ABSTRACT

To combat climate change, it is of vital importance that people change their behaviors. This study explores how influencers, or so-called greenfluencers, on Instagram could be utilized to stimulate pro-environmental behavior. We examine the effects of influencer-message congruence on influencer credibility (i.e. trustworthiness and expertise) and pro-environmental intentions, and compare the effects of influencer-message congruence between micro- (1000–10,000 followers) and meso- (10,000–1 million followers) influencers. Results of a 2 (influencer-message: incongruence vs. congruence) × 2 (influencer type: micro- vs. meso-influencer) online experiment amongst 201 Instagram users revealed that influencer-message congruence increased influencer credibility and pro-environmental intentions. Influencer credibility did not appear to be the underlying mechanism of the effect of congruence on pro-environmental intentions. Moreover, influencer type did not moderate the effect of influencer-message congruence. Our results imply that choosing an influencer whose image aligns with the pro-environmental message is important to stimulate Instagram users’ pro-environmental behavior.

Introduction

The consequences of anthropogenic climate change are becoming more and more pressing. In recent years, catastrophic effects of climate change such as wildfires, floods, and extreme weather events became more apparent. To combat climate change, it is of vital importance that – next to politics and companies taking action – people change their individual behavior (United Nations, Citation2021). That is, the rising temperatures can be significantly reduced if individuals would engage in more environmentally friendly behavior (Clayton et al., Citation2015; Vlek & Steg, Citation2007). So far, it has however been proven challenging to stimulate pro-environmental behaviors (Kumar et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is important to investigate how new, inventive strategies could be put to use to encourage pro-environmental behavior.

Social media are an important place for young adults’ conversations and meaning-making about environmental and sustainability issues (Andersson & Öhman, Citation2017; Joosse & Brydges, Citation2018). Therefore, one potential strategy could be the use of social media influencers, opinion leaders who communicate with a sizeable social network of people following them (De Veirman et al., Citation2017) and who can reach large audiences via social media. When influencers promote environmental awareness and an environmentally friendly lifestyle, they are also called greenfluencers (Pittman & Abell, Citation2021) or eco-influencers (Bentley et al., Citation2021).

Whereas research has already documented the effectiveness of social media influencers in affecting social media users’ concerns, attitudes, and behaviors (see a literature review by Hudders et al., Citation2021), the effectiveness of greenfluencers is less well documented (Johnstone & Lindh, Citation2018; Pittman & Abell, Citation2021). Previous research does find initial evidence for the mobilizing power of greenfluencers, showing that following influencers who raise awareness about cause-related topics such as the environment is associated with higher pro-environmental behavior intentions over time (Dekoninck & Schmuck, Citation2022). In addition, research revealed that greenfluencers have followers all over the world, and that followers are more likely to engage with the greenfluencers they follow if they live in countries where environmental concerns are more important (Bentley et al., Citation2021). However, the conditions under which greenfluencers’ messages are effective is understudied. Therefore, this research investigates what type of influencers can serve best as climate change spokespersons and spark pro-environmental behavior amongst their followers.

We propose that the congruence between the influencer’s image and the message is vital. Previous studies in commercial contexts highlight that the effectiveness of a persuasive message on content is inseparably tied to the degree to which the image, personality, or expertise of the influencer is congruent with the endorsed entity (e.g. brand or message; Breves et al., Citation2019; Schouten et al., Citation2020). Congruence seems particularly relevant in the context of greenfluencing, as celebrities and influencers who are campaigning for pro-environmental behavior are often accused of hypocrisy due to the incongruence between their environmental communication and their actual behavior (e.g. Warren, Citation2020). Examples include Al Gore who was promoting the movie An Inconvenient Truth, but at the same time was using about 21 times as much energy as an average U.S. citizen (Pilkington, Citation2007; please note U.S. citizens already belong to the top carbon emitters worldwide), and Prince Harry and Meghan Markle who stated not wanting to have more than two kids for environmental reasons but took over 20 private jets in two years (Royston, Citation2021). Additionally, influencer Daisy Lowe, a self-proclaimed “eco-warrior,” was criticized for taking private jets and advertising for car brands (New Zealand Herald, Citation2019). Moreover, influencer marketing relies on brand deals but consumption and sustainability ultimately do not go hand in hand, as to stay within our planetary boundaries degrowth (in industrialized, Western countries) is key (Keyßer & Lenzen, Citation2021). Research also acknowledged the possibility of influencers having a greenwashing effect, making brands look more sustainable than they actually are (Sailer et al., Citation2022). We, therefore, test the principle of congruity within the context of greenfluencers and investigate whether influencer’s ability to change people’s intention to engage in pro-environmental behaviors depends on their image (i.e. are they profiling themselves as green or not?).

Furthermore, we investigate the consequences of influencer-message congruence for the influencer’s credibility, a vital determinant in influencer marketing (e.g. Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Wellman et al., Citation2020). Influencers are deemed influential because they are authentic, relatable, and credible endorsers (e.g. Djafarova & Rushworth, Citation2017; Hudders et al., Citation2021; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). Since prior research has shown that influencer and endorser credibility can positively affect behavioral intentions (e.g. Breves et al., Citation2019; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Reinikainen et al., Citation2020; Schouten et al., Citation2020; Weismueller et al., Citation2020) and pro-environmental behavior (Attari et al., Citation2016), we aim to gain an understanding of how incongruence (vs. congruence) may damage influencer credibility, and the underlying role that influencer credibility may play in the effects of congruence in promoting pro-environmental behavior amongst Instagram users.

Lastly, we compare the effects of influencers varying in number of followers (i.e. micro- or meso-influencer). The number of followers has been shown to increase influencers’ perceived credibility (Weismueller et al., Citation2020) and opinion leadership (De Veirman et al., Citation2017). However, there is also research suggesting that a smaller follower base might be more persuasive when it comes to green advertising (Pittman & Abell, Citation2021). Since there is limited research on whether one influencer can outperform another (Kay et al., Citation2020) and so far most studies focus on a marketing context, we investigate whether the influencer’s reach (focusing on micro-influencers (1000–10,000) and meso-influencers (10,000–1 million followers)) moderates the effect of influencer-message congruence on the perceived credibility of the influencer and pro-environmental intentions.

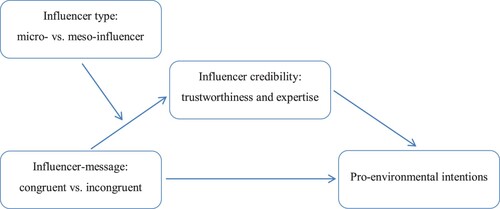

In sum, our aim is to combine and progress existing research streams of climate change communication and influencer marketing to provide actionable insights for stimulating pro-environmental behavior. Correspondingly, we examine if influencer-message congruence can be used to increase pro-environmental intentions, and whether influencer credibility (i.e. trustworthiness and expertise) is the underlying mechanism. Furthermore, we study whether effects differ between micro- and meso-influencers.

Effect of influencer-message congruence

Classic communication science theories like the Communication-Persuasion Matrix of McGuire (Citation2001) stress the importance of, amongst others, the message source in driving the persuasive effectiveness of a message. Research has identified celebrity endorsement as an effective tool for enhancing persuasiveness of the message and positively affecting attitudes and behavioral intentions (e.g. Amos et al., Citation2008; Bergkvist & Zhou, Citation2016). Influencers have proven to be even more effective endorsers, as they are more credible, authentic, relatable, and trustworthy than traditional endorsers, maximizing message persuasion in influencing brand preferences and inciting behavioral change (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020; Djafarova & Rushworth, Citation2017; Schouten et al., Citation2020). Although influencer research is mostly done in the context of marketing (Hudders et al., Citation2021), there is also some research on behavior change in the non-profit context, of which even a few in the context of greenfluencers (Johnstone & Lindh, Citation2018; Pittman & Abell, Citation2021). Based on these studies, we expect that a pro-environmental message by an influencer could effectively promote pro-environmental intentions among Instagram users. The question remains, however, what type of influencers are specifically effective in stimulating environmental behavioral change amongst their followers? Previous research suggests that the congruence between the influencer’s image and the message may be an important factor in determining the effectiveness of the green message.

In general, congruence refers to the degree of similarity between two objects or activities (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). The principle of congruity contends that congruent information is more recalled, preferred, and accepted than incongruent information (Osgood & Tannenbaum, Citation1955). In the context of influencer endorsements, congruence regards the fit or match between the image, behavior, and expertise of the influencer and the endorsed entity, such as the message or brand (Breves et al., Citation2019; Kamins & Gupta, Citation1994; Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Till & Busler, Citation2000). Congruence seems to be vital in influencer endorsements: several studies have shown that congruence between relevant attributes of the influencer and the endorsed entity positively influences content, brand, and product evaluations (e.g. Breves et al., Citation2019; Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Shan et al. Citation2020; Woodcock & Johnson, Citation2019).

The positive effect of congruence can be explained by the Match-Up Hypothesis (Breves et al., Citation2019; Kamins & Gupta, Citation1994; Kim & Kim, Citation2021). More specifically, the Match-Up Hypothesis proposes that a fit between the influencers’ attributes and message facilitates an associative link. This link strengthens the existing knowledge structures which then increases the transfer of attributes from the influencers to the message (Lynch & Schuler, Citation1994). Thus, when fit occurs, the relationships based on shared associations within knowledge structures can be processed fluently (Till & Busler, Citation2000). This fit can result in favorable evaluations of the endorsed entity, in this case the message promoting pro-environmental behavior. However, when incongruence is experienced, processing is less likely to take place within existing knowledge structures. Individuals who are unable to resolve this misfit may experience a mental struggle that can elicit negative feelings of frustration and helplessness. This hindrance to make connections for transferring associations, can result in unfavorable evaluations of the endorsed entity (Meyers-Levy et al., Citation1994).

Most studies on influencer-message congruence tend to focus on commercial outcomes (e.g. Breves et al., Citation2019; Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Schouten et al., Citation2020). However, one recent study by Sparkman and Attari (Citation2020) in the field of endorsers (i.e. expert, neighbor) showed that congruence between displayed behavior and the endorser is crucial for persuasion in climate change communication. Although this study focused on other types of endorsers, it does suggest that when an influencer promotes pro-environmental behavior, alignment between the post and their image is key (Sparkman & Attari, Citation2020). Thus, based on prior research and the Match-up Hypothesis, we expect that congruence between an influencers’ image and behavior on Instagram and the pro-environmental message will increase the persuasiveness of the message, leading to stronger pro-environmental intentions:

H1: Influencer-message congruence (vs. incongruence) will increase pro-environmental intentions among Instagram users.

Mediating role of influencer credibility

Credibility is key for influencers: it leads to a favorable view of the influencer and positively affects consumers’ beliefs, opinions, attitudes, and behaviors (e.g. Breves et al., Citation2019; Lee & Koo, Citation2015; Stubb & Colliander, Citation2019). Whereas some studies focus on the concept of credibility holistically, others look at specific components of endorser credibility, namely: trustworthiness, expertise, and attractiveness (Breves et al., Citation2019; Ohanian, Citation1990; Schouten et al., Citation2020). Trustworthiness refers to the perceived honesty, sincerity, and truthfulness of the influencer, and thus whether the influencer is perceived as someone who provides objective and honest information (Erdogan, Citation1999; Ohanian, Citation1990). Expertise refers to the perceived competence of the influencer to make claims, like deriving from influencers’ knowledge, experience, or skills (Erdogan, Citation1999; Ohanian, Citation1990). Lastly, attractiveness refers to the perceived physical or social attractiveness of the influencer (Ohanian, Citation1990).

Research has shown that influencer-message congruence increases the credibility of the influencer. Kamins and Gupta (Citation1994) showed that congruence between an endorser and the message positively affects the endorser’s credibility. In line with this, research into influencer credibility demonstrated that congruence (vs. incongruence) in influencer endorsements elicits higher levels of perceived influencer trustworthiness and expertise (Breves et al., Citation2019; Schouten et al., Citation2020). The effects of congruence on attractiveness are less clear with studies showing a positive effect (Torres et al., Citation2019) and others showing no effect (Breves et al., Citation2019; Schouten et al., Citation2020). As physical attractiveness is not always relevant in influencer marketing, recent research in influencer marketing regularly omits the attractiveness component when studying credibility and focuses on trustworthiness and expertise (Breves et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2021; Schouten et al., Citation2020).

Additionally, in climate change communication, research has shown that when endorsers’ messages are congruent with their behavior, this enhances the credibility of the source (Sparkman & Attari, Citation2020) whereas incongruence can lead to perceptions of hypocrisy or distrust (Stone & Fernandez, Citation2008), which also reduces the credibility of the source (Sparkman and Attari Citation2020). Thus, influencers that endorse entities that are incongruent with their image are deemed less credible (Dwivedi & Johnson, Citation2013; Lee & Koo, Citation2015), because they may infer insincere motives or commercial intentions (Koernig & Boyd, Citation2009).

Like the effectiveness of an influencer message, the positive effect of influencer-message congruence on credibility can be attributed to the Match-Up Hypothesis: A congruent message is more likely to be accepted and thus to be perceived credible, than an incongruent message. Additionally, this effect can be explained by the Attribution Theory and the related Multiple Inference Model (MIM). Attribution theory assumes that individuals are social perceivers who make causal inferences about events they observe and experience (Rifon et al., Citation2004). Building on this theory, the MIM proposes that individuals consider a variety of inferences (such as motives, characteristics of the situation, and prior knowledge) for why someone does something, and try to integrate these inferences into one coherent impression (Reeder et al., Citation2004; Verlegh et al., Citation2013).

Previous work has applied Attribution Theory and the MIM to celebrity and influencer endorsements to explain that consumers will try to cognitively infer endorsers’ motives for a message or behavior (e.g. Kamins, Citation1990; Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Reeder et al., Citation2004; Rifon et al., Citation2004). Based on these theories, congruence is important because people will try to infer the motives for a single message (such as a post promoting pro-environmental behavior) using their knowledge about the endorser, their previous behavior or messages, and the intentions they may have with it. For instance, people will try to infer whether an influencer posts a message promoting sustainable behavior because they genuinely feel this is important, or to create a (dishonest) green image, or because of a paid collaboration. When the endorsed message is relevant and expected from the influencer, users may infer that the influencer is internally motivated, and that their intentions are genuine (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). To illustrate, research has shown that when there is a match between a fitness product and a health influencer, the influencer is perceived to be internally motivated to promote the product (i.e. based on own preference) rather than externally motivated (e.g. financial purposes; Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Koernig & Boyd, Citation2009). Following this reasoning, whenever there are inconsistencies between the message and the inferred motives for this message, this may damage the influencer’s credibility.

Thus, based on the Match-Up Hypothesis, Attribution Theory and MIM, we expect that perceived congruence between an influencer’s image on Instagram and the pro-environmental Instagram message increases influencers’ credibility (measured as trustworthiness and expertise).

H2. Influencer-message congruence (vs. incongruence) will increase Instagram users’ perception of the influencer’s (a) trustworthiness and (b) expertise.

As influencer credibility influences the persuasive outcomes of a message, we expect a mediation effect in which a congruent (vs. incongruent) message enhances influencer credibility, which subsequently increases pro-environmental intentions. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3. Influencer-message congruence (vs. incongruence) increases influencer (a) trustworthiness and (b)expertise, which in turn increase pro-environmental intentions among Instagram users.

Moderating role of influencer type

Influencers are often categorized based on their reach, which refers to the number of followers (De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Hudders et al., Citation2021). Influencer typologies usually distinguish micro-, meso-, and macro-influencers (Boerman, Citation2020; Boerman & Müller, Citation2022; Domingues Aguiar & Van Reijmersdal, Citation2018; Pedroni, Citation2016). Micro-influencers refer to the category of “normal” individuals, who turned Instafamous, and have between the 1000 and 10,000 followers, generally ascribed to a specific niche, for example food bloggers or fitness gurus. Meso-influencers have 10,000 to a million followers and are characterized as full-time professional influencers with a national reach. Macro-influencers have more than a million followers and are often established, international celebrities. In this study, we focus on micro- and meso-influencers as they make up the largest share of all influencers on Instagram (Ahmed, Citation2021; Santora, Citation2021). We expect that the different perceptions that Instagram users have of micro- and meso-influencers affect the perceived influencer credibility.

Influencers with a high number of followers are perceived as more credible, more popular, and are ascribed more opinion leadership, indicating that one is considered as expert or reference agent (De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Jin & Phua, Citation2014). Additionally, public figures such as meso-influencers have a “verified” Instagram account, showing that Instagram confirms the account. However, micro-influencers do not inherently have these characteristics. They are generally attributed to a specific niche and score high on authenticity and intimacy (Jin et al., Citation2019). When they endorse entities that do not fit their specific area of interest, the likelihood of damaging their authenticity and intimacy increases (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020; Carter, Citation2016). This suggests that deviating from their expertise may negatively impact their created intimate and authentic image (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020).

We, therefore, expect that an incongruent message may damage the credibility of a micro-influencer more, than it would for a meso-influencer, which may consequently diminish its persuasive effect on pro-environmental intentions. The attributed characteristics of the number of followers and verification of meso-influencers act as cues that increase their trustworthiness and expertise, which may compensate an incongruent message. Thus, we expect the mediated effect of congruence on pro-environmental intentions via credibility to be less strong for meso-influencer compared to micro-influencers (conceptual model depicted in ):

H4. The effects of influencer-message congruence on pro-environmental intentions via influencer (a)trustworthiness and (b)expertise are weaker when the post is sent by a meso-influencer. (vs. micro-influencer)

Method

Design and participants

We conducted an online experiment with a 2 (influencer-message incongruence vs. congruence) × 2 (micro-influencer vs. meso-influencer) between-subjects design between 30th November and 10th December, 2020. We recruited 231 participants among students at the University of Amsterdam who received research credits for their participation. We excluded participants who did not complete the questionnaire (n = 8), were younger than 18 years old (n = 1), who did not own an Instagram account (n = 1), or who failed our attention check (n = 28). This resulted in a final sample of 201 Instagram users.

The mean age was 20.53 (ranging from 18 to 26, SD = 1.83), and 85.6% of the participants were female. The majority were undergraduates with a high school diploma or equivalent (83.1%). Most participants used Instagram multiple times a day (75.1%) or daily (15.9%), and most Instagram users (80.6%) followed one or more social media influencers. As research has shown that the average Instagram user is between 18 and –34 years old, and women are more active on this platform than men, this sample closely resembles the core users of Instagram (Chen, Citation2018; Statista, Citation2021).

Procedure

The study was introduced on the university website as a study into how people respond to different Instagram posts and accounts. After accepting the informed consent, participants filled in a screening question about owning an Instagram account. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions (congruent and micro-influencer n = 46, incongruent and micro-influencer n = 52, congruent and meso-influencer n = 50, incongruent and meso-influencer n = 53).

We first presented all participants with the fictional Instagram account of Carly Brown (to manipulate congruence and influencer type), and then exposed them to the screenshot of a post promoting pro-environmental behavior, which was identical for everyone (see Appendix). Participants were instructed to carefully observe all the elements of the Instagram post and could continue after ten seconds.

The questionnaire started with a measure of pro-environmental intentions, followed by perceived influencer credibility, an attention check question, manipulation checks, and control questions about participants’ attitude towards environmentally friendly living, environmental identity, Instagram usage, and demographic information. Lastly, participants were debriefed about the goal of the study, thanked for their participation, and were given the opportunity to leave any remarks or suggestions.

Stimulus materials

We ran a pretest amongst 18 Instagram users to test several manipulations of influencer-message congruence. First, to test whether the created accounts differed in terms of perceived pro-environmental image, we asked participants to read a text introducing the account and showed them an account overview. We then asked participants to rate the environmentally friendliness of the influencer answering the statement: “I perceive this Instagrammer to be ‘green’ – that is, focused on the environment and sustainability” (1 = not green, 7 = green; adapted from Meijers et al., Citation2019a). Paired samples t-test showed that the pro-environmental account was perceived significantly more green (M = 4.83, SD = 1.47) than the environmentally unfriendly account (M = 2.00, SD = 1.28), t(17) = 6.59, p < .001, d = 1.55, 95% CI [0.85, 2.24].

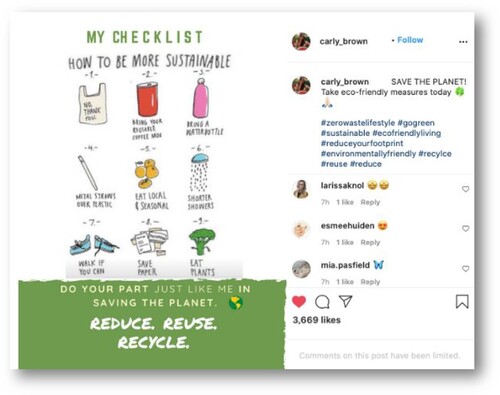

Second, to find an appropriate pro-environmental message, we presented five different posts and measured attitude toward the post (Spears & Singh, Citation2004), perceived environmental friendliness (“This Instagram post promotes environmentally friendly behavior” and “I perceive this Instagram post to be ‘green’ – i.e., focused on the environment and sustainability,” adapted from Meijers et al., Citation2019a), and asked which post participants believed was most suitable as a pro-environmental message.

We decided to continue with the post that was rated as most suitable by most participants (44%), received favorable attitudes (M = 4.69, SD = 1.55), and scored highest on perceived environmental friendliness (M = 5.92, SD = 0.65). This picture showed a textual list of eco-friendly measures. Because some participants said this particular picture was a bit boring, we added images of the listed behaviors.

The final stimulus materials consisted of an introductory text, an overview of the Instagram account @carlybrown (showing highlights, a grid of six pictures and a biography), followed by a post by the influencer (see Figures A1–A3 in the appendix). The Instagram post showed a graphic checklist of “How to be more sustainable” including using reusable plastic bags, eating vegetarian, and walking if possible. The caption said: “SAVE THE PLANET! Take eco-friendly measures today” accompanied by several hashtags.

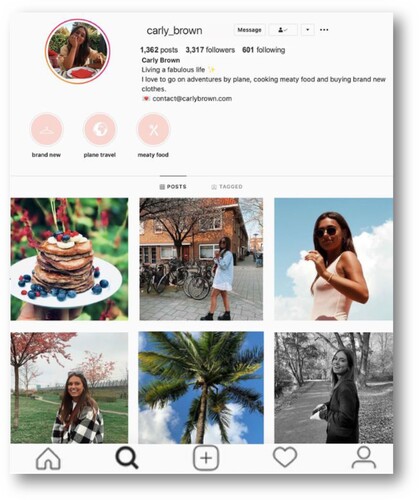

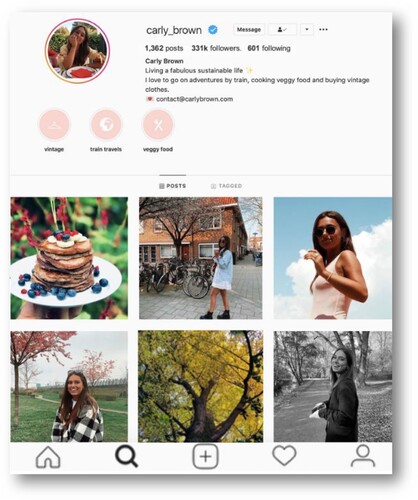

We manipulated congruence by changing visual cues in the account overview and the introduction to the account (i.e. bio, highlights, and one of the six pictures in the grid), given the importance of visual congruence in influencer marketing (Argyris et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, we used textual cues to manipulate congruence. In the congruent condition, the bio stated “Living a fabulous sustainable life. I love to go on adventures by train, cooking veggy food and buying vintage clothes”; the highlights were titled “vintage clothes,” “train travels” and “veggy food”; and the picture grid included a picture of a deciduous tree in the fall reflecting (local) nature. In the incongruence condition, the bio stated “Living a fabulous life. I love to go on adventures by plane, cooking meaty food and buying brand news clothes”; highlights showed “brand new,” “plane travel” and “meaty food”; and the grid included a picture of a palm tree, suggesting exotic, far away travel.

Furthermore, the introduction stated “You will now see an Instagram account, and afterwards an Instagram post, both from Carly Brown” followed by either “Carly mainly posts about shopping for vintage clothes, making vegetarian recipes and loves taking trips by train to new destinations. She cares about the environment and loves nature” (congruent) or “Carly mainly posts about shopping for brand new clothes, making recipes with meat and loves taking trips by plane to new destinations. She loves shopping and travelling” (incongruent).

The distinction between the influencer types was manipulated by the number of followers (micro: 3317 followers vs. meso: 331,000 followers) and type of account (i.e. micro: not verified vs. meso: verified; based on Boerman, Citation2020). These differences were visible in the account overview, and emphasized in the introduction, which said either “Carly Brown is an (environmentally friendly) Instagrammer with 3317 followers. She does not have a verified account. Only famous people get a verified account.” (micro-influencer) or “Carly Brown is a famous (environmentally friendly) Instagrammer with 331,000 followers. She also has a verified account, recognizable by the blue check behind her name, so people know that she is not a fake account. Only famous people get this” (meso-influencer).

Measures

Pro-environmental intentions

We measured the dependent variable by asking participants to indicate on a seven-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) to what extent they agreed with 10 statements (adapted from Ratliff et al., Citation2017), such as “I intend to reduce my meat intake” and “I intend to recycle items rather than throwing them in the trash.” The mean score on the ten items was used as a measure of pro-environmental intentions (Eigenvalue = 4.26, explained variance = 42.62%, α = 0.84; M = 4.96, SD = 1.03).

Influencer trustworthiness and expertise

We applied the semantic differential source credibility scale (Ohanian, Citation1990) to measure the influencer’s perceived credibility. The scale represented the three credibility dimensions, here we focus on two (i.e. trustworthiness, expertise)Footnote1 with five items for each dimension. Participants were asked to indicate how they perceived the influencer by completing the statement “In my opinion the Instagrammer Carly Brown is … ”. The average scores of five items created the subscales representing Trustworthiness (e.g. unreliable – reliable, insincere – sincere; α = 0.93; M = 4.09, SD = 1.32), and Expertise (e.g. inexperienced – experienced, unqualified – qualified; α = 0.90; M = 3.63, SD = 1.27).

Attention check

Following recommendations by Kees et al. (Citation2017) we included an attention check in which we told participants:

Research has found that people give little attention to reading the questions. We would therefore like to check if you are reading this. If you are reading this, please choose the option ‘none of the above-mentioned options’. What is this research about?

Manipulation checks

To ensure the validity of the manipulation of influencer-message congruence, we assessed how the participants perceived the congruence between the influencer and message by asking: “I think that the Instagram account of Carly Brown and the post is … ”, anchored on a seven-point semantic differential scale (adapted from Spry et al., Citation2011). This scale included three items: inappropriate – appropriate, a bad fit – a good fit, and not logical – logical (Eigenvalue = 2.64, explained variance = 87.8%, α = 0.93; M = 4.20, SD = 1.83).

Additionally, to check the manipulation of influencer type, we asked participants which type of Instagram account they thought they had seen (0 = a famous person, 1 = less famous) and to indicated the number of followers they thought the Instagrammer had (1 = 0–1000, 2 = 1000–3000, 3 = 3000–6000, 4 = 6000–9000, 5 = 100,000–200,000, 6 = 200,000–300,000, 7 = 300,000–400,000).

Control variables

To be able to check whether the randomization was successful, we included several control variables selected based on previous research in environmental communication, environmental psychology, and (influencer) marketing. That is, previous research in both environmental communication and psychology shows that pro-environmental intentions and behavior are affected by environmental identity (e.g. Meijers et al., Citation2019a; Van der Werff et al., Citation2013) and pro-environmental attitude (e.g. Bamberg & Möser, Citation2007; Knussen et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, both concepts have also been shown to moderate the impact of communication on behavior (e.g. Meijers et al., Citation2019a; Moore & Yang, Citation2020), making them important variables to control for. Similarly, influencer marketing research shows that Instagram usage and whether people follow influencers are important variables to take into account as these might affect persuasion (e.g. Boerman & Müller, Citation2022; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). For the key demographics (gender, age, and educational level), we followed common practice in communication research to check whether these are randomly distributed across conditions (e.g. Boerman & Müller, Citation2022; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Meijers et al., Citation2019a; Moore & Yang, Citation2020).

We measured participants’ environmental self-identity with five items (e.g. “I am concerned with environmental issues” and “I value being an environmentally friendly person”; 1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree; Meijers et al., Citation2019a; α = 0.85; M = 5.21, SD = 1.03).

Attitude towards pro-environmental living was assessed by asking participants to indicate to what extent they agreed (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) with five statements about environmentally friendly living (e.g. “My feelings about environmentally friendly living are positive” and “I am interested in the idea of environmentally friendly living”; adapted from Knussen et al., Citation2004; Meijers et al., Citation2019b; α = 0.92; M = 5.85, SD = 0.91).

Furthermore, we asked participants how often they used Instagram (1 = Never, 2 = Yearly, 3 = Monthly, 4 = Weekly, 5 = Multiple times a week, 6 = Daily, 7 = Multiple times a day) and if they followed any social media influencers (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Lastly, participants’ age in years, highest completed education, and gender were measured. presents the correlation matrix of all continuous variables, (in the Appendix) presents the detailed information of all measured scales.

Table 1. Correlation matrix of all measured continuous variables.

Results

Manipulation check

An independent sample t-test showed a large, significant difference in the perceived congruence between the incongruence conditions (M = 3.26, SD = 1.73) and congruence conditions (M = 5.23, SD = 1.32), t(199) = −9.03, p < .001, d = −1.27, 95% CI [−1.58, −0.97]. Thus, our manipulation of congruence was successful.

Additionally, 93.9% of the participants in the micro-influencer condition remembered seeing a less well-known Instagrammer. In the meso-influencer conditions, 53.4% of the participants correctly remembered to have seen a famous Instagrammer. This difference was significant χ2 (1) = 53.10, p < .001. Furthermore, in the micro-influencer conditions, 81.6% of the participants correctly responded that the Instagram account had 6000–9000 followers, and in the meso-influencer conditions, 69.9% of the participants correctly responded that the account had between 300,000–400,000 followers. The difference between the conditions was significant, χ2 (6) = 148.27, p < .001. Based on these results, we conclude that the manipulation of the type of influencer was also successful: participants perceived the two accounts to differ in terms of type of account and number of followers.

Randomization check

The four experimental groups did not significantly differ with respect to environmental identity F(3, 197) = 0.60, p = 0.646, attitude towards pro-environmental living F(3, 197) = 0.12, p = .950, use of Instagram F(3, 197) = 1.16, p = .325, following influencers χ2 (3) = 5.79, p = 0.122, gender χ2 (3) = 4.63, p = .201, age F(3, 197) = 2.41, p = .069, and educational level χ2 (9) = 4.42, p = .881. This means that randomization between conditions was successful, and no control variables were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Main effect of congruence on intention and influencer credibility

We tested H1 and H2 with a MANOVA with influencer-message congruence and influencer type (micro vs, meso) as factors and pro-environmental intentions and influencer trustworthiness and expertise as dependent variables. The analyses revealed a significant main effect of congruence, Wilk's Λ (3, 197) = 0.73, p < .001. presents an overview of the means of the two congruence conditions. Separate test of between-subjects analyses revealed that pro-environmental intentions were significantly lower in the incongruence conditions (M = 4.79, SD = 1.09) than in the congruence conditions (M = 5.16, SD = 0.92), F(1, 197) = 6.75, p = .011, ηp2 = .03. H1 was thus supported: influencer-message congruence increased pro-environmental intentions.

Table 2. Means of pro-environmental intentions, influencer trustworthiness and expertise for the influencer-message congruence conditions.

Furthermore, influencer trustworthiness was significantly higher in congruent conditions (M = 4.78, SD = 0.97) compared to the incongruent conditions (M = 3.45, SD = 1.29), F(1, 197) = 87.41, p < .001, η2 = 0.25. Additionally, influencer expertise was significantly higher in the congruent (M = 4.21, SD = 1.04) compared to the incongruent conditions (M = 3.11, SD = 1.23), F(1, 197) = 60.56, p < .001, η2 = 0.19. H2 was thus supported: influencer-message congruence enhanced influencer (a) trustworthiness and (b) expertise.

Furthermore, the MANOVA revealed no main effects of influencer type (p’s > .360) nor any interaction effects (p’s > .274) on the three dependent variables.

Mediating role of influencer credibility

To test the moderated mediation model proposed in H3 and H4, we used Model 7 of PROCESS version 4.0 (Hayes, Citation2022) in IBM SPSS Statistics 28. We included congruence as independent variable, influencer type as moderator, trustworthiness and expertise as mediators in parallel, and pro-environmental intentions as dependent variable. All analyses used 10,000 bootstrap sample to estimate 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals.

Results showed that, when including credibility (i.e. trustworthiness and expertise) in the model, the direct effect of congruence on pro-environmental intentions was not significant (b = 0.27, se = 0.17, p = .109). Furthermore, trustworthiness (b = 0.04, se = 0.09, p = .630) and expertise (b = 0.04, se = 0.09, p = .650) did not directly affect pro-environmental intentions. In addition, we found no indirect effects of congruence on pro-environmental intentions via trustworthiness (indirect effect in micro-influence condition = 0.05, boot se = 0.11, CI [−0.16, 0.29]; indirect effect in meso-influence condition = 0.06, boot se = 0.14, CI [−0.21, 0.33]). The same applied to influencer expertise: there was no significant indirect effect via expertise (indirect effect in micro-influence condition = 0.03, boot se = 0.08, CI [−0.13, 0.20]; indirect effect in meso-influence condition = 0.05, boot se = 0.11, CI [−0.16, 0.28]). Thus, our results do not support H3: influencer credibility (i.e. trustworthiness and expertise) did not mediate the effect of influencer-message congruence on pro-environmental intentions.

Moderating effect of influencer type

Furthermore, the results showed no significant interaction effect of congruence and influencer type on trustworthiness (b = 0.25, se = 0.33, p = .776) and expertise (b = 0.35, se = 0.32, p = .274). Influencer type also did not have a significant main effect on trustworthiness (b = −0.28, se = 0.22, p = .222) and expertise (b = −0.19, se = 0.22, p = .390). The index of moderated mediation was also insignificant for trustworthiness (index of moderated mediation = 0.01, boot se = 0.04, CI [−0.07, 0.10]) and expertise (index of moderated mediation = 0.01, boot se = 0.04, [CI −0.06, 0.13]). Hence, we found no support for H4: Influencer type did not moderate the effects, and we found no differences between the micro- or meso-influencer.

Conclusion and discussion

With this study, we investigated how influencers – or greenfluencers – can affect pro-environmental intentions and which influencer attributes are critical to maximize effectiveness. The results revealed a positive direct effect of influencer-message congruence on both influencer credibility (i.e. influencer trustworthiness and expertise) and pro-environmental intentions. However, influencer credibility did not appear to be the underlying mechanism for the positive effect of congruency on pro-environmental intentions. In addition, the effects did not differ between micro- and meso-influencers. These results lead to three main insights.

First, our study shows that influencer-message congruence is important to positively affect Instagram users’ pro-environmental intentions. This finding is in line with the Match-Up Hypothesis, which implies that endorsers are more effective if they are congruent with the advertised entity (Kamins, Citation1990; Kamins & Gupta, Citation1994; Till & Busler, Citation2000). Furthermore, our results are consistent with previous research that found positive effects of influencer- and product/brand congruence on product or brand evaluations (e.g. Breves et al., Citation2019; Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Shan et al. Citation2020) and of endorser-message congruence on pro-environmental behavior (Sparkman & Attari, Citation2020). This is, however, the first study that confirms that the positive effect of congruence can also be applied to influencers in climate change communication. Hence, these findings contribute to existing literature by showing that influencer-message congruence is key in effectively promoting pro-environmental behavior.

Second, we found that influencer-message congruence positively affects influencer credibility (i.e. trustworthiness and expertise). These findings are in line with prior research that has shown positive effects of influencer congruence in commercial contexts on trustworthiness and expertise (Breves et al., Citation2019; Schouten et al. Citation2020), and in the climate change context for trustworthiness (Sparkman & Attari, Citation2020).

However, contrary to expectations, our study did not provide evidence for the mediating role of influencer credibility as the underlying mechanism of influencer-message congruence on pro-environmental intentions. Although previous research showed that influencer credibility effectively enhances purchase intentions (e.g. Breves et al., Citation2019; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Reinikainen et al., Citation2020; Schouten et al., Citation2020), we find no evidence for an effect of credibility on pro-environmental behavior intentions. Moreover, these findings contradict the premise in traditional endorsement literature (Amos et al., Citation2008) and influencer literature (e.g. Wellman et al., Citation2020) that credible sources are more powerful and effective in encouraging behavior. The absence of this effect can be explained due to the complex nature of the issue and process.

Taking into account that congruence positively affected influencer credibility, the probability exists that barriers of underlying skepticism or distrust of climate change communication were present among the Instagram users, for example, due to fear of greenwashing (Schmuck et al., Citation2018). In the same vein, in influencer literature skepticism and ambivalent beliefs about influencers motives are identified as negatively impacting commercial outcomes (Boerman et al., Citation2017; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). Instagram users are known to be familiar with advertising tactics such as endorsements, and when this persuasion knowledge is accessed and used, this can diminish the persuasive effects of sponsored endorsements (Boerman & Müller, Citation2022; Boerman et al., Citation2017; Evans et al., Citation2017). According to Lou and Yuan (Citation2019) even the perception of commercial intent can diminish the effects of trustworthiness cues in consumer responses. Therefore, future research should consider and measure if this persuasion knowledge is also triggered in this non-commercial climate change communication, and if this influences responses.

Third, our research explored the under-researched field of whether one influencer can outperform another, based on number of followers (Kay et al., Citation2020). Contrary to expectations, we found no differences between micro- and meso-influencer in performance on influencer credibility and pro-environmental intentions. Whereas this aligns with previous research that found no effects between number of followers (Boerman, Citation2020; Boerman & Müller, Citation2022), it contradicts prior studies that found positive effects of number of followers on ascribed opinion leadership and credibility (e.g. De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Jin & Phua, Citation2014; Weismueller et al., Citation2020). These findings challenge the assumption in practice and research that influencer type alters the persuasiveness of the message (e.g. Weismueller et al., Citation2020). This raises the question if influencers should be categorized in terms of reach, or that other categorizations could be more effective, like classifying on impact such as perceived opinion leadership or specific niche (Xiong et al., Citation2018). Future research could focus on gaining more insights into how and what Instagram users perceive as differences between influencers and how this alters their reactions.

Theoretical implications

This study suggests that influencers can be useful in promoting pro-environmental behavior amongst young adults, if the message is congruent to the influencer’s image. Although previous research has shown the importance of congruence between endorsers and their message, our findings support the Match-Up Hypothesis (Kamins, Citation1990; Kamins & Gupta, Citation1994; Till & Busler, Citation2000) in the context of endorsing pro-environmental behavior by social media influencers (i.e. greenfluencing). In addition, as congruence boosted the influencers’ credibility, our findings suggest the relevance of the Attribution Theory and MIM in the context of greenfluencer messages on Instagram. When the displayed behavior and image of a social media influencer seem in harmony with the nature of the promoted message, the influencer will be perceived as a credible source of information (Kamins, Citation1990; Mishra et al., Citation2015). Further research could investigate these mechanisms in more detail by studying the exact motives users infer from different greenfluencer messages.

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations that reveal both opportunities and challenges for future research. First, there was no significant effect of influencer credibility on pro-environmental intentions. Future research could investigate the role of other underlying mechanisms and conditions that could explain and mitigate the persuasive effects of a greenfluencer message, such as message credibility (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019), environmental identity (Meijers et al., Citation2019a), attitude towards environmental living (Knussen et al., Citation2004), climate change urgency (Frantz & Mayer, Citation2009), and hypocrisy (Stone & Fernandez, Citation2008). Such research would help to understand the actual transfer processes from the influencers to the message and identify possible barriers.

Second, this study did not address the para-social interaction or relationship between the influencer and the recipients, despite being an important factor in explaining people’s responses to influencer marketing (e.g. Hudders et al., Citation2021; Jin et al., Citation2019; Shan et al., Citation2020). The use of a fictional influencer improved internal validity but reduced the ability to generate para-social interactions in this study. In previous studies, para-social relationships provided a boost in accepting advice from influencers (Jin et al., Citation2019), made children more susceptible to influencer marketing (Boerman & Van Reijmersdal, Citation2020), and increased likelihood of engaging in promoted behavior (Shan et al., Citation2020). Future research could study whether para-social interactions influence the persuasiveness of greenfluencers.

In addition, as different social media platforms are used for different purposes and have distinct features (Voorveld et al. Citation2018), further research could examine whether our findings also apply to other popular social media, such as TikTok or YouTube. While doing so, it might also be interesting to not only focus on people’s responses to the influencer (i.e. the source of the message) and how these responses influence pro-environmental intentions, but also study the responses to the message that is being conveyed by the influencer (e.g. finding the message more or less credible or valuable). Additionally, future research could look more closely into the interplay between the two (i.e. message source and message), for example, whether people experience more fluency in processing the message once there is congruency between the source and the message.

Practical implications

This study has practical implications that can be of interest to several stakeholders. Our findings show that social media influencers can be credible and effective endorsers to promote pro-environmental behavior if their image fits the cause. Influencers are particularly interesting endorsers if campaigns want to reach young audiences that are hard to reach via traditional channels (Dekoninck & Schmuck, Citation2022; Domingues Aguiar & Van Reijmersdal, Citation2018). Our findings suggest that seeing influencers take action against climate change could potentially help recipients to form climate-friendly intentions. Thus, if the government, sustainable businesses, or other stakeholders want to convey a climate change behavioral message, an influencer can function as a valuable endorser. However, attention must be paid to finding the right influencer: someone who is already aligned with sustainability. Furthermore, these findings may also be a starting point for addressing other social behavioral issues on Instagram, in areas such as public health, as implied by Hudders and colleagues (Citation2021).

The type of influencer (micro- vs. meso-influencers) does not seem to influence the effectiveness of the pro-environmental message. Therefore, this finding aligns with practitioners and scientists that are expressing skepticism on selecting influencers only on their reach (Eyal, Citation2018; Ismail, Citation2018; Kay et al. Citation2020). Micro-influencers may not have the largest reach, but are relatively low-cost endorsers and are ascribed strong interaction and niche specificity. This makes it interesting for marketeers and governments to collaborate with these smaller influencers. Nonetheless when going beyond numbers, other approaches to selecting the right influencer could be based upon expertise or opinion leadership (Xiong et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, our study suggests that for influencers, promoting a cause that is incongruent with their own image, can damage their credibility. As influencers are deemed so influential and persuasive because of their credibility, this suggests that choosing matching endorsements and (non-)commercial relationships is also vital for influencers. After all, when employing greenfluencers to promote pro-environmental behaviors to Instagram users, congruence between the words and deeds of the influencer is key.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The full scale included a third subscale Attractiveness (e.g. unattractive – attractive, ugly – beautiful; α = 0.83; M = 5.09, SD = 0.94). We excluded this scale from analyses because we had no theoretical reasons to include it (i.e. physical attractiveness and sustainability are not related).

References

- Ahmed, A. (2021). Ever thought about how many influencers exist in the world, and across all the major social media platforms? This research shows some astonishing figures. https://www.digitalinformationworld.com/2021/04/ever-thought-about-how-many-influencers.html.

- Amos, C., Holmes, G., & Strutton, D. (2008). Exploring the relationship between celebrity endorser effects and advertising effectiveness. International Journal of Advertising, 27(2), 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2008.11073052

- Andersson, E., & Öhman, J. (2017). Young people’s conversations about environmental and sustainability issues in social media. Environmental Education Research, 23(4), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1149551

- Argyris, Y. A., Wang, Z., Kim, Y., & Yin, Z. (2020). The effects of visual congruence on increasing consumers’ brand engagement: An empirical investigation of influencer marketing on Instagram using deep-learning algorithms for automatic image classification. Computers in Human Behavior, 112, 106443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106443

- Attari, S. Z., Krantz, D. H., & Weber, E. U. (2016). Statements about climate researchers’ carbon footprints affect their credibility and the impact of their advice. Climatic Change, 138(1–2), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1713-2

- Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.12.002

- Bentley, K., Chu, C., Nistor, C., Pehlivan, E., & Yalcin, T. (2021). Social media engagement for global influencers. Journal of Global Marketing, 34(3), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2021.1895403

- Bergkvist, L., & Zhou, K. Q. (2016). Celebrity endorsements: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Advertising, 35(4), 642–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1137537

- Boerman, S. C. (2020). The effects of the standardized Instagram disclosure for micro- and meso-influencers. Computers in Human Behavior, 103, 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.015

- Boerman, S. C., & Müller, C. M. (2022). Understanding which cues people use to identify influencer marketing on Instagram: An eye tracking study and experiment. International Journal of Advertising, 41(1), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1986256

- Boerman, S. C., & Van Reijmersdal, E. A. (2020). Disclosing influencer marketing on YouTube to children: The moderating role of para-social relationship. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03042

- Boerman, S. C., Willemsen, L. M., & Van Der Aa, E. P. (2017). This post is sponsored: Effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of Facebook. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2016.12.002

- Breves, P. L., Liebers, N., Abt, M., & Kunze, A. (2019). The perceived fit between Instagram influencers and the endorsed brand. Journal of Advertising Research, 59(4), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2019-030

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003

- Carter, D. (2016). Hustle and brand: The sociotechnical shaping of influence. Social Media + Society, 2(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116666305

- Chapple, C., & Cownie, F. (2017). An investigation into viewers’ trust in and response towards disclosed paid-for-endorsements by YouTube lifestyle vloggers. Journal of Promotional Communications, 5, 110–136.

- Chen, H. (2018). College-aged young consumers’ perceptions of social media marketing: The story of Instagram. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 39(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2017.1372321

- Clayton, S., Devine-Wright, P., Stern, P. C., Whitmarsh, L., Carrico, A., Steg, L., Swim, J., & Bonnes, M. (2015). Psychological research and global climate change. Nature Climate Change, 5(7), 640–646. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2622

- De Jans, S., Van de Sompel, D., De Veirman, M., & Hudders, L. (2020). # Sponsored! How the recognition of sponsoring on Instagram posts affects adolescents’ brand evaluations through source evaluations. Computers in Human Behavior, 109, 106342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106342

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035

- Dekoninck, H., & Schmuck, D. (2022). The mobilizing power of influencers for pro-environmental behavior intentions and political participation. Environmental Communication, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2027801

- Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009

- Domingues Aguiar, T., & Van Reijmersdal, E. A. (2018). Influencer marketing. SWOCC 76.

- Dwivedi, A., & Johnson, L. W. (2013). Trust–commitment as a mediator of the celebrity endorser–brand equity relationship in a service context. Australasian Marketing Journal, 21(1), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2012.10.001

- Erdogan, B. Z. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870379

- Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2017.1366885

- Eyal, G. (2018). Even social networks are struggling with influencer marketing. Marketing Dive. https://www.marketingdive.com/news/even-social- networks-are-struggling-with-influencer-marketing/542051/.

- Frantz, C. M., & Mayer, F. S. (2009). The emergency of climate change: Why are we failing to take action? Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 9(1), 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01180.x

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2021). The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 327–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925

- Ismail, K. (2018). Marketers beware: Influencer marketing fraud is real. CMS wire. https://www.cmswire.com/digital-marketing/marketers-beware-influencer-marketing-fraud-is-real/.

- Jin, S. S. A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following celebrities’ tweets about brands: The impact of twitter-based electronic word-of-mouth on consumers’ source credibility perception, buying intention, and social identification with celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.827606

- Jin, S. V., Muqaddam, A., & Ryu, E. (2019). Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(5), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-09-2018-0375

- Johnstone, L., & Lindh, C. (2018). The sustainability-age dilemma: A theory of (un)planned behavior via influencers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 17(1), e127–e139. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1693

- Joosse, S., & Brydges, T. (2018). Blogging for sustainability: The intermediary role of personal green blogs in promoting sustainability. Environmental Communication, 12(5), 686–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1474783

- Kamins, M. A. (1990). An investigation into the “match-up” hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may be only skin deep. Journal of Advertising, 19(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673175

- Kamins, M. A., & Gupta, K. (1994). Congruence between spokesperson and product type: A matchup hypothesis perspective. Psychology and Marketing, 11(6), 569–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220110605

- Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., & Parkinson, J. (2020). When less is more: The impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(3–4), 248–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1718740

- Kees, J., Berry, C., Burton, S., & Sheehan, K. (2017). An analysis of data quality: Professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon's mechanical Turk. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269304

- Keyßer, L. T., & Lenzen, M. (2021). 1.5 c degrowth scenarios suggest the need for new mitigation pathways. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22884-9

- Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H.-Y. (2021). Influencer advertising on social media: The multiple inference model on influencer-product congruence and sponsorship disclosure. Journal of Business Research, 130, 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.020

- Knussen, C., Yule, F., MacKenzie, J., & Wells, M. (2004). An analysis of intentions to recycle household waste: The roles of past behaviour, perceived habit, and perceived lack of facilities. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2003.12.001

- Koernig, S. K., & Boyd, T. C. (2009). To catch a tiger or let him go: The match-up effect and athlete endorsers for sport and non-sport brands. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 18(1), 25–37.

- Kumar, B., Manrai, A. K., & Manrai, L. A. (2017). Purchasing behavior for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.09.004

- Lee, S. S., Vollmer, B. T., Yue, C. A., & Johnson, B. K. (2021). Impartial endorsements: Influencer and celebrity declarations of non-sponsorship and honesty. Computers in Human Behavior, 122, 106858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106858

- Lee, Y., & Koo, J. (2015). Athlete endorsement, attitudes, and purchase intention: The interaction effect between athlete endorser-product congruence and endorser credibility. Journal of Sport Management, 29(5), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0195

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Lynch, J., & Schuler, D. (1994). The matchup effect of spokesperson and product congruency: A schema theory interpretation. Psychology and Marketing, 11(5), 417–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220110502

- McGuire, W. J. (2001). Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communications, public communication campaigns (3rd ed). Sage.

- Meijers, M. H. C., Noordewier, M. K., Verlegh, P. W. J., Willems, W., & Smit, E. G. (2019a). Paradoxical side effects of green advertising: How purchasing green products may instigate licensing effects for consumers with a weak environmental identity. International Journal of Advertising, 38(8), 1202–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1607450

- Meijers, M. H. C., Remmelswaal, P., & Wonneberger, A. (2019b). Using visual impact metaphors to stimulate environmentally friendly behavior: The roles of response efficacy and evaluative persuasion knowledge. Environmental Communication, 13(8), 995–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1544160

- Meyers-Levy, J., Louie, T. A., & Curren, M. T. (1994). How does the congruity of brand names affect evaluations of brand name extensions? Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.1.46

- Mishra, A. S., Roy, S., & Bailey, A. A. (2015). Exploring brand personality-celebrity endorser personality congruence in celebrity endorsements in the Indian context. Psychology & Marketing, 32(12), 1158–1174. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20846

- Moore, M. M., & Yang, J. Z. (2020). Using eco-guilt to motivate environmental behavior change. Environmental Communication, 14(4), 522–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2019.1692889

- New Zealand Herald. (2019). Extinction Rebellion's celebrity supporters called out for eco-hypocrisy. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/travel/extinction-rebellions-celebrity-supporters-called-out-for-eco-hypocrisy/T7NQFDINNVH3MWB63WDBEKN2RA/.

- Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

- Osgood, C. E., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1955). The principle of congruity in the prediction of attitude change. Psychological Review, 62(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048153

- Pedroni, M. (2016). Meso-celebrities, fashion and the media: How digital influencers struggle for visibility. Film, Fashion & Consumption, 5(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1386/ffc.5.1.103_1

- Pilkington, E. (2007). An inconvenient truth: Eco-warrior Al Gore's bloated gas and electricity bills. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/feb/28/film.usa2.

- Pittman, M., & Abell, A. (2021). More trust in fewer followers: Diverging effects of popularity metrics and green orientation social media influencers. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 56(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2021.05.002

- Ratliff, K. A., Howell, J. L., & Redford, L. (2017). Attitudes toward the prototypical environmentalist predict environmentally friendly behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.009

- Reeder, G. D., Vonk, R., Ronk, M. J., Ham, J., & Lawrence, M. (2004). Dispositional attribution: Multiple inferences about motive-related traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(4), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.530

- Reinikainen, H., Munnukka, J., Maity, D., & Luoma-aho, V. (2020). You really are a great big sister’–parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(3-4), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1708781

- Rifon, N. J., Choi, S. M., Trimble, C. S., & Li, H. (2004). Congruence effects in sponsorship: The mediating role of sponsor credibility and consumer attributions of sponsor motive. Journal of Advertising, 33(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2004.10639151

- Royston, J. (2021). Prince Harry and Meghan Markle called hypocritical for flying 21 private jets in two years. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/prince-harry-meghan-markle-hypocritical-21-private-jets-since-2019-climate-change-environment-1633426.

- Sailer, A., Wilfing, H., & Straus, E. (2022). Greenwashing and bluewashing in black Friday-related sustainable fashion marketing on Instagram. Sustainability, 14(3), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031494

- Santora, J. (2021). 100 Influencer Marketing Statistics For 2021. https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-statistics/.

- Schmuck, D., Matthes, J., & Naderer, B. (2018). Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. Journal of Advertising, 47(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2018.1452652

- Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898

- Shan, Y., Chen, K.-J., & Lin, J.-S. E. (2020). When social media influencers endorse brands: The effects of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. International Journal of Advertising, 39 (5), 590–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1678322

- Sparkman, G., & Attari, S. Z. (2020). Credibility, communication, and climate change: How lifestyle inconsistency and do-gooder derogation impact decarbonization advocacy. Energy Research & Social Science, 59, 101290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101290

- Spears, N., & Singh, S. N. (2004). Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 26(2), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164

- Spry, A., Pappu, R., & Bettina Cornwell, T. (2011). Celebrity endorsement, brand credibility and brand equity. European Journal of Marketing, 45(6), 882–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111119958

- Statista. (2021). Distribution of Instagram users worldwide as of July 2021, by age and gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/248769/age-distribution-of-worldwide-instagram-users/.

- Stone, J., & Fernandez, N. C. (2008). To practice what we preach: The use of hypocrisy and cognitive dissonance to motivate behavior change. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 1024–1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00088.x

- Stubb, C., & Colliander, J. (2019). This is not sponsored content”–The effects of impartiality disclosure and e-commerce landing pages on consumer responses to social media influencer posts. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.024

- Till, B. D., & Busler, M. (2000). The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673613

- Torres, P., Augusto, M., & Matos, M. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychology & Marketing, 36(12), 1267–1276. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21274

- United Nations. (2021). IPCC report: ‘Code red’ for human driven global heating, warns UN chief. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/08/1097362.

- Van der Werff, E., Steg, L., & Keizer, K. (2013). It is a moral issue: The relationship between environmental self-identity, obligation-based intrinsic motivation and pro-environmental behaviour. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1258–1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.018

- Verlegh, P. W., Ryu, G., Tuk, M. A., & Feick, L. (2013). Receiver responses to rewarded referrals: The motive inferences framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(6), 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-013-0327-8

- Vlek, C., & Steg, L. (2007). Human behavior and environmental sustainability: Problems, driving forces, and research topics. Journal of Social Issues, 63(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00493.x

- Voorveld, H. A., Van Noort, G., Muntinga, D. G., & Bronner, F. (2018). Engagement with social media and social media advertising: The differentiating role of platform type. Journal of advertising, 47(1), 38-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1405754

- Warren, L. (2020). Sustainable influencers: Hypocrites, or catalysts of change? https://sourcingjournal.com/denim/denim-influencers/sustainable-fashion-influencers-responsible-consumption-marketing-brands-traackr-206078/.

- Weismueller, J., Harrigan, P., Wang, S., & Soutar, G. N. (2020). Influencer endorsements: How advertising disclosure and source credibility affect consumer purchase intention on social media. Australasian Marketing Journal, 28(4), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.03.002

- Wellman, M. L., Stoldt, R., Tully, M., & Ekdale, B. (2020). Ethics of authenticity: Social media influencers and the production of sponsored content. Journal of Media Ethics, 35(2), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2020.1736078

- Woodcock, J., & Johnson, M. R. (2019). Live streamers on twitch.tv as social media influencers: Chances and challenges for strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(4), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1630412

- Xiong, Y., Cheng, Z., Liang, E., & Wu, Y. (2018). Accumulation mechanism of opinion leaders’ social interaction ties in virtual communities: Empirical evidence from China. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.005

Appendix

Figure A1. Example of stimulus materials: account overview incongruent + micro-influencer. Note. Introduction matching this condition: “You will now see an Instagram account, and afterwards an Instagram post, both from Carly Brown. Carly Brown is an Instagrammer with 3317 followers. She does not have a verified account. Only famous people get a verified account.

Carly mainly posts about shopping for brand new clothes, making recipes with meat and loves taking trips by plane to new destinations. She loves shopping and traveling.

Take your time to carefully look at the Instagram account and the post and answer the questions.”

(On next page, above picture:) “Imagine you are browsing through Instagram and encounter this Instagram account of Carly Brown.”

Figure A2. Example of stimulus materials: account overview congruent + meso-influencer.Note. Introduction matching this condition: “You will now see an Instagram account, and afterwards an Instagram post, both from Carly Brown. Carly Brown is a famous environmentally friendly Instagrammer with 331,000 followers. She also has a verified account, recognizable by the blue check behind her name, so people know that she is not a fake account. Only famous people get this.

Carly mainly posts about shopping for vintage clothes, making vegetarian recipes and loves taking trips by train to new destinations. She cares about the environment and loves nature.

Take your time to carefully look at the Instagram account and the post and answer the questions.”

(On next page, above picture:) “Imagine you are browsing through Instagram and encounter this Instagram account of Carly Brown.”

Figure A3. Stimulus materials: pro-environmental post.Note. On page with picture: “Imagine that after you encountered Carly Brown’s Instagram account you see this post.”

Table A1. Full details of measured scales in order of appearance in questionnaire.