ABSTRACT

Background

Identifying facilitators and barriers to help-seeking for first-episode psychosis (FEP) is a topic growing in research and clinical interest, particularly lived experience perspectives. This meta-ethnography aimed to synthesize the findings of qualitative studies that explored personal accounts of help-seeking for FEP.

Methods

A meta-ethnography was conducted: seventeen primary articles were identified reviewed, synthesized and interpreted.

Results

The synthesis indicated a chronological process – initially most people did not seek help and attributed their experiences to other stressors. As FEP intensified, uncertainty grew about their initial interpretations, leading to the generation of alternative explanatory frameworks as a form of sense-making. This led to or delayed help-seeking, depending on the types of involvement from significant others and services. If effective help was not sought early enough, most participants experienced a “tipping point”, leading to urgent psychiatric and medical intervention. Throughout, individual, gender and ethnic differences played a role in facilitating or delaying help-seeking.

Discussion

FEP and help-seeking appear to be a process affected by, and related to, intertwining intra- and interpersonal, cultural, individual and systemic roles.

Introduction

A First-Episode Psychosis (FEP) refers to the time a person first has psychotic experiences and can have a significant impact on a person’s wellbeing, becoming an important target for services to facilitate effective intervention and care. Because a FEP can initially go undetected by services, growing interest has been on early detection for psychosis over the past several years, including detecting characteristics, facilitators and barriers to help-seeking (Albert & Weibell, Citation2019). Help-seeking can be generally understood as “communicating with other people to obtain help in terms of advice, information, treatment and general support in response to a problem or distressing experience” (Rickwood et al., Citation2005, p. 4). One systematic review explored first-person accounts on FEP and recommended centering mental health care on the patient’s needs, arguing that current understandings of psychotic distress have emphasized service outcomes more than patient needs (Griffiths et al., Citation2018).

Aims

There has not been a meta-ethnography to date on the facilitators and barriers to help-seeking for FEP from the perspectives of people with personal experiences of it. This meta-ethnography aims to explore:

What are the facilitators to help-seeking for FEP, from the perspectives of people with personal accounts of FEP?

What are the barriers to help-seeking for FEP, from the perspectives of people with personal accounts of FEP?

Methodology

Epistemological position

The authors of this meta-ethnography adopted a critical realist stance and acknowledge that not everyone who has FEP experiences finds them distressing or concerning, and that not everyone wants to seek help for it. Articles identified in the systematic search tended to focus on access to services from mental health teams. As such the focus of the synthesis is on those people who access mental health services and may not represent those who sought help elsewhere and did not present to services.

Systematic literature search

Search strategy

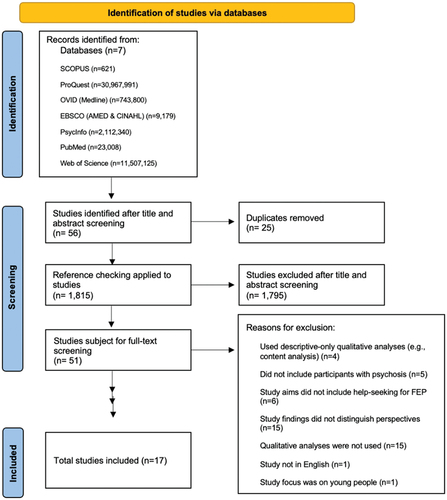

Seven electronic databases were searched between November 2022 and January 2023: SCOPUS, ProQuest, OVID (Medline), PsycInfo, PubMed, EBSCO (AMED & CINAHL) and Web of Science, along with reference checking (Booth, Citation2016) (See ). Mendeley Reference Manager (Mendely, Citation2023) was used to import and manage references into separate folders for each database. lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the rationale for the criteria when screening search terms.

Table 1. Search terms.

Systematic screening process

As shown in , the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model (Moher, Citation2009) illustrated the systematic selection process (Liberati et al., Citation2009). Mendeley was also used; each folder that was allocated to a database was manually screened during title, abstract and full-text screening. For the ProQuest database, a very large number of hits (n = 30, 967, 991) were generated from several sources, the largest including newspaper articles, magazines and audio and video material. Once sources on ProQuest were excluded to only include “Scholarly Journals” (which resulted in a similar number of hits as other databases) the titles and abstracts were screened by hand.

Data extraction

lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with the rationale for the inclusion of studies. lists the study characteristics: author and year, country, epistemological position, sample size, and research method and analytical tool.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 3. Study characteristics.

Participant characteristics

displays participant characteristics of each study: age, gender and ethnicity. The combined sample size across all studies was 609 participants. It was not possible to accurately summarize mean ages, genders or ethnic composition across studies due to the variation in reporting methods.

Table 4. Participant characteristics.

Quality appraisal

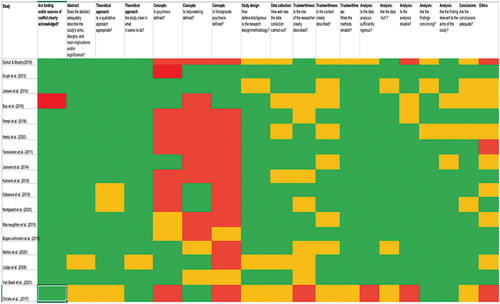

A 19-item checklist was created by combining two qualitative standard checklists (Levitt et al., Citation2018; NICE, Citation2022). Three additional items were included to assess a study’s clarity in defining concepts: psychosis, FEP and help-seeking. This was done in conjunction with an academic methods group within the host institution, designed to facilitate reflexive dialogue and offer multiple perspectives for quality appraisal and synthesis (Toye et al., Citation2013).

All 17 studies met or partially met most of the criteria listed; strengths across studies included the reporting of theoretical approaches, justifying the use of a qualitative approach and demonstrating reliability and rigor. The quality varied in how data collection and analyses were described, such as with researcher roles. Most studies did not meet the criteria in defining concepts of psychosis like FEP or help-seeking. This is illustrated in , a color-coded reflection of the checklist: green for criteria met, yellow for criteria partially met and red for criteria not met at all.

Theme extraction: data analysis and synthesis

This meta-ethnography followed Noblit and Hare’s (Citation1988) guidance on conducting meta-ethnographies, consisting of steps to follow or “phases”. Phases “Getting started” and “deciding what was relevant” were completed during the development of the research question, reviewing FEP literature and help-seeking, and the systematic literature search and screening process. To complete phases “translating the studies into one another” and “synthesizing translations”, Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) suggest “judgment calls” (p. 37) when considering if studies are comparable (reciprocal), oppositional (refutational) or are combined to form a “line of argument” (p. 38–40). Steps in determining and operationalizing this, however, are left open to interpretation (Campbell et al., Citation2011). Therefore, additional guidance was used, resulting in two levels of synthesis during this phase (France et al., Citation2019).

Level one-and-two synthesis

Level-one synthesis involved a systematic comparison and identification of concepts, metaphors and themes from one study to the other. To balance homogeneity and heterogeneity in the studies, “reciprocal translations” was grouped together, and refutational data were implemented to help consider and contextualize FEP experiences whilst demonstrating coherence. Ideas that were neither completely reciprocal nor refutational required a second level of synthesis: findings were re-read extensively to identify overarching concepts with the authors discussing and interpreting concepts and relationships between findings, themes and metaphors. Elements of a line-of-argument synthesis began to emerge, resulting in several critical discussions between authors to enhance reliability and representativeness of findings. Our findings did not yield enough data to generate a new theory, but rather a narrative about the process of FEP and help-seeking.

Findings

displays the five themes developed from the studies included in the analysis.

Table 5. Meta-ethnography themes: the facilitators and barriers to help-seeking for people with FEP.

Theme 1: initial certainty in interpreting experiences

Most participants described the beginnings of FEP as subtle changes happening to their thoughts, emotions and/or behaviours. Most did not seek help, assuming this was a result of a psychosocial stressor or was normal and transitory. There was only a small subset of participants across the studies that recognized the significance of some of the changes in experiences, especially if they had prior knowledge of FEP or mental health difficulties.

Subtheme 1.1: contextualizing experiences

As participants began noticing initial phenomenological changes of psychosis, it was common to attribute such changes to stress (Ferrara et al., Citation2021, p. 357; Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 97; Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 6; Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 36) sleep deprivation (Spikol & Murphy, Citation2019, p. 10; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 4; Van Beek et al., Citation2022, p. 3) substance misuse (Cabassa et al., Citation2018, p. 4; Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 421; Ferrara et al., Citation2021, p. 357; Melton et al., Citation2020, p. 1125; Spikol & Murphy, Citation2019, p. 24; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 4), or a physical health problem (Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 421). When a mental health problem was suspected, depression was most attributed (Bay et al., Citation2016, p. 73; Ferrara et al., Citation2021, p. 357; Jansen et al., Citation2015, p. 89; Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 4).

Subtheme 1.2: normalizing experiences

When changes were seen as unusual, such as being “split off from reality” (Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295), most reported not seeking help, believing it to be a passing, transitory phase, thereby normalizing it. Normalizing included assimilating these atypical aspects as something “perfectly normal” (Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 3), that it was “just the way [they] were” (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 97), or that it was a passing phase (Bay et al., Citation2016, p. 73; Jansen et al., Citation2015, p. 4; Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295). This participant illustrates normalization as follows:

The doctors asked [about voices], but I related it to my actual self. It was that close. (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 97)

When asked why help was not sought even after voice-hearing emerged, another participant suggested help-seeking as indicative of first thinking something was wrong:

Patient 18: I never thought of seeking help for voices … first I had to think whether it was normal or abnormal. (Van Beek et al., Citation2022, p. 5)

Some participants explained normalizing being due to social belongingness, “[wanting] to appear normal… not like someone who is weird and [hears] voices” (Jansen et al., Citation2015, p. 90).

Theme 2: growing uncertainty leading to different explanations

As FEP experiences intensified, two things appeared to occur: participants developed a “cloud of uncertainty” (Cabassa et al., Citation2018. P. 5), doubting initial interpretations of these experiences. “Explanatory models” (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 97) generally came after to accommodate any contradictory or confusing, ideas and beliefs.

Subtheme 2.1: growing uncertainty

Growing feelings of uncertainty were reported across studies. Participants reported difficulty articulating it:

I wasn’t feeling [like] myself, and things were strange… and it was hard to put into words because it was so complicated. (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 98)

Some participants explained uncertainty occurring when noticing they were “thinking differently about things … things that weren’t true” (Van Beek et al., Citation2022, p. 3). Both participants and authors suggested that perhaps participants initially understood these experiences as circumstantial and related to recent events, but it became increasingly difficult to continue contextualizing or normalizing them (Cabassa et al., Citation2018, p. 5; Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 98; Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 39; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 5). For example, one participant reported:

Is it the world that is sick or is it me? … When is it normal to just have a bad day, and when is it something mental? (Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 8)

The apparent difficulty in describing the uncertainty both presently and retrospectively suggests it may have delayed help-seeking at this stage.

Subtheme 2.2: developing alternative frameworks of understanding

Coupled with the feelings of uncertainty, most participants had a “need to figure out what’s going on” (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 98) and relied on frameworks to help make sense of these changes. Most frameworks appeared to be those that already fit with the participant’s cultural, religious and historical factors (Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 420; Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 40): the most common being a victim/persecuted and religious/cultural. Being persecuted or the victim of authority figures, the government, parents and friends was seen across Western studies:

I eventually, to make sense of my paranoid delusions, came up with a rationale that my head (mind) was the centre of a[n] on-line reality show that preyed on my deep sense of intuitiveness. (Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295)

For some, this facilitated help-seeking; believing they were being targeted led to contacting emergency services, which led to healthcare services (Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 9; Spikol & Murphy, Citation2019, p.15). The excerpt below explains it as such:

For Patient 2, who was convinced that she was being kept under surveillance but did not know by whom or for what exact purpose, it was not clear where to seek help. Thus, she asked her neighbours, colleagues, and even an accountant for help before finally calling her general practitioner, who suggested her to go the psychiatric emergency room. (Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 8)

With participants from Suriname (Van Beek et al., Citation2022) and Northern Malawi (Chilale et al., Citation2017) if participants believed there was a spiritual persecution, help-seeking through psychiatric services was limited as spiritual experiences “cannot be treated at the general practitioner” (Van Beek et al., Citation2022, p. 6). Help-seeking through psychiatric services at this stage would typically only be facilitated at the recommendation of a traditional healer and if deemed necessary (Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 7). As such, religious/spiritual and cultural frameworks, particularly among non-White participants, were characterized by the authors of those studies as being a barrier to help-seeking.

Theme 3: the role of significant others in help-seeking (or not)

As these frameworks become more established, participants’ behaviours, emotional expression and physical presentation changed, and it is usually at this point that significant others begin noticing changes and become more involved in facilitating or preventing help-seeking (Kamens et al., Citation2018, p. 312; Van Beek et al., Citation2022, p. 6).

Helpful family involvement included acknowledging the severity of the problems and encouraging participants to seek help (Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 5), as well as finding appropriate services (Hardy et al., Citation2020, p. 275) and “contacting schools, [and] accompanying [participants] at meetings” (Jansen et al., Citation2015, p. 87). Supportive friends were also reported to facilitate help-seeking, with some participants describing a stepwise process of disclosing to friends, then family and then seeking treatment (Jansen et al., Citation2014, p. 4, Citation2015, p. 88; Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 8). One participant described this process:

… because now I had explained the story to … yes, first to her in XXX and then to my best friend called XXX, and then to another in the same weekend that I explained my mother … so that’s how it started. (Jansen et al., Citation2015, p. 88)

In contrast, less helpful family involvement that delayed help-seeking included an absence of support and active listening, as well as misattributing or dismissing the psychosis after it already increased in severity (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 97; Melton et al., Citation2020, p. 1124; Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 9; Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 39; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 6). For example:

Patient 7 told her mother that she was hearing people who were not present talking to her. Her mother responded to her by saying that it was probably just ghosts, and she did not return to the issue or take any kind of action in relation to this. The patient described that after this, she did not seek help for a long time. (Nordgaard et al., Citation2020)

Some participants said they considered whether disclosing these experiences would be “making worse” another family member’s mental health-related difficulties and stress (Bogen-Johnston et al., Citation2019, p. 1312; Jansen et al., Citation2014, p. 4), but also if there was a history of mental health difficulties, families tended to recognize FEP faster (Bogen-Johnston et al., Citation2019, p. 1312).

Theme 4: the role of services in help-seeking (or not)

The perceived quality of mental health care was identified as important, with the likelihood of help-seeking from services depending on past interactions with services (Cabassa et al., Citation2018, p. 6; Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 423), cultural norms and expectations (Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 423; Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 41; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 7; Van Beek et al., Citation2022, p. 6). Service-Patient relationships appeared to influence if services were perceived as helpful, such as in how diagnoses were explained (Jansen et al., Citation2014, p. 4; Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295).

Participants characterized low-quality care as unclear information about treatment options and side effects (Cabassa et al., Citation2018, p. 6; Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 422), inappropriate referrals, which included being referred elsewhere without being given an address or location (Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 9), misdiagnoses (Bay et al., Citation2016, p. 74) and insensitive communications from healthcare professionals (Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 423; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 7). Further, police arrests (Ferrara et al., Citation2021, p. 359; Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 41), gender stereotypes (Ferrara et al., Citation2021, p. 359) and lack of communication and referrals between services and community groups after noticing deterioration in participants (Tanskanen et al., Citation2011), also impacted perceived quality of care.

There were also ethnic differences related to help-seeking. All ethnicities struggled in accessing care across all the studies, but Black, Asian and other ethnic minorities in majority White countries reported misapprehension in how they will be treated based on their ethnicity by healthcare providers and police (Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 4; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 5). On the other hand, White participants expressed concern in the quality of care they would receive, such as bed availability (Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 41).

Theme 5: the tipping point

If effective help-seeking was still not sought either through significant others, services, or self-referrals, what appeared to occur was the culmination of a crisis or a “tipping point”. Typically at this point help-seeking was seen as a final course of action.

The “tipping point” is characterized as exhausting all options from “jobs, friends … family doctor, psychotherapists, and naturopathy” (Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295), experiencing homelessness (Bogen-Johnston et al., Citation2019, p. 1311), and “[running out] of less threatening explanations for their predicament” (Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295) that may have previously delayed help-seeking. Participants’ families noticing physical deterioration also appeared to facilitate help-seeking, such as becoming “extremely thin” (Melton et al., Citation2020, p. 1125) or physically shaking (Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 8). Further, the “tipping point” appeared to lead to immediate (mostly emergency) help, accompanied with feelings of overwhelming dread and helplessness (Bogen-Johnston et al., Citation2019, p. 1311; Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 295) and suicidality (Kamens et al., Citation2018, p. 311; Tanskanen et al., Citation2011, p. 4).

Most authors of these studies described the “tipping point” as ending at service intervention. The participants, however, appeared to describe FEP experiences as an ongoing process, and it appears that, for at least some participants, there was reluctance in adopting a biomedical approach to explain their FEP. For example:

I came to know it was delusions. Every time I came to believe God was closer, I worry that I might have a delusion again. It’s hard to believe in God the right way, without the delusion. Little by little my faith became destroyed … I don’t have my self. (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 98)

It was acknowledged that, where healthcare providers imposed a medical framework over participants’ explanatory frameworks, this could have inadvertently undermined their faith, sense of self and ability to connect to their cultural, social and familial systems (Chilale et al., Citation2017, p. 423; Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 98; Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 296). Some participants reported creating a “blend [of] their earlier interpretive frames (e.g. spirituality and limit identities) with the notion of illness” (Macnaughton et al., Citation2015, p. 296), while others expressed wanting to “[find] meaning in the illness experience” (Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 98; Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 10). Across the studies it showed that some healthcare providers supported individuals in developing their own understanding of FEP, while others emphasized a medical interpretation over participants’ beliefs, values and interpretations (Cabassa et al., Citation2018; Judge et al., Citation2008, p. 98; Nordgaard et al., Citation2020, p. 10; Singh et al., Citation2013, p. 41; Tansakenen et al., Citation2011, p. 7).

Discussion

The aim of the meta-ethnography was to understand the facilitators and barriers of help-seeking from the perspectives of participants who have experienced FEP. Our findings, based on a subset of participants who have experienced FEP and accessed help through services, suggest a chronological process in the noticing, sense-making and help-seeking experiences associated with FEP. Help-seeking appeared dependent upon relational, cultural, ethnic and systemic dynamics within the familial and social network.

Clinical and research implications

Delaying help-seeking due to attributing to other experiences, contextualizing and/or normalizing

Delayed help-seeking due to attributing experiences to other psychosocial and emotional stressors was a common occurrence among participants. For future research aiming to prevent or decrease the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), it may be helpful to clarify the relationship between changes in mood, stressors and FEP across services during the process of referrals, interventions and evaluations. Research should also include family and community perspectives, including liaison with non-statutory community services, charities and networks to help identify and include potential alternative pathways to help-seeking.

Facilitating and delaying help-seeking from services due to explanatory frameworks

The relationship between explanatory frameworks and help-seeking in our findings was unclear, indicating that these can either facilitate or delay help-seeking. The current literature shows contradictory evidence on whether explanatory frameworks are helpful (Pangaribuan et al., Citation2021) or not (Talbott, Citation2008). It does appear to occur after growing feelings of uncertainty, which may indicate it is a way for participants to cope and make sense of their experiences. Contradictory evidences about explanatory frameworks may continue to be seen in psychosis research, therefore future research could benefit from exploring different aspects to explanatory frameworks, such as its influences from a person’s ethnicity, culture, and beliefs and its impact rather than only if it facilitates help-seeking or not. The role of explanatory models and their compatibility with services’ own views of psychosis would appear to be an important area to understand help seeking and subsequent engagement with services.

Relationships and help-seeking

Supportive involvement from services and significant others appeared to facilitate help-seeking, while critical and stigmatizing involvement led to delays. An interesting finding in our results was peer support and how it facilitated help-seeking for participants. More research attention should be paid to how, where possible, peer support for psychosis may be helpful alongside family support. It is also recommended that future research explore how organizational and cultural changes can be made in a realistic way for helpful involvement to happen consistently. This can include exploring recovery styles for psychosis (Davidson, Citation2011) that integrate the person’s beliefs, including spirituality and culture.

Evaluating the review

The epistemological positions of the primary studies were often unclear, potentially losing valuable information on authors’ influences, biases, and reporting of data. Most studies under review did not provide definitions of FEP, psychosis and help-seeking, which limits the interpretability of the studies. Further, as the articles under review only had participants that sought help through mental health services, we cannot make generalizations that everyone who experiences FEP or psychosis eventually seeks help through mental health services or follows the same help-seeking processes. If there are people who have distressing anomalous experiences and successfully sought help elsewhere, it is unlikely that they would be represented in this review. It was difficult to extract meaningful information about ethnic and individual differences across studies, unless this was already an aim of the authors. Therefore, it was not possible to sufficiently extrapolate individual differences based on gender or culture, despite both being identified as influential to help-seeking. There was also a lack of clarity and comprehensiveness around the reporting of methods and analyses. As such, rigor and credibility were in some cases difficult to appraise, highlighting the need for clearer description in reporting.

A strength of this meta-ethnography was that it had a clear approach to investigating the research question at hand and provided definitions for the psychosis concepts that were going to be explored, along with a more general definition of help-seeking that allows for multiple approaches to obtaining help rather than limiting its definition to only one path (e.g. mental health services). It also implemented a rigorous research design and methodology, while the analyses explored both complementary and contradictory data, with the aim to add to the overall “richness” of the synthesis whilst still being compatible with the research question. The primary author used a reflective diary and associated reflective discussions with the second author who is from a different cultural background and gender to help in managing the impact of personal biases and influences.

Conclusions

This meta-ethnography aimed to explore personal accounts of the facilitators and barriers of help-seeking for FEP. The findings focused on those who had sought services from mental health services and suggested a chronological process of participants making sense of the FEP, including attempts to assimilate the experiences of psychosis into existing meaning-making frameworks.

Disclosure statement

Both authors work in mental health services, which includes working with some patients who have psychosis.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albert, N., & Weibell, M. A. (2019). The outcome of early intervention in first episode psychosis. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(5–6), 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2019.1643703

- Booth, A. (2016). Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: A structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0249-x

- Bramer, W. M., Rethlefsen, M. L., Kleijnen, J., & Franco, O. H. (2017). Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Systematic Reviews, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0644-y

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Campbell, R., Pound, P., Morgan, M., Daker-White, G., Britten, N., Pill, R., Yardley, L., Pope, C., & Donovan, J. (2011). Evaluating meta-ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 15(43). https://doi.org/10.3310/hta15430

- Davidson, L. (2011). Recovery from psychosis: What’s love got to do with it? Psychosis, 3(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2010.545431

- France, E. F., Uny, I., Ring, N., Turley, R. L., Maxwell, M., Duncan, E. A., Jepson, R. G., Roberts, R. J., & Noyes, J. (2019). A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0670-7

- Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Duquesne.

- Griffiths, R., Mansell, W., Edge, D., & Tai, S. (2018). Sources of distress in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review and qualitative Metasynthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 29(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318790544

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA publications and communications board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000151

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

- Martin, J., Sugarman, J., & Slaney, K. L. (2015). Phenomenology: Methods, historical development, and applications in psychology. In The Wiley handbook of theoretical and philosophical psychology: Methods, approaches, and new directions for social sciences. John Wiley & Sons.

- Moher, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- NICE. (2022). Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (3rd ed.). https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/resources/methods-for-the-development-of-nice-public-health-guidance-third-edition-pdf-2007967445701

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985000

- Pangaribuan, S. M., Lin, Y., Lin, M., & Chang, H. (2021). Mediating effects of coping strategies on the relationship between mental health and quality of life among Indonesian female migrant workers in Taiwan. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 33(2), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/10436596211057289

- Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., Wilson, C. J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Australian E-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 4(3), 218–251. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.3.218

- Talbott, J. (2008). Toward an integration of spirituality and religiousness into the psychosocial dimension of schizophrenia. Yearbook of Psychiatry and Applied Mental Health, 2008, 140–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0084-3970(08)70723-0

- Toye, F., Seers, K., Allcock, N., Briggs, M., Carr, E., Andrews, J., & Barker, K. (2013). ‘Trying to pin down jelly’ - Exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(46). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-46.

References of studies under review

- Bay, N., Bjørnestad, J., Johannessen, J. O., Larsen, T. K., & Joa, I. (2016). Obstacles to care in first-episode psychosis patients with a long duration of untreated psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 10(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12152

- Bogen-Johnston, L., De Visser, R., Strauss, C., Berry, K., & Hayward, M. (2019). “That little doorway where I could suddenly start shouting out”: Barriers and enablers to the disclosure of distressing voices. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(10), 1307–1317. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317745965

- Cabassa, L. J., Piscitelli, S., Haselden, M., Lee, R. J., Essock, S. M., & Dixon, L. B. (2018). Understanding pathways to care of individuals entering a specialized early intervention service for first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 69(6), 648–656. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700018

- Chilale, H. K., Silungwe, N. D., Gondwe, S., & Masulani-Mwale, C. (2017). Clients and carers perception of mental illness and factors that influence help-seeking: Where they go first and why. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63(5), 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017709848

- Ferrara, M., Guloksuz, S., Mathis, W. S., Li, F., Lin, I., Syed, S., Gallagher, K., Shah, J., Kline, E., Tek, C., Keshavan, M., & Srihari, V. H. (2021). First help-seeking attempt before and after psychosis onset: Measures of delay and aversive pathways to care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(8), 1359–1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02090-0

- Hardy, K. V., Dickens, C. E., Roach, E. L., Harrison, V., Desai, A., Flynn, L., Noordsy, D. L., Dauberman, J., & Adelsheim, S. (2020). Lived experience perspectives on reducing the duration of untreated psychosis: The impact of stigma on accessing treatment. Psychosis, 12(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2020.1754890

- Jansen, J. E., Pedersen, M. B., Hastrup, L. H., Haahr, U. H., & Simonsen, E. (2015). Important first encounter: Service user experience of pathways to care and early detection in first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12294

- Jansen, J. E., Wøldike, P. M., Haahr, U. H., & Simonsen, E. (2014). Service user perspectives on the experience of illness and pathway to care in first-episode psychosis: A qualitative study within the TOP project. Psychiatric Quarterly, 86(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-014-9332-4

- Judge, A. M., Estroff, S. E., Perkins, D. O., & Penn, D. L. (2008). Recognizing and responding to early psychosis: A qualitative analysis of individual narratives. Psychiatric Services, 59(1), 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.96

- Kamens, S. R., Davidson, L., Hyun, E., Jones, N., Morawski, J. G., Kurtz, M. M., Pollard, J., Ian van Schalkwyk, G., & Srihari, V. (2018). The duration of untreated psychosis: A phenomenological study. Psychosis, 10(4), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2018.1524924

- Macnaughton, E., Sheps, S., Frankish, J., & Irwin, D. (2015). Understanding the development of narrative insight in early psychosis: A qualitative approach. Psychosis, 7(4), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2014.980306

- Melton, R., Blajeski, S., & Glasser, D. (2020). Understanding individual and family experiences associated with DUP: Lessons from the early assessment and support alliance (EASA) program in Oregon, USA. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(6), 1121–1127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00599-3

- Mendeley. (2023). Mendeley - Reference Management SoftwareMendeley. https://www.mendeley.com/

- Nordgaard, J., Nilsson, L. S., Gulstad, K., & Buch-Pedersen, M. (2020). The paradox of help-seeking behaviour in psychosis. Psychiatric Quarterly, 92(2), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09833-3

- Singh, S., Islam, Z., Brown, L., Gajwani, R., Jasani, R., Rabiee, F., & Parsons, H. (2013). Ethnicity, detention and early intervention: Reducing inequalities and improving outcomes for black and minority ethnic patients: The ENRICH programme, a mixed-methods study. Programme Grants for Applied Research, 1(3), 1–168. https://doi.org/10.3310/pgfar01030

- Spikol, A., & Murphy, J. (2019). ‘Something wasn’t quite right’: A novel phenomenological analysis of internet discussion posts detailing initial awareness of psychosis. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, (aop). https://doi.org/10.3371/csrp.spjm.032819

- Tanskanen, S., Morant, N., Hinton, M., Lloyd-Evans, B., Crosby, M., Killaspy, H., Raine, R., Pilling, S., & Johnson, S. (2011). Service user and carer experiences of seeking help for a first episode of psychosis: A UK qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-11-157

- Van Beek, A., De Zeeuw, J., De Leeuw, M., Poplawska, M., Kerkvliet, L., Dwarkasing, R., Nanda, R., & Veling, W. (2022). Duration of untreated psychosis and pathways to care in Suriname: A qualitative study among patients, relatives and general practitioners. British Medical Journal Open, 12(2), e050731. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050731

- Van Nes, F., Abma, T., Jonsson, H., & Deeg, D. (2010). Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing, 7(4), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y