ABSTRACT

Identity, a socially constructed concept, makes sense of who we are, and how we relate to others and define our places in the world, including the physical environment. Identity formation and maintenance are complex, transactional relationships negotiated through interpersonal interactions and constantly adapting to the people we meet. Identity is culturally specific and changes through exchanges between and across cultures. Identity formation is fluid, dynamic, and reproduced through interaction with others. Identity is negotiated through power relations to create feelings of “belonging” and acceptance in specific situations and locales. Being accepted as belonging establishes an individual’s and community’s entitlement to human rights in society through social inclusion and exclusion processes. Working with those who do not “belong”, social workers aware of the impact of the social construction of identity should treat people with respect and dignity and provide necessary services.

身份认同是一个社会建构的概念。它可以让我们理解自己是谁, 我们与他人的关系, 并定义我们在世界上的位置, 包括物理环境。身份认同的形成与维持是复杂、交互的关系, 它通过人际互动协商, 并不断适应我们遇到的人。身份认同在文化上是特定的, 并且通过文化之间与跨文化的交流而变化。身份认同形成是流动的、 动态的, 并通过与他人互动而复制。身份认同是通过权力关系来协商的, 在特定情况和地点创造“归属感”和接受感。作为归属感的“被接受”确立了个人和社区在社会中的人权, 它是通过社会融合或排斥的过程而形成的。当社会工作者帮助欠缺“归属感”的受助者时, 应该意识到社会建构的影响, 尊重和尊严地对待他们, 并提供必要的服务。

Introduction

Identity is a contested concept laden with diverse meanings and understandings mediated through complex power relations, human interactions and opportunities to access resources by being accepted as “belonging” to a particular geographic locale associated with people of a specific culture, language and social standing. These complexities complicate how people relate to each other in particular locales in dynamic, fluid, constantly changing relationships as people negotiate their interactions with each other.

I explore the concept of identity, its relationship to people’s sense of belonging, social cohesion and predictability of social relations in this chapter. I argue for the centrality of identity to individual and collective understandings of whom they are individually and as a community. I acknowledge that there is no one formulation of identity wherein “one size fits all” but rather a negotiated sense of identity that varies with the audience or people being addressed and the power relations that define the relationships among and between participants. I examine its relevance and use in social work theory and practice and argue that it is central to realising not only one’s sense of whom one is, but also the human rights pertaining to those who are accepted as “belonging” to a particular society and those who are not. I also demonstrate how participatory action research can assist social workers in understanding the significance of identity in the everyday routines of practice, especially for those who do not “belong” to the dominant or hegemonic group.

Defining identity/ies

Identity is a core concept for defining who people are, where they are from, their cultural and historical background, their daily life routines, and their relationships with others. Erikson (Citation1994) considers identity as the concept used to describe who an individual is. He argues that the notion of identity is both individual, collective and socially constructed. Moreover, Erikson (Citation1994) argues that identity provides the glue that links a sense of belonging to interactions between persons and/or groups. I define identity as a socially constructed entity that is dynamic, fluid, created in and through interaction with others on multiple levels and it changes according to setting (Dominelli Citation2002c). Consequently, I may identify as a teacher, a community worker, a citizen, a neighbour, or a friend, depending on the context I am within, with whom I am interacting, and what I am seeking to achieve. However, since the relationship is an interactive one, I will respond to the other person(s) I am interacting with. If that person “others” me, treats me as different from them, of lesser importance, or seeks to oppress me, I may present another aspect of my identity, for example, rejecting their attempts to pigeon-hole me as “other” or bringing the interaction to an end. In other words, identity is formed in and through interactions with others through complex negotiations around power relations and, therefore, cannot be fixed, unitary, essentialised or pre-determined.

Additionally, in Dominelli (Citation2014), I argue that since identity, citizenship and human rights are closely intertwined and embedded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) as individually held attributes, human rights should not disappear the moment a person crosses a border (United Nation Citation1948). They should be recognised as embedded in the individual and so inalienable and portable, and their collective substance should be guaranteed by the polity represented by the nation-state of which they are a citizen. This nation-state should enter agreements with other nation-states to ensure that a person’s human rights are never lost or ignored. This formulation of human rights is evident in the European Union (EU), which allows freedom of movement and the recognition of human rights, including the right to health, education and other welfare services guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including housing and employment, wherever a person goes within the EU. Moreover, this approach is relevant to social workers who are asked to respond to human needs within a human rights context (Biesteck Citation1957; Ife Citation2001; Reichert Citation2007), for example, refugees and asylum seekers entering the borders of their country who require housing, employment, health care and education services but are hindered from providing these by immigration laws and regulations (Briskman and Cemlyn Citation2005; Home Office Citation2010).

Identities are core to social work theories and practice

Social workers have treated identity as essentialist and fixed. They have done so by subscribing to unitary notions of identity when they were supporting nation-building endeavours aimed at bringing people together to create a sense of belonging to a particular geographical space and retaining control over it (Lorenz Citation1994). Unitary approaches to identity rely on dividing the world into a binary relationship of the “them” over there and excluded, and “us” over here and included. This forms the crux of “othering” people who are different and seeing them as having deficits or deficiencies in their attributes or characteristics, and thereby reinforcing their non-belonging in that particular place. Unitary conceptualisations of identity can be rejected by those organising oppositional identities, for example, the Black Lives Matter activists argue that they are as important as white lives, should be acknowledged and valued as such because they are citizens of the same country, belong there as settlers, and should be treated as equals. These may, in turn, be rejected through political ideologies that seek to maintain a unitary state and can lead to eugenicist abuse and genocide, for example, Nazi Germany, Rwanda and indigenous peoples globally. Furthermore, unitary definitions of identity impact gender relations in deleterious ways for women. This is because women become symbols or signifiers of the nation-state (Yuval-Davis Citation2011) and are linked to maintaining men’s honour and masculinity. Consequently, these ideologies of identity reinforce women’s role in the home and under the dominance of men in patriarchal relations. This role of women is becoming increasingly important in an uncertain world where women insist on equality and challenge men’s dominance. This element is becoming increasingly apparent in the struggle to control women’s fertility and bodily integrity, occurring in countries as far apart as the United States and Somalia.

However, since the development of social movements, particularly those involving women, disabled people, and black, Asian and other ethnic minorities that demanded the realisation of anti-oppressive practice (AOP), practitioners have created oppositional identities that have rejected the status quo (Russo, O’Malley, and Severance Citation1988). Instead, social activists acknowledged identity as existing within a social context and central to a pluralistic view of individuals’ and communities’ sense of being (Who I am? Who are we?). They differentiated themselves as not belonging to the dominant or hegemonic group and rejected their being depicted as people who held subjugated identities as oppressed individuals or groups (Dominelli Citation2002a, Citation2002b, Citation2002c), and asserted their identities as multiple and liberational. Thus, anti-oppressive practice nurtured the idea that identity formation is a transactional relationship shaped and reshaped throughout people’s lives. Moreover, it becomes incorporated into practice when working with individuals, families and communities who are both the same as oneself and different from oneself. Additionally, the practitioner establishes particular understandings of identity by interacting and negotiating with others. These negotiations are transactional responses that involve power relations in which the practitioner is being configured by others at the same time as they are configuring the others. Transactional relationships in identity formation may configure identity in oppositional terms and elicit responses of:

Acceptance, namely the view that people are all the same and are assimilated into one unitary vision of their social identity.

Accommodation where there can be tinkering with definitions of identity at the edges, but the dominant version of identity remains unchallenged, for example, letting women enter public spaces with male relatives.

Resistance, where alternative visions of identity become established practices, even if rejected in specific policy responses, for example, LGBTQ+ struggles for acceptance globally.

Escapism may result in migration to establish oneself/a community elsewhere, for example, the Pilgrims leaving England to establish a new faith community (eventually) in the United States.

Participatory action research, which involves those who are “othered” in exploring their responses to the othering processes, would provide important evidence about their attempts to resist the dynamics of oppression. Studying the dynamics of oppression utilised by the hegemonic groups to perpetrate the othering of others is also an important research area, especially if those who are othered are to hold them to account and get them to terminate such practices.

Culture both affirms and (re)creates identities

Cultural discourses indicate the various visions of identity that co-exist in a society at any specific time. Culture contributes to the (re)shaping of identities as multiple, fluid and constantly changing. However, there are diverse views about what constitutes “culture” (Eliot Citation1949). Some cultures are seen as universal, others as relative (or sub-cultures), some are seen as fixed (natural and immutable), and others are seen as fluid and key to oppositional views of identity (Nastasi, Prerna, and Varjas Citation2017). In popular discourses, culture tends to cover a socially accepted nexus of knowledge, belief, religion, art, music, law, morals, customs and traditions that establish the social norms that define society and its members. This creates a common basis for people to interact with and accept the others living in their society.

Hegemonic definitions of culture and identity do not accept diversity and “other” those who are different. This gives a clear message of not belonging to that society and exclusion from its rights and benefits. However, such depictions of people’s positions in society are constantly challenged. Also, cultural changes occur through exchanges with others. Moreover, cultural interactions also rely on information systems and whether or not these perpetuate myths and cultural understandings that impact discourses about belonging, acceptance and having rights and entitlements to benefits. Some of these may exclude diverse groups of people with different cultures, and the outcome is more likely if the interactive processes between individuals and groups (re)frame them as “outsiders”. Considerations of the impact of agency in using culture as an asset in establishing a sense of belonging would also form an important issue for participatory action research to explore in the hopes of increasing the acceptance and celebration of difference amongst diverse social groups. Authoritarian leaders may deploy national pride and jingoistic ideologies to promote reward systems that enforce compliance; and organisational structures that endorse dominant norms formulated around a unitary national identity. In such situations, individuals decide whether they will accommodate their behaviour within their national culture, form sub-cultural enclaves within their society, or otherwise initiate change by forming groups with alternative framings of their society’s cultures.

Cultural transactionality or interactions create continuities and discontinuities in identity formation. These impact upon people’s understandings of the culture in which their identity is embedded. Continuities are based on elements that all members of a cultural entity or nation-state hold in common and can become a basis of oppression. Discontinuities are linked to changes in identity formation and what it represents. Such changes may challenge the conceptualisation of identity as a binary relationship. This binary relationship divides people into those belonging to the culture and those who do not. “Othering” promotes the exclusion of those defined as outsiders. Challenges to binary understandings of identity formation may lead to conflict, including armed conflict, as it did, for example, during the war in the Balkans in the 1990s.

Traditional social workers tend to think of identity in binary terms. They subscribe to unitary, fixed and essentialist views of identity and seek a toolkit to understand identity in multicultural social work. Doman Lum (Citation2010) argues that cultural competence comes from having an open attitude, becoming aware of oneself and others, having cultural knowledge, and acquiring cultural skills. This view treats culture as a unitary entity that can be acquired through a toolbox of identifying its constituent parts and applying them. Lum’s view of culture is insufficient as it does not explain change and variations in identity or culture as these occur among people and over time. Nor does it explain why certain people and cultures are preferred over others in many countries. Lum’s view was replaced through radical social work, which understood identity as a constantly negotiated process of identity formation and re-formation that enabled social workers to envisage identity as pluralistic, fluid and dynamic (Dominelli Citation2002a, Citation2002b, Citation2002c), not unitary and static.

Narratives of space and place

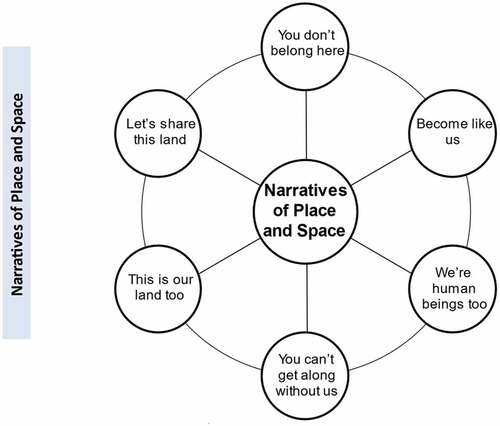

The narratives of space and place depicted in the chart below were developed through a content analysis of the descriptions of black, Asian and ethnic minorities in newspapers over one year (2006 to 2007) in Canada and the United Kingdom. The newspapers included in the study consisted of the major tabloids and broadsheets – the top six in each country. The findings are depicted pictorially in the chart below:

These narratives about belonging and identity are often expressed as struggles over land or territory. The responses varied from the oppressive rejection of difference to its inclusion within an egalitarian framework. I termed these the “narratives of place and space”. They were related primarily to racist discourses cast in binary formulations of either including or excluding those who were different. These narratives of space and place arose in the following formulations:

Segregation (you don’t belong here);

Assimilation (you become like us);

Multiculturalism (we’re human beings too);

Integration (this is our land too);

Interculturalism (we’re human beings too);

Anti-racism (we contribute much to society);

Black, Asian and Afri-centric perspectives (we contribute much to society); and

Egalitarianism that values diversity (let’s share this land) (Dominelli Citation2017).

Several of these discourses co-existed in any place at specific points in time. They enable practitioners to understand the implications of particular racist tropes to identity and the extent to which those who were different from the dominant group were accepted as “belonging” to that particular nation-state or not.

Intersectionality and identity formation

Identity formation involves intersectionality (Crenshaw Citation2017). Intersectionality describes the interaction between various social divisions involved in identity formation and argues that these interact with each other and do not occur in isolation. Thus, intersectionality challenges the dominant norms that focus on identity as occurring in binary formations – a dominant and a subordinate one. Binary concepts are used to validate unitary configurations of identity that are challenged by oppositional groups over time. Some of these key social divisions are:

Gender

Ethnicity (often confused with nationality, or “racial” group)

Age

Disability

Sexual orientation

Mental ill health

Class

Accent

Clothes

Religion and other cultural attributes and artefacts

Political ideology

Social workers can endorse identity as a pluralistic entity by affirming and valuing diversity and facilitating its expression in cultural artefacts and their creation, for example, challenging domestic violence and the abuse of women by re-storying the narrative that casts women as incapable of taking control of their lives.

Human rights, showing respect for and endorsing dignity for poor people

Excluding people from belonging to a society and thereby not granting the right to be seen as settled in a particular place leads to oppression and their exclusion from welfare benefits and participation in political structures. Social workers can intervene in these processes to uphold human rights (Reichert Citation2011; Healy Citation2008) among all groups, including migrants. People migrating for diverse reasons, including armed conflicts, have no human rights or benefit entitlements the moment they cross borders. Social workers can use Articles 22–27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in arguing for poverty eradication strategies because doing so would maintain human dignity (United Nations Citation1948). As George (Citation2003) expresses it: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for … health and well-being … [during] unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood”. Social workers can also employ the Social Development Goals (SDGs) to uphold human rights and eradicate poverty, especially around gender relations (SDG5). They can help local communities mobilise and organise to enhance their well-being and capacity to care for people, the environment and the planet. In this work, practitioners can also support demands for corporate accountability. Moreover, they can practice holistically to link personal attributes and ending structural inequalities like poverty (SDG1) in change endeavours. This includes the commitment to becoming culturally relevant and locality specific in their work so that they are questioning the idea that human rights are a Western idea through their practice. Many Eastern religions also have similar ideas about human dignity, respect, and a desire for equality.

Non-acceptance, non-belonging and differentiated experiences can lead to human rights violations. For example, women and children often have their human rights violated, especially in situations of armed conflict and war (United States Department of State Citation2003, 2010). This has led social workers to demand specific laws that meet women’s needs, around the right to be free from sexual and domestic violence and safe from human trafficking and smuggling. Women’s needs for bodily integrity led to changes in the Geneva Convention 1951 that enabled them to seek sanctuary if fleeing to avoid female genital mutilation, for example.

Indigenous peoples also have had their human rights, including land rights and rights to resources, abrogated under colonialism and neo-colonialism. Additionally, they have lost their family rights by having their children taken away and placed in establishments that prevented them from using their own language and maintaining links with their families back home. These practices were defined as cultural genocide. The United Nations (UN) affirmed indigenous rights in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007.

The United Nations has played an important role in promoting human rights, with oppressed groups such as women, black people (Collins Citation2000), indigenous people, and disabled people drawing upon social movements that each group established to push for change (Begum, Hill, and Stevens Citation1994; Shakespeare Citation1999). It has developed protocols and projects to promote change. However, UN efforts have not always borne fruit. Despite its many endeavours, the UN has failed to implement the equality of women globally. Moreover, one of its flagship statements, the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which aimed to secure an end to domestic violence against women and many other initiatives to promote gender equality, has yet to be fully realised. Organising a global research project among women to find out why this is the case would be a challenging but worthwhile research project.

Identity issues and trafficked women and children

The trafficking of women and children is an awful example of the failure of the UN to challenge effectively the patriarchal relations that seek to subordinate and exploit women and children. Trafficking is an exploitative, lucrative global business whereby 35.8 million people are enslaved yearly (Walk Free Citation2013). Mauritania, Haiti and Pakistan have the largest numbers of modern-day enslaved people. This is due to the high levels of forced marriage/labour and of women having to live in relationships that deny them agency (Wilson and Dalton Citation2008; Wilkinson, Craig, and Gaus Citation2009). Women who have been trafficked become stigmatised and feel significant shame linked to how they are defined culturally (Environmental Justice Foundation Charitable Trust Citation2015). Their human rights are usually violated throughout the trafficking process. Helping them deal with what has happened to them, to heal and move on involves investigation across a number of issues. These are not necessarily linear and highlight women’s lack of human rights and the right to define their own identity. They may be helped by:

Finding out the personal and structural factors that led to their migration/being trafficked.

Preventing their abuse when seeking protection.

Helping them not to be ashamed of being a victim-survivor.

Supporting their empowerment.

Strengthening their healing and recovery processes.

Assisting them in building a fulfilling future within a community.

Ensuring that they are identified as being part of the community they settle within.

Social services and some voluntary agencies work with trafficked women, for example, the Eaves Poppy Project. These affirm respect and dignity for women and seek to help them heal from the trauma of their distressing ordeal. However, such projects have insufficient funding to cater for the numbers of women requiring such resources. Consequently, trafficked women and children often suffer in silence behind closed doors, deprived of friends and other sources of support that could help them acquire independence and liberation from their exploiters who make money off their bodies.

Social work values, ethics and diversity

Egalitarian values are crucial to overcoming fear, oppression and the exclusion of those whose identities are outside the dominant unitary hegemonic identity norms (Arendt Citation1956). However, definitions of values and ethics may be varied and contested. Dominelli (Citation2002a) defines:

Values as the principles that guide daily life (guide morality).

Ethics as the codification of values to guide, regulate and sanction behaviour, especially in professional practice (for example, BASW code of ethics on https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/Code%20of%20Ethics%20Aug18.pdf) (The British Association of Social Workers Citation2020).

Values and ethics are personal, professional, corporate, cultural and religious, as is ethical behaviour. The conflict between different ethical principles produces ethical dilemmas. Western ethics are based on the Kantian principle of the respect for and dignity of the person (Banks Citation2012); social justice; and respecting human rights part of ethical practice. Human rights and social justice are values and practices that are crucial to empowering social work and owe much to radical and critical social work theories. Contemporary theorists want environmental justice included in social justice (Dominelli Citation2012).

Social work values that empower and celebrate communities are useful in resisting oppression and contributing to moral-ethical practice that values and celebrates diverse identities. Values have to be understood in specific contexts. For those following empowering, emancipatory social work, these values are:

Social justice;

Human rights;

Equality;

Solidarity and inclusion; and

Individual and collective empowerment.

These have been utilised in practice for some time. Marshall (Citation1950) championed civil, political and welfare rights as key to social work practice. The International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) had 19 social workers involved in drafting UDHR in 1947 to 1948 (Nations Citation1948). Nonetheless, social workers may find that upholding these values and promoting the acceptance of pluralistic, fluid and dynamic identities in the wider society is difficult. For example, the new ethno-nationalisms restricting vaccination sharing and solidarity are current examples of upholding the “them-us” binary, which means all humanity is constantly exposed to new variants of COVID-19. This outcome could have been avoided by showing global solidarity in sharing the vaccinations to cover all of the world’s inhabitants, regardless of where they lived. Moreover, the spread of the virus could have been avoided if humanity had not transgressed the human-animal barrier. When humans did, they carried the COV-SARS-2 into human societies, an action that led to the COVID-19 pandemic, and created a world of unprecedented deaths and economic disintegration. This disheartening scenario was offset somewhat by the re-discovery of community and recognition of the importance of treating nature with respect, and as an end in, of and for, itself. Caring for the environment and identifying with nature has been a significant outcome of COVID-19 for many.

Conclusions

An individual’s sense of identity is expressed in many different versions as it is fluid and context-dependent. More participatory action research is needed to uncover the lived experiences of those who are oppressed and how they resist this oppression in various ways. Values and ethics are important in enabling individuals to decide how to empower themselves and support others in achieving the same objective. Values and ethics also help us choose what to do when facing an ethical dilemma. This can occur when the “them-us” binary excludes those who are different and denies them access to services essential to leading a dignified life. Ethical dilemmas may be difficult to resolve and/or find a satisfactory solution. We may need to discuss these with others, for example, colleagues, friends, or line managers, if at work. Contemporary social work covers many subjects ranging from climate change to health pandemics like COVID-19 that create ethical dilemmas, especially if needs are high and resources few. Understanding yourself, your own identity, values, and ethics help you behave ethically in your practice. Self-knowledge also enables a practitioner with a knowledge of self that facilitates engagement with others who are different and provides the confidence of knowing that they can respond appropriately when helping them.

An important ethical principle for social workers as professionals is that of “doing no harm” to self or others. “Doing no harm” guides us in ensuring that we assist people in securing their health and well-being. Enjoying physical and mental well-being is critical to feeling that one’s identity has been accepted and enabling individuals and groups to feel that they belong. Knowing oneself is crucial to feeling comfortable in exercising your professional values and becoming accepted as a professional amongst equals and having much to offer. A professional identity also enables an individual to acquire social status (Welbourne, Harrison, and Ford Citation2007). However, personal and professional values may be in conflict and lead to an ethical dilemma, for example, when upholding women’s reproductive rights. A professional social worker committed to empowering women may have to refer a woman to someone else to enable her to obtain the service she requires. This would enable the professional social worker to retain his/her professional identity as a practitioner who provides a service user with the services they require, regardless of their personal views. Furthermore, the empowered woman would be able to identify herself as someone with agency and the capacity to make her own decisions. Understanding the complexity of the dynamics involved in identity formation and maintenance allow practitioners to treat identity as a fluid, interactional and constantly changing phenomenon. Such knowledge and understanding also facilitates the delivery of services appropriate to the person who has asked for assistance, and the solving of ethical dilemmas. Moreover, further research, preferably participatory action research that involves service users and practitioners through the research process can identify the questions that people in communities want answered about the realities of identity formation and maintenance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arendt, A. 1956. The Origins of Totalitarianism. London: Andre Deutsch.

- Banks, S. 2012. Ethics and Values in Social Work. 4th ed. London: Macmillan.

- Begum, N., M. Hill, and A. Stevens. 1994. Reflections: The Views of Black Disabled People on Their Lives and on Community Care. London: Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work.

- Biesteck, F. 1957. The Casework Relationship. Chicago, IL: Loyola University Press.

- Briskman, L., and S. Cemlyn. 2005. “‘Reclaiming Humanity for Asylum-Seekers: A Social Work Response.” International Social Work 48 (6): 714–724. doi:10.1177/0020872805056989.

- The British Association of Social Workers. 2020. “COVID-19 Guidance”. https://www.basw.co.uk/media/news/2020/mar/covid-19-guidance

- Collins, P. H. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. London: Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. 2017. On Intersectionality: Essential Writings. New York, NY: New Press.

- Dominelli, L. 2002a. Anti-Oppressive Social Work Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Dominelli, L. 2002b. Feminist Social Work Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Dominelli, L. 2002c. “Changing Agendas: Moving beyond Fixed Identities in Anti-Oppressive Practice.” Chap. 4 In Equalising Opportunities, Minimising Oppression: A Critical Review of Anti-Discriminatory Policies in Health and Social Welfare, edited by D. Tomlinson and W. Trew, 56–71. London: Routledge.

- Dominelli, L. 2012. Green Social Work: From Environmental Degradation to Environmental Justice. Cambridge: Polity.

- Dominelli, L. 2014. “Problematising Concepts of Citizenship and Citizenship Practices.” Chap. 1 In Reconfiguring Citizenship: Social Exclusion and Diversity within Inclusive Citizenship Practice, edited by L. Dominelli and M. Moosa-Mitha, 13–22. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Dominelli, L. 2017. Anti-Racist Social Work. 4th ed. London: Red Globle.

- Eliot, T. S. 1949. Notes Towards the Definition of Culture. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Environmental Justice Foundation Charitable Trust. 2015. “Thailand’s Seafood Slaves Report.” https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/EJF-Thailand-Seafood-Slaves-low-res.pdf

- Erikson, E. H. 1994. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company.

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-77. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Free, W. 2013. “The Global Slavery Index 2013.” Nedlands: Walk Free Foundation. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/global-slavery-index-2013/

- George, S. 2003. ““Globalizing Rights?”. Chap. 1 In Globalizing Rights, edited by M. J. Gibney, 15–33. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Healy, L. M. 2008. “Exploring the History of Social Work as a Human Rights Profession.” International Social Work 51 (6): 735–748. doi:10.1177/0020872808095247.

- Home Office. 2010. “Control of Immigration: Quarterly Statistical Summary, United Kingdom January-March 2010.” London: Home Office.

- Ife, J. 2001. Human Rights and Social Work: Towards Rights Based Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lorenz, W. 1994. Social Work in a Changing Europe. London: Routledge.

- Lum, D. 2010. Culturally Competent Practice: A Framework for Understanding Diverse Groups and Justice Issues. 4th ed. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA: Cengage Learning.

- Marshall, T. H. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nair, S. 2011. Human Rights in a Changing World. Delhi: Kalpaz.

- Nastasi, B. K., P. G. Prerna, and K. Varjas. 2017. “The Meaning and Importance of Cultural Construction for Global Development.” International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 5 (3): 137–140. doi:10.1080/21683603.2016.1276810.

- Nations, U. 1948. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” http://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf

- Reichert, E., ed. 2007. Challenges in Human Rights: A Social Work Perspectives. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Reichert, E. 2011. Social Work and Human Rights: A Foundation for Policy and Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Russo, H., S. G. O’Malley, and M. Severance. 1988. Disabled, Female and Proud! Stories of Ten Women with Disabilities. Boston, MA: Exceptional Parent.

- Shakespeare, T. 1999. “When Is a Man Not a Man? When He’s Disabled”. Chap. 5 In Working with Men for Change, edited by J. Wild, 37–46. London: UCL Press.

- Thompson, S., and J. Betts. 2003. “Community or Difference: Whither Anti-Racism(s) in Youth Work Practice?” In 20 Years of Youth and Policy, edited by P. C. Nolan, 1–17. Leicester: National Youth Agency.

- United States Department of State. “Trafficking in Persons Report 2003.” https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/21555.pdf

- Welbourne, P., G. Harrison, and D. Ford. 2007. “Social Work in the UK and the Global Labour Market: Recruitment, Practice and Ethical Considerations.” International Social Work 50 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1177/0020872807071480.

- Wilkinson, M., G. Craig, and A. Gaus. 2009. Turning the Tide: How to Best Protect Workers Employed by Gangmasters, Five Years after Morecambe Bay. Oxford: Oxfam.

- Wilson, J., and E. Dalton. 2008. “Human Trafficking in the Heartland: Variation in Law Enforcement Awareness and Response.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 24 (3): 296–313. doi:10.1177/1043986208318227.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2011. The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations. London: Sage.