ABSTRACT

Advertising frequently promotes environmentally detrimental consumption choices such as air travel. To date, the effects of these ads on individuals’ moral evaluation of unsustainable behaviors are still little understood. This study with a quota-based sample in Germany (N = 199) explored whether individuals morally disengage from the harmfulness of flying due to ad exposure. Based on the theory of moral disengagement (Bandura, 2016, Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth Publishers), we investigated whether individuals neglect negative consequences, seek moral justification or displace responsibility for flying behaviors after seeing flight advertising. The results suggested that individuals low in climate change concern become more neglectful of the consequences of flying, while climate change concerned individuals exhibited the opposite reaction. Irrespective of individuals’ level of climate change concern, ad exposure increased recipients’ displacement of responsibility to other actors. Moreover, we found a correlation between mechanisms of moral disengagement and flying intentions as well as support for aviation policies.

While only a small fraction of the world’s population travel by plane regularly, environmentally conscious individuals account for a disproportionally high number of air travelers (Randles & Mander, Citation2009). Although air travel is recognized as one of the biggest contributors to individuals’ carbon footprint, citizens find it especially difficult to give up on air travel as compared to other greenhouse gas-intensive behaviors (Davison et al., Citation2014). This so-called “flyers’ dilemma” exemplifies the tension between moral principles and behavior: While people may cherish environmental values and accept the moral significance of sustainability, buying flight tickets is still highly desirable (Hibbert et al., Citation2013; Hope et al., Citation2018).

This study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the flyers’ dilemma by investigating the role of advertising in carbon-intensive behaviors. While news reports increasingly highlight the negative impact of climate change (Brüggemann & Engesser, Citation2017), individuals are simultaneously exposed to advertising for environmentally damaging consumer goods in their day-to-day media consumption. However, the role of advertising in triggering desires for unsustainable ways of life is still underexplored.

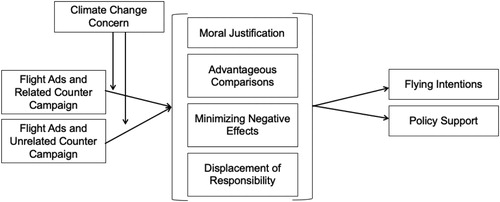

In the current study, we address this research gap by examining the friction between environmental principles and the wish for air travel elicited by flight advertising in the national context of Germany, a country in which 75 percent of individuals describe climate change as a very serious problem (European Comission, Citation2017). Specifically, we investigate how flight advertising and counter-campaigns affect individuals’ mechanisms of moral disengagement (Bandura, Citation1999, Citation2016). These strategies allow individuals to distance themselves from the moral significance of their behavior. The effects of advertising on four distinct strategies are in the spotlight: 1) the moral justification of flying by assigning a positive value to air travel; 2) the advantageous comparison of flight behavior to more environmentally detrimental behaviors; 3) the minimizing of the negative effects of flying as an individual, and 4) the displacement of responsibility. Subsequently, we test how these strategies affect individuals’ behavioral intentions as well as their support for regulating aviation through higher pricing schemes. However, not all individuals might be affected by advertising to the same extent. Therefore, we test if high levels of climate change concern – a central concept in the study of climate change related behaviors and attitudes – might act as a potential boundary condition to the effects of advertising on moral disengagement.

The flyer’s dilemma

In recent decades, the cultural significance of air travel underwent a change of meaning. Following a drastic reduction in ticket prices that made flying accessible to middle class consumers (Young et al., Citation2014), flying turned into a “normal” social behavior, which contributes to the maintenance of social capital, cultural capital, and well-being (Randles & Mander, Citation2009). However, the view of flying has changed in recent years from a taken-for-granted activity to an act which is widely recognized as environmentally harmful (Cohen et al., Citation2011; Hibbert et al., Citation2013). However, increasing awareness does not lead to behavioral change in this sector: While 58 percent of German citizens indicate that they have made lifestyle changes in order to protect the environment (Koos & Naumann, Citation2019), these new norms have not yet led to a reduction in the number of air passengers (Gössling et al., Citation2020).

Cohen et al. (Citation2011) describe “patterns of suppression and denial” in individuals that frequently fly as well as feelings of guilt and shame which typically occur in addicts. While some evidence speaks in favor of seeing flying as an addiction, there are also critics to this view. Young et al. (Citation2014) highlight the economic, technological, and societal influences that contribute to the flyers’ dilemma. In their view, the desire of flying is manufactured by the tourism industry and linked to capital. Therefore, blame cannot solely be attributed to a flawed consumer.

Taking this controversy around the “flyers’ dilemma” as a point of departure, this study investigates the role of advertising in the moral evaluation of flying. Advertising might counteract existing efforts to strengthen environmental knowledge and sustainable consumption choices by promoting carbon-intensive behaviors as a desired way of life (Young et al., Citation2014). Therefore, we propose that advertising triggers the already existing friction between environmental values and the wish to travel by plane. In order to investigate how individuals resolve this friction, we draw on the theory of moral disengagement.

The theory of moral disengagement

The theory of moral disengagement as laid out by Bandura (Citation1999) seeks to explain how individuals manage to depart from their moral principles without feelings of guilt. According to this socio-cognitive approach, moral behavior is governed by people’s anticipation of how they are going to feel about their actions. Acting in line with moral standards increases positive emotions and a benevolent view of the self, while acting against one’s standards is met with self-condemnation and shame.

However, just as individuals learn principles of right and wrong in childhood, they also develop mechanisms to let the ethical component of their actions fade into the background (Tenbrunsel & Messick, Citation2004). So-called strategies of moral disengagement allow them to engage in bullying peers at school (Obermann, Citation2011), corrupt acts in businesses (Moore et al., Citation2012) or justify war atrocities (Aquino et al., Citation2007). Bandura (Citation1999) identifies four focal points at which individuals can morally disengage from the harmfulness of their actions: Firstly, people may invest their action with a different but equally important purpose at the justification locus. That is, the harmful behavior is rendered neutral or even positive by finding a moral justification, comparing it to worse practices or using euphemistic language to obscure its severity. A prominent example of this form of moral disengagement is found in the context of the U.S. American invasion of Iraq, where the war was justified as a “fight of all who believe in progress and pluralism, tolerance and freedom” (Cartledge et al., Citation2015). Second, people can morally disengage at the agency locus. While they might accept the harmfulness of an action, they deny their efficacy and displace responsibility to other actors. Third, at the outcome locus individuals can distort and minimize the consequences of their behavior. If the consequences of an action seem marginal or even positive, there is no need for guilt or shame. Lastly, at the victim locus victims are dehumanized and blame can be shifted to the victim (Obermann, Citation2011). Thus, by shifting responsibility, minimizing the consequences, finding moral justifications or blaming the victim, people resolve the friction between their detrimental conduct and their need to see themselves as good people (Moore et al., Citation2012).

Moral disengagement from the harm of flying

Its grave consequences on vulnerable populations and future generations has rendered climate change a topic of moral importance in recent years (Bandura, Citation2016; Hope et al., Citation2018). This means that formerly socially accepted behaviors are now judged as morally wrong. In this context, moral disengagement might be a fruitful approach to understand why people can continue with carbon-intensive lifestyles while at the same time being environmentally conscious (Bandura, Citation2016; Heald, Citation2017).

While moral disengagement has mostly been researched under the lens of individual traits, the theory also discusses situational influences such as media messages (Bandura, Citation2016). In this light, investigating advertising might be especially insightful as ads could activate desires which stand in contrast to individuals’ environmental values. For instance, advertising heavily propagates carbon intensive lifestyles such as air travel (Young et al., Citation2014). In the current study, we investigate four key mechanisms of moral disengagement (Bandura, Citation1999) which might help individuals to justify their flying behavior as a response to desirable flight advertising.

The first mechanism is the strategy of moral justification. When using this strategy, individuals find ways to “sanctify” their flying-behavior (Bandura, Citation2016). First, frequent flying serves as a mean to live as a citizen of the world. Studies have shown that mobility is an enabling factor for cosmopolitan identities, which are especially prevalent amongst the Western youth and elites (Calhoun, Citation2002; Skrbis et al., Citation2014). Advertising plays on the idea of cosmopolitanism, telling potential customers to “Widen your World” or to “Say yes to the world” (Lufthansa, Citation2018; Turkish Airlines, Citation2018). Second, frequent flying is a way to build and maintain social capital by enabling close relationships with people in other parts of the world (Randles & Mander, Citation2009).

When confronted with favorable images of flying through flight ads, people might highlight positive aspects of flying to morally justify their desire to fly:

H1) Being exposed to flight advertising will lead to higher moral justification as compared to the control group.

As a second strategy, individuals might compare their actions against those of others to render their behavior less harmful. This strategy of advantageous comparison has already been shown to be a decisive factor at the state level. For instance, the Kyoto protocol negotiations were shaped by attributions of blame, in which states highlighted the carbon intensive actions of other actors in order to achieve a better outcome for their nation (Bandura, Citation2016; Heald, Citation2017). In the case of flying, people may compare their actions against other behaviors and thus conclude that there are more problematic ways of life in regard to the climate. Focusing on the environmentally detrimental actions of others might help individuals to minimize negative feelings (Hope et al., Citation2018):

H2) Being exposed to flight advertising will lead to more advantageous comparisons of flying to other environmentally harmful actions, as compared to the control group.

Minimizing the consequences of an action is an especially consequential strategy in regard to climate science. Individuals might minimize their role as contributors to climate change and therefore obscure the harm of their behavior. Neglecting efficacy absolves individuals from making changes to their carbon-intensive lifestyles (Heald, Citation2017). Some people may even argue from a standpoint of fatalism, in which both the negative and positive contributions they make are seen as insignificant (Hope et al., Citation2018). Therefore, when advertising activates their desire to fly, individuals might engage in the mechanism of minimizing consequences by denying the consequences of their own actions.

H3) Being exposed to flight advertising will lead to more minimizing of negative consequences of flying as an individual as compared to the control group.

Anthropology highlights the importance of blame and accusations for the issue of climate change (Hughes, Citation2013). The attribution of blame allows individuals to accept the severity of the climate crisis while neglecting their agentic role (Bandura, Citation2016). Considering that climate change is a complex phenomenon with various actors involved, it is likely that individuals find ways to disengage from the severity of flying by attributing blame to state actors or the industry.

H4) Being exposed to flight advertising will lead to higher displacement of responsibility as compared to the control group.

These four mechanisms of moral disengagement are proposed to act as mediators between ads and people’s flying intentions, and political stance on flying:

H5) The effects of flight advertising on a) individuals’ intentions to fly and b) policy support are mediated by the moral disengagement mechanisms of moral justification, advantageous comparison, minimizing negative consequences, and displacement of responsibility.

The limits of moral disengagement

However, individuals might not morally disengage by default. When certain moral principles or attitudes are central to individuals’ self-concept, they are likely to persevere even in difficult situations and limit moral disengagement (Bandura, Citation2016).

Concerns to cause environmental damage such as climate change concern are rooted in a number of core values that guide climate change behaviors (Fransson & Gärling, Citation1999). Studies consistently find that concern emerges as one of the key predictors to explain a wide range of climate change related attitudes and behaviors (Chryst et al., Citation2018; Swim & Geiger, Citation2017). Thus, individuals high in climate change concern are often more inclined to act in environmentally beneficial ways. Therefore, high climate change concern likely constitutes a boundary condition to moral disengagement. In return, low concern might make moral disengagement more likely: In early studies on the value-action gap in environmental behavior, Blake (Citation1999) theorized that individuals whose “environmental attitudes are peripheral within their wider attitudinal structure” (p. 266), can more easily be swayed by conflicting values and interests. Consequently, people that regard climate change as a severe threat might be less likely to morally disengage:

H6) Individuals high in climate change concern are less likely to use moral disengagement mechanisms of a) moral justification, b) advantageous comparison, c) minimizing negative consequences, and d) displacement of responsibility.

Potential mitigation through counter campaigns

Furthermore, citizens are not solely exposed to desirable messages, but also receive negative information about flying during their media consumption. There are a number of governmental and non-governmental actors which critically discuss this issue (see e.g. European Comission, Citation2019; “Flugverkehr und Citation3. Piste [Flight traffic and 3rd runway]”, Citation2019). However, it is still unclear whether such messages can prevent individuals from moral disengagement.

On the one hand, receiving moralizing messages can sometimes backfire in environmental contexts (Schneider et al., Citation2017). From the perspective of moral disengagement, presenting conflicting messages in advertising and counter-campaigns could exacerbate the tension between desires and moral principles. As a result, mixed messages could lead to a higher need to morally disengage to sustain both environmental values and the wish to fly. On the other hand, it is possible that counter-campaign messages against flying avert certain avenues to morally disengage. For the case of video games, designing the narrative in certain ways can help or hinder the use of moral disengagement strategies (Hartmann & Vorderer, Citation2010). Accordingly, a message which strongly shows the negative consequences of a single flight makes it more difficult to successfully employ the strategy of minimizing consequences or advantageous comparison. Moreover, media messages can help to activate environmental norms and make them more salient in subsequent decision-making (Defever et al., Citation2011).

Since the direction of effects that counter-campaigns have on people’s moral disengagement is unclear, we pose a research question:

RQ1: How does seeing flight advertising followed by counter-campaigns affect moral disengagement mechanisms of a) moral justification, b) advantageous comparison, c) minimizing negative consequences, and d) displacement of responsibility in comparison to the control group?

For the theoretical model, see .

Method

Sample

For this study, N = 217 German participants were recruited by the survey company Dynata between July 24th and August 2nd, 2019. Participants completed this experiment and a second unrelated experiment in counterbalanced order. Five respondents with a completion time of less than ten minutes and 13 respondents with a completion time of more than 75 min for both experiments were excluded from the data analyses, resulting in a final sample of N = 199 participants. The sample parallels the demographical distribution of the German population in terms of age groups (range 18–77; M = 46.45, SD = 15.34) and gender (53.8% female). In addition, respondents came from a variety of educational backgrounds (0.5% without education, 5.5% compulsory school education, 26.1% vocational training, 11.1% secondary school, 29.2% high school degree or equivalent, 27.6% academic degree).

Procedure

The experimental study uses an in-between group design. Participants were randomly assigned to one out of three groups: In the first group, individuals were exposed to flight advertising and a counter-campaign which highlights the harmfulness of flying; in the second group participants saw flight advertising and an unrelated counter-campaign about the harmfulness of sitting as a filler task; in the control group, participants were presented with unrelated advertising about mobile phones as a filler task and a counter-campaign about the harmful effects of sitting as a filler task.

After answering questions about their demography, participants were asked to indicate their travel and flight behavior. Next, participants were exposed to either three flight ads (ad group and counter-campaign group) or three filler ads (control group). As a next step, they were shown either a counter-campaign about the harmful effects of the aviation sector (counter-campaign group) or the filler campaign (ad group and control group). Then, participants answered questions which tapped their moral disengagement strategies. Lastly, they indicated their flying intentions and policy support for regulating the aviation sector. Pre-existing attitudes on climate change concern were included in the beginning of a second, unrelated survey in order to mitigate social desirability biases and priming effects.

Stimuli

To ensure external validity of the study, three actual print advertisements by three different airlines were selected – one ad by Eurowings (“Eurowings: ‘Just fly there’ by Lukas Lindemann Rosinski,”, Citation2018) one ad by Turkish Airlines (Citation2018) and one ad by Lufthansa (Citation2018). The ads were chosen based on their desirable but varying representation of different vacation spots.

The counter-campaign ads draw closely on the wording of actual campaigns by an environmental NGO, a governmental body and an airline (European Comission, Citation2019; “Flugverkehr und Citation3. Piste [Flight traffic and 3rd runway]”, Citation2019; KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, Citation2019) but were shortened and partly translated into German to make them comparable to the flight advertising in persuasive strength, length and processing effort. Participants evaluated the counter-campaign as equally professional as the original flight ads, t(198) = 0.05, p = .964, 95%, CI[−0.22; 0.23]. Since the stimuli show original material, they will not be displayed in the manuscript, but will be provided upon request by the authors.

Measures

If not stated otherwise, metric measures used a seven-point Likert scale with 1 indicating the lowest level and 7 indicating the highest level.

Mediators

Principal component analysis

We empirically tested the underlying factor structure of moral disengagement before proceeding with forming indices. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure suggests sampling adequacy, KMO = .87. A principal component analysis (oblimin rotation, for factor loadings of the pattern matrix see ) revealed three components with eigenvalues that exceed Kaiser’s criterion of 1. Together, these three factors accounted for 65.12% of the variance. An inspection of the loadings suggested that two theoretically distinct mechanisms, namely the mechanisms of advantageous comparison and minimizing consequences, load together on one common factor. This is sensible: Both mechanisms explain how individuals are able to see the act of flying as harmless, either by neglecting efficacy (e.g. “It is useless to stop flying as a single person”) or by comparing flying to other behaviors (e.g. “To fly once a year is not as harmful as acts that others are taking day by day”). Therefore, we combine the measures of both disengagement strategies into one strategy labelled neglecting consequences. The other proposed mechanisms of moral justification and displacement of responsibility formed one component respectively. Taking a cut-off point of .4 as indication (Field, Citation2013), no cross loadings were found (see ).

Table 1. Pattern matrix of a principal component analysis on moral disengagement strategies using oblimin rotation.

Neglecting consequences

As discussed in the previous section, neglecting consequences was measured with items of two different concepts (M = 4.14, SD = 1.53, α = .87): Three items from the concept of advantageous comparison were adapted from Moore et al. (Citation2012) to fit the context of flying. Second, we included measures of individuals’ propensity to minimize the consequences of their own flight behavior. Five items taken from the concept of perceived consumer effectiveness (Kim & Choi, Citation2005) were rephrased for the issue of climate change and flight behavior.

Moral justification

Six items tapped the degree to which participants support justifications for flying, three items of which were designed to capture the cosmopolitan dimension of flying (e.g. “It is okay to fly to get to know the world in all its facets”) and three items measured the social dimension of flying (e.g. “Without flying it is not quite possible to be there for specific friends and family”). Both dimensions loaded on one factor which reached a satisfying level of reliability (M = 3.88, SD = 1.42, α = .88).

Displacement of responsibility

Displacement of responsibility (M = 5.88, SD = 1.18, α = .94) was measured with six items adapted from Kals et al. (Citation1998). Participants were asked to indicate how important it is that the government, airlines or industries work on solutions to stop the use of fossil fuels or CO2 emissions caused by the aviation sector.

All items can be found in .

Moderators

Climate change concern

Climate change concern (M = 3.88, SD = 1.42, α = .93) was measured by four items taken from Metag et al. (Citation2017; e.g. “Climate change is a severe problem”).

Dependent variables

Flying intention

Six questions were combined to an index of flying intentions (M = 3.86, SD = 2.06, α = .96), e.g. asking individuals how likely they will fly for their next holidays or if they plan to fly for their next holidays.

Policy support

Participants were asked to indicate their support for three policies (M = 4.78, SD = 1.69, α = .85): Whether they would support 1) that CO2 compensation programs should be obligatory for air travelers; 2) that taxes on kerosene would be raised; and 3) that air travelers pay an additional tax for long-distance flights.

Control variables

In addition, a number of control variables were included.

Flight frequency (M = 3.04, SD = 1.92, α = .75) was indicated by an index which combined answers to the questions how often participants have spent their holidays abroad within the last three years, how many flights they took and how often they use airplanes as a mean of transport.

Ad evaluation (M = 4.92, SD = 1.28, α = .92) and campaign evaluation (M = 5.43, SD = 1.25, α = .93) were measured by a set of six semantical differentials, e.g. asking participant how professional or unprofessional or how credible or not credible they found the article.

Exposure time to the ad (M = 17.16, SD = 14.15) and exposure time to the campaign (M = 20.22, SD = 22.23) was measured in seconds between opening the page of the articles and proceeding to the next page.

In addition, conventional demographic controls of age, gender and level of education were controlled for in each model.

Randomization check

A randomization check for age (F(2, 199) = .58, p = .561), gender (χ2(2) = 1.55, p = .460), education level (χ2(12) = 5.81, p = .925), climate change concern (F(2, 196) = .57, p = .569) and flight frequency (F(2, 196) = 1.46, p = .235) returned satisfactory results by showing no systematic differences between the experimental groups.

Manipulation check

To test whether the manipulation was successful we asked participants on a seven-point scale (1 = do not agree; 7 = strongly agree) to what extend the ad dealt with air travel as well as whether the campaign they saw dealt with the harmful impact of flying. Participants in the campaign group and the ad group show significantly higher agreement with the statement that the ads dealt with air travel as compared to the control group, F(2, 196) = 140.11, p < .001. Participants who were assigned to the counter-campaign group show significantly higher agreement that the counter-campaigns dealt with the harmful impact of flying than participants in the ad group and the control group, F(2, 196) = 111.60, p < .001).

Results

In a first step, a series of regression analyses was conducted to see how flight ads and a counter-campaign affect strategies of moral disengagement (H1–H5, RQ1). In addition, the models included the interaction between the stimulus and climate change concerns to test whether the effects of advertising might differ between individuals which score high or low on climate change concern (H6). The moderator was mean-centered, which allows for the interpretation of the direct effects in the model. The detailed results are presented in .

Table 2. Moderated effects of flight advertisements and counter-campaigns on moral justification.

Table 3. Moderated effects of flight advertisements and counter-campaigns on neglecting the harm of flying.

Table 4. Moderated effects of flight ads and counter-campaigns on displacement of responsibility.

The results show that H1 has to be rejected: Moral justification was not affected by seeing a flight ad (b = 0.03, SE = 0.23, p = .908) as compared to the control group. Also, effects did not differ between individuals with different levels of climate change concern, as the non-significant interaction term suggests (b = −0.26, SE = 0.21, p = .223).

Since the strategies of advantageous comparison (H2) and minimizing of consequences (H3) are influenced by one underlying factor, both concepts are merged into the concept labeled neglecting consequences (). A regression analysis revealed no direct effect of seeing flight ads on individuals’ propensity to neglecting the harm of flying, b = −0.24, SE = 0.24, p = .309. However, climate change concerns affected individuals’ susceptibility to the flight ad, as can be seen from a significant interaction term of b = −0.53, SE = 0.22, p = .020. According to a Johnson-Neyman test (Hayes & Matthes, Citation2009), individuals high in climate change concern (above the value of 6.54 on a 7-point scale) significantly increased their perception of flying as harmful, while individuals with low levels of climate change concern (below the value of 2.12) exhibited the opposite pattern as a response to the flight ad. Thus H2, H3 and H6 are partly accepted.

Next, the effect of exposure to flight ads on the displacement of responsibility was examined (H4). Individuals in the advertising group (b = 0.50, SE = 0.18, p = .007) showed a significant increase in their agreement that state actors and commercial actors are responsible to tackle the aviation problem. This effect applied to all participants regardless of their level of climate change concern as indicated by the non-significant interaction term, b = −0.02, SE = 0.17, p = .901.

In regard to RQ1, the campaign group significantly differed from the control group in their increased use of the strategy of displacement of responsibility (b = 0.55, SE = 0.18, p = .003). There was no significant difference between individuals in the campaign group and the control group for the strategies of moral justification (b = −0.19, SE = 0.23, p = .392) or neglecting consequences (b = −0.03, SE = 0.23, p = .911).

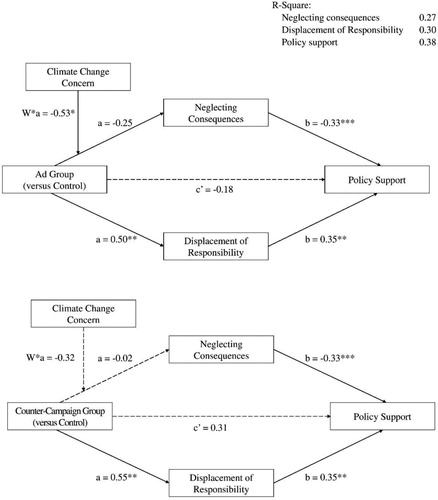

Next, we examined whether the mechanisms of moral disengagement are related to a heightened intention to fly (H5a) and lead to the rejection of aviation policies that increase the costs of flying (H5b). Two path models of moderated mediations were tested using bootstrapping technique with 5000 bootstrap samples in the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, Citation2012). Since individuals’ moral justification was not affected by the experimental manipulation and the interaction terms between the experimental manipulation and climate change concern on the strategy of displacement of responsibility was not significant, both paths were omitted from the final model.

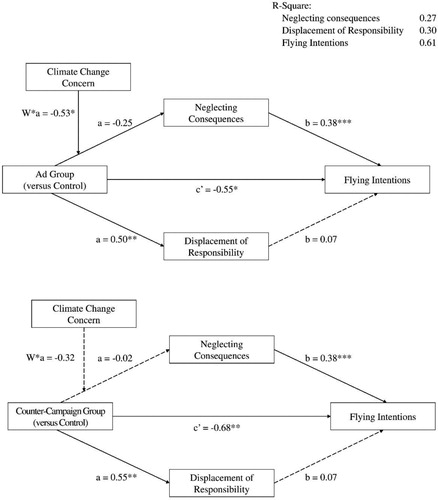

Firstly, we tested the mediating effects of moral disengagement strategies on individuals’ flying intentions. As can be seen from , neglecting the harm of flying resulted in higher levels of flying intentions, b = 0.38, SE = 0.08, p < .001, CI[0.22; 0.54] while there was no clear influence of the displacement of responsibility, b = 0.07, SE = 0.10, p = .535, CI[−0.16; 0.25]. The indirect effects of flight advertising and counter-campaigns depended on individuals’ level of climate change concern. Individuals high in climate change concern (+1SD) lowered their intentions to fly through reducing their levels of neglect of the consequences when seeing the flight ad, b = −0.34, SE = 0.15, p = .024, CI[−0.66; −0.07]. However, the indirect path for individuals with average levels of climate change concern, b = −0.10, SE = 0.09, p = .31, CI[−0.29; 0.08], or low levels of climate change concern (−1SD), b = 0.15, SE = 0.15, p = .323, CI[−0.14;0.45], failed to reach statistical significance. Thus, H5a receives only partial support. In addition, the advertising group, b = −0.55, SE = 0.25, p = .029, and the counter-campaign group, b = −0.677, SE = 0.23, p = 0.003, reduced flying intentions as the result of a direct effect.

Figure 2. Path model of indirect effects of flight advertisements on the evaluation of flying intentions.

Lastly, policy support as a function of moral disengagement strategies was tested. The results indicated that both the strategy of neglecting consequences (b = −0.33, SE = 0.08, p < .001, CI[−0.49; −0.17]) and the strategy of displacement of responsibility (b = 0.35, SE = 0.12, p = .003, CI[0.13; −0.59]) act as significant predictors for policy support. However, while minimizing the consequences led to lower levels of policy support, displacement of responsibility increased policy support among participants (see ). Thus, H5b is partially supported.

The ad group showed no significant effect (b = 0.18, SE = 0.10, p = .067, CI[0.03; 0.40]), while the counter-campaign group (b = 0.19, SE = 0.09, p = .033, CI[0.05; 0.40]) showed a significant effect on policy support via the displacement of responsibility. In addition, individuals high in climate change concern (+1SD) showed an increase in policy support when exposed to flight advertising through their reduction in neglecting consequences, b = 0.29, SE = 0.14, p = .040, CI[0.06; 0.60]. For an overview of the hypotheses, see .

Table 5. Overview of the hypotheses.

In order to assess the possible impact of case exclusion, the analyses were repeated using the full data set. The pattern of results did not change with one exception: The indirect effect of the counter-campaign group on flying intentions, b = 0.29, SE = 0.15, p = 0.045, CI[0.03;0.61], via individuals’ strategy of neglecting consequences turned significant for participants low in environmental concern (−1SD). However, since the exclusion of cases was conducted in order to ensure data quality, these effects are not considered robust.

Discussion

Climate change communication has centered around the question of how the complex science of climate change can be communicated in order to educate and inform citizens. Scholarship on this issue has greatly improved our understanding of how to frame climate change and tailor messages to different audiences (Cook & Lewandowsky, Citation2016; Hart & Nisbet, Citation2012; Nisbet et al., Citation2013). However, there is still one major challenge ahead: Linking the understanding of climate change generated by such messages to behavior, or in other words, translating knowledge into action.

By addressing the issue of aviation, the following study offers a unique perspective on how individuals navigate the friction between their environmental values and the desire for unsustainable behavior triggered by advertising. We approached the issue from the theoretical perspective of moral disengagement (Bandura, Citation1999; Citation2016) which explicates how individuals justify harmful actions without self-condemnation. Our findings from an experimental study in Germany demonstrate that flight advertising can prompt two moral disengagement strategies: neglecting the negative consequences of flying and displacing responsibility to other actors. Engaging in one or more of these strategies correlates with increased flying intentions and is related to policy support for regulating the aviation sector.

Specifically, we find that flight advertisements have a diametrically opposed effect on people with different levels of climate change concern. For those with low levels of concern, flight advertisements elicit neglect of the negative consequences of air travel. On the contrary, individuals high in climate change concern react with resistance: They tend to stress the harmfulness of aviation and the importance of abstaining from flying. This finding supports previous studies in the field of science communication, which provide evidence for a polarizing potential of climate change messages (Cook & Lewandowsky, Citation2016). In addition, the findings lend support to boundary conditions for moral disengagement such as strong pre-existing values (Aquino et al., Citation2007; see also Bandura, Citation2016).

We also find that both the ad condition and seeing the ad accompanied by a counter-campaign leads to a heightened displacement of responsibility. Thus, state actors and commercial actors are increasingly held liable for the negative effects of aviation as a response to advertising. Neither climate change concern nor a counter-campaign weakened individuals’ displacement of responsibility. One explanation for this finding could be the nature of this specific moral disengagement strategy. Displacing responsibility does not mean that the harmfulness of the action has to be minimized – individuals can be well aware of the negative impact of flying, while simply displacing the locus of action to maintain their self-worth (Bandura, Citation2016; Heald, Citation2017). So even highly climate change concerned individuals and those whose environmental values have been activated by a counter-campaign (see e.g. Defever et al., Citation2011) can disengage through this strategy.

To test another strategy, we measured the degree to which individuals find moral justifications for flying. However, we found no evidence that advertising affects moral justification. This null finding might be due to the specific selection of ads, which presented beautiful and exotic places, but did not highlight the cultural or social aspects of flying.

Furthermore, the triggered disengagement strategies play a mixed role in subsequent behavioral intentions. When individuals neglect the consequences of flying, they indicate more pronounced intentions to fly. In addition, they show a decreased level of policy support for setting higher prices on greenhouse gas emissions in the aviation sector. However, the analysis of the full model shows only limited support for a mediated effect of advertising through neglecting consequences. The indirect effect of flight ads on flying intentions and policy support reaches statistical significance only for highly climate change concerned individuals. This suggests that those high in climate change concern in fact lower their intention to fly and heighten their policy support as a result of ad exposure.

In addition, we also find evidence that the strategy of displacement of responsibility affects policy support. However, the direction of the effect indicates that policy support is heightened, not reduced, by this moral disengagement strategy. This is sensible, as individuals might feel that it is difficult for them as individuals to resolve the conflict between the provoked desires and their moral obligation to be environmentally conscious. In the larger context, this indicates that flight advertisements result in greater public support for regulations in the aviation sector. As a result, there could be unintended positive side effects of this strategy, as it shifts the perspective from the individual consumer to solutions on the political level (see also Young et al., Citation2014). This is also reflected in a recent study in Germany, which found that support for ambitious policy measures is currently heightened due to current discourses about the harmfulness of flying (Gössling et al., Citation2020).

Lastly, we posed the following research question: Would counter-campaigns that highlight the negative effects of flying be able to reduce or strengthen moral disengagement? On the one hand, participants in the counter-campaign group increased their level of displacement of responsibility when compared against the control group. On the other hand, this study only provides a blurred picture of the campaigns’ potential to counter the strategy of neglecting consequences of flying. The counter-campaign group did not statistically differ in the level of neglecting consequences from both the ad group and the control group. Therefore, neither a reduction of certain strategies through message factors (see e.g. Hartmann & Vorderer, Citation2010) nor an overall increase in moral disengagement seem likely from the pattern of our data. Subsequently, more research is needed to clarify this question.

Although this was not the prime focus of our research, we also observed interesting patters in regard to the sociodemographic control variables gender and education that deserve further attention in future research (see ). More precisely, participants of male gender and lower education indicated a more pronounced use of moral disengagement strategies, especially in those where responsibility is ascribed to others. These results match those observed in earlier studies. Regarding gender, women are more concerned about environmental issues, more willing to change their behavior, and tend to be more active in everyday environmentally friendly behavior (Fliegenschnee & Schelakovsky, Citation1998; Lehmann, Citation1999; Tindall et al., Citation2003). These previous findings imply that women see environmental issues as their individual responsibility, and might therefore be less likely to attribute the responsibility of climate change to other actors.

Regarding education, previous research has found a connection between education and pro-environmental behaviors like environmentally friendly travel (see e.g. Meyer, Citation2015). Moreover, it is believed, that formal education has a positive effect on “environmental willingness to contribute” (Torgler & Garcia-Valinas, Citation2007, p. 538). It is argued that the connection between high education and pro-environmental behavior can be explained by a higher awareness about the possible environmental damage and by higher income (Torgler & Garcia-Valinas, Citation2007). Rephrased, higher educated individuals are more able and willing to contribute to environmental protection. Consequently, they might be less likely to shift responsibility to outside sources. These finding suggests that, when creating awareness campaigns that promote environmental protection, policy makers should focus increasingly on the audience of lower educated men. However, further research is required to establish the influence of gender and education on moral disengagement strategies and environmental behavior.

On a theoretical note, our findings are consistent with the still underexplored idea that moral disengagement strategies are prompted by situational factors (but see Hartmann & Vorderer, Citation2010). Therefore, we are confident that investigating contextual factors such as the exposure to media messages could be a fruitful avenue for future research into moral disengagement strategies.

Limitations and future research

There are several limitations to our approach. Firstly, the proposed theoretical model would largely profit from a larger sample size. Since there are multiple paths in our analysis, non-significant indirect effects might be due to a lack of power in our study. In addition, the mediation model only gives us correlational, not causal evidence for a relationship between moral disengagement strategies and outcome variables. While the order investigated in our study is derived from theory, it is also possible that the relationship is reversed.

As a second point, the national context of this study has to be taken into consideration. In the case of Germany, climate change is largely accepted as real and anthropogenic (European Comission, Citation2017). In countries where the science of climate change is subjected to partisan discussions, the results might differ.

While we are confident that we covered important mechanisms of moral disengagement, there are several other ways described by Bandura (Citation1999, Citation2016) to morally disengage from detrimental actions. Especially in other national contexts, the strategy of minimizing consequences might take the form of climate science denial (see e.g. Heald, Citation2017). Since the question of victimhood seemed diffuse and hard to answer in the context of aviation, we did not investigate the strategy of blaming the victim. However, this does not mean that the strategy isn’t central for other environmental topics.

Lastly, it would be insightful to identify different frames and media of flight advertisements and compare their effects on moral disengagement. Thus, there is still room for further research to validate and extend the findings of the current study.

Practical implications

In the light of this study, the susceptibility to flight ads can be viewed from two sides: On the one side, it is important that individuals in Western societies adapt their lifestyles to ensure a sustainable future. Therefore, future research and counter-campaigns by NGOs or governmental actors could try to help individuals to build more resistance against persuasive attempts by advertisements for carbon intensive products. On the other side, however, the study also shows that it might be problematic to blame individuals for the full environmental damage of their consumption choices when they are simultaneously confronted with advertising messages every day. As long as status is assigned to flying, may it be through advertisements, articles or travel bloggers, individuals will have a social incentive to fly (Young et al., Citation2014) – and to morally disengage from their actions.

Declaration of interest

No financial interest or benefit that has arisen from the direct applications of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated at the University of Vienna. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- Aquino, K., Reed, A., Thau, S., & Freeman, D. (2007). A grotesque and dark beauty: How moral identity and mechanisms of moral disengagement influence cognitive and emotional reactions to war. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.013

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

- Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth Publishers.

- Blake, J. (1999). Overcoming the ‘value-action gap’ in environmental policy: Tensions between national policy and local experience. Local Environment, 4(3), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839908725599

- Brüggemann, M., & Engesser, S. (2017). Beyond false balance: How interpretive journalism shapes media coverage of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 42, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.11.004

- Calhoun, C. (2002). The class consciousness of frequent travelers: Toward a critique of actually existing cosmopolitanism. South Atlantic Quarterly, 101(4), 869–897. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-101-4-869

- Cartledge, S. M., Bowman-Grieve, L., & Palasinski, M. (2015). The mechanisms of moral disengagement in George W. Bush’s “War on terror” rhetoric. Qualitative Report, 20(11), 1905–1921. http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol20/iss11/1

- Chryst, B., Marlon, J., van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., & Roser-Renouf, C. (2018). Global warming’s “Six americas short survey”: audience segmentation of climate change views using a four question instrument. Environmental Communication, 12(8), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1508047

- Cohen, S. A., Higham, J. E. S., & Cavaliere, C. T. (2011). Binge flying. Behavioural addiction and climate change. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1070–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.013

- Cook, J., & Lewandowsky, S. (2016). Rational irrationality: Modeling climate change belief polarization using Bayesian networks. Topics in Cognitive Science, 8(1), 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12186

- Davison, L., Littleford, C., & Ryley, T. (2014). Air travel attitudes and behaviours: The development of environment-based segments. Journal of Air Transport Management, 36, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2013.12.007

- Defever, C., Pandelaere, M., & Roe, K. (2011). Inducing value-congruent behavior through advertising and the moderating role of attitudes toward advertising. Journal of Advertising, 40(2), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367400202

- European Comission. (2017). Special Eurobarometer 459. Climate Change. Retrieved September 20, 2019, from https://ec.europa.eu/clima/sites/clima/files/support/docs/report_2017_en.pdf.

- European Comission. (2019). Reducing emissions from aviation. Retrieved September 19, 2019, from https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport/aviation_en.

- Eurowings: “Just fly there” by Lukas Lindemann Rosinski. (2018). Adruby.Com. https://www.adsoftheworld.com/media/print/eurowings_just_fly_there_3.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (3rd Edition). Sage.

- Fliegenschnee, M., & Schelakovsky, M. (1998). Umweltpsychologie und Umweltbildung: Eine Einführung aus humanökologischer Sicht. Facultas Universitäts-Verlag.

- Flugverkehr und 3. Piste [Flight traffic and 3rd runway]. (2019). System Change Not Climate Change. https://systemchange-not-climatechange.at/de/stopp-3-piste/.

- Fransson, N., & Gärling, T. (1999). Environmental concern: Conceptual definitions, measurement methods, and research findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19(4), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0141

- Gössling, S., Humpe, A., & Bausch, T. (2020). Does ‘flight shame’ affect social norms? Changing perspectives on the desirability of air travel in Germany. Journal of Cleaner Production, 266, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122015

- Hart, P. S., & Nisbet, E. C. (2012). Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research, 39(6), 701–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211416646

- Hartmann, T., & Vorderer, P. (2010). It’s okay to shoot a character: Moral disengagement in violent video games. Journal of Communication, 60(1), 94–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01459.x

- Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

- Heald, S. (2017). Climate silence, moral disengagement, and self-efficacy: How Albert Bandura’s theories inform our climate-change predicament. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 59(6), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2017.1374792

- Hibbert, J. F., Dickinson, J. E., Gössling, S., & Curtin, S. (2013). Identity and tourism mobility: An exploration of the attitude–behaviour gap. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(7), 999–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.826232

- Hope, A. L. B., Jones, C. R., Webb, T. L., Watson, M. T., & Kaklamanou, D. (2018). The role of compensatory beliefs in rationalizing environmentally detrimental behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 50(4), 401–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517706730

- Hughes, D. M. (2013). Climate change and the victim slot: From oil to innocence. American Anthropologist, 115(4), 570–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12044

- Kals, E., Montada, L., Becker, R., & Ittner, H. (1998). Verantwortung für den Schutz von Allmenden. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 7(4), 296–303. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.7.4.10

- Kim, Y., & Choi, S. M. (2005). Antecedents of green purchase behaviour: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and Pce. Advances in Consumer Research, 32, 592–599. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/9156/volumes/v32/NA-32.

- KLM Royal Dutch Airlines. (2019). Fly responsibly. Retrieved September 23, 2021, from https://flyresponsibly.klm.com.

- Koos, S., & Naumann, E. (2019). Vom Klimastreik zur Klimapolitik: Die gesellschaftliche Unterstützung der„Fridays for Future“-Bewegung und ihrer Ziele: Forschungsbericht. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from http://kops.uni-konstanz.de/bitstream/handle/123456789/46901/Koos_2-1jdetkrk6b9yl4.pdf?sequence¼1.

- Lehmann, J. (1999). Befunde empirischer Forschung zu Umweltbildung und Umweltbewusstsein. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-99534-

- Lufthansa. (2018, Feburary 2). Herkunft trifft Zukunft. Lufthansa stellt neues Markendesign vor. https://www.lufthansagroup.com/media/_processed_/2/4/csm_explorethenew-499384_d7e9858966.jpg

- Metag, J., Füchslin, T., & Schäfer, M. S. (2017). Global warming’s five Germanys: A typology of Germans’ views on climate change and patterns of media use and information. Public Understanding of Science, 26(4), 434–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662515592558

- Meyer, A. (2015). Does education increase pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecological Economics, 116, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.04.018

- Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

- Nisbet, E. C., Hart, P. S., Myers, T., & Ellithorpe, M. (2013). Attitude change in competitive framing environments? Open-/closed-mindedness, framing effects, and climate change. Journal of Communication, 63(4), 766–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12040

- Obermann, M.-L. (2011). Moral disengagement in self-reported and peer-nominated school bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 37(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20378

- Randles, S., & Mander, S. (2009). Aviation, consumption and the climate change debate: ‘Are you going to tell me off for flying? Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 21(1), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320802557350

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. Retrieved September 23, 2021, from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Schneider, C. R., Zaval, L., Weber, E. U., & Markowitz, E. M. (2017). The influence of anticipated pride and guilt on pro-environmental decision making. PLOS ONE, 12(11), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188781

- Skrbis, Z., Woodward, I., & Bean, C. (2014). Seeds of cosmopolitan future? Young people and their aspirations for future mobility. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(5), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.834314

- Swim, J. K., & Geiger, N. (2017). From alarmed to dismissive of climate change: A single item assessment of individual differences in concern and issue involvement. Environmental Communication, 11(4), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2017.1308409

- Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (2004). Ethical fading: The role of self-deception in unethical behavior. Social Justice Research, 17(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SORE.0000027411.35832.53

- Tindall, D. B., Davies, S., & Mauboules, C. (2003). Activism and conservation behavior in an environmental movement: The contradictory effects of gender. Society and Natural Resources, 16(10), 909–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/716100620

- Torgler & Garcia-Valinas. (2007). The determinants of individuals’ attitudes towards preventing environmental damage. Ecological Economics, 63(23), 536–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.12.013

- Turkish Airlines. (2018, February 6). We all spend so much time looking where we're going that we forget to look elsewhere for the beauty that's all around us! &hash;WidenYourWorld [Twitter]. https://twitter.com/TurkishAirlines/status/960861614403661824/photo/1

- Young, M., Higham, J. E. S., & Reis, A. C. (2014). ‘Up in the air’: A conceptual critique of flying addiction. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.003