ABSTRACT

The Japanese welfare model is identified by the unified typology method of welfare and production regime (Schröder Citation2013) as the corporate-centred conservative welfare regime (CCWR), a subgroup of the conservative welfare regime. The major company cross-class alliance (Ito, Citation1988) has played a pivotal role in constructing the CCWR under the group-based coordinate market economy (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001, Citation2007). It encompasses the following key characteristics: a male breadwinner-based social insurance with status-dependent programs and a greater role of occupational welfare. Therefore, it fragments social protection into a three-layered structure where regular employees of major enterprises, especially men, enjoy the most generous benefits from their company and government, followed by permanent labourers of small- to medium-sized firms who are provided for relatively modestly, while only minimum governmental benefit is allocated to non-regular employees.

Introduction

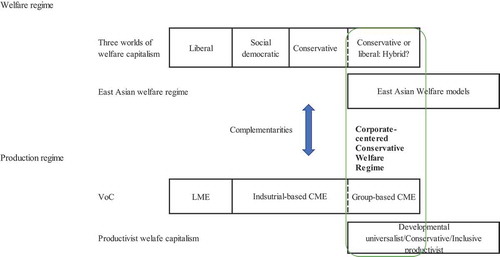

The Japanese welfare model is classified as a ‘hybrid’ combining liberal and conservative welfare regimes, in terms of Esping-Andersen’s ‘three worlds of capitalism’ (TWC) (Esping-Andersen, Citation1997). It has limited government involvement for decommodification, and a male-breadwinner-type social security divided according to occupation. In parallel with this characterization, numerous researchers have categorized the Japanese welfare model in diverse ways, such as the ‘East Asian welfare regime’ (EAWR) (Goodman, Citation1996) and ‘productivist welfare capitalism’ (PWC) (Holliday, Citation2000). These works have mainly been confined to their discussion on either the welfare typology or the production regime, thus paying scant attention to the institutional complementarities between them, which is the key to understanding the Japanese welfare model. In order to fill the gap in the analysis of the Japanese welfare state, we show that this model can be identified as a corporate-centred conservative welfare regime (CCWR) via a unified typology of welfare (Schröder, Citation2013) containing the ‘group-based coordinated market economy’ (GCME) in ‘varieties of capitalism’ (VoC) (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001, Citation2007); the CCWR is a subgroup of the conservative welfare regime in the TWC (rather than the ‘hybrid’ EAWR or fourth regime).

The CCWR is unique regarding the combination of government welfare and occupational benefits. The ‘major company cross-class alliance’ (Ito, Citation1988) has played a crucial role in constructing the CCWR under the GCME. Therefore, it fragments social protection into a three-layered structure where regular employees of major enterprises (especially men) enjoy the most generous benefits from their company and government, followed by permanent labourers of small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), who are provided for relatively modestly. Meanwhile, only minimum government benefits are allocated to others, such as non-regular employees, the self-employed, and primary industrial workers.

This paper is divided into three sections. In the first part, we clarify features of the CCWR through a unified typology that integrates social protection and capitalist production. We describe the limitations of previous research on Japanese welfare models because they were analysed in terms of either welfare regimes (such as the TWC and the EAWR) or production regimes (such as the VoC and the PWC). We demonstrate that a unified typology is useful in order to understand the Japanese welfare system’s unique characteristics.

The second section provides a causal analysis; that is, what makes the CCWR possible? We tackle this challenge with the aid of the concept of the GCME (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001, Citation2007) and cross-class alliance theory (Kume, Citation1998; Muramatsu et al., Citation1986). Finally, as economic globalization and population ageing appear to have had a significant impact on the CCWR, we evaluate recent changes it has undergone to discern whether or not its trajectory has left its long-established path.

The Japanese welfare state as a corporate-centred conservative welfare regime

The East Asian welfare regime and productivist welfare capitalism

The Japanese welfare system has special features that constitute the elements of a particular welfare typology. Goodman (Citation1996) notes that the Japanese welfare system is included in the EAWR, where the government’s role leans towards regulation rather than distribution, and is controlled by a centralized bureaucracy. Familial responsibility is still preserved due to Confucianism, and companies play a considerable role in providing welfare services. As families and companies are the main providers of welfare services, the residual social insurance system dominates the social welfare system. Our study underscores the strong role of both families and companies vis-à-vis government as the distinct essence of the Japanese welfare state.

However, the EAWR has limitations as a welfare regime typology because it is not based on consistent criteria and depends on a cultural approach. Further, it has methodological drawbacks in terms of indicators and measurement (Kim, Citation2016, p. 4; Uzuhashi, Citation2009). Therefore, the EAWR cannot grasp the driving force of this regime. In addition, although the EAWR’s features and development patterns are not designed to converge in one model, neither are they disconnected from a Western-focused welfare regime (Goodman, Citation1996, p. 194). Hence, the EAWR does not clearly identify the Japanese welfare state’s relative positionby itself. For instance, regarding the similarities between Japan and other Western countries in terms of familial responsibility, Japan (along with South Korea) has a ‘familialist’ trait that resembles southern European welfare states (such as Italy and Spain), where the aspects are as follows: generous social protection for the elderly in comparison with the youth; a large employment gender gap; and a strong family role in elderly care (Estévez-Abe et al., Citation2016). The set of policies in Japan’s welfare system cannot be fully captured through geographical specifics (Kasza, Citation2006, p. 133).

On the other hand, the Japanese welfare state is classified in light of the PWC as ‘developmental universalist’, a component that comprises a fourth typology besides the TWC (Holliday, Citation2000). The PWC is the extended model of the developmental state approach, the most salient facet of which is the subordination of social policy to economic policy (Choi, Citation2013; Kim, Citation2016, pp. 4–5). This is the yardstick to distinguish PWCs from Western welfare regimes. Thus, social rights are minimal and linked to productivity in this model, although the state underpins the market and families by means of some universal programmes that have stratification effects and that reinforce the position of productive elements. ‘Inclusive productivist welfare’ is a similar breed to the ‘developmental universalist’ perspective (Kim, Citation2016, pp. 32–34). Furthermore, the ‘conservative welfare regime’ (Aspalter, Citation2006) shares the same ideas as the PWC, and has different characteristics from the ‘corporatist/Christian democratic welfare regime’. That is, the state prioritizes the right to publicly invest in social development over the right to social security. As a social welfare policy, Japan has incursive welfare programmes, such as compulsory health insurance and national pension schemes that cover the entire population (Holliday, Citation2000; Kim, Citation2016, p. 42), but spending is comparatively meagre, and its system

displays a great duality between welfare provision to workers in large companies and their dependents; on the one hand, and workers in medium-sized and small enterprises, as well as people who do not join the work force, on the other. (Aspalter, Citation2006, p. 292)

Certainly, these are common attributes of the Japanese welfare state.

Nonetheless, the PWC has two dubious points: (1) the subordination of social policy to economic/industrial objectives; and (2) the critical role of bureaucratic politics (Holliday, Citation2000). As we will show later, most kinds of social insurance, public pensions, and health insurance were founded before World War II, with the exception of the National Pension Plan (NPP), which was established in 1961 to cover self-employed and primary industrial workers. Social and labour rights were also stipulated by the 1945 constitution. These rights promoted the expansion of social security in accordance with postwar economic growth. For instance, the NPP was introduced by social demand due to the deterioration of the patriarchal family system and public movements, which led to non-contributory pensions built by local governments (Ministry of Health and Welfare, Citation1962, p. 12; Yokoyama & Japan College of Social Work, Citation1967). Japan’s original social security system, which had fairly wide coverage, dates back to the pre-war period (Manow, Citation2001b); its historical legacy was inherited and developed with the help of social and labour rights.

Pempel and Tsunekawa (Citation1979) observe the dominance of bureaucratic politics in Japan under the ‘iron triangle’: (1) policymaking among the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP); (2) bureaucracy; and (3) Japan’s extensive business community. When labour unions have common interests with employers’ associations in the same way that labour protections are necessary for maintaining Japanese style employment (JSE) – that is, lifetime employment exclusively for male workers, seniority wages, and corporate unions – then they participate in the iron triangle (Tsunekawa, Citation1996, p. 209). This is possible because labour unions gained power in the 1970s after the oil crisis (Tsunekawa, Citation1996, p. 206) and as a result had great influence on policymaking through cross-class coalitions (Kume, Citation1998). Furthermore, the LDP sometimes developed social insurance by controlling bureaucracy in order to gain support from voters (Ramseyer et al., Citation1993, pp. 133–139). Bureaucracy did not have absolute superiority over policymaking because the ruling party had to attend to other actors in the iron triangle.

The Japanese welfare state had a developmentalist aspect as social spending lagged behind economic growth (Anderson, Citation1993, p. 17; Calder, Citation1988, p. 20; Hundt & Uttam, Citation2017, Ch. 3; Johnson, Citation1982, pp. 305–306). However, this does not mean that public welfare was a victim of economic development. Rather, the two evolved in tandem based on their functional complementarities (Kasza, Citation2006, p. 80). Overall, the pattern of Japanese growth, and the similarities among East Asian countries (i.e. South Korea and Taiwan) ‘go well beyond those articulated as part of the developmental state’ (Pempel, Citation1999, p. 179). This does not stem simply from government bureaucracy, but instead derives from more complex regimes grounded in the interactions of particular social actors and key government institutions (Pempel, Citation1999, p. 156). Thus, the developmental pattern was not the result of ‘bureaucratic teleological insight’ (Manow, Citation2001b), but only a consequent feature brought about by negotiations among actors within the Japanese production regime.

A unified typology of welfare and the production regime

The limitations of the EAWR and PWC derive from a lack of linkage between social protections and capitalist production. On the one hand, the EAWR does not consider the unique aspects of production systems, which differ according to the variety of capitalism involved. On the other hand, the PWC’s parsimony not only permits it to fully explore the mechanisms of the Japanese production regime, but also prevents it from analysing the features of the welfare system. In other words, it is unable to apprehend the remarkable combination of a male-breadwinner-based social insurance with status-dependent programmes and the greater role of occupational welfare, as well as relationships among service providers (e.g. family members, employers, and government) on which the welfare regime theory focuses. Hence, a unified typology of welfare and production regimes is suitable to capture the Japanese welfare system’s singular characteristics, because the institutional complementarities between social protections and capitalist production provide us with a clue that is difficult to identify when using one approach in isolation (Schröder, Citation2013, p. 167). As typologies of welfare or production regimes, the TWC and VoC are more inclusive than the EAWR and the PWC when we scrutinize the Japanese welfare system. This is because, as mentioned above, the EAWR is a fine-grained typology that overlaps with those of the TWC (instead of contradicting each other). Meanwhile, the VoC approach is an attempt to grasp capitalism as a system whereby the growth of national economies is included (Hundt & Uttam, Citation2017), such that the theoretical concept underlying the PWC – which focuses on economic development strategies – is shared by the VoC as well.

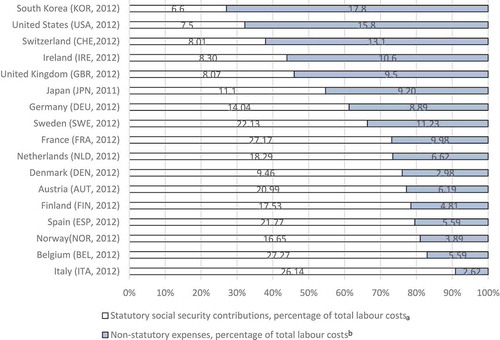

summarizes the typology based on the welfare-production nexus. The Japanese welfare state is denoted as the CCWR, spanning the welfare and production regimes. As shows, a high degree of company involvement in providing welfare for its workers is an attribute of the Japanese welfare state (Peng, Citation2000; Suzuki et al., Citation2010). The JSE warrants stable employment for regular workers, which is a substitution for some welfare protections, such as income maintenance policies for the unemployed (Uzuhashi, Citation1997, pp. 190–192, Citation2009, p. 224). Enterprise unions lead to residual welfare schemes, because their best organizational interests are not always compatible with national welfare programmes (Shinkawa & Pempel, Citation1986). They promote a company-based welfare system, in contrast with the corporatist/associational welfare model in continental welfare regimes, under which unions are coordinated at an industrial level and demand welfare provision collectively (Manow, Citation2001b). Firms in the US and the UK, where there is a liberal regime and a liberal market economy (LME), respectively, also play an important role in terms of occupational payments. Their occupational benefits are a measure of early retirement for corporate downsizing. In particular, defined-benefit pension and portable cash plans are used as mere fringe benefits for a mobile, flexible workforce (Ebbinghaus, Citation2001). Their role is completely different from the occupational scheme in the CCWR, which aims to build long-term employment relationships (Ebbinghaus, Citation2001). As discussed below, the role of family (i.e. women) is also interwoven by the CCWR in order to sustain the JSE.

Figure 1. Typologies and their congruence

Figure 2. Structure of labour costs as a percentage of total costs, average manufacturing production worker

We demonstrate the nature of the CCWR by factor analysis, where the variables are as follows (see the Appendix, ): (1) Non-statutory expenses: the ratio of non-statutory expenses to statutory social security contributions; (2) Decommodification: the decommodification score (Scruggs et al., Citation2017); (3) Poverty gap reduction: the effect of social transfer on the poverty gap, whereby the poverty line is equal to 60% of the median equivalized household disposable income (Caminada & Wang, Citation2019); (4) Female labour: the female labour force participation rate as a percentage of the total labour force; (5) A relative female economic activity rate for all women aged 25–35 and 34–44: the difference between the female and male labour participation rates (i.e. the gap between the male and female labour force participation rates) (Bambra, Citation2007; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2020a); and (6) The gender wage gap: the difference between the median earnings of men and women relative to the median earnings of full-time employees (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2020b).These variables shed light on the roles of corporations, government, and families, highlighting the diverse facets of CCWRs.

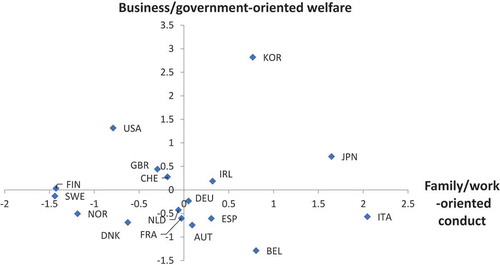

indicates two significant factors with an eigenvalue over one, representing two unrelated configurations of welfare service provision patterns. The first factor, which we designate ‘business/government-oriented welfare’ (BOW), has high factor loadings on non-statutory expenses and the gender wage gap as positive values, and decommodification and poverty gap reduction as negative values. BOW singles out the market or corporate centeredness of welfare against government security. The second factor captures ‘family/work-oriented conduct’ (FOC) among women, which has highly positive factor loadings in regard to the relative female economic activity rate, in contrast with strongly negative factor loadings on female labour. FOC determines whether women provide welfare services for their families or work outside the home. The four dimensions of welfare and the family nexus appear according to BOW on the vertical axis and FOC on the horizontal axis in . The first group, with both a high BOW and FOC factor scores, suggests that the company provides welfare services for its employees, and women take on the responsibility of family care in order to supply a shortage of services from employers and government.

Figure 3. The scatterplots of factor score: business/government-oriented welfare (BOW) and family/work-oriented conduct (FOC), ca. 2010–2012

Japan, South Korea, and Ireland fall under this category, but Ireland’s score is fairly low. The second group, with a high BOW but low FOC factor scores, implies that employees, including women, are given fringe benefits and buy welfare services (e.g. day care for children and the elderly) from the market to make up the shortfall of fringe benefits and social services. Typical cases include Switzerland, the UK, and the US, though Finland is a borderline case between the second and third groups. The third group, which has both low BOW and FOC factor scores, signals that social security is provided by the government, and defamilisation is achieved. Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands fit this category, albeit France is located near the border between this third group and the fourth one. The final fourth group, with a low BOW but high FOC factor scores, indicates that the government provides social welfare services but does not necessarily promote defamilisation. Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and Spain are included in this group.

Furthermore, when clustering countries using the two sets of factor scores (see the Appendix, ), we find five clusters, of which three groups run parallel to the TWC. However, Italy, Japan, and South Korea compose groups other than the TWC. Italy and Japan form the same cluster and South Korea is independent, although it is integrated into the cluster of Italy and Japan on a higher hierarchical level. However, Japan is quite different from Italy in terms of corporate welfare as shows while South Korea has a similar shape to Japan. The combination of comparatively high corporate and family welfare and fairly low government services is a distinctive feature of the CCWR. These characteristics are derived from male-breadwinner-based social insurance, along with status-dependent programmes and generous occupational welfare, especially for employees of major enterprises. Esping-Andersen (Citation1997, p. 184) points out that the ‘Japanese welfare state [is] very much an amalgam of the conservative “Bismarckian” regime and liberal residualism’ due to the strong role of the private sector (i.e. corporate occupational welfare). However, the private sector’s function differs between Japan and liberal regime countries, as we have already illustrated. Japan’s economic coordination system is completely unlike LMEs (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001).Although Esping-Andersen (Citation1997, p. 187) has a Eurocentric perspective, whereby the Japanese welfare system is at a crossroads since it is still evolving, Japanese welfare system is not a hybrid or an amalgam but it can be defined in as a CCWR, which shares aspects with the conservative welfare regime.

Table 1. Welfare regimes

In a nutshell, we can find common attributes of the CCWR, including male-breadwinner-based social insurance with status-dependent programmes, and families and occupational welfare playing a greater role. These characteristics suggest that the CCWR is intrinsically conservative. This model is also well defined as a sub-group of the conservative welfare regime in the TWC. The next section explains the foundation and reason for the CCWR.

Structure and causes of the CCWR

Occupational welfare: retirement payments and housing benefits

Basically, most occupational benefits are retirement payments and housing allowances. This has been the enduring trait of Japanese enterprise welfare (Fujita & Kojima, Citation1997; Tachibanaki, Citation2003; Takahasi, Citation1980). The ratio of the expense of fringe benefits to total labour costs was 7.6% as of 2016 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Citation2017, Table 32). A detailed breakdown of occupational welfare is as follows: retirement and savings = 4.5%; non-statutory social contributions = 1.6%, of which 47.3% goes to housing subsidies; and other = 1.5% (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Citation2017, Table 38).

Retirement payments are calculated according to one’s monthly salary and length of service in order to encourage lifetime employment. An employee who has worked for 40 years in a firm could receive 30–40 years’ worth of his/her monthly salary. In 2017, the total amount of retirement payments for a company with over 1,000 employees was an estimated 220,000 USD per employee with a college degree, while it was around 140,000 USD for smaller enterprises with 30–99 employees (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Citation2018a). Depending on their financial situation, companies can choose one of three payment options: (1) a lump-sum payment; (2) a corporate pension; or (3) both. Regarding corporate pensions, the Tax-qualified Pension Plan (TPP), which follows the US plan, was introduced in 1962 so as to level off the burden of retirement payments. The Employees’ Pension Fund (EPF) was created in 1966 at the request of companies that demanded coordination between private retirement payments and public pensions. The plan was modelled on the contract-out pension in the UK, but is a unique system because corporate pensions are inserted into public ones. Both types of pensions are benefit plans, and their establishment and management are strictly controlled by the government. In turn, the pension fund provides patient capital for corporate networks to maintain the JSE (Jackson & Vitols, Citation2001; Manow, Citation2001a). On the other hand, housing security has been provided in the form of rent subsidies and company houses. These are exclusively for employees of big firms, and are indispensable because they have to travel around the country for business (Fujita, Citation1997). The JSE incorporates these fringe benefits as a lifetime employment system; as such, they are a vital part of making the JSE work (Takahasi, Citation1980).

Japan’s social insurance and home ownership policies

The introduction of male, breadwinner-based social insurance with status-dependent programmes dates back to the pre-war period (before there was high economic growth), and involves various goals and administrative entities. We focus on pension and medical insurance systems because they account for over 80% of all social security expenditures.

As indicated previously, Japan’s public pension system is mainly composed of the NPP, a flat-rate pension for all residents, and the Employees’ Pension Plan (EPP), an income-related pension for private-sector employees. In 1941, the government enacted the Worker’s Pension Act, covering all physical workers except for those in small businesses with fewer than 10 employees. The Worker’s Pension Act extended coverage and was reorganized as the EPP in 1944. After World War II, the Mutual Aid Pension (MAP), which primarily targetspublic-sector employees, was established in 1958, but was integrated into the EPP in 2015. It gave extra benefits in accordance with corporate pensions. The NPP was instituted in 1959 to cover people who were ineligible for other pensions. In 1985, it was revised to become part of the Basic Pension (BP), which applies to those aged 20 and older.

The public health care system was introduced in 1922 as the nation’s health insurance programme, which is run by the national government or, in the case of large companies with over 300 employees, by company associations. This programme only covered blue-collar workers in high-risk jobs (e.g. miners), but coverage was widened after 1940 to include white-collar workers. As a result, the system was divided into company-association-managed health insurance for employees of major companies, and government-managed health insurance for workers in SMEs. The company-association-managed system promises workers superior benefits, with reasonably lower insurance premiums than other medical social insurance systems. It offers topping-up benefits, such as compensation for medical expenses and additional payments for sick or injury leave. After the health insurance programme was implemented, local governments arbitrarily launched the National Health Insurance (NHI) system in 1938 to improve the health of youth in rural areas, in order to ensure that they would join the military during the Sino–Japanese war. The NHI law, passed in 1958, mandates that all local governments provide medical services to non-regular employees, the self-employed, and primary industrial workers not covered by the nation’s health insurance programme. NHI benefits are inferior to those of other kinds of health insurance because they do not grant payments for sickness, injury, or maternity leave, even though the number of employees covered by the system has been increasing and account for 34% of the insured as of 2016 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Citation2018b).

In addition to these social insurance systems, the centre-right government, led by the LDP, established the country’s home ownership policy. The Ministry of Construction established the Japan Housing Corporation, which provides homes directly to the public. The Housing Finance Corporation, which was created by the ministries of Construction and Finance, offers low-interest loans to encourage home ownership among the population. A fairly large amount of resources comes from a public pension fund created as part of the Fiscal Investment and Loan Programme. The programme is managed by the Trust Fund Bureau in the Ministry of Finance. The World Bank and the International Labour Organization define home ownership as a kind of retirement income for the elderly (Holzmann et al., Citation2005, pp. 10–12; Gillion et al., Citation2000, pp. 465–468). Compared to other countries, Japan’s home ownership policy plays an essential role as an income maintenance instrument. For instance, the rate of those over 60 who live in their own homes was 78.4% in 2010, but only 66.3% in the US, 43.8% in Germany, and 50.5% in Sweden (The Cabinet Office, Citation2010).

Occupational welfare and male-breadwinner-based social insurance with status-dependent programmes and a home ownership policy have mutually complementary relationships. The EPF has been integrated into the EPP and provides generous payments. Likewise, with company association-managed health insurance, occupational topping-up benefits are incorporated into the public health insurance system. Japan’s home ownership policy promotes asset building for workers before they retire. Meanwhile, they are able to obtain rental subsidies and company homes from their employers during the early stages of their careers. These systems favour regular, exclusively male employees who work at large companies, because the JSE faces a serious divide between its core workers, who are largely male, and female workers in situations of peripheral employment (Estévez-Abe, Citation2008, p. 181; Peng, Citation2012).

The GCME and the CCWR

The GCME (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001, pp. 1–68) has been the driving force behind the CCWR. It differs from the industrial-based, coordinated market economy (like in Germany), which is the prototype for corporate governance. The GCME is built on ‘keiretsu, families of companies with dense interconnections cutting across sectors, the most important of which is nowadays the vertical keiretsu with one major company at its center’ (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001, p. 34). As mentioned earlier, employers and labour forge a cross-class alliance under the CCWR. The alliance exerts influence within the iron triangle to protect the company’s vested interests.

Kume (Citation1998, pp. 45–48) argues that major enterprise managers and labour unions formed ‘an accommodationist cross-class alliance’ in the 1950s. This led to negotiations on wages and employment protections at the national level, which had spillover effects on working conditions for workers in SMEs. At the same time, labour unions organized the National Council of Workers’ Welfare, and requested that employers’ associations allow retirement payments to be subject to collective bargaining and provide for some fringe benefits to be turned into social security (Fujita, Citation1997). In 1965, the Federation of Employers’ Associations (the leading employer’s organization in Japan at the time) published a report titled, ‘Basic policy for rationalizing occupational welfare’, which demanded that part of occupational welfare be converted into social security, with the aim of reducing labour costs. These movements led to the creation of the EPF and expanded company-association-managed health insurance (Takahasi, Citation1980). In turn, these material returns for regular employees played a crucial role in transforming radical unions into cooperative ones (Estévez-Abe, Citation2008, p. 181).

After the oil crisis at the beginning of the 1970s, employers and labour were bound together with the same identity – that is, groups sharing ‘a common destiny’ to survive economic competition. Labour unions in large enterprises departed from left-wing union organizations. They fell into line with employers and formed a ‘major corporation cross-class alliance’ (Muramatsu et al., Citation1986, pp. 105–169; Ito, Citation1988). Large firms were able to attain higher productivity than average, and could thus distribute their surpluses to their employees as fringe benefits (Fujita, Citation1997), which were combined with social insurance systems as a means of labour control (Ito, Citation1988). The CCWR’s distinctive features – which comprise a blend of breadwinner-based, occupationally divided social security and generous fringe benefits – are bolstered by the vital corporation cross-class alliance under the GCME.

The CCWR stratifies workers by company size and employment status. As indicates, the stratification entails three layers. Regular employees, mostly men in large companies, dominate the high end, followed by regular workers in SMEs. The lowest rung is occupied by non-regular workers in small businesses and the self-employed. Employees in large firms could gain higher retirement payments and housing allowances, in addition to generous social insurance in terms of benefits and premiums. In contrast, non-regular workers only receive minimum social security without any fringe benefits. As shows, this social stratification system differs from the continental conservative welfare regime, where people are stratified by industrial-based occupations.

Recent changes to the CCWR under economic globalization and Japan’s ageing population

A change in occupational welfare

The Japanese economy suffered a depression in the 1990s after the ‘bubble economy’ crashed, and experienced further economic downturn precipitated by the Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy in 2008. With regard to corporate pensions, the TPP was abolished in 2012, and the EPF could not be newly established from 2014 onwards because after these economic distresses, the return on investment deteriorated to the point where companies could not sustain such pensions. The government, a coalition between the LDP and the Komeito Party, introduced the defined-benefit corporate pension and the defined- contribution pension at the beginning of the 2000s. The latter is a new system modelled on the 401K in the US, which passes asset management risk from the employer to the employee.

As outlined in , the share paid by the company towards a corporate pension or lump-sum benefit was around 90% until the end of the 1990s, but was reduced by 10 percentage points to about 80% in 2018. This decrease was due to a decline in contributions to corporate pensions. The rate of enterprises that provide either a corporate pension or both a corporate pension and a lump-sum payment has been lowered by half. Instead, companies offering only a lump-sum payment grew from approximately 50% in the 1990s to around 70% in 2018. Newly formed corporate pensions have not been introduced as expected, and lump-sum benefits have come to play an even more important role than before. This trend especially holds for SMEs, whereas over 70% of large companies still offer corporate pensions to their employees. The reason for this is the high management cost and the complex procedures associated with applying (Social Security Council, Panel on Corporate and Private Pensions, Citation2019). Only a large company can bear the cost of corporate pensions.

Table 2. Retirement benefits

Housing allowances make up 5–6% of total labour costs; they dropped by only one percentage point to 4% from 2000 onwards. indicates that companies with over 1,000 employees provide their employees with 1.7% higher allowances than the average, while SMEs with 30–99 employees supply a fourth of the average allowance to their workers. This means that there is a difference of 6–7 times between the allowances of large companies and SMEs, but the gap has not widened to date. The ratio of company homes to overall housing units shrank, from 5.2% in 1983 to 2.1% in 2018. This decline began in the late 1990s due to the bursting of the bubble economy. As of 2018, 81.3% of companies with over 500 employees offered their workers company homes, while this figure was 29.8% for firms with under 100 employees (National Personal Authority, Citation2019).

Table 3. Housing benefits by enterprise size

In sum, primary fringe benefits (e.g. retirement payments and housing allowances) are still preserved, though slightly curtailed. Although the gap in housing allowances between different sized enterprises has not risen by much, the disparity in the provision of corporate pensions has widened.

Reforms to Japan’s social insurance system and home ownership policy

Japan’s social insurance systems have experienced two types of reforms: (1) containment and (2) recalibration, which is composed of rationalization and updating (Pierson, Citation2001). Rationalization is ‘the modification of programmes in line with new ideas about how to achieve established goals’ and updating refers to ‘efforts to adapt to changing societal demands and norms’ (Pierson, Citation2001, p. 425). The recalibration for Japan’s welfare systems explains why the CCWR remains resilient.

The 1985 NPP reform cut the standard pension benefit by 15% for a single person and 8% for a couple. It was the first major retrenchment after the golden age of pension expansion. The 2004 pension reform was a game changer because the contribution rate was capped from FY2017 onwards in all pensions by introducing a quasi-defined contribution formula. As a result, the standard replacement rate of the EPP, 59% in 2000, is projected to decrease to 50.2% in 2023. The reduction of the NPP benefit is more rigorous than the EPP, because the amount of the reduction is forecast at 30%. However, the 1985 NPP reform made redistribution between pension funds possible, and also extended coverage for housewives and foreigners, by incorporating it into the BP. To diminish reliance on social contributions, the 2004 pension reform mandated an increase in the portion of state subsidies within the BP fund from one-third up to one-half for FY2009. This reform also introduced several measures, such as improved compensation during parental leave and the division of employees’ pension benefits upon divorce, to protect women’s pension rights. These aspects seem to indicate updating because they involve stabilizing the management of pension funds and promoting defamilisation. Likewise, the MAP was integrated into the EPP in 2015 to ensure the stability of pension funds.

Regarding medical insurance reforms, medical expenses for patients have been raised. The government introduced the Health Insurance System for the Aged (HISA) in 1983, which covers those aged 75 and over and is run by local municipalities. The HISA imposed a flat-rate payment for medical services on the insured; such services had been free of charge until then. Patients’ co-payment increased following the introduction of a fixed-rate burden (i.e. 10% of medical costs) in 2000. In the same vein, patients’ payments for both company association-managed health insurance and government-managed health insurance have risen from 20–30% as the percentage of medical costs since 2003. The HISA was also created to advance fiscal stabilization.

Healthcare for the elderly has put heavy financial pressure on health insurance systems since the late 1970s. This has encouraged the introduction not only of the HISA, but also the long-term care insurance system, which was launched in 2000. The HISA was replaced with the lifelong medical care system in 2008 due to increased management costs. As a result, administrative authority of medical care for the elderly was shifted from local municipalities to prefectures in order to reinforce the stabilization of financial operations. The same reorganization of financial administrative authority was carried out in 2018 for the NHI system. These reforms are viewed as updates to adjust to demographic changes, as well as pension reforms.

Japan’s home ownership policy was also transformed. Around 2000, the chief authorities of housing services, the Japan Housing Corporation and the Housing Finance Corporation, become an executive agency separate from regulatory authorities, and funds to operate housing services had to be raised by issuing bonds. The management entity of the pension fund also shifted to become a kind of executive agency – the government’s Pension Investment Fund – and distribution of the fund for housing was confined to natural disaster recovery efforts. The chief corporations withdrew the direct supply of housing, but continue to finance money indirectly through private banks, because they were accused of squeezing private-sector business. Moreover, the government has been increasing tax spending for home ownership since 2000 to expand the national economy by building houses (Hirayama, Citation2014). These reforms are typical forms of rationalization to maintain the country’s home ownership policy. The government takes the initiative for home ownership policy, and people still have a strong desire to own their own homes because the state has not provided a housing allowance for residents who rent (Sunahara, Citation2018, p. 98).

In short, Japan’s social insurance systems have been reformed with the goal of stabilizing fiscal management and expanding women’s employment in line with demographic changes. These reforms have been accompanied by some retrenchments, such as pension cuts and increased co-payments for patients. In terms of housing policy, the government continues to guide its home ownership policy by deregulating housing loans and raising tax expenditures. These reforms are seen as either updating or rationalization.

Understanding the changes in the CCWR

Japan’s status-dependent social security systems strongly persist on track towards updating. Public pensions were drastically lowered with the 2004 and subsequent reforms. implies that BP benefits will decrease more than those of the EPP. In regard to medical insurance, demonstrates that the premium rates of the NHI system have been increasing (versus other insurance systems) so as to balance the budget, since insurance for those with low incomes, such as precarious workers and the elderly, expanded in the NHI system. These workers’ average yearly household income was around 17,500 USD in 1985, but fell by 30% to around 12,800 USD in 2018. Consequently, the NHI premium rates are the highest of the country’s medical insurance systems. These trends imply that the bottom layer is more disadvantageous under the CCWR’s three-layered structure. Thus, the CCWR enhances the nation’s character as a conservative welfare regime (Abrahamson, Citation2018; Hwang, Citation2012).

Table 4. Replacement rates of public pension systems

Table 5. Health insurance premium rates, % of insured income

This context is associated with a revision to the GCME. In 1995, the Japan Federation of Employers’ Associations released a proposal titled ‘Japanese Management in the New Era’. It recommended that workers be divided into three groups: (1) a ‘group with flexible labour conditions’; (2) a ‘group with a high level of specialization’; and (3) a ‘group developing their working skills for a longer time’. The aim was to confine the target of lifetime employment to the last group. The labour union federation of large enterprises, Rengo, accepted this recommendation and, together with the employers’ association, demanded security for the unemployed (who had been dismissed because of the depression) and subsidies for employers to employ them. The country’s prime corporation cross-class alliance tried to survive these measures (Ito, Citation1998).

Consequently, the JSE was transformed to a certain extent. The government eased regulations on employment systems around the beginning of the 2000s. Amendments to the Labour Standard Law created a discretionary working system, which resembles white-collar exemption in the US. The Worker Dispatching Law brought about an increase in non-regular workers. The ratio of non-regular workers to regular workers in 2008 was twice what it was in 1985, having expanded from 16.4% to 34.1% (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Citation2009). However, Oguma (Citation2019, pp. 47–48) reveals that the number of employees in big firms has not shrunk since the 1980s; they continuously occupy around 30% of all employed workers. The increase in non-regular workers is made up of those who are self-employed and workers employed by families in small firms (Oguma, Citation2019, pp. 64–70). Hence, recent labour deregulation has played a pivotal role in protecting core workers in large enterprises against the background of economic globalization (Peng, Citation2012).

In sum, paraphrasing Hall (Citation1993), these reforms represent a second-order change in which new instruments were introduced but the overarching goals remained the same. Thus, the goal is to protect core workers in key companies, and new instruments were instituted through several reforms to Japan’s social insurance systems and housing policy as either updating or rationalization.

Conclusion: from social dualization towards the race to the bottom?

Japan’s welfare system is characterized by an integrated typology of welfare and production regimes as the CCWR, which is a combination of male-breadwinner-based social insurance with status-dependent programmes and generous occupational welfare, and whose driving force is the leading company cross-class alliance. The CCWR is a ramification of the conservative welfare regime, rather than the EAWR, which is geographically defined and cannot fully grasp the distinctive characters of Japan’s welfare system. It also has the same productivist aspects as the GCME. In that sense, this typology considers the institutional complementarities between the welfare regime and the production regime. The CCWR has been maintained by several reforms via recalibration, such as updating and rationalization. Hence, it retains a hierarchy based on company size and employment status, in which regular employees in large enterprises reap the greatest advantages, followed by regular labourers in SMEs, while non-regular workers benefit the least.

The number of non-regular workers has been increasing due to the business strategy by the employer’s association under economic globalization. The insider-outsider problem (Esping-Andersen, Citation1999, p. 153; Häusermann & Schwander, Citation2012), which is unique to the conservative welfare regime, appears in various ways. Most outsiders are single women/mothers holding precarious jobs because the JSE marginalizes female workers. Additionally, the number of people who are not studying or working and who stay home all day, known as the hikikomori, has risen to one million (Cabinet Office, Citation2019). These are Japan-specific outsiders.

The government has passed several labour laws to reregulate the labour market. These included the Revised Worker Dispatching Act of 2012 and the labour law for workers regarding fixed-term contracts and part-timers in 2018. These re-regulations in the labour market aim to promote indefinite-term employment for irregular workers and equal pay for an equal value of work. However, it is not certain whether these measures are performing as expected, because the iron triangle has been transforming and the bureaucracy has shifted. Economic liberalization has led to a loss of bureaucratic power, and bureaucrats cannot freely control their organizations because their heads have been appointed by the Cabinet Office since 2014. It is also uncertain whether the major company cross-class alliance continues to be influential, as many Japanese firms have been relocating their production overseas, and the number of subcontracting companies for large enterprises has fallen dramatically. The ratio of subcontracting manufacturing SMEs to all manufacturing SMEs declined from 65.5% in 1981 to 17.0% in 2018 (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Citation1998; Small and Medium Enterprise Agency, Citation2019). The race to the bottom appears to be another scenario under these conditions.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of this article was presented at the 16th Annual EASP conference at the National Taiwan University from 2nd-3 July 2019. The authors would like to thank the organizer and participants of this event, Shih-Jiunn Shi, Chung-Yang Yeh, Kuehner Stefan as well as also two anonymous reviewers and the coordinator of the special issue, Ka Ho Mok. All errors are ours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Masato Shizume

Masato Shizume is Professor of Social Policy at the College of Social Sciences, Ritsumeikan University. His research field is comparative pension policy and poverty in old age. He has published many journal papers and book chapters, as well as edited books on the public pension and related topics.

Masatoshi Kato

Masatoshi Kato is Associate Professor of Political Science at the College of Social Sciences, Ritsumeikan University. His research interests include comparative political economy, institutional theory, and meta-theory of social sciences. He is the author of A Political Analysis of Welfare State Realignment (2012) (in Japanese). His works on comparative welfare states in English have appeared in the Ritsumeikan Journal of Humanities, Human and Social Sciences, and the Yokohama Law Review.

Ryozo Matsuda

Ryozo Matsuda is Professor of International Health Policy at the College of Social Sciences, Ritsumeikan University. His current main field is comparative health policy and systems research with a focus on high-income countries. He has also been continuously involved in policy research relevant to equity in health, inclusive health care, prison health, and the right to health. He has published numerous journal papers and book chapters, and edited books on health and social policy. Currently, he is serving as Director of the Institute of Human Sciences, a multidisciplinary research institute at Ritsumeikan University. Professor Matsuda has also been President of the Japanese Society for Health and Welfare Policy since 2017.

References

- Abrahamson, P. (2018). East Asian welfare regime: Obsolete ideal type or diversified reality. In K. H. Mok & S. Kühner (Eds.), Managing welfare expectations and social change: Policy transfer in Asia (pp. 90–103). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315122168-7

- Anderson, S. J. (1993). Welfare policy and politics in Japan: Beyond the developmental state. Paragon.

- Aspalter, C. (2006). The East Asian welfare model. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15(4), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2006.00413.x

- Bambra, C. (2007). Defamilisation and welfare state regimes: A cluster analysis. International Journal of Social Welfare, 16(4), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2007.00486.x

- Cabinet Office. (2010). The 7th survey of life and attitude among the aged in 2020. http://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/ishiki/h22/kiso/zentai/ (In Japanese).

- Cabinet Office. (2019). Survey on life conditions. https://www8.cao.go.jp/youth/kenkyu/life/h30/pdf-index.htm (In Japanese).

- Calder, K. E. (1988). Crisis and compensation. Public policy and political stability in Japan, 1949–1986. Princeton University Press.

- Caminada, K., & Wang, J. (2019). Leiden LIS budget incidence fiscal redistribution dataset on relative income poverty rates for 49 LIS countries – 1967–2016. http://www.lisdatacenter.org/resources/other-databases

- Choi, Y. J. (2013). Developmentalism and productivism in East Asian welfare regimes. In M. Isuhara (Ed.), Handbook on East Asian social policy (pp. 207–225). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857930293.00018

- Ebbinghaus, B. (2001). When labour and capital collude: The political economy of early retirement in Europe, Japan, and the USA. In B. Ebbinghaus & P. Manow (Eds.), Comparing welfare capitalism: Social policy and political economy in Europe, Japan, and the USA (pp. 76–101). Routledge.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1997). Hybrid or unique? The Japanese welfare state between Europe and America. Journal of European Social Policy, 7(3), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879700700301

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198742002.001.0001

- Estévez-Abe, M. (2008). Welfare and capitalism in postwar Japan. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511510069

- Estévez-Abe, M., Yang, J., & Choi, Y. (2016). Beyond familialism: Recalibrating family, state and market in Southern Europe and East Asia. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928716657274

- Fujita, Y., & Kojima, S. (1997). Occupational welfare and social security: A research question. In Y. Fujita & Y. Shionoya (Eds.), Occupational welfare and social security (pp. 1–14). University of Tokyo Press. (In Japanese).

- Fujita, Y. (1997). The typical relationship between occupational welfare and social security. In Y. Fujita & Y. Shionoya (Eds.), Occupational welfare and social security (pp. 17–52). University of Tokyo Press. (In Japanese).

- Gillion, C., Turner, J., Baily, C., & Latulippe, D. (Eds.). (2000). Social security pensions: Development and reform. International Labor Office.

- Goodman, R. (1996). The East Asian welfare states: Peripatetic learning, adaptive change, and nation-building. In G. Esping-Andersen (Ed.), Welfare states in transition: National adaptations in global economies (pp. 192–224). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446216941.n7

- Goodman, R., & Peng, I. (1996). The East Asian welfare states: Peripatetic learning, adaptive change, and nation-building. In G. Esping-Andersen (Eds.), Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economies (pp. 192–223). London: Sage.

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Introduction. In P. A. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 1–68). Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2007). Preface for Japanese edition: Varieties of capitalism and Japan. In P. A. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 3–20). Nakanishiya Press. ((In Japanese)).

- Häusermann, S., & Schwander, H. (2012). Varieties of dualization? Labor market segmentation and insider-outsider divides across regimes. In P. Emmenegger, S. Häusermann, B. Palier, & M. Seeleib-Kaiser (Eds.), The age of dualization (pp. 27–51). Oxford University Press.

- Hirayama, Y. (2014). Housing policy and the reproduction of home ownership. Social Policy and Labor Studies, 6 (1), 11–23. (In Japanese). https://doi.org/10.24533/spls.6.1_11

- Holliday, I. (2000). Productivist welfare capitalism: Social policy in East Asia. Political Studies, 48(4), 706–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00279

- Holzmann, R., Hinz, R. P., & Von Gersdorff, H. (2005). Old-age income support in the 21st century: An international perspective on pension systems and reform. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-6040-x

- Hundt, D., & Uttam, J. (2017). Varieties of capitalism in Asia: Beyond the developmental state. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hwang, G.-J. (2012). Explaining welfare state adaptation in East Asia: The cases of Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Asian Journal of Social Science, 40(2), 174–202. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853112x640134

- Ito, M. (1988). The formation of major corporation cross-class alliance. Leviathan, 2, 53–70. ( In Japanese). http://www.bokutakusha.com/leviathan/leviathan_2.html

- Ito, M. (1998). Revisiting the major corporation cross-class alliance: The features and the durability. Leviathan, (special issue), 73–94. ( In Japanese). http://www.bokutakusha.com/leviathan/leviathan_1998_winter.html

- Jackson, G., & Vitols, S. (2001). Between financial commitment, market liquidity and corporate governance. In B. Ebbinghaus & P. Manow (Eds.), Comparing welfare capitalism: Social policy and political economy in Europe, Japan, and the USA (pp. 171–189). Routledge.

- Johnson, C. (1982). MITI and the Japanese economic miracle: The growth of industrial policy, 1925–1975. Stanford University Press.

- Kasza, G. J. (2006). One world of welfare: Japan in comparative perspective. Cornell University Press.

- Kim, M. M. S. (2016). Comparative welfare capitalism in East Asia: Productivist models of social policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kume, I. (1998). Disparaged success: Labor politics in postwar Japan. Cornell University Press.

- Manow, P. (2001a). Business coordination, wage bargaining and the welfare state: Germany and Japan in comparative historical perspective. In B. Ebbinghaus & P. Manow (Eds.), Comparing welfare capitalism: Social policy and political economy in Europe, Japan, and the USA (pp. 27–51). Routledge.

- Manow, P. (2001b). Welfare state building and coordinated capitalism in Japan and Germany. In W. Streeck & K. Yamaura (Eds.), The origins of nonliberal capitalism: Germany and Japan in comparison (pp. 94–120). Cornell University Press.

- Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. (1998). FY 1998 Basic survey on commerce and industry. https://www.meti.go.jp/statistics/tyo/syokozi/result-2/h2d5k2aj.html (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. (1962). The history of the national pension plan: From 1959 to 1961. The Pension Bureau. ( In Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2009). Employment measures in post-financial crisis Japan. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/affairs/dl/04.pdf/ (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2017). FY 2016 General survey on working conditions. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00450099&tstat=000001014004&cycle=0&tclass1=000001104336&tclass2=000001104376 (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2018a). FY 2017 General survey on working conditions. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000031778275&fileKind=0 (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2018b). FY 2016 fact-finding survey on national health insurance. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=dataset&toukei=00450397&tstat=000001111735&cycle=8&tclass1=000001111736&result_page=1 (In Japanese).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2012). FY 2011 General survey on working conditions. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000012674045&fileKind=0 (in Japanese)

- Muramatsu, M., Ito, M., & Tsujinaka, U. 1986. The pressure group of post war in Japan. Toyokeizaishihou Corporation. (In Japanese).

- National Personal Authority. (2019). Private company working condition survey. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&cycle=7&toukei=00020111&tstat=000001133584&tclass1=000001133585&stat_infid=000031869424 (In Japanese).

- Oguma, E. 2019. The structure of Japanese society: Historical sociology on employment, education, and welfare. Kodansya. (In Japanese).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020a). Labour market statistics: Labour force statistics by sex and age: Indicators (OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database)). https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00310-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020b). Gender wage gap (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/7cee77aa-en

- Pempel, T. J., & Tsunekawa, K. (1979). Corporatism without labor? The Japanese anomaly. In P. Schmitter & G. Lehmbruch (Eds.), Trends toward corporatist intermediation (pp. 231–279). SAGE.

- Pempel, T. J. (1999). The developmental regime in a changing world economy. In M. Woo-Cumings (Ed.), The developmental state (pp. 137–181). Cornell University Press.

- Peng, I. (2000). A fresh look at the Japanese welfare state. Social Policy & Administration, 34(1), 87–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00179

- Peng, I. (2012). Economic dualization in Japan and South Korea. In P. Emmenegger, S. Häusermann, B. Palier, & M. Seeleib-Kaiser (Eds.), The age of dualization: The changing face of inequality in deindustrializing societies (pp. 226–249). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199797899.003.0010

- Pierson, P. (2001). Coping with permanent austerity: Welfare state restructuring in affluent democracies. In P. Pierson (Ed.), The new politics of the welfare state (pp. 410–456). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198297564.003.0014

- Ramseyer, J., Rosenbluth, M., & McCall, F. (1993). Japan’s political marketplace. Harvard University Press.

- Schröder, M. (2013). A unified typology of capitalisms. In M. Schröder (Ed.), Integrating varieties of capitalism and welfare state research (pp. 58–62). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137310309_4

- Scruggs, L., Detlef, J., & Kati, K. (2017). Comparative welfare entitlements dataset 2 (Version 2017–2019). University of Connecticut & University of Greifswald.

- Shinkawa, T., & Pempel, T. J. (1986). Occupational welfare and the Japanese experience. In M. Shalev (Ed.), The privatization of social policy? Occupational welfare and the welfare state in America, Scandinavia, and Japan (pp. 280–326). Macmillan.

- Small and Medium Enterprise Agency. (2019). FY 2018 Basic survey of small and medium enterprises. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000031849250&fileKind=0 (In Japanese).

- Social Security Council, Panel on Corporate and Private Pensions. (2019). On the diffusion of corporate pension: A document in the 5th meeting of corporate pension and private pension panel. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10600000/000509684.pdf (In Japanese).

- Soskice, D. (2007). Macroeconomics and varieties of capitalism. In B. Hancké, M. Rhodes, & M. Thatcher (Eds.), Beyond varieties of capitalism: Conflict, contradictions, and complementarities in the European economy (pp. 89–120). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199206483.003.0003

- Sunahara, Y. (2018). Do you prefer a newly built house? Housing and politics in Japan. Minerva Shobo. ( In Japanese).

- Suzuki, M., Ito, M., Ishida, M., Nihei, N., & Maruyama, M. (2010). Individualizing Japan: Searching for its origin in first modernity. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(3), 513–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01324.x

- Tachibanaki, T. (2003). To what extent does a company commit to welfare provisions? They could retreat into it. In T. Tachibanaki & Y. Kaneko (Eds.), Reform of corporate welfare system (pp. 19–40). Toyokeizaishipou Corporation. (In Japanese).

- Takahasi, K. (1980). Modern corporate society and employee welfare facility. In H. Nishimura (Ed.), Modern employee benefit: The quest for a new welfare society (pp. 113–136). Yuhikaku. (In Japanese).

- Tsunekawa, K. (1996). Enterprise and nation. University of Tokyo Press. (In Japanese).

- Uzuhashi, T. (1997). The comparative study of the modern welfare state. Nihon Hyouron Corporation. (In Japanese).

- Uzuhashi, T. (2009). Japan: Constructing the ‘welfare society’. In P. Alcook & G. Craig (Eds.), International social policy: Welfare regimes in the developed world (2nd ed., pp. 210–230). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-08294-7_11.

- Yokoyama, K. (1967). The history of the establishment of the national pension plan. In Japan College of Social Work (Ed.), Social work in Japan after WWII (pp. 133–158). Keiso Shobou. (In Japanese).