Abstract

Sir Peter Heatly is a former Scottish diver who competed in three British Empire Games and one Olympic Games. On all his journeys to major competitions, he took personal photographs and kept published material and ephemera related to his trips, which were subsequently neatly stored in albums and scrapbooks, and, until 2018, were kept by his family when they deposited the personal archive to the University of Stirling. The vernacular photography of Heatly provides personal evidence of sport mega-events from the mid-twentieth century from an athlete’s perspective. It raises questions about the value of vernacular photography, family albums, and scrapbooks for interpreting and understanding the cultural historiography of sport and how much visual culture helps make sense of the cultures of international sport during the post-war period. The article provides some critical and analytical approaches to the use of such material, questioning the motivations for their original production and archiving, as well as recognizing such photographs are not simple documents of the past with unproblematic meanings but are contingent on specific “networks of authority” and open to contested meanings.

Introduction

What can the vernacular photography of international athletes tell us about sports mega-events from the past? How can we make sense of the material and visual cultures of family albums and personal scrapbooks to inform the cultural historiography of sport? Based on the photograph album and scrapbook of Sir Peter Heatly, a former Scottish and British international diver, the article explores the potential for using snapshots of his personal and collective experience during his journey to and from the 1950 British Empire Games held in Auckland, New Zealand. The article provides some critical and analytical approaches for using such material, questioning the motivations for their original production and archiving. It also recognizes vernacular photographs are not simple documents of the past with unproblematic meanings but are contingent on specific “networks of authority” that are open to contested meanings (Edwards Citation2006, 21). The cultural meanings of vernacular sports photography are embedded in complex relationships between the visual and the material, sport history and memory, and the athlete and their audience.

Scotland has sent a representative team to every Commonwealth Games, originally the British Empire Games, since 1930. The personal collections of Sir Peter Heatly, who had a long-standing association with Scotland’s involvement in the Games as a competitive diver and administrator, contain fascinating evidence of athlete journeys across the post-colonial British Empire and emergent Commonwealth in the middle part of the Twentieth Century. Heatly competed as a diver at three consecutive British Empire Games for Scotland in Auckland (1950), Vancouver (1954), and Cardiff (1958), winning three golds medals, a silver and a bronze, as well as two Olympic Games for Great Britain in London (1948) and Helsinki (1952). On retiring from competitive diving, Heatly became a leading administrator of Scottish aquatics in the 1960s and 1970s. He also managed the Scottish Team to the British Commonwealth Games in Perth (1962) and Kingston (1966). As an Edinburgh councilor, Heatly instigated the city’s successful bid to host the 1970 Commonwealth Games and, in 1975, became chairman of the Scottish Sports Council, a role he kept until 1987. Between 1982 and 1990, Heatly was the chairman of the Commonwealth Games Federation, a factor behind Edinburgh hosting the Games for a second time in 1986 (Haynes Citation2019). The article critically examines the historiographical value of a personal photograph album, which includes a record of the journey to and from the 1950 Games in New Zealand.

Heatly was attuned to the need to imagine and judge the aesthetics of his dives. This visual knowledge and impulse to capture and collect images and newspaper clippings of his dives go some way to explain the extent of his personal photographic and media collections. The Heatly album of the 1950 British Empire Games includes 202 photographs, accompanied by 24 pages of newspaper clippings and a range of other published material from the journey, including certificates, postcards, ship menus, telegrams, letters, and team ephemera. Many of the photographs are annotated with small labels, and the album is organized in chronological order, save for the opening pages, which are reserved for a collection of ‘official’ photographs and certificates of Heatly and the Scottish team. The entire Heatly collection represents involvement in elite sport over six decades. It is a unique visual and material legacy of sport in the middle decades of the Twentieth century. When combined, the 1950 photographic album and newspaper scrapbook reflect both his personal pride in his sporting deeds and journey, as well as the imaginary or subjective intent of conserving his cultural memory for the future. In this respect, his album and scrapbook relate to what Susan Sontag (Citation1979, 69) referred to as the “clouds of fantasy and pellets of information” that photographs bring together for future viewers of such material. In other words, family albums or vernacular photography are of cultural significance because they provide “repositories of memory and as occasions for performances of memory” (Kuhn Citation2007, 284). Heatly’s collection is supplemented by the official records of the Scottish team in the minutes of the Scottish National Sports Federation, now part of the Commonwealth Games Scotland Archive held at the University of Stirling.

Heatly’s vernacular photographs capture the journey of elite athletes across the world on an ocean steamship. His album provides an opportunity to critically interpret the conventions of sporting photographs from the past, to understand the everyday context of their production and their purpose in memory-making, and to connect private memories to collective histories of sport. As Rachel Snow (Citation2012) observes, the mass production of inexpensive cameras enabled middle-class tourists to control the images made on journeys. Cheaper cameras enabled travelers to craft their own stories and identities as tourists. International athletes were afforded similar opportunities to record their journeys and create albums that reflected their experiences and identities. The Heatly albums are used here to explore inter-related theoretical debates, which include: the epistemological value of vernacular photography to the history of sport; the analytical value of such visual and material evidence to cultural histories of sport and empire, and the archival value of conserving personal photographic archives to investigate collective experience and identities in sport. The article, therefore, explores innovative ways of interpreting sport’s visual and material histories.

The 1950 British Empire Games in Auckland

The British Empire Games were strongly influenced by the British imperialist hegemony reimagined in the relationships between the center and periphery of the British Empire (Mangan Citation1998). Prior to embarking on the trip, the honorary secretary of the SNSF, George Ferguson, had written to a number of Caledonian Societies in New Zealand, making a connection with over a century of emigrant families from Scotland (SNSF 1950). Sport also played a significant role in the cultural attachments many in New Zealand fostered to maintain their Scottish heritage, with Caledonian Highland Games, tartanry and bagpipes key motifs of Scottish ancestry. In the official report for the 1950 Games, the connection between New Zealand and the anglosphere of the former British Empire was made explicitly clear:

the biggest welcome was given to the members of the English, Scottish, and Welsh teams, who arrived by steamer on a Saturday morning. These teams “from Home” had been eagerly awaited, and the reception was fully in accordance with tradition, even to the grand welcome of the pipes. (British Empire Games Federation Citation1950, 21)

So were the peoples of the Empire brought together at the farthest point in this great Commonwealth. It was a real reunion of families, races, and creeds, once again a fitting testimony to the solidarity of the Empire. Auckland and New Zealand took the visitors to their hearts, and when the home Dominion team joined the visitors at Ardmore, the family was complete. And completely happy. (21)

Vernacular photography and sport

Vernacular photography—the photography of the everyday like snapshots—is a form of photography that “permeates daily existence” (Barrett and McCarroll Cutshaw Citation2008, 8). Predominantly private snapshots and albums, vernacular images may also include public photographs sourced from published material such as newspapers, postcards, and advertizing. Before digital photography, vernacular photographs were printed and collated within albums and scrapbooks or stored as slides, often ceremonially projected at family gatherings. These visual materials can be viewed as autobiographical in nature, produced as a collection laid down like an alluvial deposit at the end of a particular life story.

The placing of photographs in an album adheres to conventions of storytelling and storage of private memories for future use. The private contents of family albums can carry particular meanings for each family member. However, when placed in a wider social context, for example, in a public archive, such materials bring wider possibilities for interpreting and understanding the social and cultural past. Martha Langford’s (Citation2001) work on ‘suspended conversation’ revealed the importance of looking at family albums as a whole, where meaning extends beyond oral communication. As Annette Kuhn (Citation2002, 153) has noted in the context of family albums: “every photograph contains a range of possible meanings, from those relating to the cultural conventions of image production to those which are to do with the social and cultural contexts in which the image was produced and is being used.” Family snapshots, regardless of what they contain, represent something emotional for the owner of such photographs and also contain “affective qualities that reach further than the individual owner” (Sandbye Citation2014, 2). As repositories of family life, photographs and family albums become “conveyances of vernacular memory” carrying the cultural evidence and meanings that are often overlooked in popular cultural histories (Pickering and Keightley Citation2015, 1).

Vernacular photography requires interpreting snapshots in a broader social context. As Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1996) and colleagues observed in their study of class distinctions in the use and meaning of snapshots in the mid-1960s, the image is subordinate to its social functions. Bourdieu’s analysis of amateur photography is highly relevant in this context because it recognizes that “the most trivial photograph expresses, apart from the explicit intentions of the photographer, the system and schemes of perception, thought, and appreciation common to a whole group” (Bourdieu Citation1996, 6). Family snapshots as visual communication not only help preserve moments from the past but also reveal how particular elements within the photograph adhere to systems of photographic convention, both in terms of the organisation of the subject matter as well as how photographs are organized, stored, and used. In thinking through the interrelationships between photography, memory, and history, David Bate (Citation2010, 255) has persuasively argued that photographs “have a sharpness and innocence that belie meanings that have far more potential significance than is often attributed to them, which means that in terms of history and memory, photographs demand analysis rather than hypnotic reverie”. Kuhn (Citation2002, 19) has also highlighted the social role in the production of albums, emphasizing “the social dynamics mapped on the pages of a photo book and arranged photographs so as to articulate their own internal experience of the family”. Conventional snapshots produce a continuing repetition of subjects and recurring themes (birthdays, holidays, family occasions, and so on), which are familiar in their “informal formality” (Kuhn, Citation2002). Vernacular photography can appear as spontaneous, improvized, and capturing the intricacy of social relations. However, snapshots also produce familiar set pieces based on generic photographic conventions.

The conventions of sports photography have begun to be analyzed afresh after many decades of academic inertia on the subject. In the context of the history of the sport and the use of photography, the ‘visual turn’ in the historiography of sport has emerged as an important form of evidence from the sporting past (Huggins and O’Mahony 2012; O’Mahony Citation2018; Hughson Citation2019; McKee and Forsyth Citation2019). The conventions of sports photography have been central to our collective memories of sport stars and sporting practices (O’Mahony Citation2018). The visual culture of sports photography includes portraits of sports stars, action shots of sports performances, the conventions of posed team ensembles, and the use of sporting tropes in advertizing. However, vernacular photography in sports has largely been ignored in sports historiography. Given the place of sport in many popular cultures and societies, this omission in academic analysis seems negligent. Sport is individually and collectively central to many people’s cultural practices and identities. There exists an abundance of family photographs with sporting themes. They include informal snapshots of school sports days and amateur sports, the snapshots taken by fans at sporting events, and the snapshots captured by elite sports people and their families in the context of training, travelling, and performing in sport.

The Sir Peter Heatly photographic album and scrapbook provide new insights into both the visual self-representation of the sporting past and its value in interpreting his specific cultural memories of sport and travel. Nevertheless, critically reviewing the Heatly album presents an interpretive problem. Should the focus be on his private narrative of his travels to the Games in New Zealand, or can we regard his vernacular photographic album as an object for historical, sociological, and cultural inquiry? Aesthetically, what makes his snapshots familiar and yet extraordinary in terms of their representation of an elite athlete in post-war Britain? What does his visual story of travelling to the British Empire Games in Auckland tell us about his experience of people, places, objects, and events? In attempting to address these questions, it is important to recognize that the Heatly album is a form of social and emotional communication with a phatic function (Blanco 2010). It can be interpreted as a way of understanding his sporting life or the visual communication of his emotional experience. His photographs also document sociological aspects of his daily life and the collective experience of his journey to New Zealand, not available from other historical sources. The Heatly snapshots link people to people, people to places, people to objects, and people to events. As a material object, the album also has value to his family linked to feelings of memory, nostalgia, and the melancholia of loss following his death in 2017.

Vernacular themes of the Heatly photograph album

The album is more-or-less organized chronologically in the conventional style of many family albums, representing a visual retelling of a holiday or journey in the “natural order of social memory” (Bourdieu Citation1996, 53). Here, the album operates much like a diary or journal. The album serves to provide visual evidence that embellishes the official record of the Scotland team’s travels to Auckland, with a particular focus on people, the nature of travel, places visited, and the preparation of sporting performance. Within this conventional narrative approach to the journey, other cultural themes begin to emerge from the album, which provides more nuanced insight into the experience of athletes travelling to a major sporting event on the other side of the world. There are both formal elements: capturing the various teams competing in the Games, as well as more informal elements; capturing friendships, tourism, and recreational fun, which tell us something about camaraderie among competitors, the domesticating of exotic places, and the social freedom enjoyed by elite athletes that contrasted with the material circumstances of life back home. “With photographs”, David Bate has argued, “memory is both fixed and fluid: social and personal” (Bate Citation2010, 255). Heatly’s snapshots give witness to his collective experience of an international sporting event. At the same time, his photographs produce a very personal visual memory, taken from his perspective and curated for his family and friends.

In a similar vein, and following the work of Langford (Citation2001), Mette Sandbye (Citation2014, 12) argues that the photograph album is “a highly social device actively constructing not only memories but also personal cosmologies and human relations in the presence of its making”. In this context, the Heatly album provides different ways to understand its material and visual significance, which will be explored through four vernacular perspectives. The first perspective analyses the album as a material object, which draws attention to its relational and affective qualities. Over time, the album produces an auratic quality as an item evoking the past. This also triggers strong emotive meaning for family and friends and affective connections for future viewers of the album. The second perspective approaches the album as a form of experiential travelogue of an athlete, which develops narrative themes of post-war austerity, travel, and sport through vernacular photography. This perspective also enables an examination of a sense of social freedom experienced by the athlete as a tourist, with both performances of tourism behavior and the use of vernacular photography to capture the camaraderie of sport and athletes in the context of the material and social constraints of the period. This latter category also opens up observations about gender and sport, as Heatly’s photography captured the experiences of female athletes travelling and competing in international sports, reflecting emerging forms of “cosmopolitan sociability” for some women in the immediate post-war period (Spencer Citation2017). The third perspective places Heatly’s journey in the context of post-colonial legacies of British imperial power and the ‘webs of Empire’ (Ballantyne Citation2015); in 1950, this connected competing nations of the British Empire Games culturally and politically in complex ways. The fourth perspective explores Heatly’s unique position as a privileged witness to competing in the 1950 Games, representing sport through particular formal and conventionalized forms of vernacular photography. These are by no means the only themes that might be read from Heatly’s album, but they are the prescient ones in thinking through how vernacular photography can provide visual evidence for the cultural history of the sport, in this instance, the Scotland team’s participation in the British Empire Games in 1950.

The Heatly album as an auratic and affective object

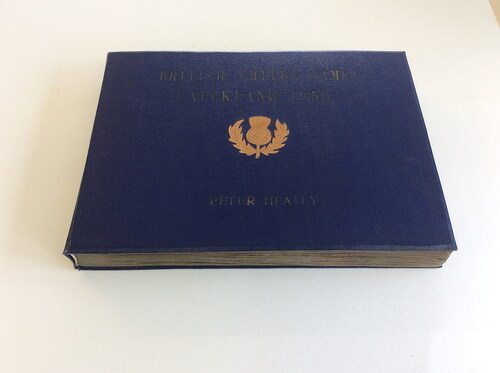

Family photograph albums represent something emotional for the owner (Sandbye, Citation2014). The cover design and construction of the Heatly album provide initial clues to the personal value and significance of the collection (). The album has a blue A4 landscape hardcover with the image of a gold embossed thistle—the emblem of the Scottish team—and the title ‘BRITISH EMPIRE GAMES AUCKLAND 1950’ in faded embossed gold lettering. At the bottom of the album cover is the name ‘PETER HEATLY’, denoting its owner. The album looks substantive, roughly 4 cm in thickness, and its cover works indexically, leaving little doubt about the event it refers to, its Scottish national heritage and curator. The album has an aged patina, denoting its biographical and emotional value for Heatly’s family. Elizabeth Edwards has referred to this dimension of vernacular photography as its aura or “auratic” quality, where an album literally holds a “scent of the past” (Edwards and Hart Citation2004,11). The Heatly album creates this auratic quality through a sense of being a personal collection, kept over many decades and cherished in the home as a representative of his sporting experiences and achievements.

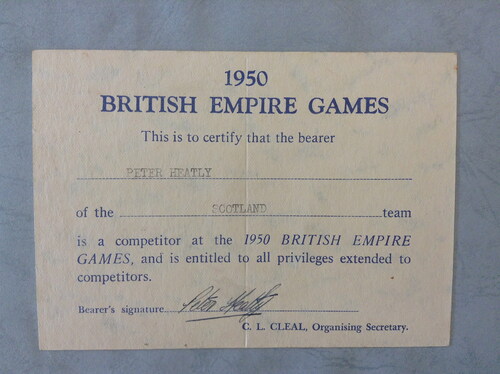

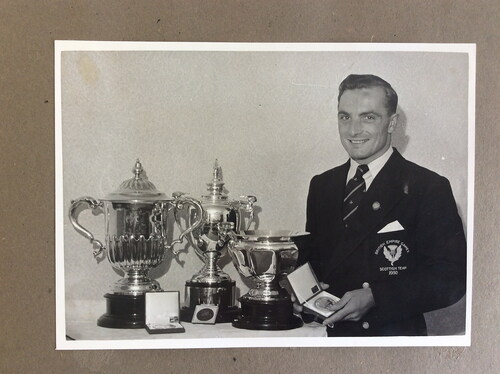

The sequencing of photographs provides a clue to the significance Heatly placed on his photographs as the album curator. The front matter of the album includes formal documentation and professionally taken photographs to denote both the official nature of representing Scotland and a record of his achievements at the Games. For example, pasted on the inside leaf of the album is a certificate (), bearing notice that Heatly “is entitled to all privileges extended to competitors” as an athlete of the Auckland Games. The first photograph in the album () is professionally taken and shows Heatly in his Scotland team blazer and tie, holding his diving gold medal from Auckland in its presentation box. Compositionally, it is a conventional photograph of a sporting figure alongside the spoils of their competitive victories (O’Mahony Citation2018, 63). He is standing beside a table on which three trophies are placed: the British high board trophy, the Pete Desjardens one-meter board trophy, and the British three-meter board trophy. His silver medal for the three-meter springboard and a bronze commemorative medal for Auckland are also on the table. We know the details of the trophies and medals in the image because it appears again in Heatly’s newspaper scrapbook with a full explanatory caption (Heatly Citation1950). What is unknown is which newspaper the photograph appears in, but it was clearly taken on Heatly’s return from New Zealand at a gala event held by the Scottish Amateur Swimming Association in honor of his achievements in 1950.

The amplification of this image () at the front of the photograph album relates to its special meaning for Heatly himself, symbolizing his pride and sense of personal achievement following an especially successful year of diving. For readers of the album, the affective quality of the image invites us to be impressed by Heatly’s deeds, both representing Scotland and his competitive success. From its opening page, the ordering of the Heatly album is not a straightforward memorializing of key events; it is selective, a representation of his experience of the Games with the subjective intention emphasizing on its personal meaning and significance for Heatly and its affective quality for those viewing the album.

The Heatly album as a travelogue of international sport

Snapshots present the high days and holidays of family life, but in 1950, as the country endured the privation of post-war austerity, international travel for the vast majority of people would have been a limited luxury. For the young Scottish athletes, to be away from home travelling through tropical climates to far-off lands would have been an exceptional experience. The Scotland team left Southampton on 16th December 1949, and their journey to Auckland would take 1 month and 5 days. The team spent 5 weeks in New Zealand before arriving back in Southampton on 18th April 1950, a total of 113 days of travel. For athletes, the trip would have been multirelational in terms of their identities in any given context: they were dedicated elite athletes; they were representatives of their ‘home’ nation; they were tourists; and they would have maintained an everyday domestic existence. These identities were not mutually exclusive, but each would have taken more precedence contingent on their social circumstances. In terms of Heatly’s photography, aspects of each multirelational mode are represented in his album. His snapshots provide a unique insight into the variety of experiences athletes would live through travelling to major international sporting events during the 1950s. Therefore, Heatly’s album carries some unique historical sources of international athletes behind-the-scenes, backstage, bearing historical witness to the drawn-out times of travel and exploration that occurred before regular chartered international flights became the norm. Such lengthy journeys to compete in international sport had become the norm of touring teams from the UK and in football, cricket, and rugby, and following the Olympic Games, the British Empire Games represented a further expansion of a particular imperialist process of globalization in sport. The snapshots are further enhanced by Heatly’s ephemera of the journey, from ship menus to programs from on-board theatre shows, letters from home, and postcards of places visited. The scrapbook of memorabilia from Heatly’s journey provides a curated assemblage of this published material, representing another visual expression of his trip, complementing the photography album.

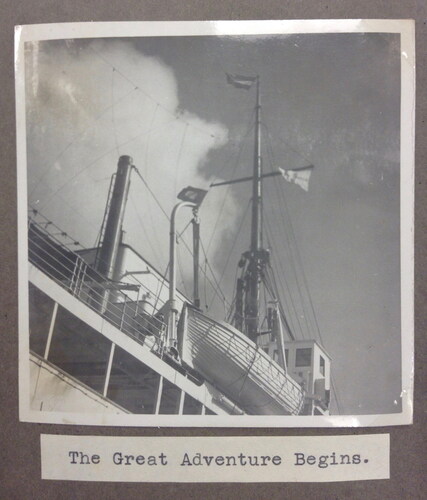

Family albums of holidays are both incredibly specific to the family who experienced the holiday but also codified in such ways that are commonplace and familiar to wider audiences. While Heatly’s snapshots of his travels to New Zealand are not the conventional family travelogue, they do share a similarity in how travel and the exoticness of new places are recorded, presented, and memorialized by him for a future family audience. The album includes an image of the SS Tamaroa taken as Heatly boarded the ship. The annotation “The Great Adventure Begins” () places emphasis on the exceptional nature of the trip. The act of photographing the journey to and from the 1950 Games is, therefore, partly a means to share experiences at a later date with friends and family, displayed in an album.

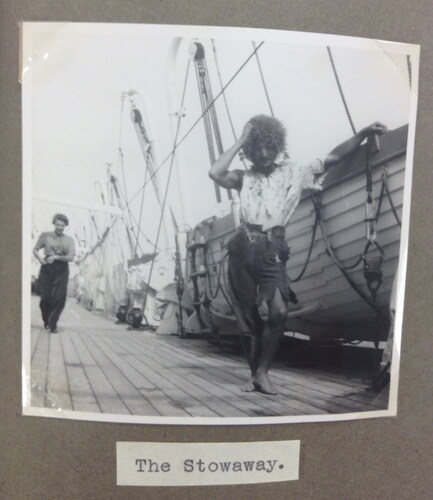

The voyage itself provided opportunities to capture the mundane on board the Tamaroa. The boat trip clearly included extended periods of relaxation and possibly boredom, which were occasionally broken by novelty and the whimsical. Snapshots of athletes sunbathing or of Heatly himself leaning casually on the ship rails in his swimming trunks and sun hat (“Sunbathing in the Atlantic”) or holding aloft a flying fish that had come on the deck (“The Fish that flew too high”) carry familiar tropes of lazy sunny days on holiday. The boredom of travel was relieved by fancy dress for entertainment, including Heatly dressed as “The Stowaway” () for the maritime tradition of “King Neptune’s Court”, an initiation right for those crossing the equator for the first time. Even during some of the training stopovers, such as Curaçao in the Caribbean, light-hearted snapshots of the Scottish female swimmers around a fountain in the pool with the caption “The Water Babies” reflect the amount of casual fun the group of athletes had on such tours. Posed snapshots, always capturing smiling faces, may well mask the more downbeat, miserable or social strains of living with other athletes for 15 weeks, but there are a few images that capture more sober moments of athletes quietly reading their mail from home.

Heatly’s albums partially document the sociological aspects of the daily lives of travelling athletes. They are partial in the sense that Heatly chose to capture certain aspects of daily life on board, which are then ordered and labeled by him in the album to give a particular impression of what his journey was like and meant to him. At times, snapshots of collective recreation on board reveal moments of revelry and camaraderie, which would have built lifelong memories and friendships. At others, the snapshots reveal quieter moments, sunbathing on deck for instance, or of Heatly himself in a relaxed or reflective mood reading letters from home. The composition and selection of images flit between modes of Heatly: the athlete and the tourist, in some cases operating across both subject positions. This blurring of subjective boundaries reflects the particular experience of travelling athletes who at one and the same time have a dedicated sporting purpose and are experiencing new material and emotional ways of being in the world, encountering, looking, and making sense of new places as a tourist. Where athletic routines of training operated as anchor points, domesticating the travelling experience, the lengthy period of travel brought new and quite possibly fantastical experiences: being away from family for several months; acclimatizing and enjoying the warmth of tropical climates; enjoying full-board services on ship, including food which may have been rationed at home; corporeal experiences of new places with different cultures to their own; meeting people from different nations and cultures.

Bærenholdt et al. (Citation2017, 2) have observed how the growth of tourism in the mid-twentieth century was part of a process that incorporates “mindsets and performances that transform places of the humdrum and ordinary into the apparently spectacular and exotic”. Vernacular photography ‘tamed’ the exotic by overcoming the insecurity of the foreign by placing familiar people in the unfamiliar or ‘exotic’ context. The organization and labelling of images in the Heatly album help anchor the meaning of many of the snapshots, capturing familiar faces of fellow British athletes presenting the conquering of the exotic to family and friends back home. One of the most salient ‘exotic’ themes in the album relates to post-colonial links to places and cultures, which would have been new to most of the young athletes on board.

The Heatly album as a connection to the ‘Webs of Empire’

Prior to leaving London, the team met the New Zealand High Commissioner at Waterloo Station, a moment captured in Heatly’s scrapbook (Heatly Citation1950). These official meetings between competitors and state representatives were important opportunities for promoting the Games, but more crucially, was an expression of the “webs of Empire” (Ballantyne Citation2015) in which sport played a central role in the complex interrelationships of a “British world system” between former colonies. As Davis (Citation2013) has explained, post-war Britain became “steeped” in the sense of an Empire, then being redrawn as The Commonwealth. The Empire “was an integral part of the country’s politics, values, thoughts, and ideas and how it saw itself at home and in the world” (Davis Citation2013, 8). As the Scottish team embarked on its long adventure to New Zealand, such thoughts may well have been widely held and felt among its members. Scotland had a long history of imperialist influence through trading routes, education, religion, and, most crucially, through culture in which sport was most prominent (Mackenzie and Devine Citation2016). The introduction of routes of the Shaw Saville and Albion line steamships to New Zealand in the 1930s had boosted connections between the two countries (The Times 9 November 1932, 20), and by 1950 more than 60% of immigrants to New Zealand were from the UK (Ongley and Pearson Citation1995).

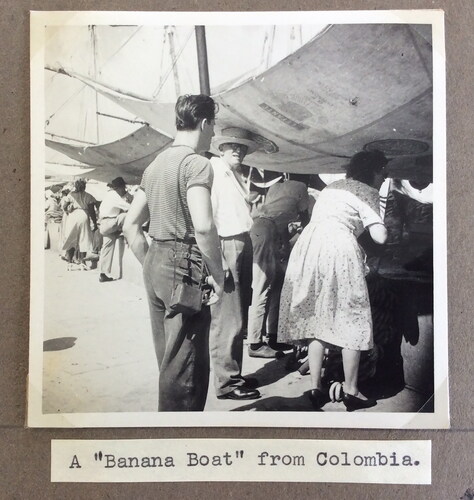

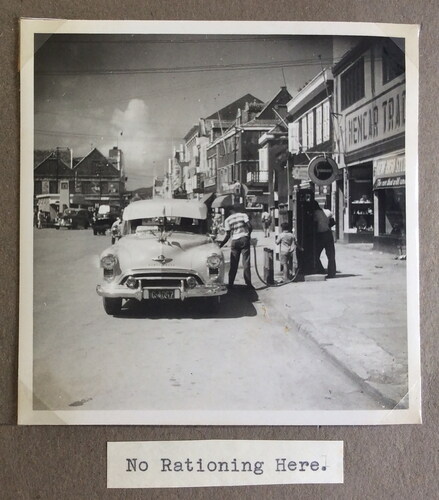

Heatly’s album contains a number of conventional tourist tropes in snapshots, which relay a sense of either global difference or similarity in both the subject matter and how they are labeled in the album. The album reveals glimpses of the various stop-overs on the route to Auckland, including the former Dutch colonial territory of Curaçao in the Caribbean where the Tamaroa would have refueled at the port of Willemstad. The labelling of an image of a quayside market and banana stall in Willemstad () draws on imperial tropes to describe the scene as “A ‘Banana Boat’ from Colombia”. As rationing of fruit and vegetables continued in post-war Britain, bananas connoted luxury and the exotic pleasures of a distant paradise. As a crop, they were heavily associated with plantations, oppressive labor conditions, and international trade of ‘tropical’ fruit, from where the phrase “banana boat” had its lineage (LeGrand Citation1984). Heatly’s visit to Curaçao makes further reference to domestic differences with the island alongside a snapshot of a large American car () being refueled with the comment “No Rationing Here”. The reference to British austerity contrasts with the sense of abundance on the Caribbean island. Snapshots of Scots in kilts, either in Curaçao or New Zealand, create further cultural distinctions in the album, most notably when contrasted with images of host populations in traditional dress. The trip to Auckland would have been both an adventure into the unknown observing the exotic, as well as an opportunity to perform their Scottish identity, wearing kilts and sharing Scot’s bonhomie with their foreign hosts.

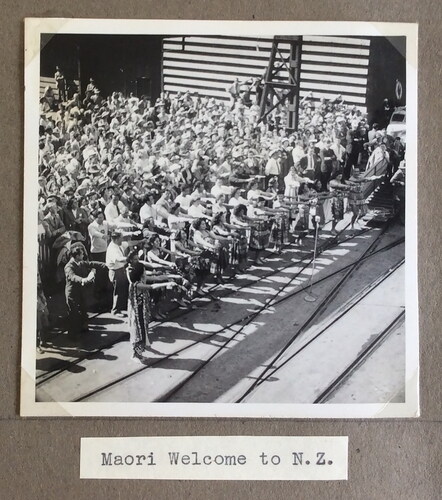

Visual evidence of the anglospheric bonds between British athletes and their hosts can be found in the Heatly album. The snapshots of the Scotland teams’ arrival in Auckland provide evidence of the reported 5000 local residents welcoming the Tamoroa (Ryan Citation2014, 417). Athletes were welcomed by a Māori pōwhiri, a moment captured by Heatly from the perspective of the ship at the quayside (). Heatly’s snapshot shows both Māori and white officials in shirt and tie with arms raised performing the welcome dance in unison. Heatly’s album reveals a further engagement with indigenous Māori culture with images of Scotland team members attempting to imitate the haka or dressing up in ‘native’ dress in warrior-like poses. Ryan (Citation2014, 424) suggests that from the outset, there was a concerted effort by the host nation to showcase New Zealand as having impeccable race relations. The appearance of racial harmony, through the co-option of the haka in sport and official welcomes, served to reaffirm the imperialist belief that the ‘civilizing mission’ of the Empire was complete (Mangan Citation1998). As Tony Hughes-d’Aeth (Citation2001, 87) has argued: “Indigenous people served an important function in defining the modernity of the colonizing population”. Its use here in an international sporting context further emphasizes the process of how Māori customs became a global symbol of New Zealand identity through sport (Jackson and Hokowhitu Citation2002). However, such claims of racial harmony were contradicted by the lack of Māori athletes in the Games (Ryan Citation2014, 424).

Other images of a street parade reflect the predominant urban white population of Auckland, which had deep historical ties to Britain and British culture. Heatly’s album shows a naval guard of honor marching down the center of the road from the quayside and, in another, a Caledonian band in formal tartan dress playing pipes and drums. The Scotland team arrived wearing kilts, and one snapshot shows swimmers Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Turner and Margaret Girvan holding large bouquets that had been presented on the quayside. Collectively, these snapshots from Heatly’s album capture the dynamic nature of the arrival; several of the images are caught ‘on the hoof’ and appear framed in a hurry. But they do capture the scale of the welcome the British teams received, and a sense of how significant their arrival appeared to be for the New Zealand hosts. The linkages between the imperial center and colonial peripheries resonate within these images. As Greg Ryan (Citation2014, 246) points out, “1 week in Auckland in February 1950 confirmed an attachment to Britain and traditions of Empire that receded only gradually from the 1960s”.

The Heatly album as sporting witness

Heatly’s album provides a reservoir of visual memories that convey both the collective experience of the Scotland team as well as a personal perspective on the significance of places and people he engaged with both before, during, and following the Games. In some cases, the photographs reaffirm ‘official’ records of the Games, but in other ways, provide competing or problematic accounts of his experiences. The official record of the travelling party from Scotland, as well as newspaper reports of the team, have conflicting information as to the final size of the touring party, which is reported as between 18 and 21 in different sources. However, Heatly’s album contains a team photograph from the athlete’s village clearly showing a party of 23, with 14 male competitors, 4 female competitors, the team manager and his wife, the swimming judge and his wife, and the boxing coach. The team ensemble is a long-established convention of team photography and ensures every team member is represented, usually wearing a formal dress (O’Mahony Citation2018). Symmetry is frequently important in such images for aesthetic balance, and this is perfectly illustrated in the image of the Scottish team with the female members all seated in the front row, perhaps symbolic of towering male dominance behind.

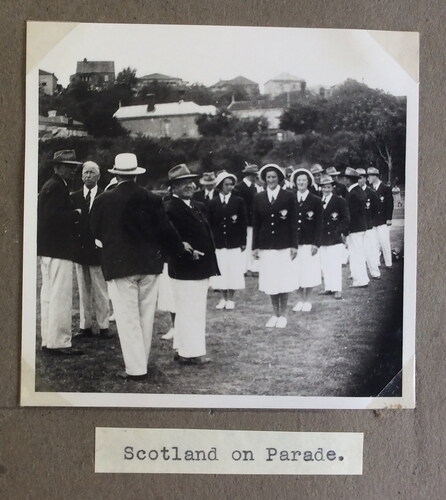

Heatly’s album contains a number of similar formal team ensembles but with a twist of informality. These include the team arriving for the opening ceremony (), as well as informal team ensembles captured by Heatly during the sailing to New Zealand. In these team ensembles, most athletes eschew formal clothing; in some cases, male competitors are topless in the heat of the tropical sunshine.

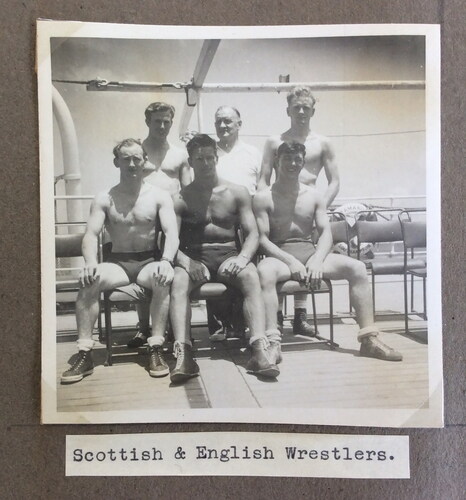

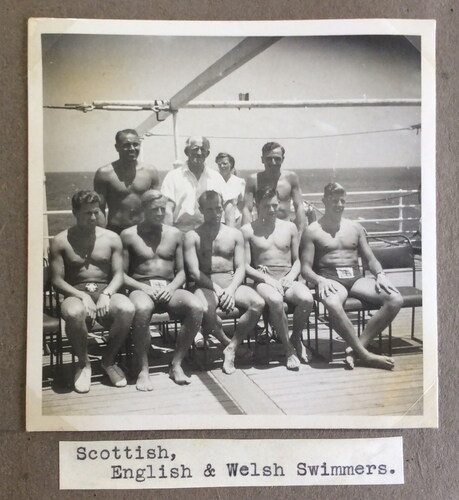

The album has two pages of team snapshots, six on each, reflecting an aesthetic of informal formality, where small groups are collectively photographed in a formal team pose, sometimes wearing team clothing, but unlike official photographs, athletes were casual in demeanor. Most of these team snapshots ( and ) are labeled in the album and include images of the “Scottish and English Wrestlers”, “England’s Women Athletes”, “England’s Cyclists” all standing behind a bicycle, “Scottish, English and Welsh Swimmers”, “The Nigerian Team”, “England’s Men Athletes” and “Scotland Again”. There is also a large collective photograph of over 40 athletes from all nations assembled in five tiers with two ship officers sitting at the center. The inclusion of athletes from other nations is suggestive of the collective experience and camaraderie of the British teams on board, many having competed together in the British team at the 1948 Olympic Games. The significance of this collection of team snapshots is Heatly’s curation of them. Their importance to Heatly is clearly displayed in the album as memorials to the national and sporting allegiances of those who traveled on the Tamaroa.

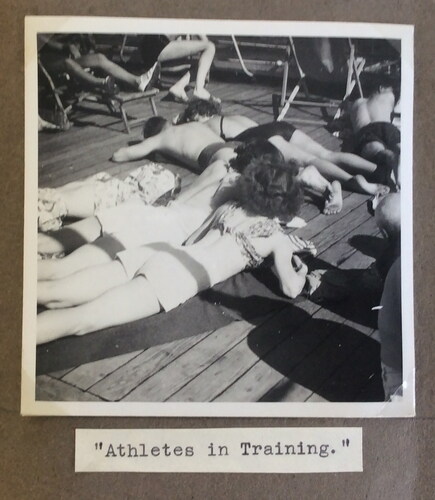

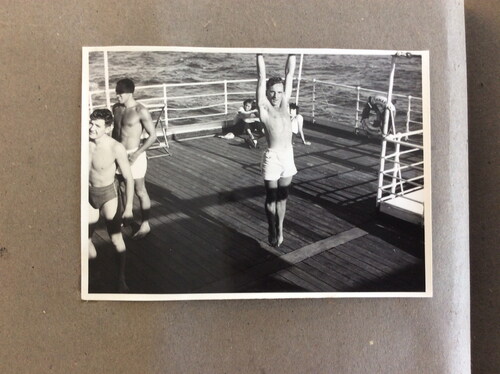

Another dominant sporting theme in the Heatly album is training and practice. Travelling on a steamship for 5 weeks prior to competition is not the ideal preparation for any athlete. To ensure the Scottish team remained fit while on board, there was an established routine of exercise and tailored practice to suit the needs of each sport. Heatly’s official report on the journey from the perspective of the swimmers provides an insight into the training policy but also highlights the ridiculous constraints most of the aquatic team faced while on board. Training on board the Tamaroa was restricted to physical training drills led by fellow Scottish swimmer Albert ‘Bert’ Kinnear, who had qualified in Physical Education at the Royal Air Force Physical Training School at Loughborough College in 1943 (Foden, Citation1963). Training classes were held three times a day in temperate climates and twice a day in tropical climates. Heatly’s view was that those who partook of Kinnear’s sessions reaped the benefit in competition, stating: “It is a fact that in general those swimmers who gave whole-hearted support to the P.T. classes acquitted themselves well at the Games” (Heatly Citation1950). Heatly’s comments barely conceal his criticism of those swimmers and other athletes who did not avail themselves of the classes, and his album carries examples of both active engagement in training as well as ironic comments on photographs that captured more slothful behavior on the ship, particularly sunbathing ().

Training for swimmers and divers was particularly tricky. After the first week of the journey, a makeshift ‘swimming tank’ was constructed at the stern of the ship, which was made of wood and tarpaulin; the tank measured 18 feet by 12 feet, enabling swimmers “to practice leg actions and, to a limited extent, starts and turns” (Heatly Citation1950) ().

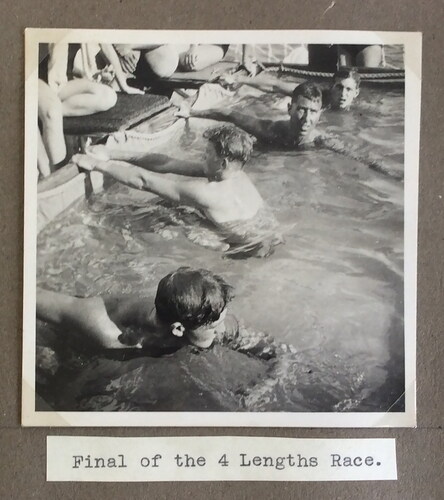

From the evidence in the Heatly album, the tank was well-used and became the hub of as much social activity as swimming practice. The album contains a snapshot of the tank being used by swimmers, with the water frothing like a cauldron as the swimmers disturb the small volume of water. In another series of images, Heatly has a snapshot of female swimmers and a crowd of fellow passengers overlooking what is labeled “The Swimming Gala”. On the same page of the album is another gala image captioned as the “Final of the 4 Length Race” with close-up images of four male swimmers readying themselves for a start. These images provide evidence of how touring sports teams found innovative ways to keep fit and prepare for future competition. For Heatly, the lack of any facility to practice diving led to using a steel girder at the stern of the ship to hang from and practice his tucks and leg lifts, thereby conditioning key arm, stomach, and leg muscles he would use when diving ().

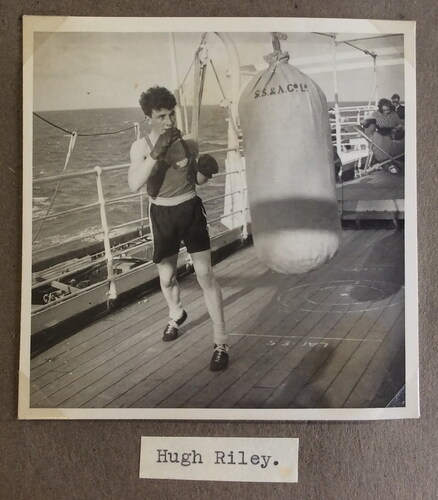

For others in the Scotland party, also innovated spaces to practice the specific conditions of their sports. The boxers could use skipping ropes, and a heavy punchbag was strung from one of the ship’s girders (). The Scottish boxers had their own trainer, Ken Shaw, a 29-year-old Scottish professional heavyweight champion between 1945 and 1950. Shaw had initially not been included in the Scottish party, but following protestation from the Scottish Amateur Boxing Association, he was approved to travel at the last moment. A subsequent newspaper report pasted in the Heatly Scrapbook revealed why: Shaw and his parents had decided to emigrate to New Zealand. Post-war emigration of Scots to the former imperial dominions of New Zealand, Australia, and Canada had been reinvigorated following the Second World War as many sought a new life away from Britain’s bomb-scarred cities and economic crisis. Shaw’s decision echoed many Scots who traversed the world for new employment opportunities.

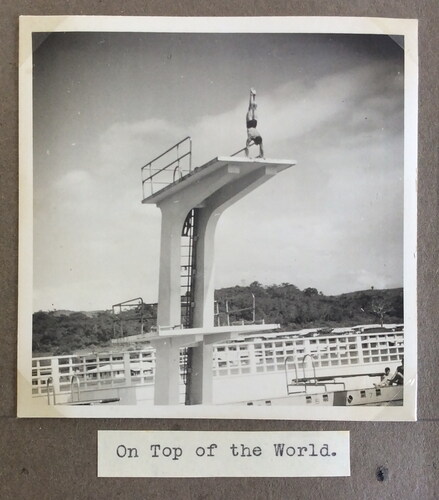

Athletes did have an opportunity to practice and train properly when the Tamoroa stopped over at Panama City, and the Heatly album provides snapshots of him practicing his dives from a 10-meter platform (). These images not only reveal the impressive height and technique of his dives but also provide examples where Heatly is the subject of the snapshots in his album and not the photographer. We have no way of knowing who may have taken the shots, but in a way, it reiterates the family nature and friendships developed among the Scots team as they surely evolved over a long period away. Therefore, the stop-off in Panama includes a number of snapshots of Heatly with fellow Scottish team members in the pool, as well as the leading female diver Edna Child of England on top of the high board.

While newspaper clippings and illustrated magazine features of the Games, which are collected in Heatly’s scrapbooks, do provide images of him diving competitively in Auckland, the photographic album does not. There are snapshots of the Auckland swimming pool and diving platform. The images reveal the packed stands of the 5000-seat outdoor Newmarket Olympic Pool, as well as the busy flurry of competitors and officials. Built in 1940, it was the first 50 m pool in New Zealand. The only snapshot of Heatly in the arena shows him collecting the gold medal for the 10-meter-high board, clearly a moment of personal pride. The snapshot was probably taken by a Scotland team member with Heatly’s camera. Heatly also has a snapshot of 16-year-old Helen Orr Gordon receiving her gold medal for the 220-yards breaststroke, which she won in record time. The perspective of the photograph of Gordon, close up from the left side of the medal podium, is very similar to a press photograph of the same moment published in a New Zealand sports magazine. This suggests Heatly, as a competitor, gained unrestricted access to capture the momentous event for his young teammate, a level of access unafforded to spectators at the pool. The affective power of such close-up-and-personal imagery of a significant event in the career of Gordon is also of great historical value for the viewer who, through this image, gains access to a significant sporting moment from the past. While Sontag’s (Citation1979, 71) suggestion that “A photograph is only a fragment, and with the passage of time its moorings come unstuck” may well apply to many snapshots, in this instance, the snapshots of a well-recorded moment of the past has both maintained its mooring to a key event, and arguably gains more affective power as it enlivens the biographical narratives of both Gordon as subject and Heatly as observer of the event.

One final dimension of the album in the context of the sporting events is the ceremonial processes at the Auckland Games. Heatly’s album provides a range of perspectives on the Scotland team’s experience of ceremonial events, both in terms of the official welcome to the athlete village, where team flags were raised with the accompaniment of a highland military band, through to the opening ceremony of the Games where Heatly was part of the procession into the Auckland stadium. Such images provide an informal back story to such events, providing snapshots of the Scotland team in their formal dress arriving at Eden Park, milling around awaiting their call to enter the stadium, and once inside, a close-up image of Scotland flag bearer and team captain Duncan Clark alongside Helen Orr Gordon holding the Scotland placard. All of these snapshots provide a different perspective to the event that was represented in official and news coverage of the time, providing a pro-filmic personal account of a major sporting event from the perspective of those involved.

Conclusion

The Heatly album and scrapbooks of his journey to the 1950 British Empire Games in Auckland can be interpreted as valuable sources of social and affective communication about life as an international sport competitor in the immediate post-war period. They help document social and cultural aspects of the daily life of a travelling athlete and those of his compatriots, as well as the response of those who hosted the event. Crucially, the album of vernacular photography provides access to the daily lives of athletes, unattainable from other historical sources.

Part of the analytical task of interpreting such snapshots is to unlock memories and identify the intention of Heatly in taking the photographs, their meaning to him, and how the performance of the subjects in the snapshots adheres to particular social and cultural norms. Heatly’s creation of the album and its material significance relates to both the affective meanings associated with the production of the album and its contents, as well as its auratic afterlife in the home and archive. This emotional meaning and response to the album provide important ways in which popular cultural historians can explore the significance of visual archives and their potential value for a nation’s cultural heritage.

Heatly’s vernacular photographs also reveal an “informal formality” identified by Kuhn (Citation2002), which echoes the official setup of team photography, documentation of fellow athletes in training and competition, which provide a narrative of the corporeal social performance of being a tourist and athlete in periods of relaxation. Some of the sub-themes of these narratives relate to the post-Imperial experience of British travelers to former colonies, the freedoms of representative athletes away from the economic and social constraints of British society, particularly for female athletes, albeit under a watchful eye of team chaperones.

The 1950 Games did much to persuade the New Zealand population of the value of the strong ties with the British, and Ryan’s research on the motivations of the hosts places a strong emphasis on the sense that “the tone established in Auckland was unequivocally amateur and seemingly determined to downplay sporting competition in favor of an emphasis on familial bonds of Empire” (Ryan Citation2014, 417). Heatly’s album, through the lens of a British touring athlete, provides evidence of the resonance of these connections and how they were played out in the immediate post-war context of sport and the Empire. His photographs reveal some of the lingering racism of Empire, as well as the privileges and celebration of athletes from the British homeland that white New Zealanders expressed in hosting the Games. Ultimately, in the creation of the vernacular album, Heatly produced a collection of images that provide unique insights behind the scenes of international travel and competition that professional sport photojournalism rarely provides.

Disclosure Statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard Haynes

Richard Haynes is Professor of Media Sport, in the Division of Communications, Media and Culture, University of Stirling. His research focuses on the relationships between the media and sport. He is author of BBC Sport in Black and White (Palgrave 2016) and Stream The Rivalry: Sport in the Platform Age, the Case of F1 (Peter Lang 2024).

References

- Bærenholdt, Jørgen Ole, Michael Haldrup, and John Urry. 2017. Performing Tourist Places. London: Routledge.

- Ballantyne, Tony. 2015. Webs of Empire: Locating New Zealand’s Colonial Past. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Barrett, Ross, and Stacey McCarroll Cutshaw. 2008. In the Vernacular: Photography of the Everyday. Boston: Boston University Art Gallery.

- Bate, David. 2010. “The Memory of Photography.” Photographies 3 (2): 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17540763.2010.499609

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. Photography: A Middle-Brow Art. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- British Empire Games Federation. 1950. 1950 Auckland Games Official Report. Auckland: British Empire Games Federation.

- Davis, Richard. 2013. “Perspectives on the End of the British Empire: The Historiological Debate.” Cercles 28: 1–25. http://www.cercles.com/n28/davis.pdf.

- Edwards, Steve. 2006. Photography: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Edwards, Elizabeth, and Janice Hart. 2004. “Introduction: Photograph’s as Objects.” In Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, edited by Edwards, Elizabeth and Janice Hart 1–15. London: Routledge.

- Foden, F. E. 1963. “Herbert Schofield and Loughborough College.” The Vocational Aspect of Education 15 (32): 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057876380000271

- Haynes, Richard. 2019. “Peter Heatly.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: OUP.

- Heatly, Peter. 1950. Scrapbook. Sir Peter Heatly Archive, University of Stirling.

- Heatly, Peter. 1950a. Swimming Report:1950 Auckland British Empire Games. Sir Peter Heatly Archive, University of Stirling.

- Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory. London: Harvard University Press.

- Huggins, Mike, and Mike O’ Mahony, eds. 2011. The Visual in Sport. London: Routledge.

- Hughes-d’Aeth, Tony. 2001. Paper Nation: The Story of the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia 1886-1888. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

- Hughson, John. 2019. “The Artification of Football: A Sociological Reconsideration of the ‘Beautiful Game.” Cultural Sociology 13 (3): 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975519852802

- Jackson, Steven J, and Brendan Hokowhitu. 2002. “Sport, Tribes, and Technology: The New Zealand All Blacks Haka and the Politics of Identity.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 26 (2): 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723502262002

- Jarvie, Grant, and Irene Reid. 1999. “Scottish Sport, Nationalist Politics and Culture.” Culture, Sport, Society 2 (2): 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/14610989908721837

- Kuhn, Annette. 2002. Family Secrets: Acts of Memory and Imagination. London: Verso. 153.

- Kuhn, Annette. 2007. “Photography and Cultural Memory: A Methodological Exploration.” Visual Studies 22 (3): 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860701657175

- Langford, Martha. 2001. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- LeGrand, Catherine. 1984. “Colombian Transformations: Peasants and Wage‐Labourers in the Santa Marta Banana Zone.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 11 (4): 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066158408438247

- McKee, Taylor, and Janice Forsyth. 2019. “Witnessing Painful Pasts: Understanding Images of Sports at Canadian Indian Residential Schools.” Journal of Sport History 46 (2): 175–188. https://doi.org/10.5406/jsporthistory.46.2.0175

- Mackenzie, John M., and Tom Devine, eds. 2016. Scotland and the British Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mangan, J.A. 1998. The Games Ethic and Imperialism: Aspects of the Diffusion of an Ideal. London: Routledge.

- O’Mahony, Mike. 2018. Photography and Sport. London: Reaktion Books.

- Pickering, Michael, and Emily Keightley. 2015. Photography, Music and Memory: Pieces of the past in Everyday Life. London: Palgrave.

- Ongley, Patrick, and David Pearson. 1995. “Post-1945 International Migration: New Zealand, Australia and Canada Compared.” International Migration Review 29 (3): 765–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839502900308

- Polley, Martin. 1998. Moving the Goalposts: A History of Sport and Society since 1945. London: Routledge.

- Prieto-Blanco, Patricia. 2010. “Family Photography as a Phatic Construction.” Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network 3 (2): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.31165/nk.2010.32.48

- Ryan, Greg. 2014. “The Turning Point: The 1950 British Empire Games as an Imperial Spectacle.” Sport in History 34 (3): 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460263.2014.931883

- Sandbye, Mette. 2014. “Looking at the Family Photo Album: A Resumed Theoretical Discussion of Why and How.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 6 (1): 25419. https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v6.25419

- Snow, Rachel. 2012. “Snapshots by the Way: Individuality and Convention in Tourists’ Photographs from the United States, 1880-1940.” Annals of Tourism Research 39 (4): 2013–2050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.05.002

- Sontag, Susan. 1979. On Photography. Milton Keynes: Penguin.

- Spencer, Stephanie. 2017. “Cosmopolitan Sociability in the British and International Federations of University Women, 1945–1960.” Women’s History Review 26 (1): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2015.1123026