ABSTRACT

This article aims at setting out a broader context for the debates and discussions on welfare transformations driven by rapid global challenges and restructuring. Confronted with challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, governments and societies across the globe must rethink and reimagine their social welfare approaches to make them appropriate and effective to manage the risks and crises. The papers in this special issue address three major themes: 1) democratisation and changing welfare regimes / social policy provision; 2) reflections of social service delivery; 3) rethinking state-market-society relationships when managing welfare needs.

Introduction

The world was disrupted by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic near the end of 2019. The rise in the number of infections has adversely affected the global village especially after COVID-19 has spread to every corner of the world. The current attempts to thwart the negative effects of globalization, such as the ‘America First’ policy of President Trump in the US, have produced unsatisfactory results in curbing the pandemic. Similarly, the resurgence of nationalism in the UK and other parts of Europe have failed to stop the global health crisis despite attempting to rearrange the ‘global order’ by putting their national interests above anything else. The unprecedented global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has inevitably resulted in a global economic downturn, even though some countries in Asia, such as China, seem to have quickly recovered from this crisis. The first part of this article discusses how the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has affected social and economic development in Asia. Confronted with challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, governments and societies in Asia and other parts of the world must rethink and reimagine their social welfare approaches to make them appropriate for a post-COVID-19 recovery. This special issue puts together eight articles critically reflect upon challenges of welfare provision and the search for social policy innovations in Asia.

Unprecedented global health crisis and its impact on socio-economic development

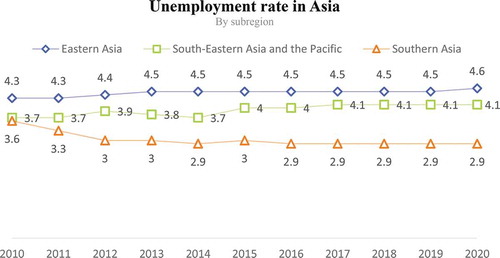

Against the aforementioned broader socio-economic and political economy contexts, this special issue critically examines the social welfare transformation and social policy innovation in Asia whilst taking into account the rapid socio-economic and political changes that have taken place before the COVID-19 outbreak. The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic across the globe has affected not only economic growth but also other development aspects (Seker et al., Citation2020). The sudden outbreak of COVID-19 has adversely disrupted the global economy, temporary lockdown policies not only detrimentally harm the international travels and mobility but also lead to worse global economic recession since the World War Two (World Bank, Citation2020). shows the sudden decline in the economic growth of countries/regions in East Asia after the onset of the global health crisis (). With a disrupted economic development, various countries in Asia have experienced an unemployment crisis (). Commentators believe that the economic shocks in developing countries have reached unprecedented heights following the onset of the pandemic (Aljazeera, Citation2020). Whilst governments across Asia have attempted to go back to normal and promote mobility across the region, the unstable public health conditions in their area and their fluctuating number of COVID-19 cases have blocked their attempts to ‘normalise’ international travels and mobility. The negative social and economic effects of the pandemic have also influenced the social policy strategies adopted across different East and Southeast Asian societies (Yap, Citation2020).

Challenges for welfare regimes at a time of a deep global crisis

A deep global crisis causes not only a global economic downturn but also massive losses of life, and these changes undoubtedly influence the present arrangements of unique welfare regimes across different parts of Asia (Yap, Citation2020). Further research should then investigate how governments respond to the COVID-19 global health crisis, which has serious impacts on social, economic, political, and geo-political developments (Greer et al., Citation2020). Managing the increasingly complex socio-economic and political economy contexts like the unprecedented global health crisis, the papers presented in this special issue critically reflect upon the changing roles of the state, the market, the family and the wider society / community when discharging their welfare responsibilities. Since Esping–Andersen (Citation1990) conceptualized welfare regimes in the west, different welfare models or approaches have been proposed in the literature to conceptualize different welfare arrangements across the globe. Scholars in East Asia have also used the East Asian welfare model (EAWM) to conceptualize/analyse welfare arrangements and social policies in the region. These models show that many governments within the region prioritize productivity and social welfare over economic growth. Embedded with strong Confucian values that highlight the importance of family and its welfare responsibilities, some scholars argue that family serves the important function of caring for both younger and older generations (Abrahamson, Citation2018; Walker & Wong, Citation2005). However, the growing impact of economic globalization, coupled with the rising impact of democratization, influences the state–market–society relations (Hwang, Citation2011; Mok, Citation2011). Such rapid socio-economic and political changes inevitably influence the welfare expectations/values of citizens and the way governments address/manage the changing social/welfare needs/expectations (Aspalter, Citation2006; Bambra, Citation2007; Gough, Citation2004; Hudson & Kuhner, Citation2009; Hwang, Citation2011; Ku, Citation2007; Lee & Ku, Citation2007; Mok & Hudson, Citation2014; Powell & Barrientos, Citation2004; Powell & Kim, Citation2014).

Central to EAWM is its emphasis on productivism than on protectionism. However, scholars in the field of welfare regime have raised the question of ‘which welfare regime is not productive in nature?’ No single government across the region can adopt a welfare model or make welfare arrangements to manage changing welfare needs and social policy expectations without striking a balance between economic productivity and welfare protection. Without a sustainable and continued economic growth, governments cannot easily maintain a high level of welfare expenditures. The first wave of welfare regime debates in East Asia was led by Jones (Citation1993), who emphasized the importance of the cultural dimension in conceptualizing welfare approaches in the region. Meanwhile, despite acknowledging the importance of culture in analysing welfare regimes in East Asia, Holliday (Citation2000) criticized the cultural approach for being oversimplified similar to other variables, such as the productive structures that are unique to different countries/cities and the broader political economy. To diversify sources of support for maintaining a highly sustainable welfare society, the discussions on the welfare regimes in East Asia have integrated ‘community’ as the fourth actor or sector in addition to the state, market and family (Sumarto, Citation2017). To fill this gap, scholars have examined the impacts of broader issues, such as the changing political economy, democratization and welfare values/expectations of citizens and the governability/legitimacy of governments in formulating welfare models/approaches that are adaptive to rapid social, economic, political and global changes (Kim, Citation2019; Ku & Chang, Citation2017; Mok, Citation2011; Mok, Kuhner, Yeates Citation2017; Papadopoulos & Roumpakis, Citation2013). A critical contextual analysis has resulted in the creation of different models that account for diverse pathways of welfare state development in Asia (Hwang, Citation2011), including productivist (Holliday, Citation2000), developmental (Kwon, Citation2001), redistributive (Lin & Wong, Citation2013), inclusive (Lin & Wong, Citation2013), protective (Kuhner, Citation2015), informal-liberal (Sumarto, Citation2017) and informal-inclusive pathways (Sumarto, Citation2017).

Recent debates on EAWM have also touched upon the rapid economic changes and resulting social policy expansion and welfare arrangements in China. Similar discussions have emerged amongst scholars who examine social welfare transformations by using this model. Whilst some commentators have argued that the significant social policy expansion and reforms in social welfare/social service delivery will lead to the welfare universalism of China, others contend that China is too huge in terms of regional diversity (Chan & Ngok, Citation2016; Mok & Wu, Citation2013). We may not be able to conceptualize the welfare developments in China, which is known for its wide regional differences, by using a unified model, but the case of China can be examined by referring to the political economy perspective and adopting a historical institutional approach. Mok et al. conceptualized the welfare model of China as ‘paternalistic welfare pragmatism’ (Mok, Citation2017; Mok & Qian, Citation2019). When examining the pathways of welfare state development in East Asia, Hudson and Hwang (Citation2013) highlighted the importance of the historical evolution of welfare regimes, whereas other scholars have highlighted the contributions of historical institutionalism in understanding the different pathways of welfare state development (Shih, Citation2017; Xiong, Citation2014). The collection of articles in this special issue addresses a few major problems related to transformation of welfare regimes in East Asia before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The three major themes that constitute this special issue focusing on (1) democratization and changing welfare regimes/social policy provision; (2) reflections on social service delivery; and (3) rethinking state–market–society relationships when managing welfare needs. This article concludes by pointing out some directions for future research on the COVID-19 pandemic and welfare regimes.

Democratization and changing welfare regimes/social policy provision

Many studies have highlighted the importance of global challenges, restructuring and democratization to welfare expansion (e.g., Croissant & Walkenhorst, Citation2020; Hwang, Citation2011; Izuhara, Citation2013). Do political democratization and the worsening income inequality increase the public support for redistribution in East Asian democratic developmental welfare states? Against the broader political context of growing democratization in Asia, Chung-Yang Yeh and Yuen-Wen Ku quantitatively analysed Taiwan, which represents an atypical example of a new democratic developmental welfare state. Their empirical findings show that the perception towards income inequality will lead to dissatisfaction with the performance of the democratic regime and consequently erode public support for redistribution. They argued that mitigating income inequality can help promote political satisfaction and welfare state building for new democracies.

By drawing on historical institutionalism, Hsiu-Hui Chen and Shih-Jiunn Shi examined the National Pension Insurance and National Health Insurance reforms in Taiwan and neutralized the dominant view by comparing the policy processes in the country before and after the implementation of consolidated democratization processes in four dimensions, namely, actor constellations, interactive modes of policymaking, policy networks and power relationships. By highlighting diverse political dynamics in terms of the state capacity and state–society relationships that lead to different policy outcomes, Chen and Shi offered insights for understanding the intricate relationships between democratization and social policy in East Asia.

By analysing data and drawing evidence from East Asia, Ding-Yi Lai, Wen-Chin Wu and Jen-Der Lue examined intergenerational mobility and preference for redistribution. By using data from the fourth wave of the Asian Barometer Survey, they found that the upward intergenerational social mobility of citizens increases along with their support for government-led redistribution in autocracies. Whilst conventional wisdom posits that intergenerational social mobility reduces individual preference for redistribution, this study investigates the case of democracies, where electoral competition plays a key role in redistribution. Lai, Wu and Lue argued that the effect of intergenerational social mobility on individual preference for redistribution differs in dictatorships, where the state makes the key decisions regarding redistribution. This finding contributes to our present understanding of individual preferences for redistribution in dictatorships. This study thus provides very useful insights that can aid in analysing intergenerational mobility and highlight the important role of government intervention in ensuring an appropriate redistribution in Asia.

By conceptualizing the welfare development of Japan using EAWM, Masato Shizume, Masatoshi Kato and Ryozo Matsuda argued that the Japanese welfare model is identified by the corporate-centred conservative welfare regime (CCWR), a subgroup of the conservative welfare regime (Schröder, Citation2013). By critically reflecting on the changing welfare arrangements offered by the state and the market, Shizume, Kato and Matsuda argued that the major company cross-class alliance (Ito, Citation1988) plays a pivotal role in constructing CCWR under a group-based coordinate market economy (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001, Citation2007). According to their findings, the Japanese welfare regime can be characterized as a male-breadwinner-based social insurance with status-dependent programmes and a dominant role of occupational welfare. With these unique economic structures in place, the Japanese welfare regime fragments social protection into a three-layered structure where the regular employees of major enterprises, especially men, enjoy the most number of benefits from their companies and governments, followed by permanent labourers of small- to medium-sized firms and non-regular employees.

Reflections on social service delivery

Whilst managing rapid social and political changes, different governments have made serious attempts in transforming their approaches for providing appropriate services to their citizens and for promoting social harmony or social cohesion (Mok & Kang, Citation2020). By examining the contracting out social services adopted by the Chinese government against the broader social welfare reforms and social policy expansion in the country, Mok, Chan and Wen critically examined the changing state–market–society relationships in their analysis of how local governments in Guangzhou manage social service reforms. Based on a policy review and by conducting fieldwork and intensive interviews with major informants who manage contracting out social services in Mainland China, they found that the Chinese government diversifies its social service provision by engaging different social forces, namely, the wider society in general and the social work profession in particular. Given the changing social, economic and political circumstances, especially when the government realizes a potential political risk to empower the social sector by bringing in a wide range of social forces and actors that may be outside the state control, the Chinese government chose to scale down its service purchase or selected providers that appeal to the locally groomed providers than to overseas partners.

The critical reflections on the aforementioned findings lead to the conclusion that NGOs in China are not fully autonomous and that their roles in expanding social service provision in civil society and promoting social cohesion are yet to be fully elucidated. Mok, Chan and Wen empirically found from their fieldwork that the Chinese government skilfully and tactically utilizes NGOs to implement its social policy initiatives and consequently achieve its policy goals and political objectives of strengthening social control than encouraging the emergence of a civil society (Mok & Kang, Citation2020). The key findings of Mok, Chan and Wen in this issue clearly show that although governments want to involve the community in providing welfare services of social policies apart from state, market and family provisions, whether the fourth sector (i.e. the community through NGOs) would have developed as an equally resourceful actor will determine the state–market–family and community configurations in social welfare provision and the power relationship between the state and the third sector (Mok et al., Citation2020).

By reflecting upon the role of private and public partnerships in providing care for early childhood education, Gyu-Jin Hwang explored how the service delivery structure utilizing non-traditional welfare institutions creates tensions between private and public interests when offering early childhood education in South Korea. Hwang found that the primary concern of the state is to ensure that its citizens have access to available services in the market, the providers of which are entrusted with social responsibilities. However, whilst the state pursues its social goals by using economically efficient tools, the economic logic is introduced in ways that are detrimental to these social goals.

Yun-Hsiang Hsu explored the different responses to domestic employment regulation by using the intuitionalism framework. Previous studies show that policy design plays a significant role in regulating domestic employment. Drawing on the secondary literature and policy documents, Hsu argued that the needs of employers, in the form of care policies, shape different outcomes in each country, thereby creating a vacuum in the legal status of domestic workers and placing employer–employee relationships under the category of individual contracts. Hsu then proposed several policy suggestions that are aimed at planning and improving the management practices for domestic workers.

Rethinking state–market–society relations in welfare provision

According to Kolaric (Citation2009), ‘during the historical development of individual societies, which depend on specific economic, cultural and political conditions, different hierarchies of spheres (market, state, civil society and community) emerged from which individuals obtain resources to ensure their social protection and well-being. The different historically formed hierarchies of spheres represent different welfare systems’ (Kolaric, Citation2009, p. 55). When analysing the relationship between the state and NGOs in China in light of the above framework, Mok et al. observed that the engagement of NGOs in Chinese social governance is far from ‘empowerment and participation’ as they do not completely participate in policymaking and cannot fully represent the voice of individuals, groups and communities (Mok et al., Citation2020). Similarly, if we analyse Hwang’s research on early childhood education in Korea in light of the framework proposed by Kolaric, we must be sensitive about the unique state–market relationships when forging public–private partnerships in providing social services/social policies.

By taking together the findings of articles compiled in this special issue, the changes in welfare regimes cannot be analysed separately from unique economic structures characterized by different processes of industrialization, urbanization, economic growth and welfare values commonly shared amongst citizens as well changes in demography (Myles & Quaagno, Citation2002; Wilensky, Citation1975). Other scholars also illustrate the dialectic process of different class interests between organized political groups and the ruling classes (Korpi, Citation1983; Myles & Quaagno, Citation2002; Olsen & O’Connor, Citation1998). In addition, the welfare expectations and values of people continue to change when they experience economic and social transformations not only domestically but also regionally and globally. With the advancements of the Internet and information technology, people across the globe can easily observe the changes/reforms in welfare arrangements and social service delivery. Therefore, policy learning and policy transfer also contribute to the formation and reformation of welfare regimes across different parts of the globe (Ellison, Citation2018; Mok & Kuhner, Citation2018).

Geopolitics, regional cooperation and reinventing welfare regimes

The unprecedented global health crisis that has affected many Asian countries during the preparation of this special issue has also influenced welfare arrangements and social policy choices. In Insecurity and Welfare Regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America (Gough, Citation2004), Gough provided useful insights for examining the insecurity of welfare regimes because of the ‘lack of social provision’ in coping with social risks, especially when social security is heavily dependent on informal networks. Nevertheless, as the world experiences unprecedented social, economic and health crises resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, we must reflect upon ‘welfare regimes in the time of crisis’ from comparative and international perspectives. Whether governments can introduce social policies and offer welfare/social services that are appropriate for the changing needs/expectations of their citizens should depend on their financial and governance capacities. Whilst the contemporary world is still dealing with this crisis, states across different parts of the globe are searching for approaches/models that are appropriate for managing their changing social, economic and political environments. To strike a fine balance between economic growth and social development and welfare needs, governments must work collaboratively with the market, community, family, individuals and the global society.

To counterbalance the threat posed by the US and its allies in the global political order, China is strategically cementing its position as an economic partner of Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Australia and 10 ASEAN members by signing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) deal on 15 November 2020. As a free trade agreement, RCEP is expected to positively affect ‘China’s image as a cooperative economic actor’ (Lemert & Runde, Citation2020). With its leading role in promoting RCEP, China will reap economic benefits from its involvement and expand its industries in other countries. By analysing the impact of RCEP on the positioning of China in the regional cooperation framework, Lemert and Runde (Citation2020) argued that ‘RCEP fits the China’s dual circulation strategy which pairs self-sufficiency driven by domestic consumption with supplemental international connections’. After China was excluded from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the recent withdrawal of the US from this agreement has encouraged China to fill such vacancy (Bradsher & Swanson, Citation2020).

RCEP also provides ASEAN countries with the opportunity to engage in a highly strategic collaboration not only with the Big Threes in East Asia (i.e. China, Korea and Japan) but also with New Zealand and Australia in the Pacific. Through this regional collaboration platform, Asian governments are searching for a way to move beyond their national borders to co-create additional economic development opportunities for their citizens. Without a continued and sustainable economic growth, governments are facing challenges in engaging in sensible welfare reforms with a creative combination of protective and productive/developmental approaches when managing changing welfare needs (Kim, Citation2019; Kuhner, Citation2015; Mok & Qian, Citation2019; Yuda, Citation2020). With a productive regional cooperation, we expect not only governments but also other non-state sectors to reinvent their welfare regimes for managing the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, to respond to the call for rethinking and reimagining governance strategies, we should not only forge cooperation across the state, market, community and the wider society but also engage with sub-national and international governance to achieve a better management of the consequences of the pandemic (Brousselle et al., Citation2020). Other political scientists and sociologists have also compared how liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes have managed the COVID-19 crisis and sought for best practices in managing a post-COVID-19 society (Alon et al., Citation2020). In conclusion, future research on changing welfare state development should adopt the broader political economy perspective whilst taking politics, power and policy transfer into consideration.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Lam Man Tsan Chair Professor Research Fund in supporting the present paper for professional editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ka Ho Mok

Ka Ho Mok is Vice President and Director of Institute of Policy Studies, Lingnan University, Hong Kong and he has researched and published extensively in the field of comparative policy studies with particular reference to contemporary China and East Asia.

Yeun-Wen Ku

Yeun-Wen Ku is Professor of Department of Social Work, National Taiwan University in Taiwan. He has researched and published extensively in social policy with particular reference to social development issues and social policy in Taiwan.

Tauchid Komara Yuda

Tauchid Komara Yuda is Research Associate from Department of Social Development & Welfare, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. He has researched welfare regime theory in the aspect of history and politics as a framework for analyzing welfare distribution practices over time. His areas of expertise include social policy, citizenship, social development, and welfare politics.

References

- Abrahamson, P. (2018). East Asian welfare regime: Obsolete ideal-type or diversified reality. In K. H. Mok & S. Kuhner (Eds.), Managing welfare expectations and social change: Policy transfer in Asia (pp. 90–103). Routledge.

- Aljazeera. (2020). COVID-19: In charts and maps. https://www.aljazeera.com.

- Alon, I., Farrell, M., & Li, S. M. (2020). Regime type and COVID-19 response. FIIB Business Review, 9(3), 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714520928884

- Aspalter, C. (2006). The East Asian welfare model. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15(4), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2006.00413.x

- Bambra, C. (2007). Defamilisation and welfare state regimes: A cluster analysis. International Journal of Social Welfare, 16(4), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2007.00486.x

- Bradsher, K., & Swanson, A. (2020, November 15). China-led trade pact is signed, in challenge to U.S. The New York Times. Retrieved November 28, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/15/business/china-trade-rcep.html

- Brousselle, A., Brunet‐Jailly, E., Kennedy, C., Phillips, S. D., & Quigley, K. Beyond COVID‐19: Five commentaries on reimagining governance for future crises and resilience. (2020). Canadian Public Administration, 63(3), 369–408. published online on 25 September 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12388

- Chan, C. K., & Ngok, K. L. (2016). China’s social policy: Transformation and challenges. Routledge.

- Croissant, A., & Walkenhorst, P. (eds.). (2020). Social cohesion in Asia. Routledge.

- Ellison, N. (2018). Politics, power and policy transfer. In K. H. Mok & S. Kuhner (Eds.), Managing welfare expectations and social change: Policy transfer in Asia, (pp. 8–24). Routledge.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Gough, I. (2004). Welfare regime in development context: A global and regional analysis. In I. Gough, A. Wood, P. Barrientos, P. Bevan, & G. Room (Eds.), Insecurity and welfare regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America (pp. 15–48). Cambridge University Press.

- Greer, S., King, E., da Fonseca, E. M., & Peralta-Santos, A. The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. (2020). Global Public Health, 15(9), 1413–1416. published online on 20 June 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Introduction. In P. A. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 1–68). Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2007). Preface for Japanese edition: Varieties of capitalism and Japan. In P. A. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 3–20). Nakanishiya Press.

- Holliday, I. (2000). Productive welfare capitalism: Social policy in East Asia. Political Studies, 48(4), 706–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00279

- Hudson, J., & Hwang, G. J. (2013). Pathways of welfare state development in East Asia. In M. Izuhara (Ed.), Handbook on East Asian social policy (pp. 15–40). Edward Elgar.

- Hudson, J., & Kuhner, S. (2009). Towards productive welfare? A comparative analysis of 23 OECD countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 19(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928708098522

- Hwang, G. J. (ed.). (2011). New welfare states in East Asia: Global challenges and restructuring. Edward Elgar.

- Ito, M. (1988). The formation of major corporation cross-class alliance. Leviathan, 2, 53–70. (In Japanese) http://www.bokutakusha.com/leviathan/leviathan_2.html

- Izuhara, M. (ed.). (2013). Handbook on East Asian social policy. Edward Elgar.

- Jones, C. (1993). The Pacific challenge: Confucian welfare states. In C. Jones (Ed.), New perspectives on the welfare state in Europe (pp. 198–217). Routledge.

- Kim, S. Y. (2019). Reappraisal of the developmental welfare state theory on the underdevelopment of state welfare in East Asian growth economies. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909619886679

- Kolaric, Z. (2009). Third Sector organizations in the changing welfare systems of central and Eastern European countries: Some theoretical and methodological Considerations. Teorija in Praksa, 46(3), 224–236.

- Korpi, W. (1983). The democratic class struggle. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Ku, Y. W. (2007). Developments in East Asian welfare studies. Social Policy and Administration, 41(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00542.x

- Ku, Y. W., & Chang, Y. (2017). To be or not to be part of greater China: Social development in the post-Ma Taiwan. Social Policy & Administration, 51(6), 898–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12338

- Kuhner, S. (2015). The productive and protective dimension of welfare in Asia and the Pacific: Pathways towards human development and income equality? Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 31(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/21699763.2015.1047395

- Kwon, S. (2001). Economic crisis and social policy reform in Korea. International Journal of Social Welfare, 10(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2397.00159

- Lee, Y., & Ku, Y. W. (2007). East Asian welfare regimes: Testing the hypothesis of the developmental welfare state. Social Policy and Administration, 41(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00547.x

- Lemert, A., & Runde, E. (2020, November 30). Beijing restricts exports related to national security. Lawfare.

- Lin, K., & Wong, C. K. (2013). Social policy and social order in East Asia: An evolutionary view. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 23(4), 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2013.778785

- Mok, K. H. (2011). Right diagnosis and appropriate treatment for the global financial crisis? Social protection measures and social policy responses in East Asia. In G. J. Hwang (Ed.), New welfare states in East Asia: Global challenges and restructuring (pp. 155–174).Edward Elgar.

- Mok, K. H. (2017). Wither the developmental state? Adaptive state entrepreneurship and social policy expansion in China. In T. Carroll & D. Jarvis (Eds.), Asia after developmental state: Disembedding autonomy (pp. 297–325). Cambridge University Press.

- Mok, K. H., & Kang, Y. Y. (2020). Social cohesion and welfare reforms – The Chinese approach. In A. Croissant, Croissant, A., & Walkenhorst, P. (Eds.), Social cohesion in Asia (pp. 26–49). Routledge.

- Mok, K. H., Chan, C. K., & Wen, Z. Y. (2020). State-NGOs relationship in the context of China contracting out social services. Social Policy & Administration. published on September 26, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12651

- Mok, K. H., & Hudson, J. (2014). Managing social change and social policy in greater China: Welfare regime in transition. Social Policy and Society, 13(2), 235–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746413000596

- Mok, K. H., & Kuhner, S. (eds.). (2018). Managing welfare expectations and social change: Policy transfer in Asia. Routledge.

- Mok, K. H., Kuhner, S., & Yeates, N. (2017). Managing welfare expectations and social change: Policy responses in Asia. Social Policy and Administration, 51(6), 845–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12335

- Mok, K. H., & Qian, J. W. (2019). A new welfare regime in the making? Paternalistic welfare pragmatism in China. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(1), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718767603

- Mok, K. H., & Wu, X. F. (2013). Dual decentralization in China’s transitional economy: Welfare regionalism and policy implications for central-local relationship. Policy and Society, 32(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2013.02.002

- Myles, J., & Quaagno, J. (2002). Political theories of the welfare state. Social Service Review, 76(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/324607

- Olsen, G., & O’Connor, J. (1998). Understanding the welfare state: Power resources theory and its critics. In J. O’Connor & G. Olsen (Eds.), Political resource theory and the welfare state: A critical approach (pp. 3–36). University of Toronto Press.

- Papadopoulos, T., & Roumpakis, A. (2013). Familistic welfare capitalism in crisis: Social reproduction and anti-social policy in Greece. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 29(3), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/21699763.2013.863736

- Powell, K., and Kim, K. (2014). The 'Chameleon” Korean welfare regime. Social Policy & Administration, 48(6), 626–646.

- Powell, M., & Barrientos, A. (2004). Welfare regime and the welfare mix. European Journal of Social Policy, 43(1), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.147567652024.x

- Schröder, M. (2013). A unified typology of capitalisms. In M. Schröder (Ed.), Integrating varieties of capitalism and welfare state research (pp. 58–62). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137310309_4

- Seker, M., Ozer, A., & Korkut, C. (2020). Reflections on the pandemic in the future of the world. Turkish Academy of Sciences Publications.

- Shih, S.-J. (2017). Social decentralization: Exploring the competitive solidarity of regional social protection in China. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 10(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17516234.2016.1258523

- Sumarto, M. (2017). Welfare regime change in developing countries: Evidence from Indonesia. Social Policy and Administration, 51(6), 940–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12340

- UNCTAD. (2020). UN calls for $ 2.5 trillion coronavirus crisis package for developing countries. https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=2315.

- Valarino, I., Meil, G., & Rogero-Garcia, J. (2018). Family or state responsibility? Elderly-and childcare policy preferences in Spain. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 38(11/12), 1101–1115. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-06-2018-0086

- Walker, A., & Wong, K. C. (2005). East Asian welfare regime in transition: From confucianism to globalization. Policy Press.

- Wilensky, H. (1975). The welfare state and equality: Structural and ideological roots of public expenditures. University of California Press.

- World Bank. (2020). COVID-19 to plunge global economy into worst recession since World War II, The World Bank, retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/08/covid-19-to-plunge-global-economy-into-worst-recession-since-world-war-ii. Access on 11 November 2020.

- Xiong, Y. G. (2014). The unbearable heaviness of welfare and the limits of social policy in China. In P. Kettunen, S. Kuhnle, & Y. Ren (Eds.), Reshaping welfare institutions in China and the Nordic countries (pp. 33–56). Nordic Centre of Excellence Nordwel.

- Yap, O. F. (2020). A new normal or business-as-usual? Lessons for COVID-19 from financial crises in East and Southeast Asia. The European Journal of Development Research. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00327-3

- Yuda, T.K., Damanik, J. and Nurhadi. (2020). Examining emerging social policy during COVID-19 in Indonesia and the case for a community-based support system. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, published online on 8 November 2020.

- Yuda, T.K. (2020). Indonesia’s emerging welfare regime depiction during COVID-19 outbreaks, Unpublished manuscript under review.