ABSTRACT

This paper explores how climate change communication is understood and enacted in Canada’s Provincial North (CPN), with a focus on the role that local climate champions play in regions characterized by rurality, remoteness, and a high degree of reliance on natural resource industries. Drawing from 24 in-depth interviews with individuals increasing local attention to climate in Northern British Columbia and Ontario, this research identifies communication challenges and opportunities arising in these contexts. Existing literature inadequately addresses the challenges of advancing climate change initiatives in rural and remote communities. Confirming and extending existing research on place-based communication, CPN climate champions underscored that messages must be place-based, community-informed, reflect local realities, and address the role of industry in regional economies. This paper offers an important set of insights that is relevant to climate change communication in other rural and remote settings in high-income countries.

Introduction

Northern Canada is disproportionately impacted by climate change. Despite increasing research on the social, cultural and environmental dimensions of climate change in the high and sub-arctic, there is a dearth of climate change research about the Canadian Provincial North (CPN). The CPN is a region characterized by rurality, remoteness, reliance on natural resource industries for economic development, and hinterland dynamics between smaller communities and urban centers where decision-making power has been consolidated (Coates et al., Citation1992; Coates et al., Citation2014). These contextual features drive an imperative for enhanced climate action and more generative climate change communication in northern community contexts which is informed by place-based social sciences research.

Communicating about climate change and engaging people in changing attitudes and behaviors is challenging (Khadka et al., Citation2020); however, conducting this work in rural and remote contexts (Hu & Chen, Citation2016; Ratinen & Uusiautti, Citation2020), such as the provincial north of Canada is a complex. Canada was founded on settler colonialism and resource extraction, and federal, provincial and territorial economies depend on primary industries. International and national dynamics become entangled in the CPN where binary discourses, such as those that pitch industry against climate, future generations against current ones, and environmental health against human health, are pervasive. Climate change impacts are compounded by localized social and ecological vulnerabilities (Picketts et al., Citation2020; Schweizer et al., Citation2013). Despite unprecedented evidence of climate driven events across the CPN (Costello et al., Citation2009; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Citation2014), talking about and promoting action on climate change remains challenging and can be divisive (Galway et al., Citation2020).

Despite aspirations to take individual, collective, and institutional action on climate change, knowledge sharing has had limited success in mobilizing engagement in communities across Canada and globally (Landriault, Citation2020; Moser & Dilling, Citation2011; Wibeck, Citation2014). This is explained in part by a continued reliance on the knowledge-deficit model of communication (Ballantyne, Citation2016; Fiske, Citation2002; Moser, Citation2014). This model aims to transfer information in a media-friendly “one size fits all” package to an imagined homogenous public thought to be motivated by new information. The knowledge-deficit model is increasingly criticized on this premise (Halperin & Walton, Citation2018; Lorenzoni et al., Citation2007; Moser & Dilling, Citation2011; Nicolosi & Corbett, Citation2018), underscoring the value of tailoring discourses to reflect context including localized beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions about climate change.

Place-based research on climate change perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs is critical for effective communication and engagement processes (Leisorowitz et al., Citation2010). Sturgis and Allum’s (Citation2004) move beyond a critique of the knowledge-deficit model, shifting the emphasis toward learning from climate champions (Watts et al., Citation2015; Wibeck, Citation2014). This paper also contributes to a growing corpus of research on the role that connection to place can play in changing people’s attitudes to taking action on climate change (Döring & Ratter, Citation2018; Groshong et al., Citation2019; Khadka et al., Citation2020). In the CPN, these climate champions are grounded in diverse northern contexts, respond to the challenge of motivating people in these settings and seek locally relevant ways to engage with climate change.

In this paper, we draw from interviews with community members in the CPN who facilitate place-based approaches to sharing ideas, cultivating partnerships, and developing innovative strategies toward climate action. We consider how champions invoke place and reference “pre-existing values, preferences, beliefs, norms and experiences” (Moser & Ekstrom, Citation2010, pp. 22029–22030) that are relevant to their own communities. Informed by Lorenzoni et al.’s (Citation2007) work on the importance of the interconnected dimensions of the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of citizen engagement, we confirm existing and offer new insights into how climate champions in the CPN are engaging with people where they live, learn, work, and recreate. We advocate for a more nuanced understandings of how place and people can inform communication and engagement and argue that including a consideration of context in climate communication will more effectively activate and strengthen citizen engagement.

Background

Context of the Canadian Provincial North

The CPN is a regional band that extends across Canada from British Columbia to Labrador, and encompasses numerous traditional Indigenous territories, vast landscapes, diverse ecosystems, and deep wilderness punctuated by “urban islands” and industrial camps (Coates & Poelzer, Citation2014). Across the CPN, sovereign Indigenous nations operating with self-determination for thousands of years have been systematically oppressed by settler colonial governments (Czyzewski, Citation2011; Parlee, Citation2015). The increasing intensification of the extraction of a range of natural resources, including oil and gas, minerals, rare-earth metals, lumber, fisheries, livestock, and renewable energy, have played a role in these histories. Over time many settler and Indigenous communities became dependent upon single resource economies, perpetuating ongoing challenges to Indigenous sovereignty and the upholding of treaty rights to control and steward un-ceded traditional territories (Parlee, Citation2015).

Ongoing colonial dynamics in the CPN mean that boundaries, borders, jurisdictions, governance frameworks, places, and priorities continue to evolve through treaty negotiations, trade agreements resource extraction projects, and development initiatives (Kukucha, Citation2016; Nicol, Citation2017; White, Citation2020). Communities across the CPN may also contend with underemployment, boom and bust economies, cultural and racialized discrimination, and widely dispersed infrastructure and social services (Czyzewski, Citation2011). Wilson and Poelzer also draw attention to inequitable provincial North–South relationships whereby “the South has benefited from resource development in the North, while at the same time reinforcing the problematic tendencies that keep the economies of the provincial Norths in flux” (Citation2005, p. 12). These political, economic, and social factors play out across vast geographies highly vulnerable to climate driven events such as wildfires, early ice melts, and flooding. These dynamics have also invoked calls for integrative governance opportunities spanning community, environmental, and health concerns relevant to the CPN (Gislason et al., Citation2018).

Research and evidence building also have a role to play. To date, inadequate attention has been paid to developing detailed insights into the regional and subregional impacts of climate change. For example, some climate models can generate findings for biogeoclimatic zones (e.g. coastal, prairie, arctic) yet little research integrates intersectional social data with these zoned climate predictions that would enable more nuanced local and regional planning. Intensive resource sector analyses of jobs, industry type or contribution to GDP are often by province or territory and do not disaggregate data by sub-region. Indigenous governance structures are also highly variable at the federal scale (e.g. Nunavut vs. Saskatchewan) as well as at the subregional down to municipal and Indigenous territorial governance scales.

Relatedly, the notion of the “forgotten north” put forth by Coates et al. (Citation1992) emphasizes the important and interconnected nature of knowledge gaps about the challenges and strengths of the CPN. The majority of climate change research in Canada has focused on large urban centers in the Canadian urban south or Northern territories. For example, according to a bibliometric analysis of government-funded social sciences and humanities research between 2000 and 2012, there is significantly less social sciences research focused on the CPN as compared to the Northern territories (Southcott, Citation2014). In addition, extant climate change literature tends to relate to specific extreme events with a considerable focus on returning to an economic normal in the wake of, for example, the forest fires that ravaged Fort McMurry in 2016 (Simms, Citation2016). Thus, the neglect of the CPN is reflected in a lack of research on both the effects of climate change, and appropriate adaptive responses which are place-based.

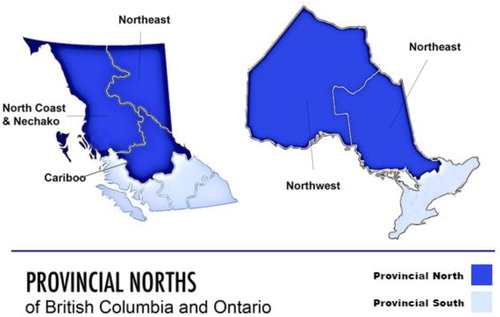

While the boundaries of the CPN are not consistently defined nor agreed upon, for the purposes of this study, we set our boundaries by the “economic regions” of the 2016 Canadian census (). Other approaches to delineate the CPN from the territorial and provincial south could have been to use political and administrative zones, climate zones, and geographical determinants (i.e. discontinuous permafrost line) (Coates & Poelzer, 2014) or Indigenous territories. Given the great expanse of the CPN, this paper focuses on two provincial northern regions: Ontario and British Columbia (see ) but offers learning for other place-based contexts relevant to a range of provincial, rural, remote and Indigenous communities.

Figure 1. The provincial north of British Columbia and Ontario, based on northern “economic regions” boundaries. Source: Statistics Canada (Citation2016).

Regions and communities in northern BC and northern Ontario share socioeconomic vulnerabilities related to education, income and marginalization (see ) – also common to other communities in the CPN. For example, as compared to Canada, the economic regions in northern BC and Ontario face high unemployment rates (12.3% and 9.25% respectively), and a higher proportion of employment is linked to resource economies. However, these industries also indirectly employ people through manufacturing, transportation, and other export industries – sectors which also account for significant employment. Host community economies are also influenced, such as through housing, hospitality and health services. These factors and the associated socioeconomic and ecological dynamics that play out across the CPN underscore the need for place-based approaches to inform climate communication and action.

Table 1. Demographic and social comparisons between northern “economic regions” in BC and Ontario.

Climate change communication and engagement: place-based approaches

Place is an important concept with regards to climate change research and engagement and is at the heart of contemporary scholarly discourses seeking to promote civic participation and transformative sustainable change (Devine-Wright, Citation2013; George & Reed, Citation2017 Marshall et al., Citation2018;). Place not only refers to specific geographical locations, but also to a range of forces which contour it, such as politics, populations, economies, institutions, nature and power which interact through myriad concentric circles of influence and a range of social and ecological relationships. Place is fluid, constantly co-created, and people are concurrently and reflexively shaped by place (Pulver et al., Citation2018), meaning that community members hold specific knowledges and connection to the places in which they are embedded and can, therefore, harness nuanced insights to support change-making initiatives.

Examining what climate change means for people in specific places, grounds experiences, and foregrounds people-place relationships in the context of a changing climate (Galway, Citation2019; Gislason et al., Citation2018; Picketts et al., Citation2020). Schweizer et al. (Citation2013) have developed an influential theoretical framework for place-based climate change engagement, drawing from place attachment theory, place-based pedagogy, free-choice learning, and norm activation theory. The framework emphasizes that meaningful communication and engagement should be action-oriented and occur within physical, material places.

Increasingly, people are coming to understand climate change impacts and solutions in relation to the natural landscapes in which they are embedded (Groulx et al., Citation2014). This knowledge provides a platform for narratives of change and can ground adaptation processes in local values (Krauß & Bremer, Citation2020; Moser, Citation2014). This is important because “inaction in the face of climate change can persist, even when citizens have a strong connection to place, particularly because dominant climate change communications fail to produce a socially salient message” (Groulx et al., Citation2014, p. 136). A systematic review on climate change engagement found that utilizing place attachment is an effective way of communicating about climate change, but that more research is needed to understand pathways and mechanisms towards action (Nicolosi & Corbett, Citation2018). In other words, place-based approaches acknowledge that context matters, reflecting an understanding that climate change communication and engagement should be informed by, and grounded in, localized knowledge, experiences and priorities (Khadka et al., Citation2020; Ostry et al., Citation2010; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2013).

Methods

This paper shares findings from the qualitative dimension of a larger study examining how to communicate climate change impacts and solutions to promote citizen engagement with climate change in the CPN, which utilized a combination of mail-out surveys, in-depth interviews and workshops. During interviews, climate champions were asked to describe how the places, people and living realities in Canada’s Provincial North shape how they communicate about climate change. The central question informing this research was “how can approaches to communication be improved in order to increase people’s experiences of connection and interest in engaging with issues of climate change in their region?” This study focused on the two regional case settings of the CPN, northern BC and northern Ontario (see ).

This exploratory qualitative study was approved by Research Ethics Boards at Lakehead University, the University of Northern British Columbia, and Simon Fraser University. We used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling as our recruitment strategy. Participants were initially recruited purposively via emails sent through local and regional organizations, listservs and networks aligned with climate change work. Participants also provided referrals to possible additional interviewees and in total 24 people were interviewed. Consistent with Buse et al. (Citation2019), we defined climate champions as individuals representing a range of viewpoints and experiences, who are recognized within communities across the regional case study settings as people actively working on climate change-related issues. This resulted in recruitment of a diverse group of participants including educators, researchers, climate activists and decision-makers (see ).

Table 2. Characteristics of interview participants.

Data were collected using a semi-structured interview guide, developed by the research team in collaboration with members of advisory committees that were convened in each regional case, informed by literature on climate change communication and engagement. The interview guide contained five main sections to elicit rich descriptions and meaning in relation to study objectives but deviated from the guide as appropriate (See Supplementary material). The sections of the interview guide encouraged discussion of climate change-related work in the context of their community/region, explorations of existing patterns of understanding and engagement in their community/region, challenges and successes in communication, perspectives on place-informed communication strategies, and demographic questions. The guide was pilot-tested for clarity. Interviews were conducted by two researchers (Galway and Gislason) between May and October 2018, lasted between 45 and 90 min and were audio-recorded. Written consent was obtained from participants prior to interviews.

We transcribed interviews verbatim and offered transcripts to the participants for verification. One specially trained research assistant entered transcripts into NVivo11 software for initial inductive analysis whereby transcripts were read, reviewed and interpreted and first level coding was conducted which looked for a priori concepts derived from the interview guide. Emerging themes were discussed among the research team to verify that the analysis accurately captured participants’ experiences and all team members contributed to subsequent stages of analysis.

Limitations

Our sample was diverse; however not fully representative of populations in the provincial north. For example, half of the respondents identified as women, three participants were Indigenous and even fewer participants identified as youth or elderly (). We did not collect demographic information to identify further intersections of identity such as race and ethnicity, social economic status or identification as LGBTQ2SI. Future research will pay more nuanced attention to how discourses and actions can be developed in ways that reflect the experiences of a range of diverse populations and will foreground decolonizing processes within the CPN. To strengthen the findings of this study, more research is needed to test the applicability of the recommendations to other northern provincial contexts in Canada.

Results

This section reports on the findings from interviews with climate champions, highlighting key insights that focus on the importance of place and consideration given to the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of citizen engagement in these particular contexts.

Understanding and appreciating place: the CPN context

We began our interviews by asking climate champions to describe the places in which they undertake their climate change-related work. Key characteristics used to describe place included remoteness, a sense of community, influence of local economies, and direct experience with the impacts of climate change.

Remoteness was often described by participants and framed not only as an experience of physical and geographical isolation, but also of social and political disconnection from urban life, for example, due to the concentration of decision-making in the provincial south.

So the North … it's far from everything … It's a challenge to get staff in those Northern communities, so you generally don't have the best services. From a landscape perspective, winters are really long, the roads are hit and miss, there are often closures because of snowstorms, landslides … . (BC participant J)

The CPN is constituted by numerous Indigenous territories where the longstanding engagement of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples is to cultivate sustainable social-ecological relationships that are rooted in care for place:

I think First Nations in the North, in BC … are absolutely in a leadership role when it comes to land use planning and decision making. Increasingly so, increasingly assertive and increasingly important in those conversations and I think that climate change mitigation, climate change action will have to be integrated into their decision-making and their priorities if we're going to see success on the ground in the region. (BC participant H)

Pride of place, a strong sense of belonging, and an active appreciation of community and the natural environment were all recurring considerations.

People here are unique, they’re committed to the area, people are committed to each other … So there is a real sense of community despite the transient population. (ON participant 6)

Connection to place and approaches to stewardship were influenced by participants’ social locations, length of time living and working in the CPN, and settler or Indigenous identity. Community connectedness was also tied to a sense of investment in the stewardship of the natural environment. As one participant described:

“We’re a pretty tight knit community, everybody seems passionate about projects, like climate change or source water protection, everybody wants to see good things happen here” (ON participant 3).

Interviewees noted direct and indirect impacts of climate events experienced in the CPN, which they often described in relation to connection to the land, attention to changes in weather patterns, wildlife or the impacts of natural disasters.

I know from talking to people that they've actually felt the results of what they perceive to be climate change in some of their seasonal activities like fishing. They've noticed changes in where they can get fish and in some of their outdoor activities. The snowpack comes later and leaves sooner and is lower. (BC participant B)

Reflecting on participant’s descriptions of life in the CPN cultivates an understanding of the particular landscapes within which climate champions are engaging in conversations about climate change.

Challenges of working on climate change in the CPN

When building an evidence-based approach to identifying effective strategies for constructing narratives and action-oriented agendas, it is imperative to consider the impact of distinct characteristics of the CPN. Confirming findings in the literature, climate champions often spoke of the “forgotten north” which they further characterized as having limited economic options, political marginalization and remoteness. Participants also spoke to assets and strengths, including its relative size and resourcefulness. Also, the features that some participants viewed to be strengths were thought of by others as weaknesses, pointing to a characteristic tension in the CPN where opposing viewpoints often co-exist, reflecting the diversity of people who navigate these landscapes and experiences of ongoing provincially disproportionate under-resourcing in the region.

Participants often commented on marked differences between the economic and social drivers in the CPN as compared to the south of provinces and suggesting both province’s economic reliance on the resource sector, and the social and environmental impacts of that reliance, is often underappreciated in the south. For example, CPN economies are prone to cyclical “booms and busts” leaving communities vulnerable to economic slowdowns as well as contending with social and environmental impacts to natural resource exploration, extraction and sales. As participants described:

In the boom times … the hotels and camps will be filled and in the tough times it’s empty. And even in the five years I've lived there, I've seen boom and bust happen like three times. Unemployment going from the lowest in Canada to nine, ten, thirteen percent in a matter of 18 months and I think that's the real wheel around which a lot of these communities sort of spin. (BC participant H)

It’s hard to talk about climate change in isolation from so many other issues going on. Economies always seemed to trump the environment, and locally because we have a struggling steel plant right now, most of the focus is on the struggling economy, not on environmental issues. (ON participant 10)

Given the central role that extractive industries play in the lives of many families, young adults, (particularly men) may choose to obtain an industry job in order to carry on a family tradition or obtain lucrative work with only a high school education. One participant stated: “I think education [is a challenge]; a lot of people don’t have their grade 12 or GED. A lot of people don’t have their driver’s license, which inhibits a lot of job opportunities” (ON participant 3). Overall, the tight coupling of industry with job opportunities, educational strategies and community and family livelihoods contours the conditions within which conversations on climate change are taking place. As another participant noted: “you can propose anything as long as it doesn't threaten an industrial, extractive growth economy” (BC participant J).

Given that much of the economy in the CPN is supported by resource extraction, it is challenging to communicate about climate change if it is perceived to threaten job security or community stability. When climate change is acknowledged, the hope is that there will be technologically driven solutions to enable industries to continue to operate:

One of the challenges of doing climate change work up here is just that the discourse is overwhelmed by thoughts about how technology or technological interventions can help us mitigate and adapt to climate change. And that is … a challenge because it's such a part of … popular media and people eat it up because they're kind of enamoured with the idea of just a quick fix or something you can build or something you can mine and then build and then something that you can deploy. (BC participant B)

Lessons for communication and engagement from CPN “climate champions”

In this section, we discuss four key lessons from climate champions about effectively communicating about climate change in the CPN.

Building messages and strategies around local values and place

CPN climate champions shared the importance of communicating with people about the places to which they feel connected as well as how effective it is to draw on their own lived experiences and their knowledge of the experiences, skills, and perspectives of the people with whom they are speaking.

Since connection to landscapes, ecosystems and the broader environment is a common value, climate champions emphasized that linking messages to these aspects of life in the CPN, such as the seasons and outdoor activities, is an important strategy. This is especially true for highlighting how climate change impacts the places where people live as well as rely on for recreation, employment, and subsistence. As one interviewee shared: “I can just go out my back door and go on the walking trails with my dogs, it connects right up with the TransCanada trail” (ON participant 8). People also reflected on how to leverage this attachment to place and on the effectiveness of strategies they have used:

Show people a doctored image of Mount Robson with no snow or ice on top of it and say, “this is what this is gonna look like in 50 years” … Because … people need to see the connection, they need to see the impact of what's going to happen, but does that mean that once we see it, we're just going to be more comfortable with it? More complacent about it … “Yeah, yeah, yeah. That would be really too bad, but there it is without ice. I guess I could live with that.” But [then ask] “What would that mean for the … valley [if there] are severely decreased flows through the Fraser River … .” (BC participant C)

Participants also reflected that effective communication could benefit from linking historical and current shifts in climate patterns and making observations about their impacts to the land locally:

… we stop and we say, “so what have you been seeing locally that you think might have been connected with climate change?” Oh my God, the stuff we get from that is so rich. Everything from “Yeah, you know, there's these like new beetles in my garden” to “we don't get snow the way we used to, I use to be able to jump off the roof into a snowbank, … to the birch trees are disappearing across this whole band of elevation.” It's just the variety of things that people are seeing once you give them a forum to talk about it, a safe one, and that's part of it too, you got to create a safe place. (BC participant F)

Participants realized that place-based connection precipitates a more thoughtful engagement with the tensions that arise when the issues are framed as “environment vs. economy” because it creates opportunities to identify reciprocal relationships in the CPN between these domains. The importance of highlighting solutions that have co-benefits: they are good for the climate as well as for the environment, were also discussed as entry points for people as they saw how change can be supportive of local economies.

The importance of Indigenous knowledges and leadership

The forces that contour place and relationships are multiple and change over time. New governance, jurisdictional and collaborative opportunities are emerging in conjunction with ongoing colonial and extractive dynamics that continue to impact rural, remote, northern and Indigenous communities in Canada. Both Indigenous and non-indigenous climate champions called for Indigenous-led engagement in conjunction with, and involving support from, settler communities.

A notable perspective that emerged from interviewees is that climate change can be best understood in the CPN through the integration of Western science and traditional Indigenous knowledge, reflecting the importance of Two-Eyed Seeing (Marshall et al. Citation2015) approaches, with one participant saying: “I find it’s always interesting to blend traditional knowledge and science because the traditional knowledge, they [Indigenous Peoples] are the ultimate climate watchers” (BC participant I). Given their deep traditional knowledge of place, others felt that Indigenous peoples should play important leadership roles in responding to climate change: “So Indigenous People: can they lead us? Yes. Do they have things to offer? Absolutely, but it’s not all on them. We need to do lots beside them, hand in hand” (ON participant 7).

Many participants highlight that respect for, and incorporation of, traditional Indigenous knowledges have a great deal to offer communication and engagement frameworks. The use of storytelling, for example, resonated with many people in the CPN:

At one of the workshops we had, there was one Elder who had a couple stories and it really got people engaged … talking about how he used to hunt and gather and now he can’t do the things he used to do … It makes it more heartfelt instead of listening to some scientist ramble on with numbers and data. (ON participant 3)

Discourses of urgency, hope, and practical solutions

In addition to connection to place and the importance of collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders, leaders, and worldviews, climate champions interviewed also suggested that stories and information help people connect emotionally with climate issues.

One of the most successful lessons is when I give a personal situation from someone around the world and how it's affected them, like a farmer in Bangladesh or like someone over here … And then it’s a personalized story, that's one of the best teaching tools in no matter what subject. (ON participant 11)

I find stories that people can engage with and see direct relevance are much stronger than saying, “well, you know, the scientific facts is 420 parts per million … ” That just doesn't work, but stories really work. (ON participant 12)

The thematic focus on sharing messages of urgency, hope and practical solutions also emerged with specific guidance that: (a) urgency is important, but should veer towards hope rather than despair; (b) hopeful stories are those that exemplify local successes or highlight local assets; and (c) local stories resonate with local people and increase relatability. Incorporating aspects of the diverse places, cultures and identities of CPN communities through story and other creative and accessible mediums is paramount to building effective communication and engagement strategies.

Many participants were advocates of communicating about climate change in ways that offer hope.

Simply put, people have enough negativity in their lives, especially living in [name of community], a depressed community with so little sunlight and still lots of cold to go. People are looking for something positive, and … to get engaged in something of hope. (ON participant 6)

Conveying urgency was also identified as a potent motivator, while acknowledging that it is challenging but necessary to communicate urgency alongside hope.

… keep people hopeful, but what I still think people are really looking for is what can they do, right. And if what they do can have effects for their family, or effects for their community, or their country, or region of the globe, or the whole globe I think that’s really important for them to understand, what can they do. (ON participant 4)

In some cases, this looked like shocking people into concern with facts on climate change impacts, and following up with solutions and actionable steps to mitigating the issue:

I think those negative impacts are where people actually are engaged on climate change in the region. (BC participant H)

Some people feel invigorated or mobilized by knowing something negative is happening and they want to respond, other people don't so … it’s a tricky thing to try and convince the general public of stuff because they probably have different pain points. (ON participant 2)

Practical, accessible, personalized communication

Visuals and good storytelling were commonly identified as effective tools for communicating about climate change as they bring issues closer to home and humanize them. “I think visuals are important for conveying any information to people” (ON participant 2). Relatedly, it was felt that communication strategies have the most impact when grounded in place and the sense of meaning it invokes.

North life's a bit more of a struggle. And so since it's a struggle, they only have so much energy and so they want to make sure that they're putting energy into things that are going to result in something, but they also want to be putting energy into something that matters. (BC participant G)

Participants noted scientific information and information about climate impacts were best shared through stories told by effective storytellers:

On my radio show … we have two big criteria: is it a good story – and there are lots of good stories out there – and the other is, is this a good storyteller. And my producers go to a lot of trouble to find scientists who can speak well, and very often a third of the people we call up, they don’t make it to air, because either they can’t get away from the jargon or they just can’t put it together in an understandable way. So good storytelling is to make it interesting. (BC participant I)

Several participants recommended that stories connect climate change to the realities of people’s lives. As one person described: “One of the most successful lessons is [to give] … a personalized story, that's one of the best teaching tools in no matter what subject” (ON participant 11) Further, drawing examples from their personal lives in order to open conversations can be an effective engagement technique. One respondent said they utilized stories about building a car that runs on vegetable oil as a conversation starter:

For four years, my car, my little diesel, I drove on vegetable oil from the University campus waste oil and it was just such an inside way to talk to people. So if I did run into a conservative guy, I didn't even tell him about the greenhouse gas that I saved, but I told him how much money I saved and he was still fascinated. If it was the green person then, “Oh yeah, four tons of carbon reduced” and I haven't paid for gas on the highway in a year … I had so many conversations with people I wouldn't have because of that car alone. (BC participant E)

Participants emphasized the importance of profiling solutions that are relevant and feasible within the CPN. Many participants described that most of the climate change solutions available/prioritized by decision-makers and governments at this stage come from large urban centers rather than being developing with the CPN in mind or in concert with people with lived experiences of the CPN:

Part of being authentic, is being able to speak to actual things that have worked as well. So, in [community] showing that solar hot water is working even in the middle of winter, that's something that people just can't get their head around. But now that is not just the city, but [Name of First] Nations and others have used that, they're like, “wow, really, we’ll have to look into that” … So, something has got to be proven before we adopt it for sure. (BC participant E)

The high stakes climate context of the CPN, including the consequences of transitioning away from certain economic practices and the small margin of error that is created by living in the harsh climate and remoteness of the CPN, need to be considered. Here, climate champions emphasize solutions that are practical and relevant.

Discussion

This study draws attention to distinct characteristics of the CPN and related climate change communicative challenges and opportunities and offers novel insights into how climate champions practice communication in these contexts. People in the CPN do not deal with the impacts of climate change in the abstract; rather, their reliance and interaction with the environment for housing, food, work, and recreation directly exposes them to climate change impacts. This finding reflects Schweizer et al.’s (Citation2013) suggestion that climate narratives have their strongest appeal when: (1) located in a community’s cultural values and beliefs; (2) meaningful to that community; and (3) leading to specific political actions.

Using knowledge and insights related to community contexts enables climate champions to communicate in place-based, relevant and relatable ways, underscoring related efforts that highlight the complexity and nuance of interacting climate and environmental change in the CPN (Gislason et al., Citation2018; Picketts et al., Citation2020). Climate champions used techniques including storytelling and other visual and creative modalities, enabling them to balance the science of climate change with messages about direct impacts to people’s lives. Care was also taken to communicate both about urgency and hope (Ojala, Citation2012) and relatedly about of agency (willpower) and purpose (waypower) (Li & Monroe, Citation2017). Place-based theories emphasize that messages will resonate with diverse audiences when they empower specific, relevant actions (Schweizer et al., Citation2013). For example, invoking images of local places and landmarks, demonstrating the impact of climate change on valued community practices/beliefs, connecting to Indigenous land stewardship initiatives, protecting recreational destinations and identifying hazards and their economic impacts.

Our research extends the work of Lorenzoni et al. (Citation2007), who theorizes upon the interconnected cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of communication strategies by highlighting the importance that messaging be informed by context and place and promote forms of hope that generate action such as “grounded hope” (Stoknes, Citation2015) or “constructive hope” (Ratinen & Uusiautti, Citation2020). Grounded hope is rooted in a realistic understanding of the current state of affairs, is skeptical of a positive outcome, yet manifests as active engagement with the issue as inaction is considered unacceptable and unethical (in Moser & Berzonsky, Citation2017). Grounded hope in this research extends to include the notion of being grounded in place-based realities, values and opportunities. While place-based approaches may be newer to “settler colonial science” they are essential to Indigenous worldviews, cultures, stewardship practices, health and wellness and governance frameworks (Redvers, Citation2018). In this research, Indigenous people’s knowledge of climate change impacts, capacity to teach and inspire through storytelling and deep understanding of the interconnection between people and the land was strongly admired by both settler and Indigenous participants.

CPN climate champions emphasized that climate-related problems and their solutions need to be defined in ways that reflect the realities of living in rural, remote, northern and Indigenous communities. Participants highlighted how urban-centric recommendations reinforce a sense that they live in the “forgotten north” and this can fuel feelings of alienation and disenfranchisement. In interviews, many countered some of the stereotypes, including of climate denial, by highlighting activities that people are engaged in ranging from walking, bicycling or roller blading to work and school; increasing the number of electric vehicles and decreasing diesel engine vehicles on the road; adding more electric vehicle charging stations in northern urban centers; promoting more local food production; eating plant-based diets; and decreasing dependence on wood fiber fuel for warming houses.

Our research also reinforces that climate communication research should involve a focus on “objects of care” (Wang et al., Citation2018). People who can identify what they care for and wish to protect tend to “feel more strongly about the issue than others” demonstrating the role that emotions can play in precipitating action (Wang et al., Citation2018). Connection to land and wilderness is a widely shared object of care in the CPN and incorporating landscapes and landmarks into stories about climate change is poignant.

Social vulnerability and strengths combine in climate change communication, particularly in relation to notions of urgency and capacity to change. The existence of intersecting social risk and vulnerability factors in the CPN can generate a hierarchy of needs and priorities in people’s lives and include immediate issues around job security, housing, accessing health care and other services (Coates et al., Citation1992). Even so, the immediacy of climate change is increasingly experienced as a real and present danger for people. Climate champions identified opportunities to illustrate how large scale ecological and social systems interact, and how to promote resilience at the interface of such interactions. Yet, given the highly political and politicized nature of climate change in the CPN, people who actively communicate about climate change can feel, and even become, socially alienated. A meta silence around climate issues deepen when they are approached as global issues and little regional data, evidence, and research is used to locally ground both the problem of and solutions to climate change. These findings support those from related research where climate change concerns are framed alongside interrelated resource extraction issues, creating new opportunities to explore alternative approaches and possibilities within CPN contexts (Picketts et al., Citation2020). Framed another way, climate communication should seek to promote the assets and unique local adaptive capacities of people and places in order to resonate with communities, rather than focus disproportionately on detrimental models of vulnerability (Buse & Patrick, Citation2020).

The power of practicality also emerged as a theme for many climate champions interviewed, as they shared that people are more likely to be receptive to making changes if there is also infrastructure being offered. Examples include: green jobs, funding for climate action, the opportunity to recycle, increasing the feasibility of driving an electric car, and funding available to retrofit or build passive houses. Champions noted the attachment to the resource extraction sector in the CPN sometimes also reflects direct and indirect reliance on industry jobs across generations. Until jobs are available that are not tied so closely to these industries, people will continue to easily justify the industries’ existence and the intergenerational tradition of their participation in them. The notion, therefore, of a “just transition” (Agyeman, Citation2008) – particularly for workers in extractive industries and communities dependant on resource dollars – is important. Active engagement with just transition discussions may open up conversations that could lead to shifts in values and increased support for climate action through fostering interest in new economic opportunities, even if they are tied to existing industries, which people continue to be dependent upon for their livelihoods and identities. That said, concepts such as “just sustainabilities” (Agyeman, Citation2008) were challenged by some participants, who questioned the feasibility of “green jobs” and whether there is sufficient money in things like environmental remediation, natural conservation and stewardship. This resonated with findings by Picketts et al. (Citation2020) who underscore the importance of going beyond the logic of oppositional narratives to climate change to foster new placed-based strategies to address these tensions.

Generally, the impacts of climate change on Canadian women, visible minorities, and people with a range of diverse identities is little studied and understood with the result that communication strategies are difficult to tailor to these groups (Moser & Dilling, Citation2011). Place-based theory also suggests that messages “will resonate with diverse audiences” when grounded in the cultural values, beliefs (Schweizer et al., Citation2013) and experiences of local people. Gender and other identity factors shape a range of important factors – from a group’s sense of connection to the natural environment and differing economic ties to the resource extraction industry, through to their sense of belonging within community. Indeed, in this study, no climate champion interviewed believed that increased knowledge of climate science alone leads to effective action. Rather, champions talked about values, the unique contexts of their communities and how an understanding of these factors can foster communication that can build connection to the issues and therefore catalyze action.

While mainstream climate change communication offers some common wisdom applicable to the CPN, many recommendations will need to be reframed so that they can be adapted to the unique features of local contexts including the social, economic, political and geographic factors shaping the realities in which people live, work, and take action on climate change. Therefore, a nuanced understanding of place and relationship to place is linked to affective and behavioral dimensions to climate change as the values, history, land, and cultures alive in a place are important to climate change communication theory and practice.

Conclusion

This paper offers new insights into the complex challenges of communicating about and engaging people in addressing climate change in the CPN. Working in the tensions between activating both individual, collective, and institutional actions, climate champions have experienced the limits to the efficacy of the knowledge-deficit model of communication (Ballantyne, Citation2016; Fiske, Citation2002; Moser, Citation2014). Instead, we have found that nuanced, place-based communication with local people is most effective when it uses stories, visuals and practical examples which speak to pre-existing values, preferences, beliefs, norms and experiences of locals in ways that highlight relevance to their own communities, lifestyles and day-to-day lives. This approach confirms Lorenzoni et al.’s (Citation2007) research on the importance of the interconnection of the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of citizen engagement around climate change.

Examining what climate change means for people in specific places, “situates” experiences, and foregrounds people-place relationships. This research reflects the theoretical foundations of place-based approaches which acknowledge that climate change is experienced locally and that responses are shaped by homegrown relationships and regional contexts (i.e. social, cultural, economic, and ecological characteristics that define unique places). Through understanding how place, space and people inform climate change communication strategies this paper argues that considerations of local and regional context in climate communication approaches are needed to effectively activate and strengthen citizen engagement. The overarching insight offered is that context “really does matter” and that communication and engagement should be informed by, and grounded in, place-based knowledge, experiences, and priorities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agyeman, J. (2008). Toward a “just” sustainability? Continuum, 22(6), 751–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310802452487

- Ballantyne, A. G. (2016). Climate change communication: What can we learn from communication theory? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(3), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.392

- Buse, C. G., & Patrick, R. (2020). Climate change glossary for public health practice: From vulnerability to climate justice. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74(10), 867–871. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-213889

- Buse, C. G., Poland, B., Haluza-Delay, R., & Wong, J. (2019). “We’re all brave pioneers on this road”: Climate change adaptation activities among public health units in Ontario, Canada. Critical Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1682123

- Coates, K., Holroyd, C., & Leader, J. (2014). Managing the forgotten north: Governance structures and administrative operations of Canada’s Provincial Norths. Northern Review, 38, 6–54. https://thenorthernreview.ca/index.php/nr/article/view/324

- Coates, K. S., Morrison, B., & Morrison, W. R. (1992). The forgotten north: A history of Canada's Provincial Norths. James Lorimer & Company.

- Coates, K., & Poelzer, G. (2014). The next northern challenge: the reality of the provincial north. A Macdonald-Laurier Institute Publication. https://www.macdonaldlaurier.ca/files/pdf/MLITheProvincialNorth04-14-Final.pdf

- Costello, A., Abbas, M., Allen, A., Ball, S., Bell, S., Bellamy, R., & Lee, M. (2009). Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute for global health commission. The Lancet, 373(9676), 1693–1733. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1

- Czyzewski, K. (2011). Colonialism as a broader social determinant of health. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2011.2.1.5

- Devine-Wright, P. (2013). Think global, act local? The relevance of place attachments and place identities in a climate changed world. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.08.003

- Döring, M., & Ratter, B. (2018). The regional framing of climate change: Towards a place-based perspective on regional climate change perception in North Frisia. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 22(1), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-016-0478-0

- Dryzek, J. S., Norgaard, R. B., Schlosberg, D. (Eds.). (2011). Communicating climate change: Closing the science-action gap. In The Oxford handbook of climate change and society (pp. 161–174). Oxford University Press.

- Fiske, J. (2002). Introduction to communication studies. Routledge.

- Galway, L. P. (2019). Perceptions of climate change in Thunder Bay, Ontario: Towards a place-based understanding. Local Environment, 24(1), 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2018.1550743

- Galway, L. P., Buse, C., Gislason, M., & Parkes, M. W. (2020). Perspectives on climate change in Thunder Bay: Findings from a community survey. Lakehead University.

- George, C., & Reed, M. G. (2017). Operationalising just sustainability: Towards a model for place-based governance. Local Environment, 22(9), 1105–1123. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2015.1101059

- Gislason, M. K., Morgan, V. S., Mitchell-Foster, K., & Parkes, M. W. (2018). Voices from the landscape: Storytelling as emergent counter-narratives and collective action from northern BC watersheds. Health & Place, 54, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.08.024

- Groshong, L., Stanis, S. W., Morgan, M., & Li, C. J. (2019). Place attachment, climate friendly behavior, and support for climate friendly management action among state park visitors. Environmental Management, 65(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-019-01229-9

- Groulx, M., Lewis, J., Lemieux, C., & Dawson, J. (2014). Place-based climate change adaptation: A critical case study of climate change messaging and collective action in Churchill, Manitoba. Landscape and Urban Planning, 132, 136–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.09.002

- Halperin, A., & Walton, P. (2018). The importance of place in communicating climate change to different facets of the American public. Weather, Climate, and Society, 10(2), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-16-0119.1

- Hu, S., & Chen, J. (2016). Place-based inter-generational communication on local climate improves adolescents’ perceptions and willingness to mitigate climate change. Climatic Change, 138(3–4), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1746-6

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2014). Food Security and Food Production Systems. In Climate Change 2014 - Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects: Working Group II Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (pp. 485–534). Cambridge University Press.

- Khadka, A., Li, C. J., Stanis, S. W., & Morgan, M. (2020). Unpacking the power of place-based education in climate change communication. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533015X.2020.1719238

- Krauß, W., & Bremer, S. (2020). The role of place-based narratives of change in climate risk governance. Climate Risk Management, 28, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2020.100221

- Kukucha, J. (2016). Provincial/territorial governments and the negotiation of international trade agreements. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://irpp.org/research-studies/insight-no10/

- Landriault, M. (2020). Media, security and sovereignty in the Canadian Arctic. Routledge. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/10.4324/9780367816292

- Li, C. J., & Monroe, M. C. (2017). Exploring the essential psychological factors in fostering hope concerning climate change. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 936–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1367916

- Leiserowitz, A., Smith, N., & Marlon, J. R. (2010). Americans’ knowledge of climate change. Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. https://environment.yale.edu/climate-communication-OFF/files/ClimateChangeKnowledge2010.pdf

- Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S., & Whitmarsh, L. (2007). Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change, 17(3–4), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.004

- Marshall, G., Bennett, A., & Clarke, J. (2018). Communicating climate change and energy in Alberta – Alberta narratives project. Climate Outreach.

- Marshall, M., Marshall, A., & Bartlett, C. (2015). Two-eyed seeing in medicine. In M. Greenwood, S. de Leeuw, & N. M. Lindsay (Eds.), Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: Beyond the social (2nd ed., pp. 16–24). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Moser, S., & Berzonsky, C. L. (2017). Hope in the face of climate change: A bridge without railing. http://susannemoser.com/documents/Moser-Berzonsky_Hopeinthefaceofclimatechange_reviewdraft_6-24-15.pdf

- Moser, S. C., & Dilling, L. (2011). Communicating climate change: closing the science-action gap. In J. S. Dryzek, R. B. Norgaard, & D. Schlosberg (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society (pp. 161–174). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.003.0011

- Moser, S. C. (2014). Communicating adaptation to climate change: The art and science of public engagement when climate change comes home. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(3), 337–358. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.276

- Moser, S. C., & Ekstrom, J. A. (2010). A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(51), 22026–22031. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1007887107

- Nicol, H. N. (2017). From territory to rights: New foundations for conceptualising indigenous sovereignty. Geopolitics, 22(4), 794–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2016.1264055

- Nicolosi, E., & Corbett, J. B. (2018). Engagement with climate change and the environment: A review of the role of relationships to place. Local Environment, 23(1), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1385002

- Ojala, M. (2012). Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environmental Education Research, 18(5), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.637157

- Ostry, A., Ogborn, M., Bassil, K. L., Takaro, T., & Allen, D. M. (2010). Climate change and health in British Columbia: Projected impacts and a proposed agenda for adaptation research and policy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(3), 1018–1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7031018

- Parlee, B. L. (2015). Avoiding the resource curse: Indigenous communities and Canada’s oil sands. World Development, 74, 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.004

- Picketts, I. M., Dery, S. J., Parkes, M. W., Sharma, A. R., & Matthews, C. A. (2020). Scenarios of climate change and natural resource development: Complexity and uncertainty in the Nechako Watershed. The Canadian Geographer, 64(3), 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12609

- Pulver, S., Ulibarri, N., Sobocinski, K. L., Alexander, S. M., Johnson, M. L., McCord, P. F., & Dell'Angelo, J. (2018). Frontiers in socio-environmental research: Components, connections, scale, and context. Ecology and Society, 23(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10280-230323

- Ratinen, I., & Uusiautti, S. (2020). Finnish students’ knowledge of climate change mitigation and its connection to hope. Sustainability, 12(6), 2181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062181

- Redvers, N. (2018). The value of global Indigenous knowledge in planetary health. Challenges, 9(2), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe9020030

- Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2013). Personally relevant climate change: The role of place attachment and local versus global message framing in engagement. Environment and Behavior, 45(1), 60–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916511421196

- Schweizer, S., Davis, S., & Thompson, J. L. (2013). Changing the conversation about climate change: A theoretical framework for place-based climate change engagement. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 7(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2012.753634

- Simms, C. D. (2016). Canada’s Fort McMurray fire: Mitigating global risks. The Lancet Global Health, 4(8), e520. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30132-2

- Southcott, C. (2014). Socio-economic trends in the Canadian north: Comparing the provincial and territorial norths. Northern Review, 38, 155–173. https://thenorthernreview.ca/index.php/nr/article/view/330

- Statistics Canada. (2016). Census profile, 2016 census. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

- Stoknes, P. E. (2015). What we think about when we try not to think about global warming: Toward a new psychology of climate action. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Sturgis, P., & Allum, N. (2004). Science in society: Re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 13(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662504042690

- Wang, S., Leviston, Z., Hurlstone, M., Lawrence, C., & Walker, I. (2018). Emotions predict policy support: Why it matters how people feel about climate change. Global Environmental Change, 50, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.03.002

- Watts, N., Adger, W. N., Agnolucci, P., Blackstock, J., Byass, P., Cai, W., & Cox, P. M. (2015). Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. The Lancet, 386(10006), 1861–1914. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6

- White, G. (2020). Indigenous empowerment through co-management: Land claims boards, wildlife management, and environmental regulation. University of British Columbia Press.

- Wibeck, V. (2014). Enhancing learning, communication and public engagement about climate change – some lessons from recent literature. Environmental Education Research, 20(3), 387–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.812720

- Wilson, G. N., & Poelzer, G. (2005). Still forgotten? The politics and communities of the Provincial Norths. Northern Review, (25/26), 11–16.