ABSTRACT

Background

First-episode psychosis (FEP) refers to the first time someone experiences an episode of psychosis, which can be frightening and confusing, leading people to make their first contact with early intervention services. Early intervention is widely accepted as beneficial for long-term recovery and symptom management. A universal feature of intervention is a relationship with mental health practitioners. Therapeutic relationships experienced as positive are also associated with better outcomes across mental health settings. However, little is known about what is helpful within therapeutic relationships for people with FEP

Method

The current review aimed to develop a rich understanding of beneficial features of therapeutic relationships for people with FEP to enhance service delivery. Databases searched were: APA PsycInfo, MEDLINE Complete, CINAHL.

Results

A systematic search yielded 178 papers, of which 16 met the inclusion criteria. Publications reviewed were from Singapore, Western Finnish Lapland, England, Canada, the United States of America, Denmark, and Australia. The papers were published across 12 journals; 81% were qualitative, 12% were quantitative, and one was a mixed methods study.

Discussion

It is recommended that creating a safe space to talk, taking a non-judgemental approach, and developing trust between practitioner and client should be prioritised for people with FEP.

Early intervention is widely recognised as essential to prevent longer-term symptoms and reduce suffering associated with first-episode psychosis (FEP) (O’Donoghue et al., Citation2021). However, practices vary enormously in terms of how early intervention for FEP ends, which can influence the person’s wellbeing as time goes on, with recent calls to enhance step-down care for at risk groups (Hyatt, Hasler, & Wilner, Citation2022). There is also a crucial role for therapeutic relationships to promote optimal outcomes for people with psychosis, although further robust research is required to explore this further (Priebe et al., Citation2011).

In the UK, clinicians are guided towards both pharmacological and psychological treatments; with antipsychotic medication, individual CBT, and family therapy recommended (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2014). Research regarding the efficacy of pharmacological treatments is equivocal, with some studies finding medication offers no significant improvement in functioning compared to psychological interventions (Francey et al., Citation2020). With consideration for the severity of side effects for some people prescribed antipsychotic medications, notably significant weight gain, sedation effects, and further psychosis-affiliated symptoms (Correll et al., Citation2009; Krause et al., Citation2018), psychological interventions can offer a helpful pathway for psychoeducation, coping strategies, and symptom management.

An essential feature of any talking therapy is the therapeutic relationship. The therapeutic relationship refers to the working relationship between client and mental health practitioner, “built on mutual trust, understanding and a collective knowledge” (Strachan, Citation2011, p. 2). The therapeutic relationship is a known predictor of positive therapeutic outcomes (Cox & Miller, Citation2021; Shirk & Karver, Citation2003), regardless of intervention type (Ardito & Rabellino, Citation2011) or method of intervention delivery (Sucala et al., Citation2012). Therefore, understanding beneficial features of therapeutic relationships for people with FEP could enhance service delivery across talking therapies and also briefer encounters with wider mental health practitioners (MHPs), such as with their nurse or psychiatrist during a medication review, or in planning meetings with a care coordinator.

Currently, helpful components of therapeutic value in relationships with MHPs for people with psychosis include the normalising symptoms of psychosis (Byrne & Morrison, Citation2014) and collaboration (Byrne & Morrison, Citation2010). Components that negatively affect the therapeutic relationship include stigma (Harris et al., Citation2012) and a lack of consistency from the care provider (Uttinger et al., Citation2018). However, there is no consensus on which components of the relationship contribute to its predictive value within the context of FEP. Therefore, the current review attends specifically to the therapeutic relationship for people with FEP, where they are likely to have their first encounter with frightening symptoms and MHPs in early intervention services.

This narrative review explores an emerging body of literature with the aim of developing a richer understanding of the therapeutic relationship for people with FEP accessing treatment. With greater knowledge of beneficial therapeutic mechanisms for people in this unique circumstance, care could be better tailored to meet their needs, offering bespoke support to people experiencing distressing symptoms and associated symptom-related distress. Narrative reviews form a substantial subsection of medical and clinical research (Bastian et al., Citation2010), particularly relevant for this review due to the bringing together of the emerging FEP literature, alongside a heterogenous and expansive knowledge base around therapeutic relationships (Ferrari, Citation2015).

Method

Eligibility criteria

For inclusion in the review, manuscripts were required to be written in English, published in a peer reviewed journal, available to access in full, explicitly state components of the therapeutic relationship with MHPs, include quotes direct from the experiences of people who have experienced FEP, and state their method for analysis.

Information sources

The databases searched were: APA PsycInfo, MEDLINE Complete, CINAHL.

Search strategy

A systematic approach was taken to source specific papers relevant to the review question. Two separate searches were conducted initially, which applied specific criteria. The first search was for papers including iterations of the term “first episode psychosis” within the paper title and/or abstract. The second search was for iterations of the term “therapeutic relationships” within the paper title and/or abstract. The two searches were then run simultaneously (). Papers were excluded if they discussed psychosis not in relation to FEP, relationships that might have been therapeutic or supportive but not with mental health practitioners (e.g. with spiritual leaders), or that did not hear from first person accounts of direct experience (e.g. family members).

Table 1. Search terms.

In total, 178 papers were found in relation to the search terms, 53 papers were removed as exact duplicates. Test searches were conducted to ensure notable papers were included within the database search results. The remaining 125 papers were assessed according to the inclusion criteria. Following this selections process, 109 papers were removed because they did not fully meet the inclusion criteria, which resulted in 16 papers that met the inclusion criteria for the review. Finally, the reference sections of the selected papers were checked for any additional potential publications for inclusion, but none were found.

Data extraction and analysis

Due to the limited number of papers relating specifically to aspects of the therapeutic relationship for people with FEP, publications employing quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods were included for review. The overarching themes identified in the review were developed inductively, based upon the frequency and salience of categories of information within the identified literature, following practices of coding, mapping and categorisation employed for content analysis (Bengtsson, Citation2016). Specifically, the results and thematic findings of the selected studies were coded individually according to the review question. These codes were then tabulated into categories, which were then grouped based on frequency and similarity to form themes.

Throughout the review, components of the therapeutic relationship shared similar features, resulting in a challenge to define their purpose to mobilise knowledge in the area. For example, in relation to communication, this involved the ability to talk about difficult experiences that were important within the therapeutic relationship (Bergström et al., Citation2021), communication as in dedicating time to talk (Tindall, Allott, et al., Citation2018), and talking through experiences of psychosis to share an understanding of symptoms (Allard et al., Citation2018; Tindall et al., Citation2015). Through the synthesis process, a general theme would typically emerge from the categories of data, for example, a “safe space to talk”, and the nuances within the themes would further inform the analysis and conclusions drawn. Therefore, codes formed categories, which informed the development of overarching themes, with relevant subthemes represented across multiple papers ().

Table 2. Data extraction summary.

Findings

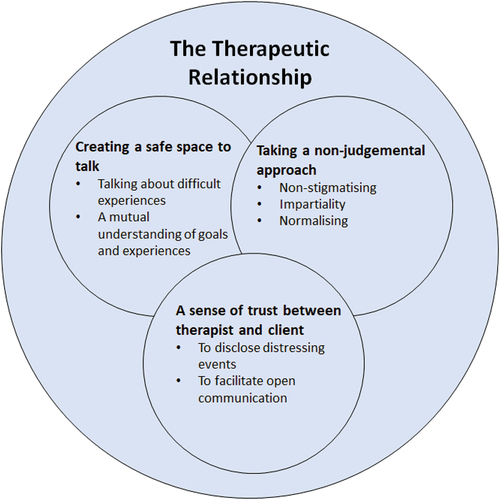

Three themes emerged: creating a safe space to talk, taking a non-judgemental approach, and developing a sense of trust between MHP and client, summarised in Figure One.

Creating a safe space to talk

Creating a safe space to talk about FEP experiences was represented across 50% of the papers reviewed (Allard et al., Citation2018; Barr et al., Citation2015; Bergström et al., Citation2021; Griffiths et al., Citation2019; Mankiewicz et al., Citation2018; Tindall et al., Citation2015; Tindall, Allott, et al., Citation2018; Tindall, Simmons, et al., Citation2018). Multiple components of the relationship contributed to this. For example, the Open Dialogue model focuses on talking through difficult experiences. Treatment involves meetings with the individual’s family and social network, with the presence of MHPs, to increase understanding of the psychosis experience (Seikkula & Jukka Aaltonen, Citation2001). Individuals with FEP had discussed in semi-structured interviews the feeling of being able to talk through difficult experiences in these meetings was a key factor in building a therapeutic relationship (Bergström et al., Citation2021). However, only individuals with more severe symptomatology were interviewed, who were still actively engaged in treatment 10–23 years beyond FEP.

In contrast to Bergström et al. (Citation2021), Tindall et al. (Citation2015) interviewed individuals currently undergoing treatment for FEP. Participants were excluded if they were being treated in acute services or had acute symptoms, thus, likely presented with less severe symptomatology. Similar to the core components of the Open Dialogue approach, participants spoke of how a space to talk created a mutual understanding between participant and case manager, which strengthened the therapeutic relationship. The relationship then promoted engagement in therapy (Tindall et al., Citation2015). These findings are likened to that of Griffiths et al. (Citation2019), whereby participants described how shared goals for therapy strengthened the relationship. Therefore, creating a safe space to talk facilitates multiple components that benefit the relationship; not only the ability to discuss difficult or distressing topics, but also to create a shared understanding. It is important that MHPs consider how to create a safe space when implementing interventions with individuals experiencing FEP. Goal setting, aiding understanding of FEP, and allowing discussion of difficult topics could all lead to an enhanced therapeutic outcome.

A meta-synthesis analysed nine studies across different stages of treatment; six of the nine studies suggested dedicating time to talk and being understood by the mental health practitioner within those discussions was the most important component of the relational process (Tindall, Simmons, et al., Citation2018). Creating this space to talk was a prevalent finding across clinical settings, thus is likely a key component in strengthening the therapeutic relationship. However, Tindall, Simmons, et al. (Citation2018) recognised that little consideration was given in these studies to potential socio-economic or ethnic disparities in the views of the therapeutic relationship. For example, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities might be proportionately more likely to receive a psychosis spectrum diagnoses (Jongsma et al., Citation2019), yet might be less likely to engage in mental health services (Dixon et al., Citation2016). Therefore, so-called “disengaged voices” could have referred to people who, for intersectional reasons, may feel as though services, and thus research opportunities, are less accessible. Missed opportunities to hear from people who are less likely to access services could lead to poorer therapeutic outcomes and maintain barriers to help. Mental health services should consider asking their BAME clients experiencing FEP how they could work to create a safe space to talk through their experiences and what it is about talking through experiences that helps. This could be a first step towards developing culturally sensitive EIP services.

A sense of trust between MHP and client

Trust was explicitly mentioned as a key component in five of the identified papers (Chua et al., Citation2022; Jansen et al., Citation2018; Mankiewicz et al., Citation2018; Tindall, Allott, et al., Citation2018; Tong et al., Citation2018). Trust was mentioned less frequently than a safe space to talk but was particularly important when therapy was trauma-focused (Tong et al., Citation2018), potentially due to the sensitive nature of such disclosures. Participants that underwent trauma-specific treatment for FEP described how trusting their MHP allowed them to talk openly about their trauma, which deepened the therapeutic relationship (Tong et al., Citation2018). A history of trauma is not uncommon amongst individuals experiencing FEP (Vila-Badia et al., Citation2021). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms following FEP are approximately 42%, and the experience of FEP itself could be traumatic enough to induce PTSD (Rodrigues & Anderson, Citation2017). Therefore, trust is crucial to enable safe disclosure that aids the relationship, and resultantly, therapeutic outcome. EIP services should focus on building trust with a client as soon as they become known to a service, particularly in individuals with a history of trauma, to increase the chance of a strong therapeutic connection when therapy begins.

Studies that do not focus specifically on trauma-specific treatment have equally emphasised trust as an important component of the therapeutic relationship. Semi-structured interviews with individuals experiencing FEP who had recently completed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Psychosis (CBTp) revealed trust and impartiality as the most important qualities of a therapist, as these features facilitated honest, open communication (Mankiewicz et al., Citation2018). This suggested that trust between client and therapist was a key facilitator of other components of the relationship.

Taking a non-judgemental approach

A non-judgemental approach was highlighted as a key component of the therapeutic relationship for individuals with FEP across 50% of the studies reviewed (Barr et al., Citation2015; Bergström et al., Citation2021; Cox & Miller, Citation2021; Griffiths et al., Citation2019; Jansen et al., Citation2018; Mankiewicz et al., Citation2018; Tindall, Allott, et al., Citation2018; Tong et al., Citation2018). A non-judgemental approach was key in EIP services, even beyond FEP-specific treatment (Barr et al., Citation2015). Many recognised components of the therapeutic relationship fell under the overarching theme of a non-judgemental approach (see ), such as impartiality (Mankiewicz et al., Citation2018) and normalising experiences of FEP (Allard et al., Citation2018; Mankiewicz et al., Citation2018). Notably, what occurred most within these studies was that stigmatisation of clients’ experiences of psychosis contributed to a feeling of judgement that hindered the therapeutic relationship. This was described in Tindall et al. (Citation2015) by a participant who was asked “do you go crazy?” (p.300) by a doctor. Interpretations of judgement by service users and feeling misunderstood by some mental health practitioners could induce feelings of judgement within clients.

Empathy, mirroring, and attempts at connection were found to be barriers to the therapeutic relationship in one study (Belanger et al., Citation2018). This contrasting finding provides a new insight into the uniqueness of the therapeutic relationship experience between service users, as findings elsewhere praised the therapist for being relatable (Tong et al., Citation2018), warm and sensitive (Tindall et al., Citation2015).

However, Belanger’s et al. (Citation2018) findings noted the client “continues to react defensively” (p.7) and attributed “pre-existing schemas of danger and mistrust” (p.12) for therapeutic relationship breakdown. This observation could explain why components of the relationship that would typically be viewed as positive were described as barriers. It is possible the participant in the study had a positive view of the relationship, but this was not ascertained. This study is therefore important to review, as it suggested a wider issue of stigma surrounding the way FEP is described within mental healthcare. Practitioners can learn from the language used in this study, by adopting normalising and validating language when discussing clients, and prioritising the client’s views of the therapeutic relationship alongside their own.

Studies that ascertained the service user’s view of the relationship have suggested a non-judgemental approach reduces stigma, thus strengthening the therapeutic relationship.

Participants commonly described a fear of being stigmatised (such as being labelled “crazy”) as a barrier to disclosure and help-seeking that prolonged DUP. However, a non-stigmatising environment of helpful questioning and validation aided disclosure, thus strengthening the therapeutic relationship (Jansen et al., Citation2018). As reduced DUP is predictive of reduced symptomatology (Malla et al., Citation2002), reducing internalised stigma within therapy is crucial to improve therapeutic outcomes. Therefore, to take a non-judgemental approach within the therapeutic relationship, practitioners should adopt non-stigmatising language, and create a non-stigmatising environment for clients through validation and normalising of FEP experiences.

Discussion

The current review addressed a gap in the literature base by exploring experiences of the therapeutic relationship for individuals with FEP. Three overarching themes emerged from the analysis. Creating “a safe space to talk” allowed service users to talk through difficult experiences and create a mutual understanding of goals between service user and therapist. Developing “a sense of trust between the therapist and client” facilitated open communication that allowed for disclosure of distressing events. Taking “a non-judgemental approach” created impartiality and normalising of experiences and reduced stigma.

A safe space to talk was a key theme in over half of the included literature. Developing a mutual understanding and being able to openly and freely talk about difficult experiences formed a safe space to talk through FEP experiences, that participants across studies said strengthened their therapeutic relationship. A sense of trust was explicitly mentioned across studies as key to building a relationship, particularly as it allowed for disclosure of traumatic experiences, and facilitated open and honest communication between client and therapist. Lastly, impartiality and normalising of experiences, as well as reducing stigma of the FEP experience, all contributed to a non-judgemental atmosphere between therapist and client that strengthened the relationship. From these findings, a suggested update of Strachan (Citation2011)’s current definition of the therapeutic relationship for people with FEP would be a relationship built on mutual trust, a safe space to talk, and a non-judgemental approach.

It is important to note that all themes and subthemes are interlinked. For example, normalising experiences would naturally reduce stigma, and facilitating open communication could allow for easier disclosure of distressing events. Therefore, the features of therapeutic value identified should be applied in conjunction with each other to create a strong rapport between therapist and client, to improve therapeutic outcome. A strong therapeutic relationship has shown to be a prerequisite to engagement with early intervention treatments (Melau et al., Citation2015). If practitioners wish to create a strong relationship to facilitate engagement, they should prioritise creating a non-stigmatising environment from the initial point of contact, to reduce this barrier as much as possible from the start.

Findings in context

The findings of this review contribute to the current knowledge base in terms of relapse prevention, mobilising knowledge in relation to helpful features of therapeutic relationships for people with FEP. In terms of wider approaches tailored for FEP, a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated the importance of specialised FEP programmes for reducing relapse rates and hospital stays post-FEP (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., Citation2011). Specialist programmes hosted MHPs with relatively small caseloads, providing individual and family therapeutic interventions alongside psychoeducation, crisis management and low-dose medication. However, there was no assessment or exploration among these studies of the role of the therapeutic relationship within such programmes.

Multiple studies within this review’s findings have suggested that a strong therapeutic relationship contributes to engagement and therapeutic outcome (Jansen et al., Citation2018; Mankiewicz et al., Citation2018; Melau et al., Citation2015; Tindall et al., Citation2015). Therefore, this review’s findings address an area in need of knowledge mobilisation; a strong therapeutic relationship facilitates treatment adherence to such programmes, and there are key components of the therapeutic relationship that can strengthen these working alliances. The identified key components should therefore be explored in future RCTs studying FEP relapse prevention. For example, a study could elicit qualitative feedback from service users as to the most beneficial components of the therapeutic relationship and compare the feedback to quantitative data gathered on therapeutic outcome, such as symptom reduction, subjective scores of quality of life, or hospital admission reduction. Such findings could provide validity for these key components as beneficial for therapeutic outcome.

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this review both corroborate and advance longstanding theoretical models of the therapeutic relationship within psychotherapy and psychiatry, connecting factors of therapeutic value specifically to FEP. The overarching themes in this review highlight the importance of co-creating a shared social space between practitioner and client that values a sense of trust. Cognitive behaviourism, which forms the basis for CBT used within FEP therapy, values the “self-concept” within the relationship; disengagement or resistance to therapy could be based on the service user resisting the idea of “mental illness” within their concept of themselves, due to stigma (McGuire et al., Citation2001). Similarly, a non-judgemental approach is highly valued by service users, which could help to reduce stigma associated with psychosis, perhaps further promoting self-concept clarity. This review has therefore identified how elements of these theoretical models can be applied in practice through the therapeutic relationship with people with FEP.

Considering the high levels of trauma exposure for many participants of the reviewed studies, it would be advantageous for future research to explore how therapeutic relationships may influence and nurture self-concept clarity, which is a mediator between trauma and psychosis (Evans et al., Citation2015). However, the findings of this review should be considered with a degree of caution due to some studies hearing only from people experiencing severe symptoms of FEP, others with mild symptomology, and were generally under-representative of minority ethnicities; a challenge across the psychosis spectrum literature. Further research into beneficial relationships with people across educational, social and spiritual communities could also offer important insights into how therapeutic relationships across settings could support people with FEP, and thus reduce the likelihood of future distress.

Clinical implications

The “service user experience” guideline of NICE (Citation2014; 1.1.1) currently states the importance of clinicians taking “time to build supportive and empathetic relationships as an essential part of care” (NICE, Citation2014). The current review offers timely, clinically necessary, and novel information as to how clinicians can do this with people with FEP, and how to convey support and empathy. To be supportive, mental health practitioners should normalise the FEP experience to reduce stigma. Consequently, normalising experiences could aid trust building with clients, which would allow for open communication. Mental health practitioners could also be supportive by understanding a client’s goals for therapy and helping them to understand their FEP experiences. Being empathetic towards clients, as stated in the guideline, should particularly be shown when clients disclose difficult experiences and/or trauma, to further build trust.

The current review identified a scarcity of research into experiences of the therapeutic relationship for individuals with FEP and psychosis symptoms for young people in general, which should be a research priority. Research with under-represented groups, such as young people and people from BAME communities could meaningfully inform service development, measures, interventions and tailored approaches for therapeutic relationships to promote optimal outcomes and engagement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allard, J., Lancaster, S., Clayton, S., Amos, T., & Birchwood, M. (2018). Carers’ and service users’ experiences of early intervention in psychosis services: Implications for care partnerships. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(3), 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12309

- Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Parker, A. G., Hetrick, S. E., McGorry, P. D., & Gleeson, J. F. (2011). Preventing the second episode: A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia bulletin, 37(3), 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp129

- Ardito, R., & Rabellino, D. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: Historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 270. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270

- Barr, K., Ormrod, J., & Dudley, R. (2015). An exploration of what service users value about early intervention in psychosis services. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 88(4), 468–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12051

- Bastian, H., Glasziou, P., & Chalmers, I. (2010). Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: How will we ever keep up? PLoS medicine, 7(9), e1000326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326

- Belanger, E. A., Leonhardt, B. L., George, S. E., Firmin, R. L., & Lysaker, P. H. (2018). Negative symptoms and therapeutic connection: A qualitative analysis in a single case study with a patient with first episode psychosis. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000107

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursing Plus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

- Bergström, T., Alakare, J., Holma, J., Köngäs-Saviaro, P., Taskila, J. J., & Seikkula, B. (2021). Retrospective experiences of first-episode psychosis treatment under open dialogue-based services: A qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa050

- Byrne, R., & Morrison, A. P. (2010). Young people at risk of psychosis: A user-led exploration of interpersonal relationships and communication of psychological difficulties. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 4(2), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00171.x

- Byrne, R., & Morrison, A. P. (2014). Young people at risk of psychosis: Their subjective experiences of monitoring and cognitive behaviour therapy in the early detection and intervention evaluation 2 trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 87(3), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12013

- Chua, Y. C., Tang, C., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., Shahwan, S., Cetty, L., Yong, Y. H., Hon, C., Ang, S., Verma, S., & Subramaniam, M. (2022). Therapeutic alliance with case managers in first-episode psychosis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 72, 103122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103122

- Correll, C. U., Manu, P., Olshanskiy, V., Napolitano, B., Kane, J. M., & Malhotra, A. K. (2009). Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotics during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, 302(16), 1765–1773. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1549

- Cowan, T., Pope, M. A., MacDonald, K., Malla, A., Ferrari, M., & Iyer, S. N. (2020). Engagement in specialized early intervention services for psychosis as an interplay between personal agency and critical structures: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 108, 103583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103583

- Cox, L., & Miller, C. (2021). A qualitative systematic review of early intervention in psychosis service user perspectives regarding valued aspects of treatment with a focus on cognitive behavioural therapy. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X2100026X

- Dixon, L. B., Holoshitz, Y., & Nossel, I. (2016). Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: Review and update. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20306

- Evans, G. J., Reid, G., Preston, P., Palmier-Claus, J., & Sellwood, W. Trauma and psychosis: The mediating role of self-concept clarity and dissociation. (2015). Psychiatry Research, 228(3), 626–632. Epub 2015 Jun 11. PMID: 26099655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.053.

- Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature Reviews. The European Medical Writers Association, 24(4), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

- Ferrari, M., Flora, N., Anderson, K. K., Tuck, A., Archie, S., Kidd, S., & McKenzie, K. (2015). The African, Caribbean and European (ACE) pathways to care study: A qualitative exploration of similarities and differences between African-origin, Caribbean-origin and European-origin groups in pathways to care for psychosis. BMJ Open, 5(1), e006562. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006562

- Francey, S. M., O’Donoghue, B., Nelson, B., Graham, J., Baldwin, L., Yuen, H. P., Kerr, M. J., Ratheesh, A., Allott, K., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Fornito, A., Harrigan, S., Thompson, A. D., Wood, S., Berk, M., & McGorry, P. D. (2020). Psychosocial intervention with or without antipsychotic medication for first-episode psychosis: A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa015

- Griffiths, R., Mansell, W., Edge, D., Carey, T. A., Peel, H., & Tai, S. J. (2019). ‘It was me answering my own questions’: Experiences of method of levels therapy amongst people with first-episode psychosis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(3), 721–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12576

- Harris, K., Collinson, C., & Das Nair, R. (2012). Service-users’ experiences of an early intervention in psychosis service: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 85(4), 456–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02043.x

- Hyatt, A. S., Hasler, V., & Wilner, E. K. (2022). What happens after early intervention in first-episode psychosis? Limitations of existing service models and an agenda for the future. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 35(3), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000785

- Jansen, J. E., Pedersen, M. B., Hastrup, L. H., Haahr, U. H., & Simonsen, E. (2018). Important first encounter: Service user experience of pathways to care and early detection in first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12294

- Jongsma, H. E., Turner, C., Kirkbride, J. B., & Jones, P. B. (2019). International incidence of psychotic disorders, 2002–17: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4(5), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30056-8

- Krause, M., Zhu, Y., Huhn, M., Schneider-Thoma, J., Bighelli, I., Chaimani, A., & Leucht, S. (2018). Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia: A network meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(6), 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.03.008

- Lester, H., Marshall, M., Jones, P., Fowler, D., Amos, T., Khan, N., & Birchwood, M. (2011). Views of young people in early intervention services for first-episode psychosis in England. Psychiatric Services, 62(8), 882–887. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.8.pss6208_0882

- Malla, A. K., Norman, R. M. G., Manchanda, R., Ahmed, M. R., Scholten, D., Harricharan, R., Cortese, L., & Takhar, J. (2002). One year outcome in first episode psychosis: Influence of DUP and other predictors. Schizophrenia Research, 54(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00254-7

- Mankiewicz, P. D., O’Leary, J., & Collier, O. (2018). ‘That hour served me better than any hour I have ever had before’: Service users’ experiences of CBTp in first episode psychosis. Counselling Psychology Review, 33(2), 4–16.

- McGuire, R., McCabe, R., & Priebe, S. (2001). Theoretical frameworks for understanding and investigating the therapeutic relationship in psychiatry. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36(11), 557–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270170007

- Melau, M., Harder, S., Jeppesen, P., Hjorthøj, C., Jepsen, J. R. M., Thorup, A., & Nordentoft, M. (2015). The association between working alliance and clinical and functional outcome in a cohort of 400 patients with first-episode psychosis: A cross-sectional study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(01), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08814

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014, February 12). “1 Recommendations | Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management | Clinical guideline [CG178]”|. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/chapter/1-Recommendations

- O’Donoghue, B., O’Connor, K., Thompson, A., & McGorry, P. (2021). The need for early intervention for psychosis to persist throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(3), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.56

- Priebe, S., Richardson, M., Cooney, M., Adedeji, O., & McCabe, R. (2011). Does the therapeutic relationship predict outcomes of psychiatric treatment in patients with psychosis? A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 80(2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1159/000320976

- Rodrigues, R., & Anderson, K. K. (2017). The traumatic experience of first-episode psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 189, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.045

- Seikkula, B. A., & Jukka Aaltonen, J. (2001). Open dialogue in psychosis I: An introduction and case illustration. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 14(4), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/107205301750433397

- Shirk, S. R., & Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 452–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.452

- Strachan, H. (2011). Caring–the concept, behaviours, influences and impact. NMAHP Quality Council, 1–19.

- Sucala, M., Schnur, J. B., Constantino, M. J., Miller, S. J., Brackman, E. H., & Montgomery, G. H. (2012). The therapeutic relationship in e-therapy for mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(4), 2084. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2084

- Tindall, R. M., Allott, K., Simmons, M., Roberts, W., & Hamilton, B. E. (2018). Engagement at entry to an early intervention service for first episode psychosis: An exploratory study of young people and caregivers. Psychosis: Psychological, Social and Integrative Approaches, 10(3), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2018.1502341

- Tindall, R., Francey, S., & Hamilton, B. (2015). Factors influencing engagement with case managers: Perspectives of young people with a diagnosis of first episode psychosis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(4), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12133

- Tindall, R. M., Simmons, M. B., Allott, K., & Hamilton, B. E. (2018). Essential ingredients of engagement when working alongside people after their first episode of psychosis: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(5), 784–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12566

- Tong, J., Simpson, K., Alvarez‐jimenez, M., & Bendall, S. (2018). Talking about trauma in therapy: Perspectives from young people with post‐traumatic stress symptoms and first episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(5), 1236–1244. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12761

- Uttinger, M., Koranyi, S., Papmeyer, M., Fend, F., Ittig, S., Studerus, E., Ramyead, A., Simon, A., & Riecher-Rössler, A. (2018). Early detection of psychosis: Helpful or stigmatizing experience? A qualitative study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12273

- Vila-Badia, R., Butjosa, A., Del Cacho, N., Serra-Arumí, C., Esteban-Sanjusto, M., Ochoa, S., & Usall, J. (2021). Types, prevalence and gender differences of childhood trauma in first-episode psychosis. What is the evidence that childhood trauma is related to symptoms and functional outcomes in first episode psychosis? A systematic review. Schizophrenia Research, 228, 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.11.047