ABSTRACT

Background

People who identify as “multiple” are people who share a singular body with other individual selves. Whilst there are similarities to clinically defined criteria of dissociative and psychosis diagnoses, people with multiplicity lack an impairment in functioning due to being a multiple self, and often lack amnesia.

Methods

Six areas of focus (identified via an online consultation with members of the multiplicity community) were explored with 34 individuals: experts-by-experience (10 semi-structured interviews, 15 surveys), support networks (two interviews, four surveys), and professionals (one interview, two surveys). Constructivist grounded theory was used to examine the qualitative data collected.

Results

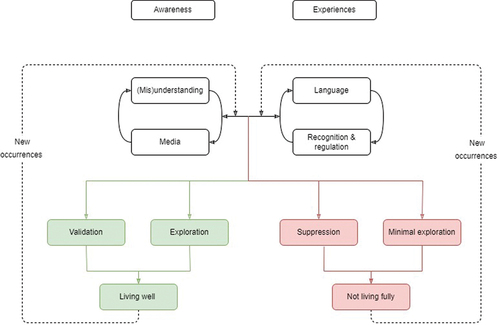

An emerging model was constructed to conceptualise the experience of being multiple. “(Mis)understanding”, “Media”, “Language”, and “Recognition and Regulation” were identified as core, reciprocally influential processes.

Discussion

The findings support the notion that the experience of being multiple is experientially distinct from a clinical understanding of dissociative and psychosis experiences. Positive processes can allow experts-by-experience to live well as a multiple self. Tailored support, understanding, and language is required to allow for validation of experiences and specific support to be accessed, both formally and via peer networks. Further research is necessary to elaborate our ever-growing understanding of this under-researched area.

Introduction

The knowledge base surrounding multiplicity (the non-clinical experience of having more than one self sharing one body) is currently lacking, as demonstrated by a recent systematic review (Eve et al., Citation2024). The understanding is currently linked to clinical forms of dissociation-psychosis spectrum disorders, with minimal recognition of non-clinical experiences. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2022, p. 291) defines dissociation (and by extension the spectrum of experiences) as an interruption or break in the typical integration of “consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behaviour”. Dissociation has been argued to be along a continuum, with many experiencing everyday absorption, like daydreaming or zoning out during repetitive tasks (referred to as normative dissociative experiences). Creative individuals, including actors and novelists, exhibit such experiences, characterized by absorption, imagination, and identity diffusion. Thomson et al. (Citation2009) examined whether these experiences align with pathological constructs, finding that while creative individuals scored high in fantasy proneness, they did not reach pathological levels on the Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (a screening instrument; Bernstein & Putnam, Citation1986), supporting the continuum of severity and potential utility of normative dissociation.

Self-multiplicity refers to the notion that individuals possess multiple facets or aspects of their identities, personalities, and experiences (Klein, Citation2010). It suggests that people are not defined by a singular, fixed identity, but rather by a complex interplay of various selves that may emerge in different contexts or situations (Lester, Citation2012). Within the concept, there is acknowledgement that individuals may exhibit different traits, behaviours, and roles depending on the social, cultural, and environmental factors involved (e.g. someone behaving differently in professional settings compared to social gatherings). Self-multiplicity does not imply a pathological condition; instead, it reflects normal variability and adaptability of human identity (Lester, Citation2010). However, self-multiplicity conceptualises elements or parts of one identity or individual. Opposing this notion is the experience of multiplicity – in the context of this research, the term multiplicity is referring to the holistic experience of having two or more individuals residing within one body.

Multiplicity has been closely linked to Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), which is considered a clinically significant mental health condition that often adversely affects people’s quality of life, functioning, and future prospects if access to suitable mental health support and treatment is not available to aid the integration of memories, thoughts, feelings, and and to facilitate healing from past trauma (Ribáry et al., Citation2017). According to the DSM-5-TR, the criteria for DID includes: two or more distinct identities, distress or impaired functioning, and amnesia of events (APA, Citation2022). The disorder is characterised by impaired functioning, high levels of distress, and disrupted constructions of self-identity (Şar et al., Citation2017). Consequently, DID is understood as a complex mental health condition and requires collaboration between the system (individual selves encompassed within the body) experiencing DID and specialist mental health practitioners to work towards a point of healing.

Conversely, while systems experiencing multiplicity often report the presence of two or more selves sharing one body, multiplicity does not tend to incorporate amnesia, distress due to a lack of integration of thoughts or feelings, or impairment in functioning (Ribáry et al., Citation2017). People aligning with the non-clinical explanation of multiplicity indicate their ability to live well in relation to memory, perception of the environment and consciousness, supporting the notion of a continuum of experiences (Eve et al., Citation2023). Definitional imprecision of multiplicity and a lack of robust research increases the misunderstanding in common parlance that multiplicity and DID exist on a continuum of distress and impairment, rather than recognising coping and functioning well as a multiple self, and often results in the devaluing of individual experiences of multiplicity.

Recent research highlights the complex nature of dissociative experiences, often viewed within discrete criteria. Studies have linked dissociative-psychosis spectrum conditions, showing associations between auditory hallucinations and dissociation (Pilton et al., Citation2015). Both psychosis and dissociation exist on a continuum (Reininghaus et al., Citation2019), raising questions about the placement of multiplicity on the psychosis spectrum due to limited symptom-specific knowledge (Longden et al., Citation2020). Dissociative experiences entail disconnection (e.g. selves who can affect the body), while psychosis involves addition (e.g. having multiple selves who share one body). However, rigid categorization may not fully capture the multiplicity experience. Further phenomenological understanding is needed to clarify if multiplicity aligns with either spectrum, or neither.

There is particularly scarce research with young people who identify as multiple outside of a diagnostic conceptualisation of what being multiple means for the individual system (the selves residing within the body), which means we also miss a developmental perspective on the process of “becoming” oneself, which may include a greater or lesser sense of multiplicity for some young people (Eve et al., Citation2024). This missed opportunity is highly relevant in a clinical space as well, as prevalence rates for DID appear to be higher amongst adolescents in mental health settings (Şar et al., Citation2017), so we might hypothesise that prevalence of multiplicity might be higher for youth experiencing challenges to their mental health more broadly, which could influence decision making in terms of what support to offer. Additionally, qualitative research with people with lived experience has indicated that many people first experience multiplicity in their adolescence (e.g. Parry et al., Citation2018), highlighting the need for further research with young people who experience themselves as multiple.

In recent years, there has been an argument emerging that people who experience dissociation lack insight into their own experiences, thus across the spectrum of research, there has been a predominant focus on professional understandings (Şar et al., Citation2017). However, as noted by Klaas et al. (Citation2017), gaining accurate insights into individual experiences is essential to aid understanding of under-researched phenomena. Personal accounts can provide insight and context into people’s conceptualizations and provide an accurate perspective on this under-researched area (Loewenstein, Citation2018). Due to the lack of research that directly explores lived experiences of young adults’ conceptualisation of, and navigation through life with experiences of being multiple, the current study aimed to explore the novel understanding through a non-clinical lens.

Research questions

What does the experience of multiplicity consist of for young adults?

How do experiences of multiplicity impact young adults’ psychosocial functioning?

Methodology

Study design

Due to the lack of substantive academic knowledge available surrounding the topic of emerging multiplicity, a grounded theory method was utilised (Charmaz, Citation2006). Such methods are particularly appropriate for under-researched areas, in order for theoretical models to be developed which are grounded in the experiences of the participant group (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). Unlike other qualitative research methods which can start with a preconceived theory or hypothesis (e.g. content analysis, narrative analysis), grounded theory starts with the data, and develops a theory based on themes emerging from the data (Charmaz, Citation2014). The iterative nature of data collection and analysis allows the focus to be revised throughout the process, developing specific focus and insights. Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT) was identified as the most appropriate method as it allows for the research to preserve the complexity of social life within data collection and analysis (Charmaz, Citation2008). Alternative to classical grounded theory, which argues for the researcher to remain a neutral observer, CGT acknowledges the role of the researcher within the process, arguing that the researcher is not an impartial observer, but a co-participant (Mills et al., Citation2006). As such, the development of the emergent theory was iteratively co-constructed by the researchers and participants over a period of three years. Ethical approval (number 24 208) was granted from Manchester Metropolitan University in September 2020.

Participants

A total of 34 participants were recruited through social media advertisement via Twitter. All participants self-reported experiences of multiplicity, either via lived experience (10 interviews and 15 surveys), support networks (two interviews, four surveys), or professionals who work with people experiencing multiplicity (one interview, two surveys). In line with the notion of saturation within grounded theory, different participant group sizes were included, with the focus remaining on the views of experts-by-experience throughout, in order to elucidate lived experiences not commonly heard from (O’Reilly & Parker, Citation2013). Support networks and professional narratives were explored in a validatory, holistic manner, adding depth, validation, and context around the wider impacts of multiplicity experiences, while keeping the focus on lived experience narratives.

All participants were over 16 years of age, were fluent in English, and had personal or professional experiences. Participants with and without a psychiatric diagnosis were included in the study, as long as they self-identified as aligning with multiplicity. Participants demographic information was obtained (see ), and all participants gave written informed consent before taking part in the study. Interviewees also gave verbal consent prior to the interview commencing.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Data collection

The semi-structured interview schedule was informed by an online consultation, in which 94 individuals with awareness and/or experiences of multiplicity shared their hopes for the research focus, avenues for exploration, and suggestions for terminology (see Eve & Parry, Citation2021, Citation2022). Respondents also discussed preferences for research design, which resulted in the option of an interview or survey, both conducted online between 2021 and 2022 due to COVID-19 restrictions. Participants chose whether to participant in an interview or online survey. These responses were taken forward into six key areas of interest within the online semi-structured interviews and surveys including free text boxes for responses: understanding; language; previous research; day-to-day living; support; and information and resources. Participants were theoretically sampled; individuals who felt they aligned with multiplicity more than diagnostic constructs were selected to ensure areas of interest were examined and explored closely (Charmaz, Citation2006). Support networks and professional accounts added validation and nuance to the emerging themes, although the research remained centred on lived experiences throughout.

The 13 interviews conducted by author 1 lasted between 13 and 75 minutes (average 45 minutes), with seven interviews lasting between 40 and 70 minutes. The interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams, during which participants could choose whether to turn their cameras on or have increased anonymity by being voice-only. Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Surveys were conducted via Qualtrics and included questions within the six thematic areas, along with free text boxes for respondents to include further information not explicitly requested. Qualitative responses were exported for analysis. Intelligent verbatim transcription was used to transcribe participant responses. This is viewed as a “cleaned up” version of verbatim transcription, whereby repetition, pauses and “ums” are not included. It was decided to only include the interviewee’s words, and not include pauses, intonation, or other expressions, due to the potential unfamiliarity of being interviewed via video conferencing.

Data analysis

Constructivist grounded theory (Bryant & Charmaz, Citation2007; Charmaz, Citation2006) was used flexibly to analyse the data. Due to needs of participants, full data coding and analysis of initial interviews was not conducted simultaneously to data collection, however reflective notes and initial memos were recorded post each interview, allowing the interview questions to evolve and develop in line with the emerging core concepts.

The computer software NVivo (version 12) was used to analyse the data, and record memos throughout the process by author 1, with support and sense checking by authors 2 and 3. Initial line-by-line coding was conducted to generate ideas for perusal, which led to a second, focused phase of coding. This involved organising the data into preliminary categories. Through constant comparison, theoretical sorting, and diagramming (Charmaz, Citation2014), we clarified the categories and relationships. Memo writing and reflective notes were used to generate conceptual insights, and to identify similarities and differences across the data.

Quality assurance

While it is understood that the emerging theory was co-created by the researchers and participants within constructivist grounded theory, it is important that the theory is reflective of people’s lived experiences. Participants were sent full transcriptions of their interviews for them to review and confirm accuracy, along with the opportunity to remove information or elucidate on responses, of which one participant emailed further narratives which were included in the analysis. Early transcripts were coded and analysed with other researchers (authors 2, 3) to minimise researcher bias, and ensure codes were accurately capturing the data. The primary researcher (author 1) was reflexive throughout the process, writing a diary post each interview, transcription, and coding.

Results

This study explored how young adults conceptualise their multiplicity experiences, and how such experiences impact psychosocial functioning. A number of factors emerged from the data analysis, which resulted in a preliminary theory of multiplicity to be constructed ().

Figure 1. EMBRACE theoretical model (Exploring mental health beliefs, recognition and communication for empathetic understanding).

Four categories emerged as important factors that contributed to how people conceptualise their multiplicity experiences, and the resultant impact on their day-to-day living as a multiple self: “(Mis)understanding”, “Media”, “Language”, and “Recognition and Regulation”.

(Mis)understanding

The level of understanding in relation to what multiplicity experiences are, and the level of support provided were interlinked within participant narratives, from all three groups. With increased awareness and understanding of the specific multiplicity experiences, support networks and professionals felt they could offer more personalised support, which in turn resulted in experts-by-experience feeling validated and supported.

They couldn’t grasp the concept very well and resorted to mostly clinical views of plurality - if not outright disrespectful stuff that even exists out of any clinical boundaries of the topic. (Ida, Expert-by-experience)

If the general public did have some knowledge, it often only consisted of medicalised information, such as the basics of DID which made disclosing multiplicity experiences difficult.

I find the viewpoint of strictly only disordered or medicalised multiplicity to be harmful to all involved. Especially if you don’t seem to “suffer” from being multiple. (Jello, Expert-by-experience)

Support networks discussed noticing differences in behaviour in their loved ones, but not being aware of the specific experience, or how to broach the topic with them.

I didn’t notice it beforehand, but something was going on … when I found out, it kind of made sense, some of the past experiences that I was like, okay, this is why she was acting like a child that one time. (Shifra, Support network)

Professionals discussed the complex nature of support and understanding, with them often relying on assumptions made around the topic due to the lack of specific training offered as standard practice.

I found it extremely difficult to support people with multiplicity due to the lack of knowledge in the field. As a professional, I felt completely unprepared. (Sarah, professional)

Overall, participants discussed the importance of having specific, tailored understanding which aligned with people’s lived experiences of being a multiple self, as opposed to solely relying on a medicalised understanding of DID and then applying it to experiences of multiplicity too. By having clear information about multiplicity, all three participant groups would benefit, allowing experts-by-experience to feel validated and supported by others.

Media

The media often dramatizes multiplicity, particularly focusing on medicalized conditions like Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), influencing public perception. Negative depictions in films such as Split and The Three Faces of Eve have harmed identity formation and self-understanding, shaping how individuals present themselves to society.

But I guess it’s just that what I think people don’t know is that it can be something that can be managed, and also that nothing is violent, or criminal about it inherently. And it’s not like crazy, super scary things that psychological horror movies focus on because it’s not like that at all. (Claire, Expert-by-experience)

Majority of experts-by-experience discussed having to disclose their experiences of multiplicity using references to popular media portrayals such as Split, as that is a depiction people are often familiar with. However, this then resulted in people having to explain how their own experiences differ greatly from media representation, even going as far as confirming they will not harm them, and that they do not have “superpowers” when they switch between members, as is portrayed in media.

Plurality is often used as a scare element in horror movies and writing. Often times it’ll involve a plot where a plural character secretly has a “super scary axe murderer alter” who happens to take over control and kill everyone. To people in the know, this is generally seen as extremely inaccurate and harmful representation. (Ida, Expert-by-experience)

By only presenting negative portrayals of experiences, experts-by-experience felt misunderstood, misaligned, and fearful of people’s reactions. As a result of the lack of awareness within media as to the range of experiences, and the functionality of people’s multiplicity, experts-by-experience remain omitted from general understanding.

Language

All participant groups acknowledged language as a significant influence on the conceptualisation, understanding, and support of multiplicity. Currently, there is limited language in everyday discourse specifically addressing non-clinical or positive aspects of multiplicity. Experts-by-experience often struggled to find information reflecting their experiences due to the lack of specific terminology. Resorting to medicalised language often led to encountering negative portrayals online.

I think it’s really limiting to just focus on DID, I think we need research from all angles. Especially not just systems that are having trouble functioning together – we have to look at people who are doing well, in order to find out how to help those that aren’t surely? (S, Support network)

Often a range of damaging information, stories, clinical experiences, and negative portrayals would be viewed by people with multiplicity and their support networks. This impacted people’s views of their own experiences, particularly for those whose experiences had recently emerged, who had begun to develop negative conceptualisations of themselves and their multiplicity, with them assuming they could only have negative experiences.

We are scared as to how people will react. Will they leave, treat us wrongly, or fake claim? Multiplicity isn’t the norm, so people treat it strangely, especially due to stigma. (Jello, Expert-by-experience)

Through immersion within an online community (often via social media) specifically for those aligning with multiplicity, understanding of tailored language was developed by the community, which resulted in validation of positive conceptualisations and understandings for all participants.

… for way too many plurals [an alternative word for people with multiplicity] it just feels like a miracle to come across any space that doesn’t nitpick them, or dissect them, and just treats them as they want to be treated, using the words that they want for them. (Songbirds, Expert-by-experience)

In spite of experts-by-experience having knowledge of specific language (see ), this has not permeated into general usage as yet. Thus professionals, support networks, and the general public do not have awareness of the tailored language with which to discuss experiences with those with multiplicity. As such, experts-by-experience often revert to using clinical terminology when discussing their lives as these phrases are more commonly understood by the general public.

I kind of don’t want to go through the multiplicity 101 [back to basics explanation] with every new person. Especially because, again multiplicity 101 kind of has to, not start with, but has to be like “here’s DID, and we’re not that”. (Ayden, Expert-by-experience)

Positively, when tailored and accurate language that is accepted by the community of people with multiplicity is used by various stakeholders including support networks and professionals, experts-by-experience feel validated and supported.

I prefer to use whatever language the person feels most comfortable with, or that most closely captures their experiences. (Sarah, professional)

Language was a key factor to all participants which influences how people understand, manage, and explore their multiplicity experiences. By permeating the language used by the community to the general public and professionals, people sharing their experiences or seeking support may feel validated, understood, and supported. It is vital that language used is tailored to the experiences of multiples, aligning with the positive, functional nature of multiplicity, while allowing for individual choice in language use to be identified.

Recognition and regulation

Experts-by-experience, support networks and professionals all discussed the importance of recognition and regulation of multiplicity experiences. Recognition was discussed by experts-by-experience on two planes – that of having recognition of the self as an individual, as well as recognising and understanding that they are part of a wider bodily system that encompasses multiple selves.

Yes, we are parts of a greater whole, but also everyone is even singular people, are part of their family, part of their community and so on. So we are parts of this collective [alternative word for system], but that doesn’t mean we are any less people. (Songbirds, Expert-by-experience)

The conceptualisation of the self was reported by participants as often being more stable and remains relatively consistent across the lifespan (as it would with any singular person who undergoes growth and development). Comparatively, the stability of the system tends to fluctuate for many, with new selves emerging over time, and other selves making decisions to integrate into the body. As such, there is somewhat of an ebb and flow to how individuals conceptualise and recognise their system over time.

In the beginning, when I didn’t know what was going on, it [the experience of being multiple] was very scattered, you know, my day-to-day life would be a lot of memory loss and just being confused or angry or having a lot of feelings that I didn’t understand where they were coming from. But now, I do feel like I’m able to have a job and go to school and be in a relationship and live with another person and do a lot of things because I have more contact with people inside. (Claire, Expert-by-experience)

Recognition was also discussed as being important from professionals, and for professionals. Experts-by-experience often felt that professionals lacked the necessary understanding, client centred focus, and curiosity about non-pathologised experiences such as multiplicity, which resulted in them not engaging in support, or having to hide parts of themselves in order to access said support.

We have a very hard time hammering that into other people’s heads like, No, we are separate people. I am not this person. They are not me. We are not that close. (Soul System, Expert-by-experience)

Professionals were open about their experiences of navigating the complexity of working with multiple selves that reside in a singular body, particularly with a lack of training and support themselves.

No formal training has ever been offered (Eli, professional)

Professionals making space for experts-by-experience to explore their multiplicity journey in a safe space, develop positive internal communication between selves, and facilitating support with psychosocial functioning was touted as key elements of a therapy process outside of medicalisation.

The person would guide you in terms of what they want from the session … . I think it would be around trying to create an environment where the person is exploring the process of change and moving towards that however that manifests (John, professional)

Positive examples of support techniques aiding regulation that were discussed by all three participant groups included actively acknowledging other selves within the system and trying to develop relationships with other selves. Support networks discussed the importance of developing relationships with different selves. As specific system members may be more comfortable fronting in the body, selves that don’t engage externally may feel less validated or “seen”, thus support networks actively engaging with them was viewed positively by many.

In the case of me and my partners, I just decided to try and woo all four of them, and they all fell in love with me. So now I’m married to four people, but from a legal perspective, I’m just married to the primary. On the other hand, we have a system-friend who believes they will never find love because there’s over a hundred people in there and they think the logistical problems are too much to get around. (Psychologist-in-training-that-is-married-to-a-multiple, Support network)

Overall, people with experiences of multiplicity are aware of being an individual self, as well as being a member of a wider system who share one body. There is often shared memory space, communication between selves, and structures for navigating the external world. This opposes clinical experiences where such experiences are often disrupted (Şar et al., Citation2017). As such, there is a requirement for tailored recognition and support from professionals and support networks as to the specific experience of being a multiple self. People with lived experience do not commonly want to integrate their system (into one mind, one body), but instead request specific support to navigate the world as a functional, positive multiple system.

Outcomes

Respondents discussed how core categories affected their daily lives as multiple selves, often describing it as either a positive or negative journey. Positive awareness and experiences validate and understand experts-by-experience, while misunderstanding may lead to suppressing multiplicity. The model portrays a dynamic journey, where positive outcomes aren’t guaranteed indefinitely; new experiences or stressors may alter one’s path. Conversely, negative outcomes aren’t permanent; with new information or positive representation, experiences may become validating. The hope is for reduced misunderstanding and tailored understanding to emerge from research, practice, and community efforts, reflecting individuals’ unique experiences.

Discussion

This study sought to construct a theoretical model to conceptualise the experience of emerging multiplicity within a young adult population. The emergent grounded theory highlights the complexity of navigating a singular world (people living as one self, one body) as a multiple self, and the range of factors that influence positive self-conceptualisation and living well. “(Mis)understanding”, “Media”, “Language” and “Recognition and Regulation” were defined as core categories.

Findings were consistent with preliminary research exploring the experience of emerging multiplicity as its own distinct experience, outside the lens of clinical criteria (Ribáry et al., Citation2017). This included the understanding that those who identify as multiple can, and often do, live well as a member of a system comprising of multiple selves. Participants discussed having awareness of other system members internally, the importance of developing positive communication between selves, and the utility of sharing the body with members who wish to front. As with other “unusual” sensory experiences, the importance of allowing people to develop individual ways of understanding their experiences, identifying coping strategies, and exploring their worlds in relation to such experiences have been found to be key elements of living well (Parry et al., Citation2020).

The lack of knowledge within the general public in regard to common presenting behaviours that is commonly seen in those with DID (Reinders & Veltman, Citation2021), has also been found to extend to those experiencing multiplicity in this study. Similarly, participants in this study discuss their reluctance to live openly as a multiple self in a world that does not currently understand them. This results in personal suffering, inability to explore their own world, and feelings of needing to suppress their full selves for others (Dorahy et al., Citation2023). By developing tailored awareness, understanding, and language for the specific experience of multiplicity, individuals with lived experiences will feel validated and understood.

The importance of understanding how multiplicity differs from clinical experiences, such as DID, is vital, and can be linked to the development of the Hearing Voices Movement (HVM). Developed by Romme, Escher, and Hage in the 1980’s, the HVM challenged the traditional biomedical understanding of voice hearing, instead arguing for the importance of accepting voices, rather than solely viewing them as a symptom of illness (Romme & Escher, Citation2000). A similar argument has emerged within this study, and the wider multiplicity community; for some people clinical criteria are essential and align to experiences, while for others a more holistic understanding is required, which allows for acceptance of non-clinical experiences. By having tailored understanding and knowledge in regard to the distinct constructs, there is hope for specific support to be available across the spectrum.

Participants in this study argued for the importance of peer support from others who live well with their experiences, providing support, understanding, and opportunities for exploration. Peers can provide credible role models for individuals due to their shared experiences, empowering those with lived experience (Salzer & Shear, Citation2002). Working within the individual’s own framework of understanding is key to developing positive connections, reducing stigma, and distress associated with being “different” or feeling misunderstood by others in a shared culture and society. In addition to peer support, tailored professional support was highlighted as key, although the importance of understanding the non-clinical nature of multiplicity was stressed. This may be new to professionals who have often worked to challenge beliefs, or “fix” such experiences, due to the common link to mental health conditions. Empowering clients to lead therapy, providing normalisation, and fostering a safe environment for exploring experiences within a trusting therapeutic relationship may promote the development of a positive self-narrative, enhance internal communication, and lead to acceptance and wellbeing in individuals with multiplicity.

Limitations and future research

Due to the exploratory and novel nature of the area of research, a small sample of individuals identifying with multiplicity were included in the study, which may not be wholly reflective of the experience. Further data collection is necessary in order to refine and test the theoretical model, and draw firmer conclusions (Charmaz, Citation2006). As a young adult population was the focus, future research would benefit from longitudinal designs, exploring the change in understanding, acceptance and coping with such experiences over the life-course.

Conclusion

Multiplicity is a relatively new area of interest within the academic sphere, being a group of individual selves who share the same body. However, there is increasing awareness of the commonality of the experience, and thus the need for improved understanding outside of a clinical lens. Overall, navigating life as a multiple self can be complex, however often life-enhancing, and positive. This model is the first to conceptualise multiplicity as a process outside the lens of medicalisation and clinical constructs, identifying the need for tailored understanding, language, and recognition, allowing multiples to explore their inner worlds, and navigate the external world positively. Further research is needed to explore the phenomenon as a healthy way of living.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express thanks to all of the people who participated in this study, and everyone who engaged with the online consultation who helped developed the project. We would also like to thank our anonymous reviewers for their helpful contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Bernstein, E. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 174(12), 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (2007). The Sage handbook of grounded theory. Sage Publications.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Charmaz, K. (2008). Grounded theory as an emergent method. In S. N. Hesse-Bieber & P. Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp. 155–172). Guilford Press.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dorahy, M. J., Yogeeswaran, K., & Middleton, W. (2023). Dissociation-Induced shame in those with a dissociative disorder: Assessing the impact of relationship context using vignettes. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 24(5), 674–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2023.2195402

- Eve, Z., Heyes, K., & Parry, S. (2023). Conceptualizing multiplicity spectrum experiences: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2910

- Eve, Z., Heyes, K. & Parry, S. (2024). Conceptualizing multiplicity spectrum experiences: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 31(1), e2910.

- Eve, Z., & Parry, S. (2021). Exploring the experiences of young people with multiplicity. Youth and policy. https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/young-people-with-multiplicity/

- Eve, Z., & Parry, S. (2022). Online participatory research: Lessons for good practice and inclusivity with marginalized young people. SAGE Research Methods: Doing Research Online.

- Klaas, H., Clémence, A., Marion-Veyron, R., Antonietti, J., Alameda, L., Golay, P., & Conus, P. (2017). Insight as a social identity process in the evolution of psychosocial functioning in the early phase of psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 47(4), 718–729. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002506

- Klein, S. B. (2010). The self: As a construct in psychology and neuropsychological evidence for its multiplicity. WIREs Cognitive Science, 1(2), 172–183.

- Lester, D. (2010). A multiple self theory of personality. Nova Science.

- Lester, D. (2012). A multiple self theory of the mind. Comprehensive Psychology, 1, 5.

- Loewenstein, R. J. (2018). Dissociation debates: Everything you know is wrong. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 20(1), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.3/rloewenstein

- Longden, E., Branitsky, A., Moskowitz, A., Berry, K., Bucci, S., & Varese, F. (2020). The relationship between dissociation and symptoms of psychosis: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(5), 1104–1113. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa037

- Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2006). The development of constructivist grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500103

- O’Reilly, M., & Parker, N. (2013). ‘Unsatisfactory saturation’: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated samples in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 13(2), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106

- Parry, S., Lloyd, M., & Simpson, J. (2018). “It’s not like you have PTSD with a touch of dissociation”: Understanding dissociative identity disorder through first person accounts. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 2(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2017.08.002

- Parry, S., Loren, E., & Varese, F. (2020). Young people’s narratives of hearing voices: Systemic influences and conceptual challenges. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 28(3), 715–726. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2532

- Pilton, M., Varese, F., Berry, K., & Bucci, S. (2015). The relationship between dissociation and voices: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 40(1), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.004

- Reinders, A., & Veltman, D. (2021). Dissociative identity disorder: Out of the shadows at last? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 219(1), 413–414. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.168

- Reininghaus, U., Böhnke, J. R., Chavez-Baldini, U., Gibbons, R., Ivleva, E., Clementz, B. A., Pearlson, G. D., Keshavan, M. S., Sweeney, J. A., & Tamminga, T. A. (2019). Transdiagnostic dimensions of psychosis in the Bipolar-Schizophrenia network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP). World Psychiatry, 18(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20607

- Ribáry, G., Lajtai, L., Demetrovics, Z., & Maraz, A. (2017). Multiplicity: An explorative interview study on personal experiences of people with multiple selves. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1), 938–947. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00938

- Romme, M., & Escher, S. (2000). Making sense of voices: The mental health professional’s guide to working with voice-hearers. Mind Publications.

- Salzer, M. S., & Shear, S. L. (2002). Identifying consumer-provided benefits in evaluations of consumer-delivered services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 3(1), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095014

- Şar, V., Dorahy, M. J., & Krüger, C. (2017). Revisiting the etiological aspects of dissociative identity disorder: A biopsychosocial perspective. Psychology Research and Behaviour Management, 10(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S113743

- Thomson, P., Keehn, E. B., & Gumpel, T. P. (2009). Generators and interpretors in a performing arts population: Dissociation, trauma, fantasy proneness, and affective states. Creativity Research Journal, 21(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410802633533