ABSTRACT

Modern mining operates on enormous scales and quantities that go beyond everyday comprehension, which in turn has existential and metaphysical implications, and this article is an experiment in characterising ‘existentially disturbing’ aspects of extraction landscapes. We attempt to characterise and make sense of the Hannukainen mining landscape with regard to its deeply contradictory and dissonant – effectively monstrous – nature as an experienced place. Specifically, we explore various affective, emotional and psychological impacts of the (now closed) Hannukainen mine in Finnish Lapland. Drawing on the so-called ‘new weird’ fiction, we employ a ‘weirding approach’ into the ambivalent, unsettling and disorientating aspects of an extraction landscape in relation to the socio-ecological condition of the Anthropocene. We seek to identify how various features of the Hannukainen landscape resonate with deeper and broader cultural ideas of, for instance, aboveground and belowground and the this-worldly and otherworldly. We conclude that there is an interplay of presences and absences in Hannukainen, which generates uncertainty, disorientation and compromises the very coherence of the mine as an experienced landscape, placing it in a weird in-betweenness of non-linear spatialities and temporalities associated with monsters and the monstrous.

Introduction

This article is an experiment in characterising an ‘existentially disturbing’ extraction landscape. Specifically, we engage with the affective, emotional and psychological impacts of a mining landscape (Hannukainen in Finnish Lapland) where massive quantities of material have been extracted and moved around. The Hannukainen mine was in operation between 1978 and 1990 during which time 4563 million tons of ore were extracted at the site. Such quantities are impossible to comprehend in terms of concrete everyday experience of the world, and modern mines, or extractive industries more generally, can be compared to Morton’s (Citation2013) ‘hyperobjects’ (see also Campbell Citation2021 and below). There is nothing special about the Hannukainen mine – it is just one of many similar twentieth-century mines in Finland, not especially large or especially important. And this is very much the point that we wish to make: even an ordinary extraction operation and the associated landscape are so massive that they go beyond comprehension, which in turn has existential and metaphysical implications. We attempt to characterise and make sense of the Hannukainen mining landscape with regard to its deeply contradictory and dissonant – effectively monstrous – nature as an experienced place.

Modern extractive industries operate on enormous scales and quantities, which generates peculiarly monumental landscapes, albeit as unintentional by-products of retrieving minerals, and such landscapes have significant affective and awe-inspiring qualities. This monumentality can be employed to impress and appeal to investors, but it also provokes concerns of environmental destruction and climate change, with extractive industries very much at the heart of the Anthropocene world. Industrial mining has induced awe, fascination and fear in ways that go beyond the purely rational for centuries (e.g. Naum Citation2019). However, the emotional and affective dimensions of mining projects, past and present, have long been overlooked, although their significance is now increasingly being recognised (e.g. Ey and Sherval Citation2015; Ey, Sherval, and Hodge Citation2017; Wright Citation2012). Our experiment is aligned with such emotional geographies of mining from the particular perspective of ‘weirding’ (e.g. Tabas Citation2015; Turnbull, Platt, and Searle Citation2022; Ulstein Citation2021).

The aim of our engagement with Hannukainen from a weirding perspective is to understand some aspects of the affective power of modern mining landscapes, especially as regards their disturbing and dissonant character. The term ‘global weirding’ (Friedman Citation2010) has been increasingly used in the past decade to replace the term ‘climate change’ as a way of better communicating and contemplating the unusual events, impacts, intensities and effects/affects caused by climate disruption and breakdown. Drawing on the so-called ‘new weird’ fiction, weirding approaches urge explorations into the ambivalent, unsettling and disorientating aspects of the current socio-ecological condition (Turnbull, Platt, and Searle Citation2022). In interrogating the Hannukainen mine, we aim to look beyond such concerns as environmental destruction as a physical phenomenon and reflect on the more metaphysical affects of the enormous quantities of material that have been extracted, moved around and manipulated in Hannukainen. We consider how excess and the excessive, as manifested in diverse and contradictory ways at the site, generate a sense of wrongness that goes beyond purely rational matters, but nonetheless mediate perceptions of and relationships with extraction sites, whether active or discontinued.

Extractive industries and extraction sites have conventionally been approached in rationalist, technological and economic terms, which marginalises other – such as cultural, existential and metaphysical – dimensions of mining. Yet appreciating the significance and role of those other dimensions of mining is crucially important for understanding mining conflicts in a world where large-scale extraction of minerals is critically important, whether we like it or not. In the case of Finnish Lapland there are current fears (rationally or otherwise) that it will be turned into a mining reserve, due to recent geopolitical developments as well as the ‘green transition’ that requires enormous quantities of rare metals.

We present our characterisation of Hannukainen – or some selected aspects of it – as a reflective journey through a weird landscape, though dimensions of this weirdness unfolded only gradually. We attempt to make sense of various elements of the mining landscape by identifying their resonances with deeper and broader cultural ideas of, for instance, aboveground and belowground and the this-worldly and otherworldly. Such ‘resonances’ are hinged on the cultural legacies of how humans have perceived and lived with mining and the subterranean through centuries and millennia. In particular, we mapped our sensory and emotional responses to the various features of the Hannukainen landscape and sought to link them to higher-level anxieties in the age of the Anthropocene with the help of weird fiction.

Encountering Hannukainen

You arrive at the site by car after taking a turn from the local main road between the municipal centre of Kolari and the fjell (mountain) Ylläs with its skiing centre. There is a gate, but it has long been left open and is almost unnoticeable. After a short drive, you enter the site. While the presence of a large-scale industrial operation in the area is immediately obvious, it is impossible at this point to get a proper sense of the place and its size – you need to venture deeper into the mine and/or on to higher ground. You will find no substantial industrial installations or machinery on the site: mostly it is made up of dirt roads, piles of waste rock and random rubbish here and there (and not even very much of that). There are a few portacabins, some locked and others not, on the highest spot of the site, apparently related to the long-planned reopening of the site (). Hannukainen was an open-pit mine without underground tunnels, but its ores were processed in its sister mine, Rautuvaara, some kilometres away. Rautuvaara was an underground mine and had aboveground constructions, such as a mining tower, that were absent in Hannukainen.

Figure 1. Portacabins on the Hannukainen plateau. Intriguingly, Microsoft Word identified this picture as representing ‘a small group of buildings on a desert’; see below on Hannukainen as a desert. (Photo: Tina Paphitis)

A couple of operations, such as gravel extraction, appear to continue at the site, but in general it is mostly just rocks and sand. We saw some evidence of (absent) human presence, including an old car which moved from one part of Hannukainen to another during one of our longer visits, although, as if to add to the eeriness, we never saw the driver. Other signs of recent activity included a makeshift firing range with a bench rest, a home-made target, and spent brass casings showing evidence of at least a dozen different firearms ( and ). People have visited and continue to visit Hannukainen, possibly for subversive and private reasons, and we can only speculate as to whether they are similarly attracted to this place due to its monstrous weirdness in comparison to less-disturbed nature areas and/or curated holiday village environments within the vicinity, or whether it is just a quiet place where they can go about their business undisturbed. The silence of the first range felt particularly odd: as if there ought to be echoes of gunshots. Wandering around, you pick up the monumental feeling of the site, but it is a twisted monumentality that is difficult to make sense of.

We have visited Hannukainen many times over the last few years, often without any specific reason. Although it lacks obvious focal points or features, the site feels oddly imposing and ‘empty’ in a generally disorienting manner, which we probably found fascinating, even if unconsciously, and which kept pulling us back there again and again. This is despite the fact that, initially at least, there is really not much to see. Hannukainen has its own monumental qualities, but the landscape is, in fact, quite nondescript. Likewise, the place feels desolate, but not quite abandoned – it is being used but it was always not quite obvious what for (apart from gravel extraction and some kind of a workshop that operates on the site).

Overall, Hannukainen seemed to have a curiously Ligottian feeling to it. Thomas Ligotti is an American horror writer and a key figure of the ‘new weird’, and his stories play with feelings in a similar manner to how Hannukainen appeared to play with ours (although we made this association only in hindsight, after many visits). We also seem to recall that the site has changed although we cannot be sure in what ways exactly. One of our shared recollections prior to our fieldwork, however, was that there had been all kinds of cluttered, random, discarded stuff in this landscape, more than we actually found there in 2022 when, for a week, and as a part of a larger project, we decided to carry out a landscape characterisation of Hannukainen. Although the ‘Ligottian feeling’ was initially inspiring for thinking of Hannukainen in terms of nightmares and our discovery of a ‘weirding perspective’, we ultimately found our perceptions and feeling resonating more closely with H. P. Lovecraft’s (1890–1937) horror fiction with its indescribable cosmic monsters. Lovecraft was a racist among other things and ultimately ‘against the world and against life’, as Houellebecq (Citation2005) had it, but also a pioneering figure of modern weird fiction with a very distinctive ‘cluttered’ style of writing, and his horror fiction has come to have a wide and significant influence after his death, as well as being a cornerstone of ‘weirding’ approaches (see further e.g. Gonzales and Sederholm Citation2022; Harman Citation2012; Joshi Citation2010; Loponen Citation2019, 54–61).

In our 2022 fieldwork, we set out to make some sense of this landscape that had a fascinating and disturbing feeling to it, yet we seemed to be incapable of determining what made Hannukainen feel this way. We had some ideas as to what we might want to look into and document, but by and large we were wandering and drifting around in the mine, making observations about this and that aspect of the place, thinking and talking, taking pictures, wandering and drifting some more. These drifts began individually, sometimes meeting up for a time, then drifting apart again, until, eventually, we started picking up all kinds of intriguing features in this landscape – many more, indeed, than can be discussed in one article. Somehow, the seeming emptiness of the place began to open up and reveal features, layers and dimensions that perhaps can, to some degree, be ‘sensed’ simply by going to and experiencing the site, although the thoughts and feelings that come to play then can be difficult to identify and analyse. As part of our exercise – and as an important orientational point – we considered what kind of a thing, being or entity Hannukainen as a closed modern mine is. We eventually reckoned that it was a monster.

Mines and monsters

Our thinking of mines in terms of monsters and the monstrous is by no means coincidental but is motivated by several factors. First, mines and monsters are contextually or circumstantially connected in that both emerged – or became more significant – with early state-like complex societies that emerged in the Near East in the fourth millennium BCE. The extraction of minerals (metals) was an elementary component of these Bronze Age societies and has been ever since, not only in a practical but also in a socio-cultural and cosmological sense (see e.g. Herva, Komu, and Paphitis Citation2022). As for monsters, Wengrow (Citation2014) has argued that monsters in the form of hybrid beings such as the sphinx, gryphon and dragon were specifically products of early civilisations of Mesopotamia and spread around from there; for Wengrow, monsters were either non-existent or very rare in earlier times. Monsters, then, are creatures of ‘civilisaton’ and have persisted to the present day in various forms.

Second, there are some illustrative previous discussions of mines in terms of monsters. Keeling and Sandlos (Citation2017) have coined the term ‘zombie mines’ for closed mines which nonetheless continue to be active in dangerous ways, whereas Ureta and Flores (Citation2018) have discussed active tailing ponds as behaving like dragons and tricksters. Finally, various scholars have discussed various processes and phenomena, such as climate change and environmental degradation, as monsters of the Anthropocene (e.g. Tsing et al. Citation2017). Such monsters are somewhat different from ‘conventional’ monsters in that they are ‘cosmic horrors’ along the lines of how Lovecraft conceived them: unfathomable entities that threaten entire (human) existence.

Monsters, whether such traditional ones as dragons or unconceivable Lovecraftian horrors, have many similarities with mines and mining landscapes, as we will map in the remainder of this article. While monsters as hybrid beings are in some ways different from the cosmic monsters of the Anthropocene, both have certain general characteristics that are relevant to our discussion of Hannukainen. Namely, monsters go and operate beyond the boundaries of the ‘ordinary’ (or rationalistically conceived) reality. They transgress or transcend linear space–time boundaries and ‘extend’ into other dimensions beyond the one that is readily perceivable or accessible to people. They have visible and invisible dimensions to them; there is uncertainty about their nature and being as entities; they are ambiguous, ambivalent and provoke cognitive dissonance. Their existence and manifestations are neither purely objective nor purely subjective, and they can be present/absent in extraordinary ways. In brief, there is a distinctive ‘more-ness’ or ‘excess’ to them in comparison to ‘ordinary’ or ‘natural’ entities (see further e.g. Holloway Citation2017; Mittman Citation2012; Musharbash Citation2014).

All this makes monsters ‘good to think with’ (Mittman Citation2012, 8) for exploring the weirder and unfamiliar aspects of the lived reality, including extractive industries and extraction sites. Extraction is not only entangled within our everyday lives through its integrity to various necessities and objects (e.g. fuel, smartphones), but remains weird and dissonant due to the very long-standing perceptions and imaginaries of the subterranean as an otherworld where things are and work differently from aboveground (see Herva, Komu, and Paphitis Citation2022). As monsters in various forms are our distinctive co-habitants in the age of the Anthropocene (e.g. Tsing et al. Citation2017; Ulstein Citation2022), it comes as no surprise that weird fiction has envisioned new kinds of monstrous entities since the early twentieth century – monsters that go beyond ‘traditional’ and more conceivable monsters such as dragons or werewolves: we may not even readily identify what they are, although they are integrally entangled with the human world. In what follows, we try to identify and reflect on some forms, expressions and manifestations of the monstrous in the context of Hannukainen and how these resonate with more general environmental, cosmological and existential concerns in the contemporary world in crisis.

Monstrous monumentality

One afternoon, after we had explored the mine for a couple of days, we were writing down our thoughts and reflections. We had set out to address the question ‘What happens in the closed mine of Hannukainen?’, but seeing that although some things were happening in the mine, simultaneously nothing much appeared to be happening there, so our thoughts developed in a slightly different direction, and we started to wonder: ‘What is this place and what is wrong with it?’ We were having a hard time ‘pinning down’ the site and saying something meaningful about it. One of us had written down in our reflective field notes that the site is ‘too large, too transformed, too empty’. This turned out to be a critically important notion. At the same time, ‘too large, too transformed, too empty’ brought about the insight that led towards the monstrous and the weird: there is simultaneously too little and too much to the place: excessive emptiness, absence of presence and present absences at the same time.

Mining and other megaprojects create monumental landscapes, and monumentality is intended to have affective and emotional impacts on people. Hannukainen and other mining landscapes, however, are not designed to be monumental, but their monumentality is an unintentional by-product (cf. Gandy Citation2016 on ‘unintentional landscapes’) of manipulating massive quantities of matter. Mining landscapes are not monumental in a similar way to, say, the landscapes of the Giza pyramids, but more akin to vast natural landscapes – except that there is nothing natural about the Hannukainen landscape in the sense that it is, very distinctly, a human creation. Yet it does not quite come across that way either, but more like something shaped by monsters of the Anthropocene (albeit with humans to do their work). Ultimately, of course, Hannukainen – like any landscape – is really neither natural nor cultural. Rather, it is a specific form of a nature–culture entanglement characteristic to the Anthropocene; in this case a landscape transformed to the degree where it feels as if there is nothing ‘natural’ to it. All this amounts to the Hannukainen landscape having a decisively disturbing monumentality to it, something resembling and echoing the weird geometries of ancient cities of non-human monstrous beings in Lovecraft’s tales. Hannukainen is not a random mess, but it is deeply different from ordinary everyday landscapes. It is a product of extraction, ‘an ecologically subtractive force’, and ‘[i]n this subtraction, what is left behind is often left empty; in emptiness is ecological and existential isolation, and in isolation, again, is horror’ (McClanahan Citation2020, 12).

The degree of transformation that is in evidence in Hannukainen can provoke existential horror, as suggested by the above quote, but also elicit feelings of the sublime comparable to what Peeples (Citation2011) calls ‘the toxic sublime’ in the context of environmental pollution. The disturbing character of the Hannukainen landscape does not, we felt, stem from any single factor, but the combination of the scale, intensity and speed of the landscape formation – resulting in a gigantic hole (which we discuss further at the end of the article) – contributed to the sense of the monstrous. While this was, of course, only our feeling about the site, there is evidence that mine workers can also conceive mining landscapes (at least in underground mines) in terms of the weird and monstrous (we are currently working on that material for forthcoming publications).

Egypt

While subtraction is ultimately the central force behind the formation of the Hannukainen landscape, extracted materials have also been moved around and piled up, which has contributed to the forms and shapes of the place. For the people such as ourselves who are relatively unfamiliar with the technicalities of mining operations, the logic of landscape formation and its specific features remain more or less unknown, which therefore subtly suggests alienness and otherness. The overall impression of the Hannukainen landscape is that of a (constructed) desert dominated by rock and sand in myriad formations where interrelations between human and non-human agents are difficult to identify with certainty. Hannukainen is not empty, yet ‘too empty’ was one of the predominant feelings that this landscape provoked – it brings a desert to mind. Mines and desert may not be utterly unknown, but most Europeans are familiar with them only in a distanced and abstracted manner and they are associated with prominent cultural imaginaries which largely revolve around otherness and exoticism, in addition to which both mines and deserts appear as dangerous and hostile environments.

It is unsurprising and indeed expected, then, that the extraordinary and monstrous character of the subterranean realm (whether in the form of underground mines or otherwise) continues to be prominently present in, for instance, popular-culture imaginaries, as do remote and unfamiliar places characterised by desert landscapes, whether in the form of orientalist exoticisation of Egypt, North Africa and the Middle East or desert planets as in the novel and film Dune. Thus, Lovecraft’s alien cities with their ‘weird geometries’ also tend to be located in remote and alien lands, not infrequently associated with desert environments (e.g. Arabia and Antarctica) – or the ocean, another domain of the unfamiliar and unknown (see Hite Citation2021 on Lovecraftian geographies and places and their meanings) ().

In addition to this impression of the desert, mounds of siderock made us think of Egyptian pyramids as well – deformed and/but somehow vaguely hinting at some underlying and otherworldly dimension of a reality looming behind and seeping into the world that humans readily and ordinarily perceive. Indeed, something has been quite literally ‘unveiled’ in the landscape of Hannukainen through subtraction/extraction, but there is, again, a deeper resonance to metaphysical aspects of unveiling here: weirder topographies and temporalities that we are not exposed or sensitive to in ordinary flow of everyday life in normal environments (see below).

The ‘pyramids’ of waste rock imply that there is a structure to this landscape, although it is a broken structure. Besides these deformed pyramids or ziggurats, piles and fields of rock also resonated with the traditions of building cairns, in Fennoscandia and elsewhere, since prehistoric times (and particularly the Bronze Age and Iron Age). Cairns and natural boulder fields (known as ‘devil’s fields’) have rich folklore associated with them, often in reference to the dead, death and non-humans. Intriguingly, cairns have commonly been associated with otherworldly domains irrespective of their age or original functions – this applies even to mundane heaps of rock resulting from, for instance, clearing fields for cultivation, or piles of rocks from old sauna stoves (see e.g. Herva and Lahelma Citation2020, 99–102 Muhonen Citation2008; with references). The association of cairns with the underworld, as portals between worlds and as sacrificial sites, is found in many cultures across the globe (Varner Citation2004). Cairns can come as impressive monumental constructions, such as Bronze Age (burial) cairns as well as small and nondescript piles of rock, and yet they have long been regarded as embodying some special power. The piles of siderock in Hannukainen appeared, both in scale and form, as something like monstrous cairns.

There is, then, a weird and nightmarish monumentality and reference to faraway and otherworldly places at play on some level in the experienced environment of Hannukainen. Hence, the associations with deserts, Egypt and pyramids are illustrative of the deeper dynamics of our experience of the place, which is precisely this sense of some hidden (monstrous) reality lingering underneath the readily perceivable landscape. It hints at worlds underneath the surface: what are the deeper dynamics of formlessness and its further implications? A (weird) ‘Egypt in Lapland’ jars and breaks the sense of place and provokes feelings of discontinuity, dissonance and weird space–time relations (cf. Herva Citation2021). Although Hannukainen can come across as a desert-like place of rock and sand, we are not quite sure how we came to associate this landscape specifically with Egypt and Egyptian pyramids, yet this was among the early impressions when we started the fieldwork. It was not inspired by weird fiction (although Egypt is frequently mentioned in Lovecraft’s stories; see Hite Citation2021, 98–108), but probably stems from the European ‘collective consciousness’ of Egypt as a land of ancient mysteries and (exoticised) otherness.

Hannukainen (like deserts, especially those associated with ancient and fabulous civilisations such as ancient Egypt) invites people to ponder on what lies underneath its surface, in the depths of this realm that is different from the ordinary human domain and potentially hostile to most humans. Like a desert, Hannukainen is ambiguous, shapeless and yet rich in shapes and constantly changing. There is more than meets the eye, things hiding under the surface that hint at the presence of something underneath, which also prompts exploration to get into and ‘see’ the place on a deeper level. This resonates with Lovecraft’s idea that ‘interest is in deeper and weirder topographies, not the world as it appears to us as we normally experience it, but the world as it is in its ultimate and deeper dimensions’ (Tabas Citation2015).

Labyrinth

Overall, the scale of the site combined with the peculiar interplay of forms and formlessness in the context of a general sense of emptiness made Hannukainen disorienting – there seemed to be ‘too much’ and ‘too little’ to it simultaneously. This of course readily echoes with the monotonousness and immensity of desert and sea, with both associations coming to our mind when pondering on the question of what kind of a place Hannukainen is. On the other hand, as indicated earlier, the more and the closer we engaged with the site, the more we started to see and otherwise sense in the place as we got gradually deeper into this landscape by circulating in it. Monotonousness, disorientation and gradually unfolding ‘more-ness’ evoked a sense of the labyrinth or suggested a general-level similarity with labyrinths ().

The spatial organisation and forms of the Hannukainen landscape have formally nothing to do with the classical (unicursal) labyrinth design, but metaphorically and ‘functionally’ there are similarities between the two that help to make sense of some aspects of Hannukainen and the way it affects people (or us, anyway). The labyrinth is a seemingly simple design, a spiral with rhythmic turns leading to the centre. The cultural histories and meanings of the labyrinth are too complex to be rehearsed here (see e.g. Conway Citation2013; Kern Citation2000; McCullough Citation2005), but there are four aspects to it that are relevant. First, the labyrinth is a rather ‘monotonous’ and repetitive design, which is, secondly, very much at the heart of its (transformative) power (seeing, revealing and connecting to the world differently; see Artress Citation1995; Doner Citation2022). Third, the labyrinth is associated with, and a passageway to, the extraordinary and otherworldly subterranean realm (on many levels); and fourth, there is, according to the classical myth, a monster in the labyrinth: the Minotaur.

The things that matter here are as follows. The labyrinth ‘works’ not by looking at the design from the outside, but by taking the path and walking along it through an environment that does not seem to change – curves and twists follow one another, and every curving bit of the path and every turn along the way leads closer to the ‘resolution’ of the path in the centre. Most importantly, however, walking a labyrinth is (potentially) a tool for ‘seeing’, connecting with and/or realigning one’s relationship with ‘invisible’ worlds in a similar manner to altered states of consciousness (see Artress Citation1995; Doner Citation2022). Altered states of consciousness afford perceiving aspects of reality that we are not ordinarily aware of, and can be (and have been) culturally signified in different ways: a mode of gaining deeper knowledge about the world or, as rationalism would have it, skewing what the world is really like (Greenwood Citation2009). In a manner of speaking, the labyrinth – like the Hannukainen landscape – could thus be conceived in terms of the ‘monstrous sublime’ (cf. Peeples Citation2011). In Lovecraftian terms, this could be thought of as a way of gaining glimpses of the reality beneath the thin veil of sanity that ordinarily ‘masks’ the horrifying reality; the ‘veil’ protects humanity from the monstrous chaos behind it – as if there is a monster roaming in the mythical labyrinth.

Etymologically, monsters have been associated with warnings, portents and, thus, with ‘revealing’ (Mittman Citation2012): this is also what altered states of consciousness are thought to do in various (shamanistic) contexts. In this context and view, there is again more than is readily obvious to the (disturbing) ‘emptiness’ of Hannukainen, which in turn is driven, first and foremost, by its ambiguous and ambivalent nature, hinting at environmental upheaval if not destruction. The labyrinth is a tool for perceiving and relating to the surrounding world differently, and so too is this mining landscape. Its ‘emptiness’ combined with a combination of shapes and shapelessness makes Hannukainen something like a gigantic Rorschach inkblot test: a canvas for cultural projections (of horror), which provides a tool for finding out things about ourselves as well as deeper dimensions of the world (cf. Luke Citation2010) with its ‘weirder topographies’ and temporalities, as in Lovecraft’s stories (see Carroll and Sperling Citation2020; Tabas Citation2015). Indeed, the disturbing feelings provoked by Hannukainen echoe the sense that ‘[l]iving in the Anthropocene implies that we are no longer at home, or that our home is no longer comfortable but filled with terrors and depths that are perhaps best captured by the metaphysics of the weird’, and ‘that the world has dimensions that exceed the grasp of our senses, but also that there are dimensions or depths to the real that exist beyond even those of science’ (Tabas Citation2015).

The dream-like spaces of Hannukainen were particularly evident in the presence and absence of animal life on the site. At several places we found dismembered pieces of reindeer: a hoof, a leg. Reindeer moving across the site create a powerful sense of unreality in the contrast between living animals – most commonly encountered in forests and open land – and the broken landscape of the mine. The soundscape of reindeer against the silent, abandoned mine was profoundly strange.

Overall, it comes as no surprise that Hannukainen, conceived in terms of monsters of the Anthropocene, is simply ‘too big’ and too complex to fathom in its entirety and, accordingly, impossible to describe properly – just as Lovecraft’s cosmic monsters are, as Harman (Citation2012) has discussed extensively. Lovecraft employed various literary techniques in an attempt to convey a sense of something that goes beyond description (Harman Citation2012). It is along the same lines that developing new ways of writing is required in archaeology. This is particularly acute in relation to human–thing–place–time relations in the age of the Anthropocene (Olsen and Pétursdóttir Citation2021), given that the Anthropocene is a ‘weirdly weird’ world (Ulstein Citation2022) with its massive scales, quantities and complex entanglements between things and phenomena extending literally and figurative beyond a proper human comprehension. We are, in a very real sense, living in an age of monsters and the monstrous, small, enormous and of uncertain size and nature. Venturing deeper and deeper into the labyrinth that is Hannukainen seemed to concretise such metaphysical and existential issues, whilst employing weird fiction as a tool for thinking about such matters affords ‘seeing’ and verbalising at least some aspects of them.

Our view on the Hannukainen landscape and how it affected us – and especially how we conceptualise it here – is likely quite different from how locals perceive it and how former mine workers would have related to it. We are, after all, outsiders to Hannukainen although familiar with it, whereas miners in particular would have known the landscape much more intimately – which resonates, at least on a general level, with our sense of the weirdness and monstrosity of the place. Namely, as we later came to learn later (and as noted above), memoirs of and interviews with Finnish mine workers from the late 1970s clearly indicate that miners’ perceptions of (underground) mines also tend to emphasise the strangeness of mines as places, including their implicitly and explicitly monstrous nature.

Stonehenge at a threshold

Apart from the overall distorted monumentality of its landscape, there are also smaller-scale ‘monumental’ features in Hannukainen. One in particular that puzzled us comprises a stone circle on a ‘roundabout’ by the gate to one of the two deeper quarries at the site. It is unclear whether it was constructed for this purpose, but there is a fireplace with ash and charcoal in the centre of the circle. However, it is a rather peculiar environment for recreational purposes. If the rocks were placed there to provide a setting for sitting around the fire, they are eminently uncomfortable for such a use: many of the rocks are quite un-sittable, they are far from both the fireplace and each other, and they are surrounded by a wasteland. Indeed, this place comes across as a mockery of a ‘domesticated’ human place and of the human instinct to sit in circles around a fire, reproduced on an impractically large scale – where scale is precisely the cause of discomfort and unease. Here, heavy machinery has been employed to transform and process a human landscape up to a point where its very structure and fabric feel as if they have collapsed into a ‘non-place’ that has a deeply non-human and monstrous feeling to it ().

We do not know anything about the intended purpose of the stone circle, if indeed it has any, or why it has been constructed in this specific location, but, intentionally or not, it strikes a resonance with Stonehenge and other such circular monuments. Yet its scale and measures feel strangely stretched or partly broken, which makes this ‘mini monument’ feel peculiar – Lovecraft’s ‘weird geometries’ come to mind again. Incidentally, we were struck by a similar feeling at another location some hundreds of metres outside the mine. We wondered about the place from a distance and thought that it was likely someone’s summer cottage pre- or post-mining in Hannukainen. One day we walked there to take a closer look and discovered a building that turned out to be an over-sized (wood)shed next to a small dug-out shelter, with some mundane artefacts scattered around (). The place was abandoned but left us very confused: why such a disproportionately large shed with a very small and likely uncomfortable shelter? Again, there was a prominent feeling of weirdness to this place. The ‘wrong’ proportions of the fireplace/stone circle and shelter/woodshed, and seeming mockery of the things they emulated, felt as if the ordinary order of things had started to fall apart here.

To further underline a sense of strangeness, a massive tank-like cylindrical container has been left by the stone circle and the gate to the water-filled quarry, reminiscent of the ‘zones’ in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, M. John Harrison’s The Kefahuchi Trilogy and Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, as places where the normal order of things has broken down in different ways and where strange objects and beings are found. The cylindrical object and the stone circle in their particular landscape setting were like a microcosm of the mine at large with its general sense of tension between structure and structurelessness. Whatever the story of the stone circle, its design and its placing by the gate to the now water-filled quarry were intriguing and resonated with Stonehenge as a place of the dead – a gateway or portal to an otherworld in a broadly similar sense to the labyrinth. Indeed, interestingly, stone labyrinths have been discovered at Sámi burial sites on the Norwegian Arctic Ocean coast (Olsen Citation1991). The Hannukainen stone circle by the gate to the quarry has a sense of a threshold to it and thresholds, in turn, are places where the this-worldly and otherworldly cross. It is unsurprising, then, that ‘Lovecraft’s fiction is explicitly concerned with thresholds, with metaphors of contact and transgression’ (Kneale Citation2006, 111).

The themes of threshold, contact and transgression all imply liminality, which very much lies at the heart of the affective power of the Hannukainen landscape. This underlines the significance of uncertainty as a characteristic of the place and makes it open to many different readings. Thus, although the Hannukainen landscape appears relatively static, it is not only physically but also metaphysically in a constant state of ‘becoming’. There is, moreover, an aspect of weird temporalities (cf. Carroll and Sperling Citation2020) to open-pit mining landscapes, as extraction and the associated moving of materials have very prominently ‘broken’ the ‘linear’ temporality of deep-time geological processes.

The ‘deeper’ we ventured into this liminal landscape, the more confusing and disorienting it became. This set us thinking about the meaning of a curious feature that was almost the first thing we spotted upon our arrival in the mine in 2022 and that had appeared there between then and our previous visit a year earlier. This feature is a compass rose constructed of rocks and oriented according to the compass points, with stone lines pointing to the cardinal directions and larger rocks marking the intermediate points of the compass between them (). We have no information about who built it or for what purpose. However, it might be connected, in one way or another, to the continued plans to reopen the mine and to various events – including art projects – that have been organised at the site. Whatever its story, the compass provides a contrast to the otherwise unordered, labyrinth-like and disorienting post-mining landscape of Hannukainen. In a way, it presents a point of contact with the ‘real world’ outside the mine and a symbolic attempt to bring order to the site.

Mines, holes and zones

Hannukainen is many things, but it is essentially a hole, or a set of holes in a hole. It was created by carving massive quantities of matter out of the ground. Consequently, Hannukainen is distinctively both a ‘negative’ and a ‘positive’ space. It is like a carving on a monstrous scale, which strikes resonance with the recurrent appearance of grotesque, non-human, carved reliefs in Lovecraft’s ancient non-human cities, which, moreover, often have distinctive subterranean dimensions to them. Hannukainen is a monstrous sculpture with otherworldly subterranean forms that monsters of the Anthropocene have released from below the surface of the ground, somewhat like Michelangelo considered himself ‘freeing’ forms that he saw and were already there in the marble that he worked on. The fact that Hannukainen as a monstrous sculpture is a secondary product or a by-product only underscores its horrendous character. This monstrous sculpture, moreover, has elements of (exposed) deep time to it, which brings an element of not only spatial disorientation to it, but also a sense of temporal vertigo, which further contributes to the disturbing and ‘unnatural’ character of the place, as transformed by monsters of the Anthropocene. Yet at the same time, some parts of this deeply transformed place look like a ‘natural’ Finnish lakeside landscape, hence adding to the sense of dissonance ().

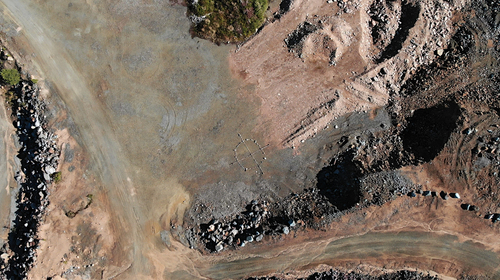

Hannukainen is a hole, but it does not necessarily come across as a hole, for although there are clear indications of cutting into the ground at the site, a massive heap of waste rock dominates the mining landscape, while the two water-filled quarries are quite inconspicuous (). In a sense, then, Hannukainen with its waste rock heaps looks, at least in places, something like an ‘inverted hole’. Like an eviscerated body, its insides are on the outside, but the insides have been exposed for so long that the mine’s boundaries and orientations have become obscured. It is a massive jumble of present absences and/or absent presences. This can be readily aligned with metaphysical (and bodily) horror which transcends or contradicts the ‘natural order’ of things, something that defies logic, reason and common sense ().

Holes into the ground are potentially unsettling landscape features – especially when as large as Hannukainen – because they are openings into weird subterranean realms in an experiential and cultural-cosmological sense and have been conceived in this way through centuries and millennia. Davies and Robb (Citation2004) discuss the practice of the increasing digging of holes and ditches (in ritual/ceremonial contexts) in the Neolithic and the Bronze Age from the perspective of communication with the (spiritual dimensions) of the subterranean realm. Bridge (Citation2015) considers the relations between aboveground and belowground in similar terms in contemporary (urban) environments. The underground world is generally invisible to people in ordinary everyday life, but sometimes holes appear and reveal the otherwise invisible realm (of underground infrastructure, for instance), which can be unsettling in showing dimensions or reality that are vitally important yet largely unfamiliar (Bridge Citation2015). In this way, mines and mining are the same: critically important to ancient and contemporary civilisation but at the same time alien to most people.

Holes violate the boundary between aboveground and belowground, which have metaphysical implications precisely because the underground realm is largely outside a proper domain of human life, an extraordinary and dangerous world that is radically different from aboveground. Exploring the underground realm in contemporary urban settings can reveal all kinds of strange places but also takes quite some effort (see Hunt Citation2019), and generally our dispositions – conscious or unconscious – towards the subterranean world are mediated by long-standing cultural imageries of it as a domain of non-human, including monstrous, beings and powers. The subterranean is a world where the sense of place and time and the ways that things work are radically different from aboveground. The long and deep legacies of the otherness and weirdness of the subterranean are still with us today (even if we may not consciously recognise them), as reflected in various forms in contemporary fiction and popular culture (Herva, Komu, and Paphitis Citation2022).

Seen against this background, the disturbing character of the (inverted) hole in Hannukainen can be put into a broader context that goes beyond ‘mere’ environmental destruction. That is, the mine as a whole and the strange structures and structurelessness and forms and formlessness in this landscape expose and display the weird and dangerous subterranean on an enormous scale. The desert-like general character of the site, with its massive heaps of waste rock is, or reflects, the chaotic nature of the subterranean that in various forms violates the structure and order of the ‘ordinary’ aboveground world; this landscape makes tangible the disturbing, otherworldly and potentially horrifying underground realm. The disturbing nature of the Hannukainen landscape, then, can be seen to result partly from its material and metaphysical ‘contamination’ – the subterranean has burst onto the surface and made it weird.

Examples from weird fiction can again be employed to illuminate this. In his short story ‘The Colour Out of Space’, Lovecraft tells the tale of a strange object from the skies hitting a remote farm in (his imaginary) New England. Gradually, things start to change with plants and animals becoming stranger in form and behaviour, and gaining monstrous qualities which are suggested to result from the contamination of the land by the object from an otherworld. Boundaries become unstable and violated at the site. In VanderMeer’s Annihilation, likewise, some kind of event creates a zone of weirdness. Researchers are sent to explore the zone and come to discover that biological structures are breaking apart and being recombined in weird ways, creating monstrous beings that cross species boundaries and the categories between plants, humans and animals, and where space–time also works in non-linear ways, hence making the entire zone a monstrous world. Although forms and structures in Hannukainen may not break down quite as radically and graphically as in VanderMeer’s zone, the place nonetheless has similar affective powers which, like Lovecraft’s monsters, are difficult or impossible to describe beyond approximations.

But there is a strong sense of wrongness to Hannukainen, which only increases as one spends time there exploring, sensing and thinking about it. It is not just that the pre-mining landscape of Hannukainen has been completely annihilated, but something has been broken in a deeper metaphysical sense, resulting in weirder monstrous topographies. Hannukainen may not be a hyperobject in the sense that Morton (Citation2013) defines it, but it has, in many ways, complex, uncertain and elusive boundaries, spatialities and temporalities, and can be regarded as a more-than-human entity. Extractive industries with their critical role and manifold entanglements with all aspects of the contemporary world and its making since early civilisations, on the other hand, could be considered as a monstrous hyperobject – not for its own sake, but as a heuristic tool for thinking about some weirder dimensions of our long-standing intertwining with mining.

Present and absent conclusions

Hannukainen is a dormant monster (cf. Ureta and Flores Citation2018) in the sense that there have long been plans and attempts to reopen the mine – and on a substantially greater scale than before. Therefore, Hannukainen provokes fears (and hopes) locally (see Komu Citation2020; Solbär Citation2021), and the current landscape comprises a tangible sounding board for such fears, not only in regard to the direct and readily present impacts of mining, but also their existential and metaphysical implications even if the latter are usually present on an unconscious level. Our exploration of and reflections on Hannukainen have tried to expose some of those higher-level (or deeper-level) issues and concerns that go ‘beyond the rational’ (Wright Citation2012; see also Komu Citation2020), but mediate contemporary perceptions of and relationships with extractive industries in significant ways.

Mines destroy and pollute the environment not only materially but also metaphysically, which we suggest is one reason why they are felt to be unsettling and disturbing. The mysterious and potentially threatening subterranean realm is released onto the ground and materialised in vast, dissonant and monstrous landscapes characterised by an interplay of shapes and shapelessness, forms and formlessness, with this weirdness echoing the age-old ideas and perceptions of underground as an otherworldly domain. These ideas and perceptions continue to be reproduced in contemporary fiction and popular culture which provide an echo chamber for unsettling emotions provoked by mining and mining landscapes, as explored in this article in relation to Hannukainen. Directly and indirectly, much of our assessment of Hannukainen revolved around presences, absences, present absences and absent presences. Overall, this interplay of presences and absences generated uncertainty and disorientation, and compromised the very coherence of Hannukainen as an experienced landscape, placing it in a weird in-betweenness of non-linear spatialities and temporalities associated with monsters and the monstrous.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the editors and anonymous referees for their helpful comments. This article is part of the research project ‘Extractive Industries as Engagement with the Extraordinary Subterranean: Culture, Heritage and Impact of Resource Extraction in Northernmost Europe’ (Extraordinary Underground).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Artress, L. 1995. Walking a Sacred Path: Rediscovering the Labyrinth As a Spiritual Practice. New York: Penguin.

- Bridge, G. 2015. “The Hole World: Scales and Spaces of Extraction.” Scenario Journal 5 [ online article]. https://scenariojournal.com/article/the-hole-world/.

- Campbell, P. B. 2021. “The Anthropocene, Hyperobjects and the Archaeology of the Future Past.” Antiquity 95 (383): 1315–1330. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.116.

- Carroll, J. S., and A. Sperling. 2020. “Weird Temporalities: An Introduction.” Studies in the Fantastic 9 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1353/sif.2020.0000.

- Conway, J. 2013. “Monstrous Labyrinths: Hellish Prisons, Liberated Language.” Monsters and the Monstrous 3 (1): 41–52.

- Davies, P., and J. Robb. 2004. “Scratches in the Earth: The Underworld as a Theme in British Prehistory, with Particular Reference to the Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age.” Landscape Research 29 (2): 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390410001690383.

- Doner, J. 2022. “The Dynamic Uncertainty of Narrative, Place, and Practice in Spiritual Experience: Clues from the Phenomenology of Walking a Labyrinth.” Archive for the Psychology of Religion 44 (3): 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/00846724221131149.

- Ey, M., and M. Sherval. 2015. “Exploring the Minescape: Engaging with the Complexity of the Extractive Sector.” Area 48 (2): 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12245.

- Ey, M., M. Sherval, and P. Hodge. 2017. “Value, Identity and Place: Unearthing the Emotional Geographies of the Extractive Sector.” The Australian Geographer 48 (2): 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2016.1251297.

- Friedman, T. 2010, February 17. “Global Weirding Is Here.” New York Times, Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/17/opinion/17friedman.html.

- Gandy, M. 2016. “Unintentional Landscapes.” Landscape Research 41 (4): 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2016.1156069.

- Gonzales, A. A., and C. H. Sederholm, eds. 2021. Lovecraft in the 21st Century: Dead, but Still Dreaming. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Greenwood, S. 2009. The Anthropology of Magic. Oxford: Berg.

- Harman, G. 2012. Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Winchester: Zero Books.

- Herva, V.-P. 2021. “Minoan Lapland: Fieldwork, Spirituality and Connecting Across Time and Space.” Time and Mind 14 (3): 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/1751696X.2021.1951561.

- Herva, V.-P., T. Komu, and T. Paphitis. 2022. “Extraordinary Underground: Fear, Fantasy and Future Extraction.” In Resource Extraction and Arctic Communities: The New Extractivist Paradigm, edited by S. Sörlin, 166–182. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Herva, V.-P., and A. Lahelma. 2020. Northern Archaeology and Cosmology: A Relational View. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hite, K. 2021. Tour de Lovecraft: The Destinations. Alexandria, VA: Atomic Overmind Press.

- Holloway, J. 2017. “On the Spaces and Movements of Monsters: The Itinerant Crossings of Gef the Talking Mongoose.” Cultural Geographies 24 (1): 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474016644759.

- Houellebecq, M. 2005. H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life. London: Gollancz.

- Hunt, W. 2019. Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Joshi, S. T. 2010. I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H.P. Lovecraft. New York: Hippocampus.

- Keeling, A., and J. Sandlos. 2017. “Ghost Towns and Zombie Mines: The Historical Dimensions of Mine Abandonment, Reclamation, and Redevelopment in the Canadian North.” In Ice Blink: Navigating Northern Environmental History, edited by S. Bocking and B. Martin, 377–420. Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

- Kern, H. 2000. Through the Labyrinth: Designs and Meanings Over 5000 Years. Munich: Prestel.

- Kneale, J. 2006. “From Beyond: H. P. Lovecraft and the Place of Horror.” Cultural Geographies 13 (1): 106–126. https://doi.org/10.1191/1474474005eu353oa.

- Komu, T. 2020. Pursuing the Good Life in the North: Examining the Coexistence of Reindeer Herding, Extractive Industries and Nature-Based Tourism in Northern Fennoscandia. Oulu: Acta Universitatis Ouluensis.

- Loponen, M. 2019. The Semiospheres of Prejudice in the Fantastic Arts: The Inherited Racism of Irrealia and Their Translation. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Luke, D. 2010. “Rock Art or Rorschach: Is There More to Entoptics Than Meets the Eye?” Time and Mind 3 (1): 9–28. https://doi.org/10.2752/175169710X12549020810371.

- McClanahan, B. 2020. “Earth–World–Planet: Rural Ecologies of Horror and Dark Green Criminology.” Theoretical Criminology 24 (4): 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480618819813.

- McCullough, D. W. 2005. The Unending Mystery: A Journey Through Labyrinths and Mazes. New York: Anchor Books.

- Mittman, A. S. 2012. “Introduction: The Impact of Monsters and Monster Studies.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, edited by A. S. Mittman and P. J. Dendle, 1–14. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Morton, T. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Muhonen, T. 2008. “Something Old, Something New: Excursions into Finnish Sacrificial Cairns.” Temenos 44 (2): 293–346. https://doi.org/10.33356/temenos.4592.

- Musharbash, Y. 2014. “Introduction: Monsters, Anthropology, and Monster Studies.” Monster Anthropology in Australasia and Beyond 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137448651_1.

- Naum, M. 2019. “Enchantment of the Underground: Touring Mines in the Early Modern Sweden.” Journal of Tourism History 11 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2019.1592241.

- Olsen, B. 1991. “Material Metaphors and Historical Practice: A Structural Analysis of Stone Labyrinths in Coastal Finnmark.” Fennoscandia Archaeologica 8:51–58.

- Olsen, B., and Þ. Pétursdóttir. 2021. “Writing Things After Discourse.” In After Discourse: Things, Archaeology and Heritage in the 21st Century, edited by B. Olsen, M. Burström, C. DeSilvey, and Þ. Péturdsóttir, 23–41. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Peeples, J. 2011. “Toxic sublime: imaging contaminated landscapes.” Environmental Communication 5 (4): 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2011.616516.

- Solbär, T. L. 2021. “The Belief in Mining: How Imageries of Other Mines May Brighten Arctic Minescapes.” The Polar Record 57 (e44): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247421000188.

- Tabas, B. 2015. “Dark Places: Ecology, Place, and the Metaphysics of Horror Fiction.” Miranda 11 (11). [Online]. https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.7012.

- Tsing, A., H. Swanson, E. Gan, and N. Bubandt, eds. 2017. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, 103–121. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Turnbull, J., B. Platt, and A. Searle. 2022. “For a New Weird Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 46 (5): 1207–1231. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221116873.

- Ulstein, G. 2021. “Weird Fiction in a Warming World: A Reading Strategy for the Anthropocene.” PhD thesis, University of Gent.

- Ureta, S., and P. Flores. 2018. “Don’t Wake Up the Dragon! Monstrous Geontologies in a Mining Waste Impoundment.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (6): 1063–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818780373.

- Varner, G. R. 2004. Menhirs, Dolmen, and Circles of Stone: The Folklore and Magic of Sacred Stone. New York: Algora.

- Wengrow, D. 2014. The Origins of Monsters: Image and Cognition in the First Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Wright, S. 2012. “Emotional Geographies of Development.” Third World Quarterly 33 (6): 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2012.681500.