ABSTRACT

A growing momentum of artists and cultural institutions addressing climate change in their works and exhibitions can be observed in recent years. It is important to understand how such art is covered in quality newspapers because they can give meaning and importance to climate change, and cultural journalists act as mediators between cultural producers and consumers. This research asks: How is exhibited, visual climate-related art presented and evaluated in US and European quality newspapers between 2015 and 2021? Through qualitative content analysis of approximately 125 newspaper articles, this study reveals that climate-related art has been given a platform in quality newspapers, although more in some than others. It is frequently reported as reflecting on society – often the problems, and less the solutions – and shaping society. Climate-related art is evaluated based on its subversive power, topicality, environmental sustainability, and artistic qualities.

Introduction

“Art is not a mirror held up to reality/society but a hammer with which to shape it”. This famous quote, often attributed to German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht, is the point of departure for our research on the coverage of visual arts addressing climate change in quality newspapers: How do newspapers cover climate-related art, as a hammer fostering climate action; or is art mainly reported as reflecting the changing climate realities?

Climate change is a paramount challenge facing humanity. International conferences and reports continuously warning about the disastrous effects of climate change, and the high profile of Greta Thunberg, Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion activism added to the heightened awareness surrounding climate change. An increasing number of artists (Galafassi et al., Citation2018; Giannachi, Citation2012) and cultural institutions have addressed this issue as well (Demos, Citation2016; Kagan, Citation2011). This connection with climate change may be explicitly made by the artist, other artworld agents, or actors writing about the art, such as cultural journalists. For this study, we define climate-related artworks following Galafassi et al. (Citation2018) as artworks “whose content and themes are centred on climate change” (p. 2, supplementary material). It could also involve works that were “not originally intended as a commentary upon climate change” but reinterpreted (Doyle, Citation2019, p. 42).

Climate-related art is not only discussed within the art world but also in mainstream media, for instance in “Can Art Help Save the Planet?” in The New York Times or “Artists on Climate Change” in The Guardian. However, there exists little systematic investigation of visual art addressing climate change, and especially its coverage in quality newspapers. Yet, this is relevant to understand because quality newspapers can be agenda setters and tend to reflect public concern with regard to climate change. Moreover, art journalists and reviewers act as mediators between producers and consumers. Their assessment provides visibility and legitimacy to artworks (Kristensen, Citation2018).

This research investigates news media coverage of climate-related art since 2015 in selected US and European newspapers. Specifically, we examine how exhibited, visual climate-related art is presented and evaluated in US and European quality newspapers between 2015 and 2021. In line with other scholars’ conclusions to refrain from prescribing specific ways of content engagement for the arts (e.g. Ribac, Citation2018), we do not offer a normative approach regarding art and social content. Instead, this research aims to inquire how Brecht’s statement applies to journalism about climate-related art. Answering this question will allow asserting to what extent climate-related art receives a stage in news media, how it is presented (in terms of a social discourse of mirror and hammer), and how it is evaluated, particularly in the key genre of reviews.

Media coverage of climate change

The media play a crucial role “in conveying, translating, interpreting and giving meaning and importance – or not – to the complex scientific and policy aspects of climate change” (Moser, Citation2016, p. 350). Although the media landscape is changing due to the development of social media (Barkemeyer et al., Citation2017), and while newspapers are no longer considered to influence opinions at large (Moser, Citation2016), they still play an important role with regard to the coverage of climate change. Quality newspapers act as a mirror of opinions and public concerns about climate change. Furthermore, they may influence – to some extent – certain circles, such as the political, economic and cultural elites.

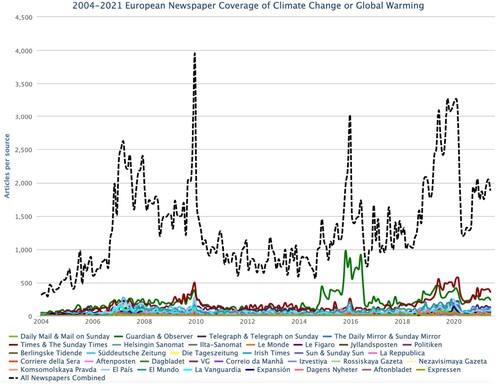

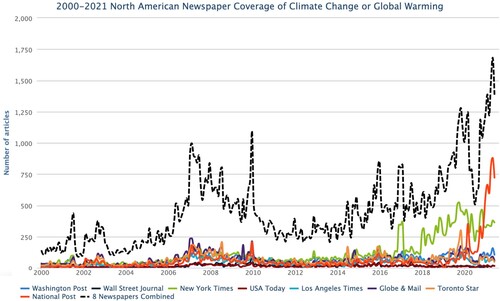

In the last twenty years, newspaper coverage of climate change in the United States and Europe has developed precipitously (Boykoff et al., Citation2021), see and . This coverage is particularly frequent when international climate change conferences are taking place and important political agreements are being adopted. Especially 2015 marks an important year regarding sustainable development. The universal Paris Agreement was adopted at the Conference of the Parties (COP21), striving to limit warming preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius in comparison to pre-industrial temperatures. In the same year, the UN General Assembly launched the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Recently, another phenomenon seems to partly explain wider press coverage of climate change: activist Greta Thunberg and global climate movements such as Fridays for Future.

Figure 1. European Newspaper Coverage of Climate Change or Global Warming, 2004-2021. Media and Climate Change Observatory Data Sets. Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Science (Boykoff et al., Citation2021). Figure reproduced with permission.

Figure 2. North American Newspaper Coverage of Climate Change or Global Warming, 2000-2021. Media and Climate Change Observatory Data Sets. Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado (Boykoff, Daly, McNatt & Nacu–Schmidt, Citation2021). Figure reproduced with permission.

The role of journalism in reporting on the arts

Cultural journalists mediate between cultural consumers and producers (Kristensen, Citation2018). Consequently, they are referred to as cultural intermediaries or cultural mediators (Janssen & Verboord, Citation2015). As part of that role, they act as gatekeepers (Heikkila et al., Citation2018), i.e. they select cultural products out of a myriad of possibilities. This can “influence which cultural products gain broader attention in the cultural public sphere and among cultural consumers – and which are ignored or only picked up by niche publics” (Kristensen, Citation2018, p. 2171).

Hellman and Jaakkola (Citation2012) and Jaakkola (Citation2015) provide important contributions to the understanding of art/cultural journalism as being characterized by a dual nature: it can lean on the aesthetic paradigm (evaluative, opinionated criticism) and the journalistic paradigm (informative, fact-based coverage of the arts). Traditionally, cultural journalists tended to follow the aesthetic paradigm. However, in some newspapers the journalistic paradigm has been found to be dominant in cultural journalism, “employing standard journalistic methods, such as interviews and feature stories, and news values, such as significance, scale and nearness” (Hellman & Jaakkola, Citation2012, p. 797).

The newspaper sections and genre in which the articles in our sample appear need to be taken into consideration when assessing how art is presented and evaluated. It is, therefore, useful to list the main characteristics of these sections and genres. First, in the cultural section, art, popular culture, lifestyle and consumption are addressed (Heikkila et al., Citation2018). Here, one may find elements of the aesthetic and journalistic paradigm. Second, the key genre of art review in cultural sections: Cultural journalists, and particularly art critics act as evaluators, meaning and tastemakers in art reviews (Purhonen et al., Citation2019). There, it is defined “what counts as valuable culture and good taste in specific moments in time” (Heikkila et al., Citation2018, p. 670), which can influence consumer perceptions (Kristensen, Citation2018). Consequently, the review is strongly connected to the above-mentioned aesthetic paradigm (Hellman & Jaakkola, Citation2012). Third, while a large part of cultural classifications is found in the cultural sections (Heikkila et al., Citation2018), art that addresses socio-ecological themes may also be covered in other sections, like the science or news section. These are characterized by objectivity in contrast to the “soft news’, lifestyle journalism style or the in-depth evaluations of art reviews.

Coverage of climate-related art in quality newspapers

This study focuses on the visual arts and combinations with other genres and disciplines, for example audio-visual and art-science. The visual arts have the potential to render an abstract issue tangible and sensible in aesthetic and novel ways. Moreover, they can make climate change meaningful to people’s everyday lives (Doyle, Citation2019; Roosen et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the focus is on exhibitions for the following reasons. First, increased international attention to the urgency of environmental topics led to numerous exhibitions in the last decades, which suggests that art institutions have taken interest in this topic (Demos, Citation2016; Kagan, Citation2011). Second, exhibitions increase the news value in journalism because they draw attention as a society event like a vernissage or grand opening at a museum. Third, exhibitions offer places for meaning-making, embodied learning and interactive engagements with audiences, and therefore represent a distinctive way how cultural institutions engage with major societal challenges such as climate change (Newell et al., Citation2017). Fourth, while the increase of exhibitions dealing with climate-related themes is impressive, they also need to be critically investigated. As Demos (Citation2016) observes, exhibitions that strive to create awareness of climate change are also contributing to it through, for example, energy consumption and the transport of artworks. Similarly, Power (Citation2021) refers to art practices’ environmental footprint, summarizing it under the term “sustainability in the arts’.

Social and artistic discourse

The mediation – how journalists present and evaluate climate-related art – has not yet been investigated in-depth. However, scholarly work on the coverage of art dealing with social topics was consulted to strengthen our theoretical framework and operationalization. In their study of trends in contemporary art discourse, Roose et al. (Citation2018) identify two professional art discourses in a major art magazine: a discourse covering form and aesthetics of art and a discourse connecting art to social ideas, “social content”, which is “art that includes social and/or political themes” (p. 308).

The emergence of the social discourse is among others due to state funding systems emphasising the instrumental benefits of art. This leads artists and art organizations to point out their social functions (Alexander, Citation2018), which can then enter the professional art criticism discourse. Similarly, Maggs and Robinson (Citation2020) observe that art is put in the service of sustainability and seen as a magic bullet of social change in various fields.Footnote1 Therefore, it can be expected that art which addresses the topic of climate change will be covered by a social discourse, i.e. as art being connected to the socio-ecological issue of climate change.

Social discourse: coverage of climate-related art as shaping and reflecting society

One way of understanding the connection between art and society is through shaping theory according to which art influences society (Alexander, Citation2021). With regard to sustainability and climate change, this can be referred to as “sustainability through art” (based on Power, Citation2021) or “climate engagement through art” (based on Bentz, Citation2020).Footnote2 The present research distinguishes between different shaping approaches, which allows exploring as what kind of hammer art is covered in the media: as art demanding change (e.g. activist art) or itself changing socio-ecological contexts (e.g. pragmatic approaches), individual and societal processes (e.g. open-ended, transdisciplinary art).

Based on Demos (Citation2016; Citation2017) and Groys (Citation2014), activist art can be understood as challenging existing structures and stressing the need for political or social change. It can receive international press coverage, such as the activist art project Climate Games. Activist art may be happening independent of institutional affiliations. However, it can also be shown in traditional art venues (Demos, Citation2016; Kagan, Citation2011). Certainly, it matters whether the exhibition or institution displays art that is activist, or if the institution is itself focusing on action. New museums, such as The Climate Museum, prove that the latter can be the case.

Close to Brecht’s meaning of art as a hammer to shape reality, furthermore, is art that is pragmatically fostering change and transforming matters (i.e. beyond demanding change). For example, pragmatic art approaches that are implementing prototypes and experiments in social contexts (Brown, Citation2014) or emphasizing the transformation of ecologies while connecting to the systems that create the environment (Demos, Citation2016). Art, particularly when it is open-ended, co-creational, transdisciplinary, may, moreover, operate on a transformative level engaging “people with climate change on a deep, emotional, and personal level” (Bentz, Citation2020, p. 1599). Given demands to shift towards stories of positive transformation and personal narratives around climate change (Moser, Citation2016), a coverage of art as doing precisely that can be expected: offering pragmatic or open-ended, personal approaches.

Another way of understanding the connection between art and society is through reflection theory which states that art reflects society (Alexander, Citation2021). Applied to the topic of climate change, this means that visual arts can be seen as a mirror or magnifying glass to make wicked problems such as climate change tangible. Nurmis (Citation2016), for example, found that artists who work on climate change have “the desire to hold up a mirror to the public” that shows the role of humanity in creating “the ecological reality” (p. 511). Part of such artistic engagements can take a more communicative role “without shaping or questioning fundamental methodological approaches or systemic givens” (Bentz, Citation2020, p. 1597). Journalists may report climate-related art as being a mirror of reality, of climate change causes and impacts, comparable to considering art and photographs as “visual forms of eye witnessing” in journalism during crises such as war, as discussed by Zelizer (Citation2007).

It must be mentioned that the link between art and society is complex, as it is influenced by various actors, such as the artists, mediators and audiences who impact artistic expressions and their meaning (Alexander, Citation2021). Moreover, it is not simply unidirectional (art only reflects or shapes society), but more multifaceted. Ballard (Citation2017), for example, argues that artworks “in the age of extinction” cannot only reflect horrors and concerns, but also create sympathy and ways to “critically question our world” (p. 257). Similarly, Bentz (Citation2020) acknowledges that the boundaries between the different potential processes that art is able to provide, from more communicative to transformative, are blurry instead of clear-cut. Because of the complex link between art and society, art that is regarded as reflecting could also be seen as initiating perspective shifts or behavioural changes in art audiences. Consequently, the aspects of social discourse are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

But is it (seen as) art?

According to the sociological perspective on art, “the appreciation of an artwork is dependent on the social context in which it is seen. […] the value of an artwork does not [only] reside in the work itself, but is produced and constantly reproduced by the artist, intermediaries, and the audience” (Velthuis Citation2003, p. 184). Journalists engage in artistic discourse when they refer to aesthetic aspects of the work and other elements which can denote artistic worth (Roose et al., Citation2018). Regarding the topic of climate change, numerous artworks have been discussed as being sublime, like photographs by Edward Burtynsky and paintings by Diane Burko (Nurmis, Citation2016). Terms, such as Anthropocene sublime (Nurmis, Citation2016), and the industrial sublime (Demos, Citation2017) are used to denote the coexistence of disturbing and beautiful elements in one image. It seems reasonable to expect that the coverage of climate-related art may include references to the aesthetic concepts of beauty and the sublime.

Journalists may also use popular aesthetic evaluation criteria, which centre around emotional aspects, the participatory experience (Brandellero & Velthuis, Citation2018) and employ an audience-oriented style of evaluating the art. For instance, one of the most well-known environmental artists, Ólafur Elíasson, is known for his immersive installations, in which the audience becomes an active spectator (Hornby, Citation2017). Artworks then make “use of social forms”, which “refers to art that aims to initiate social interactions – for example, art in which members of the audience have to engage physically with the artwork or need to cooperate or co-create the work” (Roose et al., Citation2018, p. 308).

Journalists and particularly art critics can also evaluate certain art as lacking artistic qualities. Activist and pragmatic art may receive such labels (Brown, Citation2014; Kagan, Citation2011). Art historians, curators and artists alike frequently comment on a tension between activist and artistic goals. Groys (Citation2014), for instance, points out that “[t]raditional artistic criticism operates according to the notion of artistic quality. From this point of view, art activism seems to be artistically not good enough: many critics say that the morally good intentions of art activism substitute for artistic quality” (p. 1). Groys (Citation2014) also questions the validity of this criticism on art activism given that aesthetic criteria have been changing in the past. Moreover, the tension between artistic and activist goals can also be a creative tension. Miles (Citation2014), for example, argues that aesthetics and activism are not mutually exclusive. As Felshin (Citation1995) asked about activist art “but is it art?”, the present study gauges whether climate-related art is seen as art.

Data and method

Articles published between 2015 and 2021 in regions that are particularly responsible for emissions and at the same time resourceful to tackle the problem were examined. The USA and European Union score highly on measurements of recent emissions, historic emissions and per-person emissions. They are also among the wealthiest countries and hence considered to have the resources to develop global solutions. Instead of a one-nation analysis, this research reaches beyond national borders, a trend that can be observed in various communication studies (Hanusch & Hanitzsch, Citation2017). While generalizable cross-national comparisons are not possible given the small and exploratory nature of the present research, it does, however, allow us to “arrive at more universal understandings” (Hanusch & Hanitzsch, Citation2017, p. 525). The selection of Germany, the Netherlands and United Kingdom within the European Union was also made based on pragmatic reasons: English, German and Dutch being our first and second languages.

The newspapers were selected based on the following criteria. First, they are quality newspapers (in contrast to tabloids) with high circulation. While they might not influence opinions at large, they have the potential to impact policy discourses and elite circles – where action is needed to achieve change. Second, newspapers with either a politically left or right-centred orientation were included to avoid a myopic viewpoint. They are “political actors in their own right, as public extensions of deep social divisions, and as echo chambers for opinions in a profoundly political, politicized, and polarized debate” (Moser, Citation2016, p. 351). Third, the selected newspapers have electronic editions, which made them accessible for our research.

The data was collected through the media search platform LexisNexis (The New York Times, The Guardian, The Times, Süddeutsche Zeitung, de Volkskrant, NRC Handelsblad), ProQuest (The Wall Street Journal) and FAZ Archiv (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung). The keywords “climate change”, “art” and “exhibition” or “museum” were used. When possible, the connector “w/p” was used, which restricts the search results to articles that contain the words “climate change” and “art” in the same paragraph, ensuring that the article talks about them in a connected way. These results were sorted by the search platform’s relevance function, and then manually checked for their relevance. They qualified for the present study when: a. they covered visual art or a combination of visual and other art forms; b. the art was exhibited; c. the artists explicitly addressed climate change, or the exhibited art is put in relation to climate change by the journalist (climate change can be the focus or part of the exhibition); and d. when the articles were longer than 50 words. The criteria limited the search results greatly (often the article contained too little content about climate-related art). In total, 124 articles were analysed by use of content analysis which is suitable for the systematic analysis of texts (Mayring, Citation2000), including newspaper articles (Janssen et al., Citation2008). The supplementary material summarizes the operationalization of the various dimensions of social discourse, artistic discourse and evaluation repertoires.

Results

Climate-related, exhibited art receives coverage in all the studied quality newspapers, however, to varying extents. Some newspapers with a left political orientation and those with a more global outreach show more results than those with a right orientation or less global reach ().

Table 1. Search results for keywords (German and Dutch equivalents) for articles published between 2015 and 2021; and number of analysed articles. *w/p function not available.

Between 2015 and 2020, coverage increased in several newspapers. Throughout 2020 and until January 2021, we observed a sudden decline. This might be because the focus shifted towards other topics such as the pandemic, while numerous art exhibitions were cancelled.

An exhibition addressing climate change is typically featured in the arts and culture section. However, the coverage of climate change is not resort-dependent and may be covered across various sections from economy to science to culture. The analysis is, therefore, not limited to the arts and culture section. summarizes the number of articles, including the genres, that were analysed per newspaper. This distinction into genres is particularly relevant when presenting the results regarding the evaluation of climate-related art (see below).

Table 2. Number of analysed articles per newspaper and genre.

Covered art, exhibitions and artists

Journalists usually used descriptions, such as art about climate change when referring to the exhibited art. In the instances where they labelled climate-related art, they mainly used environmental art, ecological art or eco-art. Other labels were socially engaged art and climate change art. Various art genres were covered, from two-dimensional representations to three-dimensional installations, including combinations of different forms (e.g. audio-visual), and works at the juncture of art and design, art and science. A striking, recurring theme across many articles was that of collaborations within but also beyond the art world whereby a blending of the worlds of art and science took place (e.g. Helen Mayer Harrison or Tomás Saraceno). Also, artists were covered when participating in scientific missions (e.g. Justin Brice Guariglia), and incorporating scientific data in their works (e.g. Michael Pinsky).

While a wide variety of artists, exhibitions and cultural institutions were reported, certain high-profile artists, exhibitions and museums receive recurring coverage. Among the most mentioned artists were Ólafur Elíasson, Tomás Saraceno, Maya Lin and Mary Mattingly. While most articles cover living artists and their exhibitions, some address exhibits of well-known, deceased artists in relation to climate change (e.g. in obituaries of Gustav Metzger, Helen Mayer Harrison). Furthermore, some old masters are reinterpreted concerning climate change (e.g. Hieronymus Bosch), others are re-visualized (e.g. Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea). The occasion of the article was usually an ongoing or upcoming exhibition, often high-profile events such as Biennales. In roughly half the articles, the exhibited, climate-related art was the focus of the piece (particularly in the New York Times and the Guardian), but in other cases topics next to climate change, or other art unrelated to climate change were discussed a well.

Social discourse

Art was presented as reflecting climate realities (mirror) in a majority of the analysed news articles. The art was covered to be reflecting society, eye-witnessing, representing, showing, documenting (and similar terms that indicate reflecting). This category often appeared in relation to art being talked about as reflecting the disastrous impact of humanity on the planet (i.e. art reflecting the problems). Such articles centre around the artwork’s ways of visualizing the topic, the poiesis – the art of bringing something into being. The reflection received an additional meaning in one article which discussed the artworks of an outdoor exhibition showing the consequences of climate change when the exhibition became unexpectedly flooded through extreme weather. Fewer articles discussed exhibitions that reflect solutions in their artworks. For example, artworks that show solutions already in place in cities or that portray visions for the future. Strikingly, the articles that presented art as reflecting society feature recurring phrases about the exhibition as being non-lecturing instead of preaching. This was also often voiced by the quoted artists and curators.

Less frequently than art being presented as reflecting society (mirror), articles presented art as shaping society (hammer), and in numerous cases this overlapped with the mirror category. Art was thereby not only presented as mirror or hammer, but as both mirror and hammer. This research also sheds light on what kind of hammer the exhibited art was covered. Articles reported climate-related art as calling for action whereby the art was regarded as inspiring, calling for or motivating climate action. In these instances, the art was not necessarily also labelled activist. While the meaning between art calling for action and activist art is very close, we coded these separately to receive data in which the art is explicitly labelled activist. Some pieces cover the changing role of institutions, particularly when commenting on activist art. For example, multiple articles discussed newly created or reoriented cultural institutions addressing climate change and other societal topics, such as the Climate Museum in New York City. Others, yet, mentioned challenges, for instance, how audiences might perceive institutions as biased when they take a stand or how they might lose their artistic role. Other articles stated that the cultural institution, while showing activist art, has itself received activism. Activism was also combined with other aspects such as meditation, joy, spiritualism and melancholy. A recurring theme throughout the newspaper articles was that the artist or exhibition, although presented as shaping society (including activist art), was described as not didactic. This suggests that there is not one kind of “hard” activism, but also more subtle activist engagements presented in the media. Some articles talk about open-ended art; however, this kind of engagement was not always seen as transformative (see the “Subversive power” section below). Lastly, a few articles talked about climate-related art as pragmatic/actionist art. Examples are artists Tomás Saraceno and Daan Roosegaarde who work at the intersection of art and science, design, and technology.

Evaluation of climate-related art

In the following sections, articles that evaluate climate-related art are examined. This includes reviews as the key genre for the evaluation of art (around one-third of the total number of analysed articles). Based on the analysis of exhibition reviews, four seminal themes could be identified: Climate-related art is (positively or negatively) evaluated based on its subversive power, topicality, environmental footprint and artistic qualities. Moreover, numerous articles that appeared in the cultural sections of newspapers such as The Guardian and Süddeutsche Zeitung, not posing as exhibition reviews, also made value statements about the exhibited climate-related art which could be captured by the four key themes of evaluation.

Subversive power

Across the evaluations, art’s subversive power was remarked in terms of its ability to convey the urgency of climate change, to lead to changes of perception, and even to action. However, two different evaluation arguments with regard to how art could be subversive emerged.

Journalists of the first evaluation argument type criticized art when it was deemed not clearly enough connected to climate change, confusing, as missing proposals for alternatives, and therefore lacking subversive power. For example, some shows were described to be only understood with a lot of effort or as too diffuse. Often, such evaluations were made about the entire exhibition of which climate-related art was only a part. At times, an exhibition was still reviewed positively, for instance as being wonderful as an artistic response, even when the journalists were unsure about the show’s ability to communicate about the environmental crisis.

The second kind of argument around art’s subversive power was related to art’s openness, otherness, novelty, and ability to create tension. For example, an exhibition’s ability to embrace confusion was evaluated positively because the artist was found to inject an urgent theme with new imagination instead of a simplified or superficial engagement. In contrast, exhibitions were criticized for being predictable, or too similar, for instance regarding dystopian visions. Artworks were also considered as missing tensions because they were seen as too polite or without any particular escalation. Some exhibitions were discussed to be powerful when they included non-Western artists and their perspectives on climate impacts.

Topicality

Evaluating art addressing climate change for its topicality was a recurring theme. For example, when journalists stated that an exhibition was a timely exhibition. Many of the articles, for instance in The New York Times and The Guardian, covered current or upcoming exhibitions that were described as now increasingly dealing with the urgent topic of climate change, at times situated within bigger concepts such as sustainability and the Anthropocene. Exhibitions of the works of deceased artists addressing nature were reinterpreted by journalists with regard to climate change. Such perspectives about nature were seen as all the more urgent now.

Some articles situated the climate-related art historically, acknowledging that, for example, “art with an environmental message isńt new”.Footnote3 A small number of articles referred to the 1960s, where a new eco-consciousness and eco-art movement arose, and pioneering artists of the land art movement emerged. Some artists, such as Helen Mayer Harrison or Gustav Metzger, were mentioned to be engaging with the topic before it made headlines. Artists were praised for not following the recent trend of climate alarmism and for instead working on this topic for decades, receiving a new momentum with the increased urgency. In contrast to praising the timeliness of an exhibition, addressing climate change may be seen as a challenge, particularly in articles of the most recent years. Journalists wonder, for example, if such an exhibition can avoid the thematic heaviness.

Environmental footprint

Many articles across left and right-centred newspapers and countries, and across art presented as reflecting and shaping society, referred to or cited remarks regarding sustainable processes in the art world, mostly focusing on the environmental instead of also on the social dimension. This was expressed in unfavourable ways when, for example, the art world should practice what it preaches, produce less, or include energy and water use in a cultural institution’s annual report. Art addressing the environment at large contemporary art events was seen as ironic. At times, the need for responsibility was raised by art world agents, such as artists, themselves. The art world also received criticism for unsustainable transport of materials, travel, non-local art, and the possible disruption of ecosystems. Few articles commented on an exhibition’s environmental friendliness. For example, when exhibitions were found to focus on local audiences, to use solar panels or windmills for energy, to take into account nature, for which artists worked with climate-neutral materials or on artworks that have a positive impact on the environment. Jason deCaires Tayloŕs underwater museum sculptures, for instance, function as artificial reefs where animals and plants can thrive.

Artistic qualities

Journalists evaluated art that reflected and/or shaped society often in relation to traditional aesthetics (the beauty, sublime), and the participatory immersive experience (audience-oriented review, popular aesthetic criteria).

Particularly for art shaping society, such as activist art, we earlier posed the question: but is it seen as art? In multiple articles across various newspapers, climate-related art presented as shaping society was mentioned together with descriptions such as beautiful, aesthetic and artful ways. This is exemplified in the account of artist Janet Laurence’s work: “Laurence's work is, before everything, very beautiful. The beauty of it is partly to entice an audience. “I am very aware in my practice of creating an attraction to enter a space,” she says. “I want you to linger.” This aesthetic is tightly coupled with politics; hers is an activist practice” ().Footnote4

Figure 3. Janet Laurence, Deep Breathing: Resuscitation for the Reef, 2015–2016 / 2019 (left), installation view, Janet Laurence: After Nature, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2019, wet, coral, coral drill core and dredge specimens, resin castings, 3D-printed skeletons, fish bones, tubing, laboratory glass, silicon, mirror, pigment, thread, acrylic, sand, glass, shells, clay, video projections, coral block CT scan from the Geocoastal Research Group, School of Geosciences, Marine Studies Institute, University of Sydney, selected specimens from the Collection of the Australian Museum, Sydney, selected specimens from the Geocoastal Research Group, School of Geosciences, Marine Studies Institute, University of Sydney, collection of the artist, image courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Jacquie Manning; Theatre of Trees, 2018 –2019 (right), installation view, Janet Laurence: After Nature, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2019, four circular structures, mesh, silk, duraclear, audio, video projections, books, scientific glass, plant specimens, botanical models and substances, collection of the artist, image courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Jacquie Manning.

In contrast, there were also challenges raised relative to judging the aesthetic quality, particularly of pragmatic or activist art. Some exhibitions were also seen as lacking art. Art critics and journalists would then wonder where the artistic elements were or ascertain that the work went at the expense of art. Some articles make clear that what is on display is not perceived as art, but rather science, architecture, or a political project. Few said that by including socially engaged art, institutions might lose their role as an artistic centre, taking a new role of sparking discussions about climate change and other societal topics.

Discussion

A few general observations emanated from this study. Our research finds that climate-related art is covered in selected US and European quality newspapers. Some, however, addressed exhibited, climate-related art more than others. This might be because they are more inclined to write about the general topic of climate change (The New York Times, The Guardian, see and above); the step to reporting about climate-related art might then be smaller. It could also be attributed to the global reach of some of these outlets. Furthermore, scholars have pointed out that the distinction between environmental art and ecological art is not clear (Kagan, Citation2011) and this was also the case in the media coverage. Next, climate-related artworks may not only contain visual elements, but they can operate at the juncture of audio and visual, art and design, art and science (as discussed by e.g. Yusoff & Gabrys, Citation2011). Moreover, journalists frequently included remarks about collaborations, which corresponds to scholars’ discussions of collaborations, in particular art-science (e.g. Gabrys & Yusoff, Citation2012; Galafassi et al., Citation2018). This suggests that collaborations are an important part of (the discussion of) climate-related art.

Regarding the discourse used, this research applied the conceptualization of Roose et al. (Citation2018) to the topic of climate change: climate-related art was, as expected, covered by a social discourse. In terms of the kind of social discourse – covering art as reflecting and/or shaping reality – this research shows that art was often presented as a mirror, usually as reflecting climate problems instead of solutions. On the other side of the spectrum is the depiction of art as a hammer, which is not surprising given the often heavily politicized topic of climate change and the potential of such art (e.g. activist art) to generate press coverage (Demos, Citation2017). In general, in numerous articles, the art was not presented as mirror or hammer separately, but as mirror and hammer. Therefore, a clear distinction between reflection and shaping in the coverage of climate-related art was not always possible. This underlines the complicatedness of the art-society link – art reflects and shapes society in complex ways (Alexander, Citation2021) – also in the media coverage of art. It also echoes the finding by Bentz (Citation2020) regarding the blurry boundaries of art’s multiple potentials.

The analysis further revealed that art activism is portrayed in various facets, for example non-lecturing activism or activism combined with characteristics such as joy and meditation. Our inquiry also supports recent findings of the changing role of cultural institutions in addressing social topics such as climate change (Newell et al., Citation2017). Strikingly, few artworks were seen as pragmatic/actionist, which shows only a minority was viewed as acting as a hammer fostering change themselves; more were presented as demanding change. Overall, there were fewer mentions of art reflecting or implementing solutions. While scholars have raised the need for more solution-oriented approaches in the general communication of climate change (Moser, Citation2016), and in the art world (Sommer & Klöckner, Citation2019), a majority of newspaper coverage did not present art as reflecting or implementing solutions, though some do demand more solution-oriented art. This will be critically discussed below.

In terms of the evaluation of art, the analysis showed that climate-related art is evaluated for its topicality, artistic qualities, subversive power, and environmental friendliness. We will discuss each in the following sections, first starting with the theme of topicality. Remarks regarding a general increase in climate-related art are not necessarily evidence of something really being on the increase. However, as mentioned earlier, scholars, too, have observed that it is on the rise (e.g. Galafassi et al., Citation2018; Giannachi, Citation2012). It is, nevertheless, important to stress, as did a few news articles and as do scholars (e.g. Galafassi et al., Citation2018), that climate-related art – not to mention art addressing socio-ecological topics – is not a recent phenomenon. Climate concerns already existed in the 1970s, and ecological concerns date back to artists who addressed colonialism, the conquest of Native land, and industrialization over the past centuries (Kusserow et al., Citation2018) and before.

Second, regarding artistic qualities, we found that many articles referred to the beauty and the (Anthropocene, industrial) sublime of the artwork. Moreover, emotional aspects and social forms (e.g. participatory experience; Roose et al., Citation2018) were recurring popular aesthetic evaluation criteria. Reviews were divided in terms of the perceived artistic qualities, particularly of art regarded as shaping society. At times described as beautiful, other journalists questioned the presence of art, which indicates the presence of traditional artistic criticism in some cases (Groys, Citation2014), and that the appreciation not only lies in the artwork itself but that it is (re)produced by intermediaries (Velthuis, Citation2003).

It is, of course, not new that art is evaluated based on aesthetic criteria. What is particular for the topic of climate change – and possibly other sustainability-related issues – is that this art can be judged for its supposed (in)ability for change with regard to climate change (i.e. applying the concept of “sustainability/climate engagement through art” with clear instrumental expectations). This tendency can be viewed rather critically, particularly if artists never set out to achieve a certain kind of engagement that they are judged for. Moreover, characteristics such as being confusing, diffuse, open-ended (for which art was negatively evaluated numerous times) could, in fact, be particularly valuable for a topic that has a lot of preconceptions and dominant discourses around it. After all, that is where the power of art lies: it can ask questions, but it does not necessarily need to offer solutions (Bentz, Citation2020; Galafassi et al., Citation2018). Otherwise, artistic freedom and art’s subversive power are at risk (Miles, Citation2014; Maggs & Robinson, Citation2020).

Lastly, we believe that the discussions surrounding sustainability in the art world are especially fruitful, illustrated by a quote from curator Karl Kusserow, cited in The New York Times:

There’s a crescendo of interest in both art that is itself about the environment and art that is self-consciously environmental, and I think that’s entirely understandable and good, because it draws attention to these dire situations we’re facing.Footnote5

Conclusion

This study marks the first attempt to map the coverage of climate-related art in printed media in Europe and the United States. The coverage of art is multifaceted but certain dominant themes emerged. Climate-related art was very frequently presented as a mirror of societal problems related to climate change. When art was viewed as shaping, it was often presented as art calling for action and activist art. Art activism is not necessarily talked about as “hard activism” but as non-didactic, non-lecturing, meditative, i.e. there exist different nuances of art activism. Regarding the evaluation of climate-related art, it can be concluded that it is not only based on aesthetic criteria, but also its topicality, subversive power, and environmental sustainability.

Even though these findings could serve as a basis for recommendations about how artists best address climate change as content in their work based on the coverage in news articles, this research does not offer a normative approach regarding art and social content. In addition, we raised caution regarding instrumental expectations. This reflects other scholars’ conclusions to refrain from prescribing specific ways of content engagement for the arts with climate topics because a multiplicity of art narratives is needed. In contrast, this research does offer recommendations regarding the (reported) unsustainable practices in the art world. Demands for the art world to become more sustainable in its practices are frequently featured in the reporting about climate-related art. Such demands are likely to become even more prevalent in the future. Environmental and social responsibility need to be strongly embedded in arts policy and practice. There are also implications for media reporting, which could feature more good practice cases and discuss the challenges in implementing sustainable practices (e.g. financial challenges, dependencies on other actors, needs for systemic shifts).

This research is not without its limitations and suggestions for further research. It focuses on selected quality newspapers of North America and Western Europe and the timeframe 2015–2021. Future research could also investigate the reporting in other parts of the world, different timeframes, in tabloids and new media. Moreover, while this study provides a first overview of the coverage of certain climate-related art, an in-depth analysis of specific art and/or topics is needed. Particularly relevant to further investigate could be the coverage of collaborations, sustainability in the art world, and non-Western artists and their perspectives on climate matters. Furthermore, this study focuses on selected social discourses and repertoires of evaluation. In future research, these could be analysed further, and other discourses could be investigated. The analysis of the coverage of climate-related art could also be complemented by shedding more light on the art’s cultural producers and consumers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This can create various challenges, as Maggs and Robinson (Citation2020) insightfully illuminate in their book.

2 This does not imply that art is being used in exclusively or explicitly instrumental ways only (Bentz, Citation2020; Galafassi et al., Citation2018).

3 The Guardian, “Environmental art is on the rise”, 27.03.2016, Anny Shaw.

4 The Guardian, “I want you to linger”, 20.04.2021, Stephanie Converey.

5 New York Times, “Can Art Help Save the Planet?”, 12.03.2019, Alina Tugend.

6 By cultural journalist or art critic (not including art review).

7 For example, news, business, science, living.

8 The New York Times has an “Art and design” section and specific “Art review” part.

9 The Wall Street Journal has an “Arts” section and “Exhibition review” section.

10 The Guardian has a “Art and design” section and specific “Art and design + Reviews” section (which awards star ratings from 0 to 5 stars). The Guardian article selection includes The Observer (The Guardian’s Sunday newspaper) and articles that appear in Guardian Australia, the Australian website of the British newspaper The Guardian.

11 The Times has an “Arts and Culture” section and review section (in which art critics award up to 5 stars).

12 Süddeutsche Zeitung has cultural section “Kultur”, including reviews. Including SZ Extra.

13 Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung has cultural sections “Feuilleton” and “Kultur”. Including Frankfurter Allgemeine Magazin and FAS.

14 De Volkskrant publishes reviews on volkskrant.nl/recensies. Reviews award up to 5 stars.

15 NRC Handelsblad has a culture section and offers reviews of exhibitions.

References

- Alexander, V. D. (2018). Heteronomy in the arts field: state funding and British arts organizations. The British Journal of Sociology, 69(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12283

- Alexander, V. D. (2021). Sociology of the arts: exploring fine and popular forms (Second). John Wiley & Sons.

- Ballard, S. (2017). New ecological sympathies. Environmental Humanities, 9(2), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-4215229

- Barkemeyer, R., Figge, F., Hoepner, A., Holt, D., Kraak, J., & Yu, P.-S. (2017). Media coverage of climate change: An international comparison. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(6), 1029–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16680818

- Bentz, J. (2020). Learning about climate change in, with and through art. Climatic Change, 162(3), 1595–1612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02804-4

- Boykoff, M., Ballantyne, A. G., Chandler, P., Fernández-Reyes, R., Hawley, E., Jiménez Gómez, I., … Ytterstad, A. (2021). European newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming, 2004-2021. Media and Climate Change Observatory Data Sets. Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.25810/fx6e-r462

- Boykoff, M., Daly, M., McNatt, M. and Nacu-Schmidt, A. (2021). North American Newspaper Coverage of Climate Change or Global Warming, 2000-2021. Media and Climate Change Observatory Data Sets. Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.25810/3gtp-yy33

- Brandellero, A., & Velthuis, O. (2018). Reviewing art from the periphery. A comparative analysis of reviews of Brazilian art exhibitions in the press. Poetics, 71, 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2018.10.006

- Brown, A. (2014). Art & ecology now. Thames & Hudson.

- Brown, A. (2014). Art & ecology now. Thames & Hudson.

- Demos, T. (2016). Decolonizing nature. Contemporary Art and the politics of ecology. Sternberg Press.

- Demos, T. (2017). Against the anthropocene: Visual culture and environment today. Sternberg Press.

- Doyle, J. (2019). Imaginative engagements: Critical reflections on visual arts and climate change. In J. H. Reiss (Ed.), Art, theory and practice in the Anthropocene (pp. 39–50). Vernon Press.

- Felshin, N.1995). But is it art?: the spirit of art as activism. Bay Press.

- Gabrys, J., & Yusoff, K. (2012). Arts, sciences and climate change: practices and politics at the threshold. Science As Culture, 21(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2010.550139

- Galafassi, D., Kagan, S., Milkoreit, S., Heras, M., Bilodeau, C., Bourke, S., … Tàbara, J. (2018). ‘Raising the temperature’: the arts on a warming planet. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 31, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.010

- Giannachi, G. (2012). Representing, performing and mitigating climate change in contemporary Art practice. Leonardo, 45(2), 124–122. https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00278

- Groys, B. (2014). On art activism. e-flux journal, 56, 1–14.

- Hanusch, F., & Hanitzsch, T. (2017). Comparing journalistic cultures across nations. Journalism Studies, 18(5), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1280229

- Heikkila, R., Lauronen, T., & Purhonen, S. (2018). The crisis of cultural journalism revisited: the space and place of culture in quality European newspapers from 1960 to 2010. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 21(6), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549416682970

- Hellman, H., & Jaakkola, M. (2012). From aesthetes to reporters: The paradigm shift in arts journalism in Finland. Journalism, 13(8), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911431382

- Hornby, L. (2017). Appropriating the weather. Environmental Humanities, 9(1), 60–83. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3829136

- Jaakkola, M. (2015). The contested autonomy of arts and journalism: Change and continuity of the dual professionalism of cultural journalism. Tampere University Press.

- Janssen, S., Kuipers, G., & Verboord, M. (2008). Cultural globalization and arts journalism: The international orientation of arts and culture coverage in Dutch, French, German, and U.S. Newspapers, 1955 to 2005. American Sociological Review, 73(5), 719–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240807300502

- Janssen, S., & Verboord, M. (2015). Cultural mediators and gatekeepers. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), In: International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (Vol. 5., 2nd ed.). Elsevier.

- Kagan, S. (2011). Art and sustainability: Connecting patterns for a culture of complexity. Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839418031

- Kristensen, N. N. (2018). Churnalism, cultural (inter)mediation and sourcing in cultural journalism. Journalism Studies, 19(14), 2168–2186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1330666

- Kusserow, K., Braddock, A. C., Belarde-Lewis, M., Cruz, T., DeLue, R. Z., Dion, M., Forman, F., et al. (2018). Nature’s nation: American Art and environment. Princeton University Art Museum.

- Maggs, D., & Robinson, J. (2020). Sustainability in an imaginary world: art and the question of agency (Ser. Routledge studies in sustainability). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Social Research.

- Miles, M. (2014). Eco-aesthetics: Art, literature and architecture in a period of climate change. Bloomsbury.

- Moser, S. (2016). Reflections on climate change communication research and practice in the second decade of the 21st century: what more is there to say? WIRES Climate Change, 7(3), 345–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.403

- Newell, J., Robin, L., & Wehner, K. (2017). Curating the future: museums, communities and climate change. Routledge.

- Nurmis, J. (2016). Visual climate change art 2005-2015: Discourse and practice. WIRES Climate Change, 7(4), 501–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.400

- Power, K. (2021). ‘Sustainability’ and the performing arts: Discourse analytic evidence from Australia. Poetics, 89), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101580

- Purhonen, S., Lauronen, T., & Heikkilä, R. (2019). Between legitimization and popularization: the rise and reception of u.s. cultural products in culture sections of quality European newspapers, 1960-2010. American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 7(3), 382–411. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-018-0064-z

- Ribac, F. (2018). Narratives of the Anthropocene: How can the (performing) arts contribute towards the socio-ecological transition? Scene, 6(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1386/scene.6.1.51_1

- Roose, H. H., Roose, W., & Daenekindt, S. B. L. (2018). Trends in contemporary art discourse: using topic models to analyze 25 years of professional art criticism. Cultural Sociology, 12(3), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975518764861

- Roosen, L., Klöckner, C., & Swim, J. (2018). Visual art as a way to communicate climate change: A psychological perspective on climate change–related art. World Art, 8(1), 85–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2017.1375002

- Sommer, L., & Klöckner, C. (2019). Does activist art have the capacity to raise awareness in audiences?—a study on climate change art at the ArtCOP21 event in Paris. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 15(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000247

- Velthuis, O. (2003). Symbolic meanings of prices: Constructing the value of contemporary art in Amsterdam and New York galleries. Theory and Society: Renewal and Critique in Social Theory, 32(2), 181–215. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023995520369

- Yusoff, K., & Gabrys, J. (2011). Climate change and the imagination. WIRES Climate Change, 2(4), 516–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.117

- Zelizer, B. (2007). On “having been there”: “eyewitnessing” as a journalistic Key word. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 24(5), 408–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180701694614