ABSTRACT

Over the years, studies have assessed the quality of discourse in comment sections and results have been mixed. Some argue that newspapers have created forums for hate speech against minorities, that the quality of discourse undermines the democratic potential of comment sections, or that comments are troubled by incivility. Others have found that commenters produce content resembling public deliberation and that comment sections can contain fruitful discussions on divisive topics. This article contributes to the literature on the deliberative quality of news comments by assessing the deliberative quality of news comments in Finland. What is the deliberative quality of comments on Svenska Yle’s news articles? We conduct a quantitative content analysis of 565 news comments to 30 articles on Svenska Yle. Using a novel measurement strategy derived and developed from earlier research on assessments of deliberative quality, we analyze the deliberativeness, emotiveness, and confrontativeness of comments. Our findings are relatively positive since the overall quality level exceeds that of several previous studies. However, several indicators of quality still need improvement.

Introduction

A typical trait of online communication is the contrast between user-generated online comments and gatekeeper-provided news content produced by journalists (Lee, Atkinson, and Sung Citation2022). Since their introduction in the late 1990s (Santana Citation2011), news comments have offered a wider range of views compared to letters to the editor, possibly due to lower thresholds for commenting (McCluskey and Hmielowski Citation2012). Over time, news comments have become an integral part of online journalism (Beckert and Ziegele Citation2020, 3924), although problems such as incivility in comment sections have resulted in some news organizations abandoning comment sections entirely (Chen Citation2017). Either way, user-generated content (e.g., comment sections) is a central feature in the digital era and illustrates the changing role of public service broadcasting (PBS) organizations (Sjøvaag, Moe, and Stavelin Citation2012). The emergence of a hybrid media system is accompanied by increased public communication online and a decreased influence for journalistic and political elites (Pfetsch Citation2020).

In theory, digital public discourse in the form of news comments represents an ideal public sphere (McDermott Citation2016, 16). News comments have higher visibility compared to comments on independent forums and their unrestricted and immediate character seems to suit informal, non-hierarchical ways to participate in public dialogue (Zimmermann Citation2014, 100). News comments provide news organization with free user-generated content, which the audience comes to read. Comments offer citizens the ability to debate, discuss and provide views not present in the original article (Eisinger Citation2011, 4). High-quality discussion in comment sections might increase citizens’ understanding of political issues and thus alleviate ideological and affective polarization (Oswald Citation2022, X). The quality of news comments is important since news organizations want to host valuable exchanges of ideas while being seen as credible sources of information among the public (Diakopoulos and Naaman Citation2011, 133).

Yet, in practice, comment sections have often failed to live up to the ideals of a public sphere. Studies have found that comments are non-dialogical in nature (Parra, Ayerdi, and Fernández Citation2020), contain incivility (Chen Citation2017; Coe, Kenski, and Rains Citation2014), and demonstrate a low deliberative quality (Zimmermann Citation2014). Low-quality discussion causes several problems. Firstly, comment sections require moderation and response from news organizations, which takes up resources (Ihlebæk and Ytreberg Citation2009). Moderation expands the journalistic role and adds to journalists’ workload (Goodman and Cherubini Citation2013), while journalists often receive little training in moderation (Chen Citation2017). Secondly, low-quality comment sections might damage news organizations’ brands (Singer and Ashman Citation2009) or lower their credibility (Conlin and Roberts Citation2016). Thirdly, uncivil discussion recoil people from news sites (Diakopoulos and Naaman Citation2011; Springer, Engelmann, and Pfaffinger Citation2015).

Given the problems with the quality of news comments, it is unsurprising that news organizations are still experimenting with these. News outlets have tested various measures to improve the dialogue in the comment sections (Ksiazek Citation2015, Citation2018). For example, interactive moderation by journalists (Ziegele et al. Citation2018) and engagement moderation (Masullo, Riedl, and Huang Citation2022) have shown promising results. It seems likely that the experience news organizations have gathered over time should improve the quality of discourse. Research on the quality of comments has produced mixed results. Some argue that newspapers occasionally have created forums for hate speech against minorities (Santana Citation2012), that the quality of discourse undermines the democratic potential of comment sections (Nagar Citation2011, 147) or that comments are troubled by incivility (Coe, Kenski, and Rains Citation2014). Others have found that commenters produce content that resembles public deliberation (Manosevitch and Walker Citation2009) and that comment sections can contain fruitful discussions even on divisive topics (Friedman Citation2011).

This article contributes to the literature on the deliberative quality of news comments. To improve the discourse quality, scholars need to determine the baseline before any attempt to introduce a design feature for improving it. However, it is unknown how effective current strategies for eliminating dark participation, defined as “comments that transgress norms of politeness or honesty with partially sinister motives”, are (Frischlich, Boberg, and Quandt Citation2019, 2014). To assess the deliberative quality of online news comments in Finland, this article addresses the following research question: What is the deliberative quality of comments on Svenska Yle’s news articles?

To answer this question, we conduct a quantitative content analysis of 565 news comments to 30 news articles on Svenska Yle. We argue that Svenska Yle is a case of a national public-service broadcaster struggling with how to handle user-generated content. For example, Svenska Yle receives around 170,000 comments in a year, and these are moderated by reporters in addition to their ordinary journalistic work (Jungar Citation2018). Moreover, commenters constantly criticize the moderation (Jungar Citation2017). Public service media (PSM) are particularly interesting to study due to their perceived role as upholders of a forum for debate akin to part of a public sphere (see Fuchs Citation2014; Garnham Citation1990, 111), a role that has become accentuated in the digital era when PSM, ideally, take on a role as Public Service Internet (e.g., Fuchs Citation2014; Fuchs and Unterberger Citation2021). Employing a novel measurement strategy derived and developed from assessments of deliberative quality, we analyze the deliberativeness, emotiveness, and confrontativeness of comments.

Background and Theory

Comment Sections in News Outlets

News comments are a form of user-generated content in conjunction with online news articles (Santana Citation2011). Comment sections are relatively popular, many news organizations host these and people both post and read comments (Santana and Hopp Citation2022, 2). News comments are one of the most widespread types of user-generated content (Naab and Küchler Citation2022, 441). News comments are polylogues since they involve multiple levels of dialogue; between journalists/editors and the public as well as between the readers (Kolhaktar et al. Citation2020). Thus, comments can be both reactive and interactive (Ziegele et al. Citation2020, 865). In a historical perspective, news comments add a new dimension to traditional reporting and news readership as they offer readers a direct voice (von Sikorski and Hänelt Citation2016, 2).

News comments have many negative connotations. The mere presence of a comment section can lower the perceived quality of an article (Prochazka, Weber, and Schweiger Citation2018) or lower the credibility of news sites (Conlin and Roberts Citation2016). Journalists tend to dislike comments (Santana Citation2011) and regard them as abusive and of low quality (Mitchelstein Citation2011). Uncivil commenting concerns journalists, as they need direction on how to control commenting through engagement and moderation (Masullo Chen and Lu Citation2017). Nielsen (Citation2012), however, argues that journalists can accept comment sections as long as they are not unmoderated spaces free-for-all. Journalists struggle to find balance between moderating comments for problematic behavior while maintaining an open discussion (Wolfgang Citation2018). A study on comment moderation strategies (Boberg et al. Citation2018) found that the moderator’s moral compass shape moderation rather than a set standard for gatekeeping. Wolfgang, McConnell, and Blackburn (Citation2020, 941) conclude that news organizations need to allocate more resources to comment moderation instead of opening up comment sections without the possibility to manage these or outsourcing the discourse to social media platforms. Moreover, Wolfgang, McConnell, and Blackburn (Citation2020) argue that journalism education and training should build better relationships with the audience by focusing more on audience engagement.

News comments can have a systematic influence on online journalism by affecting recipients’ processing of news (von Sikorski and Hänelt Citation2016). For example, comments function as peer influence (Chung Citation2019). Studies have found that comments have effects on readers’ opinions (Lee and Jang Citation2010; Rösner and Krämer Citation2016), although others (e.g., Steinfeld, Samuel-Azran, and Lev-On Citation2016) have found the opposite. Moreover, hateful or negative comments can lead to less charitable behavior (Weber et al. Citation2020). Masullo Chen and Lu (Citation2017) found that disagreement in comments tended to have a chilling effect on public discourse. Although news comments are not representative of public opinion (Newman et al. Citation2017), they are used to assess the public debate (Naab and Küchler Citation2022, 442).

Why should news outlets aim to raise the quality of comments? Engelke (Citation2020) shows that media users value and recognize deliberative elements and argues that news comments of deliberative nature are a reason for participation and positive evaluations. Other studies have indicated that raising the quality of comments might encourage users that otherwise stay silent to participate (Springer, Engelmann, and Pfaffinger Citation2015). Or, as Oswald (Citation2022, 1) argues, high-quality comment sections can help users to understand issues and help to alleviate mechanisms of opinion polarization. Moreover, as comments have been found to influence peoples’ opinions (e.g., von Sikorski and Hänelt Citation2016; Ziegele et al. Citation2018) and behavior (e.g., Weber et al. Citation2020), high-quality comments might be contagious (Wolfgang and Bhandari Citation2020).

The (Deliberative) Quality of News Comments

During the last 15 years, scholars have discussed, analyzed, praised, and criticized comment sections (Ksiazek and Springer Citation2018). Criticism has sometimes led to comment sections being taken down altogether by news outlets such as Reuters and Bloomberg (Quandt Citation2018, 37). Ksiazek and Springer (Citation2018, 482) argue that the quality of comment sections is the most pressing issue and see two solutions: news organizations either take ownership of comment sections or shut them down. Furthermore, they suggest, news organizations introduced comment sections to generate revenue and build user engagement and loyalty rather than to “curate public discussions” (Ksiazek and Springer Citation2018, 482). Shutting down comment sections can result in discussions moving to social media sites instead (Quandt Citation2018). However, this does not necessarily mean that discussions hosted on social media are of any better quality (Rowe Citation2015).

A common denominator in research about the quality of news comments is that scholars often evaluate findings against the background of deliberative norms such as rationality, inclusion, respect, and civility (Engelke Citation2020; Ziegele et al. Citation2020). Thus, studies on the quality of news comments have tended to have a normative approach influenced by deliberative democracy theorists (see Steenbergen et al. Citation2003). Deliberation here refers to public discussion between free and equal citizens (e.g., Fung Citation2003; Habermas Citation1996). Thus, deliberation is to be seen as a process-focused view on democracy, where discussion of sufficient quality is considered essential for a well-functioning democracy (Dahl Citation1989; Habermas Citation1996). Generally, studies on the quality of comments have tried to capture the multi-dimensional concept deliberative quality (e.g., Graham and Wright Citation2015). Most studies operationalize deliberative criteria and conduct quantitative content analyzes to measure the extent to which comments meet these criteria (e.g., Beckert and Ziegele Citation2020; see Naab and Küchler Citation2022). While Oswald (Citation2022) has found that automated coding of deliberative quality can be useful and can complement manual content analyzes, it remains challenging to measure the deliberative quality of online discussions (Beauchamp Citation2020).

On a positive note, findings point out elements of deliberative discussions in comment sections (Rowe Citation2015; Ruiz et al. Citation2011; Strandberg and Berg Citation2013; Yang Citation2022). For example, comment sections can display rationality (Esau, Friess, and Eilders Citation2017; Graham and Wright Citation2015), inclusion (Esau, Friess, and Eilders Citation2017), and civility (Ksiazek Citation2015). Moreover, comments can reach acceptable levels of respect (Manosevitch and Walker Citation2009; Ruiz et al. Citation2011; Strandberg and Berg Citation2013), relevance (Collins and Nerlich Citation2015), civility (Eisinger Citation2011; Friess, Ziegele, and Heinbach Citation2021; Zhou, Chan, and Peng Citation2008), and reciprocity/interaction (Esau, Friess, and Eilders Citation2017; Graham and Wright Citation2015).

On a negative note, previous research has found several problems. Noci et al. (Citation2012) conclude that comments do not foster a democratic dialogue. Others similarly find that comments fail to live up to their deliberative potential, constitute low-quality discussion (Zimmermann Citation2014), and lack a dialogical nature (Parra, Ayerdi, and Fernández Citation2020). Other problems include incivility (Anderson et al. Citation2014; Chen Citation2017), racism (Harlow Citation2015), hate speech (Erjavec and Kovačič Citation2012) impoliteness (Neurauter-Kessels Citation2011), and trolling (Binns Citation2012). Santana (Citation2019) found low levels of rationality and high levels of uncivility in both anonymous and non-anonymous comments. Likewise, an early study by Paskin (Citation2010) indicated that comment sections feature off-topic conversations and personal attacks while simultaneously showing high levels of interaction between readers. Furthermore, research focusing on perceived quality of comments has found that the level of interaction does not seem to live up to deliberative ideals (Diakopoulos and Naaman Citation2011).

Findings about the quality of news comments have been inconclusive, although it is easier to point out pessimistic than optimistic conclusions (Friess, Ziegele, and Heinbach Citation2021, 627). Ziegele et al. (Citation2020, 861) conclude that the “pessimistic perspective of user comments seems to have gained the upper hand.” Mixed findings regarding quality have resulted in researchers turning their attention toward factors affecting the deliberative quality of news comments. Marzinkowski and Engelmann (Citation2022, 433) and Stroud et al. (Citation2015) conclude that decisions by news organizations as well as users’ argumentation both relate to the quality of discussions. Strategies for improving the quality of discussion include: moderation (Masullo, Riedl, and Huang Citation2022), user registration (Moore et al. Citation2021), comment policies (Ksiazek and Springer Citation2018), journalists/editors engaging in conversations (Stroud et al. Citation2015), selectively opening up stories for commenting (Nelson, Ksiazek, and Springer Citation2021), adding possibilities to highlight or upvote comments (Kolhatkar and Taboada Citation2017), and different mechanism for sorting comments (Peacock, Scacco, and Jomini Stroud Citation2019). Variations of these strategies are all in use in the public broadcaster comment sections this study analyzes.

Measurement and Data

The Context of the Study

Our study focuses on the Finnish public service broadcaster Yle’s news comments. Public service media are particularly interesting to study in this regard due to their perceived role as upholders of a forum for debate akin to part of a public sphere (see Fuchs Citation2014; Garnham Citation1990, 111). Yle states in its policies: “Yle supports democracy and citizens’ opportunities to participate through diverse discussions in the services and social media accounts maintained by Yle” (Yle Citation2023). In fact, Yle’s digital policies are eerily similar to the Public Service Internet-manifesto on how PSM should ideally perform their role in the digital age (see Fuchs and Unterberger Citation2021). Furthermore, Yle has an important role in Finnish society in general (Horowitz and Leino Citation2020), being one of the most trusted media outlets with over 90 percent of Finns feeling that Yle is reliable or very reliable (see Matikainen et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, Yle has a large audience with 96 percent of Finns accessing at least one of Yle’s services on weekly basis. Yle’s audience is diverse in terms of demographics and political views (see Schulz, Levy, and Nielsen Citation2019, 23). Yle clearly has an important role in Finnish society which makes it crucial that the public discussions it upholds are of good quality.

The data in the study derives from readers’ comments on online news stories published by Svenska Yle, the Swedish language branch Yle. With its high internet penetration rate and high overall trust in online media (Horowitz and Leino Citation2020), Finland can be considered a typical instance of a highly digitalized media environment. Finland is also a representative of the democratic corporatist media system (see Hallin and Mancini Citation2004 for description of traits of such media systems). We argue that Svenska Yle is a case of a national public broadcaster struggling with how to design, handle, and moderate comment sections (Jungar Citation2017, Citation2018). The main features Svenska Yle uses to ensure quality commenting are pre-moderation by journalists/editors, pseudonymous commenting (user registration), and journalistic engagement in comment sections (Yle Citation2023). This is exactly the same setting as the larger Finnish-speaking section of Yle uses. In an international comparison (cf., BBC), however, Svenska Yle is a non-typical PSM as its main target group is the Swedish-speaking minority, which consists of about five percent of the Finnish population. We regard Svenska Yle as a most-likely case for finding deliberative quality in comment sections due to the following reasons. First, commenting on Svenska Yle is pseudonymous, a setting producing more high-quality commenting than both anonymous and real-name commenting (Moore et al. Citation2021; see also Rowe Citation2015). Second, Svenska Yle should have more resources for comment moderation compared to smaller local news outlets (cf., Su et al. Citation2018, 3683). Arguably, as a public service broadcaster, Svenska Yle has a larger responsibility to host impartial democratic debates and to present diverging perspectives compared to private news outlets (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). Thus, Svenska Yle should not host comment sections for the sake of business strengthening or customer loyalty, but rather for providing an arena for public debate and for performing their role as a public service internet (see Fuchs and Unterberger Citation2021; Quandt Citation2018, 38). However, PSM do not operate completely outside of market logics, as they have to adapt to competitors use of online platforms by enabling, for example popular features such as algorithmic recommendations, which may bias the exposure of diversity, a fundamental value of PSM (Sørensen and Hutchinson Citation2018). Today, PSM compete for attention with social media such as Youtube, Tiktok and streaming platforms such as Netflix and Spotify, perhaps prompting PSM to shape user interaction promoting business interests rather than fostering democracy (Van Es and Poell Citation2020, 1). It seems as PSM are under pressure to extend their audience reach by employing functions found in other social media platforms to not be left behind (Van Es and Poell Citation2020, 2–3).

Measuring Discourse Quality

Several attempts to measure deliberative quality exist (e.g., Esau, Friess, and Eilders Citation2017; Marzinkowski and Engelmann Citation2022; Ziegele et al. Citation2020). A well-known contribution is the Discourse Quality Index (DQI), developed by Steenbergen et al. (Citation2003). Relying on the Habermasian theory of communicative action, DQI understands deliberation as “a systematic process wherein actors tell the truth, justify their positions extensively […] and are willing to yield to the force of the better argument", with the ultimate goal of reaching understanding, or consensus (Bächtiger et al. Citation2010, 33).

This prototypical view of deliberation has, however, been widely challenged (see Bächtiger et al. Citation2018 for an overview), with critics characterizing classic deliberative theory (and, by implication, DQI) as too idealistic (e.g., Shapiro Citation1999), too consensus-oriented (e.g., Mouffe Citation1999), too demanding (e.g., Posner Citation2004) and too rational (e.g., Sanders Citation1997). Consequently, contemporary deliberation research has departed somewhat from a narrow focus on rational discourse (e.g., Marzinkowski and Engelmann Citation2022; see Rossini and Stromer-Galley Citation2019, 6). Bächtiger and Parkinson (Citation2019) admit that DQI is insensitive to diverging goals and contexts. “Actors not only argue”, they claim, but also “use rhetorical strategies”, “tell stories or anecdotes”, “use confrontational or sarcastic language” and “bargain and make promises or threaths” (Bächtiger and Parkinson Citation2019, 70). In their view, future research should take this into account and incorporate a greater variety of communication forms into the deliberative toolbox, however, without eliminating the distinction between the deliberative core on the one hand, and other forms of communication on the other.

Our measurement strategy builds on these observations. Our intention is, hence, to capture the core components of deliberation and to examine the occurrence of other purportedly common discourse strategies such as the use of emotive and confrontative language.

Measuring Deliberativeness, Emotiveness and Confrontativeness

Building on Goertz (Citation2006, Citation2020), we structure our conceptualization and measurement in three levels. At the basic level, we find our core theoretical concepts deliberativeness, emotiveness and confrontativeness. The secondary level provides the constitutive dimensions (i.e., core definitions) the basic level concepts while the indicator level operationalizes the dimensions, allowing us to measure whether some specific phenomenon is an instance of that dimension or not.

Our first core theoretical concept is deliberativeness. Based on recent revisions of the prototypical model of deliberative theory (Cohen Citation1989; Habermas Citation1981), the term can be minimally defined by its two core components—reason-giving and listening (Bächtiger and Parkinson Citation2019, 23–24, 105–106). Reason-giving is the linking of claims to reasons. In this study, it is measured using four indicators, focusing, respectively, on the existence and level of argumentation, on external and internal validity, and substantive relevance. Listening, in contrast, refers to weighing and reflecting on perspectives given by others. To measure listening we use two indicators, capturing reciprocity (interaction with others) and openness (receptivity to other viewpoints), respectively.

As noted above, some deliberative theorists have suggested that alternative, not strictly rational, forms of communication should be considered in empirical studies of deliberation. Dryzek (Citation2000, 1), for example, proposes the inclusion of “rhetoric, humour, emotion, testimony or storytelling […] and gossip” but rules out more rebellious elements such as manipulation, deception, and threats. Young, by contrast, emphasizes how different backgrounds, experiences, and status might affect discursive abilities. Democratic deliberation should, therefore, not be restricted to “polite, orderly, dispassionate, gentlemanly argument”, but also allow “[d]isorderly, disruptive, annoying, or distracting means of communication” (Young Citation2000, 49–50).

Considering these remarks, this article empirically studies two additional forms of communication—emotiveness and confrontativeness. Emotiveness refers to core forms of passionate communication such as expression of and appeal to emotions (Bächtiger et al. Citation2010, 43; Bächtiger and Parkinson Citation2019, 70; Dryzek Citation2000, 1, 167; see empirical analyzes by Esau, Fleuß, and Nienhaus Citation2021; Marzinkowski and Engelmann Citation2022; Noci et al. Citation2012). To measure emotional expressions, we use indicators capturing manifest expressions of positive and negative emotions. Appeal to emotions is measured using indicators focusing on storytelling, i.e., the sharing of personal experiences and the telling of figurative anecdotes.

Confrontativeness, finally, captures communication that does not follow ideal-typical deliberative virtues such as politeness and civility, instead including both polemic antagonism and acerbic provocation (Bächtiger et al. Citation2010, 43; Bächtiger and Parkinson Citation2019, 70; Young Citation2000, 49; see empirical analyzes by Marzinkowski and Engelmann Citation2022; Strandberg et al. Citation2021). The indicators used to measure antagonism focus on disagreement (on substantial matters) and disapproval (of others’ cognitive capabilities). Provocations, in turn, are measured by the two indicators incivility and rigidity.

A more detailed description of the coding scheme is given in Online Appendix A. To test its reliability, three rounds of reliability tests were performed. After each round, coding instructions were revised, with more details (including coding examples) provided to coders. After the second round, the variables disagreement, disapproval and incivility were separated into three categories each, focusing on other debaters, journalists and publishers, and interviewees, respectively. reports inter-coder reliability scores for all variables.

Table 1. Reliability test of coding scheme.

The Data

The data was collected from 1.11.2020 to 31.10.2021.Footnote1 To ensure that comments were part of longer discussions we excluded news stories with less than ten comments. We also excluded genuine sports news (e.g., match reports) and announcements related to Svenska Yle’s own radio programs. To keep the number of comments manageable, we adopted a two-step random selection strategy. First, to cover news stories from all five regional editorial offices of Svenska Yle (Åboland, Capital region, Österbotten, Östra Nyland and Västra Nyland) each region was given two randomly selected months. The remaining two-month period (60 days) was divided into five equally sized parts, with each region being randomly given one part (i.e., one 12-day period). In the second step, we used stratified random sampling to select 30 (of the in total 157) news stories for further analysis. Our data set includes 565 news comments. Of these, 22 (3.9 percent) were written by an Yle journalist. The number of unique pseudonyms was 270, making the average of unique comments per pseudonym 2.1. The average length of comments was 294 characters. Tables A1 and A2 in the Online Appendix provide more detailed descriptive information on news and comments.

Results

To what extent does pre-moderated, pseudonymous commenting on Svenska Yle’s news live up to deliberative ideals of reasoning and listening? Moreover, to what extent are elements of emotiveness and confrontativeness present?

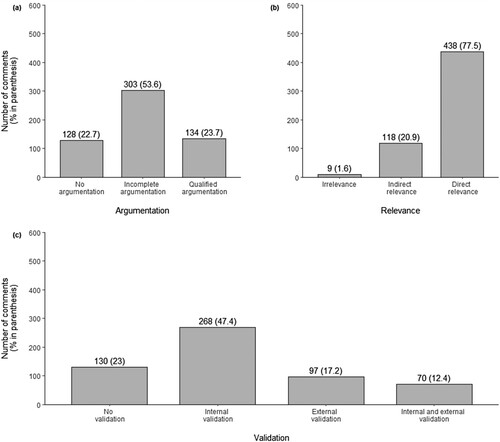

reports on reason-giving. As (a) shows, a clear majority of comments (77 percent) contain some form of argumentation. Incomplete argumentation occurs, however, more frequently than qualified argumentation: only about one-third of comments providing argumentation in favor of the advanced position also try to illuminate the linkage between the argument and the position. (b) illustrates the relevance of comments. As is evident, most comments (78 percent) are directly relevant to the topic of discussion, and only a few (9, or 2 percent) are entirely irrelevant. (c) demonstrates the use of internal and external validation. Most commonly, comments use internal validation—nearly half (47 percent) of the comments validate the preferred position by references to commentators’ values, opinions, and beliefs, without citing any external sources (e.g., facts or figures). 17 percent use only external sources while 12 percent use both external and internal sources. A sizeable minority of comments—23 percent—include neither external nor internal validation.

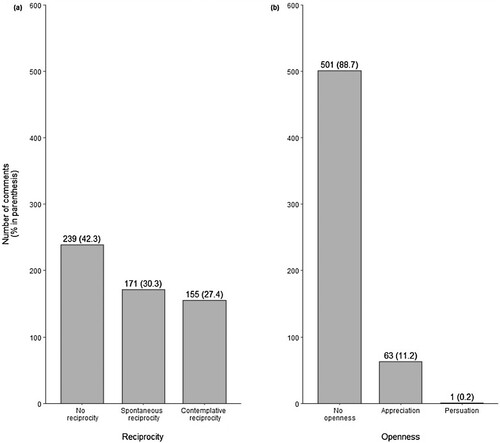

In , we focus on the second core feature of deliberativeness—listening. As (a) shows, a typical comment does not interact with other comments. Moreover, it seems that spontaneous reciprocity (30 percent) is more common than contemplative reciprocity (27 percent). A striking observation is that most comments seem to be rather firm. As shown in (b), most commentators (89 percent) tend to cling to their own viewpoints, without showing any appreciation or recognition of views presented by others. Reconsideration is even rarer than appreciation; only one single comment shows explicit signs of being persuaded by argumentation given in another comment.

* * *

Next, we move to emotiveness and confrontativeness. Regarding emotive content, the results clearly indicates that overt expressions of emotions are rare. Few comments show unambiguous evidence of negative emotions, and even fewer include positive emotions (4 and 2 percent, respectively). Similarly, very few comments appeal to emotions. Only 3 percent share stories of personal experiences and no more than 1 percent tell anecdotes. These observations point, above all, to the elusive nature of emotional content: systematic capturing of emotions from textual sources is a challenging, if not impossible, task. We opted to only include manifest expressions of emotions as an indication of emotiveness. There is thus a possibility that there are implicit expressions of emotions that are here treated coded as non-emotive. Therefore, our observations are clearly of tentative nature, emphasizing the need for more research on the use of emotions in news commenting.

Turning to confrontativeness, we begin by examining to what extent comments convey opposition, that is, disagreement with others on substantial matters and disapproval of other’s cognitive capabilities. As shows, disagreement with other debaters occur with some frequency. About one third (35 percent) of all comments express total disagreement with at least one other debater. Partial disagreement is less frequent, with only 4 percent of comments expressing both agreement and disagreement with other debaters. further reveals that disagreement—to the extent that it occurs—is oriented towards other debaters rather than towards Svenska Yle (journalists/editors) or interviewees. The same general pattern occurs in ; disapproval is, undoubtedly, less common than disagreement, but when it occurs it is typically directed towards other debaters, and only rarely towards Svenska Yle and/or towards interviewees.

Table 2. Disagreement.

Table 3. Disapproval.

The second element of confrontativeness, provocation, is virtually non-existent in comments. Nearly all debaters express their views in a civilized manner, without reverting to stereotyping or harassment. Rigidity is also very rare, with only eight comments including conspiratorial reasoning (and no comment including subversiveness). Hence, the study of confrontativeness leads to two major conclusions. First: opposition is rare, but more common than provocation. Second: it is more common to challenge other debaters’ viewpoints (disagreement) than to question their cognitive capabilities (dislike).

Discussion and Conclusions

News comments are somewhat of a two-edged sword. On the one hand, they hold the potential for constituting a digital public sphere full of rational, reciprocal and democratic discussion between citizens. On the other hand, though, the reality of online comments has often turned out to be rather harsh (e.g., Coe, Kenski, and Rains Citation2014; Parra, Ayerdi, and Fernández Citation2020; Santana Citation2019), which has typically led to especially commercial media closing comment sections altogether (Graf Citation2021; Quandt Citation2018, 37; Ziegele et al. Citation2020, 861). Often-occurring malaises of news comments have been a general lack of argumentation and fact-based discussion (e.g., Santana Citation2019), a high degree of emotionally driven messages and confrontations between online commentators (e.g., Coe, Kenski, and Rains Citation2014; Erjavec and Kovačič Citation2012). We explored these elements in news comments on the Finnish public service broadcaster Yle’s website. Public service media, we argued, hold a central position in the surrounding society and hold an obligation to uphold the societal discussion (see also Yle’s guidelines for discussion, Yle Citation2023). The purpose of this article has been to assess the deliberative quality of the public sphere in Finland by addressing the research question: What is the deliberative quality of comments on Svenska Yle’s news articles? Using a systematic quantitative content analysis of 565 news comments, we analyzed their deliberativeness, emotiveness, and confrontativeness. What were the main findings of our exploration of Svenska Yle’s news comments?

Starting with deliberativeness, which measures the amount of reasoning and listening commenters practice, our findings are mixed. On a positive note, commenters mostly try to argue their points implying that comments usually are rational, which is in line with previous findings (e.g., Esau, Friess, and Eilders Citation2017; Graham and Wright Citation2015; Yang Citation2022) while contradicting others (e.g., Noci et al. Citation2012; Santana Citation2019). Our findings resemble those of Zhou, Chan, and Peng (Citation2008) in that comments featured argumentation, but that the complexity of argumentation was relatively low in the sense that commenters could use external sources more often and provide clearer connections between their positions and reasons for these. Related to the complexity of argumentation, commenters are more prone to use internal validation than external validation. They mainly refer to their own values, opinions and information when making an argument. Still, external sources and information a found in 17 percent of comments, which is a higher share than findings in similar studies (Noci Citation2012; Parra, Ayerdi, and Fernández Citation2020; Rowe Citation2015; Strandberg and Berg Citation2013). Thus, similar to findings by Manosevitch and Walker (Citation2009), commenters on Svenska Yle seem relatively prone to share additional information in their comments, indicating that their comments add value to discussions.

Regarding relevance, that is, commenting on the topic of the article, the results show that irrelevant comments are very rare, similar to previous studies (Collins and Nerlich Citation2015; Rowe Citation2015; Ruiz et al. Citation2011; Strandberg and Berg Citation2013). This finding is the opposite of other studies where a vast majority of comments was irrelevant (Coe, Kenski, and Rains Citation2014; Parra, Ayerdi, and Fernández Citation2020). The pre-moderation of comments might be the explanation for the high share of on-topic comments (Ruiz et al. Citation2011).

Another aspect of deliberativeness is the amount of listening between commenters (Scudder Citation2022). Therefore, commenters should show reciprocity with others and be open to each other’s viewpoints (Friess, Ziegele, and Heinbach Citation2021). Here, our findings leave room for improvement, as the most common type of reciprocity is no reciprocity at all. However, commenters do reply to each other, albeit mostly in a spontaneous manner. The share of reciprocal comments in Svenska Yle’s comment sections is slightly higher than previous findings of Strandberg and Berg (Citation2013) and over 20 percentage points higher than in the study of Zhou, Chan, and Peng (Citation2008, 766). Yet, Esau, Friess, and Eilders (Citation2017) and Esau and Friess (Citation2022) found a higher share, 76 percent, of reciprocal news comments in German news media. Thus, in a relative perspective, the reciprocity in this study was acceptable and quite similar to previous studies (Graham and Wright Citation2015; Santana Citation2019).

As emotions, personal experiences, and humor are essential parts of online discussion (Rossini and Stromer-Galley Citation2019, 6), we sought capture the concept emotiveness by measuring expressions of emotions and appeals to emotions in comments. By doing so, we investigate the “tolerant concept of deliberation” focusing on expressions of emotions and storytelling in addition to the “classic concept of deliberation” focusing on rationality, reciprocity, respect, and constructiveness (Esau, Fleuß, and Nienhaus Citation2021, 10). In sum, we found emotional expressions to be very rare, 4 percent of comments featured negative emotions and only 2 percent positive emotions. This is a much smaller share compared to previous research on emotional expression in news comments. For example, Santana (Citation2019) found emotional expressions in 28–46 percent of comments, Esau, Fleuß, and Nienhaus (Citation2021) detected 2 percent positive and 23 percent negative emotions, while Marzinkowski and Engelmann (Citation2022) found 15 percent negative emotions. This finding is rather surprising, given that studies have found high levels of negative emotions in news comments (e.g., Anderson et al. Citation2014). However, as we alluded to in the results-section, our restrictive coding could be one explanation for the low share of emotions in our data. Another possible explanation could be that all our analyzed comments were moderated, and emotive content might have been omitted by Yle before publication.

The concept confrontativeness means communication recognized as both polemic antagonism and acerbic provocation rather than ideal-typical deliberative virtues such as politeness and civility. To capture this type of speech, we measured the level of disagreement, disapproval, incivility, and rigidity. Scholars measure the level of disagreement in discussions because some level of disagreement is necessary to signal that different viewpoints are present (Esterling, Fung, and Lee Citation2015; Gastil Citation2018). Online discussions lacking disagreement might polarize opinions due to like-minded people discussing with each other (Wright, Graham, and Jackson Citation2017). We found disagreement in over one third of the comments, while disapproval was very rare; incivility and rigidity were practically non-existent. Previous studies of news comments have found varying levels of disagreement. The level of disagreement we found is similar to previous findings (Strandberg and Berg Citation2013; Zhou, Chan, and Peng Citation2008), but lower than others (Santana Citation2019). Disagreement in news comments in not necessarily a problem as long as it does not digress into incivility (Masullo Chen and Lu Citation2017) and comments with high argument strength tend to receive (reasoned) disagreement (Marzinkowski and Engelmann Citation2022). Thus, our results can be considered quite positive, as there is moderate disagreement in the comment section (Esterling, Fung, and Lee Citation2015). However, it is difficult to set a threshold for how much disagreement is healthy in comment sections. Finally, several studies on news comments have found high levels of incivility (Chen Citation2017; Coe, Kenski, and Rains Citation2014; Parra, Ayerdi, and Fernández Citation2020), while, in contrast, our study found very low levels of incivility. Therefore, our findings are in line with positive findings (Eisinger Citation2011; Strandberg and Berg Citation2013; Zhou, Chan, and Peng Citation2008).

Some limitations of our study are worth mentioning. Did an effective moderation strategy ensure quality in the comments? We cannot say much about the causal relationship between the measures (e.g., moderation, journalistic involvement) Svenska Yle has taken and the quality of deliberation. An answer to these types of questions would require an experimental design. We asked Svenska Yle for access to deleted/refused comments to investigate their deliberative quality. Our request was denied. Moderators refuse a considerable share, 26–30 percent, of comments (Hindsberg Citation2016). Due to the pseudonymity allowed at Svenska Yle, we cannot analyze the gender distribution among commenters. Gender equality is a measure of quality related to inclusion and a previous study of BBC’s online forums found high gender inequality as men dominated the forum (Quinlan, Shephard, and Paterson Citation2015). As previously noted, we found it difficult to achieve high inter-reliability measured with Krippendorff’s alpha for some variables although previous studies have reported high inter-coder reliability using similar instruments such as the discourse quality index (DQI) (Bächtiger, Gerber, and Fournier-Tombs Citation2022, 86; see also Beckert and Ziegele Citation2020, 3931). A final potential limitation could be that our case Svenska Yle, being a PSM for a language minority, might not be entirely representative of all PSM. Thus, our conclusions from Svenska Yle may not be readily generalizable per se albeit that, as we have discussed, Svenska Yle generally displays the same traits as PSM in general and public service internet as well.

To conclude, this study analyzed the deliberative quality of news comments on the website of Finnish public service broadcaster Svenska Yle. Doing so, we argue that we fill a research gap by studying news comments hosted by a public service broadcaster. In a comparative perspective, our findings are positive since the overall quality level exceeds that of several previous studies. As to why that is the case, we can only be speculative since we have not systematically tested factors that lead to high comment quality. Nonetheless, it is perceivable that the strict public service internet ethos of Svenska Yle (and Yle in general) manifested in their policies for moderation, is one explanation of the high quality we found. Of course, the mere fact that all comments were moderated serves to raise quality as well. A further potential contextual factor might be the Finnish public’s perception of Yle as a very high quality and trustworthy news outlet, which could induce people into being more constructive in their comments. Media systems with strong public service media, compared to other media systems, tend to display good resilience to malaises of the digital realm (see e.g., Fletcher, Cornia, and Nielsen Citation2019; Humprecht, Esser, and Van Aelst Citation2020). We believe that our findings are indicative of the same phenomenon. Another contribution of this study is also a novel coding scheme for measuring the quality of news comments. Moreover, we have discussed methodological lessons learnt from our exploration. In sum, our findings point away from pessimistic conclusions about the quality of news comments, as Svenska Yle’s comment sections do not feature dark participation and incivility. As public service media, and public service internet (Fuchs and Unterberger Citation2021) are central and trusted actors and arenas for upholding a public sphere (Fuchs Citation2014; Horowitz and Leino Citation2020), our findings are rather encouraging for the potential of digital public debate when conveyed through high-quality media platforms.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (549.3 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This time period was chosen to exclude late fall 2021, when Svenska Yle applied a new, stricter, policy regarding the opening of news stories to readers’ comments.

References

- Anderson, A. A., D. Brossard, D. A. Scheufele, M. A. Xenos, and P. Ladwig. 2014. “The “Nasty Effect:” Online Incivility and Risk Perceptions of Emerging Technologies.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19 (3): 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12009.

- Bächtiger, A., J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. E. Warren. 2018. “Deliberative Democracy: An Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. E. Warren, 1–31. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1662-6370.2007.tb00086.x.

- Bächtiger, A., M. Gerber, and E. Fournier-Tombs. 2022. “Discourse Quality Index.” In Research Methods in Deliberative Democracy, edited by S. A. Ercan, H. Asenbaum, N. Curato, and R. F. Mendonça, 83–98. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192848925.001.0001.

- Bächtiger, A., S. Niemeyer, M. Neblo, M. R. Steenbergen, and J. Steiner. 2010. “Disentangling Diversity in Deliberative Democracy: Competing Theories, Their Blind Spots and Complementarities.” The Journal of Political Philosophy 18 (1): 32–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00342.x.

- Bächtiger, A., and J. Parkinson. 2019. Mapping and Measuring Deliberation: Towards a New Deliberative Quality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199672196.001.0001.

- Beauchamp, N. 2020. “Modeling and Measuring Deliberation Online.” In The Oxford Handbook of Networked Communication, edited by B. F. Welles, and S. González-Bailón, 321–349. Online edition: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190460518.001.0001.

- Beckert, J., and M. Ziegele. 2020. “The Effects of Personality Traits and Situational Factors on the Deliberativeness and Civility of User Comments on News Websites.” International Journal of Communication 14:3924–3945.

- Binns, A. 2012. “DON'T FEED THE TROLLS! Managing Troublemakers in Magazines’ Online Communities.” Journalism Practice 6 (4): 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2011.648988.

- Boberg, S., T. Schatto-Eckrodt, L. Frischlich, and T. Quandt. 2018. “The Moral Gatekeeper? Moderation and Deletion of User-Generated Content in a Leading News Forum.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 58–69. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1493.

- Chen, G. M. 2017. Online Incivility and Public Debate: Nasty Talk. Online edition. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56273-5.

- Chung, J. E. 2019. “Peer Influence of Online Comments in Newspapers: Applying Social Norms and the Social Identification Model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE).” Social Science Computer Review 37 (4): 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318779000.

- Coe, K., K. Kenski, and S. A. Rains. 2014. “Online and Uncivil? Patterns and Determinants of Incivility in Newspaper Website Comments.” Journal of Communication 64 (4): 658–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12104.

- Cohen, J. 1989. “Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy.” In The Good Polity: Normative Analysis of the State, edited by A. Hamlin, and P. Petit, 17–34. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Collins, L., and B. Nerlich. 2015. “Examining User Comments for Deliberative Democracy: A Corpus-Driven Analysis of the Climate Change Debate Online.” Environmental Communication 9 (2): 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.981560.

- Conlin, L., and C. Roberts. 2016. “Presence of Online Reader Comments Lowers News Site Credibility.” Newspaper Research Journal 37 (4): 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532916677056.

- Dahl, R. A. 1989. Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Diakopoulos, N., and M. Naaman. 2011. “Towards Quality Discourse in Online News Comments.” In Proceedings of the ACM 2011 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, March, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1145/1958824.1958844.

- Dryzek, J. S. 2000. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Eisinger, R. 2011. “Incivility on the Internet: Dilemmas for Democratic Discourse.” In APSA 2011 Annual Meeting Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id = 1901814.

- Engelke, K. M. 2020. “Enriching the Conversation: Audience Perspectives on the Deliberative Nature and Potential of User Comments for News Media.” Digital Journalism 8 (4): 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1680567.

- Erjavec, K., and M. P. Kovačič. 2012. “You Don't Understand, This is a New War!” Analysis of Hate Speech in News Web Sites’ Comments.” Mass Communication and Society 15 (6): 899–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.619679.

- Esau, K., D. Fleuß, and S.-M. Nienhaus. 2021. “Different Arenas, Different Deliberative Quality? Using a Systemic Framework to Evaluate Online Deliberation on Immigration Policy in Germany.” Policy & Internet 13 (1): 86–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.232.

- Esau, Katharina, and Dennis Friess. 2022. “What Creates Listening Online? Exploring Reciprocity in Online Political Discussions with Relational Content Analysis.” Journal of Deliberative Democracy 18 (1): 130. http://dx.doi.org/10.16997/jdd.1021.

- Esau, K., D. Friess, and C. Eilders. 2017. “Design Matters! An Empirical Analysis of Online Deliberation on Different News Platforms.” Policy & Internet 9 (3): 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.154.

- Esterling, K. M., A. Fung, and T. Lee. 2015. “How Much Disagreement Is Good for Democratic Deliberation?” Political Communication 32 (4): 529–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.969466.

- Fletcher, R., A. Cornia, and R. K. Nielsen. 2019. “How Polarized Are Online and Offline News Audiences? A Comparative Analysis of Twelve Countries.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (2): 169–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219892768.

- Friedman, E. 2011. “Talking Back in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Rational Dialogue or Emotional Shouting Match?” Conflict & Communication 10 (2): 1–18.

- Friess, D., M. Ziegele, and D. Heinbach. 2021. “Collective Civic Moderation for Deliberation? Exploring the Links Between Citizens’ Organized Engagement in Comment Sections and the Deliberative Quality of Online Discussions.” Political Communication 38 (5): 624–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1830322.

- Frischlich, L., S. Boberg, and T. Quandt. 2019. “Comment Sections as Targets of Dark Participation? Journalists’ Evaluation and Moderation of Deviant User Comments.” Journalism Studies 20 (14): 2014–2033. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1556320.

- Fuchs, C. 2014. “Social Media and the Public Sphere. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique.” Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 12 (1): 57–101. https://triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/download/552/529.

- Fuchs, C., and K. Unterberger. 2021. The Public Service Media and Public Service Internet Manifesto. London: University of Westminster Press. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/50934/11/9781914386299.pdf.

- Fung, A. 2003. “Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices and Their Consequences.” Journal of Political Philosophy 11 (3): 338–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00181.

- Garnham, N. 1990. Capitalism and Communication: Global Culture and the Economics of Information. London: Sage.

- Gastil, J. 2018. “The Lessons and Limitations of Experiments in Democratic Deliberation.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (1): 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113639.

- Goertz, G. 2006. Social Science Concepts: A User’s Guide. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Goertz, G. 2020. Social Science Concepts and Measurement. 2nd ed.. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Goodman, E., and F. Cherubini. 2013. Online Comment Moderation: Emerging Best Practices. Online edition. Darmstadt, Germany: the World Association of Newspapers (WAN-IFRA) .https://netino.fr/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/WAN-IFRA_Online_Commenting.pdf

- Graf, J. 2021. “The Prevalence of Comment Sections in US Daily Newspapers.” In 46th Annual AEJMC Southeast Colloquium, Virtual conference sponsored by Elon University, March 2021.

- Graham, T., and S. Wright. 2015. “A Tale of Two Stories from “Below the Line” Comment Fields at the Guardian.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 20 (3): 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161215581926.

- Habermas, J. 1981. Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Habermas, J. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790867.

- Harlow, S. 2015. “Story-Chatterers Stirring up Hate: Racist Discourse in Reader Comments on U.S. Newspaper Websites.” The Howard Journal of Communications 26 (1): 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2014.984795.

- Hindsberg, M. 2016. Kvinnliga journalister och artiklar om invandring drar åt sig fula kommentarer. Svenska Yle, June 5, 2016. https://svenska.yle.fi/a/7-1080164.

- Horowitz, M., and R. Leino. 2020. “Pandemic and Public Service Media: Lessons from Finland.” Baltic Screen Media Review 8 (1): 18–28. https://doi.org/10.2478/bsmr-2020-0003.

- Humprecht, E., F. Esser, and P. Van Aelst. 2020. “Resilience to Online Disinformation: A Framework for Cross-National Comparative Research.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (3): 194016121990012. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219900126.

- Ihlebæk, K. A., and E. Ytreberg. 2009. “Moderering av digital publikumsdeltakelse – Idealer, praksiser og dilemmaer.” Norsk Medietidsskrift 16 (1): 48–64. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN0805-9535-2009-01-04.

- Jungar, J. 2017. Jonas Jungar: Om kommentarerna här på Svenska.yle.fi. Svenska Yle, October 22, 2017. https://svenska.yle.fi/a/7-1245300.

- Jungar, J. 2018. Från och med tisdag måste du ha ett Yle-konto för att kommentera våra artiklar - här är orsakerna. Svenska Yle, April 23, 2018. https://svenska.yle.fi/a/7-1296975.

- Kolhatkar, V., and M. Taboada. 2017. “Using New York Times Picks to Identify Constructive Comments.” In Proceedings of the 2017 EMNLP Workshop: Natural Language Processing Meets Journalism, Copenhagen, September 2017, 100–105. https://aclanthology.org/W17-4218/.

- Kolhatkar, Varada, Hanhan Wu, Luca Cavasso, Emilie Francis, Kavan Shukla, and Maite Taboada. 2020. “The SFU Opinion and Comments Corpus: A Corpus for the Analysis of Online News Comments.” Corpus Pragmatics 4 (2): 155–190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s41701-019-00065-w.

- Ksiazek, T. B. 2015. “Civil Interactivity: How News Organizations’ Commenting Policies Explain Civility and Hostility in User Comments.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59 (4): 556–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1093487.

- Ksiazek, T. B. 2018. “Commenting on the News: Explaining the Degree and Quality of User Comments on News Websites.” Journalism Studies 19 (5): 650–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1209977.

- Ksiazek, T. B., and N. Springer. 2018. “User Comments in Digital Journalism: Current Research and Future Directions.” In The Routledge Handbook of Developments in Digital Journalism Studies, edited by B. Franklin, and S. Eldridge II, 475–486. London: Routledge.

- Lacy, S., B. R. Watson, D. Riffe, and J. Lovejoy. 2015. “Issues and Best Practices in Content Analysis.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92 (4): 791–811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015607338.

- Lee, S., L. Atkinson, and Y. H. Sung. 2022. “Online Bandwagon Effects: Quantitative Versus Qualitative Cues in Online Comments Sections.” New Media & Society 24 (3): 580–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820965187.

- Lee, E., and Y. J. Jang. 2010. “What do Others’ Reactions to News on Internet Portal Sites Tell us? Effects of Presentation Format and Readers’ Need for Cognition on Reality Perception.” Communication Research 37 (6): 825–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210376189.

- Lombard, Matthew, Jennifer Snyder-Duch, and Cheryl Campanella Bracken.2017. “Intercoder Reliability.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, edited by Mike Allen, 722–724. Los Angeles, California: Sage publications.

- Manosevitch, E., and D. Walker. 2009. “Reader Comments to Online Opinion Journalism: A Space of Public Deliberation.” In International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, April 17–18, 2009, 1–30. Vol. 10.

- Marzinkowski, H., and I. Engelmann. 2022. “Rational-Critical User Discussions: How Argument Strength and the Conditions Set by News Organizations Are Linked to (Reasoned) Disagreement.” Digital Journalism 10 (3): 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1957968.

- Masullo, G. M., M. J. Riedl, and Q. E. Huang. 2022. “Engagement Moderation: What Journalists Should Say to Improve Online Discussions.” Journalism Practice 16 (4): 738–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1808858.

- Masullo Chen, G., and S. Lu. 2017. “Online Political Discourse: Exploring Differences in Effects of Civil and Uncivil Disagreement in News Website Comments.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 61 (1): 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2016.1273922.

- Matikainen, J., M. Ojala, M. Horowitz, and J. Jääsaari. 2020. Media ja yleisön luottamuksen ulottuvuudet: instituutiot, journalismi ja mediasuhde. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/319153/hy_tunteet_pelissa_raportti.pdf

- McCluskey, M., and J. Hmielowski. 2012. “Opinion Expression During Social Conflict: Comparing Online Reader Comments and Letters to the Editor.” Journalism 13 (3): 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911421696.

- McDermott, L. 2016. “Online News Comments as a Public Sphere Forum: Deliberations on Canadian Children’s Physical Activity Habits.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 53 (2): 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216644444.

- Mitchelstein, E. 2011. “Catharsis and Community: Divergent Motivations for Audience Participation in Online Newspapers and Blogs.” International Journal of Communication 5 (1): 2014–2034.

- Moore, A., R. Fredheim, D. Wyss, and S. Beste. 2021. “Deliberation and Identity Rules: The Effect of Anonymity, Pseudonyms and Real-Name Requirements on the Cognitive Complexity of Online News Comments.” Political Studies 69 (1): 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719891385.

- Mouffe, C. 1999. “Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism?” Social Research 66 (3): 745–758. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40971349

- Naab, T. K., and C. Küchler. 2022. “Content Analysis in the Research Field of Online User Comments.” In Standardisierte Inhaltsanalyse in der Kommunikationswissenschaft–Standardized Content Analysis in Communication Research: Ein Handbuch-A Handbook, edited by F. Oehmer-Pedrazzi, S. H. Kessler, E. Humprecht, K. Sommer, and L. Castro, 441–450. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36179-2_37.

- Nagar, N. A. 2011. “The Loud Public: The Case of User Comments in Online News Media (Publication No. 3460834).” Doctoral dissertation, State University of New York at Albany. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Nelson, M. N., T. B. Ksiazek, and N. Springer. 2021. “Killing the Comments: Why do News Organizations Remove User Commentary Functions?” Journalism and Media 2 (4): 572–583. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040034.

- Neurauter-Kessels, M. 2011. “Im/Polite Reader Responses on British Online News Sites.” Journal of Politeness Research: Language, Behaviour, Culture 7 (2): 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1515/jplr.2011.010.

- Newman, Nic , Fletcher Richard, Kalogeropoulos Antonis, Levy David, and Nielsen Rasmus Kleis. 2017. Reuters institute digital news report 2017. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 1–108. Retrieved from: http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2017/

- Nielsen, C. 2012. “Newspaper Journalists Support Online Comments.” Newspaper Research Journal 33 (1): 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953291203300107.

- Noci, J. D. 2012. “Mubarak Resigns: Assessing the Quality of Readers’ Comments in Online Quality Media.” Tripodos 1 (30): 83–106. http://www.tripodos.com/index.php/Facultat_Comunicacio_Blanquerna/article/view/24.

- Noci, J. D., D. Domingo, P. Masip, J. L. Micó, and C. Ruiz. 2012. “Comments in News, Democracy Booster or Journalistic Nightmare: Assessing the Quality and Dynamics of Citizen Debates in Catalan Online Newspapers.” International Symposium on Online Journalism 2 (1): 46–64.

- Oswald, L. 2022. Automating the Analysis of Online Deliberation? A Comparison of Manual and Computational Measures Applied to Climate Change Discussions. SocArXiv Papers. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/qmzwx.

- Parra, O. C., K. M. Ayerdi, and S. P. Fernández. 2020. “Behind the Comments Section: The Ethics of Digital Native News Discussions.” Media and Communication 8 (2): 86–97. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.2724.

- Paskin, D. 2010. “Say What? An Analysis of Reader Comments in Bestselling American Newspapers.” Journal of International Communication 16 (2): 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13216597.2010.9674769.

- Peacock, C., J. M. Scacco, and N. Jomini Stroud. 2019. “The Deliberative Influence of Comment Section Structure.” Journalism 20 (6): 752–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917711791.

- Pfetsch, B. 2020. “Democracy and Digital Dissonance: The co-Occurrence of the Transformation of Political Culture and Communication Infrastructure.” Central European Journal of Communication 13 (1): 96–110. https://doi.org/10.19195/1899-5101.13.1(25).7.

- Posner, R. 2004. “Smooth Sailing.” Legal Affairs, January/February 2004. https://www.legalaffairs.org/issues/January-February-2004/feature_posner_janfeb04.msp.

- Prochazka, F., P. Weber, and W. Schweiger. 2018. “Effects of Civility and Reasoning in User Comments on Perceived Journalistic Quality.” Journalism Studies 19 (1): 62–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1161497.

- Quandt, T. 2018. “Dark Participation.” Media and Communication 6 (4): 36–48. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1519.

- Quinlan, S., M. Shephard, and L. Paterson. 2015. “Online Discussion and the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum: Flaming Keyboards or Forums for Deliberation?” Electoral Studies 38:192–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.02.009.

- Rösner, L., and N. C. Krämer. 2016. “Verbal Venting in the Social Web: Effects of Anonymity and Group Norms on Aggressive Language Use in Online Comments.” Social Media + Society 2 (3): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116664220.

- Rossini, P., and J. Stromer-Galley. 2019. “Citizen Deliberation Online.” In Oxford Handbook of Electoral Persuasion, edited by E. Suhay, B. Grofman, and A. Tresel, 690–712. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190860806.013.14.

- Rowe, I. 2015. “Deliberation 2.0: Comparing the Deliberative Quality of Online News User Comments Across Platforms.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59 (4): 539–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1093482.

- Ruiz, C., D. Domingo, J. L. Micó, J. Díaz-Noci, K. Meso, and P. Masip. 2011. “Public Sphere 2.0? The Democratic Qualities of Citizen Debates in Online Newspapers.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 16 (4): 463–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161211415849.

- Sanders, L. M. 1997. “Against Deliberation.” Political Theory 25 (3): 347–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591797025003002.

- Santana, A. D. 2011. “Online Readers’ Comments Represent New Opinion Pipeline.” Newspaper Research Journal 32 (3): 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953291103200306.

- Santana, A. D. 2012. “Civility, Anonymity and the Breakdown of a New Public Sphere (Publication No. 3523471).” Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Santana, A. D. 2019. “Toward Quality Discourse: Measuring the Effect of User Identity in Commenting Forums.” Newspaper Research Journal 40 (4): 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532919873089.

- Santana, A. D., and T. Hopp. 2022. “Seeing Red: Reading Uncivil News Comments Guided by Personality Characteristics.” Newspaper Research Journal 43 (2): 196–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/07395329221094662.

- Schulz, A., D. A. Levy, and R. Nielsen. 2019. Old, Educated, and Politically Diverse: The Audience of Public Service News. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/The_audience_of_public_service_news_FINAL.pdf.

- Scudder, M. F. 2022. “Measuring Democratic Listening: A Listening Quality Index.” Political Research Quarterly 75 (1): 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912921989449.

- Shapiro, I. 1999. “Enough of Deliberation: Politics is About Interests and Power.” In Deliberative Politics: Essays on Democracy and Disagreement, edited by S. Macedo, 28–38. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Singer, J. B., and I. Ashman. 2009. “Comment is Free, but Facts Are Sacred”: User-Generated Content and Ethical Constructs at the Guardian.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 24 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08900520802644345.

- Sjøvaag, H., H. Moe, and E. Stavelin. 2012. “Public Service News on the Web: A Large-Scale Content Analysis of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation's Online News.” Journalism Studies 13 (1): 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2011.578940.

- Sørensen, J. K., and J. Hutchinson. 2018. “Algorithms and Public Service Media.” In Public Service Media in the Networked Society: RIPE@2017, 91–106. Nordicom. http://www.nordicom.gu.se/sites/default/files/publikationer-hela-pdf/public_service_media_in_the_networked_society_ripe_2017.pdf.

- Springer, N., I. Engelmann, and C. Pfaffinger. 2015. “User Comments: Motives and Inhibitors to Write and Read.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (7): 798–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.997268.

- Steenbergen, M. R., A. Bächtiger, M. Spörndli, and J. Steiner. 2003. “Measuring Political Deliberation: A Discourse Quality Index.” Comparative European Politics 1 (1): 21–48. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110002.

- Steinfeld, N., T. Samuel-Azran, and A. Lev-On. 2016. “User Comments and Public Opinion: Findings from an Eye-Tracking Experiment.” Computers in Human Behavior 61:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.004.

- Strandberg, K., and J. Berg. 2013. “Online Newspapers’ Readers’ Comments - Democratic Conversation Platforms or Virtual Soapboxes?” Comunicação e Sociedade 23 (1): 132–152. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.23(2013).1618.

- Strandberg, K., J. Berg, T. Karv, and K. Backström. 2021. When Citizens Meet Politicians: The Process and Effects of Mixed Deliberation According to Status and Gender. ConstDelib Working Paper Series no. 12, June 2021. https://constdelib.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/WP12-2021-v.2-CA17135.pdf.

- Stroud, N. J., J. M. Scacco, A. Muddiman, and A. L. Curry. 2015. “Changing Deliberative Norms on News Organizations’ Facebook Sites.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (2): 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12104.

- Su, L. Y., M. A. Xenos, K. M. Rose, C. Wirz, D. A. Scheufele, and D. Brossard. 2018. “Uncivil and Personal? Comparing Patterns of Incivility in Comments on the Facebook Pages of News Outlets.” New Media & Society 20 (10): 3678–3699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818757205.

- Van Es, K., and T. Poell. 2020. “Platform Imaginaries and Dutch Public Service Media.” Social Media+ Society 6 (2), 205630512093328. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120933289.

- von Sikorski, C., and M. Hänelt. 2016. “Scandal 2.0: How Valenced Reader Comments Affect Recipients’ Perception of Scandalized Individuals and the Journalistic Quality of Online News.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 93 (3): 551–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016628822.

- Weber, M., C. Viehmann, M. Ziegele, and C. Schemer. 2020. “Online Hate Does Not Stay Online – How Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Mediate the Effect of Civil Negativity and Hate in User Comments on Prosocial Behavior.” Computers in Human Behavior 104:106192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106192.

- Wolfgang, J. D. 2018. “Cleaning up the “Fetid Swamp” Examining How Journalists Construct Policies and Practices for Moderating Comments.” Digital Journalism 6 (1): 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1343090.

- Wolfgang, D., and M. Bhandari. 2020. “Commenter and News Source Credibility: Roles of News Media Literacy, Comment Argument Strength and Civility.” Southwestern Mass Communication Journal 36 (1): 29–49. https://doi.org/10.58997/smc.v36i1.81.

- Wolfgang, J. D., S. McConnell, and H. Blackburn. 2020. “Commenters as a Threat to Journalism? How Comment Moderators Perceive the Role of the Audience.” Digital Journalism 8 (7): 925–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1802319.

- Wright, S., T. Graham, and D. Jackson. 2017. “Third Space and Everyday Online Political Talk: Deliberation, Polarisation, Avoidance.” In The 67th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, May 2017.

- Yang, J. 2022. “Deliberating Issued or Discharging Feelings? A Closer Look at” Below-the-Line” Reader Comments on the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands Dispute.” American Communication Journal 24 (1): 1–13.

- Yle. 2023. Guidelines for Discussion, March 10, 2023. https://yle.fi/aihe/s/discussion-policy.

- Young, I. M. 2000. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zhou, X., Y. Chan, and Z. Peng. 2008. “Deliberativeness of Online Political Discussion: A Content Analysis of the Guangzhou Daily Website.” Journalism Studies 9 (5): 759–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700802207771.

- Ziegele, M., P. Jost, M. Bormann, and D. Heinbach. 2018. “Journalistic Counter-Voices in Comment Sections: Patterns, Determinants, and Potential Consequences of Interactive Moderation of Uncivil User Comments.” Studies in Communication and Media 7 (4): 525–554. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2018-4-525.

- Ziegele, M., O. Quiring, K. Esau, and D. Friess. 2020. “Linking News Value Theory with Online Deliberation: How News Factors and Illustration Factors in News Articles Affect the Deliberative Quality of User Discussions in SNS’ Comment Sections.” Communication Research 47 (6): 860–890. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218797884.

- Zimmermann, T. 2014. “Explaining Deliberativeness. The Design of Readers’ Comments.” International Reports on Socio-Informatics 11 (1): 99–106.