ABSTRACT

Context-sensitivity appears to be a key factor in developing the knowledge base of coaching as a change process. As an alternative perspective to the more widely held cause–effect explanations on coaching, this view puts the focus on clients and their contexts as integral to understanding how coaching might work and why it is effective. In response to general limitations of quantitative and mixed-method approaches to understanding the contribution of client factors and contextual factors in coaching effectiveness, our systematic meta-synthesis of 110 peer-reviewed qualitative studies identifies the client factors and contextual conditions that have been proposed to affect when and how clients engage in effective coaching. In mapping clients’ intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics in coaching, the Integrative Relationship Model introduced in this meta-synthesis interprets the possible influence of these dynamics on clients’ change process through the uniquely integrative lens of qualitative studies. This integrative perspective appears necessary to give quantitative researchers future directions in how to investigate coaching effectiveness.

Practice points

The main focus is on clients’ self and their social world as they interrelate in coaching to examine and understand clients’ nuanced behaviours

We apply a patterned meaning-making approach to imply that coaching is a dynamic set of intrapersonal and interpersonal interactions

Tangible implications are:

o emphasising the significance of emotion in explaining why clients do what they do

o indicating how clients’ interrelatedness with their context impacts their learning

Introduction

Mapping out the territory

There is a recent shift from ‘how to coach’ to ‘what impacts clients’ learning’ (e.g., Jones et al., Citation2016) in coaching as a context-sensitive change process (e.g., Athanasopoulou & Dopson, Citation2018). There is a major theoretical consideration. The context-sensitive process approach implies that coaching is more than a mere coach-client learning-based intervention. Cox et al. (Citation2014) view coaching as subject to fluctuations of the properties of the coach, the client, the coach-client relationship and various contextual factors and claim that it is more than an input-output cause–effect activity. As such, the context-sensitive process approach is an alternative perspective to the more widely held cause–effect explanations (Cavanagh, Citation2013) on coaching practice. Against this conceptual framework, we place coaching as a purposeful meaning-making process (Drake, Citation2015) in a context that may explain emergent client characteristics making this interactive learning system dynamic without any links to specific methodical approaches (Bachkirova & Lawton Smith, Citation2015). In doing so, we investigate client factors and contextual dynamics in coaching as a context-sensitive change process. The aim is to complete our understanding of which client factors impact clients’ learning and how contextual dynamics play out in clients’ change process as reported in the articles reviewed in this qualitative meta-synthesis.

Reviewing earlier literature

One persistent debate in relation to the contextual character of coaching revolves around the interrelatedness of client factors as they contribute to coaching outcomes (Passmore, Citation2007) both in clients’ proximal (De Haan & Nieß, Citation2015) and distal context (Terblanche, Citation2014). Investigating this interrelatedness potentially enhances our understanding of how coaching works (e.g., Bozer & Jones, Citation2018) as a dynamic set of intrapersonal and interpersonal interactions (e.g., Palmer & McDowall, Citation2010). Our aim is to complete our insight into how to facilitate clients’ change process and goal attainment in the future. We wish to inspire future qualitative and quantitative research into coaching as a context-sensitive change process.

Thus far, coaching research reveals that clients’ responses such as trust (e.g., Gyllensten & Palmer, Citation2007) commitment (e.g., Gregory et al., Citation2008) and self-efficacy (e.g., De Haan & Duckworth, Citation2012) are the most influential ‘active ingredients’ (McKenna & Davis, Citation2009) for positive coaching results. However, the majority of primary studies examining the role and contribution of the client in coaching effectiveness have drawn primarily on quantitative approaches. As such, they are focused on hypothesis-testing and cause–effect relationships with studies relating to only a few client factors as isolated active ingredients (e.g., self-efficacy). They do not account for coaching as a change process. This is unfortunate as we might miss the prevalence of relevant client factors that potentially impact clients’ learning. At the same time, we might also miss the manner in which client factors interrelate with clients’ proximal and distal contexts as dynamic change process.

Adopting a purely interpretative approach

Generally, our coaching practice grows continuously and we still have only limited scientific evidence about the most effective coaching interventions. We need more inspiration from research to think about how coaches can be more effective. Specifically, we need a bridge between qualitative research and coaching practice as we understand it through quantitative research by making qualitative research more accessible to practitioners. Practitioners need guidance in working with clients as they have many choices to make. They need a richer evidence base to be credible towards clients. Reviewing purely qualitative primary research to explore the interrelatedness of client factors and contextual factors may help as findings can deepen our understanding of coaching, particularly when we view coaching as a context-sensitive and dynamic change process.

Quantitative research has contributed to our understanding of clients’ role in coaching effectiveness. Yet, findings are limited in one main aspect: the need to isolate general client factors in quantitative research inevitably leads to fragmented findings (Ely et al., Citation2010). Isolating factors misses the potential interrelatedness of client factors and contextual factors present in clients’ goal-attainment. We risk missing the relevance of such interrelatedness for coaching as a context-sensitive and dynamic change process. This limitation has left coaching outcome research open to accusations of theoretical imprecision given the under-regulated and varied nature of the practice (Western, Citation2012). As a result, some scholars (e.g., de Haan, Citation2019) emphasise the significance of reviewing client factors through a process-oriented lens of qualitative studies to identify patterned shifts for clients. They argue that such an approach could overcome this limitation by sensitising researchers and practitioners to how the multicity of client factors plays out in coaching as intrapersonal outputs (e.g., Ianiro & Kauffeld, Citation2014) shaped by contextual influences across sessions and over time. Moreover, some scholars (e.g., Day, Citation2010) recognise that gaining a deeper understanding of the patterned dynamics of clients’ internal world as revealed in their interrelatedness and as they emerge in clients’ social contexts is necessary before we can claim to fully understand coaching. In providing insight into how these factors interrelate, qualitative literature is believed to ‘yield truths that are better, more socially relevant, or complete’ (Paterson et al., Citation2001, p. 111). Hence, it enhances our theoretical understanding of the multicity of factors involved in coaching engagements (Bachkirova, Citation2017) or guides coaches’ actions (e.g., Drake, Citation2015).

Despite scholarly calls (e.g., Myers, Citation2017) for coaching process researchers to systematically review primary qualitative studies as the new conceptual route, the conceptualisation of clients’ goal-attainment has remained limited to systematic reviews focusing exclusively on either quantitative studies (e.g., Jones et al., Citation2016; Sonesh et al., Citation2015; Theeboom et al., Citation2014) or mixed-method approaches (e.g., Athanasopoulou & Dopson, Citation2018; Bozer & Jones, Citation2018) or specific types of coaching (e.g., Lawrence, Citation2017). These reviews do not explain the dynamic interrelatedness of the client factors or contextual factors that were found to determine coaching effectiveness.

Systematic questions

Most recently, de Haan’s (Citation2019) first systematic review of 101 qualitative publications in workplace and executive coaching highlighted the coach-client related success criteria (i.e., development of trust in, acceptance of and commitment to coaching, capacity to agree on tasks and goals, the coachee’s adherence to the coaching contract, a shared psychological understanding and newly gained insight). De Haan’s (Citation2019) systematic qualitative review sets the stage for our research questions:

Q1: which client factors and contextual factors reported in primary qualitative studies are relevant for coaching effectiveness, and

Q2: how do primary qualitative studies suggest that these factors interrelate in clients’ learning as a context-sensitive and dynamic change process.

Contribution of this paper

The contribution of this qualitative meta-synthesis is two-fold. First, we provide a pervasive picture of client factors aggregated as emotion, attitude and behaviour. Through interpretive synthesis as a patterned meaning-making approach, we provide more manageable means of analysis for researching how client factors might interrelate in clients’ change process. The aim is to deepen our understanding of the dynamic nature of coaching. We emphasise the significance of emotion as an under-researched and under-theorised factor in explaining why clients do what they do in coaching. This emphasis gives researchers future directions in how to investigate coaching effectiveness. Second, in applying a process-oriented lens, we develop an Integrative Relationship Model (IRM) to depict the patterned interrelatedness of the client factors and contextual factors that are proposed to affect when and how clients might engage in coaching as a context-sensitive process. It is this context-sensitive approach to change processes that we elucidate for a deeper understanding of clients’ intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics as a linchpin of their learning. This is useful to conduct future quantitative investigations of how to facilitate change towards effective goal-attainment in coaching psychology and management development beyond the impact of selective variables (Myers, Citation2017).

Methodology (Exhaustive methodology available as supplemental online material)

Qualitative meta-synthesis (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007) was selected as an acknowledged methodology in social sciences (e.g., Siddaway et al., Citation2018) and management (e.g., Tranfield et al., Citation2003) to inductively conceptualise client factors and contextual factors and to answer Q1 and Q2. Induction lends itself to explaining some lawful relationships between social experiences (Gephart, Citation2004) through interpretation. Qualitative meta-synthesis is a valuable tool for exploring the (a) depth (given the qualitative approach) and (b) breadth (given the integration of primary studies from various coaching contexts and participant groups) of client factors and contextual factors in primary qualitative studies. In elucidating research gaps, related fields like psychotherapy (e.g., Lachal et al., Citation2017) systematically recur to qualitative meta-syntheses to inform the development of quantitative research. Our purpose is to advance our knowledge of how to design, implement and evaluate coaching interventions as this has been achieved successfully in the field of health interventions (e.g., Tong et al., Citation2012). Table 1 (supplemental online material) provides a comprehensive protocol following the seven aspects of qualitative meta-syntheses (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007) and is guided by reporting standards as discussed by Tong et al. (Citation2012) and Hoon (Citation2013).

Systematic literature search

The search strategy involved searching all the available concepts iteratively. This approach required re-engaging with literature in a purposive way (Patton, Citation2002) and stimulated adaptations of the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

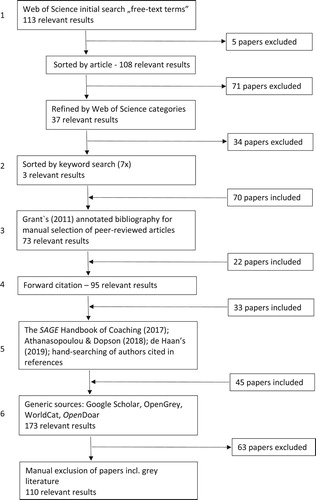

The entire search strategy was performed in six steps ().

First, the primary database selected for records is the ISI Web of Science as it counts among the most comprehensive interdisciplinary databases (integrating EBSCOhost, PsychInfo, ProQuestion) of high-impact peer-reviewed journals in the social sciences. The initial search based on the free-text terms ‘coaching’, ‘coaching process’, and the combination with the methodological filter ‘qualitative research’, but NOT ‘sport’, and NOT ‘med*’, sorted by articles and refined by Web of Science database categories and search strings yielded 113 hits. Second, we added keywords to refine search results. While the client as an influencing factor has evolved into a key area of study, there is remarkably little consistency in the terminology (Greif, Citation2017). The keywords used to denote the client as an influencing factor were ‘client’, ‘coachee’, ‘success factor’, ‘outcome criteria’ and ‘antecedent’ as scoped by Ely et al. (Citation2010) and Greif (Citation2017). This addition yielded one (n = 1) relevant result and was then further complemented with the labels ‘active ingredients’ (McKenna & Davis, Citation2009) and ‘common factors’ (De Haan, Citation2008) to establish further variants (n = 9), as recommended in bibliographic database search (Page, Citation2008). This approach yielded two (n = 2) relevant results. As primary qualitative papers on coaching are underrepresented in the high-impact journals recorded in Web of Science, the impact factor of the journals was eventually not accounted for. Third, Grant’s (Citation2011) annotated bibliography of scholarly publications served as a secondary basis for a thorough manual selection of solely peer-reviewed articles that use qualitative research methodologies. This scanning approach resulted in the identification of seventy publications (n = 73). Fourth, this set formed the basis for a tertiary strategy of forward citation, and the purposive sampling process resulted in the identification of additional relevant papers (n = 95) including inter alia doctoral dissertations, both published and unpublished, pertinent to the review question. Fifth, to avoid missing potentially relevant and most recent records the volume The Sage Handbook of Coaching (2017) edited by Tatiana Bachkirova, Gordon Spence and David Drake was screened for relevant peer-reviewed articles (until January 2017) as well as Athanasopoulou and Dopson’s (Citation2018) and de Haan’s (Citation2019) most recent systematic literature reviews of qualitative studies. These tertiary methods resulted in the hand-searching of authors cited in the reference lists of these works. Additional studies pertinent to the review questions were located (n = 45). Sixth, the systematic search also included more generic electronic sources such as Google Scholar, OpenGrey, WorldCat, and OpenDOAR. Articles published after December 2019 are not included in the search hits. A total of 173 references were exported to a summary table and categorised by type of study, title, author, journal, number of participants, and research paradigm. Electronic and hard copies of publications were obtained to appraise whether (a) articles met inclusion criteria, (b) inclusion criteria required further adaptations, and to identify (c) the methodological perspectives and focus of studies (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007).

Inclusion & exclusion and quality appraisal

First, an initial inclusion/exclusion question was formulated (i.e., ‘What is the evidence of clients’ characteristics investigated?’) to determine whether the 173 articles fit Q1. Second, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP; National CASP Collaboration, Citation2006) was selected as a set of criteria (10 Questions to Help you Make a Sense of Qualitative Research) along which to systematically appraise the quality of primary qualitative studies and to assess the articles collected for inclusion/exclusion. Third, a three-level weighting approach (primary, secondary, tertiary) served as a means to establish the performance of the articles for each CASP category. Studies that sufficiently answered the research questions were not excluded based on the research design even if they included certain secondary quantitative elements (e.g., questionnaires, descriptive statistics). Some articles (n = 63) were excluded as the abstracts turned out to relate to topics that were not coaching-specific, or because papers did not answer the research questions or failed to describe methodical criteria (e.g., outcome study, study review). Grey literature (e.g. books, book chapters) was excluded as papers did not meet CASP criteria. Table 2 (supplemental online material) provides the list of the primary qualitative articles included in this meta-synthesis.

Eventually, this qualitative meta-synthesis includes only empirical work on coaching generally, as published in peer-reviewed journals to attain highest quality in synthesising primary qualitative studies. Additionally, it includes published and unpublished doctoral dissertations. Dissertations are rigorous peer-reviewed papers that contain rich and methodologically robust procedures and are likely to produce reliable and valid outcomes. Conversely, action research (e.g., Reason & Bradbury, Citation2001) thesis papers were found to be unsuitable for the purposes of this qualitative meta-synthesis. The reason is that coaches focus on their learning from a perspective of first-person enquiry. The 1990s were chosen as the starting point for inclusion. This synthesis includes English-only (American and British) articles.

Data collection and extraction

In collecting and extracting data from the final set of 110 articles, a simple cross-study data display was created as a system by which to extract contextual and client-factor dynamics as a basis for performing a line-by-line identification of qualitatively unique distinctions drawn by authors in the studies. The cross-data display identifies the following descriptors found in each study: (a) full citation for articles; (b) context (e.g., coaching setting and approach, client characteristics); (c) data analysis supported by direct quotes; (d) categories, (e) subcategories and themes reported (data can be obtained upon request). The trustworthiness and transferability of results were determined by the level of quality of reporting sought or achieved in the primary studies (e.g., consistent triangulation, saturation) as explained in data analysis and synthesis below.

Qualitative data analysis and synthesis

The analytical method selected for generating themes is known as thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). As is typical for conducting a qualitative meta-synthesis, this synthesis inevitably is only one possible interpretation of the data (Kinn et al., Citation2013). To establish triangulation in assessing the rigour and quality of the analytical process (e.g., Barry et al., Citation1999), two coaches were invited into the process of considering the same data set. Data analysis was applied in two stages.

Data analysis: stage one

First, a thorough rereading resulted in the clustering of articles by five distinct method types (Table 3 supplemental online material). Clustering raised the question of how to treat qualitative research in terms of methodical rigour. It was decided that articles in which the mixed-method approach was not dominant and in which content or structural analysis was based on qualitative data collection would be included in this meta-synthesis. All five primary research methods that emerged from the sampling process were included as relevant for measuring credibility, dependability and transferability of findings. Table 3 (supplemental online material) maps the explicit aspects along which the qualitative studies were distributed in terms of trustworthiness. Most importantly, the level of transparency of the research methods reported in the studies began to serve as a basis for how to identify with greater confidence what is trustworthy and transferable in terms of findings.

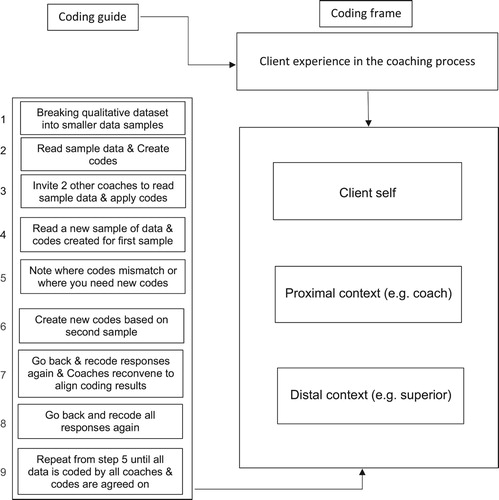

All descriptions/extracts related to client factors and contextual factors were listed in a spreadsheet to review the individual substance of data along a coding guide. This coding guide served as a coding frame for categorising codes and was shared with the two coaches as co-coders ().

Figure 2. Coding guide and coding frames for categorising codes guided by Barry et al. (Citation1999).

Data analysis: stage two

To categorise codes, stage two involved three types of coding as described by Strauss and Corbin (Citation1990): (a) open coding of findings specific to each study type to create concepts; (b) axial coding across the open codes to generate conceptual categories; (c) theoretical coding across the categories towards aggregating dimensions as themes. Eye-balling (Yin, Citation1994) was applied as an inductive technique to draw interpretive conclusions.

In categorising codes, it became apparent that researchers apply different language to describe similar themes. For instance, readiness for coaching is described as willingness to be coached, openness to the process (e.g., Bush, Citation2005), willingness to try out new behaviour or to change (e.g., Hurd, Citation2009), willingness to look at stuck situations (e.g., Kets de Vries, Citation2013), or preparedness (e.g., Peterson & Millier, Citation2005) in their studies, to name but one theme. Thus, in this analysis stage the question arose how the ‘ambiguous identity’ (Corley & Gioia, Citation2004) of some nascent concepts such as willingness, openness and readiness support the description and explanation of the client factors under review through adequate theoretical referents. Despite linguistic dissonances around a myriad of codes, three distinct aggregate dimensions emerged as the result of the analytical process of building a data structure.

Eventually, the emergent themes were further distilled into ‘aggregate dimensions’ (Corley & Gioia, Citation2004). The three aggregate dimensions are coded as: emotion, attitude, behaviour as described in the Finding section below. provides a summary of the primary qualitative study types split by aggregate dimensions and context.

Table 1. Summary of primary qualiative study types split by aggregate dimensions & context.

Figure 3 (supplemental online material) is a graphic representation of the generation of coded themes and aggregation into client-factor dimensions.

Data synthesis

In a third stage, the themes were synthesised within and across primary studies to ‘produce a new and integrative interpretation of findings that is more substantive than those resulting from individual investigations’ (Finfgeld, Citation2003, p. 894) and thus to inductively ground theoretical framework on emerging concepts derived from evidence collected.

In identifying signs of interrelatedness between the three aggregate dimensions, stage three incorporated the following activities: (a) constant comparison between aggregate dimensions and interpretations with outcomes at individual study level to identify potential meta-biases (e.g., primary research studies that did not fit within the current array of concepts, constructs and themes; lack of coherence of interpretive explanations), (b) translating studies into one another to draw cross-case conclusions, (c) synthesising themes in the form of an integrative conceptual model, and (d) theoretical sampling to build confidence in the cumulative evidence by accounting for differences between the client factors and contextual factors in relationship to the emerging conceptual framework.

In maintaining quality control, best practice guidelines for synthesising primary qualitative findings (Dixon-Woods et al.,Citation2007) formed the basis for applying the following procedures to ensure quality control: (a) creating transparency throughout the synthesis process by providing in-depth descriptions and explanations for decisions taken in this meta-synthesis; (b) employing two coaches as co-coders; (c) incorporating established methods to synthesise primary qualitative studies; (d) utilising established quality appraisal tools; and (e) using an audit trail for documenting decisions and agreements negotiated with co-coders.

Findings

Overview of client factors and contextual factors

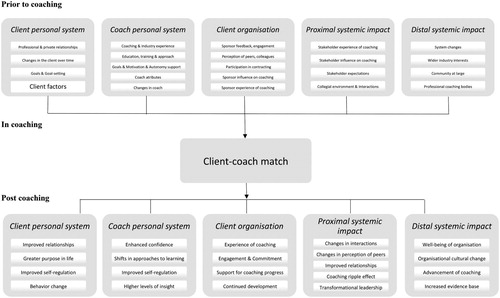

First, in the analytic phase, this qualitative meta-synthesis produced three emerging client-factor aggregate diimensions: (a) behaviour is found to be studied most extensively (n = 97), (b) followed by attitude (n = 75), while (c) emotion is found to be studied least extensively (n = 22). For this synthesis, emotion is the dimension that is rooted in basic needs and involves feeling (). It is understood to have varying impact on and to be impacted by the other aggregate dimensions across study types. Attitude manifests itself in the way clients view the world. Attitude bears varying effects and is affected by the other aggregate dimensions across study types. Behaviour reflects competencies and certain inclinations in interpersonal communication as reported in the primary qualitative studies that is partly conditioned by the coach’s behaviour as a coping style as well as the other dimensions across study types. Second, in the analytic phase, the qualitative meta-synthesis also produced a fourth aggregate dimension (n = 72). This dimension relates to the distal and proximal contextual factors as they are reported in the primary qualitative studies to influence clients’ change process. maps the embeddedness of the four aggregate dimensions in clients’ change process.

Figure 3. Client factors and embedded in contingencies (based on Grant, Citation2017).

While these four aggregate dimensions comprehensively describe client factors and contextual factors present in coaching, descriptions do not explain how these coded dimensions interrelate when it comes to clients’ learning in coaching (e.g., how trust in coaching relates to clients’ readiness to be coached).

To sustain a theoretical framework of interrelatedness of coded dimensions emergent thtough interpretation in this meta-synthesis, our narrative presentation below includes verbatim quotes from primary qualitative studies to capture the meaning of the dynamic patterns derived from interpretive synthesis. Verbatim quotes indicate how aggregate dimensions interrelate, that is how client factors and contextual factors impact on or are impacted by one another. Table 5 (supplemental online material) provides a summary of the frequency of interrelatedness for the four aggregate dimensions as dimensional dynamics across all study types.

Interrelating client factors and contextual factors

Interrelating client factors

One theoretical lens that has previously investigated how clients learn in coaching is Hampson’s (Citation2012) personality process theory. It affords to target the direct (i.e., one factor impacting on some other factor) and indirect (i.e., one factor impacting on some other factor via a third factor) interrelatedness of client factors as well as the direct and indirect effects of contextual factors on outcomes. While the primary qualitative studies under review do not use quantitative descriptors to describe change processes in coaching, concepts (e.g., trust, anxiety) are nevertheless found to refer to as mediating in some studies (e.g., Wales, Citation2003) or being a ‘predictor’ (e.g., Peel, Citation2008) to suggest correlationality with coaching effectiveness. Ultimately, in this meta-synthesis, only the existence of a certain type of dimensional interrelatedness can be ascertained through interpretation on the basis of verbatim quotes. Apart from presenting dimensions as being directly interrelated using descriptors (e.g., a factor ‘affects’, ‘impacts on’, ‘leads to’, ‘relates to’, ‘results from’ another factor) or indirectly interrelated (e.g., one factor leads to another factor through a third factor), the verbatim quotes in the qualitative studies refer to dimensions as positively (e.g., ‘facilitate’, ‘improve’, ‘will increase’, ‘is likely to lead to’) or negatively (e.g., ‘reduce’, ‘might impede’, ‘inhibit’) affecting the way in which clients progress in coaching across all study types (Table 2 (supplemental online material)). In some cases, in the absence of clear descriptors, the coders recurred to their knowledge and experience of coaching to define the positive or negative quality of dimensional interrelatedness (e.g., Cavicchia, Citation2010). To illustrate dimensional interrelatedness as mapped in Table 5 (supplemental online material), this meta-synthesis provides some examples of verbatim quotes as they were combined to form dimensional dynamics to answer Q1. For the sake of conciseness, we do not report all the dynamic patterns through verbatim quotes identified in the 110 qualitative studies (data can be obtained on request).

In a study using descriptive statistics (Cavicchia, Citation2010), shame defined as ‘clients’ emerging self-image of deficiencies inhibits spontaneity and improvisation’ as a capacity (attitude→behaviour). It is described as (negatively) influenced by ‘clients’ susceptibility to feeling unaccepted’ (emotion→attitude) and (positively) by ‘making use of ‘relational bridge’ (behaviour→attitude). In their case study, Kiel et al. (Citation1996) suggest that clients’ ‘fears of losing winning formulas’ and ‘fear of change as ‘hidden agendas’ lead to resistance and reduced leadership effectiveness’ (emotion→behaviour) and might be (positively) influenced by ‘levels of psychological mindedness and trust’ (attitude→behaviour). Alvey and Barclay (Citation2007) explain how clients’ ‘receptivity to coaching’ and ‘willingness to disclose honest feelings’ might ‘foster development of trust’ (behaviour→attitude). Huggler’s case study (Citation2007) postulates that clients’ ‘idealizing (seeing the coach as all wise and perfect)’, ‘mirroring (wishing to be loved and admired by coach)’, ‘twinship’(wishing to imitate and be like coach)’, might be (positively) influenced by clients’ ‘collaboration’ in the coaching (behaviour→emotion) via clients’ ‘trust’, which is reported to (positively) ‘impact their capacity to collaborate’ (attitude→behaviour).

Interrelating client factors and contextual factors

Similar to the dimensional interrelatedness of client factors described above, contextual factors manifest in a dynamic manner in the coaching process across all study types. They form the basis for interpreting when and how clients engage in coaching and thus reflect the socially constructed nature of coaching. For this meta-synthesis, contextual factors refer to past and/or present milieu-related conditions specific to the coach or client having either proximal or distal impact. They affect and are affected by the other dimensions and are inherent in the circumstances governing a situation (e.g., coach system, client system, client-coach relationship, organisational support). Both more proximal contextual dynamics (e.g., coach’s motivation affects client’s perceived level of engagement), the coaching engagement (e.g., client-coach match) and clients’ more distal contextual dynamics (e.g., executive level support, coaching culture increase clients’ self-confidence and sense of agency) are derived from the qualitative studies. To illustrate dimensional interrelatedness as mapped in Table 5 (supplemental online material), this meta-synthesis provides some examples of verbatim quotes as they were combined and constantly compared to form dimensional dynamics. For the sake of conciseness, we do not report all the dynamic patterns through verbatim quotes identified in the 110 qualitative studies (data can be obtained on request).

Cavicchia’s (Citation2010) article is one example which gives inspiration for how to interpret client factors and contextual factors. The author finds that shame will (negatively) ‘impact the coaching relationship as an unproductive pattern of relating’ (attitude→context). This study also explains how clients are impacted, albeit ‘subtly’ by the coach, which (positively or negatively) ‘contributes to the feeling and thoughts that arise, the work that unfolds, and the learning that occurs – for both!’ (context⇢emotion; context⇢attitude). A recent study (Noon, Citation2018) exploring presence illustrates how ‘being physically interrupted by coach supports clients’ regaining engagement’ (context→behaviour) as well as how coaches’ ‘making eye contact or direct feedback from coach facilitates clients’ presence’ (behaviour→attitude), which implies that coach as a context through own behaviour had a positive impact on client (context⇢attitude). Huggler (Citation2007) finds that ‘narcissistic clients’ collaboration is (positively) related with affect containment’ (emotion→behaviour) ‘through coaches’ empathic attunement’ (context⇢emotion), which ‘builds up trust’ (context→behaviour). Mansi (Citation2007) reports that clients’ ‘empathy, level of guilt, anxiety impact on their effectiveness as learders’ through extreme levels of volatile behaviour including angry outbursts, hostile verbal and non-verbal communication’ and that ‘will have potentially disastrous consequences for the individual and their organization’ (emotion→behaviour; emotion⇢context). Based on 56 critical moments De Haan (Citation2008) indicates that clients’ ‘turn calm as they are positively affected by coaches’ calmness, openness, authenticity, ability to doubt and greet what comes next with questions’ (context→behaviour) in response to clients’ ‘lack of confidence in and acceptance of coach’ (context⇢attitude) as a result of ‘tension as doubt’ in clients (emotion→attitude). This dynamic is experienced as ‘critical moments’ as breakthrough moments in the coach-client relationship as reported by coaches.

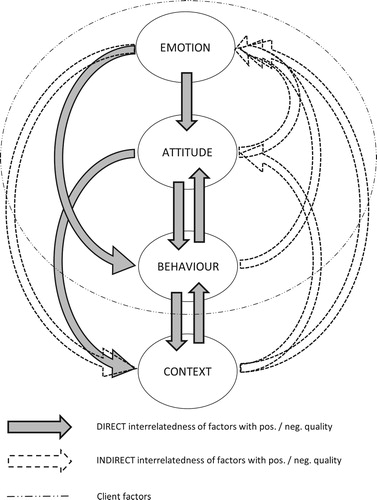

To sum up, seven (7) dimensional dynamics indicate a direct relationship while five (5) dynamics imply an indirect dimensional interrelatedness as reported in the studies (Table 5 (supplemental online material)). Most strikingly, emotion is identified as the only dimension that directly relates to the other dimensions (attitude and behaviour). Furthermore, emotion is the dimension that is only indirectly – via a third factor – influenced by the other aggregate dimensions unlike behaviour which is identified as the only dimension directly influenced by the other three dimensions. Similarly, behaviour is the only dimension that involves five direct dynamic relationships as reported in the studies. However, behaviour is not reported to directly relate to emotion. Nor is attitude reported to directly relate to emotion.

Consequently, in conducting a constant comparison of client factor dynamics across all study types and in providing a possible conceptualisation of how these four dimensions interrelate as inspired by the findings in the primary qualitative studies, we lay the foundations for building theory to encourage future research. This conceptualisation was developed through interpretive synthesis and is presented below.

Integrative relationship model

The Integrative Relationship Model (IRM) captures six (6) dimension pairs ().

Figure 4. Integrative relationship model of client factors and contextual factors.

Notes: Direct interrelatedness is implied when one factor impacts directly on the other as reported in the studies. Indirect interrelatedness is implied when one factor impacts on another factor via a third factor as reported in the studies. Positive and negative quality of interrelatedness is deducted from descriptors used in verbatim quotes. Constant comparison of direct and indirect as well as positive and negative dimensional dynamics across all study types identified how dimensions (emotion, attitude, behavior and contingencies) are embedded in coaching. A transcending non-linear process reveals patterned shifts for clients in the coaching process as observed in the domain of personality process theory but not yet fully understood and explained in coaching as a socially constructed change process. In analogy to ‘Personality Processes: Mechanisms by which Personality Traits “Get Outside the Skin”’ by S. Hampson (Citation2012), Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 315–339.

First, it highlights the core essence of emotion in coaching engagements: clients’ inner world as expressive of emotion emerges as important for them. Second, it maps how client factors potentially integrate proximal and distal contextual factors as they might affect when and how clients engage in coaching. In effect, clients are agentic learners in interaction with others rather than an isolated self from others and situations.

Consequently, IRM purports that clients’ experiences can be conceptualised from (a) a lens of dynamic interrelatedness as clients undergo their change process, and (b) a nuanced perspective of dynamic interrelatedness as they emerge in clients’ social contexts. In this model, dynamics between aggregate dimensions occur directly – one dimension affecting another dimension (see → in the model) – and also indirectly – via a third dimension (see ⇢ in the model) – where these are associated in the same coaching engagement. As such, the model does not offer new insights into intrapersonal or interpersonal dynamics. Instead, it demonstrates the prevelance of the codes that this meta-synthesis produces and offers the basis from which to draw conclusions for future empirical research on coaching effectiveness. The aim is to balance the current bias in coaching literature around the client factors and contextual factors that are studied and the ones that need to be investigated with a more process-oriented perspective both in qualitative and quantitative research. This will ultimately support coaching service providers in navigating the demands of increasingly competitive learning-based interventions in organisations (Clegg et al., Citation2005).

Discussion

As coaching research tends to revolve around measuring goal-attainment mostly the measurables seem to be in the foreground. Therefore, we have insufficient focus on the client with a specific emotionality. Additionally, given the present state of disconnected facts and experiences in the extant literature on how client factors and contextual factors interrelate in coaching we advocate that an integrative theory will progress research endeavours into the body of knowledge about how coaching works. We argue that the relative consistency of the dynamic patterns arrived at through constant comparison of qualitative text data supports the trustworthiness and dependability of emerging insights on what might be relevant dynamics to investigate in future qualitative and quantitative research. In consolidating the dispersed body of this influential area of research, this meta-synthesis makes two specific contributions:

First, this qualitative meta-synthesis indicates that emotion is a factor that is heavily under-researched and under-theorised in coaching. As the majority of the studies was identified to explore behaviour as a goal-attainment measure in this meta-synthesis, we suggest that the relevance of emotion as a key factor that affects coaching outcomes remains overshadowed. The direct interrelatedness emerging between behaviour and the other three dimensions implies that coaching research has placed the focus on measuring shifts in behaviour for goal-attainment. However, this approach harbours the risk of overlooking the other three dimensions. IRM maps that these other three dimensions might directly and indirectly influence behaviour. Specifically, findings give inspiration to propose that emotion (e.g., fear, anger, uncertainty, emotional excess) might lead to clients’ propensity for certain behaviours in specific situations, which is consistent with quantitative research findings (Mackie, Citation2015). Indeed, paying attention to emotion is necessary if we wish to deepen our understanding about the irregularities that coaches encounter when applying certain coaching methods (e.g., GROW model) that prove to be effective with certain clients while they appear ineffective with some others. Latest neuroscience research into emotion (Barrett, Citation2017) shows how little we know about coaching clients’ emotionality and how risky it is to simply guess client emotions. Barrett’s (Citation2017) breakthrough is to explain that our brain constructs an interpretation and then relates it to various past experiences and their related resource balances, which manifests in emotion types such as anger, fear and sadness. These emotions convey the meaning of the experience to clients. Hence, our call is to explore emotion both in qualitative and quantitative research on coaching effectiveness as it appears to influence behaviour (e.g., fear or uncertainty leading to resistance and lack of engagement). Inevitably, investigating emotion in quantitative research implies methodological challenges researchers encounter in their meaning making of outcomes as coaching constantly seeks to strike a balance between looking at the ‘whole person’ (Taylor, Citation1998) and looking at one isolated facet of that person (i.e., professional role or behaviour).

Second, while the body of knowledge comprising client factors and contextual factors is evolving, a theoretically informed interpretation of a perceived interrelatedness of these factors has remained unaddressed to move research on coaching effectiveness towards a consolidated evidence base (e.g., Athanasopoulou & Dopson, Citation2018). In response to the paucity of conceptual propositions (Grant, Citation2017) for future research, this meta-synthesis produces IRM that maps the way in which client factors and contextual factors are interpreted to dynamically interrelate in coaching as a context-sensitive process. As an integrative model, IRM follows McDowall’s (Citation2017) call to go beyond taxonomy-specific assessments of behavioural change to deepen our understanding of how coaching as a context-sensitive and dynamic change intervention can aid clients’ development as a meaning-making process. Indeed, research has increasingly viewed coaching as an input-output practice rather than a process-oriented activity (Greif, Citation2017) with coaches delivering coaching and clients being the recipients of coaching. While such an input-output approach to coaching research has considerably enhanced our understanding of coaching effectiveness, it ignores the possibility of coaching being socially constructed. Coaching practice tends to remain decontextualised (Cavanagh, Citation2013). Yet, any investigation into coaching is necessarily incomplete unless both client factors and contextual factors are considered to account for the dynamically patterned context-sensitive nature of coaching. Findings in this meta-synthesis (e.g., Ben-Hador, Citation2016; Nanduri, Citation2018) challenge propositions (Bachkirova, Sibley, et al., Citation2015) that the context in which coaching takes place does not account for major influences on coaching outcomes. While and where coaches as clients’ proximal context are skilled and might display attitudes that cannot be identified as impacting the coaching process, some studies suggest that coaches’ emotions and behaviours are possibly affecting clients’ change processes, both in a positive and negative way (e.g., De Haan & Nieß, Citation2015; Ianiro & Kauffeld, Citation2014). Thus, we argue that coaches need to develop a quality of mind that can grasp the interplay between other, society, and self if we were to progress the body of knowledge in coaching as a context-sensitive area of human relations. We believe that this can be achieved through a capabilities-based approach rather than a competencies-based framework when training and assessing coaches and coaching effectiveness (Bachkirova & Lawton Smith, Citation2015).

Conclusively, this meta-synthesis supports calls (Terblanche, Citation2014) for applying the relatively novel methodology of Social Network Analysis (SNA) to investigate coaching based on the interactional perspective offered in IRM. IRM argues that interpretations of a possible underlying interrelatedness through which qualitative researchers found client factors and contextual factors to explain when and how clients might engage in coaching serve as conceptual resource (Bachkirova, Arthur, et al., Citation2015) to scholars in coaching psychology wishing to measure how these factors translate into coaching effectiveness in an integrative manner.

Conclusion

In systematically synthesising 110 primary qualitative studies, we find that clients’ ‘inner world’ – that is their emotions – is rarely the subject of coaching research. Yet, the coding results seem to show that emotions count as in conversations clients’ inner world emerges as important to them. We find that emotions are overlooked both in qualitative and quantitative coaching research. Most scientists investigate some cognitive types such as trust, self-efficacy or commitment but hardly anyone explores how emotions play out in the coaching process when investigating effectiveness in coaching. We do not mean to indicate that intrapersonal processes are a new insight. Instead, in reporting about the prevalence of the codes in this meta-synthesis, we argue that a lot can be further explored in terms of intrapersonal dynamics in coaching through qualitative and quantitative research. Therefore, we argue for an understanding of coaching as clients’ dynamic change process. On the one hand, we propose that in order to discover, examine and understand clients’ nuanced behaviours, we ought to focus on both clients’ self and their social world as they interrelate in coaching. Without this awareness of totality, we cannot claim to fully understand coaching. We advocate that the interrelatedness of client factors and contextual factors as introduced in the Integrative Relationship Model (IRM) form the linchpin of future quantitative approaches to coaching outcome research (Sheldon et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, we argue that IRM indicates a shift from coaching as merely a linear input-output practice for enhancing performance towards adopting dynamic system perspectives in social psychology that reflect the multi-faceted nature of coaching practice and research (Cavanagh, Citation2013). Without adopting the patterned dynamics that represent the integrative nature of coaching, we might remain deprived of exploring a key educational opportunity for addressing the responsibility of coaches as enablers of meaning-making (Drake, Citation2015) beyond goal-attainment.

Limitations

This qualitative meta-synthesis reflects efforts to provide a reproducible systematic synthesis with minimal researcher bias. Yet, it has three discernible limitations. First, although we provide a comprehensive overview of how client factors and contextual factors dynamically interrelate to further our understanding of underlying mechanisms, we recognise that the dimensions mapped in IRM cannot be viewed as entirely conclusive. We have no results that validate or contradict our model. Second, the relevance of the interrelatedness of client factors and contextual factors as instrumental processes cannot be ascertained given the lack of statistical value of the dimensional relationships identified through interpretive synthesis. Third, despite endeavours to include all coaching-specific and coaching-relevant articles, we acknowledge that the decision to exclude keywords such as ‘sports’ and ‘clinical’ from electronic searches may have caused the unintentional exclusion of some papers from this synthesis.

Methodology Exhaustive_Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.6 KB)Supplemental_Figure 3

Download PDF (149.5 KB)Supplemental_Table 5

Download PDF (37.3 KB)Supplemental_Table 3

Download PDF (182.5 KB)Supplemental_Table 2

Download PDF (233.5 KB)Supplemental_Table 1

Download PDF (35.3 KB)Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Tünde Erdös at [email protected], upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tünde Erdös

Tünde Erdös – MSc. in Executive Coaching, ICF MCC, EMCC Senior Practitioner, PhD(c). For 15+ years now, I have been working as an external executive coach for middle management and executive positions. Currently, I am writing up my PhD dissertation on coaching presence. The research project that was awarded a Harvard Grant with Institute of Coaching, McLean’s Hospital, a Harvard Medical School Associate for its innovative research design using artificial intelligence and human interactions to measure outcomes. The project was also accredited by ICF (International Coaching Federation). Coaching is leadership and leadership is coaching. Doing scholarly work is about joining the global thinking regarding the future of best practice in coaching leadership and leadership coaching both as a business and a profession. The inspiration of doing research is to encourage coaches and leadership to base their practice harmoniously on professional wisdom and empirical evidence. I trust that research will enhance our understanding of what works for coaches, coaching clients and leadership and will thus inform our practice in the service of whoever we are called to serve. Recently, I have been elected Director of Professional Development, Research and Ethics at ICF Chapter Austria and have become Ambassador for Global ICF Coaching Science Community of Practice to foster the applicability of science in coaching and leadership. Today, there are two books in line for publication: one by McGraw Hill Publishing on Non-verbal synchrony and self-regulation in goal attainment, and the other coming out as a Coaching Science Practitioner Handbook, a compilation of transformational story telling provided by research participants. It targets coaches, career development and HR. www.ptc-coaching.com; www.coachingpresenceresearch.com.

Erik de Haan

Erik de Haan is the Director of Ashridge’s Centre for Coaching with over twenty years of experience in organisational and personal development. He aims to support individuals in their search for what is right and just for themselves and for others in their organisations. His expertise covers process consulting for organisational change, facilitating management teams, working conferences, executive and team coaching. Erik has an MSc in Theoretical Physics and gained his PhD with his research into learning and decision-making processes in perception (Psychophysics, University of Utrecht). He is a British Psychoanalytic Council registered psychodynamic psychotherapist with an MA in psychotherapy from the Tavistock Clinic, has co-authored more than 150 articles and 10 books, and sits on the editorial board of three journals including the Consulting Psychology Journal. Erik has worked with universities, hospitals and multinational companies. He is currently Professor of Organisation Development at the VU University Amsterdam. Erik is an Ashridge accredited coach and supervisor and is qualified to deliver a range of psychometric instruments. http://erikdehaan.com.

Stefan Heusinkveld

Stefan Heusinkveld is an Associate Professor at the Department of Management and Organization of the VU University Amsterdam. He obtained a PhD from the Radboud University Nijmegen with a dissertation on transience and persistence in management thinking. After his PhD he visited Durham University, the Stockholm School of Economics and Cardiff Business School. His current research concentrates on the production and consumption of management ideas with a special interest in studying the role of professions and occupations, management consultancies, management gurus, and the business media. He has published on these topics in journals such as Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, British Journal of Management, Human Relations, Information & Management, International Journal of Management Reviews, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of Professions and Organization, Management Learning, Organization Studies, Quality & Quantity, Scandinavian Journal of Management, and Technovation. He serves on the editorial boards of Organization, Organization Studies and Journal of Professions and Organization. Stefan's work has also been published by Routlegde, Oxford University Press, and Cambridge University Press (forthcoming). His recent book De Managementideeënfabriek was nominated by the Ooa as book of the year 2018. Stefan is one of the lead coordinators of the EGOS standing Working Group on ‘Management, occupations and professions in social context’. https://research.vu.nl/en/persons/stefan-heusinkveld.

References

- *Alvey, S., & Barclay, K. (2007). The characteristics of dyadic trust in executive coaching. Journal of Leadership Studies, 1(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.20004

- Athanasopoulou, A., & Dopson, S. (2018). A systematic review of executive coaching outcomes: Is it the journey or the destination that matters the most? The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.11.004.

- Bachkirova, T. (2017). Developing a knowledge base of coaching: Questions to explore. In T. Bachkirova, G. Spence, & D. Drake (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of coaching (pp. 23–41). Sage.

- Bachkirova, T., Arthur, L., & Reading, E. (2015). Evaluating a coaching and mentoring programme: Challenges and solutions. International Coaching Psychology Review, 10(2), 175–189.

- Bachkirova, T., & Lawton Smith, C. (2015). From competencies to capabilities in the assessment and accreditation of coaches. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 13(2), 123–140.

- Bachkirova, T., Sibley, J., & Myers, A. C. (2015). Developing and applying a new instrument for microanalysis of the coaching process: The coaching process Q-set. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 26(4), 431–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21215

- Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life the brain. New York, NY: Houghton-Mifflin-Harcourt.

- Barry, C. A., Britten, N., Barber, N., Bradley, C., & Stevenson, F. (1999). Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 9(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973299129121677

- *Ben-Hador, B. (2016). Coaching executives as tacit performance evaluation: A multiple case study. Journal of Management Development, 35(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-08-2014-0091

- Bozer, G., & Jones, R. J. (2018). Understanding the factors that determine workplace coaching effectiveness: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(3), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1446946

- *Bush, M. W. (2005). Client perceptions of effectiveness in executive coaching. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 66(4-A), 1417.

- Cavanagh, M. J. (2013). The coaching engagement in the twenty-first century: New paradigms for complex times. In S. David, D. Clutterbuck, & D. Megginson (Eds.), Beyond goals: Effective strategies in coaching and mentoring (pp. 151–183). Gower.

- *Cavicchia, S. (2010). Shame in the coaching relationship: Reflections on organisational vulnerability. Journal of Management Development, 29(10), 877–890. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011084204

- Clegg, S. R., Rhodes, C., Kornberger, M., & Stilin, R. (2005). Business coaching: Challenges for an emerging industry. Industrial and Commercial Training, 37(5), 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197850510609630

- Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.2307%2F4131471

- Cox, E., Bachkirova, T., & Clutterbuck, D. (2014). Theoretical traditions and coaching genres: Mapping the territory. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 16(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422313520472

- *Day, A. (2010). Coaching at relational depth: A case study. Journal of Management Development, 29(10), 864–876.

- De Haan, E. (2008). Relational coaching: Journeys towards mastering one-to-one learning. Wiley.

- de Haan, E. (2019). A systematic review of qualitative studies in workplace and executive coaching: The emergence of a body of research. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 71(4), 227–248. http://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000144

- De Haan, E., & Duckworth, A. (2012). Signalling a new trend in executive coaching outcome research. International Coaching Psychology Review, 8(1), 6–19.

- *De Haan, E., & Nieß, C. (2015). Differences between critical moments for clients, coaches, and sponsors of coaching. International Coaching Psychology Review, 10(1), 56–61.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Booth, A., & Sutton, A. J. (2007). Synthesizing qualitative research: A review of published reports. Qualitative Research, 7, 375–422.

- Drake, D. B. (2015). Narrative coaching: Bringing our new stories to life. CNC Press.

- Ely, K., Boyce, L. A., Nelson, J. K., Zaccaro, S. J., Hernez-Broome, G., & Whyman, W. (2010). Evaluating leadership coaching: A review and integrated framework. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.06.003

- Finfgeld, D. L. (2003). Metasynthesis: The state of the art—so far. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 893–904. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303253462

- Gephart, R. P. (2004). From the editors: Qualitative research and the Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2004.14438580

- Grant, A. M. (2011). Workplace, executive and life coaching: An annotated bibliography from the behavioural science and business literature. Coaching Psychology Unit, University of Sydney.

- Grant, A. M. (2017). Coaching as evidence-based practice: The view through a multiple- perspective model of coaching research. In T. Bachkirova, G. Spence, & D. Drake (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of coaching (pp. 62–84). Sage.

- Gregory, J. B., Levy, P. E., & Jeffers, M. (2008). Development of a model of the feedback process within executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 60(1), 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.60.1.42

- Greif, S. (2017). Researching outcomes of coaching. In T. Bachkirova, G. Spence, & D. Drake (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of coaching (pp. 569–588). Sage.

- *Gyllensten, K., & Palmer, S. (2007). The coaching relationship: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2(2), 168–177.

- Hampson, S. (2012). Personality processes: Mechanisms by which personality traits “get outside the skin”. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 315–339. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100419

- Hoon, C. (2013). Meta-synthesis of qualitative case studies: An approach of theory building. Organizational Research Methods, 16(4), 522–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428113484969

- *Huggler, L. A. A. (2007). CEOs on the couch: Building the therapeutic coaching alliance in psychoanalytically informed executive coaching. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 68(3B), 1971.

- *Hurd, J. J. (2009). Development coaching: Helping scientific and technical professionals make the leap into leadership. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 28(5), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.20277

- *Ianiro, P. M., & Kauffeld, S. (2014). Take care what you bring with you: How coaches mood and interpersonal behavior affect coaching success. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 66(3), 231–257. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000012

- Jones, R. J., Woods, S., & Guillaume, Y. R. F. (2016). The effectiveness of workplace coaching: A meta-analysis of learning and performance outcomes from coaching. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(2), 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12119

- *Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2013). Coaching’s ‘good jour’: Creating tipping points. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 6(2), 152–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2013.806944

- *Kiel, F., Rimmer, E., Wiliams, K., & Doyle, M. (1996). Coaching at the top. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 48(2), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/1061-4087.48.2.67

- Kinn, L. G., Holgersen, H., & Ekeland, T. (2013). Metasynthesis and bricolage: An artistic exercise of creating a collage of meaning. Qualitative Health Research, 23(9), 1285–1292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313502127

- Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Methasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00269

- Lawrence, P. (2017). Managerial coaching – A literature review. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 15(2), 43–69. https://doi.org/10.24384/000250

- Mackie, D. (2015). The effects of coachee readiness and core self-evaluations on leadership coaching outcomes: A controlled trial. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 8(2), 120–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2015.1019532

- *Mansi, A. (2007). Executive coaching and psychometrics: A case study evaluating the use of the Hogan personality inventory (HPI) and the Hogan development survey (HDS) in senior management coaching. The Coaching Psychologist, 3(2), 53–58.

- McDowall, A. (2017). The use of psychological assessments in coaching and coaching research. In T. Bachkirova, G. Spence, & D. Drake (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of coaching (pp. 627–643). Sage.

- McKenna, D. D., & Davis, S. L. (2009). Hidden in plain sight: The active ingredients of executive coaching. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2(3), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2009.01143.x

- Myers, A. (2017). Researching the coaching process. In T. Bachkirova, G. Spence, & D. Drake (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of coaching (pp. 589–609). Sage.

- *Nanduri, V. (2018). How the participants experienced a coaching intervention conducted during company restructure and retrenchment: A qualitative research study using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 11(2), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2017.1351459

- National CASP Collaboration, Milton Keynes Primary Care Trust. (2006). 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research, critical appraisal skills program (CASP) (The Cochrane Collaboration). http://www.joannabriggs.eduau/cqrmg/role.html

- *Noon, R. (2018). Presence in executive coaching conversations – The C-2 model. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring. Special Issue, 12, 4–20. https://doi.org/10.24384/000533.

- Page, D. (2008). Systematic literature searching and the bibliographic database haystack. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(2), 171–180.

- Palmer, S., & McDowall, A. (Eds.). (2010). The coaching relationship: Putting people first. Routledge.

- Passmore, J. (2007). An integrative model for executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 59(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.59.1.68

- Paterson, B. L., Thorne, S. E., Canam, C., & Jillings, C. (2001). Meta-study of qualitative health research. A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis (p. 111). Sage.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- *Peel, D. (2008). What factors affect coaching and mentoring in small and medium sized enterprises. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 6(2), 27–44.

- Peterson, D. B., & Millier, J. (2005). The alchemy of coaching: “You’re good, Jennifer, but you could be really good.” Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(1), 14–40.

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. Sage.

- References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-synthesis.

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer.

- Sheldon, K. M., Jose, P. E., Kashdan, T. B., & Jarden, A. (2015). Personality, effective goal striving, and enhanced well-being: Comparing 10 candidate personality strengths. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(4), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215573211

- Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2018). How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- Sonesh, S. C., Coultas, C. W., Marlow, S. L., Lacerenza, C. N., Reyes, D., & Salas, E. (2015). Coaching in the wild: Identifying factors that lead to success. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 67(3), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000042

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage.

- Taylor, E. W. (1998). Transformative learning: A critical review (Information Series No. 374). ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, The Ohio State University.

- Terblanche, N. (2014). Knowledge sharing in the organizational context: Using social network analysis as a coaching tool. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 12(2), 146–167.

- Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta- analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.837499

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the systematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(181), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181.

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

- *Wales, S. (2003). Why coaching? Journal of Change Management, 3(3), 275–282.

- Western, S. (2012). Coaching and mentoring: A critical text. Sage.

- Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage.