ABSTRACT

Background

A co-design project, consisting of individual and collective design activities, was organized with clients of a mental health service, in order to explore its potential to support people with psychosis. The group met for approximately two hours, weekly, for six months, participating in design activities and collectively deciding on the project purpose and outcome – a boardgame.

Methods

The experience of one group participant (Anthony) is explored, selected as the first case study within an Interpretative Phenomenological Analytical (IPA) framework. Following IPA’s ideographic focus, Anthony’s case was purposefully selected, as it portrayed a detailed picture, informing theoretical reflection on designing as therapeutic. The paper includes Anthony’s first-hand account, combined with an analysis of data from three semi-structured interviews, photographic evidence and a reflective diary kept by the lead researcher.

Results

Results suggest that, for Anthony, design activity: a) helps developing a sense of agency b) is experienced as grounding in reality c) contributes to the development of inter-personal relationships, and d) has a different sense of rhythm than artistic practice.

Discussion

These results are contextualized within literature on the lived experience of psychosis and suggest that designing can be beneficial for people with psychosis, providing the backdrop for further research and practice.

Introduction

This paper explores how designing may be therapeutic for people facing mental health problems. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as art or occupational therapies, are well known, however design-oriented approaches are scarce (Blake et al., Citation2016; Glazzard et al., Citation2015; Kaasgaard & Lauritsen, Citation1997; Kettley et al., Citation2016; Mužina, Citation2020; Nakarada-Kordic et al., Citation2017; Wadley et al., Citation2013). For instance, Kettley et al. (Citation2016) developed an e-textiles co-design project informed by the Person-Centred Approach mode of psychotherapy, and Nakarada-Kordic et al. (Citation2017) developed methods to engage young people with psychosis in the process of co-designing an app to support their education and wellbeing. Within these projects, the mental health benefit is associated with the use of the design outcomes -products or services resulting from the project- rather than with the participation in the design process itself.

Design is customarily understood as a type of creative practice which, in contrast to problem-solving, involves defining or framing a problem in tandem with the solution (Dorst & Cross, Citation2001). It is defined as an open-ended, meaning making, or reflective activity that leads to the creation of something in the world (Schön, Citation1983). Despite a fast-growing interest in using design in the context of health and wellbeing (see, Petermans & Cain, Citation2020) and within mental health (e.g Amiri, Wagenfeld & Reynolds, Citation2017; Cooper et al., Citation2016; Craig, Citation2017; Larkin et al., Citation2015; Mulvale et al., Citation2016; Ospina-Pinillos et al., Citation2019; Tsekleves, Citation2020; Warwick et al., Citation2018), the potential of design activity per se to support mental health remains unexplored.

Two significant developments within mental health provide the contextual opportunities for this exploration. Firstly, the rise of the recovery movement, which broadly focuses on restoring functioning above and beyond symptom reduction and recognizes the ability of people with mental health problems to participate in society (Davidson, Citation2016). Secondly, the development of person-centered care, which focuses on an individual’s unique goals and life circumstances (Dixon et al., Citation2016), acknowledging experiential knowledge.

This paper focusses on co-design in specific: a practice where people collaborate or connect their knowledge, skills and resources in order to carry out a design task (authors, 2018). Co-designers work alongside users or stakeholders to develop ideas, products or services in a relationship which acknowledges participants as experts by experience (See, Sanders, Citation2000). From this standpoint the study sought to explore how co-design is experienced and may help the participants’ recovery.

A project was organized in collaboration with mental health charities Islington Mind and Psychosis Therapy Project, recruiting clients attending their Psychosis service. The paper focuses on Anthony’s case, who although he did not wish to figure as a co-author, contributed his account and gave feedback on the draft.

Methods

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), is a qualitative research method used to look into how people make sense of their experiences. As Marczak and Postăvaru (2018) remark, IPA emphasizes the need to understand an individual’s lived experience through exploring their involvement in a specific event or process.

As (Smith et al., Citation2009) describe, ideography, one of IPAs tenets, is an argument for a focus on the particular, which leads to a re-evaluation of the importance of the single case study. A case study can provide significant detailed insights about a particular person and their response to a situation (Smith et al., Citation2009). As there are no earlier studies of design as a therapeutic activity, focusing on Anthony’s case helps inform an initial conceptual frame, paving the ground for other analyses.

The project received ethics approval by The Open University Human Research and Ethics Comittee (Ref. 3050) Upon reading the information sheet about the project, Anthony gave written consent, specifying that he did not want to remain anonymous.

Reflexivity

The lead author facilitated the project, and was responsible for data analysis, so it should be acknowledged that to a certain extent, the transmission of assumptions, values, interest and emotions within the research project are inevitable (Starks & Brown Trinidad, Citation2007). Notwithstanding, during the project, effort was placed to temporarily suspend previously developed theories.

The lead author has a background in Industrial Design, is Mental Health First Aid trained and has experience working within mental health and prisons. Author has an expertise in psychotherapy. Authors have studied the neuroscience of designing, and worked in co-design extensively.

Case study design

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, one immediately after completing the project, and another two approximately 4 months later. Additionally, photographs were taken and a reflective diary was kept throughout the process.

In the first interview, the focus was on a set of open questions [See, ]. The subsequent interviews were more conversational, with the participant and researcher discussing fragments from the initial interview. Quotes from Anthony’s interviews are referred as 1st interview (22.07.19), 2nd interview (20.11.19) and 3rd interview (04.12.19) to provide transparency as to how far in the interpretative thread a statement was made. Benefits and challenges of multiple interviews in IPA are described by Flowers (Citation2008).

Table 1. The open questions used in the interviews with Anthony.

Anthony

Anthony self-identifies as white, second generation London-Irish man. He is 56 years old, and reports being in the mental health system since 1998, including seven hospitalizations. He received different diagnoses over the years: stress, anxiety, paranoia, acute paranoid state, paranoid psychosis and paranoid schizophrenia. In the past, he reports working as a fraud investigator. He is a skilled artist, he uses Irish bog oak for sculpting, he makes collages using recycled paper and plays music. Anthony has been attending the Psychosis service since 2015, and received one-to-one psychotherapy once a week in parallel to this project.

The co-design project

The project was embedded in a wider service, which provides long term one to one psychotherapy and includes a weekly drop-in in a living room area for clients to socialize. Clients could join other activities (often run by volunteers) happening in adjacent rooms, including this project, which was organized in weekly, semi-structured group sessions by the lead author alone. The study was embedded within the space, yet independent from, the aforementioned service. Anthony was one of nine participants recruited by word of mouth. In Anthony’s account below, whenever he refers to “therapists” he means those working for the service, who were not involved in this study. Anthony engaged intensely in the project, and worked at home between sessions. Other participants’ engagement varied, some attending increasingly often, others participating peripherally, and was acknowledged equally.

Participants were informed that the project aimed to understand their experiences and an outcome was not necessary.

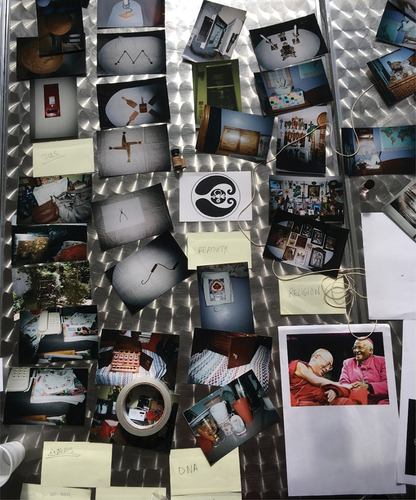

They were introduced to the design process in a flexible way, creating a shared understanding of design, and enabling them to decide the direction of the project, which was loosely organized in stages. The first aimed to help participants familiarize with each other and with design. Activities included bringing meaningful objects and discussing their design process in relation to a collective timeline; or prototyping design solutions to respond to each other’s improvised design problem. Subsequently, a version of cultural probes was used (Gaver et al., Citation1999), which Anthony called cultural specimens (). These are tools (e.g. disposable cameras) used to explore participants’ common interests, and ultimately inform a design brief, or purpose, which emerged naturally. Finally, brainstorming activities were organized to generate ideas. The final outcome was a board game (), which was showcased alongside other participants’ work in an exhibition. More information about this outcome can be found at [link]. The design process is described by Anthony in the next section (page 7).

Analysis

As discussed, this case study followed the principles of IPA. The interviews were transcribed and coded using NVivo version 11. The lead author coded the first interview, and statements which were surprising, related to theoretical ideas, or whose meaning was not clear, were highlighted for interrogation in subsequent interviews, until no further insights emerged. Anthony’s data were coded by a second author, who also conducted an independent audit, to help test the plausibility and coherence of the first author’s interpretations, following (Smith et al., Citation2009). Hence, whilst the second authors [KA] codes were descriptive, the interpretative, superordinate theme structure was created by the lead author [ERI] and then discussed with the others.

Anthony’s personal account

Anthony’s retrospective first hand account is included (unedited) below, complementing perspectives as a co-researcher.

An introductory note

The attached account was written from my memory of the events, without the use of, or my consulting any of the material from two years ago. I thought it right and correct to only mention the things which had actually remained in my memory, thus giving this account more validity.

Memories of the design project

I first met Erika at the winter party at the The Mind Hub back in 2018. Erika subsequently came back to the Hub, shortly after, when looking for people to participate in a design project. I said that I didn’t mind joining this project. I had at that time been going to the The Mind Hub for therapy since September 2015. Erika distributed some literature re. the design project and I was interviewed by her at a later stage. The form in which the project would evolve remained hazy at first. Erika probably had ideas regarding the project’s direction, but things remained fluid at the outset. The first task, at the start of the design project was to think about an object or objects which you liked and which you thought had been designed well.

I thought of various items I liked, but I eventually opted for two things – The functional design and quirky beauty of the Citroen 2CV car, and also the simplicity and practicality of small milking stools – which I collect. I also collect models of 2CV cars.

I brought various 2CV models up to the project, and a selection of some of my old milking stools. I also wrote something about why I liked these designs.

Erika sat with us all in the common room and she continued to recruit for the design project. People asked Erika what it involved, and they also looked at the objects I had brought in, as well as the material I had written about the 2CV and the milking stools. Both service users and therapists present were intrigued by this design project, but the overall concept remained somewhat elusive at the start. As the design project developed, Erika recruited more participants, and each of these brought a favourite object of theirs to the Hub, or a design concept which they liked.

Space for us was made available on tables within the dining area.

If I remember rightly, discussions took place about what design meant to each of us.

Erika brought her expertise to these situations and design processes were discussed, from need, inception, production, materials, practicality, functionality etc.

Various activities took place over the weeks and months of the project. The tables were full of card, Sellotape, scissors, string, pens, paper etc, which we used to aid our creativity in the design project and process.

We drew design timelines on sheets of paper, and on a larger wallchart as well. We thought about, sketched, planned and made objects ourselves, and after joint discussions.

We also came up with concepts, and these were then passed to others in the group, to expand upon and create or plan further with regard to the initial ideas.

In another activity, we worked with paper, folding and tearing, and passing these creations back and forward between us, in groups of two, whilst remaining silent, and without discussing what was actually being made. Objects developed and evolved and at the end we each commented on what we thought the object was.

Each week, as homework, we were asked to think about designs or elements of design, to bring to the group the following week.

Erika used certain subject matter from within our group discussions and interactions to drive the project forward into the following week.

At a certain point in the project, Erika gave us the opportunity to take cameras to photograph objects or things that we liked. We were also given small bottles and small containers to collect and bring back to the design project, small items from our environment.

When all the photographs and the “Cultural probes/specimens” were returned, they were put together in groups, to reflect common themes.

I was only present for a short time that day, as I spent time with a volunteer who was leaving the Hub, on that day. I usually came late to the design group anyway, as its start coincided with my therapy session.

The common themes amongst the participants’ photographs, probes and discussions were, if I remember correctly, such subjects as – nature, the environment, healing and spirituality.

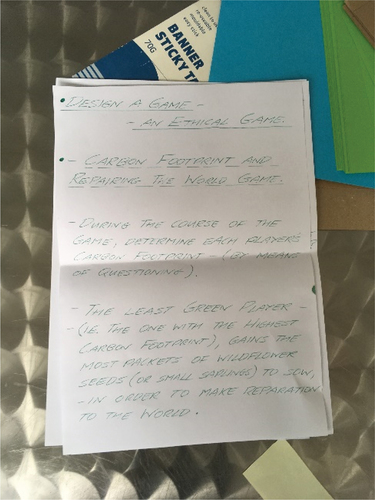

One of the participants, I was later told, suggested that it would be nice for a game to perhaps be developed out of the common themes, which has arisen out of this exercise.

Discussions on this idea, presided over by Erika, continued between all the group members and also a volunteer/therapist present.

The idea of a game was developed. A “spinner” was deciding the order of play, and a lid of a coffee or sugar container was initially appropriated for this purpose.

A set of questions, to be used in the game were formulated. The game eventually coalesced into something somewhat more solid in nature.

The rules of this group game were in flux for some while. At this stage, whilst at home, I thought up a “Green” game with environmental issues in mind. Some elements of this game were eventually incorporated into the wider group game.

Rules for this jointly designed group game were worked upon, and this eventually evolved, from the initial concept, into the end product.

Elements of all the various ideas contributed by the design group members, were encapsulated into the final outcome.

This game is and can be a means for self-betterment. This is achieved by social interaction and discussion, between the players, bringing people’s emotions, ethical standards and outlooks into play.

The game was experienced and tested out at the final exhibition, which was held on the same day as the 2019 summer party.

All participants seemed to enjoy the interactive nature of the game.

Erika’s drive, dedication and direction, together with her coordination of the whole project, was intrinsic to this memorable and enjoyable experience.

I am glad that Erika brought her co-design concept to the Hub. She allowed us all to freely express ourselves, whilst she determinedly drove the project forward week by week. Ultimately this led in fact to the solid end product of the game, although initially at the outset such an outcome was not perhaps then foreseen or envisaged.

The whole experience of Erika’s project was thoroughly enjoyable, and it was a happy and social activity.

One of the participants within the design project group has sadly since passed away. His artistry and illustrative abilities contributed significantly toward the final outcome of this project. Many of my abiding memories of him are entwined within this whole group process and endeavour.

Just to reiterate, I think that we all enjoyed participating and engaging in this innovative design project.

Benefits of the design project

Being involved in the many elements of the design project enabled me to think about objects and their design in a new way.

I put into words my feelings, reflections and observations with regard to various aspects of design. I had maybe never thought about or actually articulated these ideas before.

I got to know Erika and the other members of the group. I had perhaps never spoken in depth beforehand, on some subjects, with other members of the group. The design project and the activities it involved, allowed us all to interact together unselfconsciously.

Enjoyable conversations took place, whilst the main focus of our attention was on the design tasks and processes.

The design project got me writing again.

A creative writing group commenced at the P.T.P in the Mind Hub, during the same time that the design project was taking place. Since I had been writing pieces for the design project, I thus felt confident and able to join this new creative writing group. However, when a previous creative writing group had taken place I had not availed of that, because I was not confident enough, or in the right frame of mind back then.

The creative writing group I joined lasted for almost a year, and the facilitator encouraged me to start writing poetry, and I continue to write poetry now.

In future I will not perhaps be so hesitant in engaging in other pursuits available in the P.T.P Before lockdown, I had joined the dance movement psychotherapy group, which I enjoyed very much.

Just to conclude, the design project provided me with the opportunity to focus again, and to in fact realize that it was still within my capabilities to focus and concentrate.

The design project helped and contributed towards my well-being, thus enabling me to implement a new way forward for myself, by channelling the confidence I gained from the whole process, into a more positive outlook on life.

Anthony, 1 March 2021.

Findings

In the interviews, Anthony gave descriptions of his design experience, often contrasting it with other activities, such as collaging, carving, and creative writing. Key observations about the designing experience are grouped under four themes: experience of rhythm, sense of agency, grounding, and acceptance from others and self-worth.

Experience of rhythm across activities “[design] is fast and slow”

When Anthony was encouraged to reflect on his engagement with the activities, he described their difference by referring to concepts of rhythm. Designing was “fast and slow”, while creative writing was “fast and fast”, and carving and collage were “slow and slow”.

design is sometimes quick fire ideas [initially] but then is developed so it is fast and slow, whereas the creative writing is fast; the carving is thought about slowly and then you turn things slow (…) So creative writing is fast; this [design] is fast and slow [Anthony, 1st interview]

The experience of rhythm may be intertwined with other qualities. Fast seems to be associated with coming up with ideas without much analysis, and slow when these are more carefully developed. Designing seems to shift constantly from freely generating ideas (e.g. brainstorming) to developing them.

creative writing is very quick and it is in 2 or 3 minutes you have to write something down (…), now the design process maybe you can [be quick] if you are shouting out things, it is initial ideas and stuff and that, but [design] it’s developed. [1st interview]

These experiences were associated to feelings. Slow was associated with feeling calm, while fast was associated with being under some pressure.

[carving] is calm a lot of the time like you have to cut this bit out so it will take you 5, 10 minutes, half an hour; you have made the decision and then you’re calm for half an hour but the design process (…) is more actively involved and under a little bit of pressure, but directed focused pressure [1st interview]

Having some pressure or being busy seemed to affect the generation of what he often referred to as “funny or wild ideas”, specifying that it was a positive kind of busy.

I supposed we did design (…) you know I enjoyed being busy but it was good busy (…) I didn’t have much time to think about wild ideas (…)I can hack being busy (…) I can be busy again and not send me over the edge. [1st interview]

Finally, Anthony also reflected on the different activities in relation to time in a more literal sense.

I can be doing the green book for 18 hours 20 hours at a time(…) is slow (…) but sometimes it can be done in one sit down session. [1st interview]

I can’t go out to the shop in the middle of doing either of them [collage or carving] whereas say I am thinking about design at home or writting something at home, I can take time out and go out to the shop, come back …[1st interview]

Sense of Agency across activities “That was me, it was me that”

During the 1st interview, Anthony brought up notions relating to agency. He observed that when he is collaging, he feels directed by god:

the green [collaging] book it comes so easy to me because I have been doing it for so long. I can sit in the one spot and just reach my hands out and everything is there (…) it is directed by god and the holy spirit I can just reach out now sometimes (…) and if I have to try too hard I don’t I don’t put it in or I don’t try. So if it comes easy [it is] because that is directed and god places the appropriate words and stuff next to me [1st interview]

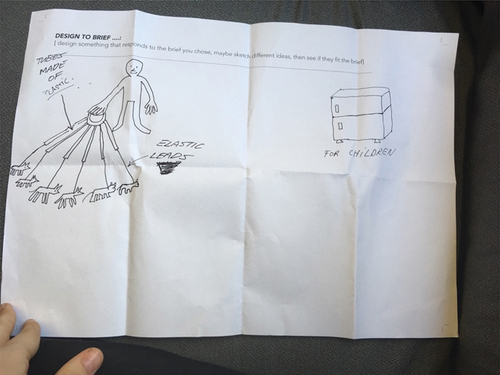

This prompted further questions about other activities, revealing possible differences in relation to agency. While his collaging is directed by god, carving seems to be shared among god and himself. When he was asked about designing, he talked about a collaboration with materials, but it remained ambiguous whether he was still referring to carving. On the 2nd interview he was shown the following extract from his 1st interview to prompt reflection on who directed design activity ():

I came out from [the therapy session] and I was trying to think about a design concept (…) I couldn’t think of anything and then [another participant] was sitting there between the two of us. I thought he walked 6 dogs so (…) let’s design a lead so he can walk them together (…) that was a little bit of pressure he was there and it came [1st interview]

Anthony responded:

That was me, it was me that, because you know like [the other participant] was between me and you and I looked at him and I couldn’t think (…) and then I just thought a walker for six dogs you know, but you remember it was little leads on the end of plastic tubes that were joined to separate them so the leads wouldn’t get twisted. But that was me in there that was me (…) [3rd interview]

It can be argued that designing contributes to an enhancement of his sense of agency. By contrast, there seems to be a barrier for collaging to be perceived this way, as the motivation diminishes when it is not directed by god:

but I am directed [in collage, by god] and is almost like if something [e.g., paper scrap] isn’t at arms reach is not meant to be [3rd interview].

It appears that when Anthony engages in artistic expression through collaging, he may be experiencing flow – conceived as being directed by an external force- without which, it is just “not meant to be”. In doing collage, when he does not feel to be directed by god, he will not continue the effort, lowering the chance for the sense of agency to form.

Considering people with psychotic symptoms can often experience a diminished sense of agency, these insights hold profound implications for designs therapeutic role.

Grounding across activities “design is more rooted in reality sort of situation”

Anthony defined design as more rooted in reality, in contrast to collage, carving or creative writing. This may reflect the context in which design takes place, as well as the way designing is driven by a purpose which is determined by the real world, or an external need. Conversely, collage, carving or creative writing often explore more personal imaginaries which Anthony calls dream world or funny ideas.

Anthony described that when he does the green book [collage] or carving he is “out of the world”.

(…) for the duration of the time that I am doing the green book [collage] I am out of the world. I am just in my own situation, which is good in one way, but bad in another. When I am doing the carving, I am even more out of the world because I am black, you know dusty (…) I remove myself from the world. With the design project I am in the world. I kind of interact with the world (…) is a more sociable thing you are not as separated when you are doing it, [it] is a more in-the-world sort of thing. But the creative writing is as well but you can go off in flights of fancy. You can with design as well, but design is rooted in the world because it is function and you know you are designing things, things, objects I suppose, whereas creative writing you can go off in flights of fancy [1st interview]

According to Anthony, design is rooted in the world because “it is function”. This idea of function seems to refer to the purpose of what is created (what the object is for), implying the world out there. An examples is shown in ().

When prompted to talk about the effects the project had on his mental health, Anthony responded that when he focuses he is less likely to experience psychotic thoughts.

when I am doing a task I am focused on that so I am less inclined to think psychotic ideas or ponder my situation and just focus on the task in hand …[1st interview]

so that by focusing in on something you are less self- … I don’t know (…) you are less full of your own psychotic ideas …[1st interview]

design is more rooted in reality sort of situation and [in] creative writing I do bring the reality into it, but I can go off in flights of fancy but and the other things [collage and carving] (…) I remove myself [from the world] (…) Three weeks of not shaving or cutting my hair or drinking alcohol you know, I was like John the Baptist by the end of it (laughs) [1st interview]

Therefore designing, due to function, may have had a grounding effect, directing Anthony’s focus of attention to the context and purpose of use, which he experienced as rooted in the world, helping him engage towards it.

Well, I suppose what happened was what happens in the real world, sort of like you get together and you voice ideas and (…) something tangible came at the end of it: the board game which is good, it is a tangible thing so it will stay around [1st interview]

Finally, when Anthony talked about “getting more well” during the project, and was asked to elaborate on that, he talked about becoming more driven:

yes yes oh yes (…) I have been well for years you know, for a good while, but I feel better in myself, more, you know, like driven [1st interview]

Designing therefore may provide some direction and focus which is rooted in the world, yet constantly engages the agent in driving action and making decisions.

Acceptance from others and self-worth “Things were not dismissed so readily”

Finally, during the design process, Anthony’s perception of being accepted seemed to have increased, feeling better because the outcomes of the design were not dismissed so readily as his other work (e.g. collage), or were incorporated into something else.

I felt good in myself, better, and just … I don’t know contributing towards something or you know just not being dismissed, like my green book is [collage]. A lot of people like my green book but they dismiss it as well as flights of fancy, or but this [design] this process you know things were not dismissed so readily (…) they were incorporated into something that we all contributed towards, so I felt better in myself …[1st interview]

Throughout the process, previous comments were integrated and informed the design direction, which according to Anthony showed that what one said had certain validity.

not much went pass you (…) you like a throw-away comment you may hear and incorporate it (…) into the following [week] … which is good, in a way it shows you what you say has a certain validity, what a person like me or the others say has a certain validity to it and it is not dismissed at hand, like my wilder ideas are dismissed at hand by the majority of the population … except those who know it to be the case (laughs) [1st interview]

Anthony also anticipated that if people saw that he was directed and sane in certain elements, they would be less likely to reject other ideas.

if you are sensible and sane and directed in certain elements in your life, then people can maybe find it hard to put you down in other elements or other parts of your life which aren’t quite as clear cut (…) So it sort of grounds my ideas so that people are less able to shoot down other ideas - I don’t know if that is a good thing or bad thing [1st interview]

and there is an actual game out there now and then that is something that you can see and touch (…) it lends credibility to the wilder things because this is something that people can’t dismiss. I am sure a lot of inventors are half mad anyhow but maybe they are not and maybe it is good mad [1st interview]

In subsequent interviews, Anthony explained that what he sought was not people changing their position, but just having some inclination, “being tilted”. What Anthony may be referring to is an acceptance and acknowledgement of his own experience.

But it is almost as if the project [design project] allows them to (…) slightly veer outside their silence to comment on dreams because they have been tilted in that direction by solid stuff written with regard to design ideas [2nd interview]

In short, it appears that the design project played a role in the development of interpersonal relationships, changing people’s outlook on him. Whilst Anthony’s artistic works were personal, his designs were based on a reality which was shared, or negotiated, with others. Working together towards a common goal was a medium to connect in an equal level and to help others, to contribute. His design works could be commented upon in relation to their function, while his artistic works, being personal, may not receive this kind of feedback. Design projects could therefore provide a safe space for people with psychosis to share and even use unusual ideas without being judged, mitigating the risks of social harm.

Discussion

This study helps form an initial understanding of how designing could support recovery, providing insights on how it differs from, or adds to, existing services.

First, Anthony introduces the concept of rhythm, portraying design as fast and slow. It may entail a dynamic experience, providing ways, through the interaction with the design situation, to shift from one particular mode of feeling and thinking to another. This resonates with recent research by Kannengiesser and Gero (Citation2019) who present an ontological model of fast and slow design thinking based on Daniel Kahneman’s model of human cognition which incorporates a fast and intuitive thinking system and a slow and tedious one.

Second, Anthony appears to attribute more self-agency to the activity of designing. While artistic inspiration (e.g. collage) is often perceived as directed by god, it is himself who designs, showing willingness to respond to the demands of the situation, some goal-directedness. Sass and Parnas (Citation2003) discuss that in psychopathological conditions such as schizophrenia, there can be no clear sense of goal-directedness, or associated differentiation of means from goal, no reason for attention to wend outward toward the world, rather than inward towards one’s own body or processes of thinking. The mechanisms via which the things that one should attend to, and those one should ignore, seem to be disrupted. Design behaviour is precisely characterized by this ability to iteratively frame the things that are relevant in a particular situation (Cross, Citation2001), navigating this goal-directedness, attending to the needs of the users. In a design process, there is no need for a specific goal to be preestablished, but a sense of purpose emerges through the process (Cross, Citation2001; Dorst & Cross, Citation2001). Through design, Anthony could feel directedness without being directed, a favourable condition for the emergence of a sense of agency.

Third, Anthony refers to design as more rooted in reality due to its function. In schizophrenia, the loss of the vital, embodied contact with reality may be expressed in complaints about a certain opacity of consciousness, like feeling in a fog, or a general existential feeling of being alien to the world (Fuchs & Röhricht, Citation2017). According to Fuchs (Citation2010) instead of serving as a medium of relating to the world, the body makes itself noticeable as disturbing or resistant and what was implicit becomes explicit and enters the focus of attention. The results from this case suggest that design’s rootedness in the world through function may have an impact on these processes and constitute an embodied and grounding experience. Designing, is experienced as rooted in reality, grounding, and it may have helped Anthony in turning towards, the world.

Finally, Anthony reports changes in how his work is received by others, which increases his sense of self-worth and confidence. In his account, he also refers to the design project as allowing him to interact with others unselfconsciously. Relationships forged through the activity of designing may be different from those facilitated by other activities. Anthony talked about how designs were not as easily dismissed and that through this project, people might be less inclined to dismiss him or his belief system. Although he emphasizes on the differences between designing and art, some of his experiences, such as that of relating unselfconsciously with others, align with conclusions made by Lynch et al. (Citation2019), who suggest art therapy may act like a buffer, giving autonomy over communicating. Furthermore, in this project, it appears that he is seeking acceptance, acknowledgement and respect helped. Isham et al. (Citation2021) pinpoint that being rejected or ridiculed by others (social harm) for one’s beliefs or associated behaviours is one of the possible harms of “delusions of exclusivity”, a term they use to replace “delusions of grandiosity”. For Anthony, design activity had mitigated those harms.

Of course, this study has limitations. First, as the lead author was also the facilitator of the co-design project, participants might have over-reported the positive effects, although this close rapport made in-depth discussions possible. Second, this case study’s findings cannot be generalized. Anthony is artistic, but others may be less inclined to engage with design. However, some of Anthony’s observations on design’s rootedness in reality, hold promise that design may be appealing to less artistic, or more practical individuals who don’t readily engage with art. Third, we selected Anthony’s case as his thoughtful account can help inform further practice, but as he engaged with the process most intensely, it is likely that he benefited more. Notwithstanding, other participants’ accounts were equally positive, just less detailed, which is why we considered it safe to select Anthony’s case as a first step, in line with IPA’s ideographic focus. Finally, Anthony participated in various activities simultaneously as part of the recovery process, and attended the space to socialize. Although this holistic approach seemed beneficial, it introduces interpretative ambiguity, limiting the ability to determine the precise role of design. Furthermore, although we presented some evidence of design’s benefits, it is not yet clear whether similar benefits may occur in other ways. Other environments that create safety may also facilitate people to increasingly “be in the world”, and the context and the role of the lead researcher is vital too.

Despite limitations, the perceived benefits justify further research. Anthony and the other participants drew on their own experiences and aspirations to create a boardgame that would benefit others. Participants’ experiences, contributed to the design process and helped generate valuable ideas. This proposition should be considered in informing further design projects and has profound social implications. It may mean, after all, that design may help rehabilitate (heal) psychosis clients as much as, and whilst, the psychosis clients may help (heal) the world.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all the research participants, and to Anthony, who shared his story and work. Thanks to the staff at Psychosis Therapy Project, and special thanks to Dorothee Bonnigal-Katz. This project was funded by Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aeferences blank for review

- Amiri, T., Wagenfeld, A., & Reynolds, L. (2017). User wellbeing: An entry point for collaboration between occupational therapy and design. Design for Health, 1(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2017.1386367

- Blake, V., Buhagiar, K., Kauer, S., Nicholas, M., Sanci, L., & Grey, J. (2016). Using participatory design to engage young people in the development of a new online tool to increase help-seeking. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 1(3), 68–83. http://cayr.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Blake_JAYS_v1n3_FINAL.pdf

- Cooper, K., Gillmore, C., & Hogg, L. (2016). Experience-based co-design in an adult psychological therapies service. Journal of Mental Health, 25(1), 36–40. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1101423

- Craig, C. (2017). Navigating unchartered territory. Design for Health, 1 (2), 149–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2017.1387002.

- Cross, N. (2001). Design Cognition: Results From Protocol And Other Empirical Studies Of Design Activity. Design Knowing and Learning: Cognition in Design Education (pp. 79–104). Elsevier, Oxford. http://oro.open.ac.uk/3285/1/DesignCognition.pdf

- Davidson, L. (2016). The Recovery Movement: Implications For Mental Health Care And Enabling People To Participate Fully In Life. Health Affairs, 35(6), 1091–1097. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0153

- Dixon, L. B., Holoshitz, Y., & Nossel, I. (2016). Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: Review and update. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20306

- Dorst, K., & Cross, N. (2001). Creativity in the design process: Co-evolution of problem–solution. Design Studies, 22(5), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(01)00009-6

- Flowers, P. (2008). Temporal tales: The use of multiple interviews with the same participant. JournalQualitative Methods in Psychology Bulletin. 5, 24–27.

- Fuchs, T. (2010). The Psychopathology of Hyperreflexivity. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, New Series, 24(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.24.3.0239

- Fuchs, T., & Röhricht, F. (2017). Schizophrenia and intersubjectivity. An embodied and enactive approach to psychopathology and psychotherapy. Philosophy, Psychiatry & Psychology 24(2). https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.2017.0018

- Gaver, B., Dunne, T., & Pacenti, E. (1999). Design: Cultural probes. Interactions, 6(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/291224.291235

- Glazzard, M., Kettley, R., Kettley, S., Walker, S., Lucas, R., & Bates, M. (2015). Facilitating a “non-judgmental” skills-based co-design environment. Proceedings of the Third European Conference on Design4Health (pp. 13–16). Sheffield, UK.http://research.shu.ac.uk/design4health/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/D4H_Glazzard_et_al.pdf

- Isham, L., Griffith, L., Boylan, A., Hicks, A., Wilson, N., Byrne, R., and Freeman, D. (2021). Understanding, treating, and renaming grandiose delusions: A qualitative study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12260

- Kaasgaard, K., & Lauritsen, P. (1997). Participatory design at a psychiatric daycenter: Potentials and problems. In C. Pappas, N. Maglaveras, & J.R. Scherrer (Eds.), Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 43 Pt B, (pp. 816–820). Medical Informatics Europe ‘97, Amsterdam: IOS Press. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10179781

- Kannengiesser, U., & Gero, J. S. (2019). Design thinking, fast and slow: A framework for Kahneman’s dual-system theory in design. Design Science, 5, e10. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2019.9

- Kettley, S., Sadkowska, A., & Lucas, R. (2016). Tangibility in e-textile participatory service design with mental health participants. In P. Lloyd & E. Bohemia (Eds.),Proceedings of DRS 2016, Design Research Society 50th Anniversary Conference. Future Focused Thinking - DRS International Conference 2016, 27–30 June, Brighton, United Kingdom. DRS digital library. Brighton, UK. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2016.488

- Larkin, M., Boden, Z. V. R., & Newton, E. (2015). On the Brink of Genuinely Collaborative Care. Qualitative Health Research, 25(11), 1463–1476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315576494

- Lynch, S., Holttum, S., & Huet, V. (2019). The experience of art therapy for individuals following a first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape, 24(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2018.1475498

- Mulvale, A., Miatello, A., Hackett, C., & Mulvale, G. (2016). Applying experience-based co-design with vulnerable populations: Lessons from a systematic review of methods to involve patients, families and service providers in child and youth mental health service improvement. Patient Experience Journal, 3(1), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1104

- Mužina, T. (2020). Co-design of an app used to monitor symptoms of depression in young adults. In K. Christer, C. Craig & P. Chamberlai (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Design4HealthAmsterdam, Netherlands, 1st-3rd July 2020 (pp. 441–451). https://research.shu.ac.uk/design4health/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/D4H-Proceedings-2020-Vol-3-Final.pdf

- Nakarada-Kordic, I., Hayes, N., Reay, S. D., Corbet, C., & Chan, A. (2017). Co-designing for mental health: Creative methods to engage young people experiencing psychosis. Design for Health, 1(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2017.1386954

- Ospina-Pinillos, L., Davenport, T., Diaz, A. M., Navarro-Mancilla, A., Scott, E. M., & Hickie, I. B. (2019). Using participatory design methodologies to co-design and culturally adapt the Spanish version of the mental health eClinic: Qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(8), e14127. https://doi.org/10.2196/14127

- Petermans, A., & Cain, R. (2020). Design for wellbeing : An applied approach. Routledge.

- Sanders, E. B.-N. (2000). Generative Tools for Co-designing. In S. A. R. Scrivener, L. J. Ball, & A. Woodcock (Eds.), Collaborative design (pp. 3–12). Springer London.

- Sass, L. A., & Parnas, J. (2003). Schizophrenia, consciousness, and the self. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29(3), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007017

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner : How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=WZ2Dqb42exQC

- Starks, H., & Brown Trinidad, S. (2007). Choose Your Method: A Comparison of Phenomenology, Discourse Analysis, and Grounded Theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

- Tsekleves, E. (2020). Co-design and participatory methods for wellbeing | Design for Wellbeing. In A. Petermans & R. Cain (Eds.), Design for wellbeing: An Applied Approach. London: Routledge. https://learning-oreilly-com.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/library/view/design-for-wellbeing/9781351355582/xhtml/chapter8.xhtml#chapter8

- Wadley, G., Lederman, R., Gleeson, J., & Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2013). Participatory design of an online therapy for youth mental health. Proceedings of the 25th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Augmentation, Application, Innovation, Collaboration - OzCHI ’13, 517–526. Adelaide, Australia. https://doi.org/10.1145/2541016.2541030

- Warwick, L., Tinning, A., Smith, N., & Young, R. (2018). Co-designing Wellbeing: The commonality of needs between co-designers and mental health service users. Design Research Society 2018 Conference: Catalyst - University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2018.405