ABSTRACT

Public perception of drought is an important factor in sustainable water use. Heightened media coverage of drought events is shown to reduce public water consumption. This research examined Ireland's 2018 summer drought to identify how drought was framed in three broadsheet newspapers through a media content analysis over 19 weeks. Ireland provided a novel case study due to its rainy climate and lack of drought management strategies. Since the 1970s, few hydrological droughts occurred in Ireland, but forecasts indicate the country is likely to experience greater precipitation deficits in summer. In Ireland, as elsewhere, greater understanding of behavioural change and water conservation communication is needed given projected trends for increased frequency and severity of drought events. This research explored water conservation communication in the media to support better public response to future droughts in Ireland and elsewhere. Results demonstrated delayed media coverage of the drought and insufficient advice may have hampered public water conservation efforts. In addition, the role of climate change in exacerbating drought was under and misrepresented, potentially discouraging mitigative behaviours and acceptance of climate and water management policies. Earlier coverage of impending droughts with relevant advice could improve public efforts in water conservation and drought adaptation.

1. Introduction

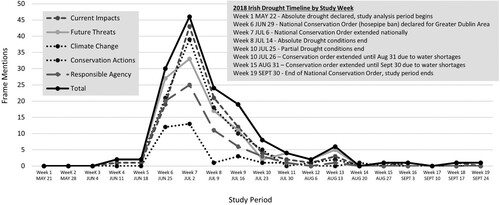

In the summer of 2018, Ireland experienced drought conditions due to a prolonged extreme heatwave and negligible rainfall. The timeline of events surrounding the drought is presented in , beginning with absolute drought conditions declared across the country from 22 May to 14 July 2018, with partial drought conditions nationwide until July 28 (Met Eireann, Citation2019). The drought proved overwhelming for the Irish public water services as rising temperatures in late May 2018 resulted in a 15% increase in water usage by the public, leaving public water supplies under severe stress (Irish Water, Citation2018). On 29 June 2018, the national public utility, Irish Water, enforced a National Water Conservation Order (also known as a hosepipe ban) for the Greater Dublin Area, which was extended nationally on 6 July 2018 (Irish Water, Citation2019a). The order was applied to all domestic users and to non-commercial use by commercial bodies prohibiting “the use of water drawn through a hosepipe or similar apparatus”. Additional activities were prohibited under the order, including watering a garden; washing a private vehicle; and filling or maintaining a domestic swimming or paddling pool, pond or ornamental fountain. However, the order did not apply to the commercial or agricultural sectors. Extensive coverage of the drought was broadcast through all forms of Irish media during this period, including national television, radio, newspapers and social media. The aim of this research is to explore how the 2018 drought was portrayed in popular Irish broadsheet newspapers using media framing as a systematic analysis to identify media intentions and describe trends in drought communication content (Bayulgen & Arbatli, Citation2013). Because the National Conservation Water Order did not relate to the commercial or agricultural sectors, the scope of the research was necessarily focused on broadsheet media coverage of water use in the residential sector which was directly impacted by the position of new measures.

A media frame is a written, spoken, graphical or visual message designed to intentionally emit relevant information to purvey judgement on a topic (Goffman, Citation1974). While media has a significant impact on risk perception, public opinion also shapes media framing. This can, in turn, affect decision makers and policy development, consequently inhibiting or propelling societal perceptions of responsibility and risk management (Kasperson et al., Citation1998; Devitt & O’Neill, Citation2016). The public’s perception of drought is an important factor to ensure sustainable water usage by encouraging behavioral change and has been explored in several studies (Dessai & Sims, Citation2010; Igartua et al., Citation2011). Heightened media coverage on drought events has been shown to reduce water usage by up to 18% in California, where droughts are more common than in Ireland (Quesnel & Ajami, Citation2017). However, the limited research examining the framing of drought and associated impacts in mass media to date focuses primarily on the responsible agencies or actors within water management (Medd & Chappells, Citation2007) rather than risk perception and encouraging behavioral changes in the public.

Rainfall is particularly prominent on the western side of Ireland (1200 mm average), which receives almost twice as much annual rainfall as the east of the country (875 mm average) (Noone et al., Citation2015). Ireland’s wet weather patterns are reflected through the country’s risk management policies geared towards flood management, while neglecting issues such as drought. However, under the EU Water Framework Directive 2006/60/EC, Ireland is responsible for protecting and maintaining groundwater bodies and catchment areas to ensure the long-term sustainability of its water resources (EPA, Citation2019a). The Irish Water Strategic Funding Plan of 2018 provided €11 billion to modernize national water services, including €6.1bn investment to ensure a sustainable and reliable drinking water supply for Ireland (Irish Water, Citation2019b). Ireland’s National Adaption Framework of 2018 acknowledged the recent impacts of drought but failed to suggest or implement any adaptive or mitigative strategy (DCCAE, Citation2019). To date, no national policy has been developed to address drought risk management in Ireland. With drought conditions expected to intensify in the future as a result of climate change (Holden & Brereton, Citation2002; Roudier et al., Citation2016), a lack of policies to respond to drought with appropriate water conservation strategies could pose further risk to the Irish economy and public water resources.

1.1. Study objective and research question

Public awareness of water- and drought-related issues is an important yet relatively unexplored component of water use behavior (Quesnel & Ajami, Citation2017). Previous research on communication of water management mainly focuses on the issue of water reuse rather than natural hazards such as drought (Hurlimann & Dolnicar, Citation2012). The objective of this research was to ascertain the nature and scope of broadsheet media coverage of the 2018 summer drought in Ireland as a country that is not typically associated with droughts yet one which will experience more droughts in the future due to climate change (IPCC, Citation2007). The case study was driven by the research question: How was the broadsheet media coverage of Ireland’s 2018 summer drought framed? Having established these frames, the study explored the possible implications of these frames on the public’s willingness to engage in drought mitigation through residential water conservation, focusing particularly on the media’s role in communicating drought information to the public and the framing of the parties responsible for drought mitigation. As drought is among the most likely impacts of climate change (IPCC, Citation2007) and improved understanding of impacts and vulnerabilities is critical in adapting to climate change (Dow, Citation2010), the role of climate change in media framing of the drought was also explored. Research has shown that, in the absence of alternative frames, those presented in the media will have a particular effect on the response of audiences and on the level of public debate on risk and willingness to adopt mitigation measures (Devitt & O’Neill, Citation2016). There are consequences for policy implementation in terms of public acceptance and participation (Harries & Penning-Rowsell, Citation2011). If individuals have to interpret misleading information, a loss of belief in the reality of climate change might ensue (Whitmarsh, Citation2011).

2. Methodology

Content analysis was applied to explore the relationship between media framing and how it governed the portrayal of the 2018 drought in the Irish broadsheet media. The study applied the four-step methodology detailed for appropriate content analysis of broadsheet sources as follows:

Step 1 – Data collection

Step 2 – Thematic coding of articles

Step 3 – Variable coding of article content

Step 4 – Results

2.1. Data collection (Step 1)

Ireland’s three major broadsheet newspapers were selected for use in this study. Evidence has shown that broadsheets are more effective than tabloid media outlets in providing readers with a robust, informative grasp of issues (Fraile & Iyengar, Citation2014). The distinction between the effects of public exposure to both sectors of print media is confirmed by previous studies (Barabas & Jerit, Citation2009; Curran et al., Citation2009). While acknowledging the views of members of the public expressed in emphatic terms online and in social media, it was also accepted that online/social media comment was not fully representative of the opinions of the broader population (Regan et al., Citation2014). Such comments are more likely to be negative or extreme in terms of the blame or responsibility for meeting climate-related hazards (Beninger et al., Citation2014; Regan et al., Citation2014). Consequently, these media sources were considered beyond the remit of this research insight paper.

Broadsheet newspapers are most likely to be influential in terms of policy development (Carvalho and Burgess, Citation2005). In addition, broadsheet newspapers are considered a reliable source of information while also holding influence over other media sources and political conversation (Pollard, Citation2019; Devitt & O’Neill, Citation2016). The Irish Independent (II), The Irish Times (IT) and The Irish Examiner (IE) were analysed over a 19-week period through Ireland’s 2018 drought in alignment with drought weather reports from Met Eireann between 22nd May to 30th September 2018. Marron (Citation2019) suggested that although all three sources were broadly centrist, The Irish Times orientation was more socially liberal and economically conservative, while the Irish Independent was more pro-business; and the Irish Examiner, based in Cork, provided more regional perspective on issues.

Selected newspaper articles were retrieved through LexisNexis online newspaper archives. Searches were performed using keywords drought, hosepipeFootnote1 and water to ensure material was relevant. These search parameters yielded 182 results, 34 of which were deemed irrelevant as they did not speak of the drought in an Irish context. A total sample of N = 148 newspaper articles was generated. presents the number of articles analysed and daily readership by publication while displays the number of relevant articles published weekly by each newspaper over the period analysed.

Table 1. Daily circulation figures for Ireland’s top three national newspapers (ABC Irish Newspaper Circulation, Citation2018) and drought related articles analysed in this study.

2.2. Thematic coding of articles (Step 2)

This study adopted a conventional content analysis process to assess framing in the acquired data.

As such, frames were not preconstructed but emerged from the data upon analysis (Kondracki et al., Citation2002). Due to the small sample size, a qualitative approach to examining the context and content of language used in each article enabled the identification of multiple frames and variables and thereby optimized insights from the sample (Peltomaa & Kolehmainen, Citation2017).

Five keyframes were identified from analysis of 148 newspaper articles: current impacts; future threats; climate change; conservation actions; and responsible agencies. These frames were chosen for analysis as they presented most frequently during the initial reading and screening phase. Parameters for how each frame and variable were coded are outlined in along with exemplars from the broadsheet newspapers. To avoid possible duplication of articles and to maintain compatibility with the thematic framework and coding rules, each article was read three times by two of the research analysis team who then discussed and refined the themes (Devitt et al., Citation2019). This analysis was conducted in line with recommendations from Elo and Kyngas (Citation2008) on coding issues and any potential overlap or merging of themes.

Table 2. Frames, variables, definitions and exemplars from media framing analysis of Ireland’s 2018 summer drought.

2.3. Variable coding of article content (Step 3)

Articles were screened for recurring variables within each frame. The “climate change” frame was the only frame to include specific positive and negative variables. This resulted from the evidence in articles referring to climate change, which posited towards a perception that a greater degree of warmth and dry conditions might be beneficial to a country such as Ireland where climatic conditions in normal times are more frequently associated with the deleterious effect of excessive rainfall. Furthermore, previous research in Ireland also analysed the framing of climate change in terms of both opportunities and negative consequences (EPA, Citation2019b). Further analysis was also undertaken within the “responsible agencies” frame. This frame focused on who was responsible for alleviating the impacts of drought (the general public, Irish Water as the public water management body, or the Irish Government). The articles related to Irish Water and/or the Irish Government were further analysed to investigate if they were portrayed in a positive or negative manner.

3. Results (Step 4)

presents the number of articles relating to each of the five identified frames and the week which they were published. The study period ran for 19 weeks beginning 21 May, 2018 (Week 1) and ending in the week commencing on 24th of September (Week 19). On 22nd May of 2018, Irish Water declared absolute drought conditions nationally. However, the first reporting of drought occurred on the week of 11th June, over 20 days after official drought declaration. All five of the frames were featured in the articles from Week 5 and peaking in Week 7. “Current impacts” and “conservation actions” were particularly prominent in this time. During this period, a hosepipe ban was declared for Dublin on 29th June and extended across the country on 6th July. From Week 11 until Week 13, articles referring to “future threats” received highest coverage, reflecting concern over water shortages which had led to the extension of the hosepipe ban. The temporal trends of this media framing were potentially relevant to residential water conservation.

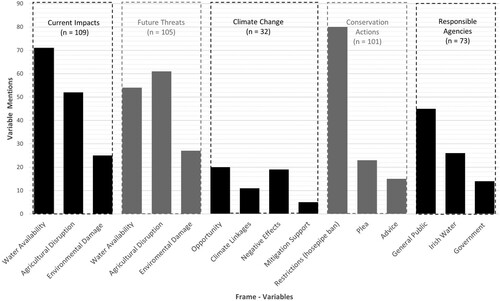

details the variable mentioned within each of the five frames (N = 148). 73.6% of the articles analysed referred to variables related to “current impacts” associated with the drought (n = 109) followed by 70.9% related to “future threats” (n = 105) and 68.2% focusing on “conservation actions” (n = 101). “Responsibility” for addressing the drought was referred to in 49% of the articles (n = 73), while references to “climate change” were identified in 22% of the articles (n = 32).

Figure 2. Variable mentions within frames in Irish broadsheet media during the summer 2018 drought (N = 148).

The majority of articles that related to “responsibility” framed the general public as responsible for the alleviation of the impacts of drought, mainly through conservation efforts. These articles occurred in the early stages of the declared drought period but diminished as the framing of responsibility transferred to Irish Water. A total of 40 articles mentioned either Irish Water’s or the Government’s responsibility to take action. Further analysis of these articles identified that 95% of them deemed the response of these agencies to be ineffective.

Water restrictions and the hosepipe ban was the most frequently cited variable, appearing in 80 of the 148 articles. Current water availability was the next most frequently cited variable, occurring in 71 articles. Framing of current water service disruption for residential estates; water shortages in hospitals; and projections on when water supply would run out all occurred during the study period. Future agricultural disruption received the third most coverage, mentioned in 62 of the 148 articles, with all three publications concerned over the threat to the agricultural sector. Similar to the framing of current impacts, framing of future threats to the agricultural sector outnumbered those of water supply and environmental threats. When “climate change” was discussed, it was primarily framed as a positive opportunity or a negative effect, the former representing the possible benefits that come with atypical warm and dry weather and the latter depicting the dangers of climate-associated events such as drought.

4. Discussion

Ireland experienced several extreme weather events in the months leading up to the 2018 summer drought, including hurricane Ophelia, heavy snowfall, cold snaps and above average precipitation (Deckard, Citation2019). These events revealed the cost of extreme weather affecting infrastructure and essential services such as water supply, which was then exacerbated by the 2018 summer drought (EPA, Citation2020). As effective communication of risk is a key influencer of the public’s risk perception and behavior, media coverage has the potential to improve drought response and reduce water usage during drought periods (Ewart, Citation2020; Igartua et al., Citation2011; Bonfadelli, Citation2010). In typically wet climates such as Ireland, a lack of personal experience with hazards such as water shortages can render individuals even more reliant on secondary information from media sources, leaving the public more susceptible to the influence of media framing (Kapuściński & Richards, Citation2016). The public are important partners in preparing for drought and responding to it, and analysis of drought reporting can provide insights into popular understanding of the relationship between water, infrastructure and consumption (Bell, Citation2009). Therefore, analysis of the broadsheet media coverage of the 2018 summer drought in Ireland supports better understanding of the Irish media’s role in water conservation and the public’s willingness to engage in drought risk management practices.

4.1. Relevance of media framing on residential water conservation

In Ireland, drought is defined as a period of 15 or more consecutive days for which no one day records more than 0.2 mm of precipitation (Wilhite & Glantz, Citation1985). However, better drought metrics exist which accumulate precipitation deficits over time to link meteorological droughts to agricultural, hydrological, socio-economic and ecological impacts. The limitation of Ireland’s current drought metric was reflected in the media coverage of drought analysed in the present study. -There was a 20-day delay between Irish Water declaring drought conditions on 22nd May and the first mention of drought on 11th June in the broadsheet media. Media coverage of drought conditions increased over subsequent weeks, peaking in week 7 and continuing into September when the National Conservation Order ended, though the drought officially ended July 25th. Reports of the hosepipe ban extension until the end of September emerged as late as August 29th. Awareness of a local drought increases rapidly through mass media reports when drought reaches its peak severity, driving increased public concern for water shortages and support for water policies (Kim et al., Citation2019). Thus, earlier coverage of impending drought, perhaps encouraged by earlier engagement with media by water management agencies, could improve public efforts in water conservation. While timing of messaging has not been considered in previous research on drought communication, existing studies have demonstrated how public information campaigns and other targeted strategies can significantly improve residential water users’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors relevant to achieving water conservation (Dziegielewski, Citation1991; Lackstrom et al., Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2021). These include elements pertaining to the content of conservation messages and to the effective means of delivering these messages to water users, in addition to using stakeholders’ preferred and existing channels to disseminate products while emphasizing impacts relevant to different user and employing concise narratives and visualizations to translate technical and scientific information.

Over half (54%) of calls of action for public water conservation in the present study focused on the evolving water restrictions and hosepipe ban. However, the public were offered sparse and irregular instruction on how to reduce domestic water consumption in other ways. Just 10% (n = 15) of articles provided advice on how to conserve water. Representation of issues through framing has the potential to affect an individual’s awareness of risk and responsibility both positively and negatively (Hart, Citation2010). Framing predominately focused on the hosepipe ban in the present study failed to reflect the seriousness of the drought conditions or the need for the public to apply additional conservation measures. Domestic water consumption in Ireland increased in 2018 compared to previous years (CSO, Citation2020). While it is not possible to attribute a definitive cause to this increase, it indicates that media reporting on Ireland’s 2018 summer drought had no long-term beneficial effect on behavioral change and residential water conservation. Ireland is the only OECD country in which households do not pay directly for the water they use, which further exacerbates water conservation efforts (O’Neill et al., Citation2018). Quesnel and Ajami (Citation2017) compared media coverage of drought periods in California to Google search frequency and confirmed that public attention followed news media trends. An increase of 100 drought-related articles in a bimonthly period was associated with an 11–18% reduction in water use. These results highlight the need for water resource planners and decision makers to further consider the importance of effective public awareness and education in water demand behavior and management. For media to effectively encourage domestic water conservation, more effort must be made to provide frequent and practical water use reduction tips to the public.

4.2. Responsibility framing

The residential sector comprised 32% of water demand in Ireland in 2018 and less than 5% percent of this was from external water use associated with hosepipes (e.g. gardening, swimming pools, water features) (CSO, Citation2020). This contrasts with the 43% of water which was unaccounted for by Irish Water due to leaks and apparent losses and a further 25% used for non-domestic and operational uses. These data indicate there is a misalignment of water conservation strategies and media framing compared to water uses. While the responsibility to mitigate the impacts of the 2018 drought was largely framed as the obligation of the public, some responsibility was also placed on both Irish Water and the Irish Government. However, there was no mention of the responsibility of agricultural, industrial or commercial sectors to also make conservation efforts during the drought period.

The framing of Irish Water or the Government largely focused on lack of foresight, infrastructure updates and policy by either body as the main source of water supply problems during the drought. This confirms research on media coverage of drought in other locations where water infrastructure and water managers also came under significant media scrutiny (Bell, Citation2009; Wei et al., Citation2015). This may be due to the politicization of the issue of water supply or a structural bias of journalistic routines which prioritize powerful actors in the news (Wei et al., Citation2015). However, Ireland’s history of water policy may also have contributed to the negative framing of Irish Water and the Government regarding the drought. Following the 2008 global financial crisis, the Irish Government introduced a household property tax and domestic water charges (both of which were absent in Ireland since the 1970s), along with the formation of a single national authority for water management, the public utility Irish Water (O’Neill et al., Citation2018). This resulted in the emergence of a water protest movement and ultimately a suspension of water charges by a new government in May 2016, though both the Irish Government and Irish Water continue to face reputational issues as a result. As with previous research, the present study confirms that water managers should ensure leakage and waste in their networks are minimized to avoid further public backlash against water restrictions and to conserve water resources. A lack of metering or water charges also interferes with the ability to link communications to water conservation.

4.3. Framing of climate change in the media

Media reporting of drought is increasingly important in shaping public understanding of climate change and environmental issues (O’Donnell & Rice, Citation2008). As water supplies in Ireland were originally built to cater for a smaller population, this vulnerability may be magnified by the impacts of climate change while highlighting the need for robust water resource management policies to ensure a safe and secure water supply in the future (EPA, Citation2020). In the present study, the topic of climate change was significantly underrepresented when compared to the framing of current impacts of drought and future threats. Understanding public perception of drought and climate change is an important factor for sustainable water management by identifying barriers to behavioral change (Dessai & Sims, Citation2011). Descriptions welcoming the warm weather and Mediterranean conditions through positive imagery around climate change provided opportunity to breed climate change scepticism among readers, which can negatively influence the adoption of mitigative behaviors and acceptance of climate and water management policies (Arbuckle et al., Citation2013; Blennow & Persson, Citation2009). While no research to date links climate change framing with water use data, evidence suggests positive imagery on climate change can confuse the public about the conclusions of climate science, reducing their willingness to engage in both adaptive and mitigative behaviors (Boykoff & Boykoff, Citation2007; Dixon & Clarke, Citation2013; Clarke et al., Citation2015; Dixon et al., Citation2015; Koehler, Citation2016; Ford & King, Citation2015). Drought communication in the media should thus recognize the link to anthropogenic climate change and the increased likelihood of weather extremes to support the behavioral changes needed for effective climate adaptation and mitigation. Increasingly, social media has also been used as a means of examining the relationship between extreme weather events and links to climate change (Robbins, Citation2018). There is some indication that this relationship intensifies when media generated science communication increases during an extreme event (Al-Saqaf & Berglez, Citation2019; Robbins, Citation2018). Future research should examine the links between climate change and Ireland’s 2018 drought to see if a similar relationship emerges.

4.4. Policy implications

Mass media can, and often do, play a critical role in policymaking (Boykoff, Citation2008; Soroka et al., Citation2013), Drought in cities provides impetus for institutional reform and infrastructure expansion (Bell, Citation2009), and financial relief decisions by governments following natural disasters are driven by news coverage of those disasters (Eisensee & Strömberg, Citation2007). Until recently, drought has been a “forgotten hazard” in Ireland with few island-wide hydrological droughts occurring since the mid-1970s (Noone & Murphy, Citation2020). This is reflected in national policy as Ireland’s first National Drought Plan has yet to be drafted and no national scale drought monitor or warning system has been established, despite climate forecasts showing Ireland has amongst the strongest trends to greater precipitation deficits in summer (Noone & Murphy, Citation2020). There is increasing concern worldwide about the ineffectiveness of current reactive drought management practices largely based on crisis management, treating the impacts of drought rather than the underlying causes (Wilhite et al., Citation2014). In Ireland, as elsewhere, the time for addressing drought risk reduction is now, given the current and projected trends for the increased frequency, severity and duration of drought events in association with a changing climate (Noone & Murphy, Citation2020). Drought resilience will also require policy coherence, including how national strategies on land use and food production influence drought risk and vice versa. Ireland’s agricultural climate adaptation plans highlight the risk of future drought periods like those of summer 2018 and suggest a variety of actions to increase resilience (Government of Ireland, Citation2020). However, these actions are primarily at farm level and/or lack Government support for implementation. The impact that future droughts could have on agricultural expansion and water management are not reflected in Irish agricultural policies, demonstrating a lack of policy coherence between water management and agricultural policies more generally by the Irish Government (Kelleher et al., Citation2019).

5. Conclusion

The overall aim of this study was to explore water conservation communication in the media to support better public response to future droughts in Ireland and elsewhere. Results demonstrated that delayed media coverage of the drought and a lack of practical advice on how to reduce water consumption may have hampered public water conservation efforts. In addition, the role of climate change in exacerbating drought was under and misrepresented in the discourse, further reducing the effectiveness of media coverage on water conservation both in the immediate and longer terms. Earlier coverage of impending drought with more practical water conservation advice could improve public efforts in water conservation and future drought risk reduction. These conclusions should assist water management agencies in developing effective public water conservation campaigns in advance of future droughts.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the information provided by Padraig Fogarty of Irish Water.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 These terms were considered most applicable to the purpose of the research due to location specific context. For example, A hose used specifically for domestic gardens and outdoor use would be encompassed by the term “hosepipe” while Sprinklers are not commonly used in Ireland.

References

- ABC Irish Newspaper Circulation. (2018). Irish Newspaper Circulation July-Dec 2018 Island of Ireland Report Print. [online]. Retrieved July 3, 2019 from http://www.ilevel.ie/print/irish-newspaper-circulation-july-dec-2018-island-of-ireland-report/

- Al-Saqaf, W., & Berglez, P. (2019). How do social media users link different types of extreme events to climate change? A study of Twitter during 2008-2017. Journal of Extreme Events, 6(2), Article 1950002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2345737619500027

- Arbuckle, J., Prokopy, L., Haigh, T., Hobbs, J., Knoot, T., Knutson, C., Loy, A., Mase, A., McGuire, J., Morton, L., Tyndall, J., & Widhalm, M. (2013). Climate change beliefs, concerns, and attitudes toward adaptation and mitigation among farmers in the Midwestern United States. Climatic Change, 117(4), 943–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0707-6

- Barabas, J., & Jerit, J. (2009). Estimating the causal effects of media coverage on policy-specific knowledge. American Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00358.x

- Bayulgen, O., & Arbatli, E. (2013). Cold War redux in US–Russia relations? The effects of US media framing and public opinion of the 2008 Russia–Georgia war. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 46(4), 513–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2013.08.003

- Bell, S. (2009). The driest continent and the greediest water company: Newspaper reporting of drought in Sydney and London. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 66(5), 581–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207230903239220

- Beninger, K., Fry, A., Jago, N., Lepps, H., Nass, L., & Silvester, H. (2014). Research Using Social Media: Users Views. London: NatCen. [Last accessed April 12, 2022 at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kelsey-Beninger/publication/261551701_Research_using_Social_Media_Users'_Views/links/0c96053497fed9ac11000000/Research-using-Social-Media-Users-Views.pdf]

- Blennow, K., & Persson, J. (2009). Climate change: Motivation for taking measure to adapt. Global Environmental Change, 19(1), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.003

- Bonfadelli, H. (2010). Environmental sustainability as challenge for media and journalism. In M. Gross & H. Heinrichs (Eds.), Environmental sociology: European perspectives and interdisciplinary challenges (pp. 257–278). Springer.

- Boykoff, M. (2008). Media and scientific communication: A case of climate change. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 305(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP305.3

- Boykoff, M., & Boykoff, J. (2007). Climate change and journalistic norms: A case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 38(6), 1190–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008

- Carvalho, A., & Burgess, J. (2005). Cultural circuits of climate change in U.K. Broadsheet Newspapers, 1985–2003. Risk Analysis, 25(6), 1457–1469.

- Central Statistics Office (CSO). (2020). CSO Statistical release - Domestic Metered Public Water Consumption 2018. Published 22 December 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020 from https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/dmwc/domesticmeteredpublicwaterconsumption2018/

- Clarke, C. E., Hart, P. S., Schuldt, J. P., Evensen, D. T. N., Boudet, H. S., Jacquet, J. B., & Stedman, R. C. (2015). Public opinion on energy development: The interplay of issue framing, top-of-mind associations, and political ideology. Energy Policy, 81, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.02.019

- Curran, J., Iyengar, S., Brink Lund, A., & Salovaara-Moring, I. (2009). Media system, public knowledge and democracy: A comparative study. European Journal of Communication (London), 24(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323108098943

- Deckard, S. (2019). Introduction: Reading Ireland’s food, energy, and climate. Irish University Review, 49(1), 1–12. Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.3366/iur.2019.0375

- Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment (DCCAE. (2019). National Adaptation Framework [online]. Retrieved August 15, 2019 from https://www.dccae.gov.ie/en-ie/climateaction/publications/Pages/National- Adaptation-Framework0118-4235.aspx

- Dessai, S., & Sims, C. (2010). Public perception of drought and climate change in southeast England. Environmental Hazards, 9(4), 340–357. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2010.0037

- Dessai, S., & Sims, C. (2011). Public perception of drought and climate change in southeast England. Environmental Hazards, 9(4), 340–357. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2010.0037

- Devitt, C., Brereton, F., Mooney, S., Conway, D., & O’Neill, E. (2019). Nuclear frames in the Irish media: Implications for conversations on nuclear power generation in the age of climate change. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 110, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2018.09.024

- Devitt, C., & O’Neill, E. (2016). The framing of two major flood episodes in the Irish print news media: Implications for societal adaptation to living with flood risk. Public Understanding of Science, 26(7), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516636041

- Dixon, G. N., & Clarke, C. E. (2013). Heightening uncertainty around certain science: Media coverage, false balance, and the autism-vaccine controversy. Science Communication, 35(3), 358–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012458290

- Dixon, G. N., McKeever, B. W., Holton, A. E., Clarke, C., & Eosco, G. (2015). The power of a picture: Overcoming scientific misinformation by communicating weight-of-evidence information with visual exemplars. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12159

- Dow, K. (2010). News coverage of drought impacts and vulnerability in the US Carolinas, 1998–2007. Natural Hazards, 54(2), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9482-0

- Dziegielewski, B. (1991, October 21–25) The drought is real: Designing a successful water conservation campaign. International Conference and Exhibition on Efficient Water Use. IWRA, NWCMexico, MIWT, Mexico City.

- Eisensee, T., & Strömberg, D. (2007). News droughts, news floods, and U. S. disaster relief. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 693–728. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.2.693

- Elo, S., & Kyngas, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. JAN, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Ireland. (2019a). EPA Research Programme 2014 - 2020 Reports: Environmental Protection Agency, Ireland [online]. Retrieved July 2, 2019 from http://www.epa.ie/researchandeducation/research/researchpublications/researchreports/research267.html

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Ireland. (2019b). EPA Research Programme 2014 - 2020 Reports: Climate Change in Irish Media. Retrieved January 10, 2022 from https://www.epa.ie/publications/research/climate-change/Research_Report_300.pdf

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Ireland. (2020). Ireland’s Enviornment – An Integrated Assessment [online]. Retrieved June 17, 2021 from https://epawebapp.epa.ie/ebooks/soe2020/330/

- Ewart, J. (2020). Drought is a disaster in the city: Local news media’s role in communicating disasters in Australia. In J. Matthews & E. Thorsen (Eds.), Media, journalism and disaster communities. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33712-4_5

- Ford, J., & King, D. (2015). Coverage and framing of climate change adaptation in the media: A review of influential North American newspapers during 1993–2013. Environmental Science & Policy, 48, 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.12.003

- Fraile, M., & Iyengar, S. (2014). Not all news sources are equally informative: A cross-national analysis of political knowledge in Europe. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(3), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214528993

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Contemporary Sociology, 4(6), 603. https://doi.org/10.2307/2067803

- Government of Ireland. (2020). Agriculture, forest and seafood climate change sectoral adaptation plan prepared under the National Adaptation Framework [online]. Retrieved June 17, 2021 from https://wayback.archive-it.org/org-1444/20201127125424/

- Harries, T., & Penning-Rowsell, E. (2011). Victim pressure, institutional inertia and climate change adaptation: The case of flood risk. Global Environmental Change, 21(1), 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.002

- Hart, P. (2010). One or many? The influence of episodic and thematic climate change frames on policy preferences and individual Behavior change. Science Communication, 33(1), 28–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547010366400

- Holden, N., & Brereton, A. (2002). An assessment of the potential impact of climate change on grass yield in Ireland over the next 100 years. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research, 41(2), 213–226. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25562465.

- Hurlimann, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2012). Newspaper coverage of water issues in Australia. Water Research, 46(19), 6497–6507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2012.09.028

- Igartua, J., Moral-Toranzo, F., & Fernández, I. (2011). Cognitive, attitudinal, and emotional effects of news frame and group cues, on processing news about immigration. Journal of Media Psychology, 23(4), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000050

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Working Group II. (2007). Summary for policy makers. IPCC, Geneva.

- Irish Water. (2018). Water Shortages & Restrictions. [online]. Retrieved August 12, 2019 from https://www.water.ie/water-supply/water-shortages/

- Irish Water. (2019a). National Water Resources Plan. [online]. Retrieved June 10, 2019 from https://www.water.ie/projects-plans/our-plans/nwrp/

- Irish Water. (2019b). Water Conservation Order (hosepipe ban) now in place nationwide as drought continues [online]. Retrieved July 3, 2019 from https://www.water.ie/news/national-water-conservati/

- Kapuściński, G., & Richards, B. (2016). News framing effects on destination risk perception. Tourism Management, 57, 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.017

- Kasperson, R., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H., Emel, J., Goble, R., Kasperson, J., & Ratick, S. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1988.tb01168.x

- Kelleher, L., Henchion, M., & O’Neill, E. (2019). Policy coherence and the transition to a bioeconomy: The case of Ireland. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 11(24), 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247247

- Kim, S., Shao, W., & Kam, J. (2019). Spatiotemporal patterns of US drought awareness. Palgrave Communication, 5(107), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0317-7

- Koehler, D. J. (2016). Can journalistic “false balance” distort public perception of consensus in expert opinion? Journal of Experimental Psychology, 22(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000073

- Kondracki, N., Wellman, N., & Amundson, D. (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34(4), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60097-3

- Lackstrom, K., Ward, R., & Davis, C. (2020). So why does the drought map look like that? Unpacking the linkages between the transparency of drought monitoring processes and usability of drought communication products. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. Vol. 2020.

- Marron, A. (2019). “Overpaid” and “inefficient”: Print media framings of the public sector in The Irish Times and The Irish Independent during the financial crisis. Critical Discourse Studies, 16(3), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2019.1570288

- Medd, W., & Chappells, H. (2007). Drought, demand and the scale of resilience: Challenges for interdisciplinarity in practice. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 32(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1179/030801807X211748

- Met Eireann. (2019). 2018, A summer of heat waves and droughts. https://www.met.ie/cms/assets/uploads/2018/09/summerfinal3.pdf

- Noone, S., & Murphy, C. (2020). Reconstruction of hydrological drought in Irish catchments (1850–2015). Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, 120C(1), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.3318/priac.2020.120.11

- Noone, S., Murphy, C., Coll, J., Matthews, J. T., Mullan, D., Wilby, R. L., & Walsh, S. (2015). Homogenization and analysis of an expanded long-term monthly rainfall network for the Island of Ireland (1850–2010). International Journal of Climatology, 36(8), 2837–2853. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4522

- O’Donnell, C., & Rice, R. E. (2008). Coverage of environmental events in US and UK newspapers: Frequency, hazard, specificity, and placement. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 65(5), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207230802233548

- O’Neill, E., Devitt, C., Lennon, M., Duvall, P., Astori, L., Ford, R., & Hughes, C. (2018). The dynamics of justification in policy reform: Insights from Water Policy Debates in Ireland. Environmental Communication, 12(4), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1429478

- Peltomaa, J., & Kolehmainen, J. (2017). Ten years of bioeconomy in the Finnish media. Alue ja Ympäristö, 46(2), 57–63. Retrieved from https://aluejaymparisto.journal.fi/article/view/68856

- Pollard, J. (2019). A Drop in the Bucket: Evaluating modern print news coverage of drought in the U.S. Bachelor of Arts. University Honors College.

- Quesnel, K., & Ajami, N. (2017). Changes in water consumption linked to heavy news media coverage of extreme climatic events. Science Advances, 3(10). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700784

- Regan, Á, Shan, L., McConnon, Á, Marcu, A., Raats, M., Wall, P., & Barnett, J. (2014). Strategies for dismissing dietary risks: Insights from user-generated comments online. Health, Risk, and Society, 16(4), 308–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2014.919993

- Robbins, D. (2018). Climate change, Politics and the press in Ireland. Routledge. ISBN: 9780429451157.

- Roudier, P., Andersson, J. C. M., Donnelly, C., Feyen, L., Greuell, W., & Ludwig, F. (2016). Projections of future floods and hydrological droughts in Europe under a +2C global warming. Climate Change, 135(2), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1570-4

- Soroka, S., Lawlor, A., Farnsworth, S., & Young, L. (2013). Mass media and policy-making. In Araral, E, Fritzen, S, Howlett, M (eds), Routledge Handbook of Public Policy. London: Routledge, pp. 204–215.

- Ward, R., Lackstron, K., & Davis, C. (2021). Demystifying drought: Strategies to enhance the communication of a comples hazard. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 1–43.

- Wei, J., Wei, Y., Western, A., Skinner, D., & Lyle, C. (2015). Evolution of newspaper coverage of water issues in Australia during 1843–2011. AMBIO, 44(4), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0571-2

- Whitmarsh, L. (2011). Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 690–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.016

- Wilhite, D. A., & Glantz, M. H. (1985). Understanding: The drought phenomenon: The role of definitions. Water International, 10(3), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508068508686328

- Wilhite, D. A., Mannava, V. K., & Sivakumar, R. P. (2014). Managing drought risk in a changing climate: The role of national drought policy. Weather and Climate Extremes, 3, 4–13. ISSN 2212-0947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2014.01.002