ABSTRACT

The development of the circular bioeconomy is perceived as important in the transition to a low-carbon economy. Its success depends on systemic changes involving all societal actors with public perception being of central significance. Using content analysis, this paper explores the framing of the circular bioeconomy in the Irish broadsheet media during the period 2004–2019. The results indicate that the development of the circular bioeconomy in Ireland has been framed in largely informational terms. The paper concludes that Irish broadsheet media coverage should widen in scope to reflect the multi-sectoral nature of the circular bioeconomy and be more critically incisive in its approach. It argues that the media should also be less uncritical in its acceptance of the top-down discourse on the circular bioeconomy economy that has been presented by government and industry.

1. Introduction

While many EU countries have attempted to reduce their dependence on fossil fuel and move to a new, low-carbon economy, Ireland has so far failed to implement significant policies and measures which would lead to achievement of its 2020 targets for radical reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (EPA, Citation2019). Moreover, as the Government’s own Climate Change Advisory Council has asserted, Ireland on its present course will miss the proposed 2030 EU decarbonisation targets (CCAC, Citation2019). Among a range of measures recommended by the Council in 2018 was the phasing out of peat and coal for power generation and the urgent implementation of decarbonisation measures in Ireland’s agriculture sector (CCAC, Citation2019). New agricultural production methods and fuels are therefore required; the innovative use of bioresources in what is termed the bioeconomy can occupy a pivotal role in any transition to a low carbon economy (Hausknost et al., Citation2017).

The bioeconomy includes not only agriculture and food production but also extends to forestry and fisheries as well as parts of the chemical, biotechnological and energy industries (EC, Citation2012; EC, Citation2018). The concept is closely aligned with the circular economy. Indeed, it has been suggested that both concepts could be fully integrated as the “circular bioeconomy..” Despite this being the subject of some contention (D'amato et al., Citation2019), the European Commission’s updated Strategy for the Bioeconomy, published in October 2018, makes explicit reference to it throughout the document (e.g. “Delivering a sustainable circular bioeconomy” (p. 16)).

It is perhaps in its role in reducing the economy’s dependence on depleting fossil fuel resources, and consequently mitigating and adapting to the increasing threat of global warming associated with climate change, that the transition to the bioeconomy has most significance. Furthermore, the concept of a “just transition” which does not further disadvantage communities and workers previously reliant on unsustainable energy sources is becoming increasingly prominent within political discourse (Piggot et al., Citation2019). For such a transition to be achieved systematic changes involving society, governments and industry will be necessary.

However, it has been asserted that crucial acceptance of the bioeconomy could be denied if policies do not engage with societal debates on agriculture and food (De Besi et al., Citation2015; Meyer, Citation2017). The economic and societal implications of the bioeconomy require sustained attention by policymakers. Indeed, the successful transition to a bioeconomy requires that policymakers across a range of sectors understand how coherence of public policy can contribute, or create barriers, to its development (Kelleher et al., Citation2019). Moreover, it is important that public perception of the bioeconomy is not governed by a perceived imbalance in the importance given to technology and science-based concepts to the detriment of socio-political considerations (Bugge et al., Citation2016; Hausknost et al., Citation2017). Recent research has indicated that citizens were primarily concerned with the feasibility of the concept of the bioeconomy and the potentially negative financial consequences of reduced economic growth or lack of jobs (Stern et al., Citation2018).

There are many studies investigating the role of media framing in areas related to environmental policy (Boykoff, Citation2013; Carvalho & Burgess, Citation2005; Devitt & O’Neill, Citation2017). The media provides a platform from which different actors can express their interests, whether political, social or regional. Media coverage can represent but also influence public awareness and attitudes to policy implementation. Moreover, the frequency and emphasis with which certain topics are reported can be pivotal in affecting policy decisions (Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017).

However, although the importance of engaging society in the bioeconomy, through valid and informative media reporting, has been the focus of some recent research in Finland (Mustalahti, Citation2018; Peltomaa, Citation2018) there is a paucity of research material on the relationship between the bioeconomy and the role of the media in the development of public consciousness and attitudes towards it. Furthermore, while the bioeconomy as noted by Peltomaa and Kolehmainen (Citation2017) is nothing new in countries with vast natural resources, such as Finland, the concept in Ireland has been much slower to gain traction. Consequently, how the media has covered the topic is significant and key to informing citizens’ initial awareness. The central aim of this paper is to therefore explore how the Irish broadsheet print media is reporting on and framing the purpose and scope of the circular bioeconomy in Ireland.

1.1. Ireland’s national policy statement on the bioeconomy

Ireland’s first National Policy Statement for the Bioeconomy (NPSB), released in February 2018, stressed the nation’s natural advantages as an actor in the European Bioeconomy. It pointed to Ireland’s temperate climate and the fertility of the soil which lead to a long growing season. Furthermore, approximately 10.7% of Ireland is currently under forest and it has one of the largest seabed territories in Europe with a direct economic value of €1.8 billion in 2016. In addition, the agri-food sector is Ireland's largest indigenous industry. The NPSB recognised the potential scope of the bioeconomy’s reach in four Strategic Policy Objectives (SPOs). A summary of each of the policy objectives is provided in .

Table 1. Ireland national policy statement for the bioeconomy: strategic policy objectives and potential benefits.

As with the EC Strategy for the Bioeconomy (EC, Citation2018), the NPSB acknowledges that Ireland’s bioeconomy has a close relationship with the circular economy through “solutions and innovations that reuse and recycle materials, maximising resource efficiency through the use of unavoidable wastes and environmental sustainability.” (Ireland, Citation2018, p. 10). Also in alignment with the EC Strategy for the Bioeconomy (EC, Citation2018) the NPSB makes explicit reference to the significance of awareness and understanding amongst key stakeholder such as consumers and citizens. The significance of societal awareness and understanding of the concept of the bioeconomy, and the importance of consumer engagement is highlighted in the EC Strategy for the Bioeconomy (EC, Citation2018). In addition, the political significance of the bioeconomy and achievement of the full range of SPOs in Ireland is highlighted by the fact that in the NPSB the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) makes clear that a central concern for the bioeconomy in Ireland is not only the promotion of more efficient use of renewable resources but the necessity of supporting economic development and employment in rural Ireland.

1.2. Study objective and research questions

The objective of this paper is to ascertain the nature and scope of broadsheet media coverage of the circular bioeconomy in Ireland. The case study was driven by three key research questions:

Research Question 1: How has the broadsheet media coverage of the development of the bioeconomy and circular economy been framed over the time period 2004–2019?

Research Question 2: Has there been alignment between aspects of the bioeconomy reported in the broadsheet media and the Strategic Policy Objectives outlined in the National Policy Statement for the Bioeconomy?

Research Question 3: Has there been alignment between aspects of the circular economy reported in broadsheet media coverage and the Strategic Policy Objectives outlined in the National Policy Statement for the Bioeconomy?

The paper continues as follows: the next section examines the definition of the bioeconomy; Section 3 discusses the representation of the bioeconomy in the Media; Section 4 describes the methods employed; Section 5 outlines the results; Section 6 discussed the findings and their implications; Section 7 outlines conclusions drawn from the findings.

2. Interpretations of the bioeconomy

A conclusive definition of the bioeconomy has not yet been established. In a political context, the bioeconomy is presented as an all-embracing multi-sector sustainable solution to a range of societal problems across Europe and in particular food security, natural resource security, fossil resource dependence, and climate change (EC, Citation2012). This vision has been recognised and enhanced in the updated EC Bioeconomy Strategy of October 2018 which posits a way forward by advancing the merits of a bio-based economy with sustainability and circularity as its central dynamic (EC, Citation2018).

An extensive literature review, undertaken by Bugge et al. (Citation2016) attempted to reveal definitively the nature and scope of the bioeconomy. The understanding of the concept provided by their findings posited the bioeconomy as multi-faceted in terms of origins and sectors. Each of the three visions of the concept which emerged from their review highlighted the significance of innovative development.

A bio-technology vision which focuses on the importance of biotechnology research and its application across different sectors;

A bio-resource vision, which emphasises the development of new value chains that process and upgrade biological raw material;

A bio-ecology vision that highlights ecological processes and sustainability.

An integral component of the concept of the bioeconomy is the importance of sustainability particularly in terms of the development of a circular economy by which raw materials, products and consumption are renewable (Devaney & Henchion, Citation2017; Woźniak & Twardowski, Citation2018). Although differentiated by approach, both the bioeconomy and circular economy are viewed as integral in the transition to a more sustainable and resource efficient economy (Carus & Dammer, Citation2018). Through this shared goal they can reinforce each other to discover innovative methods and technology for recycling and encouraging secondary material flows (EEA, Citation2018).

However, lest the development of a bioeconomy is interpreted as universally accepted as a completely beneficial approach to the solution of some of society’s key challenges, Kitchen and Marsden (Citation2011) pose a caveat in their critique of the emerging policy: “a technocratic and instrumental approach” with “a lack of social and local considerations.” The authors’ analysis presented the nature of the developing bioeconomy as representing corporate economic interests, global in scale, “rather than a locally embedded and value adding phenomenon.” The application of the bioeconomy has also been criticised for proceeding in a hierarchical fashion with its top-down solution to problems preventing recognition of the role of particular actors and of the potential for citizens’ participation in policy development (Davies et al., Citation2016; Mccormick & Kautto, Citation2013). Indeed, it is argued that the focus has been on attaining acceptance for the bioeconomy rather than providing a means to influence its development (Albrecht, Citation2019; Sleenhoff et al., Citation2015).

Further criticism of the validity of the bioeconomy as promulgated by the OECD (Citation2009) initiative is that it is essentially a political concept rather than simply an economic or technoscientific one (Goven & Pavone, Citation2015). It is posited that this bioeconomy concept does not address the underlying socio-political-economic causes of the problems which its biotechnologies will, allegedly, seek to ameliorate. Awareness of the economic and political power structures which institutionalise inequality and occlude potential democratic control should requisite acceptance of a valid bioeconomy narrative (Delvenne & Hendrickx, Citation2013; Goven & Pavone, Citation2015).

3. The bioeconomy: agenda setting and framing in the media

The bioeconomy is open to flexible interpretation of its definition and can be viewed from a range of different perspectives: those of business, government and public opinion. The media provides a forum by which interests, whether political, social, or regional, can be expressed by their different actors in the emergence of the bioeconomy. Public attitudes to the impacts of the implementation of policies can not only be represented in but are also influenced by media coverage (Cannon & Müller-Mahn, Citation2010; Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017). Policy decisions may be altered as a consequence of which topics receive frequency and prominence and, also, how these issues are reported – “framed” – in the press. It is helpful to differentiate between the two aspects of the reporting process: “agenda setting” and “framing” (Steger & Drehobl, Citation2018).

There is a long-established body of work around the theory of “agenda setting” (Cohen, Citation1963; Mccombs & Shaw, Citation1972). According to Marks et al. (Citation2007) it relates to the salience gained by issues because of the degree of emphasis they receive in the media. This focus on particular issues, Entman (Citation1991) argues, has direct influence on public perception of their significance. Aligned with the theory of agenda setting is the awareness that the media reporting of certain items of news can go beyond establishing their salience and directly affect public perception and engagement, particularly in the domain of science communication of innovatory practices (Coenen et al., Citation2015; Regan & Henchion, Citation2020). Clearly, such a process would be of pivotal importance to the public’s attitude towards the benefits and risks included in the transition to a bioeconomy.

The concept of framing connects to Kahneman and Tversky’s (Citation1979, Citation1984) work into how people’s choice of options can be affected by different forms of messages. Individuals rely on “primary frameworks” (Goffman, Citation1974) by which we are enabled to interpret the depth of information we experience on a daily basis. Effective communication relies on framing because it acts as a complement to the particular cognitive framework which governs individuals’ perceptions and responses to communication of information. Indeed, framing can be recognised as the process of selecting aspects of a societal perspective and presenting them textually in order to promote a desired communicative outcome in relation to the definition and interpretation of a particular problem (Entman, Citation1993). In the context of framing in the media, focus, selection and the significance of a topic are crucial to effective media framing of an issue (Entman, Citation1993). The selective dynamic can be implicit but importantly includes or excludes certain keywords, phrases or images, which leads to the legitimisation of ideas and attitudes within society (Entman, Citation1993). Effective media frames divert attention from alternative frames and focus on a particular aspect of content in the communication (Bayulgen & Arbatli, Citation2013). Media frames can reflect public opinion on a particular issue and consequently influence policy makers. Societal attitudes can also be influenced by scientific and economic framing adopted by policy makers and reported unchallenged in the media (Castrechini et al., Citation2014; Gamson & Modigliani, Citation1989).

The role of media actors as influential and controlling gatekeepers with the power to determine the admission and omission of issues on the media agenda, and consequently the public’s consciousness, has been posited (Graber, Citation2006). By framing policy issues and constructing narratives which provide the public with information in a succinct but engaging presentation, media actors can influence agendas and inform and change opinions (Mcleod et al., Citation2002). The evaluation of empathy and other emotions is a journalistic ploy which can induce media consumers to relate sympathetically to certain issues by shaping stories (Keller & Hawkins, Citation2009). This acceptance can occur even when the complexity and scope of the policy context is submerged in the construction of a human interest perspective (Iyengar, Citation1990). In this manner, by framing issues in an audience-centric manner or by communicating complex issues incompletely, media has the potential to influence not only the public but also policy makers’ comprehension of these concepts (Crow & Lawlor, Citation2016). Indeed, the methods by which certain issues are framed and expertise is communicated can have direct influence on the governance of natural resources (Böcher et al., Citation2009; Kleinschmit et al., Citation2009; Sadath et al., Citation2013).

As noted in Section 1.1 research material on the relationship between awareness of the significance of the bioeconomy and the role of the media in the development of public consciousness and attitudes towards it is limited. However, recently published research in Finland where more than half of the current bioeconomy is based on forests provides insightful findings on bioeconomy framing in the media (Mustalahti, Citation2018; Peltomaa, Citation2018; Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017). Amongst its conclusions, Peltomaa and Kolehmainen (Citation2017) asserts that the way that issues such as the bioeconomy are framed can bring about either support for or questioning of the legitimacy of the related policies. Framing is constructed by actors with different visions on how to make an optimal transition to a sustainable bioeconomy, and also with different views on which societal actors are deemed worthy of inclusion in that transition. Peltomaa (Citation2018) suggests that viability of the bioeconomy in the future might be compromised by the lack of roles for actor groups, such as citizens, in the framing of the bioeconomy promoted by the media. The media is highlighted as a key public arena where the adoption of a particular approach to the bioeconomy can raise support for or opposition to related policies and practices, while, also, highlighting issues relating to the motivations of the narrators. An interactive, collaborative approach to a responsive bioeconomy which would take into account citizens’ values was advocated by Mustalhti (Citation2018). This approach might include active participation by citizens in initiatives and panels and the involvement of elected representatives during planning processes.

Emphasis and tone when referring to aspects of the bioeconomy, while not necessarily intentional, may be reflective of how an article wants to represent certain interests, whether political, societal or regional (Kim et al., Citation2014). Consequently, this paper focuses on how the broadsheet media has attempted to inform the public and engage its interest through the nature and scope of its framing of the development of the circular bioeconomy.

4. Methodology

In order to explore the relationship between media framing and how it governs the portrayal of the circular bioeconomy in the Irish broadsheet media a content analysis was performed. Content analysis provides for a “systematic analysis of detecting meaning, identifying intentions and describing trends in communication content” (Bayulgen & Arbatli, Citation2013, p. 516). Due to the central role of communications in public policy, content analysis is applicable across a range of research areas (Devitt & O’Neill, Citation2017; Escobar & Demeritt, Citation2014; Schmidt et al., Citation2013; Wagner & Payne, Citation2017).

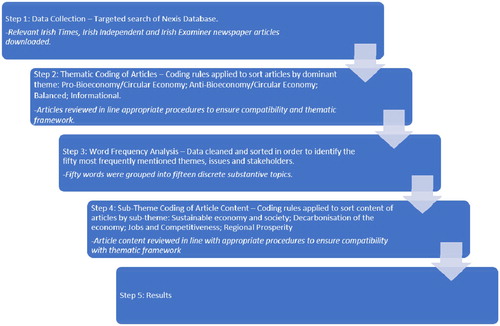

provides a methodological summary guide of the process involved in completing this research. Each of the steps involved is described in detail below.

4.1. Step 1 data collection

Ireland’s three major broadsheet newspapers were selected for use in this study. Broadsheet newspapers are most likely to be influential in terms of policy development (Carvalho & Burgess, Citation2005). The Irish Examiner (IE) circulated an average of over 25,000 copies, the Irish Times (IT) approximately 56,000 and the Irish Independent (IND) almost 85,000 in 2018 (Newsbrandsireland, Citation2019). The Irish broadsheets are broadly centrist, although Marron (Citation2019) suggests that The Irish Times orientation is more socially liberal and economically conservative, and describes the Irish Independent as being more pro-business. The Irish Examiner, based in Cork, provides a more regional perspective on issues. LexisNexis, the online newspaper archive database, was used to gather samples from each of the three newspapers using the search terms “bioeconomy” or “bio-economy” and “circular economy.”

Searches were customised according to the chosen newspapers and case study time period (2004–2019). This particular period was selected in order to identify any trends in the circular bioeconomy emerging before and after the 2008 Financial Crisis and included the period of the announcement of Ireland’s first National Bioeconomy Policy Statement in 2018. The 2008 financial crash had a significant impact on Ireland’s economy, particularly upon both regional and rural prosperity. The scope of the SPOs in Ireland’s NPSB illustrate the importance attached to the role that the bioeconomy can play in the rejuvenation of the nation’s economy and in particular regional and rural prosperity (See Section 1.2)

Articles were assessed for relevance to the aims of the research. Only articles which explicitly focus on the bioeconomy or circular economy concept or refer to the concepts in Ireland were included. A total sample of N = 132 newspaper articles were generated. It is recognised that although there is an intrinsic limitation on the scope of the study, it was decided that, due to the sheer number of derivatives of bioeconomy, such as bio-based products, bio-industries, bio-production, bio-fuels, bio-energy, bio-plastics etc to restrict the terms employed to those specified.

4.2. Step 2. Thematic coding of articles

In order to answer Research Question 1 (RQ1): How has the broadsheet media coverage of the development of the bioeconomy and circular economy been framed over the time period 2004–2019? a directed (deductive) qualitative content analysis approach was adopted to develop an appropriate thematic structure (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005; Macnamara, Citation2005) based upon a previous study of media framing in Ireland (Devitt et al., Citation2019) and other international studies (Culley et al., Citation2010; Wang et al., Citation2014). outlines the coding rules upon which the articles were sorted. In order to avoid possible duplication of articles and to maintain compatibility with the thematic framework and coding rules each article was read three times (Devitt et al., Citation2019).

Table 2. Themes and coding rules (adapted from Devitt et al., Citation2019).

Following this, it was determined whether the articles represented pro-circular/bioeconomy, anti-circular/bioeconomy, balanced or informational views. Those articles which revealed clear support for the circular/bioeconomy were categorised as pro-circular/bioeconomy while those which revealed clear opposition to the circular/bioeconomy were categorised as anti-circular/bioeconomy. Balanced articles tended to be more inclined to question the prevailing circumstances. However, it was found that informational articles, while not containing any clear pro or anti circular/bioeconomy material did contain some implicit pro-circular/bioeconomy content. Moreover, the majority of articles subscribing to the informational category were more expansive in content than those which would be designated pro- or balanced in relation to the concepts.

4.3. Step 3: word frequency analysis

In addition, with a view to identifying the sectors and topics related to the bioeconomy and circular economy in Ireland which have received most prominence in broadsheet media coverage over the 15-year period, a word frequency analysis was undertaken on each of the articles with the support of NVivo software. Insignificant words such as conjunctions and also synonyms of each word or term were omitted in order to identify the 50 most frequently mentioned themes, issues and stakeholders. Utilising the methodology employed by Peltomaa and Kolehmainen (Citation2017) the 50 words were then grouped into fifteen discrete substantive topics (see ).

Weightings and frequency of inclusion can reflect the approach by which a newspaper seeks to represent political interests, societal actors and regional priorities (Kim et al., Citation2014). The initial selection and the degree of salience attached, while perhaps unintentional and implicit, reveals the significance given to a particular topic by communicators (Entman, Citation1993; Gamson & Modigliani, Citation1987). Moreover, policy decisions may be affected as a consequence of those topics which receive the greatest frequency and prominence in the press (Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017).

4.4. Step 4: sub-theme Coding of Article content

In order to answer

Research Question 2 (RQ2): Has there been alignment between aspects of the bioeconomy reported in the broadsheet media and the Strategic Policy Objectives outlined in the National Policy Statement for the Bioeconomy?

Research Question 3 (RQ3): Has there been alignment between aspects of the circular economy reported in broadsheet media coverage and the Strategic Policy Objectives outlined in the National Policy Statement for the Bioeconomy?

it was considered appropriate to adopt a directed content analysis with the coding scheme developed prior to commencing the data analysis. In this case, a global thematic framework for analysis of the data was afforded by consideration of the media discourse on each of the SPOs: Sustainable economy and society; Decarbonisation of the economy; Jobs and Competitiveness; Regional Prosperity. To achieve this, each section of the articles was coded by sub-theme based on the framework outlined in .

Table 3. Sub-themes and coding rules (adapted from Devitt et al., Citation2019).

Following a similar procedure to Step 1, each article was read three times in order to avoid any duplication and to ensure compatibility with the thematic framework and coding rules (Devitt et al., Citation2019). Due to the small sample of articles in this study in comparison with other comparable studies (Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017), it was decided that a qualitative approach examining the context and content of language used in each article would enable us to identify multiple themes within each article and thereby optimise insights from the sample. Accordingly, all sections of articles were then coded in relation to their alignment with the respective SPO coding rules. Depending on content, each article could be coded with multiple SPO’s. Although external coder reliability was not undertaken on the data, validation analysis was conducted in line with recommendations from Elo and Kyngas (Citation2008) between the authors on coding issues and any potential overlap/merging of themes.

5. Results (Step 5)

5.1. Broadsheet media coverage of the development of the bioeconomy and circular economy between 2004 and 2019 (RQ1)

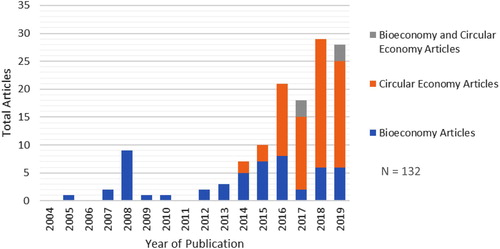

The concept of the bioeconomy in the Irish broadsheet media emerged very slowly in the early years of the time period (See ). As the results demonstrate, coverage increased over the final five years of the period under investigation. There was a total sample of 53 bioeconomy related articles. In terms of the circular economy, 73 relevant articles were identified. These do not begin to appear until 2014 but grow in frequency and at a greater rate than bioeconomy related articles during the 2016–2019 time frame. Only six articles refer to both the circular economy and bioeconomy: such articles do not appear until 2017.

Figure 2. Frequency of bioeconomy and circular economy related articles in the three newspapers (2004–2019).

In terms of total numbers, Informational content (63) provided the majority of articles relating to the bioeconomy/circular economy in the three newspapers in the period 2014–2019. Some of these articles, although implicitly pro-bioeconomy/circular economy in tone, were primarily factual in presentation. Pro-articles (50) were explicitly supportive in their portrayal of the current state of the bioeconomy/circular economy, including unchallenged reporting of government/public body sources. An approach which sought to examine the evidence from a more detached and balanced perspective was discernible in considerably less articles (19). There was no evidence of coverage in the three broadsheet newspapers that adopted a hostile or incisively critical approach in reporting the development of the bioeconomy/circular economy in Ireland. provides an overview of content for the three categories of articles.

Table 4. Overview of article contents.

Table 5. Fifteen most recurrent substantive topics in the Irish broadsheet newspapers 2004–2019.

5.2.1. Informational articles (n = 63)

About 62% of bioeconomy related articles were categorised as informational. The content of the articles from the early years of the study period focused on EU funding for research projects and the Government’s support for such activity, particularly in relation to research into agriculture and food. The overall tone of the media coverage throughout the 15 year period shows scant concern with any anti- bioeconomy aspects of its development in Ireland. There is implicit acceptance of the social, environmental and economic benefits of research by such institutions as Teagasc and BeaconFootnote1: “Agri-food and forestry researchers welcome €23 m grant awards” (IE, Nov 27, 2012). Excerpts from speeches by Government ministers or research facility directors, invariably positive in tone, are reported without editorial comment by the newspapers.

More than one-third of articles related to the circular economy were categorised as informational. Although not overtly pro-circular economy, such articles were expressed, similarly to those relating to the bioeconomy, without any critical comments, particularly when focused on issues of sustainable practices: “Kingspan to recycle 1bn bottles a year” (IND, March 22, 2019); “Goodman’s ABP beefs up green investment” (IND October 13, 2017). Any qualification included in the coverage was focused, not on the aspect of the circular economy reported, but on perceived shortcomings of actors involved in expediting its development: “Meeting new EU recycling targets by 2030 ‘difficult'” (IT, 6 March 2018); “Plastic packaging recycling must rise by 80% to hit target” (IT, 20 September 2018). The small number of articles which referred to both the bioeconomy and the circular economy shared a common focus on research issues: “Three Irish projects are researching how to turn excess CO2 into new products” (IT, 18 July, 2019); “Taoiseach hails new research centre” (IE, 9 September 2017).

5.2.2. Pro-bioeconomy/circular economy articles (n = 50)

One quarter of bioeconomy related articles were categorised as overtly positive in their coverage of developments in relation to the bioeconomy emphasising its importance, particularly in terms of technological advancement, across a range of sectors within the national economy, especially in farming and food: “Ground-breaking dairy project gets EUR 22 m. in EU funding” (IT, 27 April 2018). There was growing evidence of an awareness of the significance of eco-friendly techniques and the importance of the bioeconomy as an opportunity for Ireland across the 15 year period. The concept was seen in terms of economic growth, new jobs and the development of a sustainable society: “Smart use of renewable resources ‘can revitalise' deprived rural areas” (IT, 15 Feb 2013). Quotes from Government sources or others with a vested interest in the advancement of the bioeconomy were unchallenged by editorial opinion.

At 47%, articles which related to the circular economy and were framed in overtly favourable terms, constituted almost twice those of a similar perspective which focused on the bioeconomy. However, the scope of these articles was perceptibly reduced, with a preponderance of coverage devoted to issues of sustainability and also decarbonisation of the environment: “Start saving the planet at home with this A-Z guide … ” (IT, 17 Feb 2018); “Budget 2020 must be basis for low-carbon living” (IT, 13 June 2019). The articles which referred to both the bioeconomy and the circular economy focus on their significant role in achieving climate targets: “Budget 2020 must be basis for low-carbon living” (IT, 13 June 2019).

5.2.3. Balanced articles (n = 19)

More than one in 10 bioeconomy related articles were found to be balanced in their coverage. “Ireland can be a leader in the new bio economy … Can we position ourselves to take advantage?” (IT, 25 February 2016). The reporting rarely included comment from vested interests but provided an objective and not unquestioning review of the facts: “From boat building to farming, all together in the bioeconomy” (IE, 17 September 2015).

A similar approach informed 16% of circular economy related articles which were categorised as balanced: “Is Galway worthy of its green leaf award?” (IT, 4 March 2017); “Becoming an island full of plastic paddies is now a burning issue” (IE, 22 June 2017)

5.2.4. Anti-bioeconomy/circular economy articles (n = 0)

Articles expressing an overtly antagonistic or even merely negative attitude to the bioeconomy were not in evidence, suggesting either a limited critical awareness of the current development of the bioeconomy, for example in relation to lack of engagement with interests at a local level and concerns relating to a just transition,or perhaps a post- recessionary eagerness to extol its advantages.

5.2.5. Sectors/topics which have received most prominence in broadsheet media coverage

The initial word frequency count generated a very diverse data set of the fifty most frequent words for both bioeconomy and circular economy articles. These were then grouped into fifteen discrete substantive topics (see ).

reflects the prominence in media discourse of “Research” associated with the bioeconomy in Ireland. Aspects within this domain – “Innovation”, “Development” and “Production” – are also highlighted. “Teagasc” the State agency which provides research, advice and education in agriculture, horticulture, food and rural development in Ireland is also frequently mentioned. “Food” and “Agri-food” are frequent topics of media focus. The importance given to “Rural” affairs and the significance of development in this dimension on the population is also noted. Other key sectors generally related to the bioeconomy such as Forestry, Waste and Marine do not occur among the fifteen most substantive topics.

In contrast, the most frequently appearing topics in the circular economy articles relate to issues of “Waste”, “Plastic” and “Recycling”. “People” and “Clothing” are other topics which do not appear in the Bioeconomy related media coverage but appear in circular economy-related articles. However, there is alignment between the articles particularly in terms of the amount of coverage of issues related to “Production”, “Energy”, “Sustainability” and “Food” and to a lesser extent “Industry” and “Development”.

5.2. Alignment between aspects of the bioeconomy reported in the broadsheet media and the Strategic Policy Objectives outlined in the National Policy Statement for the bioeconomy (RQ2)

No knowledge existed of how early or late in the decade any emerging press coverage of each SPO would appear. The chronological emergence and reporting of key issues relating to each of the SPOs over the time period is therefore presented below. Of the four SPOs, Sustainable Economy and Society dominates coverage with 83% of all bioeconomy related articles referring to it (see ). Regional Prosperity occurred in 40% of these articles. The amount of coverage on issues relating to the remaining two Strategic Objectives of Government was very similar (26% and 28%).

Table 6. Percentage of total articles referring to National Statements Strategic Policy Objectives.

5.2.1.Sustainable economy and society

Early media attention, during the study period, on the concept of the bioeconomy and the principle of sustainable development and its benefits for society began with reports which referenced the role of Teagasc and the agri-food sector. (“The focus in future will be on agri-food and the wider bio-economy.” IE, 9 October 2009). It was clear that media framing of sustainability was largely, at this juncture, in terms of agriculture and food production. (Teagasc Director: “Our aim is to support science-based innovation in the agri-food sector and the broader bioeconomy. These goals serve to underpin profitability, competitiveness and sustainability within the sector.” IE, 2 February 2013). The importance of the EU in the promotion of a sustainable economy became more evident by 2014 in the reporting of EU Horizon 2020 funding and the challenge by Research Commissioner Maire Geoghegan- Quinn “to deliver good jobs and major benefits to society” (IE, 10 July 2014) through public/private collaboration. Further framing of the development of sustainability in the economy in terms of EU involvement occurred in reports of how EU agriculture co-ops invest in the integration of “renewable energy in the agri-food production process, and extensive bioeconomy applications through the use of by-products and recycling.” (IE, 14 July 2014).

While the role of state agency Teagasc in the promotion of sustainability through the bioeconomy has been reported since the beginning of the coverage, any evidence of alignment with the attitudes of Irish politicians did not appear in the media until much later with Taoiseach Leo Varadkar’s 2017 announcement of four new research centres (IE, 8 September 2017). He went on stress the benefit to the economy and to society in terms of quality of life. The responsibilities of business in facing up to the challenges of environmental sustainability are made clear in the content and tone of an Irish Times article in early 2018. It re-iterated “the bottom line of people, planet and profit … Businesses will need to change their own models … we require governments and policy makers to provide regulations, supporting infrastructure, resources and incentives” (IT, 9 March 2018). The unusually trenchant tone of the piece criticises government policy in a much more direct style than evidenced hitherto: “ … while the government is doing some things, environmental campaigners say this is not enough, and we would argue a more sustained and integrated effort is required” (IT, 9 March 2018).

5.2.2. Decarbonisation of the economy

Although there was some limited media coverage in the early years of the study period, an informed focus on the scope and significance of research projects funded by the EU was evident by 2012. This research aimed at developing practices which would improve efficiency and environmental impact of the food, agri-food and forestry sectors in particular. Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Simon Coveney’s statement was reported, although without any critical appraisal: “Publicly funded research will continue to play a key role in driving innovation within the bioeconomy” (IT, 25 November 2012).

The emerging perception of the value of the bioeconomy in working with nature and actively preventing pollution of the environment was in evidence early in 2013 in a favourable book review (IT, 23 January 2013). The author’s (Tony Juniper) advocacy of building a bioeconomy “one that meets human needs while also protecting the natural systems that provide us with essential services” was reported. Media coverage of SXSWECO, a three-day conference on issues relating to the bioeconomy, reported such innovatory practices as Bio-mimicry “a design approach that copies nature’s patterns and strategies to find sustainable solutions to human challenges” and the progress of the post-animal bioeconomy “advancements in meat and milk produced in cell culture” (IT, 12 October 2015).

Focus on a more enhanced approach to the bioeconomy emerged later in the study period in more prescriptive coverage. “Ireland … needs to address challenges associated with food security, energy security, climate change and reducing our dependence on fossil resources … The bioeconomy has the opportunity to diversify its activities so that it can produce chemicals, materials and fuels needed by society, and add value to existing waste products” (IT, 25 February 2016). Evidence that media coverage of the development of the bioeconomy and its role in decarbonisation of the economy has progressed through the decade was also shown in a growing awareness of the range of sectors within the concept: for example, Forestry “Engineered timber is the material of the twenty-first century” (IT, 12 April 2018) and dairy waste products converted into “high-value bio-based commodities, including biodegradable plastics” (IT, 27 April 2018).

5.2.3. Jobs and competitiveness

The downturn in the economy consequent to the 2008 recession and in particular the decline in jobs in rural areas was highlighted in broadsheet media coverage in the earlier years of the 15-year-period analysed. There was a recognition that construction-related employment had masked the jobs lost in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors prior to 2008. That situation no longer pertained after the recession. Teagasc director Professor Gerry Boyle stated that “Teagasc goals are to improve the competitiveness of agri-food and the wider bio-economy … and encourage diversification of the rural economy” (IE, 9 October 2009). Within a year, media coverage related to tangible developments in that vision with reports of a new rural facility which the European Commissioner was cited as announcing would represent “faith in Ireland’s talents in research and science as springboards to growth and jobs” (IE, 23 November, 2010). Although the prevailing nature of broadsheet reporting was focused on the agri-food sector (“Ireland’s agri-food sector has unique and advantageous characteristics,” IE, 2 February 2013), a wider perspective was being reported by 2012. Coverage of research developments now included the forestry and marine sectors (“Agri-food and forestry researchers welcome €23 m grant awards,” IE, 27 November 2012; “Fresh call for research proposals in agri-food, forestry and fishery areas,” IE, 12 March, 2014; “Forestry key to creating green jobs,” IE, 26 January 2015).

In 2015, the negative media framing deployed earlier in the decade correlating the dairy sector jobs and construction changed with broadsheet coverage of the conclusions arising from a new report on the economic impact of the Irish Bioeconomy (“The building industry would be the main jobs beneficiary, because of the requirements to increase capacity in sheds and in milking parlours,” IE, 17 September 2015). In 2017, an article entitled “From boat building to farming, all together in the bio-economy” reported a new bio-economic model of the economy “which seeks to quantify the scale and interactions between the green economy (agriculture and forestry) and the blue economy (everything associated with the sea).” This coverage was reinforced by the media’s consistently positive framing of a vision for the bioeconomy (“Building a new bio-economy for Ireland presents an opportunity for new green jobs,” IT, 25 February 2016; “Bringing migrants home ‘central' to Governments Action Plan for Jobs 2016 … focus on new sectors including the bio-economy”, IE, 19 January 2016). In late 2017, reporting of the statement by the Taoiseach that collaborative efforts between researchers and private companies would help to create high-value jobs and drive economic growth was reinforced by coverage of BEACON’s intention to stimulate “developments of new technologies and products that will create new jobs, secure existing jobs … ” (IT, 8 September 2017).

5.2.4. Regional prosperity

As with the discourse relating to “Jobs and Competitiveness,” the post 2008 recession coverage of the theme of Regional Prosperity focused on the problems associated with rural decline. Speakers representing the Rural Economic Research Centre (Teagasc) are cited as stating unequivocally “that what was being witnessed now was the beginning of long-term changes in the structure of the rural economy … farmers and rural dwellers need to change the way they think … a mind-set change is needed to identify the opportunities for development” (IE, 9 October 2009).

Evidence of a framing of the issue of regional prosperity in a more aspirational tone did not appear until the middle of the study period: “Smart use of renewable resources “can revitalise” deprived rural areas” (IT, 15 February 2013) and “EU agri co-ops leading the way with eco-friendly techniques … sustainable development of communities through policies approved by their members” (IE, 14 July 2014). Further evidence of a discourse underpinned by positivity was found in articles citing conclusions of a new report on the economic impact of the Irish bioeconomy: “farmers increasing their cow numbers from 2013 to 2025 would support an extra 3400 jobs, primarily in construction but 1500 jobs in the wider economy are expected due to dairy expansion … Farmers in Ireland are relatively well placed to make these investments, because their debt levels are low compared to dairy farmers in Europe” (IT, 17 September 2015). In an article outlining the range of sectors within the bioeconomy model, the importance of Government targets for the agri-food and marine sectors was emphasised although without any critical appraisal. Continuing the generally optimistic framing of information relating to regional prosperity, it was noted that although “there is a relatively low increase in direct labour associated with an increase in agriculture or food output … because of the links with other businesses in rural areas, the increase in indirect labour associated with an increase in agricultural output is much higher than for many other enterprises” (IE, 17 September 2015).

By 2016, the role of future technologies and the importance of adoption rates of digital communication and agri-eco practices in terms of innovation in the regional economy was highlighted in broadsheet media coverage of the Teagasc Technology Foresight 2035 conference: “Farmer buy-in vital for future technologies” (IE, 9 March 2016); “Conference outlined the breakthrough technologies that will transform the Irish agri-food and bio-economy sector over the next 20 years” (IND, 15 March 2016). The continuing emphasis in the media of the importance of assisting in halting rural decline and the significance of the bioeconomy in that process was present in the broadsheet media reporting of a declaration on European Rural Development for the twenty-first Century emanating from a conference in County Cork in 2016: “ extending the bioeconomy beyond agriculture and food has … opened new doors … digitisation of the rural economy and rural business, with fibre broadband, can bring an army of knowledge workers to the countryside … That alone would go a long way towards making rural areas and communities attractive places to live … ” (IE, 15 September 2016).

5.3. Alignment of broadsheet media coverage of the circular economy with the national statement’s strategic policy objectives (RQ3)

The closest alignment of circular economy-related articles was with the SPOs of Sustainable economy and society and Decarbonisation of the economy (see ). The framing of issues of sustainability in terms of a “circular” economy first emerged explicitly in late 2017 with media coverage of a report from the National Economic and Social Council. The article reported the Council’s conclusion that the full potential of the circular economy was not fully known. “Many governments now see that the circular economy and the bio-economy are part of the transition to a low carbon economy and society” (IE, 25 October 2017).

Indeed, all but one of the circular economy-related articles over the period of study focused on issues of sustainability and its seminal importance for Irish economy and society. These issues were wide-ranging in scope, including waste and recycling in clothing: “ … less than 1% of clothing is recycled into new clothes” (IT, July 2019); “Circular fashion was the buzzword in Grafton Street yesterday as a new pop-up store opened, attracting forms of sustainability and consumers conscious about consumption” (IND, 18 May 2019). Another recurring issue was waste in food production and the benefits of the recycling process: “ ultimate aim is to create a circular economy by transforming all of the community’s organic and biological waste … into compost, capable of producing an abundance of nutritious, organic food”; (IT, 5 January 2019).

Almost half of the circular economy-related articles also referred directly to its significance in the process of Decarbonisation of the economy. In particular, this coverage highlighted problems associated with energy production and environmental concerns: “In 2005, the EU established the first emission trading scheme, which remains the world’s largest carbon market” (IE, 19 April 2019); Moreover, the current situation in terms of Ireland’s performance towards attaining decarbonisation of the economy was conveyed in stark terms: “The EU Climate Change Performance Index recently ranked Ireland as the worst performing EU country. We need to make sure that climate change is at the centre of policy objectives in Ireland … ” (IND, 26 March 2019). This critical but aspirational attitude was reinforced by headlines such as “Budget 2020 must be basis for low carbon living … ” (IT, 13 June 2019) and continuing on to criticise Ireland’s poor record in implementing climate change policies means that “there is a vast suite of policies the Government can implement in budget 2020 to lay the foundation of a transition to a low-carbon, sustainable future.”

There was very little coverage of the other two SPOs with only four articles referring at all to Jobs and Competitiveness: “A supportive approach to the circular economy in Ireland would help to gain Irish enterprises competitive advantage” (IE, 25 October, 2019). Even fewer articles (3) contained any reference to the relationship of the circular economy with Regional Prosperity: “consumers wishes are transferring back down the production line to farmers, and impacting how they raise animals and grow crops” (IE, 14 March 2016).

6. Discussion

Using three research questions this paper set out to present evidence of the Irish broadsheet media’s framing of the circular bioeconomy in Ireland. The results indicate that Irish broadsheet media coverage has been marked by its paucity although it did become more substantial in the years 2015–2018. It is evident from the critical evaluation of the 15-year media coverage that the development of the bioeconomy in Ireland has been framed in largely informational terms in which the views of the Government and other significant actors are presented in articles which are devoid of criticism in either content or tone. In agenda setting and in framing news, at least implicitly, they frame an acceptance of the benefits of the bioeconomy, particularly in relation to research and innovation.

Here, the role of press releases from Government/scientific/research sources in framing news influencing public perception of the concept of the bioeconomy is significant. Not only do they provide news media with information but they also help to create acceptance of their organisations’ perspectives and goals (Park & Reber, Citation2010; Zoch & Molleda, Citation2006). It seems to reflect more recent findings that framing is essentially a strategic exercise carried out by both political actors and mass media in pursuance of their own goals and interests (Sadath et al., Citation2013) and underlines the fact that knowledge is political (Pestre, Citation2003). In an area that is “marred by competing interests” and “requiring input, compromise and consensus from a diverse range of public, private and civil society actors” (Devaney & Henchion, Citation2018) concerns that bioeconomy development is balanced, inclusive and just arise. Moreover, the importance of the power of un-mediated press releases to form the framing of the bioeconomy is heightened by the lack of awareness of the concept particularly in the early and middle stages of media coverage during the 2004–2019 period. An explicitly pro-bioeconomy stance is found in fewer articles in this period but these outnumber those which can be categorised as “balanced”. Pro-bioeconomy framing tends to rely on unchallenged reporting from Government sources, especially the pronouncements of Ministers.

As Peltomaa (Citation2018) observes, such reporting leads to power-related questions about how and by whom the bioeconomy is framed, and which societal actors are included/excluded in its transition. The framing does suggest, intentionally or unintentionally, a lack of consideration for the role of citizens, and other key actors, such as primary producers and industry, and the alternatives values they might hold, which could potentially challenge the legitimacy of the bioeconomy. While it could be argued that the low level of awareness of the bioeconomy amongst most lay people precludes them from engaging in the bioeconomy and thus being reported on and represented in the media, a critical analysis of the bioeconomy by the media could highlight their absence and in fact call for their inclusion. Whether this is likely in an environment where the media is dependent on mainstream institutions for their stories, and thus may “share the values and interests of political and economic elites” (Mercille, Citation2017) is however questionable.

Media coverage which could be considered as balanced in terms of conveying a critical awareness of the relevant issues for both concepts (bio and circular economy) were difficult to find, as the results suggest. Such articles were usually framed, not by considering the benefits or otherwise of the bioeconomy or circular economy, but by questioning the state of readiness of the country to take advantage of such provision, or by criticising the rate of progress so far. Furthermore, no articles related to either concept could be deemed as being framed in a negative manner or in an explicitly critical tone.

Ireland’s National Policy Statement on the Bioeconomy identifies a range of core sectors including agriculture, forestry, marine, energy, municipal waste, nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals. It is evident from the results that the media portrayal of the key sectors within the bioeconomy to date is not as wide ranging. Indeed, there has been a clear focus so far on agriculture and food. This is not surprising as these sectors are of such significance in Ireland. A similar content analysis of media articles undertaken in Finland identified a preponderance of Forestry related articles (Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017). However, the omission of the marine sector is notable as Ireland has an important ocean economy based upon having one of the largest seabed territories in Europe. Indeed, the direct economic value of this sector was €1.8 billion or approximately 0.9% of GDP in 2016.

For the most part, the circular economy-related articles appear to focus on more consumer/citizen related issues such as the effects of plastic waste, recycling and public involvement. However, the central tenet of the bioeconomy, sustainability, as noted amongst others by Woźniak and Twardowski (Citation2018) and Devaney and Henchion (Citation2017), features in much of the media discourse focused on both concepts. The Irish policy statement on the bioeconomy, states that growing the bioeconomy can put Ireland’s economy on a more sustainable footing by encouraging the efficient use and re-use of resources and materials to a much greater extent than hitherto. Indeed, many governments’ bioeconomy strategies issued since 2015 refer to a “sustainable bioeconomy” and seek to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, with green growth as a key goal (German Bioeconomy Council, Citation2018).

At this point, it is incumbent to acknowledge recent research which has questioned the adequacy in terms of sustainability issues of the European Commission’s Strategy for the Bioeconomy and by association national strategies such as Ireland’s National Policy Statement on the Bioeconomy. Critical comment has focused on the need for a valid perception of the concept of sustainability. It is argued that a broader definition involving a more holistic approach to development is required in which a balance is achieved between the environmental, social and economic dimensions of policy (Kleinschmit et al., Citation2017; Ramcilovic-Suominen & Pülzl, Citation2018). From this perspective, a sustainable bioeconomy requires not only competitiveness and efficiency but also appropriate consideration of a range of crucial issues from biodiversity and soil quality to social justice and equity.

While the central issue of securing a sustainable future is noted in the coverage of the bioeconomy-related articles, unlike the circular economy coverage there is little evidence of providing the public with a holistic vision of the concept. A consistent feature of the articles related to the bioeconomy in Ireland has focused on the role of government agencies such as Teagasc and the funding and development of research facilities. Reporting of statements by Irish government ministers became more frequent by the mid-decade period. These announcements tended to emphasise the importance of innovative development and in terms of the three visions of the bioeconomy delineated by Bugge et al. (Citation2016), demonstrated particular concern with the biotechnology domain. This reflects the assertion of Sadath et al. (Citation2013) that the media discussion and framing are influenced by specific speaker groups, who are often “elites.” Furthermore, it reflects the concerns of Kitchen and Marsden (Citation2011) in relation to the role of the bioeconomy in the creation of sustainable rural communities; a more holistic vision would include not only the reported technological changes but also a wider dimension relating to a better quality of life in a more environmentally sound and socially just bioeconomy. The neglect of issues such as equality and inclusiveness might hamper, in particular, public acceptance of the benefits of the bioeconomy concept (Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017).

Mccormick and Kautto (Citation2013) draw attention to participatory governance and engaging the general public and key stakeholders in dialogue as a requirement for a competitive and sustainable bioeconomy. Our results indicate that visions of a wide range of societal groups (other than government actors, public bodies and, to a lesser extent, business interests) are not being given expression in the broadsheet media. Consequently, the potential for citizens’ and other groups’ participation in policy development receives scant media recognition. Indeed, independent broadsheet media commentary on the progress of the development of the bioeconomy in Ireland is notably absent until very late in the study period when some, albeit limited, evidence of a more critical tone emerges. However, the focus of such adverse comment is not on the absence of any sense of societal equality and inclusiveness in the prevailing narrative but on the requirement for greater urgency on the part of government and business actors.

The articles in this Irish media analysis have largely been supportive of the role of government in the promotion and development of the bioeconomy to date. However, while the Government's Strategic Policy Objectives for the expansion of the Irish bioeconomy have been presented without any indication of priorities, the scope and content of media articles suggest a perceptible differentiation in terms of emphasis (Scheufele & Iyengar, Citation2012). As mentioned previously, due to the relatively small sample and multi-thematic nature of many of the articles a qualitative assessment of the sub-theme coding undertaken on each of the articles indicates that most significance in relation to the bioeconomy was given to “Sustainable Economy and Society” followed by “Decarbonisation of the economy”, “Jobs and Competitiveness”, and finally “Regional Prosperity”. The nature of this coverage might reflect the media’s awareness of which of these objectives would most resonate with public interest (Neresini & Lorenzet, Citation2016) in differing aspects of the circular bioeconomy.

The circular economy related articles also show a predominant concern with “Sustainable Economy and Society” in particular, followed by aspects of “Decarbonisation of the economy”. Articles on the former tend towards emphasis on initiatives relating to waste and recycling. Interest in the latter is represented by a focus on energy production and consequences for the environment. An acute awareness of Ireland’s less than impressive performance in reducing carbon emissions is often expressed in the circular economy coverage. Consequently, it is not really surprising that these articles are more likely to adopt a more consistently critical stance than bioeconomy articles on a perceived lack of urgency on the part of the government. There is little evidence in the circular economy coverage of the other two SPOs outlined in the National Policy Statement for the Bioeconomy. This is not surprising but helps to highlight how “many elements of the bioeconomy go beyond objectives of the circular economy” (Carus & Dammer, Citation2018, p. 5).

7. Conclusion

Irish broadsheet media coverage of the circular bioeconomy has been limited in scope, and uncritical acceptance of the top-down discourse in which the bioeconomy has been presented was evident. Regarding its scope, reporting needs to be rebalanced to reflect, and critique, (a) alternative visions of the bioeconomy with greater emphasis put on the bio-resources and bio-ecology domains to balance perspectives relating to the bio-technology vision, (b) to expand the discussion beyond agriculture and food into other sectors and (c) to bring more voices into the discussion. The latter points to a need for further research which focuses upon an evaluation of the “speakers” in the media and the nature of their framing procedures in order to determine the actors who dominate media reporting.

If the policy objectives of the bioeconomy are to be achieved then engagement of as wide an audience as possible is crucial. In other words, all relevant actors and stakeholders have to have a role in shaping the bioeconomy “if they are to see bioeconomy as a possible or desirable future” (Vainio et al., Citation2019, p. 1404). Wider and more incisive reporting on the absence of societal equality and the necessity for citizens' participation, along with other key stakeholders, in bioeconomy policy development is required. Another group requiring particular attention is primary producers. Given the ambition stated in the Biobased Industry Consortium’s Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda to involve primary producers as strategic partners,Footnote2 results of previous research in Europe which revealed that farmers are the most sceptical of the equitable benefits of the bioeconomy (Stern et al., Citation2018) suggests that this ambition may be premature. It also points to a significant role for the media with this group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Beacon is Ireland’s national Bioeconomy Research Centre, funded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) and co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund. The Centre was rebranded as BiOrbic from 31st January 2020. Teagasc is the state agency providing research, advisory and education in agriculture, horticulture, food and rural development in Ireland.

References

- Albrecht, M. (2019). (Re-)producing bioassemblages: Positionalities of regional bioeconomy development in Finland. Local Environment, 24(4), 342–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1567482

- Bayulgen, O., & Arbatli, E. (2013). Cold war redux in US–Russia relations? The effects of US media framing and public opinion of the 2008 Russia–Georgia war. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 46(4), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2013.08.003

- Boykoff, M. T. (2013). Public enemy no. 1: Understanding media representations of outlier views on climate change. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(6), 796–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213476846

- Böcher, M., Giessen, L., & Kleinschmit, D. (2009). Discourse and expertise in forest and environmental governance: Special issue. Forest Policy and Economics, 11(5–6), 309–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2009.08.001

- Bugge, M., Hansen, T., Klitkou, A.; Circle, Institutionen För Kulturgeografi Och Ekonomisk, G., Lund, U., Department of human, G. & Lunds, U. (2016). What Is the bioeconomy? A review of the literature. Sustainability, 8(7), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8070691

- Cannon, T., & Müller-Mahn, D. (2010). Vulnerability, resilience and development discourses in context of climate change. Natural Hazards, 55(3), 621–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-010-9499-4

- Carus, M., & Dammer, L. (2018). The Circular Bioeconomy—Concepts, Opportunities, and Limitations. Industrial Biotechnology, 14. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from http://bio-based.eu/downloads/nova-paper-9-the-circular-bioeconomy-concepts-opportunities-and-limitations/. .

- Carvalho, A., & Burgess, J. (2005). Cultural circuits of climate change in U.K. broadsheet newspapers, 1985–2003. Risk Analysis, 25(6), 1457–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00692.x

- Castrechini, A., Pol, E., & Guàrdia-Olmos, J. (2014). Media representations of environmental issues: From scientific to political discourse. European Review of Applied Psychology, 64(5), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.08.003

- CCAC. (2019). Climate change advisory council – annual review 2018.

- Coenen, L., Hansen, T., Rekers, J. V., Lund, U.; Department Of Human, G., Pufendorf Institute For Advanced, S., Circle, Institutionen För Kulturgeografi Och Ekonomisk, G., Pufendorfinstitutet & Lunds, U. 2015. Innovation policy for grand challenges: an economic geography perspective. Geography Compass, 9(9), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12231

- Cohen, B. C. (1963). The press and foreign policy. Princeton University Press.

- Crow, D. A., & Lawlor, A. (2016). Media in the policy process: Using framing and narratives to understand policy influences: Media in the policy process. Review of Policy Research, 33(5), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12187

- Culley, M., Ogley-Oliver, E., Carton, A., & Street, J. (2010). Media framing of proposed nuclear reactors: An analysis of print media. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 20(6), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1056. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1056

- D'amato, D., Korhonen, J., & Toppinen, A. (2019). Circular, green, and Bio economy: How do companies in land-use intensive sectors align with sustainability concepts? Ecological Economics, 158, 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.026

- Davies S. G. L., Vironen H., Bachtler J., Dozhdeva V., Michie R. (2016). Case studies of national bioeconomy strategies in Finland and Germany. BioSTEP Deliverable 3.1.

- De Besi, M., Mccormick, K., Lund, U.; The International Institute For Industrial Environmental, E., Internationella, M. & Lunds, U. (2015). Towards a bioeconomy in Europe: National, regional and industrial strategies. Sustainability, 7(8), 10461–10478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70810461

- Delvenne, P., & Hendrickx, K. (2013). The multifaceted struggle for power in the bioeconomy: Introduction to the special issue. Technology in Society, 35(2), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2013.01.001

- Devaney, L. A., & Henchion, M. (2017). If opportunity doesn’t knock, build a door: Reflecting on a bioeconomy policy agenda for Ireland. The Economic and Social Review, 48, 207–229.

- Devaney, L., & Henchion, M. (2018). Who is a delphi ‘expert’? Reflections on a bioeconomy expert selection procedure from Ireland. Futures, 99(May), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.03.017

- Devitt, C., Brereton, F., Mooney, S., Conway, D., & O'Neill, E. (2019). Nuclear frames in the Irish media: Implications for conversations on nuclear power generation in the age of climate change. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 110, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2018.09.024

- Devitt, C., & O’Neill, E. (2017). The framing of two major flood episodes in the Irish print news media: Implications for societal adaptation to living with flood risk. Public Understanding of Science, 26(7), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516636041

- EC. (2012). European commission, d.-G.f.R.a.I.E. innovating for sustainable growth: A bioeconomy for Europe. European Commission.

- EC. (2018). European Commission, d.-G.f.R.a.I.E. A sustainable bioeconomy for europestrengthening the connection between economy, society and the environment: Updated bioeconomy strategy. European Commission.

- EEA. (2018). European Environmental Agency: The circular economy and the bioeconomy. Partners in sustainability. EEA Report No 8/2018. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Elo, S., & Kyngas, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Entman, R. M. (1991). Framing U.S. coverage of International news: Contrasts in narratives of the KAL and Iran air incidents. Journal of Communication, 41(4), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1991.tb02328.x

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- EPA. 2019. Environmental Protection Agency. Ireland’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Projections 2018-2040. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/air/airemissions/ghgprojections2018-2040

- Escobar, M. P., & Demeritt, D. (2014). Flooding and the framing of risk in British broadsheets, 1985–2010. Public Understanding of Science, 23(4), 454–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662512457613

- Gamson, W. A & Modigliani, A. 1987. The changing culture of affirmative action. In R. G. Braungart & M. M. Braungart (Eds.), Research in political sociology (Vol. 3, pp. 137–177). Greenwich, CN: JAI Press.

- Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/229213

- German Bioeconomy Council. (2018). Bioeconomy Policy (Part III) Update Report of National Strategies around the World: A report from the German Bioeconomy Council. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/publication/bioeconomy-policy-part-iii-update-report-national-strategies-around-world_en

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. Free Press.

- Goven, J., & Pavone, V. (2015). The bioeconomy as political project: A polanyian analysis. Science. Technology & Human Values, 40(3), 302–337. doi:10.1177/0162243914552133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243914552133

- Graber, D. (2006). Mass media and American politics (7th ed.). CQ Press.

- Hausknost, D., Schriefl, E., Lauk, C., & Kalt, G. (2017). A transition to which bioeconomy? An exploration of diverging techno-political choices. Sustainability, 9(4), 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040669

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Ireland, G. O. (2018). National policy statement on the bioeconomy.

- Iyengar, S. (1990). Framing responsibility for political issues: The case of poverty. Political Behavior, 12(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992330

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames.. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341

- Kelleher, L., Henchion, M., & O’Neill, E. (2019). Policy coherence and the transition to a bioeconomy: The case of Ireland. Sustainability, 11(24), 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247247

- Keller, T., & Hawkins, S. (2009). Television news: A handbook for writing, reporting, shooting, and editing. Holcomb Hathaway.

- Kim, S. H., Besley, J. C., Oh, S. H., & Kim, S. Y. (2014). Talking about bio-fuel in the news: Newspaper framing of ethanol stories in the United States. Journalism Studies, 15(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.809193

- Kitchen, L., & Marsden, T. (2011). Constructing sustainable communities: A theoretical exploration of the bio-economy and eco-economy paradigms. Local Environment, 16(8), 753–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.579090

- Kleinschmit, D., Arts, B. J., Giurca, A., Mustalahti, I., Sergent, A., & Pülzl, H. (2017). Environmental concerns in political bioeconomy discourses. International Forestry Review, 19(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554817822407420

- Kleinschmit, D., Böcher, M., & Giessen, L. (2009). Discourse and expertise in forest and environmental governance — An overview. Forest Policy and Economics, 11(5–6), 309–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2009.08.001

- Macnamara, J. (2005). Media content analysis: Its uses, benefits and best practice methodology. Asia-Pacific Public Relations Journal, 6(1), 1–34.

- Marks, G., Hooghe, L., Steenbergen, M. R., & Bakker, R. (2007). Crossvalidating data on party positioning on European integration. Electoral Studies, 26(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2006.03.007

- Marron, A. (2019). ‘Overpaid’ and ‘inefficient’: Print media framings of the public sector inThe Irish TimesandThe Irish Independentduring the financial crisis. Critical Discourse Studies, 16(3), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2019.1570288

- Mccombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of Mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1086/267990

- Mccormick, K., & Kautto, N. (2013). The bioeconomy in Europe: An overview. Sustainability, 5(6), 2589–2608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5062589

- Mcleod, D. M., Kosicki, G. M., & Mcleod, J. M. (2002). Resurveying the boundaries of political communications effects. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research. (2nd ed.; pp. 215–267). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Mercille, J. (2017). Media coverage of alcohol issues: A critical political economy framework—A case study from Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(6), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060650

- Meyer, R. (2017). Bioeconomy strategies: Contexts, visions. Guiding Implementation Principles and Resulting Debates. Sustainability, 9(6), 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9061031

- Mustalahti, I. (2018). The responsive bioeconomy: The need for inclusion of citizens and environmental capability in the forest based bioeconomy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 3781–3790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.132

- Neresini, F., & Lorenzet, A. (2016). Can media monitoring be a proxy for public opinion about technoscientific controversies? The case of the Italian public debate on nuclear power. Public Understanding of Science, 25(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662514551506

- Newsbrandsireland. (2019). Irish Newspaper Circulation January to June 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://newsbrandsireland.ie/data-centre/circulation/

- OECD. (2009). The bioeconomy to 2030: Designing a policy agenda – OECD (2009). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Publications.

- Park, H., & Reber, B. (2010). Using public relations to promote health: A framing analysis of public relations strategies among health associations. Journal of Health Communication, 15(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730903460534

- Peltomaa, J. (2018). Drumming the barrels of hope? Bioeconomy narratives in the media. Sustainability, 10(11), 4278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114278

- Peltomaa, J., & Kolehmainen, J. (2017). Ten years of bioeconomy in the Finnish media. Alue ja Ympäristö, 46, 57–63.

- Pestre, D. (2003). Regimes of knowledge production in society: Towards a more political and social reading. Minerva, 41(3), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025553311412

- Piggot, G., Boyland, M., Down, A., & Torre, A. R. (2019). Realizing a just and equitable transition away from fossil fuels. Discussion brief. Stockholm Environment Institute.

- Ramcilovic-Suominen, S., & Pülzl, H. (2018). Sustainable development – A ‘selling point’ of the emerging EU bioeconomy policy framework? Journal of Cleaner Production, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.157

- Regan, A., & Henchion, M. (2020). Social media and academic identity in food research. British Food Journal, 122(3), 944–956. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2019-0156

- Sadath, N., Kleinschmit, D., & Giessen, L. (2013). Framing the tiger — A biodiversity concern in national and international media reporting. Forest Policy and Economics, 36, 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2013.03.001