ABSTRACT

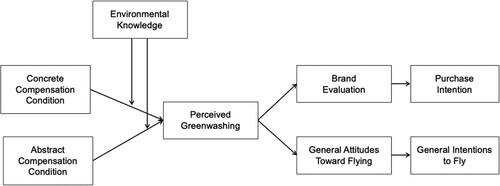

To respond to consumers’ rising concerns about environmental topics, airlines increasingly use green advertising. However, due to the environmental impact of flying, many green advertisements by airlines can be considered as “greenwashing” practices. In an experimental study with a quota-based sample (N = 329), we investigated the effects of two types of greenwashed advertisements for airlines: concrete compensation and abstract compensation (compared to a control condition). Following the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), we also explored the moderating role of environmental knowledge in the ability of consumers to perceive greenwashing in airline advertising. Results indicated that concrete compensation claims did not increase greenwashing perceptions compared to the control condition. However, abstract compensation claims did, which, via perceived greenwashing, were negatively associated with brand outcomes and assessments of flying. Environmental knowledge did not moderate these effects. Implications for research on greenwashing, as well as practical conclusions for environmental communication, are discussed.

A growing number of consumers favor airlines that signal engagement for environmentally sustainable practices over airlines that do not signal to care about the environment (e.g. Aviation Index, Citation2021). This is also reflected in the fact that recently, consumers perceive “good” environmental performances of flights as more important than short travel times or low flight prices (e.g. Alfaro & Chankov, Citation2022). However, since airlines are currently not able to offer flights that do not pollute the environment, “green” and “sustainable” airlines seem to be still an illusion, at least at this point in time (BEUC, Citation2023). Nevertheless, airlines have changed their marketing strategies, promoting “various environmental responsibility activities” (Han, Yu, & Kim, Citation2019, p. 1) and using supposedly green advertising claims (e.g. Mayer et al., Citation2012). They increasingly use advertising offering environmental compensation, “signaling consumers that the CO2 produced by flying can be compensated by other environmentally friendly measures” (Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023, p. 3).

While environmental compensation efforts are highlighted in these claims, neither information about their real environmental benefit nor about the environmental harm that is initially caused by flying is given (e.g. Polonsky et al., Citation2010). This could give consumers the misleading impression that airlines are sustainable and “change is happening, when in reality, it is not” because, with every flight, airlines still contribute Greenhouse Gas emissions to the atmosphere (BEUC, Citation2023; Harding-Rolls, Citation2022). Hence, compensation claims can be categorized as omission claims – a common form of greenwashing claims neglecting important information that consumers need to know to make an elaborate purchase decision (e.g. Kangun et al., Citation1991).

Prior research has shown that in false green claims, including outright lies, consumers tend to be able to perceive greenwashing, that is, the perception that companies present themselves, their products, brands, or services as more environmentally friendly than they actually are (e.g. Baum, Citation2012; Kangun et al., Citation1991). In other claims, such as vague claims that are overly ambiguous or executional greenwashing claims including pleasant nature imagery (e.g. Parguel et al., Citation2015), they seem to have difficulties detecting greenwashing, at least without environmental knowledge (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018). However, omission claims in the form of compensation claims have not been sufficiently investigated so far (e.g. Matthes, Citation2019; see generally for the selective omission of information, Chadwick & Stanyer, Citation2022). Although compensation claims can be seen as an especially persuasive advertising strategy by triggering consumers’ beliefs that environmental harm could be balanced out with environmentally friendly measures (e.g. compensatory green beliefs; Hope et al., Citation2018), they received far too little attention until now (e.g. Matthes, Citation2019). Moreover, little is known about consumers’ ability to perceive greenwashing in advertising that promotes inherently environmentally unfriendly products or services, such as airlines. Until yet, only two studies (see Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023; Neureiter, Stubenvoll, & Matthes, Citation2023) have investigated compensation claims and consumers’ greenwashing perceptions in the airline context. However, “one-shot studies” provide far too little evidence to draw conclusive conclusions (e.g. Kerr et al., Citation2016, p. 7). Further, while the study of Neureiter and Matthes (Citation2023) only touched upon outcomes that are important for companies, the current study focuses on typical advertising outcomes. Thus, based on information processing theories (e.g. ELM; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986), this study aims to establish robust, reliable, and valid insights into the effects of compensation claims on perceived greenwashing. Besides, we investigated consumers’ ability to recognize greenwashing and its consequences for airlines (e.g. Naderer & Opree, Citation2021). Thereby, this study offers some important implications for airlines on how to pursue environmental communication while avoiding greenwashing, as well as for consumer protection initiatives on how to empower consumers to detect greenwashing.

Types of greenwashing claims and their effects

Generally, greenwashing is characterized by a company’s behavior that is twofold (De Freitas Netto et al., Citation2020). In more detail, in order to present themselves as more environmentally friendly than they actually are, companies withhold the harmful environmental behavior of a product or service while they communicate the pro-environmental performance to consumers (e.g. Baum, Citation2012). Overall, greenwashing claims are defined as “unfair or deceptive” (FTC, Citation2012, p. 3), “misleading and unsubstantiated environmental claims” that create “the impression that a product or service is environmentally friendly or is less damaging to the environment than competing goods or services” (European Commission, Citation2014, p. 33).

Kangun et al. (Citation1991) identified three types of misleading green claims: (1) False claims, which are based on an outright lie; (2) Vague claims of which the claim’s meaning is unclear or very broad (e.g. “all-natural ingredients”); and (3) Omission claims that omit important information, for instance, by neglecting environmental downsides of a product or service. Another strategy used in green advertising includes the application of image-based emotional appeals and is referred to as executional greenwashing (e.g. Parguel et al., Citation2015). This strategy goes beyond fact-based appeals by including pleasant nature imagery (e.g. Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009). Conceptually, greenwashing claims and elements are not mutually conclusive. In advertising practice, there exist combinations of claim types, either of different claims with each other (Kangun et al., Citation1991) or with executional greenwashing (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018). For instance, a claim can be overly ambiguous and, at the same time, include lies (e.g. Kangun et al., Citation1991) or pleasant nature imagery of an unspoiled landscape (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018).

Previous content analyses in the context of green advertising have shown that the majority of the analyzed environmental advertisements can be classified as misleading rather than acceptable (e.g. Kangun et al., Citation1991; Kwon et al., Citation2024). Most of the analyzed supposedly green ads were at least characterized by a false, vague, or omission claim element rather than being acceptable, including no misleading claim elements. In contrast, Segev et al. (Citation2016) have reported more recently that less than half of the analyzed ads in print magazines and newspapers were categorized as greenwashing. However, all in all, prior research paints a consistent picture: Greenwashing is a phenomenon that will not disappear anytime soon and is especially used by companies promoting inherently environmentally harmful products, services, or processes (e.g. Atkinson & Kim, Citation2015; Baum, Citation2012; Leonidou et al., Citation2011).

A second stream of research focuses on consumers’ ability to detect greenwashing and the negative effects of these perceptions on consumers’ emotions, brand evaluations, and purchase intentions (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018). Generally, false claims are more easily detected by consumers as greenwashing compared to vague claims (Schmuck et al., Citation2018). Further, one single study that went beyond false and vague claims by also investigating omission claims found that consumers seem to have difficulties detecting greenwashing in claims neglecting important information (Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023). If advertisers go beyond textual claims and work with nature-evoking imagery, detecting them as misleading is even more challenging for consumers (e.g. Parguel et al., Citation2015). However, if greenwashing is detected, it results in negative emotions (e.g. Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023; Szabo & Webster, Citation2021) as well as negative ad and brand evaluations (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018). Further, it reduces consumers’ trust in the advertising company and is positively related to consumers’ confusion and risk perceptions of buying the advertised supposedly green products or services (e.g. Chen & Chang, Citation2013).

Green compensation claims in airline advertising

While airlines might genuinely make an effort to become more sustainable, they often advertise their services by using misleading environmental compensation claims promoting environmental measures to neutralize the environmental harm done by flying (e.g. Olk, Citation2021; Polonsky et al., Citation2010). Typically, compensation claims solely focus on the pro-environmental aspects of flying by stressing airlines’ engagement in environmental compensation measures. At the same time, they neglect information about the well-known harmful aspects of flying and the real environmental benefit of the proposed measures (i.e. how much emissions are really emitted and compensated; e.g. Benady, Citation2007). However, since consumers need this information to assess how much emissions the compensation measures actually neutralize, compensation claims can be categorized as omission claims, neglecting important information (e.g. Kangun et al., Citation1991; Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023).

Conceptually, compensation claims can be differentiated from vague claims that include broad or ambiguous messages without giving a reason on what basis the claim is made (e.g. Kangun et al., Citation1991). In contrast, by suggesting a specific environmental measure, compensation claims include a reason why the advertised company, product, or service is supposedly green. Moreover, compensation claims do not include an outright lie such as false claims. In fact, although it is not certain if the promoted compensation measures have an environmental benefit (BEUC, Citation2023), generally, they might take place such as described in the ads. Thus, the claim might not be factually wrong per se. To conclude, compensation claims are neither overly ambiguous nor factually wrong. However, instead, they omit important information by not disclosing the environmental harm of flying and the real environmental benefit of the proposed environmental measures.

In accordance with Neureiter and Matthes (Citation2023) and Neureiter et al. (Citation2023), in this paper, we distinguish two types of green compensation claims: Concrete and abstract. Both types are conceptualized as omission claims (e.g. Kangun et al., Citation1991) and, therefore, do not differ with regard to how content is communicated. However, they differ regarding the content itself – the environmental compensation measures that are conveyed by the messages and how temporal and spatial distant they are from consumers’ experience. According to the theory of psychological distance (Liberman et al., Citation2007), temporal and spatial distance leads to abstract mental representations, which makes the proposed measures seem intangible to consumers. In contrast, spatial and temporal proximity increases concrete mental representations, making the offered measures appear tangible to consumers (Liberman et al., Citation2007). Thus, “concrete” and “abstract” do not refer to the message concreteness of the claims but instead to the tangibleness of the compensation measures promoted in the airline ads. Following this logic, concrete compensation claims are characterized by promoting environmentally friendly measures that are happening at a foreseeable point of time (i.e. during the flight) and in nearby locations (i.e. on board of the aircraft). For instance, various airlines concentrate on sustainable product use on board, such as plastic recycling, upcycling, or avoiding plastic on board (i.e. compostable cutlery on board; HiFly, Citation2019; Virgin Australia Airlines, Citation2019). In contrast, abstract compensation claims are offering pro-environmental measures that are happening at an uncertain point in time (i.e. in the past or the future) and at a remote place (i.e. not in the “here and now” of consumers; Liberman et al., Citation2007). These claims propose environmental compensation for the environmental impact of flying, like investing in tree planting, ecological projects, or environmental research at an unspecified point in time and place (e.g. Air New Zealand, Citation2024; KLM, Citation2024).

Since previous research has investigated consumers’ perceptions of greenwashing claims primarily in the form of false, vague, and executional claims while not treating other types in much detail (e.g. Matthes, Citation2019; Schmuck et al., Citation2018), there is a need for a closer look on effects of omission claims, such as in the form of compensation claims. Prior findings of other greenwashing claims cannot be generalized to compensation claims for two reasons. First, by omitting important information, omission claims are implicit deception claims and, thus, might be more challenging to detect as greenwashing than other more explicit forms of deception, such as false claims (e.g. Chaouachi & Rached, Citation2012; Schmuck et al., Citation2018). Second, compensation claims might be especially persuasive by triggering compensatory green beliefs, which could distract consumers from perceptions of greenwashing (e.g. Hope et al., Citation2018).

However, in this context, Neureiter and Matthes (Citation2023) have recently found that concrete compensation claims are only detected as greenwashing by consumers with high environmental knowledge. Moreover, greenwashing perceptions were negatively associated with brand evaluations and positive emotions (for purchase intentions, see Neureiter et al., Citation2023). However, in order to make valid generalizations based on robust findings, we still need more empirical evidence in this context (Kerr et al., Citation2016).

Information processing of green advertising claims of airlines

According to the Schema Theory (e.g. Mandler, Citation1982), new information congruent with existing knowledge is processed by individuals more quickly and with fewer cognitive resources than new incongruent information (e.g. Fiske & Taylor, Citation1984). In contrast, when an advertising message is incongruent with consumers’ existing schema of the advertised product or service, it is suggested that consumers are motivated to process these messages carefully to resolve the perceived incongruence (Mandler, Citation1982). In line with this, previous research has shown that incongruent information in advertising attracts consumers’ attention and intensifies information processing (e.g. Halkias & Kokkinaki, Citation2013).

As a consequence of consumers’ increasing environmental concern, their heightened environmental awareness as well as intensive media coverage of environmentally unfriendly consequences of flying, and heightened attention of NGOs toward environmental claims of inherently environmentally unfriendly companies such as airlines, the image of flying seems to have changed in recent years (e.g. Asquith, Citation2020). Socially, flying was considered a desirable behavior a few years ago, but nowadays, it is seen as environmentally harmful and, hence, socially undesirable (Gössling et al., Citation2020). Due to this, the environmentally harmful impact of flying seems immediately salient to consumers nowadays when they look at airline advertising (e.g. Benady, Citation2007; Randles & Mander, Citation2009).

It can, thus, be suggested that supposedly green advertising for inherently environmentally unfriendly services such as flying is perceived by consumers as incongruent with existing knowledge about the environmentally harmful impact of flying. Further, we argue that due to schema incongruence of airlines’ supposedly green advertising, consumers tend to be highly attentive toward these ads, encode them in a very detailed manner, and allocate cognitive resources toward them to process them thoroughly (e.g. Halkias & Kokkinaki, Citation2013). As Schmuck et al. (Citation2018) showed that cognitive effort is an important precondition to perceive greenwashing, we assume that consumers are able to recognize greenwashing in advertising of inherently environmentally harmful products or services promoting environmental friendliness. We therefore formulate our first hypothesis as:

H1: If (a) a concrete compensation or (b) an abstract compensation greenwashing claim is presented in an airline ad, perceived greenwashing will be higher compared to an ad presenting no green claims.

In the context of our study, this means that concrete compensation claims – considered highly effective through low psychological distance and, thus, high tangibleness of the measures – are likely to be more persuasive than abstract compensation claims. In line with this, Han, Baek et al. (Citation2019) showed that a claim that is characterized by psychological proximity and, thus, is seen as concrete was more powerful in promoting environmental behavior than a claim that is described as psychologically distant and, thus, abstract.

In addition, compensatory green beliefs might further enhance the persuasion effect of concrete compensation claims. Previous research has shown that individuals tend to hold compensatory green beliefs to balance their environmental behavior (e.g. Hope et al., Citation2018). In other words, they aim to neutralize environmentally harmful behavior with environmental protection behavior. These beliefs – possibly triggered by compensation claims – have the potential to reduce consumers’ guilt of engaging in the socially undesirable behavior of flying and justify consumers’ flying behavior (e.g. Hope et al., Citation2018). However, for compensatory green beliefs to be evoked, individuals need to believe in the efficacy of the compensation behavior. When efficacy is low, individuals might lack the conviction that a compensation behavior may actually make a difference (e.g. Hope et al., Citation2018). Due to stronger perceptions of efficacy elicited by concrete compensation claims (e.g. Liberman et al., Citation2007), stronger compensatory green beliefs might be triggered. This could distract consumers from recognizing greenwashing (Hope et al., Citation2018).

To sum it up, based on the Theory of Psychological Distance (e.g. Liberman et al., Citation2007) as well as prior research (e.g. Han, Yu, & Kim, Citation2019; Hope et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2000), we assume that consumers evaluate concrete compensation claims less critically than abstract compensation claims due to (1) greater persuasion effects, and (2) stronger compensatory green beliefs elicited by concrete compensation claims. Since critical evaluation of supposedly green claims is crucial to recognize greenwashing (ELM; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986), we hypothesize:

H2: When a concrete compensation claim is presented in an airline ad, perceived greenwashing will be lower compared to an ad presenting an abstract compensation claim.

The moderating role of environmental knowledge

In the context of green advertising, the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986) serves as a basis to explain how consumers’ ability to process information influences consumers’ perceptions of advertisements (e.g. Parguel et al., Citation2015). Following the logic of the ELM, consumers process information either along the central route or the peripheral route of information processing, depending on consumers’ characteristics. The competent consumer, who is characterized by high motivation or ability to process persuasive information, most likely will process advertising claims along the central route of information processing and, therefore, in a “careful” and “thoughtful” manner (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986, p. 125). The less competent consumer, characterized by low motivation or ability to process persuasive information, is most likely to process advertising claims along the peripheral route that implies a passive and simple evaluation process using heuristic shortcuts (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986).

Previous studies have suggested that consumers’ involvement with advertising topics increases their elaboration of advertising messages due to more proper judgment of the trustworthiness of claims used in the ads (e.g. Parguel et al., Citation2015). Since one key indicator for involvement is environmental knowledge (e.g. Naderer & Opree, Citation2021), knowledge about environmental topics (e.g. recycling or packaging) is assumed to be helpful for consumers to detect greenwashing in false green claims (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018). Further, environmental knowledge about airlines and flights enables consumers to recognize greenwashing in airline advertising (Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023). Similarly, Parguel et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated that high environmental knowledge reduces the misleading impact of executional greenwashing of advertising on consumers’ brand evaluations.

Since environmental knowledge can be conceptualized as an indicator of the central route of information processing, we assume that consumers with high environmental knowledge are more likely to detect greenwashing because of more “careful” and “thoughtful” evaluation of the message compared to consumers with low environmental knowledge (e.g. Naderer & Opree, Citation2021; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986, p. 125). Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H3: Compared to an ad with no green claims, the effect of a (a) concrete compensation claim and an (b) abstract compensation claim on perceived greenwashing is higher for consumers with high environmental knowledge than for less knowledgeable consumers.

Consequences of perceived greenwashing for the advertised brand

Generally, consumers value their right to decide autonomously what products or services they purchase (e.g. Koslow, Citation2000). Greenwashing claims that contain unfair, deceptive, misleading, and unsubstantiated persuasive elements (European Commission, Citation2014; FTC, Citation2012) may be considered by consumers as advertisers’ unjust attempts to push them in a specific direction. Based on this, we assume that perceptions of greenwashing may pose a threat to consumers’ perceived freedom regarding their purchases (Brehm, Citation1966). Consequently, consumers are likely to show psychological reactance, resulting in resistance against the persuasive advertising attempt and rebellion against the threatening source, in our case, the advertised airline (e.g. Brehm, Citation1966; Koslow, Citation2000). In accordance, previous studies have found that when consumers detect the misleading character of supposedly green advertising, it can easily “backfire” and cause adverse effects on consumers’ brand evaluation (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, derived from theoretical assumptions (e.g. Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1977) as well as empirical evidence (e.g. Belleau et al., Citation2007), consumers are less likely to hold purchase intentions when their evaluations of the brands are negative. Thus, we assume that the evaluation of airline brands is a predictor of the purchase behavior of services from the airline. Taken together, perceived greenwashing may harm purchase intentions by reducing brand evaluations. We thus hypothesize the following:

H4: Perceived greenwashing decreases (a) brand evaluation for the advertised brands, which in turn decreases (b) purchase intention of the advertised brands.

Consequences of perceived greenwashing for the advertised product and service category

Particular airline brands can represent a “superordinate” product category of air transport services (Halkias, Citation2015, p. 440). Previous communication research has underlined this assumption by showing that negative spillover effects can occur, transferring from consumers’ evaluations of a single brand to related brands in the same product category (e.g. Janakiraman et al., Citation2009). Therefore, we suggest that consumers’ evaluations of single airlines might influence their attitudes toward the whole airline sector by decreasing general attitudes toward flying (Halkias, Citation2015). In other words, when greenwashing is detected in an airline ad, the evaluation of the single airline and general attitudes toward flying, and, thus, the whole airline sector may be influenced negatively (e.g. Polonsky et al., Citation2010). In a broader context, misleading green advertising attempts of particular brands may undermine not only consumers’ trust and confidence in a specific brand but also all environmental endeavors in this particular sector (e.g. Janakiraman et al., Citation2009). As a result, it is possible that greenwashing claims in single advertising campaigns can impair attitudes toward the whole airline sector by reinforcing consumers’ mistrust of green products in the entire industry (e.g. Polonsky et al., Citation2010). Hence, when greenwashing is recognized, consumers’ general attitudes toward flying might be negatively influenced, which, consequently, might be associated with consumers’ reduced general intention to fly in the future. We therefore assume that:

H5: Perceived greenwashing decreases (a) general attitudes toward flying, which in turn decreases (b) general intentions to fly in the future.

Our full conceptual model is shown in .

Method

We employed a between-subject design manipulating the type of greenwashing (concrete compensation vs. abstract compensation) in green ads of three different airlines, plus a control condition presenting no green claims. Participants of the study (N = 329) were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions or the control group. They were confronted with a multiple message design (e.g. Reeves et al., Citation2016) randomly showing three ads from three airline brands (HiFly, s7 airlines, and SprintAir). Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Communication of the University of Vienna in response to documents submitted for faculty presentation.

Participants

We recruited a quota-based sample on age, gender, and education (N = 329; Mage = 46.81, SD = 16.08; 50.8% women; 42.6% lower education, 39.8% medium education, 17.7% higher education) in Germany with the help of a professional market research institute.

Stimuli

We employed nine versions of ads presented in the form of Twitter postings from three different airlines. For each airline, we created three ads and prepared them to fit either the concrete compensation condition, the abstract compensation condition, or the control condition presenting no green claims.

Participants assigned to the concrete compensation condition viewed ads referring to different recycling measures, such as reducing or recycling plastic garbage on board. The abstract compensation condition contained ads describing environmental initiatives, such as investing parts of the airlines’ gains in tree planting, environmental projects, or research. In the control condition, no references to environmental measures were made. The main focus of the ads was on vacation and relaxation.

While the advertising claims varied across the conditions and the airlines, the layout of the airline ads between the groups was kept consistent and contained typical advertising elements like a logo, a slogan, and an image. The presented ads were created for the purpose of this study only. Inspiration, however, was drawn from existing ads. In order to guarantee high levels of external validity and ensure that no strong prior attitudes toward the airlines existed, we chose real but comparatively small airline companies for the stimuli.

To check the validity of our stimuli, we performed a post-hoc expert rating with senior advertising scholars (N = 6) from various European universities. Overall, concrete claims were significantly categorized as concrete, while abstract compensation claims were significantly identified as abstract by the experts. On average, 4.83 out of 6 compensation claims were correctly classified as such, supporting the validity of the stimuli. Additionally, we conducted another post-hoc expert rating with senior persuasive communication scholars (N = 13). Results showed that experts perceived abstract compensation measures as more psychologically distant (M = 6.08, SD = 1.68) than concrete compensation measures (M = 2.19, SD = 1.52; t(12) = 5.17, p < .001). Moreover, abstract compensation claims conveying abstract measures were considered as more psychologically distant (M = 6.23, SD = 0.86) and less psychologically close (M = 1.31, SD = 0.43) than concrete compensation claims conveying concrete measures (distant: N = 13; M = 2.04, SD = 0.75; t(12) = 10.86, p < .001; close: M = 5.96, SD = 0.88; N = 13; t(12) = −18.21, p < .001).

For stimuli, please see Table A1 in the Online Appendix under OSF (https://osf.io/9kcge/?view_only=e71778fa2ed34c3287c4fe6ae6084fce).

Measures

For the wordings of all used items, please see Table A2 in the Online Appendix under OSF (https://osf.io/9kcge/?view_only=e71778fa2ed34c3287c4fe6ae6084fce). If not stated otherwise, all items are measured on a seven-point scale.

Mediators

We measured perceived greenwashing with three items based on Chen and Chang (Citation2013) ranging from 1 – “I do not agree” to 7 – “I completely agree” (Cronbach’s α = .72; M = 4.49, SD = 1.44). For instance, we asked participants to indicate how strongly they agreed with the following statement: “The advertised measures sound more useful for the environment than they actually are.” In order to assess brand evaluation, participants were asked to rate three adjective pairs (i.e. “uninteresting – interesting”) that best reflected their evaluation of each airline brand one after another. Since this semantic differential scale was based on previous studies in this context (see, e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018) and yielded one factor, we summarized the items across brands to create an index (Cronbach’s α = .97; M = 3.94, SD = 1.40). Attitudes toward flying were measured on a semantic differential scale with seven adjective pairs (i.e. “unappealing – appealing”) derived from Bruner et al. (Citation2005), allowing participants the opportunity to evaluate the airplane as a mean of transportation (Cronbach’s α = .91; M = 4.10, SD = 1.38).

Moderators

For environmental knowledge, we built on five single-choice questions about different aspects of environmental knowledge inspired by Maloney and Ward (Citation1973; Maloney et al., Citation1975). For instance, we asked participants to indicate if the following statement is correct or false: “Most drinking water is used for agriculture”. By summarizing the correct answers, we created a six-point scale (0 = no environmental knowledge, 5 = high environmental knowledge; M = 1.71, SD = 1.18).

Dependent variables

Purchase intention was measured with three items, each ranging from 1 – “no way” to 7 – “definitely” asking for the future intention to fly with the respective airline (Chan et al., Citation2006; Cronbach’s α = .93; M = 3.53, SD = 1.57). For instance, we asked participants: “Would you book a flight with HiFly in the future?”. Intentions to fly in the future were measured with four items on the same scale as purchase intention, asking the participants how likely they will use an airplane for their next trip (Cronbach’s α = .92; M = 3.38, SD = 2.03). For example, we asked them to indicate how strongly they agreed with the following statement: “I would like to fly by plane in the coming year.”

For a descriptive overview of all mediators and dependent variables per condition, see .

Table 1. Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) of mediators and dependent variables.

Randomization and manipulation check

There were no systematic differences in age, gender, education, environmental knowledge, and flight frequency across our conditions (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix under OSF [https://osf.io/9kcge/?view_only=e71778fa2ed34c3287c4fe6ae6084fce]). Further, participants agreed that the abstract compensation claim dealt with investments in environmental projects or research (F(2, 329) = 180.80, p < .001), the concrete compensation claim addressed the reduction of plastic and recycling (F(2, 329) = 140.67, p < .001), and the control ads covered holiday topics (F(2, 329) = 107.80, p < .001). Thus, the manipulation can be deemed successful. For more details, see Table A4 in the Online Appendix under OSF (https://osf.io/9kcge/?view_only=e71778fa2ed34c3287c4fe6ae6084fce).

Results

We tested our proposed theoretical model with purchase intention and general intention to fly in the future as the dependent variables using SPSS Macro PROCESS, Model 83, involving 1.000 bootstrap samples (Hayes, Citation2018). We examined our two dependent variables in two separate models. We treated perceived greenwashing and either brand evaluation or attitudes toward flying as the successive mediators. We inserted participants’ environmental knowledge as a moderator (mean-centered). We used the control condition as our reference group. To make the differences between the greenwashing conditions observable, we ran the analysis again, treating the concrete compensation condition as a reference group.

Unrelated to our hypotheses, we did an additional analysis of variance with repeated measures to test whether the effects significantly differ by brand as a within-subjects factor. We neither observed significant interaction effects of perceived greenwashing and brand type nor main effects of brand type on brand evaluation and purchase intention. We thus used the anticipated PROCESS Model 83.

Hypotheses tests

Perceived greenwashing

Against our first assumption (H1a), we found that individuals in the concrete compensation condition did not have a higher level of perceived greenwashing compared to the control group (b = 0.03, p = .872; LLCI = −0.35; ULCI = 0.41). Yet, H1b found support, as the abstract compensation condition had significantly higher levels of perceived greenwashing compared to the control group (b = 0.44, p = .022; LLCI = 0.06; ULCI = 0.81). To examine our second hypothesis (H2), we calculated the same model again and inserted the concrete compensation condition as the reference group. We found that the abstract compensation condition also significantly increased perceived greenwashing compared to the concrete compensation condition (b = 0.41, p = .037; LLCI = 0.03; ULCI = 0.79). This means that compared to both a control group and the concrete compensation condition, abstract compensation claims increased perceived greenwashing.

Moderating role of environmental knowledge

To examine our third hypothesis, we looked at the moderating role of environmental knowledge. We found no interaction effect of environmental knowledge with either experimental condition (concrete compensation condition*environmental knowledge: b = 0.16, p = .328; LLCI = −0.16; ULCI = 0.48; abstract compensation condition*environmental knowledge: b = 0.11, p = .492; LLCI = −0.21; ULCI = 0.44), nor a main effect of environmental knowledge on perceived greenwashing (b = 0.07, p = .551; LLCI = −0.16; ULCI = 0.30). Thus, H3a and H3b found no support.

Brand evaluation and purchase intentions

For brand evaluation, we did not find a main effect of the experimental conditions compared to the control group. Yet, as hypothesized (H4a), we found that perceived greenwashing was negatively associated with brand evaluation (b = −0.17, p = .001; LLCI = −0.28; ULCI = −0.07). In line with our assumption (H4b), we furthermore found that brand evaluation was positively related to purchase intention (b = 0.89, p < .001; LLCI = 0.82; ULCI = 0.97). In addition, perceived greenwashing negatively correlated with purchase intention (b = −0.08, p = .037; LLCI = −0.15; ULCI = −0.01). The assumed mediation path via perceived greenwashing, brand evaluation, and purchase intention was only supported for the abstract compensation condition compared to the control group (b = −0.07, SE = .043; LLCI = −0.17; ULCI = −0.01).

Attitudes toward flying and intentions to fly in the future

For attitudes toward flying, we again did not find a main effect of the experimental conditions compared to the control group. However, as hypothesized in H5a, we found that perceived greenwashing was negatively related to attitudes toward flying (b = −0.19, p < .001; LLCI = −0.29; ULCI = −0.09). Lending support to H5b, we furthermore found that attitudes toward flying were positively associated with intentions to fly in the future (b = 0.92, p < .001; LLCI = 0.79; ULCI = 1.05). The assumed mediation path via perceived greenwashing, attitudes toward flying, and intentions to fly in the future only found support for the abstract compensation condition compared to the control group (b = −0.08, SE = .041; LLCI = −0.17; ULCI = −0.01).

For details on the analysis, see .

Table 2. Moderated mediation model.

Discussion

Based on theoretical assumptions of information processing of incongruent information (e.g. Halkias & Kokkinaki, Citation2013), we suggested that consumers can detect greenwashing in advertising that promotes environmentally inherently harmful services such as flying as green. However, results showed that while abstract green compensation claims enhanced perceptions of greenwashing, consumers did not detect greenwashing in concrete compensation claims. This suggests that concrete compensation claims were regarded as offering plausible and sound environmental measures to combat climate change. An explanation for this finding might be that concrete environmental measures (e.g. reusable cutlery on board) offered in airlines’ advertising were perceived by consumers as psychologically near and, thus, more tangible and effective than abstract measures (e.g. environmental research projects; Liberman et al., Citation2007; see also Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023). Consumers seem to feel more assured with concrete compensation claims that “contain relative certainty that following the recommendation will lead to the desired state of affair” (Lee et al., Citation2000, p. 12). Moreover, it is possible that due to the perceived efficacy of the concrete proposed measures, compensatory green beliefs were triggered that distracted consumers from a more critical point of view, preventing greenwashing perceptions (e.g. Hope et al., Citation2018).

In conclusion, it seems that the perceived tangibility of concrete environmental compensation measures, conveyed in concrete compensation claims, distracts consumers from the fact that important information is missing in compensation claims (e.g. BEUC, Citation2023). Furthermore, perceptions of tangibility may positively influence perceptions of the effectiveness of concrete offsets, leading to greater acceptance of concrete offsets compared to abstract offsets. However, future research needs to test the role of consumer perceptions of the efficacy of purportedly green claims in the context of greenwashing perceptions. To assess the real environmentally neutralizing effect that is promised in the ads, consumers need important information about the real benefit of the compensation measure that, however, is omitted in compensation claims. By showing this, this study validated the effects of concrete and abstract compensation claims on perceived greenwashing that were shown by Neureiter and Matthes (Citation2023) and Neureiter et al. (Citation2023). By replicating the findings, this study robustly advanced knowledge in advertising research (Kerr et al., Citation2016).

Interestingly enough, no other main effects of the conditions on brand or flying assessments occurred. This leads us to the conclusion that employing greenwashed claims in airline ads compared to ads with non-green claims does not foster nor hinder brand evaluations and attitudes toward flying if greenwashing perceptions are not triggered.

Furthermore, contrary to our expectations, results indicated that general environmental knowledge did not help consumers detect greenwashing claims in ads. However, in line with the ELM (e.g. Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986) that describes involvement and knowledge as a key element of consumer behavior, previous research has demonstrated that general environmental knowledge (e.g. recycling or packaging) is helpful for consumers to recognize false green claims (Schmuck et al., Citation2018) as well as executional greenwashing in advertising messages (Parguel et al., Citation2015). A possible explanation of our contrary finding could be that for omission claims in the form of compensation claims, general environmental knowledge is too broad to fill the environmental information gap left by them. Thus, general environmental knowledge is not helping consumers to understand or evaluate omission claims in the form of compensation claims properly. This could mean that moderators such as environmental knowledge may only matter for some (e.g. Schmuck et al., Citation2018), but not all types of greenwashing, possibly also depending on the kind of knowledge and if it is helpful for the assessment of the environmental impact of the advertised products or services. In fact, Neureiter and Matthes (Citation2023) showed that topical knowledge focusing on environmental facts about the specific advertised product or service helped consumers to spot greenwashing in concrete compensation claims. Thus, we can conclude that unspecific, broad, and general environmental knowledge seems to be irrelevant in perceiving greenwashing, at least in omission claims in the form of compensation claims.

Finally, findings showed that perceived greenwashing elicited through abstract compensation claims negatively affected consumers’ brand evaluation and purchase intention. This finding aligns with the Theory of Psychological Reactance (Brehm, Citation1966), suggesting that consumers react negatively to greenwashing attempts. There was also a negative relationship between perceived greenwashing and purchase intention, independent of brand evaluation. Other brand evaluation dimensions not captured with our measure may be responsible for this finding. Furthermore, perceived greenwashing was negatively related to consumers’ attitudes toward flying and their intention to fly in the future. Hence, based on the Schemata Theory (e.g. Halkias, Citation2015), abstract compensation claims in airline advertising can backfire on the brand and the whole airline industry.

Surprisingly, besides the hypothesized mediated relationship of perceived greenwashing with brand evaluation and purchase intention, we also observed a negative association between perceived greenwashing and purchase intention. We argue that this points to an additional mediation process that we did not observe. It is likely that the recognition of greenwashing is not only negatively related to attitudinal reactions (i.e. brand evaluations) but could also be positively associated with cognitive resistance strategies such as counter-arguing (Van Reijmersdal et al., Citation2016).

Limitations and future research

A number of important limitations must be considered. First, our findings are limited to the context of airline ads. As the environmental harmful impact of flying is increasingly salient in society and flight shame increases (e.g. Gössling et al., Citation2020), greenwashing practices might work differently for lower-involvement, convenient products or services. Thus, future research should examine greenwashing in the form of compensation claims for other products and services as well (e.g. Matthes, Citation2019).

Second, caution must be applied as the findings might not be transferable to different cultural contexts. Since this study was conducted in a European context where, generally, a high level of knowledge and awareness about the environmental harm of flying exists (e.g. Aviation Index, Citation2021), findings might not be generalizable to other countries. It would be interesting to compare perceptions of greenwashing in different cultural contexts.

Third, regarding methodological limitations, we were only able to observe respondents’ purchase intentions and intentions to fly in the future and not their actual behavior. Particularly for environmentally friendly behavior, past studies have reported an intention-behavior gap (e.g. Kennedy et al., Citation2009). Hence, further research is needed to account for possible social desirability bias when measuring behavioral intentions with regard to flying.

Finally, although the employed measures of environmental knowledge were based on existing, established questions (e.g. Maloney et al., Citation1975), environmental knowledge was rather low in our sample (M = 1.71, SD = 1.88; on a scale ranging from 0 to 5). Further work needs to be done to establish whether other knowledge measures are more suitable.

Practical implications

Our findings indicated three important implications for advertising practitioners as well as consumer protection initiatives. First, green advertising does not always pay off when it comes to airline advertising. When consumers perceive greenwashing in airline ads, the entire airline sector can be influenced in a negative way. Hence, when advertising practitioners use environmental compensation claims for airlines, they should substantiate them. This means that airlines should refrain from highlighting individual compensation measures that are marginal in relation to the overall damage caused by flying. Instead, they should focus on specific statements about environmental measures that have a significant positive impact on the environment, such as sustainable aviation fuel (i.e. addresses the core business). Additionally, the environmental benefit should be explained in a detailed way, for instance, by adding a specification with numbers. One possibility would be to implement an eco-label for airlines to make their offers comparable in terms of environmental criteria (e.g. Baumeister & Onkila, Citation2017). With credible and transparent information, consumers’ environmental awareness is raised, and consumers can be easily informed about the least environmentally harmful travel choices (e.g. Gössling & Buckley, Citation2016). However, if airlines – easily accused of greenwashing – cannot substantially contribute to transforming their company more environmentally friendly, they should refrain from green advertising at all to prevent tapping into greenwashing.

Second, our findings suggest that industry guidelines explaining to airline advertisers how to make substantial green claims should be revised and expanded. While more and more companies use various compensation claims in their advertising strategy (e.g. Polonsky et al., Citation2010), we believe that this type of green claim is currently not adequately addressed in industry guidelines (e.g. FTC, Citation2012). Hence, we call for an update of industry guidelines, enlightening practitioners on how to prevent greenwashing in compensation claims.

Finally, according to our findings, for consumer protection initiatives, such as awareness campaigns, it may not be enough to educate consumers about general environmental issues (e.g. smog and electricity) to empower them to detect greenwashing claims in airline advertising. We would rather recommend implementing initiatives focusing on topical environmental knowledge tailored to ads of the industries that greenwash the most (Neureiter & Matthes, Citation2023).

Conclusion

Especially for products and services that are inherently environmentally unfriendly, greenwashing may appear to be an attractive strategy for marketers and practitioners in order to reshape the reputation of a brand, product, or service. The findings of our study suggest, however, that greenwashing claims, such as abstract compensation claims, do not pay off for inherently environmentally unfriendly companies such as airlines because consumers perceive greenwashing in these claims. Moreover, these perceptions of greenwashing were associated with consumers’ negative brand evaluations, lower purchase intentions as well as general negative attitudes toward flying and lower intentions to generally fly in the future. Although concrete compensation claims do not have this negative effect on brand outcomes compared to abstract ones, they do not per se have any positive effect on brand evaluations, purchase intentions, attitudes toward flying and intentions to generally fly in the future. We conclude that it is not enough for airlines only to promote that they protect the environment. They also need to prove that their communicated actions do have a significant and measurable positive effect on the environment by providing enough information.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (379.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data set used in this study is available in a public data repository of the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/9kcge/?view_only=e71778fa2ed34c3287c4fe6ae6084fce).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Air New Zealand. (2024). Our voluntary emissions contribution programme. https://www.airnewzealand.co.nz/sustainability-carbon-offset#:~:text=When%20you%20book%20your%20flight,purchased%20from%20certified%20international%20projects.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

- Alfaro, V. N., & Chankov, S. (2022). The perceived value of environmental sustainability for consumers in the air travel industry: A choice-based conjoint analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 380(2), 134936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134936

- Asquith, J. (2020, January 13). The spread of flight shame in Europe—Is Greta Thunberg the reason why? https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesasquith/2020/01/13/the-spread-of-flight-shame-in-europe-is-greta-thunberg-the-reason-why/?sh=62986c5369bd.

- Atkinson, L., & Kim, Y. (2015). “I drink it anyway and I know I shouldn’t”: Understanding green consumers’ positive evaluations of norm-violating non-green products and misleading green advertising. Environmental Communication, 9(1), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.932817

- Aviation Index. (2021). Aviation and climate change. https://www.nats.aero/news/aviation-index-2021/.

- Baum, L. M. (2012). It’s not easy being green … or is it? A content analysis of environmental claims in magazine advertisements from the United States and United Kingdom. Environmental Communication, 6(4), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2012.724022

- Baumeister, S., & Onkila, T. (2017). An eco-label for the airline industry? Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 1368–1376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.11.170

- Belleau, B. D., Summers, T. A., Xu, Y., & Pinel, R. (2007). Theory of reasoned action: Purchase intention of young consumers. Clothing and Textiles Journal, 25(3), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X07302768

- Benady, D. (2007). Brands show true colours. https://www.marketingweek.com/brands-show-true-colours/.

- BEUC. (2023). Consumer groups launch EU-wide complaint against 17 airlines for greenwashing. https://www.beuc.eu/sites/default/files/publications/BEUC-PR-2023-026_Consumer_groups_launch_EU-wide_complaint_against_17_airlines_for_greenwashing.pdf.

- Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press. ISBN-10, 0121298507.

- Bruner, G., Hensel, P., & James, K. (2005). Marketing scales handbook, volume IV: A compilation of multi-item measures for consumer behavior & advertising. Thomson Higher Education. ISBN: 1-58799-205-1.

- Chadwick, A., & Stanyer, J. (2022). Deception as a bridging concept in the study of disinformation, misinformation, and misperceptions: Toward a holistic framework. Communication Theory, 32(1), 1–24. http://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab019

- Chan, R. Y. K., Leung, T. K. P., & Wong, Y. H. (2006). The effectiveness of environmental claims for services advertising. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(4), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040610674580

- Chaouachi, S. G., & Rached, K. S. B. (2012). Perceived deception in advertising: Proposition of a measurement scale. Journal of Marketing Research and Case Studies, 712622. https://doi.org/10.5171/2012.712622

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C.-H. (2013). Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects on green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(3), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

- De Freitas Netto, S. V., Sobral, M. F. F., Ribeiro, A. R. B., & da Luz Soares, G. R. (2020). Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environmental Science Europe, 32(19), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3

- European Commission. (2014). Consumer market study on environmental claims for non-food products. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ae7f9aa1-bdea-4ad2-82d1-835549c3ce2a/language-en.

- Federal Trade Commission. (2012). Guides for the use of environmental marketing claims. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/federal_register_notices/guides-use-environmental-marketing-claims-green-guides/greenguidesfrn.pdf.

- Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1984). Social cognition. Random House. ISBN 10: 039434801X.

- Gössling, S., & Buckley, R. (2016). Carbon labels in tourism: Persuasive communication? Journal of Cleaner Production, 111, 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.08.067

- Gössling, S., Humpe, A., & Bausch, T. (2020). Does ‘flight shame’ affect social norms? Changing perspectives on the desirability of air travel in Germany. Journal of Cleaner Production, 266, 122015–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122015

- Halkias, G. (2015). Mental representation of brands: A schema-based approach to consumers’ organization of market knowledge. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(5), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-02-2015-0818

- Halkias, G., & Kokkinaki, F. (2013). Increasing advertising effectiveness through incongruity-based tactics: The moderating role of consumer involvement. Journal of Marketing Communications, 19(3), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2011.592346

- Han, H., Yu, J., & Kim, W. (2019). Environmental corporate social responsibility and the strategy to boost the airline’s image and customer loyalty intentions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1557580

- Han, N. R., Baek, T. H., Yoon, S., & Kim, Y. (2019). Is that coffee mug smiling at me? How anthropomorphism impacts the effectiveness of desirability vs. feasibility appeals in sustainability advertising. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.06.020

- Harding-Rolls, G. (2022). Greenwash. https://greenwash.com/information/.

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2009). Green advertising revisited. Conditioning virtual nature experiences. International Journal of Advertising, 28(4), 715–739. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048709200837

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. ISBN-10: 1609182308.

- HiFly. (2019). New campaign to end plastic pollution. http://www.hifly.aero/media-center/new-campaign-to-end-plastic-pollution/.

- Hope, A. L. B., Jones, C. R., Webb, T. L., Watson, M. T., & Kaklamanou, D. (2018). The role of compensatory beliefs in rationalizing environmentally detrimental behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 50(4), 401–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517706730

- Janakiraman, R., Sismeiro, C., & Dutta, S. (2009). Perception spillovers across competing brands: A disaggregate model of how and when. Journal of Marketing Research, 46(4), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.46.4.467

- Kangun, N., Carlson, L., & Grove, S. J. (1991). Environmental advertising claims: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10(2), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569101000203

- Kennedy, E. H., Beckley, T. M., McFarlane, B. L., & Nadeau, S. (2009). Why we don’t “Walk the Talk”: Understanding the environmental values/behaviour gap in Canada. Human Ecology Review, 16(2), 151–160. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24707539

- Kerr, G., Schultz, D. E., & Lings, I. (2016). “Someone should do something”: Replication and an agenda for collective action. Journal of Advertising, 45(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1077492

- KLM. (2024). Sustainability. https://www.klm.at/en/information/sustainability.

- Koslow, S. (2000). Can the truth hurt? How honest and persuasive advertising can unintentionally lead to increased consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34(2), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2000.tb00093.x

- Kwon, K., Lee, J., Wang, C., & Diwanji, V. S. (2024). From green advertising to greenwashing: Content analysis of global corporations’ green advertising on social media. International Journal of Advertising, 43(1), 97–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2023.2208489

- Lee, C. K.-C., Brown, R., & Blood, D. (2000). The effects of efficacy, cognitive processing and message framing on persuasion. Australasian Marketing Journal, 8(2), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3582(00)70187-X

- Leonidou, L. C., Leonidou, C. N., Palihawadana, D., & Hultman, M. (2011). Evaluating the green advertising practices of international firms: A trend analysis. International Marketing Review, 28(1), 6–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331111107080

- Liberman, N., Trope, Y., & Stephan, E. (2007). Psychological distance. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 353–382). The Guilford Press. ISBN:1462514863.

- Maloney, M. P., & Ward, M. P. (1973). Ecology: Let’s hear from the people: An objective scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. American Psychologist, 28(7), 583–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034936

- Maloney, M. P., Ward, M. P., & Braucht, G. N. (1975). A revised scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. American Psychologist, 30(7), 787–790. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0084394

- Mandler, G. (1982). The structure of value: Accounting for taste. In M. S. Clark & S. T. Fiske (Eds.), Affect and cognition (pp. 3–36). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN: 9781315802756.

- Matthes, J. (2019). Uncharted territory in research on environmental advertising: Toward an organizing framework. Journal of Advertising, 48(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1579687

- Mayer, R., Ryley, T., & Gillingwater, D. (2012). Passenger perceptions of the green image associated with airlines. Journal of Transport Geography, 22, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.007

- Naderer, B., & Opree, S. J. (2021). Increasing advertising literacy to unveil disinformation in green advertising. Environmental Communication, 15(7), 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.1919171

- Neureiter, A., & Matthes, J. (2023). Comparing the effects of greenwashing claims in environmental airline advertising: Perceived greenwashing, brand evaluation, and flight shame. International Journal of Advertising, 42(3), 461–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2022.2076510

- Neureiter, A., Stubenvoll, M., & Matthes, J. (2023). Is It greenwashing? Environmental compensation claims in advertising, perceived greenwashing, political consumerism, and brand outcomes. Journal of Advertising. Advance online publication. http://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2023.2268718.

- Olk, S. (2021). The effect of self-congruence on perceived green claims’ authenticity and perceived greenwashing: The case of EasyJet’s CO2 promise. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 33(2), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2020.1798859

- Parguel, B., Benoit-Moreau, F., & Russell, C. A. (2015). Can evoking nature in advertising mislead consumers? The power of ‘executional greenwashing’. International Journal of Advertising, 34(1), 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.996116

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60214-2

- Polonsky, M. J., Grau, S. L., & Garma, R. (2010). The new greenwash? Potential marketing problems with carbon offsets. International Journal of Business Studies: A Publication of the Faculty of Business Administration, Edith Cowan University, 18(1), 49–54. ISSN: 1320-7156.

- Randles, S., & Mander, S. (2009). Aviation, consumption and the climate change debate: ‘Are you going to tell me off for flying?’. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 21(1), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320802557350

- Reeves, B., Yeykelis, L., & Cummings, J. J. (2016). The use of media in media psychology. Media Psychology, 19(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2015.1030083

- Schmuck, D., Matthes, J., & Naderer, B. (2018). Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect-reason-involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. Journal of Advertising, 47(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2018.1452652

- Segev, S., Fernandes, J., & Hong, C. (2016). Is your product really green? A content analysis to reassess green advertising. Journal of Advertising, 45(1), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1083918

- Szabo, S., & Webster, J. (2021). Perceived greenwashing: The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(4), 719–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0

- Van Reijmersdal, E. A., Fransen, M. L., Van Noort, G., Opree, S. J., Vandeberg, L., Reusch, S., Van Lieshout, F., & Boerman, S. C. (2016). Effects of disclosing sponsored content in blogs: How the use of resistance strategies mediates effects on persuasion. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(12), 1458–1474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216660141

- Virgin Australia Airlines. (2019). Reducing our footprint at 35,000 feet. http://www.virginaustralia.com/cn/en/about-us/sustainability/.