ABSTRACT

Polarization dynamics around climate change are shifting from debates about the reality and severity of climate change to debates about climate solutions. We propose taking a value-based approach to understanding “climate-solutions polarization”. As a case study, we identified the discursive value expressions underlying the polarized biomass media discourse in the Netherlands, from 2019–2021. A discourse analysis showed how the value expressions (a) climate security, (b) environmental benevolence, and (c) local security produce an opposition discourse, whereas the value expressions (d) climate achievement, (e) technological security, and (f) economic security underpin advocacy discourse. We discuss how the strong presence of security values provides both communication opportunities and risks for transitioning to climate-resilient societies. Further, our research shows how both sides of the debate have scientific actors on their side using distinctive rhetorical strategies, providing insight into debates about the role of values in science. The value-based approach to understanding climate-solutions polarization is promising for both the science and practice of environmental communication.

1. Introduction

In March 2023, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its latest report of the Sixth Assessment cycle stating that human activities have “unequivocally” caused climate change (IPCC, Citation2023). For a long time now, there has been a scientific consensus that humans are responsible for climate change. Yet, while public concern about climate change has been growing in the last few years (European Commission, Citation2021; Leiserowitz et al., Citation2021), the twenty-first century can so far be characterized as a period of contestation and polarization around climate change. The climate-change issue became politicized (McCright & Dunlap, Citation2011), leading to polarized debates between climate skeptics and the climate mainstream about whether or not humans are responsible for climate change. Climate skepticism has thereby profoundly obstructed collective action addressing climate change.

Rahmstorf (Citation2004) was the first to categorize and label forms of climate skepticism (Howarth & Sharman, Citation2015). The first category of this taxonomy consists of “trend sceptics” who deny that global warming exists. The second category comprises “attribution sceptics”, who accept the global warming trend, but do not hold humans responsible and attribute climate changes to natural causes. The last category involves “impact sceptics”, who think that global warming is harmless or even beneficial (Rahmstorf, Citation2004). While this taxonomy was innovative for its time, over the years others have reconceptualized climate skepticism (Hobson & Niemeyer, Citation2013; Howarth & Sharman, Citation2015), providing more detailed taxonomies of these groups (Akter et al., Citation2012; Capstick & Pidgeon, Citation2014; Doherty, Citation2009; Hobson & Niemeyer, Citation2013).

Recently, polarization dynamics around climate change have increasingly shifted from debates about the existence and anthropogenic causes of climate change to debates about proportionate climate solutions (Pearce et al., Citation2017; Tschötschel et al., Citation2020). This is why it seems timely to further our understanding of skepticism towards specific climate solutions that have garnered stark polarization. Building on Rahmstorf’s (Citation2004) taxonomy, Akter et al. (Citation2012) specified “mitigation skepticism”, which is about to what extent climate mitigation schemes are perceived to be effective. It focuses on the level of uncertainty that people experience about a certain policy to slow down climate change (Akter & Bennett, Citation2011). Congruently, Capstick and Pidgeon (Citation2014) coined the label “response skepticism”, referring to those who doubt their own efficacy of responding to climate change, or societal actors’ ability and willingness to do so. Yet, whereas “mitigation skepticism” focuses on uncertainty and “response skepticism” on individuals’ and society’s lack of efficacy, ability, or willingness, both forms do not address the role that values play in various forms of skepticism.

After all, a growing body of evidence demonstrates how actors’ values play an important role in climate attitudes and engagement (e.g., Corner et al., Citation2014; Van der Linden, Citation2015), predict attribution skepticism (Whitmarsh, Citation2011), people’s support for specific climate solutions (e.g., Jessup, Citation2010; Nilsson et al., Citation2004), and contestation around the implementation of technological climate solutions (Dignum et al., Citation2016; Milchram et al., Citation2018; Mouter et al., Citation2018). For example, de Groot et al., (Citation2013) found that people who hold altruistic and biospheric values positively related to the perceived risks of nuclear energy, while people holding egoistic values acknowledged the environmental benefits of this energy solution. In the current research, we argue that a new form of polarization is on the rise between the ones that either oppose or advocate for particular climate solutions. We coin this form “climate-solutions polarization”, referring to polarization dynamics around climate solutions as a product of divergent human value orientations.

We illustrate the existence of climate-solutions polarization using a case study on the biomass discourse in the Netherlands. Transitions to renewable energies form a cornerstone in processes of decarbonization of societies. Yet, public discourses about renewable energies are highly conflictual (Dehler-Holland et al., Citation2021; Isoaho & Karhunmaa, Citation2019). Among different types of renewable energy, biomass is particularly controversial among various societal groups including scientists. Conflicting discourses linked to distinct values, beliefs, and visions of future society have been found, for instance, to shape the biomass debate and policy decisions in the US (Mittlefehldt, Citation2016) and UK (Levidow & Papaioannou, Citation2016). However, we currently lack a systematic, inductive analysis that shows whether and how polarization dynamics in the biomass debate are related to actors’ divergent expressions of values.

Through an analytical framework inspired by Dryzek (Citation2013) and Carvalho (Citation2000), we present a discourse analysis of the Dutch news media debate about biomass as an energy source. Our investigation focusses on the period 2019–2021 as the news media debate peaked during this time frame. Discourse analysis has proven to be an effective method to distill actors’ discursive value expressions in environmental issues (Jessup, Citation2010), as discourses are about “a shared way of apprehending the world” (Dryzek, Citation2013). With a heated debate on the biomass issue (Strengers & Elzenga, Citation2020), the Netherlands is a relevant research context in this respect.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Value-based approaches to understanding climate-solutions polarization

In the context of climate change, the academic disciplines of social psychology and ethics (of technology) both have analyzed the role of values in contestation and polarization around climate solutions. Social psychological literature often relies on the work of Schwartz (Citation1992, p. 21), who defined values as “desirable goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in our lives.” Schwartz conceptualized values into a typology of ten clusters that can explain variation among the general public, including universalism, benevolence, conformity/tradition, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction. Later, Steg and de Groot (Citation2012) built onto this work by differentiating between hedonic, egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric values. The last three value clusters have frequently been used in survey studies investigating factors that can predict variations in climate-change risk perceptions. These studies show that, if individuals hold biospheric values, it is more likely that they have high climate-change risk perceptions (e.g., Van der Linden, Citation2015; Xie et al., Citation2019). Other studies suggest a relationship between individuals who hold traditional values (e.g., conformity, security; Schwartz, Citation1992) or individualistic and hierarchical values (Kahan et al., Citation2011, Citation2012) and their skepticism about the reality and seriousness of climate change. Overall, a significant body of social psychological research shows how self-transcendent values mostly predict engagement with environmental issues, as opposed to self-enhancing values predicting climate skepticism (Corner et al., Citation2014).

Ethicists studying contestation around the implementation of technological climate solutions often rely on the work of Van de Poel and Royakkers (Citation2011, p. 72), which defined values as “lasting convictions or matters that people feel should be strived for in general and not just for themselves to be able to lead a good life or to realize a just society.” They introduced the value hierarchy theory, which explains how (1) values translate into (2) norms, and subsequently into (3) technological design requirements. Research building upon this work applied and innovated this theory to understand contestation around shale gas (Dignum et al., Citation2016), smart grid systems (Milchram et al., Citation2018), and gas (Mouter et al., Citation2018) in the Netherlands.

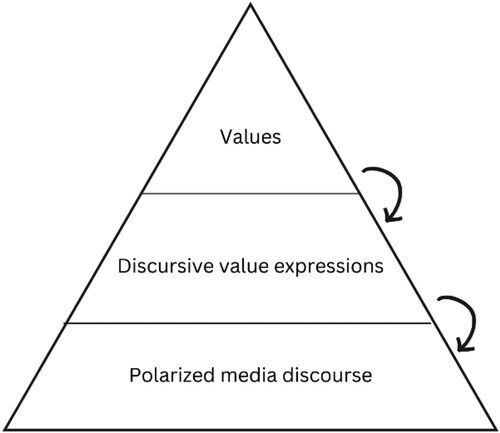

Both academic disciplines understand values as normative ideals, and often conceptually overlap in how they define (issue-specific) values (e.g., safety, environmental friendliness). However, both disciplines differ in that social psychologists aim to explain how these values shape climate attitudes, whereas ethicists strive to explain contestation around technologies. Remarkably, the communication discipline has not fully engaged with the question of how values explain polarized climate communication (but see e.g., Miller & Lellis, Citation2016). Therefore, by drawing on both the social psychology and ethics disciplines, we propose a hierarchical value structure for communication research that understands (1) values as higher-level ideals that provide guidance to life, which are translated into (2) discursive value expressions, that help to explain (3) polarized media discourse.

2.2. Value (expressions) and renewable energy discourses

A scientific consensus exists about the human nature of the climate problem and its severe consequences (IPCC, Citation2023), scientifically invalidating the arguments of trend skeptics, attributions skeptics, and impact skeptics. However, a scientific consensus on a precise roadmap for tackling the climate crisis in each country is lacking, meaning that societies can pursue different routes on how to reduce their carbon emissions. To illustrate, science offers no straightforward answer to how countries design their energy mix, having a wide range of options available including solar, wind, nuclear, hydropower, geothermal energy, fossil fuels, and biomass. Political decision-makers are also dependent on other factors, such as the local availability of energy sources, economic considerations, and public sentiment (Isoaho & Karhunmaa, Citation2019; Mussard, Citation2017).

The issue of climate change can be seen as a wicked problem, one for which a finite set of clear solutions is lacking. For climate change, possible solutions are “not true or false, but good or bad” (Peters, Citation2017, p. 388), meaning that choosing climate solutions is a moral decision (Markowitz & Shariff, Citation2012) guided by norms and values (Besio & Pronzini, Citation2014). The question, therefore, arises about which norms and values guide how climate solutions are perceived and, more importantly, provide an explanation for contestation and polarization dynamics (Bigl, Citation2017; Stauffacher et al., Citation2015; Teräväinen et al., Citation2011; Trisiah et al., Citation2022).

Indeed, ample evidence suggests that values do play an important role in energy discourses (e.g., Curran, Citation2012; Dehler-Holland et al., Citation2021; Miller & Lellis, Citation2016). For example, examining how audiences respond to value-based environmental marketplace advocacy of US fossil fuel industries (Miller & Lellis, Citation2016) revealed four central instrumental values: innovation, community, resilience, and patriotism, in addition to pragmatism as underlying terminal value. Partly in line with these values, positive newspaper coverage about renewable energy technologies in Germany has been linked to innovation, job creation, and industry leadership (Dehler-Holland et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, negative associations with renewable energy were mainly linked to cost-related issues (Dehler-Holland et al., Citation2021). While this research suggests some consistencies, comparison is hindered by different conceptualizations of values.

While specific types of (renewable) energy seem to elicit distinct sets of values, parallels between value expressions can be observed across energy types. Advocates of nuclear energy, for example, have been shown to mobilize dominant societal values such as national security, welfare, sovereignty, or competitiveness, which also explains partly diverging arguments in different countries (Teräväinen et al., Citation2011). Risks versus technological innovation and costs versus economic advantages comprise major frames linked to different sets of values that may be found in debates on nuclear energy as well as geothermal energy or fracking (Bigl, Citation2017; Stauffacher et al., Citation2015; Trisiah et al., Citation2022). Opposition to wind energy, in contrast, has been linked to place-based local values, often linked to a lack of trust in public institutions (Barry et al., Citation2008). Moreover, NIMBY (not in my backyard) arguments indicate a “cultural rationality”, that is, judgments based on personal, emotional, and value-based considerations as opposed to technical or quantifiable aspects (Barry et al., Citation2008; Fischer, Citation2004). Similarly, in local discussions about renewable energy in Canada, a divergence has been found between fact-claims used by government officials and norm-claims used by citizens who thereby introduce values into energy-related debates (Fast, Citation2013).

2.3. Discourses on forestry biomass

Biomass that is used for energy production includes various organic sources such as wood, crops grown for bioenergy production, and woody, agricultural or other organic residues or waste. Biomass power stations, however, predominantly use wooden pellets to produce electricity. Pellets are also used as complementary sources in coal-fired power stations. Due to large variations in ecosystems, material properties, local supply, need for transportation, and combustion technologies determining the efficiency and sustainability of forestry biomass as energy source is a complex and scientifically contested issue (IPCC, Citation2014). Nonetheless, the IPCC (Citation2014, Citation2023) voices concerns regarding possible negative climate, environmental, and socio-economic effects of large-scale bioenergy applications while considering options for sources based on low lifecycle emissions and certain local, small-scale applications. Inconclusive scientific evidence is furthered by differences in methodological approaches and research questions that may be influenced by public or private funding bodies (Berndes et al., Citation2016). An additional hurdle for the impact of science on public and political debates about biomass is the technical and methodological complexity of this research which does not easily translate into clear policy guidelines. This results in different interpretations, for instance, of the IPCC reports but also other studies by stakeholders with diverging interests.

To the best of our knowledge, with only one exception, media analyses of biomass energy discourses are scarce (Feldpausch-Parker et al., Citation2015), while a few more studies have investigated public and political discourses in different geographic regions (Fast, Citation2013; Levidow & Papaioannou, Citation2016; Mather-Gratton et al., Citation2021; Mittlefehldt, Citation2016). Overall, this research carves out biomass energy as a complex and contested issue. Diverging and dominant positions have changed over time and are context dependent. Looking at the public debate about biomass in the 1970s in the US, Mittlefehldt (Citation2016, p. 19) has identified a “paradox of local power” and related socio-political complexities as main barriers to the local implementation of biomass energy. While offering local independence to centralized power production, this autonomy was associated with environmental and health-related risks in addition to conflicts concerning land use, civil rights, and resource management. The prevalence of local considerations was also found in renewable-energy debates in rural eastern Canada (Fast, Citation2013) that showed an absence of global climate-change considerations but a strong focus on objections to the use of local biomass. In contrast, a study of the media coverage in the State of New York (US) from 2008 to 2013 found that positive perceptions concerning the potential of biomass for energy development and climate change mitigation prevailed with relatively few references to technical, political/legal, and economic risks (Feldpausch-Parker et al., Citation2015).

Beyond contextual differences, studies on biomass discourses indicate that the issue is characterized by a selective and strategic use of technical facts and strong influence of beliefs and cultural elements (Levidow & Papaioannou, Citation2016; Mittlefehldt, Citation2016). Based on her historical analysis, Mittlefehldt (Citation2016) concludes: “Navigating current tensions between renewable energy advocacy, environmental concerns, and social justice requires close attention to how and why different understandings arose, and how they have played out in public discourse” (p. 19).

In Europe in particular, forestry biomass is a contested issue that is characterized by interactions between the local, national, and EU level. A UK study has shown that lobbying narratives and activities can be successful in shaping national priorities and policies (Levidow & Papaioannou, Citation2016). By focusing on public arguments brought forward by main stakeholders that seek to influence EU policymaking, Mather-Gratton et al. (Citation2021) have identified three main storylines about biomass. First, “carbon neutrality” builds on the argument that, due to the carbon cycle of forest ecosystems, forestry biomass is carbon-neutral and does not have a negative climate impact. The second storyline “climate focused” offers more nuanced considerations concerning the premises under which biomass can effectively contribute to climate mitigation while also mitigating other environmental and societal risks. “Critical”, the third storyline, represents the opposing side of the opinion spectrum by clearly rejecting biomass as a renewable energy source. Arguments focus on negative climate effects of biomass and environmental and social risks including negative impacts on biodiversity, public health, and global social justice.

Importantly, these storylines can be placed on distinct positions on a value-based matrix that includes dimensions of sustainability (weak vs strong) and nature (anthropocentric vs biocentric). “Carbon neutrality” reflects an anthropocentric nature view and weak sustainability, “climate focused” a tendency toward an anthropocentric view and strong sustainability, and “critical” the strongest biocentric and sustainability views (Mather-Gratton et al., Citation2021). While this research has focused on values that are directly linked to climate change and the environment more generally, we argue that nature and sustainability views can only partially explain the different positions held in the debate. Therefore, studying climate-solutions polarization by taking the expression of divergent value orientations into account has the potential to deepen our understanding of how skeptical as well as advocating positions are rooted in more general underlying value systems.

2.4. Research context: biomass in the Netherlands

While biomass was included in the renewable energy directive of the European Union (EU) in 2009, the revised directive from December 2018 further refined criteria for sustainable forest biomass. Despite growing criticism, the European Parliament renewed the classification of biomass as renewable energy source in September 2022. Following European regulations, the Dutch energy transition heavily relied on biomass with first subsidies being issued in 2010 which since then have stimulated the construction of biomass power stations and the combustion of biomass in existing power plants. The Dutch climate agreement from 2019 confirmed the important role of biomass for the energy transition. Against the background of increasing criticism and debate, several reports were issued that have mapped stakeholder positions and possible solutions and political pathways (De Gemeynt, Citation2020; Strengers & Elzenga, Citation2020). As a response to the debate, in June 2021, the Dutch government has put any new subsidies for woody biomass on hold. Yet, with existing subsidies and over 200 biomass power stations in place, biomass remained the most important source of renewable energy in the country. While there was an overall share of renewable energy of 15% in 2022, biomass contributed 6% to the total use of energy (CBS, Citation2023). With a share of renewable energy sources below the European average (Eurostat, Citation2023), politically the use of biomass remains a corner stone for national climate goals and the goal to improving the country’s position within Europe.

2.5. Analytical framework

To understand which discursive value expressions underlie the polarized biomass media discourse (), the current research employed a discourse analysis. Different approaches to discourse analysis exist, making different ontological and epistemological assumptions, resulting in divergent methodological operationalizations (Feindt & Oels, Citation2005; Leipold et al., Citation2019). Dryzek (Citation2013, p. 8), defines discourse as “a shared way of apprehending the world”. A large number of studies have applied the social constructivist lens to study environmental issue debates, especially in the environmental policy realm. Our approach can be characterized as the “argumentative and deliberative” approach to discourse (Leipold et al., Citation2019, p. 449), inspired by Habermasian approaches to discourse (Citation1985). This approach assumes that there are competing meta-discourses about the environment, in this case, opponents and proponents of biomass as energy source.

We use the framework of Doulton and Brown (Citation2009), who in turn relied on the frameworks of Dryzek (Citation2013) and Carvalho (Citation2000) to investigate environmental discourse in UK newspapers. Later, van Eck & Feindt (Citation2022) slightly adapted the framework to study climate discourse in climate-skeptic and climate-activist blogs. Both studies identified prominent and competing discourses, by demonstrating how each newspaper and blogging camp discursively constructed a reality that (a) understood climate change and the environment differently; (b) made different assumptions about the natural relationships; (c) portrayed different actors as the heroes, villains, and victims; (d) deployed divergent rhetorical devices; and (e) made varying use of normativity.

We extend these studies by applying the analytical framework to the biomass debate, which is a more specific and polarized climate-solutions debate. The framework is applied in such a way that it is effective for analyzing discourses in newspaper articles, understanding the biomass phenomenon, and enabling us to identify the discursive value expressions present in the discourse. The first four dimensions relate to Dryzek’s (Citation2013) framework, and the last three dimensions to Carvalho’s (Citation2000) framework (see and for examples):

Basic entities recognized or constructed. The ontology of a discourse refers to how the biomass phenomenon is understood, the authority given to different sources of information, and the scale of the discourse (i.e., local, national, international).

Assumptions about natural relationships. The processes and consequences of utilizing biomass, including the production, transportation, and combustion in biomass power stations.

Representations of agents. The key actors represented in the discourse.

Key metaphors and other rhetorical devices. Arguments to convince readers by putting a situation in a particular light, including value judgments that possibly evoke emotional responses.

Normative judgments. Arguments that explicitly propose what should be done and by whom.

The first three dimensions allow us to understand how various actors understand biomass, whereas the latter two enable us to inductively identify which discursive value expressions drive polarization around biomass as an energy source. The fourth dimension focuses on implicit discursive value expressions, by analyzing how language is used to construct a worldview that aligns with the cultural worldviews and ideological viewpoints of the communicator (Carvalho, Citation2000). The fifth dimension focuses on explicit discursive value expressions, by analyzing the arguments that provide explicit guidance to life.

3. Methodology

The following sections introduce the research design, sampling design of the newspapers and articles, and the coding analysis. The Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences of the University of Amsterdam provided ethical approval for this study (2022-CC-15231).

3.1. Data collection

Six major Dutch national newspapers were selected, reflecting the ideological spectrum of the Dutch media landscape. Trouw, NRC Handelsblad (NRC), and De Volkskrant are considered to be quality newspapers, Algemeen Dagblad (AD) and De Telegraaf as tabbloids, and Het Financieele Dagblad (FD) as a financial newspaper. From the Nexis Uni database, we collected all newspaper articles that included the keywords “biomassa” or “bio-energie” in the title and at least three times in the entire text. It appeared that there was a significant peak in news attention between 2019 and 2021, which signals a critical discourse moment for the biomass debate (Carvalho & Burgess, Citation2005). Hence, we collected the 269 articles that were published during this time period. To validate that the included articles were indeed about the biomass debate and not about (un)related themes such as biomass as a resource for biofuels or other goods or materials, we reviewed each article manually. To ensure the feasibility of the discourse analysis and effectively capture the primary discussions within the broader media discourse during the selected period, our approach entailed examining the first article published by each newspaper on a monthly basis. This sampling design resulted in a final dataset of 108 articles. shows how many articles from each newspaper were included in the final dataset.

Table 1. Sample overview.

3.2. Data analysis

The first two authors of the current research engaged in an iterative process of coding in the collaborative online version of ATLAS.ti (version 23). The analysis was restricted to written text and was both deductive and inductive. The dimensions of the analytical framework represented the code groups (deductive element) and, within these categories, we inductively identified the codes representing the several analytical dimensions. For the first analytical dimension (ontology), the unit of analysis was the entire article, and the other dimensions were coded at sentence level. First, both coders coded the same five articles, compared codes, and finetuned the codebook. Subsequently, this process was repeated with the same five articles and five additional articles. When 25 articles were coded together and agreement was reached about how to approach the coding process, both coders continued coding separate articles in an iterative manner. Articles were assigned alternately, to ensure that both coders were immersed in the overall discourses. In between, coders met to discuss coding issues that were noted down in memos and to further refine, merge, and specify codes. When the complete dataset was coded, both coders revisited the articles coded by the other to ensure coherency. After eleven intermediate rounds between coders, the codebook was finalized, and all articles were coded (see Supplemental Materials). Overall, the debate was found to be divided into an advocacy and an opposition discourse.

Finally, the discursive value expressions underlying the polarized discourse were identified in three steps. First, during the coding process, the researchers constantly discussed their developing ideas over the course of a few months and noted these down in online memos (i.e., memo-writing for reflexivity purposes; Morgan & Nica, Citation2020). In step 2, all of the coded data was reviewed, and the most dominant themes were identified and presented in a table with the results per dimension (7 themes in the advocacy discourse and 5 themes in the opposition discourse). In step 3, the discursive value expressions were identified with a combination of inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning (Bryant & Charmaz, Citation2019). The codes of dimensions 4 and 5 were critically reviewed to identify indications of discursive value expressions (inductive element). This process was inspired by earlier research that defined values (deductive element; e.g., Schwartz, Citation1992). Some of the themes were merged with other themes (e.g., “stop subsidies” theme was incorporated in the “climate emergency”, “loss of biodiversity”, and “health and safety” themes) and resulted in three novel discursive value expressions per discourse (abductive element; see Supplemental Material for detailed discourse overview). It should be noted that findings from previous stakeholder analyses in the Netherlands (De Gemeynt, Citation2020; Strengers & Elzenga, Citation2020) were not reviewed before data analysis to avoid preemptive researcher biases.

4. Results

The following section discusses how climate security, ecological benevolence, and local security are three distinct discursive value expressions underlying the discourse of the opposition. Subsequently, the results of the advocacy discourse will be discussed, pointing to climate achievement, technological security, and economic security as underlying discursive value expressions. Finally, we explore how facts are constructed by both sides.

For more insight into how the discourses were distributed across the newspapers, please see the Supplemental Materials. Here we present distributional overviews across newspapers of the identified basic entities, the geographical scales, and rhetoric and normative judgments around a critical discourse moment: the abolishment of subsidies.

4.1. Opposition discourse

The opposition discourse was the most dominant discourse, that also gained more prominence over the course of time. This side of the debate consists of scientists, environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs), activists, and local citizens. It assumed that biomass would be detrimental to climate change, other environmental issues, and public health. The discourse was furthermore characterized by negative, emotional, and distrustful rhetoric. The opposition was clear in their demands, which left no room for biomass as an energy solution. Please see for a detailed overview of the value expressions and the corresponding opposition discourse. While we observed three distinct value expression, each linking to underlying human values in a different way, it is important to emphasize that these three sub-discourses were largely represented by the same actor groups and thus reinforced each other leading to an interconnected and inherently consistent opposition discourse.

Table 2. Exemplary overview of the discursive expression of values of the opposition discourse.

4.1.1. Climate security

The ecologist [Louise Vet], emeritus professor at Wageningen University, sees the CBS [Statistics Netherlands] figures as sad proof that things are going completely in the wrong direction with biomass. André Faaij's [Professor Energy System Analysis] reasoning that biomass works according to the cycle principle is dismissed by Vet as a ‘green dream’. De Telegraaf, 3 December 2021

4.1.2. Ecological benevolence

“An ecological disaster,” says Whitehurst [NGO Healthy Gulf]. “It's bad for biodiversity, for wildlife, and for water quality. In addition, the risk of flooding is increasing.” Algemeen Dagblad, 26 October 2019

4.1.3. Local security

Local governments are rolling out the red carpet, handing out subsidies, building rail links and – critics say – turning a blind eye to environmental standards, causing residents to suffer from toxic substances from the factory. Algemeen Dagblad, 26 October 2019

4.2. Advocacy discourse

The advocacy discourse can be considered a response to the opposition as many of the critical arguments are argued against. Overall, this results in a more positive assumption about biomass and, hence, a strong focus on arguments about the sustainability of biomass and contribution to the energy transition. However, as opposed to the clearly rejecting tone of the opposition, advocates also stress the complexity of the issue by weighing both advantages and disadvantages of biomass, discussing the dependencies of sustainable biomass on production and transportation, and/or acknowledging the absence of a clear scientific consensus. In contrast to the affective rhetoric used by the opposition, seemingly rational arguments prevail where biomass is presented as a no-brainer, a matter of logical reasoning and complexity, and scientifically validated (see ). In comparison to the opposition discourse, the advocacy discourse is less consistent and slightly more fragmented, which might be explained by diverging interests between scientific, industry, and political actors.

Table 3. Exemplary overview of the discursive expression of values of the advocacy discourse.

4.2.1. Climate achievement

Both [biomass] power plants will be climate negative according to RWE [multinational energy company], which can make the entire Dutch energy sector climate neutral in a decade argues RWE executive Roger Miesen. De Volkskrant, 28 August 2021

4.2.2. Technological security

It can be a prelude to energy sources that can save the climate toward 2050, such as geothermal energy, wind parks and solar cells. Trouw, 7 May 2019

4.2.3. Economic security

If people say that we cut down primeval forests to produce electricity, we need to explain that this is not the case. Het Financieele Dagblad, 15 February 2020

4.3. Construction of facts

This section explores the interrelations of the various value expressions, focusing on a key question of the biomass discourse concerning the extent to which biomass can be considered a carbon neutral energy source. As aforementioned, it is important to emphasize that there is no clear scientific agreement on this issue. Accordingly, opposition and advocacy relate differently to facts and science in their arguments and these differences, in turn, relate to the different value expressions.

Louise Vet and Martijn Katan, two very prominent science actors from the opposition discourse, fiercely reject carbon neutrality: “The short carbon cycle is an illusion. It has been scientifically proven that using forestry biomass instead of fossils for energy increases the CO2 in the atmosphere for more than a hundred years” (Trouw, 10 October 2020). This showcases the expression of climate security using strong rhetoric (“illusion”) and implying scientific consensus. As a direct response, Bart Strengers, a science representative of the advocacy discourse, counters by taking a climate achievement perspective: “About this point – carbon debt – tens of scientific publications show that this effect strongly depends on how forests are managed. There are examples of existing forest management practices […] revealing net retention of CO2 since decennia” (Trouw, 14 October 2020). Here, a reference to specific scientific findings is made emphasizing that no generalizing conclusion about the carbon cycle of biomass can be made. Acknowledging exactly this dependency, the opposition discourse further focuses on unsustainable forestry practices and the use of logged wood from Eastern Europe and the U.S. in Dutch biomass stations. “Numbers show that between 2013 and 2017 eight thousand football fields have been cut down” (AD, 21 September 2021) a political actor remarked as part of the opposition discourse supporting ecological benevolence with statistics. Advocacy actors, in contrast, emphasize sustainable practices as exemplified by an industry representative: “The criteria that biomass has to meet in the Netherlands are considered the strictest in the world” (de Volkskrant, 28 August 2021). This illustrates expressions of economic security and climate achievement, underlining the pioneering position of the country. These examples show how actors from both sides actively construct facts congruent with their discursive values expressions.

5. Discussion

Polarization dynamics are shifting from debates about the reality and severity of climate change to debates about proportionate climate-change solutions. In the current paper, we propose taking a value-based approach to understanding climate-solutions polarization. As a case study, we analyzed media discourse about the biomass debate in the Netherlands between 2019 and 2021. Overall, we inductively identified stark polarization between the opposition and advocates of biomass as an energy source. The discursive value expressions that underlie the opposing side's discourse comprise climate security, ecological benevolence, and local security. The advocacy side's discursive reality is underpinned by the value expressions of climate achievement, technological security, and economic security. Overall, the current study contributes to our understanding of how distinct value expressions can explain new polarization dynamics around climate solutions, and therewith it builds on earlier research investigating climate skepticism and polarization (see e.g., Akter et al., Citation2012; Capstick & Pidgeon, Citation2014; Doherty, Citation2009; Hobson & Niemeyer, Citation2013; Rahmstorf, Citation2004) and the role of values in climate engagement (Corner et al., Citation2014; Jessup, Citation2010; Nilsson et al., Citation2004; Van der Linden, Citation2015; Whitmarsh, Citation2011) and contestation around energy technologies (Dignum et al., Citation2016; Milchram et al., Citation2018; Mouter et al., Citation2018).

First, it is striking that four of the six value expressions are about security, highlighting different risks related to climate change (i.e., environmental, health, technological, and economic risks). This finding shows how the biomass debate represents an intra-value conflict, in which actors have different ideas about how one particular value is best served (Dignum et al., Citation2016), in this case security. The identified value expressions echo previous research on discourses about energy technologies (e.g., Curran, Citation2012; Mouter et al., Citation2018). While previous studies on biomass discourses have linked social and environmental risks to opposition discourses (Mather-Gratton et al., Citation2021; Mittlefehldt, Citation2016), our findings emphasize that risk as a multifaceted security value also forms the basis of some advocacy discourses (Dignum et al., Citation2016). This finding underlines how climate change is a wicked issue (Peters, Citation2017), impacting society in all its facets (IPCC, Citation2023), and putting the harmony, safety, and stability of society at play (Schwartz, Citation2012, p. 6). Schwartz (Citation2012) notes that some security values serve individual interests and some wider group interests that one needs to feel part of. This notion implies that societies need to start reflecting on which of these security values are the ones that need to matter in the decision-making process about the adoption of particular climate solutions.

Since security more broadly is apparently a value that multiple stakeholders share, it also provides a communication opportunity. Previous research shows how climate narratives that are geared to the public's values are generally more effective, meaning that campaigners can develop narratives that speak to the security values of society at large (Corner & Clarke, Citation2017). However, this communication strategy also warrants attention. Security values are about the preservation and protection of existing social arrangements that provide certainty, order, and harmony (Schwartz, Citation1992; Citation2012). Yet, it is a fact that climate change will change the social arrangements in societies undoubtedly (IPCC, Citation2023), meaning that potentially appealing to values that embrace change (i.e., stimulation, self-direction) is more effective for preparing and transforming societies into climate-resilient ones.

The second opposition value expression of ecological benevolence represents an eco-centric perspective, which, in contrast to anthropocentrism, emphasizes the intrinsic value of nature and human dependency on the natural environment (e.g., Whyte & Lamberton, Citation2020). Actors showing benevolence toward and thereby giving voice to the more-than human world (Freeman et al., Citation2011) in the Dutch biomass debate frequently refer to environmental risks and negative ecological consequences of biomass production that thus are associated with another aspect of security – environmental security. While security may, again, serve as underlying value that may help to find common ground across actors and positions, the contrast between social (e.g., economic) and environmental security may pose a challenge as long as they are linked to opposing worldviews, such as anthropocentrism versus ecocentrism. To overcome this contrast and related conflicts it is therefore important to go beyond value orientations and address these overarching worldviews. This echoes recent calls for a need to discuss and change toward more radical, transformative worldviews which coincide with strong sustainability perceptions (Demos, Citation2017; Hickel & Kallis, Citation2020; Kemper et al., Citation2019). From the perspective of an integrative or transformative worldview, it would be vital that ecological benevolence and security are not just niche perspectives reserved to environmental activists, but rather receive a central position when weighing the advantages and disadvantages of forestry biomass.

Another important finding is that the current research shows how both the opposition and advocacy sides have scientists on their sides, deploying rhetoric about how their science is clear proof of their position, whilst dismissing the other side's scientific evidence. Whilst the advocacy camp's scientists mostly deployed dry and factual rhetoric, the opposition camp's scientists were considerably more negative and emotional in their rhetoric. Schwartz (Citation2012, p. 3) explains how “when values are activated, they become infused with feelings”, which could imply that scientists on the opposing side are less focused on downplaying how their values affect research interpretation, while the other side is more comfortable with science communication perceived as “rational” and “objective”. Arguably, the opposition was more effective in shaping political discourse in the Dutch biomass debate, as for example, over the course of time politicians became more critical of biomass and subsidies were phased out.

This finding demonstrates how values play an important role in the appraisal of scientific evidence and science communication about the results. Therewith, the study contributes to a stream in the philosophy of science that argues that the value-free ideal of science should be rejected, and that reflection is needed on which values may play a role in which parts of science. For example, scientists could explicate the social, ethical, and political values that inform their research questions, possibly together with policymakers and the public. Further, in the valorization of their results, scientists need to be transparent about the values that informed their research questions and interpretation of the results. In this case, an analytic-deliberative process amongst stakeholders could be organized that provides a holistic risk assessment of biomass (e.g., Douglas, Citation2009; Elliott, Citation2022).

Overall, the current research explained how distinct value expressions explain polarization around biomass as a climate solution in Dutch media discourse. While climate change polarization could be a sign of a healthy functioning democracy with a plethora of opinions, extreme polarization is undesirable. If groups in society lose the ability to have a dialogue with each other to create mutual understanding, it leads to incomprehension and in the worst-case extremism and inaction on climate change (van Eck, Citation2021). Climate change polarization could be reduced if all groups make a concerted effort to understand each other's values and worldviews, and tailor their communication to these values (Corner et al., Citation2014).

For future research, the theoretical framework (Doulton & Brown, Citation2009; van Eck & Feindt, Citation2022) was successfully extended to the issue of biomass, as it allowed for identifying the underlying discursive value expressions driving the polarization. Hence, future research could apply the framework to other cases of climate-solutions polarization, such as flying and meat consumption. However, as with any research, there are limitations. First, we looked at one country, during a specific time period, which means that we do not know if the values and discourse that we identified are transferable to other contexts. Second, discourse analysis is prone to researcher biases. We have tried to limit these effects by implementing multiple quality checks (i.e., iterative, memo-writing, reflexivity), but it goes without saying that it has impacted the research in unanticipated ways. Third, our analysis was limited to media discourse. Therefore, an interesting new research direction would be comparing our results to both political and scientific discourse, which could uncover to what extent journalistic and editorial decisions played a role in the construction of the discourse.

Supplemental Materials.docx

Download MS Word (27.6 KB)Supplemental Material Codebook.xlsx

Download MS Excel (18.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akter, S., & Bennett, J. (2011). Household perceptions of climate change and preferences for mitigation action: The case of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme in Australia. Climatic Change, 109(3–4), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10584-011-0034-8/METRICS

- Akter, S., Bennett, J., & Ward, M. B. (2012). Climate change scepticism and public support for mitigation: Evidence from an Australian choice experiment. Global Environmental Change, 22(3), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2012.05.004

- Barry, J., Ellis, G., & Robinson, C. (2008). Cool rationalities and hot air: A rhetorical approach to understanding debates on renewable energy. Global Environmental Politics, 8(2), 67–98. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2008.8.2.67

- Berndes, G., Abt, B., Asikainen, A., Cowie, A., Dale, V., Egnell, G., Lindner, M., Marelli, L., Paré, D., & Pingoud, K. (2016). Forest biomass, carbon neutrality and climate change mitigation. From Science to Policy 3. European Forest Institute. https://efi.int/sites/default/files/files/publication-bank/2018/efi_fstp_3_2016.pdf

- Besio, C., & Pronzini, A. (2014). Morality, ethics, and values outside and inside organizations: An example of the discourse on climate change. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1641-2

- Bigl, B. (2017). Fracking in the German press: Securing energy supply on the eve of the ‘Energiewende’ – a quantitative framing-based analysis. Environmental Communication, 11(2), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2016.1245207

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (Eds.). (2019). The SAGE handbook of current developments in grounded theory. Sage.

- Capstick, S. B., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2014). What is climate change scepticism? Examination of the concept using a mixed methods study of the UK public. Global Environmental Change, 24(1), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2013.08.012

- Carvalho, A. (2000). Discourse analysis and media texts: A critical reading of analytical tools. ‘International Conference on Logic and Methodology’, RC 33 Meeting (International Sociology Association).

- Carvalho, A., & Burgess, J. (2005). Cultural circuits of climate change in U.K. broadsheet newspapers, 1985–2003. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 25(6), 1457–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00692.x

- CBS [Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics]. (2023, June 1). Aandeel hernieuwbare energie in 2022 toegenomen naar 15 procent [Percentage of renewable energy in 2022 increased to 15 percent; Web page]. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2023/22/aandeel-hernieuwbare-energie-in-2022-toegenomen-naar-15-procent

- Corner, A., & Clarke, J. (2017). Talking Climate: From Research to Practice in Public Engagement. Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46744-3

- Corner, A., Markowitz, E., & Pidgeon, N. (2014). Public engagement with climate change: The role of human values. WIREs Climate Change, 5(3), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.269

- Curran, G. (2012). Contested energy futures: Shaping renewable energy narratives in Australia. Global Environmental Change, 22(1), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.11.009

- De Gemeynt. (2020). Biomassa in perspectief. Joint fact finding biomassa—Een zoektocht naar feiten in een verhitte discussie [Biomass in perspective: Joint fact finding biomass: A search for facts in a heated debate]. https://www.gemeynt.nl/projecten-publicaties

- de Groot, J. I. M., Steg, L., & Poortinga, W. (2013). Values, perceived risks and benefits, and acceptability of nuclear energy. Risk Analysis, 33(2), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1539-6924.2012.01845.X

- Dehler-Holland, J., Schumacher, K., & Fichtner, W. (2021). Topic modeling uncovers shifts in media framing of the German Renewable Energy Act. Patterns, 2(1), 100169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2020.100169

- Demos, T. J. (2017). Against the Anthropocene. Sternberg Press.

- Dignum, M., Correljé, A., Cuppen, E., Pesch, U., & Taebi, B. (2016). Contested technologies and design for values: The case of shale gas. Science and engineering Ethics, 22(4), 1171–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9685-6

- Doherty, P. (2009). Copenhagen and beyond: Sceptical thinking. The Monthly. https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2009/november/1266188171/peter-doherty/copenhagen-and-beyond#mtr

- Douglas, H. (2009). Science, policy, and the value-free ideal (H. Douglas, Ed.). University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Doulton, H., & Brown, K. (2009). Ten years to prevent catastrophe? Discourses of climate change and international development in the UK press. Global Environmental Change, 19(2), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.004

- Dryzek, J. S. (2013). The politics of earth: Environmental discourses. Oxford University Press.

- Elliott, K. C. (2022). Values in science. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009052597

- European Commission. (2021). Citizen support for climate action. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/citizens/citizen-support-climate-action_en

- Eurostat. (2023). Renewable energy statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Renewable_energy_statistics

- Fast, S. (2013). A Habermasian analysis of local renewable energy deliberations. Journal of Rural Studies, 30, 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.12.004

- Feindt, P. H., & Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339638

- Feldpausch-Parker, A. M., Burnham, M., Melnik, M., Callaghan, M. L., & Selfa, T. (2015). News media analysis of carbon capture and storage and biomass: Perceptions and possibilities. Energies, 8(4), 3058–3074. Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/en8043058

- Fischer, F. (2004). Citizens and experts in risk assessment: Technical knowledge in practical deliberation. TATuP - Zeitschrift für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Theorie und Praxis, 13(2), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.14512/tatup.13.2.90

- Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M., & Bexell, S. M. (2011). Giving voice to the “voiceless”. Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2010.540136

- Habermas, J. (1985). The Theory of Communicative Action: Volume 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society (Vol. 1). Beacon Press.

- Hickel, J., & Kallis, G. (2020). Is green growth possible? New Political Economy, 25(4), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

- Hobson, K., & Niemeyer, S. (2013). “What sceptics believe”: The effects of information and deliberation on climate change scepticism. Public Understanding of Science, 22(4), 396–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662511430459

- Howarth, C. C., & Sharman, A. G. (2015). Labeling opinions in the climate debate: A critical review. WIREs Climate Change, 6(2), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.332

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014 - mitigation of climate change. Working Group III Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- IPCC. (2023). Synthesis report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report: Summary for policymakers.

- Isoaho, K., & Karhunmaa, K. (2019). A critical review of discursive approaches in energy transitions. Energy Policy, 128, 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.01.043

- Jessup, B. (2010). Plural and hybrid environmental values: A discourse analysis of the wind energy conflict in Australia and the United Kingdom. Environmental Politics, 19(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010903396069

- Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H., & Braman, D. (2011). Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. Journal of Risk Research, 14(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

- Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L. L., Braman, D., & Mandel, G. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 2(10), 732–735. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1547

- Kemper, J. A., Hall, C. M., & Ballantine, P. W. (2019). Marketing and sustainability: Business as usual or changing worldviews? Sustainability, 11(3), 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030780

- Leipold, S., Feindt, P. H., Winkel, G., & Keller, R. (2019). Discourse analysis of environmental policy revisited: Traditions, trends, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462

- Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., Carman, J., Neyens, L., Marlon, J., Lacroix, K., & Goldberg, M. (2021). Climate change in the American mind, September 2021. Yale University and George Mason University. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/climate-change-in-the-american-mind-september-2021/

- Levidow, L., & Papaioannou, T. (2016). Policy-driven, narrative-based evidence gathering: UK priorities for decarbonisation through biomass. Science and Public Policy, 43(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scv016

- Markowitz, E., & Shariff, A. (2012). Climate change and moral judgement. Nature Climate Change, 2(4), 243–247. https://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v2/n4/abs/nclimate1378.html

- Mather-Gratton, Z. J., Larsen, S., & Bentsen, N. S. (2021). Understanding the sustainability debate on forest biomass for energy in Europe: A discourse analysis. PLoS One, 16(2), e0246873. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246873

- McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001-2010. The Sociological Quarterly, 52(2), 155–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

- Milchram, C., Hillerbrand, R., van de Kaa, G., Doorn, N., & Künneke, R. (2018). Energy justice and smart grid systems: Evidence from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Applied Energy, 229, 1244–1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.08.053

- Miller, B. M., & Lellis, J. (2016). Audience response to values-based marketplace advocacy by the fossil fuel industries. Environmental Communication, 10(2), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.993414

- Mittlefehldt, S. (2016). Seeing forests as fuel: How conflicting narratives have shaped woody biomass energy development in the United States since the 1970s. Energy Research & Social Science, 14, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.023

- Morgan, D. L., & Nica, A. (2020). Iterative thematic inquiry: A new method for analyzing qualitative data. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940692095511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920955118/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_1609406920955118-FIG1.JPEG

- Mouter, N., de Geest, A., & Doorn, N. (2018). A values-based approach to energy controversies: Value-sensitive design applied to the Groningen gas controversy in the Netherlands. Energy Policy, 122, 639–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.08.020

- Mussard, M. (2017). Solar energy under cold climatic conditions: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 74, 733–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.009

- Nilsson, A., von Borgstede, C., & Biel, A. (2004). Willingness to accept climate change strategies: The effect of values and norms. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVP.2004.06.002

- Pearce, W., Grundmann, R., Hulme, M., Raman, S., Hadley Kershaw, E., & Tsouvalis, J. (2017). Beyond counting climate consensus. Environmental Communication, 11(6), 723–730.

- Peters, B. G. (2017). What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Policy and Society, 36(3), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1361633

- Rahmstorf, S. (2004). The climate sceptics. In Munich Re (Ed.), Weather catastrophes and climate change – is there still hope for us? (pp. 76–83). http://www.pik-potsdam.de/~stefan/Publications/

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

- Stauffacher, M., Muggli, N., Scolobig, A., & Moser, C. (2015). Framing deep geothermal energy in mass media: The case of Switzerland. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 98, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.05.018

- Steg, L., & de Groot, J. L. M. (2012). Environmental values. In S. D. Clayton (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology (pp. 81–92). Oxford Library of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199733026.013.0005.

- Strengers, B., & Elzenga, H. (2020). Beschikbaarheid en toepassingsmogelijkheden van duurzame biomassa. Verslag van een zoektocht naar gedeelde feiten en opvattingen [Availability and application possibilities of sustainable biomass: Report of a search for shared facts and opinions]. https://www.pbl.nl/publicaties/beschikbaarheid-en-toepassingsmogelijkheden-van-duurzame-biomassa-verslag-van-een-zoektocht-naar-gedeelde-feiten

- Teräväinen, T., Lehtonen, M., & Martiskainen, M. (2011). Climate change, energy security, and risk—debating nuclear new build in Finland, France and the UK. Energy Policy, 39(6), 3434–3442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.03.041

- Trisiah, A., de Vries, G., & de Bruijn, H. (2022). Framing geothermal energy in Indonesia: A media analysis in a country with huge potential. Environmental Communication, 16(7), 993–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2144403

- Tschötschel, R., Schuck, A., & Wonneberger, A. (2020). Patterns of controversy and consensus in German, Canadian, and US online news on climate change. Global Environmental Change, 60, 101957.

- Van de Poel, I., & Royakkers, L. (2011). Ethics, technology, and engineering: An introduction. John Wiley & Sons.

- Van der Linden, S. (2015). The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVP.2014.11.012

- van Eck, C. W. (2021). Opposing positions, dividing interactions, and hostile affect: A multi-dimensional approach to climate change polarization in the blogosphere. Wageningen University. https://doi.org/10.18174/542725

- van Eck, C. W., & Feindt, P. H. (2022). Parallel routes from Copenhagen to Paris: Climate discourse in climate sceptic and climate activist blogs. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 24(2), 194–209.

- Whitmarsh, L. (2011). Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 690–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2011.01.016

- Whyte, P., & Lamberton, G. (2020). Conceptualising sustainability using a cognitive mapping method. Sustainability, 12(5), 1977, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051977

- Xie, B., Brewer, M. B., Hayes, B. K., McDonald, R. I., & Newell, B. R. (2019). Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101331, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101331. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272494419300234