Abstract

Studies of memory in relation to the Falklands/Malvinas War have typically focused on interrogating narratives, practices and performances associated with its memory within different national contexts (predominantly Argentina, the Falkland Islands and the UK). Far less attention, however, has been placed on how memory of the war is summoned on the international stage, in diplomatic settings like the United Nations (UN). This paper analyses specific diplomatic materials and performances produced by the governments of the Falkland Islands and Argentina on and after the 30th anniversary of the war (2012-15), paying particular attention to how they reference the 1982 war. The paper argues that these performances and materials of diplomacy are revealing of the (re)production of geopolitical relations and strategies, as well as how memories of the past can be consciously foregrounded/backgrounded in an attempt to achieve strategic and diplomatic objectives.

Introduction

There is now a well-established body of work that has examined memory of the Falklands/Malvinas War over the preceding 40 years. This research has looked at the different scales through which memory is (re)produced and negotiated, ranging from state-produced narratives and commemoration (e.g. Basham, Citation2015; Guber, Citation2001; Lorenz, Citation2020; Mira and Pedrosa, Citation2021), media representations of the war coinciding with key anniversaries (e.g. Bellot, Citation2018; Maltby, Citation2016), artistic interventions on stage and screen (e.g. Blejmar, Citation2017; Maguire, Citation2019; McAllister, Citation2020), as well as citizens’ everyday engagements with memories of the 1982 war within institutional and domestic settings (e.g. Benwell et al., Citation2020; Benwell, Citation2016a; Parr Citation2018). These studies have typically focused on interrogating narratives, practices and performances associated with memory of the war within different national contexts (predominantly Argentina, the Falkland Islands and the UK). While international diplomacy associated with the Falklands/Malvinas sovereignty dispute has received considerable academic attention over the years (see, for example, Benwell, Citation2016b; Dodds, Citation2002; Dodds and Manovil, Citation2001; González, Citation2013; Pinkerton and Benwell, Citation2014), far less work has interrogated how memory of the Falklands/Malvinas War is summoned on the international stage, in diplomatic settings like the United Nations (UN). These diplomatic performances can reveal a great deal about the (re)production of geopolitical relations and strategic priorities, as well as how memories of the past can be consciously foregrounded/backgrounded in an attempt to achieve (inter)national objectives (Bachleitner, Citation2019). They also bring to the fore interesting tensions concerning the presentation and performance of memory of the Falklands/Malvinas War for national and international audiences. These are not always easy for states to reconcile given the affective atmospheres of nationalism associated with memory of war and its commemoration on the one hand (Closs Stephens, Citation2016; Sumartojo, Citation2021), and the strategic narratives that they wish to project, on the other. There are, of course, significant complexities inherent to doing this, not least because the 1982 war and its memory need careful framing in the present by national governments, most especially when undertaking diplomacy. So, for instance, Argentina has had to grapple with the problematic of dealing with the historical baggage connected to invasion of the Falkland Islands (or what Argentina would see as the ‘recuperation’ of the Islas Malvinas) by a military dictatorship that ruled the country from 1976-83, whilst also presenting itself as the ‘peaceful’ interlocutor wronged by continued British imperial aggression and intransigence in relation to the sovereignty dispute in the South West Atlantic.Footnote1 For the Falkland Islands Government (FIG), there is an ongoing tension connected to its presentation of a strategic narrative about a self-determining and self-sufficient country free from the vestiges of British colonialism (Argentine politicians and diplomats regularly label the Falkland Islands as a colonial enclave), whilst sufficiently acknowledging and commemorating the ‘sacrifice’ of British Armed Forces during the 1982 war (see Mercau, Citation2019). We argue that these kinds of tensions between memory of the past and their negotiation in the present can be productively examined through contemporary geopolitical relations and, more specifically, the ways both Argentina and the Falkland Islands do diplomacy on the international stage.

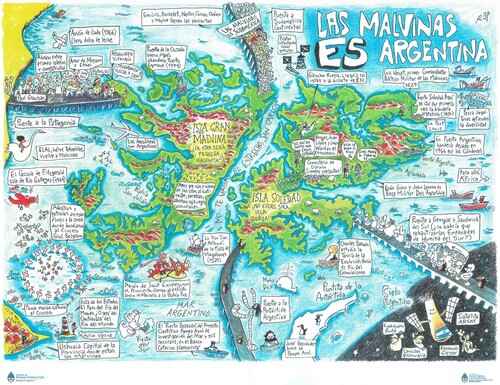

To make this argument, we turn to two examples of diplomatic material produced by the governments of Argentina and the Falkland Islands,Footnote2 considering them alongside their broader diplomatic assemblages (see Dittmer, Citation2017; McConnell and Dittmer, Citation2018), to highlight how they summon the spatial and temporal in diverse ways to align with their respective sovereignty claims and strategic priorities. The first, co-produced in 2015 with the input of Argentine politicians and diplomats, drawn by the well-known Argentine illustrator Miguel Repiso (commonly known as Rep, the moniker he uses to sign his illustrations), was a large foldout map entitled ‘Las Malvinas Es Argentina’ (see ). The map was launched at a side event of the 2015 meeting of the Special Committee on Decolonisation (or C-24) hosted by the Argentine government, which also featured a speech reiterating Argentina’s sovereignty claim and call for dialogue with the UK from its then foreign minister, the late Héctor Timerman, and a short performance from the famous Argentine musician Gustavo Santaolalla.Footnote3 At the same time as invited diplomats, journalists and dignitaries listened to the music, at the back of the stage, Rep drew a large silhouette of the Islas Malvinas surrounded by numerous yellow peace symbols, red hearts and the same slogan included on the map that was taken away by those in attendance. The map came to our attention as academics when copies were delivered to us at our respective universities by officials working at the Argentine embassy in London, highlighting ‘the capacity for [diplomatic] objects to move across and be affective in different material domains’ (Rech, Citation2020: 1086). In Dr Pinkerton ‘s case, the delivery of the map was made by hand during a meeting with two Argentine diplomats in his office at Royal Holloway, University of London in October 2015 – a meeting which had been requested by the Argentine embassy and which came in the aftermath of Dr Pinkerton’s involvement in the 2013 Falkland Islands referendum as an ‘academic observer’. Both Benwell and Pinkerton are scholars of South Atlantic and Latin American geopolitics and had, evidently, been identified as potentially fruitful contacts when Argentine public diplomacy was intensified during Alicia Castro’s tenure as Argentina’s Ambassador to the UK (2012-16). We reflect more on the spatiotemporal relations of these diplomatic performances and their materialities (as well as their mobilities), in relation to memory of the 1982 war in our analysis below.

The second example is a 22-page booklet – Our Islands, Our Home – produced by the Falkland Islands Government (FIG) to mark the 30th anniversary year of the Falklands War in 2012 and dedicated to ‘the men and women of Her Majesty’s Armed Forces and support personnel who liberated the Falkland Islands from Argentine occupation in 1982’ (see ). Rather than profile the lives of British soldiers, sailors and airmen who fought and, in the case of 255 servicemen and three Falkland Islanders, died in the 1982 conflict, this booklet profiles a generation of Falkland Islanders whose lives have been materially transformed since the 74-day conflict in 1982. As the opening dedication continues, ‘The success of today’s Falkland Islands is the legacy of your sacrifice.’ Our Islands, Our Home was and remains available as a digital download via the FIG website and was distributed as a printed booklet from the FIG Office in London. It was also widely circulated to MPs and members of the House of Lords (an important audience for Falkland Islands’ diplomatic labour) during the 30th anniversary year, while its status as an important piece of diplomatic material was confirmed as it travelled with the Falkland Islands' contingent when they addressed the C-24 Decolonisation Committee of the United Nations in New York in June 2012. These two examples of diplomatic material – the map and the booklet – both reveal and accord with the strategic priorities of Argentina and the Falkland Islands in their respective approaches to the sovereignty dispute. The FIG booklet foregrounds the temporalities of their sovereignty claim, emphasizing the longevity of Falkland Islanders’ settlement, themes of intergenerationality and ‘stewardship’, and presents individual biographies that make reference to extended familial lineages. In contrast, Argentina’s use of the map foregrounds the spatial and territorial, centring the culturally-familiar shape of the islands (and their geographical proximity to the Latin American continent) by utilizing them as a tabula rasa for inscribing multiple stories of local, regional, cultural, historical and environmental interconnections that operate across a range of temporal registers.

We draw on these two examples to make key contributions to debates about memory and diplomacy. Firstly, we seek to consider memory of war and its commemoration beyond national contexts in ways that have not previously been considered in relation to the Falklands/Malvinas War. What happens when the ‘affective and sensory intensities and symbolic resonances’ (Sumartojo, Citation2021: 541) of war commemoration remain, but the message needs to be altered for international audiences or to reflect/take advantage of shifting geopolitical imperatives? How do states negotiate memory of past conflict, and how is this reflected through the diplomatic materials and performances that emanate from settings like the UN (and further afield via the online and offline circulation of diplomatic objects)? Secondly, recent work on the geographies of diplomacy has considered the calculative use of emotion by diplomats, supported by a range of diplomatic materialities to ‘buttress geopolitical claim-making’ (Jones, Citation2020: 655). Similarly, we think through the deliberative deployment of emotion through the map and the booklet, paying close attention to the sites, events, relations and bodies that are foregrounded to remember the 1982 war, as well as those that are absent or (un)consciously backgrounded in diplomatic spaces and their related materialities. We question how the memory of war can influence and unsettle diplomatic practices and geopolitical claim-making in ways that have yet to be substantially considered in the context of the South West Atlantic.

On this 40th anniversary of the Falklands/Malvinas War, then, we choose, rather counter-intuitively, to look back at events and diplomatic materials produced closer to the 30th anniversary. We do this because enough time has now elapsed to enable critical reflection on these events and, we argue, they continue to hold relevance for understanding contemporary and future geopolitical and diplomatic relations regarding the Falklands/Malvinas sovereignty dispute. The paper proceeds with a review of literature that explores memory as part of diplomatic practices and materials, before moving on to discuss the two examples from the governments of the Falkland Islands and Argentina respectively.

Managing memory through diplomatic practice and material

Remembering is intensely political: part of the fight for political change is a struggle for memory. (Edkins, Citation2003: 54)

The burgeoning scholarship interrogating memory has repeatedly underlined how the past can be harnessed for political purposes in the present (see Boyarin, Citation1994; Mitchell, Citation2003). Memories of war and conflict are often central to (re)producing and sustaining national belonging and ‘influence post-war and post-conflict (re)articulations of identities, especially national identities’ (Drozdzewski et al., Citation2016: 447; Till, Citation2003). These are very often selective and self-serving, directed towards national audiences particularly on key anniversaries, in ways that attempt to ‘“fix” the meaning of the practices of violence conjured into memory’ (Basham, Citation2015: 77). This is not to suggest that narratives of national memory are forever static given that, ‘[w]hat is being remembered of the past is largely dependent on the cultural frames, moral sensibilities and demands of the ever-changing present’ (Assmann, Citation2010: 21; Mitchell, Citation2003). Memories, then, as Assmann (Citation2010) makes clear, are dynamic and subject to political struggle over time relating to what, when, where and how historical events are remembered.

However, as Edkins cogently asserts, ‘[s]ome forms of remembering can be seen as ways of forgetting’ (Edkins, Citation2003: 16). Scholarship has duly followed these themes of forgetting, silencing and absencing, tracing the embodied and emotional practices bound up with these processes (see Raj, Citation2000; Trouillot, Citation1995). Muzaini (Citation2015: 102), in calling for greater analysis of the ‘exercise’ of forgetting (relative to remembering), emphasizes the ‘active embodied, material and spatial practices of producing absences’. There is a sense here that absencing or the process of ‘wanting to forget’ can be deliberative and strategic on the one hand, and yet, this work also illustrates how these attempted erasures can be foiled by the material environment and other bodies with affective capacities (also see Kuusisto-Arponen, Citation2014). In this paper, we remain acutely conscious of the (geo)political decisions that are made regarding the performance and presentation of memory linked to the Falklands/Malvinas War. This sensitivity to the act of remembering and forgetting in the existing literature is a useful starting point to think through how governments (and those acting on their behalf) make choices about what to include and exclude in diplomatic materialities and performances connected to geopolitical claim-making (Jones, Citation2020). There was, we argue, a careful framing of memory of the 1982 war evidenced through diplomatic objects and the broader strategic narratives of Argentina and the Falkland Islands, in relation to their sovereignty claims, during the 30th anniversary and in the following years. While the war was certainly not forgotten, references to it on international and diplomatic stages were managed in line with the broader strategic narratives presented by Argentina and the Falkland Islands.

The instrumental use of memory for foreign policy purposes has received scant attention from scholars of International Relations, relative to literature emphasizing its significance in reproductions of the nation (Bachleitner, Citation2019; Clarke and Duber Citation2020; Eckersley, Citation2015). Indeed, as Clarke and Duber (Citation2020: 51) assert, the ‘focus on the national politics of memory, while offering an account of important developments, tends to obscure the potential of memory and heritage policy as an aspect of foreign policy-making, particularly in terms of national projection’. This lacuna applies to foreign policy and diplomacy in the wake of the Falklands/Malvinas War and the examples we present below illustrate how ‘memory is also the strategy with which states actively pursue international goals’ (Bachleitner, Citation2019: 494). These projections of the nation can be the subject of controversy and contestation depending on whether states choose to portray themselves as the innocent victim or the guilty perpetrator in the remembrance of historical geopolitical events (ibid). So, for instance, the map of the Falklands/Malvinas that we analyse below chooses to remember sites, events and moments of the 1982 war in particular kinds of ways that emphasize Argentina’s victimization at the hands of British military aggression, whilst eliding the initial violence of invasion perpetrated by the Argentine military dictatorship.

Bachleitner’s (Citation2019) study examining diplomacy with memory tends to rely on traditional conceptualisations of ‘foreign policy actors’ (i.e. diplomats and ministers in elite places like ministries and embassies) and diplomatic texts such as speeches and documents. In recent years, scholars of IR and political geography have embraced the increasingly diverse set of practices, actors and objects that are deployed in the doing of diplomacy (McConnell, Citation2019). The creative diplomatic interventions that emerge from the enrolment of non-state actors (e.g. artists, citizens) who produce and perform diplomacy in alternative ways (often alongside state diplomats) has ‘an affective capability to move an audience (albeit in different ways) and play on a range of sentiments and emotions’ (Pinkerton and Benwell, Citation2014: 17). We continue to be interested in what this ‘outsourcing’ does to diplomatic practice and the making of geopolitical claims, focusing more specifically on the choices that are made in relation to the performance and (re)production of memory of the 1982 war. This emerging body of work on diplomacy, then, has foregrounded the ‘performative and affective registers of diplomatic spaces’ (McConnell, Citation2019: 54) in ways that can help us examine how stories are strategically told by states about geopolitical pasts, presents and futures. It also considers what Jones (Citation2020: 650) has referred to as ‘the calculative use of emotions in diplomacy’, as well as the ‘reflexive, communicative, and even tactical use of emotion to advance claim making’ (Jones and Clark, Citation2019: 1263).

These tactics can extend to the diplomatic materialities or ‘props’ deployed to support claims and instil emotional responses in a range of diverse audiences to reinforce strategic narratives (e.g. Dittmer, Citation2017; Jones, Citation2020). These objects, while not always explicitly diplomatic in the traditional sense, are, we argue, integral parts of geopolitical claim-making, an observation reflective of political geographers’ broader interest in the ways ‘objects enable, disable, and transform state power, beyond just reflecting it’ (Meehan et al., Citation2013: 2; Depledge, Citation2015; Müller, Citation2017; Rech, Citation2020; Sharp, Citation2020; Thrift, Citation2000). Importantly, these diplomatic materials are not confined to traditional spaces of diplomacy (i.e. the halls and conference rooms of the UN) and instead ‘spill over’ into other domains, underlining their potential as lively geopolitical objects that can reach multiple constituencies (see Rech, Citation2020; Lin, Citation2021). The different actors, objects, sites and modes of diplomatic expression that we examine below are calculative in that they attempt to harness and put to work, memories and emotions bound up with painful geopolitical pasts. In these examples, memories are ‘packaged’ for an international, diplomatic audience/stage in ways that appeal to universalized international emotions and values, avoiding parochial, militaristic or nationalistic registers that have been more commonly documented in the commemoration of war. We attempt, therefore, to interrogate the ‘dynamics of (in)visibility and (in)audibility’ (McConnell, Citation2019: 54) that are manifest in/through the diplomatic practices and materialities of Argentina and the Falkland Islands with respect to memory of the Falklands/Malvinas War.

Such (re)productions of memory must be carefully pitched given their potential to offend national constituencies and/or ‘damage the legitimacy of geopolitical claim-making and the diplomatic reputations that are tied to it’ (Jones, Citation2020: 651). These diplomatic interventions, then, cannot simply replicate how war gets commemorated within national contexts, given their need to appeal to broader international audiences in ways that can push certain narratives consistent with geopolitical and strategic claim making. However, they cannot completely overlook past wars given the emotions bound up with their commemoration, and their significance in the (re)production of national stories. Diplomatic practices and materialities, in similar ways to commemoration conceived for national citizenries, need to be sensitively ‘engineered’ in the interests of achieving particular (geo)political objectives (Thrift, 2004, cited in Sumartojo, Citation2021: 535). So, for example, the booklet produced by the FIG that we examine below commemorates the war by drawing on certain temporalities that summon notions of futurity through the bodies and accounts of different generations of Falkland islanders. As Sumartojo (Citation2021: 532) contends: ‘The question of futurity is a crucial one for nations in ongoing processes of reproduction, but also holds out the possibility of change to, or intervention in, those futures.’ Rather than drawing on militaristic registers of commemoration that foreground the actors and events of 1982, the booklet frames the war through the intimate memories and accounts of civilian islanders in ways that emphasize its legacies for present and future generations. Several scholars writing about affect and nationalism (occasionally within the context of war commemoration, see Sumartojo, Citation2020), have referred to the notion of foregrounding and backgrounding to account for the ways in which ‘[n]ationalisms are felt as more or less intense affective presences’ in people’s everyday lives (Wilson and Anderson, Citation2020: 592; Merriman and Jones, Citation2017; Merriman, Citation2020). This idea has been useful to help us think about how memory of the Falklands/Malvinas War is evoked through diplomatic practices that, in more instrumental ways, background/foreground different actors, objects, stories, temporalities and spatialities to reinforce strategic narratives.

Our Islands Our Home

On first inspection Our Islands, Our Home appears to be the kind of unremarkable booklet that one would reasonably expect to find in the reception area of any national tourist office or diplomatic mission around the world – a piece of textual and visual ephemera provided to give a brief insight into a place and people soon to be visited, or simply provided as a distraction for guests while waiting for their hosts to collect them. Its 6-inch square format and colourful cover is suggestive of a marketing tool rather than a more substantive or meaningful piece of diplomatic or commemorative material. However, Our Islands, Our Home is no straightforward glossy travel guide. The dedication to H.M. Armed Forces in the opening pages connects themes of war, liberation and bodily sacrifice with the present and future peace and prosperity of the modern Falkland Islands. The dedication is written for and on behalf of ‘the people of the Falkland Islands’ and, ultimately, it is the lives and livelihoods of the people of the Falklands (with their distinct senses of identity, heritage and connection to their Island ‘home’) who are, here, positioned as the survivors of war and the agents and objects of commemoration.

Our Islands, Our Home (OIOH) profiles thirteen Islanders – men and women representative of a generation of Falkland Islanders whose lives have been substantially lived in the aftermath of conflict and who, explicitly and implicitly, acknowledge the 1982 war and the subsequent peace as transformational. The booklet foregrounds insights into the islands’ recent industrial development, new waves of commercial enterprise and entrepreneurialism, custodianship over the natural environment, lives spent in public and government service, as well as the hopes and aspirations of (and for) future generations of Falkland Islanders. Nyree Heatham, who is described as combining ‘her role as a mother to Kai with running a family tourism business’, draws the past and present of the Falklands into an intimate and multigenerational relationship (OIOH, Citation2012: 2). We learn about the ‘freedom’ of Nyree’s own childhood spent on her parents’ farm and the unique preparation that provided for her entry into the tourism industry, as well as more formal educational opportunities that have previously taken her from Stanley to the UK and Australia. ‘Living in the Falkland Islands means that our children benefit from the freedom and safety, education and opportunities that life here has to offer,’ Nyree concludes, ‘none of which would be possible without the sacrifices made by the British forces in 1982’ (OIOH, Citation2012: 2). Ben Cockwell, an artist and designer from West Falkland, makes a similar temporal association. ‘It all comes back to 1982’, he observes. ‘Whatever people of our generation have made of our lives in the Falklands is only possible thanks to the action taken by the British Government of the time and to the efforts and sacrifices made by the British forces that fought for our freedom. I for one will always remember that and be grateful for it’ (OIOH, Citation2012: 10). Through these and other testimonies, the restoration of military security in 1982 is credited with the subsequent production of a wider set of economic, political, societal and environmental securities that have walked the Falklands back from the brink of economic stagnation and depopulation in the late-1970s and delivered a more self-sustaining present and a more hopeful future for Falkland Islanders.Footnote4 Ros Cheek, one of the Falklands’ top legal professionals, draws these senses of security together in direct relation to her own life and mobilities (see ). Similar to Heathman, Cheek considers her educational opportunities to have been ‘a direct benefit of the economic stability provided by the British presence in the Islands following the war’, which, in turn, enabled her to ‘come back’ to the Islands after a period of training and further education overseas. Cheek’s testimony, here, is revealing of a particularly lively awareness of personal and collective ‘ontological security’ within the Falkland Islands, the origins of which are often traced to 1982, although they are narrated in diverse ways across different generations (see Benwell, Citation2019). Drawing on the sociological work of Giddens (Citation1991) and, prior to that, the psychoanalytical insights of Laing (Citation1960), ontological security encapsulates the mental and emotional stability afforded to a person/community from their sense of confidence in the continuity of events in one's own life. In the case of the Falkland Islands, the key markers of ontological security exist in a close relationship with issues of identity and memories of war as a turning point in the Falkland Islands’ story:

‘a clear benefit that the war gave to my generation of Falkland Islanders is a sense of certainty that we are very fortunate to be able to call this place home. That has given us a drive, purpose, and pride in our country, and has enabled us to make progress that we couldn’t have dreamed might be possible in the context of the political uncertainty and economic stagnation that was the background to our childhood before the war’ (OIOH, Citation2012: 11).

In a pattern that is repeated across all thirteen profiles, the achievements and hopes of this (and future) generation(s) of Falkland Islanders are juxtaposed alongside brief accounts of a family member from the previous generation, each with direct living memory or experience of the war. In Daniel Fowler’s case, it is his father, John, the Falklands’ Superintendent of Education in 1982, whose house was accidentally shelled by British troops during the recapture of Stanley, killing three civilians. Nyree Heathman’s mother, Aisla, had been ‘instrumental in assisting the British troops’ as they pushed towards Stanley (OIOH, Citation2012: 21); James Wallace’s father, Stuart, had been a member of the Falkland Islands Defence Force in 1982 and was expelled from Stanley by the Argentine forces for being a perceived ‘troublemaker’ (OIOH, Citation2012: 17); while Stephen Luxton’s father, Bill, his mother Patricia and a young Stephen were all deported to the UK following the invasion, where Bill gave interviews to the British media about the family’s brief experience of life under the Argentine military occupation. These brief historical interjections are illustrated with black and white photographs in contrast to the much longer profiles and colour photographs (see ) afforded the younger generation – design elements that, according to Royle (Citation2013: 41), serve to reinforce the core ‘message’ of Our Islands, Our Home: that ‘the past is not forgotten […] but things have moved on’. They also serve to illustrate the agency of Falkland Islanders in the events of 1982, resisting and subverting the Argentine invasion and occupation, and, in so doing, reinforcing the contemporary geopolitical narrative (propagated by the UK and Falkland Islands Governments) that it is the Falkland Islanders who are in possession of the agency and the right to self-govern and self-determine their own futures (Bound, Citation2006).

Our Islands, Our Home serves, then, as an important piece of commemorative literature marking the 30th anniversary of the Falklands War, placing the wartime contributions and post-war achievements of the Falkland Islands' community as the commemorative centre piece. However, we are also sensitive to the dual role of Our Islands, Our Home as the stuff of ‘sovereignty labour’ (Benwell, Citation2014). The curation of bodies, sites, and events within the publication, and the foregrounding and backgrounding of particular narratives and framings, are strategic and bound up in the representational logics of diplomacy and geopolitical claim making. Drawing on the experience of Bosnia, David (Citation2019) draws out the links between memory, security and identity in post-conflict societies. Where ‘collective memory provides groups with a sense of Self (that is, with ontological security)’, David (Citation2019: 214) observes, there may exist a corresponding impulse to ‘protect’ or ‘securitize’ those memories to prevent them from ‘fading into oblivion’. Memories, therefore, can be subject to a series of formal/informal, external/internal, legal, judicial and political ‘securitizations’ through, for example, ‘memory laws’ or other processes of memory standardisation/regulation. In the context of the Falkland Islands, while there are no ‘memory laws’ on the statute book, publications such as Our Islands, Our Home and formal submissions/speeches to the UN Decolonisation Committee represent material and performative examples of how memories of war are strategically curated, standardized, ‘fixed’ (Basham, Citation2015: 77), and indexed to contemporary diplomatic and geopolitical interests and audiences (Jones, Citation2020).

In order to fully appreciate Our Islands, Our Home’s role and the way that it can be seen to move between commemorative and diplomatic/geopolitical modalities, we need to turn back to the publication and to look again at the profile pieces and other key components of the volume. As already mentioned, the profile pieces of the thirteen Islanders and their forebears carefully reveal elements of Falkland Islands’ history and heritage (and purposefully foreground the long, multigenerational, settlement of the Islands), while also signalling the diversity of the Falkland Islands’ economy (farming, fishing, tourism, mineral resources), institutional capacities (legal, medical and education), and commitment to environmental conservation (Blair, Citation2017). These are themes that are, in turn, amplified through the extensive photography that illustrates this volume and takes us on a visual tour of the Falklands from Stanley (the capital town/city) to farms in ‘Camp’ (the countryside), into the air with FIGAS (the Falkland Government Air Service) and out into the South Atlantic where we glimpse the fishing industry, oil and gas exploration as well as the diversity of the marine fauna in Falklands-controlled waters. The inference is clear: this is a Falklands that has a respect for the past (and the ability to curate its own story), but also a modern, future-looking ‘nation’ that is capable of ‘do[ing] everything a country needs to do’ (OIOH, p, 8). The cover image, which was later reproduced on a grand scale for display in the civilian arrivals hall of Mount Pleasant Airbase (the Islands’ international airport and UK military base), caught the eye of social anthropologist James Blair, when he visited the islands in 2013. He describes, thoughtfully, ‘a photo of six Falkland Islander children, leaping from a grassy field with arms stretched high. […] They looked almost as though they were emerging autochthonous from the territory their British ancestors settled’ (Blair, Citation2017: 582). This situated, almost primordial, connection between people and place closely reflects the FIG’s strategic diplomatic communications with international audiences. At heart, this comes down to the desire to ensure that the inhabitants of the Falkland Islands are recognized internationally as ‘Falkland Islanders’ – that is to say a distinct people, with their own culture, traditions and long-established history and heritage, as opposed to being ‘colonists’ or ‘settlers’, ‘implanted’ by ‘the British’.Footnote5 The reason that this recognition is so vital relates directly to the charter of the United Nations. As Mike Summers OBE stated in opening his address to the Special Committee on Decolonisation (also known as C-24) in June 2012, with a copy of Our Islands, Our Home in his possession, ‘Article 1 of the UN Charter sets out the importance of respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of all peoples.’ ‘With us today’, Summers continued, ‘we have part of a new generation of young Islanders who have a keen interest in our future development, who are fourth, fifth and sixth generation Islanders. I too am a sixth generation Falkland Islander.’ Turning to the Committee, Summers asked, rhetorically, ‘Why don’t we have the right to self-2012determination, but they [pointing to the Argentine delegation] do? Are we any less human; are we second class people with unequal rights?’ (Summers, Citation2012). If the members of the C-24 were left in any doubt about the Falkland Islands Government’s position, Our Islands, Our Homes provided a highly mobile answer to that question, speaking, as it does, of a community and a micronation, made up of individuals with long familial histories, who are earning a living, bringing up children, being entrepreneurs and caring for their natural environment and, in so doing, have sought to constitute themselves as a people with parochial interests and universal rights that translate across barriers and borders.

While the achievements of Falklands Islanders and their futures were undoubtedly foregrounded as living legacies of the past during the thirtieth anniversary year of the 1982 conflict, the experiences of war, invasion and occupation hung heavily over the formal diplomatic proceedings. In Our Islands, Our Home, direct references to war appear to have carefully pitched and attuned to the diplomatic occasion and international audiences (Sumartojo, Citation2021: 535). At the UN, the Falkland Islands’ delegation expressed regret for the ‘un-timely death of over a thousand young men in the Falklands in 1982’, condemned the ‘use of military force’, and invited the Committee members to celebrate ‘freedom, justice, and the right to live in peace and harmony’ – and in so doing attempted to universalize (and strategically foreground) the Falklands’ cause as one of internationally-recognized rights and freedoms, while eschewing (consciously backgrounding) overtly nationalist/parochial references to either ‘British forces’ or ‘Argentine troops’ and their respective losses. Strikingly, there is only one reference to Britain/British throughout either of the two speeches delivered by Falklands' delegates at the UN in 2012. Argentina, by comparison, is referenced in excess of sixty-five times. Given the highly choreographed nature of these diplomatic encounters at the UN, it would be fair to conclude that this was a purposeful attempt to draw the C-24’s attention away from thoughts of historic and ongoing British imperialism and to focus attention instead on the Falklands as a bilateral issue between Stanley and Buenos Airies. Perhaps this attempted shift, more than anything, explains the diplomatic and representational foregrounding of the Falkland Islands and Falkland Islanders in their own diplomatic narratives on the 30th anniversary of the 1982 conflict.

Las Malvinas Es Argentina

The map, Las Malvinas Es Argentina, is a visual smorgasbord of different historical reference points related to the Malvinas, many of which emphasize spatial and territorial connections between the islands and Argentina. These representations, characteristic of Rep’s artistic style deploying humour and fantasy in equal measure, juxtapose fictional and factual characters and events, many accompanied by explanatory captions on the reverse-side of the map. The inclusion of four imaginary bridges connects the Malvinas with other islands in the South West Atlantic (South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands), Antarctica, continental Argentina and the South American continent beyond. Argentina has frequently looked to present the Malvinas sovereignty dispute as a continental concern that goes beyond national foreign policy and these bridges leave little to the geopolitical imagination, visualizing Argentine ambitions to secure tricontinental territorial integrity (Benwell, Citation2014). The omnipresence of the Malvinas (and references to the 1982 Malvinas War) in Argentine political and public life is demonstrative of the ‘deep affective response to issues of territorial integrity’ (Billé, Citation2014: 164). The islands have come to embody the ‘phantom limbs’ of Argentina’s national territory, subject to continued British ‘occupation’ – according to Argentine politicians – and invested with emotional and ‘iconic significance’ as a result (ibid: 165). The outline of the map of the islands has almost become a national ‘logo’ that evokes the injustices of territorial dispossession at the hands of a colonial aggressor, and is often displayed at commemorative ceremonies marking the 1982 war, as well as on war memorials, murals and banners unfurled at football stadiums throughout the country (see Lorenz, Citation2020). The map of the Malvinas archipelago is instantly recognizable for Argentine audiences and was thus chosen as the canvas for Rep’s map.

The map itself foregrounds and emplaces historical events associated with cultural, musical, scientific, environmental, literary, geographical and geopolitical themes, many of which invoke events long before the 1982 war. There is a selective remembering of histories related to the Malvinas that largely bypass the war, in contrast to national narratives related to the islands that very often foreground commemoration of 1982 and those Argentines who fought and died. Indeed, in an interview with the media during the launch of the map at the UN, Rep explained that his artistic intervention was about, ‘Love and peace … we don’t have anything to do with that war, with the dictatorship. We are something else.’Footnote6 The production of the map itself was a collaborative process which saw Rep draw the map with input from historians, diplomats and the Secretary of Affairs pertaining to the Malvinas, Daniel Filmus. From 2003-2015, Argentina, under the presidencies of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, respectively, positioned the Malvinas sovereignty dispute as its foreign policy priority. This saw it undertake intensive diplomatic activity at regional/global summits and committees including the UN C-24, to which Argentina and the Falkland Islands send delegations in June every year.Footnote7 This ‘new state storytelling of the Falklands/Malvinas stimulated cultural and artistic production’ that was also embraced by the country’s diplomats and politicians, evidenced through the map we analyse here (Mira and Pedrosa, Citation2021: 19). So, in the case of the map, its presentation took place within a key diplomatic site, the UN Headquarters, alongside the meeting of the UN C-24 and, therefore, juxtaposed more traditional diplomatic audiences and interventions (i.e. the speeches of diplomats and state representatives) alongside creative and artistic diplomatic devices that reiterated Argentina’s sovereignty claim (Pinkerton and Benwell, Citation2014).

Although selective in what it chose to remember, it was clear that Rep and the authors of the map could not ignore the 1982 war altogether given its prominence in the recent history of Argentina and its subsequent influence on Anglo-Argentine diplomatic relations. Our specific interest here focuses on what and how the map chose to reference and remember the war through its depiction of certain sites, events and (human and non-human) actors. One of the most striking representations on the map appears in the waters to the south west of the islands and consists of 18 crosses configured in a circle that appear to be floating on the surface (see ). The site, described by Rep in an interview as, ‘a cemetery in the sea’, is surrounded by various marine fauna and overflown by albatross and petrels which drop flowers down on to the scene from the sky.Footnote8 The texts around the illustration make clear that this is where the Argentine Navy light cruiser, the ARA General Belgrano, was sunk on the 2nd May 1982 with the loss of 323 Argentine lives. The caption on the reverse side of the map details the attack stating, ‘The Belgrano was outside of the 200 mile radius military exclusion zone established by the UK … When sinking the Belgrano, the government of Margaret Thatcher also sunk all possibilities of a negotiated exit from the conflict.’ While we do not wish to rehearse the controversies surrounding the sinking of the Belgrano that have been well documented elsewhere (e.g. Freedman, Citation2005; Thompson, Citation2006), the choice of this event is instructive for understanding how Argentina seeks to remember 1982 on the international stage and how, in turn, this aligns with its contemporary diplomacy in relation to the sovereignty dispute.

Jones (Citation2020: 649) has acknowledged how diplomacy and diplomats frame ‘emotions as a socio-spatial calculation that can be performed for their specific effects on others’. The inclusion of the Belgrano’s sinking on the map, an incredibly sensitive and emotive episode in the war, could be understood as a calculated attempt to channel the emotional response of its audience. It enabled Argentina to foreground its victimization at the hands of British military aggression, an event that families of the deceased (although not the states of Argentina and the UK) have repeatedly denounced as a ‘war crime’ (Lorenz, Citation2014: 145). This neatly corresponds with Argentina’s framing of British militarization of the South West Atlantic as disproportionate and provocative in what it claims should be a region of peace.Footnote9 Moreover, evoking Thatcher’s intransigence and lack of willingness to negotiate mirrors Argentina’s continued frustrations regarding the UK’s refusal to participate in sovereignty negotiations (something the UK refuses to do without the expressed wishes of the Falkland Islanders). The appeals to marine fauna and birdlife as ‘custodians’ of commemoration over and around the site of the Belgrano, echo some of the ways Argentina has looked to reinforce its sovereignty claim in recent years. Maps of the migratory patterns of marine fauna (e.g. elephant seals) were displayed at the Malvinas Museum in Buenos Aires in 2015, emphasizing their mobilities between continental Argentina, the Malvinas and other South West Atlantic islands. The rather unsubtle geopolitical subtext here was that even the wildlife was backing up Argentina’s sovereignty claim based on ‘naturally’ occurring migrations that emphasized its territorial integrity (Blair, Citation2019). Similarly, in the case of the map, the geopolitical allegiances of albatross, petrels and a whole host of sea fauna are clearly represented as they solemnly pay respects to and protect Argentina’s marine war cemetery.

The only other reference to the 1982 war on the map foregrounds another ‘necro-place’ (Leshem, Citation2015: 35), this time the Argentine Military Cemetery on the islands which is more commonly known as Darwin Cemetery. Two soldiers, their identities unclear, and flanked by crosses of the cemetery, face off with their weapons drawn. The reverse-side caption for the image reads, ‘After the conflict, the UK offered to “repatriate” the bodies [of Argentine dead soldiers] sending them to continental Argentina, but the families of the fallen refused arguing that “there is nothing to repatriate, because they are in their homeland”, vindicating the Argentine claim over the islands.’ The framing of the war and the bodies that lay beneath the ground at this commemorative site reinforce, once again, Argentina’s claim that this is an integral part of national sovereign territory. It also does something more by showing how resistance to British presence in the region extends to civilians, in this case the families of Argentina’s war dead who are seen to be actively pushing back against ‘repatriation’ and by association the UK’s broader geopolitical ambitions in the region. The map’s representation of a sacred commemorative site in the islands evokes the asymmetrical and emotive nature of the dispute and brings to the fore Argentine suffering at the hands of British military aggression. At the same time, the text on the map chooses to avoid making reference to the abuses suffered by some Argentine conscripts at the hands of their superiors during the war (Lorenz, Citation2006, Citation2014), even if the image of the two soldiers is rather more ambiguous and could conceivably represent confrontation between an Argentine officer and conscript.

While on a national level Argentina has started to interrogate traumatic memories related to human rights abuses suffered by conscripts under the command of officers during the dictatorship and the Malvinas War more specifically (although these efforts are not without their tensions and controversies, see Benwell, Citation2021; Guber Citation2009), these are notably eschewed on the map. The map, a self-declared ‘message of peace’, contains very few references to the dictatorship either in text or image. This absence is, on the one hand, striking given the extensive national efforts centred on pursuing truth and justice in relation to human rights violations committed during the years of the dictatorship. This might have been an opportunity to give international exposure to Argentina’s critical reflection on its difficult recent history. On the other hand, it is less surprising given the challenges Argentina has faced as a nation coming to terms with how to remember the Malvinas War – a cause (i.e. the ‘reclaiming’ of the islands) that is considered ‘just’ by most Argentine citizens but one that was sullied by a war initiated by the notorious military dictatorship. This complex historical baggage, allied with the intended message to the UN that Argentina was now a democratic state pursuing its claim via diplomatic and peaceful means alone, arguably explains the (dearth of) references made to the Malvinas War on the map. Rep explained in interview that the title of the map Las Malvinas Es Argentina was a deliberate strategy to pivot away from residual associations connecting the Malvinas with the dictatorship:

‘When I pass by a sign or a poster at the side of the road that has the map and it says Las Malvinas Son Argentinas [the Malvinas are Argentine] for me it refers to this tragedy [the 1982 war], it refers to Galtieri, it refers … to this murderous dictatorship. So, what I did was change the word to Es Argentina [is Argentina]. Like, the Malvinas is Argentina, it’s like an Argentine province. That’s it! There isn’t any doubt.’

Conclusion

While interest in nationally performed narratives and practices of memory have burgeoned in the 40 years since the Falklands/Malvinas War, there has been a paucity of research exploring how these memories are negotiated and deployed on the international stage for diplomatic purposes. The ways that memories of war are summoned in these diplomatic settings, whether through materials or performances, can be revealing of how governments and their diplomats go about presenting strategic narratives to international audiences. Conscious decisions are made concerning how the past is to be spatiotemporally (re)presented and these decisions are crucial referents for understanding how diplomats attempt to influence international opinion, represent contemporary geopolitical relations and pursue strategic objectives. Memory is put to diplomatic work (sometimes via the labour of diplomats, artists, civilians and so on) in ways that do not always map neatly on to more familiar national mnemonic narratives, underlining a set of interesting tensions some of which we have outlined above. Rather than drawing on familiar national and parochial memory tropes, both Argentina and the Falkland Islands made carefully choreographed references to 1982 through the diplomatic materials and performances they presented at the UN. In short, decisions were made as to which events and whose accounts were foregrounded and backgrounded in ways that aligned with broader foreign policy objectives.

In the case of the Falkland Islands, the prominence of temporality told through the stories of Islanders as geopolitical agents of the war, and its subsequent commemoration, is especially prominent on the 30th anniversary and in subsequent years. In Our Islands, Our Home the 1982 war and its British military protagonists are certainly not forgotten (indeed the booklet is dedicated to them), yet the stories that are showcased (and recounted through speeches at the UN) selectively foreground the story of liberation and its legacies of freedom and justice through the bodies and inter-generational accounts of Falkland Islanders. Anniversary parades and national remembrance ceremonies in the Falkland Islands (and the UK) that tend to emphasize military registers through commemoration of the campaign fought by the British Armed Forces, are conspicuous by their absence in these diplomatic ‘scripts’. Indeed, references to Britain and the British military are toned down in the diplomatic materials and performances because this is a story of commemoration curated and authored by Falkland Islanders themselves. It is also, we argue, a consequence of the FIG’s sensitivity to Argentine framings of the Falkland Islands being labelled as a ‘colonial hangover’ of the British Empire. The foregrounding of bodies, objects and accounts from the Falkland Islands is, then, a strategic decision that pre-emptively aims to counter these kinds of charges stemming from Argentina. ‘Looking Forward at Forty’ (Hyslop, Citation2021) has been adopted by the FIG as the strapline for the 40th anniversary of the war (in 2022), and is a timely reminder that anniversaries are temporal, emotional and representational pivots that have the power to shift our attention into the past and towards the future and can perform important diplomatic labour. It is highly likely that the lives, ambitions and achievements of Islanders (as active geopolitical agents) will continue to occupy a central role in how the Falkland Islands Government chooses to commemorate their past (and perform their future) on the international stage.

The Las Malvinas Es Argentina map also chooses to remember historical events in ways that align with Argentina’s recent strategic approach to diplomacy. Important here are its appeals to the spatial and material links between continental Argentina and the Malvinas, emphasizing territorial integrity and interconnection. The map also draws on the temporal via historical events stretching back well beyond 1982 and, in so doing, illustrates the longevity of connections between the continent and the islands. However, these links are represented through the spatial mobilities of fictitious and non-fictitious (human and non-human) bodies and objects that tend to dominate the map, leaving little room for references to the 1982 war. This is not, we argue, accidental as the Kirchner government in Argentina looked to separate the ‘heroic deed’ of the Malvinas War from the actions of the dictatorship, as others have argued elsewhere (see Mira and Pedrosa, Citation2021). Indeed, the ‘necro-places’ shown on the map that reference the 1982 war provide a geographical space and representational opportunity for Argentina to emphasize its role as the victim of British military and colonial aggression. At the same time, they eschew references to the last military dictatorship, responsible for launching the invasion and the abuse of military conscripts sent to fight in the war. While popular and academic national interrogations of memory have started to shed light on these complex issues, they have the potential to be rather more problematic on the international stage where Argentina looks to present itself as a democratic state intent on pursuing territorial claims via peaceful and diplomatic channels alone. Further exploration of how memory of the Falklands/Malvinas War and other ongoing sovereignty and territorial disputes are negotiated on the international stage through shifting diplomatic practices, spatiotemporal registers and materials would help shed additional light on these kinds of pivots and tensions. These provide telling insights into the kinds of geopolitical identities, imaginaries and narratives that governments wish (and work hard) to present to international audiences, as well as giving an insight into those they wish to downplay.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to Rep for kindly agreeing to be interviewed for this paper. His insight deepened our understanding of the Las Malvinas Es Argentina map. Dr Benwell wishes to acknowledge the generous funding of the Leverhulme Trust (Award number: ECF-2012-329). We also thank Sukey Cameron, the Falkland Islands Government Representative in London (1990-2019), her successor, Richard Hyslop (2019-present) and other colleagues at the Falkland Islands Government Office in London, including Michael Betts, for their support and insights over many years. Dr Pinkerton also acknowledges the generous support of the Shackleton Scholarship Fund, who supported his research on and around the Falkland Island Referendum (2013), which, despite the nine-year distance, continues to inform and reverberate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew C. Benwell

Matthew C. Benwell is a political geographer with a particular interest in people's everyday engagements with geopolitical events past and present. His regional specialism focuses on the Southern Cone encompassing Argentina, Chile, British Overseas Territories in the South Atlantic (including the Falkland Islands) and Antarctica.

Alasdair Pinkerton

Alasdair Pinkerton is a political geographer with specialist interests in international territorial and boundary disputes, geopolitics and diplomacy. His work has examined the history and heritage of “no man's lands” in the contexts of Europe, North Africa and South America, as well as the contemporary geopolitics of British Overseas Territories, ranging from the Sovereign Bases Areas (SBAs) in Cyprus to the Falkland Islands.

Notes

1 Argentina’s diplomatic statements and foreign policy measures have been seen as anything but peaceful in the Falkland Islands. These have looked, for instance, to challenge and impede what Argentina considers ‘illegal’ oil exploration in the waters around the Falklands (see Benwell, Citation2019).

2 While the UK retains responsibility for the defence and foreign affairs of its Overseas Territories including the Falkland Islands, in recent years the FIG has taken the diplomatic initiative and proactively sought to represent itself on the international stage, hence our focus in this paper. This has been animated by the FIG’s production of ‘glossy’ diplomatic materials like the booklet we analyse, its presence online and diplomatic visits to Latin American countries. The FIG’s efforts to self-represent themselves should also be historically contextualised with reference to the disquiet caused by British politicians and diplomats entering into sovereignty negotiations with their Argentine counterparts, without representatives of the Islands, prior to 1982 (see Dodds, Citation2002; Mercau, Citation2019).

3 2015 marked the 50th anniversary of the UN General Assembly Resolution 2065 that was adopted in December 1965. The resolution, regularly hailed as a significant diplomatic victory in Argentina, recognises the existence of a sovereignty dispute between Argentina and the UK over the Falklands/Malvinas Islands, and invites the parties to find a peaceful solution that takes into consideration the ‘interests’ (and, importantly, for its implications regarding self-determination, not the ‘wishes’) of the islanders.

4 The economic and demographic decline of the Falkland Islands were a very real concern in the decade prior to 1982 and were the impetus behind the landmark “Shackleton Report” of 1976 – the proposals from which went largely unimplemented before 1982, but became something of a blueprint for the Islands’ post-war reinvigoration as part of Lord Shackleton’s updated report, published in December 1982.

5 The refusal to acknowledge the existence of Falkland Islanders as a distinct people has been a persistent feature of Argentine political and diplomatic discourse. Argentine sources do not tend, therefore, to distinguish between ‘the British’ and ‘Falkland Islanders’, preferring instead to refer to the inhabitants of the islands as ‘Kelpers’ – a term of intended derision referring to an outmoded belief that Islanders rely on the native kelp for sustenance (Niebieskikwiat, Citation2014). It is worth noting that many Falkland Islanders - especially older islanders - routinely self-identify as ‘Kelpers’.

6 A quote from a media interview with Rep conducted after the event at the UN. The clip can be viewed via the official Argentine government YouTube channel (Casa Rosada, República Argentina, Citation2015).

7 The President of Argentina at the time, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, attended the C-24 in 2012 to deliver an impassioned speech; a highly unusual move, given the C-24 is rarely attended by the heads of G20 states.

8 Rep was interviewed via Skype by the first author on the 6 December 2018.

9 Argentina frequently protests British military presence at RAF Mount Pleasant, labelled on Rep’s map with tongue firmly in cheek as the ‘Unpleasant Military Base’.

References

- Assmann, A. 2010. From Collective Violence to a Common Future: Four Models for Dealing with a Traumatic Past. In: H. Gonçalves da Silva, A.A.P. Martins, F.V. Guarda & M. Sardica, eds. Conflict, Memory Transfers and the Reshaping of Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 8–23.

- Bachleitner, K. 2019. Diplomacy with Memory: How the Past is Employed for Future Foreign Policy. Foreign Policy Analysis, 15(4):492–508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/ory013

- Basham, V.M. 2015. Telling Geopolitical Tales: Temporality, Rationality, and the ‘Childish’ in the Ongoing war for the Falklands-Malvinas Islands. Critical Studies on Security, 3(1):77–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2015.1014698

- Bellot, A. 2018. The Faces of the Enemy: The Representation of the ‘Other’ in the Media Discourse of the Falklands War Anniversary. Journal of War & Culture Studies, 11(1):79–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17526272.2017.1298703

- Benwell, M.C. 2014. Connecting Southern Frontiers: Argentina, the South West Atlantic and ‘Argentine Antarctic Territory’. In: R.C. Powell & K. Dodds, eds. Polar Geopolitics? Knowledges, Resources and Legal Regimes. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 201–218.

- Benwell, M.C. 2016a. Reframing Memory in the School Classroom: Remembering the Malvinas War. Journal of Latin American Studies, 48(2):273–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X15001248

- Benwell, M.C. 2016b. Young Falkland Islanders and Diplomacy in the South Atlantic. In: M.C. Benwell & P. Hopkins, eds. Children, Young People and Critical Geopolitics. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 107–121.

- Benwell, M.C. 2019. Connecting Ontological (in)Securities and Generation Through the Everyday and Emotional Geopolitics of Falkland Islanders. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(4):485–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1290819

- Benwell, M.C. 2021. Going Back to School: Engaging Veterans’ Memories of the Malvinas war in Secondary Schools in Santa Fe, Argentina. Political Geography, 86): doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102351

- Benwell, M.C., Gasel, A.F. & Núñez, A. 2020. Bringing the Falklands/Malvinas Home: Young People’s Everyday Engagements with Geopolitics in Domestic Space. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 39(4):424–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13018

- Billé, F. 2014. Territorial Phantom Pains (and Other Cartographic Anxieties). Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(1):163–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d20112

- Blair, J.J.A. 2017. Settler Indigeneity and the Eradication of the non-Native: Self-Determination and Biosecurity in the Falkland Islands (Malvinas). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 23(3):580–602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12653

- Blair, J.J.A. 2019. South Atlantic Universals: Science, Sovereignty and Self-Determination in the Falkland Islands (Malvinas). Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society, 2(1):220–236.

- Blejmar, J. 2017. Autofictions of Postwar: Fostering Empathy in Lola Arias’ Minefield/Campo Minado. Latin American Theatre Review, 50(2):103–124. https://journals.ku.edu/latr/article/view/7323.

- Bound, G. 2006. Falkland Islanders at War. New Edition: Pen and Sword.

- Boyarin, J. 1994. Space, Time and the Politics of Memory. In: J Boyarin, ed. Remapping Memory: The Politics of Timespace. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 1–39.

- Casa Rosada, República Argentina (2015) Gustavo Santaolalla y Miguel Rep dialogaron con la prensa en la ONU [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UaN8iQQSO7E [Accessed 17 September 2021].

- Clarke, D. & Duber, P. 2020. Polish Cultural Diplomacy and Historical Memory: The Case of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 33:49–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9294-x

- Closs Stephens, A. 2016. The Affective Atmospheres of Nationalism. Cultural Geographies, 23(2):181–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474015569994

- David, L. 2019. Policing Memory in Bosnia: Ontological Security and International Administration of Memorialization Policies. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, 32(1):211–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9305-y

- Depledge, D. 2015. Geopolitical Material: Assemblages of Geopower and the Constitution of the Geopolitical Stage. Political Geography, 45:91–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.05.001

- Dittmer, J. 2017. Diplomatic Material: Affect, Assemblage, and Foreign Policy. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Dodds, K. 2002. Pink Ice: Britain and the South Atlantic Empire. London: I B Tauris.

- Dodds, K. & Manovil, L. 2001. Back to the Future? Anglo-Argentine-Falkland Relations and the Implementation of the 14th July Agreement. Journal of Latin American Relations, 33:777–806. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3653764.

- Drozdzewski, D., De Nardi, S. & Waterton, E. 2016. Geographies of Memory, Place and Identity: Intersections in Remembering war and Conflict. Geography Compass, 10(11):447–456. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12296

- Eckersley, S. 2015. Walking the Tightrope Between Memory and Diplomacy? Addressing the Post-World War II Expulsions of Germans in German Museums. In: C. Whitehead, K. Lloyd, S. Eckersley & R. Mason, eds. Museums, Migration and Identity in Europe. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 101–122.

- Edkins, J. 2003. Trauma and the Memory of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Freedman, L. 2005. The Official History of the Falklands Campaign. Volume II: War and Diplomacy. London: Routledge.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity. New York, NY: Polity Press.

- González, M.A. 2013. The Genesis of the Falklands (Malvinas) Conflict. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guber, R. 2001. ¿Por qué Malvinas? De la Causa Nacional a la Guerra Absurda. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Guber, R. 2009. De Chicos a Veteranos: Nación y Memorias de La Guerra de Malvinas. Buenos Aires: Colección La Otra Ventana.

- Hyslop, R. (2021) The liberation of the Falklands. The Herald, 14 Sept [online]. Available from: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/19578065.letters-snp-must-stop-running-scared-take-control-energy/ [Accessed 17 September 2021].

- Jones, A. 2020. Towards an Emotional Geography of Diplomacy: Insights from the United Nations Security Council. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(3):649–663. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12371

- Jones, A. & Clark, J. 2019. Performance, Emotions, and Diplomacy in the United Nations Assemblage in New York. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109(4):1262–1278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1509689

- Kuusisto-Arponen, A.-K. 2014. Silence, Childhood Displacement, and Spatial Belonging. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 13(3):434–441. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1017/871.

- Laing, R.D. 1960. The Divided Self. London: Tavistock Publications.

- Leshem, N. 2015. Over our Dead Bodies’: Placing Necropolitical Activism. Political Geography, 45:34–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.09.003

- Lin, W. 2021. Summit Atmospheres: Aviation Diplomacy and Virtual Infrastructures of Politics. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 46(2):406–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12428

- Lorenz, F. 2006. Las Guerras por Malvinas. Buenos Aires: Edhasa.

- Lorenz, F. 2014. Todo lo que Necesitás Saber Sobre Malvinas. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

- Lorenz, F. 2020. Malvinas/Falklands War: Changes in the Idea of Nationhood, the Local and National, in a Post-Dictatorship Context—Argentina, 1982-2007. In: J. Grigera & L. Zorzoli, eds. The Argentinian Dictatorship and its Legacy: Rethinking the Proceso. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 197–209.

- Maguire, G. 2019. Screening the Past: Reflexivity, Repetition and the Spectator in Lola Arias’ Minefield/Campo Minado (2016). Bulletin of Latin American Research, 38(4): 471-486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.12849

- Maltby, S. 2016. Remembering the Falklands War: Media, Memory and Identity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McAllister, C. 2020. Borders Inscribed on the Body: Geopolitics and the Everyday in the Work of Martín Kohan. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 39(4):453–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13089

- McConnell, F. 2019. Rethinking the Geographies of Diplomacy. Diplomatica, 1(1):46–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/25891774-00101008

- McConnell, F. & Dittmer, J. 2018. Liminality and the Diplomacy of the British Overseas Territories: An Assemblage Approach. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 36(1):139–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817733479

- Meehan, K., Shaw, I.G.R. & Marston, S.A. 2013. Political Geographies of the Object. Political Geographies, 33(1):1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.11.002

- Mercau, E. 2019. The Falklands War: An Imperial History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Merriman, P. 2020. National Movements. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(4):585–586. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420912445c

- Merriman, P. & Jones, R. 2017. Nations, Materialities and Affects. Progress in Human Geography, 41(5):600–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516649453

- Mira, G. & Pedrosa, F. eds. 2021. Revisiting the Falklands-Malvinas Question: Transnational and Interdisciplinary Perspectives. London: University of London Press.

- Mitchell, K. 2003. Monuments, Memorials, and the Politics of Memory. Urban Geography, 24(5):442–459. doi:https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.24.5.442

- Müller, M. 2017. More-than-representational Political Geographies. In: J. Agnew, V. Mamadouh, A.J. Secor & J. Sharp, eds. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Political Geography. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 409–423.

- Muzaini, H. 2015. On the Matter of Forgetting and ‘Memory Returns’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40(1):102–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12060

- Niebieskikwiat, N. (2014) Kelpers: Ni ingleses no argentinos. Cómo es la nación que crece frente a nuestras costas. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana.

- Our Islands, Our Home (2012) Produced on behalf of the Falkland Islands Government by Jenny Cockwell [online]. Available from: http://falklands.gov.fk/assets/Our-Islands-Our-Home.pdf [Accessed 17 September 2021].

- Parr, H. 2018. Our Boys: The Story of a Paratrooper. London: Penguin Books.

- Pinkerton, A. & Benwell, M.C. 2014. Rethinking Popular Geopolitics in the Falklands/Malvinas Sovereignty Dispute: Creative Diplomacy and Citizen Statecraft. Political Geography, 38:12–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.10.003

- Raj, D.S. 2000. Ignorance, Forgetting, and Family Nostalgia: Partition, the Nation State and Refugees in Delhi. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Anthropology, 44(2):30–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23166533.

- Rech, M.F. 2020. Ephemera(l) Geopolitics: The Material Cultures of British Military Recruitment. Geopolitics, 25(5):1075–1098. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2019.1570920

- Royle, S.A. 2013. Escaping from the Past? The Falkland Islands in the Twenty-First Century. In: H. Johnson and H. Sparling eds. Refereed Papers from ISIC 8 – Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Canada, pp. 35-41.

- Sharp, J. 2020. Materials, Forensics and Feminist Geopolitics. Progress in Human Geography. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520905653

- Sumartojo, S. 2020. National Potential: Affect, Possibility and the Nation-in-Progress. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(4):582–584. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420912445b

- Sumartojo, S. 2021. New Geographies of Commemoration. Progress in Human Geography, 45(3):531–547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520936758

- Summers, M. 2012. United Nations General Assembly, Special Committee of 24 on Decolonisation, Statement by The Honourable Mike Summers OBE, Member of the Legislative Assembly, Falkland Islands Government [online]. Available from: http://www.falklands.gov.fk/assembly/jdownloads/UN%20C24/C24%20Speech%202012-%20Hon%20Mike%20Summers%20OBE.pdf [Accessed 20 May 2022].

- Thompson, J. 2006. Sir Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign. Journal of Strategic Studies, 29(3):535–551. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390600765918

- Thrift, N. 2000. It’s the Little Things. In: K. Dodds & D. Atkinson, eds. Geopolitical Traditions: Critical Histories of a Century of Geopolitical Thought. London: Routledge, pp. 380–387.

- Till, K. 2003. Places of Memory. In: J. Agnew, K. Mitchell & G. Toal, eds. A Companion to Political Geography. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 289–301.

- Trouillot, M.R. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Wilson, H.F. & Anderson, B. 2020. Detachment, Disaffection, and Other Ambivalent Affects. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(4):591–593. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420912445f