were of low or medium fidelity. (Thirty-six were of medium fidelity and 15 were of low fidelity.) All but two used visual source material portraying Kohberger. Thus, of the 340 thumbnails that included images of Kohberger, 51 (15 percent) of these images were of low or medium fidelity. Journalist accounts were responsible for two of the 36 medium-fidelity images (5.5%). In one instance, Australian-based ABC news blurred the background of Kohberger’s police mugshot while in the other, a U.S.-based NBC New York television channel converted Kohberger’s police mugshot to grayscale and added a halftone texture to it. (See ).

The non-journalist accounts’ thumbnails were more dramatic with their color transformations and many of them combined Kohberger’s image with a red overlay (see ). They also sometimes darkened his mugshot photo to make him look more sinister. No journalist accounts were responsible for any of the low-fidelity visual source material used in the sample’s thumbnails. These low-fidelity images overlaid blood and weapons over images of Kohberger, added devil horns to his image, and overlaid a semi-transparent photo of Ted Bundy over Kohberger’s image (see ).

Overall, while journalists and non-journalists sometimes drew on the same imagery (i.e., the police mugshot) in equal proportions, these two groups also used strikingly different imagery (e.g., the photo of Kohberger from his university webpage) and made markedly different design choices (related to multimodality and fidelity) in the thumbnails that accompanied their videos related to the “Idaho 4 murder” suspect published during the study’s timeframe. The news values and specific semiotic resources that journalists and non-journalists alike drew on will be unpacked and discussed next, and will include a discussion of implications for scholars and journalists alike.

Discussion

This study provided an in-depth glimpse into how journalists and non-journalists construct and design thumbnails related to a newsworthy, crime-related topic, the “Idaho 4 Killings” during a unique period where the pool of visual source material was limited. In support of previous literature (Shimono, Kakui, and Yamasaki Citation2020) that found that human faces in thumbnails were a key aspect of audience engagement, more than 90 percent of the thumbnails in the sample featured human faces. This demonstrates that both journalists and non-journalists were drawing on the personalization news value in the image selection and design of their thumbnails and using it to provide a human face to the issue. However, journalists and non-journalists made markedly different choices about which face to show (and how). Journalist accounts featured images of the alleged criminal in just about half (52.5%) of their thumbnails. In contrast, non-journalist accounts featured the alleged criminal more frequently (in 69.1% of cases).

Journalist accounts focused on other relevant parties, such as the victims, more than 2.5 times as often as did non-journalists. Thus, personalization, in concert with impact—through showing the victims as the ultimate consequence of the stabbings—can be seen in the journalists’ thumbnail designs. Conversely, the personalization news value in concert with the unexpectedness one are reflected in non-journalists’ thumbnail designs. This is evidenced by the starkly different approach to using Kohberger’s university web page photo (91.52% compared to 8.47%), other photos of Kohberger from social media or other sources, such as his commencement ceremony (87.5% compared to 12.5%), and using multiple photos of him from different periods in his life (such as juxtaposing his sophomore high school yearbook photo with the more recent photo of Kohberger from his university webpage). The prolific use of self-sourced images by non-journalists suggests they are more comfortable with (or unaware of) the legal and ethical risks of using an image that appeared to be but might not have actually been the alleged criminal. The risk was even higher for thumbnails that implied guilt through the use of multimodal elements such as color or additional text.

Non-journalists’ heavy use of images of the alleged criminal beyond his police mugshot also illustrate their desire to achieve visual variety with their thumbnails (recalling that some channels produced as many as two dozen or more videos on this topic during the sample’s four-day timeframe) and to amplify and visually underscore the unusual nature (drawing again on the unexpectedness news value) of a highly educated person being capable of committing such a gruesome and unexpected crime in a small town of 25,000 that hadn’t seen a murder in seven years. Likewise, using less conventional imagery (screenshots of documents or social media chats or profiles) was an approach adopted exclusively by non-journalists and was likely a result of less visual literacy, a need for more visual variety given the higher frequency of videos created by YouTubers during this period, and/or conventions that are unique to a younger and born-digital cohort of content creators.

Generic images as thumbnails were used infrequently (only n = 6 in the entire sample) and generic images in multimodal compositions were also rare. Objects, such as generic knives or weapons, were added to a handful of thumbnails (as police said the murder weapon was a knife but it hadn’t been located as at November 2023 and no photos of it are publicly known to exist). In only a single instance was a generic photo of a person used (to represent the suspect) and even then, it was accompanied by real-life photos of law enforcement and the victims. This speaks to the importance of the proximity news value for journalists and non-journalists alike. Generically representing the video through a generic thumbnail that identifies the channel only or suggests a crime or courts topic (see ) is much less specific and concrete (and thus less emotionally engaging and resonant) than photos of the specific community and people potentially involved in the murders and subsequent investigation.

Journalists and non-journalists alike used few generic images in their thumbnails. Only one image (bottom-left) used a generic image to represent a person and, when it did, it accompanied this with non-generic images of the victims and law enforcement related to this particular crime.

Some non-journalists, such as Florida-based Andra Griffin (known online as “Bullhorn Betty”), traveled to the scene of the crime and made videos on-site there and at surrounding locations (such as the nearby Washington State University where the alleged criminal had an office) to boost the proximity value of their content. However, through the affordances of thumbnail design, other YouTubers who weren’t there physically were able to insert themselves into the scene and place themselves adjacent to the suspect and the victims in an effort to discursively boost the apparent proximity and relevance of themselves and their content. This is the case for Florida-based YouTuber Christina Randall, who consistently features her own face—often with an emotive expression—in each of the thumbnails she uploads (see ). In many cases, these YouTubers have a commercial incentive to do so (through payments directly from YouTube or through merchandise available on a YouTube store, such as https://www.youtube.com/@BULLHORNBETTY/store, or third-party online store, such as https://bullhorn-betty.creator-spring.com/).

Journalists featured themselves sparingly (in only 7.28 percent of cases) in the thumbnails they used for this topic, which indicates a different motivation for their storytelling in contrast to the motivation of other YouTubers where a desire for recognition can be a prime motivator (Young & Wiedenfeld, Citation2022).

In terms of aesthetic choices that are reflected in the multi-modal thumbnails in the sample, journalist accounts drew on the consonance news value by visually reinforcing (through typographic choices and color palettes) the “innocent until proven guilty” status that suspects are supposed to enjoy in the U.S.A. In contrast, non-journalist accounts drew on the negativity news value to discursively (through color choices, the addition of symbols, and through the use of question marks) cast doubt on the suspect’s innocence. This is evidence of using social media conventions to garner attention (Shimono, Kakui, and Yamasaki Citation2020) but also of engaging in tabloid-style sensationalist treatment of the thumbnail in the hopes of inspiring video views (and the possibility for revenue that such views bring, recalling that YouTubers are often motivated, in part, by a desire to make money [Buf and Ștefăniță Citation2020]).

Conclusion

YouTube thumbnails provide a compelling reason to rethink how journalists and non-journalists visually represent their news to audiences. For many news outlets in Western countries with their own websites or apps, the default thumbnail is a simple photo (see ) which, while more engaging than no image at all, is sometimes an afterthought and serves as a visual illustration of the linked story.

In this sample of YouTube video thumbnails, however, the vast majority (83.49 percent) of the thumbnails were compositions (67.57 percent multi-modal and 16.31 percent mono-modal) that had been designed rather than single images that had been simply selected and used as is.

Care and attention is often evident in the images trained visual journalists make but what if newsrooms treated the design of these visuals with the same care and attention that headlines and the body copy receive? Additional context can be easily added or removed when thumbnails are treated as designs rather than as containers for single images. This contextual treatment can either benefit audiences (in the case of helping them differentiate between multiple sources of information) or harm them (in the case of mis/disinformation and sensationalism). For news to serve the public, creators must consider the visual source material, the multimodal relationships with other communication forms (along with aesthetic decisions made about these multimodal elements), and the designed thumbnails’ fidelity to original source material. Journalist and non-journalist accounts might also consider the fairness of embedding a person’s image into a thumbnail design that connotes guilt before trial, when the U.S. legal system declares them to be “innocent until proven guilty.”

This study makes a contribution to the visual presentation of crime-related news in the way it examines images in context and considers contexts beyond a traditional printed or online news page. It is unique in how it evaluates thumbnails as the “visual gateway” for a story on YouTube and for its study of multimodal cues in the online environment, where an increasingly large number of people are turning to for news (Pew Research Center Citation2022).

Lastly, this study extends our understanding of the various semiotic resources and visual elements (e.g., colors, typefaces, juxtapositions, and punctuation practices) that link with specific news values, such as proximity and negativity. In doing so, this study responds to Bednarek and Caple’s (Citation2017) call to explore how semiotic elements beyond image composition and camera settings can influence the construction of news values. Likewise, by studying news values like personalization in a nuanced way that extends beyond just examining human presence (and instead examines which human presence is privileged and how), this study shines light on how the same news value can manifest itself differently in thumbnail designs given their creators’ divergent motivations, audiences, and purposes.

Limitations

A strength of this study’s approach is that it adopted a corpus-based sampling strategy and in doing so, ensured that all results were analyzed and not just the most recent, highly viewed, or geographically near. However, at the same time, the benefit of the corpus-based sampling strategy is also a limitation as the sample size needs to be relatively small to enable a manual and deep examination. This four-day period provided this although it does not allow a comprehensive examination of how the “Idaho 4” murder suspect continues to be represented on YouTube thumbnails in the weeks and months following his arrest and public identification. Despite this, the study is able to offer a compelling look at how visual source material, multimodality, and visual fidelity operate in thumbnails created by journalists and non-journalists on YouTube.

Another limitation of this study is that as a content analysis, it is unable to directly observe the creators at work. The thumbnails offer clues regarding creator motivations, but these cannot be validated without further research involving interviews or ethnographic observation.

Future Directions

Future studies focused on thumbnails with different topics (e.g., stories about the environment rather than crime news) would be welcome and would allow for an understanding of if or how news values differ based on story topic. Additional attention can and should be paid to the aesthetic decisions (such as the shot size and its relationship to visual intimacy) reflected in the multi-modal thumbnails created by journalists and news organizations. This study mentioned these aspects in a cursory fashion only but a study that centers them would make a valuable contribution to the field. Despite the logistical difficulties, studies that are able to pair content analysis with insights from the channel owners would also be welcome.

The aspects of thumbnail and link preview image design are doubtless set to grow in importance in the coming months and years and are an important though overlooked aspect for many journalists and news organizations. Scholars would do well to interview these stakeholders about their thumbnail design practices and how they compare across platforms (e.g., on the news outlet’s website, on its app, and on third-party social media sites and news aggregators). Images are often the reason a person clicks or taps on a story or video, so insight regarding their design, use, and ethics is essential for researchers and practitioners who care about the public interest.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmad, P. M., I. Hikami, B. N. F. Zufar, and A. Syahfrullah. 2022. “Digital Labour: Digital Capitalism and the Alienation of YouTube Content Creators.” Journal of Asian Social Science Research 3 (2): 167–184. https://doi.org/10.15575/jassr.v3i2.44.

- Associated Press Stylebook. n.d. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.apstylebook.com/ap_stylebook/accused-alleged-suspected.

- Bednarek, M., and H. Caple. 2014. “Why do News Values Matter? Towards a New Methodological Framework for Analyzing News Discourse in Critical Discourse Analysis and Beyond.” Discourse & Society 25 (2): 135–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926513516041.

- Bednarek, M., and H. Caple. 2017. The Discourse of News Values: How News Organizations Create Newsworthiness. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Blakinger, K. 2020, February 2. Newsrooms Rethink a Crime Reporting Staple: The Mugshot. The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/02/11/newsrooms-rethink-a-crime-reporting-staple-the-mugshot.

- Bock, M. A. 2020. “Theorising Visual Framing: Contingency, Materiality and Ideology.” Visual Studies 35 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2020.1715244.

- Brown, M. 2019, May 23. Why we Shut Down the “Mugshots” page. WTXL. https://www.wtxl.com/news/local-news/why-we-shut-down-the-mugshots-page.

- Brumberger, E. R. 2003. “The Rhetoric of Typography: The Persona of Typeface and Text.” Technical Communication 50 (2): 206–223.

- Buf, D. M., and O. Ștefăniță. 2020. “Uses and Gratifications of YouTube: A Comparative Analysis of Users and Content Creators.” Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations 22 (2): 75–89. https://doi.org/10.21018/rjcpr.2020.2.301.

- Caple, H., C. Huan, and M. Bednarek. 2020. Multimodal News Analysis Across Cultures. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Céci, L. 2021. YouTube Viewers in the United States 2018-2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/469152/number-youtube-viewers-united-states/.

- Chermak, S. 1995. “Image Control: How Police Affect the Presentation of Crime News.” American Journal of Police 14 (2): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/07358549510102730.

- Chermak, S., and A. Weiss. 2005. “Maintaining Legitimacy Using External Communication Strategies: An Analysis of Police-Media Relations.” Journal of Criminal Justice 33 (5): 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2005.06.001.

- Christin, A. 2020. Metrics at Work: Journalism and the Contested Meaning of Algorithms. Princeton, U.S.A.: Princeton University Press.

- Coleman, R., J. Y. Lee, C. Yaschur, A. P. Meader, and K. McElroy. 2018. “Why be a Journalist? US Students’ Motivations and Role Conceptions in the new age of Journalism.” Journalism 19 (6): 800–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916683554.

- Creswell, J. W., and J. D. Creswell. 2018. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

- Einstein, M. 2016. Black Ops Advertising: Native Ads, Content Marketing, and the Covert World of the Digital Sell. New York, NY: OR Books.

- Ellenbogen, J. 2012. Reasoned and Unreasoned Images: The Photography of Bertillon, Galton, and Marey. University Park, U.S.A.: Penn State Press.

- Elliott, D. 2011, November 23. The Newest Magazine Fad: The Mug Shot Tabloid. NPR.Org. http://www.npr.org/2011/11/23/142701001/the-newest-magazine-fad-the-mug-shot-tabloid.

- Ferrucci, P., and R. Taylor. 2019. “Blurred Boundaries: Toning Ethics in News Routines.” Journalism Studies 20 (15): 2167–2181. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1577165.

- Finn, J. M. 2009. Capturing the Criminal Image: From Mug Shot to Surveillance Society. Minneapolis, U.S.A.: University of Minnesota Press.

- Fisher, C., T. Flew, S. Park, J. Y. Lee, and U. Dulleck. 2021. “Improving Trust in News: Audience Solutions.” Journalism Practice 15 (10): 1497–1515. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1787859.

- Gandy Jr., O. H. 1982. Beyond Agenda Setting: Information Subsidies and Public Policy. New York, U.S.A.: Ablex.

- Global Media Insight. 2023. YouTub User Statistics 2023. Global Media Insight. https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/youtube-users-statistics/.

- Greussing, E., and H. G. Boomgaarden. 2019. “Simply Bells and Whistles? Cognitive Effects of Visual Aesthetics in Digital Longforms.” Digital Journalism 7 (2): 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1488598.

- Hall, R. 2009. Wanted: The Outlaw in American Visual Culture. Charlottesville, U.S.A.: University of Virginia Press.

- Hayes, A. F., and K. Krippendorff. 2007. “Answering the Call for a Standard Reliability Measure for Coding Data.” Communication Methods and Measures 1 (1): 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664.

- Jewitt, Carey. 2009. “An Introduction to Multimodality.” In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, edited by Carey Jewitt, 14–27. London/New York: Routledge.

- Kang, H., and C. Lou. 2022. “AI Agency vs. Human Agency: Understanding Human–AI Interactions on TikTok and Their Implications for User Engagement.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 27 (5): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac014.

- Kaniss, P. 1991. Making Local News. Chicago, U.S.A.: University of Chicago Press.

- Kim, H., J. Kim, Y. Han, H. Hong, O. S. Kwon, Y. W. Park, … B. C. Kwon. 2023. “Towards Visualization Thumbnail Designs That Entice Reading Data-Driven Articles.” IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 1–16. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2305.17051.

- Kleemans, M., P. G. J. Hendriks Vettehen, J. W. J. Beenties, and R. Eisinga. 2017. “The Influence of Sensationalist Features in Television News Stories on Perceived News Quality and Perceived Sensationalism of Viewers in Different age Groups.” Studies in Communication Sciences 2: 183–194.

- Kress, G. R., and T. Van Leeuwen. 1996. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London, UK: Psychology Press.

- Lamot, K. 2022. “What the Metrics say. The Softening of News on the Facebook Pages of Mainstream Media Outlets.” Digital Journalism 10 (4): 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2013.827358.

- Lester, P., S. Martin, and M. Smith-Rodden. 2022. Visual Ethics: A Guide for Photographers, Journalists, and Media Makers. New York: Routledge.

- Moscow Police Department. 2022. Moscow Homicide Update https://www.ci.moscow.id.us/DocumentCenter/View/24812/12-02-22-Moscow-Homicide-Update?bidId = .

- Moyo, D., A. Mare, and T. Matsilele. 2020. “Analytics-Driven Journalism: Editorial Metrics and the Reconfiguration of Online News Production Practices in African Newsrooms.” In Measurable Journalism, edited by Matt Carlson, 104–120. London, U.K.: Routledge.

- Munyaka, I., E. Hargittai, and E. Redmiles. 2022. “The Misinformation Paradox: Older Adults are Cynical About News Media, but Engage with It Anyway.” Journal of Online Trust and Safety 1 (4): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v1i4.62.

- National Press Photographers Association. 2023. Code of Ethics. https://nppa.org/resources/code-ethics.

- Newman, N., and R. Fletcher. 2017. “Bias, Bullshit and Lies: Audience Perspectives on Low Trust in the Media.” Available at SSRN 3173579.

- O’Connor, C., and H. Joffe. 2020. “Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220.

- Osipov, V. S. 2020. “Yellow Brick Road to Digital State.” Digital Law Journal 1 (2): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.38044/2686-9136-2020-1-2-28-40.

- Pew Research Center. 2022. Social Media and News Fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/.

- Reiss, A. J. 1971. The Police and the Public. New Haven, U.S.A.: Yale University Press.

- Sekula, A. 1986. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39: 3–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/778312.

- Sharp, R. 2022. “Idaho Police Blame Online Reddit Sleuths For Creating ‘Huge Distraction’ From College Murder Case.” The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/crime/idaho-college-murders-crime-scene-reddit-b2244342.html.

- Shimono, A., Y. Kakui, and T. Yamasaki. 2020, June. “Automatic YouTube-Thumbnail Generation and its Evaluation.” In Proceedings of the 2020 Joint Workshop on Multimedia Artworks Analysis and Attractiveness Computing in Multimedia, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3379173.3393711

- Society for News Design. 2023. Code of Ethics. https://snd.org/about-us/our-mission-and-code-of-ethics/

- Sun, R., N. Bogel-Burroughs, and S. F. Kovaleski. 2022. Criminology Student is Charged in 4 University of Idaho Killings. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/30/us/idaho-murders-suspect-bryan-kohberger.html.

- Thomson, T. J., D. Angus, P. Dootson, E. Hurcombe, and A. Smith. 2022. “Visual Mis/Disinformation in Journalism and Public Communications: Current Verification Practices, Challenges, and Future Opportunities.” Journalism Practice 16 (5): 938–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1832139.

- Vázquez-Herrero, J., M. C. Negreira-Rey, and X. López-García. 2022. “Let’s Dance the News! How the News Media are Adapting to the Logic of TikTok.” Journalism 23 (8): 1717–1735. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920969092.

- Vitadhani, A., K. Ramli, and P. D. Purnamasari. 2021. Detection of Clickbait Thumbnails on YouTube Using Tesseract-OCR, Face Recognition, and Text Alteration. In 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Technology (ICAICST), (pp. 56-61). IEEE.

- Watkins, J., S. Park, C. Fisher, W. Blood, G. Fuller, V. Haussegger, M. Jensen, J. Y. Lee, and F. Papandrea. 2017. Digital News Report Australia. Canberra, Australia: News & Media Research Centre, University of Canberra.

- Weismueller, J., and P. Harrigan. 2021, June. “Organic Reach on YouTube: What Makes People Click on Videos from Social Media Influencers?” In Digital Marketing & ECommerce Conference, edited by Francisco J. Martínez-López and David López López, 153–160. Cham: Springer.

- Wong, M. 2019. A Social Semiotic Approach to Text and Image in Print and Digital Media. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Young, A., and G. Wiedenfeld. 2022. “A Motivation Analysis of Video Game Microstreamers:“Finding My People and Myself” on YouTube and Twitch.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 66 (2): 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2022.2086549.