Abstract

This essay focuses on an aspect of photographic practices that are often seen but seldom discussed in contemporary Chinese photography: the creative practices that focus on the relationship (e.g. complementarity and contrast) between text and image. Concerning the traditions of Chinese literati painting, contemporary semiotic theories from the West, and the development of narratologies, this essay examines the works of several contemporary photographic artists in China that combine text and image. More specifically, it focuses on the theoretical framework behind the diverse practices of the twenty-first century. It addresses three main topics: the traditions of Chinese literati painting (which includes poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving), Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory and its application in the visual world, and the theories and paradigms of storytelling in the evolution of narratology into its newer form. In addition, the essay explores how text and image theories and paradigms of different origins exist in contemporary art practices, as well as how they have extended the meanings of these works through the complementarity and conflict between text and image.

Introduction

Before becoming a researcher and curator in the history and culture of photography, I studied linguistics, lexicology, and English-language literature. When I turned my attention to photography in graduate school, I remained interested in the relationship between text and image. Thanks to the ‘Theorising Photographies in Contemporary China’ special issue, I now have an opportunity to re-examine the visual art practices that center on the interrelationship between text and image in Chinese contemporary photography since 2010. In this essay, I identify the origins of the theories and knowledge behind the photographic practices in which text and image are integrated to understand how cultural and theoretical discourses from both the East and the West have inspired photographic practices and helped expand their meanings and forms of expression.

Across fields and disciplines, many have analyzed the partnership between text and image. In the last 30 years, for example, this includes research on historical painting, iconology, photographic and lens-based art. It is worth mentioning that the focus of this essay is not text-image theories. Instead, it places their practices and contexts in a decentralized theoretical and narrative framework to reveal the diverse sources of knowledge (i.e. the knowledge) of contemporary photographic practices in China. Furthermore, the rich topicality of text-image paradigms, the variety of photographic languages, and the complexity of the methods of presentation in these artworks, as well as their dialogs with art practices from different periods in Chinese history, provide an introduction to contemporary Chinese photography—for both general audiences and photographic practitioners and researchers.

The rhetoric of text and image in traditional Chinese literati painting and its appropriation

In the 1920s, salons that used photography as the medium of communication became increasingly popular in Shanghai. Members of these salons saw ‘art photography’ as their mission and used the pictorialist model in their work. However, they did not merely imitate the style of pictorial photographers from the West; they also explored paradigms within the framework of traditional Chinese aesthetics. One of these salons was the Chinese Photographic Society (zhonghua sheying xueshe, 中华摄影学社) founded by Lang Jingshan 朗静山 (1892–1995) and his colleagues.Footnote1 As a professional photographer, Lang Jingshan developed a unique style called ‘composite photography’ (jijin sheying, 集锦摄影). Inspired by traditional Chinese painting, jijin depends on meticulous postproduction and darkroom manipulations, including a labor-intensive process of cutting, pasting, shading, and multiple exposures, according to Mia Yinxing Liu (Citation2015, 1).

The purpose of jijin in Lang Jingshan’s work was to produce photographs that closely resembled traditional Chinese ink-wash paintings. In Lang’s monologue, The Collected Photographs of Jingshan (1928), there is a photograph titled Trying Horses (Shi ma, 试马). In this vertically composed photo, the two horses and the people around them take up only one-third of the image; the rest of the space is occupied by the calligraphy of Lang’s close friend Chen Wanli 陈万里 (1892–1969), another pioneer of Chinese photography in Republican China. In Shi ma, which the photography historian Chen Hsueh-sheng (Citation2015, 99) has described as a ‘photographic painting’ (sheyinghua, 摄影画), one can see the construction of a style that differs from classic pictorialist photography. The photo not only imitates the style of traditional Chinese painting, but it is also a Chinese-style photographic painting in its own right. As Chen (Citation2015, 99) has noted, the handwritten text is a perfect example of how the tradition of communication and relationship-building through painting and calligraphy among the literati in China (with which the amateur photographers in Shanghai were familiar) persist in photography.

The photographic works I discuss in the rest of the article are separated from Lang Jingshan’s practice by a century. Still, Lang’s ‘composite photography’ remains an essential component of the history of photography in China. It demonstrates the attempt of a pioneer photographer, ‘an intellectual who suffered through the pains of colonisation and the Warlord Era’ (Chen and Xu Citation2011, 167), to develop a creative paradigm suitable for Chinese art in contrast with Western photographic practices. If Lang and his contemporaries utilised the replicability of analog photography to create an artistic language for Chinese photographers, then contemporary Chinese photographic practitioners working in the twenty-first century have continued using the rhetoric and aesthetics of the text-image relationship in traditional literati painting; they have done so while pushing the boundaries of the language and meaning of their works through constantly evolving technologies in the context of globalisation.

Wei Bi 魏壁, who was born in rural Hunan, China, in 1969, is known for a style that combines calligraphy and photography. This style is visually inspired by his experience growing up in the countryside and by his love for calligraphy. Since 2010, he has explored a contemporary style that fuses black-and-white photos with traditional Chinese calligraphy to portray the landscape and people of his hometown, Mengxi 梦溪.

Wei’s calligraphic photography is reminiscent of traditional literati painting in its style and subject. Su Shi 苏轼 (1037–1101 AD), one of the Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song Dynasties, praised the work of Wang Wei 王维 (whose courtesy name was Mojie 摩诘), writing, ‘one can see the painting in Mojie’s poetry and the poetry in his painting’.Footnote2 He also wrote that ‘poetry and painting are essential of the same origin; they should be natural, clear, and fresh’.Footnote3 As Su Shi noted, Chinese artists had sought to integrate poetry and painting since the Song dynasty, and they often created ‘poetic paintings’ to express their interpretation of literature. In the art theorist Zhang Gaoyuan’s (Citation2021) research on the rhetoric of the texts and images in traditional yaji 雅集 paintings (portrayals of the ‘elegant gatherings’ of intellectuals and artists), he mentions that the style of poetic paintings evolved over time: By the Ming Dynasty, it had become the custom to add inscriptions to paintings, a practice that reflected the close relationship and mutual respect between painters and calligraphers at the time. The connection between paintings and their inscriptions is the first indication of the integration of image and text in Chinese literati painting. In this case, the text can help the viewer understand the deeper meaning of the painting.

This connection is also seen in Wei Bi’s Mengxi 梦溪 (2008–2010), in which the photographer reserves the space around the medium-format black and white photos of his hometown for his own calligraphy. Written in zhangcao 章草 (a type of cursive script), these texts include the stories behind the photos, elaborate explanations of the vernacular culture, and fragments of the photographer’s memory. The dreamy landscape of the Chinese countryside resonates with the traditional-style calligraphy, which recalls one of the art historian Zhang Yanyuan’s 张彦远 (815–907 AD) observations in Famous Paintings through History (Citation2004 [847]): ‘Calligraphy and painting have different names, but they share the same body’.Footnote4 This quote is a concise summary of the intimate relationship between Chinese calligraphy and painting. Although the ‘body’ Zhang referred to is often misunderstood as a synonym for ‘genre’, what he meant is that the calligraphy and painting in a work of art share the same individual style of the artist and the same stylistic tradition. According to the photography critic Zhang Ze’ou,Wei Bi’s unique style, which evokes the artistic traditions of the Wei-Jin 魏晋 period (220–420 AD), has helped him establish his reputation in the world of contemporary Chinese photography after 2010.Footnote5

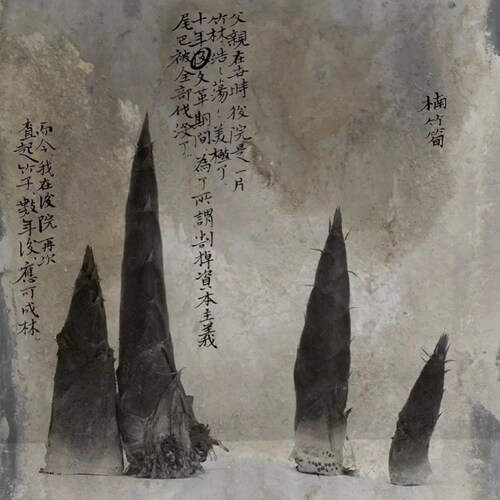

In Zhang Gaoyuan’s (Citation2021) research on the literary rhetoric of yaji paintings, he notes that the second function of text in these paintings is to express ideas and refine spaces through rhetoric: ‘the classical references and metaphors in the poetry turn real scenes into imagined ones, obtain both feeling and form, and help the viewer understand the pure form of the image’. In Mengxi II (梦溪II, 2010–2013), the natural scenery is replaced with still life, and the photographer writes over the images directly. The style of the calligraphy has changed from zhangcao to xingshu 行书 (semi-cursive). In a photo titled Nanzhu Shoots (Nanzhu sun, 楠竹筍), four chunks of freshly picked bamboo shoots are placed on the ground in an upright position, like mountain peaks. The calligraphy on the photograph reads: ‘When my father was still alive, there was a bamboo forest behind the house; it was quite impressive and beautiful. During the decade of the Cultural Revolution, the trees were all cut down as an attempt to “cut the tail of capitalism”. I have planted some new trees in the backyard, and they should grow into a forest in a few years (). In this case, calligraphy is not only part of the image, but it also functions as a rhetorical device that adds a historical and cultural dimension to the artwork.

Figure 1. Wei Bi, Nanzhu Shoots, from the series Mengxi II. Photography and calligraphy, Courtesy of the artist.

Another contemporary photography artist who has adopted the text-image paradigm of traditional literati painting is Yang Yongliang 杨泳梁. In his work, Yang utilizes the manipulability of digital technology in his criticism of Chinese-style skyscrapers and consumer culture and to create his signature ‘digital shanshui landscapes’. Unlike Wei Bi, who is self-taught, Yang Yongliang (b. 1980, Shanghai) has studied under Yang Yang 杨洋 (a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong) since he was a child, and he trained professionally in traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy. After graduating from the China Academy of Art in 2003 with a degree in visual communication, he applied his newly acquired skills in digital technology to the traditional artistic expressions he learned when he was young. By arranging and incorporating thousands of real-life photographs (which depict modern entities such as transmission towers, scaffolding, excavators, and skyscrapers) into the schema of classic artworks from different periods in Chinese history, he critically analyzes the many issues of urbanisation with a new kind of shanshui landscape.

Though text gradually disappeared from Yang’s photography and video artworks after 2010, his early work Phantom Landscape (Shenshi shanshui 蜃市山水, 2006) exemplifies the appropriation and incorporation of symbolic texts into digital landscapes. In Phantom Landscape III (), the ideograms in the image are a combination of Chinese characters and numbers; upon closer inspection, the viewer realizes that they include advertising leaflets (which usually contain text and phone numbers) that can be found in the streets, stock-tracking spreadsheets, and even source code. They appear in the artwork as ‘inscriptions’, retaining the style of traditional literati paintings while serving the function of ‘anchorage’ in semiotics, in addition to leaving room for the viewer to reflect on the meaning of numbers as the symbol of the capitalist era.Footnote6

Figure 2. Yang Yongliang, ‘Forbidden City’, from the series Phantom Landscape III. Digital photography. Courtesy of the artist.

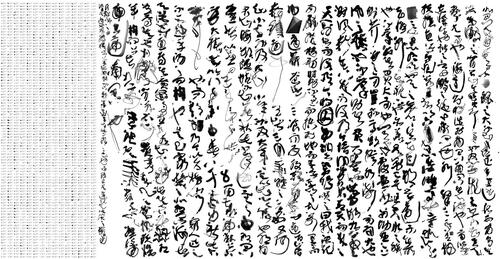

Following the footsteps of Wei Bi and Yang Yongliang, Li Shun 李舜, who was born in Xuzhou in 1988, extracts and rearranges tens of thousands of long-exposure photos in his work to turn traces of light and shadows into the brushstrokes of cursive calligraphy, completing the transformation from image to text and back to the image. Since the series, We Survive on Nothing but a Fading Reality (我们 生存的立足点除了不断消逝的现实之外别无 其它, 2010), Li Shun has sought ways to integrate photography, Chinese calligraphy, and digital technology. In the series, he tries to capture ‘the black, undisrupted traces that resemble washed ink’ in moving scenes to contemplate the meaning of time and existence (Luo Citation2021). This kind of philosophical musing has inspired the artist to retrace the history of Chinese aesthetics in his practice.

In the series Study on the Nature of Things (Gewu zhizhi 格物致知, 2016–), Li Shun extracts the elements of the thousands of abstract light trails that are similar in form or meaning to the brushstrokes of Chinese characters and converts them into actual characters (or images that look similar to actual characters) based on the masterpieces of famous calligraphers. In the inscription, he writes the time and places each ‘brushstroke’ is collected (). The juxtaposition of characters and numbers creates a kind of visual tension that reveals the technological labor hidden behind the image. To quote Luo Yubin (Citation2021), the artist has created a new system with the contemporary medium of photography; by replacing handwriting with a process of matching and assembling, he creates new representations through appropriation, encouraging the viewer to re-examine the tradition of calligraphy and to explore the possibility of renewing traditions with tools from the contemporary world. Compared to the works of the other two artists mentioned in this section, Li Shun’s Study on the Nature of Things has preserved the self-consistency of ‘the oneness of calligraphy and painting’ in both form and meaning.

Figure 3. Li Shun, ‘Study on the Nature of Things - Rewrite A Happy Excursion’, photography, digital image post-processing, printed on rice paper, 185 cm × 360 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Much extraordinary research has appeared on the rhetoric of text and image in the interdisciplinary fields of Chinese art and literature, and the resulting theories have been applied to analyzes of early Buddhist paintings, monument inscriptions, literati landscape paintings, as well as the poetry and prose from the Tang and Song Dynasties. In the first section, I have retraced the origins of the works of three photographers to illustrate how the texts and images in contemporary photography can be constructed under the paradigm of Chinese literati paintings, and I have shown how they expanded the meanings of artworks in different creative contexts and discourses. It is now clear that the works of these artists can also be analyzed through the lens of semiotic and image theories from the West, much like Jonathan Hay has studied Chinese paintings from the Song Dynasty through the theories of Hubert Damisch and Georges Didi-Humberman. Martin J. Powers (Citation2022) has also used W. J. T. Mitchell’s theory to interpret Chinese literati paintings in a recent online discussion. Further, scholars from the West often use semiotic and image theories from Western art history to analyze Chinese paintings and the text-image relationship in traditional literati paintings, and new connections often emerge from these cross-cultural comparisons. In the next section, I follow another important theoretical thread that has influenced the text-image relationship in contemporary Chinese photography—Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory—and explore the related practices and developments.

Western semiotic theories and polysemic image practices

Before I entered the field of photography as a researcher and curator, I was once intrigued by a photograph that introduced me to the world of contemporary Chinese art. The center of this photo is occupied by the giant Chinese character ‘bu’ 不 (‘no’). Every stroke of the character falls on the body of a half-naked man, whose mouth and cheeks are covered by the horizontal stroke on top as if he cannot speak. In this case, the literal meaning of the character (‘no’) and the visual connotation of the image (‘unable to’) influence and complement each other. This photo comes from a series centered on Qiu Zhijie’s performance art in 1994. The literal meaning of the character ‘bu’, which is written in red, helps the viewer understand the performance of the artist (covering his body—and especially his mouth—with red paint) by providing semiotic support and creating a space for interpretation between text and image.

Throughout the twentieth century, scholars such as Ferdinand de Saussure (Citation1986 [1916]), Charles Sanders Peirce (Citation1991), Roland Barthes (1977), and Jacques Derrida (Citation1978 [1967]) developed semiotic theories that provided theoretical support and research methods for art history, visual culture, media studies, architecture, and many other disciplines, including fields that focus on communication and information transfer. The main concern of semiotics is the way meanings are created and communicated through signs. The relationship between text and image—the two semiotic systems that have historically been considered different fields of research—are connected in semiotic analyzes provided by scholars such as Victor Burgin (Citation2018 [1975]), W. J. T. Mitchell (Citation1987) and Meyer Schapiro (Citation1996), and a new realm to explore in their studies of visual arts. Around the same time, text also became the focus of the practices of artists such as Ed Ruscha, Barbara Kruger, and Mel Bochner, who ultimately changed the landscape of contemporary art.

In the article ‘Art, Common Sense and Photography’ (2018 [1975], 27), Victor Burgin used Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory to explain the polysemy of the image (which is controlled by the juxtaposition of text and image) for the first time to analyze the creation of meaning in advertising photography and news images:

Roland Barthes has identified two different functions which the verbal message can adopt in relation to the image, these he calls anchorage and relay. The text adopts a function of anchorage when, from a multiplicity of connotations offered by the image, it selects some and thereby implicitly rejects the others. Thus, in a cigarette advertisement, the contradictory connotations ‘cigarettes give pleasure’ and ‘cigarettes give cancer’ are selectively handled in such a caption as cool as a mountain stream, a simile which endorses the suggestion of pleasure while rejecting that of unwholesomeness…

In relay, the image and the linguistic text are in a relationship of complementarity: the linguistic message explains, develops, expands the significance of the image… [In a previous example], the caption is in a relationship of relay to the image. ‘It’s all in the mind’ is not amongst the connotations we might expect to be summoned by the image alone. It is not therefore ‘anchored’ from amongst the connotations already available. The rhetorical structure of the text/image relation in this case is that of paradox. The dominating connotation of the image may be labeled (but not contained) by the linguistic term ‘poverty’. Substituting this term for the image gives us the statement: ‘Poverty. It’s all in the mind.’ However, we know the poverty depicted in the image to be a material poverty. Hence the paradox, and hence the effect gained by the juxtaposition of such a caption with such an image. (2018[1975], 27)

Among the polysemic practices featured in this section, the works of three artists have utilized the relay function of image and text to various extents. These artists have used language to explain, develop, and expand the meaning of the image. Li Lang 黎朗, who was born in Chengdu in 1969, is well known for his exploration of the relationship between text and image in works that focus on memory and history. Li Lang’s father was born on 3 December 1927 and passed away on 27 August 2010, meaning that he spent 30,219 days on earth. In Father (2014), Li Lang prints photos of his father when he was still alive, including ones the artist took himself—of his father’s face, skin, footprints, hair, and possessions—and dates everything with a pencil. Combined with images of the father and his possessions, the seemingly meaningless numbers of the dates become proof of Li’s father’s life in this world.

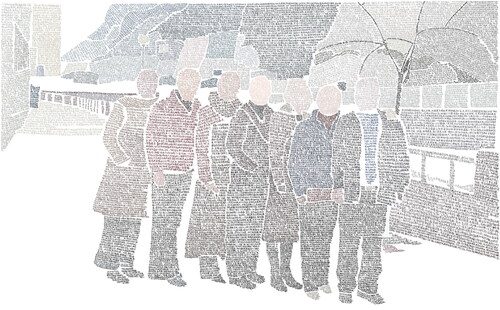

‘My Father’s Last Portrait B, [Father 1927.12.03–2010.08.27]’ () is based on the last portrait of Li Lang’s father before he died. In the photo, one sees the father’s profile, including the age spots on his head and his open lips (probably because he had difficulty breathing); he is shown in his final days. Upon closer examination, one realizes that the portrait is covered with dense text that takes up the entire photo. Here, the aesthetics of pure information is added to the information contained in the black and white image, uniting three layers of time—the 30,219 days Li’s father spent on earth, the time of his death, and the time the artist spends dating each image—in one.

Figure 4. Li Lang, ‘My Father’s Last Portrait B, [Father 1927.12.03–2010.08.27]’, from the series Father, handwriting on photographic paper, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

![Figure 4. Li Lang, ‘My Father’s Last Portrait B, [Father 1927.12.03–2010.08.27]’, from the series Father, handwriting on photographic paper, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.](/cms/asset/15a89b25-85b1-415c-972e-95ae427e8496/rfpc_a_2142015_f0004_b.jpg)

In 1974 (2017), text, image, and sound are simultaneously presented. This series includes 390 family photos Li Lang collected. At the exhibition, the photos, in the form of film slides, are played on a loop by five projectors and accompanied by the artist’s narration (). The slides consist of vintage photos Li collected from different places in recent years, including studio portraits, travel photos, as well as snapshots of work and everyday scenes. Li puts these images in various categories and dates them by hand according to a fictional timeline, which takes the photos out of their original contexts and turns them into metaphors for memory in the artist’s narrative. As the projectors show the vintage photos, Li’s vivid narration in his native dialect provides context for the images and creates a sense of immersion for the audience. On the other hand, as the textual component of the installation, the voiceover also makes it more difficult for the viewer to understand the work because it is an expression of Li’s reflection on the conflict between reality and fiction in history and images.Footnote7

In these projects, Li Lang experiments with different structures (for example, by covering images with words and by juxtaposing audio files with text and images) to explore the complementarity of text and image, through which he manages to take the audience’s thoughts outside the photographic images and into a larger realm.

Focusing on similar subjects, He Bo 何博, another photographer from Sichuan, has also explored the creation of meaning and the aesthetic paradigms of the relationship between text and image. His work often focuses on memory, history, and disasters. While attending graduate school in the Netherlands, He Bo explored his own identity by retracing the collective memory of his hometown through the Wenchuan earthquake (May 12, 2008). Measuring 8.0 Ms, the earthquake took tens of thousands of lives and destroyed about 500,000 square kilometers of land, affecting most of China and multiple regions in Asia. In Wish You Happy (He, Citation2022), He Bo gives shape to his images with handwritten text to explore the boundary between language and image, which is the opposite of the method in Li Shun’s work (see the previous section).

In Wish You Happy, He Bo reconstructs the images in the photos he collected by ‘writing a relatively small text on group photos of people who are affected by the earthquake, which were not and did not need to be accessible to outsiders like me originally. The text I write includes my own thoughts while looking at the photos, my guesses as to what happened before and after the photos were taken (photography as events) from my perspective as a photographer, and the resonance I feel as a Sichuan native (which is triggered by the details of the people and scenes in the photos). I try to rely on this commonality (to a certain extent) and relatively lengthy viewings of the images (the first image alone took me half a month), or a kind of “co-temporality” (which is still wishful thinking), to approach the images while expressing my thoughts’.Footnote8

In ‘Wish You Happy 01′ (), He Bo reflects on the family photos, the individual fate of the earthquake victims in the photos, and the meaning of photographic images by replacing image with text. In his words, ‘the people in the photos, as well as the “normal” location and function of group photos (which should be kept in an album or a computer and viewed occasionally), are lost and turned into something else prematurely. The images are no longer sharable records of the different stages of a living human being’s life but have quickly become the only medium for emotions and memories’.Footnote9 If Li Lang’s work uses the density of linguistic messages (Father) and their polysemic nature (1974) to expand the meaning of images, then He Bo’s work focuses more on the pure form of linguistic messages. The artist not only removes the visual content of the images, but also finds an appropriate visual expression for the subjects of his work (disasters, memory, and photography).

Roland Barthes’s writing on the relay function of linguistic message and image contains a paradox of the rhetorical structure of the text/image relation; that paradox is often a result of the ambiguity between text and image. In Iconology: Image Text Ideology, W. J. T. Mitchell notes that ‘the relationship between words and images reflects, within the realm of representation, signification, and communication, the relations we posit between symbols and the world, signs, and their meanings. We imagine the gulf between words and images to be as wide as the one between words and things, between (in the largest sense) culture and nature’ (1986, 43). In ‘Five Events and Some Observations on Identity’ (2017), the artist Jiang Yuxin 姜宇欣 (b. 1987, Shanghai) leads the viewer in a search for meaning in carefully designed traps through the gulf between text and image. The title itself is an exploration of ideas, and the series of images centered on the relationship between text and image is inspired by the identity issues the artist experienced while studying and living in London. The details from her everyday conversations and encounters made her doubt the legitimacy of the stereotypical categorization of identity based on one’s nationality.

In this series, Jiang Yuxin plays with the construction and deconstruction of meaning between the title, image, and text of each photo. In ‘The girl from the bakery at the end of the road walked past in a punk outfit. She looked like a different person from the one in the bakery’, one of the five photos in Event 4, we see a London cab driving down an empty road (). There is no sign of either the bakery or the punk girl mentioned in the title. As our eyes are about to leave the frame of the photo from the right, however, Chinese speakers notice the sign saying ‘China Eastern Airlines’, which would resonate with those who have experience living abroad. In this case, the sense of identification is triggered by the text in the photo.

Figure 7. Jiang Yuxin. ‘The girl from the bakery at the end of the road walked past in a punk outfit. She looked like a different person from the one in the bakery’, from the series Five Events and Some Observations on Identity, photography, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

The images capture multicultural ‘Chinese’ objects and commodities the artist encountered in her life as an international student, the architectural cross-sections of various types of Chinese institutions lurking in the streets of London, and the materials the artist extracted from her own experience of embarrassment and invisibility as a result of identity differences; the series combines still photos, images, and texts to turn private thoughts into complex visual artworks that reveal the artist’s perspective on various issues. As Mitchell (Citation1986, 43) has stated, ‘the word is [the image’s] “other”, the artificial, arbitrary production of human will that disrupts natural presence by introducing unnatural elements into the world—time, consciousness, history, and the alienating intervention of symbolic mediation’. In Five Events and Some Observations on Identity, Jiang expands the space and imagination of the time and history of the photos between the anchoring function of the texts and the ambiguity of the titles, which serve the opposite function.

In this section, I have connected the photo-text practices of three Chinese artists to Western semiotic theories to understand how these artists used the polysemic nature of the image to explore the relationship between words and ideas and the connection between discourse and the mind, as well as how they incorporated the semiotic theories in their own works. In the last section of this essay, I address other practices in the context of the history of photography and explore the ongoing interaction between photography and literary narratives; I also consider how the different paradigms of this interaction have affected photo-text practices.

Explorations and practices of narratologies

The narrative nature of photography has been a focus for practitioners since the medium’s invention. In news images (Roger Fenton), photo stories (Walker Evans, James Agree), photographic essays (W.G. Sebald, Wim Wenders), and photographic novels (Ed van der Elsken, Sophie Calle), photos and texts are incorporated into artists’ works through different arrangements, taking viewers to times and spaces outside the images.

The third theoretical reference for contemporary text-image practices in China is the theories and paradigms in cross-media narratives (especially the interaction between photographic and literary narratives). Narratologies refer to the examination, renewal, and evolution of classic structuralist narratology by scholars from the late twentieth century through the present (represented by the work of David Herman). By exploring literature, photography, film, and new-media art, the new theoretical framework combines the methodologies and perspectives of semiotics, structuralism, psychoanalysis, linguistics, feminism, and other fields and approaches. Compared to the theoretical sources discussed in the first two sections, narratologies are more concerned with analyzing the diversity and complexity of contemporary visual art narratives from the perspective of literary narratives.

In Avatars of Story, Marie-Laure Ryan—a scholar of narratologies—clarifies the boundaries of narratives and media (2006, 18–19) and divides the ‘media as semiotic phenomena’ into four categories: language, images, music, and ‘moving pictures without soundtrack’. Ryan (Citation2006, 19) analyzes the ‘can do’ (e.g. ‘immerse spectator in space, map story world’) and the ‘cannot do’ (e.g. ‘make explicit propositions … represent flow of time, thought, interiority’) of images, as well as strategies that can be used to compensate for these limitations: ‘use intertextual or intermedial reference through the title to suggest a narrative connection. Represent objects within the storyworld that bear verbal inscriptions. Use multiple frames or divide the picture into distinct scenes to suggest the passing of time, change, and causal relations between scenes. Use graphic conventions (thought bubbles) to suggest thoughts and other modes of nonfactuality’. In her work, Ryan emphasizes cross-disciplinary and cross-media narratologies and demonstrates the various shapes the story can take as a form of meaning in both traditional and new media.

Turning from narratologies to the latest research on photo-texts in photography, the Italian photography historian Federica Chiocchetti, who has a background in literature, has ‘composed [a definition] by integrating convincing elements from multiple thinkers with [her] own’ (Citation2021, 22) through eight years of research:

A photo-text is a ‘bimedial iconotext’, namely a hybrid compound work in which both photographic images and words co-exist and constitute the body of work within the pages of a book or the space of a gallery (Lagerwall, 2006). They must ‘simultaneously be read and viewed’ together (Hunter, 1987), to form new meanings while preserving equal and separate ontological dignity—and at times distance—to ‘shoot some tensions’ (Montandon, 1990) or trigger dynamics that juxtapose the two systems of signs without confusing them. In photo-texts, photographs and words are partners in crime that create a ‘dialogue to which neither of the two media can, even for a moment, escape’ (Cometa, 2017). This dialog or ‘interpenetration of images and words’ (Bryson, 1988) enhances each medium’s narrative potential and expands the fictionality—intended here as the imaginary latent quotient—of the work as a whole since in the constant back and forth and tension between looking at the images and reading the words, a third unattainable object or ‘third something’ (Eisenstein, 2004) develops only in the viewer’s and reader’s mind, ‘the one who ultimately always “makes sense” of’ photo-texts (Wagner, 1995). Before the ‘third something’ can develop in the mind of the reader/viewer, images and texts have to be incorporated or devoured by the ‘mediating organ of the eye’, which swallows everything, obliterating the difference between the written and the visual (Richon, 1991).

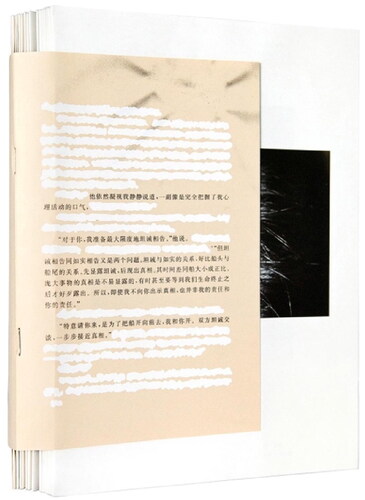

Figure 8. Chen Zhe, The Bearable and Bees, photobook, edition of 800, 1 + 19 saddle-stitched booklets, 75 color plates, 40 greyscale journals and letters, 280 pages, 26 × 21 × 2.5 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 9. Chen Zhe, The Bearable and Bees, photobook, edition of 800, 1 + 19 saddle-stitched booklets, 75 color plates, 40 greyscale journals and letters, 280 pages, 26 × 21 × 2.5 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

In Towards Evenings: Six Chapters (2012–), Chen quests for the nebulous space between day and night, light and twilight, the known and the unknown. With a particular focus on the tension between reading and viewing, the series draws inspiration from literary and visual materials across time and cultures. The Chinese phrase xiangwan 向晚 (‘towards evening’) refers to the period when the sun is about to set. It alludes to uncertainty and transience and appears in classical poetry as a metaphor for decline and as an expression of melancholy. Three of the six chapters in this series are already in progress: ‘The Uneven Time’, ‘Nightfall Disquiet’, and ‘The Red Cocoon’. In these chapters, Chen Zhe explores the visual and linguistic textuality of the temporality of dusk, the language of dusk, and the individual’s response to this language.

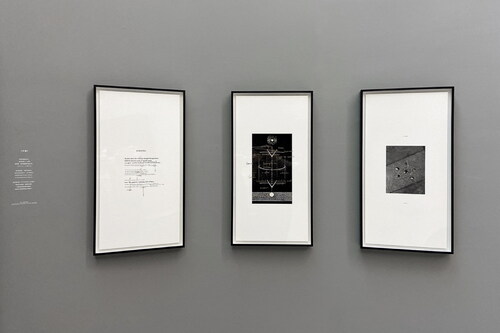

The second chapter, ‘Nightfall Disquiet’, includes three works centered on the literary expression of dusk. In ‘Study of a Poem by Rainer Maria Rilke’ (), the artist uses Rilke’s ‘Evening’ (‘Abend’)—a poem that depicts the state of trance brought on by experiencing dusk—as a source of meditation. The triptych includes a photo of an annotated translation of the poem (text), a diagram of the constellation (image), and the aftermath of a child’s game. In form, the three images point to three different steps of cognition—‘the collation of the text, the encapsulation of ideas, and the unexpected encounter of the image’—but they are conceptually unified in the ending of Rilke’s poem: ‘One moment your life is a stone in you, and the next, a star’.Footnote11

Figure 10. Chen Zhe, ‘Study of a Poem by Rainer Maria Rilke’, ‘Nightfall Disquiet’, from the series Towards Evenings: Six Chapters (2012–). Archival pigmented inkjet prints with handwriting, 45 × 85 × 10 cm each, 2016. On view at ‘Peer to Peer’, Shanghai Center of Photography, Shanghai, China, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

In a similar vein, Yang Yuanyuan 杨圆圆 examined the relationship between text and image narratives before turning to film. Born in Beijing in 1989, Yang has studied and worked in London since 2007. Starting with her first book, 10 Days in Kraków (2014) and with At the Place of Crossed Sights (2015–2016) () and Dalian Mirage (2017–2019), Yang’s projects have been based on the cities she lived in or traveled to (). The media she uses (journals, photos, stories, videos, and films) often form a unified narrative. Yang calls her method ‘visual writing’.Footnote12 During the process, she collected a vast quantity of materials, including vintage photos bought at flea markets, novels, animated films, texts from movies, archival materials (postcards, letters, coins), and her own snapshots, videos, and journals from her trips. The artist organizes and rearranges all these materials, which eventually form the visual narratives in her works.

Figure 11. Yang Yuanyuan, ‘At the Place of Crossed Sights’, mixed media, exhibition view of a solo show at C-Space, Beijing, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

At the Place of Crossed Sights is a work of ‘meta-photography’, that is, photography about photography. The series includes photos, novels, various archival materials, and mixed-media installations. Set in Porto Alegre, Brazil, where Yang Yuanyuan briefly stayed, the project is based on research revolving around several photographers who lived and worked or briefly remained in the city. The artist created a series of works combining factual materials and fictional narrations. Through the study and depiction of the characters’ individual experiences, the project explores the complex relations between various elements such as photographers, photographs, cities, migration, and memory within the progression of the history of photography.Footnote13

The exhibition features a collection of five short stories. These stories resemble scriptwriting, and this practice paved the way for Yang Yuanyuan’s subsequent video works. The stories in the collection are based on the artist’s experience traveling and living in Brazil and on extensive textual research; they address various topics that are closely related to the twentieth century from a personalized, nuanced perspective. Accompanying the stories are the photos Yang took or collected in Brazil; other complex materials also appear, and together, these form Yang’s signature ‘visual writing’.

In this final chapter, I have examined the works of two artists who explore their subjects—from dusk to photography itself—through the lens of narratologies, as well as how they bring the viewer into the integrated narrative of text and image through the structural arrangement and exhibition design of their work.

Conclusion

In this essay, I have traced the origins of the theories and paradigms behind the works of contemporary Chinese photographers who use the relationship between text and image as their creative language. The first section focuses on the text-image rhetoric in Chinese literati painting, as well as how contemporary image artists have used its paradigm and function to construct their own visual language and expand the complexity of their subjects and the diversity of their expressions with the latest technologies. In the second section, I turned to Western theories that have influenced text-image practices in Chinese photography, including Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory and W.J.T. Mitchell’s iconology, to understand how contemporary artists have used the polysemic nature of the image to explore the relationship between text and ideas. I further considered the connection between discourse and the mind and how artists have adopted this connection. In the last section of the essay, I examined the works of two artists through the lens of Federica Chiocchetti’s complex definition of the ‘photo-text’. I explored the ways photographic and literary narratives coexist and complement each other to create multiple layers of meaning in art practices.

It is worth mentioning that the theoretical and intellectual foundation of the text-image practices in contemporary Chinese photographic work is not limited to the three categories mentioned in the essay; rather, it has a much broader cultural and intellectual structure. In addition, the theories and paradigms discussed in the essay are not strictly distinctive; they often overlap and influence each other in art practices. As part of the ‘Theorising Photographies in Contemporary China Special Issue’, the purpose of this essay is to introduce the reader to contemporary Chinese photography, especially the practices that have expanded or are in the process of expanding the expressions of photography through the diverse text-image theories and traditions from both China and the West.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yining He

Yining He (b.1986) is an independent researcher and curator of contemporary visual art. Her current PhD research centers on decoloniality in post-2008 Chinese contemporary art practice and examines the interconnections between individual artists’ experiences, global geopolitical interactions, and decolonizing art discourse. In an academic context, Yining has written, edited, and participated in numerous books, including Une Histoire Mondiale des Femmes Photographies (2020), The Port and the Image (2017/2019), and Photography in the British Classroom (2015), among others. Her papers have been published or are forthcoming in the Routledge Companion to Photography and Visual Culture, Photographies, OVER Journal, Journal of Taipei Fine Arts Museum, New Art Museum Studies and Routledge Companion to Photography, and Representation and Social Justice. Meanwhile, Yining has published more than 150 articles in art, photography, and visual culture magazines in China and Internationally, including FOAM Magazine, Aperture Photobook Review, IMA, ArtForum, Art World, and China Photography Magazine.

In terms of curatorial practices, she specializes in uncovering contemporary photographic practices and weaving them within a dual vision of politics and visual culture. Yining has curated more than 40 cross-cultural exhibitions for museums, art institutions, and photography festivals in China and Europe, many of which have gained international reputations, including ‘Imaging Our Futures’ (PHOTOFAIRS SHANGHAI public program, Shanghai Exhibition Center, 2021), ‘China Imagined’ (BredaPhoto 2020, Grote Kerk), ‘Between Mountains, Hills and Lakes’ (Design Society, Shenzhen; Modern Art Base, Shanghai; Three Shadows Photography Center, Beijing; Gaotai Gallery, Urumqi), ‘The Abode of Anamnesis’ (OCAT Institute), ‘The Port and The Image’ (China Port Museum, 2017/2019), and ‘A Fictional Narrative Turn’ (JIMEI × ARLES International Photography Festival, 2016). She was the winner of the OCAT Institute’s inaugural ‘Research-based Curatorial Project’. She was nominated for the 14th AAC Art China ‘Curator of the Year Award’ for her research project exhibition.

Notes

1 The Chinese Photographic Society, abbreviated as Huashe, was founded in Shanghai in early 1928 by Lang Jingshan, Hu Boxiang, Zhang Zhenhou, Chen Wanli and other pioneer photographers. It was one of the most influential photographic art groups in China in the 1920s. The goal of the society was to study the art of photography, with the newspaper and business sectors as its main clients. It held public exhibitions of photographic art for the society and allowed all the exceptional work of interested photographers to be exhibited, and it also collected works from the whole country. The response to the society was great, and it positively and significantly increased the number of photographers and promoted photography art. The Huashe also edited and published Tianpeng 天鹏 (The China Focus) and Zhonghua sheying zazhi 中华摄影杂志 (The Chinese Journal of Photography), two early Chinese photography publications.

2 See Shi Su (Citation2016), Dongpo Inscription, Picture of the Misty and Rainy Indigo Field (Lantian yanyu tu).

3 See Shi Su, Two Poems on the Broken Branches Painted by Governor Wang in Yanling.

4 The origin of painting and calligraphy is an essential subject in the history of art. The first volume of Zhang Yan Yuan's Famous Paintings through the History of the Tang Dynasty describes the origin of painting and calligraphy in detail, explains the concept of ‘painting and calligraphy as one body’, and argues for the edifying function of painting.

5 Under the influence of Taoist doctrine during the Wei, Jin, and North and South Dynasties, the art of painting saw a new development, with the emergence of full-time literati painters, significant improvements in painting techniques, a systematic art theory—the theory of painting—and a great degree of integration between Chinese and foreign art, leading to significant contributions to the art of painting in later generations and leaving a rich legacy in the history of Chinese painting. Personal discussion on Wei Bi’s style between Zhang and the author, 14 March 2022.

6 In Roland Barthes’s The Rhetoric of The Image, he notes that almost all images in all contexts are accompanied by some sort of linguistic message. This seems to have two possible functions; h anchorage refers to images that are prone to multiple meanings and interpretations. Anchorage occurs when text is used to focus on one of these meanings, or at least to direct the viewer through the maze of possible meanings in some way (Barthes Citation1977, 156–157).

7 For more about Li Lang’s 1974 project, see ‘Picturing Histories: Historical Narrative in Contemporary Chinese Photography’, in The Abode of Anamnesis (He Citation2021, 33–35).

8 See He Bo’s reflection on his previous work, ‘Perhaps the most appropriate is to touch but not to be touched’, Jiazazhi, 17 February 2022, available at https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/m2SJK-sLdDXThkYye-Y4tw, accessed March 10, 2022.

9 See He Bo’s work statement on ‘Wish You Happy’, private material from the artists, 2022.

10 For a more detailed introduction to the book, see He’s essay in Aperture (#16) in 2019.

11 See Chen Zhe (2016)’s statement on her work ‘Study of a Poem by Rainer Maria Rilke’, from the Towards Evenings series, available at https://zheis.com/C2-Study-of-a-Poem-by-Rainer-Maria-Rilke, accessed August 24, 2022.

12 Yang Yuanyuan used this expression on a talk during the exhibition ‘The Abode of Anamnesis’ at OCAT Institute Beijing on 4 May 2019.

13 For a more detailed elaboration on Yang Yuanyuan’s ‘At the Place of Crossed Sights project’, see ‘Picturing Histories: Historical Narrative in Contemporary Chinese Photography’, in The Abode of Anamnesis (He 2021, 55–62).

References

- Barthes, Roland. 1977. ‘The Rhetoric of Image’. In Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 32–51

- Burgin, Victor. 2018 [1975]. The Camera: Essence and Apparatus. London: MACK.

- Chen, Zhe. 2016. Study of a Poem by Rainer Maria Rilke, https://zheis.com/C2-Study-of-a-Poem-by-Rainer-Maria-Rilke, accessed March 5, 2022.

- Chen, Hsueh-sheng. 2015. Forgotten Art Photography of Republican China 1911-1949. Taipei: NEPO.

- Chen, Shen, and Xijin Xu. 2011. A History of Chinese Photography 中国摄影史. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company.

- Chiocchetti, Federica. 2021. “The Wonderous Life of Photo-Texts.” Foam International Photography Magazine 60: 21–27.

- De Saussure, Ferdinand, Charles Bally, and Albert Sechehaye. ed. 1986. Course in General Linguistics. Chicago: Open Court.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1978. Writing and Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- He, Bo. 2022. “Perhaps the most appropriate is to touch but not to be touched”, Jiazazhi, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/m2SJK-sLdDXThkYye-Y4tw, accessed March 10, 2022.

- He, Yining. 2019. “Bees & The Bearable: Yining He on Chen Zhe”, Aperture, The PhotoBook Review #016, Spring 2019, 28.

- He, Yining. 2021. The Abode of Anamnesis. Beijing: China National Art Publishing House.

- Liu, Mia Yinxing. 2015. “The Allegorical Landscape: Lang Jingshan’s Photography in Context.” Archives of Asian Art 65 (1–2): 1–24. doi:10.1353/aaa.2016.0006.

- Luo, Yubin, 2021. “Li Shun: At a time, When…”, Enclave, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/zY6i_K8uJcgUDRNMmhDubA, accessed March 7, 2022.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1987. Iconology Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Mitchell, W. J. T., and Martin Powers. 2022. “W.J.T. Mitchell: Iconology 3.0: Image Theory, 1980 to the Present” (online seminar), Hangzhou: China Academy of Fine Arts, January 8, 2022.

- Mitchell, W.J.T. 1986. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1991. Peirce on Signs: Writings on Semiotic by Charles Sanders Peirce, Edited by James Hoops. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2006. Avatars of Story. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Schapiro, Meyer. 1996. Words, Script, and Pictures: Semiotics of Visual Language. New York: George Braziller, Inc.

- Su, Shi. 2016. Dongpo Inscription. Hangzhou: Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Zhang, Gaoyuan. 2021. “On the Rhetoric of the Image-Text in the Yaji Painting”, Literature and Image, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/FTkErXYFjoormJd1Co1pBg, accessed March 5, 2022.

- Zhang, Yanyuan. 2004. [847]. Famous Paintings through History. Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.