ABSTRACT

Shared Decision-Making (SDM) is one of the key components of patient-centred care. People diagnosed with schizophrenia/psychosis still face significant barriers to achieving this, particularly when it comes to antipsychotic medication prescribing. These barriers include issues such as stigma, feelings of coercion and lack of information. Clinicians also describe barriers to achieving SDM in antipsychotic prescribing, including a lack of training and support. In this viewpoint article, we provide a summary of these barriers from the perspectives of both service users and clinicians based. We suggest that, to make a practical first step towards achieving SDM, the conversation around antipsychotic prescribing needs to be re-started. However, the onus to do this should not be placed solely on the shoulders of Service Users. More research is needed to address this issue.

The majority of people diagnosed with schizophrenia and/or psychosis are prescribed long-term antipsychotic medication (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2014). Antipsychotic medication has been shown to prevent relapse (Leucht et al., Citation2009). However, recent research suggests that taking antipsychotic medication long term may not be the best option for some people (Morrison et al., Citation2012; Murray et al., Citation2016).

Despite its widespread use, antipsychotic medication is associated with a range of severe adverse side effects (Foley & Morley, Citation2011; Husa et al., Citation2014; National Institute of Mental Health [NIHM], Citation2016; Ray et al., Citation2009). People taking antipsychotic medication have been found to have an increased risk of early mortality (Weinmann et al., Citation2009). A recent survey found that 57.5% of people taking antipsychotics had purely negative experiences (Read & Sacia, Citation2020). Despite the potential for adverse effects, Service Users (SU) taking antipsychotic medication has often reported a lack of choice in whether to take them or not (Bülow et al., Citation2016). Reasons for this include feelings of coercion and lack of information and support. Clinicians may still view taking antipsychotics as a “moral responsibility and refusal as foolish” (Moncrieff et al., Citation2020, p. 5).

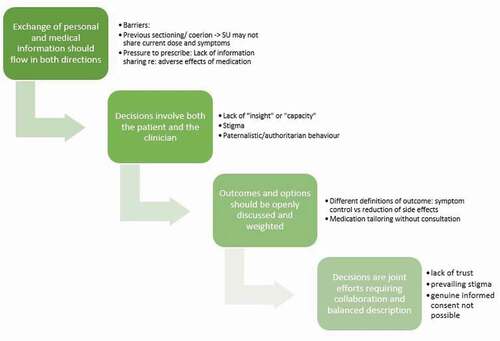

In recent decades, there has been a shift towards patient-centred care. A major element of the philosophy of patient-centred care is to support SU in developing and enacting agency and autonomy in their care. This is achieved, in part, through Shared Decision-Making (SDM). Charles et al. (Citation1999) developed four domains needed for SDM to be achieved. They are:

Exchange of personal and medical information should flow in both directions

Decisions involve both the patient and the clinician

Outcomes and options should be openly discussed and weighted

Decisions are joint efforts requiring collaboration and balanced description

In practice though, particularly for people diagnosed with Schizophrenia/Psychosis, SDM is not easily achieved. Here, we intend to highlight barriers to achieving each of the domains, unique to antipsychotic prescribing, therefore warranting special attention ().

Figure 1. Stages of SDM and their barriers, modified from Charles et al. (Citation1999)

Exchange of personal and medical information should flow in both directions

In any appointment it is crucial that both SU and clinician have all the relevant information available to be able to make informed decisions. There are however barriers from both sides that may prevent this.

SUs tailor their medication to meet their needs without consulting their clinical teams (Bülow et al., Citation2016; LeGeyt et al., Citation2017). These practices can be a result of previous experiences of coercion and subsequent lack of trust in the clinical team. The lack of trust created by previous experiences of coercion or sectioning under the Mental Health Act may also prevent SU from sharing whether they are currently experiencing symptoms.

Clinicians may also not be able to share information. Guidance is lacking on how to antipsychotic medication making open discussion challenging. Additionally, clinicians may feel pressure to ensure medication adherence, leading to a reluctance to share information regarding potential adverse effects. Clinicians may worry about SU refusing or stopping medication they were given all the information. Therefore, they may not disclose all of the information necessary to achieve true informed consent from SUs (Maidment et al., Citation2011).

(2) Decisions involve both the patient and the clinician

SUs are often still not accepted as experts by experience. Therefore, paternalistic, benevolent and authoritarian behaviour may prevail, leaving the clinician in the position of decision maker.

Some clinicians still feel that SUs may not be able to participate in a discussion, as they lack “insight”. Clinicians have even described them as “untrustworthy” (Grim et al., Citation2016). This may occur despite stability in the SU’s condition. SUs have also reported that clinicians address family members, friends or key workers, rather than themselves, leading them to feel “stupid or irrational” (Lester et al., Citation2003, p. 511). This can make participation in decision-making impossible for the SU.

Added to this is continued stigma towards SUs requiring antipsychotic medication. Medication use confirms the status of the service user as “mad” or “weird” (Thompson et al., Citation2020). Some studies even report clinicians being frightened of people with these diagnoses, preventing effective communication (Burton et al., Citation2015) and appropriate care (McDonell et al., Citation2011).

As a result of this stigma, SUs report that they are not listened to and that clinicians make assumptions about their capabilities to understand their treatment options and be included in conversations and decisions about their own care (Lester et al., Citation2003).

(3) Outcomes and options should be openly discussed and weighted

Clinicians and SUs do not always share the same opinion about the aims of a particular treatment plan.

Studies have illustrated that clinicians often prioritise symptom reduction. However, other research shows that SUs prioritise lower doses of antipsychotic medication, facilitating a reduction in side effects to improve overall Quality of Life. This misalignment of goals can be problematic and prevent SDM from occurring.

If outcomes and options are not discussed and aligned this can have consequences moving forward. SUs may choose not to adhere to treatment plans, which can lead to unsafe medication practices, putting their health at risk.

(4) Decisions are joint efforts requiring collaboration and balanced description

Considering all barriers outlined above, it is clear to see that collaboration and a balanced description may not be achievable. It is difficult to achieve genuine informed consent if open discussions are not possible. As we have seen, this is due in part to a lack of trust and prevailing stigma in the area of antipsychotic prescribing for people diagnosed with schizophrenia and/or psychosis. It is clearly evident that there are significant hurdles to achieving genuine SDM for this population.

SDM during the pandemic

It is especially important to consider these issues during the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic. This sudden change in how medical treatment is to be provided has been challenging for both SUs and clinicians. It has caused a decrease in face-to-face visits and places this already marginalised group at risk of further disadvantage when it comes to medication management (Luykx et al., Citation2020). The Royal College of Psychiatrists states that “for many patients it is likely that advice will be given to continue on regular medication until this can be reviewed in a face to face setting and the patient can be involved in Shared Decision Making” (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2021). This is potentially continuing paternalistic practices and hindering SDM.

Restart conversations – a way forward

Health services have prioritised patient centred care and SDM, however SUs may not be aware of these changes. For change to occur, the conversation surrounding antipsychotic prescribing needs to be re-started. It appears that there is a lack of agreement on who should start this conversation, especially in primary care.: Clinicians have expressed that patients should be “doing their part”, “speaking up” and “keep clinicians well informed” (Mikesell et al., Citation2016). However, as outlined above, previous experience of coercion and lack of trust may prevent this. Consequently, the onus to start these conversations should not be placed on the shoulders of SUs. So it falls to clinicians to re-start the conversation about antipsychotic medication prescribing. They should provide SUs with the space and time to openly and honestly discuss their antipsychotic medications without fear of being penalised or coerced. Information regarding possible side effects may need to be explained multiple times, potentially as part of a structured assessment (Kendrick et al., Citation1995). This should occur alongside assurances that many people tailor their medication and that disclosure of their actual dose (vs their prescribed dose) is important to enable safer prescribing.

Input from SU and clinicians is needed to further understand how these conversations may be restarted once face to face consultation resumes following the pandemic. This would allow improved information sharing, continuing on the path towards genuine informed consent. This is a step towards enabling service users to enact the agency that is promoted through the provision of patient-centred care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bülow, P., Andersson, G., Denhov, A., & Topor, A. (2016). Experience of psychotropic medication –An interview study of persons with psychosis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(11), 820–828. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1224283

- Burton, A., Osborn, D., Atkins, L., Michie, S., Gray, B., Stevenson, F., Walters, K., & Gilbert, H. (2015). Lowering cardiovascular disease risk for people with severe mental illnesses in primary care: A focus group study. PLoS ONE, 10(8), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136603

- Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1999). Decision making in the physician-patient encounter: Revisiting the shared treatment decisionmaking model. Social Science & Medicine, 49(5), 651–661. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315013015-30

- Foley, D. L., & Morley, K. I. (2011). Systematic review of early cardiometabolic outcomes of the first treated episode of psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(6), 609–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2

- Grim, K., Rosenberg, D., Svedberg, P., & Schön, U. K. (2016). Shared decision-making in mental health care-a user perspective on decisional needs in community-based services. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.30563

- Husa, A. P., Rannikko, I., Moilanen, J., Haapea, M., Murray, G. K., Barnett, J., Jones, P. B., Isohanni, M., Koponen, H., Miettunen, J., & Jääskeläinen, E. (2014). Lifetime use of antipsychotic medication and its relation to change of verbal learning and memory in midlife schizophrenia - An observational 9-year follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research, 158(1–3), 134–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.035

- Kendrick, T., Burns, T., & Freeling, P. (1995). Randomised controlled trial of teaching general practitioners to carry out structured assessments of their long term mentally ill patients. Bmj, 311(6997), 93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.6997.93

- LeGeyt, G., Awenat, Y., Tai, S., & Haddock, G. (2017). Personal accounts of discontinuing neuroleptic medication for psychosis. Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316634047

- Lester, H., Tritter, J. Q., & England, E. (2003). Satisfaction with primary care: The perspectives of people with schizophrenia. Family Practice, 20(5), 508–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmg502

- Leucht, S., Arbter, D., Engel, R. R., Kissling, W., & Davis, J. M. (2009). How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Molecular Psychiatry, 14(4), 429–447. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4002136

- Luykx, J. J., Van Veen, S. M. P., Risselada, A., Naarding, P., Tijdink, J. K., & Vinkers, C. H. (2020). Safe and informed prescribing of psychotropic medication during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(3), 471–474. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.92

- Maidment, I. D., Brown, P., & Calnan, M. (2011). An exploratory study of the role of trust in medication management within mental health services. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 33(4), 614–620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-011-9510-5

- McDonell, M. G., Kaufman, E. A., Srebnik, D. S., Ciechanowski, P. S., & Ries, R. K. (2011). Barriers to metabolic care for adults with serious mental illness: Provider perspectives. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 41(4), 379–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.41.4.g

- Mikesell, L., Bromley, E., Young, A. S., Vona, P., & Zima, B. (2016). Integrating client and clinician perspectives on psychotropic medication decisions: Developing a communication-centered epistemic model of shared decision making for mental health contexts. Health Communication, 31(6), 707–717. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.993296

- Moncrieff, J., Gupta, S., & Horowitz, M. A. (2020). Barriers to stopping neuroleptic (antipsychotic) treatment in people with schizophrenia, psychosis or bipolar disorder. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 10, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125320937910

- Morrison, A. P., Hutton, P., Shiers, D., & Turkington, D. (2012). Antipsychotics: Is it time to introduce patient choice? British Journal of Psychiatry, 201(2), 83–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112110

- Murray, R. M., Quattrone, D., Natesan, S., Van Os, J., Nordentoft, M., Howes, O., Di Forti, M., & Taylor, D. (2016). Should psychiatrists be more cautious about the long-term prophylactic use of antipsychotics. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(5), 361–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116182683

- National Institute of Mental Health [NIHM]. (2016). Mental health medications. National Institute of mental health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications/index.shtml

- Ray, W. A., Chung, C. P., Murray, K. T., Hall, K., & Stein, C. M. (2009). Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(20), 2137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sa.0000360612.83083.3e

- Read, J., & Sacia, A. (2020). Using open questions to understand 650 people’s experiences with antipsychotic drugs. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(4), 896–904. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa002

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2014). Report of the second round of the national audit of schizophrenia (NAS2) 2014. Royal College of Psychiatrists. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/FINALreportforthesecondroundoftheNationalAuditofSchizophrenia-8.10.14v2.pdf

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2021). COVID-19: Providing medication. Royal College of Psychiatrists. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/about-us/responding-to-covid-19/responding-to-covid-19-guidance-for-clinicians/community-and-inpatient-services/providing-medication

- Thompson, J., Stansfeld, J. L., Cooper, R. E., Morant, N., Crellin, N. E., & Moncrieff, J. (2020). Experiences of taking neuroleptic medication and impacts on symptoms, sense of self and agency: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative data. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01819-2

- Weinmann, S., Read, J., & Aderhold, V. (2009). Influence of antipsychotics on mortality in schizophrenia: Systematic review. Schizophrenia Research, 113(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.018