ABSTRACT

Greta Thunberg is a major figure in climate change discourse, featuring prominently in the news and social media. Many studies analyzed the “Greta effect,” but there has not been a review that integrates the diverse literature and consolidates insights into her impact on social media. We provide such a synthesis with a narrative review of 63 peer-reviewed publications that gauged social media reactions to her from different disciplinary perspectives, with various methods, and across a range of contexts. We show how social media have both helped Thunberg mobilize her supporters and harbored backlash from her enemies. This twofold effect varies across different contexts. Yet a comprehensive assessment of the “Greta effect” remains elusive since Thunberg borrows from different kinds of activism but does not neatly fit into any of them. Our review shows how social media have become the most important terrain for contestation around climate change.

Introduction

Greta Thunberg has arguably been the most influential advocate for climate change action since Al Gore with his movie “An Inconvenient Truth” in 2006, which significantly raised awareness for global warming worldwide. After her “school strike for the climate” in 2018, she has spoken at international forums, been much in the news – and become a “global icon” of an environmental activist movement (Olesen, Citation2022, p. 1325). But unlike other advocates like Michael Mann, Bill Gates, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Thunberg is not part of the world of prominent scientists, businesspeople, and politicians. She has been lacking Mann’s epistemic authority, Gates’ financial resources, and Ocasio-Cortez’ political mandate. Her girlhood and autism can even be conceived as barriers to becoming an influential climate change advocate. Yet Thunberg was still able to mobilize a global movement and have considerable impact on policymaking, people’s behaviors, and public discourse about climate change – which is typically termed the “Greta effect” (Hayes & O’Neill, Citation2021). In this paper, we analyze a “Greta effect” on social media specifically, conducting a systematic qualitative in-depth review of relevant peer-reviewed scientific publications.

The “Greta effect”

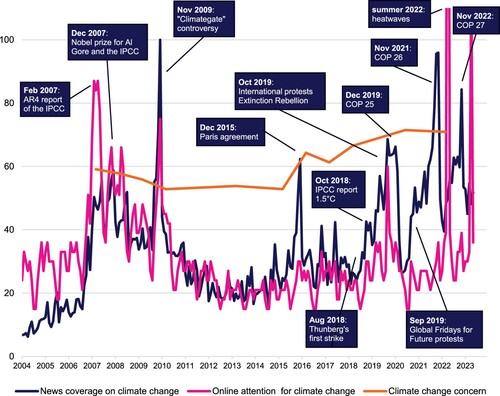

Thunberg brought significant media visibility, online attention, and public awareness to climate change, rivaled only by the UN International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations Climate Change Conferences (COP), and extreme weather events (Hase et al., Citation2021). illustrates this: Events like Thunberg’s first school strike caused spikes in news coverageFootnote1 and triggered peaks in online engagement.Footnote2 General trends of attention – but not the spikes – are also visible in public opinion: Public climate change concernFootnote3 remained fairly steady over many years but increased after 2016, when global newspaper coverage and online search volume grew notably. This illustrates how Thunberg can drive public and media attention (Sisco et al., Citation2021), and how attention is linked to the use of traditional news and online media as well as climate change perceptions (Bogert et al., Citation2023; Thaker, Citation2023).

Figure 1. Trends in news coverage on, online attention to, and public concern about climate change.

Notes: Global news coverage was operationalized as the monthly amount of news items on climate change or global warming in 131 news sources including newspapers, radio, and TV in 59 countries in seven world regions as registered by the Media and Climate Change Observatory of the University of Colorado (Boykoff et al., Citation2023). Online attention was operationalized as the monthly Google search volume for “climate change” worldwide as provided by Google Trends, which uses a metric ranging from 0 to 100 (Google Trends, Citation2023). Climate change concern was operationalized as the percentage of people agreeing that climate change is a “major threat” or “very serious problem” as found in 13 international representative public opinion surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center in 46 countries on all inhabited continents (Pew Research Center, Citation2023). Data were scaled as follows: News coverage data were scaled to 0–100, with 100 corresponding with the maximum amount of news items between 2004 and 2023, i.e. 13,503. Online attention data were scaled to 0–300, with 300 corresponding with the maximum search volume 2004–2023, i.e. 100. Climate change concern data were not scaled, that is, the chart’s Y scale indicates percentages.

The ways in which Greta Thunberg has garnered such an impact on news agendas, online attention, and people’s attitudes and behaviors has been conceived as the “Greta effect” (Sorce, Citation2022) or also “Thunberg effect” (Baiardi & Morana, Citation2021). Both journalists and academic publications used this term to describe Thunberg’s influence on political decision-making (e.g. carbon offset measures, subsidies for renewable energy sources), individual behavior (e.g. sustainable mobility, consumption choices), climate change communication (e.g. news coverage online, social media discourse), and, more generally, her ability to initiate a global activist movement (Haugseth & Smeplass, Citation2022; Sabherwal et al., Citation2021; Watts, Citation2019). In this paper, we will use the more common term “Greta effect” and focus on one particular manifestation of the “Greta effect”: Thunberg’s impact on climate communication in social media – because this is where the “Greta effect” differs considerably from the “effect” of other climate advocates like Al Gore. In contrast to him, Thunberg’s main form of communication has been via social networking sites, online video platforms, web forums, and other forms of social media, where she has been able to reach out to, and interact with, a wide range of supporters and fellow activists (see Cornelio et al., Citation2024). However, she has also provoked a set of opponents, who often attack her personally and are also part of a wider backlash against climate activism (Vowles & Hultman, Citation2021). This backlash has taken novel forms on social media which did not exist at the time of the Al Gore movie and which fit with wider worries about how the Internet is becoming an environment for polarization, misinformation, and conspiracy theories (Park et al., Citation2021).

Many studies analyzed the “Greta effect” through different disciplinary lenses (see Baran & Stoltenberg, Citation2023). Yet it does not easily fit into common themes of research on environmental communication, digital activism, online movements, and climate change advocacy. Although Thunberg can be considered an activist, she can also be seen as a celebrity (Murphy, Citation2021). Hence also the use of her first name, which is often reserved for celebrities like “Che” Guevara or “Madonna” – and which encapsulates the ambiguity between support and backlash: On the one hand, addressing her as “Greta” renders her an approachable person and enacts intimacy between her and her followers (Olesen, Citation2022). On the other hand, it allows critics to portray her as a naïve child (Mkono et al., Citation2020).

Further accounts describe Thunberg as a global youth activist leader (Molder et al., Citation2022, p. 672). However, she has arguably not deliberately sought to lead, directly mobilize, or actively organize a networked activist movement. Her innovation was to initiate strike actions among school age protesters – which then translated into global self-organized movements like Fridays for Future (FFF) and Extinction Rebellion only afterwards, without active leadership by Thunberg, who instead undertook educational awareness efforts (Ballestar et al., Citation2022). The protests of these movements have often not been centered on specific high-profile events like the COPs – which was a departure from previous climate change action. Thunberg spoke at a number of these events, but some argue that she often shied away from putting herself in the foreground and was “relatively passive” (Olesen, Citation2022, p. 1335).

Thunberg is also not an environmental communicator like David Attenborough, who produced television documentaries and popular books related to climate change. Thunberg also made a documentary and wrote books, but Attenborough, a biologist and historian, often assumes the role of a vocal intellectual rather than an activist celebrity and has not positioned himself at the forefront of street protests (Abidin et al., Citation2020; Murphy, Citation2021). Thunberg still, years later, participates in protest actions, but her presence in digital and traditional media has diminished, hence the “Greta effect” has faded (see Rauchfleisch et al., Citation2023). Also, media reporting and social media debate on climate change have changed generally, with much attention paid to extreme weather events and episodic coverage of individual protests (Chen et al., Citation2023; Hase et al., Citation2021).

Scope of this review

In this paper, we will show that there is a variety of approaches trying to situate Thunberg amongst other climate celebrities, activists, and communicators. It will demonstrate how dispersed and disintegrated the literature on the Greta effect is. Moreover, the research agenda has changed, with greater concerns about misinformation or about how social media can contribute to more productive engagement between different sides in the debate. Individual studies therefore do not allow to assess the “Greta effect” on social media, explain how social media benefit or challenge Thunberg, identify parallels to similar figures, and derive implications for future research. To address this, we conducted a systematic narrative review of the current peer-reviewed scientific literature that investigated (social) media communication about Thunberg around the world.

We did a systematic literature search, identified 63 key publications that were most insightful for our review, and engaged in a qualitative in-depth analysis of these publications. We take this approach rather than conducting a purely quantitative (meta)analysis of the literature, because with a total of 174 papers found, a quantitative coding of the main themes in the literature would not yield as much insight as a dissection of key findings. Moreover, the literature is so diverse that a large-scale quantitative analysis would not have been able to reflect the breadth of analytical approaches and usefully synthesize their insights.

Our main research question is: What do we know about the impact of Greta Thunberg on social media? We further break this down into analyses of (1) Thunberg’s presence across the hybrid media ecology, (2) labels quantifying and qualifying her social media impact, and (3) supportive versus backlash dynamics. We will then point out (4) gaps in the literature. Once we have discussed these findings, we will put them into the larger context of climate change communication. We shall also give an analytical account of the various phenomena that have been lumped together under the “Greta effect,” and point to how disaggregating but also synthesizing these phenomena can inform future research.

Background

Climate communication research has long focused on traditional news media (e.g. Boykoff, Citation2011). But recent cross-national analyses, such as the Reuters Digital News Report, have updated this literature in light of social media: For example, Reuters reports from 2020 and 2022 find that younger people favor more “diverse” and “authentic” online sources, including scientists but also celebrities and environmental activists (Ejaz et al., Citation2022), whereas television has still been the most commonly used source for climate change news (Andı, Citation2020). Accordingly, Duvall (Citation2023, p. 411) notes that Greta Thunberg’s emergence as a “celebrity activist” was largely due to traditional mass media rather than digital media. Thus it was when local Swedish news media covered her first school strike that she became a focus of public attention and attracted followers; social media fueled the emerging School Strike movement only thereafter (Ryalls & Mazzarella, Citation2021).

Nevertheless, social media helped Greta Thunberg have an impact among a younger online generation, inspiring them to engage in climate change activism (Schmuck, Citation2021). Segerberg (Citation2017) has given an overview of how the Internet is used for such activism, and with Bennett, coined the term “connective action” whereby activists could “personalize” protest by participating online (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2012). In this way, Segerberg and Bennett sought to connect climate protests with the broader literature on social movements and update this for Internet-enabled protest (see also Hopke & Paris, Citation2021). Pearce et al. (Citation2019) subsequently reviewed research on climate change and social media. They found that research about Twitter (now X) dominated the number of published papers at that time, and that this research often used keywords and network analysis. As we shall see, the preponderance of papers about Twitter also applies to Thunberg. Yet in other ways, the literature has moved beyond the focus on protest and Twitter and to new forms of online activism on multiple platforms: A recent review of the literature on digital environmental activism (Baran & Stoltenberg, Citation2023) demonstrates, for example, that platforms like Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and WeChat have begun to attract more scholarly attention, albeit still less than Twitter.

But Thunberg cannot easily be pigeon-holed as only a protester. Abidin et al. (Citation2020) put Thunberg into the category of “ordinary people” celebrities, as opposed to other types of celebrities such as entrepreneurs (Bill Gates), animals (Knut the polar bear), or film star “ambassadors” (Emma Thompson). The authors suggest that the ordinary people trope of environmental celebrity owes their influence to social media. Thus they say that “Thunberg’s fame hinges upon her and her audiences’ use of social media” (Abidin et al., Citation2020, p. 400). While this may be true for some of her audience, it may not precisely capture three things that we will need to come back to repeatedly.

First, Thunberg’s visibility has not only been in social media but right across various media and genres at certain times, including news, entertainment, and fictional content on social networking sites and messenger platforms as well as in traditional mass media (Murphy, Citation2021). Furthermore, her impact has extended into policy documents, party manifestos, and election campaigns (Homoláč & Mrázková, Citation2021). It was thus Thunberg’s presence across the full breadth of media and information ecologies as well as the dialectical entanglement of different platforms within these ecologies that helped her dominate the global attention space and focus the public’s attention on climate change (Olesen, Citation2022).

Second, social media should not be conceived as a “self-driving vehicle” that lifted Thunberg to prominence and led to her becoming an “icon” (Wahlström & Uba, Citation2023). Ever since her first appearance in social media debates, she has used her own communication strategies and actively leveraged the affordances of social media platforms to bring across her message (Molder et al., Citation2022). Thus, her fame “hinges” not only upon social media, but also upon her agency (Fonseca & Castro, Citation2022).

Third, Thunberg did not only “benefit from [her] sustained public appearance” (Abidin et al., Citation2020, p. 390) in social media. As we shall see, her forceful stance has also drawn negative reactions from opponents, including ableism, ageism, misogyny, populism, and climate change skepticism (Mkono et al., Citation2020; Park et al., Citation2021; Yan et al., Citation2022).

This brief overview only scratched the surface of a growing literature, but it demonstrates that social media can both facilitate and challenge the visibility, reach, and success of environmental activism online. This dichotomy, which will be a major theme in our review, can be framed around a debate between Schäfer and North (Citation2019), who discuss opposing ideas about the impact of social media on climate change debates: This impact, they say, on the one hand makes policy discussions more difficult because social media allow different actors to voice their views with little sense of a focused, coherent, or shared debate. On the other hand, these many voices could also have a positive impact because the diversity of views can cause more public engagement and better policymaking.

Method

A purely quantitative review of research about Greta Thunberg is not helpful for two main reasons: First, the number of relevant studies is small. Second, the relevant literature is very heterogenous and fragmented, containing various themes, conceptual approaches, and methods, and focusing on very different contexts. This advises against using standardized metrics and coding schemes, as these would not be able to capture such diversity. Therefore, we conducted a systematic qualitative analysis of the literature, leveraging the benefits of an in-depth qualitative review of influential publications (Baran & Stoltenberg, Citation2023; Kim, Citation2023; Kumpu, Citation2022), but going beyond overview articles such as those by Abidin et al. (Citation2020), Schmuck (Citation2021), and Hopke and Paris (Citation2021), who provided worthwhile syntheses of celebrities, online influencers, and social movements in environmental communication.

Our analysis is based on 63 publications, which we identified as follows: In a first step, we searched the Web of Science, which is one of the most important multidisciplinary databases of scientific publications and has been used for several similar literature reviews (e.g. Comfort & Park, Citation2018; Mede, Citation2021). It contains mostly English-language publications from more than 21,000 peer-reviewed scholarly journals as well as books and preprints. We searched the Web of Science on 24 May 2023 with the following string:

TI = (Greta Thunberg) OR AB = (Greta Thunberg) OR AK = (Greta Thunberg) OR KP = (Greta Thunberg) OR SO = (Greta Thunberg)Footnote4

We excluded the document types “data set,” “meeting,” “news,” and “art and literature” and obtained 147 results. We reviewed the title, keywords, and abstract of all publications and skimmed the full publications if necessary to determine whether they were relevant for our analysis. We considered publications as relevant if they provided conceptual and/or empirical insights on the impact of Greta Thunberg on social media or related themes that would lend themselves to contextualize these insights (e.g. studies on digital climate activism). This applied to 54 publications.

In a second step, we complemented the Web of Science search with a search on Google Scholar, a search engine indexing a broad range of scholarly publications and gray literature. This was because Web of Science does not cover potentially insightful parts of the relevant literature, as it excludes journals with low citation counts and impact factors (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Citation2016). The Google Scholar search was done on 30 May 2023 and used the query “Greta Thunberg social media.” We inspected the first 150 search results (as results listed at 100 + positions were increasingly irrelevant for our review), found substantial overlap with the Web of Science results, but identified 27 additional publications discussing a “Greta effect” and considered 9 of them as relevant for our review. Most of these were reports, preprints, or articles from peer-reviewed journals not indexed in Web of Science.

Overall, we found 174 publications and considered 63 papers as relevant, 54 found through Web of Science and 9 found through Google Scholar. For our analysis, we read or skimmed them to determine their disciplinary background, conceptual approaches, and methods – and synthesize their key findings on Greta Thunberg’s impact on social media discourse about climate change.

Results and discussion

To answer the main question of our review – what do we know about the impact of Greta Thunberg on social media? – we take the following four steps: First, we disentangle the various forms of social communication by and about Thunberg, finding that the pertinent literature has long focused on single media and platforms but diversified recently. Second, we synthesize different approaches to gauge Thunberg’s impact on social media both quantitatively and qualitatively. Third, we consolidate two themes of the pertinent literature, centering on Thunberg-supportive discourse vs. backlash against her, and explain how key studies help us understand that these two forms of discourse are conditioned by media, geographical, and temporal contexts. Fourth, we identify gaps in the literature.

Thunberg across media and platforms

The first feature of the literature that deserves discussion is that there is a rich picture of the various forms of communication used by her and those engaging with her. Some publications analyze non-mediated communication, for example her speeches (Holmberg & Alvinius, Citation2020) or parliamentary debates (Schürmann, Citation2023). However, most studies examine mediated communication. Some of these investigate the message of Thunberg herself, for example her writings (H. Sjögren, Citation2020), or explore organizational communication: Rödder and Pavenstädt (Citation2023), for example, included websites of activist groups like Extinction Rebellion in an analysis demonstrating how these groups invoke “the science” and “the truth” when engaging with Thunberg’s claims.

Many analyses focus on intermediaries between Thunberg and the broader public, particularly on traditional mass media: They investigate a variety of channels, genres, and modalities, including news reporting, commentaries, and imagery in print media such as national newspapers, tabloids, and lifestyle magazines (e.g. Bergmann & Ossewaarde, Citation2020; Hayes & O’Neill, Citation2021; Kyyrö et al., Citation2023; Murphy, Citation2021; Ryalls & Mazzarella, Citation2021). Further analyses also include television (Homoláč & Mrázková, Citation2021), but these are rare – which is noteworthy considering that television is one of the most important channels for people to access information about climate change (Andı, Citation2020).

The in-depth analysis we provide in the remainder of this review, however, is concerned with online media – and this is what the most substantial portion of the literature on mediated discourse around Thunberg has been concerned with. Content, network, sentiment, and discourse analyses investigated online news (Neff & Jemielniak, Citation2022), blogs (Duvall, Citation2023), newsletters (Vandenhole et al., Citation2023), online partisan outlets (Vowles & Hultman, Citation2021), and, most notably, the key object of our review: social media. These analyses explore various forms of social communication, such as text and visual content, user comments, profile descriptions, and engagement metrics (e.g. Andersson, Citation2021; Kissas, Citation2022; Molder et al., Citation2022). Overall, they demonstrate how social media allow climate change communication to employ multiple different modes of communication. This is arguably thanks to their affordances, i.e. the potentials that platform design and functions provide to users to engage with Thunberg and each other, as we will elaborate later (Olesen, Citation2022).

We find that Twitter has received by far the most attention (e.g. Arce-García et al., Citation2023), which confirms the results of a recent review by Baran and Stoltenberg (Citation2023). However, a number of channels have been added in the last years, including Facebook (Elgesem & Brüggemann, Citation2023) and platforms tailored toward audiovisual content, especially YouTube (McCambridge, Citation2022) and Instagram (Molder et al., Citation2022). Some studies analyze less prominent platforms like Reddit (White, Citation2021), search engines like Google (Salerno, Citation2023), Bing (Heydel et al., Citation2019), or Baidu (Zhan & Gao, Citation2022), and local social networking sites like the Brazilian Universo Online (Da Silva, Citation2020). Further studies investigate specific online discussion forums: For example, Kyyrö et al. (Citation2023) analyze user discussions in the Finnish Hommaforum to show how backlash against Thunberg delegitimizes her climate activism as a religious cult.

To summarize, research on Greta Thunberg’s impact on social media has begun to diversify in terms of the platforms it analyzes. This may be partly because digital climate change communication has become increasingly fragmented across platforms and partly because scholarship has branched out into new terrain (see Baran & Stoltenberg, Citation2023).

Analyzing Thunberg’s impact on different social media is important as climate change debates are intertwined and interconnected across platforms (Olesen, Citation2022). Messages of Thunberg, her supporters, and her opponents also flow from social media into traditional news reporting and parliamentary debates, for example – spreading across the full spectrum of climate change discourse (Homoláč & Mrázková, Citation2021). In turn, social media users may pick up arguments discussed outside the online world (Rödder & Pavenstädt, Citation2023). This dialectic demonstrates that Thunberg’s impact on social media must be situated within the larger setting of hybrid media environments, where the messages, modes, and logics of both traditional and digital media interact and converge (Chadwick, Citation2017). Assessing the “Greta effect” can therefore not be achieved by focusing on single platforms but requires scholars to consider the networked nature of hybrid media ecologies.

Gauging Thunberg’s online impact

A number of studies try to quantify the impact of Thunberg on social media. For example, large-scale content analyses, many of which use automated methods, show that she received a great deal of public attention on major social networking sites including Twitter and Facebook – with ten thousands of posts and user reactions by her followers, her opponents, and other stakeholders like politicians and news media (e.g. Arce-García et al., Citation2023; Chen et al., Citation2023; Park et al., Citation2021). Yet many studies examine the “Greta effect” with qualitative methods, such as critical discourse analysis of far-right media discourse about Thunberg (Vowles & Hultman, Citation2021). These studies often gauge her impact in other ways: For example, they label her as an “environmental hero” (Moriarty, Citation2021) or “ecological wunderkind” (O. Sjögren, Citation2022), conceptualize her as an “eco-celebrity” (Murphy, Citation2021), consider her a “climate influencer” (Ballestar et al., Citation2022), or describe her as the “truth-teller” of the climate change movement (Nordensvard & Ketola, Citation2022). Wahlström and Uba (Citation2023), for example, conceive her as a “role model” for young women, as she motivated further female climate activists, such as Germany’s Luisa Neubauer or Uganda’s Vanessa Nakate, to challenge patriarchal hegemonies despite online sexual harassment and “mediated misogyny” (Keller, Citation2021, p. 683). While these studies use valorizing labels to capture Thunberg’s impact, some authors also discuss dismissive diagnoses that describe her as promoting “unrealistic” and “epistemically naïve” claims (Mansikka-aho et al., Citation2023), being a “passive victim” (Olesen, Citation2022, p. 1335), and assuming a simplistic Manichean worldview similar to populists (Zulianello & Ceccobelli, Citation2020).

These analyses show the difficulty of pigeon-holing Thunberg as a figure, since she embodies a number of roles in climate change activism. Overall, we find that Thunberg is more than a “talking head” or “token activist” who was “lifted to fame” by social media. She has assumed agency, actively – and often strategically – drawing on social media to market herself, raise awareness for climate change, and emotionalize the issue of climate change (Fonseca & Castro, Citation2022; Molder et al., Citation2022; Olesen, Citation2022). Hence she has been able to have unique appeal to social media publics, which is unmatched by German FFF organizer Luisa Neubauer (Fernandez-Prados et al., Citation2021), David Attenborough (O. Sjögren, Citation2022), Bill Gates (Ballestar et al., Citation2022), and other figures of the climate change movement. Some authors thus compare her to leaders of previous social movements, such as Martin Luther King Jr., arguing that both Thunberg and King represent charismatic moral authorities (Nässén & Rambaree, Citation2021). Like King, Thunberg had drawn a lot of enemies – albeit hers have been less organized in dedicated political committees and extra-legal groups and have not engaged in such drastic attacks as in King’s case. Yet in contrast to King, Thunberg-opposing discourse must also be situated within the contemporary hybrid media ecology including social media, which did not exist at the time of the Civil Rights Movement – and allowed novel forms of backlash, as we will elaborate in the following.

A twofold effect: Thunberg supporters and enemies on social media

The literature on the “Greta effect” on social media can not only be organized along media channels and platforms. Another basic division is between studies that seek to show how she energized support as against those that detail how she provoked backlash against her among enemies. The conceptual approaches and disciplinary angles of these studies can be consolidated into overlapping themes, of which the five most prominent include studies on cognition and affect, social movements and leadership, communication, traits and discrimination, and ideology. provides a heuristic overview of these themes, mentions the most pertinent approaches within these themes, and lists exemplary studies.

Table 1. Overview of the most prominent conceptual themes in the literature.

Thunberg-supportive dynamics

Studies centering on Thunberg-supportive social media dynamics elucidate how online discourse about her and her message promotes mobilization of the climate change movement, stimulates collective identity formation, and strengthens her position as an influential climate activist. For example, Sorce’s (Citation2022, p. 25) qualitative interview study with FFF protesters finds that social media posts of Thunberg serve as a “central discursive driver” that allows local protest groups to anchor their actions via a common reference point and thus build a collective identity. In a similar vein, Molder et al. (Citation2022) show that Thunberg’s Instagram posts seek to galvanize collective action by containing call-to-action claims, depicting masses of like-minded protesters, and using pronouns like “we” and “us” that invoke a sense of collective agency.

Survey studies like those of Sabherwal et al. (Citation2021), which can be placed in the “cognition and affect” theme (see ), find that individuals’ familiarity with Thunberg and her messaging is associated with stronger collective efficacy beliefs. This suggests that collective identity framing can be conducive to motivate people to engage in climate action. Accordingly, multiple studies relate the “Greta effect” to social movements theory, concepts like connective action, and phenomena like “hashtag activism” (Boulianne et al., Citation2020, p. 210; Della Porta & Portos, Citation2023; Olesen, Citation2022; Svensson & Wahlström, Citation2023; see also Hopke & Paris, Citation2021; see ). Works originating from organizational communication and advertising research, in contrast, describe how Thunberg leveraged the potentials of social media to mobilize her supporters against the backdrop of marketing theories and categorize her as a social media influencer (e.g. Ballestar et al., Citation2022). These works, alongside further studies scrutinizing narration and storytelling, for example (Nordensvard & Ketola, Citation2022), can be grouped into the “communication” theme (see ).

Scholarship on Thunberg-supportive social media discourse also has a personalized dimension: Several studies have not only assessed the significance of social media for Thunberg, but also the significance of her traits for the success of her social media message (see ). They indicate that (social) media portrayals of her gender, young age, whiteness, and socio-economic position as an ordinary middle-class schoolgirl showcase characteristics that the “climate generation” can easily identify with and thus help Thunberg raise awareness for her cause (Hayes & O’Neill, Citation2021; Ryalls & Mazzarella, Citation2021; Telford, Citation2023; see also Nässén & Rambaree, Citation2021). Such “identity-based mobilization” (Sorce, Citation2022, p. 19) is demonstrated in two Instagram analyses by Kissas (Citation2022) and Molder et al. (Citation2022), for example. They find that social media communication by and about Thunberg often emphasizes her girlhood so as to signal her “moral purity” and valorizes her young age so as to authenticate her concerns about climate change threatening children’s futures (Kissas, Citation2022; Molder et al., Citation2022). The social media ecology of the “Greta effect” has therefore, as Olesen (Citation2022) shows, turned her weaknesses into strengths – both visually (e.g. through cartoons depicting her as Pippi Longstocking) and in the form of text (e.g. through the phrase “No one is to too small to make a difference”). Keller (Citation2021) thus suggests to conceptualize the “Greta effect” as an instance of “mediated transnational girlhood,” which “operates as part of twenty-first century media and celebrity culture” (Keller, Citation2021, p. 683). This connects to Duvall (Citation2023), who elucidates how the uprising of a young girl like Thunberg against old conservative men has fueled her becoming a celebrity activist (Duvall, Citation2023). Yet while Thunberg may be “employed as a stand-in for Indigenous women and girls” (Keller, Citation2021, p. 684) and serve as a role model for young women (Wahlström & Uba, Citation2023), she is still rarely compared to other female activists like #MeToo initiator Tarana Burke or suffragette movement leader Emmeline Pankhurst. One reason for this may be that Thunberg’s “exceptionalism” does not only derive from her feminism, but also from her emancipation from an ordinary school student to a world-famous climate advocate (Abidin et al., Citation2020) and can also be attributed to her medical condition, as Ryalls and Mazzarella (Citation2021) point out. Their textual analysis indicates that overcoming her autism diagnosis has been perceived as her “superpower” (Citation2021, p. 438). Thunberg herself has in fact mentioned on Twitter that her Asperger’s is her “superpower,” potentially in an effort to preemptively refute ableist attacks (Skafle et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, social media discourse often frames Thunberg as a “hero” (Jung et al., Citation2020; Mkono et al., Citation2020; see also O. Sjögren, Citation2022).

Thunberg-opposing dynamics

However, the heroization and celebrification of Thunberg has been paralleled by manifold backlash against her (Duvall, Citation2023). This has been analyzed by a second strand of literature that focuses on Thunberg-opposing social media dynamics. We find that this literature has analyzed four main dimensions of these dynamics: the content, the modes of communication, the senders, and the underlying rationales of backlash discourses.

First, studies focusing on the content of social media backlash against Thunberg and the climate movement identify a variety of negative sentiments, which are often generally referred to as hate speech – ranging from incivility, impoliteness, and sarcasm to sexism, misogyny, and ageism, as well as ableism related to her Asperger diagnosis (e.g. Anderson & Huntington, Citation2017; Andersson, Citation2021; White, Citation2021). Park et al. (Citation2021), for example, find that more than 40% of the comments below the eleven most-watched YouTube videos about Thunberg contain name-calling, aspersion, lying, vulgarity, or pejorative terms. Automated analyses show that similar sentiments also circulate on Twitter – particularly during and after the 2019 UN Climate Change Conference COP25 (Arce-García et al., Citation2023; Jung et al., Citation2020). Further studies go beyond hate speech against Thunberg and look at how she is also targeted by mis- and disinformation (Dave et al., Citation2020).

Second, the literature demonstrates how Thunberg-opposing social media discourse uses different forms of expression. The different forms of backlash mentioned above are often articulated in the form of text, e.g. in Facebook, YouTube, or Twitter comments (Elgesem & Brüggemann, Citation2023; McCambridge, Citation2022; Olesen, Citation2022). However, they may also use visuals which circulate on platforms like Instagram and Reddit: For example, White’s (Citation2021) study reveals how memes use pop culture references to movies like Lord of the Rings, for example, to ridicule Thunberg as a “climate goblin” (p. 405). Further studies adopt more holistic perspectives and consider online arguments about her in terms of discursive strategies and dynamics (Homoláč & Mrázková, Citation2021; Olesen, Citation2022).

Third, studies have sought to disentangle the different senders of online backlash against Thunberg: Many illustrate how she has frequently been attacked by politicians like Donald Trump (Jung et al., Citation2020; Murphy, Citation2021; Nordensvard & Ketola, Citation2022) or political parties like the German AfD (Elgesem & Brüggemann, Citation2023). Others show that she has also been a target of online right-wing media, for example in Sweden (Vowles & Hultman, Citation2021) or Finland (Kyyrö et al., Citation2023). Importantly, politically motivated backlash dynamics are often perpetuated by social media users: The Twitter analysis of Arce-García et al. (Citation2023), for example, finds that while posts by opinion leaders like Trump received much attention during the COP25 conference, and that early discourse phases were driven by people sympathizing with the Spanish far-right and English-speaking Thunberg critics. Interestingly, their results suggest that about a quarter of backlash may have come from automated accounts (Arce-García et al., Citation2023). Further sources of backlash against Thunberg are industry actors, for example travel and tourism companies who target Thunberg’s anti-flying campaign (Mkono et al., Citation2020).

Fourth, a substantial part of the backlash literature has scrutinized the underlying rationales of criticism, hostility, and attacks against Thunberg. They identify motives such as concerns for economic recession due to Thunberg’s advocacy for carbon taxes (Holmberg & Alvinius, Citation2020), threats to masculinity and patriarchy due to her calls for female empowerment (Park et al., Citation2021), erosion of epistemic standards due to her “populist truth-telling” (Nordensvard & Ketola, Citation2022, p. 867), the emergence of a “climate religion” that allegedly deceives the public (Kyyrö et al., Citation2023), and loss of quality of life and individual freedom due to her claims about avoiding meat consumption and CO2 intensive transportation (White, Citation2021). Some papers see her role more broadly as a Swedish foreign meddling in the domestic affairs of other countries (e.g. Huan & Huan, Citation2022 for China; Sabherwal et al., Citation2022 for India). Interestingly, climate skepticism, which might be expected to feature prominently in research about attacks on Thunberg, is in fact a rare theme (White, Citation2021), even though in research about climate change communication more broadly, this is of course a central topic. Overall, many studies scrutinizing the rationales of backlash against Thunberg and her message refer to concepts like populism, nationalism, technocracy, and religious worldviews and can thus be consolidated within a “ideology” theme (see ).

Some studies juxtapose Thunberg-supportive and Thunberg-opposing social media discourse: They show how Thunberg aligns with certain political orientations such that she has support among some groups and a polarizing effect among others (in Sweden, Germany, and the UK: Elgesem & Brüggemann, Citation2023). Or they document how her message is politicized by some even when it is supported by the majority (Jung et al., Citation2020). These studies clearly demonstrate the twofoldness of the “Greta effect” on social media.

Gaps in the literature

On the basis of this review, we can now highlight several strengths in the literature. One is that several studies compare online vs. offline media, online media vs. political speech/debate, and journalistic media vs. social media discourse (e.g. Neff & Jemielniak, Citation2022). Some studies do this by charting the spillover from news media to social media commentary (e.g. Mkono et al., Citation2020). This is useful for assessing social media dynamics against the backdrop of the larger hybrid media environment (Chadwick, Citation2017). Moving beyond earlier studies of climate change and Twitter, there are many studies of visual communication, e.g. press photos, online memes, and Instagram images (e.g. White, Citation2021). Thus the recent literature seems to be influenced by the “visual turn” of online media research (Goransson & Fagerholm, Citation2018). Another strength is that a number of studies look at a temporal dimension which traces the emergence and sustainability of Thunberg’s success (e.g. Hayes & O’Neill, Citation2021), though there are as yet no studies of how her influence has diminished (but see Rauchfleisch et al., Citation2023). Moreover, there are several case studies about specific events, e.g. COP25 summits, which are useful for gauging how specific events benefit Thunberg’s impact. Another worthwhile characteristic of the literature is the multitude of conceptual approaches and frameworks, which stems from the variety of disciplines involved – sociology, political science, communication studies, psychology, and more – and allows a triangulating, holistic perspective on the “Greta effect.” That said, there is little interdisciplinary research integrating concepts and epistemological angles from different fields (but see Fonseca & Castro, Citation2022; Ryalls & Mazzarella, Citation2021).

This brings us to important blind spots of the literature: For example, organizational, institutional, and corporate communication has barely been analyzed. Second, there are few multilingual analyses, despite the global nature of the “Greta effect.” Third, we did not find research on private or semi-public communication on messaging services like Telegram or on “dark platforms,” i.e. alternative, sometimes exclusive and secretive online platforms like Gab, 4chan, 8kun, Parler, etc. (Zeng & Schäfer, Citation2021), even if there is presumably much backlash communication on these platforms (see Kyyrö et al., Citation2023). Fourth, although many studies set out to measure the impact of the “Greta Effect,” only a small portion of the literature actually investigates the effects of social media communication on people (as opposed to the effects of Thunberg on social media communication). That is, there is a dearth of research on uses, reception, and effects among social media audiences – though there are single experiments (e.g. Farinha & Rosa, Citation2022), surveys (e.g. Sabherwal et al., Citation2021), and qualitative interviews (e.g. Sorce, Citation2022) that look at the “demand-side” of the “Greta effect,” i.e. at Thunberg’s impact on the attitudes of social media users. Finally, there are no studies which attempt to evaluate the “Greta effect” holistically, investigate how it has faded, and ask whether it is still a phenomenon that can be learnt from – a task to which we now turn.

Conclusion

There has been much scholarship on the “Greta effect” on social media. However, it has spread across various disciplines and thus fails to provide a bigger picture of Thunberg’s impact on digital climate change communication. In this paper, we provided such a picture with a systematic, qualitative review of the pertinent literature on the “Greta effect,” focusing on 63 key studies. It is the first study to synthesize and consolidate the fragmented literature on how Greta Thunberg has shaped social media discourse about climate change.

One of the key insights from our review is that social media have had a twofold effect on climate communication: On the one hand, they help iconic figures like Thunberg to amplify her message, extend its reach across various platforms, and mobilize her supporters. On the other hand, social media allow her enemies to stylize her as a hate figure and personalize the issue of climate change. This, in turn, may help climate change sceptics to spread their claims online – which may then be picked up by traditional news media. Yet backlash against Thunberg still seems to feature more prominently on social media than in journalistic media, whereas Thunberg herself often garners attention in news reporting. This is an asymmetry in climate science communication. Our findings thus extend the debate by Schäfer and North (Citation2019): Social media do not just give added voices to the climate change debate, nor do they mainly add confusion to the debate. Rather, Thunberg’s supporters and opponents personalize climate change, which shifts the debate away from science and policy to Thunberg-centered celebrification and ad-hominem attacks against her (Ryalls & Mazzarella, Citation2021). This bears the risk of diverting attention from the issue of climate change itself, and may impede constructive discourse about solutions to its consequences. This argument complicates the opposing views put forward by Schäfer and North: The advantage of social media is asymmetric as between activists and those who oppose them because activists seek to influence gatekeepers whereas opponents seek to circumvent them. The larger backdrop of this asymmetry is the backlash against social media, sometimes called “techlash,” which highlights polarization, misinformation, and other social ills that are attributed to social media platforms, which can be set against the positive role that social media can play – as when Thunberg’s online activism is an example of how, outside the role of traditional media, “ordinary people” activists can draw attention to social issues (Abidin et al., Citation2020).

We have seen that existing work on the “Greta effect” provides a rich and multi-facetted picture. This needs now to be put into the context of climate change communication. “Greta” has had various “effects,” among supporters and enemies alike. On their own, the individual studies we reviewed do not give a clear sense of why she personally had such an outsize impact, including calling forth a backlash. But each study demonstrates that the heroization of Thunberg and attacks against her (Duvall, Citation2023) increase attention to climate change. Accordingly, Thunberg’s online activism is an example of how, outside traditional media, she can raise awareness for climate change and so hold both news media and politicians to account for what is perceived to be their neglect of the issue: As Dutton (Citation2023, p. 20) argues, the Internet acts as a “Fifth Estate,” which places Thunberg among whistleblowers, citizen journalists, and protesters who make strategic use of communication tools.

The main “effect” of Thunberg can therefore not be reduced to individual platforms or isolated events. Rather, we have to distinguish a number of different “Greta effects.” In the early phase, she was catapulted into fame by news coverage, was then discussed in social media, and soon afterwards strategically used social media herself to mobilize supporters. This highlights how the different platforms within hybrid media ecologies interacted during the emergence of the climate movement in a specific sequence, with traditional mass media serving as triggers of attention, and social media being tools to coordinate activism and amplify Thunberg’s message, which then flowed back into journalistic media. Yet this sequential, cross-media dialectic of “Greta effects” did not only occur in the early phase: shows that online attention for climate change peaked shortly after news coverage spikes even in more recent years (e.g. shortly after COP27). Further, gauging the “Greta effect” must distinguish between the specific new forms of climate activism she initiated – encouraging no-fly behavior, for example – and the more general way in which Thunberg gave a renewed impetus to the climate change movement. And yet another distinction is between how she has drawn attention to climate science – as against how she has mobilized political protest; the two are connected, but they are also sometimes separate in the media.

These “effects” would need to be integrated into an overall model of the roles of different media, when they were effective at different points in time, and what their effects were on media agendas and offline mobilization. We thus encourage future environmental communication research to propose such a model and triangulate different methods and data sources to test it empirically. This would give a more holistic perspective on the exceptionalism of the “Greta effect” within and beyond social media – and on the exceptionalism of Thunberg herself: She considered her autism as a “superpower” (Skafle et al., Citation2021), but similarly distinctive is her young age. Her youth put to shame an older and more powerful generation, and challenged hegemonic structures including patriarchy and capitalism (Keller, Citation2021). It is also worth stressing the “effect” she has among people of a similar age: University students have traditionally been leading a number of protests – we can think here of the protests against the Vietnam War. However, Thunberg’s ability to mobilize fellow school age children, for whom she has been a relatable role model (thanks to her age) but also an idol (because of her disability activism and feminism), has been an innovation of hers. But age also caused backlash among those who said children should be in school and are not knowledgeable enough. This is special to the “Greta effect” and requires further scrutiny by future scholarship.

Finally, we can add that many “Greta effects” have now faded: Thunberg still takes part in climate protests, but she continues to be one figure among several others in the climate change movement. She remains well-recognized, but climate activism seems to lack the central thrust that she gave it. This also applies to the backlash against her, where there are now other ways that those who oppose climate change action can vent their anger. Thus, since then and now, media attention to the issue has once again become steady and fragmentary, devoted to various extreme weather events, international high-level conferences, scientists’ warnings, and protests – but largely without a coherent escalation of focused attention.

It is difficult to know if such an upheaval of attention will take place again. As mentioned, research on social movements tells us much about how attention is generated, but we know less about how the attention to contentious movements declines (Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015, p. 229). Typically, contention becomes institutionalized and may make gains or achieve its aims. But there is a difference between climate change activism and other social movements which is not to do with social media, but which is that contention over climate change cannot achieve its aims once certain milestones are achieved, unlike, say, with civil rights or gay marriage or abortion. Future research on climate change and social media may need to theorize how online ripples can be turned into not just one wave, as they did with Thunberg, but a sustained flood – of the positive sort.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two very helpful reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Indicated by the amount of global newspaper reporting on climate change (Boykoff et al., Citation2023).

2 Indicated by the global Google search volume for “climate change” (Google Trends, Citation2023).

3 Indicated by the percentage of people in 46 countries worldwide agreeing that climate change is a “major threat” or “very serious problem” (Pew Research Center, Citation2023).

4 TI = title; AB = abstract; AK = author keywords; KP = Web of Science keywords; SO = publication or source title. The search is reproducible with the following URL: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/summary/61f79883-b821-4fc8-85d2-ae80c3e53b45-8cb5eaea/date-descending/1.

References

- Abidin, C., Brockington, D., Goodman, M., Mostafanezhad, M., & Richey, L. (2020). The tropes of celebrity environmentalism. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45(1), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-081703

- Agius, C., Rosamond, A., & Kinnvall, C. (2020). Populism, ontological insecurity and gendered nationalism. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 21(4), 432–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2020.1851871

- Anderson, A., & Huntington, H. (2017). Social media, science, and attack discourse. Science Communication, 39(5), 598–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547017735113

- Andersson, M. (2021). The climate of climate change: Impoliteness as a hallmark of homophily in YouTube comment threads on Greta Thunberg’s environmental activism. Journal of Pragmatics, 178, 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.03.003

- Andı, S. (2020). How people access news about climate change. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/how-people-access-news-about-climate-change/

- Arce-García, S., Díaz-Campo, J., & Cambronero-Saiz, B. (2023). Online hate speech and emotions on Twitter: A case study of Greta Thunberg at the UN Climate Change Conference COP25 in 2019. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-023-01052-5

- Baiardi, D., & Morana, C. (2021). Climate change awareness: Empirical evidence for the European Union. Energy Economics, 96, Article 105163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105163

- Ballestar, M., Martín-Llaguno, M., & Sainz, J. (2022). An artificial intelligence analysis of climate-change influencers’ marketing on Twitter. Psychology and Marketing, 39(12), 2273–2283. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21735

- Baran, Z., & Stoltenberg, D. (2023). Tracing the emergent field of digital environmental and climate activism research: A mixed-methods systematic literature review. Environmental Communication. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2212137

- Bennett, W. Lance, & Segerberg, Alexandra. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

- Bergmann, Z., & Ossewaarde, R. (2020). Youth climate activists meet environmental governance: Ageist depictions of the FFF movement and Greta Thunberg in German newspaper coverage. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 15(3), 267–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2020.1745211

- Bogert, J. M., Buczny, J., Harvey, J., & Ellers, J. (2023). The effect of trust in science and media use on public belief in anthropogenic climate change: A meta-analysis. Environmental Communication. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2280749

- Boulianne, S., Lalancette, M., & Ilkiw, D. (2020). “School strike 4 climate”: Social media and the international youth protest on climate change. Media and Communication, 8(2), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.2768

- Boykoff, M., Daly, M., Reyes, R., McAllister, L., McNatt, M., Nacu-Schmidt, A., Oonk, D., & Pearman, O. (2023). World newspaper coverage of climate change or global warming, 2004–2023. https://doi.org/10.25810/4c3b-b819

- Boykoff, M. T. (2011). Who speaks for the climate? Making sense of media reporting on climate change. Cambridge University Press.

- Brünker, F., Deitelhoff, F., & Mirbabaie, M. (2019). Collective identity formation on Instagram – investigating the social movement Fridays for Future. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1912.05123

- Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system: Politics and power (2nd ed., Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190696726.001.0001

- Chen, K., Molder, A. L., Duan, Z., Boulianne, S., Eckart, C., Mallari, P., & Yang, D. (2023). How climate movement actors and news media frame climate change and strike. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 28(2), 384–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612221106405

- Comfort, S., & Park, Y. (2018). On the field of environmental communication: A systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature. Environmental Communication, 12(7), 862–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1514315

- Cornelio, G. S., Martorell, S., & Ardèvol, E. (2024). “It is the voice of the environment that speaks”, digital activism as an emergent form of environmental communication. Environmental Communication. Online advance publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2296850.

- Da Silva, F. (2020). Violência em rede: Discursos sobre Greta Thunberg em comentários on-line. Revista De Estudos Da Linguagem, 28(4), 1551. https://doi.org/10.17851/2237-2083.28.4.1551-1579

- Dave, A., Boardman Ndulue, E., Schwartz-Henderson, L., & Weiner, E. (2020, July 22). Targeting Greta Thunberg: A case study in online mis/disinformation. German Marshall Fund. https://www.gmfus.org/news/targeting-greta-thunberg-case-study-online-misdisinformation

- Della Porta, D., & Portos, M. (2023). Rich kids of Europe? Social basis and strategic choices in the climate activism of Fridays for Future. Italian Political Science Review, 53(1), 24–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.54

- Dutton, W. (2023). The fifth estate: The power shift of the digital age. Oxford University Press.

- Duvall, S. (2023). Becoming celebrity girl activists: The cultural politics and celebrification of Emma González, Marley Dias, and Greta Thunberg. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 47(4), 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/01968599221120057

- Ejaz, W., Mukherjee, M., Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. (2022). How we follow climate change: Climate news use and attitudes in eight countries. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/how-we-follow-climate-change-climate-news-use-and-attitudes-eight-countries

- Elgesem, D., & Brüggemann, M. (2023). Polarisation or just differences in opinion: How and why Facebook users disagree about Greta Thunberg. European Journal of Communication, 38(3), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231221116179

- Farinha, C., & Rosa, M. (2022). Just chill! An experimental approach to stereotypical attributions regarding young activists. Social Sciences, 11(10), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100427

- Fernandez-Prados, J., Lozano-Diaz, A., Cuenca-Piqueras, C., & Gonzalez-Moreno, M. (2021). Analysis of teenage cyberactivists on Twitter and Instagram around the world. In 2021 9th ICIET (pp. 476–479). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIET51873.2021.9419619

- Fonseca, A., & Castro, P. (2022). Thunberg’s way in the climate debate: Making sense of climate action and actors, constructing environmental citizenship. Environmental Communication, 16(4), 535–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2054842

- Google Trends. (2023, July 3). “Climate change”: Interest over time. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date = all&q = %2Fm%2F0d063v

- Goransson, K., & Fagerholm, A.-S. (2018). Towards visual strategic communications. Journal of Communication Management, 22(1), 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-12-2016-0098

- Hase, V., Mahl, D., Schäfer, M. S., & Keller, T. (2021). Climate change in news media across the globe: An automated analysis of issue attention and themes in climate change coverage in 10 countries (2006–2018). Global Environmental Change, 70, Article 102353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102353

- Haugseth, J., & Smeplass, E. (2022). The Greta Thunberg effect: A study of Norwegian youth’s reflexivity on climate change. Sociology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385221122416

- Hayes, S., & O’Neill, S. (2021). The Greta effect: Visualising climate protest in UK media and the Getty images collections. Global Environmental Change, 71, Article 102392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102392

- Heydel, Z., Ferreira, V., Zak, A., Olthof, E., & Heydel, Z. (2019, October 24). Search engine comparison for three controversial people: Greta Thunberg, Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. http://mastersofmedia.hum.uva.nl/blog/2019/10/24/search-engine-comparison-for-three-controversial-people-greta-thunberg-donald-trump-and-boris-johnson/.

- Holmberg, A., & Alvinius, A. (2020). Children’s protest in relation to the climate emergency. Childhood, 27(1), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568219879970

- Homoláč, J., & Mrázková, K. (2021). A skirmish on the Czech political scene: The glocalization of Greta Thunberg’s UN Climate Action Summit speech in the Czech media. Discourse, Context & Media, 44, Article 100547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100547

- Hopke, J., & Paris, L. (2021). Environmental social movements and social media. In B. Takahashi, J. Metag, J. Thaker, & S. E. Comfort (Eds.), The handbook of international trends in environmental communication (pp. 357–372). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367275204-26

- Huan, Q., & Huan, X. (2022). From the earth’s limits to Greta Thunberg: The effects of environmental crisis metaphors in China. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 81(2), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12455

- Jung, J., Petkanic, P., Nan, D., & Kim, J. (2020). When a girl awakened the world: A user and social message analysis of Greta Thunberg. Sustainability, 12(7), 2707. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072707

- Keller, J. (2021). “This is oil country”: Mediated transnational girlhood, Greta Thunberg, and patriarchal petrocultures. Feminist Media Studies, 21(4), 682–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1919729

- Kim, K. (2023). A review of CLT-based empirical research on climate change communication from 2010 to 2021. Environmental Communication, 17(7), 844–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2259625

- Kissas, A. (2022). Populist everyday politics in the (mediatized) age of social media: The case of Instagram celebrity advocacy. New Media & Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221092006

- Kumpu, V. (2022). What is public engagement and how does it help to address climate change? A review of climate communication research. Environmental Communication, 16(3), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2055601

- Kyyrö, J., Äystö, T., & Hjelm, T. (2023). “The cult of Greta Thunberg”: De-legitimating climate activism with “religion”. Critical Research on Religion. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503032231174208

- Mansikka-aho, A., Varpanen, J., Lahikainen, L., & Pulkki, J. (2023). Exploring the moral exemplarity of Greta Thunberg. Journal of Moral Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2023.2248404

- McCambridge, L. (2022). Describing the voice of online bullying: An analysis of stance and voice type in YouTube comments. Discourse, Context & Media, 45, Article 100552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100552

- Mede, N. (2021). Charakteristika der Forschung zu Wirkungen digitaler Wissenschaftskommunikation: Ein Systematic Review der Fachliteratur. In J.-H. Passoth, M. Tatari, & N. G. Mede (Eds.), Wissenschaftspolitik im Dialog: Vol. 17 (pp. 37–82). https://www.bbaw.de/files-bbaw/user_upload/publikationen/Broschuere-WiD_17_PDF-A1b.pdf#page = 39.

- Mkono, M., Hughes, K., & Echentille, S. (2020). Hero or villain? Responses to Greta Thunberg’s activism and the implications for travel and tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2081–2098. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1789157

- Molder, A., Lakind, A., Clemmons, Z., & Chen, K. (2022). Framing the global youth climate movement: A qualitative content analysis of Greta Thunberg’s moral, hopeful, and motivational framing on Instagram. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(3), 668–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211055691

- Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

- Moriarty, S. (2021). Modeling environmental heroes in literature for children: Stories of youth climate activist Greta Thunberg. The Lion and the Unicorn, 45(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.2021.0015. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/819554

- Murphy, P. (2021). Speaking for the youth, speaking for the planet: Greta Thunberg and the representational politics of eco-celebrity. Popular Communication, 19(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2021.1913493

- Nässén, N., & Rambaree, K. (2021). Greta Thunberg and the generation of moral authority: A systematic literature review on the characteristics of Thunberg’s leadership. Sustainability, 13(20), 11326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011326

- Neff, T., & Jemielniak, D. (2022). How do transnational public spheres emerge? Comparing news and social media networks during the Madrid climate talks. New Media & Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221081426

- Nordensvard, J., & Ketola, M. (2022). Populism as an act of storytelling: Analyzing the climate change narratives of Donald Trump and Greta Thunberg as populist truth-tellers. Environmental Politics, 31(5), 861–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1996818

- Olesen, T. (2022). Greta Thunberg’s iconicity: Performance and co-performance in the social media ecology. New Media & Society, 24(6), 1325–1342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820975416

- Park, C., Liu, Q., & Kaye, B. K. (2021). Analysis of ageism, sexism, and ableism in user comments on YouTube videos about climate activist Greta Thunberg. Social Media + Society, 7(3), 205630512110360. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211036059.

- Pearce, W., Niederer, S., Özkula, S., & Sánchez Querubín, N. (2019). The social media life of climate change: Platforms, publics, and future imaginaries. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 10(2), e569. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.569

- Pew Research Center. (2023). Pew global attitudes & trends question database: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research. https://ropercenter.cornell.edu/pewglobal/

- Rauchfleisch, A., Siegen, D., & Vogler, D. (2023). How Covid-19 displaced climate change: Mediated climate change activism and issue attention in the Swiss media and online sphere. Environmental Communication, 17(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.1990978

- Rödder, S., & Pavenstädt, C. (2023). “Unite behind the science!” Climate movements’ use of scientific evidence in narratives on socio-ecological futures. Science and Public Policy, 50(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scac046

- Ryalls, E., & Mazzarella, S. (2021). “Famous, beloved, reviled, respected, feared, celebrated”: Media construction of Greta Thunberg. Communication, Culture and Critique, 14(3), 438–453. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcab006

- Sabherwal, A., Ballew, M., van der Linden, S., Gustafson, A., Goldberg, M., Maibach, E., Kotcher, J., Swim, J. K., Rosenthal, S., & Leiserowitz, A. (2021). The Greta Thunberg effect: Familiarity with Greta Thunberg predicts intentions to engage in climate activism in the United States. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(4), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12737

- Sabherwal, A., Shreedhar, G., & van der Linden, S. (2022). Inoculating against threats to climate activists’ image: Intersectional environmentalism and the Indian farmers’ protest. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 3, Article 100051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cresp.2022.100051

- Salerno, F. (2023). The Greta Thunberg effect on climate equity: A worldwide Google Trend analysis. Sustainability, 15(7), 6233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076233

- Schäfer, M. S., & North, P. (2019). Are social media making constructive climate policymaking harder? In M. Hulme (Ed.), Contemporary climate change debates (pp. 222–235). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429446252-16

- Schmuck, D. (2021). Social media influencers and environmental communication. In B. Takahashi, J. Metag, J. Thaker, & S. E. Comfort (Eds.), The handbook of international trends in environmental communication (pp. 373–387). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367275204-27

- Schürmann, L. (2023). The impact of local protests on political elite communication: Evidence from Fridays for Future in Germany. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2023.2189729

- Segerberg, A. (2017). Online and social media campaigns for climate change engagement. In M. Brüggemann (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.398

- Sisco, M., Pianta, S., Weber, E., & Bosetti, V. (2021). Global climate marches sharply raise attention to climate change: Analysis of climate search behavior in 46 countries. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 75, Article 101596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101596

- Sjögren, H. (2020). Longing for the past: An analysis of discursive formations in the Greta Thunberg message. Culture Unbound, 12(3), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.vi0.1796

- Sjögren, O. (2022). Ecological wunderkind and heroic trollhunter: The celebrity saga of Greta Thunberg. Celebrity Studies, 14(4), 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2022.2095923

- Skafle, I., Gabarron, E., Dechsling, A., & Nordahl-Hansen, A. (2021). Online attitudes and information-seeking behavior on autism, Asperger syndrome, and Greta Thunberg. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094981

- Sorce, G. (2022). The “Greta Effect”: Networked mobilization and leader identification among Fridays for Future protesters. Media and Communication, 10(2), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i2.5060

- Svensson, A., & Wahlström, M. (2023). Climate change or what? Prognostic framing by Fridays for Future protesters. Social Movement Studies, 22(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2021.1988913

- Telford, A. (2023). A feminist geopolitics of bullying discourses? White innocence and figure-effects of bullying in climate politics. Gender, Place & Culture, 30(7), 1035–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2022.2065246

- Thaker, J. (2023). Cross-country analysis of the association between media coverage and exposure to climate news with awareness, risk perceptions, and protest participation intention in 110 countries. Environmental Communication. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2272299

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2015). Contentious politics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Vandenhole, K., Bauler, T., & Block, T. (2023). “How dare you!”: A conceptualization of the eco-shaming discourse in Belgium. Critical Policy Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2023.2200016

- Vowles, K., & Hultman, M. (2021). Dead white men vs. Greta Thunberg: Nationalism, misogyny, and climate change denial in Swedish far-right digital media. Australian Feminist Studies, 36(110), 414–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2022.2062669

- Wahlström, M., & Uba, K. (2023). Political icon and role model: Dimensions of the perceived “Greta effect” among climate activists as aspects of contemporary social movement leadership. Acta Sociologica. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00016993231204215

- Watts, J. (2019, April 23). The Greta Thunberg effect: At last, MPs focus on climate change. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/23/greta-thunberg

- White, M. (2021). Greta Thunberg is “giving a face” to climate activism: Confronting anti-feminist, anti-environmentalist, and ableist memes. Australian Feminist Studies, 36(110), 396–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2022.2062667

- Yan, P., Schroeder, R., & Stier, S. (2022). Is there a link between climate change scepticism and populism? An analysis of web tracking and survey data from Europe and the US. Information, Communication & Society, 25(10), 1400–1439. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1864005

- Zeng, J., & Schäfer, M. S. (2021). Conceptualizing “dark platforms”: COVID-19-related conspiracy theories on 8kun and Gab. Digital Journalism, 9(9), 1321–1343. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1938165

- Zhan, J., & Gao, H. (2022). Why climate change has been ignored: A Chinese perspective. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 81(2), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12456

- Zulianello, M., & Ceccobelli, D. (2020). Don’t call it climate populism: On Greta Thunberg’s technocratic ecocentrism. The Political Quarterly, 91(3), 623–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12858