Abstract

This article explores the photographs taken of the Red Army’s homecoming in the summer 1945. It examines what these reveal about post-war reconstruction and the re-establishment of communities. It argues that official demobilization photography was a carefully constructed and highly politicized attempt to visualize veterans’ reintegration, which subsequently structured war memory. The research is based on two forms of primary evidence, first the photographs and the visual evidence they contain, and second textual sources, including press accounts and archival documents, which reveal how these photographs were taken. The article examines the visual vocabularies and messages in photographs of soldiers departing from Berlin, and soldiers’ arrival in major cities, particularly Moscow and Leningrad. These images, for all their emotional power, were not representative of mass demobilization, but have been widely reproduced. Demobilization photography communicated important messages about post-war reconstruction, the reimposition of post-war gender norms, helping re-order and create post-war society.

Introduction

On 10 July 1945 the first troop train (eshelon) transporting demobilized soldiers to the Soviet Union departed from Berlin. Although a Soviet victory had been won nine weeks earlier, mass demobilization was just beginning. Demobilization plans were first announced on 23 June 1945, when the USSR Supreme Soviet passed legislation permitting the discharge of soldiers born between 1893 and 1905 (Antonov, Citation1945: 2; Anon, Citation1945a: 1). At this point, however, neither the Red Army nor Soviet civilians knew when soldiers would return. The intervening weeks were ones of nervous anticipation. Soviet soldiers were impatient to resume civilian lives, but anxious about homecomings and family reunions. All the more important, then, to appropriately mark the start of mass demobilization. The first eshelons were a set piece in the transition from war to peace pregnant with propaganda potential. Veterans returning home in the summer of 1945 were greeted by carefully choreographed ceremonies. These were major civic events. Locomotives decorated with flowers, greenery, slogans and portraits of Stalin, veterans hanging from their footplates, pulled into platforms crowded with women and children brandishing bouquets. Some of the most famous Soviet photojournalists were present to frame this symbolic moment. Their images, which circulated widely in the Soviet press, were instrumental in establishing visual languages, articulating key messages about post-war reconstruction, the rebuilding of families, and the transition from war to peace. Yet, as summer turned to autumn, and the initial flow of returning soldiers became a torrent, mass celebrations marking soldiers’ homecoming were curtailed. Demobilization’s visual image had, nevertheless, been fixed in public culture by the photographs taken in the summer of 1945.

This article explores the photographs taken during the first weeks and months of mass demobilization, a body of evidence neglected by historians of the Soviet Union’s post-war reconstruction. It analyses the visual vocabularies communicated in these images, the messages they transmitted about post-war recovery, and their rhetorical purposes. Official demobilization photographs, I argue, were carefully constructed images and highly politicized attempts to visualize veterans’ reintegration and the reconstruction of communities against a backdrop of war’s social and material wreckage. These powerful images helped create an official narrative of a ‘good peace’, drawing a clear distinction between war and peace where one did not necessarily exist. Photography established the cultural frameworks and paradigms through which soldiers’ homecoming have been understood ever since, even though most veterans were never fêted in the ways these images implied. Despite conflicting with most individuals’ experiences of demobilization, these photographs have enjoyed long afterlives. They have subsequently shaped and structured memories of post-war transition. Representations of demobilization in thaw-era cinema, late-Soviet painting, and post-Soviet commemorative activity reproduced and recycled the visual languages established in the summer of 1945. Whereas Khrushchev-era films utilized these images with a knowing eye, demonstrating an awareness of their constructed nature, their post-Soviet usage has decontextualized them, reshaping their original meaning and distorting memories of demobilization and post-war reconstruction.

This research draws on two main forms of primary evidence: first the photographs of demobilization and the visual sources which reveal their subsequent lives, and second textual sources, including press accounts and archival documents, which reveal the circumstances in which these photographs were taken. After a methodological discussion about the evidential value of Soviet photography, and a survey of recent research employing visual and photographic methodologies, the article comprises three main sections. The first analyses the visual vocabularies, grammars, and messages that run through the photographs of soldiers departing from Berlin. The second continues this examination of visual languages by focusing on photographs of veterans’ arrival in major cities, especially Moscow and Leningrad. It contrasts these images of a joyous return and national celebration taken in the summer of 1945, with less well-known images more typical of mass demobilization. A third section examines the afterlives of these images, and how they have been subsequently reproduced, recycled, and reinterpreted. It considers what the reuse of these images reveals about shifting memories of post-war reconstruction, and the continuing power of photography to communicate messages about the post-war world.

Approaches to Soviet visual histories

Photographs are neither ephemeral snapshots, nor transparent windows into the past. Seductive and treacherous, alluring and dangerous, photographs pose serious methodological challenges as historical evidence (Burke, Citation2001; Burke, Citation2008: 436; Sontag, Citation2008). This is particularly the case with Soviet photography, which enjoys a reputation for falsification. Stalin-era photography is associated with images from which purge victims have been disappeared, or where the faces of ‘enemies’ have been obscured by ink blots (King, Citation1997). More commonly press photographs were retouched or assembled through photomontage (Plamper, Citation2012: 36, 38) (Shneer, Citation2020: 11). Yet, outside the highly charged political context of Stalinism, photographs were no less carefully constructed. Photographs frame, structure, and distort reality, in ways which alter the meaning of the moments they capture (Tagg, Citation1988: 1–4). Whether photographs are false or true is less important than the mistaken inferences drawn from them. As Errol Morris quips, ‘Photographs attract false beliefs the way fly paper attracts flies’ (Morris, Citation2011: 92).

All too often photographs have been reduced to illustration, without considering what they reveal about the societies that produced them. They are more than straightforward material traces of the past; they are active agents in the creation of the past. Photographs framed a moment in time, but also shaped its meanings. As Jennifer Evans writes, ‘Images changed how people understood themselves, and conditioned how they related to their world, their bodies and selves’ (Evans, Citation2018: 7). During and after the Second World War, photography played a critical role in marking victory and visualizing the transition from war to peace. Iconic images of victory enjoyed long afterlives, becoming cultural icons which subsequently structured war memories. Apart from Evgenii Khaldei’s influential photographs of the Victory Banner being raised above the Reichstag, the role of photography in shaping the Soviet Union’s post-war reconstruction has been largely unexplored (Hicks, Citation2020). In 2010 the editors of Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History encouraged scholars, ‘to work towards a more informed position of how particular societies expressed themselves in visual culture: what their visual resources were, how they were deployed, and to what social and political ends’ (Anon, Citation2010: 217–20). Such injunctions are bearing fruit. Excellent histories of Soviet photographic practice amongst amateurs as well as professional photographers now exist (Anon, Citation2017) (Werneke, Citation2019). David Shneer’s inspirational work on Soviet Holocaust photography serves as a model for examining the constructed nature of photographs, and the long and complicated afterlives which turned them into ‘repositories of memory’ (Shneer, Citation2010; Shneer, Citation2012) (Shneer, Citation2020). Claire McCallum’s pathbreaking work on the representation of post-war masculinity has explored the role of visual culture in shaping homecomings and post-war transition (McCallum, Citation2015a; McCallum, Citation2015b; McCallum, Citation2018). While McCallum concentrates on drawings, cartoons, posters and paintings, and their role in reconstructing masculinity, this article explores demobilization photography and its role in reconstructing community. Demobilization left a rich visual archive, which with the right methodologies reveals much about how late Stalinist society sought to overcome the social and material wreckage of war. Photographs of returning veterans were critical in creating the post-war world, establishing the boundaries between war and peace, rebuilding Soviet society in the process.

Photographs of departure – establishing an aesthetic

On 10 July 1945 Krasnaia zvezda (Red Star), the Ministry of Defence’s newspaper, carried an article describing the final days before a group of riflemen’s demobilization, and the ceremonies that marked their departure. This was accompanied by two photographs taken by A. Kapustianskii, Krasnaia zvezda’s photo correspondent, depicting a party meeting and the moments when officers formally said goodbye to their troops. At this early stage, a new demobilization aesthetic was still nascent, but in the coming days and weeks photographers and their press editors took decisions that created new visual languages appropriate for post-war reconstruction. Photo-correspondents focused their lenses on demobilization echelons, especially decorated locomotives and groups of soldiers gathered around or within wagons decorated with slogans, banners, and portraits of Stalin. These were not casual snaps taken by soldiers for posterity, but carefully constructed images that captured propagandists’ vision of how an idealized demobilization should proceed. One might ask how many ways of photographing demobilization were conceivable, and whether the focus on demobilization trains was natural. Yet, Kapustianskii's photographs of soldiers filing past rostrums or gathering to hear political speeches indicate that there were visual alternatives. Furthermore, soldiers created their own photographic records of demobilization, concentrating on individual and group portraits taken before tightly bonded combat groups were dissolved by demobilization (Schechter, Citation2019: 232).

Many photographs of the first demobilization echelon’s departure from Berlin on 10 July 1945 survive. As befitted a key moment in the transition from war to peace attention was paid to its visual image, not just for the benefit of participants but also the photographic record. At least four leading photographers, Evgenii Khaldei, Natalia Bode, Viktor Temin, and Anatolii Arkhipov, photographed this occasion. Confirming who was behind the camera, and that these images were taken on the same day, requires some detective work, especially as the photographers are often unidentified or misattributed. Although they photographed common elements, the multiple images, shifts in position and composition allow us to examine how these influential images were constructed, and the propaganda messages that enveloped soldiers’ embarkation.

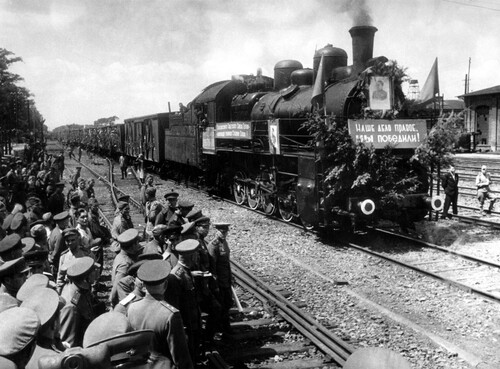

Trains featured prominently in these photographs. As a long-established Russian and Soviet symbol and visual metaphor of modernity this was hardly surprising (Shenk, Citation2016). The use of trains for agitational purposes was nothing new and could be traced back to the Russian Civil War (Taylor, Citation1971; Kenez, Citation1985: 59–62; Heftberger, Citation2015). Several photographs of the locomotive were taken from different angles, with different exposures and lighting, including , but are all recognisable as echelon number 679-18. The portraits of Stalin and the slogans adorning the locomotive hammered home key messages about Soviet victory. A placard adorning the locomotive’s boiler hailed Stalin as the Generalissimus and a Hero Commander; another declared, ‘Our cause was just. We were victorious!’ (RGAKFD, 0-255739). Far more visually arresting were the decorated wagons, and the groups of soldiers gathered in and around them. Slogans and exhortations to greet the nation’s heroes were painted onto boards attached to their roofs. Evgenii Khaldei photographed the occupants of one wagon sporting the slogan, ‘We have come from Berlin!’ (My iz Berlina!) (). Several of these photographs were printed in the local and national press in the coming days (Khaldei, Citation1945: 1). In time these became iconic Soviet images with long afterlives.

FIGURE 1 Evgenii Khaldei’s photograph of the demobilization echelon departing from Berlin on 10 July 1945. Reproduced courtesy of Picture Alliance/DPA/Bridgeman Images.

FIGURE 2 Soldiers wave off the famous My iz Berlina! (‘We have come from Berlin!’) carriage, Berlin, 10 July 1945. Reproduced courtesy of akg images.

Although slogans varied, decorations were standardized along the length of the train. Propaganda posters, quotations from Stalin’s speeches, and garlanded portraits of Stalin were posted on every wagon. Brass bands and soldiers playing accordions made this an aural as well as visual experience. Photographers picked out copies of Viktor Ivanov’s poster Raise the Banner of Victory over Berlin (1945) (Vodruzim nad Berlinom znamiia pobedy!), and Boris Karpov’s 1944 portrait of Stalin. In several of Khaldei’s photographs, Stalin’s portraits catch the light, creating a shining radiant leader. Stalin’s symbolic presence was strong in these images. Although war veterans were returning as heroes, the ultimate victor remained Stalin (Plamper, Citation2012: 56–81). The decoration of demobilization trains, however, served both propaganda and practical purposes. Slogans, portraits, posters, and garlands helped to distinguish these boxcars from those used to deport whole nationalities before, during, and after the war, or to transport prisoners to distant outposts of the Gulag. Without these decorations, photographs of eshelons might have prompted the wrong associations. This was a carefully choreographed ceremony, prepared by an army and political regime which appreciated the power of political ceremony and ritual.

The prominence of female veterans in these photographs was surprising. One group of women were photographed in a boxcar underneath a banner which read rather incongruously ‘We have paid the Germans back completely. Greet the sons of our native country!’ The presence of these women needs explanation. Women were only eligible for demobilization after a second wave of mass demobilization was announced on 25 September 1945, having been excluded from the provisions of the 23 June demobilization legislation (Anon, Citation1945j: 1; Anon, Citation1945k). In mid-October the popular weekly Ogonek published two photographs by Anatolii Arkhipov documenting the supposed beginning of women’s demobilization, again deploying visual languages established in July (Anon, Citation1945l: 1). Nevertheless, women were well represented in this first echelon to depart Berlin.

Careful examination of one striking image, reproduced in , helps explain the women’s presence and reveals important messages about the transition from war to peace. Natalia Bode, a distinguished wartime photo-correspondent, photographed a remarkable group of veterans gathered in the doorway of a boxcar decorated with greenery. None of the slogans, portraits, and formal trappings of propaganda are visible. A female veteran seated at the front of the wagon is the focus of the image. Her light clothing catches the light, as she holds a doll aloft. Gathered around her are three battle-hardened men, deeper in the frame are another four female veterans. On the left, another woman cradles a smaller doll with similar reverence. Everybody smiles, seems happy and relaxed in an image that radiates harmony between the sexes, even though gender relations in the Red Army were tense (Krylova, Citation2010). The focus on these women makes sense when we consider who they were. Another photograph taken by Bode on 10 July captured four female veterans, their uniforms proudly adorned with medals, with the familiar carriages in the background. From the configurations of their medals, uniforms, and familiar faces, these women can be identified as members of 3rd Belorussian Shock Army’s female sniper unit. Vladimir Grebnev took a series of photographs of this unit in Berlin’s environs for Frontovik, the 3rd Belorussian Shock Army’s frontline newspaper, days before mass demobilization got underway. The salient point, however, is that these women were snipers, highly trained and successful killers, threatening to Soviet gender norms. They needed, therefore, to be reintegrated into civilian life more quickly than the hundreds of thousands of women serving in support or medical roles (Krylova, Citation2010: 241–56; Markwick and Cardona, Citation2012: 51–5, 221–3).

FIGURE 3 A group of veterans photographed by Natalia Bode, Berlin, 10 July 1945. This photograph and several others of this demobilization echelon can be accessed at https://en.topwar.ru/29894-natalya-bode-voyna-glazami-zhenschiny.html (Last accessed 4 February 2022).

This was a highly constructed image, posed to communicate important messages about the reconstruction of society, community, and the reimposition of conventional gender relations. That these women posed with dolls, cradling them as they might their own infants, was no accident. The presence of the dolls requires explanation. Bode may have introduced them as props, or more likely they were pulled from kit bags, having been stashed as valuable ‘trophy’ items destined for the black market or gifts for children back home (Merridale, Citation2005: 278–9; Edele, Citation2008: 30–3, 62–4; Schechter, Citation2019: 212–42). More important than how the image was staged, however, were the messages it communicated about the rebuilding of Stalinist gender relations, and repairing the demographic hole wrought by war. These women returned not only as veterans, but also potential reproductive units, and future hero mothers. While the middle-aged men in this photograph could return to their families, if they survived, these younger women had the additional responsibility of bearing children and building new families. In this respect Bode’s photograph was a visual reinforcement of the pronatalist message of N.S. Khrushchev’s 1944 Family Law (Nakachi, Citation2006; Nakachi, Citation2021).

The visual tropes established in the first days of mass demobilization stuck. Olga Lander’s photographs from Vienna that summer, taken for the frontline newspaper Sovetskii voin (Soviet soldier), shared a similar visual vocabulary: veterans hanging from carriages, accordionists and wind bands giving send offs. Demobilization was framed in similar ways (Blank, Citation2018: 11–27, 148–9). When Viktor Temin photographed demobilization echelons departing Berlin in 1955 and 1956, he drew upon the visual languages employed in May 1945.Footnote1

Photographs of return – reuniting communities

Images of departure quickly gave way to those of arrival. Within days arresting images of returning soldiers greeted by jubilant crowds proliferated, developing the visual vocabularies established in Berlin. Surprisingly, however, the arrival of the first departing echelon was not celebrated in the national press, perhaps because it was bound for Minsk. Vladimir Lupeiko, TASS’s photo-correspondent in Minsk, photographed the My iz Berlina! wagon, identifiable by its wagon number, decorations, and passengers, being greeted by civilians, although precisely when is unclear.Footnote2 The first widely circulating photographs of returning soldiers, in this case returning from Estonia and Latvia, were taken by Boris Utkin at Leningrad’s Baltic Station on 12 July 1945 (TsGAIPD-SPb, f.24, op.2v, d.7023, l.75) (TsGAKFFD SPb), (Ar270763, Ar36709) (Anon, Citation1945b: 2). The following day 1,307 veterans arrived at Leningrad’s Finland Station, where they were photographed by TASS photo-correspondent Vasili Fedoseev (TsGAIPD-SPb, f.24, op.2v, d.7023, l.75) (TsGAKFFD-SPb, Ar27072, Ars7072, Ar37081). A further 1,329 demobilized soldiers arrived at the Warsaw Station from Latvia on 14 July (TsGAIPD-SPb, f.24, op.2v, d.7023, l.75). These photographs captured the joy and excitement which surrounded veterans’ return, deploying common visual tropes of smiling soldiers bedecked with medals, joyous women proffering kisses and bouquets, and small children held aloft. Although the emotions of the crowd and veterans were almost certainly genuine, these were highly choreographed celebrations. A successful ritualized homecoming required careful preparation. Not all crowds gathered spontaneously. Delegations of between 500 and 1,000 workers and agitators were mobilized from nearby factories and enterprises to greet veterans (TsGAIPD-SPb, f.24, op.2v, d.7023, l.88). Frantic preparations were made to ensure stations were fit to receive heroes. Komsomol cells were mobilized to decorate platforms with flowers, posters, slogans, and portraits of Stalin (TsGAIPD-SPb, f.K-598, op.5, d.232, ll.16-17) (Anon, Citation1945c: 2).

A series of photographs, including , taken by David Trakhtenberg, Leningradskaia pravda’s staff photographer, at Leningrad’s Baltic Station on 15 July 1945 enable us to see demobilization photography’s careful construction (TsGAKFFD-SPb, Ar110406, Ar99074, Gr64654), (RGAKFD, 0-106426). Trakhtenberg singled out a young woman in a light-coloured knee-length dress extending a bouquet to a column of veterans waiting in the background. The same woman was photographed amidst a group of women offering bouquets to veterans emerging from the doorway of a boxcar. Boris Utkin’s photograph of the same group, albeit with a different woman foregrounded, was published in Krasnaia zvezda (Utkin, Citation1945, 3). These photogenic women evidently caught photographers’ attention. In a city where at least 800,000 people had starved in a murderous siege, and where the physical effects of mass starvation were inscribed on the thinned and weakened bodies of Leningraders, this fit and healthy woman warmly welcoming home male soldiers conveyed messages about the reconstruction of society, the healing of wounds, and the recreation of normal gender relations (Reid, Citation2011; Bidlack & Lomagin, Citation2012; Peri, Citation2017).

FIGURE 4 Veterans arriving at Leningrad’s Baltic Station, David Trakhtenberg, 15 July 1945, TsGAKFFD-SPb Ar110406. Reproduced with the permission of the Central State Archive of Documentary Films, Photographs, and Sound Recordings of St. Petersburg.

The photographs of the first trains arriving in Moscow, the centre of Soviet politics and power, carried greater symbolic potential. These were more sophisticated receptions than in Leningrad. The experience of hastily arranging mass celebrations for Victory Day on 9 May and the Victory Parade on 24 June 1945 had honed the symbolic tools available to Moscow’s propagandists (Rolfe, Citation2006: 181–3; Hicks, Citation2020: 41−50). Published documents from meetings of the Moscow City Party’s Executive Committee reveal the extensive and detailed discussions and planning that surrounded soldiers’ reception (Anon, Citation2000: 44–52; Gorinov et al., Citation2000: 298−303). Moscow’s mass celebrations were more than practical logistical challenges, they communicated more forceful messages about post-war reconstruction, which circulated widely. Photographs of jubilant crowds of women and children waving bouquets, and poignant shots of family reunions, were added to demobilization’s visual vocabulary. The arrival of the first echelons at Moscow’s Rzhevskii station on 17 July 1945 and at Moscow’s Belorussian station on 21 July 1945 were grander and more carefully choregraphed than anything in Leningrad. Once again frantic preparations were made to ensure veterans were greeted appropriately, including ensuring that photographers, journalists, and filmmakers were present to frame the moment for posterity. Veterans themselves had to be ready for the performance. On 17 July a report published in Vecherniaia Moskva, Moscow’s evening newspaper, described veterans readying themselves for homecoming. At a halt on the approach to Moscow, soldiers jumped out of their wagons to wash, shave, brush-down uniforms, and shine boots (Anon, Citation1945e: 2). Presumably, the decorations, slogans, portraits, flowers, and greenery adorning trains also had to be re-adjusted. An article in the trade union newspaper Trud described the nervous anticipation and preparations Moscow’s citizens made ahead of the train’s arrival. ‘Thousands of people came onto the streets with giant banners. All of their faces were radiant, their eyes sparkled. People sang songs, went up to each other without formality, shook hands, expressed warm sincere words. It seemed as if one huge family had come out into the streets’ (Anon, Citation1945f: 1).

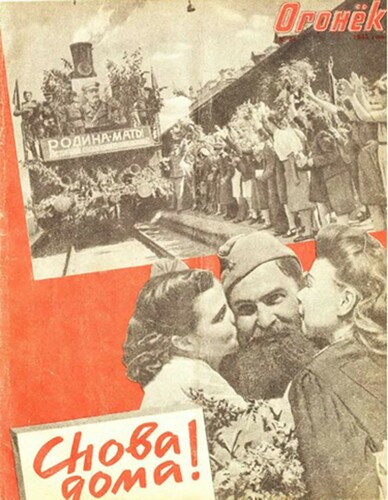

The photographs from the Rzhevskii station from 17 July 1945 were a celebration of victory and homecoming, carrying messages about the recreation of community and restoration of normality. Railway platforms and the squares in front of stations became contact zones where frontline soldiers and civilians encountered each other after a long period of separation. The photographs and accompanying articles created the impression of a society reunited after the experience of a damaging and divisive conflict. The press highlighted heart-wrenching stories of the reunion of wives and husbands, and of fathers and their children hardly recognising each other (Anon, Citation1945d: 1; Tsiurupa, Citation1945a: 3; Anon, Citation1945g: 1; Anon, Citation1945h: 3). As in Leningrad, the photographers picked out a visually striking individual, in this case a stocky veteran sporting a prodigious beard. Here was a modern-day bogatyr. Like the knights of Slavic folktales, blessed with superhuman strength, courage, and an impressive physical presence, he was returning to universal acclaim. He was photographed surrounded by women and his comrades as he stepped off onto the platform, and as he was hugged and kissed by several women (RGAKFD 0-255739). S. Korotkov photographed the same veteran being reunited with his son in Georgia.Footnote3 If there was any doubt that this veteran was being presented as the face of demobilization, Ogonek’s cover on 5 August 1945 () ran a photomontage of the locomotive’s arrival into the Rzhevskii station on 17 July, including a half page image of this veteran being kissed on the cheeks by two women. A stylized placard in the bottom left of the cover reads ‘Home again!’ (Anon, Citation1945i). These were carefully composed and constructed images, staged to communicate a point about the reunification of families, reconstruction of communities, and the transition from war to peace. That the same man posed with a variety of different people mattered less than the signals these photographs sent about post-war reconstruction.

FIGURE 5 The Front cover of Ogonek, No.31 published on 5 August 1945, a montage of photographs from Moscow’s Rzhevskii Station taken on 17 July 1945.

The photographs taken of the arrival of a further demobilization echelon on 21 July 1945, this time at Moscow’s Belorussian station, were the most arresting. Having established the visual vocabulary of demobilization, photographers were perfecting their compositions. The huge crowds which gathered in and around the Belorussian station added to the drama of the images. According to Krasnaia zvezda, ‘Thousands of people filled the platforms and square in front of the Belorussian station. Wives, mothers, children and simply unacquainted people arrived at the station in order to greet the heroes’ (Tsiurupa, Citation1945b: 3). A panoramic photograph published in Ogonek on 5 August, spanning a double page, documented the extraordinary crowds. As the accompanying article put it, ‘Moscow met (the demobilized) with a deafening noise of an orchestra of applause, cheers of welcome. The platform and area in front of the station was flooded with people, there were so many flowers in the square, that it seemed that all of the city’s shops had been scoured, all the flowers had been gathered, even the very last camomile flower from the meadows around Moscow’ (Repina & Rusakova, Citation1945: 8–9). Several photo-correspondents, including Arkardii Shaikhet and A. Kapustianskii, photographed the train pulling into the platform, and the expectant crowds packed onto the platform. These photographs shared similar compositions (RGAKFD 0-308633, 0-106422, 0-260775) (Kapustianskii, Citation1945: 3). Other photographs, including , depicted veterans mobbed on the platform by the jubilant crowds. The photographs taken in Moscow in those heady days in July 1945 were a visualization of the zabota (care and attention), which was supposed to envelop soldiers throughout demobilization. They helped create the enduring myth that soldiers were welcomed home to universal acclaim, were treated as heroes, and were successfully reintegrated. These powerful and emotionally charged photographs have framed the interpretation of demobilization ever since, connecting soldiers’ homecoming with festive receptions and cheering crowds.

FIGURE 6 Veterans arriving at Moscow’s Belorussian Station on 21 July 1945, photographed by Arkadii Shaikhet. Reproduced courtesy akg-images/fine-art-images.

Most veterans, however, never received a heroes’ welcome. It was not possible to sustain the intensity of agitational activity around demobilization for long. Once troop transports began arriving daily, returning tens of thousands of veterans every week, the crowds lost interest. Once the novelty wore off, ex-servicemen were greeted with less fanfare and eventually silence (Merridale, Citation2005: 312). Gone were the crowds brandishing wilting flowers, the decorations, and tribunes of dignitaries (TsGAKFFD-SPb Ar27075 and Ar27068) (Anon, Citation1945m: 3). For many soldiers the journey home was an ordeal; delays, over-crowded and dilapidated trains, and violent disturbances could make travel a nightmare (Edele, Citation2008: 22–30; Slaveski, Citation2013: 37–8; Edele and Slaveski, Citation2016: 1029). Soldiers stranded in sidings were photographed relaxing on wagon roofs rather than arriving triumphantly (GAAO, No. 0-6367). War-ravaged communities, especially in rural areas, had few resources to invest in grand welcome home receptions. From 1946 onwards, Party Control Commission reports investigating political work amongst veterans bemoaned the lack of organized receptions for returning soldiers, and inadequate agitational activity once they arrived. A report from the Party Control Commission’s representative in Sverdlovsk dated 6 August 1946 observed that veterans demobilized as part of a third wave had as a rule not been greeted by delegations from party or government organizations.

Of 26 echelons arriving in Sverdlovsk with demobilized (soldiers) in the course of May, June, and July, in part of which were residents of the city of Sverdlovsk and the region, representatives of party and soviet organizations met only 3 echelons.

For all their visual and emotional power, the photographs taken in mid-July 1945 do not capture the complicated reality of demobilization as experienced by millions of soldiers over more than three years. Camera lenses froze genuine moments of joy in time, establishing a post-war emotional regime for demobilized soldiers, but enthusiasm for homecoming was often counterbalanced by trepidation. As Merridale writes, ‘Perhaps the festive mood carried the soldiers through the shock of coming home, but there is no doubt that it was a tense and terrifying time’ (Merridale, Citation2005: 309). Soldiers occasionally broke down on the journey. On the night of 25/26 April 1947 a group of demobilized soldiers travelling home noticed that one of their comrades was behaving strangely. He began to speak nonsense, tried to throw himself from the wagon, but only succeeded in throwing away part of his papers. He could not sleep, refused all food, and was emotionally and psychiatrically disturbed. When the echelon passed through Kharkiv, the distressed veteran was removed from the train, and admitted to the Ukrainian Republican Neurosurgical and Neuropsychiatric Hospital for Invalids of the Great Patriotic War (TsDAVO, f.4852, op.1, d.21, l.27). Many soldiers had good reason to be concerned about readjusting to family life, others were emotional about leaving their comrades behind. In an article published on 10 July 1945, Krasnaia zvezda acknowledged the mixed emotions returning soldiers might experience. For years soldiers had, ‘slept side by side, eaten from one common pot, and at times even smoked the same cigarette together’ (Zotov and Borisov, Citation1945: 3). Leaving the close bonds of military life behind could be a wrench. Perhaps this was why soldiers’ own photographs concentrated on their immediate primary groups. Homecoming, however, was often the beginning of a long and difficult process of readjustment. Securing work and housing, locating relatives, obtaining the correct documents from obstructive bureaucrats, whilst dealing with mental and physical trauma created intractable difficulties. Finding one’s place in communities which had changed immeasurably, against the backdrop of late Stalinism’s hardships, was not straightforward. Enthusiasm for the war’s end often gave way to resentment, cynicism, and disillusionment as veterans’ wartime sacrifices were forgotten (Dale, Citation2010).

Photographs taken in the first weeks of demobilization became emblematic, but not representative. They excluded many. Photographs of arrival, unlike those of departure, excluded women veterans. There were no photographs of central Asian veterans amongst the demobilized. By concentrating on Moscow and Leningrad, the photographic record reinforced the increasing Russo-centrism of late-Stalinist politics and public culture. Demobilization photographs depicted proud victors, patriotic Russians, not men dismembered by war. The war-disabled were released directly from military hospitals as individuals or in small groups, excluding them from organized celebrations. The veterans photographed in the summer of 1945 were able-bodied, had established life-courses, and were more likely to enjoy family support. Cameras tended not to dwell on the bereaved. Younger veterans demobilized in 1946 and 1947, who often had the greatest difficulty readjusting to civilian life, never received anything approaching the public acclaim of the first weeks of demobilization (Dale, Citation2015: 20). The photographs taken July 1945 obscured a more complicated history.

The afterlives of demobilization photography

Other ways of photographing demobilization did emerge. The press carried images of the facilities for returning soldiers organized at railway stations, or articles describing family reunions accompanied by photographs of veterans crossing the thresholds of their homes (Kapustianskii and Khomzor, Citation1945: 3; Olekhnovich, Citation1945: 1; Popova and Kollts, Citation1945: 14–16). Photographs of former soldiers re-entering the workplace, many still wearing their uniforms, became commonplace. Yet, whenever Soviet and post-Soviet society attempted to picture demobilization they reached for the powerful images taken and the visual languages established in July 1945. To quote David Shneer, ‘By contrasting iconic photographs with their original photojournalistic images we can see how photographs function as photojournalism in emerging narratives, and then as art photography in the construction of war memory’ (Shneer, Citation2012: 230). These photographs became ‘arbiters of memory’, images that subsequently structured the collective memory (Shneer, Citation2012: 208). As iconic images they enjoyed long afterlives, routinely reproduced in posters, academic histories, popular photographic albums, websites, and commemorative materials.Footnote4

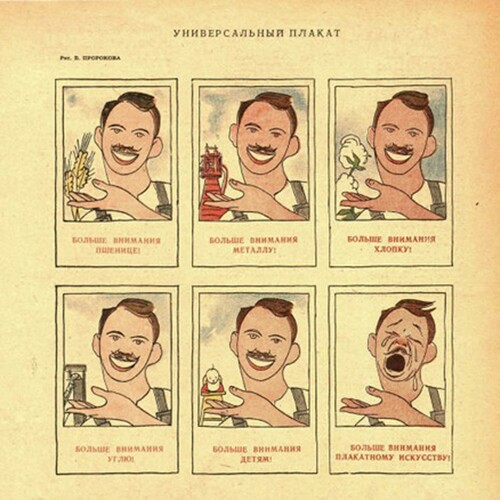

Late Stalinist citizens, however, were conscious of how highly constructed demobilization photography was. Soviet citizens had a subtle relationship with official propaganda; official messages were not internalized wholesale (Berkhoff, Citation2012: 274–9; Brandenberger, Citation2011). Many citizens appreciated the dissonance between propaganda and their own experiences. As Jonathan Waterlow has demonstrated, Soviet citizens were capable, in certain circumstances, of poking fun at propaganda, policies, and overblown campaigns (Waterlow, Citation2018: 71–104). They looked at posters, paintings, and photographs with a knowing eye, appreciating their constructed nature yet still discerning the intended ideological message. On 10 May 1947 the satirical journal Krokodil published a cartoon entitled ‘The Universal Poster’, () which poked fun at the lack of imagination in poster design. Five posters are depicted, each with the same man’s profile gesturing to an economic or social sphere in which greater attention needs to be paid. A sixth poster shows the same man, now in tears, with the caption ‘Greater attention to poster art!’ (Prorokova, Citation1947: 10) A certain visual sophistication was required to laugh at this joke; living under Stalinism’s symbolic regime encouraged a certain visual acuity. Demobilization photographs spoke to powerful emotions and memories, but over time their meanings shifted. The visual vocabularies established in the summer of 1945 subsequently informed a range of late socialist cultural products, but these framed and remembered demobilization differently. Filmmakers, in particular, drew upon this familiar imagery, even though soldiers’ return only looked like this in a few cities for a short period. Some notable films, however, demonstrated a more subtle appreciation of demobilization’s realities than expressed in Stalin’s final years.

FIGURE 7 B. Prorokova, ‘The Universal Placard,’ Krokodil, no.13, 10 May 1947, 10, an image which pokes fun at Soviet poster design and indicates the knowing eye through which Soviet citizens viewed visual propaganda.

Mikhail Kalatozov’s Citation1957 film The Cranes are Flying (Letyat zhuravli), one of the most critically acclaimed of Thaw films, contained a closing scene which dramatized the arrival of a demobilization echelon in Moscow (Kalatozov, Citation1957; Youngblood, Citation2007: 118–21). Jubilant soldiers hanging from a train like those photographed on 17 and 21 July 1945 pull into a platform, where joyful crowds have gathered to greet them. Among the crowd is Veronika, the film’s central protagonist, who is forlornly hoping to be reunited with Boris, her true love. Although she has been informed Boris was killed in action, an episode which viewers have already witnessed, she still hopes to find him on the train. This scene echoes the iconic demobilization photographs, employing the same visual elements and atmosphere. The train is decorated with banners, slogans, and greenery, although de-Stalinization means that portraits of Stalin have disappeared. Joyful crowds brandishing wilting bouquets envelop the returning heroes, veterans hug relatives and hold babies aloft. Veronika, a character with whom the audience develop a deep empathy, however, never finds Boris. Her friend Stepan tragically confirms Boris’s death. As Veronika breaks down in tears, Stepan delivers a speech standing on the locomotive stressing that, ‘the happiness of our reunion is immeasurable. The heart of every Soviet person is filled with joy. Joy sings in our hearts. Victory has brought us this joy.’ The juxtaposition of these words with Veronika’s grief is striking. For many Soviet viewers Veronika’s situation was a revelation, an honest expression of the reality that the joyous post-war reunions were the exception rather than the rule. As Josephine Woll notes: ‘Cranes transformed the way that viewers and reviewers considered war trauma and their expectations of cinematic representations of it’ (Woll, Citation2000: 73–4). The film was a reminder that in the wake of war there were as many mourning the dead as celebrating reunions. The message that demobilization left many women isolated and bereaved was also central to Ivan Babenko’s painting Waiting, 1945 (1975). It depicted a young-women standing at the end of wooden railway platform as the decorated brake-wagon of a demobilization echelon pulls out of view, against a backdrop of wartime destruction. She is left waiting, deprived of a joyful reunion. In both this painting and the closing scene of The Cranes are Flying familiar visual vocabularies were deployed to communicate subtle messages about the limitations of post-war reconstruction, and the difficulties of rebuilding family and community.

Andrei Smirnov’s 1970 film Belorussian Station (Belorusski vokzal) had no need to restage veterans’ demobilization, because it used the newsreel footage shot at the Belorussian station on 21 July 1945 (Smirnov, Citation1971; Youngblood, Citation2007: 155). The film follows the post-war fate of four men and a female nurse demobilized that day. The film ends with four-minutes of footage depicting the same elements, images, and people as the still photography. Rather than joy, this film is suffused with the characters’ disappointment, disenchantment, and disorientation. Even for individuals at the centre of the demobilization spectacle, post-war life had not turned out as envisaged. The closing scenes of the film questioned the official narrative of the smooth reintegration of veterans into civilian life, showing how notions of universal acclaim, respect, and zabota, conflicted with individual experiences.

Yet with time and the recycling of photographs, their subtle contexts and propaganda functions began to be forgotten. Shorn of their historical context, and ignoring the circumstances of their creation, these images became symbols of post-war recovery and reconstruction. The knowing eye of late Soviet film gave way to less critical interpretations of these visual languages. Images of homecoming, drawing on photography from the summer of 1945, have been harnessed as part of the official memorialization of Soviet victory. In July 2012, to mark 175 years of railways in Russia, the state-owned Russian Railways company released a minute-long advertisement connecting railway travel and key moments in the national past.Footnote5 The video included shots of a demobilization echelon and the famous My iz Berlina wagon steaming home. Although the actors were younger than the original veterans, and portraits of Stalin were replaced by a patriotic slogan, these were visual quotations of Evgenii Khaldei’s photographs from the 10 July 1945, and L. N. Kapeliush’s photographs of the first echelon arriving in Gorky (GArkhADNO, arkh. no.143). That Khaldei’s shots were possible only because the train was stationary, or gradually pulling away, mattered less than the opportunity to connect Russian Railways with a usable patriotic past. Aleksandr Petrov’s animated film, also commissioned to mark Russian Railways’ 175th anniversary, visualized a demobilization echelon speeding through the landscape red flags fluttering on its locomotive.Footnote6 Yet, these were strange moments for a modernizing railway company to highlight. In the wake of war Soviet railways were in disarray. Much of the network lay in ruins, services were irregular, over-crowded, unsanitary, and petty crime made stations and service unsafe. Tickets were hard to obtain, although bribes and informal connections (blat’) helped (Fürst, Citation2010; Heinzen, Citation2016: 46–7).

The visual vocabularies of demobilization photography have been co-opted as part of the contemporary commemorative activity of the resurgent Putin-era cult of the Great Patriotic War. This demonstrates the enduring power of these photographs, but also their increasing decontextualization. On the northernly edge of central Samara’s Kuibyshev Square stands the Obelisk to Soldiers of the Great Victory (Stela Soldaty Velikoi Pobedy), unveiled on 1 May 1985. It comprises two pillars, displaying the Orders of Lenin awarded to Kuibyshev oblast’ in September 1958 and November 1970, and the text of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet’s order conferring these distinctions. Around these are arranged panels, which display large-format photographs and posters of veterans, victory parades, and wartime photographs. The panels are refreshed annually ahead of Victory Day celebrations on 9 May. In the summer of 2013, as illustrated in these panels displayed photographs of veterans paying their respects at Samara’s other war memorials. A central panel, however, featured a blown-up reproduction of Boris Utkin’s photograph of demobilized veterans arriving at Leningrad’s Baltic Station on 15 July 1945, emblazoned with the words, ‘9 May Victory Day’, the Order of Great Patriotic War and St. George Ribbon, ubiquitous symbols of post-Soviet war memory. This open-air exhibition placed Utkin’s photograph in the context of Victory Day rather than mass demobilization, and in a city over 1400 kilometres from where they were taken. Although Kuibyshev, as Samara was then called, organized its own modest receptions of returning veterans, local images had been displaced by the iconography of official national war memory. Furthermore, veterans’ reception in Kuibyshev frequently left much to be desired. A Party Control Commission report observed on 16 August 1946 that, ‘Party and soviet organizations recently ceased to meet demobilized soldiers with (groups of) workers. Of eight echelons arriving in Kuibyshev with the demobilized, a reception with the workers was organized for only one’ (RGANI, f.6, op.6, d.421, ll.87 − 9 [l.88]).

FIGURE 8 The Obelisk to the Great Victory, (Stela Soldaty Velikoi Pobedy), Samara, photographed by the author in July 2013.

A similar tendency to reframe the past can be observed in the vogue for re-enacting the return of demobilization echelons as part of Victory Day celebrations. In 2020, as part of celebrations to mark 75 years of Soviet victory, the ‘Train of Victory’ (Poezd Pobedy) museum project was launched, generously funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Russian Railways, and several media partners.Footnote7 The train’s exterior is covered in large reproductions of wartime photographs, including those taken of the echelon departing from Berlin and soldiers being reunited by family members at Moscow’s stations. The museum train is frequently pulled by restored steam locomotives, covered in flags, slogans, flowers, and greenery. This museum on rails owes a debt to civil-war agitation trains, although here the objective is patriotic education especially of children. ‘Poezd Pobedy’ has shuttled across Russia throughout 2020 and 2021, continuing to operate throughout the pandemic. At the time of writing, it had visited 42 Russian cities, including cities in Crimea, and was scheduled to visit Belarus between 11 and 28 June 2021.Footnote8 It consists of seven carriages, which contain state of the art multimedia exhibitions exploring the history of the Great Patriotic War, including 50 video projectors, 18 video walls, and 12 touch tables. An audio commentary guides the visitor through the exhibits via the wartime story of a young girl.

For citizens unable to visit the train, an impressive online 3D tour and impressive multi-media website bring the experience alive. The final exhibition carriage deals with the topic of victory and homecoming in line with the official messages of the Putin-era war cult. It includes the mannequin of a photo-correspondent photographing a group of veterans including men and women, soldiers and sailors, of different ranks and ethnicities. Behind the photographer video panels, placed as if they are windows, show re-enacted footage of soldiers gathered in wagons which reference Khaldei’s My iz Berlina photographs. These screens are used to create the impression of a slowly moving train. Further in the carriage video displays play the newsreel footage shot at Moscow’s stations in July 1945. A more contemplative space at the end of the exhibition considers the losses and costs of the war, in ways which sacralize victory.Footnote9 The webpage for the project includes descriptions of the displays in each carriage, that for the final carriage weaves one of Natalia Bode’s photographs taken in Berlin on 10 July, a photograph from the Rzhevskii station on 17 July, and the composition from the cover of Ogonek’s issue on 5 August 1945 into the web design. An embedded link takes the user to a minute long video with Rustam Sadretnikov, a curator from Moscow Railway Museum, discussing the arrival of the first demobilization echelons in Moscow as demobilization photographs appear on screen.

The financial and technical resources invested the poezd Pobedy and its considerable digital presence present demobilization as a universal experience, that looked the same regardless of when and where it happened. It reinforces as an official national memory of victory, ignoring the subtleties of local wartime experiences and memories. That this exhibition draws so deeply on the visual languages established in July 1945 is perhaps less surprisingly than the resilience of the official late Stalinist paradigm of joyous homecoming.

Conclusion

The celebrations that greeted returning veterans in July 1945, and their photographic representations, played an important part in shaping the Soviet Union’s narrative of a smooth and successful demobilization. The Soviet party-state deeply appreciated the power of visual symbols to communicate official ideological messages; at the level of symbolic politics Stalinism was remarkably successful (Figes & Kolonitskii, Citation1999; Gill, Citation2011). Demobilization photography communicated messages about the end of the war, glorious victory, the reconstruction of society, communities, families, and the reimposition of post-war gender relations. These were carefully constructed images, which established a visual vocabulary symbolizing demobilization as a process, even though most veterans never experienced anything resembling the homecoming depicted in these photographs. These iconic photographs became visual commonplaces, which function like stock images used to construct a shared sense of a community’s past. The dissemination, reproduction, and recycling of familiar images was not neutral, but rather social, cultural, political, and ideological processes (Hariman & Lucaites, Citation2007: 2). They were important agents in creating and re-ordering post-war Soviet society, which explains their long, rich, and varied afterlife. Photography, to (mis)quote Evgeny Dobrenko, was not simply, ‘some kind of illustration or appendix to political, social, or economic history (as culture is often viewed), but also as one of the most significant (and often the only) indicators of the dynamics of mass consciousness’ (Dobrenko, Citation2020: 20). It was through culture that Soviet ideology was often most effectively communicated. With the passing of time the ways in which the original photographs were framed, composed, and selected for publication has been forgotten, or co-opted in the interests of a resurgent nationalist narrative of Soviet victory. Contemporaries understood that much lay beyond the frame, but in the process of their reproduction they have been decontextualized. Regular repetition has obscured the complicated realities of homecoming. They have proved, ‘an ideal instrument for derealization of the war experience and its transformation into the history of victory. Before one’s eyes, experience began to be replaced with a prosthetic historicization’ (Dobrenko, Citation2020: 37). These powerful images had a strong emotional impact, then and now, which created an image of a post-war unity, recovery, and reconstruction. Demobilization was equated with victory and celebrated as a moment of national pride, even though it was experienced as a period of extended hardship as the Soviet Union was rebuilt. Nevertheless, these photographs communicated much about how society was to be reunited and rebuilt in the war’s wake.

Archives

GArkhADNO: Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv audiovizual’noi dokumentatsii Nizhegorodskoi oblasti (State Archive of Audio Vizual Documentation of Nizhnii Novgorod Oblast).

GAAO: Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Arkhangel’skoi oblasti.(State Archive of Arkhangelsk Oblast).

RGAKFD: Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv kinofotodokumentov (Russian State Archive of Documentary Films and Photographs).

RGANI: Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv noveishei istorii (Russian State Archive of Contemporary History).

TsDAVO: Tsentral’niï derzhavniï arkhiv vishchikh organiv vladi ta upravlinnia Ukraïni (Central State Archives of Supreme Bodies of Power and Government of Ukraine).

TsGAIPD-SPb: Tsentralnyi gosudarstvennyi arkhiv istoriko-politicheskikh dokumentov Sankt-Peterburga (Central State Archive of Historico-Political Documents St Petersburg).

TsGAKFFD-SPb: Tsentral'nyi gosudarstvennyi arkhiv kinofotofonodokumentov Sankt-Peterburga (Central State Archive of Documentary Films, Photographs, and Sound Recordings of St. Petersburg).

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this research were presented at the British Association of Slavonic and East European Studies Conference in 2014, and the Russian and East European Studies Centre Seminar at St. Anthony’s College, University of Oxford in May 2017. I am indebted to Jonathan Waterlow, Claire Knight, Tom Allbeson, and Claire Gorrara for detailed and constructive comments. Remaining errors and weaknesses remain my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robert Dale

Robert Dale is Lecturer in Russian History at Newcastle University. His research concentrates on the impact of the Second World War on the Soviet Union, with a particular focus on the reconstruction of the late Stalinist state and society, and the traumatic memories and experiences of combatants. His first monograph Demobilized Veterans in Late Stalinist Leningrad: Soldiers to Civilians was published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2015. Correspondence to: Robert Dale [email protected]; @DrRobDale

Notes

1 To access these photographs see www.sputnikimages.com and search for image numbers #1842, #5766158, #5766159, #5766160.

2 These images can be accessed via https://образывойны.рф/en/gallery/theme/pobeda/2337 (last accessed 4 February 2022), and https://www.belarus.by/en/press-center/photo/i_15607.html?page=2 (last accessed 4 February 2022).

3 This image can be found online on the website of the Borodulin Collection https://www.borodulincollection.com/war/english/children_images/13.htm (last accessed 4 February 2022).

4 For examples in published works see (Merridale, Citation2005: 310–11), the photographic inserts in (Zubkova, Citation2000) and the cover of (Anon, Citation2015). For examples in photographic albums see (Gluskh, Citation2005: 100–1) and (Koloskova, Citation2009: 346–7).

5 The promotion film ‘175 of Russian Railways’ was released in 2012 and can be accessed via Russian Railways’ YouTube channel https://youtu.be/h-0RT9lRnVE (last accessed 4 February 2022).

6 Aleksandr Petrov animation, an advertisement for Russian Railways released in 2012, can be watched at https://vimeo.com/54777823 (last accessed 4 February 2022).

7 For an official report on the project see ‘Unikal’nyi muzei-panorma “Poezd Pobedy” ob’edet 50 gorodov Rossii,’ RIA Novosti Website 9 November 2020 https://ria.ru/20201109/poezd-1582095697.html (last accessed 4 February 2022). The project has an impressive multimedia website; ‘Poezd Pobedy’ https://поездпобеды.рф/ (last accessed 4 February 2022).

8 A current timetable for the scheduled movements of the museum can be found at https://поездпобеды.рф/raspisanie/ (last accessed 4 February 2022).

9 A twenty-minute virtual tour of the exhibitions is available at: https://поездпобеды.рф/3d-tur/ (last accessed 4 February 2022).

References

- Anon. 1945a. Zakon o demobilizatsii starshikh vozrastov lichnogo sostava Deistvuiushchei Armii. Krasnaia zvezda, 24 June, 1.

- Anon. 1945b. Torzhestvennaia vstrecha demobilizovannykh voinov v Leningrade. Krasnaia zvezda, 13 July, 3.

- Anon. 1945c. Vstrechaem dorogykh voinov. Smena, 16 July, 2.

- Anon. 1945d. Stolitsa vstrechaet voinov-pobeditelei. Vecherniaia Moskva, 17 July, 1.

- Anon. 1945e. V Moskvy! Vchernaia Moskva, 17 July, 2.

- Anon. 1945f. Stolitsa vstrechaet voinov-pobeditelei. Vechera na Rzhevskom voksale. Trud, 18 July, 1.

- Anon. 1945g. Moskva vstrezhaet demobilizovannykh voinov-pobediteli, Vecherniaia Moskva, 18 July, 1.

- Anon. 1945h. Vecherniaia Moskva, 19 July 1945, 3.

- Anon. 1945i. Cover. Ogonek, 31 (950), 5 August 1945.

- Anon. 1945j. O demobilizatsii vtoroi ocheredi lichnogo sostava Krasnoi Armii. Trud, 26 September, 1.

- Anon. 1945k. Ukaz Presidiuma Verkhovo Soveta SSSR – O demobilizatsii vtoroi ocheredi lichnogo sostava Krasnoi Armii. Krasnaia zvezda, 26 September, 1.

- Anon. 1945l. Ot ratnogo truda k mirnomy stroitel’stvy. Ogonek, 41 (960), 14 October, 1.

- Anon. 1945m. Dobro pozhalovat’ v rodnoi gorod! Leningradskaia pravda, 28 October, 3.

- Anon. 2000. Moskva vstrechaet pobeditelei. Iz stenogrammy soveshchaniia sekretarei raionnykh komitetov partii i Ispolkomov Sovetov. Iiul’ 1945g. Otechestvennye arkhivy, 3:44–52.

- Anon. 2010. Russian History after the ‘Visual Turn’. Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 11(2):217–220.

- Anon. 2015. Sovetskoe gosudarstvo i obshchestvo v period pozdnego stalinizma 1945–1953 gg. Materialy VII Mezdunarodnoi nauchnoi konferentsii Tver’ 4-6 dekabria 2014. Moscow: ROSSPEN.

- Anon. 2017. Critical Forum: The Afterlife of Photographs. Slavic Review, 7(1):52–97.

- Antonov, A.I. 1945. Doklad Nachal’nika General’nogo Shtaba Krasnoi Armii generala armii A. I. Antonova o demobilizatsii starshikh vozrastov lichnogo sostava Deistvuiushchei Armii, Krasnaia zvezda, 23 June, 2.

- Berkhoff, K.C. 2012. Motherland in Danger: Soviet Propaganda During World War II. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bidlack, R. & Lomagin, N. 2012. The Leningrad Blockade, 1941–1944: A New Documentary History from the Soviet Archives. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Blank, M. 2018. Ol’ga Lander – fotograf frontovoi gazety ‘Sovetskii voin. In: Olga Lander: Sowjetische Kriegsfotografin im Zmeiten Weltkrieg. Berlin: Mitteldeutscher Verlag, pp. 11–28.

- Brandenberger, D. 2011. Propaganda State in Crisis: Soviet Ideology, Indoctrination, and Terror under Stalin, 1927 - 1941. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Burke, P. 2001. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Burke, P. 2008. Interrogating the Eyewitness. Cultural and Social History, 7(4):435–44.

- Dale, R. 2010. Rats and Resentment: The Demobilization of the Red Army in Post-War Leningrad (1945-1950). Journal of Contemporary History, 45(1):113–33.

- Dale, R. 2015. Demobilized Veterans in Late Stalinist Leningrad: Soldiers to Civilians. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Dobrenko, E. 2020. Late Stalinism: The Aesthetics of Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Edele, M. 2008. Soviet Veterans of the Second World War: A Popular Movement in an Authoritarian Society, 1941–1991. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Edele, M. & Slaveski, F. 2016. Violence from Below: Explaining Crimes against Civilians across Soviet Space, 1943 -1947. Europe-Asia Studies, 68(6):1020–35.

- Evans, J. 2018. Introduction: Photography as an Ethics of Seeing. In: J Evans, P. Betts & S-L Hoffman, eds. The Ethics of Seeing: Photography and Twentieth-Century German History. New York, Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 1–22.

- Figes, O. & Kolonitskii, B. 1999. Interpreting the Russian Revolution: The Language and Symbols of 1917. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Fürst, J. 2010. Uporiadochennyi khaoc i khoatichnyi poriadok: Mir sovetskikh zheleznykh dorog posle voiny. In: B. Fiseler & N. Muan, eds. Pobediteli i pobezhdennye: Ot voiny k miry: SSSR, Frantsiia, Velikobritaniia, Germannia, SSha (1941–1950). Moscow: ROSSPEN, pp. 271–83.

- Gill, G. 2011. Symbols and Legitimacy in Soviet Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Glushk, N.N., et al. 2005. Velikaia pobeda i vozrozhdenie Moskvy. Moscow: Kontakt-Kultura.

- Gorinov, M.M., Ponomarev, A.N. & Taranov, E.V. eds. 2000. Moskva poslevoennaia, 1945-1947 arkhivnye dokumenty i materialy. Moscow: Mosgorarkhiv.

- Hariman, R. & Lucaites, J.L. 2007. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Heftberger, A. 2015. Propaganda in Motion. Dziga Vertov's, Aleksandr Medvedkin's, Film Trains and Agit Steamers of the 1920s and 1930s. Apparatus. Film Media and Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe, 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2015.0001.2

- Heinzen, J. 2016. The Art of the Bribe: Corruption Under Stalin, 1943 -53. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hicks, J. 2020. Victory Banner Over the Reichstag: Film, Document, and Ritual in Russia’s Contested Memory of World War II. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Kalatozov, M. 1957. Letyat zhuravli (The Cranes are Flying). Directed by Mikhail Kalatozov. Mosfilm.

- Kapustianskii, A. 1945. Photograph. Krasnaia zvezda, 22 July, 3.

- Kapustianskii, A. & Khomzor, G. 1945. Photograph. Krasnaia zvezda, 19 July, 3.

- Kenez, P. 1985. The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917–1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Khaldei, E. 1945. Photographs. Vecherniaia Moskva, 12 July, 1.

- King, D. 1997. The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in the Soviet Union. Edinburgh: Canongate.

- Koloskova, E., et al. 2009. V ob’ektive voina 1941-1945: War Through the Camera Lens. St. Petersburg: Liki Rossii.

- Krylova, A. 2010. Soviet Women in Combat: A History of Violence on the Eastern Front. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Markwick, R.D. & Cardona, E.C. 2012. Soviet Women on the Frontline in the Second World War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McCallum, C.E. 2015a. The Return: Postwar Masculinity and the Domestic Space in Stalinist Visual Culture, 1945-53. Russian Review, 74(1):117–143.

- McCallum, C.E. 2015b. Scorched by the Fire of War: Masculinity, War Wounds and Disability in Soviet Visual Culture, 1941-65. The Slavonic and East European Review, 93(2):251–285.

- McCallum, C.E. 2018. The Fate of the New Man: Representing & Reconstructing Masculinity in Soviet Visual Culture, 1945-1965. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Merridale, C. 2005. Ivan’s War: The Red Army 1939–45. London: Faber & Faber.

- Morris, E. 2011. Believing is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography). New York: Penguin.

- Nakachi, M. 2006. N. S. Khrushchev and the 1944 Soviet Family Law: Politics, Reproduction and Language. East European Politics and Societies, 20(1):40–68.

- Nakachi, M. 2021. Replacing the Dead: The Politics of Reproduction in the Postwar Soviet Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Olekhnovich, M. 1945. Na balkone demobilivovannogo punkta. Vecherniaia Moskva, July 1945, 1.

- Peri, A. 2017. The War Within: Diaries from the Siege of Leningrad. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Plamper, J. 2012. The Stalin Cult: A Study in the Alchemy of Power. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Popova, A.A. & Kollts, N. 1945. Ofitser artillerii. Ogonek, 46-47, 30 November, 14-16.

- Prorokova, B. 1947. Universal’nyi plakat. Krokodil, 13, 10 May, 10.

- Reid, A. 2011. Leningrad: Tragedy of a City Under Siege, 1941–44. London: Bloomsbury.

- Repina, B. & Rusakova, L. 1945. ‘Snova doma!’ Ogonek, 31, 5 August, 8-9.

- Rolfe, M. 2006. Soviet Mass Festivals, 1917 -1991, trans. by Cynthia Klohr. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press.

- Schechter, B.M. 2019. The Stuff of Soldiers: A History of the Red Army in World War II Through Objects. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Shenk, F.B. 2016. Poezd v sovremennost’: Mobil’nost’ i sotsialnoe prostranstvo Rossii v vek zheleznykh dorog. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

- Shneer, D. 2010. Picturing Grief: Soviet Holocaust Photography at the Intersection of History and Memory. The American Historical Review, 115(1):28–52.

- Shneer, D. 2012. Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War and the Holocaust. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Shneer, D. 2020. Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Slaveski, F. 2013. The Soviet Occupation of Germany: Hunger, Mass Violence, and the Struggle for Peace, 1945 -1947. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smirmov, A. 1971. Belorusski vokzal (Belorussian Station). Directed by Andrei Smirnov. Mosfilm.

- Sontag, S. 2008. On Photography. London: Penguin Classics.

- Tagg, J. 1988. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Taylor, R. 1971. A Medium for the Masses: Agitation in the Soviet Civil War. Soviet Studies, 22(4):562–574.

- Tsiurupa, V. 1945a. Moskva vsetrechaset svoikh geroev. Krasnaia zvezda, 18 July, 3.

- Tsiurupa, V. 1945b. Domoi s pobedoi. Krasnaia zvezda, 22 July, 3.

- Utkin, B. 1945. Photograph. Krasnaia zvezda, 15 July, 3.

- Waterlow, J. 2018. It’s Only a Joke Comrade! Humour, Trust and Everyday Life Under Stalin. Oxford: CreateSpace.

- Werneke, J. 2019. ‘Nobody understands what is beautiful and what is not’: Governing Soviet Amateur Photography, Photography Clubs and the Journal Sovetskoe Foto. Photography and Culture, 12(1):47–68.

- Woll, J. 2000. Real Images: Soviet Cinema and the Thaw. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Youngblood, D.J. 2007. Russian War Films: On the Cinema Front 1914 -2005. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- Zotov, M. & Borisov, B. 1945. Schastlivogo puti! Provody demobilizovannykh is strelkogo polka. Krasnaia zvezda, 10 July, 3.

- Zubkova, E. 2000. Poslevoennoe sovetskoe obshchestvo: politika i povsednevnost’ 1945–1953. Moscow: ROSSPEN.