ABSTRACT

Introduction

Informed consent is the process whereby individuals make decisions about their medical care. Information provision, presumption of capability and absence of coercion are three fundamental assumptions required to provide informed consent. Informed consent may be complex to achieve in the context of antipsychotic prescribing. This systematic review aimed to explore challenges relating to informed consent processes in antipsychotic prescribing in the UK.

Method

This was a systematic review of the literature relating to informed consent in antipsychotic prescribing in community settings. Data were analysed using Framework analysis.

Results

Twenty-eight articles were included. Information provision has been perceived as lacking for a long time. Capacity has often not been assumed and loss of capacity has sometimes been viewed as permanent. Power imbalances associated with prescriber status and legal framework surrounding the Mental Health Act can blur lines between coercion and persuasion.

Discussion

Challenges relating to process of informed consent in antipsychotic prescribing have persisted throughout the last few decades. People prescribed antipsychotics need to be made aware of their effects in line with current research. Further research is required to develop models for best practices for informed consent.

Introduction

In accordance with international human rights law, individuals in the UK must provide their consent to any medical care, tests or treatment (NHS, Citation2022a). Informed consent is the process whereby individuals make decisions about their medical care based on adequate information about the “purpose, nature, consequences and risks of an intervention and has freely consented to it” (Gefenas, Citation2012). Informed consent has three key components which must be met: Information provision, presumption of capability and the absence of coercion (Pozón, Citation2015). According to guidance set out by the NHS “the person must be given all of the information about what the treatment involves, including the benefits and risks, whether there are reasonable alternatives treatment, and what will happen if the treatment does not go ahead” (NHS, Citation2022a). Genuine informed consent may be more complex to achieve in mental health settings than physical health and, more specifically, in antipsychotic prescribing.

Mental health diagnoses may involve more uncertainty than physical health and are arguably more subjective (Pies, Citation2007; Weir, Citation2012). The stigma of diagnosis and treatment, and how this affects perceptions of capability, still persist in clinical practice, the media and from families and support networks of people diagnosed with Severe Mental Illness (SMI) (Huggett et al., Citation2018; Rössler, Citation2016). Concerns about people diagnosed with SMI making “unwise” choices also persist, which can lead to paternalistic practices, undermining individuals’ ability to make informed choices about their health (e.g. Cave, Citation2017; Ventura et al., Citation2021).

Antipsychotics are regarded by some to be an effective method for managing symptoms in some people diagnosed with SMI, including schizophrenia and other psychotic diagnoses, and are often prescribed long-term (Keepers et al., Citation2020; NICE, Citation2014; Takeuchi et al., Citation2012). However, over time our understanding of the limitations and possible risks of antipsychotics such as Diabetes, Tardive Dyskinesia, Heart Disease, sexual dysfunction, emotional blunting (Buckley & Sanders, Citation2000, Rajkumar et al., Citation2017; Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2023; Thompson et al., Citation2020) has increased, as has understanding of withdrawal effects (Read, Citation2022). Some individuals have reported their experiences with antipsychotics as “harmful” (Katz et al., Citation2019) and some studies suggest that service users perceive that they were not provided with information about antipsychotics before being prescribed them (e.g. Read & Sacia, Citation2020; Waterreus et al., Citation2012). This raises questions about how and what information is shared.

While informed consent has been frequently discussed within the literature, discussion of consent in the context of antipsychotic prescribing has been fairly sparse. It is important to assess to what degree the three fundamentals of informed consent can be met currently and identify barriers to achieving them the prescription of antipsychotics. This systematic review aims to highlight challenges around the implementation of the three fundamentals over time and the current environment for informed consent in this context.

Method

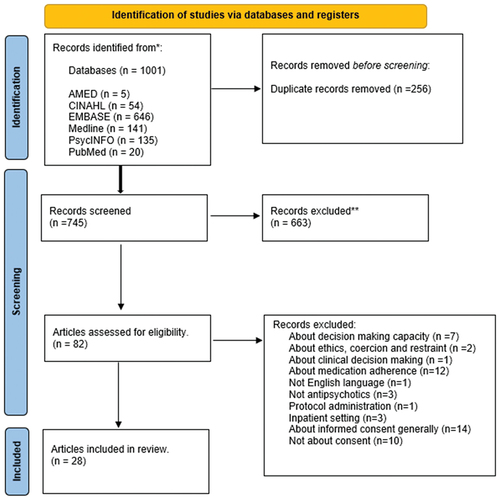

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) guidelines (Page et al., Citation2021) (). Protocol available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021244698 Registration number CRD42021244698.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Diagnosis of schizophrenia/psychosis (can include co-morbid diagnoses with conditions e.g. depression, bipolar)

About informed consent in context of antipsychotic prescribing

About information giving for informed consent

English language

Qualitative and quantitative research

Case studies

Service user and clinician testimonials/editorials

Treated in the community

Related to the ethical, legal and practical aspects of informed consent

Exclusion criteria

Aged < 18 years

Medication other than antipsychotics

Informed consent as part of research participation

Inpatient

About defining capacity and capability, without specific focus on the role of capacity/capability in the context of obtaining informed consent

Search

The authors included all types of articles, including empirical research, case studies, editorials and opinion pieces. No date parameters were set.

Repeated searches of the following electronic databases were conducted from April 2021 until August 2023 AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO and PubMed. The following search terms were used: ((antipsychotic* OR neuroleptic* OR anti-psychotic*) AND (“consent form” OR “consent” OR “informed consent”) AND (schizophren* OR psychosis)). Additional articles were also identified through back and forward citation searching of full-text articles included through screening.

Study selection

Included empirical articles were quality assessed by both reviewers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Nha Hong et al., Citation2018). Inter-rater reliability was good (k = >0.7). Most articles were found to be of reasonable quality, none were considered to be low quality. The authors note articles related to informed consent in inpatient settings were excluded from this review as it is acknowledged that there are nuances in some of the considerations for processes for informed consent in inpatient as compared to community environments, which this review would not have the capacity to address. For example, fluctuations in capacity and ability to enforce treatment through methods such as physical restraint.

Data extraction, analysis and interpretation

Information relating to informed consent was extracted and imported into Nvivo v12. Data was analysed using Framework analysis (Brunton et al., Citation2020). The predetermined components of the framework were the three fundamentals of informed consent: Information giving, capability of the individual and absence of coercion. A sample of five papers, chosen at random, were coded line-by-line by both reviewers independently, who then met to discuss their findings and queries and finalise the framework. The remaining papers were divided equally between the two reviewers, who met at regular intervals to discuss findings and queries.

Both reviewers endeavoured to enhance the validity of the analysis through collaborative and reflexive practices. The philosophical and theoretical positions of both reviewers were discussed and questioned during the analytic process. The level of detail involved in the coding process and the regular discussions about the analysis helped ensure that there was strong consensus between the reviewers about the conceptualisation of the themes and the relationships of those themes to the data.

Results

Twenty-eight articles were included in the analysis. These included 13 empirical research papers, 2 literature reviews, 11 discussion/editorial pieces, 1 case report and 1 clinical audit. The articles were from ten countries (see ).

Table 1. Study/article characteristics.

Information giving

Several studies, including Higgins et al. (Citation2006), Laugharne and Brown (Citation1998) and Masand et al. (Citation2002) reported reluctance among clinicians to discuss risks of antipsychotics and inform service users of the reasons for prescription or alternatives. Additionally, Bowler et al. (Citation2000) and Harris et al. (Citation2002) found that information provision was often not documented. Schachter et al. (Citation1999) reported that most clinicians in their sample provided information to service users, though the documentation of this was lacking. Interestingly, many of the psychiatrists in the sample felt that documentation of informed consent processes was important for surgical procedures, but less so for antipsychotic prescribing.

Linden and Chaskel (Citation1981) found that 40% of service users could not name side-effects without prompting but were knowledgeable of therapeutic effects when asked. Eastwood and Pugh (Citation1997) reported that most service users were “well informed” about their antipsychotics, with most knowing their dose, frequency and reasons for prescription.

A limited pool of research looked at service users’ views on information provision. Goldbeck et al. (Citation1999) found that around half of service users felt they received adequate information about their medication, with information about side-effect being most desired. Noor et al. (Citation2019) found that lack of information was cited as a reason for non-adherence to treatment in 6% of cases. This was a small proportion compared with those who were reported as being non-adherent due to lack of insight (37%). It is of note that this categorisation of “lack of insight” came from the researchers who made this interpretation based on responses of patients to statements such as “I don’t need medication as I don’t have any illness”. Read and Williams (Citation2019) reported that 69.6% of respondents to their survey felt uninformed about possible side-effects of antipsychotics, and these people generally reported more adverse effects.

There is a persistent lack of clarity regarding what constitutes “adequate” information and has been a point of ongoing debate among clinicians, service users and the legal system. For instance, in the legal literature, terms such as “full” or “reasonable” have been used, but determining their practical meaning remains challenging (Davis et al., Citation1988). Freishtat and Einhorn (Citation1981) have pointed out the ambiguity surrounding whether “appropriate” information means presenting comprehensive information or whether a more targeted approach would be sufficient. At the time of Kleinman et al’s works, there was still no clear consensus on what a service user would be considered “informed” (Kleinman et al., Citation1996, Citation1989). However, Brabbins et al. (Citation1996) suggested that development of a proforma that recorded the elements required to facilitate informed consent could standardise the level of information provided and create a record of the information given.

From the perspective of service users, the adequacy of information provided may need to extend beyond the quantity of the information and consider how much information they actually want to receive (Pozón, Citation2015). Goldbeck et al. (Citation1999) had previously found that service users often requested more information, suggesting perceived gaps in the information that they were provided. Moreover, Laugharne et al. (Citation2004) and Goldfarb et al. (Citation2012) indicated disparities between the information desired by service users and what they were actually provided, underscoring differences in their expectations for information provision.

Various articles have emphasised the importance of discussing both the risks and benefits of antipsychotics (Laugharne et al., Citation2004). However, there is ongoing discussion about what should be disclosed. One risk specific to antipsychotics often subject of discussion is Tardive Dyskinesia (TD). This is of particular concern for long-term users of antipsychotics, given its devastating effects and irreversibility (Kleinman et al., Citation1989; Mcmurray, Citation2002; Schachter & Kleinman, Citation2004). Harris et al. (Citation2002) queried whether service users should be informed of infrequent side-effects, particularly more serious ones such as Tardive Dyskinesia (TD) or fatal ones such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome. However, also around this time, Mcmurray (Citation2002) argued that service users “must be told about [Tardive Dyskinesia] if they are to make informed choices regarding long-term treatment with an antipsychotic medication”.

Related to this point is the concept of Therapeutic Privilege. This term refers to the deliberate omission of information by clinicians when they perceive that provision of information could cause anxiety or hinder adherence to treatments, which, clinicians believe may cause more harm than if medications were taken as prescribed (Chaplin et al., Citation2007; Goldbeck et al., Citation1999; Higgins et al., Citation2006). Clinicians may also withhold information if they believe that an individual lacks capacity to make wise decisions (Mcmurray, Citation2002). These practices raise ethical questions about striking the balance between supporting autonomy and clinician’s duty of care (see Capacity of the individual, below).

The issue of information provision becomes more complex when service users abdicate their rights to receive information and make decisions about their care, preferring clinicians to make decisions on their behalf (Mcmurray, Citation2002). However, even in these cases, clinicians have a duty to provide basic information about proposed treatments. Balancing these principles can be challenging (Harris et al., Citation2002). Due to limited literature on this point of discussion, perspectives on this issue remain unclear.

Capability of the individual

The concept of capacity has been described to mean that the “patient has sufficient mental abilities and the opportunity to ask questions” (Goldfarb et al., Citation2012, citing Applebaum, 2006). Historically, some have argued that if the person is unable to communicate their decision, they are also incompetent to make a decision. However, Brabbins et al. (Citation1996) suggest that “passive approval” should not be considered genuine informed consent.

There has sometimes been an assumption from clinicians that having a mental health diagnosis means that loss of capacity may be permanent (Goldfarb et al., Citation2012; Pozón, Citation2015; Tryer et al., Citation1994). According to some research, diagnoses such as schizophrenia/psychosis are associated with cognitive deficits related to learning and memory which may impact individuals’ ability to make decisions, and that capacity may be further hindered by the ongoing effects of antipsychotics, including brain fog and sedative effects (Chaplin & Timehin, Citation2002; Goldfarb et al., Citation2012; Kleinman et al., Citation1989). Kitamura (Citation2005) suggested that experiences of anxiety may mean that even patients considered “competent” cannot think rationally.

However, some studies did not support this notion. Cancro et al. (Citation1981) and Brabbins et al. (Citation1996) suggested that the arguments outlined for presuming of lack of capacity in people with SMI “are not compelling”. Both indicated that informed consent should always be sought, in all but the most exceptional of circumstances. Paternalism has persisted in places, with continuation of the “doctor knows best” approach (Usher Rn et al., Citation1998), though to what extent this is still true is unclear due to the lack of recent literature.

Brabbins et al. (Citation1996) and Tryer (Citation2000) suggested that people are not necessarily incompetent or lacking capacity just because their decisions are not aligned with clinicians’ recommendations. In 1998 the United Kingdom Central Council (UKCC), a government organisation that ensures that nurses, midwives and health visitors provide high standards of care for the public (cited in Harris et al., Citation2002), indicated that people have the right to be considered competent until proven otherwise. However, despite the presence of legal definitions of competence, such as that outlined by the UKCC, few articles included in this review referred to such legal definitions.

In a survey of 427 psychiatrists by Harris et al. (Citation2002), all but one felt that “competent patients should be informed about the benefits and risks of antipsychotic medication” and 42% felt that acutely unwell patients can participate in the consent process. Of note, the study did not define “competent” any further and, again, more recent literature surrounding this issue is lacking.

Absence of coercion

Literature has indicated that persuasion and coercion can be difficult to delineate. Usher Rn et al. (Citation1998) and Laugharne et al. (Citation2004) argued that situations where people feel they have no choice but to comply with their doctor’s wishes are coercive rather than persuasive.

The Mental Health Act (MHA) is “the main piece of legislation [in the UK] that covers the assessment, treatment and rights of people with a mental health disorder” (NHS, Citation2022b). Power imbalances are an issue in the context of the MHA, where the perception of “duress” may persist, even if a genuine choice was given (Ingelfinger, Citation1972 cited in Brabbins et al., Citation1996). In Brabbins et al. (Citation1996) people frequently referred to threatened or implicit pressure from clinicians and relatives to take their medication, citing that they may be sectioned or be put on depot if they did not comply. In the UK, “sectioning” refers to the act of being admitted to hospital under the MHA, regardless of whether the individual agrees to this, because they are potentially at risk to harm of themselves of others and are unwilling or unwilling to agree to hospitalisation (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2018). Brabbins et al. (Citation1996) argued that, in the community, informing someone that relapse is possible without medication does not qualify as “duress”; however, pointing out that lack of adherence may lead to a referral to MHA assessment would cross this line. It is therefore crucial that the person is told that they are able to disagree with their clinician and be made aware that their refusal or disagreement does not lead to sanctions later on (Laugharne & Brown, Citation1998). Not taking medication may however lead to an inpatient admission, which is tricky to convey in a non-coercive way (Chaplin et al., Citation2007).

Another consideration in the issue of coercion is the way that information is presented. If sufficient information is given, but the positives are highlighted much more than the negatives, does this qualify as a means of persuasion or influence? Higgins et al. (Citation2006) found that benefits of medication were frequently highlighted more than risks of medication in consultation with nurses: benefits of being able to avoid an inpatient admission versus the risk of sexual dysfunction were observed in consultations with patients, advocating clearly for the use of medication and insinuating that lack of medication would be a direct cause for an inpatient admission. “I would say, well the down side of this is, if you become active [sexually], then you become very unwell, and your stays in hospital are going to be longer and your stretches at home are going to be shorter, so like you have to lay out the pros and cons, whether you think it is worth it to be sexually active and to be unwell all your life, so they would have to make that decision (19 F)” (p. 442, Higgins et al., Citation2006).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to explore challenges of informed consent processes in antipsychotic prescribing.

The review revealed that across several decades there has been little empirical research in this area. Much of the literature identified was opinion pieces and editorials. In particular, there were few RCTs examining informed consent processes and outcomes. Much of the literature is written from the perspective of clinicians and their clinical practices. Qualitative approaches exploring lived experience are still relatively new, and few studies examined informed consent from the perspective of those being prescribed antipsychotics. Improvements in this area can only be achieved by conducting more research from these perspectives.

Results showed that the same issues have been discussed over 5 decades and it appears that achieving informed consent in this context remains difficult. Information provision has been, and still is, often perceived as lacking. Informed consent should include information about alternative treatment options, however findings from this review indicate that this does not always occur (Higgins et al., Citation2006; Laugharne & Brown, Citation1998; Masand et al., Citation2002). A partial explanation for this relates to what information is considered “adequate” for a person to make informed decisions. However, this was mostly discussed from the perspective of clinicians and difficulties around how they decide what and how much information is enough (e.g. Freishtat & Einhorn, Citation1981; Kleinman et al., Citation1996, Citation1989). A focal point of this issue in several cases was the concept of therapeutic privilege, with clinicians being viewed as the gatekeepers of information, providing information based on what they felt was appropriate and that would lead to the best rates of “adherence” which, they considered to be in the best interests of the service users.

In particular, there was a focus on the debate around providing information about the risks of developing TD; a serious adverse effect that can have a profound impact on quality of life (Kleinman et al., Citation1989; Mcmurray, Citation2002). The review indicated that historically service users were not informed of the risks of developing TD. The extent to which these paternalistic practices continue, is unclear given the lack of recent literature on this topic. To add to this complexity, as Mcmurray (Citation2002) stated, there is some ambiguity surrounding the extent to which an individual can abdicate responsibility and how much information should be provided. This raises concerns about enabling peoples’ enactment of their autonomy, as this indicates a lack of information provision regarding the possible risks/benefits of antipsychotics, thus the fundamental of information provision is not met.

Withholding information can be seen as paternalistic, regardless of the desires of the service user for certain information, as the healthcare professional then makes decisions for the individual. Wide adoption of the person-centred philosophy should have bought about changes to patient care, preventing these paternalistic practices (WHO, Citation2015). Moreover, findings indicated that services users wanted information about the risks and benefits of antipsychotics, though literature exploring the issue from this perspective was, in general, fairly sparse. It is only more recently that this has been brought into focus through the implementation of qualitative studies.

A contemporary issue, now more central to the discussion of antipsychotic prescribing antipsychotics, is discontinuation. Withdrawal from antipsychotics has historically been discouraged by clinicians. However, in light of severe side-effects and lack of understanding about why these medications are being prescribed, as outlined by Roe et al. (Citation2009), Salomon et al. (Citation2014) and (Rofail et al., Citation2009), it is perhaps unsurprising that, when asked, service users report wishing to discontinue. Within the last decade, this question has been foregrounded and services users are being asked in more detail about their experiences and desires for treatment, as in Read (Citation2022). Questions are now, finally, being asked about how to support this desire, rather than allow therapeutic privilege and coercive, stigmatising ideas about capacity to prevent this from occurring. However, as long as the issues outlined in the review persist, the ways in which to support service users in achieving this are limited.

This review has also illustrated the complexity of capacity with regards to decision making. Diagnostic overshadowing can lead to assumptions of capacity issues when the person, in fact, has capacity. For example, at times, “unwise decisions” of persons with SMI have been conflated with “lack of insight” rather than being treated as justified concerns around the risks/benefits of medication (Harris et al., Citation2002). Despite the apparent move towards more patient-centred approaches to healthcare, these assumptions have also been reflected in more recent qualitative studies, such as Martínez-Hernáez et al. (Citation2020) who found that some participants in their study reported feeling that clinicians assumed that symptoms are permanent. Until such attitudes really do begin to evolve, little is likely to change as regards attitudes towards capacity and capability.

Tools used to support informed consent processes in physical health settings, such as advanced directives and the documentation of informed consent processes are rarely discussed in relation to treatment with antipsychotics, as the findings from this review showed (Bowler et al., Citation2000; Harris et al., Citation2002). Furthermore, there was a lack of consistency as regards which domains of healthcare informed consent processes should document (Schachter et al., Citation1999). It can be argued however, that documenting the informed consent process could support forward planning and care, ensuring that service users are really given the information they need, rather than the information that clinicians choose to provide. As Brabbins et al. (Citation1996) proposed, checklists to ensure that all “relevant” information is provided and that the service user has been afforded the opportunity to discuss what information they feel they need, which may differ from what the clinician thinks they need, may provide such support.

More recently, Martínez-Hernáez et al. (Citation2020) found that some service users were in favour of the use of advanced directives. Advanced directives are advanced care plans which give instructions on how health care professionals should proceed in the event that an individual is unable to give their consent to procedures and treatments (NHS, Citation2023). This is another possible way of circumventing issues around coercion and capacity until attitudes truly begin to shift. Advanced directives are often used in physical health care, particularly in palliative care settings and care planning for older adults but their use is limited in Mental Health settings. Such systems could be better utilised to safeguard service users in the event that they experience episodes which lead to reduced capacity.

Literature relating to coercion indicated that people may agree to medication because they believe that refusal may lead to them being sectioned under the MHA (Laugharne & Brown, Citation1998; Laugharne et al., Citation2004; Usher Rn et al., Citation1998). Pressure to comply may come from the person’s family, friends or clinicians. There is a fine balance to strike about sharing the risks/benefits of medication in a non-pressured way so that people may make decisions voluntarily and without duress. However, given the structure of the MHA, and inherent power imbalances between clinicians and service users, this may be difficult to achieve.

Strengths

This review benefits from broad search terms, allowing the inclusion of a variety of articles. Including all study designs led to a holistic overview of the topic which could give important insights into understanding this problem further. The inclusive time range also allows a longitudinal perspective, to understand how this topic has been explored over time. Included empirical papers were quality assessed using the MMAT.

Limitations

Despite broad search terms, good quality studies assessing service user perspectives on informed consent and studies comparing different means of receiving informed consent are lacking. However, it is acknowledged that ethical issues are, by nature, difficult to assess in RCTs or other forms of gold standard evidence. A significant number of studies were conducted prior to 2000; therefore, studies on informed consent cannot have taken into account recent developments in this field. Another limitation of this review was the decision to focus on community prescribing. There are different challenges faced in terms of informed consent within community versus inpatient settings. This may have implications for the conclusions drawn in this review. However, the authors felt that issues surrounding informed consent in inpatient settings were best outlined in a separate piece of work, where there is the scope with which to discuss the nuances of informed consent in this setting.

Conclusions

To obtain informed consent, three fundamentals need to be met: adequate information must be provided, capacity and capability must be assumed, and individuals should not be coerced into making decisions. In the context of antipsychotic prescribing, this review has shown that the same issues relating to these three fundamentals persist. Moreover, there is a lack of recent literature moving this discussion forward or instigating changes in practice. Given recent advances in our understanding of antipsychotics, and a shift towards person-centred approaches to care, which value autonomy, it is important to re-consider these issues and identify ways to ensure that the three fundamentals are met.

Based on the findings from this systematic review, the authors suggest further work to develop a model showing how information could be shared with people being prescribed antipsychotics, especially in the light of increased knowledge of the effects of these medications, and to bring informed consent process more into step with the processes undertaken in physical health settings. Whilst some efforts are being made to develop tools for decision making as regards the continuation or discontinuation of antipsychotics, such as the Encounter Decision Aid by Zisman-Ilani et al. (Citation2018), we would recommend that tools be created for those being prescribed antipsychotics for the first time. Within the development of these tools, the perspectives of those prescribed antipsychotics would be incorporated, asking for their opinions and input into obtaining informed consent.

Furthermore, to achieve genuine informed consent, further work is needed to address stigma, and assumptions around capacity and coercion in prescribing practices for both clinicians, family member and the public. Further research into developing educational aids for clinicians and the public is needed, again incorporating the views and experiences of those who have been prescribed antipsychotics within this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bowler, N., Moss, S., Winston, M., & Coleman, M. (2000). An audit of psychiatric case notes in relation to antipsychotic medication and information giving the psychoses. British Journal of Clinical Governance, 5(4), 212–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/14664100010361773

- Brabbins, C., Butler, J., & Bentall, R. (1996). Consent to neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia: Clinical ethical and legal issues. British Journal of Psychiatry, 168(5), 540–544. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.168.5.540

- Brunton, G., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2020). Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(3), 316–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1399

- Buckley, N. A., & Sanders, P. (2000). Cardiovascular adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs. Drug Safety, 23(3), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200023030-00004

- Cancro, R., Davis, J. M., Klawans, H., & Tancredi, L. (1981). Medical and legal implications of side effects from neuroleptic drugs. A round table discussion. The Journal ofClinical Psychiatry, 42(2), 78–82.

- Cave, E. (2017). Protecting patients from their bad decisions: Rebalancing rights, relationships, and risk. Medical Law Review, 25(4), 527–553. https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fww046

- Chaplin, R., Lelliott, P., Quirk, A., & Seale, C. (2007). Negotiating styles adopted by consultant psychiatrists when prescribing antipsychotics. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.106.002709

- Chaplin, R., & Timehin, C. (2002). Informing patients about tardive dyskinesia: Four-year follow up of a trial of patient education. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.00979.x

- Davis, J.M., & Comaty, J. (1988). Legal aspects of tardive dyskinesia. L’Encephale, 14, 257–261.

- Eastwood, N., & Pugh, R. (1997). Long-term medication in depot clinics and patients’ rights: An issue for assertive outreach. Psychiatric Bulletin, 21, 273–276. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.21.5.273

- Freishtat, H. W., & Einhorn, A. H. (1981). Heads or tails you lose: The dilemmas of psychiatric informed. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 1(2), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004714-198103000-00012

- Gefenas, E. (2012). Informed consent. In R. Chadwick, D. Callahan & P. Singer (Eds.), Encyclopedia of applied ethics (2nd ed., pp. 721–730).

- Goldbeck, R., Tomlinson, S., & Bouch, J. (1999). Patients’ knowledge and views of their depot neuroleptic medication. Psychiatric Bulletin, 23, 467–470. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.23.8.467

- Goldfarb, E., Fromson, J. A., Gorrindo, T., & Birnbaum, R. J. (2012). Enhancing informed consent best practices: Gaining patient, family and provider perspectives using reverse simulation. Journal of Medical Ethics, 38(9), 546–551. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2011-100206

- Harris, N., Lovell, K., & Day, J. (2002). Consent and long-term neuroleptic treatment. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 9(4), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00463.x

- Higgins, A., Barker, P.,& Begley, C.M. (2006). Iatrogenic sexual dysfunction and withholding of information Iatrogenic sexual dysfunction and the protective withholding of information: In whose best interest? Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 13(4), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.01001.x

- Huggett, C., Birtel, M. D., Awenat, Y. F., Fleming, P., Wilkes, S., Williams, S., & Haddock, G. (2018). A qualitative study: Experiences of stigma by people with mental health problems. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 91(3), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12167

- Ingelfinger, F. J. (1972). Informed (but uneducated) consent. New England Journal of Medicine, 287(9), 465–466. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197208312870912

- Katz, S., Goldblatt, H., Hasson-Ohayon, I., & Roe, D. (2019). Retrospective accounts of the process of using and discontinuing psychiatric medication. Qualitative Health Research, 29(2), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318793418

- Keepers, G. A., Fochtmann, L. J., Anzia, J. M., Benjamin, S., Lyness, J. M., Mojtabai, R., Servis, M., Walaszek, A., Buckley, P., Lenzenweger, M. F., Young, A. S., Degenhardt, A., & Hong, S. H. (2020). The American psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(9), 868–872. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.177901

- Kitamura, T. (2005). Stress-reductive effects of information disclosure to medical and psychiatric patients. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 59(6), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01428.x

- Kleinman, I., Schachter, D., Jeffries, J., Goldhamer, P. (1996). Informed consent and tardive dyskinesia: Long-term follow-up. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 184(9), 517–522. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199609000-00001

- Kleinman, I., Schachter, D., & Koritar, E. (1989). Informed consent and tardive dyskinesia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146(7), 902–904.

- Laugharne, J., & Brown, S. (1998). Informed consent and antipsychotic use in patients with schizophrenia issues and recommendations. Current Opinion CNS Drugs, 9(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-199809010-00001

- Laugharne, J., Davies, A., Arcelus, J., & Bouman, W. P. (2004). Informing patients about tardive dyskinesia: A survey of clinicians’ attitudes in three countries. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 27(1), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2003.12.004

- Linden, M., & Chaskel, R. (1981). Information and consent in schizophrenic patients in long-term treatment. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 7(3), 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/7.3.372

- Martínez-Hernáez, Á., Pié-Balaguer, A., Serrano-Miguel, M., Morales-Sáez, N., García-Santesmases, A., Bekele, D., & Alegre-Agís, E. (2020). The collaborative management of antipsychotic medication and its obstacles: A qualitative study. Social Science and Medicine, 247, 247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112811

- Masand, P. S., Schwartz, T. L., Wang, X., Kuhles, D. J., Gupta, S., Agharkar, B., Manjooran, J., Hameed, M. A., Hardoby, W., Virk, S., & Frank, B. (2002). Prescribing conventional antipsychotics in the era of novel antipsychotics: Informed consent issues. American Journal of Therapeutics, 9(6), 484–487. https://doi.org/10.1097/00045391-200211000-00004

- Mcmurray, L. (2002). Applying principles of informed consent to clinical practice in Psychiatry. CPA Bulletin de I’APC, 34, 16–18.

- Nha Hong, Q., Gonzalez-Reyes, A., & Pluye, P. (2018). Improving the usefulness of tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(3), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12884

- NHS. (2022a, September 7). Mental health act. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/social-care-and-your-rights/mental-health-and-the-law/mental-health-act/

- NHS. (2022b, December 8). Overview: Consent to treatment. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/consent-to-treatment/#:~:text=Consent%20to%20treatment%20means%20a,an%20explanation%20by%20a%20clinician.

- NHS. (2023, September 19). Advance decision to refuse treatment (living will). https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/end-of-life-care/planning-ahead/advance-decision-to-refuse-treatment/

- NICE Clinical Guidance [CG178]. (2014). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: The guideline on treatment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178

- Noor, U. S., Muraruaiah, S., & Chandrashekar, H. (2019). Medication adherence in schizophrenia: Understanding patient’s views. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 1. https://doi.org/10.5455/njppp.2019.9.0206002032019

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pies, R. (2007). How ‘objective’ are psychiatric diagnoses? Pyschiatry, 10, 18–22.

- Pozón, S. R. (2015). Elementos necesarios al consentimiento informado en pacientes con esquizofrenia. Revista Bioética, 23(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-80422015231042

- Rajkumar, A. P., Horsdal, H. T., Wimberley, T., Cohen, D., Mors, O., Børglum, A. D., & Gasse, C. (2017). Endogenous and antipsychotic-related risks for diabetes mellitus in young people with schizophrenia: A danish population-based cohort study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(7), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16040442

- Read, J. (2022). The experiences of 585 people when they tried to withdraw from antipsychotic drugs. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 15, 100421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100421

- Read, J., & Sacia, A. (2020). Using open questions to understand 650 people’s experiences with antipsychotic drugs. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(4), 896–904. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa002

- Read, J., & Williams, J. (2019). Positive and negative effects of antipsychotic medication: An international online survey of 832 recipients. Current Drug Safety, 14(3), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574886314666190301152734

- Roe, D., Goldblatt, H., Baloush-Klienman, V., Swarbrick, M., & Davidson, L. (2009). Why and how people decide to stop taking prescribed psychiatric medication: Exploring the subjective process of choice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 33(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.2975/33.1.2009.38.46

- Rofail, D., Heelis, R., & Gournay, K. (2009). Results of a thematic analysis to explore the experiences of patients with schizophrenia taking antipsychotic medication. Clinical Therapeutics, 31(SUPPL. 1), 1488–1496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.07.001

- Rössler, W. (2016). The stigma of mental disorders. EMBO Reports, 17(9), 1250–1253. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201643041

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2018, August). Being sectioned (in England and Wales). https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/treatments-and-wellbeing/being-sectioned

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2023). Report CR190: The risks and benefits of high-dose antipsychotic medication.

- Salomon, C., Hamilton, B., & Elsom, S. (2014). Experiencing antipsychotic discontinuation: Results from a survey of Australian consumers. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(10), 917–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12178

- Schachter, D. C., & Kleinman, I. (2004). Psychiatrists’ attitudes about and informed consent practices for antipsychotics and tardive dyskinesia. Psychiatric Services, 55(6), 714–717. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.6.714

- Schachter, D., Kleinman, I., & Williams, F. J. I. (1999). Informed consent for antipsychotic medication do family physicians document obtaining it? Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 45, 1502–1508.

- Takeuchi, H., Suzuki, T., Uchida, H., Watanabe, K., & Mimura, M. (2012). Antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia in the maintenance phase: A systematic review of the guidelines and algorithms. Schizophrenia Research, 134(2–3), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.11.021

- Thompson, J., Stansfeld, J. L., Cooper, R. E., Morant, N., Crellin, N. E., & Moncrieff, J. (2020). Experiences of taking neuroleptic medication and impacts on symptoms, sense of self and agency: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative data. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01819-2

- Tryer, P. (2000). A patient who changed my practice: The case for patient-based evidence versus trial-based evidence. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 4(3), 253–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651500050518181

- Tryer, P., Smith, J., & Adshead, G. (1994). Ethical dilemmas in drug treatments. Psychiatric Bulletin, 18(4), 203–204. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.18.4.203

- Usher Rn, K. J., Dhs, R., Frcna, F., & Arthur, D. (1998). Process consent: A model for enhancing informed consent in mental health nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27(4), 692–697. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00589.x

- Ventura, C. A. A., Austin, W., Carrara, B. S., & de Brito, E. S. (2021). Nursing care in mental health: Human rights and ethical issues. Nursing Ethics, 28(4), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020952102

- Waterreus, A., Morgan, V. A., Castle, D., Galletly, C., Jablensky, A., DiPrinzio, P., & Shah, S. (2012). Medication for psychosis – Consumption and consequences: The second Australian national survey of psychosis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(8), 762–773. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412450471

- Weir, K. (2012, June). The roots of mental illness. Monitor on Psychology. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/roots

- WHO. (2015). WHO global strategy on integrated people-centred health services 2016–2026. http://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/en.

- Zisman-Ilani, Y., Shern, D., Deegan, P., Kreyenbuhl, J., Dixon, L., Drake, R., Torrey, W., Mishra, M., Gorbenko, K., & Elwyn, G. (2018). Continue, adjust, or stop antipsychotic medication: Developing and user testing an encounter decision aid for people with first-episode and long-term psychosis. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1707-x