ABSTRACT

Based on Moral Foundations Theory, message framing, and the Sacred Values Protection Model, this pre-registered experiment tested the effects of five different moral frames in climate change messages among N = 715 U.S. adults. Contrary to prior research, we did not find evidence that matching a message’s moral frame to individuals’ endorsements of moral foundations enhances intended positive outcomes, including perceived message effectiveness (PME) and policy support. However, a moral frame mismatch did reduce PME. Also contrary to scholarly warnings about potential negative effects of moralized communication, we did not find evidence for unintended consequences of moral frame matching for outgroup perceptions. Political ideology did moderate the effect of moral framing on desired social proximity (i.e. willingness to interact with moral outgroup members) and perceived message effectiveness. Our findings raise questions about the benefits of using moral frames that invoke only one moral foundation in climate change communication.

A recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report stated that “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land” (IPCC, Citation2021, p. 4). While it is important for major stakeholders like governments and businesses to engage with climate action, it is also critical to cultivate “citizen engagement” (p. 9) to bring about systemic solutions (IPCC, Citation2023). However, there are numerous communication challenges facing environmental advocates. Climate change is highly politicized, leading individuals to make quick judgments about the topic based on their political beliefs (Walsh & Tsurusaki, Citation2018). Liberals in the U.S are more likely to acknowledge that anthropogenic climate change is happening and are more concerned than conservatives (Leiserowitz et al., Citation2021a). This partisan divide is also evident in support for climate-friendly policies (Leiserowitz et al., Citation2021b), raising the question of which messaging strategies can bridge this divide and rally support across the political spectrum.

A common approach to communicating urgency around climate action involves using moral terms (Malier, Citation2019). Moral framing, or an emphasis on values and moral concerns (Kreps & Monin, Citation2011), may motivate individuals to engage in greater pro-environmental action, particularly when the moral frame matches moral convictions held by audience members (Day et al., Citation2014; Salomon et al., Citation2017; Wolsko et al., Citation2016). However, the climate crisis is often framed as a moralized issue of harm and care (Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013), primarily appealing to liberal value systems. This is a missed opportunity to appeal to conservative values, as research has suggested that couching environmental arguments in the language of morals that matter to conservatives is a promising strategy (Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Hurst & Stern, Citation2020; Wolsko et al., Citation2016).

Many extant studies focus on intended persuasive outcomes of moral framing (e.g. Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Luttrell & Trentadue, Citation2023; Hurst & Stern, Citation2020; Wolsko et al., Citation2016). However, scholars have stressed the importance of studying both intended and unintended outcomes of persuasive messaging (Cho & Salmon, Citation2007). Moral framing may yield unintended outcomes in the form of fueling negative sentiment towards outgroups because moral conviction can drive stigmatization of those with different moral beliefs (Täuber, Citation2018), reduced willingness to compromise (Ryan, Citation2017; Kodapanakkal et al., Citation2022), and increased defensive reactions to messages (Täuber et al., Citation2015). Specifically, we consider how moral framing that matches audience members’ beliefs may make moral concerns more salient, thus leading to outrage and a desire to distance oneself from outgroups. Because of the dire need for climate action, it is essential to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of moral framing. This study tests the effects of moral frames, based on Moral Foundations Theory (MFT; Graham et al., Citation2013), in persuasive climate messages. The present work is unique in that it tests messages based on five moral foundations rather than combining multiple moral foundations into one or two messages (e.g. Wolsko et al., Citation2016) or collapsing responses to distinct moral frames for analysis (e.g. Huang et al., Citation2022), as much previous research has done, thus allowing us to distinguish effects of using each foundation in a message. Moreover, we measure participants’ moral beliefs rather than relying on political ideology as a proxy, as is common in other research. Finally, we examine both favorable intended outcomes, such as climate policy support, alongside unfavorable unintended outcomes, such as negative feelings toward outgroups.

Literature review

Beliefs about some issues may be viewed as personal preferences, while others are seen as serious matters of right and wrong. In the latter case, once a topic has been moralized, moral convictions often evoke strong emotions and leave individuals unwilling to consider or tolerate alternative views (Skitka et al., Citation2021). Moralization is “the acquisition of moral qualities by objects or activities that previously were morally neutral” (Rozin et al., Citation1997, p. 67). Scholars have noted a growing propensity for some “individuals and governments” (p. 454) to view climate change as a moralized issue (Täuber et al., Citation2015). For some, such moral thinking may stem from the reality that climate change threatens people’s rights to health and wellbeing (Bell, Citation2013) and that impacts such as air pollution and extreme weather events disproportionately affect countries less responsible for producing greenhouse gasses (Patz et al., Citation2014). For others, climate mitigation and care for the environment may be motivated by purity-related religious beliefs (Schuldt et al., Citation2017). In order to encourage pro-environmental behaviors to address the threats posed by climate change, communicators may therefore choose to make persuasive arguments with morally framed messages.

Moral framing and moral foundations theory

Message framing is “select[ing] some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (Entman, Citation1993, p. 52). For example, climate action could be framed as improving people’s lives and making social progress, or as an opportunity for economic growth through green jobs (Nisbet, Citation2009). Consequently, framing activates existing schemas which influence how audiences perceive, discern, and process information (Fiske & Taylor, Citation1991). Framing research falls into two broad directions: emphasis framing (selecting aspects of an issue to emphasize or omit) and equivalent framing (presenting the same information in different ways) (Cacciatore et al., Citation2016).

Moral framing is a type of emphasis framing. Voelkel and Feinberg (Citation2018) define moral reframing as “framing arguments that favor one’s own political stance but grounding these arguments in moral terms that appeal to the moral values of those on the other side of the political spectrum” (p. 918). Focusing a message generally on moral arguments can reduce message resistance among people with a strong moral basis for their stance on an issue (Luttrell et al., Citation2019). When considering more specific types of moral framing, scholars often use Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) as a theoretical lens to guide the particular moral frames they test (e.g. Wolsko et al., Citation2016).

According to MFT, morality is informed by multiple values, these values have evolutionary roots that are then further molded by culture (i.e. morality is innate and learned), and these values are often enacted in a primarily intuitive way rather than through critical thought (Graham et al., Citation2013). MFT posits that there are (at least) five primary bases (or foundations) for moral beliefs. Moral foundations are deeply held intuitions, shaped by culture, that came about to help human communities overcome challenges (Graham et al., Citation2013). The care foundation involves showing care for others to avoid harm. Fairness concerns motivate people to cooperate so that everyone gets what they deserve from a relationship or situation. The ingroup foundation posits that people are devoted to and willing to sacrifice for in-groups. Authority involves respect for and adherence to hierarchies, with respect shown to leaders and institutions. Finally, the purity foundation states that people are motivated to avoid objects or actions viewed as unclean or taboo. Researchers utilizing MFT have found that endorsement of different moral foundations depends on one’s political orientation. Liberals tend to endorse individualizing moral foundations (care and fairness), whereas conservatives generally endorse a wider range of binding moral foundations (ingroup, authority, and purity), rating care and fairness somewhat lower than liberals (Hurst & Stern, Citation2020; Kivikangas et al., Citation2021).

MFT is an appropriate theoretical lens for the present work because it is well-established and has been frequently used in research related to moralized communication (e.g. Day et al., Citation2014; Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Hurst & Stern, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2023a; Wolsko et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, scholars have developed a widely-used scale for measuring endorsement of the various moral foundations (moral foundations questionnaire, Graham et al., Citation2008) and have provided direction for operationalizing the moral foundations within messages through tools like the moral foundations dictionary (Graham & Haidt, Citation2021).

Moralized conceptions of climate change frequently rely on liberal moral foundations of care and fairness, both in justifying climate change as a moral issue due to its potential to cause harm (Salomon et al., Citation2017) and moral framing of climate change messages (Wolsko et al., Citation2016). In a content analysis of newspaper op-eds and public service announcements, Feinberg and Willer (Citation2013) found that climate change communication often focused on the care foundation, possibly because liberals tend to moralize environmental issues to a greater degree than conservatives (Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013) or because of liberals’ failure to effectively frame environmental issues as conservatives have framed other moral issues (Lakoff, Citation2010). For example, Lakoff (Citation2016), writes about how conservatives have effectively moralized tax cuts. He argues that taxation of the rich has been framed as a punishment for model citizens who have achieved the American Dream in accumulating their wealth. Additionally, conservatives have positioned themselves as making a moral commitment to prevent governmental overreach.

Crafting a message focused on caring for the environment may resonate with liberals, but may not appeal to conservatives as much as a message that, for example, emphasizes the need to reduce pollution and “purify the environment” (Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013, p. 59).

Matching the moral framing of a message with individuals’ moral foundations can increase message effectiveness. Perceived message effectiveness (PME) is a valuable outcome to consider, as it is an important indicator of positive message reception and is positively associated with behavioral intentions and actual behavior change (Noar et al., Citation2020). The present work tests relatively brief messages, thus we also note that PME may be more amenable to influence than other, more downstream persuasion outcomes (e.g. policy support). Some work on climate communication has examined PME as a standalone outcome (Sangalang & Bloomfield, Citation2018). Other research focused on the negative health and environmental impacts of meat consumption has examined PME alongside outcomes such as risk perceptions and behavior intentions and has found that conditions rated highest in PME also elicited greater risk perceptions (Taillie et al., Citation2021) and intentions to reduce meat consumption (Rayala et al., Citation2022).

Communicators have long sought to optimize the effectiveness of campaigns through message tailoring (Kreuter & Wray, Citation2003). Traditionally, this has involved consideration of demographic characteristics, but psychographic attributes such as values and morals could also be considered. Research shows that moral framing based on care and fairness is effective at reinforcing liberal viewpoints, while framing based on authority and purity strengthens conservative viewpoints across a variety of topics (Day et al., Citation2014). Similarly, some studies have shown that messages based on the care and fairness foundations can be more effective for encouraging perceptions of credibility and policy support for liberals (Huang et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2023b). However, that same work failed to find identical persuasive effects of ingroup, authority, and purity framing among conservatives, indicating that morally framed messages may not always impact groups with different political ideologies comparably. Meanwhile, other research has found that messages appealing to binding moral foundations or a variety of foundations (compared to a narrower framing grounded in individualizing foundations) can be more effective in encouraging pro-environmental outcomes among conservatives (Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Wolsko et al., Citation2016), particularly when these messages are also coming from a conservative source (Hurst & Stern, Citation2020). For example, moral framing based on conservative values could take the form of appeals to patriotism to motivate protection of America’s natural environment (Wolsko et al., Citation2016). Therefore, we hypothesize:

H1: (a) Support for pro-environmental policies and (b) perceived message effectiveness (PME) will be greatest when moral framing matches the individual’s endorsement of that moral foundation.

H2: (a) Politically conservative participants will report stronger policy support and PME when exposed to binding moral frames (authority, ingroup, and purity) compared to individualizing moral frames (care and fairness), whereas (b) politically liberal participants will report stronger policy support and PME when exposed to individualizing moral frames compared to binding moral frames.

The dilemma of moral framing & the sacred values protection model

Many of the moral framing studies discussed thus far have focused primarily on intended persuasive outcomes, such as heightened perceived argument strength (Wolsko et al., Citation2016), pro-environmental behavior intentions (Hurst & Stern, Citation2020), and pro-environmental policy support (Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013). However, scholars within the realm of health communication have rightfully highlighted the need to study a variety of unintended impacts of persuasive messaging in order to better understand how messages affect audiences (Cho & Salmon, Citation2007). Persuasive messaging intended to motivate a prosocial behavior could instead have a boomerang effect, which involves a message resulting in the opposite of its intended effect on said behavior (Cho & Salmon, Citation2007). Within moral framing research grounded in MFT, boomerang effects have been conceptualized merely as morally framed messages being less effective than a control message in response to a mismatched moral frame and endorsement (Luttrell & Trentadue, Citation2023).

However, unintended consequences may be more severe than a lack of persuasion, for example by establishing acceptable behavioral norms and inadvertently leading to the stigmatization of individuals or groups who do not conform (Cho & Salmon, Citation2007). When considering possible consequences of moral framing, some scholars have suggested that moralization and moral framing may be a “double edged sword” (Täuber et al., Citation2015, p. 457). On one hand, moralizing an issue can reduce partisan gaps (Wolsko et al., Citation2016) and encourage individuals to engage in pro-environmental behaviors (Salomon et al., Citation2017; Wolsko et al., Citation2016). However, moralization can have drawbacks. Namely, morally framed messages that bolster the support of a few while deepening existing divides may ultimately do more harm than good. According to the sacred value protection model (SVPM), both immoral actions and immoral thoughts can lead to moral outrage, negative affective responses, and a desire to punish transgressors (Tetlock et al., Citation2000). According to Tetlock et al. (Citation2000), people who experience moral outrage will harshly judge transgressors, feel strong negative emotions like anger or disgust, and support punishment for moral transgressors. The idea of morally framed messages contributing to such responses is similar to the idea of persuasive messaging unintentionally bolstering normative beliefs among some, leading to the shaming or isolation of others (Cho & Salmon, Citation2007). Along these lines, researchers have found that moralized issues evoke more anger and stronger feelings of ingroup morality (Täuber & van Zomeren, Citation2012) and increased out-group outrage (Täuber & van Zomeren, Citation2013). We argue that moral framing primes people to think about an issue in moral terms and as a result to consider those who do not share their moral values as moral transgressors or out-group members, potentially deserving of anger, disgust, or punishment.

Following SVPM’s predictions that moral conviction promotes a desire to punish moral transgressors and distance oneself from immoral beliefs, researchers have found that moral beliefs can discourage participants from considering solutions that involve compromise (Ryan, Citation2017), reduce support for leaders willing to compromise (Kodapanakkal et al., Citation2022), lead to decreased willingness to seek out intergroup help (Täuber & van Zomeren, Citation2013), and result in increased preferences to physically and socially distanceFootnote1 oneself from those who do not share the same moral beliefs (Skitka et al., Citation2005; Wright et al., Citation2008). In a particularly striking set of studies, Skitka and colleagues (Citation2005) asked people to identify pressing issues along with the strength of their moral conviction on that stance. Next, they reported how happy they would be to have someone who disagreed with them as a friend, coworker, partner, and more. Results indicated greater moral conviction predicted less desired social proximity to people with different beliefs. Findings were similar in a second study in which researchers selected a range of issues. In a third experiment, differences in moral beliefs resulted in greater desired physical distance between participants in a laboratory setting. Finally, a fourth study indicated that discussion of a moral issue among group members with different stances resulted in less goodwill toward other participants compared to groups whose members shared similar stances.

Lakoff (Citation2010) suggested that the use of ideological framing can “activate that ideological system” (p. 72) and automatically trigger judgments and thought processes associated with that frame, which would then affect how people interpret a message. In the same manner, we anticipate that moral framing will make moral convictions more salient for participants. Based on past research showing that moral frame matching can heighten message effects (e.g. Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Hurst & Stern, Citation2020; Wolsko et al., Citation2016), we anticipate this effect to be more pronounced when the moral values emphasized in the message align with those endorsed by the individual. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3: Unintended outcomes (group-based outrage and decreased desire for social proximity) will be greatest when a message’s moral frame matches the individual’s endorsement of moral foundation.

H4: Conservative participants will report stronger negative outcomes when exposed to binding moral foundation messages (vs. individualizing), but liberal participants will report stronger negative outcomes when exposed to individualizing moral foundation messages (vs. binding).

In the present study, we make moral ingroup and outgroup distinctions based on concern for (versus lack of concern for) the environment, which will be defined in more detail in the method section.

Method

Recruitment and sample

Participants were Amazon Mechanical Turk workers recruited through CloudResearch who had at least 1000 prior tasks approved and an approval rating of 98% or higher.Footnote2 Our preregistered hypotheses, data, syntax, and study materials are available online.Footnote3 Prior to study launch, we conducted our power analysis with G*Power (version 3.1.9.6) using the “ANOVA: Fixed effects, special, main effects and interactions” statistical test. We conducted this test with an effect size f of 0.14 (converted based on the partial eta squared interaction effect of .02 in Day et al., Citation2014), alpha error probability of .05, power of .8, numerator df 5, and the number of groups set to 12. These numbers were computed based on our initial pre-registered analysis plan of conducting ANOVAs and t-tests for our main analyses and would have addressed H1-4. The power analysis indicated that a minimum of 661 participants would be required. As such, we recruited a total of N = 754 participants residing in the United States. We had a final sample size of 715 after excluding participants who failed at least one of three attention check questions (n = 26), completed the survey more than two standard deviations above the survey duration mean (n = 4), took less than two minutes to complete the survey (n = 2), failed a “catch” item built into the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (n = 5)Footnote4, and who showed evidence of straight lining answers (n = 2).

The average age was 44.74 years old (SD = 13.29, range = 20-81). The racial breakdown of participants was as follows: 79.2% (n = 566) Caucasian, 8.7% (n = 62) Black or African American, 8.1% (n = 58) Asian or Pacific Islander, 4.1% (n = 29) Hispanic, 2.1% (n = 15) multiracial or biracial, 1.3% (n = 9) Native American or Alaskan Native, 0.3% (n = 2) Middle Eastern, and 1.5% (n = 11) either chose not to answer or identified as a category not listed. Half of participants (50.21%) identified as female, 48.81% identified as male, four participants identified as nonbinary/third gender, and two identified as a gender not listed. Over half of participants (63%) identified as politically liberal, 37% identified as conservative, and two participants chose not to indicate their political ideology (6-point scale from 1 = extremely liberal to 6 = extremely conservative; M = 3.07, SD = 1.39). Most participants (64.47%) had earned an undergraduate degree or higher, and 56.92% of participants reported an annual household income of $50,000 or greater.

Procedure

This between-subjects online experiment contained six conditions; five corresponding to the moral foundations in MFT: care (n = 118), fairness (n = 112), ingroup (n = 124), authority (n = 120), purity (n = 109), and one control (n = 132) condition. Participants first viewed consent information, then reported their moral conviction for environmental protection and completed the Moral Foundation Questionnaire. Next, they were randomly assigned to one of six conditions in which they read their assigned message. Afterward, participants completed self-report measures that included a manipulation check, variables of interest, and demographic questions. Respondents were paid for their participation and all procedures were approved by the authors’ IRB.

Stimuli and pilot-testing

We created text-based stimuli to represent moral frames that reflected each of the five foundations. The length of each message was kept consistent across the five treatment conditions (94-99 words). Each condition began with a general introductory statement about anthropogenic climate change. This statement was the only content included in the control condition. In the experimental conditions, this introductory statement was followed by a moral argument for climate protection and collective action formulated using terms from the moral foundations dictionary indicative of each moral foundation (Graham & Haidt, Citation2021). See for full stimulus messages, which were pilot tested prior to the main study to provide supportive evidence for the success of our moral frame manipulations (see supplemental materials for pilot testing details).

Table 1. Stimulus messages.

Measures

Moral foundation questionnaire

The shortened version of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ; Graham et al., Citation2008) consisted of two sections of 11 questions. The first section asked participants to indicate how relevant various considerations are when deciding whether something is right or wrong on a scale from 1 (not at all relevant) to 6 (very relevant). The second section asked about opinions on a variety of behaviors on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to strongly agree (6). Scores for each moral foundation were averaged to create a scale. An example care item included “Whether or not someone suffered emotionally” (M = 4.90, SD = .87, α = .74). An example fairness item was “Whether or not some people were treated differently than others” (M = 4.97, SD = .82, α = .74). An example ingroup item included “Whether or not someone’s action showed love for his or her country” (M = 3.34, SD = 1.11, α = .72). An example authority item was “Whether or not someone showed a lack of respect for authority” (M = 3.54, SD = 1.11, α = .78). Finally, an example purity item was “Whether or not someone violated standards of purity and decency” (M = 3.59, SD = 1.38, α = .88).

Dependent variables

Environmental policy support. Policy support was measured and averaged using a 9-item scale (Feldman & Hart, Citation2018; Ivanova & Tranter, Citation2008; Marlon et al., Citation2022; Zhao et al., Citation2011) asking participants on a range of 1 (strongly oppose) to 7 (strongly support) about a range of policies, like “Imposing tougher fuel efficiency standards for automobiles and trucks” and “Increasing taxes on all citizens in support of policies that protect the environment” (M = 5.14, SD = 1.44, α = .92).

Perceived message effectiveness. Perceived message effectiveness (PME) was measured and averaged using a 6-item scale (Kim et al., Citation2017) ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) regarding how much participants felt the message was: worth remembering, powerful, informative, meaningful, convincing, and attention-grabbing (M = 4.80, SD = 1.53, α = .96).

Group-based outrage. We followed a two-step procedure in order to gauge group-based outrage. First, we assessed moral conviction on the issue of “environmental protection” with two items (“How much would you agree that your attitude on each of these issues reflects your core moral beliefs and convictions?” and “How much would you agree that your attitude on each of these issues is deeply connected to fundamental questions of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’?”) on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale (Wisneski & Skitka, Citation2017). They then indicated their feelings about people in the moral outgroup on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) scale to 7 items: annoyed, irritated, outraged, angry, despised, disgusted, contemptuous (Täuber & van Zomeren, Citation2013). Participants who rated their moral conviction about environmental protection as low (below the midpoint) reported their feelings toward people who care very much about protecting the environment (M = 1.42, SD = .75, α = .93). Participants who reported high moral conviction (above the midpoint) rated their feelings toward people who do not care at all about the environment (M = 2.78, SD = 1.69, α = .95). We then combined responses to form an overall group-based outrage scale (M = 2.63, SD = 1.21)

Social proximity. Desired social proximity was measured using a 12-item scale (Skitka et al., Citation2005) ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Participants reported how happy they would be to have someone from an outgroup as, e.g. president or their children’s teacher. Outgroups were defined in the same manner as described under group based outrage. Participants who reported high moral conviction about climate change rated their feelings toward people who do not care at all about the environment and items were averaged to create a scale (M = 2.51, SD = 1.27, α = .97). Meanwhile, participants who rated their moral conviction low reported their feelings toward people who care very much about protecting the environment and items were averaged to create a scale (M = 4.41, SD = 1.43, α = .97). We then combined responses to form an overall social proximity scale (M = 2.77, SD = 1.45). See for the descriptive statistics across conditions for all four outcomes of interest.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for outcomes of interest across conditions.

Results

Manipulation check

We adapted a manipulation check measure from previous work to assess whether participants believed the message they read reflected each moral foundation (Day et al., Citation2014). Participants indicated on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) how closely the message they had just seen matched a description of each foundation. For example, the care foundation was described as focusing “on the importance of caring for others, being kind, and preventing harm,” and the ingroup foundation as focusing “on solidarity and dedication to the good of a bigger group.”

One-way ANOVAs generally support the success of our manipulations such that the care F(5, 709) = 15.03, p < .001, partial η2 = .10; fairness F(5, 709) = 33.14, p < .001, η2 = .19; ingroup F(5, 709) = 22.45, p < .001, η2 = .14; authority F(5, 709) = 17.97, p < .001, η2 = .11; and purity F(5, 709) = 13.85, p < .001, η2 = .09 messages were perceived to match the description of each foundation. Pairwise comparisons show that the fairness (M = 4.21, SD = .94), authority (M = 3.09, SD = 1.40), and purity (M = 3.78, SD = 1.08) messages were rated significantly higher in adhering to their respective moral foundations compared to all other messages. The care (M = 3.96, SD = 1.07), and ingroup (M = 3.90, SD = 1.18) messages were generally rated significantly higher than the other messages on their respective items.

Hypotheses testing

H1 predicted that moral foundation endorsement would moderate the effects of the message frames, such that environmental policy support and PME would be greatest when the message an individual read matched their endorsement of that foundation. To interpret both main effects and interaction effects, we ran hierarchical linear regressions (entering clusters of predictors in sequential blocks) on the dependent variables of policy support and PME. In Block 1, we entered the message conditions, dummy-coding the conditions with the control condition as the reference group. In Block 2, we entered participants’ endorsement of the five moral foundations; and in Block 3, we included the five interaction terms for the matches between the condition variables and participants’ endorsement of the moral foundations (e.g. care frame X care endorsement). Thus, the full models included all condition dummies, foundation endorsements, and matched interaction terms. See for full results.

Table 3. Results for hierarchical linear regression of moral foundation endorsement as a moderator.

For policy support, condition alone (in Block 1) did not contribute significantly to the regression model F(5, 709) = .80, p = .55, R2 = .006 (R2 change = .006, p = .55). However, individual endorsement of various moral foundations, included in block 2, contributed significantly to the regression model F(10, 704) = 29.69, p < .001, R2 = .30 (R2 change = .29, p < .001), with main effects resulting from endorsement of all five moral foundations. Finally, with the addition of interactions between condition and moral foundation endorsement in block 3, the model remained significant F(15, 699) = 20.067, p < .001, R2 = .30. However, the addition of the interaction terms did not significantly improve the model fit. Because none of the interaction terms in Block 3 were significant, these results failed to support H1a.

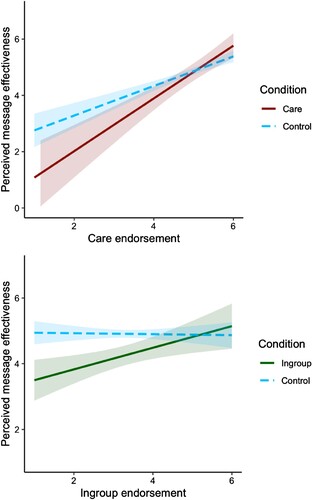

For PME, the condition variables in block 1 contributed significantly to the regression model F(5, 709) = 3.56, p = .003, R2 = .02, with the ingroup and authority conditions increasing PME (vs. control). Furthermore, the addition of moral foundation endorsements in block 2 also contributed significantly to the regression model F(10, 704) = 14.69, p < .001, R2 = .17 (R2 change = .15, p < .001), with main effects for the endorsement of the harm and fairness foundations. Finally, with the inclusion of the interactions between condition and moral foundation endorsement in block 3, the regression model remained significant F(15, 699) = 11.20, p < .001, R2 = .19 (R2 change = .02, p = .003). There was a significant care condition X endorsement of care foundation interaction (unstandardized B = .41, p = .01). There was also a significant ingroup condition X endorsement of ingroup interaction (unstandardized B = .34, p = .005). To probe these interactions, we used the Johnson-Neyman technique using the PROCESS macro model 1 (Hayes, Citation2017) in SPSS. Compared to the control condition, participants who did not strongly endorse the care moral foundation and were exposed to the care message reported significantly lower (p < .05) levels of PME relative to control. Participants who strongly endorsed the care moral foundation and were exposed to the care message reported higher levels of PME compared to the control condition, but this was not statistically significant (p > .05). Additionally, compared to the control condition, participants who did not strongly endorse the ingroup moral foundation and were exposed to the ingroup message reported significantly lower (p < .05) levels of PME. Participants who strongly endorsed the ingroup moral foundation and were exposed to the ingroup message reported higher levels of PME compared to the control condition, but again this was not statistically significant (p > .05). See for interaction plots.

H2 predicted political ideology would moderate the effect of moral foundation messages on policy support and PME. To test this hypothesis, we ran a linear regression which included the dummy-coded conditions, ideology, as well as the interaction terms between political ideology (treated as a continuous variable) and the treatment conditions (vs. control). presents the full results from this analysis. For policy support, none of the interaction terms were significant, failing to support H2a. This suggests the effect of moral foundation messages on policy support did not depend on one’s political ideology.

Table 4. Results for hierarchical linear regression of political ideology as a moderator.

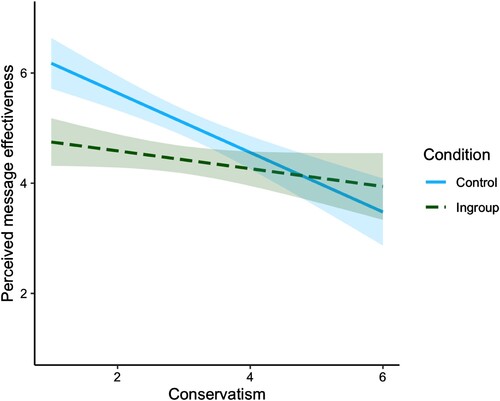

Testing whether political ideology would moderate the effect of morally framed messages on PME, we found a significant ingroup X ideology interaction (B = .38, p = .005). We used the Johnson-Neyman technique to probe this interaction by employing the PROCESS macro (Hayes, Citation2017) in SPSS with model 1. Compared to control, when extremely liberal, liberal, and slightly liberal participants saw an ingroup message, they reported significantly lower (p < .001) levels of PME. There was no impact of ingroup messaging among conservative participants. See for details.

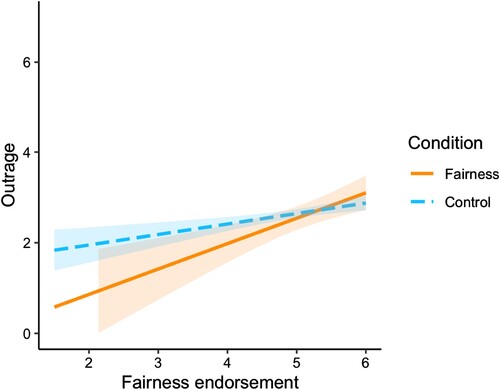

H3 predicted group-based outrage would be greater and desired social proximity would be lower when a message’s moral frame matches an individual’s endorsement of moral foundations. To test this hypothesis, we again ran a hierarchical linear regression, following the same procedure as H1. For group-based outrage, the condition variables in block 1 did not contribute significantly to the regression model F(5, 687) = .25, p = .94, R2 = .002 (R2 change = .002, p = .94). The moral foundation endorsement variables added in block 2 contributed significantly to the regression model F(10, 682) = 12.48, p < .001, R2 = .155 (R2 change = .15, p < .001), with significant main effects of endorsement of the harm, fairness, and authority foundations. With the inclusion of the interactions between condition and moral foundation endorsement in block 3, the regression model remained significant F(15, 677) = 8.66, p < .001, R2 = .16, but did not significantly improve the model. However, there was a significant fairness condition X endorsement of fairness interaction (unstandardized B = .33, p = .04). Compared to the control condition, participants who did not strongly endorse the fairness moral foundation and were exposed to the fairness message reported significantly lower (p < .05) levels of group-based outrage. Participants who strongly endorsed the fairness moral foundation and were exposed to the fairness message reported higher levels of group-based outrage compared to the control condition, but this was not statistically significant (p > .05). Therefore, H3a was not supported. See for interaction plots.

For desired social proximity, the condition variables in block 1 did not contribute significantly to the regression model (R2 = .005, p = .60). The addition of moral foundation endorsement variables in block 2 contributed significantly to the regression model F(10, 704) = 11.86, p < .001, R2 = .14 (R2 change = .14, p < .001), with main effects of endorsement of the harm, fairness, and authority foundations. With the inclusion of the interaction terms in block 3 the regression model remained significant F(15, 699) = 8.23, p < .001, R2 = .15, but the R2 change was not statistically significant (R2 change = .006, p = .45). Because none of the interaction terms in Block 3 were significant, these results failed to support H3b.

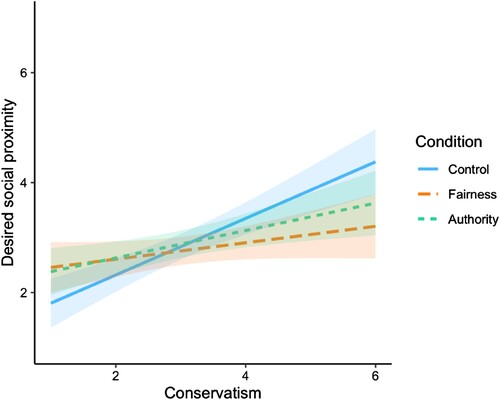

H4 predicted that ideology would moderate the relationship between moral foundation messages and group-based outrage as well as social proximity, such that conservatives would experience stronger negative outcomes in response to binding moral foundations and liberals would report greater negative outcomes in response to individualizing moral foundations. To test this hypothesis, we again ran a linear regression including interaction terms between political ideology and the treatment conditions. See for full results. For group-based outrage, there was a main effect of ideology, but none of the interaction terms were significant. For social proximity, there was once again a significant main effect of ideology and several interaction terms emerged as significant. There was a significant fairness appeal X ideology interaction (B = -.37, p = .006), and a significant authority appeal X ideology interaction (B = -.27, p = .04). Extremely liberal participants (ideology rating 1 on a 6-point scale) report greater desired social proximity when exposed to a fairness message compared to control (p < .05). This effect disappeared for liberal and slightly liberal participants, then reversed for slightly conservative, conservative, and extremely conservative participants, who reported decreased desired social proximity when exposed to a fairness message compared to control (p < .05). See for details. These effects did not occur in the direction we had predicted, thus H4 was not supported.

Discussion

We examined both intentional and unintentional impacts of morally framed climate change messages. Our study design is unique in that we used five messages designed to each correspond to a distinct moral foundation rather than combining multiple moral foundations into a single message (e.g. Wolsko et al., Citation2016) or collapsing responses to multiple moral frames for analysis (e.g. Huang et al., Citation2022). Despite the important contributions of prior research, it is valuable to examine effects of these moral foundations separately first because they are conceptualized as distinct concepts in MFT and second to identify any unique effects of each foundation. Specifically, many previous studies have combined various moral foundations into one message, and as a result, those studies are unable to shed light on whether particular foundations drive observed effects. Examining each foundation individually in its own message provides the opportunity to better understand how specific moral frames impact audiences, which could have practical implications for communications practitioners as they consider how to formulate persuasive moral appeals for different audiences. Additionally, we measured moral foundation endorsement as well as political ideology, rather than relying solely on ideology as a proxy for moral beliefs as some past studies have (e.g. Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013).

Our findings suggest that matching moral framing to individuals’ moral foundation endorsement at times may fail to provide substantial positive persuasive benefits. This conceptually replicates some more recent research on moral framing of environmental messages, which found that exposure to messages grounded in the binding moral foundations failed to motivate personal pro-environmental behavior intentions or desire to receive environmental conservation information among conservative participants (Kim et al., Citation2023a). In some instances, we found that moral frame mismatches led to decreased PME, but matching failed to increase PME compared to the control condition. Furthermore, we found that exposure to a fairness frame had opposing impacts on liberals and conservatives, leading to greater desired social proximity among liberals and decreased desired social proximity among conservatives to people with conflicting views on environmental protection. Altogether, results from this study indicate that moral framing rooted in individual moral foundations may not always provide significant rewards.

Impacts of moral framing on intended outcomes

Despite previous findings that matching the moral framing of an environmental message to the audience’s moral values can have persuasive effects (Day et al., Citation2014; Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Wolsko et al., Citation2016), we did not find that matching the moral frame of a message to a person’s endorsement of a moral foundation led to an increase in policy support. One explanation for this is that prior studies have tested messages framed to represent multiple foundations in a single message (e.g. Wolsko et al., Citation2016). In contrast, our study tested five messages each framed to express a single foundation and we measured moral foundation endorsement using the Moral Foundations Questionnaire rather than relying solely on ideology to understand participants’ moral beliefs, and we found little evidence for the matching hypothesis of moral appeal with moral endorsement.

Furthermore, none of the moral frames proved particularly effective for liberals or conservatives in terms of boosting their policy support. We see a few plausible explanations for the divergence between our findings and prior work that has indicated persuasive effects of matched moral appeals (Day et al., Citation2014; Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Wolsko et al., Citation2016). First, like past studies, our messages were brief, so a single message may not be enough to sway participants’ attitudes. Second, earlier studies were conducted when climate change was less contentious and polarized (e.g. Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013), but because climate change and climate policies are currently highly charged topics in America, it is possible that our participants had already firmly decided how they feel about climate change and pro-environmental policies. Third, a ceiling effect on policy support may have occurred, as participants ranging from extremely liberal to somewhat conservative reported policy support above the scale’s midpoint. We attempted to combat potential ceiling effects by adding more contentious policy options to our measure, such as requiring climate change to be taught in schools and increasing taxes for all citizens to fund environmentally friendly policies. However, this appears not to have dampened high levels of policy support among many participants.

Meanwhile, when examining PME as an outcome, results did not indicate any benefits of moral frame matching and only revealed negative effects of mismatched moral framing in response to the care and ingroup messages. Specifically, PME was lower for those who did not strongly endorse these foundations, while those who did strongly endorse these foundations reported levels of PME comparable to the control condition. Political ideology only moderated the effect of one moral frame on PME, such that liberals perceived an ingroup-framed message to be less persuasive than a control message. The fact that the ingroup message was not perceived as more persuasive by conservative participants suggests the limited efficacy of morally tailored messages for boosting perceptions of message effectiveness for political partisans. Overall, our findings do not point definitively to the utility of moral matching messages. Results may also have been impacted by a ceiling effect, considering that all participants except those who were extremely conservative indicated an average PME above the scale midpoint across message frames.

Effects of moral frames on unintended outcomes

The SVPM suggests that strongly held moral beliefs can motivate intense negative reactions towards outgroup members, including emotions like anger and disgust as well as a desire to ostracize or punish (Tetlock et al., Citation2000). Rooted in the SVPM and related research, we predicted that moral frame matching could have unintended consequences. Specifically, we hypothesized that moral framing would make people’s moral beliefs more salient and thus motivate hostility toward outgroup members. Contrary to our predictions, moral frame matching largely did not seem to increase unintended outcomes. The only significant interaction we observed was between fairness framing and endorsement of the fairness foundation. In this instance, individuals who did not strongly endorse the fairness foundation felt less outgroup outrage compared to the control condition, while those who did strongly endorse this foundation merely experienced levels of outrage comparable to the control condition.

We also saw that desired social proximity with outgroup members was impacted by the fairness frame, with effects manifesting quite differently for liberal and conservative participants. The fairness message increased liberals’ willingness to be socially close to outgroup members, following research showing that liberals tend to endorse the fairness foundation more strongly (Graham et al., Citation2013; Hurst & Stern, Citation2020) and that exposure to messaging at least partially reliant on a fairness frame can have positive impacts (Wolsko et al., Citation2016). The fairness foundation stressed the idea that everyone deserves access to a clean environment, so it follows logically that this could influence individuals who endorse this foundation to feel more favorably even toward outgroup members. However, this does not mean that fairness messaging can bridge a divide between liberals and conservatives because the fairness frame decreased conservatives’ willingness to be socially close to outgroup members. Conservative participants may have viewed this message as a liberal argument because it invoked language of equality and mentioned low-income populations, which could be perceived as language common to liberal talking points. Thus, a fairness message grounded in more liberal terminology, for example with a focus on justice or equity, could prompt a desire for conservatives to distance themselves from people who might endorse the message (Hurst & Stern, Citation2020). Past work has suggested that moral framing and political ideology mismatches may result in decreased message effectiveness in fostering desired behaviors (Luttrell & Trentadue, Citation2023), but our findings expand on this by pointing to the possibility of mismatched framing motivating a wider range of negative consequences. It is, however, important to put the message effects that we observed in context. The effects of message framing, when observed, were inconsistent and rather small in magnitude, whereas results from our regression analyses show that political leaning played a more prominent role in predicting all four outcomes of interest.

Theoretical and practical implications

Our results do not indicate risks of unintended negative consequences when a message’s moral frame aligns with audience members’ endorsements of moral foundations. However, our findings do point to potential undesirable outcomes among audience members whose political group does not endorse that particular moral foundation. Although a fairness message would not be expected to be especially persuasive for conservative individuals, who typically respond better to messages grounded in the binding moral foundations, our work indicates that a mismatch between a moral frame and audience members’ political ideology could lead to a divisive reaction to the message in the form of reduced willingness to be close to outgroup members. Future studies could expand on our findings by examining topics beyond climate change or environmental policy, and a wider range of negative social outcomes (e.g. stigmatization) in response to morally mismatched counterattitudinal moral messages.

Furthermore, scholarly conversation on the ethical implications of using moral frames would be welcome. Ethical climate change communication should be “focused on building trust and demonstrating character and goodwill” (Lamb & Lane, Citation2019, p. 248) while reducing polarization. If morally framed messages sometimes yield positive outcomes but other times result in few benefits alongside negative outgroup perceptions among some audience segments, how should communication scholars and practitioners weigh the ethical implications of employing these kinds of messages, particularly in relation to already divisive topics?

From a practitioner perspective, our evidence suggests a message that appeals only to one moral foundation may be a somewhat low-reward scenario when it comes to climate change communication. Scholars have already pointed out that much of moralized climate messaging has missed the opportunity to appeal broadly to audiences across the political spectrum due to a reliance primarily on liberal values of care (Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013). Considering this in conjunction with our present findings, practitioners might contemplate potential benefits of avoiding moral framing altogether (Täuber et al., Citation2015) or at the very least diversifying messages to include strategies beyond moral framing. This suggestion could extend to communication around other highly divisive topics as well and is particularly important to keep in mind if the goal of a message or campaign is to encourage groups with different moral values to work together. In those cases, it could be helpful to consider de-moralizing (Skitka et al., Citation2021) or counter-moralizing (Mulder et al., Citation2015) environmental issues. De-moralizing messages could focus on pragmatic rather than moral considerations, correcting exaggerated beliefs about harm, avoiding highly emotional language, or explicitly challenging the moralization of an issue by arguing that it is not reasonable to moralize a topic (Kodapanakkal et al., Citation2022; Kraaijeveld & Jamrozik, Citation2022; Mulder et al., Citation2015; Skitka et al., Citation2021). Recent work has shown that simply framing an argument in non-moral terms can be sufficient to de-moralize attitudes (Kodapanakkal et al., Citation2022) and past research has suggested that reducing moralization could help people who feel stigmatized to make healthier choices (Mulder et al., Citation2015). However, there is still a need for more research into reducing moralization of a topic (Skitka et al., Citation2021) such as investigating if the source of the message (e.g. a trusted source that shares the audience’s views and ideological position, similar to Hurst & Stern, Citation2020) would increase persuasive effects since our experimental stimuli did not provide any source cues. Past research has shown that messages from ingroup sources are perceived to be more credible and trustworthy (Hornsey et al., Citation2002; Kahan et al., Citation2011). Additionally, Fielding et al. (Citation2020), in a series of two experiments, found that participants who were exposed to a message where climate change policy was endorsed by members of their political ingroup (as opposed to the outgroup), resulted in more positive attitudes and greater support for climate policies (see also Bolsen et al., Citation2019). As such, future research should consider the source of climate messages in efforts to reduce moralization.

Limitations and future research

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, in our measure of political ideology, we opted to focus on the liberal-conservative ideological spectrum based on past MFT research. However, for outcomes like climate policy support, we may not see as much movement on both sides of this political spectrum (i.e. a ceiling effect for liberals and a floor effect for conservatives). Future research should consider studying individuals who subscribe to a different political ideology, such as libertarians. Second, following past research, we considered only a single message exposure. Researchers can consider conducting longitudinal studies to examine effects over time or responses to repeated message exposures. Third, to test effects of moral foundation matching, 25 interaction terms were computed. While our approach is novel, in that many past studies have not tested the matching hypothesis using people’s actual endorsement of the moral foundations, the interactive effect we observed could be a chance finding (though we note that this interaction was for the hypothesized match between moral frame and moral foundation). Fourth, because of a change in analysis plan as noted in footnote 2, our study is likely underpowered to detect interactions for the individualizing foundations, though follow-up equivalence tests suggest power is not a likely explanation for the lack of interaction effects for the binding foundations (see supplemental materials). Future studies should conduct a well-powered confirmatory study by replicating our study design. Next, we defined outgroups based on levels of moral conviction. However, it is possible that individuals with strong moral convictions around the issue of environmental protection may view people with similar (e.g. pro-environmental) beliefs and low moral conviction about the topic of environmental protection as belonging to the same social (if not necessarily moral) ingroup. Future research could examine issue stance rather than moral conviction as a defining characterization of ingroup/outgroup categories. Finally, the present work tested moral frames based on MFT, which has been critiqued by some scholars for its omission of important cooperation-related domains such as family and property (e.g. Curry et al., Citation2019). Future work could consider testing moral frames based on a wider variety of theories beyond MFT, such as Morality-as-Cooperation theory (Curry et al., Citation2019).

Conclusion

Effective climate action requires united efforts between people with different values and political ideologies. Some scholars have suggested that moral framing may bridge divides around climate change (Wolsko et al., Citation2016), while others have cautioned that it might deepen them (Täuber et al., Citation2015). This study examined both positive intended effects and negative unintended consequences of morally framed messages. Our research was unique in its use of five distinct morally framed messages, designed based on Moral Foundations Theory. Results suggest there may be little payoff from climate change messages rooted in a single moral foundation, as they failed to significantly increase policy support or PME among liberals and conservatives. Furthermore, there is some evidence in our data that morally mismatched arguments can drive people apart, given that an argument framed in terms of fairness decreased conservatives’ desire to be socially proximal to outgroup members (i.e. individuals holding opposing views about the environment). Overall, practitioners may consider the benefits of persuasive messaging strategies beyond moral framing if seeking to unite people around a common environmental cause.

Supplemental materials

Download MS Word (713.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data for this study are available online through OSF at https://osf.io/t8xb2/?view_only=a00e36a00f3546f3b24de5d32c282f3b.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Scholars have examined social distance as how closely someone associates or would like to associate with another person (i.e., as friends, coworkers, partner). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the term social distance has gained a different meaning. Thus, throughout the remainder of this paper, we refer to this idea as desired social proximity to avoid confusion.

2 Restricting recruitment of MTurk samples based on number of approved tasks and approval rating is a common strategy for ensuring participation of attentive workers and, by extension, improving data quality (Amazon Mechanical Turk, Citation2019)

3 We note a few divergences between our study and our preregistration plan. First, while we initially hypothesized about moral conviction as an outcome and moderating variable, we opted not to present those results for the sake of simplicity. Second, we now include perceived message effectiveness as an additional favorable intended outcome since our experimental manipulation is based on persuasive messaging. Third, we do not present the findings for the reactance variables because they are not pertinent to the arguments made in this paper. Fourth, instead of conducting t-tests and ANOVAs, we chose to conduct regressions to test our hypotheses since both tests are functionally identical and regressions lend more easily to interactions with continuous moderators.

4 While the MFQ includes two “catch” items, we opted to keep participants who answered favorably to the item “whether or not someone was good at math” because prior research has found that this item disproportionately excludes participants who are young, male, and politically conservative (Skurka et al., Citation2020).

References

- Amazon Mechanical Turk. (2019, April 18). Qualifications and worker task quality. Medium. https://blog.mturk.com/qualifications-and-worker-task-quality-best-practices-886f1f4e03fc.

- Bell, D. (2013). Climate change and human rights. WIREs Climate Change, 4(3), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.218

- Bolsen, T., Palm, R., & Kingsland, J. T. (2019). The impact of message source on the effectiveness of communications about climate change. Science Communication, 41(4), 464–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547019863154

- Cacciatore, M. A., Scheufele, D. A., & Iyengar, S. (2016). The end of framing as we know it … and the future of media effects. Mass Communication and Society, 19(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1068811

- Cho, H., & Salmon, C. T. (2007). Unintended effects of health communication campaigns. Journal of Communication, 57(2), 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00344.x

- IPCC,. (2023). Summary for policymakers. In Core Writing Team, H. Lee, & J. Romero (Eds.), Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 1–34). IPCC.

- Curry, O. S., Jones Chesters, M., & Van Lissa, C. J. (2019). Mapping morality with a compass: Testing the theory of ‘morality-as-cooperation’ with a new questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 106–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.10.008

- Day, M. V., Fiske, S. T., Downing, E. L., & Trail, T. E. (2014). Shifting liberal and conservative attitudes using moral foundations theory. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(12), 1559–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214551152

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Feinberg, M., & Willer, R. (2013). The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science, 24(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612449177

- Feldman, L., & Hart, P. S. (2018). Climate change as a polarizing cue: Framing effects on public support for low-carbon energy policies. Global Environmental Change, 51, 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.05.004

- Fielding, K. S., Hornsey, M. J., Thai, H. A., & Toh, L. L. (2020). Using ingroup messengers and ingroup values to promote climate change policy. Climatic Change, 158(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02561-z

- Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition. Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

- Graham, J., & Haidt, J. (2021). Moral foundations dictionary. MoralFoundations.org. Retrieved from https://moralfoundations.org/wp-content/uploads/files/downloads/moral%20foundations%20dictionary.dic.

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 55–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00002-4

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2008). Moral foundations questionnaire. Moral foundations. https://moralfoundations.org/wp-content/uploads/files/MFQ20.doc.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford publications.

- Hornsey, M. J., Oppes, T., & Svensson, A. (2002). “It’s ok if we say but you can’t”: Responses to intergroup and intragroup criticism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32(2), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.90

- Huang, J., Yang, J. Z., & Chu, H. (2022). Framing climate change impacts as moral violations: The pathway of perceived message credibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095210

- Hurst, K., & Stern, M. J. (2020). Messaging for environmental action: The role of moral framing and message source. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 68, 101394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101394

- IPCC. (2021). Summary for policymakers. In V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, & B. Zhou (Eds.), Climate change 2021: The physical science Basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf.

- Ivanova, G., & Tranter, B. (2008). Paying for environmental protection in a cross-national perspective. Australian Journal of Political Science, 43(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361140802035705

- Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H., & Braman, D. (2011). Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. Journal of Risk Research, 14(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

- Kim, I., Hammond, M. D., & Milfont, T. L. (2023a). Do environmental messages emphasising binding morals promote conservatives’ pro-environmentalism? A pre-registered replication. Social Psychological Bulletin, 18, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.32872/spb.8557

- Kim, J., Lee, S., Wang, Y., & Leach, J. D. (2023b). The power of moral words in politicized climate change communication. Environmental Communication, 17(6), 566–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2227771

- Kim, A., Nonnemaker, J., Guillory, J., Shafer, P., Parvanta, S., Holloway, J., & Farrelly, M. (2017). Antismoking ads at the point of sale: The influence of ad type and context on ad reactions. Journal of Health Communication, 22(6), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1311970

- Kivikangas, J. M., Fernández-Castilla, B., Järvelä, S., Ravaja, N., & Lönnqvist, J. E. (2021). Moral foundations and political orientation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(1), 55–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000308

- Kodapanakkal, R. I., Brandt, M. J., Kogler, C., & van Beest, I. (2022). Moral frames are persuasive and moralize attitudes; Nonmoral frames are persuasive and de-moralize attitudes. Psychological Science, 33(3), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211040803

- Kraaijeveld, S. R., & Jamrozik, E. (2022). Moralization and mismoralization in public health. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 25(4), 655–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-022-10103-1

- Kreps, T. A., & Monin, B. (2011). “Doing well by doing good”? Ambivalent moral framing in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2011.09.008

- Kreuter, M. W., & Wray, R. J. (2003). Tailored and targeted health communication: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. American Journal of Health Behavior, 27(1), S227–S232. doi:10.5993/AJHB.27.1.s3.6

- Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environmental Communication, 4(1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030903529749

- Lakoff, G. (2016). Moral politics: How liberals and conservatives think (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Lamb, M., & Lane, M. (2019). Aristotle on the ethics of communicating climate change. In C. Heyward, & D. Roser (Eds.), Climate justice in a non-ideal world (pp. 229–254). essay, Oxford University Press.

- Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., Carman, J., Wang, X., Goldberg, M., Lacroix, K., & Marlon, J. (2021b). Politics & global warming, March 2021. Yale University and George Mason University. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/politics-global-warming-march-2021b.pdf.

- Leiserowitz, A., Roser-Renouf, C., Marlon, J., & Maibach, E. (2021a). Global warming’s six Americas: A review and recommendations for climate change communication. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 42, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.04.007

- Luttrell, A., Philipp-Muller, A., & Petty, R. E. (2019). Challenging moral attitudes with moral messages. Psychological Science, 30(8), 1136–1150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619854706

- Luttrell, A., & Trentadue, J. T. (2023). Advocating for mask-wearing across the aisle: Applying moral reframing in health communication. Health Communication, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2163535

- Malier, H. (2019). Greening the poor: The trap of moralization. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(5), 1661–1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12672

- Marlon, J., Neyens, L., Jefferson, M., Howe, P., Mildenberger, M., & Leiserowitz, A. (2022, February 23). Yale climate opinion maps 2021. Yale program on climate change communication. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/.

- Mulder, L. B., Rupp, D. E., & Dijkstra, A. (2015). Making snacking less sinful: (Counter-)moralising obesity in the public discourse differentially affects food choices of individuals with high and low perceived body mass. Psychology & Health, 30(2), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.969730

- Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment : Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

- Noar, S. M., Barker, J., Bell, T., & Yzer, M. (2020). Does perceived message effectiveness predict the actual effectiveness of tobacco education messages? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Communication, 35(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1547675

- Patz, J. A., Grabow, M. L., & Limaye, V. S. (2014). When it rains, it pours: Future climate extremes and health. Annals of Global Health, 80(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2014.09.007

- Rayala, H.-T., Rebolledo, N., Hall, M. G., & Taillie, L. S. (2022). Perceived message effectiveness of the meatless Monday campaign: An experiment with US adults. American Journal of Public Health, 112(5), 724–727. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2022.306766

- Rozin, P., Markwith, M., & Stoess, C. (1997). Moralization and becoming a vegetarian: The transformation of preferences into values and the recruitment of disgust. Psychological Science, 8(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00685.x

- Ryan, T. J. (2017). No compromise: Political consequences of moralized attitudes. American Journal of Political Science, 61(2), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12248

- Salomon, E., Preston, J. L., & Tannenbaum, M. B. (2017). Climate change helplessness and the (de)moralization of individual energy behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 23(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000105

- Sangalang, A., & Bloomfield, E. F. (2018). Mother goose and mother nature: Designing stories to communicate information about climate change. Communication Studies, 69(5), 583–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2018.1489872

- Schuldt, J. P., Pearson, A. R., Romero-Canyas, R., & Larson-Konar, D. (2017). Brief exposure to Pope Francis heightens moral beliefs about climate change. Climatic Change, 141(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1893-9

- Skitka, L. J., Bauman, C. W., & Sargis, E. G. (2005). Moral conviction: Another contributor to attitude strength or something more? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 895–917. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.895

- Skitka, L. J., Hanson, B. E., Morgan, G. S., & Wisneski, D. C. (2021). The psychology of moral conviction. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-063020-030612

- Skurka, C., Winett, L. B., Jarman-Miller, H., & Niederdeppe, J. (2020). All things being equal: Distinguishing proportionality and equity in moral reasoning. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(3), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619862261

- Taillie, L. S., Chauvenet, C., Grummon, A. H., Hall, M. G., Waterlander, W., Prestemon, C. E., & Jaacks, L. M. (2021). Testing front-of-package warnings to discourage red meat consumption: A randomized experiment with US meat consumers. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01178-9

- Täuber, S. (2018). Moralized health-related persuasion undermines social cohesion. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 909–909. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00909

- Täuber, S., & van Zomeren, M. (2012). Refusing intergroup help from the morally superior: How one group's moral superiority leads to another group's reluctance to seek their help. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 420–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.08.014

- Täuber, S., & van Zomeren, M. (2013). Outrage towards whom? Threats to moral group status impede striving to improve via out-group-directed outrage. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(2), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1930

- Täuber, S., van Zomeren, M., & Kutlaca, M. (2015). Should the moral core of climate issues be emphasized or downplayed in public discourse? Three ways to successfully manage the double-edged sword of moral communication. Climatic Change, 130(3), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1200-6

- Tetlock, P. E., Kristel, O. V., Elson, S. B., Green, M. C., & Lerner, J. S. (2000). The psychology of the unthinkable: Taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 853–870. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.853

- Voelkel, J. G., & Feinberg, M. (2018). Morally reframed arguments can affect support for political candidates. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(8), 917–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617729408

- Walsh, E. M., & Tsurusaki, B. K. (2018). “Thank you for being Republican”: Negotiating science and political identities in climate change learning. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 27(1), 8–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1362563

- Wisneski, D. C., & Skitka, L. J. (2017). Moralization through moral shock: Exploring emotional antecedents to moral conviction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216676479

- Wolsko, C., Ariceaga, H., & Seiden, J. (2016). Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.02.005

- Wright, C. J., Cullum, J., & Schwab, N. (2008). The cognitive and affective dimensions of moral conviction: Implications for attitudinal and behavioral measures of interpersonal tolerance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(11), 1461–1476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208322557

- Zhao, X., Leiserowitz, A. A., Maibach, E. W., & Roser-Renouf, C. (2011). Attention to science/environment news positively predicts and attention to political news negatively predicts global warming risk perceptions and policy support. Journal of Communication, 61(4), 713–731. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01563.x